| |

Company headquarters building in Bowling Green, Kentucky | |

| Type | Subsidiary |

|---|---|

| Industry | Textile, sports equipment |

| Founded | 1851 in Warwick, Rhode Island, U.S. (as "B.B and R Knight Corp.)[1] |

| Founders | Robert Knight & Benjamin Knight[2] |

| Headquarters | , |

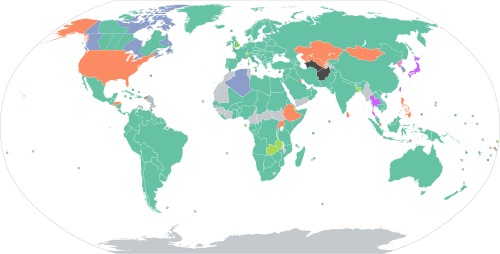

Area served | Worldwide |

| Products | Clothing (casual wear, activewear), sports equipment |

| Brands | Exquisite Form |

| Owner | Berkshire Hathaway |

Number of employees | 32,400 |

| Subsidiaries |

|

| Website | fruit.com |

Fruit of the Loom is an American company that manufactures clothing, particularly casual wear and underwear. The company's world headquarters is in Bowling Green, Kentucky. Since 2002, it has been a wholly owned subsidiary of Berkshire Hathaway.

Products manufactured by Fruit of the Loom itself and through its subsidiaries include clothing (t-shirts, hoodies, jackets, sweatpants, shorts and lingerie), and sports equipment (softballs and basketballs) manufactured and commercialized by Spalding.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fruit_of_the_Loom

| |

| Type | Brand |

|---|---|

| Genre | Clothing |

| Founded | July 26, 1900 (as Shamrock Knitting Mills) |

| Founder | John Wesley Hanes |

| Headquarters | , |

| Products | Underwear, casualwear, hosiery and socks |

| Owner | Hanes, Inc. |

| Parent | Hanesbrands |

| Website | www |

Hanes (founded in 1900) and Hanes Her Way (founded in 1985) is a brand of clothing.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hanes

| Type | Private company |

|---|---|

| Industry | Fashion |

| Founded | 1954 |

| Founder | Ada Masotti |

| Headquarters | , |

Number of locations | 150 |

Area served | Worldwide |

Key people | Silvio Scaglia (Chairman) Nicole Rendone (Creative Director) |

| Products | Lingerie, beachwear, sleepwear, ready-to-wear, accessories |

| Owner | Tennor Holding BV |

| Website | www |

La Perla is a London-headquartered [1] Italian lingerie and swimwear maker owned by German entrepreneur Lars Windhorst through Tennor Holding B.V.[2] The brand was founded by couturière Ada Masotti in Bologna in 1954.[3]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/La_Perla_(clothing)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/La_Perla_(painting)

| |

Agent Provocateur's first store, on Broadwick Street, Soho, London | |

| Type | Private |

|---|---|

| Industry | Apparel |

| Founded | 1994 |

| Founders | Joseph Corré Serena Rees |

| Headquarters | , |

Key people | Sarah Shotton (Creative director) |

| Products | lingerie, sleepwear, hosiery, swimwear, accessories, outerwear, fragrances |

Number of employees | 600[1] (2017) |

| Website | https://www.agentprovocateur.com |

Agent Provocateur is a British lingerie retailer founded in 1994 by Joseph Corré and Serena Rees.[2] The company has stores in 13 countries.[3]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Agent_Provocateur_(lingerie)

Underwear, underclothing, or undergarments are items of clothing worn beneath outer clothes, usually in direct contact with the skin, although they may comprise more than a single layer. They serve to keep outer clothing from being soiled or damaged by bodily excretions, to lessen the friction of outerwear against the skin, to shape the body, and to provide concealment or support for parts of it. In cold weather, long underwear is sometimes worn to provide additional warmth. Special types of undergarments have religious significance. Some items of clothing are designed as undergarments, while others, such as T-shirts and certain types of shorts, are appropriate both as underwear and outerwear. If made of suitable material or textile, some underwear can serve as nightwear or swimwear, and some undergarments are intended for sexual attraction or visual appeal.

Undergarments are generally of two types, those that are worn to cover the torso and those that are worn to cover the waist and legs, although there are also underclothes which cover both. Different styles of underwear are generally worn by females and males. Undergarments commonly worn by females today include bras and panties (knickers in British English), while males often wear classic briefs, boxer briefs, or boxer shorts. Items worn by both sexes include T-shirts, sleeveless shirts (also called singlets, tank tops, A-shirts, or vests), bikini underpants, thongs, G-strings and T-fronts.

Terminology

Undergarments are known by a number of terms. Underclothes, underclothing and underwear are formal terms, while undergarments may be more casually called, in Australia, Reg Grundys (rhyming slang for undies) and Reginalds, and, in the United Kingdom, smalls (from the earlier smallclothes) and (historically) unmentionables. In the United States, women's underwear may be known as delicates due to the recommended washing machine cycle or because they are, simply put, delicate.[citation needed]

Women's undergarments collectively are also called lingerie. They also are called intimate clothing and intimates.

An undershirt (vest in the United Kingdom) is a piece of underwear covering the torso, while underpants (often called pants in the United Kingdom), drawers, and undershorts cover the genitals and buttocks. Terms for specific undergarments are shown in the table below.

Function

Underwear is worn for a variety of reasons. They keep outer garments from being soiled by perspiration, urine,[1] semen, pre-seminal fluid, feces, vaginal discharge, and menstrual blood.[2] Women's brassieres provide support for the breasts, and men's briefs serve the same function for the male genitalia. A corset may be worn as a foundation garment to provide support for the breasts and torso, as well as to alter a woman's body shape. For additional support and protection when playing sports, men often wear more tightly fitting underwear, including jockstraps and jockstraps with cup pocket and protective cup. Women may wear sports bras which provide greater support, thus increasing comfort and reducing the chance of damage to the ligaments of the chest during high-impact exercises such as jogging.[citation needed]

In cold climates, underwear may constitute an additional layer of clothing helping to keep the wearer warm. Underwear may also be used to preserve the wearer's modesty – for instance, some women wear camisoles and slips (petticoats) under clothes that are sheer. Conversely, some types of underwear can be worn for sexual titillation, such as edible underwear or crotchless panties.[citation needed]

Undergarments are worn for insulation under space suits and dry suits. In the case of dry suits, the insulation value of the undergarments is selected to match the expected water temperature and the level of activity for the planned dive or water activity.[3]

Some items of clothing are designed exclusively as underwear, while others such as T-shirts and certain types of shorts are suitable both as underwear and as outer clothing. The suitability of underwear as outer clothing is, apart from the indoor or outdoor climate, largely dependent on societal norms, fashion, and the requirements of the law. If made of suitable material, some underwear can serve as nightwear or swimsuits.[citation needed]

Religious functions

Undergarments can also have religious significance:

- Judaism. To conform with societal dress codes, the tallit katan is often worn beneath the shirt.[citation needed]

- Mormonism. Following their endowment in a temple, Mormons wear special temple garments which help them to remember the teachings of the temple.[4]

- Sikhism. One of the five articles of faith (panj kakaar) worn by Sikh men and women is a certain style of underpants similar to boxer shorts and known as the kacchera.[citation needed]

- Zoroastrianism. Zoroastrians wear an undershirt called a Sedreh that is fastened with a sacred girdle around the waist known as a Kushti.[citation needed]

History

Ancient history

The loincloth is the simplest form of underwear; it was probably the first undergarment worn by human beings. In warmer climates, the loincloth was often the only clothing worn (effectively making it an outer garment rather than an undergarment), as was doubtless its origin, but in colder regions, the loincloth often formed the basis of a person's clothing and was covered by other garments. In most ancient civilizations, this was the only undergarment available.

A loincloth may take three major forms. The first, and simplest, is simply a long strip of material that is passed between the legs and then around the waist. Archaeologists have found the remains of such loincloths made of leather dating back 7,000 years.[5] The ancient Hawaiian malo was of this form, as are several styles of the Japanese fundoshi. Another form is usually called a cache-sexe: a triangle of cloth is provided with strings or loops, which are used to fasten the triangle between the legs and over the genitals. Egyptian king Tutankhamun (1341 BC – 1323 BC) was found buried with numerous linen loincloths of this style.[5] An alternate form is more skirt-like: a cloth is wrapped around the hips several times and then fastened with a girdle.

Men are said to have worn loincloths in ancient Greece and Rome, though it is unclear whether Greek women wore undergarments. There is some speculation that only slaves wore loincloths and that citizens did not wear undergarments beneath their chitons. Mosaics of the Roman period indicate that women (primarily in an athletic context, whilst wearing nothing else) sometimes wore strophiae (breastcloths) or brassieres made of soft leather, along with subligacula which were either in the form of shorts or loincloths. Subligacula were also worn by men.[5]

The fabric used for loincloths may have been wool, linen or a linsey-woolsey blend. Only the upper classes could have afforded imported silk.

The loincloth continues to be worn by people around the world – it is the traditional form of undergarment in many Asian societies, for example. In various, mainly tropical, cultures, the traditional male dress may still consist of only a single garment below the waist or even none at all, with underwear as optional, including the Indian dhoti and lungi, or the Scottish kilt.

Middle Ages and Renaissance

In the Middle Ages, western men's underwear became looser fitting. The loincloth was replaced by loose, trouser-like clothing called braies, which the wearer stepped into and then laced or tied around the waist and legs at about mid-calf. Wealthier men often wore chausses as well, which only covered the legs.[5] Braies (or rather braccae) were a type of trouser worn by Celtic and Germanic tribes in antiquity and by Europeans subsequently into the Middle Ages. In the later Middle Ages they were used exclusively as undergarments.[citation needed]

By the time of the Renaissance, braies had become shorter to accommodate longer styles of chausses. Chausses were also giving way to form-fitting hose,[5] which covered the legs and feet. Fifteenth-century hose were often particolored, with each leg in a different-colored fabric or even more than one color on a leg. However, many types of braies, chausses and hose were not intended to be covered up by other clothing, so they were not actually underwear in the strict sense.

Braies were usually fitted with a front flap that was buttoned or tied closed. This codpiece allowed men to urinate without having to remove the braies completely.[5] Codpieces were also worn with hose when very short doublets – vest- (UK: waistcoat-) like garments tied together in the front and worn under other clothing – were in fashion, as early forms of hose were open at the crotch. Henry VIII of England began padding his codpiece, which caused a spiralling trend of larger and larger codpieces that only ended by the end of the 16th century. It has been speculated that the King may have had the sexually transmitted disease syphilis, and his large codpiece may have included a bandage soaked in medication to relieve its symptoms.[5] Henry VIII also wanted a healthy son and may have thought that projecting himself in this way would portray fertility. Codpieces were sometimes used as a pocket for holding small items.[5]

Over the upper part of their bodies, both medieval men and women usually wore a close-fitting shirt-like garment called a chemise in France, or a smock or shift in England. The forerunner of the modern-day shirt, the chemise was tucked into a man's braies, under his outer clothing. Women wore a chemise underneath their gowns or robes, sometimes with petticoats over the chemise. Elaborately quilted petticoats might be displayed by a cut-away dress, in which case they served a skirt rather than an undergarment. During the 16th century, the farthingale was popular. This was a petticoat stiffened with reed or willow rods so that it stood out from a woman's body like a cone extending from the waist.

Corsets also began to be worn about this time. At first they were called pairs of bodies, which refers to a stiffened decorative bodice worn on top of another bodice stiffened with buckram, reeds, canes, whalebone or other materials. These were not the small-waisted, curved corsets familiar from the Victorian era, but straight-lined stays that flattened the bust.

Men's braies and hose were eventually replaced by simple cotton, silk, or linen drawers, which were usually knee-length trousers with a button flap in the front.[5]

Medieval people wearing only tunics, without underpants, can be seen on works like The Ass in the School by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, in the Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry by Limbourg Brothers, or in the Grimani Breviary: The Month of February by Gerard Horenbout.

In 2012, findings in Lengberg Castle, in Austria, showed that lace and linen brassiere-like garments, one of which greatly resembled the modern bra, date back to hundreds of years before it was thought to exist.[6][7]

Enlightenment and Industrial Age

The invention of the spinning jenny machines and the cotton gin in the second half of the 18th century made cotton fabrics widely available. This allowed factories to mass-produce underwear, and for the first time, large numbers of people began buying undergarments in stores rather than making them at home.

Women's stays of the 18th century were laced behind and drew the shoulders back to form a high, round bosom and erect posture. Colored stays were popular. With the relaxed country styles of the end of the century, stays became shorter and were unboned or only lightly boned, and were now called corsets. As tight waists became fashionable in the 1820s, the corset was again boned and laced to form the figure. By the 1860s, a tiny ("wasp") waist came to be seen as a symbol of beauty, and the corsets were stiffened with whalebone or steel to accomplish this. While "tight lacing" of corsets was not a common practice except among a minority of women, which sometimes led to a woman needing to retire to the fainting room, the primary use of a corset was to create a smooth line for the garments to effect the fashionable shape of the day, using the optical illusion created by the corset and garments together to achieve the look of a smaller waist.[8] By the 1880s, the dress reform movement was campaigning against the alleged pain and damage to internal organs and bones caused by tight lacing. Inez Gaches-Sarraute invented the "health corset", with a straight-fronted busk made to help support the wearer's muscles.

The corset was usually worn over a thin shirt-like shift of linen or cotton or muslin.[9] Skirt styles became shorter and long drawers called pantalettes or pantaloons kept the legs covered. Pantalettes originated in France in the early 19th century, and quickly spread to Britain and America. Pantalettes were a form of leggings or long drawers. They could be one-piece or two separate garments, one for each leg, attached at the waist with buttons or laces. The crotch was left open for hygiene reasons.

As skirts became fuller from the 1830s, women wore many petticoats to achieve a fashionable bell shape. By the 1850s, stiffened crinolines and later hoop skirts allowed ever wider skirts to be worn. The bustle, a frame or pad worn over the buttocks to enhance their shape, had been used off and on by women for two centuries, but reached the height of its popularity in the later 1880s, and went out of fashion for good in the 1890s. Women dressed in crinolines often wore drawers under them for modesty and warmth.

Another common undergarment of the late 19th century for men, women, and children was the union suit. Invented in Utica, New York and patented in 1868, this was a one-piece front-buttoning garment usually made of knitted material with sleeves extending to the wrists and legs down to the ankles. It had a buttoned flap (known colloquially as the "access hatch", "drop seat", or "fireman's flap") in the back to ease visits to the toilet. The union suit was the precursor of long johns, a two-piece garment consisting of a long-sleeved top and long pants possibly named after American boxer John L. Sullivan who wore a similar garment in the ring.[5]

The jockstrap was invented in 1874, by C.F. Bennett of a Chicago sporting goods company, Sharp & Smith, to provide comfort and support for bicycle jockeys riding the cobblestone streets of Boston, Massachusetts.[5] In 1897 Bennett's newly formed Bike Web Company patented and began mass-producing the Bike Jockey Strap.[10]

1900s to 1920s

This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2012) |

By the early 20th century, the mass-produced undergarment industry was booming, and competition forced producers to come up with all sorts of innovative and gimmicky designs to compete. The Hanes company emerged from this boom and quickly established itself as a top manufacturer of union suits, which were common until the 1930s.[5] Textile technology continued to improve, and the time to make a single union suit dropped from days to minutes.

Meanwhile, designers of women's undergarments relaxed the corset. The invention of new, flexible but supportive materials allowed whalebone and steel bones to be removed. The emancipation or liberty bodice offered an alternative to constricting corsets, and in Australia and the UK the liberty bodice became a standard item for girls as well as women.

Men's underwear was also on the rise. Benjamin Joseph Clark, a migrant to Louisiana from New Jersey, opened a venture capitalist firm named Bossier in Bossier Parish. One product manufactured by his firm was tightly fitting boxer shorts that resembled modern underwear. Though the company was bankrupt by the early 20th century, it had some impact on men's underwear design.

Underwear advertising first made an appearance in the 1910s. The first underwear print advertisement in the US appeared in The Saturday Evening Post in 1911 and featured oil paintings by J. C. Leyendecker of the "Kenosha Klosed Krotch". Early underwear advertisements emphasized durability and comfort, and fashion was not regarded as a selling point.

By the end of the 1910s, Chalmers Knitting Company split the union suit into upper and lower sections, effectively inventing the modern undershirt and drawers. Women wore lacier versions of this basic duo known as the camisole and tap pants.

In 1912, the US had its first professional underwear designer. Lindsay "Layneau" Boudreaux, a French immigrant, established the short-lived panty company Layneau. Though her company closed within one year, it had a significant impact on many levels. Boudreaux showed the world that an American woman could establish and run a company, and she also caused a revolution in the underwear industry.

In 1913, a New York socialite named Mary Phelps Jacob created the first modern brassiere by tying two handkerchiefs together with ribbon. Jacob's original intention was to cover the whalebone sticking out of her corset, which was visible through her sheer dress. Jacob began making brassieres for her family and friends, and news of the garment soon spread by word of mouth. By 1914, Jacob had a patent for her design and was marketing it throughout the US. Although women had worn brassiere-like garments in years past, Jacob's was the first to be successfully marketed and widely adopted.

By the end of the decade, trouser-like "bloomers", which were popularized by Amelia Jenks Bloomer (1818–1894) but invented by Elizabeth Smith Miller, gained popularity with the so-called Gibson Girls who enjoyed pursuits such as cycling and tennis. This new female athleticism helped push the corset out of style. The other major factor in the corset's demise was the fact that metal was globally in short supply during the First World War. Steel-laced corsets were dropped in favor of the brassiere.

Meanwhile, World War I soldiers were issued button-front shorts as underwear. The buttons attached to a separate piece of cloth, or "yoke", sewn to the front of the garment, and tightness of fit was adjusted by means of ties on the sides. This design proved so popular that it began to supplant the union suit in popularity by the end of the war. Rayon garments also became widely available in the post-war period.

In the 1920s, manufacturers shifted emphasis from durability to comfort. Union suit advertisements raved about patented new designs that reduced the number of buttons and increased accessibility. Most of these experimental designs had to do with new ways to hold closed the crotch flap common on most union suits and drawers. A new woven cotton fabric called nainsook gained popularity in the 1920s for its durability. Retailers also began selling preshrunk undergarments.

Also in the 1920s, as hemlines of women's dresses rose, women began to wear stockings to cover the exposed legs. Women's bloomers also became much shorter. The shorter bloomers became looser and less supportive as the boyish flapper look came into fashion. By the end of the decade, they came to be known as "step-ins", very much like modern panties but with wider legs. They were worn for the increased flexibility they afforded.

The garter belt was invented to keep stockings from falling.

In 1928, Maidenform, a company operated by Ida Rosenthal, a Jewish immigrant from Russia, developed the brassiere and introduced modern cup sizes for bras.

1930s and 1940s

Modern men's underwear was largely an invention of the 1930s. On 19 January 1935, Coopers Inc. sold the world's first briefs in Chicago. Designed by an "apparel engineer" named Arthur Kneibler, briefs dispensed with leg sections and had a Y-shaped overlapping fly.[5] The company dubbed the design the "Jockey" since it offered a degree of support that had previously only been available from the jockstrap. Jockey briefs proved so popular that over 30,000 pairs were sold within three months of their introduction. Coopers, renaming their company Jockey decades later, sent its "Mascul-line" plane to make special deliveries of "masculine support" briefs to retailers across the US. In 1938, when jockeys were introduced in the UK, they sold at the rate of 3,000 a week.[5]

In this decade, companies also began selling buttonless drawers fitted with an elastic waistband. These were the first true boxer shorts, which were named for their resemblance to the shorts worn by professional fighters. Scovil Manufacturing introduced the snap fastener at this time, which became a popular addition to various kinds of undergarments.

Women of the 1930s brought the corset back, now called the "girdle". The garment lacked the whalebone and metal supports and usually came with a brassiere (now usually called a "bra") and attached garters.

During World War II, elastic waistbands and metal snaps gave way once again to button fasteners due to rubber and metal shortages. Undergarments were harder to find as well, since soldiers abroad had priority to obtain them. By the end of the war, Jockey and Hanes remained the industry leaders in the US, but Cluett, Peabody and Company made a name for itself when it introduced a preshrinking process called "Sanforization", invented by Sanford Cluett in 1933, which came to be licensed by most major manufacturers.

Meanwhile, some women adopted the corset once again, now called the "waspie" for the wasp-shaped waistline it gave the wearer. Many women began wearing the strapless bra as well, which gained popularity for its ability to push the breasts up and enhance cleavage.

1950s and 1960s

Before the 1950s, underwear consisted of simple, functional, white pieces of clothing which were not to be shown in public. In the 1950s, underwear came to be promoted as a fashion item in its own right, and came to be made in prints and colors. Manufacturers also experimented with rayon and newer fabrics like Dacron, nylon, and Spandex.[5] By the 1960, men's underwear was regularly printed in loud patterns, or with messages or images such as cartoon characters. By the 1960s, department stores began offering men's double-seat briefs, an optional feature that would double the wear and add greater comfort. Stores advertising the double thickness seat as well as the manufacturing brands such as Hanes and BVD during this time period can be viewed[11] using Newspapers.com.

Women's undergarments began to emphasize the breasts instead of the waist. The decade saw the introduction of the bullet bra pointed bust, inspired by Christian Dior's "New Look", which featured pointed cups. The original Wonderbra and push-up bra by Frederick's of Hollywood finally hit it big. Women's panties became more colorful and decorative, and by the mid-1960s were available in two abbreviated styles called the hip-hugger and the bikini (named after the Pacific Ocean island of that name), frequently in sheer nylon fabric.

Pantyhose, also called tights in British English, which combined panties and hose into one garment, made their first appearance in 1959,[12] invented by Glen Raven Mills of North Carolina. The company later introduced seamless pantyhose in 1965, spurred by the popularity of the miniskirt. By the end of the decade, the girdle had fallen out of favor as women chose sexier, lighter, and more comfortable alternatives.[13]

With the emergence of the woman's movement in the United States sales for pantyhose dropped off during the later half of the 1960s having soared initially.[12]

1970s to the present day

Underwear as fashion reached its peak in the 1970s and 1980s, and underwear advertisers forgot about comfort and durability, at least in advertising. Sex appeal became a main selling point, in swimwear as well, bringing to fruition a trend that had been building since at least the flapper era.

The tank top, an undershirt named after the type of swimwear dating from the 1920s known as a tank suit or maillot, became popular warm-weather casual outerwear in the US in the 1980s. Performers such as Madonna and Cyndi Lauper were also often seen wearing their undergarments on top of other clothes.

Although worn for decades by exotic dancers, in the 1980s the G-string first gained popularity in South America, particularly in Brazil. Originally a style of swimsuit, the back of the garment is so narrow that it disappears between the buttocks. By the 1990s the design had made its way to most of the Western world, and thong underwear became popular. Today, the thong is one of the fastest-selling styles of underwear among women, and is also worn by men.

While health and practicality had previously been emphasized, in the 1970s retailers of men's underpants began focusing on fashion and sex appeal. Designers such as Calvin Klein began featuring near-naked models in their advertisements for briefs. The increased wealth of the gay community helped to promote a diversity of undergarment choices.[citation needed] In his book The Philosophy of Andy Warhol (1975),[14] Andy Warhol wrote:

I told B I needed some socks too and at least 30 pairs of Jockey shorts. He suggested I switch to Italian-style briefs, the ones with the T-shaped crotch that tends to build you up. I told him I'd tried them once, in Rome, the day I was walking through a Liz Taylor movie – and I didn't like them because they made me too self-aware. It gave me the feeling girls must have when they wear uplift bras.[5]

Warhol liked his Jockey briefs so much that he used a pair as a canvas for one of his dollar-sign paintings.[5]

In the UK in the 1970s, tight jeans gave briefs a continued edge over boxer shorts among young men, but a decade later boxers were given a boost by Nick Kamen's performance in Levi's "Laundrette" TV commercial for its 501 jeans, during which he stripped down to a pair of white boxers in a public laundromat.[5] Briefs however remained popular in America amongst young men from the 1950s until the mid 1990s; while in Australia the brief remains popular today and has become iconic.

The 1990s saw the introduction of boxer briefs, which take the longer shape of boxer shorts but maintain the tightness of briefs. Hip hop stars popularized "sagging", in which loosely fitting pants or shorts were allowed to droop below the waist thusly exposing the waistband or a greater portion of the underpants worn underneath; typically boxer shorts or boxer briefs. The chiseled muscularity of Mark Wahlberg (then known as Marky Mark) in a series of 1990s underwear advertisements for Calvin Klein boxer briefs led to his success as a hip hop star and a Hollywood actor.[5]

Trends

Some people choose not to wear any underpants, a practice sometimes referred to as "going commando", for comfort, to enable their outer garments (particularly those which are form-fitting) to look more flattering, to avoid creating a panty line, because they find it sexually exciting,[15] to increase ventilation and reduce moisture[16][17] or because they do not see any need for them. Certain types of clothes, such as cycling shorts and kilts (See True Scotsman), are designed to be worn or are traditionally worn without underpants.[18][19][20][21][22] This also applies for most clothes worn as nightwear and as swimwear. Some analysts have encouraged people with a higher than average libido to change their underpants more frequently than average due to hygiene-related issues of by-products such as cowper's fluid and vaginal lubrication.[23]

Underwear is sometimes partly exposed for fashion reasons or to titillate. A woman may, for instance, allow the top of her brassiere to be visible from under her collar, or wear a see-through blouse over it. Some men wear T-shirts or A-shirts underneath partly or fully unbuttoned shirts. A common style among young men (2018) is to allow the trousers to sag below the waist, thus revealing the waistband or a greater portion of their underpants. This is commonly referred to (in North America) as "hang-low style". A woman wearing low-rise trousers may expose the upper rear portion of her thong underwear is said to display a "whale tail".

Used underwear

The sale of used female underwear for sexual purposes began in Japan, in stores called burusera, and it was even sold in vending machines. In the 21st century, when the Internet made anonymous mail-order sales possible for individuals, some women in the U.S. and UK, in response to male demand, began selling their dirty panties, and sometimes other underwear. Some men find the odor of a woman's bodily secretions sexually arousing, and will use the dirty panties as a masturbation aid. The sale of dirty panties, sometimes worn for several days, and sometimes customized with requested stains, is a significant niche in the sex work field. A far smaller market sells used male underwear to gay men.[24][25]

Celebrity underwear is sometimes sold. A framed pair of Elvis Presley's dirty underwear sold for $8,000 in 2012.[26][27][28][29] Undergarments of Marilyn Monroe, Queen Elizabeth, and former Austrian Emperor Franz Joseph have been sold at auction.[27] The celebrities Jarvis Cocker, Alison Goldfrapp, Nick Cave, Sacha Baron Cohen, Ricky Gervais, Jah Wobble, Fergie, and Helen Mirren donated underwear to be sold for charity.[30]

Types and styles

Common contemporary types and styles of undergarments are listed in the table below.

| Type | Other Names | Notes | Varieties |

|---|---|---|---|

| Worn by both sexes | |||

| Whole body | |||

Long underwear

|

long johns, long handles | A two-piece undergarment is worn during cold weather consisting of a shirt with sleeves extending to the wrists and leggings/pants/trousers with pant legs reaching down to the ankles. |

|

| Upper body | |||

T-shirt

|

tee | A garment covering a person's torso which is usually made without buttons, pockets, or a collar, and can have short or long sleeves. It is worn by pulling it over the head. It is often worn as an outer garment, especially in informal situations. |

|

Sleeveless shirt

|

tank top, wifebeater (slang), singlet, muscle shirt, athletic shirt, A-shirt | A sleeveless garment similar to a T-shirt. Also sometimes worn as an informal outer garment. |

|

| Lower body | |||

Bikini briefs

|

bikini

Australia: briefs (men’s) |

Usually worn with the waistband lower than the wearer's true waist, and often at the hips, with the leg bands ending at the groin. Men's bikini briefs normally have no fly. |

|

G-string

|

Gee-string, G string | A type of thong consisting of a narrow piece of material that covers or holds the genitals, passes between the buttocks, and is attached to a string around the hips. |

|

| C-String |

Cee-string, C string | A type of thong which is as narrow as a G-string, but without the supporting "string" around the wearer's hips/panty line, leaving just a sideways C shaped piece between the legs. |

|

Tanga

|

Cheeky | A type of thong which is wider than a G-string and fairly wide in the front, more like the wide V of a traditional brief. Fit tends to be more comfortable than that of a plain thong or G-string and is often more embellished. |

|

Thong

|

|

Has a narrow strip of material along the centre of the garment's rear which sits between the wearer's buttocks and connects the front or pouch to the waistband behind the wearer. Thongs are sometimes worn to reduce "panty lines" when wearing tightly fitting trousers. |

|

T-front

|

|

Has a narrow piece of cloth passing between the buttocks and the labia and only widening above the clitoris. It provides no coverage while still maintaining the basic hygienic underwear functions. |

|

| Worn by women | |||

| Upper body | |||

Bra

|

|

Usually consists of two cups for the breasts, a centre panel (gore), a band running around the torso under the bust, and a shoulder strap for each side. |

|

| Lower body | |||

Boy shorts

|

booty shorts, boyleg briefs, boy short panties, boys' cut shorts, boyshorts, hipsters, shorties | A type of panties with sides that extend lower down the hips, similar to men's trunk briefs. |

|

Tap pants

|

side-cut shorts, dance shorts, French knickers | A form of lingerie that covers the pelvic area and the upper part of the upper legs. |

|

Panties

|

briefs, classic briefs

UK: knickers |

These usually have an elastic waistband, a crotch to cover the genital area which is usually lined with absorbent material such as cotton, and a pair of leg openings which are often also elasticized. They either have very short or no leg sections. |

|

| Worn by men | |||

| Lower body | |||

Boxer briefs

|

UK: trunks | These are similar in style to boxer shorts, but are form-fitting like briefs. |

|

Trunks

|

trunk briefs, short-leg boxer briefs | These are similar in style to boxer briefs, but shorter in the inseam. |

|

| Midway briefs |

midways, long-leg boxer briefs | These are similar in style to boxer briefs, while being longer in the legs, to near or up to the knees. |

|

Boxer shorts

|

boxers

UK: trunks |

These have an elasticized waistband that is at or near the wearer's

waist, while the leg sections are fairly loose and extend to the

mid-thigh. There is usually a fly, either with or without buttons. The waistbands of boxer shorts are usually wider than those of any type of briefs. Boxer shorts with colorful patterns, pictures of cartoon characters, sports team logos, and slogans are readily available. |

|

Briefs

|

classic briefs

UK: Y-fronts US: tighty-whiteys (slang), jockey shorts, jockeys Australia: jocks (slang) |

These have an elasticized waistband at or near the wearer's waist, and leg bands that end at or near the groin. |

|

Jockstrap

|

athletic supporter, jock, nut cup (slang), strap, supporter | Consists of an elastic waistband with a support pouch for the genitalia and two elastic straps affixed to the base of the pouch and to the left and right sides of the waistband at the hip. In some varieties, the pouch may be fitted with a pocket to hold an impact-resistant cup to protect the genitals from injury. A jockstrap is different from a dance belt that a male dancer wears. |

|

| Religious Under Clothing | |||

| Whole body | |||

Temple garments

|

|

This kind of underwear is worn by Mormons. |

|

| Upper body | |||

| Tallit katan |

|

|

|

| Lower body | |||

Kacchera

|

|

|

|

Industry

Market

In January 2008 it was reported that, according to market research firm Mintel, the men's underwear market in the UK was worth £674 million, and volume sales of men's underpants rose by 24% between 2000 and 2005. British manufacturers and retailers claim that most British men prefer "trunks", or short boxer briefs. The director of menswear of major British retailer Marks & Spencer (M&S), which sells 40 million pairs of men's underpants a year, was quoted as saying that while boxer shorts were still the most popular at M&S, demand was easing off in favor of hipster trunks similar in design to the swimming trunks worn by actor Daniel Craig in the James Bond film Casino Royale (2006).[5]

In 1985, Fruit of the Loom, Hanes, and Jockey International had the largest shares of the U.S. men's underwear market; these companies had about 35%, 15%, and 10% of the market, respectively.[31]

Gregory Woods, author of "We're Here, We're Queer and We're not Going Catalogue Shopping", stated that in companies often do not market men's underwear to straight men on the assumption that they are not interested in buying underwear for themselves; therefore many such advertisements are catered to women to convince them to buy underwear for their husbands, as well as to gay or bisexual men.[32] In 1985 Jockey International president Howard Cooley stated that women often shop more than men do, and men request women to buy underwear for them.[31] According to multiple studies conducted c. 1985, 60-80% of men's undergarments for sale had been purchased by women.[31]

Designers and retailers

A number of major designer labels are renowned for their underwear collections, including Calvin Klein, Dolce & Gabbana, and La Perla. Likewise, specialist underwear brands are constantly emerging, such as Andrew Christian, 2(x)ist, Leonisa, and Papi.

Specialist retailers of underwear include high street stores La Senza (Canada), Agent Provocateur (UK), Victoria's Secret (U.S.), and GapBody, the lingerie division of the Gap established in 1998 (U.S.). In 2000, the online retailer, Freshpair, started in New York and in 2008 Abercrombie & Fitch opened a new chain of stores, Gilly Hicks, to compete with other underwear retailers.

The 2014 Stockholm Skateathon was sponsored by Björn Borg and the advertising campaign encouraged participants either skateboarding or longboarding, for example, to wear undergarments, and whilst it received criticism by the skateboarders, some people ended up dressing in the undergarments [33]

Not wearing undergarments

Going without lower body undergarments has come to be known by the slang term going commando, as well as sometimes free-balling or free-buffing (referencing testicles and the vulva respectively).[34]

The origins of the phrase go commando are uncertain, with some speculating that it may refer to being "out in the open" or "ready for action".[35] The modern usage may be traced in the United States to university students c. 1974, where it was perhaps associated with soldiers in the Vietnam War, who were reputed to go without underwear to "increase ventilation and reduce moisture".[36] The phrase was in use in the UK before then, referring mainly to women, from the late 1960s.[34] The connection to the UK and women has been suggested to link to a World War II euphemism for prostitutes working in London's West End, who were termed "Piccadilly Commandos".[37][38] The term was re-popularized after it appeared in a 1996 episode of Friends, where Joey Tribbiani wears everything Chandler Bing owns in an act of revenge, while also going "commando".[39][40]

In a 2014 open-access internet-based poll, 60 Minutes and Vanity Fair asked visitors to their websites the question "How often do you 'go commando'?" A quarter of participants said that they did this at least occasionally, while 39% said they never did so, and 35% said that they did not know the meaning of the term.[41][42]

See also

- Corset controversy

- Diaper

- Hosiery

- Ring, slide and hook

- Social aspects of clothing

- Swimsuit

- Trousers – Law – laws on underwear exposure

- Underwear as outerwear

- Underwear Museum - A museum in Lessines, Belgium, and previously in Brussels, displaying undergarments of famous persons

References

Notes

{{cite web}}: |last= has generic name (help); External link in |last= and |website=It's during the Vietnamese war, that the earliest cases of going without underwear were recorded. It meant ... being 'out in the open' or 'ready for action'.

[T]he episode also introduced the term 'going commando' into the popular vernacular.

To answer the questions yourself, visit the 60 Minutes homepage at CBSNews.com.

Further reading

- Benson, Elaine; John Esten (1996). Unmentionables: A Brief History of Underwear. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Cunnington, C[ecil] Willett; Phillis Cunnington (1992). The History of Underclothes. New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-27124-2. First published in London by Michael Joseph in 1951.

- Hawthorne, Rosemary (1993). Stockings & Suspenders: A Quick Flash. Lucy Pettifer & Claire Taylor (ill.). London: Souvenir. ISBN 0-285-63143-8.

- Martin, Richard [Harrison]; Harold Koda (1993). Infra-apparel. photographs by Neil Selkirk. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 0-8109-6430-9.

External links

- Historical Lingerie pictures from the New York Public Library Picture Collection Archived 9 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- Handmade women's underwear set, 1911, in the Staten Island Historical Society Online Collections Database.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Underwear

Long underwear, also called long johns or thermal underwear, is a style of two-piece underwear with long legs and long sleeves that is normally worn during cold weather. It is commonly worn by people under their clothes in cold countries.

In the United States, it is usually made from a cotton or cotton-polyester-blend fabric with a waffle weave texture, although some varieties are also made from flannel, particularly the union suit, while many newer varieties are made from polyester, such as the Capilene trade name.[citation needed]

European manufacturers use wool blends or even 100% wool, usually Merino or other high-quality wool.[citation needed] Some models might include a thin layer of polyester to transport moisture away from the skin. Wool, in addition to being fire retardant, provides highly effective insulation and will keep its insulating properties even when wet, as opposed to cotton.

The type known as "thermal underwear" is made from two-ply fabric of either a wool layer and an artificial fibre, only wool or – again mostly in the U.S. – two layers of only artificial fibres, which uses trapped body heat to insulate against cold air.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Long_underwear

Etymology of long johns

The manufacturing foundations of long johns may lie in Derbyshire, England, at John Smedley's Lea Mills, located in Matlock. The company has a 225-year heritage and is said to have created the garment, reputedly named after the late-19th-century heavyweight boxer John L. Sullivan; the company still produces long johns.[1]

In 2004, Michael Quinion, a British etymologist and writer, postulated that the john in the item of apparel may be a reference to Sullivan, who wore a similar-looking garment in the ring. This explanation, however, is uncertain and the term's origin is ultimately unknown.[2]

It has also been posed that the term is an approximation of the French longues jambes, which translates to 'long legs.'

History of long johns

Long johns were first introduced into England in the 17th century, but they did not become popular as sleepwear until the 18th century. They were first used as loungewear but then later became popular in Truro, Nova Scotia. In 1898, Myles and his brother John had developed a product called Stanfield's Unshrinkable Underwear for their garment manufacturing company.

Long johns first appeared in North America when Frank Stanfield, a Canadian, applied for the first patent for the long johns design. He and his brother started with non-shrinking cotton underwear and formally applied for a patent for long johns on December 7, 1915, becoming the pioneer of long johns.[citation needed]

From 1914 to mid-1918, the item of underwear most purchased by various military forces was a garment known as a union suit; it is a one-piece form of underwear covering body and legs and was the prototype of the Chinese qiuyi (秋衣), the top part, and qiuku (秋裤), the bottom part.

After 1918, countries returned to producing more and more daily usages.[clarification needed] The Industrial Revolution progressed in accordance with the concept of the assembly line and division of labor. Manual laborers who were physically active were divided into laborers who performed more upper-body activity and laborers with more lower-body activity. It then became more and more obvious that qiuyi and qiuku as separate parts was better than a one-piece garment.[citation needed]

In 1940, the United States did not have today's indoor heating solutions; many people used stoves to heat rooms in winter. At that time, one not only had to wear long underwear or the union suit but also a nightcap when going to bed, and the frequency of bathing was far less than the current time.[citation needed]

During the US-Soviet Kitchen Debate in 1959, Khrushchev questioned the technological level of Nixon's "typical American housing" – judging from the historical reference to long pants, the appliances displayed in the United States may have been more advanced.[relevant?]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Long_underwear

underclothes

English

Alternative forms

Etymology

Noun

underclothes pl (plural only)

Synonyms

Coordinate terms

Related terms

Translations

See also

https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/underclothes

U.S. Navy divers in contamination dry suits preparing to dive | |

| Uses | Environmental protection of underwater divers, boaters and other people who may be immersed in water. |

|---|---|

| Inventor | Augustus Siebe (1837)[1]: Ch1 |

| Related items | Diving suit, Wetsuit, Survival suit |

A dry suit or drysuit provides the wearer with environmental protection by way of thermal insulation and exclusion of water,[2][3][4][5] and is worn by divers, boaters, water sports enthusiasts, and others who work or play in or near cold or contaminated water. A dry suit normally protects the whole body except the head, hands, and possibly the feet. In hazmat configurations, however, all of these are covered as well.[6]

The main difference between dry suits and wetsuits is that dry suits are designed to prevent water from entering. This generally allows better insulation, making them more suitable for use in cold water. Dry suits can be uncomfortably hot in warm or hot air, and are typically more expensive and more complex to don. For divers, they add some degree of operational complexity and hazard as the suit must be inflated and deflated with changes in depth in order to minimize "squeeze" on descent or uncontrolled rapid ascent due to excessive buoyancy, which requires additional skills for safe use.[7] Dry suits provide passive thermal protection: Undergarments are worn for thermal insulation against heat transfer to the environment and chosen to suit expected conditions.[7] When this is insufficient, active warming or cooling may be provided by chemical or electrically powered heating accessories.[1]: Ch1

The essential components are the waterproof shell, the seals, and the watertight entry closure.[1] A number of accessories are commonly fitted, particularly to dry suits used for diving, for safety, comfort and convenience of use. Gas inflation and exhaust equipment are generally used for diving applications, primarily for maintaining the thermal insulation of the undergarments, but also for buoyancy control and to prevent squeeze.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dry_suit

A petticoat or underskirt is an article of clothing, a type of undergarment worn under a skirt or a dress. Its precise meaning varies over centuries and between countries.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, in current British English, a petticoat is "a light loose undergarment ... hanging from the shoulders or waist". In modern American usage, "petticoat" refers only to a garment hanging from the waist. They are most often made of cotton, silk or tulle. Without petticoats, skirts of the 1850s would not have the volume they were known for.[1] In historical contexts (16th to mid-19th centuries), petticoat refers to any separate skirt worn with a gown, bedgown, bodice or jacket; these petticoats are not, strictly speaking, underwear, as they were made to be seen. In both historical and modern contexts, petticoat refers to skirt-like undergarments worn for warmth or to give the skirt or dress the desired attractive shape.

Terminology

Sometimes a petticoat may be called a waist slip or underskirt (UK) or half slip (US), with petticoat restricted to extremely full garments. A chemise hangs from the shoulders. Petticoat can also refer to a full-length slip in the UK,[2] although this usage is somewhat old-fashioned.

History

In the 14th century, both men and women wore undercoats called "petticotes".[3] The word "petticoat" came from Middle English pety cote[4] or pety coote,[5] meaning "a small coat/cote".[6] Petticoat is also sometimes spelled "petty coat".[7] The original petticoat was meant to be seen and was worn with an open gown.[3] The practice of wearing petticoats as undergarments was well established in England by 1585.[8] In French, petticoats were called jupe.[9] The basquina, worn in Spain, was considered a type of petticoat.[10]

The petticoat in western men’s dress, what would become known in later years develop into the waistcoat, was from the mid-15th century to around the 17th century an under-doublet.[11] The garment was worn in cooler months under a shirt for warmth, and was usually padded or quilted.[11]

In the 18th century in Europe and in America, petticoats were an integral component of a gown, considered a part of the exterior garment and were meant to be seen.[9] The term petticoat was used to refer to such an outer skirt from the 16th to the 19th century, which were fashioned from either matching or contrasting textiles, in simple fabrics, or were highly decoratively embroidered.[11] An underpetticoat was considered an undergarment and was shorter than a regular petticoat.[9] Underpetticoats were also known as a dickey.[12] Also in the American colonies, working women wore shortgowns (bedgowns) over petticoats that normally matched in color.[13] The hem length of a petticoat in the 18th century depended on what was fashionable in dress at the time.[14] Often, petticoats had slits or holes for women to reach pockets inside.[14] Petticoats were worn by all classes of women throughout the 18th century.[15] The style known as polonaise revealed much of the petticoat intentionally.[12]

In the early 19th century, dresses became narrower and simpler with much less lingerie, including "invisible petticoats".[16] Then, as the waltz became popular in the 1820s, full-skirted gowns with petticoats were revived in Europe and the United States.

In the Victorian era, petticoats were cemented as undergarments, used to give bulk and shape to the skirts worn over the petticoat.[12] By the mid 19th century, petticoats were worn over hoops also known as crinoline.[12] Popular white cotton petticoats as an undergarment in this 1860s, for example, regularly featured a lace and broderie anglaise decorative border.[11] As the bustle became popular in the 1870s, petticoats developed flounces towards the back in order to cater for this style of under structure.[17] Petticoats also continued to be worn in layers through this decade.[18] Coloured petticoats came into fashion by the 1890s,[17] with many being made from silk and featuring decorative frills to the bottom edge.[11]

In the early 20th century, petticoats were circular, had flounces and buttons, in which women could attach additional flounces to the garment.[19] Bloomers were also touted as a replacement for petticoats when working and by fashion reformers.[20][21]

After World War I, silk petticoats were in fashion.[12]

Petticoats were revived by Christian Dior in his full-skirted "New Look" of 1947, and tiered, ruffled, stiffened petticoats remained extremely popular during the 1950s and 1960s.[12] These were sold in a few clothing stores as late as 1970.

Sybil Connolly recalled how a red flannel petticoat, worn by a Connemara woman, inspired her first international fashion collection which took place in New York in 1953.[22][23] She had travelled to Connemara for inspiration, where she saw a woman wearing a traditional red flannel petticoat. She bought a bolt of the same fabric from the local shop and made it into a quilted evening skirt, which was a huge success at the fashion show.[23] One of these skirts is part of the collection at The Hunt Museum.

Non-Western petticoats

Underskirts worn under non-Western clothing, such as the ghagra worn under a sari, are also often called petticoats. Sari petticoats usually match the color of the sari and are made of satin or cotton.[24] Compared to the Western petticoat, South Asian petticoats are rarely shorter than ankle length and are always worn from the waist down. They may also be called inner skirts[25] or inskirts.

In Japan, similar to a petticoat, a nagajuban (commonly referred to simply as a juban; a hadajuban is sometimes worn underneath a nagajuban) are worn under the kimono as a form of underwear similar in function to the petticoat. The juban resembles a shorter kimono, typically without two half-size front panels (the okumi) and with sleeves only marginally sewn up along the wrist-end. Juban are commonly made of white silk, though historically were typically made of red silk; as the collar of the juban shows underneath the kimono and is worn against the skin, a half-collar (a han'eri) is often sewn to the collar as a protector, and also for decoration. The hadajuban is sometimes worn underneath the juban, and resembles a tube-sleeved kimono-shaped top, without a collar, and an accompanying skirt slip.

In popular culture

The early feminist Mary Wollstonecraft was disparaged by Horace Walpole as a "hyena in petticoats".[26] Florentia Sale was dubbed "the Grenadier in Petticoats"[27] for travelling with her military husband Sir Robert Henry Sale around the British Empire.

The phrase "petticoat government" has referred to women running government or domestic affairs.[28] The phrase is usually applied in a positive tone welcoming female governance of society and home, but occasionally is used to imply a threat to "appropriate" government by males, as was mentioned in several of Henry Fielding's plays.[29] An Irish pamphlet Petticoat Government, Exemplified in a Late Case in Ireland was published in 1780.[30] The American writer Washington Irving used the phrase in Rip Van Winkle (1819).[31] Frances Trollope wrote Petticoat Government: A Novel in 1850.[32] Emma Orczy wrote Petticoat Government, another novel, in 1911. G. K. Chesterton (1874–1936) mentions petticoat in a positive manner; to the idea of female dignity and power in his book What's Wrong With the World (1910) he states:[33]

It is quite certain that the skirt means female dignity, not female submission; it can be proved by the simplest of all tests. No ruler would deliberately dress up in the recognized fetters of a slave; no judge would appear covered with broad arrows. But when men wish to be safely impressive, as judges, priests or kings, they do wear skirts, the long, trailing robes of female dignity. The whole world is under petticoat government; for even men wear petticoats when they wish to govern.

President Andrew Jackson's administration was beset by a scandal called the "Petticoat affair", dramatized in the 1936 film The Gorgeous Hussy. A 1943 comedy film called Petticoat Larceny (cf. petty larceny) depicted a young girl being kidnapped by grifters. In 1955, Iron Curtain politics were satirized in a Bob Hope and Katharine Hepburn film The Iron Petticoat. In the same year Western author Chester William Harrison wrote a short story "Petticoat Brigade" that was turned into the film The Guns of Fort Petticoat in 1957. Blake Edwards filmed a story of an American submarine filled with nurses from the Battle of the Philippines called Operation Petticoat (1959). Petticoat Junction was a CBS TV series that aired in 1963.[34] CBS had another series in the 1966–67 season called Pistols 'n' Petticoats.[35]

See also

- Breeching (boys), a historical practice involving the change of dress from petticoat-like garments to trouser-like ones

- Crinolines and hoop skirts, stiff petticoats made of sturdy material used to extend skirts into a fashionable shape

- Peshgeer

References

Citations

- Du Brow, Rick (1965-12-04). "Television in Review". The Tipton Daily Tribune. p. 2. Retrieved 2018-01-26 – via Newspapers.com.

Sources

- Baumgarten, Linda (2002). What Clothes Reveal: The Language of Clothing in Colonial and Federal America. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300095807.

- Cunningham, Patricia A. (2003). Reforming Women's Fashion, 1850-1920: Politics, Health and Art. Kent, Ohio: The Kent State University Press. ISBN 0873387422.

- Cunnington, C. Willett; Cunnington, Phillis (1992). The History of Underclothes (New ed.). Dover. ISBN 9780486271248.

- Higgins, Padhraig (2010). A Nation of Politicians: Gender, Patriotism, and Political Culture in Late Eighteenth-Century Ireland. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 9780299233334 – via Project MUSE.

- Picken, Mary Brooks (1957). The Fashion Dictionary: Fabric, Sewing, and Dress as Expressed in the Language of Fashion. New York: Funk & Wagnalls Company.

- Sholtz, Mackenzie Anderson (2016). "Petticoat, 1715-1785". In Blanco, Jose; Doering, Mary D. (eds.). Clothing and Fashion: American Fashion from Head to Toe. Vol. 1. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781610693103.

External links

- Quilted Petticoat, 1750-1790, in the Staten Island Historical Society Online Collections Database

- Petticoat-Government in a Letter to the Court Lords (1702)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Petticoat

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:1950s_fashion

Pantyhose, sometimes also called sheer tights, are close-fitting legwear covering the wearer's body from the waist to the toes. Pantyhose first appeared on store shelves in 1959 for the advertisement of new design panties (Allen Gant's product, 'Panti-Legs')[1] as a convenient alternative to stockings and/or control panties which, in turn, replaced girdles.

Like stockings or knee highs, pantyhose are usually made of nylon, or of other fibers blended with nylon. Pantyhose are designed to:

- Be attractive in appearance,

- Hide physical features such as blemishes, bruises, scars, hair, spider veins, or varicose veins,

- Reduce visible panty lines,[2] and

- Ease chafing between feet and footwear, or between thighs.

Besides being worn as fashion, in Western society pantyhose are sometimes worn by women as part of formal dress. Also, the dress code of some companies and schools may require pantyhose or fashion tights to be worn when skirts or shorts are worn as part of a uniform. Men also can wear them under trousers or shorts either for work wear or leisure.

Terminology

The term "pantyhose" originated in the United States[3] and rid the combination of panties (an American English term) with sheer nylon hosiery. In British English, these garments are called "sheer tights". The term tights alone refers to all such garments regardless of whether they are sheer lingerie or sturdy outerwear.

In American English, the term "tights" typically refers to pantyhose-like garments made from thicker material, which are generally opaque or slightly translucent. Opaque leg wear made of material such as spandex are often worn by both sexes for athletic activities or as utility clothing, and are usually referred to as "leggings", a term that includes casual wear. The primary difference between tights and leggings is that leggings can be worn as outerwear, whereas tights are not. In most cases, leggings will have a seam on the inside of the leg, whereas the legs of tights will be seamless. Leggings will often be footless, whereas tights usually will not.

History

The history of pantyhose, as for stockings, is tied to that of changes in styles of women's hemlines. Before the 1920s, it was generally expected that women would cover their legs in public, including their ankles; and dress and skirt hemlines were generally to the ground. The main exceptions were in sports and entertainment, making tights a more suitable choice.[4] In cases of high cut legs or fabrics that would produce a visible panty line, it was a practical necessity to wear them as the only lower undergarment. In the 1920s, fashionable hemlines for women began to rise, exposing the legs to just below the knees. Stockings also came into vogue to maintain leg coverage, as well as some level of warmth. The most popular stockings were sheer hosiery which were first made of silk or rayon (then known as "artificial silk"), and, after 1940, made of nylon, which had been invented by DuPont in 1938. During the 1940s and 1950s, stage and film producers would sew stockings to the briefs of their actresses and dancers, as testified to by singer-actress-dancer Ann Miller.[5][6] These garments were seen in popular motion pictures such as Daddy Long Legs.

In 1953, Allen Gant Sr. of Glen Raven Knitting Mills developed a commercial equivalent to these hose that he named "Panti-Legs", but these were not brought to the open market until about 1959.[7] During this time, Ernest G. Rice invented his own design for pantyhose similar to those worn today, and in 1956 he submitted a patent titled "Combination Stockings and Panty".[8] This design was adopted by other makers, and this caused disputes in U.S. courts for many years before the patent was upheld some time after Rice's own death.[9] In 1974, actress Julie Newmar successfully filed a patent for “Pantyhose with shaping band for cheeky derriere relief”, a garment innovation made famous through the costume she designed in the 1960s for her role as Catwoman in the TV show Batman.

Up until this time, there was little reason for women outside show business to wear "panty hose", as the longer hemlines allowed for the use of over-the-knee stockings secured with a garter belt. Nonetheless, during the 1960s, improved textile manufacturing processes made pantyhose increasingly more affordable, while human-made textiles such as spandex (or elastane) made them more comfortable and durable. The advent of the fashionable miniskirt, which exposed the legs to well above the knee, made pantyhose a necessity to many women. In 1970, U.S. sales of pantyhose exceeded stockings for the first time, and it has remained so ever since.[10] Pantyhose became a wardrobe staple throughout the 1970s and 1980s.

From 1995 a steady decline began, leveling off in 2006 with U.S. sales less than half of what they had once been. This decline has been attributed to bare legs in fashion, changes in workplace dress code, and the increased popularity of trousers.[11]

While sales of traditional styles did not recover, the 2000s saw the rise of other specific styles. Fishnet hose, patterns and colors, opaque tights, low-rise pantyhose, footless shapewear, and pantyhose for men (playfully referred to as "mantyhose") all experienced increased sales. In the 2010s, an increasing popularity for form-fitting opaque leggings paired with casual dress (and even some officewear) supplanted the fashion role previously held by pantyhose, although pantyhose remain popular as part of formalwear.[12][13]

Composition

Pantyhose generally have a standard construction: the top of the waist is a strong elastic; the part covering the hips and the buttocks (the panty area) is composed of a thicker material than for the legs. The gusset or crotch covering the genitalia is a stronger material, sometimes made of porous cotton, but the legs of the pantyhose are made of the thinnest usable fabrics, and it has a consistent construction down to the wearer's toes. These can be reinforced to guard against wear and tear.[14]

Most pantyhose are composed of nylon and a mixture of spandex, which provides the elasticity and form-fitting that is characteristic of modern pantyhose. The nylon fabric is somewhat prone to tearing ("running"), and it is common for very sheer hose to "run" soon after snagging on anything that is rough or sharp.[14]

Variations in pantyhose construction exist, such as with fishnet pantyhose. Pantyhose may be composed of other materials such as silk, cotton, cashmere or wool.

Styles

Pantyhose are available in a wide range of styles. The sheerness of the garment, expressed as a numerical "denier"/'dtex", ranges from 3 (extremely rare, very thin, barely visible) up to 20 (standard sheer), 30 (semi opaque) up to 250 (opaque). The term denier is often referred to the weight of the yarn that was used to produce the item of hosiery. A higher denier of yarn results in a thicker pair of tights.

Control-top pantyhose, intended to boost a slimmer figure, has a reinforced-panty section. The panty section may be visible when wearing short skirts or shorts.

Sheer-to-waist pantyhose is sheer throughout, with the panty portion being the same thickness and color as the leg portion, and are designed for use with high-slit gowns, miniskirts, hot pants, or lingerie. Often sheer-to-waist pantyhose will be reinforced along and on either side of the seam in the middle of the panty. Often sheer-to-waist pantyhose comes with sandal toes - invisibly reinforced toes part.

Open toe pantyhose starts from the waist and ends just before the toes, leaving toes free, which allows legs to be covered with the tights, but toes to be shown in sandals or peep toe shoes.

Open-crotch pantyhose, sometimes known as crotchless pantyhose, do not have a gusset. Instead, an opening is in place for hygiene or sexual-fetishism activities.

Some pantyhose have single- or double-panel gussets incorporated into them. In single-panel, there are two seams instead of the usual one, with a single seam on the opposite side; with double-panel gussets, there are two seams on either side.

Concerns

The disadvantages of pantyhose includes:

- Unlike cotton, nylon is not an absorbent material. As a result, perspiration is more likely to remain in contact with the feet, legs and genital area, thereby encouraging bacterial growth and associated odor. Some hosiery products contain silver to help prevent odor and sweating of the feet, thus making the wearing of hosiery a more pleasant experience. Wearing natural fiber silk stockings and tights is another means of reducing perspiration.

- Some women do not wear pantyhose for environmental reasons, noting that they usually cannot be recycled, and nylon pantyhose are not biodegradable. Disposing of the item contributes to overuse of landfill. Burning nylon pantyhose sometimes releases toxins into the atmosphere.

This used to be the case but in the UK, local authorities accept clean, dry textiles along with other recyclables. This is both at recycling centres and curb-side collections. Textiles (including tights, pantyhose and stockings) which cannot be re-worn are recycled and turned into things like roofing felt. There are several internet sites which explain ways of reusing pantyhose (laddered or otherwise). In the US, nylon stockings, tights, and pantyhose can be sent to Recycled Crafts to be used in craft projects like pet toys, rugs, placemats, and table runners.[15] Swedish Stockings, maker of hosiery, has a program to grind down old pantyhose for use in oil and grease traps.[16] In the past, hosiery manufacturer No Nonsense had a recycling program,[17] and so did Matter of Trust.[18]

- Pantyhose have been criticized for being flimsy because the thin knit fabric is prone to tearing or laddering (or "running").[11] The wearer can cause a run in the hose by catching a toenail in the fabric when the hose is put on, by catching it on a rough surface like a corner of a desk, or a car, and by numerous other risks. Some women apply clear nail polish or hair spray to their hose to prevent runs from growing. Some of brands offer "ladder-resist" pantyhose which are more durable than regular ones.

Use by men

While usually considered to be a woman's garment, pantyhose can also be worn by men, for example for thermal protection, therapeutic relief or simply as a lifestyle choice. Race horse jockeys may wear pantyhose under their uniform to enable them to glide freely over the legs and waist when the jockey's body moves at a rapid pace.[19] Some fishermen who surf fish from tropical beaches may wear pantyhose for protection from jellyfish whose stingers are triggered by contact with a chemical on bare skin.[20][21][22] In the late 1990s, several manufacturers introduced pantyhose styles designed for men to cater to this niche market.[23][24]

Gallery

-

A man wearing mantyhose (pantyhose designed specifically for men)

-

Girl wearing pantyhose and a polkadot dress

-

Example of a "run" or "ladder"

-

Image of a woman with her legs and pantyhose posing erotically, an example of tights fetishism.

See also

References

Pantyhose can feel like a tourniquet, and once a pair gets a snag, it usually has to be tossed. Going without discomfort costing from a few dollars to more than $40 a pair was a trend many women were happy to embrace.

It is one of the curiosities of racing that, to a man, jockeys go out to ride wearing that most feminine of undergarments; ladies nylon tights.

- "Tights Frame of Mind - A Pantyhose Podcast - YouTube". www.youtube.com. Retrieved 27 July 2023.

External links

- How It's Made: Pantyhose YouTube video

- Hosiery Glossary - Specialistic glossary in English

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pantyhose

A regular haircut, in Western fashion, is a men's and boys' hairstyle that has hair long enough to comb on top, a defined or deconstructed side part, and a short, semi-short, medium, long, or extra long back and sides.[1]: 129–131 [2]: 98–101 The style is also known by other names including taper cut, regular taper cut, side-part and standard haircut; as well as short back and sides, business-man cut and professional cut, subject to varying national, regional, and local interpretations of the specific taper for the back and sides.[3]: 188 [1]: 122 [4][2]: 97 [5][6][7]

Origins

The short back and sides dates back to the Roman empire, as the regulation haircut for legionaries. Besides preventing the spread of lice, short hair and a clean shaven face prevented the enemy from grabbing a soldier by the beard. By the first century AD, Roman hairstyles were imitated by non-Roman subjects who admired the civilisation that Rome brought. Examples include the Gallo-Romans and Romanized Jews like Saint Paul seeking to distinguish themselves from traditionalists for whom hair cutting was forbidden.

The regular haircut, worn with a long beard, made a comeback during the Renaissance due to European men's newfound fascination with rediscovered classical Greco-Roman artefacts. It was revived for a second time during the Regency era of c.1810-1830 as dandies abandoned the impractical and expensive powdered wigs in response to William Pitt the Younger's hair powder tax.

During the Gay Nineties, the regular haircut gradually replaced the longer hair and muttonchop sideburns fashionable since the 1840s until, by 1910, it had become the norm for professional men. An extreme version known as the undercut was regulation for British and German soldiers during World War I and World War II.[8] During the post-World War II period, the business-man haircut, in the form of a combover, became the standard dress code for men's hair in white-collar workplace settings throughout the Western world until the late 1960s and early 1970s. In 2010s fashion, the short back and sides continued to be worn by many professional men, while the related undercut[9] was appropriated by the hipster subculture.[10]

Elements

The essential elements of a regular haircut are edging, siding and topping:[1]: 118 [2]: 61–62

- Edging refers to the design of the lower edge of hair growth from the sideburns around the ears and across the nape of the neck.[1]: 118 [2]: 62–63

- Siding refers to the design of the hair on the back and sides between the edge and the top.[1]: 118 [2]: 68 Edging and siding, together or separately, commonly referred to as tapering, create a taper (see crew cut).[2]: 68

- Topping refers to the design of the hair at the front and over the crown.[1]: 118 [2]: 70

Edging comes first, followed by siding and topping.[1]: 118 [2]: 61 Edging is typically done with clippers; siding, shears over comb; topping, shears over finger.[2]: 62–63 [1]: 118–120 There are other methods that can be used including all clipper cuts, all shears cuts and all razor cuts. Barbers distinguish between a two line haircut and a one line haircut.[1]: 133–134 [2]: 97 Two line haircuts are standard taper cuts. The hair is outlined around the ears and then straight down the sides of the neck.[1]: 113–115 [2]: 97 The edge of hair growth at the nape of the neck is tapered to the skin with a fine(zero) clipper blade.[1]: 103 [2]: 110–111 A one line haircut, often referred to as a block cut, has the edge of hair growth at the nape outline shaved, creating an immediate transition between hair and skin and connecting the outline from the right sideburn to the outline from the left sideburn across the nape.[1]: 115 [2]: 97 The outline at the edge of the nape can be in a squared off or rounded pattern. A squared off nape can have squared or rounded corners.[1]: 115 [2]: 97 [11]: 90 Rotary, taper and edger clippers can be used when edging or siding a haircut. Guards and/or blades can be attached that vary the cutting length.[1]: 54

Tapers

A tapered back and sides generally contours to the head shape; the hair progressively graduates in length from longer hair at the upper portions of the head to shorter hair at the lower edge of hair growth on the back and sides.[3]: 259 There are a variety of tapers possible from short to extra long.[1]: 129–131 [2]: 98–101 Medium and longer tapers can be referred to as trims; however, the word trim is commonly used to request that the hair is trimmed back to the last haircut regardless of the style of taper.[1]: 131 [2]: 96 The sideburns and the shape and height of the neck edge are important design elements that can affect the appearance of the face, neck, chin, ears, profile and overall style.

In most instances, a shorter neck or chin suits a somewhat higher neck edge; a longer neck or chin suits a somewhat lower neck edge. An extra wide neck suits a somewhat narrower neck edge while a thinner neck or protruding ears suit a wider neck edge.[2]: 132–137 When slightly longer sideburns are worn than are appropriate for a style, it can shorten the appearance of the face; when slightly shorter sideburns are worn than are appropriate, it can lengthen the appearance of the face; therefore, the appearance of a face that is shorter or longer than average, in particular when due to the length of the chin or lower face, can be normalized by altering the length of the sideburns.[1]: 128, 131 [2]: 89–90, 135–136

Short

Other names for this style of taper include full crown, tight cut, and fade.[12][13]: 50 [14]: 40–43 [11]: 41–45, 100 [3]: 282 [15]: 133 The hair on the sides and back is cut with a coarse clipper blade from the lower edge of hair growth to or nearly full up to the crown. The clipper is gradually arced out of the hair at the hat band to achieve a taper. A fine clipper is used from the sideburn to about an inch above the ear. Clipper lines are blended out so there is a seamless transition between lengths.[11]: 100–103 [15]: 129 [2]: 98