Sensitivity to initial conditions

Sensitivity to initial conditions means that each point in a chaotic system is arbitrarily closely approximated by other points that have significantly different future paths or trajectories. Thus, an arbitrarily small change or perturbation of the current trajectory may lead to significantly different future behavior.[2]

Sensitivity to initial conditions is popularly known as the "butterfly effect", so-called because of the title of a paper given by Edward Lorenz in 1972 to the American Association for the Advancement of Science in Washington, D.C., entitled Predictability: Does the Flap of a Butterfly's Wings in Brazil set off a Tornado in Texas?.[28] The flapping wing represents a small change in the initial condition of the system, which causes a chain of events that prevents the predictability of large-scale phenomena. Had the butterfly not flapped its wings, the trajectory of the overall system could have been vastly different.

As suggested in Lorenz's book entitled The Essence of Chaos, published in 1993,[5] "sensitive dependence can serve as an acceptable definition of chaos". In the same book, Lorenz defined the butterfly effect as: "The phenomenon that a small alteration in the state of a dynamical system will cause subsequent states to differ greatly from the states that would have followed without the alteration." The above definition is consistent with the sensitive dependence of solutions on initial conditions (SDIC). An idealized skiing model was developed to illustrate the sensitivity of time-varying paths to initial positions.[5] A predictability horizon can be determined before the onset of SDIC (i.e., prior to significant separations of initial nearby trajectories).[29]

A consequence of sensitivity to initial conditions is that if we start with a limited amount of information about the system (as is usually the case in practice), then beyond a certain time, the system would no longer be predictable. This is most prevalent in the case of weather, which is generally predictable only about a week ahead.[30] This does not mean that one cannot assert anything about events far in the future—only that some restrictions on the system are present. For example, we know that the temperature of the surface of the earth will not naturally reach 100 °C (212 °F) or fall below −130 °C (−202 °F) on earth (during the current geologic era), but we cannot predict exactly which day will have the hottest temperature of the year.

In more mathematical terms, the Lyapunov exponent measures the sensitivity to initial conditions, in the form of rate of exponential divergence from the perturbed initial conditions.[31] More specifically, given two starting trajectories in the phase space that are infinitesimally close, with initial separation , the two trajectories end up diverging at a rate given by

where is the time and is the Lyapunov exponent. The rate of separation depends on the orientation of the initial separation vector, so a whole spectrum of Lyapunov exponents can exist. The number of Lyapunov exponents is equal to the number of dimensions of the phase space, though it is common to just refer to the largest one. For example, the maximal Lyapunov exponent (MLE) is most often used, because it determines the overall predictability of the system. A positive MLE is usually taken as an indication that the system is chaotic.[8]

In addition to the above property, other properties related to sensitivity of initial conditions also exist. These include, for example, measure-theoretical mixing (as discussed in ergodic theory) and properties of a K-system.[11]

Non-periodicity

A chaotic system may have sequences of values for the evolving variable that exactly repeat themselves, giving periodic behavior starting from any point in that sequence. However, such periodic sequences are repelling rather than attracting, meaning that if the evolving variable is outside the sequence, however close, it will not enter the sequence and in fact, will diverge from it. Thus for almost all initial conditions, the variable evolves chaotically with non-periodic behavior.

Topological mixing

Topological mixing (or the weaker condition of topological transitivity) means that the system evolves over time so that any given region or open set of its phase space eventually overlaps with any other given region. This mathematical concept of "mixing" corresponds to the standard intuition, and the mixing of colored dyes or fluids is an example of a chaotic system.

Topological mixing is often omitted from popular accounts of chaos, which equate chaos with only sensitivity to initial conditions. However, sensitive dependence on initial conditions alone does not give chaos. For example, consider the simple dynamical system produced by repeatedly doubling an initial value. This system has sensitive dependence on initial conditions everywhere, since any pair of nearby points eventually becomes widely separated. However, this example has no topological mixing, and therefore has no chaos. Indeed, it has extremely simple behavior: all points except 0 tend to positive or negative infinity.

Topological transitivity

A map is said to be topologically transitive if for any pair of non-empty open sets , there exists such that . Topological transitivity is a weaker version of topological mixing. Intuitively, if a map is topologically transitive then given a point x and a region V, there exists a point y near x whose orbit passes through V. This implies that it is impossible to decompose the system into two open sets.[32]

An important related theorem is the Birkhoff Transitivity Theorem. It is easy to see that the existence of a dense orbit implies topological transitivity. The Birkhoff Transitivity Theorem states that if X is a second countable, complete metric space, then topological transitivity implies the existence of a dense set of points in X that have dense orbits.[33]

Density of periodic orbits

For a chaotic system to have dense periodic orbits means that every point in the space is approached arbitrarily closely by periodic orbits.[32] The one-dimensional logistic map defined by x → 4 x (1 – x) is one of the simplest systems with density of periodic orbits. For example, → → (or approximately 0.3454915 → 0.9045085 → 0.3454915) is an (unstable) orbit of period 2, and similar orbits exist for periods 4, 8, 16, etc. (indeed, for all the periods specified by Sharkovskii's theorem).[34]

Sharkovskii's theorem is the basis of the Li and Yorke[35] (1975) proof that any continuous one-dimensional system that exhibits a regular cycle of period three will also display regular cycles of every other length, as well as completely chaotic orbits.

Strange attractors

Some dynamical systems, like the one-dimensional logistic map defined by x → 4 x (1 – x), are chaotic everywhere, but in many cases chaotic behavior is found only in a subset of phase space. The cases of most interest arise when the chaotic behavior takes place on an attractor, since then a large set of initial conditions leads to orbits that converge to this chaotic region.[36]

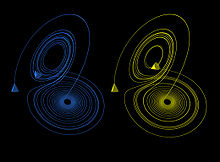

An easy way to visualize a chaotic attractor is to start with a point in the basin of attraction of the attractor, and then simply plot its subsequent orbit. Because of the topological transitivity condition, this is likely to produce a picture of the entire final attractor, and indeed both orbits shown in the figure on the right give a picture of the general shape of the Lorenz attractor. This attractor results from a simple three-dimensional model of the Lorenz weather system. The Lorenz attractor is perhaps one of the best-known chaotic system diagrams, probably because it is not only one of the first, but it is also one of the most complex, and as such gives rise to a very interesting pattern that, with a little imagination, looks like the wings of a butterfly.

Unlike fixed-point attractors and limit cycles, the attractors that arise from chaotic systems, known as strange attractors, have great detail and complexity. Strange attractors occur in both continuous dynamical systems (such as the Lorenz system) and in some discrete systems (such as the Hénon map). Other discrete dynamical systems have a repelling structure called a Julia set, which forms at the boundary between basins of attraction of fixed points. Julia sets can be thought of as strange repellers. Both strange attractors and Julia sets typically have a fractal structure, and the fractal dimension can be calculated for them.

Coexisting attractors

In contrast to single type chaotic solutions, recent studies using Lorenz models [40][41] have emphasized the importance of considering various types of solutions. For example, coexisting chaotic and non-chaotic may appear within the same model (e.g., the double pendulum system) using the same modeling configurations but different initial conditions. The findings of attractor coexistence, obtained from classical and generalized Lorenz models,[37][38][39] suggested a revised view that "the entirety of weather possesses a dual nature of chaos and order with distinct predictability", in contrast to the conventional view of "weather is chaotic".

Minimum complexity of a chaotic system

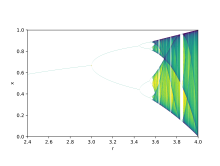

Discrete chaotic systems, such as the logistic map, can exhibit strange attractors whatever their dimensionality. Universality of one-dimensional maps with parabolic maxima and Feigenbaum constants ,[42][43] is well visible with map proposed as a toy model for discrete laser dynamics: , where stands for electric field amplitude, [44] is laser gain as bifurcation parameter. The gradual increase of at interval changes dynamics from regular to chaotic one[45] with qualitatively the same bifurcation diagram as those for logistic map.

In contrast, for continuous dynamical systems, the Poincaré–Bendixson theorem shows that a strange attractor can only arise in three or more dimensions. Finite-dimensional linear systems are never chaotic; for a dynamical system to display chaotic behavior, it must be either nonlinear or infinite-dimensional.

The Poincaré–Bendixson theorem states that a two-dimensional differential equation has very regular behavior. The Lorenz attractor discussed below is generated by a system of three differential equations such as:

where , , and make up the system state, is time, and , , are the system parameters. Five of the terms on the right hand side are linear, while two are quadratic; a total of seven terms. Another well-known chaotic attractor is generated by the Rössler equations, which have only one nonlinear term out of seven. Sprott[46] found a three-dimensional system with just five terms, that had only one nonlinear term, which exhibits chaos for certain parameter values. Zhang and Heidel[47][48] showed that, at least for dissipative and conservative quadratic systems, three-dimensional quadratic systems with only three or four terms on the right-hand side cannot exhibit chaotic behavior. The reason is, simply put, that solutions to such systems are asymptotic to a two-dimensional surface and therefore solutions are well behaved.

While the Poincaré–Bendixson theorem shows that a continuous dynamical system on the Euclidean plane cannot be chaotic, two-dimensional continuous systems with non-Euclidean geometry can exhibit chaotic behavior.[49][self-published source?] Perhaps surprisingly, chaos may occur also in linear systems, provided they are infinite dimensional.[50] A theory of linear chaos is being developed in a branch of mathematical analysis known as functional analysis.

The above elegant set of three ordinary differential equations has been referred to as the three-dimensional Lorenz model.[51] Since 1963, higher-dimensional Lorenz models have been developed in numerous studies[52][53][37][38] for examining the impact of an increased degree of nonlinearity, as well as its collective effect with heating and dissipations, on solution stability.

Infinite dimensional maps

The straightforward generalization of coupled discrete maps[54] is based upon convolution integral which mediates interaction between spatially distributed maps: ,

where kernel is propagator derived as Green function of a relevant physical system,[55] might be logistic map alike or complex map. For examples of complex maps the Julia set or Ikeda map may serve. When wave propagation problems at distance with wavelength are considered the kernel may have a form of Green function for Schrödinger equation:.[56][57]

.

Jerk systems

In physics, jerk is the third derivative of position, with respect to time. As such, differential equations of the form

are sometimes called jerk equations. It has been shown that a jerk equation, which is equivalent to a system of three first order, ordinary, non-linear differential equations, is in a certain sense the minimal setting for solutions showing chaotic behavior. This motivates mathematical interest in jerk systems. Systems involving a fourth or higher derivative are called accordingly hyperjerk systems.[58]

A jerk system's behavior is described by a jerk equation, and for certain jerk equations, simple electronic circuits can model solutions. These circuits are known as jerk circuits.

One of the most interesting properties of jerk circuits is the possibility of chaotic behavior. In fact, certain well-known chaotic systems, such as the Lorenz attractor and the Rössler map, are conventionally described as a system of three first-order differential equations that can combine into a single (although rather complicated) jerk equation. Another example of a jerk equation with nonlinearity in the magnitude of is:

Here, A is an adjustable parameter. This equation has a chaotic solution for A=3/5 and can be implemented with the following jerk circuit; the required nonlinearity is brought about by the two diodes:

In the above circuit, all resistors are of equal value, except , and all capacitors are of equal size. The dominant frequency is . The output of op amp 0 will correspond to the x variable, the output of 1 corresponds to the first derivative of x and the output of 2 corresponds to the second derivative.

Similar circuits only require one diode[59] or no diodes at all.[60]

See also the well-known Chua's circuit, one basis for chaotic true random number generators.[61] The ease of construction of the circuit has made it a ubiquitous real-world example of a chaotic system.

Spontaneous order

Under the right conditions, chaos spontaneously evolves into a lockstep pattern. In the Kuramoto model, four conditions suffice to produce synchronization in a chaotic system. Examples include the coupled oscillation of Christiaan Huygens' pendulums, fireflies, neurons, the London Millennium Bridge resonance, and large arrays of Josephson junctions.[62]

History

An early proponent of chaos theory was Henri Poincaré. In the 1880s, while studying the three-body problem, he found that there can be orbits that are nonperiodic, and yet not forever increasing nor approaching a fixed point.[63][64][65] In 1898, Jacques Hadamard published an influential study of the chaotic motion of a free particle gliding frictionlessly on a surface of constant negative curvature, called "Hadamard's billiards".[66] Hadamard was able to show that all trajectories are unstable, in that all particle trajectories diverge exponentially from one another, with a positive Lyapunov exponent.

Chaos theory began in the field of ergodic theory. Later studies, also on the topic of nonlinear differential equations, were carried out by George David Birkhoff,[67] Andrey Nikolaevich Kolmogorov,[68][69][70] Mary Lucy Cartwright and John Edensor Littlewood,[71] and Stephen Smale.[72] Except for Smale, these studies were all directly inspired by physics: the three-body problem in the case of Birkhoff, turbulence and astronomical problems in the case of Kolmogorov, and radio engineering in the case of Cartwright and Littlewood.[citation needed] Although chaotic planetary motion had not been observed, experimentalists had encountered turbulence in fluid motion and nonperiodic oscillation in radio circuits without the benefit of a theory to explain what they were seeing.

Despite initial insights in the first half of the twentieth century, chaos theory became formalized as such only after mid-century, when it first became evident to some scientists that linear theory, the prevailing system theory at that time, simply could not explain the observed behavior of certain experiments like that of the logistic map. What had been attributed to measure imprecision and simple "noise" was considered by chaos theorists as a full component of the studied systems. In 1959 Boris Valerianovich Chirikov proposed a criterion for the emergence of classical chaos in Hamiltonian systems (Chirikov criterion). He applied this criterion to explain some experimental results on plasma confinement in open mirror traps.[73][74] This is regarded as the very first physical theory of chaos, which succeeded in explaining a concrete experiment. And Boris Chirikov himself is considered as a pioneer in classical and quantum chaos.[75][76][77]

The main catalyst for the development of chaos theory was the electronic computer. Much of the mathematics of chaos theory involves the repeated iteration of simple mathematical formulas, which would be impractical to do by hand. Electronic computers made these repeated calculations practical, while figures and images made it possible to visualize these systems. As a graduate student in Chihiro Hayashi's laboratory at Kyoto University, Yoshisuke Ueda was experimenting with analog computers and noticed, on November 27, 1961, what he called "randomly transitional phenomena". Yet his advisor did not agree with his conclusions at the time, and did not allow him to report his findings until 1970.[78][79]

Edward Lorenz was an early pioneer of the theory. His interest in chaos came about accidentally through his work on weather prediction in 1961.[13] Lorenz and his collaborator Ellen Fetter[80] were using a simple digital computer, a Royal McBee LGP-30, to run weather simulations. They wanted to see a sequence of data again, and to save time they started the simulation in the middle of its course. They did this by entering a printout of the data that corresponded to conditions in the middle of the original simulation. To their surprise, the weather the machine began to predict was completely different from the previous calculation. They tracked this down to the computer printout. The computer worked with 6-digit precision, but the printout rounded variables off to a 3-digit number, so a value like 0.506127 printed as 0.506. This difference is tiny, and the consensus at the time would have been that it should have no practical effect. However, Lorenz discovered that small changes in initial conditions produced large changes in long-term outcome.[81] Lorenz's discovery, which gave its name to Lorenz attractors, showed that even detailed atmospheric modeling cannot, in general, make precise long-term weather predictions.

In 1963, Benoit Mandelbrot, studying information theory, discovered that noise in many phenomena (including stock prices and telephone circuits) was patterned like a Cantor set, a set of points with infinite roughness and detail [82] Mandelbrot described both the "Noah effect" (in which sudden discontinuous changes can occur) and the "Joseph effect" (in which persistence of a value can occur for a while, yet suddenly change afterwards).[83][84] In 1967, he published "How long is the coast of Britain? Statistical self-similarity and fractional dimension", showing that a coastline's length varies with the scale of the measuring instrument, resembles itself at all scales, and is infinite in length for an infinitesimally small measuring device.[85] Arguing that a ball of twine appears as a point when viewed from far away (0-dimensional), a ball when viewed from fairly near (3-dimensional), or a curved strand (1-dimensional), he argued that the dimensions of an object are relative to the observer and may be fractional. An object whose irregularity is constant over different scales ("self-similarity") is a fractal (examples include the Menger sponge, the Sierpiński gasket, and the Koch curve or snowflake, which is infinitely long yet encloses a finite space and has a fractal dimension of circa 1.2619). In 1982, Mandelbrot published The Fractal Geometry of Nature, which became a classic of chaos theory.[86]

In December 1977, the New York Academy of Sciences organized the first symposium on chaos, attended by David Ruelle, Robert May, James A. Yorke (coiner of the term "chaos" as used in mathematics), Robert Shaw, and the meteorologist Edward Lorenz. The following year Pierre Coullet and Charles Tresser published "Itérations d'endomorphismes et groupe de renormalisation", and Mitchell Feigenbaum's article "Quantitative Universality for a Class of Nonlinear Transformations" finally appeared in a journal, after 3 years of referee rejections.[43][87] Thus Feigenbaum (1975) and Coullet & Tresser (1978) discovered the universality in chaos, permitting the application of chaos theory to many different phenomena.

In 1979, Albert J. Libchaber, during a symposium organized in Aspen by Pierre Hohenberg, presented his experimental observation of the bifurcation cascade that leads to chaos and turbulence in Rayleigh–Bénard convection systems. He was awarded the Wolf Prize in Physics in 1986 along with Mitchell J. Feigenbaum for their inspiring achievements.[88]

In 1986, the New York Academy of Sciences co-organized with the National Institute of Mental Health and the Office of Naval Research the first important conference on chaos in biology and medicine. There, Bernardo Huberman presented a mathematical model of the eye tracking dysfunction among people with schizophrenia.[89] This led to a renewal of physiology in the 1980s through the application of chaos theory, for example, in the study of pathological cardiac cycles.

In 1987, Per Bak, Chao Tang and Kurt Wiesenfeld published a paper in Physical Review Letters[90] describing for the first time self-organized criticality (SOC), considered one of the mechanisms by which complexity arises in nature.

Alongside largely lab-based approaches such as the Bak–Tang–Wiesenfeld sandpile, many other investigations have focused on large-scale natural or social systems that are known (or suspected) to display scale-invariant behavior. Although these approaches were not always welcomed (at least initially) by specialists in the subjects examined, SOC has nevertheless become established as a strong candidate for explaining a number of natural phenomena, including earthquakes, (which, long before SOC was discovered, were known as a source of scale-invariant behavior such as the Gutenberg–Richter law describing the statistical distribution of earthquake sizes, and the Omori law[91] describing the frequency of aftershocks), solar flares, fluctuations in economic systems such as financial markets (references to SOC are common in econophysics), landscape formation, forest fires, landslides, epidemics, and biological evolution (where SOC has been invoked, for example, as the dynamical mechanism behind the theory of "punctuated equilibria" put forward by Niles Eldredge and Stephen Jay Gould). Given the implications of a scale-free distribution of event sizes, some researchers have suggested that another phenomenon that should be considered an example of SOC is the occurrence of wars. These investigations of SOC have included both attempts at modelling (either developing new models or adapting existing ones to the specifics of a given natural system), and extensive data analysis to determine the existence and/or characteristics of natural scaling laws.

In the same year, James Gleick published Chaos: Making a New Science, which became a best-seller and introduced the general principles of chaos theory as well as its history to the broad public.[92] Initially the domain of a few, isolated individuals, chaos theory progressively emerged as a transdisciplinary and institutional discipline, mainly under the name of nonlinear systems analysis. Alluding to Thomas Kuhn's concept of a paradigm shift exposed in The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962), many "chaologists" (as some described themselves) claimed that this new theory was an example of such a shift, a thesis upheld by Gleick.

The availability of cheaper, more powerful computers broadens the applicability of chaos theory. Currently, chaos theory remains an active area of research,[93] involving many different disciplines such as mathematics, topology, physics,[94] social systems,[95] population modeling, biology, meteorology, astrophysics, information theory, computational neuroscience, pandemic crisis management,[16][17] etc.

A popular but inaccurate analogy for chaos

The sensitive dependence on initial conditions (i.e., butterfly effect) has been illustrated using the following folklore:[92]

For want of a nail, the shoe was lost.

For want of a shoe, the horse was lost.

For want of a horse, the rider was lost.

For want of a rider, the battle was lost.

For want of a battle, the kingdom was lost.

And all for the want of a horseshoe nail.

Based on the above, many people mistakenly believe that the impact of a tiny initial perturbation monotonically increases with time and that any tiny perturbation can eventually produce a large impact on numerical integrations. However, in 2008, Lorenz stated that he did not feel that this verse described true chaos but that it better illustrated the simpler phenomenon of instability and that the verse implicitly suggests that subsequent small events will not reverse the outcome (Lorenz, 2008 [96]). Based on the analysis, the verse only indicates divergence, not boundedness.[6] Boundedness is important for the finite size of a butterfly pattern.[6][96][97] In a recent study,[98] the characteristic of the aforementioned verse was recently denoted as "finite-time sensitive dependence".

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chaos_theory#Sensitivity_to_initial_conditions

![[x,y]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/1b7bd6292c6023626c6358bfd3943a031b27d663)

![{\displaystyle \psi _{n+1}({\vec {r}},t)=\int K({\vec {r}}-{\vec {r}}^{,},t)f[\psi _{n}({\vec {r}}^{,},t)]d{\vec {r}}^{,}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/dbad9689ef6e3759ba8c806bbf568a7d3ff90518)

![{\displaystyle f[\psi _{n}({\vec {r}},t)]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/9fa3ba17d6e2b56466d57d8b60a2e46ec4925b90)

![{\displaystyle \psi \rightarrow G\psi [1-\tanh(\psi )]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/fec62ff5ebcf9fac8e71b101d6d2da0ef37f2df2)

![{\displaystyle f[\psi ]=\psi ^{2}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/331a4c25ef04f99d8d77f2be74bf1fa8a4ec21b2)

![{\displaystyle K({\vec {r}}-{\vec {r}}^{,},L)={\frac {ik\exp[ikL]}{2\pi L}}\exp[{\frac {ik|{\vec {r}}-{\vec {r}}^{,}|^{2}}{2L}}]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/634f66d2d768bec45cbd9d5b17fea78dd2d2ef88)

No comments:

Post a Comment