above.

The Shangri-Las - Leader of the Pack (1964) Stereo HQ Audio

The Deltaproteobacteria are a class of Proteobacteria.[1] All species of this group are, like all Proteobacteria, Gram-negative.

The Deltaproteobacteria comprise a branch of predominantly aerobic genera, the fruiting body-forming Myxobacteria which release myxospores in unfavorable environments, and a branch of strictly anaerobic genera, which contains most of the known sulfate- (Desulfovibrio, Desulfobacter, Desulfococcus, Desulfonema, etc.) and sulfur-reducing bacteria (e.g. Desulfuromonasspp.) alongside several other anaerobic bacteria with different physiology (e.g. ferric iron-reducing Geobacter spp. and syntrophicPelobacter and Syntrophus spp.).

A pathogenic intracellular deltaproteobacterium has recently been identified.[2]

It has been proposed that the Deltaproteobacteria be split into four new phyla: Desulfobacterota, Myxococcota, Bdellovibrionota, and SAR324 (a placeholder name pending the description of type material).[3]

| Deltaproteobacteria | |

|---|---|

| |

| Desulfovibrio vulgaris | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | Deltaproteobacteria |

| Orders | |

Phylogeny[edit]

The currently accepted taxonomy is based on the List of Prokaryotic names with Standing in Nomenclature (LPSN) [4] and National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI)[5] and the phylogeny is based on 16S rRNA-based LTP release 111 by 'The All-Species Living Tree' Project[6]

| Thiobacteria |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes:

♠ Strains found at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) but not listed in the List of Prokaryotic names with Standing in Nomenclature (LSPN)

♣ International Journal of Systematic Bacteriology or International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology (IJSB/IJSEM) published species that are in press.

The Deltaproteobacteria are a class of Proteobacteria.[1] All species of this group are, like all Proteobacteria, Gram-negative.

The Deltaproteobacteria comprise a branch of predominantly aerobic genera, the fruiting body-forming Myxobacteria which release myxospores in unfavorable environments, and a branch of strictly anaerobic genera, which contains most of the known sulfate- (Desulfovibrio, Desulfobacter, Desulfococcus, Desulfonema, etc.) and sulfur-reducing bacteria (e.g. Desulfuromonasspp.) alongside several other anaerobic bacteria with different physiology (e.g. ferric iron-reducing Geobacter spp. and syntrophicPelobacter and Syntrophus spp.).

A pathogenic intracellular deltaproteobacterium has recently been identified.[2]

It has been proposed that the Deltaproteobacteria be split into four new phyla: Desulfobacterota, Myxococcota, Bdellovibrionota, and SAR324 (a placeholder name pending the description of type material).[3]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deltaproteobacteria

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lithoautotroph

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nitrospirae

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Candidate_phyla_radiation

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Select_agent

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blain_(animal_disease)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Comammox

Modern scholarship suggests that "gloss-anthrax" was not the same disease as modern-day anthrax, but instead could have been foot-and-mouth disease, or a viral infection with a secondary Fusobacterium necrophorum infection.[4] It has also been suggested that it may have been due to an extinct variant strain of true anthrax.[4]Other sources also report epizootics known as "blain" or "black-blain" in the 13th and 14th centuries,[5] but it is not clear if the disease involved was the same as "gloss-anthrax".

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blain_(animal_disease)

Fusobacterium necrophorum is a species of bacteria responsible for Lemierre's syndrome and other medical problems.

| Fusobacterium necrophorum | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Bacteria |

| Phylum: | Fusobacteria |

| Class: | Fusobacteriia |

| Order: | Fusobacteriales |

| Family: | Fusobacteriaceae |

| Genus: | Fusobacterium |

| Species: | F. necrophorum |

| Binomial name | |

| Fusobacterium necrophorum (Flügge 1886) Moore and Holdeman 1969[1] | |

F. necrophorum is responsible for 10% of acute sore throats,[3] 21% of recurrent sore throats[4][5] and 23% of peritonsillar abscesses[6] with the remainder being caused by Group A streptococci or viruses. Other complications from F. necrophorum include meningitis, complicated by thrombosis of the internal jugular vein, thrombosis of the cerebral veins,[7] and infection of the urogenital and the gastrointestinal tracts.[8]

Although this infection is rare, researchers agree that this diagnosis should be considered in a septicaemic patient with thrombosis in an unusual site, and underlying malignancy should be excluded in cases of confirmed F. necrophorum occurring at sites caudal to the head.[9]

The above statistical analysis is dated, necessarily. A 2015 study of young adult students presenting to a single clinic in Alabama had F. necrophorum as the predominate causative organism for pharyngitis 21% of the time (and found in 9% of asymptomatic students).[10] In the same study, Group A Streptococcus was found in 10% of pharyngitis patients (1% of asymptomatic students).

F. necrophorum infection (also called F-throat[11]) usually responds to treatment with penicillin or metronidazole, but penicillin treatment for persistent pharyngitis appears anecdotally to have a higher relapse rate, although the reasons are unclear.[citation needed]This bacterium has been found to be associated with the foot disease thrush in horses. Thrush is a common infection that occurs on the hoof of a horse, specifically in the region of the frog. F. necrophorum occurs naturally in the animal's environment, especially in wet, muddy, or unsanitary conditions, such as an unclean stall.[12][13] Horses with deep clefts, or narrow or contracted heels are more at-risk to develop thrush.

F. necrophorum is also a cause for lameness in sheep. Its infection is commonly called scald. It can last for several years on land used by either sheep or cattle, and is found on most land of this type throughout the world. Due to its survival length in these areas, it is unrealistic to try to remove it. Sheep most often get scald due to breakage or weakness of the skin surrounding the hoof. This can occur due to strong footbaths, sandy soils, mild frostbite, or prolongened waterlogging of a field, and results in denaturing of the skin between the cleats.[14]

F. necrophorum is the cause of necrotic laryngitis ("calf diphtheria")[15] and liver abscesses[16] in cattle.

- See also Blain, an archaic disease of uncertain etiology.

Machado, Vinícius Silva (17 March 2014). "Subcutaneous Immunization with Inactivated Bacterial Components and Purified Protein of Escherichia coli, Fusobacterium necrophorum and Trueperella pyogenes Prevents Puerperal Metritis in Holstein Dairy Cows". PLOS One. 9 (3): e91734. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0091734. PMC 3956715. PMID 24638139.

External links[edit]

- Danvers Child, CJF (7 May 2011). "The Lowdown on Thrush".

- ^ Ensminger, M. E. (1990). Horses and Horsemanship: Animal Agriculture Series(Sixth ed.). Danville, IL: Interstate Publishers. p. 62. ISBN 0-8134-2883-1.

- ^ "Lameness in Sheep" (PDF). defra Gov.uk. Archived from the original (PDF)on 16 December 2008.

- ^ Campbell, John. "Necrotic Laryngitis in Cattle". MSD Manual Veterinary Manual. Merck & Co.

- ^ Foreman, Jonathan. "Liver Abscesses in Cattle". MSD Manual Veterinary Manual. Merck & Co.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fusobacterium_necrophorum

Allergies, also known as allergic diseases, are a number of conditions caused by hypersensitivity of the immune system to typically harmless substances in the environment.[12] These diseases include hay fever, food allergies, atopic dermatitis, allergic asthma, and anaphylaxis.[2] Symptoms may include red eyes, an itchy rash, sneezing, a runny nose, shortness of breath, or swelling.[1] Food intolerances and food poisoning are separate conditions.[4][5]

Common allergens include pollen and certain foods.[12] Metals and other substances may also cause such problems.[12] Food, insect stings, and medications are common causes of severe reactions.[3] Their development is due to both genetic and environmental factors.[3] The underlying mechanism involves immunoglobulin E antibodies(IgE), part of the body's immune system, binding to an allergen and then to a receptor on mast cells or basophilswhere it triggers the release of inflammatory chemicals such as histamine.[13] Diagnosis is typically based on a person's medical history.[4] Further testing of the skin or blood may be useful in certain cases.[4] Positive tests, however, may not mean there is a significant allergy to the substance in question.[14]

Early exposure to potential allergens may be protective.[6] Treatments for allergies includes avoidance of known allergens, and the use of medications such as steroids and antihistamines.[7] In severe reactions, injectable adrenaline (epinephrine) is recommended.[8] Allergen immunotherapy, which gradually exposes people to larger and larger amounts of allergen, is useful for some types of allergies such as hay fever and reactions to insect bites.[7] Its use in food allergies is unclear.[7]

Allergies are common.[11] In the developed world, about 20% of people are affected by allergic rhinitis,[15] about 6% of people have at least one food allergy,[4][6] and about 20% have atopic dermatitis at some point in time.[16]Depending on the country about 1–18% of people have asthma.[17][18] Anaphylaxis occurs in between 0.05–2% of people.[19] Rates of many allergic diseases appear to be increasing.[8][20][21] The word "allergy" was first used by Clemens von Pirquet in 1906.[3]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Allergy

Dust mite allergy, also known as house dust allergy, is a sensitization and allergic reaction to the droppings of house dust mites. The allergy is common[1][2] and can trigger allergic reactions such as asthma, eczema or itching. It is the manifestation of a parasitosis[citation needed]. The mite's gut contains potent digestive enzymes (notably peptidase 1) that persist in their feces and are major inducers of allergic reactions such as wheezing. The mite's exoskeleton can also contribute to allergic reactions. Unlike scabies mites or skin follicle mites, house dust mites do not burrow under the skin and are not parasitic.[3]

The symptoms can be avoided or alleviated by a number of measures. In general, cutting down mite numbers may reduce these reactions while others say efforts to remove these mites from the environment have not been found to be effective.[4]Immunotherapy may be useful in those affected.[4] Subcutaneous injections have better evidence than under the tongue dosing.[5]Topical steroids as nasal spray or inhalation may be used.[6]

Severe dust mite infestation in the home has been linked to atopic dermatitis, and epidermal barrier damage has been documented.[7]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dust_mite_allergy

Scarlet fever is a disease resulting from a group A streptococcus (group A strep) infection, also known as Streptococcus pyogenes.[1] The signs and symptoms include a sore throat, fever, headaches, swollen lymph nodes, and a characteristic rash.[1] The rash is red and feels like sandpaper and the tongue may be red and bumpy.[1] It most commonly affects children between five and 15 years of age.[1]

Scarlet fever affects a small number of people who have strep throat or streptococcal skin infections.[1] The bacteria are usually spread by people coughing or sneezing.[1] It can also be spread when a person touches an object that has the bacteria on it and then touches their mouth or nose.[1] The characteristic rash is due to the erythrogenic toxin, a substance produced by some types of the bacterium.[1][4] The diagnosis is typically confirmed by culturing the throat.[1]

As of 2020 there is no vaccine.[5] Prevention is by frequent handwashing, not sharing personal items, and staying away from other people when sick.[1] The disease is treatable with antibiotics, which prevent most complications.[1]Outcomes with scarlet fever are typically good if treated.[3] Long-term complications as a result of scarlet fever include kidney disease, rheumatic heart disease, and arthritis.[1] In the early 20th century, before antibiotics were available, it was a leading cause of death in children.[6][7] An antitoxin was produced before antibiotics; however, it was never made in sufficient quantities, and could not be used to treat any other disease as antibiotics can.

There have been signs of antibiotic resistance, and there have been recent outbreaks in Hong Kong in 2011 and in the UK in 2014, with occurrence rising 68% in the UK in the four years up to 2018. Research published in October 2020 has shown that infection of the bacterium by three viruses has led to stronger strains of the bacterium.[5]

| Complications | Glomerulonephritis, rheumatic heart disease, arthritis[1] |

|---|

The rash of scarlet fever, which is what differentiates this disease from an isolated group A strep pharyngitis (or strep throat), is caused by specific strains of group A streptococcus which produce a pyrogenic exotoxin.[14] These toxin-producing strains cause scarlet fever in people who do not already have antitoxin antibodies. Streptococcal pyrogenic exotoxins A, B, and C (speA, speB, and speC) have been identified. The pyrogenic exotoxins are also called erythrogenic toxins and cause the erythematous rash of scarlet fever.[14] The strains of group A streptococcus that cause scarlet fever need specific bacteriophages for there to be pyrogenic exotoxin production. Specifically, bacteriophage T12 is responsible for the production of speA.[21] Streptococcal Pyrogenic Exotoxin A, speA, is the one which is most commonly associated with cases of scarlet fever which are complicated by the immune-mediated sequelae acute rheumatic fever and post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis.[12]

These toxins are also known as "superantigens" because they are able to cause an extensive immune response within the body through activation of some of the main cells responsible for the person's immune system.[19] The body responds to these toxins by making antibodies to those specific toxins. However, those antibodies do not completely protect the person from future group A streptococcal infections, because there are 12 different pyrogenic exotoxins possible.[14]

The disease is caused by secretion of pyrogenic exotoxins by the infecting Streptococcus bacteria.[22][23] Streptococcal pyrogenic exotoxin A (speA) is probably the best studied of these toxins. It is carried by the bacteriophage T12 which integrates into the streptococcal genome from where the toxin is transcribed. The phage itself integrates into a serine tRNA gene on the chromosome.[24]

The T12 virus itself has not been placed into a taxon by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. It has a double-stranded DNA genome and on morphological grounds appears to be a member of the Siphoviridae.[citation needed]

The speA gene was cloned and sequenced in 1986.[25] It is 753 base pairs in length and encodes a 29.244 kiloDalton (kDa) protein. The protein contains a putative 30- amino-acid signal peptide; removal of the signal sequence gives a predicted molecular weight of 25.787 kDa for the secreted protein. Both a promoter and a ribosome binding site (Shine-Dalgarno sequence) are present upstream of the gene. A transcriptional terminator is located 69 bases downstream from the translational termination codon. The carboxy terminal portion of the protein exhibits extensive homology with the carboxy terminus of Staphylococcus aureus enterotoxins B and C1.[citation needed]

Streptococcal phages other than T12 may also carry the speA gene.[26]

- Viral exanthem: Viral infections are often accompanied by a rash which can be described as morbilliform or maculopapular. This type of rash is accompanied by a prodromal period of cough and runny nose in addition to a fever, indicative of a viral process.[15]

- Allergic or contact dermatitis: The erythematous appearance of the skin will be in a more localized distribution rather than the diffuse and generalized rash seen in scarlet fever.[13]

- Drug eruption: These are potential side effects of taking certain drugs such as penicillin. The reddened maculopapular rash which results can be itchy and be accompanied by a fever.[28]

- Kawasaki disease: Children with this disease also present a strawberry tongue and undergo a desquamative process on their palms and soles. However, these children tend to be younger than 5 years old, their fever lasts longer (at least five days), and they have additional clinical criteria (including signs such as conjunctival redness and cracked lips), which can help distinguish this from scarlet fever.[29]

- Toxic shock syndrome: Both streptococcal and staphylococcal bacteria can cause this syndrome. Clinical manifestations include diffuse rash and desquamation of the palms and soles. It can be distinguished from scarlet fever by low blood pressure, lack of sandpaper texture for the rash, and multi-organ system involvement.[30]

- Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome: This is a disease that occurs primarily in young children due to a toxin-producing strain of the bacteria Staphylococcus aureus. The abrupt start of the fever and diffused sunburned appearance of the rash can resemble scarlet fever. However, this rash is associated with tenderness and large blister formation. These blisters easily pop, followed by causing the skin to peel.[31]

- Staphylococcal scarlet fever: The rash is identical to the streptococcal scarlet fever in distribution and texture, but the skin affected by the rash will be tender.[8]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scarlet_fever

Tropomyosin, the major allergen in dust mites, is also responsible for shellfish allergy.[10][11] Exposure to inhaled tropomyosins from dust mites is thought to be the primary sensitizer for shellfish allergy, an example of inhalant-to-food cross-reactivity.[12] Epidemiological surveys have confirmed correlation between shellfish and dust mite sensitizations.[13] An additional confirmation was seen in Orthodox Jews with no history of shellfish consumption, in that skin tests confirming dust mite allergy were also positive for shellfish tropomyosin.[10][13] In addition to tropomyosin, the proteins arginine kinase and hemocyanin seem to have a role in cross-reactivity to dust mites.[14]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dust_mite_allergy

Shellfish allergy is among the most common food allergies. "Shellfish" is a colloquial and fisheries term for aquaticinvertebrates used as food, including various species of molluscs such as clams, mussels, oysters and scallops, crustaceans such as shrimp, lobsters and crabs, and cephalopods such as squid and octopus. Shellfish allergy is an immune hypersensitivity to proteins found in shellfish. Symptoms can be either rapid or gradual in onset. The latter can take hours to days to appear. The former may include anaphylaxis, a potentially life-threatening condition which requires treatment with epinephrine. Other presentations may include atopic dermatitis or inflammation of the esophagus.[2] Shellfish is one of the eight common food allergens, responsible for 90% of allergic reactions to foods: cow's milk, eggs, wheat, shellfish, peanuts, tree nuts, fish, and soy beans.[3][4]

Unlike early childhood allergic reactions to milk and eggs, which often lessen as the children age,[5] shellfish allergy tends to first appear in school-age children and older, and persist in adulthood.[6] Strong predictors for adult-persistence are anaphylaxis, high shellfish-specific serum immunoglobulin E (IgE) and robust response to the skin prick test. Adult onset of fish allergy is common in workers in the shellfish catching and processing industry.[7][8]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shellfish_allergy

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scarlet_fever

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dust_mite_allergy

The Shangri-Las - Leader of the Pack (1964) Stereo HQ Audio

Numbered Diseases of Childhood CL1 (you) | |

|---|---|

| Diseases | |

Hypersensitivity (also called hypersensitivity reaction or intolerance) refers to undesirable reactions produced by the normal immune system, including allergies and autoimmunity. They are usually referred to as an over-reaction of the immune system and these reactions may be damaging and uncomfortable. This is an immunologic term and is not to be confused with the psychiatric term of being hypersensitive which implies to an individual who may be overly sensitive to physical (ie sound, touch, light, etc.) and/or emotional stimuli. Although there is a relation between the two - studies have shown that those individuals that have ADHD (a psychiatric disorder) are more likely to have hypersensitivity reactions such as allergies, asthma, eczema than those who do not have ADHD.[1]

Hypersensitivity reactions can be classified into four types.

Type I - IgE mediated immediate reaction

Type II- Antibody-mediated cytotoxic reaction (IgG or IgM antibodies)

Type III- Immune complex-mediated reaction

Type IV- Cell-mediated, delayed hypersensitivity reaction[2]

The first three types are considered immediate hypersensitivity reactions because they occur within 24 hours. The fourth type is considered a delayed hypersensitivity reaction because it usually occurs more than 12 hours after exposure to the allergen, with a maximal reaction time between 48 and 72 hours.[3]

Immunologic aspects of hypersensitivity reactionsTypeAlternative namesAntibodies or Cell MediatorsImmunologic ReactionExamplesI

- Allergy

- Immediate

- Anaphylactic

Fast response which occurs in minutes, rather than multiple hours or days. Free antigens cross link the IgE on mast cells and basophils which causes a release of vasoactive biomolecules. Testing can be done via skin test for specific IgE.[5]

Antibody (IgM or IgG) binds to antigen on a target cell, which is actually a host cell that is perceived by the immune system as foreign, leading to cellular destruction via the MAC. Testing includes both the direct and indirect Coombs test.[6]

- Autoimmune hemolytic anemia

- Rheumatic heart disease

- Thrombocytopenia

- Erythroblastosis fetalis

- Goodpasture's syndrome

- Graves' disease

- Myasthenia gravis

- Pemphigus vulgaris

Antibody (IgG) binds to soluble antigen, forming a circulating immune complex. This is often deposited in the vessel walls of the joints and kidney, initiating a local inflammatory reaction.[7]

- Serum sickness

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Arthus reaction

- Post streptococcal glomerulonephritis

- Membranous nephropathy

- Reactive arthritis

- Lupus nephritis

- Systemic lupus erythematosus

- Extrinsic allergic alveolitis(hypersensitivity pneumonitis)

- Delayed,[5][6]

- cell-mediated immune memory response,

- Antibody-independent

Cells

T helper cells (specifically Th1 cells) are activated by an antigen presenting cell. When the antigen is presented again in the future, the memory Th1 cells will activate macrophages and cause an inflammatory response. This ultimately can lead to tissue damage.[8]

- Contact dermatitis, including Urushiol-induced contact dermatitis (poison ivy rash).

- Mantoux test

- Chronic transplant rejection

- Multiple sclerosis[9]

- Coeliac disease

- Hashimoto's thyroiditis

- Granuloma annulare

In type III hypersensitivity reaction, an abnormal immune response is mediated by the formation of antigen-antibody aggregates called "immune complexes." They can precipitate in various tissues such as skin, joints, vessels, or glomeruli, and trigger the classical complement pathway. Complement activation leads to the recruitment of inflammatory cells (monocytes and neutrophils) that release lysosomal enzymes and free radicals at the site of immune complexes, causing tissue damage.

The most common diseases involving a type III hypersensitivity reaction are serum sickness, post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, farmers' lung (hypersensitivity pneumonitis), and rheumatoid arthritis.

The principle feature that separates type III reactions from other hypersensitivity reactions is that in type III reaction, the antigen-antibody complexes are pre-formed in the circulation before their deposition in tissues.[2]

A Type IV hypersensitivity reaction is mediated by T cells that provoke an inflammatory reaction against exogenous or endogenous antigens. In certain situations, other cells, such as monocytes, eosinophils, and neutrophils, can be involved. After antigen exposure, an initial local immune and inflammatory response occurs that attracts leukocytes. The antigen engulfed by the macrophages and monocytes is presented to T cells, which then becomes sensitized and activated. These cells then release cytokines and chemokines, which can cause tissue damage and may result in illnesses.

Examples of illnesses resulting from type IV hypersensitivity reactions include contact dermatitis and drug hypersensitivity. Type IV reactions are further subdivided into type IVa, IVb, IVc, and IVd based on the type of T cell (CD4 T-helper type 1 and type 2 cells) involved and the cytokines/chemokines produced.

Immediate hypersensitivity reactions[edit]

The treatment of immediate hypersensitivity reactions includes the management of anaphylaxis with intramuscular adrenaline (epinephrine), oxygen, intravenous (IV) antihistamine, support blood pressure with IV fluids, avoid latex gloves and equipment in patients who are allergic, and surgical procedures such as tracheotomy if there is severe laryngeal edema.

- Allergic bronchial asthma can be treated with any of the following: inhaled short- and long-acting bronchodilators (anticholinergics) along with inhaled corticosteroids, leukotriene antagonists, use of disodium cromoglycate, and environmental control. Experimentally, a low dose of methotrexate or cyclosporin and omalizumab (a monoclonal anti-IgE antibody) has been used.

- Treatment of autoimmune disorders (e.g., SLE) include one or a combination of NSAIDs and hydroxychloroquine, azathioprine, methotrexate, mycophenolate, cyclophosphamide, low dose IL-2, intravenous immunoglobulins, and belimumab.

- Omalizumab is a monoclonal antibody that interacts with the binding site of the high-affinity IgE receptor on mast cells. It is an engineered, humanized recombinant immunoglobulin. Moderate to severe allergic bronchial asthma can improve with omalizumab.[12]

Delayed hypersensitivity reactions[edit]

Treatment of type 4 HR involves the treatment of the eliciting cause.

- The most common drugs to treat tuberculosis include isoniazid, rifampin, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide. For drug-resistant TB, a combination of antibiotics such as amikacin, kanamycin, or capreomycin should be used.

- The most common drugs to treat leprosy include rifampicin and clofazimine in combination with dapsone for multibacillary leprosy. A single dose of antimicrobial combination to cure single lesion paucibacillary leprosy comprises ofloxacin, rifampicin, and minocycline.

- Praziquantel can be useful for treating infections caused by all Schistosoma species.

- Hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine can use in the therapy of sarcoidosis involving the skin, lungs, and the nervous system.

- The use of anti-TNF monoclonal antibodies such as adalimumab and certolizumab have been approved for Crohn disease.[13]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hypersensitivity

Arriving at Thebes, a city in turmoil, Oedipus encounters the Sphinx, a legendary beast with the head and breast of a woman, the body of a lioness, and the wings of an eagle. The Sphinx, perched on a hill, was devouring Thebans and travellers one by one if they could not solve her riddle.

The precise riddle asked by the Sphinx varied in early traditions, and is not explicitly stated in Oedipus Rex, as the event precedes the play. However, according to the most widely regarded version of the riddle, the Sphinx asks "what is the creature that walks on four legs in the morning, two legs at noon, and three in the evening?" Oedipus, blessed with great intelligence, answers correctly: "man" (Greek: anthrôpos), who crawls on all fours as an infant; walks upright in maturity; and leans on a stick in old age.[8]:463

Bested by the prince, the Sphinx throws herself from a cliff, thereby ending the curse.[9] Oedipus' reward for freeing Thebes from the Sphinx is kingship to the city and the hand of its dowager queen, Jocasta. None, at that point, realize that Jocasta is Oedipus' true mother.[10] Thus, unbeknownst to either character, the remaining prophecy has been fulfilled.

The oracle told to Laius tells only of the patricide, whereas the incest is missing. Prompted by Jocasta's recollection, Oedipus reveals the prophecy which caused him to leave Corinth (lines 791–3):

Fate, free will, or tragic flaw[edit]

Fate is a motif that often occurs in Greek writing, tragedies in particular. Likewise, where the attempt to avoid an oracle is the very thing that enables it to happen is common to many Greek myths. For example, similarities to Oedipus can be seen in the myth of Perseus' birth.

They point to Jocasta's initial disclosure of the oracle at lines 711–14. In Greek, the oracle cautions: "hôs auton hexoi moira pros paidos thanein/ hostis genoit emou te kakeinou para." The two verbs in boldface indicate what is called a "future more vivid" condition: if a child is born to Laius, his fate to be killed by that child will overtake him.[26]

Whatever the meaning of Laius's oracle, the one delivered to Oedipus is clearly unconditional. Given the modern conception of fate and fatalism, readers of the play have a tendency to view Oedipus as a mere puppet controlled by greater forces; a man crushed by the gods and fate for no good reason. This, however, is not an entirely accurate reading. While it is a mythological truism that oracles exist to be fulfilled, oracles do not cause the events that lead up to the outcome. In his landmark essay "On Misunderstanding the Oedipus Rex",[27] E.R. Dodds draws upon Bernard Knox's comparison with Jesus' prophecy at the Last Supper that Peter would deny him three times. Jesus knows that Peter will do this, but readers would in no way suggest that Peter was a puppet of fate being forced to deny Christ. Free will and predestinationare by no means mutually exclusive, and such is the case with Oedipus.

The oracle delivered to Oedipus is what is often called a "self-fulfilling prophecy," whereby a prophecy itself sets in motion events that conclude with its own fulfilment.[28]This, however, is not to say that Oedipus is a victim of fate and has no free will. The oracle inspires a series of specific choices, freely made by Oedipus, which lead him to kill his father and marry his mother. Oedipus chooses not to return to Corinth after hearing the oracle, just as he chooses to head toward Thebes, to kill Laius, and to take Jocasta specifically as his wife. In response to the plague at Thebes, he chooses to send Creon to the Oracle for advice and then to follow that advice, initiating the investigation into Laius' murder. None of these choices are predetermined.

Another characteristic of oracles in myth is that they are almost always misunderstood by those who hear them; hence Oedipus misunderstanding the significance of the Delphic Oracle. He visits Delphi to find out who his real parents are and assumes that the Oracle refuses to answer that question, offering instead an unrelated prophecy which forecasts patricide and incest. Oedipus' assumption is incorrect, the Oracle does, in a way, answer his question. On closer analysis the oracle contains essential information which Oedipus seems to neglect. The wording of the Oracle: "I was doomed to be murderer of the father that begot me" refers to Oedipus' real, biological father. Likewise the mother with polluted children is defined as the biological one. The wording of the drunken guest on the other hand: "you are not your father's son" defines Polybus as only a foster father to Oedipus. The two wordings support each other and point to the "two set of parents" alternative. Thus the question of two set of parents, biological and foster, is raised. Oedipus' reaction to the Oracle is irrational: he states he did not get any answer and he flees in a direction away from Corinth, showing that he firmly believed at the time that Polybus and Merope are his real parents.

The scene with the drunken guest constitutes the end of Oedipus' childhood. He can no longer ignore a feeling of uncertainty about his parentage. However, after consulting the Oracle this uncertainty disappears, strangely enough, and is replaced by a totally unjustified certainty that he is the son of Merope and Polybus. We have said that this irrational behaviour—his hamartia, as Aristotle puts it—is due to the repression of a whole series of thoughts in his consciousness, in fact everything that referred to his earlier doubts about his parentage.[29]

The exploration of the theme of state control in Oedipus Rex is paralleled by the examination of the conflict between the individual and the state in Antigone. The dilemma that Oedipus faces here is similar to that of the tyrannical Creon: each man has, as king, made a decision that his subjects question or disobey; and each king misconstrues both his own role as a sovereign and the role of the rebel. When informed by the blind prophet Tiresias that religious forces are against him, each king claims that the priest has been corrupted. It is here, however, that their similarities come to an end: while Creon sees the havoc he has wreaked and tries to amend his mistakes, Oedipus refuses to listen to anyone.

Sophocles uses dramatic irony to present the downfall of Oedipus. At the beginning of the story, Oedipus is portrayed as "self-confident, intelligent and strong willed."[30]By the end, it is within these traits that he finds his demise.

One of the most significant instances of irony in this tragedy is when Tiresias hints at Oedipus what he has done; that he has slain his own father and married his own mother (lines 457–60):[31]

The audience knows the truth and what would be the fate of Oedipus. Oedipus, on the other hand, chooses to deny the reality that has confronted him. He ignores the word of Tiresias and continues on his journey to find the supposed killer. His search for a murderer is yet another instance of irony. Oedipus, determined to find the one responsible for King Laius' death, announces to his people (lines 247–53):[8]:466–467

This is ironic as Oedipus is, as he discovers, the slayer of Laius, and the curse he wishes upon the killer, he has actually wished upon himself. Glassberg (2017) explains that “Oedipus has clearly missed the mark. He is unaware that he is the one polluting agent he seeks to punish. He has inadequate knowledge...”[32]

Literal and metaphorical references to eyesight appear throughout Oedipus Rex. Clear vision serves as a metaphor for insight and knowledge, yet the clear-eyed Oedipus is blind to the truth about his origins and inadvertent crimes. The prophet Tiresias, on the other hand, although literally blind, "sees" the truth and relays what is revealed to him. "Though Oedipus' future is predicted by the gods, even after being warned by Tiresias, he cannot see the truth or reality beforehand because his excessive pride has blinded his vision…"[33] Only after Oedipus gouges out his own eyes, physically blinding himself, does he gain prophetic ability, as exhibited in Oedipus at Colonus. It is deliberately ironic that the "seer" can "see" better than Oedipus, despite being blind. Tiresias, in anger, expresses such (lines 495–500):[34]:11

Sigmund Freud wrote a notable passage in Interpretation of Dreams regarding the destiny of Oedipus, as well as the Oedipus complex. He analyzes why this play, Oedipus Rex, written in Ancient Greece, is so effective even to a modern audience:[36]:279–280

Freud goes on to indicate, however, that the “primordial urges and fears” that are his concern are not found primarily in the play by Sophocles, but exist in the myth the play is based on. He refers to Oedipus Rex as a “further modification of the legend,” one that originates in a “misconceived secondary revision of the material, which has sought to exploit it for theological purposes.”[36]:247[37][38]

The first English-language adaption, Oedipus Rex (1957), was directed by Tyrone Guthrie and starred Douglas Campbell as Oedipus. In this version, the entire play is performed by the cast in masks (Greek: prosopon), as actors did in ancient Greek theatre.

The second English-language film version, Oedipus the King (1968), was directed by Philip Saville and filmed in Greece. Unlike Guthrie's film, this version shows the actors' faces, as well as boasting an all-star cast, including Christopher Plummer as Oedipus; Lilli Palmer as Jocasta; Orson Welles as Tiresias; Richard Johnson as Creon; Roger Livesey as the Shepherd; and Donald Sutherland as the Leading Member of the Chorus. Sutherland's voice, however, was dubbed by another actor. The film went a step further than the play by actually showing, in flashback, the murder of Laius (portrayed by Friedrich Ledebur). It also shows Oedipus and Jocasta in bed together, making love. Though released in 1968, this film was not seen in Europe or the US until the 1970s and 1980s after legal release and distribution rights were granted to video and television.

In 1986, an English-language version starring Michael Pennington, John Gielgud, and Claire Bloom, and directed by Don Taylor was produced by the BBC as part of a trilogy of fimed presentations of The Theban Plays. It presented the actors in modern dress.

In Italy, Pier Paolo Pasolini directed Edipo Re (1967), a modern interpretation of the play.

Toshio Matsumoto's film, Funeral Parade of Roses (1969), is a loose adaptation of the play and an important work of the Japanese New Wave.

In Colombia, writer Gabriel García Márquez adapted the story in Edipo Alcalde, bringing it to the real-world situation of Colombia at the time.

On the road to Thebes, Oedipus encounters an old man and his servants. The two begin to quarrel over whose chariot has the right of way. While the old man moves to strike the insolent youth with his scepter, Oedipus throws the man down from his chariot, killing him. Thus, the prophecy in which Oedipus slays his own father is fulfilled, as the old man—as Oedipus discovers later—was Laius, king of Thebes and true father to Oedipus.

As he grows to manhood, Oedipus hears a rumour that he is not truly the son of Polybus and his wife, Merope. He asks the Delphic Oracle who his parents really are. The Oracle seems to ignore this question, telling him instead that he is destined to "mate with [his] own mother, and shed/With [his] own hands the blood of [his] own sire." Desperate to avoid this terrible fate, Oedipus, who still believes that Polybus and Merope are his true parents, leaves Corinth for the city of Thebes.

Oedipus, King of Thebes, sends his brother-in-law, Creon, to ask advice of the oracle at Delphi, concerning a plague ravaging Thebes. Creon returns to report that the plague is the result of religious pollution, since the murderer of their former king, Laius, has never been caught. Oedipus vows to find the murderer and curses him for causing the plague.

Oedipus summons the blind prophet Tiresias for help. When Tiresias arrives he claims to know the answers to Oedipus's questions, but refuses to speak, instead telling him to abandon his search. Oedipus is enraged by Tiresias' refusal, and accuses him of complicity in Laius' murder. Outraged, Tiresias tells the king that Oedipus himself is the murderer ("You yourself are the criminal you seek"). Oedipus cannot see how this could be, and concludes that the prophet must have been paid off by Creon in an attempt to undermine him. The two argue vehemently, as Oedipus mocks Tiresias' lack of sight, and Tiresias retorts that Oedipus himself is blind. Eventually Tiresias leaves, muttering darkly that when the murderer is discovered he shall be a native citizen of Thebes, brother and father to his own children, and son and husband to his own mother.

Creon arrives to face Oedipus's accusations. The King demands that Creon be executed; however, the chorus persuades him to let Creon live. Jocasta, wife of first Laius and then Oedipus, enters and attempts to comfort Oedipus, telling him he should take no notice of prophets. As proof, she recounts an incident in which she and Laius received an oracle which never came true. The prophecy stated that Laius would be killed by his own son; instead, Laius was killed by bandits, at a fork in the road (τριπλαῖς ἁμαξιτοῖς, triplais amaxitois).

The mention of the place causes Oedipus to pause and ask for more details. Jocasta specifies the branch to Daulis on the way to Delphi. He asks Jocasta what Laius looked like, suddenly worried that Tiresias's first accusation was true. Oedipus then sends for the one surviving witness of the attack to be brought to the palace from the fields where he now works as a shepherd.

Jocasta, confused, asks Oedipus what the matter is, and he tells her. Many years ago, at a banquet in Corinth, a man drunkenly accused Oedipus of not being his father's son. Oedipus went to Delphi and asked the oracle about his parentage. Instead of answers he was given a prophecy that he would one day murder his father and sleep with his mother. Upon hearing this he resolved never to return to Corinth. While traveling he came to the very crossroads where Laius was killed, and encountered a carriage which attempted to drive him off the road. An argument ensued and Oedipus killed the travelers, including a man who matches Jocasta's description of Laius. Oedipus has hope, however, because the story is that Laius was murdered by several robbers. If the shepherd confirms that Laius was attacked by many men, then Oedipus is in the clear.

A man arrives from Corinth with the message that Oedipus's father has died. Oedipus, to the surprise of the messenger, is made ecstatic by this news, for it proves one half of the prophecy false, for now he can never kill his father. However, he still fears that he may somehow commit incest with his mother. The messenger, eager to ease Oedipus's mind, tells him not to worry, because Merope was not in fact his real mother.

It emerges that this messenger was formerly a shepherd on Mount Cithaeron, and that he was given a baby, which the childless Polybus then adopted. The baby, he says, was given to him by another shepherd from the Laius household, who had been told to get rid of the child. Oedipus asks the chorus if anyone knows who this man was, or where he might be now. They respond that he is the "same shepherd" who was witness to the murder of Laius, and whom Oedipus had already sent for. Jocasta, who has by now realized the truth, desperately begs Oedipus to stop asking questions, but he refuses and Jocasta runs into the palace.

When the shepherd arrives Oedipus questions him, but he begs to be allowed to leave without answering further. However, Oedipus presses him, finally threatening him with torture or execution. It emerges that the child he gave away was Laius's own son, and that Jocasta had given the baby to the shepherd to secretly be exposed upon the mountainside. This was done in fear of the prophecy that Jocasta said had never come true: that the child would kill his father.

Everything is at last revealed, and Oedipus curses himself and fate before leaving the stage. The chorus laments how even a great man can be felled by fate, and following this, a servant exits the palace to speak of what has happened inside. When Jocasta entered the house, she ran to the palace bedroom and hanged herself there. Shortly afterward, Oedipus entered in anguish, calling on his servants to bring him a sword. He then raged through the house, until he came on Jocasta's body. Giving a cry, Oedipus took her down and removed the long gold pins that held her dress together, before plunging them into his own eyes in despair, blinding himself.

Oedipus, blind, now exits the palace and begs to be exiled as soon as possible. Creon enters, saying that Oedipus shall be taken into the house until oracles can be consulted regarding what is best to be done. Oedipus's two daughters (and half-sisters), Antigone and Ismene, are sent out and Oedipus laments their having been born to such a cursed family. He begs Creon to watch over them in hopes that they will live where there is opportunity for them and to have a better life than their father (half-brother). Creon agrees, before sending Oedipus back into the palace.

On an empty stage the chorus repeats the common Greek maxim, that no man should be considered fortunate until he is dead.[11]

Oedipus Rex, also known by its Greek title, Oedipus Tyrannus (Ancient Greek: Οἰδίπους Τύραννος, pronounced [oidípoːs týrannos]), or Oedipus the King, is an Athenian tragedy by Sophocles that was first performed around 429 BC.[1] Originally, to the ancient Greeks, the title was simply Oedipus (Οἰδίπους), as it is referred to by Aristotle in the Poetics. It is thought to have been renamed Oedipus Tyrannus to distinguish it from another of Sophocles's plays, Oedipus at Colonus. In antiquity, the term "tyrant" referred to a ruler with no legitimate claim to rule, but it did not necessarily have a negative connotation.[2][3][4]

Of Sophocles' three Theban plays that have survived, and that deal with the story of Oedipus, Oedipus Rex was the second to be written. However, in terms of the chronology of events that the plays describe, it comes first, followed by Oedipus at Colonus and then Antigone.

Prior to the start of Oedipus Rex, Oedipus has become the king of Thebes while unwittingly fulfilling a prophecy that he would kill his father, Laius (the previous king), and marry his mother, Jocasta (whom Oedipus took as his queen after solving the riddle of the Sphinx). The action of Sophocles's play concerns Oedipus's search for the murderer of Laius in order to end a plague ravaging Thebes, unaware that the killer he is looking for is none other than himself. At the end of the play, after the truth finally comes to light, Jocasta hangs herself while Oedipus, horrified at his patricide and incest, proceeds to gouge out his own eyes in despair.

In his Poetics, Aristotle refers several times to the play in order to exemplify aspects of the genre.[5][6]

| Oedipus Rex | |

|---|---|

Louis Bouwmeester as Oedipus in a Dutch production of Oedipus Rex, c. 1896 | |

| Written by | Sophocles |

| Chorus | Theban Elders |

| Characters | |

| Mute | Daughters of Oedipus(Antigone and Ismene) |

| Date premiered | c. 429 BC |

| Place premiered | Theatre of Dionysus, Athens |

| Original language | Classical Greek |

| Series | Theban Plays |

| Genre | Tragedy |

| Setting | Thebes |

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oedipus_Rex

Polybus (Ancient Greek: Πόλυβος) is a figure in Greek mythology. He was the king of Corinth and husband of either Periboea or Merope, a Dorian or Medusa, daughter of Orsilochus.[1]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polybus_of_Corinth

Photios I (Greek: Φώτιος, Phōtios; c. 810/820 – 6 February 893),[a] also spelled Photius[2] (/ˈfoʊʃəs/), was the ecumenical patriarch of Constantinople from 858 to 867 and from 877 to 886.[3] He is recognized in the Eastern Orthodox Church as Saint Photios the Great.

Photios the Great | |

|---|---|

Photios baptising the Bulgarians | |

| The Great, Confessor of the Faith, Equal to the Apostles, Pillar of Orthodoxy[1] | |

| Born | c. 810 Constantinople, Byzantine Empire |

| Died | c. 893 Bordi, Armenia |

| Venerated in | Eastern Orthodox Church |

| Canonized | 1847, Constantinople, Byzantine Empire by Anthimus VI of Constantinople |

| Feast | February 6 |

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Photios_I_of_Constantinople

A queen dowager, dowager queen or queen mother (compare: princess dowager, dowager princess or princess mother) is a title or status generally held by the widow of a king. In the case of the widow of an emperor, the title of empress dowager is used. Its full meaning is clear from the two words from which it is composed: queen indicates someone who served as queen consort (i.e. wife of a king), while dowager indicates a woman who holds the title from her deceased husband (a queen who rules in her own right as well as not due to marriage to a king is a queen regnant).

A queen mother is a dowager queen who is the mother of the reigning monarch. Currently (2019) there are four queens dowager: Kesang Choden of Bhutan (who is the only living queen grandmother worldwide), Norodom Monineath of Cambodia (who is also queen mother), Lisa Najeeb Halaby (Noor Al'Hussein) of Jordan, and Sirikit Kitiyakara of Thailand(who is also queen mother). Queen Ratna of Nepal was queen dowager until the abolition of the Nepalese monarchy in 2008.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Queen_dowager

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Isabella_of_Valois

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Isabella_of_France

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Margaret_of_France,_Queen_of_England

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Isabella_of_Angoulême

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Berengaria_of_Navarre

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eleanor_of_Aquitaine

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adeliza_of_Louvain

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mary_I_of_England

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mary_of_Guise

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mary,_Queen_of_Scots

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Margaret_Tudor

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yolande_of_Dreux,_Queen_of_Scotland

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saint_Margaret_of_Scotland

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mary_of_Modena

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Catherine_of_Braganza

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henrietta_Maria

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Helen_of_Zadar

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pedro_I_of_Brazil

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_VI_of_Portugal

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carlota_Joaquina_of_Spain

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maria_Anna_of_Austria

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eleanor_of_Austria

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elizabeth_of_Portugal

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Queen_Emma_of_Hawaii

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kamehameha_IV

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kamehameha_I

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kaʻahumanu

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Josephine_of_Leuchtenberg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Catherine_Stenbock

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Queen_dowager

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gustavus_Adolphus

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joan_of_Portugal

were not friends

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Louisa_Ulrika_of_Prussia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gustav_I_of_Sweden

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adolf_Frederick,_King_of_Sweden

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Margaret_of_France,_Queen_of_England

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sophia_of_Nassau

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oscar_II

| Lis Ulka of Prussia | |

|---|---|

Portrait by Ulrika Pasch | |

| Queen consort of Sweden | |

| Reign | 25 March 1751 – 12 February 1771 |

| Coronation | 26 November 1751 |

?

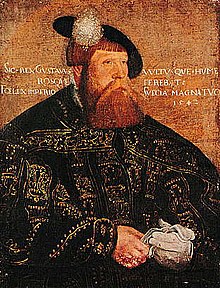

| Gustav I | |

|---|---|

Portrait by Jakob Bincks, 1542 | |

| King of Sweden | |

| Reign | 6 June 1523 – 29 September 1560 |

| Coronation | 12 January 1528 |

| Adolf Frederick | |

|---|---|

Adolf Frederick by Lorens Pasch the Younger | |

| King of Sweden | |

| Reign | 25 March 1751 – 12 February 1771 |

| Coronation | 26 November 1751 |

| Predecessor | Frederick I |

| Successor | Gustav III |

| Margaret of France | |

|---|---|

Statue at Lincoln Cathedral | |

| Queen consort of England | |

| Tenure | 8 September 1299 – 7 July 1307 |

| Sophia of Nassau | |

|---|---|

Queen Sophia c. 1884 | |

| Queen consort of Sweden | |

| Tenure | 18 September 1872 – 8 December 1907 |

| Oscar II | |

|---|---|

| |

| King of Sweden | |

| Reign | 18 September 1872 – 8 December 1907 |

| Coronation | 12 May 1873 |

| Predecessor | Charles XV |

| Successor | Gustaf V |

Roger Mortimer | |

|---|---|

| Earl of March Baron Mortimer of Wigmore | |

15th-century manuscript illustration depicting Roger Mortimer and Queen Isabella in the foreground. Background: Hugh Despenser the Younger on the scaffold, being emasculated. |

The affair badly damaged the reputation of women in senior French circles, contributing to the way that the Salic Law was implemented during subsequent arguments over the succession to the throne.[2] When Louis died unexpectedly in 1316, supporters of his eldest daughter Joan found that suspicions hung over her parentage following the scandal and that the French nobility were increasingly cautious over the concept of a woman inheriting the throne – Louis' brother, Philip took power instead.[25] Philip died unexpectedly young as well, and his younger brother Charles did not live long after remarrying after his coronation, similarly dying without male heirs. The interpretation of the Salic Law then placed the French succession in doubt. Despite Philip of Valois, the son of Charles of Valois, claiming the throne with French noble support, Edward III of England, the son of Isabella was able to press his own case, resulting in the ensuing Hundred Years War (1337–1453).[26]

The affair would also have an impact in European culture. Scholars studying the theme of courtly love have observed that the narratives about adulterous queens die out shortly after the Tour de Nesle scandal, suggesting that they became less acceptable or entertaining after the executions and imprisonments in the French royal family.[27]The story of the affair was used by the French dramatist Alexandre Dumas as the basis for his play La Tour de Nesle in 1832, "a romantic thriller reconstructing medieval crimes on a grand scale".[28] The Tour de Nesle guard-tower itself was destroyed in 1665.[15] Le Roi de fer (1955), the first novel of Maurice Druon's seven-volume series Les Rois maudits (The Accursed Kings), describes the affair and the subsequent executions in lurid and imaginative detail.

Margaret Mortimer | |

|---|---|

| Baroness Berkeley | |

Effigy of Margaret Mortimer at right hand of her son Maurice de Berkeley, 4th Baron Berkeley(d.1368), St Augustine's Abbey, Bristol | |

| Born | 2 May 1304[1] |

| Died | 5 May 1337 (age 33) |

Guy, Count of Flanders | |

|---|---|

Guy of Dampierre riding a horse. His surcoat bears the arms of the county of Flanders | |

| Born | c. 1226 |

| Died | 7 March 1305 |

Robert III | |

|---|---|

Robert's effigy on his seal | |

| Born | 1249 |

| Died | 17 September 1322 Ypres |

| Noble family | House of Dampierre |

| Spouse(s) | Blanche of Sicily Yolande II, Countess of Nevers |

| Father | Guy of Dampierre |

| Mother | Matilda of Béthune |

Yolande (Iolande) II | |

|---|---|

| Countess of Nevers, suo jure | |

Yolande II, Countess of Nevers | |

| Born | December 1247 Nevers |

| Died | 2 June 1280 (aged 32) |

| Noble family | House of Burgundy |

| Spouse(s) | John Tristan, Count of Valois Robert III, Count of Flanders |

| Father | Odo, Count of Nevers |

| Mother | Matilda II, Countess of Nevers |

Walloon Flanders

Walloon Flanders (Dutch: Waals Vlaanderen, French: Flandre wallonne) was a semi-independent part of the County of Flanders, composed of the burgraviates of Lille, Douai and Orchies. It is sometimes referred to as Lille–Douai–Orchies. The population of the region speak Walloon and Picardy dialects.

History[edit]

The term "Walloon Flanders" appeared after the French conquest and was fixed in the literature by the beginning of the 19th century.

Walloon Flanders was part of the County of Flanders from the early Middle Ages, but was ceded to the Kingdom of France from 1304 to 1369, by the Treaty of Athis-sur-Orge which concluded the Franco-Flemish War (1297-1305).[1] As a result it was to some degree institutionally distinct from the County of Flanders and in some lists it even features as one of the Seventeen Provinces. Furthermore, Walloon Flanders adhered to the Union of Arras in 1579, whereas the County of Flanders joined the Union of Utrecht.[2]

In 1678, Walloon Flanders was annexed to France after the Treaties of Nijmegen.[3]

Together with Maritime Flanders (Westhoek), it forms French Flanders, and is today the part of the Departement du Nord roughly corresponding with the Arrondissement of Lille and the Arrondissement of Douai.

Crusades and diplomacy with Mongols[edit]

Philip had various contacts with the Mongol power in the Middle East, including reception at the embassy of the Uyghur monk Rabban Bar Sauma, originally from the Yuan dynasty of China.[20] Bar Sauma presented an offer of a Franco-Mongol alliance with Arghun of the Mongol Ilkhanate in Baghdad. Arghun was seeking to join forces between the Mongols and the Europeans, against their common enemy the Muslim Mamluks. In return, Arghun offered to return Jerusalem to the Christians, once it was re-captured from the Muslims. Philip seemingly responded positively to the request of the embassy by sending one of his noblemen, Gobert de Helleville, to accompany Bar Sauma back to Mongol lands.[21] There was further correspondence between Arghun and Philip in 1288 and 1289,[22] outlining potential military cooperation. However, Philip never actually pursued such military plans.

In April 1305, the new Mongol ruler Öljaitü sent letters to Philip,[23] the Pope, and Edward I of England. He again offered a military collaboration between the Christian nations of Europe and the Mongols against the Mamluks. European nations attempted another Crusade but were delayed, and it never took place. On 4 April 1312, another Crusade was promulgated at the Council of Vienne. In 1313, Philip "took the cross", making the vow to go on a Crusade in the Levant, thus responding to Pope Clement V's call. He was, however, warned against leaving by Enguerrand de Marigny[24] and died soon after in a hunting accident.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philip_IV_of_France

After bringing the Flemish War to a victorious conclusion in 1305, Philip on 8 June 1306 ordered the silver content of new coinage to be raised back to its 1285 level of 3.96 grams of silver per livre.[35] To harmonize the strength of the old and new currencies, the debased coinage of 1303 was devalued accordingly by two-thirds.[35] The debtors were driven to penury by the need to repay their loans in the new, strong currency.[35] This led to rioting in Paris on 30 December 1306, forcing Philip to briefly seek refuge in the Paris Temple, the headquarters of the Knights Templar.[36]

Perhaps seeking to control the silver of the Jewish mints to put the revaluation to effect, Philip ordered the expulsion of the Jews on 22 July 1306 and confiscated their property on 23 August, collecting at least 140,000 LP with this measure.[35] With the Jews gone, Philip appointed royal guardians to collect the loans made by the Jews, and the money was passed to the Crown. The scheme did not work well. The Jews were regarded as comparatively honest, while the king's collectors were universally unpopular. Finally, in 1315, because of the "clamour of the people", the Jews were invited back with an offer of 12 years of guaranteed residence, free from government interference. In 1322, the Jews were expelled again by the King's successor, who did not honour his commitment.[37]

After a little over a month, Pope Clement V died of disease thought to be lupus, and in eight months Philip IV, at the age of forty-six, died in a hunting accident. This gave rise to the legend that de Molay had cited them before the tribunal of God, which became popular among the French population. Even in Germany, Philip's death was spoken of as a retribution for his destruction of the Templars, and Clement was described as shedding tears of remorse on his death-bed for three great crimes: the poisoning of Henry VII, Holy Roman Emperor, and the ruin of the Templars and Beguines.[47] Within fourteen years the throne passed rapidly through Philip's sons, who died relatively young, and without producing male heirs. By 1328, his male line was extinguished, and the throne had passed to the line of his brother, the House of Valois. (1300s)

In 1314, the daughters-in-law of Philip IV, Margaret of Burgundy (wife of Louis X) and Blanche of Burgundy (wife of Charles IV) were accused of adultery, and their alleged lovers (Phillipe d'Aunay and Gauthier d'Aunay) tortured, flayed and executed in what has come to be known as the Tour de Nesle affair (French: Affaire de la tour de Nesle).[48] A third daughter-in-law, Joan II, Countess of Burgundy (wife of Philip V), was accused of knowledge of the affairs.[48]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philip_IV_of_France

Louis X (4 October 1289 – 5 June 1316), called the Quarrelsome, the Headstrong, or the Stubborn (French: le Hutin), was King of France from 1314 to 1316 and King of Navarre as Louis I (Basque: Luis I a Nafarroakoa), from 1305 until his death in 1316. He abolished slavery, emancipated serfs who could pay their freedom, and readmitted Jews in the kingdom.

His short reign in France was marked by tensions with the nobility, due to fiscal and centralization reforms initiated by Enguerrand de Marigny, the Grand Chamberlain of France, under the reign of his father. Louis' uncle—Charles of Valois, leader of the feudalist party—managed to convince the king to execute Enguerrand de Marigny.

| Louis X | |

|---|---|

Miniature depiction from the Vie de saint Louis, c. 1330–1340 | |

| King of France (more...) | |

| Reign | 29 November 1314 – 5 June 1316 |

| Coronation | 24 August 1315, Reims |

| Predecessor | Philip IV |

| Successor | John I |

| King of Navarre | |

| Reign | 4 April 1305 – 5 June 1316 |

| Coronation | 1 October 1307, Pamplona |

| Predecessor | Joan I and Philip I |

| Successor | John I |

| Born | 4 October 1289 Paris, France |

| Died | 5 June 1316 (aged 26) Vincennes, Val-de-Marne, France |

| Burial | 7 June 1316[1] |

| Spouse | Margaret of Burgundy(m. 1305, d. 1315) Clementia of Hungary (m. 1315) |

| Issue | |

| House | Capet |

| Father | Philip IV of France |

| Mother | Joan I of Navarre |

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Louis_X_of_France

John I (15–20 November 1316), called the Posthumous (French: Jean Ier le Posthume, Occitan: Joan Ièr lo Postume), was king of France and Navarre, as the posthumous son and successor of Louis X, for the five days he lived in 1316. He is the youngest person to be king of France, the only one to have borne that title from birth, and the only one to hold the title for his entire life. His reign is the shortest of any French king.[note 1] Although considered a king today, his status was not recognized until chroniclers and historians in later centuries began numbering John II, thereby acknowledging John I's brief reign.[1]

John reigned for five days under the regency of his uncle, Philip the Tall of France, until his death on 20 November 1316. His death ended the three centuries of father-to-son succession to the French throne. The infant king was buried in the Basilica of Saint-Denis. He was succeeded by his uncle, Philip, whose contested legitimacy led to the re-affirmation of the Salic law, which excluded women from the line of succession to the French throne.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_I_of_France

Philip V (c. 1293 – 3 January 1322), known as the Tall (French: Philippe le Long), was Count of Poitiers and later King of France and Navarre (as Philip II). He reigned from 1316 to 1322.

As the second son of king Philip IV, he was granted an appanage, the County of Poitiers, while his elder brother, Louis X, inherited the throne in 1314. When Louis died in 1316, he left a daughter and a pregnant wife, Clementia of Hungary. Philip the Tall successfully claimed the regency. Queen Clementia gave birth to a boy, who was proclaimed king as John I, but the infant king lived only for five days.

At the death of his nephew, Philip immediately had himself crowned at Reims. However, his legitimacy was challenged by the party of Louis X's daughter Joan. Philip V successfully contested her claims for a number of reasons, including her youth, doubts regarding her paternity (her mother was involved in the Tour de Nesle Affair), and the Estates General's determination that women should be excluded from the line of succession to the French throne. The succession of Philip, instead of Joan, set the precedent for the French royal succession that would be known as the Salic law.

Philip V restored somewhat good relations with the County of Flanders, which had entered into open rebellion during his father's rule, but simultaneously his relations with Edward II of England worsened as the English king, who was also Duke of Guyenne, initially refused to pay him homage. A spontaneous popular crusade started in Normandy in 1320 aiming to liberate the Iberian Peninsula from the Moors. Instead the angry populace marched to the south attacking castles, royal officials, priests, lepers, and Jews.

Philip V engaged in a series of domestic reforms intended to improve the management of the kingdom. These reforms included the creation of an independent Court of Finances, the standardization of weights and measures, and the establishment of a single currency.

Philip V died from dysentery in 1322 without a male heir and was succeeded by his younger brother Charles IV.

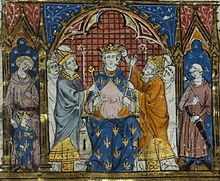

| Philip V | |

|---|---|

Contemporary miniature depicting the coronation of Philip V. | |

| King of France and Navarre (more...) | |

| Reign | 20 November 1316 – 3 January 1322 |

| Coronation | 9 January 1317 |

| Predecessor | John I |

| Successor | Charles IV and I |

| Born | c. 1293 |

| Peasant revolt in Flanders 1323–1328 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1410 miniature of the Battle of Cassel | |||||||

| |||||||

The Flemish peasant revolt of 1323–1328, sometimes referred to as the Flemish coast uprising (Dutch: Opstand van Kust-Vlaanderen, French: soulèvement de la Flandre maritime) in historical writing, was a popular revolt in late medieval Europe. Beginning as a series of scattered rural riots in late 1323, peasant insurrection escalated into a full-scale rebellion that dominated public affairs in Flanders for nearly five years until 1328. The uprising in Flanders was caused by both excessive taxations levied by the Count of Flanders Louis I, and by his pro-French policies. The insurrection had urban leaders and rural factions which took over most of Flanders by 1325.

The revolt was led by Nicolaas Zannekin, a rich farmer from Lampernisse. Zannekin and his men captured the towns of Nieuwpoort, Veurne, Ypres and Kortrijk. In Kortrijk, Zannekin was able to capture the count himself. In 1325, attempts to capture Gent and Oudenaarde failed. The King of France, Charles IV intervened, whereupon Louis was released from captivity in February 1326 and the Peace of Arques was sealed. The peace soon failed, and the count fled to France when more hostilities erupted. Louis convinced his new liege Philip VI of France to come to his aid, and Zannekin and his adherents were decisively defeated by the French royal army in the Battle of Cassel.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1323–1328_Flemish_revolt

Geraardsbergen (Dutch pronunciation: [ˈɣeːraːrdzbɛrɣə(n)], French: Grammont) is a city and municipality located in the Denderstreek and in the Flemish Ardennes, the hilly southern part of the Belgian province of East Flanders. The municipality comprises the city of Geraardsbergen proper and the following towns:

- Goeferdinge, Grimminge, Idegem, Moerbeke, Geraardsbergen, Nederboelare, Nieuwenhove, Onkerzele, Ophasselt, Overboelare, Schendelbeke, Smeerebbe-Vloerzegem, Viane, Waarbeke, Zandbergen and Zarlardinge.

On January 1, 2006 Geraardsbergen had a total population of 31,380. The total area is 79.71 km² which gives a population density of 394 inhabitants per km².

The current mayor of Geraardsbergen is Guido De Padt, from the (liberal) party Open VLD.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Geraardsbergen

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moors

The child mortality rate was very high in medieval Europe and John may have died from any number of causes, but rumours of poisoning spread immediately after his death (including one which said that he had been murdered with a pin by his aunt),[2] as many people benefited from it, and as John's father also died in strange circumstances. The cause of his death is still not known today.[3]

The premature death of John brought the first issue of succession of the Capetian dynasty. When Louis X, his father, died without a son to succeed him, it was the first time since Hugh Capet that the succession from father to son of the kings of France was interrupted. It was then decided to wait until his pregnant widow, Clementia of Hungary, delivered the child. The king's brother, Philip the Tall, was in charge of the regency of the kingdom against his uncle Charles of Valois. The birth of a male child was expected to give France its king. The problem of succession returned when John died five days after birth. Philip ascended the throne at the expense of John's four-year-old half-sister, Joan, daughter of Louis X and Margaret of Burgundy.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_I_of_France

The Robertians (sometimes called the Robertines in modern scholarship) are the proposed Frankish family which was ancestral to the Capetian dynasty, and thus to the royal families of France and of many other countries.[citation needed] The Capetians appear first in the records as powerful nobles serving under the Carolingian dynasty in West Francia, which later became France. As their power increased, they came into conflict with the older royal family and attained the crown several times before the eventual start of the continuous rule of the descendants of Hugh Capet (ruled 987–996).

Hugh's paternal ancestral family, the Robertians, appear in documents that can trace them back to his great-grandfather Robert the Strong (d. 866). His origins remain unclear, but medieval records hint at an origin in East Francia, in present-day Germany, an area then still also ruled by the Carolingians. In particular, Regino of Prüm (died 915 CE) states that Robert the Strong's son Odo was said to be a relative (nepos) of a Count Meingaud, count of an area near Worms, who died in 892, and there are indications that Maingaud's family used the names Robert and Odo.

Modern proposals about their ancestry further back are based on the idea that there was one family which frequently named its sons Robert, including Robert III of Worms (800–834), Robert the Strong (d. 866), and Robert I of France (866–923). For example, one proposed ancestor is Robert of Hesbaye (c. 800), about whom there are almost no records.

The Robertian family figured prominently amongst the Carolingian nobility and married into this royal family. Eventually, the Robertians themselves produced Frankish kings such as the brothers Odo (reigned 888–898) and Robert I (r. 922–923), then Hugh Capet (r. 987–996), who ruled from his seat in Paris as the first Capetian king of France.

Although Philip II Augustus (r. 1180–1223) was officially the last monarch of France with the title "King of the Franks" (rex Francorum) and the first to style himself "King of France" (roi de France), in (systematic application of) historiography, Hugh Capet holds this distinction. He founded the Capetians, the royal dynasty that ruled France until the revolution of the Second French Republic in 1848—save during the interregnum of the French Revolution and Napoleonic Wars. Members of the family still reign in Europe today; both King Felipe VI of Spain and Grand Duke Henri of Luxembourg descend from this family through the Bourbon cadet branch of the dynasty.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robertians

Philip II (21 August 1165 – 14 July 1223), byname Philip Augustus (French: Philippe Auguste), was King of France from 1180 to 1223. His predecessors had been known as kings of the Franks, but from 1190 onward, Philip became the first French monarch to style himself "King of France" (Latin: rex Francie).[1][2][3] The son of King Louis VII and his third wife, Adela of Champagne, he was originally nicknamed Dieudonné (God-given) because he was a first son and born late in his father's life. Philip was given the epithet "Augustus" by the chronicler Rigord for having extended the crown lands of Franceso remarkably.

After decades of conflicts with the House of Plantagenet, Philip succeeded in putting an end to the Angevin Empire by defeating a coalition of his rivals at the Battle of Bouvines in 1214.[4] This victory would have a lasting impact on western European politics: the authority of the French king became unchallenged, while the English King John was forced by his barons to assent to Magna Carta and deal with a rebellion against him aided by Philip's son Louis, the First Barons' War. The military actions surrounding the Albigensian Crusade helped prepare the expansion of France southward. Philip did not participate directly in these actions, but he allowed his vassals and knights to help carry them out.

Philip transformed France into the most prosperous and powerful country in Europe.[5] He checked the power of the nobles and helped the towns free themselves from seigneurial authority, granting privileges and liberties to the emergent bourgeoisie. He built a great wall around Paris ("the Wall of Philip II Augustus"), re-organized the French government and brought financial stability to his country.

| Philip II | |

|---|---|

Seal of Philip II | |

| King of France (more...) | |

| Reign | 1190 – 14 July 1223 |

| Successor | Louis VIII |

The House of Plantagenet[nb 1] (/plænˈtædʒənɪt/) was a royal house which originated from the lands of Anjou in France. The family held the English throne from 1154 (with the accession of Henry II, at the end of The Anarchy crisis) to 1485, when Richard III died in battle.

Under the Plantagenets, England was transformed. The Plantagenet kings were often forced to negotiate compromises such as the Magna Carta, which had served to constrain their royal power in return for financial and military support. The king was no longer considered an absolute monarch in the nation—holding the prerogatives of judgement, feudal tribute, and warfare—but now also had defined duties to the kingdom, underpinned by a sophisticated justice system. A distinct national identity was shaped by their conflict with the French, Scots, Welsh and Irish, and the establishment of the English language as the primary language.

In the 15th century, the Plantagenets were defeated in the Hundred Years' War and beset with social, political and economic problems. Popular revolts were commonplace, triggered by the denial of numerous freedoms. English nobles raised private armies, engaged in private feuds and openly defied Henry VI.

The rivalry between the House of Plantagenet's two cadet branches of York and Lancaster brought about the Wars of the Roses, a decades-long fight for the English succession, culminating in the Battle of Bosworth Field in 1485, when the reign of the Plantagenets and the English Middle Ages both met their end with the death of King Richard III. Henry VII, of Lancastrian descent, became king of England; five months later, he married Elizabeth of York, thus ending the Wars of the Roses, and giving rise to the Tudor dynasty. The Tudors worked to centralise English royal power, which allowed them to avoid some of the problems that had plagued the last Plantagenet rulers. The resulting stability allowed for the English Renaissance, and the advent of early modern Britain.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/House_of_Plantagenet

Richard III (2 October 1452 – 22 August 1485) was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 26 June 1483 until his death in 1485. He was the last king of the House of York and the last of the Plantagenet dynasty. His defeat and death at the Battle of Bosworth Field, the last decisive battle of the Wars of the Roses, marked the end of the Middle Ages in England. He is the protagonist of Richard III, one of William Shakespeare's history plays.