A touchstone is a small tablet of dark stone such as slate or lydite, used for assaying precious metal alloys. It has a finely grained surface on which soft metals leave a visible trace.[1]

History

The touchstone was used during the Harappa period of the Indus Valley civilization ca. 2600–1900 BC for testing the purity of soft metals.[2] It was also used in Ancient Greece.[3]

The touchstone allowed anyone to easily and quickly determine the purity of a metal sample. This, in turn, led to the widespread adoption of gold as a standard of exchange. Although mixing gold with less expensive materials was common in coinage, using a touchstone one could easily determine the quantity of gold in the coin, and thereby calculate its intrinsic worth.

Operation

Drawing a line with gold on a touchstone will leave a visible trace. Because different alloys of gold have different colours (see gold), the unknown sample can be compared to samples of known purity. This method has been used since ancient times. In modern times, additional tests can be done. The trace will react in different ways to specific concentrations of nitric acid or aqua regia, thereby identifying the quality of the gold: 24 karat gold is not affected but 14 karat gold will show chemical activity.

See also

References

- Bisht, R. S. (1982). "Excavations at Banawali: 1974–77". In Possehl, Gregory L. (ed.). Harappan Civilization: A Contemporary Perspective. New Delhi: Oxford and IBH Publishing Co. pp. 113–124.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Touchstone_(assaying_tool)

Bath Stone is an oolitic limestone comprising granular fragments of calcium carbonate. Originally obtained from the Combe Down and Bathampton Down Mines under Combe Down, Somerset, England. Its honey colouring gives the World Heritage City of Bath, England its distinctive appearance. An important feature of Bath Stone is that it is a 'freestone', so-called because it can be sawn or 'squared up' in any direction, unlike other rocks such as slate, which form distinct layers.

Bath Stone has been used extensively as a building material throughout southern England, for churches, houses, and public buildings such as railway stations.

Some quarries are still in use, but the majority have been converted to other purposes or are being filled in.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bath_stone

Penrhyn Slate Quarry, in 1852 | |

| Location | |

|---|---|

Location in Gwynedd | |

| Location | near Bethesda |

| County | Gwynedd (formerly Caernarfonshire) |

| Country | Wales |

| Coordinates | 53.167°N 4.067°W SH 61840 65347 |

| Production | |

| Products | Slate |

| Type | Quarry |

| Greatest depth | 1,200 feet (370 metres) |

| History | |

| Opened | pre-1570 |

| Owner | |

| Company | Welsh Slate Ltd. |

| Website | www |

| Year of acquisition | 2007 |

| Railways | |

| History | |

| Opened | 25 June 1801 |

| Closed | 24 July 1962 |

| Technical | |

| Track gauge | 1 ft 10+3⁄4 in (578 mm) |

The Penrhyn quarry is a slate quarry located near Bethesda, North Wales. At the end of the nineteenth century it was the world's largest slate quarry; the main pit is nearly 1 mile (1.6 km) long and 1,200 feet (370 metres) deep, and it was worked by nearly 3,000 quarrymen. It has since been superseded in size by slate quarries in China, Spain and the USA. Penrhyn is still Britain's largest slate quarry but its workforce is now nearer 200.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Penrhyn_quarry

| The Flintstones | |

|---|---|

Title card used during season 1 | |

| Genre | Animated sitcom |

| Created by | |

| Developed by |

|

| Directed by |

|

| Voices of | |

| Theme music composer | Hoyt Curtin[1] |

| Opening theme | "Rise and Shine" (instrumental) (first two seasons and the first two episodes of season 3) "Meet the Flintstones" (remainder of the show's run) |

| Ending theme | "Rise and Shine" (instrumental) (first two seasons and the first two episodes of season 3) "Meet the Flintstones" (remainder of the show's run) "Open Up Your Heart (and Let the Sunshine In)" (two episodes in season 6) |

| Composers |

|

| Country of origin | United States |

| Original language | English |

| No. of seasons | 6 |

| No. of episodes | 166 (list of episodes) |

| Production | |

| Producers |

|

| Editors |

|

| Running time | 25 minutes |

| Production company | Hanna-Barbera Productions |

| Release | |

| Original network | ABC |

| Picture format | NTSC |

| Audio format | Monaural |

| Original release | September 30, 1960 – April 1, 1966 |

| Related | |

| The Pebbles and Bamm-Bamm Show Cave Kids (spin-off) | |

The Flintstones is an American animated sitcom produced by Hanna-Barbera Productions. The series takes place in a romanticized Stone Age setting and follows the activities of the titular family, the Flintstones, and their next-door neighbors, the Rubbles. It was originally broadcast on ABC from September 30, 1960, to April 1, 1966, and was the first animated series to hold a prime-time slot on television.[2]

The show follows the lives of Fred and Wilma Flintstone and their pet dinosaur Dino, eventually seeing the addition of baby Pebbles. Barney and Betty Rubble are their neighbors and best friends. They adopt a super-strong baby named Bamm-Bamm and acquire a pet hopparoo called Hoppy.

Producers William Hanna and Joseph Barbera, who had earned seven Academy Awards for Tom and Jerry, and their staff faced a challenge in developing a thirty-minute animated program with one storyline that fit the parameters of family-based domestic situation comedy of the era. After considering several settings and selecting the Stone Age, one of several inspirations was The Honeymooners (in itself traceable to The Bickersons and Laurel and Hardy), which Hanna freely praised as one of the finest comedies on television. The show's animation required a balance of visual as well as verbal storytelling that the studio created and others imitated.[3]

The continuing popularity of The Flintstones rests heavily on its juxtaposition of modern everyday concerns in the Stone Age setting.[4][5] The Flintstones was the most financially successful and longest-running network animated television series for three decades, until The Simpsons surpassed it in 1997.[6] In 2013, TV Guide ranked The Flintstones the second-greatest TV cartoon of all time (after The Simpsons).[7]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Flintstones#Characters

Tiles are usually thin, square or rectangular coverings manufactured from hard-wearing material such as ceramic, stone, metal, baked clay, or even glass. They are generally fixed in place in an array to cover roofs, floors, walls, edges, or other objects such as tabletops. Alternatively, tile can sometimes refer to similar units made from lightweight materials such as perlite, wood, and mineral wool, typically used for wall and ceiling applications. In another sense, a tile is a construction tile or similar object, such as rectangular counters used in playing games (see tile-based game). The word is derived from the French word tuile, which is, in turn, from the Latin word tegula, meaning a roof tile composed of fired clay.

Tiles are often used to form wall and floor coverings, and can range from simple square tiles to complex or mosaics. Tiles are most often made of ceramic, typically glazed for internal uses and unglazed for roofing, but other materials are also commonly used, such as glass, cork, concrete and other composite materials, and stone. Tiling stone is typically marble, onyx, granite or slate. Thinner tiles can be used on walls than on floors, which require more durable surfaces that will resist impacts.

Global production of ceramic tiles, excluding roof tiles, was estimated to be 12.7 billion m2 in 2019.[1]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tile

Mineral wool is any fibrous material formed by spinning or drawing molten mineral or rock materials such as slag and ceramics.[1]

Applications of mineral wool include thermal insulation (as both structural insulation and pipe insulation), filtration, soundproofing, and hydroponic growth medium.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mineral_wool

Staddle stones (variations include steddle stones)[a] were originally used as supporting bases for granaries, hayricks, game larders, etc. The staddle stones lifted the granaries above the ground thereby protecting the stored grain from vermin and water seepage. In Middle English staddle or stadle is stathel, from Old English stathol, a foundation, support or trunk of a tree. They can be mainly found in Great Britain, Norway ("stabbur"), Galicia and Asturias (Northern Spain).

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Staddle_stones

| Cotswolds | |

|---|---|

Castle Combe, a Cotswolds village with buildings made of Cotswold stone | |

Location of the Cotswolds within England | |

| Location | England |

| Coordinates | 51°48′N 2°2′W |

| Area | 2,038 km2 (787 sq mi) |

| Established | 1966 |

| Named for | cot + wold, 'sheep enclosure in rolling hillsides' |

| Website | www |

The Cotswolds (/ˈkɒtswoʊldz/, /-wəldz/[1]) is a region in central-southwest England, along a range of rolling hills that rise from the meadows of the upper Thames to an escarpment above the Severn Valley and Evesham Vale.

The area is defined by the bedrock of Jurassic limestone that creates a type of grassland habitat rare in the UK and that is quarried for the golden-coloured Cotswold stone.[2] The predominantly rural landscape contains stone-built villages, towns, and stately homes and gardens featuring the local stone.

Designated as an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) in 1966,[3] the Cotswolds covers 787 square miles (2,038 km2) making it the largest AONB.[4] It is the third largest protected landscape in England after the Lake District and Yorkshire Dales national parks.[5] Its boundaries are roughly 25 miles (40 km) across and 90 miles (140 km) long, stretching southwest from just south of Stratford-upon-Avon to just south of Bath near Radstock. It lies across the boundaries of several English counties; mainly Gloucestershire and Oxfordshire, and parts of Wiltshire, Somerset, Worcestershire, and Warwickshire. The highest point of the region is Cleeve Hill at 1,083 ft (330 m),[6] just east of Cheltenham.

The hills give their name to the Cotswold local government district, formed on 1 April 1974, which is within the county of Gloucestershire. Its main town is Cirencester, where the Cotswold District Council offices are located.[7] The population of the 450-square-mile (1,200 km2) District was about 83,000 in 2011.[8][9] The much larger area referred to as the Cotswolds encompasses nearly 800 square miles (2,100 km2),[10] over five counties: Gloucestershire, Oxfordshire, Warwickshire, Wiltshire, and Worcestershire.[11] The population of the Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty was 139,000 in 2016.[12]

History

The largest excavation of Jurassic period echinoderm fossils, including of rare and previously unknown species, occurred at a quarry in the Cotswolds in 2021.[13][14] There is evidence of Neolithic settlement from burial chambers on Cotswold Edge, and there are remains of Bronze and Iron Age forts.[15] Later the Romans built villas, such as at Chedworth,[16] settlements such as Gloucester, and paved the Celtic path later known as Fosse Way.[17]

During the Middle Ages, thanks to the breed of sheep known as the Cotswold Lion, the Cotswolds became prosperous from the wool trade with the continent, with much of the money made from wool directed towards the building of churches. The most successful era for the wool trade was 1250–1350; much of the wool at that time was sold to Italian merchants. The area still preserves numerous large, handsome Cotswold Stone "wool churches". The affluent area in the 21st century has attracted wealthy Londoners and others who own second homes there or have chosen to retire to the Cotswolds.[11]

Etymology

The name Cotswold is popularly believed to mean the "sheep enclosure in rolling hillsides",[18][19] incorporating the term, wold, meaning hills. Compare also the Weald from the Saxon/German word Wald meaning 'forest'. However, the English Place-Name Society has for many years accepted that the term Cotswold is derived from Codesuualt of the 12th century or other variations on this form, the etymology of which was given, 'Cod's-wold', which is 'Cod's high open land'.[20] Cod was interpreted as an Old English personal name, which may be recognised in further names: Cutsdean, Codeswellan, and Codesbyrig, some of which date back to the eighth century AD.[21] It has subsequently been noticed that "Cod" could derive philologically from a Brittonic female cognate "Cuda", a hypothetical mother goddess in Celtic mythology postulated to have been worshipped in the Cotswold region.[22][23]

Geography

The spine of the Cotswolds runs southwest to northeast through six counties, particularly Gloucestershire, west Oxfordshire and southwestern Warwickshire. The northern and western edges of the Cotswolds are marked by steep escarpments down to the Severn valley and the Warwickshire Avon. This feature, known as the Cotswold escarpment, or sometimes the Cotswold Edge, is a result of the uplifting (tilting) of the limestone layer, exposing its broken edge.[24] This is a cuesta, in geological terms. The dip slope is to the southeast.

On the eastern boundary lies the city of Oxford and on the west is Stroud. To the southeast, the upper reaches of the Thames Valley and towns such as Lechlade, Tetbury, and Fairford are often considered to mark the limit of this region. To the south the Cotswolds, with the characteristic uplift of the Cotswold Edge, reach beyond Bath, and towns such as Chipping Sodbury and Marshfield share elements of Cotswold character.

The area is characterised by attractive small towns and villages built of the underlying Cotswold stone (a yellow oolitic limestone).[24] This limestone is rich in fossils, particularly of fossilised sea urchins. Cotswold towns include Bourton-on-the-Water, Broadway, Burford, Chalford, Chipping Campden, Chipping Norton, Cricklade, Dursley, Malmesbury, Minchinhampton, Moreton-in-Marsh, Nailsworth, Northleach, Painswick, Stow-on-the-Wold, Stroud, Tetbury, Witney, Winchcombe and Wotton-under-Edge. In addition, much of Box lies in the Cotswolds. Bath, Cheltenham, Cirencester, Gloucester, Stroud, and Swindon are larger urban centres that border on, or are virtually surrounded by, the Cotswold AONB.

The town of Chipping Campden is notable for being the home of the Arts and Crafts movement, founded by William Morris at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries.[25] William Morris lived occasionally in Broadway Tower, a folly, now part of a country park.[26] Chipping Campden is also known for the annual Cotswold Olimpick Games, a celebration of sports and games dating back to the early 17th century.[27]

Of the nearly 800 square miles (2,100 km2) of the Cotswolds, roughly eighty percent is farmland.[28] There are over 3,000 miles (4,800 km) of footpaths and bridleways. There are also 4,000 miles (6,400 km) of historic stone walls.[10]

Economy

A 2017 report on employment within the Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty, stated that the main sources of income were real estate, renting and business activities, manufacturing and wholesale & retail trade repairs. Some 44% of residents were employed in these sectors.[12] Agriculture is also important. Some 86% of the land in the AONB is used for this purpose. The primary crops include barley, beans, rape seed oil and wheat, while the raising of sheep is also important; cows and pigs are also reared. The livestock sector has been declining since 2002, however.[29]

According to the 2011 Census data for the Cotswolds,[30] the wholesale and retail trade was the largest employer (15.8% of the workforce), followed by education (9.7%) and health and social work (9.3%). The report also indicates that a relatively higher proportion of residents were working in agriculture, forestry and fishing, accommodation and food services as well as in professional, scientific and technical activities.[31]

Unemployment in the Cotswold District was among the lowest in the country.[32] A report in August 2017 showed only 315 unemployed persons, a slight decrease of five from a year earlier.[33]

Tourism

Tourism is a significant part of the economy. The Cotswold District area alone gained over £373 million from visitor spending on accommodation, £157 million on local attractions and entertainments, and about £100m on travel in 2016.[34] In the larger Cotswolds Tourism area, including Stroud, Cheltenham, Gloucester and Tewkesbury,[32] tourism generated about £1 billion in 2016, providing 200,000 jobs. Some 38 million day visits were made to the Cotswold Tourism area that year.

Many travel guides direct tourists to Chipping Campden, Stow-on-the-Wold, Bourton-on-the-Water,[35] Broadway, Bibury, and Stanton.[36][37] Some of these locations can be very crowded at times. Roughly 300,000 people visit Bourton per year, for example, with about half staying for a day or less.[38]

The area also has numerous public walking trails and footpaths that attract visitors, including the 93-mile (150 km) Cotswold Way (part of the National Trails system) from Bath to Chipping Campden.[39]

Housing development

In August 2018, the final decision was made for a Local Plan that would lead to the building of nearly 7,000 additional homes by 2031, in addition to over 3,000 already built. Areas for development include Cirencester, Bourton-on-the-Water, Down Ampney, Fairford, Kemble, Lechlade, Northleach, South Cerney, Stow-on-the-Wold, Tetbury and Moreton-in-Marsh. Some of the money received from developers will be earmarked for new infrastructure to support the increasing population.[40]

Cotswold stone

Cotswold stone is a yellow oolitic Jurassic limestone. This limestone is rich in fossils, particularly of fossilised sea urchins. When weathered, the colour of buildings made or faced with this stone is often described as honey or golden.[41]

The stone varies in colour from north to south, being honey-coloured in the north and north east of the region, as shown in Cotswold villages such as Stanton and Broadway; golden-coloured in the central and southern areas, as shown in Dursley and Cirencester; and pearly white in Bath.[42]

The rock outcrops at places on the Cotswold Edge; small quarries are common. The exposures are rarely sufficiently compact to be good for rock-climbing, but an exception is Castle Rock, on Cleeve Hill, near Cheltenham. Because of the rapid expansion of the Cotswolds in order for nearby areas to capitalize on increased house prices, well-known ironstone villages, such as Hook Norton, have even been claimed by some to be in the Cotswolds despite lacking key features of Cotswolds villages such as Cotswold stone, and are instead built using a deep red/orange ironstone, known locally as Hornton Stone.[43]

In his 1934 book English Journey, J. B. Priestley made this comment[44] about Cotswold buildings made of the local stone.

The truth is that it has no colour that can be described. Even when the sun is obscured and the light is cold, these walls are still faintly warm and luminous, as if they knew the trick of keeping the lost sunlight of centuries glimmering about them

Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty

The Cotswolds were designated as an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) in 1966, with an expansion on 21 December 1990 to 1,990 square kilometres (768 sq mi). In 1991, all AONBs were measured again using modern methods, and the official area of the Cotswolds AONB was increased to 2,038 square kilometres (787 sq mi). In 2000, the government confirmed that AONBs have the same landscape quality and status as National Parks.[45]

The Cotswolds AONB, which is the largest in England and Wales, stretches from the border regions of South Warwickshire and Worcestershire, through West Oxfordshire and Gloucestershire, and takes in parts of Wiltshire and of Bath and North East Somerset in the south.[46] Gloucestershire County Council is responsible for sixty-three percent of the AONB.[47]

The Cotswolds Conservation Board has the task of conserving and enhancing the AONB. Established under statute in 2004 as an independent public body, the Board carries out a range of work from securing funding for 'on the ground' conservation projects, to providing a strategic overview of the area for key decision makers, such as planning officials. The Board is funded by Natural England and the seventeen local authorities that are covered by the AONB.[48] The Cotswolds AONB Management Plan 2018–2023 was adopted by the Board in September 2018.[49]

The landscape of the AONB is varied, including escarpment outliers, escarpments, rolling hills and valleys, enclosed limestone valleys, settled valleys, ironstone hills and valleys, high wolds and high wold valleys, high wold dip-slopes, dip-slope lowland and valleys, a Low limestone plateau, cornbrash lowlands, farmed slopes, a broad floodplain valley, a large pastoral lowland vale, a settled unwooded vale, and an unwooded vale.[50]

While the beauty of the Cotswolds AONB is intertwined with that of the villages that seem almost to grow out of the landscape, the Cotswolds were primarily designated an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty for the rare limestone grassland habitats as well as the old growth beech woodlands that typify the area. These habitat areas are also the last refuge for many other flora and fauna, with some so endangered that they are protected under the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981. Cleeve Hill, and its associated commons, is a fine example of a limestone grassland and it is one of the few locations where the Duke of Burgundy butterfly may still be found in abundance.[51]

A June 2018 report stated that the AONB receives "23 million visitors a year, the third largest of any protected landscape".[52] Earlier that year, Environment secretary Michael Gove announced that a panel would be formed to consider making some of the AONBs into National Parks. The review will file its report in 2019.[53] In April 2018, the Cotswolds Conservation Board had written to Natural England "requesting that consideration be given to making the Cotswolds a National Park", according to Liz Eyre, Chairman.[54] This has led to some concern as stated by one member of the Cotswold District Council, "National Park designation is a significant step further and raises the prospect of key decision making powers being taken away from democratically elected councillors".[55] In other words, Cotswold District Council would no longer have the authority to grant and refuse housing applications.[56]

The uniqueness and value of the Cotswolds is shown in the fact that five European Special Areas of Conservation, three national nature reserves and more than 80 Sites of Special Scientific Interest are within the Cotswolds AONB.[57]

The Cotswold Voluntary Wardens Service was established in 1968 to help conserve and enhance the area, and now has more than 300 wardens.[58]

The Cotswold Way is a long-distance footpath, just over 100 miles (160 km) long, running the length of the AONB, mainly on the edge of the Cotswold escarpment with views over the Severn Valley and the Vale of Evesham.[59]

In September 2020, the Cotswolds AONB rebranded itself as the "Cotswolds National Landscape", using a proposed name replacement for "Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty".[60][61]

Places of interest

Pictured is the Garden of Sudeley Castle at Winchcombe. The present structure was built in the 15th century and may be on the site of a 12th-century castle.[62] It is north of the spa town of Cheltenham which has much Georgian architecture of some merit. Further south, towards Tetbury, is the ancient fortress known as Beverston Castle, founded in 1229 by Maurice de Gaunt. In the same area is Calcot Manor, a manor house with origins in about 1300 as a tithe barn.[63]

Tetbury Market House was built in 1655.[64] During the Middle Ages, Tetbury became an important market for Cotswold wool and yarn. Chavenage House is an Elizabethan-era manor house 1.5 miles (2.4 km) northwest of Tetbury.[65] Chedworth Roman Villa, where several mosaic floors are on display, is near the Roman road known as the Fosse Way, 8 miles (13 km) north of the important town of Corinium Dobunnorum (Cirencester). Cirencester Abbey was founded as an Augustinian monastery in 1117[66] and Malmesbury Abbey was one of the few English houses with a continual history from the 7th century through to the Dissolution of the Monasteries.[67]

An unusual house in this area is Quarwood, a Victorian Gothic house in Stow-on-the-Wold. The grounds, covering 42 acres (17 ha), include parkland, fish ponds, paddocks, garages, woodlands and seven cottages.[68] Another is Woodchester Mansion, an unfinished, Gothic revival mansion house in Woodchester Park near Nympsfield.[69] Newark Park is a Grade I listed country house of Tudor origins near the village of Ozleworth, Wotton-under-Edge. The house sits in an estate of 700 acres (300 ha)[70] at the southern end of the Cotswold escarpment.

Another of the many manor houses in the area, Owlpen Manor in the village of Owlpen in the Stroud district, is also Tudor and also Grade I listed. Further north, Broadway Tower is a folly on Broadway Hill, near the village of Broadway, Worcestershire. To the south of the Cotswolds is Corsham Court, a country house in a park designed by Capability Brown in the town of Corsham, 3 miles (5 km) west of Chippenham, Wiltshire.

Top attractions

According to users of the worldwide TripAdvisor travel site, in 2018 the following were among the best attractions in the Cotswolds:[71]

- Walks With Hawks, Cheltenham

- Cotswolds Distillery, Stourton

- Cotswold Falconry Centre, Moreton-in-Marsh

- Mechanical Music Museum, Northleach

- Chavenage House, Tetbury

- Tewkesbury Abbey, Tewkesbury

- Gloucestershire Warwickshire Steam Railway, Cheltenham

- Gloucester Cathedral, Gloucester

- The Royal Gardens at Highgrove, Tetbury

- Jet Age Museum, Gloucester

- Cotswold Wildlife Park, Burford

- Hook Norton Brewery, Hook Norton

Transport

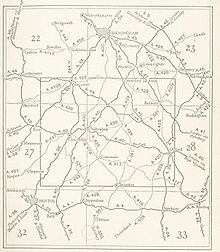

The Cotswolds lie between the M5, M40 and M4 motorways. The main A-roads through the area are:

- the A46: Bath – Stroud – Cheltenham – Evesham;

- the A419: Swindon – Cirencester – Stroud;

- the A417: Lechlade – Cirencester – Gloucester;

- the A429: Malmesbury – Cirencester – Stow-on-the-Wold – Moreton-in-Marsh;

- the A44: Chipping Norton – Moreton-in-Marsh – Evesham;

- the A40: Oxford – Burford – Cheltenham – Gloucester.

These all roughly follow the routes of ancient roads, some laid down by the Romans, such as Ermin Way and the Fosse Way.

There are local bus services across the area, but some are infrequent.

The River Thames flows from the Cotswolds and is navigable from Inglesham and Lechlade-on-Thames downstream to Oxford. West of Inglesham. the Thames and Severn Canal and the Stroudwater Navigation connected the Thames to the River Severn; this route is mostly disused nowadays but several parts are in the process of being restored.

Railways

The area is bounded by two major rail routes: in the south by the main Bristol–Bath–London line (including the South Wales main line) and in the west by the Bristol–Birmingham main line. In addition, the Cotswold line runs through the Cotswolds from Oxford to Worcester, and the Golden Valley line runs across the hills from Swindon via Stroud to Gloucester, carrying fast and local services.

Mainline rail services to the big cities run from railway stations such as Bath, Swindon, Oxford, Cheltenham, and Worcester. Mainline trains run by Great Western Railway to London Paddington also are available from Kemble station near Cirencester, Kingham station near Stow-on-the-Wold, Charlbury station, and Moreton-in-Marsh station.

Additionally, there is the Gloucestershire Warwickshire Railway, a steam heritage railway over part of the closed Stratford–Cheltenham line, running from Cheltenham Racecourse through Gotherington, Winchcombe, and Hayles Abbey Halt to Toddington and Laverton. The preserved line has been extended to Broadway.

In culture

The Cotswold region has inspired several notable English composers. In the early 1900s, Herbert Howells and Ivor Gurney used to take long walks together over the hills, and Gurney urged Howells to make the landscape, including the nearby Malvern Hills, the inspiration for his future work. In 1916, Howells wrote his first major piece, the Piano Quartet in A minor, inspired by the magnificent view of the Malverns; he dedicated it to "the hill at Chosen (Churchdown) and Ivor Gurney who knows it".[72] Another contemporary of theirs, Gerald Finzi, lived in nearby Painswick.

Gustav Holst, who was born in Cheltenham, spent much of his early years playing the organ in Cotswold village churches, including at Cranham, after which village he titled his tune for In the Bleak Midwinter. He also called his Symphony in F major, Op. 8 H47 The Cotswolds.

Holst's friend, the composer Ralph Vaughan Williams, was born at Down Ampney in the Cotswolds and, though he moved to Surrey as a boy, he gave the name of his native village to the tune for Come Down, O Love Divine. He also composed his opera Hugh the Drover from 1913 to 1924, which depicts life in a Cotswold village and incorporates local folk melodies. In 1988, the 6th symphony (Op. 109) of composer Derek Bourgeois was titled "A Cotswold Symphony".

The Cotswolds are a popular location for filming scenes for movies and television programmes.[73][74] The film Better Things (2008), directed by Duane Hopkins, is set in a small Cotswold village. The fictional detective Agatha Raisin lives in the fictional village of Carsely in the Cotswolds.

Other movies filmed in the Cotswolds or nearby, at least in part, include some of the Harry Potter series (Gloucester Cathedral), Bridget Jones's Diary (Snowshill), Pride and Prejudice (Cheltenham Town Hall), and Braveheart (Cotswold Farm Park).[75] In 2014, some scenes of the 2016 movie Alice Through the Looking Glass were filmed at the Gloucester Docks just outside the Cotswold District; some scenes for the 2006 movie Amazing Grace were also filmed at the Docks.[76]

The television series Father Brown was almost entirely filmed in the Cotswolds. Scenes and buildings in Sudeley Castle was often featured in the series.[77] The vicarage in Blockley was used for the main character's residence and the Anglican St Peter and St Paul church was the Roman Catholic St Mary's in the series.[73] Other filming locations included Guiting Power, the former hospital in Moreton-in-Marsh, the Winchcombe railway station, Lower Slaughter, and St Peter's Church in Upper Slaughter.[78][79]

In the 2010s, BBC TV series Poldark, the location for Ross Poldark's family home "Trenwith" is Chavenage House, Tetbury, which is open to the public.[80]

Many exterior shots of village life in the Downton Abbey TV series were filmed in Bampton, Oxfordshire.[75] Other filming locations in that county included Swinbrook, Cogges, and Shilton.[81][82]

The city of Bath hosted crews that filmed parts of the movies Vanity Fair, Persuasion, Dracula, and The Duchess.[83] Gloucester and other places in Gloucestershire, some within the Area of Natural Beauty, have been a popular location for filming period films and television programmes over the years. Gloucester Cathedral has been particularly popular.[84]

The sighting of peregrine falcons in the landscape of the Cotswolds is mentioned in The Peregrine by John Alec Baker.

The television documentary agriculture-themed series Clarkson's Farm were filmed at various locations around Chipping Norton.

See also

References

The Cotswolds are quite simply a hiker's paradise. Miles upon miles of public pathways and bridleways to explore.

- SoGlos. "18 movie and television filming locations in Gloucestershire". SoGlos. Archived from the original on 26 June 2018. Retrieved 26 June 2018.

Further reading

- Brace, Catherine. "Looking back: the Cotswolds and English national identity, c. 1890–1950." Journal of Historical Geography 25.4 (1999): 502-516.

- Brace, Catherine. "A pleasure ground for the noisy herds? Incompatible encounters with the Cotswolds and England, 1900–1950." Rural History 11.1 (2000): 75-94.

- Briggs, Katharine Mary. The folklore of the Cotswolds (BT Batsford Limited, 1974).

- Hilton, R. H. "The Cotswolds and Regional History." History Today (July 1953) 3#7 pp 490–499.

- Verey, David Cecil Wynter. The buildings of England: Gloucestershire. I. The Cotswolds (Penguin Books, 1979).

External links

- National Character Area profile – Natural England

- Cotswolds Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty – Cotswolds Conservation Board

- Cotswolds Tourism Partnership

- Independent tourist guides:

- Cotswolds

- Hills of Gloucestershire

- Hills of Oxfordshire

- Hills of Somerset

- Hills of Warwickshire

- Hills of Wiltshire

- Hills of Worcestershire

- Protected areas of Gloucestershire

- Protected areas of Oxfordshire

- Protected areas of Somerset

- Protected areas of Warwickshire

- Protected areas of Wiltshire

- Protected areas of Worcestershire

- Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty in England

- Natural regions of England

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cotswolds#Cotswold_stone

Sharpening stones, or whetstones, are used to sharpen the edges of steel tools such as knives through grinding and honing.

Such stones come in a wide range of shapes, sizes, and material compositions. They may be flat, for working flat edges, or shaped for more complex edges, such as those associated with some wood carving or woodturning tools. They may be composed of natural quarried material or from man-made material. They come in various grades, which refer to the grit size of the abrasive particles in the stone. (Grit size is given as a number, which indicates the spatial density of the particles; a higher number denotes a higher density and therefore smaller particles, which give a finer finish to the surface of the sharpened object.) Stones intended for use on a workbench are called bench stones, while small, portable ones, whose size makes it hard to draw large blades uniformly over them, especially “in the field,” are called pocket stones.

Often whetstones are used with a cutting fluid to enhance sharpening and carry away swarf. Those used with water for this purpose are often called water stones or waterstones, those used with oil sometimes oil stones or oilstones.

Whetstones will wear away with use, typically in the middle. Tools sharpened in this groove will develop undesirable curves on the blade. In order to prevent this, a whetstone may be levelled out with sandpaper or a levelling or flattening stone.[1]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sharpening_stone

Stone sealing is the application of a surface treatment to products constructed of natural stone to retard staining and corrosion.[1] All bulk natural stone is riddled with interconnected capillary channels that permit penetration by liquids and gases. This is true for igneous rock types such as granite and basalt, metamorphic rocks such as marble and slate, and sedimentary rocks such as limestone, travertine, and sandstone. These porous channels act like a sponge, and capillary action draws in liquids over time, along with any dissolved salts and other solutes. Very porous stone, such as sandstone absorb liquids relatively quickly, while denser igneous stones such as granite are significantly less porous; they absorb smaller volumes, and more slowly, especially when absorbing viscous liquids.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stone_sealer

Stamped concrete is concrete that has been imprinted, or that is patterned, textured, or embossed to resemble brick, slate, flagstone, stone, tile, wood, or various other patterns and textures. The practice of stamping concrete for various purposes began with the ancient Romans. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, concrete was sometimes stamped with contractor names and years during public works projects, but by the late twentieth century the term "stamped concrete" came to refer primarily to decorative concrete produced with special modern techniques for use in patios, sidewalks, driveways, pool decks, and interior flooring.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stamped_concrete

This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2021) |

A spindle whorl is a disc or spherical to whorled object fitted onto the spindle to increase and maintain the speed of the spin. Historically, whorls have been made of materials like amber, antler, bone, ceramic, coral, glass, stone, metal (iron, lead, lead alloy), and wood (oak). Local sourced materials have been also used, such as chalk, limestone, mudstone, sandstone, slate, lydite and soapstone.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spindle_whorl

Funerary art in Puritan New England encompasses graveyard headstones carved between c. 1640 and the late 18th century by the Puritans, founders of the first American colonies, and their descendants. Early New England puritan funerary art conveys a practical attitude towards 17th-century mortality; death was an ever-present reality of life,[1] and their funerary traditions and grave art provide a unique insight into their views on death. The minimalist artistry of the early headstone designs reflect a religious doctrine, which largely avoided unnecessary decoration or embellishment.

The earliest Puritan graves in the New England states of Maine, Vermont, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Connecticut and Rhode Island, were usually dug without planning in designated local burial grounds, and sometimes marked with upright slate, sandstone or granite stones containing factual but inelegant inscriptions. Subsequent generations decorated their stone headstones with carvings; most dramatically with depictions of death's head, a stylized skull sometimes with wings or crossed bones.[2]

Later examples show the deceased carried by the wings, supposedly taking their soul to heaven.[3] From the 1690s the imagery becomes less severe, and began to include winged cherubs (known as "soul effigies") who had fuller faces and rounder and more life-sized eyes and mouths.[2] In headstones dating from the Federalist Era, the rise of secularism saw the prominence of urn and willow imagery.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Funerary_art_in_Puritan_New_England

Witches' stones (in Jèrriais: pièrres dé chorchièrs) are flat stones jutting from chimneys in the islands of Jersey and Guernsey.[1]

According to folklore in the Channel Islands, these small ledges were used by witches to rest on as they fly to their sabbats. Householders would provide these platforms to appease witches and avoid their ill favour.

Traditional vernacular architecture in Jersey is in granite and such witches' stones can be seen protruding from many older houses. The real origin of this architectural feature is to protect thatched roofs from seeping water running down the sides of the chimney stack. Thatched roofs being thicker than tiled roofs, the jutting stones would sit snugly on the thatch – as can be seen on the few remaining thatched roofs in Jersey. When thatch began to be generally replaced by pantiles in the 18th century, and later by slates, the witches' stones were left protruding prominently from the chimney stack. This either gave rise to the belief in witches' resting places, or reinforced an existing belief. Fear of witches was widespread in country areas well into the 20th century in Jersey.[citation needed]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Witches%27_stones

Artificial stone is a name for various synthetic stone products produced from the 18th century onward. Uses include statuary, architectural details, fencing and rails, building construction, civil engineering work, and industrial applications such as grindstones.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Artificial_stone

| St Baglan's Church, Llanfaglan | |

|---|---|

St Baglan's Church, Llanfaglan, from the southwest | |

| OS grid reference | SH 455 606 |

| Location | Llanfaglan, Gwynedd |

| Country | Wales |

| Denomination | Church in Wales |

| Website | Friends of Friendless Churches |

| History | |

| Dedication | Baglan ap Dingad (Saint Baglan) |

| Architecture | |

| Functional status | Redundant |

| Heritage designation | Grade I |

| Designated | 29 May 1968 |

| Architectural type | Church |

| Groundbreaking | 13th century (probable) |

| Completed | 1800 |

| Specifications | |

| Materials | Stone, slate roofs |

St Baglan's Church, Llanfaglan, is a redundant church in the parish of Llanfaglan, Gwynedd, Wales. It is designated by Cadw as a Grade I listed building,[1] and is under the care of the Friends of Friendless Churches.[2] It stands in an isolated position in a field some 150 metres (164 yd) from a minor road.[1]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/St_Baglan%27s_Church,_Llanfaglan

The Lenape Stone is a piece of slate found in Bucks County, Pennsylvania in 1872, which appears to depict Native Americans hunting a woolly mammoth. This image, however, seems to have been carved some time after the stone was broken into two; for this and other reasons, it is generally considered an archaeological forgery.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lenape_Stone

| Yellow bullhead | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Siluriformes |

| Family: | Ictaluridae |

| Genus: | Ameiurus |

| Species: | A. natalis

|

| Binomial name | |

| Ameiurus natalis (Lesueur, 1819)

| |

| Synonyms[2] | |

| |

The yellow bullhead (Ameiurus natalis) is a species of bullhead catfish, a ray-finned fish that lacks scales.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yellow_bullhead

| Helvella lacunosa | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Fungi |

| Division: | Ascomycota |

| Class: | Pezizomycetes |

| Order: | Pezizales |

| Family: | Helvellaceae |

| Genus: | Helvella |

| Species: | H. lacunosa

|

| Binomial name | |

| Helvella lacunosa (Afzel.)

| |

| Helvella lacunosa | |

|---|---|

| smooth hymenium | |

| cap is convex | |

| hymenium attachment is not applicable | |

| stipe is bare | |

| spore print is white | |

| ecology is saprotrophic or mycorrhizal | |

| edibility: not recommended | |

Helvella lacunosa, known as the slate grey saddle or fluted black elfin saddle in North America, simply as the elfin saddle in Britain, is an ascomycete fungus of the family Helvellaceae. It is one of the most common species in the genus Helvella.[1] The mushroom is readily identified by its irregularly shaped grey cap, fluted stem, and fuzzy undersurfaces. It is usually found in Eastern North America and in Europe, near deciduous and coniferous trees in summer and autumn.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Helvella_lacunosa

| Slate-throated whitestart | |

|---|---|

| |

| Myioborus miniatus aurantiacus in Panama | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Parulidae |

| Genus: | Myioborus |

| Species: | M. miniatus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Myioborus miniatus (Swainson, 1827)

| |

| |

| Range of M. miniatus | |

The slate-throated whitestart or slate-throated redstart (Myioborus miniatus) is a species of bird in the family Parulidae native to Central and South America.[1][2]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Slate-throated_whitestart

iPod Touch (5th generation) in blue | |

| Developer | Apple Inc. |

|---|---|

| Manufacturer | Apple Inc. |

| Product family | iPod |

| Type | Mobile device |

| Release date |

|

| Lifespan | October 11, 2012 – July 15, 2015 |

| Discontinued | July 15, 2015 |

| Operating system | Original: iOS 6.0 Last: iOS 9.3.5, released August 25, 2016 |

| System on a chip | Dual-core Apple A5 |

| CPU | ARM dual-core Cortex-A9 Apple A5 1 GHz (underclocked to 800 MHz) |

| Memory | 512 MB DRAM[1] |

| Storage | 16, 32 or 64 GB flash memory |

| Display | 4 in (100 mm) diagonal (16:9 aspect ratio), multi-touch display, LED backlit IPS TFT LCD, 1136×640 px at 326 PPI 800:1 contrast ratio (typical), 500 cd/m2 max. brightness (typical), fingerprint-resistant oleophobic coating |

| Graphics | PowerVR SGX543MP2 |

| Input |

|

| Camera |

|

| Connectivity |

|

| Power | 3.7 V, 3.8 Wh (1030 mAh) rechargeable lithium-ion battery Audio: 40 hours; Video: 8 hours[3][4] |

| Online services | App Store, iTunes Store, iBookstore, iCloud, Passbook - iOS 8 and below, Wallet - iOS 9 only |

| Dimensions | 123.4 mm (4.86 in) H 58.6 mm (2.31 in) W 6.1 mm (0.24 in) D |

| Mass | 88 g (3.1 oz) |

| Predecessor | iPod Touch (4th generation) |

| Successor | iPod Touch (6th generation) |

| Related | iPhone 4S iPhone 5 iPhone 5C iPhone 5S |

| This article is part of a series on the |

| iPod |

|---|

| List of iPod models |

The fifth generation iPod Touch (stylized and marketed as the iPod touch, and colloquially known as the iPod Touch 5G, iPod Touch 5, or iPod 5) was unveiled at Apple's media event alongside the iPhone 5 on September 12, 2012, and was released on October 11, 2012. A mobile device designed and marketed by Apple Inc. with a touchscreen-based user interface, it succeeded the 4th-generation iPod Touch. It is compatible with up to iOS 9.3.5, which was released on August 25, 2016.

Like the iPhone 5, the fifth-generation iPod Touch is a slimmer, lighter model that introduces a higher-resolution, 4-inch screen to the series with 16:9 widescreen aspect ratio, similar to the iPhone 5, 5C, and 5S. Other improvements include support for recording 1080p video and panoramic still photos via the rear camera, an LED flash, Apple's A5 chip (the same chip used in the iPad Mini (1st generation), iPad 2, and iPhone 4S) and support for Apple's Siri.

The fifth-generation iPod Touch was released with more color options than its predecessors. It initially featured with a black screen and slate back and a white screen with five back color options including silver, pink, yellow, blue, and Product Red, however on the release of the iPhone 5S the slate color was changed to space gray and all the other colors remained unchanged.[5]

The device was initially only sold in 32 GB and 64 GB models. The first 16 GB model, introduced on May 30, 2013, was only available in one color combination (black screen with a silver back) and lacks the rear iSight camera, LED flash and the iPod Touch Loop that is included in the 32 GB models.[6] On June 26, 2014, it was replaced with a new 16 GB model that no longer omits the rear camera and full range of color options. The pricing for the iPod Touch had also changed. The 16 GB model is $199 instead of $229, the 32 GB model is $249 instead of $299, and the 64 GB model is $299 instead of $399.[7] The iPod Touch (5th generation) was officially discontinued by Apple on July 15, 2015, with the release of its successor, the iPod Touch (6th generation).

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/IPod_Touch_(5th_generation)

| Gray catbird Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Adult at the Arnold Arboretum, Massachusetts, United States | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Mimidae |

| Genus: | Dumetella C.T. Wood, 1837 |

| Species: | D. carolinensis

|

| Binomial name | |

| Dumetella carolinensis (Linnaeus, 1766)

| |

| |

| Approximate distribution map

Breeding

Migration

Year-round

Nonbreeding

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Genus: | |

The gray catbird (Dumetella carolinensis), also spelled grey catbird, is a medium-sized North American and Central American perching bird of the mimid family. It is the only member of the "catbird" genus Dumetella. Like the black catbird (Melanoptila glabrirostris), it is among the basal lineages of the Mimidae, probably a closer relative of the Caribbean thrasher and trembler assemblage than of the mockingbirds and Toxostoma thrashers.[2][3] In some areas it is known as the slate-colored mockingbird.[4]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gray_catbird

| Black-headed trogon | |

|---|---|

| |

| Near Tulum, Mexico | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Trogoniformes |

| Family: | Trogonidae |

| Genus: | Trogon |

| Species: | T. melanocephalus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Trogon melanocephalus Gould, 1836

| |

| |

The black-headed trogon (Trogon melanocephalus) is a species of bird in the family Trogonidae. It is found in Belize, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, and Nicaragua.[2]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black-headed_trogon

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive. It consists of a mixture of sulfur, carbon (in the form of charcoal) and potassium nitrate (saltpeter). The sulfur and carbon act as fuels while the saltpeter is an oxidizer.[1][2] Gunpowder has been widely used as a propellant in firearms, artillery, rocketry, and pyrotechnics, including use as a blasting agent for explosives in quarrying, mining, building pipelines and road building.

Gunpowder is classified as a low explosive because of its relatively slow decomposition rate and consequently low brisance. Low explosives deflagrate (i.e., burn at subsonic speeds), whereas high explosives detonate, producing a supersonic shockwave. Ignition of gunpowder packed behind a projectile generates enough pressure to force the shot from the muzzle at high speed, but usually not enough force to rupture the gun barrel. It thus makes a good propellant but is less suitable for shattering rock or fortifications with its low-yield explosive power. Nonetheless, it was widely used to fill fused artillery shells (and used in mining and civil engineering projects) until the second half of the 19th century, when the first high explosives were put into use.

Gunpowder is one of the Four Great Inventions of China.[3] Originally developed by the Taoists for medicinal purposes, it was first used for warfare around 904 AD.[4] Its use in weapons has declined due to smokeless powder replacing it, and it is no longer used for industrial purposes due to its relative inefficiency compared to newer alternatives such as dynamite and ammonium nitrate/fuel oil.[5]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gunpowder

Mudrocks are a class of fine-grained siliciclastic sedimentary rocks. The varying types of mudrocks include siltstone, claystone, mudstone, slate, and shale. Most of the particles of which the stone is composed are less than 1⁄16 mm (0.0625 mm; 0.00246 in) and are too small to study readily in the field. At first sight, the rock types appear quite similar; however, there are important differences in composition and nomenclature.

There has been a great deal of disagreement involving the classification of mudrocks. A few important hurdles to their classification include the following:

- Mudrocks are the least understood and among the most understudied sedimentary rocks to date.

- Studying mudrock constituents is difficult due to their diminutive size and susceptibility to weathering on outcrops.

- And most importantly, scientists accept more than one classification scheme.

Mudrocks make up 50% of the sedimentary rocks in the geologic record and are easily the most widespread deposits on Earth. Fine sediment is the most abundant product of erosion, and these sediments contribute to the overall omnipresence of mudrocks.[1] With increased pressure over time, the platey clay minerals may become aligned, with the appearance of parallel layering (fissility). This finely bedded material that splits readily into thin layers is called shale, as distinct from mudstone. The lack of fissility or layering in mudstone may be due either to the original texture or to the disruption of layering by burrowing organisms in the sediment prior to lithification.

From the beginning of civilization, when pottery and mudbricks were made by hand, to now, mudrocks have been important. The first book on mudrocks, Geologie des Argils by Millot, was not published until 1964; however, scientists, engineers, and oil producers have understood the significance of mudrocks since the discovery of the Burgess Shale and the relatedness of mudrocks and oil. Literature on this omnipresent rock-type has been increasing in recent years, and technology continues to allow for better analysis.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mudrock

HP Slate is a small line of HP consumer tablets and All-in-Ones.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HP_Slate

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chinese_nuthatch

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Slate-colored_hawk

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grosbeak

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dutch_rabbit

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Slate_budgerigar_mutation

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nook_HD

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cane_Corso

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Collared_bush_robin

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black_Forest_Trail

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dark-eyed_junco

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black-capped_chickadee

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black_redstart

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Magic_8_Ball

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/White-shouldered_ibis

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/LG_Rumor_(original)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Call_of_Duty#Black_Ops_story_arc

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lhasa_Apso

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Salt_and_pepper

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blackcurrant

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black_helicopter

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black_Star_Line

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plott_Hound

| General information | |

|---|---|

| Architectural style | Neo-romanticism, Neoclassical, Neo-Gothic |

| Location | Miguel Hidalgo, Mexico City, Mexico |

| Elevation | 2,325 metres (7,628 ft) above sea level |

| Current tenants | Museo Nacional de Historia |

| Construction started | c. 1785 |

| Completed | 1864 |

| Height | 220 feet (67 m) |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Eleuterio Méndez, Ramón Rodríguez Arangoiti, Julius Hofmann, Carl Gangolf Kayser, Carlos Schaffer |

| Other designers | Maximilian I of Mexico |

| Official name | Part of the Historic center of Mexico City |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, ii, iii, iv, v |

| Designated | 1987 (11th session) |

| Reference no. | 412 |

| Region | Latin America and the Caribbean |

Chapultepec Castle (Spanish: Castillo de Chapultepec) is located on top of Chapultepec Hill in Mexico City's Chapultepec park. The name Chapultepec is the Nahuatl word chapoltepēc which means "on the hill of the grasshopper". The castle has such unparalleled views and terraces that explorer James F. Elton wrote “it cannot be surpassed in beauty in any part of the world."[1][2] It is located at the entrance to Chapultepec park, at a height of 2,325 metres (7,628 ft) above sea level.[3] The site of the hill was a sacred place for Aztecs, and the buildings atop it have served several purposes during its history, including those of Military Academy, Imperial residence, Presidential residence, observatory, and since February 1939, the National Museum of History.[4] Chapultepec Castle, along with Iturbide Palace, also in Mexico City, are the only royal palaces in North America which were inhabited by monarchs.

It was built during the Viceroyalty of New Spain as a summer house for the highest colonial administrator, the viceroy. It was given various uses, from a gunpowder warehouse to a military academy in 1841. It was remodeled and added to and became the official residence of Emperor Maximilian I of Mexico and his consort Empress Carlota during the Second Mexican Empire (1864–67). In 1882, President Manuel González declared it the official residence of the President. With few exceptions, all succeeding presidents lived there until 1934, when President Lázaro Cárdenas stayed at Los Pinos instead, turning the castle into a museum in 1939.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chapultepec_Castle

| Castle Bravo | |

|---|---|

Time-lapse of the Bravo detonation and subsequent mushroom cloud. | |

| Information | |

| Country | United States |

| Test series | Operation Castle |

| Test site | Bikini Atoll |

| Date | March 1, 1954 |

| Test type | Atmospheric |

| Yield | 15 megatonnes of TNT (63 PJ) |

| Test chronology | |

Castle Bravo was the first in a series of high-yield thermonuclear weapon design tests conducted by the United States at Bikini Atoll, Marshall Islands, as part of Operation Castle. Detonated on March 1, 1954, the device was the most powerful nuclear device detonated by the United States and its first lithium deuteride fueled thermonuclear weapon.[1][2] Castle Bravo's yield was 15 megatonnes of TNT (63 PJ), 2.5 times the predicted 6 megatonnes of TNT (25 PJ), due to unforeseen additional reactions involving lithium-7,[3] which led to the unexpected radioactive contamination of areas to the east of Bikini Atoll. At the time, it was the most powerful artificial explosion in history.

Fallout, the heaviest of which was in the form of pulverized surface coral from the detonation, fell on residents of Rongelap and Utirik atolls, while the more particulate and gaseous fallout spread around the world. The inhabitants of the islands were not evacuated until three days later and suffered radiation sickness. Twenty-three crew members of the Japanese fishing vessel Daigo Fukuryū Maru ("Lucky Dragon No. 5") were also contaminated by the heavy fallout, experiencing acute radiation syndrome. The blast incited a strong international reaction over atmospheric thermonuclear testing.[4]

The Bravo Crater is located at 11°41′50″N 165°16′19″E. The remains of the Castle Bravo causeway are at 11°42′6″N 165°17′7″E.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Castle_Bravo

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1990_Bishop%27s_Castle_earthquake

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Castle_in_the_Sky

Birr Castle (Irish: Caisleán Bhiorra)[1] is a large castle in the town of Birr in County Offaly, Ireland. It is the home of the 7th Earl of Rosse and his family, and as such the residential areas of the castle are not open to the public,[2] though the grounds and gardens of the demesne are publicly accessible, and include a science museum and a café, a reflecting telescope which was the largest in the world for decades and a modern radio telescope.[3]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Birr_Castle

| Goodrich Castle | |

|---|---|

| Herefordshire, England | |

Goodrich Castle, seen from the east | |

Shown within Herefordshire | |

| Coordinates | 51.8761°N 2.6130°W |

| Grid reference | grid reference SO579199 |

| Type | Concentric castle |

| Site information | |

| Owner | English Heritage |

| Controlled by | English Heritage |

| Open to the public | Yes |

| Condition | Ruined |

| Site history | |

| Materials | Sandstone |

Goodrich Castle is a Norman medieval castle ruin north of the village of Goodrich in Herefordshire, England, controlling a key location between Monmouth and Ross-on-Wye. It was praised by William Wordsworth as the "noblest ruin in Herefordshire"[1] and is considered by historian Adrian Pettifer to be the "most splendid in the county, and one of the best examples of English military architecture".[2]

Goodrich Castle was probably built by Godric of Mappestone after the Norman invasion of England, initially as an earth and wooden fortification. In the middle of the 12th century the original castle was replaced with a stone keep, and was then expanded significantly during the late 13th century into a concentric structure combining luxurious living quarters with extensive defences. The success of Goodrich's design influenced many other constructions across England over the following years. It became the seat of the powerful Talbot family before falling out of favour as a residence in late Tudor times.

Held first by Parliamentary and then Royalist forces in the English Civil War of the 1640s, Goodrich was finally successfully besieged by Colonel John Birch in 1646 with the help of the huge "Roaring Meg" mortar, resulting in the subsequent slighting of the castle and its descent into ruin. At the end of the 18th century, however, Goodrich became a noted picturesque ruin and the subject of many paintings and poems; events at the castle provided the inspiration for Wordsworth's famous 1798 poem "We are Seven". By the 20th century the site was a well-known tourist location, now owned by English Heritage and open to the public.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Goodrich_Castle

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nightmare_Castle?wprov=srpw1_30

Conegliano | |

|---|---|

| Città di Conegliano | |

The castle by night |

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conegliano

| Oxenfoord Castle | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | Pathhead, Midlothian, Scotland |

| Coordinates | 55.8786°N 2.9794°W |

| Built | 1782, remodelled 1842 |

| Built for | Sir John Dalrymple, 4th Baronet |

| Architect | Robert Adam, William Burn |

| Architectural style(s) | Castellated |

Listed Building – Category A | |

| Designated | 22 January 1971 |

| Reference no. | LB768 |

| Criteria | Architectural Scenic |

| Designated | 1 July 1987 |

| Reference no. | GDL00307 |

Oxenfoord Castle is a country house in Midlothian, Scotland. It is located 1 kilometre (0.62 mi) north of Pathhead, Midlothian, and 6 kilometres (3.7 mi) south-east of Dalkeith, above the Tyne Water. Originally a 16th-century tower house, the present castle is largely the result of major rebuilding in 1782, to designs by the architect Robert Adam. Oxenfoord was the seat of the Earl of Stair from 1840, and remains in private ownership. It is protected as a category A listed building,[1] while the grounds are included in the Inventory of Gardens and Designed Landscapes in Scotland.[2]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oxenfoord_Castle

Buda (Hungarian pronunciation: [ˈbudɒ]; German: Ofen, Serbo-Croatian: Budim / Будим, Czech and Slovak: Budín, Turkish: Budin) was the historic capital of the Kingdom of Hungary and since 1873 has been the western part of the Hungarian capital Budapest, on the west bank of the Danube. Buda comprises a third of Budapest's total territory and is mostly wooded. Landmarks include Buda Castle, the Citadella, and the president of Hungary's residence, Sándor Palace.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Buda

Salem Castle

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Schule_Schloss_Salem

Maiden Castle in 1934 |

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maiden_Castle,_Dorset

In this 1878 painting by Valery Jacobi, the scared newly-weds sit on the icy bed to the left; the jocular woman in golden dress is Empress Anna herself.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ice_palace

| Skeksis | |

|---|---|

| The Dark Crystal race | |

skekUng the Garthim-Master, one of the most prominent Skeksis in the film |

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Skeksis

Gorizia

| |

|---|---|

| Comune di Gorizia Občina Gorica Comun di Gurize | |

The old part of Gorizia seen from the castle in August 2008 | |

Location of Gorizia | |

| Coordinates: 45°56′N 13°37′E | |

| Country | Italy |

|---|---|

| Region | Friuli Venezia Giulia |

| Frazioni | Castello, Lucinico (Ločnik), Oslavia (Oslavje), Piuma (Pevma), San Mauro (Šmaver), Sant'Andrea (Štandrež), Straccis (Stražišče), Vallone dell'Acqua, Gradiscutta, Piedimonte (Podgora) |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Rodolfo Ziberna (Forza Italia) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 41 km2 (16 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 86 m (282 ft) |

| Population (November, 2017)[2] | |

| • Total | 34,428 |

| • Density | 840/km2 (2,200/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | Goriziani, Goričani |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 34170 |

| Dialing code | 0481 |

| Patron saint | Saints Hilary and Tatian |

| Saint day | March 16 |

| Website | Official website |

Gorizia (Italian pronunciation: [ɡoˈrittsja] (![]() listen); Slovene: Gorica [ɡɔˈɾìːtsa], colloquially stara Gorica 'old Gorizia'[3][4] to distinguish it from Nova Gorica; Standard Friulian: Gurize, Southeastern Friulian: Guriza; Bisiacco: Gorisia; German: Görz [ɡœʁts] (

listen); Slovene: Gorica [ɡɔˈɾìːtsa], colloquially stara Gorica 'old Gorizia'[3][4] to distinguish it from Nova Gorica; Standard Friulian: Gurize, Southeastern Friulian: Guriza; Bisiacco: Gorisia; German: Görz [ɡœʁts] (![]() listen); obsolete English Goritz)[5] is a town and comune in northeastern Italy, in the autonomous region of Friuli Venezia Giulia. It is located at the foot of the Julian Alps, bordering Slovenia. It was the capital of the former Province of Gorizia and is a local center of tourism, industry, and commerce. Since 1947, a twin town of Nova Gorica has developed on the other side of the modern-day Italy–Slovenia border. The region was subject to territorial dispute between Italy and Yugoslavia after World War II:

after the new boundaries were established in 1947 and the old town was

left to Italy, Nova Gorica was built on the Yugoslav side. The two towns

constitute a conurbation, which also includes the Slovenian municipality of Šempeter-Vrtojba.

Since May 2011, these three towns have been joined in a common

trans-border metropolitan zone, administered by a joint administration

board.[6]

listen); obsolete English Goritz)[5] is a town and comune in northeastern Italy, in the autonomous region of Friuli Venezia Giulia. It is located at the foot of the Julian Alps, bordering Slovenia. It was the capital of the former Province of Gorizia and is a local center of tourism, industry, and commerce. Since 1947, a twin town of Nova Gorica has developed on the other side of the modern-day Italy–Slovenia border. The region was subject to territorial dispute between Italy and Yugoslavia after World War II:

after the new boundaries were established in 1947 and the old town was

left to Italy, Nova Gorica was built on the Yugoslav side. The two towns

constitute a conurbation, which also includes the Slovenian municipality of Šempeter-Vrtojba.

Since May 2011, these three towns have been joined in a common

trans-border metropolitan zone, administered by a joint administration

board.[6]

The name of the town comes from the Slovene word gorica 'little hill', which is a common toponym in Slovene-inhabited areas.[7]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gorizia

The Royal Library in Warsaw (Polish: Biblioteka Królewska w Warszawie) is a large building adjacent to the Royal Castle in Warsaw, Poland. It was built between 1779 and 1783 according to design of Dominik Merlini and Jan Chrystian Kamsetzer in order to accommodate the royal collection of books belonging to King Stanisław August Poniatowski, the last King of sovereign Poland.

The Library is an elongated building of total dimensions 56 x 9 m, with 15 windows along the entrance hall, and a terrace at the top. The library initially held about 7,500 items, which grew to about 20,000 volumes in 1795. After the King's death in 1798 the whole collection was sold to Tadeusz Czacki, who bequeathed it to the Liceum Krzemienieckie. Following the collapse of the 1830 November Uprising against the Russian occupation, by order of Tsar Nicholas I of Russia, the library was seized and transported to Kiev where it formed the brand new University Library.[1]

Interiors of the library.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Royal_Library_in_Warsaw

Old fortifications of Nuremberg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nuremberg

An English country house is a large house or mansion in the English countryside. Such houses were often owned by individuals who also owned a town house. This allowed them to spend time in the country and in the city—hence, for these people, the term distinguished between town and country. However, the term also encompasses houses that were, and often still are, the full-time residence for the landed gentry who ruled rural Britain until the Reform Act 1832.[1] Frequently, the formal business of the counties was transacted in these country houses, having functional antecedents in manor houses.

With large numbers of indoor and outdoor staff, country houses were important as places of employment for many rural communities. In turn, until the agricultural depressions of the 1870s, the estates, of which country houses were the hub, provided their owners with incomes. However, the late 19th and early 20th centuries were the swansong of the traditional English country house lifestyle. Increased taxation and the effects of World War I led to the demolition of hundreds of houses; those that remained had to adapt to survive.

While a château or a Schloss can be a fortified or unfortified building, a country house, similar to an Ansitz, is usually unfortified. If fortified, it is called a castle, but not all buildings with the name "castle" are fortified (for example Highclere Castle in Hampshire).

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/English_country_house

Leverkusen | |

|---|---|

| |

Leverkusen within North Rhine-Westphalia | |

| Coordinates: 51°02′N 06°59′E | |

| Country | Germany |

|---|---|

| State | North Rhine-Westphalia |

| Admin. region | Köln |

| District | Urban district |

| Government | |

| • Lord mayor (2020–25) | Uwe Richrath[1] (SPD) |

| • Governing parties | CDU / SPD / Bürgerliste |

| Area | |

| • Total | 78.85 km2 (30.44 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 60 m (200 ft) |

| Population (2021-12-31)[2] | |

| • Total | 163,851 |

| • Density | 2,100/km2 (5,400/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+01:00 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+02:00 (CEST) |

| Dialling codes | 0214, 02171 & 02173 |

| Vehicle registration | LEV and OP |

| Website | www.leverkusen.de |

Leverkusen (German: [ˈleːvɐˌkuːzn̩] (![]() listen)) is a city in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany, on the eastern bank of the Rhine. To the south, Leverkusen borders the city of Cologne, and to the north the state capital, Düsseldorf.

listen)) is a city in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany, on the eastern bank of the Rhine. To the south, Leverkusen borders the city of Cologne, and to the north the state capital, Düsseldorf.

With about 161,000 inhabitants, Leverkusen is one of the state's smaller cities. The city is known for the pharmaceutical company Bayer and its sports club Bayer 04 Leverkusen.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leverkusen

The mythological princess Libuše prophesies the glory of Prague.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prague

An ivory tower is a metaphorical place—or an atmosphere—where people are happily cut off from the rest of the world in favor of their own pursuits, usually mental and esoteric ones. From the 19th century, it has been used to designate an environment of intellectual pursuit disconnected from the practical concerns of everyday life.[1] Most contemporary uses of the term refer to academia or the college and university systems in many countries.[2][3]

The term originated from the Biblical Song of Songs (7:4) with a different meaning and was later used as an epithet for Mary.[4]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ivory_tower

Tettnang | |

|---|---|

Town Hall (Old Castle) | |

Location of Tettnang within Bodenseekreis district | |

| Coordinates: 47°40′15″N 09°35′15″E | |

| Country | Germany |

|---|---|

| State | Baden-Württemberg |

| Admin. region | Tübingen |

| District | Bodenseekreis |

| Government | |

| • Mayor (2015–23) | Bruno Walter[1] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 71.22 km2 (27.50 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 466 m (1,529 ft) |

| Population (2021-12-31)[2] | |

| • Total | 19,710 |

| • Density | 280/km2 (720/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+01:00 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+02:00 (CEST) |

| Postal codes | 88069 |

| Dialling codes | 07542 |

| Vehicle registration | TT |

| Website | www.tettnang.de |

Tettnang is a town in the Bodensee district in southern Baden-Württemberg in Swabia region of Germany.

It lies 7 kilometres from Lake Constance. The region produces significant quantities of Tettnang hop, an ingredient of beer, and ships them to breweries throughout the world.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tettnang

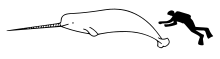

| Narwhal[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Size compared to an average human | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Infraorder: | Cetacea |

| Family: | Monodontidae |

| Genus: | Monodon Linnaeus, 1758 |

| Species: | M. monoceros

|

| Binomial name | |

| Monodon monoceros | |

| |

| The frequent (solid) and rare (striped) occurrence of narwhal populations | |

The narwhal, also known as a narwhale (Monodon monoceros), is a medium-sized toothed whale that possesses a large "tusk" from a protruding canine tooth. It lives year-round in the Arctic waters around Greenland, Canada and Russia. It is one of two living species of whale in the family Monodontidae, along with the beluga whale, and the only species in the genus Monodon. The narwhal males are distinguished by a long, straight, helical tusk, which is an elongated upper left canine. The narwhal was one of many species described by Carl Linnaeus in his publication Systema Naturae in 1758.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Narwhal

Torremaggiore | |

|---|---|

| Comune di Torremaggiore | |

Old postcard of Torremaggiore, ducal castle to the left | |

Location of Torremaggiore | |

| Coordinates: 41°41′N 15°17′E | |

| Country | Italy |

|---|---|

| Region | Apulia |

| Province | Foggia (FG) |

| Frazioni | Petrulli |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Emilio Di Pumpo |

| Area | |

| • Total | 210.01 km2 (81.09 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 169 m (554 ft) |

| Population (01-01-2021)[2] | |

| • Total | 16,643 |

| • Density | 79/km2 (210/sq mi) |

| Demonym | Torremaggiorese(i) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 71017 |

| Dialing code | 0882 |

| Patron saint | St. Sabinus Bishop |

| Saint day | First Sunday in June |

| Website | Official website |

Torremaggiore is a town, comune (municipality) and former seat of a bishopric, in the province of Foggia in the Apulia (in Italian: Puglia), region of southeast Italy.

It lies on a hill, 169 metres (554 ft) over the sea, and is famous for production of wine and olives.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Torremaggiore

Innsbruck

Innschbruck (Bavarian) | |

|---|---|

|

From top, left to right: Bürgerstraße, Conradstraße, view of Innsbruck, St. Anne's Column in Maria-Theresien-Straße, Stift Wilten, Ambras Castle, Altes Landhaus | |

| Coordinates: 47°16′06″N 11°23′36″E | |

| Country | Austria |

| State | Tyrol |

| District | Statutory city |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Georg Willi |

| Area | |

| • City | 104.91 km2 (40.51 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 574 m (1,883 ft) |

| Population (2018-01-01)[2] | |

| • City | 132,493 |

| • Density | 1,300/km2 (3,300/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 228,583 |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 6010–6080 |

| Area code | 0512 |

| Vehicle registration | I |

| Website | innsbruck.at |

Innsbruck (German: [ˈɪnsbʁʊk] (![]() listen); Austro-Bavarian: Innschbruck [ˈɪnʃprʊk]) is the capital of Tyrol and the fifth-largest city in Austria. On the River Inn, at its junction with the Wipp Valley, which provides access to the Brenner Pass 30 km (19 mi) to the south, it had a population of 132,493 in 2018.

listen); Austro-Bavarian: Innschbruck [ˈɪnʃprʊk]) is the capital of Tyrol and the fifth-largest city in Austria. On the River Inn, at its junction with the Wipp Valley, which provides access to the Brenner Pass 30 km (19 mi) to the south, it had a population of 132,493 in 2018.