The Pony Express was an American express mail service that used relays of horse-mounted riders. It operated from April 3, 1860, to October 26, 1861, between Missouri and California. It was operated by the Central Overland California and Pikes Peak Express Company.

During its 18 months of operation, the Pony Express reduced the time for messages to travel between the east and west US coast to about 10 days. It became the west's most direct means of east–west communication before the first transcontinental telegraph was established (October 24, 1861), and was vital for tying the new U.S. state of California with the rest of the United States.

Despite a heavy subsidy, the Pony Express was not a financial success and went bankrupt in 18 months, when a faster telegraph service was established. Nevertheless, it demonstrated that a unified transcontinental system of communications could be established and operated year-round. When replaced by the telegraph, the Pony Express quickly became romanticized and became part of the lore of the American West. Its reliance on the ability and endurance of hardy riders and fast horses was seen as evidence of rugged American individualism of the frontier times.

Inception and founding

The idea of having a fast mail route to the Pacific Coast was prompted largely by California's newfound prominence and its rapidly growing population. After gold was discovered there in 1848, thousands of prospectors, investors, and businessmen made their way to California, at that time a new territory of the U.S. By 1850, California entered the Union as a free state. By 1860, the population had grown to 380,000.[1] The prospect of California and its national role became the source of bitter partisan debate in Congress.[2] The demand for a faster way to get the mail and other communications to and from this westernmost state became even greater as the American Civil War approached.[3]

William Russell, Alexander Majors, and William B. Waddell were the three founders of the Pony Express. They were already in the freighting and drayage business. At the peak of the operations, they employed 6,000 men, owned 75,000 oxen, thousands of wagons, and warehouses, plus a sawmill, a meatpacking plant, a bank, and an insurance company.[4]

Russell was a prominent businessman, well respected among his peers and the community.[5] Waddell was co-owner of the firm Morehead, Waddell & Co. In 1859, C.R. Morehead took the proposal for the Pony Express to President Buchanan. After Morehead was bought out and moved to Leavenworth to enter the mercantile business, Waddell merged his company with Russell's, changing the name to Waddell & Russell. In 1855, they took on a new partner, Alexander Majors, and founded the company of Russell, Majors & Waddell.[6] They held government contracts for delivering army supplies to the western frontier, and Russell had a similar idea for contracts with the U.S. government for fast mail delivery.[7]

By using a short route and mounted riders rather than traditional stagecoaches, they proposed to establish a fast mail service between St. Joseph, Missouri, and Sacramento, California, with letters delivered in 10 days, which many said was impossible. The initial price was set at $5 per 1⁄2 ounce (14 g), then $2.50, and by July 1861 to $1. The initial price was 25000% higher than the price of mail through the normal mail service, which was $0.02.[8] The founders of the Pony Express hoped to win an exclusive government mail contract, but that did not come about.

Russell, Majors, and Waddell organized and put together the Pony Express in two months in the winter of 1860. The undertaking assembled 80 riders, 184 stations, 400 horses, and several hundred personnel during January and February 1861.[9]

Majors was a religious man and resolved "by the help of God" to overcome all difficulties. He presented each rider with a special-edition Bible and required this oath,[10][11] which they were also required to sign.[12]

I, ... , do hereby swear, before the Great and Living God, that during my engagement, and while I am an employee of Russell, Majors, and Waddell, I will, under no circumstances, use profane language, that I will drink no intoxicating liquors, that I will not quarrel or fight with any other employee of the firm, and that in every respect I will conduct myself honestly, be faithful to my duties, and so direct all my acts as to win the confidence of my employers, so help me God."

Operation

In 1860, the roughly 186 Pony Express stations were about 10 to 15 miles (16 to 24 km) apart along the Pony Express route.[9] At each station, the express rider would change to a fresh horse, get a bite to eat, and would only the mail pouch called a mochila (from the Spanish for pouch or backpack) with him.

The employers stressed the importance of the pouch. They often said that, if it came to be, the horse and rider should perish before the mochila did. The mochila was thrown over the saddle and held in place by the weight of the rider sitting on it. Each corner had a cantina, or pocket. Bundles of mail were placed in these cantinas, which were padlocked for safety. The mochila could hold 20 pounds (9 kg) of mail along with the 20 pounds (9 kg) of material carried on the horse.[16] Eventually, everything except one revolver and a water sack was removed, allowing for a total of 165 pounds (75 kg) on the horse's back. Riders, who could not weigh over 125 pounds (57 kg), changed about every 75–100 miles (120–160 km), and rode day and night. In emergencies, a given rider might ride two stages back to back, over 20 hours on a quickly moving horse.

Whether riders tried crossing the Sierra Nevada in winter is unknown, but they certainly crossed central Nevada. By 1860, a telegraph station was in Carson City, Nevada Territory. The riders received $125 a month as pay. As a comparison, the wage for unskilled labor at the time was about $0.43–$1 per day, and for semi-skilled laborers like bricklayers and carpenters was usually less than $2 per day.[17]

Alexander Majors, one of the founders of the Pony Express, had acquired more than 400 horses for the project. He selected horses from around the west, paying an average of $200.[18] These averaged about 14.2 hands (58 inches, 147 cm) high and 900 pounds (410 kg)[19] each; thus, the name pony was appropriate, even if not strictly correct in all cases.

Pony Express route

Beginning at St. Joseph, Missouri, the approximately 1,900-mile-long (3,100 km) route[20] roughly followed the Oregon and California Trails to Fort Bridger in Wyoming, and then the Mormon Trail (known as the Hastings Cutoff) to Salt Lake City, Utah. From there, it followed the Central Nevada Route to Carson City, Nevada Territory, before passing over the Sierra and reaching to Sacramento, California.[21] From there mail was transferred to boats to go downriver to San Francisco.

by William Henry Jackson

~ Courtesy the Library of Congress ~

The Pony Express mail route, April 3, 1860 – October 24, 1861; reproduction of Jackson illustration issued to commemorate the 100th anniversary of Pony Express founding on April 3, 1960. Reproduction of Jackson's map issued by the Union Pacific Railroad Company.

The route started at St. Joseph, Missouri, on the Missouri River, and then followed what is modern-day U.S. Highway 36 (the Pony Express Highway) to Marysville, Kansas, where it turned northwest following Little Blue River to Fort Kearny in Nebraska. Through Nebraska, it followed the Great Platte River Road, cutting through Gothenburg, Nebraska, clipping the edge of Colorado at Julesburg; and passing Courthouse Rock, Chimney Rock, and Scotts Bluff, before arriving first at Fort Laramie and then Fort Caspar (Platte Bridge Station) in Wyoming. From there, it followed the Sweetwater River, passing Independence Rock, Devil's Gate, and Split Rock, through South Pass to Fort Bridger and then south to Salt Lake City, Utah. From Salt Lake City, it generally followed the Central Nevada Route blazed in 1859 by Captain James H. Simpson of the Corps of Topographical Engineers. This route roughly follows today's US 50 across Nevada and Utah. It crossed the Great Basin, the Utah-Nevada Desert, and the Sierra Nevada near Lake Tahoe before arriving in Sacramento. Mail was transferred and sent by steamer down the Sacramento River to San Francisco. On a few instances when the steamer was missed, riders took the mail by horseback to Oakland, California.[citation needed]

Stations

Along the long and arduous route used by the Pony Express, 190 stations were used.[22] The stations and station keepers were essential to the successful, timely, and smooth operation of the Pony Express mail system. The stations were often fashioned out of existing structures, several of them located in military forts, while others were built anew in remote areas where living conditions were basic.[23] The route was divided into five divisions.[24] To maintain the rigid schedule, 157 relay stations were located from 5 to 25 miles (8 to 40 km) apart, as the terrain would allow. At each "swing station", riders would exchange their tired mounts for fresh ones, while "home stations" provided room and board for the riders between runs. This technique allowed the mail to be moved across the continent in record time. Each rider rode about 75 miles (120 km) per day.[25]

Pony Express Stations[26]

|

|---|

First journeys

Westbound

The first westbound Pony Express trip left St. Joseph on April 3, 1860, and arrived 10 days later in Sacramento, California, on April 14. These letters were sent under cover from the east to St. Joseph, and never directly entered the U.S. mail system. Today, only a single letter is known to exist from the inaugural westbound trip from St. Joseph to Sacramento.[27] It was delivered in an envelope embossed with postage (depicted below) that was first issued by the U.S. Post Office in 1855.[28]

The messenger delivering the mochila from New York and Washington, DC, missed a connection in Detroit and arrived in Hannibal, Missouri, two hours late. The railroad cleared the track and dispatched a special locomotive called Missouri with a one-car train to make the 206-mile (332 km) trek across Missouri in a record 4 hours and 51 minutes, an average of 40 miles per hour (64 km/h).[29] It arrived at Olive and 8th Street, a few blocks from the company's new headquarters in a hotel at Patee House at 12th and Penn Street, St. Joseph, and the company's nearby stables on Penn Street. The first pouch contained 49 letters, five private telegrams, and some papers for San Francisco and intermediate points.[30]

St. Joseph Mayor M. Jeff Thompson, William H. Russell, and Alexander Majors gave speeches before the mochila was handed off. The ride began at about 7:15 pm. The St. Joseph Gazette was the only newspaper included in the bag.

The identity of the first rider has long been in dispute. The St. Joseph Weekly West (April 4, 1860) reported Johnson William Richardson was the first rider.[31] Johnny Fry is credited in some sources as the rider. Nonetheless, the first westbound rider carried the pouch across the Missouri River ferry to Elwood, Kansas. The first horse-ridden leg of the Express was only about 1⁄2 mile (800 m) from the Express stables/railroad area to the Missouri River ferry at the foot of Jules Street. Reports indicated that horse and rider crossed the river. In later rides, the courier crossed the river without a horse and picked up his mount at a stable on the other side.[citation needed]

The first westbound mochila reached Sacramento, on April 14, at 1:00 am.[32]

Eastbound

The first eastbound Pony Express trip left Sacramento on April 3, 1860, and arrived at its destination 10 days later in St. Joseph, Missouri. From St. Joseph, letters were placed in the U.S. mails for delivery to eastern destinations. Only two letters are known to exist from the inaugural eastbound trip.[33]

As the Pony Express mail service existed only briefly in 1860 and 1861, few examples of Pony Express mail survive. Contributing to the scarcity of Pony Express mail is that the cost to send a 1⁄2-ounce (14 g) letter was $5.00[34] at the beginning (equivalent to $150 in 2021[35], or 21⁄2 days of semi-skilled labor[17]). By the end of the Pony Express, the price had dropped to $1.00 per 1⁄2 ounce but even that was considered expensive to mail one letter. Only 250 known examples of Pony Express mail remain.[27]

Postmarks

Various postmarks were added to the mail to be carried by the Pony Express at the point of departure.

Fastest mail service

William Russell, senior partner of Russell, Majors, and Waddell, and one of the biggest investors in the Pony Express, used the 1860 presidential election, of Abraham Lincoln, as a way to promote the Pony Express and how fast it could deliver the U.S. Mail. This was an important event because just four years earlier, in the prior election, it took months to get news of James Buchanan’s win.[37][38] The election of Lincoln was important because the newly-named president would have to take the country into the Civil War.[37] Prior to the election, Russell hired extra riders to ensure that fresh riders and relay horses were available along the route. On November 7, 1860, a Pony Express rider departed Fort Kearny, Nebraska Territory (the end of the eastern telegraph line) with the election results. Riders briskly traversed the route, over snow-covered trails to Fort Churchill, Nevada Territory (the end of the western telegraph line). California's newspapers received word of Lincoln's election only 7 days and 17 hours after the East Coast papers, an "unrivaled feat at the time".[39]

Attacks

The Paiute War was a minor series of raids and ambushes initiated by American expansion into the territory of the Paiute Indian tribe in Nevada, which resulted in the disruption of mail services of the Pony Express. It took place from May through June 1860, though sporadic violence continued for a period afterward.[citation needed] In the brief history of the Pony Express, only once did the mail not go through. After completing eight weekly trips from both Sacramento and Saint Joseph, the Pony Express was forced to suspend mail services because of the outbreak of the Paiute Indian War in May 1860.[citation needed]

About 6,000 Paiutes in Nevada had suffered during a winter of fierce blizzards that year. By spring, the whole tribe was ready to embark on a war, except for the Paiute chief named Numaga. For three days, Numaga fasted and argued for peace.[41] Meanwhile, a raiding party attacked Williams Station, a Pony Express station[42] located on the then Carson River under present-day Lake Lahontan (reservoir), not to be confused with the large endorheic Pleistocene lake of the same name (Lake Lahontan). One account says the raid was a deliberate attempt to provoke war. Another says the raiders had heard that men at the station had kidnapped two Paiute women, and fighting broke out when they went to investigate and free the women. Either way, the war party killed five men and the station was burned.[43]

During the following weeks, other isolated incidents occurred when Whites in the Paiute country were ambushed and killed. The Pony Express was a special target. Seven other express stations were also attacked; 16 employees were killed, and around 150 express horses were either stolen or driven off. Those who worked at the stations had no one around, possibly for miles, to help defend against the attacks, making working at the stations one of the deadliest jobs in the whole operation.[44] The Paiute War cost the Pony Express company about $75,000 in livestock and station equipment, not to mention the loss of life. In June of that year, the Paiute uprising had been ended through the intervention of U.S. troops, after which four delayed mail shipments from the East were finally brought to San Francisco on June 25, 1860.[45]

During this brief war, one Pony Express mailing, which left San Francisco on July 21, 1860, did not immediately reach its destination. That mail pouch (mochila) did not reach St. Joseph and subsequently New York until almost two years later.[citation needed]

Famous riders

In 1860, riding for the Pony Express was difficult work – riders had to be tough and lightweight. An advertisement allegedly read, "Wanted: Young, skinny, wiry fellows not over eighteen. Must be expert riders, willing to risk death daily. Orphans preferred", but one historian, Joseph Nardone, claims that it is a hoax (dating no earlier than 1902), as no one has found the ad in contemporary newspaper archives.[46]

The Pony Express had an estimated 80 riders traveling east or west along the route at any given time. In addition, about 400 other employees were used, including station keepers, stock tenders, and route superintendents. Many young men applied; Waddell and Majors could have easily hired riders at low rates, but instead offered $100 a month – a handsome sum for that time.[47] Author Mark Twain described the riders in his travel memoir Roughing It as: "... usually a little bit of a man". Though the riders were small, lightweight, generally teenaged boys, they came to be seen as heroes of the American West.[25] There was no systematic list of riders kept by the company,[48] but a partial list has been compiled by Raymond and Nancy Settle in their Saddles & Spurs (1972).[49]

James Butler “Wild Bill” Hickok never worked as a rider and only worked as a stocktender for the Pony Express.[50]

First riders

"Billy" Richardson, Johnny Fry,

Charles Cliff, Gus Cliff

The identity of the first westbound rider to depart St. Joseph has been disputed, but currently most historians have narrowed it down to either Johnny Fry or Billy Richardson.[31][15][51][9] Both Expressmen were hired at St. Joseph for A. E. Lewis' Division, which ran from St. Joseph to Seneca, Kansas, a distance of 80 miles (130 km). They covered at an average speed of 12+1⁄2 miles per hour (20 km/h), including all stops.[52] Before the mail pouch was delivered to the first rider on April 3, 1860, time was taken out for ceremonies and several speeches. First, Mayor M. Jeff Thompson gave a brief speech on the significance of the event for St. Joseph. Then William H. Russell and Alexander Majors addressed the gala crowd about how the Pony Express was just a "precursor" to the construction of a transcontinental railroad. At the conclusion of all the speeches, around 7:15 pm, Russell turned the mail pouch over to the first rider. A cannon fired, the large assembled crowd cheered, and the rider dashed to the landing at the foot of Jules Street, where the ferry boat Denver, under a full head of steam, alerted by the signal cannon, waited to carry the horse and rider across the Missouri River to Elwood, Kansas Territory.[53][54] On April 9 at 6:45 pm, the first rider from the east reached Salt Lake City, Utah. Then, on April 12, the mail pouch reached Carson City, Nevada Territory, at 2:30 pm. The riders raced over the Sierra Nevada, through Placerville, California, and on to Sacramento. Around midnight on April 14, 1860, the first mail pouch was delivered by the Pony Express to San Francisco. With it was a letter of congratulations from President Buchanan to California Governor Downey along with other official government communications, newspapers from New York, Chicago, and St. Louis, and other important mail to banks and commercial houses in San Francisco. In all, 85 pieces of mail were delivered on this first trip.[55]

James Randall is credited as "the first eastbound rider" from the San Francisco Alta telegraph office, since he was on the steamship Antelope to go to Sacramento.[56] Mail for the Pony Express left San Francisco at 4:00 pm, carried by horse and rider to the waterfront, and then on by steamboat to Sacramento, where it was picked up by the Pony Express rider. At 2:45 am, William (Sam) Hamilton was the first Pony Express rider to begin the journey from Sacramento. He rode all the way to Sportsman Hall Station, where he gave his mochila filled with mail to Warren Upson.[57] A California Registered Historical Landmark plaque at the site reads:

This was the site of Sportsman's Hall, also known as the Twelve-Mile House. The hotel was operated in the late 1850s and 1860s by John and James Blair. A stopping place for stages and teams of the Comstock, it became a relay station of the central overland Pony Express. Here, at 7:40 am, April 4, 1860, Pony rider William (Sam) Hamilton, riding in from Placerville, handed the Express mail to Warren Upson who, two minutes later, sped on his way eastward.

— Plaque at Sportsman Hall

William Cody

Probably more than any other rider in the Pony Express, William Cody (better known as Buffalo Bill) epitomizes the legend and the folklore, be it fact or fiction, of the Pony Express.[58][59] Numerous stories have been told of young Cody's adventures as a Pony Express rider, though his accounts may have been fabricated or exaggerated.[60] At age 15, Cody was on his way west to California when he met Pony Express agents along the way and signed on with the company. Cody helped in the construction of several way-stations. Thereafter, he was employed as a rider and was given a short 45-mile (72 km) delivery run from the township of Julesburg, which lay to the west. After some months, he was transferred to Slade's Division in Wyoming, where he is said to have made the longest nonstop ride from Red Buttes Station to Rocky Ridge Station and back when he found that his relief rider had been killed. This trail of 322 miles (518 km) was completed in 21 hours and 40 minutes, and 21 horses were required.[25] On one occasion when he is said to have carried mail, he unintentionally ran into an Indian war party, but managed to escape. Cody was present for many significant chapters in early western history, including the gold rush, the building of the railroads, and cattle herding on the Great Plains. A career as a scout for the Army under General Phillip Sheridan following the Civil War earned him his nickname and established his notoriety as a frontiersman.[61][62][63]

Robert Haslam

"Pony Bob" Haslam was among the most brave, resourceful, and best-known riders of the Pony Express. He was born in January 1840 in London, United Kingdom, and came to the United States as a teenager. Haslam was hired by Bolivar Roberts, helped build the stations, and was given the mail run from Friday's Station at Lake Tahoe to Buckland's Station near Fort Churchill, 75 miles (121 km) to the east.[citation needed]

His greatest ride, 120 miles (190 km) in 8 hours and 20 minutes while wounded, was an important contribution to the fastest trip ever made by the Pony Express. The mail carried Lincoln's inaugural address. Indian problems in 1860 led to Haslam's record-breaking ride. He had received the eastbound mail (probably the May 10 mail from San Francisco) at Friday's Station. When he reached Buckland's Station, his relief rider was so badly frightened over the Indian threat that he refused to take the mail. Haslam agreed to take the mail all the way to Smith's Creek for a total distance of 190 miles (310 km) without a rest. After a rest of 9 hours, he retraced his route with the westbound mail, where at Cold Springs, he found that Indians had raided the place, killing the station keeper and running off all of the stock. On the ride, he was shot through the jaw with an Indian arrow, losing three teeth.[64][self-published source] Finally, he reached Buckland's Station, making the 380-mile (610 km) round trip the longest on record.[25]

Pony Bob continued to work as a rider for Wells Fargo and Company after the Civil War, scouted for the U.S. Army well into his 50s, and later accompanied his good friend "Buffalo Bill" Cody on a diplomatic mission to negotiate the surrender of Chief Sitting Bull in December 1890. He drifted in and out of public mention, but died in Chicago during the winter of 1912 (age 72) in deep poverty after suffering a stroke. Buffalo Bill paid for his friend's headstone at Mount Greenwood Cemetery (111 Street and Sacramento) on Chicago's far south side.[65]

Jack Keetley

Jack Keetley was hired by A. E. Lewis for his division at the age of 19 and put on the run from Marysville to Big Sandy. He was one of those who rode for the Pony Express during the entire 19 months of its existence.

Jack Keetley's longest ride, upon which he doubled back for another rider, ended at Seneca, where he was taken from the saddle sound asleep. He had ridden 340 miles (550 km) in 31 hours without stopping to rest or eat.[66][67] After the Pony Express was disbanded, Keetley went to Salt Lake City, where he engaged in mining. He died there on October 12, 1912, where he was also buried.[68]

In 1907, Keetley wrote the following letter (excerpt):

Alex Carlyle was the first man to ride the Pony Express out of St. Joe. He was a nephew of the superintendent of the stage line to Denver, called the "Pike's Peak Express". The superintendent's name was Ben Ficklin. Carlyle was a consumptive, and could not stand the hardships, and retired after about two months' trial, and died within about six months after retiring. John Frye was the second rider, and I was the third, and Gus Cliff was the fourth.

I made the longest ride without a stop, only to change horses. It was said to be 300 miles and was done a few minutes inside of twenty-four hours. I do not vouch for the distance being correct, as I only have it from the division superintendent, A.E. Lewis, who said that the distance given was taken by his English roadometer which was attached to the front wheel of his buggy which he used to travel over his division with, and which was from St. Joe to Fort Kearney.[67]

— Jack Keetley

Billy Tate

Billy Tate was a 14-year-old Pony Express rider who rode the express trail in Nevada near Ruby Valley. During the Paiute uprising of 1860, he was chased by a band of Paiute Indians on horseback and was forced to retreat into the hills behind some big rocks, where he killed seven of his assailants in a shoot-out before being killed himself. His body was found riddled with arrows, but was not scalped, a sign that the Paiutes honored their enemy.[69]

Major Howard Egan

Egan emigrated to the United States from Ireland with his parents in the early 1830s. While living in Massachusetts, he joined the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (also known as "Mormons"). He was with the Pioneer Party of 1847 that journeyed to the west to modern day Salt Lake City, Utah. At the start of the Pony Express, he was appointed Superintendent of the Division from Salt Lake City to Robert’s Creek which is in present day Nevada. Egan filled in when others couldn’t ride. After the Pony Express, he ranched and became involved with the court system in Utah.[70]

Horses

At the west end of the Pony Express route in California, W.W. Finney purchased 100 head of short-coupled stock called "California horses", while A.B. Miller purchased another 200 native ponies in and around the Great Salt Lake Valley. The horses were ridden quickly between stations, an average distance of 15 miles (24 km), and then were relieved and a fresh horse was exchanged for the one that just arrived from its strenuous run.[citation needed]

During his route of 80 to 100 miles (130 to 160 km), a Pony Express rider would change horses 8 to 10 times. The horses were ridden at a fast trot, canter, or gallop, around 10 to 15 miles per hour (16 to 24 km/h) and at times they were driven to full gallop at speeds up to 25 miles per hour (40 km/h). Horses of the Pony Express were purchased in Missouri, Iowa, California, and some western U.S. territories.[citation needed]

The various types of horses ridden by riders of the Pony Express included Morgans and thoroughbreds, which were often used on the eastern end of the trail. Mustangs were often used on the western (more rugged) end of the mail route.[71]

Saddle

This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2022) |

In 1844, years before the Pony Express came to St. Joseph, Israel Landis opened a small saddle and harness shop there. His business expanded as the town grew, and when the Pony Express came to town, Landis was the ideal candidate to produce saddles for the newly founded Pony Express. Because Pony Express riders rode their horses at a quick pace over a distance of 10 miles (16 km) or more between stations, every consideration was made to reduce the overall weight the horse had to carry. To help reduce this load, special lightweight saddles were designed and crafted. Using less leather and fewer metallic and wood components, they fashioned a saddle that was similar in design to the regular stock saddle generally in use in the West at that time.[72][page needed]

The mail pouch was a separate component to the saddle that made the Pony Express unique. Standard mail pouches for horses were never used because of their size and shape, as detaching and attaching it from one saddle to the other was time-consuming, causing undue delay in changing mounts. With many stops to make, the delayed time at each station would accumulate to appreciable proportions. To get around this difficulty, a mochila (a covering of leather) was thrown over the saddle. The saddle horn and cantle projected through holes that were specially cut to size in the mochila. Attached to the broad leather skirt of the mochila were four cantinas, or box-shaped hard leather compartments, where letters were carried on the journey.[72][page needed]

Closing

During its brief time in operation, the Pony Express delivered about 35,000 letters between St. Joseph and Sacramento.[73] Although the Pony Express proved that the central/northern mail route was viable, Russell, Majors, and Waddell did not get the contract to deliver mail over the route. The contract was instead awarded to Jeremy Dehut in March 1861, who had taken over the southern, congressionally favored Butterfield Overland Mail Stage Line. The so-called "Stagecoach King", Ben Holladay, acquired the Russell, Majors, and Waddell stations for his stagecoaches.[citation needed]

Shortly after the contract was awarded, the start of the American Civil War caused the stage line to cease operation. From March 1861, the Pony Express ran mail only between Salt Lake City and Sacramento. The Pony Express announced its closure on October 26, 1861, two days after the transcontinental telegraph reached Salt Lake City and connected Omaha, Nebraska, and Sacramento. Other telegraph lines connected points along the line and other cities on the east and west coasts.[74]

Despite the subsidy, the Pony Express was a financial failure. It grossed $90,000 and lost $200,000.[75]

In 1866, after the Civil War was over, Holladay sold the Pony Express assets along with the remnants of the Butterfield Stage to Wells Fargo for $1.5 million.[citation needed]

Legacy

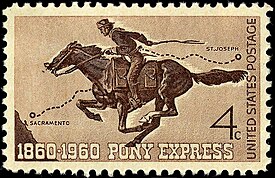

Postage stamps

In 1869, the United States Post Office issued the first U.S. postage stamp to depict an actual historic event, and the subject chosen was the Pony Express. Until then, only the faces of George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, and Andrew Jackson were found on the face of U.S. postage.[76] Sometimes mistaken for an actual stamp used by the Pony Express, the "Pony Express Stamp" issue was released in 1869 (8 years after the Pony Express service had ended) to honor the men who rode the long and sometimes dangerous journeys and to commemorate the service they provided for the nation. In 1940 and 1960, commemorative stamps were issued for the 80th and 100th anniversaries of the Pony Express, respectively.

Pony Express Rider, issue of 1869 |

Pony Express 80th-anniversary issue of 1940 |

Pony Express 100th-anniversary issue of 1960 |

Historical research

This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2022) |

The foundation of accountable Pony Express history rests in the few tangible areas where records, papers, letters, and mailings have yielded the most historical evidence. Until the 1950s, most of what was known about the short-lived Pony Express was the product of a few accounts, hearsay, and folklore, generally true in their overall aspects, but lacking in verification in many areas for those who wanted to explore the history surrounding the founders, the various riders, and station keepers, or who were interested in stations or forts along the Pony Express route.[citation needed]

The most complete books on the Pony Express are The Story of the Pony Express by Raymond and Mary Settle and Saddles and Spurs by Roy Bloss. Settle's account is unique, as he was the first writer and historical researcher to make use of Pony Express founder William B. Waddell's papers, now in a collection at the Huntington Library in San Marino, California. Mr. Settle wrote in the mid-1950s. Mr. Bloss was a writer for the Pony Express Centennial. While Settle's work was published generally without his annotations and notes, the writer's background here is unique and Settle does have an excellent bibliography. When Settle prepared to publish his well-researched account, he had a good volume of footnotes, citations prepared, but the editors chose not to use most of them. Instead, they opted for a less expensive approach to print and publish and released an accurate, but simplified account. Settle was not pleased with this new and sudden development, as he put much time and effort into the annotations. Yet, the account Settle wrote was and is a definitive one and is considered the best account on the history of the Pony Express among many historians.[77][failed verification][original research?]

National Historic Trail

| Pony Express National Historic Trail | |

|---|---|

Pony Express Trail Map | |

| Location | California, Colorado, Kansas, Missouri, Nebraska, Nevada, Utah, Wyoming, US |

| Governing body | National Trails System |

| Website | www |

The Pony Express route was designated the Pony Express National Historic Trail August 3, 1992, by an act of Congress. Its route goes through eight states and includes substantial sections of land managed by the Bureau of Land Management in California, Colorado, Nevada, Utah, and Wyoming.[citation needed]

The public can auto-tour the route, visit interpretive sites and museums, and hike, bike, or horseback ride various trail segments.[78] Sites open to public visitation along the trail include the Sand Mountain Recreation Area in Nevada; automobile access to a backcountry byway (the Pony Express Trail National Back Country Byway) along the route itself, Boyd Station and Simpson Springs Campground in Utah; and the Little Sandy Crossing in Wyoming. In total, approximately 120 historic sites along the trail may eventually be open to the public, including 50 stations or station ruins.[79]

The National Pony Express Association is a nonprofit, volunteer-led historical organization. Its purpose is to preserve the original Pony Express trail and to continue the memory and importance of Pony Express in American history in partnership with the National Park Service, Pony Express Trail Association, and Oregon-California Trails Association.[citation needed]

Other commemorations

From 1866 until 1889, the Pony Express logo was used by stagecoach and freight company Wells Fargo, which provided secure mail service. Wells Fargo used the Pony Express logo for its guard and armored-car services.[citation needed] The logo continued to be used when other companies took over the security business into the 1990s. Since 2001, the Pony Express logo is no longer used for security businesses, since the business has been sold.[80]

In June 2006, the United States Postal Service announced it had trademarked "Pony Express" along with "Air Mail".[81][82]

April 3, 2010 was the Pony Express's 150th anniversary. Located in St. Joseph, Missouri, the Patee House Museum, which was the Pony Express's headquarters, hosted events celebrating the anniversary.[83]

On April 14, 2015, Google released a playable doodle game celebrating their 155th anniversary.[84]

In popular culture

The continued remembrance and popularity of the Pony Express can be linked to Buffalo Bill Cody, his autobiographies, and his Wild West Show. The first book dedicated solely to the Pony Express was not published until 1900.[85] However, in his first autobiography, published in 1879, Cody claims to have been an Express rider.[86][87] While this claim has recently come under dispute,[85] his show became the "primary keeper of the pony legend" when it premiered as a scene in the Wild West Show.[85]

Film

- The Pony Express (1925)[88]

- Winds of the Wasteland(1936)[89]

- Frontier Pony Express (1939)[90]

- "Pony Express Days" (short) (1940)[91]

- Pony Post (1940)[92]

- Plainsman and the Lady (1946)[93]

- Pony Express (1953)[94]

- Last of the Pony Riders (1953)[95]

- The Pony Express Rider (1976)[96]

- Pony Express Rider (1996)[97]

- Spirit of the Pony Express (2012)[98]

Television

- The Range Rider (1951–1953) season-one episode "The Last of the Pony Express"[99]

- Crossroad Avenger (1953)

- Pony Express (1959–1960)[100]

- Bonanza (1959–1973) season seven, two-part episode "Ride the Wind"[101][102]

- The Young Riders (1989–1992)

- Into the West (2005)

- My Little Pony: Equestria Girls (2013)

See also

- Cursus publicus

- Joseph Alfred Slade

- Örtöö

- Pony Express Museum

- Pony Express mochila

- Postage stamps and postal history of the United States

- Royal Road

References

"Richard Frajola, Philatelist (Postmarks enhanced)". Archived from the original on April 7, 2013. Retrieved December 10, 2012.

Bibliography

- Angel, Myron, ed. (1881). History of Nevada. Oakland, California: Thompson and West. Retrieved September 14, 2012.

- Beasley, Delilah Leontium (1919). The Negro trail blazers of California. Times Mirror Printing and Binding House.

- Bradley, Glenn Danford (1913). The story of the Pony Express. A. C. McClurg & Co. Retrieved June 15, 2014.

- Chapman, Arthur (1971). The pony express: the record of a romantic adventure in business. G. P. Putnam's Sons. ISBN 9780815403913.

- "Pony Express". Century Magazine. New York. XXXIV. 1898.

- Cody, William F. & Visscher, William Lightfoot (1917). Life and Adventures of 'Buffalo Bill' Colonel William F. Cody. Stanton and Van Vliet.

- Corbett, Christopher (2003). Orphans Preferred: The Twisted Truth and Lasting Legend of the Pony Express. New York: Broadway Books. ISBN 9780767906920.

- Egan, Ferol (1972). The Pony Express: The Record of a Romantic Adventure in Business. University of Nevada Press. p. 316. ISBN 0-87417-097-4.[clarification needed]

- Frajola, Richard C.; Kramer, George J. & Walske, Steven C. (2005). The Pony Express, A Postal History (PDF). The Philatelic Foundation. ISBN 0-911989-03-X. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 10, 2022.

- Godfrey, Anthony (1994). "Pony Express National Historic Trail Historic Resource Study". National Park Service. Retrieved February 20, 2012.

- Majors, Alexander & Cody, William (1873). The Pony Express: Bringing Mail to the American West. The Western Miner and Financier. ISBN 9781604130287.[clarification needed]

- McNesse, Tim (2009). The Pony Express: Bringing Mail to the American West. Infobase Publishing. p. 138. ISBN 9781438119847.

- Michno, Gregory (2007). The Deadliest Indian War in the West: The Snake Conflict, 1864–1868. Caxton Press. p. 157. ISBN 978-0-87004-460-1. Retrieved September 15, 2012.

- Peters, Arthur K. (1996). Seven Trails West. Abbeville Press. ISBN 1-55859-782-4.

- Reinfeld, Fred (1973). Pony Express. Macmillan / Bison Books. ISBN 9780803257863.

- Root, George A. & Hickman, Russell K. (February 1946). "Part IV-The Platte Route-Concluded. The Pony Express and Pacific Telegraph". Kansas Historical Quarterly. 14 (1): 36–92. Retrieved December 10, 2012.

- Settle, Raymond & Settle, Mary (1949). Empire on Wheels. Stanford University Press. p. 153.

- Settle, Raymond & Settle, Mary (1955). Saddles and Spurs: The Pony Express Saga. Stackpole.

- Settle, Raymond & Settle, Mary (1972). Saddles and Spurs: The Pony Express Saga. Bison Books. ISBN 9780803257658. Retrieved December 10, 2012.

- Thompson, Don (March 20, 2005). "Historian finds Pony Express ad". U-T San Diego. Associated Press. Archived from the original on March 13, 2012. Retrieved September 16, 2012.

Further reading

- Fike, Richard E. & Headley, Joh W. (1979). The Pony Express Stations of Utah in Historical Perspective. Washington, D.C.: Bureau of Land Management, Utah.

- Luff, John Nicholas (1902). The Postage Stamps of the United States. Scott Stamp & Coin Company.

- Visscher, William Lightfoot (1908). A Thrilling and Truthful History of the Pony Express: Or, Blazing the Westward Way. Rand McNally.

- Carter, Kate B (1952). Riders of the pony express. Chicago : A. C. McClurg.

External links

- Spirit of the Pony Express (Documentary)

- Pony Express National Historic Trail (National Park Service)

- Pony Express National Historic Trail (Bureau of Land Management)

- "Inventory of the Waddell F. Smith Papers,1939–1976". Online Archive of California.

- Hartnagle, Ernie & Hartnagle, Elaine. "The Correct Identity of Billy Richardson, the Pony Express Rider". Archived from the original on May 9, 2008.

- "Hollenberg Pony Express Station". kansastravel.org.

- The True Story of Billy Tate Pony Express Rider Who died at 14-years-old

- Visit the USA

- Pony Express

- American companies disestablished in 1861

- American companies established in 1860

- Central Overland Route

- Historic trails and roads in California

- Historic trails and roads in Kansas

- Historic trails and roads in Missouri

- Historic trails and roads in Nebraska

- Historic trails and roads in Nevada

- Historic trails and roads in Utah

- Historic trails and roads in Wyoming

- National Historic Trails of the United States

- Units of the National Landscape Conservation System

- Wells Fargo

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pony_Express

No comments:

Post a Comment