Khazar Khaganate | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 650–969 | |||||||||||||||

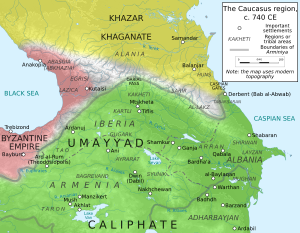

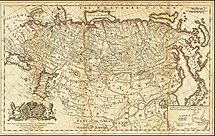

Khazar Khaganate, 650–850 | |||||||||||||||

| Status | Khaganate | ||||||||||||||

| Capital | |||||||||||||||

| Common languages | |||||||||||||||

| Religion | |||||||||||||||

| Qaghan | |||||||||||||||

• c. 650 | Irbis | ||||||||||||||

• 8th century | Bulan | ||||||||||||||

• 9th century | Obadiah | ||||||||||||||

• 9th century | Zachariah | ||||||||||||||

• 9th century | Manasseh | ||||||||||||||

• 9th century | Benjamin | ||||||||||||||

• 10th century | Aaron | ||||||||||||||

• 10th century | Joseph | ||||||||||||||

• 10th century | David | ||||||||||||||

• 11th century | Georgios | ||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | ||||||||||||||

• Established | c. 650 | ||||||||||||||

| 969 | |||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||

| 850 est.[4] | 3,000,000 km2 (1,200,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||

| 900 est.[5] | 1,000,000 km2 (390,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||

| Currency | Yarmaq | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| History of the Turkic peoples pre–14th century |

|---|

|

|

|

|

| History of Tatarstan |

|---|

|

The Khazars[a] (/ˈxɑːzɑːrz/) were a semi-nomadic Turkic people that in the late 6th-century CE established a major commercial empire covering the southeastern section of modern European Russia, southern Ukraine, Crimea, and Kazakhstan.[10] They created what for its duration was the most powerful polity to emerge from the break-up of the Western Turkic Khaganate.[11] Astride a major artery of commerce between Eastern Europe and Southwestern Asia, Khazaria became one of the foremost trading empires of the early medieval world, commanding the western marches of the Silk Road and playing a key commercial role as a crossroad between China, the Middle East and Kievan Rus'.[12][13] For some three centuries (c. 650–965) the Khazars dominated the vast area extending from the Volga-Don steppes to the eastern Crimea and the northern Caucasus.[14]

Khazaria long served as a buffer state between the Byzantine Empire and both the nomads of the northern steppes and the Umayyad Caliphate and Abbasid Caliphate, after serving as the Byzantine Empire's proxy against the Sasanian Empire. The alliance was dropped around 900. Byzantium began to encourage the Alans to attack Khazaria and to weaken its hold on Crimea and the Caucasus and sought to obtain an entente with the rising Rus' power to the north, which it aspired to convert to Christianity.[15] Between 965 and 969, the Kievan Rus' ruler, Sviatoslav I of Kiev, as well as his allies, conquered the capital, Atil, and ended Khazaria's independence. The state became the autonomous entity of Rus' and then of Khazar former provinces (Khwarazm in which Khazars were known as Turks, just as Hungarians were known as Turks in Byzantium) in Volga Bulgaria.

Determining the origins and nature of the Khazars is closely bound with theories of their languages, but it is a matter of intricate difficulty since no indigenous records in the Khazar language survive, and the state was polyglot and polyethnic. The native religion of the Khazars is thought to have been Tengrism, like that of the North Caucasian Huns and other Turkic peoples.[16] The polyethnic populace of the Khazar Khaganate appears to have been a multiconfessional mosaic of pagan, Tengrist, Jewish, Christian and Muslim worshippers.[17] Some of the Khazars (i.e., Kabars) joined the ancient Hungarians in the 9th century. The ruling elite of the Khazars was said by Judah Halevi and Abraham ibn Daud to have converted to Rabbinic Judaism in the 8th century,[18] but the scope of the conversion to Judaism within the Khazar Khanate remains uncertain.[19]

Where the Khazars dispersed after the fall of the Empire is subject to many conjectures. Proposals have been made regarding the possibility of a Khazar factor in the ethnogenesis of numerous peoples, such as the Hazaras, Hungarians, the Kazakhs, the Cossacks of the Don region and of Ukraine, Bukharan Jews, the Muslim Kumyks, the Turkic-speaking Krymchaks and their Crimean neighbours the Crimean Karaites, the Moldavian Csángós, the Mountain Jews, even some Subbotniks (on the basis of their Ukrainian and Cossack origin and others).[20][21][22] The late 19th century saw the emergence of the theory that the core of today's Ashkenazi Jews are descended from a hypothetical Khazarian Jewish diaspora which migrated westward from modern-day Russia and Ukraine into modern-day France and Germany. Linguistic and genetic studies have not supported the theory of a Khazar connection to Ashkenazi Jewry. The theory still finds occasional support, but most scholars view it with considerable scepticism.[23][19] The theory is sometimes associated with antisemitism[24] and anti-Zionism.[25]

Etymology

Gyula Németh, following Zoltán Gombocz, derived Khazar from a hypothetical *Qasar reflecting a Turkic root qaz- ("to ramble, to roam") being an hypothetical retracted variant of Common Turkic kez-;[26] however, András Róna-Tas objected that *qaz- is a ghost word.[27] In the fragmentary Tes and Terkhin inscriptions of the Uyğur empire (744–840) the form Qasar is attested, although uncertainty remains whether this represents a personal or tribal name, gradually other hypotheses emerged. Louis Bazin derived it from Turkic qas- ("tyrannize, oppress, terrorize") on the basis of its phonetic similarity to the Uyğur tribal name, Qasar.[note 3] Róna-Tas connects qasar with Kesar, the Pahlavi transcription of the Roman title Caesar.[note 4]

D. M. Dunlop tried to link the Chinese term for "Khazars" to one of the tribal names of the Uyğur, or Toquz Oğuz, namely the Qasar (Ch. 葛薩 Gésà).[28][29] The objections are that Uyğur 葛薩 Gésà/Qasar was not a tribal name but rather the surname of the chief of the 思结 Sijie tribe (Sogdian: Sikari) of the Toquz Oğuz (Ch. 九姓 jĭu xìng),[note 5] and that in Middle Chinese the ethnonym "Khazars" was always prefaced with Tūjué, then still reserved for Göktürks and their splinter groups,[40] (Tūjué Kěsà bù:突厥可薩部; Tūjué Hésà:突厥曷薩) and "Khazar"'s first syllable is transcribed with different characters (可 and 曷) than 葛, which is used to render the syllable Qa- in the Uyğur word Qasar.[note 6][42][43]

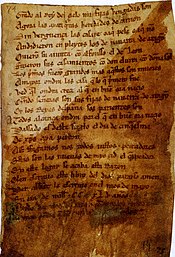

After their conversion it is reported that they adopted the Hebrew script,[note 7] and it is likely that, although speaking a Turkic language, the Khazar chancellery under Judaism probably corresponded in Hebrew.[note 8]

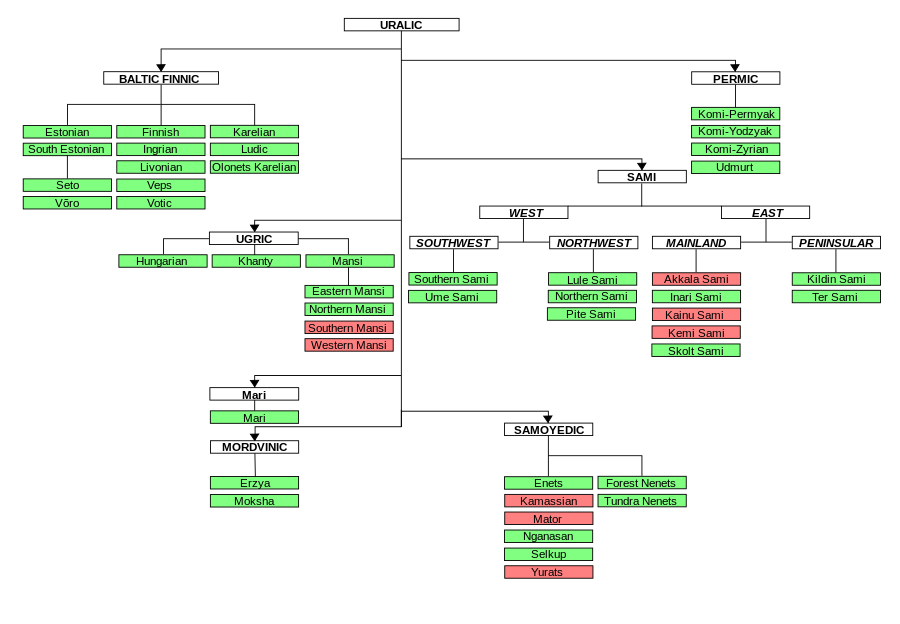

Linguistics

Determining the origins and nature of the Khazars is closely bound with theories of their languages, but it is a matter of intricate difficulty since no indigenous records in the Khazar language survive, and the state was polyglot and polyethnic.[note 9][note 10] Whereas the royal or ruling elite probably spoke an eastern variety of Shaz Turkic, the subject tribes appear to have spoken varieties of Lir Turkic, such as Oğuric, a language variously identified with Bulğaric, Chuvash, and Hunnish (the latter based upon the assertion of the Persian historian al-Iṣṭakhrī that the Khazar language was different from any other known tongue.[note 11][note 12] One method for tracing their origins consists in the analysis of the possible etymologies behind the ethnonym "Khazar".

History

Tribal origins and early history

The tribes[note 13] that were to comprise the Khazar empire were not an ethnic union, but a congeries of steppe nomads and peoples who came to be subordinated, and subscribed to a core Turkic leadership.[44] Many Turkic groups, such as the Oğuric peoples, including Šarağurs, Oğurs, Onoğurs, and Bulğars who earlier formed part of the Tiele (Tiělè) confederation, are attested quite early, having been driven West by the Sabirs, who in turn fled the Asian Avars, and began to flow into the Volga-Caspian-Pontic zone from as early as the 4th century CE and are recorded by Priscus to reside in the Western Eurasian steppe lands as early as 463.[45][46] They appear to stem from Mongolia and South Siberia in the aftermath of the fall of the Hunnic/Xiōngnú nomadic polities. A variegated tribal federation led by these Turks, probably comprising a complex assortment of Iranian,[note 14] proto-Mongolic, Uralic, and Palaeo-Siberian clans, vanquished the Rouran Khaganate of the hegemonic central Asian Avars in 552 and swept westwards, taking in their train other steppe nomads and peoples from Sogdiana.[47]

The ruling family of this confederation may have hailed from the Āshǐnà (阿史那) clan of the Western Turkic Khaganate,[48][49][50] although Constantine Zuckerman regards Ashina and their pivotal role in the formation of the Khazars with scepticism.[note 15] Golden notes that Chinese and Arabic reports are almost identical, making the connection a strong one, and conjectures that their leader may have been Yǐpíshèkuì (Chinese:乙毗射匱), who lost power or was killed around 651.[51] Moving west, the confederation reached the land of the Akatziroi,[note 16] who had been important allies of Byzantium in fighting off Attila's army.

Rise of the Khazar state

An embryonic state of Khazaria began to form sometime after 630,[52][53] when it emerged from the breakdown of the larger Göktürk Khaganate. Göktürk armies had penetrated the Volga by 549, ejecting the Avars, who were then forced to flee to the sanctuary of the Hungarian plain. The Ashina clan appeared on the scene by 552, when they overthrew the Rourans and established the Göktürk Qağanate, whose self designation was Tür(ü)k.[note 17] By 568, these Göktürks were probing for an alliance with Byzantium to attack Persia. An internecine war broke out between the senior eastern Göktürks and the junior West Turkic Khaganate some decades later, when on the death of Taspar Qağan, a succession dispute led to a dynastic crisis between Taspar's chosen heir, the Apa Qağan, and the ruler appointed by the tribal high council, Āshǐnà Shètú (阿史那摄图), the Ishbara Qağan.

By the first decades of the 7th century, the Ashina yabgu Tong managed to stabilise the Western division, but upon his death, after providing crucial military assistance to Byzantium in routing the Sasanian army in the Persian heartland,[54][55] the Western Turkic Qağanate dissolved under pressure from the encroaching Tang dynasty armies and split into two competing federations, each consisting of five tribes, collectively known as the "Ten Arrows" (On Oq). Both briefly challenged Tang hegemony in eastern Turkestan. To the West, two new nomadic states arose in the meantime, Old Great Bulgaria under Kubrat, the Duōlù clan leader, and the Nǔshībì subconfederation, also consisting of five tribes.[note 18] The Duōlù challenged the Avars in the Kuban River-Sea of Azov area while the Khazar Qağanate consolidated further westwards, led apparently by an Ashina dynasty. With a resounding victory over the tribes in 657, engineered by General Sū Dìngfāng (蘇定方), Chinese overlordship was imposed to their East after a final mop-up operation in 659, but the two confederations of Bulğars and Khazars fought for supremacy on the western steppeland, and with the ascendency of the latter, the former either succumbed to Khazar rule or, as under Asparukh, Kubrat's son, shifted even further west across the Danube to lay the foundations of the First Bulgarian Empire in the Balkans (c. 679).[56][57]

The Qağanate of the Khazars thus took shape out of the ruins of this nomadic empire as it broke up under pressure from the Tang dynasty armies to the east sometime between 630 and 650.[51] After their conquest of the lower Volga region to the East and an area westwards between the Danube and the Dniepr, and their subjugation of the Onoğur-Bulğar union, sometime around 670, a properly constituted Khazar Qağanate emerges,[58] becoming the westernmost successor state of the formidable Göktürk Qağanate after its disintegration. According to Omeljan Pritsak, the language of the Onoğur-Bulğar federation was to become the lingua franca of Khazaria[59] as it developed into what Lev Gumilev called a "steppe Atlantis" (stepnaja Atlantida/ Степная Атлантида).[60] Historians have often referred to this period of Khazar domination as the Pax Khazarica since the state became an international trading hub permitting Western Eurasian merchants safe transit across it to pursue their business without interference.[61] The high status soon to be accorded this empire to the north is attested by Ibn al-Balḫî's Fârsnâma (c. 1100), which relates that the Sasanian Shah, Ḫusraw 1, Anûsîrvân, placed three thrones by his own, one for the King of China, a second for the King of Byzantium, and a third for the king of the Khazars. Although anachronistic in retrodating the Khazars to this period, the legend, in placing the Khazar qağan on a throne with equal status to kings of the other two superpowers, bears witness to the reputation won by the Khazars from early times.[62][63]

Khazar state: culture and institutions

Royal Diarchy with sacral Qağanate

Khazaria developed a Dual kingship governance structure,[note 19] typical among Turkic nomads, consisting of a shad/bäk and a qağan.[64] The emergence of this system may be deeply entwined with the conversion to Judaism.[65] According to Arabic sources, the lesser king was called îšâ and the greater king Khazar xâqân; the former managed and commanded the military, while the greater king's role was primarily sacral, less concerned with daily affairs. The greater king was recruited from the Khazar house of notables (ahl bait ma'rûfīn) and, in an initiation ritual, was nearly strangled until he declared the number of years he wished to reign, on the expiration of which he would be killed by the nobles.[note 20][66][67][note 21] The deputy ruler would enter the presence of the reclusive greater king only with great ceremony, approaching him barefoot to prostrate himself in the dust and then light a piece of wood as a purifying fire, while waiting humbly and calmly to be summoned.[68] Particularly elaborate rituals accompanied a royal burial. At one period, travellers had to dismount, bow before the ruler's tomb, and then walk away on foot.[69] Subsequently, the charismatic sovereign's burial place was hidden from view, with a palatial structure ("Paradise") constructed and then hidden under rerouted river water to avoid disturbance by evil spirits and later generations. Such a royal burial ground (qoruq) is typical of inner Asian peoples.[70] Both the îšâ and the xâqân converted to Judaism sometime in the 8th century, while the rest, according to the Persian traveller Ahmad ibn Rustah, probably followed the old Tūrkic religion.[71][note 22]

Ruling elite

The ruling stratum, like that of the later Činggisids within the Golden Horde, was a relatively small group that differed ethnically and linguistically from its subject peoples, meaning the Alano-As and Oğuric Turkic tribes, who were numerically superior within Khazaria.[72] The Khazar Qağans, while taking wives and concubines from the subject populations, were protected by a Khwârazmian guard corps, or comitatus, called the Ursiyya.[note 23][note 24] But unlike many other local polities, they hired soldiers (mercenaries) (the junûd murtazîqa in al-Mas'ûdî).[73] At the peak of their empire, the Khazars ran a centralised fiscal administration, with a standing army of some 7–12,000 men, which could, at need, be multiplied two or three times that number by inducting reserves from their nobles' retinues.[74][note 25] Other figures for the permanent standing army indicate that it numbered as many as one hundred thousand. They controlled and exacted tribute from 25 to 30 different nations and tribes inhabiting the vast territories between the Caucasus, the Aral Sea, the Ural Mountains, and the Ukrainian steppes.[75] Khazar armies were led by the Qağan Bek (pronounced as Kagan Bek) and commanded by subordinate officers known as tarkhans. When the bek sent out a body of troops, they would not retreat under any circumstances. If they were defeated, every one who returned was killed.[76]

Settlements were governed by administrative officials known as tuduns. In some cases, such as the Byzantine settlements in southern Crimea, a tudun would be appointed for a town nominally within another polity's sphere of influence. Other officials in the Khazar government included dignitaries referred to by ibn Fadlan as Jawyshyghr and Kündür, but their responsibilities are unknown.

Demographics

It has been estimated that 25 to 28 distinct ethnic groups made up the population of the Khazar Qağanate, aside from the ethnic elite. The ruling elite seems to have been constituted out of nine tribes/clans, themselves ethnically heterogeneous, spread over perhaps nine provinces or principalities, each of which would have been allocated to a clan.[66] In terms of caste or class, some evidence suggests that there was a distinction, whether racial or social is unclear, between "White Khazars" (ak-Khazars) and "Black Khazars" (qara-Khazars).[66] The 10th-century Muslim geographer al-Iṣṭakhrī claimed that the White Khazars were strikingly handsome with reddish hair, white skin, and blue eyes, while the Black Khazars were swarthy, verging on deep black as if they were "some kind of Indian".[77] Many Turkic nations had a similar (political, not racial) division between a "white" ruling warrior caste and a "black" class of commoners; the consensus among mainstream scholars is that Istakhri was confused by the names given to the two groups.[78] However, Khazars are generally described by early Arab sources as having a white complexion, blue eyes, and reddish hair.[79][80] The ethnonym in the Tang Chinese annals, Ashina, often accorded a key role in the Khazar leadership, may reflect an Eastern Iranian or Tokharian word (Khotanese Saka âşşeina-āššsena "blue"): Middle Persian axšaêna ("dark-coloured"): Tokharian A âśna ("blue", "dark").[6] The distinction appears to have survived the collapse of the Khazarian empire. Later Russian chronicles, commenting on the role of the Khazars in the magyarisation of Hungary, refer to them as "White Oghurs" and Magyars as "Black Oghurs".[81] Studies of the physical remains, such as skulls at Sarkel, have revealed a mixture of Slavic, other European, and a few Mongolian types.[78]

Economy

The import and export of foreign wares, and the revenues derived from taxing their transit, was a hallmark of the Khazar economy, although it is said also to have produced isinglass.[82] Distinctively among the nomadic steppe polities, the Khazar Qağanate developed a self-sufficient domestic Saltovo[83] economy, a combination of traditional pastoralism – allowing sheep and cattle to be exported – extensive agriculture, abundant use of the Volga's rich fishing stocks, together with craft manufacture, with diversification in lucrative returns from taxing international trade given its pivotal control of major trade routes.

The Khazars constituted one of the two great furnishers of slaves to the Muslim market (the other being the Iranian Sâmânid amîrs), supplying it with captured Slavs and tribesmen from the Eurasian northlands.[84] It profited from the latter which enabled it to maintain a standing army of Khwarezm Muslim troops. The capital Atil reflected the division: Kharazān on the western bank where the king and his Khazar elite, with a retinue of some 4,000 attendants, dwelt, and Itil proper to the East, inhabited by Jews, Christians, Muslims and slaves and by craftsmen and foreign merchants.[note 26]

The ruling elite wintered in the city and spent from spring to late autumn in their fields. A large irrigated greenbelt, drawing on channels from the Volga river, lay outside the capital, where meadows and vineyards extended for some 20 farsakhs (c. 60 miles).[85] While customs duties were imposed on traders, and tribute and tithes were exacted from 25 to 30 tribes, with a levy of one sable skin, squirrel pelt, sword, dirham per hearth or ploughshare, or hides, wax, honey and livestock, depending on the zone. Trade disputes were handled by a commercial tribunal in Atil consisting of seven judges, two for each of the monotheistic inhabitants (Jews, Muslims, Christians) and one for the pagans.[note 27]

Khazars and Byzantium

Byzantine diplomatic policy towards the steppe peoples generally consisted of encouraging them to fight among themselves. The Pechenegs provided great assistance to the Byzantines in the 9th century in exchange for regular payments.[86] Byzantium also sought alliances with the Göktürks against common enemies: in the early 7th century, one such alliance was brokered with the Western Tűrks against the Persian Sasanians in the Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628. The Byzantines called Khazaria Tourkía, and by the 9th century referred to the Khazars as "Turks".[note 28] During the period leading up to and after the siege of Constantinople in 626, Heraclius sought help via emissaries, and eventually personally, from a Göktürk chieftain[note 29] of the Western Turkic Khaganate, Tong Yabghu Qağan, in Tiflis, plying him with gifts and the promise of marriage to his daughter, Epiphania.[89] Tong Yabghu responded by sending a large force to ravage the Persian empire, marking the start of the Third Perso-Turkic War.[90] A joint Byzantine-Tűrk operation breached the Caspian gates and sacked Derbent in 627. Together they then besieged Tiflis, where the Byzantines may have deployed an early variety of traction trebuchets (ἑλέπόλεις) to breach the walls. After the campaign, Tong Yabghu is reported, perhaps with some exaggeration, to have left some 40,000 troops behind with Heraclius.[91] Although occasionally identified with Khazars, the Göktürk identification is more probable since the Khazars only emerged from that group after the fragmentation of the former sometime after 630.[52][53] Some scholars argued that Sasanian Persia never recovered from the devastating defeat wrought by this invasion.[note 30]

Once the Khazars emerged as a power, the Byzantines also began to form alliances with them, dynastic and military. In 695, the last Heraclian emperor, Justinian II, nicknamed "the slit-nosed" (ὁ ῥινότμητος) after he was mutilated and deposed, was exiled to Cherson in the Crimea, where a Khazar governor (tudun) presided. He escaped into Khazar territory in 704 or 705 and was given asylum by qağan Busir Glavan (Ἰβουζῆρος Γλιαβάνος), who gave him his sister in marriage, perhaps in response to an offer by Justinian, who may have thought a dynastic marriage would seal by kinship a powerful tribal support for his attempts to regain the throne.[92] The Khazarian spouse thereupon changed her name to Theodora.[93] Busir was offered a bribe by the Byzantine usurper, Tiberius III, to kill Justinian. Warned by Theodora, Justinian escaped, murdering two Khazar officials in the process. He fled to Bulgaria, whose Khan Tervel helped him regain the throne. Upon his reinstalment, and despite Busir's treachery during his exile, he sent for Theodora; Busir complied, and she was crowned as Augusta, suggesting that both prized the alliance.[94][95]

Decades later, Leo III (ruled 717–741) made a similar alliance to co-ordinate strategy against a common enemy, the Muslim Arabs. He sent an embassy to the Khazar qağan Bihar and married his son, the future Constantine V (ruled 741–775), to Bihar's daughter, a princess referred to as Tzitzak, in 732. On converting to Christianity, she took the name Irene. Constantine and Irene had a son, the future Leo IV (775–780), who thereafter bore the sobriquet, "the Khazar".[96][97] Leo died in mysterious circumstances after his Athenian wife bore him a son, Constantine VI, who on his majority co-ruled with his mother, the dowager. He proved unpopular, and his death ended the dynastic link of the Khazars to the Byzantine throne.[98][96] By the 8th century, Khazars dominated the Crimea (650–c. 950), and even extended their influence into the Byzantine peninsula of Cherson until it was wrested back in the 10th century.[99] Khazar and Farghânian (Φάργανοι) mercenaries constituted part of the imperial Byzantine Hetaireia bodyguard after its formation in 840, a position that could openly be purchased by a payment of seven pounds of gold.[100][101]

Arab–Khazar wars

During the 7th and 8th centuries, the Khazars fought a series of wars against the Umayyad Caliphate and its Abbasid successor. The First Arab-Khazar War began during the first phase of Muslim expansion. By 640, Muslim forces had reached Armenia; in 642 they launched their first raid across the Caucasus under Abd ar-Rahman ibn Rabiah. In 652 Arab forces advanced on the Khazar capital, Balanjar, but were defeated, suffering heavy losses; according to Persian historians such as al-Tabari, both sides in the battle used catapults against the opposing troops. A number of Russian sources give the name of a Khazar khagan from this period as Irbis and describe him as a scion of the Göktürk royal house, the Ashina. Whether Irbis ever existed is open to debate, as is whether he can be identified with one of the many Göktürk rulers of the same name.

Due to the outbreak of the First Muslim Civil War and other priorities, the Arabs refrained from repeating an attack on the Khazars until the early 8th century.[102] The Khazars launched a few raids into Transcaucasian principalities under Muslim dominion, including a large-scale raid in 683–685 during the Second Muslim Civil War that rendered much booty and many prisoners.[103] There is evidence from the account of al-Tabari that the Khazars formed a united front with the remnants of the Göktürks in Transoxiana.

The Second Arab-Khazar War began with a series of raids across the Caucasus in the early 8th century. The Umayyads tightened their grip on Armenia in 705 after suppressing a large-scale rebellion. In 713 or 714, the Umayyad general Maslamah conquered Derbent and drove deeper into Khazar territory. The Khazars launched raids in response into Albania and Iranian Azerbaijan but were driven back by the Arabs under Hasan ibn al-Nu'man.[104] The conflict escalated in 722 with an invasion by 30,000 Khazars into Armenia inflicting a crushing defeat. Caliph Yazid II responded, sending 25,000 Arab troops north, swiftly driving the Khazars back across the Caucasus, recovering Derbent, and advancing on Balanjar. The Arabs broke through the Khazar defence and stormed the city; most of its inhabitants were killed or enslaved, but a few of them managed to flee north.[103] Despite their success, the Arabs had not yet defeated the Khazar army, and they retreated south of the Caucasus.

In 724, the Arab general al-Jarrah ibn Abdallah al-Hakami inflicted a crushing defeat on the Khazars in a long battle between the rivers Cyrus and Araxes, then moved on to capture Tiflis, bringing Caucasian Iberia under Muslim suzerainty. The Khazars struck back in 726, led by a prince named Barjik, launching a major invasion of Albania and Azerbaijan; by 729, the Arabs had lost control of northeastern Transcaucasia and were thrust again into the defensive. In 730, Barjik invaded Iranian Azerbaijan and defeated Arab forces at Ardabil, killing the general al-Djarrah al-Hakami and briefly occupying the town. Barjik was defeated and killed the next year at Mosul, where he directed Khazar forces from a throne mounted with al-Djarrah's severed head[citation needed]. In 737, Marwan Ibn Muhammad entered Khazar territory under the guise of seeking a truce. He then launched a surprise attack in which The Qaghan fled north and the Khazars surrendered.[105] The Arabs did not have enough resources to influence the affairs of Transcaucasia.[105] The Qağan was forced to accept terms involving his conversion to Islam, and subject himself to the rule of the Caliphate, but the accommodation was short-lived because a combination of internal instability among the Umayyads and Byzantine support undid the agreement within three years, and the Khazars re-asserted their independence.[106] The suggestion that the Khazars adopted Judaism as early as 740 is based on the idea that, in part, it was, a re-assertion of their independence from the rule of both regional powers, Byzantium and the Caliphate, while it also conformed to a general Eurasian trend to embrace a world religion.[note 31]

Whatever the impact of Marwan's campaigns was, warfare between the Khazars and the Arabs ceased for more than two decades after 737. Arab raids continued to occur until 741, but their control of the region was limited because maintaining a large garrison at Derbent further depleted their already overstretched army. A third Muslim civil war soon broke out, leading to the Abbasid Revolution and the fall of the Umayyad dynasty in 750.

In 758, the Abbasid Caliph al-Mansur attempted to strengthen diplomatic ties with the Khazars, ordering Yazid ibn Usayd al-Sulami, one of his nobles and the military governor of Armenia, to take a royal Khazar bride. Yazid married a daughter of Khazar Khagan Baghatur, but she died inexplicably, possibly during childbirth. Her attendants returned home, convinced that some members of another Arab faction had poisoned her, and her father was enraged. the Khazar general Ras Tarkhan invaded regions which were located south of the Caucasus in 762–764, devastating Albania, Armenia, and Iberia, and capturing Tiflis. Thereafter, relations between the Khazars and the Abbasids became increasingly cordial, because the foreign policies of the Abbasids were generally less expansionist than the foreign policies of the Umayyads, relations between the Khazars and the Abbasids were ultimately broken by a series of raids which occurred in 799, the raids occurred after another marriage alliance failed.

Khazars and Hungarians

Around 830, a rebellion broke out in the Khazar khaganate. As a result, three Kabar tribes[107] of the Khazars (probably the majority of ethnic Khazars) joined the Hungarians and moved through Levedia to what the Hungarians call the Etelköz, the territory between the Carpathians and the Dnieper River. The Hungarians faced their first attack by the Pechenegs around 854,[108] though other sources state that an attack by Pechenegs was the reason for their departure to Etelköz. The new neighbours of the Hungarians were the Varangians and the eastern Slavs. From 862 onwards, the Hungarians (already referred to as the Ungri) along with their allies, the Kabars, started a series of raids from the Etelköz into the Carpathian Basin, mostly against the Eastern Frankish Empire (Germany) and Great Moravia, but also against the Lower Pannonian principality and Bulgaria. Then they together ended up at the outer slopes of Carpathians, and settled there, where the majority of Khazars converted from Judaism to Christianity in the 10th to 13th centuries. There could be shamanists and Christians among these Khazars apart from Jews.[109][better source needed]

Rise of the Rus' and the collapse of the Khazarian state

By the 9th century, groups of Varangian Rus', developing a powerful warrior-merchant system, began probing south down the waterways controlled by the Khazars and their protectorate, the Volga Bulgarians, partially in pursuit of the Arab silver that flowed north for hoarding through the Khazarian-Volga Bulgarian trading zones,[note 32] partially to trade in furs and ironwork.[note 33] Northern mercantile fleets passing Atil were tithed, as they were at Byzantine Cherson.[110] Their presence may have prompted the formation of a Rus' state by convincing the Slavs, Merja and the Chud' to unite to protect common interests against Khazarian exactions of tribute. It is often argued that a Rus' Khaganate modelled on the Khazarian state had formed to the east and that the Varangian chieftain of the coalition appropriated the title of qağan (khagan) as early as the 830s: the title survived to denote the princes of Kievan Rus', whose capital, Kyiv, is often associated with a Khazarian foundation.[111][112][note 34][note 35] The construction of the Sarkel fortress, with technical assistance from Khazaria's Byzantine ally at the time, together with the minting of an autonomous Khazar coinage around the 830s, may have been a defensive measure against emerging threats from Varangians to the north and from the Magyars on the eastern steppe.[note 36][note 37] By 860, the Rus' had penetrated as far as Kyiv and, via the Dnieper, Constantinople.[116]

Alliances often shifted. Byzantium, threatened by Varangian Rus' raiders, would assist Khazaria, and Khazaria at times allowed the northerners to pass through their territory in exchange for a portion of the booty.[117] From the beginning of the 10th century, the Khazars found themselves fighting on multiple fronts as nomadic incursions were exacerbated by uprisings by former clients and invasions from former allies. The pax Khazarica was caught in a pincer movement between steppe Pechenegs and the strengthening of an emergent Rus' power to the north, both undermining Khazaria's tributary empire.[118] According to the Schechter Text, the Khazar ruler King Benjamin (ca.880–890) fought a battle against the allied forces of five lands whose moves were perhaps encouraged by Byzantium.[note 38] Although Benjamin was victorious, his son Aaron II faced another invasion, this time led by the Alans, whose leader had converted to Christianity and entered into an alliance with Byzantium, which, under Leo VI the Wise, encouraged them to fight against the Khazars.

By the 880s, Khazar control of the Middle Dnieper from Kyiv, where they collected tribute from Eastern Slavic tribes, began to wane as Oleg of Novgorod wrested control of the city from the Varangian warlords Askold and Dir, and embarked on what was to prove to be the foundation of a Rus' empire.[119] The Khazars had initially allowed the Rus' to use the trade route along the Volga River, and raid southwards. See Caspian expeditions of the Rus'. According to Al-Mas'udi, the qağan is said to have given his assent on the condition that the Rus' give him half of the booty.[117] In 913, however, two years after Byzantium concluded a peace treaty with the Rus' in 911, a Varangian foray, with Khazar connivance, through Arab lands led to a request to the Khazar throne by the Khwârazmian Islamic guard for permission to retaliate against the large Rus' contingent on its return. The purpose was to revenge the violence the Rus' razzias had inflicted on their fellow Muslim believers.[note 39] The Rus' force was thoroughly routed and massacred.[117] The Khazar rulers closed the passage down the Volga to the Rus', sparking a war. In the early 960s, Khazar ruler Joseph wrote to Hasdai ibn Shaprut about the deterioration of Khazar relations with the Rus': "I protect the mouth of the river (Itil-Volga) and prevent the Rus arriving in their ships from setting off by sea against the Ishmaelites and (equally) all (their) enemies from setting off by land to Bab."[note 40]

The Rus' warlords launched several wars against the Khazar Qağanate, and raided down to the Caspian sea. The Schechter Letter relates the story of a campaign against Khazaria by HLGW (recently identified as Oleg of Chernigov) around 941 in which Oleg was defeated by the Khazar general Pesakh.[120] The Khazar alliance with the Byzantine empire began to collapse in the early 10th century. Byzantine and Khazar forces may have clashed in the Crimea, and by the 940s emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus was speculating in De Administrando Imperio about ways in which the Khazars could be isolated and attacked. The Byzantines during the same period began to attempt alliances with the Pechenegs and the Rus', with varying degrees of success. A further factor undermining the Khazar Qağanate was a shift in Islamic routes at this time, as Muslims in Khwarazmia forged trade links with the recently converted Volga Bulgarian Muslims, a move which may have caused a drastic drop, perhaps up to 80%, in the revenue base of Khazaria, and consequently, a crisis in its ability to pay for its defence.[121]

Sviatoslav I finally succeeded in destroying Khazar imperial power in the 960s, in a circular sweep that overwhelmed Khazar fortresses like Sarkel and Tamatarkha, and reached as far as the Caucasian Kassogians/Circassians[note 42] and then back to Kyiv.[122] Sarkel fell in 965, with the capital city of Atil following, c. 968 or 969.

In the Russian chronicle, the vanquishing of the Khazar traditions is associated with Vladimir's conversion in 986.[123] According to the Primary Chronicle, in 986 Khazar Jews were present at Vladimir's disputation to decide on the prospective religion of the Kievan Rus'.[124] Whether these were Jews who had settled in Kyiv or emissaries from some Jewish Khazar remnant state is unclear. Conversion to one of the faiths of the people of Scripture was a precondition to any peace treaty with the Arabs, whose Bulgar envoys had arrived in Kyiv after 985.[125]

A visitor to Atil wrote soon after the sacking of the city that its vineyards and garden had been razed, that not a grape or raisin remained in the land, and not even alms for the poor were available.[126] An attempt to rebuild may have been undertaken, since Ibn Hawqal and al-Muqaddasi refer to it after that date, but by Al-Biruni's time (1048) it was in ruins.[note 43]

Aftermath: impact, decline and dispersion

Although Poliak argued that the Khazar kingdom did not wholly succumb to Sviatoslav's campaign, but lingered on until 1224, when the Mongols invaded Rus',[127][128] by most accounts, the Rus'-Oghuz campaigns left Khazaria devastated, with perhaps many Khazarian Jews in flight,[129] and leaving behind at best a minor rump state. It left little trace, except for some placenames,[note 44] and much of its population was undoubtedly absorbed in successor hordes.[130] Al-Muqaddasi, writing ca.985, mentions Khazar beyond the Caspian sea as a district of "woe and squalor", with honey, many sheep and Jews.[131] Kedrenos mentions a joint Rus'-Byzantine attack on Khazaria in 1016, which defeated its ruler Georgius Tzul. The name suggests Christian affiliations. The account concludes by saying, that after Tzul's defeat, the Khazar ruler of "upper Media", Senaccherib, had to sue for peace and submission.[132] In 1024 Mstislav of Chernigov (one of Vladimir's sons) marched against his brother Yaroslav with an army that included "Khazars and Kassogians" in a repulsed attempt to restore a kind of "Khazarian"-type dominion over Kyiv.[122] Ibn al-Athir's mention of a "raid of Faḍlūn the Kurd against the Khazars" in 1030 CE, in which 10,000 of his men were vanquished by the latter, has been taken as a reference to such a Khazar remnant, but Barthold identified this Faḍlūn as Faḍl ibn Muḥammad and the "Khazars" as either Georgians or Abkhazians.[133][134] A Kievian prince named Oleg, grandson of Jaroslav was reportedly kidnapped by "Khazars" in 1079 and shipped off to Constantinople, although most scholars believe that this is a reference to the Cumans-Kipchaks or other steppe peoples then dominant in the Pontic region. Upon his conquest of Tmutarakan in the 1080s Oleg Sviatoslavich, son of a prince of Chernigov, gave himself the title "Archon of Khazaria".[122] In 1083 Oleg is said to have exacted revenge on the Khazars after his brother Roman was killed by their allies, the Polovtsi/Cumans. After one more conflict with these Polovtsi in 1106, the Khazars fade from history.[132] By the 13th century they survived in Russian folklore only as "Jewish heroes" in the "land of the Jews". (zemlya Jidovskaya).[135]

By the end of the 12th century, Petachiah of Ratisbon reported travelling through what he called "Khazaria", and had little to remark on other than describing its minim (sectaries) living amidst desolation in perpetual mourning.[136] The reference seems to be to Karaites.[137] The Franciscan missionary William of Rubruck likewise found only impoverished pastures in the lower Volga area where Ital once lay.[85] Giovanni da Pian del Carpine, the papal legate to the court of the Mongol Khan Guyuk at that time, mentioned an otherwise unattested Jewish tribe, the Brutakhi, perhaps in the Volga region. Although connections are made to the Khazars, the link is based merely on a common attribution of Judaism.[138]

The 10th century Zoroastrian Dênkart registered the collapse of Khazar power in attributing its eclipse to the enfeebling effects of "false" religion.[note 45] The decline was contemporary to that suffered by the Transoxiana Sāmānid empire to the east, both events paving the way for the rise of the Great Seljuq Empire, whose founding traditions mention Khazar connections.[139][note 46] Whatever successor entity survived, it could no longer function as a bulwark against the pressure east and south of nomad expansions. By 1043, Kimeks and Qipchaqs, thrusting westwards, pressured the Oğuz, who in turn pushed the Pechenegs west towards Byzantium's Balkan provinces.[140]

Khazaria nonetheless left its mark on the rising states and some of their traditions and institutions. Much earlier, Tzitzak, the Khazar wife of Leo III, introduced into the Byzantine court the distinctive kaftan or riding habit of the nomadic Khazars, the tzitzakion (τζιτζάκιον), and this was adopted as a solemn element of imperial dress.[note 47] The orderly hierarchical system of succession by "scales" (lestvichnaia sistema:лествичная система) to the Grand Principate of Kyiv was arguably modelled on Khazar institutions, via the example of the Rus' Khaganate.[141]

The proto-Hungarian Pontic tribe, while perhaps threatening Khazaria as early as 839 (Sarkel), practiced their institutional model, such as the dual rule of a ceremonial kende-kündü and a gyula administering practical and military administration, as tributaries of the Khazars. A dissident group of Khazars, the Qabars, joined the Hungarians in their migration westwards as they moved into Pannonia. Elements within the Hungarian population can be viewed as perpetuating Khazar traditions as a successor state. Byzantine sources refer to Hungary as Western Tourkia in contrast to Khazaria, Eastern Tourkia. The gyula line produced the kings of medieval Hungary through descent from Árpád, while the Qabars retained their traditions longer, and were known as "black Hungarians" (fekete magyarság). Some archaeological evidence from Čelarevo suggests the Qabars practised Judaism[142][143][144] since warrior graves with Jewish symbols were found there, including menorahs, shofars, etrogs, lulavs, candlesnuffers, ash collectors, inscriptions in Hebrew, and a six-pointed star identical to the Star of David.[145][146]

The Khazar state was not the only Jewish state to rise between the fall of the Second Temple (67–70 CE) and the establishment of Israel (1948). A state in Yemen also adopted Judaism in the 4th century, lasting until the rise of Islam.[147]

The Khazar kingdom is said to have stimulated messianic aspirations for a return to Israel as early as Judah Halevi.[148] In the time of the Egyptian vizier Al-Afdal Shahanshah (d. 1121), one Solomon ben Duji, often identified as a Khazarian Jew,[note 49] attempted to advocate for a messianic effort for the liberation of, and return of all Jews to, Palestine. He wrote to many Jewish communities to enlist support. He eventually moved to Kurdistan where his son Menachem some decades later assumed the title of Messiah and, raising an army for this purpose, took the fortress of Amadiya north of Mosul. His project was opposed by the rabbinical authorities and he was poisoned in his sleep. One theory maintains that the Star of David, until then a decorative motif or magical emblem, began to assume its national value in late Jewish tradition from its earlier symbolic use by Menachem.[149]

The word Khazar, as an ethnonym, was last used in the 13th century by people in the North Caucasus believed to practice Judaism.[150] The nature of a hypothetical Khazar diaspora, Jewish or otherwise, is disputed. Avraham ibn Daud mentions encountering rabbinical students descended from Khazars as far away as Toledo, Spain in the 1160s.[151] Khazar communities persisted here and there. Many Khazar mercenaries served in the armies of the Islamic Caliphates and other states. Documents from medieval Constantinople attest to a Khazar community mingled with the Jews of the suburb of Pera.[152] Khazar merchants were active in both Constantinople and Alexandria in the 12th century.[153]

Religion

Tengrism

Direct sources for the Khazar religion are not many, but in all likelihood they originally engaged in a traditional Turkic form of religious practices known as Tengrism, which focused on the sky god Tengri. Something of its nature may be deduced from what we know of the rites and beliefs of contiguous tribes, such as the North Caucasian Huns. Horse sacrifices were made to this supreme deity. Rites involved offerings to fire, water, and the moon, to remarkable creatures, and to "gods of the road" (cf. Old Türk yol tengri, perhaps a god of fortune). Sun amulets were widespread as cultic ornaments. A tree cult was also maintained. Whatever was struck by lightning, man or object, was considered a sacrifice to the high god of heaven. The afterlife, to judge from excavations of aristocratic tumuli, was much a continuation of life on earth, warriors being interred with their weapons, horses, and sometimes with human sacrifices: the funeral of one tudrun in 711-12 saw 300 soldiers killed to accompany him to the otherworld. Ancestor worship was observed. The key religious figure appears to have been a shaman-like qam,[154] and it was these (qozmím) that were, according to the Khazar Hebrew conversion stories, driven out.

Many sources suggest, and a notable number of scholars have argued, that the charismatic Ashina clan played a germinal role in the early Khazar state, although Zuckerman dismisses the widespread notion of their pivotal role as a "phantom". The Ashina were closely associated with the Tengri cult, whose practices involved rites performed to assure a tribe of heaven's protective providence.[155] The qağan was deemed to rule by virtue of qut, "the heavenly mandate/good fortune to rule."[156][note 50]

Christianity

Khazaria long served as a buffer state between the Byzantine empire and both the nomads of the northern steppes and the Umayyad empire, after serving as Byzantium's proxy against the Sasanian Persian empire. The alliance was dropped around 900. Byzantium began to encourage the Alans to attack Khazaria and weaken its hold on Crimea and the Caucasus, while seeking to obtain an entente with the rising Rus' power to the north, which it aspired to convert to Christianity.[15]

On Khazaria's southern flank, both Islam and Byzantine Christianity were proselytising great powers. Byzantine success in the north was sporadic, although Armenian and Albanian missions from Derbend built churches extensively in maritime Daghestan, then a Khazar district.[157] Buddhism also had exercised an attraction on leaders of both the Eastern (552–742) and Western Qağanates (552–659), the latter being the progenitor of the Khazar state.[158] In 682, according to the Armenian chronicle of Movsês Dasxuranc'i, the king of Caucasian Albania, Varaz Trdat, dispatched a bishop, Israyêl, to convert Caucasian "Huns" who were subject to the Khazars, and managed to convince Alp Ilut'uêr, a son-in-law of the Khazar qağan, and his army, to abandon their shamanising cults and join the Christian fold.[159][note 51]

The Arab Georgian martyr St Abo, who converted to Christianity within the Khazar kingdom around 779–80, describes local Khazars as irreligious.[note 52] Some reports register a Christian majority at Samandar,[note 53] or Muslim majorities.[note 54]

Judaism

The conversion of the Khazars to Judaism is mentioned in external sources and it is also mentioned in the Khazar Correspondence, but doubts of its authenticity persist.[160] Hebrew documents, whose authenticity was long doubted and challenged,[note 55] are now widely accepted by specialists as either authentic or as reflecting internal Khazar traditions.[note 56][note 57][note 58][163] Archaeological evidence for conversion, on the other hand, remains elusive,[note 59][note 60] and may reflect either the incompleteness of excavations, or that the stratum of actual adherents was thin.[note 61] Conversion of steppe or peripheral tribes to a universal religion is a fairly well attested phenomenon,[note 62] and the Khazar conversion to Judaism, although unusual, would not have been without precedent.[note 63] The topic is emotionally charged in Israel,[note 64] and a few scholars, such as Moshe Gil (2011) and Shaul Stampfer (2013) argue that the conversion of the Khazar elite to Judaism never happened.[160][167]

Jews from both the Islamic world and Byzantium are known to have migrated to Khazaria during periods of persecution under Heraclius, Justinian II, Leo III, and Romanus Lakapēnos.[168][169] For Simon Schama, Jewish communities from the Balkans and the Bosphoran Crimea, especially from Panticapaeum, began migrating to the more hospitable climate of pagan Khazaria in the wake of these persecutions, and were joined there by Jews from Armenia. The Geniza fragments, he argues, make it clear the Judaising reforms sent roots down into the whole of the population.[170] The pattern is one of an elite conversion preceding large-scale adoption of the new religion by the general population, which often resisted the imposition.[158] One important condition for mass conversion was a settled urban state, where churches, synagogues or mosques provided a focus for religion, as opposed to the free nomadic lifestyle of life on the open steppes.[note 65] A tradition of the Iranian Judeo-Tats claims that their ancestors were responsible for the Khazar conversion.[171] A legend traceable to the 16th-century Italian rabbi Judah Moscato attributed it to Yitzhak ha-Sangari.[172][173][174]

Both the date of the conversion, and the extent of its influence beyond the elite,[note 66] often minimised in some scholarship,[note 67] are a matter of dispute,[note 68] but at some point between 740 and 920 CE, the Khazar royalty and nobility appear to have converted to Judaism, in part, it is argued, perhaps to deflect competing pressures from Arabs and Byzantines to accept either Islam or Orthodoxy.[note 69][note 70]

History of discussions about Khazar Jewishness

The earliest surviving Arabic text that refers to Khazar Jewishness appears to be that which was written by ibn Rustah, a Persian scholar who wrote an encyclopedic work on geography in the early tenth century.[175] It is believed that ibn Rustah derived much of his information from the works of his contemporary Abu al Jayhani based in Central Asia.

Christian of Stavelot in his Expositio in Matthaeum Evangelistam (c. 860–870s) refers to Gazari, presumably Khazars, as living in the lands of Gog and Magog, who were circumcised and omnem Judaismum observat—observing all the laws of Judaism.[note 71] New numismatic evidence of coins dated 837/8 bearing the inscriptions arḍ al-ḫazar (Land of the Khazars), or Mûsâ rasûl Allâh (Moses is the messenger of God, in imitation of the Islamic coin phrase: Muḥammad rasûl Allâh) suggest to many the conversion took place in that decade.[note 72] Olsson argues that the 837/8 evidence marks only the beginning of a long and difficult official Judaization that concluded some decades later.[note 73] A 9th-century Jewish traveller, Eldad ha-Dani, is said to have informed Spanish Jews in 883 that there was a Jewish polity in the East, and that fragments of the legendary Ten Lost Tribes, part of the line of Simeon and half-line of Manasseh, dwelt in "the land of the Khazars", receiving tribute from some 25 to 28 kingdoms.[176][177][178] Another view holds that by the 10th century, while the royal clan officially claimed Judaism, a non-normative variety of Islamisation took place among the majority of Khazars.[179]

By the 10th century, the letter of King Joseph asserts that, after the royal conversion, "Israel returned (yashuvu yisra'el) with the people of Qazaria (to Judaism) in complete repentance (bi-teshuvah shelemah)."[180] Persian historian Ibn al-Faqîh wrote that "all the Khazars are Jews, but they have been Judaized recently". Ibn Fadlân, based on his Caliphal mission (921–922) to the Volga Bulğars, also reported that "the core element of the state, the Khazars, were Judaized",[note 74] something underwritten by the Qaraite scholar Ya'kub Qirqisânî around 937.[note 75] The conversion appears to have occurred against a background of frictions arising from both an intensification of Byzantine missionary activity from the Crimea to the Caucasus, and Arab attempts to wrest control over the latter in the 8th century CE,[181] and a revolt, put down, by the Khavars around the mid-9th century is often invoked as in part influenced by their refusal to accept Judaism.[182] Modern scholars generally[note 76] see the conversion as a slow process through three stages, which accords with Richard Eaton's model of syncretic inclusion, gradual identification and, finally, displacement of the older tradition.[note 77][183]

Sometime between 954 and 961, Ḥasdai ibn Shaprūṭ, from al-Andalus (Muslim Spain), wrote a letter of inquiry addressed to the ruler of Khazaria, and received a reply from Joseph of Khazaria. The exchanges of this Khazar Correspondence, together with the Schechter Letter discovered in the Cairo Geniza and the famous plato nizing dialogue[184] by Judah Halevi, Sefer ha-Kuzari ("Book (of) The Khazari"), which plausibly drew on such sources,[note 78] provide us with the only direct evidence of the indigenous traditions[note 79] concerning the conversion. King Bulan[note 80] is said to have driven out the sorcerers,[note 81] and to have received angelic visitations exhorting him to find the true religion, upon which, accompanied by his vizier, he travelled to desert mountains of Warsān on a seashore, where he came across a cave rising from the plain of Tiyul in which Jews used to celebrate the Sabbath. Here he was circumcised.[note 82] Bulan is then said to have convened a royal debate between exponents of the three Abrahamic religions. He decided to convert when he was convinced of Judaism's superiority. Many scholars situate this c. 740, a date supported by Halevi's own account.[188][189] The details are both Judaic[note 83] and Türkic: a Türkic ethnogonic myth speaks of an ancestral cave in which the Ashina were conceived from the mating of their human ancestor and a wolf ancestress.[190][note 84][191] These accounts suggest that there was a rationalising syncretism of native pagan traditions with Jewish law, by melding through the motif of the cave, a site of ancestral ritual and repository of forgotten sacred texts, Türkic myths of origin and Jewish notions of redemption of Israel's fallen people.[187] It is generally agreed they adopted Rabbinical rather than Qaraite Judaism.[192]

Ibn Fadlan reports that the settlement of disputes in Khazaria was adjudicated by judges hailing each from his community, be it Christian, Jewish, Muslim, or Pagan.[193] Some evidence suggests that the Khazar king saw himself as a defender of Jews even beyond the kingdom's frontiers, retaliating against Muslim or Christian interests in Khazaria in the wake of Islamic and Byzantine persecutions of Jews abroad.[194][note 85] Ibn Fadlan recounts specifically an incident in which the king of Khazaria destroyed the minaret of a mosque in Atil as revenge for the destruction of a synagogue in Dâr al-Bâbûnaj, and allegedly said he would have done worse were it not for a fear that the Muslims might retaliate in turn against Jews.[192][195] Ḥasdai ibn Shaprūṭ sought information on Khazaria in the hope he might discover "a place on this earth where harassed Israel can rule itself" and wrote that, were it to prove true that Khazaria had such a king, he would not hesitate to forsake his high office and his family in order to emigrate there.[note 86]

Albert Harkavy noted in 1877 that an Arabic commentary on Isaiah 48:14 ascribed to Saadia Gaon or to the Karaite scholar Benjamin Nahâwandî, interpreted "The Lord hath loved him" as a reference "to the Khazars, who will go and destroy Babel" (i.e., Babylonia), a name used to designate the country of the Arabs. This has been taken as an indication of hopes by Jews that the Khazars might succeed in destroying the Caliphate.[172]

Islam

In 965, as the Qağanate was struggling against the victorious campaign of the Rus' prince Sviatoslav, the Islamic historian Ibn al-Athîr mentions that Khazaria, attacked by the Oğuz, sought help from Khwarezm, but their appeal was rejected because they were regarded as "infidels" (al-kuffâr:pagans). Save for the king, the Khazarians are said to have converted to Islam in order to secure an alliance, and the Turks were, with Khwarezm's military assistance, repelled. It was this that, according to Ibn al-Athîr, led the Jewish king of Khazar to convert to Islam.[125]

Genetics

Nine skeletons dating to the 7th–9th centuries excavated from elite military burial mounds of the Khazar Khaganate (in the modern Rostov region) were analyzed in two genetic studies (from 2019 and 2021). According to the 2019 study, the results "confirm the Turkic roots of the Khazars, but also highlight their ethnic diversity and some integration of conquered populations". The samples did not show a genetic connection to Ashkenazi Jews, and the results do not support the hypothesis of Ashkenazi Jews being descendants of the Khazars.[196] In the 2021 study the results showed both European and East Asian paternal haplogroups in the samples: three individuals carried R1a Y-haplogroup, two had C2b, and the rest carried haplogroups G2a, N1a, Q, and R1b, respectively. According to the authors, "The Y-chromosome data are consistent with the results of the craniological study and genome-wide analysis of the same individuals in the sense that they show mixed genetic origins for the early medieval Khazar nobility".[197]

Claims of Khazar ancestry

Claims of Khazar origins of peoples, or suggestions that the Khazars were absorbed by them, have been made with regard to the Kazakhs, the Hungarians, the Judaizing Slavic Subbotniks, the Muslim Karachays, the Kumyks, the Avars, the Cossacks of the Don and the Ukrainian Cossacks (see Khazar hypothesis of Cossack ancestry), the Turkic-speaking Krymchaks and their Crimean neighbours the Karaites, the Moldavian Csángós, the Mountain Jews and others.[20][198][21][22] Turkic-speaking Crimean Karaites (known in the Crimean Tatar language as Qaraylar), some of whom migrated in the 19th century from the Crimea to Poland and Lithuania have claimed Khazar origins. Specialists in Khazar history question the connection.[199][200][note 87] Scholarship is likewise sceptical of claims that the Tatar-speaking Krymchak Jews of the Crimea descend from Khazars.[201]

Crimean Karaites and Krymchaks

In 1839, the Karaim scholar Abraham Firkovich was appointed by the Russian government as a researcher into the origins of the Jewish sect known as the Karaites.[202] In 1846, one of his acquaintances, the Russian orientalist Vasilii Vasil'evich Grigor'ev (1816–1881), theorised that the Crimean Karaites were of Khazar stock. Firkovich vehemently rejected the idea,[203] a position seconded by Firkovich, who hoped that by "proving" his people were of Turkic origin, would secure them exception from Russian anti-Jewish laws, since they bore no responsibility for Christ's crucifixion.[204] This idea has a notable impact in Crimean Karaite circles.[note 88] It is now believed that he forged much of this material on Khazars and Karaites.[206] Specialists in Khazar history also question the connection.[200][note 87] Brook's genetic study of European Karaites found no evidence of a Khazar or Turkic origin for any uniparental lineage but did reveal the European Karaites' links to Egyptian Karaites and to Rabbinical Jewish communities.[207][208]

Another Turkic Crimean group, the Krymchaks had retained very simple Jewish traditions, mostly devoid of halakhic content, and very much taken with magical superstitions which, in the wake of the enduring educational efforts of the great Sephardi scholar Chaim Hezekiah Medini, came to conform with traditional Judaism.[209]

Though the assertion they were not of Jewish stock enabled many Crimean Karaites to survive the Holocaust, which led to the murder of 6,000 Krymchaks, after the war, many of the latter, somewhat indifferent to their Jewish heritage, took a cue from the Crimean Karaites, and denied this connection in order to avoid the antisemitic effects of the stigma attached to Jews.[210]

Ashkenazi-Khazar theories

Several scholars have suggested that instead of disappearing after the dissolution of their Empire, the Khazars migrated westward and eventually, they formed part of the core of the later Ashkenazi Jewish population of Europe. This hypothesis is greeted with scepticism or caution by most scholars.[note 89][note 90][note 91]

The German Orientalist Karl Neumann, in the context of an earlier controversy about possible connections between the Khazars and the ancestors of the Slavic peoples, suggested as early as 1847 that emigrant Khazars might have influenced the core population of Eastern European Jews.[note 92]

The theory was then taken up by Albert Harkavi in 1869, when he also claimed that a possible link existed between the Khazars and the Ashkenazim,[note 93] but the theory that Khazar converts formed a major proportion of the Ashkenazim was first proposed to the Western public in a lecture which was delivered by Ernest Renan in 1883.[note 94][211] Occasional suggestions that there was a small Khazar component in East European Jews emerged in works by Joseph Jacobs (1886), Anatole Leroy-Beaulieu, a critic of antisemitism (1893),[212] Maksymilian Ernest Gumplowicz,[note 95] and by the Russian-Jewish anthropologist Samuel Weissenberg.[note 96] In 1909, Hugo von Kutschera developed the notion into a book-length study,[214][215] arguing that the Khazars formed the foundational core of the modern Ashkenazim.[214] Maurice Fishberg introduced the notion to American audiences in 1911.[213][216] The idea was also taken up by the Polish-Jewish economic historian and General Zionist Yitzhak Schipper in 1918.[note 97][217] Israel Bartal has suggested that from the Haskalah onwards, polemical pamphlets against the Khazars were inspired by Sephardi organizations which opposed the Khazaro-Ashkenazim.[218]

Scholarly anthropologists, such as Roland B. Dixon (1923), and writers such as H. G. Wells (1920) used it to argue that "The main part of Jewry never was in Judea",[note 98][219] a thesis that was to have a political echo in later opinion.[note 99][220][221]

In 1932, Samuel Krauss ventured the theory that the biblical Ashkenaz referred to northern Asia Minor, and he identified it as the ancestral homeland of the Khazars, a position which was immediately disputed by Jacob Mann.[222] Ten years later, in 1942, Abraham N. Polak (sometimes referred to as Poliak), later professor for the history of the Middle Ages at Tel Aviv University, published a Hebrew monograph in which he concluded that the East European Jews came from Khazaria.[note 100][note 101][223] D.M. Dunlop, writing in 1954, thought that very little evidence supported what he considered a mere assumption, and he also argued that the Ashkenazi-Khazar descent theory went far beyond what "our imperfect records" permit.[224] In 1955, Léon Poliakov, who assumed that the Jews of Western Europe resulted from a "panmixia" in the first millennium, asserted that it was widely assumed that Europe's Eastern Jews were descended from a mixture of Khazarian and German Jews.[note 102] Poliak's work found some support in Salo Wittmayer Baron and Ben-Zion Dinur,[note 103][note 104] but was dismissed by Bernard Weinryb as a fiction (1962).[note 105] Bernard Lewis was of the opinion that the word in Cairo Geniza interpreted as Khazaria is actually Hakkari and therefore it relates to the Kurds of the Hakkari mountains in southeast Turkey.[228]

The Khazar-Ashkenazi hypothesis came to the attention of a much wider public with the publication of Arthur Koestler's The Thirteenth Tribe in 1976,[229] which was both positively reviewed and dismissed as a fantasy, and a somewhat dangerous one. Israeli historian Zvi Ankori argued that Koestler had allowed his literary imagination to espouse Poliak's thesis, which most historians dismissed as speculative.[135] Israel's ambassador to Britain branded it "an anti-Semitic action financed by the Palestinians", while Bernard Lewis claimed that the idea was not supported by any evidence whatsoever, and it had been abandoned by all serious scholars.[229][note 106] Raphael Patai, however, registered some support for the idea that Khazar remnants had played a role in the growth of Eastern European Jewish communities,[note 107] and several amateur researchers, such as Boris Altschüler (1994),[200] kept the thesis in the public eye. The theory has been occasionally manipulated to deny Jewish nationhood.[229][233] Recently, a variety of approaches, from linguistics (Paul Wexler)[234] to historiography (Shlomo Sand)[235] and population genetics (Eran Elhaik, a geneticist from the University of Sheffield)[236] have emerged to keep the theory alive.[237] In a broad academic perspective, both the idea that the Khazars converted en masse to Judaism and the suggestion they emigrated to form the core population of Ashkenazi Jewry, remain highly polemical issues.[238] One thesis held that the Khazar Jewish population went into a northern diaspora and had a significant impact on the rise of Ashkenazi Jews. Connected to this thesis is the theory, expounded by Paul Wexler, dissenting from the majority of Yiddish linguists, that the grammar of Yiddish contains a Khazar substrate.[239]

Use in antisemitic polemic

According to Michael Barkun, while the Khazar hypothesis generally never played any major role in the development of anti-Semitism,[240] it has exercised a noticeable influence on American antisemites since the restrictions on immigration were imposed in the 1920s.[note 108][note 109] Maurice Fishberg and Roland B. Dixon's works were later exploited in racist and religious polemical literature, particularly in literature which advocated British Israelism, both in Britain and the United States.[213][note 110] Particularly after the publication of Burton J. Hendrick's The Jews in America, (1923)[241] it began to enjoy a vogue among advocates of immigration restriction in the 1920s; racial theorists[242] such as Lothrop Stoddard; antisemitic conspiracy-theorists such as the Ku Klux Klan's Hiram Wesley Evans; and some anti-communist polemicists such as John O. Beaty[note 111] and Wilmot Robertson, whose views influenced David Duke.[243] According to Yehoshafat Harkabi (1968) and others,[note 112] it played a role in Arab anti-Zionist polemics, and took on an antisemitic edge. Bernard Lewis, noting in 1987 that Arab scholars had dropped it, remarked that it only occasionally emerged in Arab political discourse.[note 113] It has also played some role in Soviet antisemitic chauvinism[note 114] and Slavic Eurasian historiography; particularly, in the works of scholars like Lev Gumilev,[245] it came to be exploited by the white supremacist Christian Identity movement[246] and even by terrorist esoteric cults like Aum Shinrikyō.[247] The Kazar hypothesis was further exploited by esoteric fascists such as Miguel Serrano, referring to a lost Palestinabuch by the German Nazi-scholar Herman Wirth, who claimed to have proven that the Jews descended from a prehistoric migrant group parasiting on the Great Civilizations.[248]

Genetic studies

The hypothesis of Khazarian ancestry in Ashkenazi has also been a subject of vehement disagreements in the field of population genetics,[note 115] wherein claims have been made concerning evidence both for and against it. Eran Elhaik argued in 2012 for a significant Khazar component in the paternal line based on the study of Y-DNA of Ashkenazi Jews using Caucasian populations—Georgians, Armenians and Azerbaijani Jews—as proxies.[note 116] The evidence from historians he used has been criticised by Shaul Stampfer[249] and the technical response to such a position from geneticists is mostly dismissive, arguing that, if traces of descent from Khazars exist in the Ashkenazi gene pool, the contribution would be quite minor,[250][251][252][253][note 117] or insignificant.[254][255] One geneticist, Raphael Falk, has argued that "national and ethnic prejudices play a central role in the controversy."[note 118] According to Nadia Abu El-Haj, the issues of origins are generally complicated by the difficulties of writing history via genome studies and the biases of emotional investments in different narratives, depending on whether the emphasis lies on direct descent or on conversion within Jewish history. At the time of her writing, the lack of Khazar DNA samples that might allow verification also presented difficulties.[note 119]

In literature

The Kuzari is an influential work written by the medieval Spanish Jewish philosopher and poet Rabbi Yehuda Halevi (c. 1075–1141). Divided into five essays (ma'amarim), it takes the form of a fictional dialogue between the pagan king of the Khazars and a Jew who was invited to instruct him in the tenets of the Jewish religion. The intent of the work, although based on Ḥasdai ibn Shaprūṭ's correspondence with the Khazar king, was not historical, but rather to defend Judaism as a revealed religion, written in the context, firstly of Karaite challenges to the Spanish rabbinical intelligentsia, and then against temptations to adapt Aristotelianism and Islamic philosophy to the Jewish faith.[258] Originally written in Arabic, it was translated into Hebrew by Judah ibn Tibbon.[184]

Benjamin Disraeli's early novel Alroy (1833) draws on Menachem ben Solomon's story.[259] The question of mass religious conversion and the indeterminability of the truth of stories about identity and conversion are central themes of Milorad Pavić's best-selling mystery story Dictionary of the Khazars.[260]

H.N. Turteltaub's Justinian, Marek Halter's Book of Abraham and Wind of the Khazars, and Michael Chabon's Gentlemen of the Road allude to or feature elements of Khazar history or create fictional Khazar characters.[261]

Cities associated with the Khazars

Cities associated with the Khazars include Atil, Khazaran, Samandar; in the Caucasus, Balanjar, Kazarki, Sambalut, and Samiran; in Crimea and the Taman region, Kerch, Theodosia, Yevpatoria (Güzliev), Samkarsh (also called Tmutarakan, Tamatarkha), and Sudak; and in the Don valley, Sarkel. A number of Khazar settlements have been discovered in the Mayaki-Saltovo region. Some scholars suppose that the Khazar settlement of Sambat on the Dnieper refers to the later Kyiv.[note 120]

See also

Notes

Footnotes

Resource notes

- "Kiev in Khazar is Sambat, the same as the Hungarian word szombat, 'Saturday', which is likely to have been derived from the Khazar Jews living in Kyiv." (Róna-Tas 1999, p. 152)

Citations

Bibliography

- Abu El-Haj, Nadia (2012). The Genealogical Science: The Search for Jewish Origins and the Politics of Epistemology. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-20142-9 – via Google Books.

- Abulafia, David (1987) [First published 1952]. "Asia, Africa and the Trade of Medieval Europe". In Postan, Michael Moïssey; Habakkuk, H.J.; Miller, Edward (eds.). The Cambridge Economic History of Europe: Trade and industry in the Middle Ages. Vol. 2. Cambridge University Press. pp. 402–473. ISBN 978-0-521-08709-4 – via Google Books.

- Altschüler, Boris (1994). Geheimbericht aus der Grossen Steppe. Die Wahrheit über das Reich der Russen [Secret report from the Great Steppe. The truth about the empire of the Russians] (in German). Saarbrücken: Altschüler. ISBN 978-3-9803917-0-2 – via Google Books.

- Atzmon G, Hao L, Pe'er I, Velez C, Pearlman A, Palamara PF, Morrow B, Friedman E, Oddoux C, Burns E, Ostrer H (June 2010). "Abraham's children in the genome era: major Jewish diaspora populations comprise distinct genetic clusters with shared Middle Eastern Ancestry". American Journal of Human Genetics. 86 (6): 850–859. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.04.015. PMC 3032072. PMID 20560205.

- Bailey, H.W. (1949). "A Khotanese text concerning the Turks in Kanṭṣou" (PDF). Asia Major. New Series 1.1: 28–52.

- Bailey, H.W. (1951). "The Staël-Holstein Miscellany" (PDF). Asia Major. New Series 2.1: 1–45.

- Barkun, Michael (1997). Religion and the Racist Right: The Origins of the Christian Identity Movement. University of North Carolina Press. p. 141. ISBN 978-0-8078-4638-4 – via Internet Archive.

- Barkun, Michael (2012). "Anti-Semitism from Outer Space: The Protocols in the UFO Subculture". In Landes, Richard Allen; Katz, Steven T. (eds.). The Paranoid Apocalypse: A Hundred-year Retrospective on the Protocols of the Elders of Zion. New York University Press. pp. 163–171. ISBN 978-0-8147-4945-6 – via Google Books.

- Baron, Salo Wittmayer (1957). A Social and Religious History of the Jews. Vol. 3. Columbia University Press – via Google Books.

- Barthold, Vasili (1993) [First published 1936]. "Khazar". In Houtsma, Martijn Theodoor; Bosworth, C.E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W.P. (eds.). First Encyclopedia of Islam, 1913–1936. Vol. 4. Brill. pp. 935–937. ISBN 978-90-04-09790-2 – via Google Books.

- Bauer, Susan Wise (2010). The History of the Medieval World: From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-07817-6 – via Google Books.

- Beckwith, Christopher I. (2011) [First published 2009]. Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the Present. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-15034-5 – via Google Books.

- Behar, D. M.; Metspalu, M.; Baran, Y.; Kopelman, N. M.; Yunusbayev, B.; Gladstein, A.; et al. (2013). "No Evidence of a Khazar origin for the Ashkenazi Jews". Human Biology. 85 (6): 859–900. doi:10.3378/027.085.0604. PMID 25079123. S2CID 2173604.

- Behar, Doron M; Thomas, Mark G; Skorecki, Karl; Hammer, Michael F; et al. (October 2003). "Multiple Origins of Ashkenazi Levites: Y Chromosome Evidence for Both Near Eastern and European Ancestries". American Journal of Human Genetics. 73 (4): 768–779. doi:10.1086/378506. PMC 1180600. PMID 13680527.

- Blady, Ken (2000). Jewish Communities in Exotic Places. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-765-76112-5 – via Google Books.

- Boller, Paul F. (1992). Memoirs of an Obscure Professor: And Other Essays. TCU Press. ISBN 978-0-87565-097-5 – via Google Books.

- Bowersock, G.W. (2013). The Throne of Adulis: Red Sea Wars on the Eve of Islam. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-199-33384-4 – via Google Books.

- Bowman, Stephen B.; Ankori, Zvi (2001). The Jews of Byzantium 1204–1453. Bloch Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-8197-0703-1 – via Google Books.

- Brook, Kevin Alan (2006). The Jews of Khazaria. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 192. ISBN 978-144220302-0.

- Brook, Kevin Alan (2010) [First published 1999]. The Jews of Khazaria (2nd ed.). Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-7425-4982-1 – via Google Books.

- Brook, Kevin Alan (Summer 2014). "The Genetics of Crimean Karaites" (PDF). Karadeniz Arastirmalari. 11 (42): 69–84. doi:10.12787/KARAM859. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 June 2019. Retrieved 12 July 2020.

- Brook, Kevin Alan (2018). The Jews of Khazaria (3rd ed.). Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-5381-0342-5.

- Brook, Kevin Alan (2022). The Maternal Genetic Lineages of Ashkenazic Jews. Academic Studies Press. ISBN 978-1-64469-984-3.

- Browning, Robert (1992) [First published 1980]. The Byzantine Empire (2nd ed.). Catholic University of America Press. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-8132-0754-4 – via Internet Archive.

- Burrage Dixon, Roland (1923). The Racial History of Man. C. Scribners sons.

- Cahen, Claude (2011) [First published 1997]. L'Islam, des origines au début de l'Empire ottoman [Islam, from its origins to the beginning of the Ottoman Empire] (in French) (2nd ed.). Hachette. ISBN 978-2-8185-0155-9 – via Google Books.

- Cameron, Averil (1996). "Byzantines and Jews: some recent work on early Byzantium". Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies. 20: 249–274. doi:10.1179/byz.1996.20.1.249. S2CID 162277927.

- Cameron, Averil; Herrin, Judith (1984). Constantinople in the Early Eighth Century: The Parastaseis Syntomoi Chronikai: Introduction, Translation, and Commentary. Columbia Studies in the Classical Tradition. Vol. 10. Brill Archive. ISBN 978-90-04-07010-3 – via Google Books.

- Cohen, Mark R. (2005). The Voice of the Poor in the Middle Ages: An Anthology of Documents from the Cairo Geniza. Jews, Christians, and Muslims from the Ancient to the Modern World Series. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-09271-3.

- Cokal, Susann (28 October 2007). "Jews With Swords". The New York Times. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- Costa, M. D.; Pereira, Joana B.; Richards, Martin B. (8 October 2013). "A substantial prehistoric European ancestry amongst Ashkenazi maternal lineages". Nature Communications. 4: 2543. Bibcode:2013NatCo...4.2543C. doi:10.1038/ncomms3543. PMC 3806353. PMID 24104924.

- Cross, Samuel Hazzard; Sherbowitz-Wetzor, Olgerd P., eds. (1953). The Russian Primary Chronicle (Laurentian text) (PDF). Translated by Cross, Samuel Hazzard; Sherbowitz-Wetzor, Olgerd P. Cambridge, MA: The Mediaeval Academy of America. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 October 2013.

- Davies, Alan (1992). "The Keegstra Affair". In Davies, Alan (ed.). Antisemitism in Canada: History and Interpretation. Wilfrid Laurier University Press. pp. 227–248. ISBN 978-0-889-20216-0 – via Google Books.

- DeWeese, Devin A. (1994). Islamization and Native Religion in the Golden Horde: Baba Tükles and Conversion to Islam in Historical and Epic Tradition. Hermeneutics, Studies in the History of Religions. Penn State Press. ISBN 978-0-271-04445-3 – via Google Books.

- Dinur, Ben-Zion (1961). Yisrael ba-gola. Vol. 1 (3rd ed.). Bialik Institute.

- Dobrovits, M. (2004). "The Thirty Tribes of the Turks". Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae. 57 (3): 259. doi:10.1556/aorient.57.2004.3.1.

- Dubnov, Simon (1980). History of the Jews: From the Roman Empire to the Early Medieval Period. Vol. 2. Associated University Presses. ISBN 978-0-8453-6659-2 – via Google Books.

- Dunlop, Douglas Morton (1954). History of the Jewish Khazars. New York, NY: Schocken Books – via Google Books.