| Latin | |

|---|---|

| |

| Native to | |

| Ethnicity | |

| Era | 7th century BC – 18th century AD |

Early form | |

| Latin alphabet (Latin script) | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

| Regulated by | Pontifical Academy for Latin |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | la |

| ISO 639-2 | lat |

| ISO 639-3 | lat |

| Glottolog | impe1234lati1261 |

| Linguasphere | 51-AAB-aa to 51-AAB-ac |

Greatest extent of the Roman Empire under Emperor Trajan (c. 117 AD) and the area governed by Latin speakers. Many languages other than Latin were spoken within the empire. | |

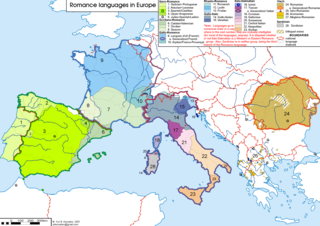

Range of the Romance languages, the modern descendants of Latin, in Europe. | |

Latin (lingua Latīna [ˈlɪŋɡʷa ɫaˈtiːna] or Latīnum [ɫaˈtiːnʊ̃]) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in Latium (also known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area around present-day Rome,[1] but through the power of the Roman Republic it became the dominant language in the Italian region and subsequently throughout the Roman Empire. Even after the fall of Western Rome, Latin remained the common language of international communication, science, scholarship and academia in Europe until well into the 18th century, when other regional vernaculars (including its own descendants, the Romance languages) supplanted it in common academic and political usage. For most of the time it was used, it would be considered a "dead language" in the modern linguistic definition; that is, it lacked native speakers, despite being used extensively and actively.

Latin is a highly inflected language, with three distinct genders (masculine, feminine, and neuter), six or seven noun cases (nominative, accusative, genitive, dative, ablative, vocative, and vestigial locative), five declensions, four verb conjugations, six tenses (present, imperfect, future, perfect, pluperfect, and future perfect), three persons, three moods, two voices (passive and active), two or three aspects, and two numbers (singular and plural). The Latin alphabet is directly derived from the Etruscan and Greek alphabets.

By the late Roman Republic (75 BC), Old Latin had been standardized into Classical Latin. Vulgar Latin was the colloquial form with less prestigious variations attested in inscriptions and the works of comic playwrights Plautus and Terence[2] and author Petronius. Late Latin is the written language from the 3rd century, and its various Vulgar Latin dialects developed in the 6th to 9th centuries into the modern Romance languages.

In Latin's usage beyond the early medieval period, it lacked native speakers. Medieval Latin was used across Western and Catholic Europe during the Middle Ages as a working and literary language from the 9th century to the Renaissance, which then developed a Classifying and purified form, called Renaissance Latin. This was the basis for Neo-Latin which evolved during the early modern era. In these periods, while Latin was used productively, it was generally taught to be written and spoken, at least until the late seventeenth century, when spoken skills began to erode. Later, it became increasingly taught only to be read.

One form of Latin, Ecclesiastical Latin, remains the official language of the Holy See and the Roman Rite of the Catholic Church at Vatican City. The church continues to adapt concepts from modern languages, contributing to the continued development of the Latin language. Contemporary Latin, however—Neo-Latin in its most recent form—is rarely spoken, and has limited productive use.

Latin has also greatly influenced the English language and historically contributed many words to the English lexicon after the Christianization of Anglo-Saxons and the Norman conquest. In particular, Latin (and Ancient Greek) roots are still used in English descriptions of theology, science disciplines (especially anatomy and taxonomy), medicine, and law.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Latin

| Marcus Aurelius | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Marble bust, Musée Saint-Raymond | |||||||||

| Roman emperor | |||||||||

| Reign | 7 March 161 – 17 March 180 | ||||||||

| Predecessor | Antoninus Pius | ||||||||

| Successor | Commodus | ||||||||

| Co-emperor |

| ||||||||

| Born | 26 April 121 Rome, Roman Italy | ||||||||

| Died | 17 March 180 (aged 58) Vindobona, Pannonia Superior, or Sirmium, Pannonia Inferior | ||||||||

| Burial | |||||||||

| Spouse | Faustina the Younger (m. 145; d. 175) | ||||||||

| Issue Detail | 14, including Commodus, Marcus Annius Verus Caesar, Lucilla, Annia Galeria Aurelia Faustina, Fadilla, Annia Cornificia Faustina Minor, and Vibia Aurelia Sabina | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Dynasty | Nerva–Antonine | ||||||||

| Father |

| ||||||||

| Mother | Domitia Calvilla | ||||||||

| Religion | Ancient Roman religion | ||||||||

Philosophy career | |||||||||

| Notable work | Meditations | ||||||||

| Era | Hellenistic philosophy | ||||||||

| Region | Western philosophy | ||||||||

| School | Stoicism | ||||||||

Main interests | Ethics | ||||||||

Notable ideas | Memento mori[1] | ||||||||

Influences | |

Influenced |

| Roman imperial dynasties | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||

| Nerva–Antonine dynasty (AD 96–192) | ||||||||||||||

| Chronology | ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

| Family | ||||||||||||||

| Succession | ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

| Part of a series on |

| Marcus Aurelius |

|---|

|

Misc.

|

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (Latin: [ˈmaːrkʊs au̯ˈreːliʊs antoːˈniːnʊs]; English: /ɔːˈriːliəs/ aw-REE-lee-əs;[2] 26 April 121 – 17 March 180) was Roman emperor from 161 to 180 AD and a Stoic philosopher. He was a member of the Nerva–Antonine dynasty, the last of the rulers later known as the Five Good Emperors and the last emperor of the Pax Romana, an age of relative peace, calm, and stability for the Roman Empire lasting from 27 BC to 180 AD. He served as Roman consul in 140, 145, and 161.

Marcus Aurelius was born during the reign of Hadrian to the emperor's nephew, the praetor Marcus Annius Verus, and the heiress Domitia Calvilla. His father died when he was three, and he was raised by his mother and his paternal grandfather. After Hadrian's adoptive son, Aelius Caesar, died in 138, the emperor adopted Marcus's uncle Antoninus Pius as his new heir. In turn, Antoninus adopted Marcus and Lucius, the son of Aelius. Hadrian died that year, and Antoninus became emperor. Now heir to the throne, Marcus studied Greek and Latin under tutors such as Herodes Atticus and Marcus Cornelius Fronto. He married Antoninus' daughter Faustina in 145.

After Antoninus died in 161, Marcus Aurelius acceded to the throne alongside his adoptive brother, who reigned under the name Lucius Verus. Under his rule the Roman Empire witnessed heavy military conflict. In the East, the Romans fought successfully with a revitalized Parthian Empire and the rebel Kingdom of Armenia. Marcus defeated the Marcomanni, Quadi, and Sarmatian Iazyges in the Marcomannic Wars; however, these and other Germanic peoples began to represent a troubling reality for the Empire. He modified the silver purity of the Roman currency, the denarius. The persecution of Christians in the Roman Empire appears to have increased during his reign, but his involvement in this is unlikely since there is no record of early Christians in the 2nd century calling him a persecutor, and Tertullian even called Marcus a "protector of Christians".[3] The Antonine Plague broke out in 165 or 166 and devastated the population of the Roman Empire, causing the deaths of five to ten million people. Lucius Verus may have died from the plague in 169.

Unlike some of his predecessors, Marcus chose not to adopt an heir. His children included Lucilla, who married Lucius, and Commodus, whose succession after Marcus has been a subject of debate among both contemporary and modern historians. The Column and Equestrian Statue of Marcus Aurelius still stand in Rome, where they were erected in celebration of his military victories. Meditations, the writings of "the philosopher" – as contemporary biographers called Marcus – are a significant source of the modern understanding of ancient Stoic philosophy. These writings have been praised by fellow writers, philosophers, monarchs, and politicians centuries after his death.

Sources

The major sources depicting the life and rule of Marcus Aurelius are patchy and frequently unreliable. The most important group of sources, the biographies contained in the Historia Augusta, claimed to be written by a group of authors at the turn of the 4th century AD, but it is believed they were in fact written by a single author (referred to here as 'the biographer') from about AD 395.[4] The later biographies and the biographies of subordinate emperors and usurpers are unreliable, but the earlier biographies, derived primarily from now-lost earlier sources (Marius Maximus or Ignotus), are considered to be more accurate.[5] For Marcus's life and rule, the biographies of Hadrian, Antoninus, Marcus, and Lucius are largely reliable, but those of Aelius Verus and Avidius Cassius are not.[6]

A body of correspondence between Marcus's tutor Fronto and various Antonine officials survives in a series of patchy manuscripts, covering the period from c. 138 to 166.[7][8] Marcus's own Meditations offer a window on his inner life, but are largely undateable and make few specific references to worldly affairs.[9] The main narrative source for the period is Cassius Dio, a Greek senator from Bithynian Nicaea who wrote a history of Rome from its founding to 229 in eighty books. Dio is vital for the military history of the period, but his senatorial prejudices and strong opposition to imperial expansion obscure his perspective.[10] Some other literary sources provide specific details: the writings of the physician Galen on the habits of the Antonine elite, the orations of Aelius Aristides on the temper of the times, and the constitutions preserved in the Digest and Codex Justinianeus on Marcus' legal work.[11] Inscriptions and coin finds supplement the literary sources.[12]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marcus_Aurelius

| Lucius Verus | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||

| Roman emperor | |||||||||

| Reign | 7 March 161 – 169 | ||||||||

| Predecessor | Antoninus Pius | ||||||||

| Successor | Marcus Aurelius | ||||||||

| Co-emperor | Marcus Aurelius | ||||||||

| Born | 15 December 130 Rome, Italy | ||||||||

| Died | Early 169 (aged 38) Altinum, Italy | ||||||||

| Burial | |||||||||

| Spouse | |||||||||

| Issue | 3 (died young) | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Dynasty | Nerva–Antonine | ||||||||

| Father |

| ||||||||

| Mother | Avidia | ||||||||

| Roman imperial dynasties | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nerva–Antonine dynasty (AD 96–192) | ||||||||||||||

| Chronology | ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

| Family | ||||||||||||||

| Succession | ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

Lucius Aurelius Verus (15 December 130 – January/February 169) was Roman emperor from 161 until his death in 169, alongside his adoptive brother Marcus Aurelius. He was a member of the Nerva-Antonine dynasty. Verus' succession together with Marcus Aurelius marked the first time that the Roman Empire was ruled by more than one emperor simultaneously, an increasingly common occurrence in the later history of the Empire.

Born on 15 December 130, he was the eldest son of Lucius Aelius Caesar, first adopted son and heir to Hadrian. Raised and educated in Rome, he held several political offices prior to taking the throne. After his biological father's death in 138, he was adopted by Antoninus Pius, who was himself adopted by Hadrian. Hadrian died later that year, and Antoninus Pius succeeded to the throne. Antoninus Pius would rule the empire until 161, when he died, and was succeeded by Marcus Aurelius, who later raised his adoptive brother Verus to co-emperor.

As emperor, the majority of his reign was occupied by his direction of the war with Parthia which ended in Roman victory and some territorial gains. After initial involvement in the Marcomannic Wars, he fell ill and died in 169. He was deified by the Roman Senate as the Divine Verus (Divus Verus).

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lucius_Verus

| Hadrian | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Bust of Hadrian, c. 130 | |||||

| Roman emperor | |||||

| Reign | 11 August 117 – 10 July 138 | ||||

| Predecessor | Trajan | ||||

| Successor | Antoninus Pius | ||||

| Born | Publius Aelius Hadrianus 24 January 76 Italica, Hispania Baetica, present-day Spain | ||||

| Died | 10 July 138 (aged 62) Baiae, Italia | ||||

| Burial | |||||

| Spouse | Vibia Sabina | ||||

| Adoptive children | |||||

| |||||

| Dynasty | Nerva–Antonine | ||||

| Father |

| ||||

| Mother | Domitia Paulina | ||||

| Religion | Hellenistic religion | ||||

| Roman imperial dynasties | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||

| Nerva–Antonine dynasty (AD 96–192) | ||||||||||||||

| Chronology | ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

| Family | ||||||||||||||

| Succession | ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

Hadrian (/ˈheɪdriən/, HAY-dree-ən; Latin: Caesar Traianus Hadrianus [ˈkae̯sar trajˈjaːnʊs (h)adriˈjaːnʊs]; 24 January 76 – 10 July 138) was Roman emperor from 117 to 138. A member of the Nerva-Antonine dynasty and one of the so-called "Five Good Emperors", he is renowned for his travels throughout the empire and the civil and military constructions of his reign. Later historians regarded Hadrian as a "benevolent dictator" while the Senate found him remote and authoritarian. He has been described as enigmatic and contradictory, with a capacity for both great personal generosity and extreme cruelty and driven by insatiable curiosity, self-conceit, and ambition. [2]

Hadrian was born in Italica, close to modern Seville in Spain, an Italic settlement in Hispania Baetica; his branch of the Aelia gens, the Aeli Hadriani, came from the town of Hadria in eastern Italy. Early in his career, Hadrian married Vibia Sabina, grandniece of the ruling emperor, Trajan. The marriage, and his later succession as emperor were probably promoted by Trajan's wife Pompeia Plotina. On his succession, Hadrian had four leading senators put to death. This earned him the senate's lifelong enmity. He earned further disapproval among the elite by abandoning Trajan's expansionist policies and territorial gains in Mesopotamia, Assyria, Armenia, and parts of Dacia. Hadrian preferred to invest in the development of stable, defensible borders and the unification of the empire's disparate peoples.

Hadrian travelled almost constantly throughout the empire and indulged a preference for direct intervention in imperial affairs, especially building projects. He is particularly known for building Hadrian's Wall, which marked the northern limit of Britannia. In Rome itself, he rebuilt the Pantheon and constructed the vast Temple of Venus and Roma. In Egypt, he may have rebuilt the Serapeum of Alexandria. He was an ardent admirer of Greece and sought to make Athens the cultural capital of the Empire. His intense romantic relationship with Greek youth Antinous and the latter's untimely death led Hadrian to establish a widespread, popular cult. Late in his reign, in Judaea, he suppressed the Bar Kokhba revolt.

Hadrian's last years were marred by chronic illness. He adopted Antoninus Pius in 138 and nominated him as a successor on the condition that Antoninus adopt Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus as his own heirs. Hadrian died the same year at Baiae, and Antoninus had him deified, despite opposition from the Senate.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hadrian

| Vibia Sabina | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Augusta | |||||||||

Statue of Vibia Sabina (Villa Adriana, Tivoli) | |||||||||

| Roman empress | |||||||||

| Tenure | 117 – 136/137 | ||||||||

| Born | 83 Rome, Italy | ||||||||

| Died | 136/137 | ||||||||

| Spouse | Hadrian | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Dynasty | Nerva–Antonine | ||||||||

| Father | Lucius Vibius Sabinus | ||||||||

| Mother | Salonia Matidia | ||||||||

Vibia Sabina (83–136/137) was a Roman Empress, wife and second cousin once removed to the Roman Emperor Hadrian. She was the daughter of Matidia (niece of Roman Emperor Trajan) and suffect consul Lucius Vibius Sabinus.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vibia_Sabina

Augusta (Classical Latin: [au̯ˈɡʊsta]; plural Augustae; Greek: αὐγούστα)[1] was a Roman imperial honorific title given to empresses and honoured women of the imperial families. It was the feminine form of Augustus. In the third century, Augustae could also receive the titles of Mater Senatus ("Mother of the Senate") and Mater Castrorum ("Mother of the Camp") and Mater Patriae ("Mother of the Fatherland").

The title implied the greatest prestige. Augustae could issue their own coinage, wear imperial regalia, and rule their own courts.[1]

Wife of Claudius, Agrippina was the first wife of the emperor in Roman history to receive the throne of Augusta, a position she held for the rest of her life, ruling with her husband and son.

In the third century, Julia Domna was the first empress to receive the title combination "Pia Felix Augusta" after the death of her husband Septimius Severus, which may have implied greater powers being vested in her than what was usual for a Roman empress mother and in this innumerable official position and honor, she accompanied his son on an extensive military campaign and provincial tour.[2]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Augustae

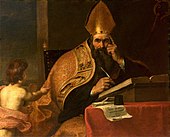

Augustine of Hippo | |

|---|---|

| |

| Bishop of Hippo Regius Doctor of the Church | |

| Born | Aurelius Augustinus 13 November 354 Thagaste, Numidia Cirtensis, Roman Empire (modern-day Souk Ahras, Algeria) |

| Died | 28 August 430 (aged 75) Hippo Regius, Numidia Cirtensis, Western Roman Empire (modern-day Annaba, Algeria) |

| Resting place | Pavia, Italy |

| Venerated in | All Christian denominations which venerate saints |

| Canonized | Pre-Congregation |

| Major shrine | San Pietro in Ciel d'Oro, Pavia, Italy |

| Feast |

|

| Attributes | Crozier, miter, young child, book, small church, flaming or pierced heart.[1] |

| Patronage | |

Philosophy career | |

| Notable work | |

| Era | |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | |

| Notable students | Paul Orosius[27] Prosper of Aquitaine |

Main interests | |

Notable ideas | |

Influences | |

Influenced | |||

Ordination history | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Source(s):[28][29] |

| Part of a series on |

| Augustinianism |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Augustine of Hippo |

|---|

|

| Augustinianism |

| Works |

| Influences and followers |

| Related topics |

| Related categories |

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Theodicy |

|---|

|

|

|

|

Augustine of Hippo (/ɔːˈɡʌstɪn/ aw-GUST-in, US also /ˈɔːɡəstiːn/ AW-gə-steen;[30] Latin: Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430),[31] also known as Saint Augustine, was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North Africa. His writings influenced the development of Western philosophy and Western Christianity, and he is viewed as one of the most important Church Fathers of the Latin Church in the Patristic Period. His many important works include The City of God, On Christian Doctrine, and Confessions.

According to his contemporary, Jerome, Augustine "established anew the ancient Faith".[a] In his youth he was drawn to the eclectic Manichaean faith, and later to the Hellenistic philosophy of Neoplatonism. After his conversion to Christianity and baptism in 386, Augustine developed his own approach to philosophy and theology, accommodating a variety of methods and perspectives.[32] Believing the grace of Christ was indispensable to human freedom, he helped formulate the doctrine of original sin and made significant contributions to the development of just war theory. When the Western Roman Empire began to disintegrate, Augustine imagined the Church as a spiritual City of God, distinct from the material Earthly City.[33] The segment of the Church that adhered to the concept of the Trinity as defined by the Council of Nicaea and the Council of Constantinople[34] closely identified with Augustine's On the Trinity.

Augustine is recognized as a saint in the Catholic Church, the Eastern Orthodox Church, the Lutheran Churches and the Anglican Communion. He is also a preeminent Catholic Doctor of the Church and the patron of the Augustinians. His memorial is celebrated on 28 August, the day of his death. Augustine is the patron saint of brewers, printers, theologians, and a number of cities and dioceses.[35] His thoughts profoundly influenced the medieval worldview. Many Protestants, especially Calvinists and Lutherans, consider him one of the theological fathers of the Protestant Reformation due to his teachings on salvation and divine grace.[36][37][38] Protestant Reformers generally, and Martin Luther in particular, held Augustine in preeminence among early Church Fathers. From 1505 to 1521, Luther was a member of the Order of the Augustinian Eremites.

In the East, his teachings are more disputed, and were notably attacked by John Romanides,[39] but other theologians and figures of the Eastern Orthodox Church have shown significant approbation of his writings, chiefly Georges Florovsky.[40] The most controversial doctrine associated with him, the filioque,[41] was rejected by the Eastern Orthodox Church.[42] Other disputed teachings include his views on original sin, the doctrine of grace, and predestination.[41] Though considered to be mistaken on some points, he is still considered a saint and has influenced some Eastern Church Fathers, most notably Gregory Palamas.[43] In the Greek and Russian Orthodox Churches, his feast day is celebrated on 15 June.[41][44] The historian Diarmaid MacCulloch has written: "Augustine's impact on Western Christian thought can hardly be overstated; only his beloved example, Paul of Tarsus, has been more influential, and Westerners have generally seen Paul through Augustine's eyes."[45]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Augustine_of_Hippo

| Part of the Politics series |

| Basic forms of government |

|---|

| List of forms of government |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Oligarchy (from Ancient Greek ὀλιγαρχία (oligarkhía) 'rule by few'; from ὀλίγος (olígos) 'few', and ἄρχω (árkhō) 'to rule, command')[1][2][3] is a conceptual form of power structure in which power rests with a small number of people. These people may or may not be distinguished by one or several characteristics, such as nobility, fame, wealth, education, or corporate, religious, political, or military control.

Throughout history, power structures considered to be oligarchies have often been viewed as tyrannical,[citation needed] relying on public obedience or oppression to exist. Aristotle pioneered the use of the term as meaning rule by the rich,[4] for which another term commonly used today is plutocracy. One of the first oligarchies in history is that of Sparta, which developed the concept alongside its rival Athens, and essentially provided a counterpoint to Athenian democracy. In the early 20th century Robert Michels developed the theory that democracies, like all large organizations, tend to turn into oligarchies. In his "Iron law of oligarchy" he suggests that the necessary division of labor in large organizations leads to the establishment of a ruling class mostly concerned with protecting their own power.

Minority rule

The exclusive consolidation of power by a dominant religious or ethnic minority has also been described as a form of oligarchy.[5] Examples of this system include South Africa under apartheid, Liberia under Americo-Liberians, the Sultanate of Zanzibar, and Rhodesia, where the installation of oligarchic rule by the descendants of foreign settlers was primarily regarded as a legacy of various forms of colonialism.[5]

Putative oligarchies

A business group might be defined as an oligarchy if it satisfies all of the following conditions:

- Owners are the largest private owners in the country.

- It possesses sufficient political power to promote its own interests.

- Owners control multiple businesses, which intensively coordinate their activities.[6]

Intellectual oligarchies

George Bernard Shaw defined in his play Major Barbara, premiered in 1905 and first published in 1907, a new type of Oligarchy namely the intellectual oligarchy that acts against the interests of the common people: "I now want to give the common man weapons against the intellectual man. I love the common people. I want to arm them against the lawyer, the doctor, the priest, the literary man, the professor, the artist, and the politician, who, once in authority, is the most dangerous, disastrous, and tyrannical of all the fools, rascals, and impostors. I want a democratic power strong enough to force the intellectual oligarchy to use its genius for the general good or else perish."[7]

Cases perceived as oligarchies

Jeffrey A. Winters and Benjamin I. Page have described Colombia, Indonesia, Russia, Singapore, and the United States as oligarchies.[8]

Philippines

During the presidency of Ferdinand Marcos from 1965 to 1986, several monopolies arose in the Philippines, particularly centred around the family and close associates of the president. This period, as well as subsequent decades, have led some analysts to describe the country as an oligarchy.[9][10][11][12] President Rodrigo Duterte, who was elected in 2016, spoke of dismantling oligarchy during his presidency.[13][12]

Russian Federation

Since the collapse of the Soviet Union and privatization of the economy in December 1991, privately owned Russia-based multinational corporations, including producers of petroleum, natural gas, and metal have, in the view of many analysts, led to the rise of Russian oligarchs.[14] Most of these are connected directly to the highest-ranked government officials, such as the president.

Iran

The religious government of Iran formed after the 1979 Iranian revolution is described as a clerical oligarchy led by a coalition of militant Khomeinist ideologues and fundamentalist Shia clergy. The ruling system led by clerical oligarchs is known as "Velayat e-Faqih" , i.e., governance by a class of Twelver Shia marja designated with the title of "Ayatollah". Highest ranking Shia cleric in the political system is the "Rahbar" (Supreme Leader) who serves for life and is considered to be "protector of the faith" in Khomeinist theology. The clerical oligarchs supervise the activities of the parliament and controls the armed forces, state media, sectors of the national economy and religious funds. The Rahbar is also the military chief of the Iranian armed forces and directly controls the conglomerate of Khomeinist paramilitaries known as the IRGC.[15][16]

Ukraine

The Ukrainian oligarchs are a group of business oligarchs that quickly appeared on the economic and political scene of Ukraine after its independence in 1991. Overall there are 35 oligarchic groups.[6]

On 23 September 2021 the Ukrainian government released law No. 1780-ІХ which is primarily focused on protecting national interest and limiting oligarchs impact on democracy in Ukraine.

United States

Some contemporary authors have characterized conditions in the United States in the 21st century as oligarchic in nature.[18][19] Simon Johnson wrote in 2009 that "the reemergence of an American financial oligarchy is quite recent", a structure which he delineated as being the "most advanced" in the world.[20] Jeffrey A. Winters wrote that "oligarchy and democracy operate within a single system, and American politics is a daily display of their interplay."[21] The top 1% of the U.S. population by wealth in 2007 had a larger share of total income than at any time since 1928.[22] In 2011, according to PolitiFact and others, the top 400 wealthiest Americans "have more wealth than half of all Americans combined."[23][24][25][26]

In 1998, Bob Herbert of The New York Times referred to modern American plutocrats as "The Donor Class"[27][28] (list of top donors)[29] and defined the class, for the first time,[30] as "a tiny group—just one-quarter of 1 percent of the population—and it is not representative of the rest of the nation. But its money buys plenty of access."[27]

French economist Thomas Piketty states in his 2013 book, Capital in the Twenty-First Century, that "the risk of a drift towards oligarchy is real and gives little reason for optimism about where the United States is headed."[31]

A 2014 study by political scientists Martin Gilens of Princeton University and Benjamin Page of Northwestern University stated that "majorities of the American public actually have little influence over the policies our government adopts."[32] The study analyzed nearly 1,800 policies enacted by the US government between 1981 and 2002 and compared them to the expressed preferences of the American public as opposed to wealthy Americans and large special interest groups.[33] It found that wealthy individuals and organizations representing business interests have substantial political influence, while average citizens and mass-based interest groups have little to none. The study did concede that "Americans do enjoy many features central to democratic governance, such as regular elections, freedom of speech and association, and a widespread (if still contested) franchise." Gilens and Page do not characterize the US as an "oligarchy" per se; however, they do apply the concept of "civil oligarchy" as used by Jeffrey Winters with respect to the US. Winters has posited a comparative theory of "oligarchy" in which the wealthiest citizens—even in a "civil oligarchy" like the United States—dominate policy concerning crucial issues of wealth- and income protection.[34]

Gilens says that average citizens only get what they want if wealthy Americans and business-oriented interest groups also want it; and that when a policy favored by the majority of the American public is implemented, it is usually because the economic elites did not oppose it.[35] Other studies have criticized the Page and Gilens study.[36][37][38][39] Page and Gilens have defended their study from criticism.[39]

In a 2015 interview, former President Jimmy Carter stated that the United States is now "an oligarchy with unlimited political bribery" due to the Citizens United v. FEC ruling which effectively removed limits on donations to political candidates.[40] Wall Street spent a record $2 billion trying to influence the 2016 United States presidential election.[41][42]

China

Since 1950, China has commonly been considered an oligarchy. "China describes itself as a communist “people’s republic,” but leadership of the country has been maintained by a select few for several decades. Members of the oligarchy have included those who were part of the Communist Party and the revolution in 1949, as well as those who came into wealth and power since the opening of China to the global market in the 1980s (often descendants of the early revolutionaries). This system has helped the wealthy and powerful maintain their control, while providing relatively little power or freedom to most citizens."[43]

See also

- Aristocracy

- Cacique democracy

- Despotism

- Dictatorship

- Inverted totalitarianism

- Iron law of oligarchy

- Kleptocracy

- Meritocracy

- Military dictatorship

- Minoritarianism

- Nepotism

- Netocracy

- Oligopoly

- Oligarchical collectivism

- Parasitism

- Plutocracy

- Political family

- Power behind the throne

- The Power Elite (1956 book by C. Wright Mills)

- Polyarchy

- Stratocracy

- Synarchism

- Theocracy

- Timocracy

References

the concept of oligarchy can be fruitfully applied not only to places like Singapore, Colombia, Russia, and Indonesia, but also to the contemporary United States.

- "Oligarchy". education.nationalgeographic.org. National Geographic. Retrieved 21 July 2023.

Further reading

- Aslund, Anders (2005), "Comparative Oligarchy: Russia, Ukraine and the United States", CASE Network Studies and Analyses No. 296 (PDF), Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, doi:10.2139/ssrn.1441910, S2CID 153769623

- Gordon, Daniel (2010). "Hiring Law Professors: Breaking the Back of an American Plutocratic Oligarchy". Widener Law Journal. 19: 1–29. SSRN 1412783.

- Hollingsworth, Mark; Lansley, Stewart (2010). Londongrad: From Russia with Cash: The Inside Story of the Oligarchs. Fourth Estate. ISBN 978-0007356379.

- Hudson, Michael (2023). The Collapse of Antiquity: Greece and Rome as Civilization's Oligarchic Turning Point. Islet. ISBN 978-3949546129.

- J. M. Moore, ed. (1986). Aristotle and Xenophon on democracy and oligarchy. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520029095.

- Ostwald, M. (2000), Oligarchia: The Development of a Constitutional Form in Ancient Greece (Historia Einzelschirften; 144). Stuttgart: Steiner, ISBN 3515076808.

- Ramseyer, J. Mark; Rosenbluth, Frances McCall (1998). The Politics of Oligarchy: Institutional Choice in Imperial Japan. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521636490.

- Tabachnick, David; Koivukoski, Toivu (2012). On Oligarchy: Ancient Lessons for Global Politics. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-1442661165.

- Whibley, Leonard (1896). Greek oligarchies, their character and organisations. G. P. Putnam's Sons.

- Winters, Jeffrey A. (2011). Oligarchy. Northwestern University, Illinois: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1107005280.

External links

Media related to Oligarchies at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Oligarchies at Wikimedia Commons

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oligarchy

No comments:

Post a Comment