Equine anatomy encompasses the gross and microscopic anatomy of horses, ponies and other equids, including donkeys, mules and zebras. While all anatomical features of equids are described in the same terms as for other animals by the International Committee on Veterinary Gross Anatomical Nomenclature in the book Nomina Anatomica Veterinaria, there are many horse-specific colloquial terms used by equestrians.

Reproductive system[edit]

Mare[edit]

The mare's reproductive system is responsible for controlling gestation, birth, and lactation, as well as her estrous cycle and mating behavior. It lies ventral to the 4th or 5th lumbar vertebrae, although its position within the mare can vary depending on the movement of the intestines and distention of the bladder.

The mare has two ovaries, usually 7 to 8 cm (2.8 to 3.1 in) in length and 3 to 4 cm (1.2 to 1.6 in) thick, that generally tend to decrease in size as the mare ages. In equine ovaries, unlike in humans, the vascular tissue is cortical to follicular tissue, so ovulation can only occur at an ovulation fossa near the infundibulum. The ovaries connect to the fallopian tubes (oviducts), which serve to move the ovum from the ovary to the uterus. To do so, the oviducts are lined with a layer of cilia, which produce a current that flows toward the uterus. Each oviduct attaches to one of the two horns of the uterus, which are approximately 20 to 25 cm (7.9 to 9.8 in) in length. These horns attach to the body of the uterus (18 to 20 cm [7.1 to 7.9 in] long). The equine uterus is bipartite, meaning the two uterine horns fuse into a relatively large uterine body (resembling a shortened bicornuate uterus or a stretched simplex uterus). Caudal to the uterus is the cervix, about 5 to 7 cm (2.0 to 2.8 in) long, which separates the uterus from the vagina. Usually 3.5 to 4 cm (1.4 to 1.6 in) in diameter with longitudinal folds on the interior surface, it can expand to allow the passage of the foal. The vagina of the mare is 15 to 20 cm (5.9 to 7.9 in) long, and is quite elastic, allowing it to expand.[citation needed] The vulva is the external opening of the vagina, and consists of the clitoris and two labia. It lies ventral to the rectum.[18][19] The mare has two mammary glands, which are smaller in maiden mares. They have two ducts each, which open externally.[citation needed]

Stallion[edit]

The stallion's reproductive system is responsible for his sexual behavior and secondary sex characteristics (such as a large crest). The external genitalia include the urethra; the testes, which average 8 to 12 cm (3.1 to 4.7 in) long; the penis, which, when housed within the prepuce, is 50 cm (20 in) long and 2.5 to 6 cm (0.98 to 2.36 in) in diameter with the distal end 15 to 20 cm (5.9 to 7.9 in) and when erect, increases by 3 to 4 times. The internal genitalia accessory sex glands are the vesicular glands, prostate gland, and bulbourethral glands, which contribute fluid to the semen at ejaculation, but are not strictly necessary for fertility.[20]

Teeth[edit]

A horse's teeth include incisors, premolars, molars, and sometimes canine teeth. A horse's incisors, premolars, and molars, once fully developed, continue to erupt throughout its lifetime as the grinding surface is worn down through chewing. Because of this pattern of wear, a rough estimate of a horse's age can be made from an examination of the teeth. Abnormal wear of the teeth, caused by conformational defects, abnormal behaviors, or improper diets, can cause serious health issues and can even result in the death of the horse.

Feet/hooves[edit]

The hoof of the horse encases the second and third phalanx of the lower limbs, analogous to the fingertip or toe tip of a human. In essence, a horse travels on its "tiptoes". The hoof wall is a much larger, thicker and stronger version of the human fingernailor toenail, made up of similar materials, primarily keratin, a very strong protein molecule. The horse's hoof contains a high proportion of sulfur-containing amino acids which contribute to its resilience and toughness. Vascular fold-like structures called laminae suspend the distal phalanx from the hoof wall.

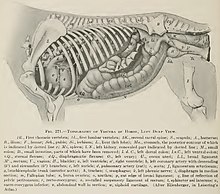

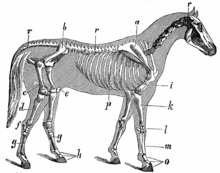

Skeletal system[edit]

The skeleton of the horse has three major functions in the body. It protects vital organs, provides framework, and supports soft parts of the body. Horses have 205 bones, which are divided into the appendicular skeleton (the legs) and the axial skeleton (the skull, vertebral column, sternum, and ribs). Both pelvic and thoracic limbs contain the same number of bones, 20 bones per limb. Bones are connected to muscles via tendons and other bones via ligaments. Bones are also used to store minerals, and are the site of red blood cell formation.

- The Appendicular system includes the limbs of the horse;

- The Axial system is composed of the spine, ribs and skull;

The bones of the horse are the same as those of other domestic species, but the third metacarpal and metatarsal are much more developed and the second and fourth are undeveloped, having the first and fifth metacarpal and metatarsal.[21]

| Spine | 54 |

| Ribs | 36 |

| Sternum | 01 |

| Head (including ear ) | 34 |

| Thoracic region | 40 |

| Pelvic region | 40 |

Ligaments and tendons[edit]

Ligaments[edit]

Ligaments attach bone to bone or bone to tendon, and are vital in stabilizing joints as well as supporting structures. They are made up of fibrous material that is generally quite strong. Due to their relatively poor blood supply, ligament injuries generally take a long time to heal.

Tendons[edit]

Tendons are cords of connective tissue attaching muscle to bone, cartilage or other tendons. They are a major contributor to shock absorption, are necessary for support of the horse's body, and translate the force generated by muscles into movement. Tendons are classified as flexors (flex a joint) or extensors (extend a joint). However, some tendons will flex multiple joints while extending another (the flexor tendons of the hind limb, for example, will flex the fetlock, pastern, and coffin joint, but extend the hock joint). In this case, the tendons (and associated muscles) are named for their most distal action (digital flexion).

Tendons form in the embryo from fibroblasts which become more tightly packed as the tendon grows. As tendons develop they lay down collagen, which is the main structural protein of connective tissue. As tendons pass near bony prominences, they are protected by a fluid filled synovial structure, either a tendon sheath or a sac called a bursa.

Tendons are easily damaged if placed under too much strain, which can result in a painful, and possibly career-ending, injury. Tendinitis is most commonly seen in high performance horses that gallop or jump. When a tendon is damaged the healing process is slow because tendons have a poor blood supply, reducing the availability of nutrients and oxygen to the tendon. Once a tendon is damaged the tendon will always be weaker, because the collagen fibres tend to line up in random arrangements instead of the stronger linear pattern. Scar tissue within the tendon decreases the overall elasticity in the damaged section of the tendon as well, causing an increase in strain on adjacent uninjured tissue.

Respiratory system and smell[edit]

The horse's respiratory system consists of the nostrils, pharynx, larynx, trachea, diaphragm, and lungs. Additionally, the nasolacrimal duct and sinuses are connected to the nasal passage. The horse's respiratory system not only allows the animal to breathe, but also is important in the horse's sense of smell (olfactory ability) as well as in communicating. The soft palate blocks off the pharynx from the mouth (oral cavity) of the horse, except when swallowing. This helps prevent the horse from inhaling food, but also means that a horse cannot use its mouth to breathe when in respiratory distress—a horse can only breathe through its nostrils, also called obligate nasal breathing.[22] For this same reason, horses also cannot pant as a method of thermoregulation. The genus Equusalso has a unique part of the respiratory system called the guttural pouch, which is thought to equalize air pressure on the tympanic membrane. Located between the mandibles but below the occiput, it fills with air when the horse swallows or exhales.

The eye[edit]

The horse has one of the largest eyes of all land mammals.[24] Eye size in mammals is significantly correlated to maximum running speed as well as to body size, in accordance with Leuckart's law; animals capable of fast locomotion require large eyes.[25] The eye of the horse is set to the side of its skull, consistent with that of a prey animal.[24] The horse has a wide field of monocular vision, as well as good visual acuity. Horses have two-color, or dichromatic vision, which is somewhat like red-green color blindness in humans.[26] Because the horse's vision is closely tied to behavior, the horse's visual abilities are often taken into account when handling and training the animal.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Equine_anatomy

Equine dentistry is the practice of dentistry in horses, involving the study, diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of diseases, disorders and conditions of the oral cavity, maxillofacial area and the adjacent and associated structures.

The practice of equine dentistry varies widely by jurisdiction, with procedures being performed by veterinary physicians (both in general and specialist practice), specialist professionals termed equine dental technicians or equine dentists, and by amateurs, such as horse owners, with varying levels of training.

In some jurisdictions, the practice of equine dentistry, or specific elements of equine dentistry, may be restricted only to specialists with specified qualifications or experience, whereas in others it is not controlled.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Equine_dentistry

Equus is a genus of mammals in the family Equidae, which includes horses, donkeys, and zebras. Within the Equidae, Equus is the only recognized extant genus, comprising seven living species. Like Equidae more broadly, Equus has numerous extinct species known only from fossils. The genus most likely originated in North America and spread quickly to the Old World. Equines are odd-toed ungulates with slender legs, long heads, relatively long necks, manes (erect in most subspecies), and long tails. All species are herbivorous, and mostly grazers, with simpler digestive systems than ruminants but able to subsist on lower-quality vegetation.

While the domestic horse and donkey (along with their feral descendants) exist worldwide, wild equine populations are limited to Africa and Asia. Wild equine social systems are in two forms; a harem system with tight-knit groups consisting of one adult male or stallion, several females or mares, and their young or foals; and a territorial system where males establish territories with resources that attract females, which associate very fluidly. In both systems, females take care of their offspring, but males may play a role as well. Equines communicate with each other both visually and vocally. Human activities have threatened wild equine populations.

| Scientific classification | |

|---|---|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Perissodactyla |

| Family: | Equidae |

| Tribe: | Equini |

| Genus: | Equus Linnaeus, 1758 |

| Type species | |

| Equus caballus [2] Linnaeus, 1758 | |

| Extant species | |

| |

Taxonomic and evolutionary history[edit]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cladogram of Equus after Vilstrup et al. (2013).[7] |

The genus Equus was first described by Carl Linnaeus in 1758. It is the only recognized extant genus in the family Equidae.[8] The first equids were small, dog-sized mammals (e.g. Eohippus) adapted for browsing on shrubs during the Eocene, around 54 million years ago (Mya). These animals had three toes on the hind feet and four on the front feet with small hooves in place of claws, but also had soft pads.[9] Equids developed into larger, three-toed animals (e.g. Mesohippus) during the Oligocene and Miocene.[8][9] From there, the side toes became progressively smaller through the Pleistocene until the emergence of the single-toed Equus.[10]

The genus Equus, which includes all extant equines, is believed to have evolved from Dinohippus, via the intermediate form Plesippus. One of the oldest species is Equus simplicidens, described as zebra-like with a donkey-like head shape. The oldest material to date was found in Idaho, USA. The genus appears to have spread quickly into the Old World, with the similarly aged E. livenzovensis documented from western Europe and Russia.[10] Molecular phylogenies indicate that the most recent common ancestor of all modern equines (members of the genus Equus) lived ~5.6 (3.9-7.8) Mya. Direct paleogenomic sequencing of a 700,000-year-old middle Pleistocene horse metapodial bone from Canada implies a more recent 4.07 Mya for the most recent common ancestor within the range of 4.0 to 4.5 Mya.[11]

Mitochondrial evidence supports the division of Equus species into noncaballoid (which includes zebras and asses) and caballoids or "true horses" (which includes E. ferus and E. przewalskii).[7][12] Of the extant equine species, the lineage of the asses may have diverged first,[8] possibly as soon as Equus reached the Old World.[12] Zebras appear to be monophyletic and differentiated in Africa, where they are endemic.[7] Members of the subgenus Sussemionus were abundant during the Early and Middle Pleistocene of North America and Afro-Eurasia,[13] but only a single species, E. ovodovi survived into the Late Pleistocene and Holocene in south Siberia and China, with the youngest remains from China dating to around 3500 BP (1500 BC), during the Shang dynasty.[14][15] Genetic data from E. ovodovi has placed the Sussemionus lineage as closer to zebras and asses than to caballine horses.[15]

Molecular dating indicates the caballoid lineage diverged from the noncaballoids 4 Mya.[7] Genetic results suggest that all North American fossils of caballine equines, as well as South American fossils traditionally placed in the subgenus E. (Amerhippus), belong to E. ferus.[16] Remains attributed to a variety of species and lumped together as New World stilt-legged horses (including E. francisci, E. tau, and E. quinni) probably all belong to a second species that was endemic to North America.[17] This was confirmed in a genetic study done in 2017, which subsumed all the specimens into the species E. francisci which was placed outside all extant horse species in the new genus Haringtonhippus[18], although its placement as a separate genus was subsequently questioned.[19] A separate genus of horse, Hippidion existed in South America.[20] The possible causes of the extinction of horses in the Americas (about 12,000 years ago) have been a matter of debate. Hypotheses include climatic change and overexploitation by newly arrived humans.[21][22] Horses only returned to the American mainland with the arrival of the conquistadores in 1519.[23]

Extant species[edit]

| hideSubgenus | Image | Scientific name | Common name | Distribution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Equus |   | Equus ferus | Wild horse(includes domesticated horseand Przewalski's horse) | Eurasia |

| Asinus |  | Equus africanus | African wild ass(includes domesticated donkey) | Horn of Africa, in Eritrea, Ethiopia and Somalia |

| Equus hemionus | Onager, hemione, or Asiatic wild ass | Iran, Pakistan, India, and Mongolia, including in Central Asian hot and cold deserts of Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, and China | |

| Equus kiang | Kiang | Tibetan Plateau | |

| Hippotigris |  | Equus grevyi | Grévy's zebra | Kenya and Ethiopia |

| Equus quagga | Plains zebra | south of Ethiopia through East Africa to as far south as Botswana and eastern South Africa | |

| Equus zebra | Mountain zebra | south-western Angola, Namibia and South Africa. |

Prehistoric Species[edit]

Many extinct prehistoric species of Equus have been described. The validity of some of these species is questionable and a matter of debate. For example, Equus niobrarensis is likely synonymous with Equus scotti, while Equus alaskae is most likely the same species as Equus lambei, which itself may be a North American form of the living Equus przewalskii.

DNA studies on American horse remains found frozen into permafrost have shown that several of the supposed American species, and the European Equus ferus, are actually one highly-variable widespread species. [24], as if the evolutionary process of speciation was persistently being frustrated by large herds of the horses moving long distances and mixing, carrying their genes about with them.

- Equus alaskae - Alaskan horse

- Equus algericus

- Equus capensis - Giant zebra

- Equus conversidens - Mexican horse

- Equus dalianensis

- Equus lenensis - Siberian horse

- Equus latipes

- Equus fraternus

- Equus giganteus - Giant horse

- Equus lambei - Yukon horse

- Equus mauritanicus - Saharan zebra

- Equus namadicus

- Equus neogeus - often placed in a separate genus, Amerhippus

- Equus niobrarensis - Niobrara horse

- Equus occidentalis - Western horse

- Equus scotti - Scott's horse

- Equus semiplicatus

- Equus simplicidens - Hagerman horse

- Equus sivalensis - Indian horse

- Equus stenonis - Stenon zebra

- Equus yunnanensis - Yunnan horse

Hybrids[edit]

Equine species can crossbreed with each other. The most common hybrid is the mule, a cross between a male donkey and a female horse. With rare exceptions, these hybrids are sterile and cannot reproduce.[25] A related hybrid, a hinny, is a cross between a male horse and a female donkey.[26] Other hybrids include the zorse, a cross between a zebra and a horse[27] and a zonkey or zedonk, a hybrid of a zebra and a donkey.[28] In areas where Grévy's zebras are sympatric with plains zebras, fertile hybrids do occur.[29] Ancient DNA identifies the Bronze Age kunga as a cross between the Syrian wild ass and the donkey.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Equus_(genus)

No comments:

Post a Comment