| Part of a series on |

| Anthropology of religion |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Social and cultural anthropology |

| Part of a series on the |

| Paranormal |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Supernatural refers to phenomena or entities that are beyond the laws of nature.[1] The term is derived from Medieval Latin supernaturalis, from Latin super- (above, beyond, or outside of) + natura (nature)[1] Though the corollary term "nature", has had multiple meanings since the ancient world, the term "supernatural" emerged in the Middle Ages[2] and did not exist in the ancient world.[3]

The supernatural is featured in folklore and religious contexts,[4] but can also feature as an explanation in more secular contexts, as in the cases of superstitions or belief in the paranormal.[5] The term is attributed to non-physical entities, such as angels, demons, gods, and spirits. It also includes claimed abilities embodied in or provided by such beings, including magic, telekinesis, levitation, precognition, and extrasensory perception.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Supernatural

| Part of a series on the |

| Paranormal |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Magic, sometimes spelled magick,[1] is an ancient practice rooted in rituals, spiritual divinations, and/or cultural lineage—with an intention to invoke, manipulate, or otherwise manifest supernatural forces, beings, or entities in the natural world.[2] It is a categorical yet often ambiguous term which has been used to refer to a wide variety of beliefs and practices, frequently considered separate from both religion and science.[3]

Although connotations have varied from positive to negative at times throughout history,[4] magic continues to have an important religious and medicinal role in many cultures today.[citation needed]

Within Western culture, magic has been linked to ideas of the Other,[5] foreignness,[6] and primitivism;[7] indicating that it is "a powerful marker of cultural difference"[8] and likewise, a non-modern phenomenon.[9] During the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, Western intellectuals perceived the practice of magic to be a sign of a primitive mentality and also commonly attributed it to marginalised groups of people.[8]

In modern occultism and neopagan religions, many self-described magicians and witches regularly practice ritual magic;[10] defining magic as a technique for bringing about change in the physical world through the force of one's will. This definition was popularised by Aleister Crowley (1875–1947), an influential British occultist, and since that time other religions (e.g. Wicca and LaVeyan Satanism) and magical systems (e.g. chaos magick) have adopted it.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Magic_(supernatural)

| Part of a series on the |

| Paranormal |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Paranormal events are purported phenomena described in popular culture, folk, and other non-scientific bodies of knowledge, whose existence within these contexts is described as being beyond the scope of normal scientific understanding.[1][2][3][4] Notable paranormal beliefs include those that pertain to extrasensory perception (for example, telepathy), spiritualism and the pseudosciences of ghost hunting, cryptozoology, and ufology.[5]

Proposals regarding the paranormal are different from scientific hypotheses or speculations extrapolated from scientific evidence because scientific ideas are grounded in empirical observations and experimental data gained through the scientific method. In contrast, those who argue for the existence of the paranormal explicitly do not base their arguments on empirical evidence but rather on anecdote, testimony, and suspicion. The standard scientific models give the explanation that what appears to be paranormal phenomena is usually a misinterpretation, misunderstanding, or anomalous variation of natural phenomena.[6][7][8]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paranormal

| Part of a series on the |

| Paranormal |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Magic_(supernatural)

| Part of a series on the |

| Paranormal |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Magic_(supernatural)

This concept remained pervasive throughout the Middle Ages, when Christian authors categorised a diverse range of practices—such as enchantment, witchcraft, incantations, divination, necromancy, and astrology—under the label "magic". In early modern Europe, Protestants often claimed that Roman Catholicism was magic rather than religion, and as Christian Europeans began colonizing other parts of the world in the sixteenth century, they labelled the non-Christian beliefs they encountered as magical.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Magic_(supernatural)

In that same period, Italian humanists reinterpreted the term in a positive sense to express the idea of natural magic. Both negative and positive understandings of the term recurred in Western culture over the following centuries.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Magic_(supernatural)

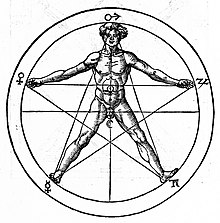

Natural magic in the context of Renaissance magic is that part of the occult which deals with natural forces directly, as opposed to ceremonial magic which deals with the summoning of spirits.[1] Natural magic sometimes makes use of physical substances from the natural world such as stones or herbs.[1]

Natural magic so defined includes astrology, alchemy, and disciplines that we would today consider fields of natural science, such as astronomy and chemistry (which developed and diverged from astrology and alchemy, respectively, into the modern sciences they are today) or botany (from herbology). The Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher wrote that "there are as many types of natural magic as there are subjects of applied sciences".[2]

Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa discusses natural magic in his Three Books of Occult Philosophy (1533),[1][3] where he calls it "nothing else but the highest power of natural sciences".[1] The Italian Renaissance philosopher Giovanni Pico della Mirandola, who founded the tradition of Christian Kabbalah, argued that natural magic was "the practical part of natural science" and was lawful rather than heretical.[4]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Natural_magic

See also

- Giambattista della Porta – Italian polymath (1535–1615)

- Magia Naturalis – Book by Giambattista della Porta

- Protoscience – Any pre-scientific or emerging practice of inquiry

- Thomas Vaughan – Welsh philosopher writing in English, 1621–1666

- White magic – Magic used for selfless purposes

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Natural_magic

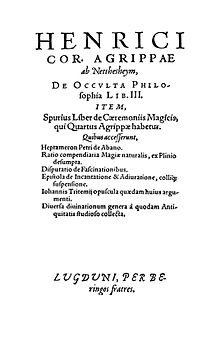

Three Books of Occult Philosophy (De Occulta Philosophia libri III) is Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa's study of occult philosophy, acknowledged as a significant contribution to the Renaissance philosophical discussion concerning the powers of magic, and its relationship with religion. The first book was printed in 1531 in Paris, Cologne, and Antwerp, while the full three volumes first appeared in Cologne in 1533.[1]

The three books deal with elemental, celestial and intellectual magic. The books outline the four elements, astrology, Kabbalah, numerology, angels, names of God, the virtues and relationships with each other as well as methods of utilizing these relationships and laws in medicine, scrying, alchemy, ceremonial magic, origins of what are from the Hebrew, Greek and Chaldean context.

These arguments were common amongst other hermetic philosophers at the time and before. In fact, Agrippa's interpretation of magic is similar to the authors Marsilio Ficino, Pico della Mirandola and Johann Reuchlin's synthesis of magic and religion, and emphasize an exploration of nature.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Three_Books_of_Occult_Philosophy

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:History_of_science

Media in category "History of science"

The following 2 files are in this category, out of 2 total.

- A history of the theories of aether and electricity. Whittacker E.T. (1910).pdf 747 × 1,210, 502 pages; 30.87 MB

- Toruń of 1192 before first Teutonic Knights in 1231.jpg 1,167 × 829; 1.22 MBhttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:History_of_science

Neurotree is a web-based database for the academic genealogy of neuroscientists. It was established in 2005. Later in 2005 Academic Family Tree began, incorporating Neurotree and academic genealogies of other scholarly disciplines.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neurotree

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/unclassifiable

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/restricted

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/unknown_uncertain

The doctrine of signatures, dating from the time of Dioscorides and Galen, states that herbs resembling various parts of the body can be used by herbalists to treat ailments of those body parts. A theological justification, as stated by botanists such as William Coles, was that God would have wanted to show men what plants would be useful for.

It is today considered to be pseudoscience,[1] and has led to many deaths and severe illnesses. For instance birthwort (so-called because of its resemblance to the uterus), once used widely for pregnancies, is carcinogenic and very damaging to the kidneys, owing to its aristolochic acid content.[2] As a defense against predation, many plants contain toxic chemicals, the action of which is not immediately apparent, or easily tied to the plant rather than other factors.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Doctrine_of_signatures

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/pharmacy

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/code

Universal science (German: Universalwissenschaft; Latin: scientia generalis, scientia universalis) is a branch of metaphysics.[1] In the work of Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, the universal science is the true logic.[2][3][4] Plato's system of idealism, formulated using the teachings of Socrates, is a predecessor to the concept of universal science.[citation needed] It emphasizes on the first principles which appear to be the reasoning behind everything, emerging and being in state with everything.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Universal_science

Below are discoveries in science that involve chance circumstances in a particularly salient way. This page should not list all chance involved in all discoveries (i.e. it should focus on discoveries reported for their notable circumstances).

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_discoveries_influenced_by_chance_circumstances

| Part of a series on |

| Human history Human Era |

|---|

| ↑ Prehistory (Pleistocene epoch) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ↓ Future |

The discovery of human antiquity was a major achievement of science in the middle of the 19th century, and the foundation of scientific paleoanthropology. The antiquity of man, human antiquity, or in simpler language the age of the human race, are names given to the series of scientific debates it involved, which with modifications continue in the 21st century. These debates have clarified and given scientific evidence, from a number of disciplines, towards solving the basic question of dating the first human being.

Controversy was very active in this area in parts of the 19th century, with some dormant periods also. A key date was the 1859 re-evaluation of archaeological evidence that had been published 12 years earlier by Boucher de Perthes. It was then widely accepted, as validating the suggestion that man was much older than had previously been believed, for example than the 6,000 years implied by some traditional chronologies.

In 1863 T. H. Huxley argued that man was an evolved species; and in 1864 Alfred Russel Wallace combined natural selection with the issue of antiquity. The arguments from science for what was then called the "great antiquity of man" became convincing to most scientists, over the following decade. The separate debate on the antiquity of man had in effect merged into the larger one on evolution, being simply a chronological aspect. It has not ended as a discussion, however, since the current science of human antiquity is still in flux.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Discovery_of_human_antiquity

Epistemic cultures (most of the times in plural form) are a concept developed in the nineties by anthropologist Karin Knorr Cetina in her book Epistemic Cultures, how the sciences make knowledge.[1] Opposed to a monist vision of scientific activity (according to which, would exist a unique scientific method), Knorr Cetina defines the concept of epistemic cultures as a diversity of scientific activities according to different scientific fields, not only in methods and tools, but also in types of reasonings, ways to establish evidence, and relationships between theory and empiry. Knorr Cetina's work is seminal in questioning the so-called unity of science.[citation needed]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Epistemic_cultures

Patterns in nature are visible regularities of form found in the natural world. These patterns recur in different contexts and can sometimes be modelled mathematically. Natural patterns include symmetries, trees, spirals, meanders, waves, foams, tessellations, cracks and stripes.[1] Early Greek philosophers studied pattern, with Plato, Pythagoras and Empedocles attempting to explain order in nature. The modern understanding of visible patterns developed gradually over time.

In the 19th century, the Belgian physicist Joseph Plateau examined soap films, leading him to formulate the concept of a minimal surface. The German biologist and artist Ernst Haeckel painted hundreds of marine organisms to emphasise their symmetry. Scottish biologist D'Arcy Thompson pioneered the study of growth patterns in both plants and animals, showing that simple equations could explain spiral growth. In the 20th century, the British mathematician Alan Turing predicted mechanisms of morphogenesis which give rise to patterns of spots and stripes. The Hungarian biologist Aristid Lindenmayer and the French American mathematician Benoît Mandelbrot showed how the mathematics of fractals could create plant growth patterns.

Mathematics, physics and chemistry can explain patterns in nature at different levels and scales. Patterns in living things are explained by the biological processes of natural selection and sexual selection. Studies of pattern formation make use of computer models to simulate a wide range of patterns.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Patterns_in_nature

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Portal:History_of_science

When someone who has not shown a history of suicidal ideation experiences a sudden and pronounced thought of performing an act which would necessarily lead to their own death, psychologists call this an intrusive thought. A commonly experienced example of this is the high place phenomenon,[14] also referred to as the call of the void.[15]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Suicidal_ideation

See also

- Existential angst

- Existential crisis

- Existential nihilism

- Finno-Ugrian suicide hypothesis

- Mental health first aid

- Suicide attempt

- Suicide crisis

- Wellness check

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Suicidal_ideation

| Nightmare disorder | |

|---|---|

| |

| The Nightmare, by Johann Heinrich Füssli | |

| Specialty | Psychiatry |

| Frequency | c. 4%[1] |

Nightmare disorder is a sleep disorder characterized by repeated intense nightmares that most often center on threats to physical safety and security.[2] The nightmares usually occur during the REM stage of sleep, and the person who experiences the nightmares typically remembers them well upon waking.[2] More specifically, nightmare disorder is a type of parasomnia, a subset of sleep disorders categorized by abnormal movement or behavior or verbal actions during sleep or shortly before or after. Other parasomnias include sleepwalking, sleep terrors, bedwetting, and sleep paralysis.[3]

Nightmare disorders can be confused with sleep terror disorders.[4] The difference is that after a sleep terror episode, the patient wakes up with more dramatic symptoms than with a nightmare disorder, such as screaming and crying.[4] Furthermore, they don't remember the reason of the fear, while a patient with a nightmare disorder remembers every detail of the dream.[4] Finally, the sleep terrors usually occur during NREM Sleep.[5][6]

Nightmares also have to be distinguished from bad dreams, which are less emotionally intense.[7] Furthermore, nightmares contain more scenes of aggression than bad dreams and more unhappy endings.[7] Finally, people experiencing nightmares feel more fear than with bad dreams.[7]

The treatment depends on whether or not there is a comorbid PTSD diagnosis.[1] About 4% of American adults are affected.[1] Studies examining nightmare disorders have found that the prevalence rates range from 2-6% with the prevalence being similar in the USA, Canada, France, Iceland, Sweden, Belgium, Finland, Austria, Japan, and the Middle East.[8]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nightmare_disorder

| Body dysmorphic disorder | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Body dysmorphia Dysmorphic syndrome Dysmorphophobia, dysmorphia |

| Specialty | Psychiatry, clinical psychology |

Body dysmorphic disorder (BDD), occasionally still called dysmorphia,[1] is a mental disorder characterized by the obsessive idea that some aspect of one's own body part or appearance is severely flawed and therefore warrants exceptional measures to hide or fix it.[2] In BDD's delusional variant, the flaw is imagined.[3] If the flaw is actual, its importance is severely exaggerated.[3] Either way, thoughts about it are pervasive and intrusive, and may occupy several hours a day, causing severe distress and impairing one's otherwise normal activities. BDD is classified as a somatoform disorder, and the DSM-5 categorizes BDD in the obsessive–compulsive spectrum, and distinguishes it from anorexia nervosa.

BDD is estimated to affect from 0.7% to 2.4% of the population.[3] It usually starts during adolescence and affects both men and women.[3][4] The BDD subtype muscle dysmorphia, perceiving the body as too small, affects mostly males.[5] Besides thinking about it, one repetitively checks and compares the perceived flaw, and can adopt unusual routines to avoid social contact that exposes it.[3] Fearing the stigma of vanity, one usually hides the preoccupation.[3] Commonly unsuspected even by psychiatrists, BDD has been underdiagnosed.[3] Severely impairing quality of life via educational and occupational dysfunction and social isolation, BDD has high rates of suicidal thoughts and attempts at suicide.[3]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Body_dysmorphic_disorder

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/deformity

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/beauty-youth-fertility

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/aesthetic

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/anorexia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/dire-need

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/grade

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/reconstructive-surgery

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/short-fat-ugly-freckles-etc.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Substance_use_disorder

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tobacco

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Diet_Carbonated_Drink

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Seltzer-water

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Limitations

Foundation: The International Review of Science Fiction is a critical peer-reviewed literary journal established in 1972 that publishes articles and reviews about science fiction. It is published triannually (spring, summer, and winter) by the Science Fiction Foundation. The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction has called it "perhaps the liveliest and indeed the most critical of the big three critical journals"[1] (the others being Extrapolation and Science Fiction Studies). A long-running feature was the series of interviews and autobiographical pieces with leading writers, entitled "The Profession of Science Fiction", a selection of which was edited and published by Macmillan Publishers in 1992. Several issues have been themed, including #93 (A Celebration of British Science Fiction, 2005), also published as part of the Foundation Studies in Science Fiction. The hundredth edition (Summer 2007) was unusual in that it was an all-fiction issue, including stories by such writers as Vandana Singh, Tricia Sullivan, Karen Traviss, Jon Courtenay Grimwood, John Kessel, Nalo Hopkinson, Greg Egan, and Una McCormack.[2] Back issues of the journal are archived at the University of Liverpool's SF Hub[3] whilst more recent issues can be found electronically via the database providers ProQuest.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Foundation_(journal)

Sudden unintended acceleration (SUA) is the unintended, unexpected, uncontrolled acceleration of a vehicle, often accompanied by an apparent loss of braking effectiveness.[1] Such problems may be caused by driver error (e.g., pedal misapplication), mechanical or electrical problems, or some combination of these factors.[2] The US National Highway Traffic Safety Administration estimates 16,000 accidents per year in the United States occur when drivers intend to apply the brake but mistakenly apply the accelerator.[3]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sudden_unintended_acceleration

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/National_Highway_Traffic_Safety_Administration

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Automotive_safety

A microdot is text or an image substantially reduced in size to prevent detection by unintended recipients. Microdots are normally circular and around 1 millimetre (0.039 in) in diameter but can be made into different shapes and sizes and made from various materials such as polyester or metal. The name comes from the fact that the microdots have often been about the size and shape of a typographical dot, such as a period or the tittle of a lowercase i or j. Microdots are, fundamentally, a steganographic approach to message protection.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Microdot

Terra firma ("solid earth" in Latin) may refer to:

- Solid earth, the planet's solid surface and its interior

- Terra firma forest, moist tropical forest that does not get seasonally flooded

- Terrafirma, the mainland territories of the Republic of Venice

- Terra Firma (Farscape episode)

- Terra Firma Capital Partners, a private equity firm

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Terra_firma

Juan de Fuca | |

|---|---|

Bust of Juan de Fuca, created by Cephalonian sculptor Spiros Hourmouzis | |

| Born | Ioannis Fokas 10 June 1536 |

| Died | 23 July 1602 (aged 66) Cephalonia |

| Nationality | Greek |

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Juan_de_Fuca

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quai_Fran%C3%A7ois_Mitterrand

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tooth_fairy

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ration_stamp