The Goths (Gothic: 𐌲𐌿𐍄𐌸𐌹𐌿𐌳𐌰, romanized: Gutþiuda; Latin: Gothi, Greek: Γότθοι, translit. Gótthoi) were Germanic people who played a major role in the fall of the Western Roman Empire and the emergence of medieval Europe.[1][2][3]

In his book Getica (c. 551), the historian Jordanes writes that the Goths originated in southern Scandinavia, but the accuracy of this account is unclear.[1] A people called the Gutones – possibly early Goths – are documented living near the lower Vistula River in the 1st century, where they are associated with the archaeological Wielbark culture.[1][2] From the 2nd century, the Wielbark culture expanded southwards towards the Black Sea in what has been associated with Gothic migration, and by the late 3rd century it contributed to the formation of the Chernyakhov culture.[1][4] By the 4th century at the latest, several Gothic groups were distinguishable, among whom the Thervingi and Greuthungi were the most powerful.[5] During this time, Wulfila began the conversion of Goths to Christianity.[4]

In the late 4th century, the lands of the Goths were invaded from the east by the Huns. In the aftermath of this event, several groups of Goths came under Hunnic domination, while others migrated further west or sought refuge inside the Roman Empire. Goths who entered the Empire by crossing the Danube inflicted a devastating defeat upon the Romans at the Battle of Adrianople in 378. These Goths would form the Visigoths, and under their king Alaric I, they began a long migration, eventually establishing a Visigothic Kingdom in Spain at Toledo.[3] Meanwhile, Goths under Hunnic rule gained their independence in the 5th century, most importantly the Ostrogoths. Under their king Theodoric the Great, these Goths established an Ostrogothic Kingdom in Italy at Ravenna.[6][3]

The Ostrogothic Kingdom was destroyed by the Eastern Roman Empire in the 6th century, while the Visigothic Kingdom was conquered by the Umayyad Caliphate in the early 8th century. Remnants of Gothic communities in Crimea, known as the Crimean Goths, lingered on for several centuries, although Goths would eventually cease to exist as a distinct people.[5][4]

Name

In the Gothic language, the Goths were called the *Gut-þiuda ('Gothic people') or *Gutans ('Goths').[7][8] The Proto-Germanic form of the Gothic name is *Gutōz, which co-existed with an n-stem variant *Gutaniz, attested in Gutones, gutani, or gutniskr. The form *Gutōz is identical to that of the Gutes and closely related to that of the Geats (*Gautōz).[9] Though these names probably mean the same, their exact meaning is uncertain.[10] They are all thought to be related to the Proto-Germanic verb *geuta-, which means "to pour".[11]

Classification

The Goths are classified as a Germanic people in modern scholarship.[1][2][12][13][14] Along with the Burgundians, Vandals and others they belong to the East Germanic group.[15][16][17] Roman authors of late antiquity did not classify the Goths as Germani.[18][19][20][21] In modern scholarship the Goths are sometimes referred to as being Germani.[22][23][24]

History

Prehistory

A crucial source on Gothic history is the Getica of the 6th-century historian Jordanes, who may have been of Gothic descent.[25][26] Jordanes claims to have based the Getica on an earlier lost work by Cassiodorus, but also cites material from fifteen other classical sources, including an otherwise unknown writer, Ablabius.[27][28][29] Many scholars accept that Jordanes' account on Gothic origins is at least partially derived from Gothic tribal tradition and accurate on certain details.[30][31][32][33]

According to Jordanes, the Goths originated on an island called Scandza (Scandinavia), from where they emigrated by sea to an area called Gothiscandza under their king Berig.[34] Historians are not in agreement on the authenticity and accuracy of this account.[35][36][37][38][39] Most scholars agree that Gothic migration from Scandinavia is reflected in the archaeological record,[40] but the evidence is not entirely clear.[1][41][42] Rather than a single mass migration of an entire people, scholars open to hypothetical Scandinavian origins envision a process of gradual migration in the 1st centuries BC and AD, which was probably preceded by long-term contacts and perhaps limited to a few elite clans from Scandinavia.[43][44][45][46]

Similarities between the name of the Goths, some Swedish place names and the names of the Gutes and Geats have been cited as evidence that the Goths originated in Gotland or Götaland.[47][48][49] The Goths, Geats and Gutes may all have descended from an early community of seafarers active on both sides of the Baltic.[50][51][52] Similarities and dissimilarities between the Gothic language and Scandinavian languages (particularly Gutnish) have been cited as evidence both for and against a Scandinavian origin.[53][54]

Scholars generally locate Gothiscandza in the area of the Wielbark culture.[55][56][57] This culture emerged in the lower Vistula and along the Pomeranian coast in the 1st century AD, replacing the preceding Oksywie culture.[58] It is primarily distinguished from the Oksywie by the practice of inhumation, the absence of weapons in graves, and the presence of stone circles.[59][60] This area had been intimately connected with Scandinavia since the time of the Nordic Bronze Age and the Lusatian culture.[51] Its inhabitants in the Wielbark period are usually thought to have been Germanic peoples, such as the Goths and Rugii.[1][61][62][63][64] Jordanes writes that the Goths, soon after settling Gothiscandza, seized the lands of the Ulmerugi (Rugii).[65][66]

Early history

The Goths are generally believed to have been first attested by Greco-Roman sources in the 1st century under the name Gutones.[2][30][31][64][67][68] The equation between Gutones and later Goths is disputed by several historians.[69][70][71][72]

Around 15 AD, Strabo mentions the Butones, Lugii, and Semnones as part of a large group of peoples who came under the domination of the Marcomannic king Maroboduus.[73] The "Butones" are generally equated with the Gutones.[74][75] The Lugii have sometimes been considered the same people as the Vandals, with whom they were certainly closely affiliated.[76] The Vandals are associated with the Przeworsk culture, which was located to the south of the Wielbark culture.[77] Wolfram suggests that the Gutones were clients of the Lugii and Vandals in the 1st century AD.[76]

In 77 AD, Pliny the Elder mentions the Gutones as one of the peoples of Germania. He writes that the Gutones, Burgundiones, Varini, and Carini belong to the Vandili. Pliny classifies the Vandili as one of the five principal "German races", along with the coastal Ingvaeones, Istvaeones, Irminones, and Peucini.[78][76][79] In an earlier chapter Pliny writes that the 4th century BC traveler Pytheas encountered a people called the Guiones.[80] Some scholars have equated these Guiones with the Gutones, but the authenticity of the Pytheas account is uncertain.[50][81]

In his work Germania from around 98 AD, Tacitus writes that the Gotones (or Gothones) and the neighbouring Rugii and Lemovii were Germani who carried round shields and short swords, and lived near the ocean, beyond the Vandals.[82] He described them as "ruled by kings, a little more strictly than the other German tribes".[83][82][84] In another notable work, the Annals, Tacitus writes that the Gotones had assisted Catualda, a young Marcomannic exile, in overthrowing the rule of Maroboduus.[85][86] Prior to this, it is probable that both the Gutones and Vandals had been subjects of the Marcomanni.[82]

Sometime after settling Gothiscandza, Jordanes writes that the Goths defeated the neighbouring Vandals.[87] Wolfram believes the Gutones freed themselves from Vandalic domination at the beginning of the 2nd century AD.[76]

In his Geography from around 150 AD, Ptolemy mentions the Gythones (or Gutones) as living east of the Vistula in Sarmatia, between the Veneti and the Fenni.[88][89][90] In an earlier chapter he mentions a people called the Gutae (or Gautae) as living in southern Scandia.[91][90] These Gutae are probably the same as the later Gauti mentioned by Procopius.[89] Wolfram suggests that there were close relations between the Gythones and Gutae, and that they might have been of common origin.[89]

Movement towards the Black Sea

Beginning in the middle of the 2nd century, the Wielbark culture shifted southeast towards the Black Sea.[92] During this time the Wielbark culture is believed to have ejected and partially absorbed peoples of the Przeworsk culture.[92] This was part of a wider southward movement of eastern Germanic tribes, which was probably caused by massive population growth.[92] As a result, other tribes were pushed towards the Roman Empire, contributing to the beginning of the Marcomannic Wars.[92] By 200 AD, Wielbark Goths were probably being recruited into the Roman army.[93]

According to Jordanes, the Goths entered Oium, part of Scythia, under the king Filimer, where they defeated the Spali.[87][94] This migration account partly corresponds with the archaeological evidence.[41][95] The name Spali may mean "the giants" in Slavic, and the Spali were thus probably not Slavs.[96] In the early 3rd century AD, western Scythia was inhabited by the agricultural Zarubintsy culture and the nomadic Sarmatians.[97] Prior to the Sarmatians, the area had been settled by the Bastarnae, who are believed to have carried out a migration similar to the Goths in the 3rd century BC.[98] Peter Heather considers the Filimer story to be at least partially derived from Gothic oral tradition.[99][100] The fact that the expanding Goths appear to have preserved their Gothic language during their migration suggests that their movement involved a fairly large number of people.[101]

By the mid-3rd century AD, the Wielbark culture had contributed to the formation of the Chernyakhov culture in Scythia.[102][103] This strikingly uniform culture came to stretch from the Danube in the west to the Don in the east.[104] It is believed to have been dominated by the Goths and other Germanic groups such as the Heruli.[105] It nevertheless also included Iranian, Dacian, Roman and probably Slavic elements as well.[104]

3rd century raids on the Roman Empire

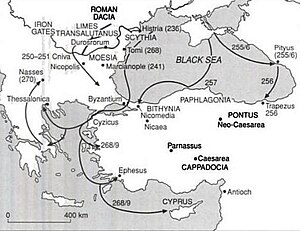

The first incursion of the Roman Empire that can be attributed to Goths is the sack of Histria in 238.[98][106] The first references to the Goths in the 3rd century call them Scythians, as this area, known as Scythia, had historically been occupied by an unrelated people of that name.[107] It is in the late 3rd century that the name Goths (Latin: Gothi) is first mentioned.[108] Ancient authors do not identify the Goths with the earlier Gutones.[109][70] Philologists and linguists have no doubt that the names are linked.[110][111]

On the Pontic steppe the Goths quickly adopted several nomadic customs from the Sarmatians.[112] They excelled at horsemanship, archery and falconry,[113] and were also accomplished agriculturalists[114] and seafarers.[115] J. B. Bury describes the Gothic period as "the only non-nomadic episode in the history of the steppe."[116] William H. McNeill compares the migration of the Goths to that of the early Mongols, who migrated southward from the forests and came to dominate the eastern Eurasian steppe around the same time as the Goths in the west.[112] From the 240s at the earliest, Goths were heavily recruited into the Roman Army to fight in the Roman–Persian Wars, notably participating at the Battle of Misiche in 244.[117] An inscription at the Ka'ba-ye Zartosht in Parthian, Persian and Greek commemorates the Persian victory over the Romans and the troops drawn from Gwt W Germany xštr, the Gothic and German kingdoms,[118] which is probably a Parthian gloss for the Danubian (Gothic) limes and the Germanic limes.[119]

Meanwhile, Gothic raids on the Roman Empire continued,[120] In 250–51, the Gothic king Cniva captured the city of Philippopolis and inflicted a devastating defeat upon the Romans at the Battle of Abrittus, in which the Roman Emperor Decius was killed.[121][98] This was one of the most disastrious defeats in the history of the Roman army.[98]

The first Gothic seaborne raids took place in the 250s. The first two incursions into Asia Minor took place between 253 and 256, and are attributed to Boranoi by Zosimus. This may not be an ethnic term but may just mean "people from the north". It is unknown if Goths were involved in these first raids. Gregory Thaumaturgus attributes a third attack to Goths and Boradoi, and claims that some, "forgetting that they were men of Pontus and Christians," joined the invaders.[122] An unsuccessful attack on Pityus was followed in the second year by another, which sacked Pityus and Trabzon and ravaged large areas in the Pontus. In the third year, a much larger force devastated large areas of Bithynia and the Propontis, including the cities of Chalcedon, Nicomedia, Nicaea, Apamea Myrlea, Cius and Bursa. By the end of the raids, the Goths had seized control over Crimea and the Bosporus and captured several cities on the Euxine coast, including Olbia and Tyras, which enabled them to engage in widespread naval activities.[115][98][123]

After a 10-year hiatus, the Goths and the Heruli, with a raiding fleet of 500 ships,[124] sacked Heraclea Pontica, Cyzicus and Byzantium.[125] They were defeated by the Roman navy but managed to escape into the Aegean Sea, where they ravaged the islands of Lemnos and Scyros, broke through Thermopylae and sacked several cities of southern Greece (province of Achaea) including Athens, Corinth, Argos, Olympia and Sparta.[115] Then an Athenian militia, led by the historian Dexippus, pushed the invaders to the north where they were intercepted by the Roman army under Gallienus.[126][115] He won an important victory near the Nessos (Nestos) river, on the boundary between Macedonia and Thrace, the Dalmatian cavalry of the Roman army earning a reputation as good fighters. Reported barbarian casualties were 3,000 men.[127][115] Subsequently, the Heruli leader Naulobatus came to terms with the Romans.[124][115][98]

After Gallienus was assassinated outside Milan in the summer of 268 in a plot led by high officers in his army, Claudius was proclaimed emperor and headed to Rome to establish his rule. Claudius' immediate concerns were with the Alamanni, who had invaded Raetia and Italy. After he defeated them in the Battle of Lake Benacus, he was finally able to take care of the invasions in the Balkan provinces.[128][98]

In the meantime, a second and larger sea-borne invasion had started. An enormous coalition consisting of Goths (Greuthungi and Thervingi), Gepids and Peucini, led again by the Heruli, assembled at the mouth of river Tyras (Dniester).[a][115] The Augustan History and Zosimus claim a total number of 2,000–6,000 ships and 325,000 men.[129] This is probably a gross exaggeration but remains indicative of the scale of the invasion.[115] After failing to storm some towns on the coasts of the western Black Sea and the Danube (Tomi, Marcianopolis), the invaders attacked Byzantium and Chrysopolis. Part of their fleet was wrecked, either because of the Goth's inexperience in sailing through the violent currents of the Propontis[127] or because they were defeated by the Roman navy.[115] Then they entered the Aegean Sea and a detachment ravaged the Aegean islands as far as Crete, Rhodes and Cyprus.[115] According to the Augustan History, the Goths achieved no success on this expedition because they were struck by the Cyprianic Plague.[130] The fleet probably also sacked Troy and Ephesus, damaging the Temple of Artemis, though the temple was repaired and then later torn down by Christians a century later, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.[115] While their main force had constructed siege works and was close to taking the cities of Thessalonica and Cassandreia, it retreated to the Balkan interior at the news that the emperor was advancing.[115][98]

Learning of the approach of Claudius, the Goths first attempted to directly invade Italy.[131] They were engaged near Naissus by a Roman army led by Claudius advancing from the north. The battle most likely took place in 269, and was fiercely contested. Large numbers on both sides were killed but, at the critical point, the Romans tricked the Goths into an ambush by pretending to retreat. Some 50,000 Goths were allegedly killed or taken captive and their base at Thessalonika destroyed.[127][115] Apparently Aurelian, who was in charge of all Roman cavalry during Claudius' reign, led the decisive attack in the battle. Some survivors were resettled within the empire, while others were incorporated into the Roman army.[115][98] The battle ensured the survival of the Roman Empire for another two centuries.[131]

In 270, after the death of Claudius, Goths under the leadership of Cannabaudes again launched an invasion of the Roman Empire, but were defeated by Aurelian, who, however, did surrender Dacia beyond the Danube.[132][106][133]

Around 275 the Goths launched a last major assault on Asia Minor, where piracy by Black Sea Goths was causing great trouble in Colchis, Pontus, Cappadocia, Galatia and even Cilicia.[134] They were defeated sometime in 276 by Emperor Marcus Claudius Tacitus.[134]

By the late 3rd century, there were at least two groups of Goths, separated by the Dniester River: the Thervingi and the Greuthungi.[135] The Gepids, who lived northwest of the Goths, are also attested as this time.[136] Jordanes writes that the Gepids shared common origins with the Goths.[136][137]

In the late 3rd century, as recorded by Jordanes, the Gepids, under their king Fastida, utterly defeated the Burgundians, and then attacked the Goths and their king Ostrogotha. Out of this conflict, Ostrogotha and the Goths emerged victorious.[138][139] In the last decades of the 3rd century, large numbers of Carpi are recorded as fleeing Dacia for the Roman Empire, having probably been driven from the area by Goths.[98]

Co-existence with the Roman Empire (300–375)

In 332, Constantine helped the Sarmatians to settle on the north banks of the Danube to defend against the Goths' attacks and thereby enforce the Roman border. Around 100,000 Goths were reportedly killed in battle, and Aoric, son of the Thervingian king Ariaric, was captured.[140] Eusebius, a historian who wrote in Greek in the third century, wrote that in 334, Constantine evacuated approximately 300,000 Sarmatians from the north bank of the Danube after a revolt of the Sarmatians' slaves. From 335 to 336, Constantine, continuing his Danube campaign, defeated many Gothic tribes.[141]

Having been driven from the Danube by the Romans, the Thervingi invaded the territory of the Sarmatians of the Tisza. In this conflict, the Thervingi were led by Vidigoia, "the bravest of the Goths" and were victorious, although Vidigoia was killed.[142] Jordanes states that Aoric was succeeded by Geberic, "a man renowned for his valor and noble birth", who waged war on the Hasdingi Vandals and their king Visimar, forcing them to settle in Pannonia under Roman protection.[143][144]

Both the Greuthungi and Thervingi became heavily Romanized during the 4th century. This came about through trade with the Romans, as well as through Gothic membership of a military covenant, which was based in Byzantium and involved pledges of military assistance. Reportedly, 40,000 Goths were brought by Constantine to defend Constantinople in his later reign, and the Palace Guard was thereafter mostly composed of Germanic warriors, as Roman soldiers by this time had largely lost military value.[145] The Goths increasingly became soldiers in the Roman armies in the 4th century leading to a significant Germanization of the Roman Army.[146] Without the recruitment of Germanic warriors in the Roman Army, the Roman Empire would not have survived for as long as it did.[146] Goths who gained prominent positions in the Roman military include Gainas, Tribigild, Fravitta and Aspar. Mardonius, a Gothic eunuch, was the childhood tutor and later adviser of Roman emperor Julian, on whom he had an immense influence.[4]

The Gothic penchant for wearing skins became fashionable in Constantinople, a fashion which was loudly denounced by conservatives.[147] The 4th-century Greek bishop Synesius compared the Goths to wolves among sheep, mocked them for wearing skins and questioned their loyalty towards Rome:

A man in skins leading warriors who wear the chlamys, exchanging his sheepskins for the toga to debate with Roman magistrates and perhaps even sit next to a Roman consul, while law–abiding men sit behind. Then these same men, once they have gone a little way from the senate house, put on their sheepskins again, and when they have rejoined their fellows they mock the toga, saying that they cannot comfortably draw their swords in it.[147]

In the 4th century, Geberic was succeeded by the Greuthungian king Ermanaric, who embarked on a large-scale expansion.[148] Jordanes states that Ermanaric conquered a large number of warlike tribes, including the Heruli (who were led by Alaric), the Aesti and the Vistula Veneti, who, although militarily weak, were very numerous, and put up a strong resistance.[149][148] Jordanes compares the conquests of Ermanaric to those of Alexander the Great, and states that he "ruled all the nations of Scythia and Germany by his own prowess alone."[149] Interpreting Jordanes, Herwig Wolfram estimates that Ermanaric dominated a vast area of the Pontic Steppe stretching from the Baltic Sea to the Black Sea as far eastwards as the Ural Mountains,[148][150] encompassing not only the Greuthungi, but also Baltic Finnic peoples, Slavs (such as the Antes), Rosomoni (Roxolani), Alans, Huns, Sarmatians and probably Aestii (Balts).[151] According to Wolfram, it is certainly possible that the sphere of influence of the Chernyakhov culture could have extended well beyond its archaeological extent.[148] Chernyakhov archaeological finds have been found far to the north in the forest steppe, suggesting Gothic domination of this area.[152] Peter Heather on the other hand, contends that the extent of Ermanaric's power is exaggerated.[153] Ermanaric's possible dominance of the Volga-Don trade routes has led historian Gottfried Schramm to consider his realm a forerunner of the Viking-founded state of Kievan Rus'.[154] In the western part of Gothic territories, dominated by the Thervingi, there were also populations of Taifali, Sarmatians and other Iranian peoples, Dacians, Daco-Romans and other Romanized populations.[155]

According to Hervarar saga ok Heiðreks (The Saga of Hervör and Heidrek), a 13th-century legendary saga, Árheimar was the capital of Reidgotaland, the land of the Goths. The saga states that it was located on the Dnieper river. Jordanes refers to the region as Oium.[94]

In the 360s, Athanaric, son of Aoric and leader of the Thervingi, supported the usurper Procopius against the Eastern Roman Emperor Valens. In retaliation, Valens invaded the territories of Athanaric and defeated him, but was unable to achieve a decisive victory. Athanaric and Valens thereupon negotiated a peace treaty, favorable to the Thervingi, on a boat in the Danube river, as Athanaric refused to set his feet within the Roman Empire. Soon afterwards, Fritigern, a rival of Athanaric, converted to Arianism, gaining the favor of Valens. Athanaric and Fritigern thereafter fought a civil war in which Athanaric appears to have been victorious. Athanaric thereafter carried out a crackdown on Christianity in his realm.[156]

Arrival of the Huns (about 375)

Around 375 the Huns overran the Alans, an Iranian people living to the east of the Goths, and then, along with Alans, invaded the territory of the Goths - the Gothic empire[157][158] A source for this period is the Roman historian Ammianus Marcellinus, who wrote that Hunnic domination of the Gothic kingdoms in Scythia began in the 370s.[159] It is possible that the Hunnic attack came as a response to the Gothic expansion eastwards.[160]

Upon the suicide of Ermanaric (died 376), the Greuthungi gradually fell under Hunnic domination. Christopher I. Beckwith suggests that the Hunnic thrust into Europe and the Roman Empire was an attempt to subdue the independent Goths in the west.[161] The Huns fell upon the Thervingi, and Athanaric sought refuge in the mountains (referred to as Caucaland in the sagas).[162] Ambrose makes a passing reference to Athanaric's royal titles before 376 in his De Spiritu Sancto (On the Holy Spirit).[163]

Battles between the Goths and the Huns are described in the "Hlöðskviða" (The Battle of the Goths and Huns), a medieval Icelandic saga. The sagas recall that Gizur, king of the Geats, came to the aid of the Goths in an epic conflict with the Huns, although this saga might derive from a later Gothic-Hunnic conflict.[164]

Although the Huns successfully subdued many of the Goths who subsequently joined their ranks, Fritigern approached the Eastern Roman emperor Valens in 376 with a portion of his people and asked to be allowed to settle on the south bank of the Danube. Valens permitted this, and even assisted the Goths in their crossing of the river (probably at the fortress of Durostorum).[165] The Gothic evacuation across the Danube was probably not spontaneous, but rather a carefully planned operation initiated after long debate among leading members of the community.[166] Upon arrival, the Goths were to be disarmed according to their agreement with the Romans, although many of them still managed to keep their arms.[165] The Moesogoths settled in Thrace and Moesia.[167]

The Gothic War of 376–382

Mistreated by corrupt local Roman officials, the Gothic refugees were soon experiencing a famine; some are recorded as having been forced to sell their children to Roman slave traders in return for rotten dog meat.[165] Enraged by this treachery, Fritigern unleashed a widescale rebellion in Thrace, in which he was joined not only by Gothic refugees and slaves, but also by disgruntled Roman workers and peasants, and Gothic deserters from the Roman Army. The ensuing conflict, known as the Gothic War, lasted for several years.[168] Meanwhile, a group of Greuthungi, led by the chieftains Alatheus and Saphrax, who were co-regents with Vithericus, son and heir of the Greuthungi king Vithimiris, crossed the Danube without Roman permission.[168] The Gothic War culminated in the Battle of Adrianople in 378, in which the Romans were badly defeated and Valens was killed.[169][170]

Following the decisive Gothic victory at Adrianople, Julius, the magister militum of the Eastern Roman Empire, organized a wholesale massacre of Goths in Asia Minor, Syria and other parts of the Roman East. Fearing rebellion, Julian lured the Goths into the confines of urban streets from which they could not escape and massacred soldiers and civilians alike. As word spread, the Goths rioted throughout the region, and large numbers were killed. Survivors may have settled in Phrygia.[171]

With the rise of Theodosius I in 379, the Romans launched a renewed offensive to subdue Fritigern and his followers.[172][173] Around the same time, Athanaric arrived in Constantinople, having fled Caucaland through the scheming of Fritigern.[172] Athanaric received a warm reception by Theodosius, praised the Roman Emperor in return, and was honoured with a magnificent funeral by the emperor following his death shortly after his arrival.[174] In 382, Theodosius decided to enter peace negotiations with the Thervingi, which were concluded on 3 October 382.[174] The Thervingi were subsequently made foederati of the Romans in Thrace and obliged to provide troops to the Roman army.[174]

Later division and spread of the Goths

In the aftermath of the Hunnic onslaught, two major groups of the Goths would eventually emerge, the Visigoths and Ostrogoths.[175][176][177][178] Visigoths means the "Goths of the west", while Ostrogoths means "Goths of the east".[179] The Visigoths, led by the Balti dynasty, claimed descent from the Thervingi and lived as foederati inside Roman territory, while the Ostrogoths, led by the Amali dynasty, claimed descent from the Greuthungi and were subjects of the Huns.[180] Procopius interpreted the name Visigoth as "western Goths" and the name Ostrogoth as "eastern Goth", reflecting the geographic distribution of the Gothic realms at that time.[181] A people closely related to the Goths, the Gepids, were also living under Hunnic domination.[182] A smaller group of Goths were the Crimean Goths, who remained in Crimea and maintained their Gothic identity well into the Middle Ages.[180]

Visigoths

The Visigoths were a new Gothic political unit brought together during the career of their first leader, Alaric I.[183] Following a major settlement of Goths in the Balkans made by Theodosius in 382, Goths received prominent positions in the Roman army.[184] Relations with Roman civilians were sometimes uneasy. In 391, Gothic soldiers, with the blessing of Theodosius I, massacred thousands of Roman spectators at the Hippodrome in Thessalonica as vengeance for the lynching of the Gothic general Butheric.[185]

The Goths suffered heavy losses while serving Theodosius in the civil war of 394 against Eugenius and Arbogast.[186] In 395, following the death of Theodosius I, Alaric and his Balkan Goths invaded Greece, where they sacked Piraeus (the port of Athens) and destroyed Corinth, Megara, Argos, and Sparta.[187][188] Athens itself was spared by paying a large bribe, and the Eastern emperor Flavius Arcadius subsequently appointed Alaric magister militum ("master of the soldiers") in Illyricum in 397.[188]

In 401 and 402, Alaric made two attempts at invading Italy, but was defeated by Stilicho. In 405–406, another Gothic leader, Radagaisus, also attempted to invade Italy, and was also defeated by Stilicho.[106][189] In 408, the Western Roman emperor Flavius Honorius ordered the execution of Stilicho and his family, then incited the Roman population to massacre tens of thousands of wives and children of Goths serving in the Roman military. Subsequently, around 30,000 Gothic soldiers defected to Alaric.[188] Alaric in turn invaded Italy, seeking to pressure Honorious into granting him permission to settle his people in North Africa.[188] In Italy, Alaric liberated tens of thousands of Gothic slaves, and in 410 he sacked the city of Rome. Although the city's riches were plundered, the civilian inhabitants of the city were treated humanely, and only a few buildings were burned.[188] Alaric died soon afterwards, and was buried along with his treasure in an unknown grave under the Busento river.[190]

Alaric was succeeded by his brother-in–law Athaulf, husband of Honorius' sister Galla Placidia, who had been seized during Alaric's sack of Rome. Athaulf settled the Visigoths in southern Gaul.[191][192] After failing to gain recognition from the Romans, Athaulf retreated into Hispania in early 415, and was assassinated in Barcelona shortly afterwards.[193] He was succeeded by Sigeric and then Wallia, who succeeded in having the Visigoths accepted by Honorius as foederati in southern Gaul, with their capital at Toulouse. Wallia subsequently inflicted severe defeats upon the Silingi Vandals and the Alans in Hispania.[191] Periodically they marched on Arles, the seat of the praetorian prefect but were always pushed back. In 437 the Visigoths signed a treaty with the Romans which they kept.[194]

Under Theodoric I the Visigoths allied with the Romans and fought Attila to a stalemate in the Battle of the Catalaunian Fields, although Theodoric was killed in the battle.[191][106] Under Euric, the Visigoths established an independent Visigothic Kingdom and succeeded in driving the Suebi out of Hispania proper and back into Galicia.[191] Although they controlled Spain, they still formed a tiny minority among a much larger Hispano-Roman population, approximately 200,000 out of 6,000,000.[191]

In 507, the Visigoths were pushed out of most of Gaul by the Frankish king Clovis I at the Battle of Vouillé.[106] They were able to retain Narbonensis and Provence after the timely arrival of an Ostrogoth detachment sent by Theodoric the Great. The defeat at Vouillé resulted in their penetrating further into Hispania and establishing a new capital at Toledo.[191]

Under Liuvigild in the latter part of the 6th century, the Visigoths succeeded in subduing the Suebi in Galicia and the Byzantines in the south-west, and thus achieved dominance over most of the Iberian peninsula.[191] Liuvigild also abolished the law that prevented intermarriage between Hispano-Romans and Goths, and he remained an Arian Christian.[191] The conversion of Reccared I to Roman Catholicism in the late 6th century prompted the assimilation of Goths with the Hispano-Romans.[191]

At the end of the 7th century, the Visigothic Kingdom began to suffer from internal troubles.[191] Their kingdom fell and was progressively conquered by the Umayyad Caliphate from 711 after the defeat of their last king Roderic at the Battle of Guadalete. Some Visigothic nobles found refuge in the mountain areas of the Asturias, Pyrenees and Cantabria. According to Joseph F. O'Callaghan, the remnants of the Hispano-Gothic aristocracy still played an important role in the society of Hispania. At the end of Visigothic rule, the assimilation of Hispano-Romans and Visigoths was occurring at a fast pace. Their nobility had begun to think of themselves as constituting one people, the gens Gothorum or the Hispani. An unknown number of them fled and took refuge in Asturias or Septimania. In Asturias they supported Pelagius's uprising, and joining with the indigenous leaders, formed a new aristocracy. The population of the mountain region consisted of native Astures, Galicians, Cantabri, Basques and other groups unassimilated into Hispano-Gothic society.[195] The Christians began to regain control under the leadership of the nobleman Pelagius of Asturias, who founded the Kingdom of Asturias in 718 and defeated the Muslims at the Battle of Covadonga in c. 722, in what is taken by historians to be the beginning of the Reconquista. It was from the Asturian kingdom that modern Spain and Portugal evolved.[191]

The Visigoths were never completely Romanized; rather, they were 'Hispanicized' as they spread widely over a large territory and population. They progressively adopted a new culture, retaining little of their original culture except for practical military customs, some artistic modalities, family traditions such as heroic songs and folklore, as well as select conventions to include Germanic names still in use in present-day Spain. It is these artifacts of the original Visigothic culture that give ample evidence of its contributing foundation for the present regional culture.[161] Portraying themselves heirs of the Visigoths, the subsequent Christian Spanish monarchs declared their responsibility for the Reconquista of Muslim Spain, which was completed with the Fall of Granada in 1492.[191]

Ostrogoths

After the Hunnic invasion, many Goths became subjects of the Huns. A section of these Goths under the leadership of the Amali dynasty came to be known as the Ostrogoths.[180] Others sought refuge in the Roman Empire, where many of them were recruited into the Roman army. In the spring of 399, Tribigild, a Gothic leader in charge of troops in Nakoleia, rose up in rebellion and defeated the first imperial army sent against him, possibly seeking to emulate Alaric's successes in the west.[196] Gainas, a Goth who along with Stilicho and Eutropius had deposed Rufinus in 395, was sent to suppress Tribigild's rebellion, but instead plotted to use the situation to seize power in the Eastern Roman Empire. This attempt was however thwarted by the pro-Roman Goth Fravitta, and in the aftermath, thousands of Gothic civilians were massacred in Constantinople,[4] many being burned alive in the local Arian church where they had taken shelter.[196] As late as the 6th century Goths were settled as foederati in parts of Asia Minor. Their descendants, who formed the elite Optimatoi regiment, still lived there in the early 8th century.[197] While they were largely assimilated, their Gothic origin was still well–known: the chronicler Theophanes the Confessor calls them Gothograeci.[4]

The Ostrogoths fought together with the Huns at the Battle of the Catalaunian Plains in 451.[198] Following the death of Attila and the defeat of the Huns at the Battle of Nedao in 454, the Ostrogoths broke away from Hunnic rule under their king Valamir.[199] Mentions of this event were probably preserved in Slavic epic songs.[200] Under his successor, Theodemir, they utterly defeated the Huns at the Bassianae in 468,[201] and then defeated a coalition of Roman–supported Germanic tribes at the Battle of Bolia in 469, which gained them supremacy in Pannonia.[201]

Theodemir was succeeded by his son Theodoric in 471, who was forced to compete with Theodoric Strabo, leader of the Thracian Goths, for the leadership of his people.[202] Fearing the threat posed by Theodoric to Constantinople, the Eastern Roman emperor Zeno ordered Theodoric to invade Italy in 488. By 493,[169] Theodoric had conquered all of Italy from the Scirian Odoacer, whom he killed with his own hands;[202] he subsequently formed the Ostrogothic Kingdom. Theodoric settled his entire people in Italy, estimated at 100,000–200,000, mostly in the northern part of the country, and ruled the country very efficiently. The Goths in Italy constituted a small minority of the population in the country.[145] Intermarriage between Goths and Romans were forbidden, and Romans were also forbidden from carrying arms. Nevertheless, the Roman majority was treated fairly.[202]

The Goths were briefly reunited under one crown in the early 6th century under Theodoric, who became regent of the Visigothic kingdom following the death of Alaric II at the Battle of Vouillé in 507.[203] Shortly after Theodoric's death, the country was invaded by the Eastern Roman Empire in the Gothic War, which severely devastated and depopulated the Italian peninsula.[204] The Ostrogoths made a brief resurgence under their king Totila,[106] who was, however, killed at the Battle of Taginae in 552. After the last stand of the Ostrogothic king Teia at the Battle of Mons Lactarius in 553, Ostrogothic resistance ended, and the remaining Goths in Italy were assimilated by the Lombards, another Germanic tribe, who invaded Italy and founded the Kingdom of the Lombards in 567.[106][205]

Crimean Goths

Gothic tribes who remained in the lands around the Black Sea,[180] especially in Crimea, were known as the Crimean Goths. During the late 5th and early 6th century, the Crimean Goths had to fend off hordes of Huns who were migrating back eastward after losing control of their European empire.[206] In the 5th century, Theodoric the Great tried to recruit Crimean Goths for his campaigns in Italy, but few showed interest in joining him.[207] They affiliated with the Eastern Orthodox Church through the Metropolitanate of Gothia, and were then closely associated with the Byzantine Empire.[208]

During the Middle Ages, the Crimean Goths were in perpetual conflict with the Khazars. John of Gothia, the metropolitan bishop of Doros, capital of the Crimean Goths, briefly expelled the Khazars from Crimea in the late 8th century, and was subsequently canonized as an Eastern Orthodox saint.[209]

In the 10th century, the lands of the Crimean Goths were once again raided by the Khazars. As a response, the leaders of the Crimean Goths made an alliance with Sviatoslav I of Kiev, who subsequently waged war upon and utterly destroyed the Khazar Khaganate.[209] In the late Middle Ages the Crimean Goths were part of the Principality of Theodoro, which was conquered by the Ottoman Empire in the late 15th century. As late as the 18th century a small number of people in Crimea may still have spoken Crimean Gothic.[210]

Language

The Goths were Germanic-speaking.[211] The Gothic language is the Germanic language with the earliest attestation (the 4th century),[212][169] and the only East Germanic language documented in more than proper names, short phrases that survived in historical accounts, and loan-words in other languages, making it a language of great interest in comparative linguistics. Gothic is known primarily from the Codex Argenteus, which contains a partial translation of the Bible credited to Ulfilas.[213]

The language was in decline by the mid-500s, due to the military victory of the Franks, the elimination of the Goths in Italy, and geographic isolation. In Spain, the language lost its last and probably already declining function as a church language when the Visigoths converted to Catholicism in 589;[214] it survived as a domestic language in the Iberian peninsula (modern Spain and Portugal) as late as the 8th century.

Frankish author Walafrid Strabo wrote that Gothic was still spoken in the lower Danube area, in what is now Bulgaria, in the early 9th century,[213] and a related dialect known as Crimean Gothic was spoken in the Crimea until the 16th century, according to references in the writings of travelers.[215] Most modern scholars believe that Crimean Gothic did not derive from the dialect that was the basis for Ulfilas' translation of the Bible.

Physical appearance

In ancient sources, the Goths are always described as tall and athletic, with light skin, blonde hair and blue eyes.[216][217] The 4th-century Greek historian Eunapius described their characteristic powerful musculature in a pejorative way: "Their bodies provoked contempt in all who saw them, for they were far too big and far too heavy for their feet to carry them, and they were pinched in at the waist – just like those insects Aristotle writes of."[218] Procopius notes that the Vandals and Gepids looked similar to the Goths, and on this basis, he suggested that they were all of common origin. Of the Goths, he wrote that "they all have white bodies and fair hair, and are tall and handsome to look upon."[219]

Culture

Art

Early

Before the invasion of the Huns, the Gothic Chernyakhov culture produced jewelry, vessels, and decorative objects in a style much influenced by Greek and Roman craftsmen. They developed a polychrome style of gold work, using wrought cells or setting to encrust gemstones into their gold objects.[220]

Ostrogoths

The eagle-shaped fibula, part of the Domagnano Treasure, was used to join clothes c. AD 500; the piece on display in the Germanisches Nationalmuseum in Nuremberg is well-known.

Visigoths

In Spain an important collection of Visigothic metalwork was found in the treasure of Guarrazar, Guadamur, Province of Toledo, Castile-La Mancha, an archeological find composed of twenty-six votive crowns and gold crosses from the royal workshop in Toledo, with Byzantine influence. The treasure represents the high point of Visigothic goldsmithery, according to Guerra, Galligaro & Perea (2007).[221] The two most important votive crowns are those of Recceswinth and of Suintila, displayed in the National Archaeological Museum of Madrid; both are made of gold, encrusted with sapphires, pearls, and other precious stones. Suintila's crown was stolen in 1921 and never recovered. There are several other small crowns and many votive crosses in the treasure.

These findings, along with others from some neighbouring sites and with the archaeological excavation of the Spanish Ministry of Public Works and the Royal Spanish Academy of History (April 1859), formed a group consisting of:

- National Archaeological Museum of Spain: six crowns, five crosses, a pendant and remnants of foil and channels (almost all of gold).

- Royal Palace of Madrid: a crown and a gold cross and a stone engraved with the Annunciation. A crown, and other fragments of a tiller with a crystal ball were stolen from the Royal Palace of Madrid in 1921 and its whereabouts are still unknown.

- National Museum of the Middle Ages, Paris: three crowns, two crosses, links and gold pendants.

The aquiliform (eagle-shaped) fibulae that have been discovered in necropolises such as Duraton, Madrona or Castiltierra (cities of Segovia), are an unmistakable indication of the Visigothic presence in Spain. These fibulae were used individually or in pairs, as clasps or pins in gold, bronze and glass to join clothes, showing the work of the goldsmiths of Visigothic Hispania.[222]

The Visigothic belt buckles, a symbol of rank and status characteristic of Visigothic women's clothing, are also notable as works of goldsmithery. Some pieces contain exceptional Byzantine-style lapis lazuli inlays and are generally rectangular in shape, with copper alloy, garnets and glass.[223][c]

Society

Archaeological evidence in Visigothic cemeteries shows that social stratification was analogous to that of the village of Sabbas the Goth. The majority of villagers were common peasants. Paupers were buried with funeral rites, unlike slaves. In a village of 50 to 100 people, there were four or five elite couples.[224] In Eastern Europe, houses include sunken-floored dwellings, surface dwellings, and stall-houses. The largest known settlement is the Criuleni District.[220] Chernyakhov cemeteries feature both cremation and inhumation burials; among the latter the head aligned to the north. Some graves were left empty. Grave goods often include pottery, bone combs, and iron tools, but hardly ever weapons.[220]

Peter Heather suggests that the freemen constituted the core of Gothic society. These were ranked below the nobility, but above the freedmen and slaves. It is estimated that around a quarter to a fifth of weapon-bearing Gothic males of the Ostrogothic Kingdom were freemen.[225]

Religion

Initially practising Gothic paganism, the Goths were gradually converted to Arianism in the course of the 4th century.[226] According to Basil of Caesarea, a prisoner named Eutychus taken captive in a raid on Cappadocia in 260 preached the gospel to the Goths and was martyred.[227] It was only in the 4th century, as a result of missionary activity by the Gothic bishop Ulfilas, whose grandparents were Cappadocians taken captive in the raids of the 250s,[227] that the Goths were gradually converted.[226] Ulfilas devised a Gothic alphabet and translated the Gothic Bible.[226]

During the 370s, Goths converting to Christianity were subject to persecution by the Thervingian king Athanaric, who was a pagan.[156]

The Visigothic Kingdom in Hispania converted to Catholicism in the late 6th century.[228]

The Ostrogoths (and their remnants, the Crimean Goths) were closely connected to the Patriarchate of Constantinople from the 5th century, and became fully incorporated under the Metropolitanate of Gothia from the 9th century.[209]

Law

Warfare

Gothic arms and armour usually consisted of wooden shield, spear and often swords. 'Rank and file' troops did not wear much protection, while warriors of higher social class were better equipped, as was common for most tribal peoples of the time.

Armour was either a chainmail shirt or lamellar cuirass. Lamellar was popular among horsemen. Shields were either round or oval with a central boss grip. They were decorated with tribe or clan symbols, such as animal drawings. Helmets were often of spangenhelm type, often with cheek and neck plates. Spears were used both for thrusting and throwing, although specialized javelins were also in use. Swords were one handed, double edged and straight, with a very small crossguard and large pommel. It was called the Spatha by the Romans, and it is believed to have first been used by the Celts. Short wooden bows were also used, as well as occasional throwing axes.[229] Missile weapons were mainly short throwing axes such as Fransica and short wooden bows. Specialized javelins such as angon were more rare but still used[230]

Economy

Archaeology shows that the Visigoths, unlike the Ostrogoths, were predominantly farmers. They sowed wheat, barley, rye, and flax. They also raised pigs, poultry, and goats. Horses and donkeys were raised as working animals and fed with hay. Sheep were raised for their wool, which they fashioned into clothing. Archaeology indicates they were skilled potters and blacksmiths. When peace treaties were negotiated with the Romans, the Goths demanded free trade. Imports from Rome included wine and cooking-oil.[224]

Roman writers note that the Goths neither assessed taxes on their own people nor on their subjects. The early 5th-century Christian writer Salvian compared the Goths' and related people's favourable treatment of the poor to the miserable state of peasants in Roman Gaul:

For in the Gothic country the barbarians are so far from tolerating this sort of oppression that not even Romans who live among them have to bear it. Hence all the Romans in that region have but one desire, that they may never have to return to the Roman jurisdiction. It is the unanimous prayer of the Roman people in that district that they may be permitted to continue to lead their present life among the barbarians.[231]

Architecture

Ostrogoths

The Mausoleum of Theodoric (Italian: Mausoleo di Teodorico) is an ancient monument just outside Ravenna, Italy. It was built in 520 AD by Theodoric the Great, an Ostrogoth, as his future tomb.

The current structure of the mausoleum is divided into two decagonal orders, one above the other; both are made of Istria stone. Its roof is a single 230-tonne Istrian stone, 10 meters in diameter. Possibly as a reference to the Goths' tradition of an origin in Scandinavia, the architect decorated the frieze with a pattern found in 5th- and 6th-century Scandinavian metal adornments.[232][233] A niche leads down to a room that was probably a chapel for funeral liturgies; a stair leads to the upper floor. Located in the centre of the floor is a circular porphyry stone grave, in which Theodoric was buried. His remains were removed during Byzantine rule, when the mausoleum was turned into a Christian oratory. In the late 19th century, silting from a nearby rivulet that had partly submerged the mausoleum was drained and excavated.

The Palace of Theodoric, also in Ravenna, has a symmetrical composition with arches and monolithic marble columns, reused from previous Roman buildings. With capitals of different shapes and sizes.[234] The Ostrogoths restored Roman buildings, some of which have come down to us thanks to them.

Visigoths

During their governance of Hispania, the Visigoths built several churches of basilical or cruciform floor plan that survive, including the churches of San Pedro de la Nave in El Campillo, Santa María de Melque in San Martín de Montalbán, Santa Lucía del Trampal in Alcuéscar, Santa Comba in Bande, and Santa María de Lara in Quintanilla de las Viñas; the Visigothic crypt (the Crypt of San Antolín) in the Palencia Cathedral is a Visigothic chapel from the mid 7th century, built during the reign of Wamba to preserve the remains of the martyr Saint Antoninus of Pamiers, a Visigothic-Gallic nobleman brought from Narbonne to Visigothic Hispania in 672 or 673 by Wamba himself. These are the only remains of the Visigothic cathedral of Palencia.[235]

Reccopolis (Spanish: Recópolis), located near the tiny modern village of Zorita de los Canes in the province of Guadalajara, Castile-La Mancha, Spain, is an archaeological site of one of at least four cities founded in Hispania by the Visigoths. It is the only city in Western Europe to have been founded between the fifth and eighth centuries.[d] According to Lauro Olmo Enciso who is a professor of archaeology at the University of Alcalá, the city was ordered to build by the Visigothic king Leovigild to honor his son Reccared I and to serve as Reccared's seat as co-king in the Visigothic province of Celtiberia, to the west of Carpetania, where the main capital, Toledo, lay.

Legacy

The Goths' relationship with Sweden became an important part of Swedish nationalism, and until the 19th century, before the Gothic origin had been thoroughly researched by archaeologists, Swedish scholars considered Swedes to be the direct descendants of the Goths. Today, scholars identify this as a cultural movement called Gothicismus, which included an enthusiasm for things Old Norse.[237]

In medieval and modern Spain, the Visigoths were believed to be the progenitors of the Spanish nobility (compare Gobineau for a similar French idea). By the early 7th century, the ethnic distinction between Visigoths and Hispano-Romans had all but disappeared, but recognition of a Gothic origin, e.g. on gravestones, still survived among the nobility. The 7th century Visigothic aristocracy saw itself as bearers of a particular Gothic consciousness and as guardians of old traditions such as Germanic namegiving; probably these traditions were on the whole restricted to the family sphere (Hispano-Roman nobles were doing service for the Visigothic Royal Court in Toulouse already in the 5th century and the two branches of Spanish aristocracy had fully adopted similar customs two centuries later).[238]

Beginning in 1278, when Magnus III of Sweden ascended to the throne, a reference to Gothic origins was included in the title of the King of Sweden:

We N.N. by the Grace of God King of the Swedes, the Goths and the Vends.

In 1973, with the accession of King Carl XVI Gustaf, the title was changed to simply "King of Sweden."[239]

In all history there is nothing more romantically marvellous than the swift rise of this people to the height of greatness, or than the suddenness and the tragic completeness of their ruin.[240]

— Henry Bradley, The Story of the Goths (1888)

The Spanish and Swedish claims of Gothic origins led to a clash at the Council of Basel in 1434. Before the assembled cardinals and delegations could engage in theological discussion, they had to decide how to sit during the proceedings. The delegations from the more prominent nations argued that they should sit closest to the Pope, and there were also disputes over who were to have the finest chairs and who were to have their chairs on mats. In some cases, they compromised so that some would have half a chair leg on the rim of a mat. In this conflict, Nicolaus Ragvaldi, bishop of the Diocese of Växjö, claimed that the Swedes were the descendants of the great Goths, and that the people of Västergötland (Westrogothia in Latin) were the Visigoths and the people of Östergötland (Ostrogothia in Latin) were the Ostrogoths. The Spanish delegation retorted that it was only the "lazy" and "unenterprising" Goths who had remained in Sweden, whereas the "heroic" Goths had left Sweden, invaded the Roman empire and settled in Spain.[241][242]

In Spain, a man acting with arrogance would be said to be "haciéndose los godos" ("making himself to act like the Goths"). In Chile, Argentina, and the Canary Islands, godo was an ethnic slur used against European Spaniards, who in the early colonial period often felt superior to the people born locally (criollos).[243] In Colombia, it remains as slang for a person with conservative views.[244]

A large amount of literature has been produced on the Goths, with Henry Bradley's The Goths (1888) being the standard English-language text for many decades. More recently, Peter Heather has established himself as the leading authority on the Goths in the English-speaking world. The leading authority on the Goths in the German-speaking world is Herwig Wolfram.[245]

List of early literature on the Goths

In the sagas

- Gutasaga

- Hervarar saga ok Heiðreks (The Saga of Hervör and Heidrek)

- Hlöðskviða (The Battle of the Goths and Huns)

In Greek and Roman literature

- Ambrose.[163]

- Ammianus Marcellinus[159]

- The anonymous author(s) of the Augustan History[126][129]

- Aurelius Victor: The Caesars, a history from Augustus to Constantius II

- Cassiodorus: A lost history of the Goths used by Jordanes

- Claudian: Poems

- Epitome de Caesaribus

- Eunapius"[218]

- Eutropius: Breviary

- Eusebius[141]

- George Syncellus[124]

- Gregory of Nyssa

- Isidore of Seville in his History of the Kings of the Goths, Vandals, and Suevi[246]

- Jerome: Chronicle

- Jordanes, in his Getica[247][248]

- Julian the Apostate

- Lactantius: On the death of the Persecutors

- Olympiodorus of Thebes

- Panegyrici latini

- Paulinus the Deacon: Life of bishop Ambrose of Milan

- Paulus Orosius[249]

- Philostorgius: Greek church history

- Pliny the Elder in Natural History[80]

- Procopius[219]

- Ptolemy in Geography[91]

- Sozomen

- Strabo in Geographica[73][76]

- Synesius: De regno and De providentia.[147]

- Tacitus in Germania and Annals[83]

- Themistius: Speeches

- Theoderet of Cyrrhus

- Theodosian Code

- Zosimus[127]

See also

Notes and sources

Notes

- According to Thompson (1963), the others were (i) Victoriacum, founded by Leovigild and may survive as the city of Vitoria, but a twelfth-century foundation for this city is given in contemporary sources, (ii) Lugo id est Luceo in the Asturias, referred to by Isidore of Seville, and (iii) Ologicus (perhaps Ologitis), founded using Basque labour in 621 by Suinthila as a fortification against the Basques, is modern Olite. All of these cities were founded for military purposes and at least Reccopolis, Victoriacum, and Ologicus in celebration of victory. A possible fifth Visigothic foundation is Baiyara (perhaps modern Montoro), mentioned as founded by Reccared in the fifteenth-century geographical account, Kitab al-Rawd al-Mitar.[236]

Footnotes

Goth... [A] member of a Germanic people that overran the Roman Empire in the early centuries of the Christian era; "Goth". WordReference.com. Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary. Random House. 2021. Archived from the original on 2 December 2019. Retrieved 22 March 2021.

Goth... [O]ne of a Teutonic people who in the 3rd to 5th centuries invaded and settled in parts of the Roman Empire.; "Goth". Webster's New World College Dictionary. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. 2010. Archived from the original on 27 April 2021. Retrieved 22 March 2021.

Goth... [A]ny member of a Germanic people that invaded and conquered most of the Roman Empire in the 3d, 4th, and 5th centuries a.d.; "Goth". Lexico. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 25 July 2021. Retrieved 22 March 2021.

Goth... A member of a Germanic people that invaded the Roman Empire from the east between the 3rd and 5th centuries. The eastern division, the Ostrogoths, founded a kingdom in Italy, while the Visigoths went on to found one in Spain.; "Goth". The Free Dictionary. The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. 2016. Archived from the original on 29 March 2021. Retrieved 22 March 2021.

Goth... A member of a Germanic people who invaded the Roman Empire in the early centuries of the Christian era.; "Goth". The Free Dictionary. Random House Kernerman Webster's College Dictionary. Random House. 2016. Archived from the original on 29 March 2021. Retrieved 22 March 2021.

Goth... [A] member of a Germanic people settled N of the Black Sea in the 3rd century a.d., who, with the collapse of the Roman Empire, established kingdoms in Spain and Italy.

Goth... [A] member of an East Germanic people from Scandinavia who settled south of the Baltic early in the first millennium ad. They moved on to the Ukrainian steppes and raided and later invaded many parts of the Roman Empire from the 3rd to the 5th century.

Ammianus [...] and Jornandes [...] describe the subversion of the Gothic empire by the Huns.

Ancient sources

- Ambrose (2019). On the Holy Ghost: (De Spiritu Sancto). Amazon Digital Services LLC – KDP Print. ISBN 978-1076198747. Archived from the original on 25 July 2021. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- Eusebius (1900). The Life of Constantine. Translated by Schaff, Philip. T&T Clark. Archived from the original on 5 December 2019. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- Disputed (1932). Augustan history. Translated by Magie, David. Loeb Classical Library. Archived from the original on 25 July 2021. Retrieved 19 February 2021.

- Isidore of Seville (1970). History of the Kings of the Goths, Vandals, and Suevi. Translated by Guido Donini; Gordon B. Ford, Jr. E.J. Brill. Archived from the original on 8 May 2016. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

- Jordanes (1915). The Gothic history of Jordanes. Translated by Mierow, Charles C. Princeton University Press.

- Marcellinus, Ammianus (1862). Roman History. Translated by Yonge, Charles Duke. Bohn. Archived from the original on 5 December 2019. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- Orosius, Paulus (1773). The Anglo-Saxon Version From The Historian Orosius. John Bowyer Nichols. Archived from the original on 28 February 2021. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- Pliny (1855). The Natural History. Translated by Bostock, John. Taylor & Francis. Archived from the original on 6 November 2020. Retrieved 20 February 2021.

- Procopius (1914). History of the Wars. Translated by Dewing, Henry Bronson. Heinemann. Archived from the original on 22 December 2019. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- Ptolemy (1932). Geography. New York Public Library. Archived from the original on 25 July 2021. Retrieved 19 February 2021.

- Strabo (1903). The Natural History. Translated by Hamilton, H. C.; Falconer, W. George Bell & Sons. Archived from the original on 5 December 2020. Retrieved 20 February 2021.

- Syncellus, George (1829). Dindorf, Karl Wilhelm (ed.). Chronographia. Corpus Scriptorum Historiae Byzantinae (in Latin). Vol. 22–23. University of Bonn.

- Tacitus (1876a). Germania. Translated by Church, Alfred John; Brodribb, William Jackson. Archived from the original on 25 October 2019. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- Tacitus (1876b). The Annals. Translated by Church, Alfred John; Brodribb, William Jackson. Archived from the original on 29 September 2015. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- Zosimus (1814). New History. W. Green & T. Chaplin. Archived from the original on 5 December 2019. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

Modern sources

- Andersson, Thorsten (1998a). "Goten: § 1. Namenkundliches". In Beck, Heinrich [in German]; Steuer, Heiko [in German]; Timpe, Dieter [in German] (eds.). Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde (in German). Vol. 12. De Gruyter. pp. 402–03. ISBN 311016227X. Archived from the original on 14 June 2021. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- Andersson, Thorsten (1998b). "Gøtar" [Geats]. In Beck, Heinrich; Steuer, Heiko; Timpe, Dieter (eds.). Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde (in German). Vol. 12. De Gruyter. pp. 278–83. ISBN 311016227X. Archived from the original on 14 June 2021. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- Aubin, Hermann [in German]. "History of Europe: Greeks, Romans, and Barbarians". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Archived from the original on 31 March 2019. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- Beckwith, Christopher I. (2009). Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the Present. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1400829941. Archived from the original on 19 January 2014. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- Gillett, Andrew (2000). Deroux, Carl (ed.). "Jordanes and Ablabius". Studies in Latin Literature and Roman History. X: 479–500. Archived from the original on 25 July 2021. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- Bell, Brian (1993). Tenerife, Western Canary Islands, La Gomera, La Palma, El Hierro. APA Publications. ISBN 978-0395663158. Archived from the original on 11 December 2020. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- Bennett, William Holmes (1965). An Introduction to the Gothic Language. Ulrich's Book Store. Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- Bennett, Matthew (2004). "Goths". In Holmes, Richard; Singleton, Charles; Jones, Spencer (eds.). The Oxford Companion to Military History. Oxford University Press. p. 367. ISBN 978-0191727467. Archived from the original on 15 August 2020. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

- Bóna, István [in Hungarian] (2001). "'Forest People': The Goths in Transylvania". In Makkai, László [in Hungarian]; Mócsy, András [in Hungarian] (eds.). History of Transylvania: From the Beginning to 1606. Columbia University Press. Archived from the original on 9 September 2019. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- Bowman, Alan; Cameron, Averil; Garnsey, Peter (2005). The Cambridge Ancient History: The Crisis of Empire, AD 193–337. Vol. 12. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1139053921. Archived from the original on 10 June 2018. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- Bradley, Henry (1888). The Story of the Goths. G. P. Putnam's Sons.

- Bray, John Jefferson (1997). Gallienus: A Study in Reformist and Sexual Politics. Princeton University Press. ISBN 1862543372. Archived from the original on 11 December 2020. Retrieved 18 September 2019.

- Brink, Stefan (2002). "Sociolinguistic Perspectives And Language Contact in Proto-Nordic". In Bandle, Oskar [in German] (ed.). The Nordic Languages. Vol. 1. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 685–90. ISBN 978-3110148763.

- Brink, Stefan (2008). "People and Land in Early Scandinavia". In Garipzanov, Ildar H.; Geary, Patrick J.; Urbańczyk, Przemysław [in Polish] (eds.). Franks, Northmen, and Slavs. Cursor Mundi. Vol. 5. ISD. pp. 87–112. ISBN 978-2503526157. Archived from the original on 5 December 2020. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- Bury, J. H. (1911). The Cambridge Medieval History. Vol. 1. Cambridge University Press.

- Bury, J. H. (1913). The Cambridge Medieval History. Vol. 2. Cambridge University Press.

- Cameron, Alan; Long, Jacqueline; Sherry, Lee (1993). Barbarians and Politics at the Court of Arcadius. University of California Press. ISBN 0520065506. Archived from the original on 17 May 2015. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

- Cassia, Margherita (2019). "Between Paganism and Judaism: Early Christianity in Cappadocia". In Stephen Mitchell; Philipp Pilhofer (eds.). Early Christianity in Asia Minor and Cyprus: From the Margins to the Mainstream. Early Christianity in Asia Minor. Vol. 109. Leiden: Brill. pp. 13–48.

- Christensen, Arne Søby (2002). Cassiodorus, Jordanes and the History of the Goths. Museum Tusculanum Press. ISBN 978-8772897103. Archived from the original on 18 August 2020. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- Foss, Clive F. W. (2005). "Optimatoi". In Kazhdan, Alexander P. (ed.). The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195187922. Archived from the original on 25 February 2020. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

- Fulk, Robert D. (2018). "Provenance of the Goths". A Comparative Grammar of the Early Germanic Languages. Studies in Germanic Linguistics. Vol. 3. John Benjamins Publishing Company. pp. 21–22. ISBN 978-9027263124. Archived from the original on 14 June 2021. Retrieved 21 March 2021.

- Goffart, Walter (1980). Barbarians and Romans, A.D. 418–584: The Techniques of Accommodation. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691102313. Archived from the original on 5 December 2020. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- Goffart, Walter (1989). Rome's Fall and After. A & C Black. ISBN 978-1852850012.

- Goffart, Walter (2005). "Jordanes's Getica and the Disputed Authenticity of Gothic Origins from Scandinavia". Speculum. 80 (2): 379–98. doi:10.1017/s0038713400000038. S2CID 163064058.

- Goffart, Walter (2010). Barbarian Tides: The Migration Age and the Later Roman Empire. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0812200287. Archived from the original on 25 July 2021. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

- Guerra, M.F.; Galligaro, T.; Perea, A. (2007). "The treasure of Guarrazar: Tracing the gold supplies in the Visigothic Iberian peninsula". Archaeometry. 49 (1): 53–74. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4754.2007.00287.x.

- Halsall, Guy (2007). Barbarian Migrations and the Roman West, 376–568. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521435437. Archived from the original on 5 December 2020. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- Halsall, Guy (December 2014). "Two Worlds Become One: A 'Counter-Intuitive' View of the Roman Empire and 'Germanic' Migration". German History. Oxford University Press. 32 (4): 515–32. doi:10.1093/gerhis/ghu107. Archived from the original on 25 July 2021. Retrieved 17 January 2020.

- Heather, Peter; Matthews, John (1991). The Goths in the Fourth Century. Liverpool University Press. ISBN 0853234264. Archived from the original on 14 June 2021. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- Heather, Peter (1994). Goths and Romans 332–489. Oxford Scholarship Online. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198205357.001.0001. ISBN 978-0198205357. Archived from the original on 24 February 2020. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- Heather, Peter (1998). The Goths. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 0631209328. Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- Heather, Peter (1999). "The Creation of the Visigoths". In Heather, Peter (ed.). The Visigoths from the Migration Period to the Seventh Century. Boydell & Brewer Ltd. ISBN 978-1843830337. Archived from the original on 8 August 2020. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- Heather, Peter (2007). The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195325416. Archived from the original on 14 December 2019. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- Heather, Peter (2010). Empires and Barbarians: The Fall of Rome and the Birth of Europe. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199892266. Archived from the original on 13 November 2020. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- Heather, Peter (2012). "Goths". In Hornblower, Simon; Spawforth, Antony; Eidinow, Esther (eds.). The Oxford Classical Dictionary (4 ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 623. ISBN 978-0191735257. Archived from the original on 29 December 2019. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

- Heather, Peter (2018). "Goths". In Nicholson, Oliver (ed.). The Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity. Oxford University Press. p. 673. ISBN 978-0191744457. Archived from the original on 28 January 2020. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

- Hedeager, Lotte (2000). "Migration Period Europe: The Formation of a Political Mentality". In Nelson, Janet; Theuws, Frans (eds.). Rituals of Power: From Late Antiquity to the Early Middle Ages. Transformation of the Roman World. Vol. 8. Brill. pp. 15–58. ISBN 9004109021. Archived from the original on 14 June 2021. Retrieved 21 March 2021.

- James, Simon; Krmnicek, Stefan, eds. (2020). The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of Roman Germany. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199665730. Archived from the original on 14 June 2021. Retrieved 21 March 2021.

- Howatson, M. C. (2011). "Goths". The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature (3 ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0191739422. Archived from the original on 14 June 2021. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

- Jacobsen, Torsten Cumberland (2009). The Gothic War: Rome's Final Conflict in the West. Westholme.

- Kaliff, Anders (2008). "The Goths and Scandinavia". In Biehl, P. F.; Rassamakin, Y. Ya. (eds.). Import and Imitation in Archaeology (PDF). Beier & Beran. pp. 223–43. ISBN 978-3937517957. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2020.

- Kasperski, Robert (2015). "Too Civilized to Revert to Savages? A Study Concerning a Debate about the Goths between Procopius and Jordanes". The Mediaeval Journal. Brepols. 5 (2): 33–51. doi:10.1484/J.TMJ.5.108524.

- Kazanski, Michel (1991). Les Goths [The Goths] (in French). Éditions Errance. pp. 15–18. ISBN 2877720624. Archived from the original on 14 June 2021. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- Kershaw, Stephen P. (2013). A Brief History of the Roman Empire. Hachette UK. ISBN 978-1780330495. Archived from the original on 17 May 2015. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

- Kokowski, Andrzej (1999). Archäologie der Goten [Archaeology of the Goths] (in German). IdealMedia. ISBN 8390734184. Archived from the original on 14 June 2021. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- Kokowski, Andrzej (2007). "The Agriculture of the Goths Between the First and Fifth Centuries AD". In Barnish, Sam J.; Marazzi, Federico (eds.). The Ostrogoths from the Migration Period to the Sixth Century: An Ethnographic Perspective. The Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1843830740. Archived from the original on 5 June 2020. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- Kokowski, Andrzej (2011). "The Goths in ca. 311 AD". In Kaliff, Anders [in Swedish]; Munkhammar, Lars (eds.). Wulfila 311-2011 (PDF). Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. pp. 71–96. ISBN 978-9155486648. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 March 2020.

- Kortlandt, Frederik (2001). "The Origin of the Goths" (PDF). Amsterdamer Beiträge zur älteren Germanistik. Rodopi. 55 (1): 21–25. doi:10.1163/18756719-055-01-90000004. S2CID 160585229. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 February 2020. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- Kristinsson, Axel (2010). Expansions: Competition and Conquest in Europe Since the Bronze Age. ReykjavíkurAkademían. ISBN 978-9979992219. Archived from the original on 24 April 2016. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

- Kulikowski, Michael (2006). Rome's Gothic Wars: From the Third Century to Alaric. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1139458092. Archived from the original on 16 May 2015. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

- Lacarra, José María (1958). "Panorama de la historia urbana en la Península Ibérica desde el siglo V al X". La Città Nell'alto Medioevo. 6: 319–58. Reprinted in Estudios de alta edad media española. Valencia. 1975. pp. 25–90.

- Lehmann, Winfred Philipp (1986). A Gothic Etymological Dictionary. Brill. ISBN 9004081763. Archived from the original on 5 December 2020. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- Liebeschuetz, J. H. W. F. (2015). East and West in Late Antiquity: Invasion, Settlement, Ethnogenesis and Conflicts of Religion. Brill. ISBN 978-9004289529. Archived from the original on 25 July 2021. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- Luttwak, Edward (2009). The Grand Strategy of the Byzantine Empire. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674035195. Archived from the original on 14 June 2021. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- Maenchen-Helfen, Otto J. (1973). The World of the Huns: Studies in Their History and Culture. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520015968.

- McNeill, William H. "The Steppe". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Archived from the original on 25 October 2019. Retrieved 18 September 2019.

- Moorhead, Sam; Stuttard, David (2006). AD 410: The Year that Shook Rome. Getty Publications. ISBN 978-1606060247. Archived from the original on 17 May 2015. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

- Murdoch, Brian; Read, Malcolm Kevin (2004). Early Germanic Literature and Culture. Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 978-1571131997. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- Näsman, Ulf (2008). "Från Attila till Karl den Store". In M. Olausson (ed.). Hem till Jarlabanke: Jord, makt och evigt liv i östra Mälardalen under järnåder och medeltid (in Swedish). Lund: Historiska media. ISBN 978-9185507948.

- Olędzki, Marek (2004). "The Wielbark and Przeworsk Cultures at the Turn of the Early and Late Roman Periods" (PDF). In Friesinger, Herwig; Stuppner, Alois (eds.). Zentrum und Peripherie. Mitteilungen Der Prähistorischen Kommission. Vol. 57. Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. pp. 279–90. ISBN 978-3700133179. Archived from the original on 14 June 2021. Retrieved 21 March 2021.

- O'Callaghan, Joseph. "Spain: The Visigothic Kingdom". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Archived from the original on 24 March 2019. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- Paul, Petit; MacMullen, Ramsay. "Ancient Rome". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Archived from the original on 24 March 2019. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- Pohl, Walter (2004), Die Germanen, Enzyklopädie deutscher Geschichte, vol. 57, ISBN 978-3486701623, archived from the original on 25 July 2021, retrieved 26 August 2020

- Pritsak, Omeljan (2005). "Goths". In Kazhdan, Alexander P. (ed.). The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195187922. Archived from the original on 14 June 2021. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

- Pronk-Tiethoff, Saskia (2013). The Germanic loanwords in Proto-Slavic. Rodopi. ISBN 978-9401209847.

- Oxenstierna, Eric (1948). Die Urheimat der Goten [The Urheimat of the Goths] (in German). J.A. Barth. Archived from the original on 14 June 2021. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- Peel, Christine (2015). Guta Lag and Guta Saga: The Law and History of the Gotlanders. Routledge. ISBN 978-1138804210. Archived from the original on 14 June 2021. Retrieved 21 March 2021.

- Pohl, Walter; Reimitz, Helmut [in German] (1998). Strategies of Distinction: The Construction of the Ethnic Communities, 300–800. Brill. ISBN 9004108467. Archived from the original on 5 December 2020. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- Robinson, Orrin W. (2005). "A Brief History of the Visigoths and Ostrogoths". Old English and its Closest Relatives: A Survey of the Earliest Germanic Languages. Taylor & Francis. pp. 36–39. ISBN 0415081696. Archived from the original on 14 June 2021. Retrieved 21 March 2021.

- Rübekeil, Ludwig (2002). "Scandinavia in the Light of Ancient Tradition". In Bandle, Oskar (ed.). The Nordic Languages. Vol. 1. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 593–604. ISBN 978-3110148763.

- Schramm, Gottfried [in German] (2002). Altrusslands Anfang: historische Schlüsse aus Namen, Wörtern und Texten zum 9. und 10. Jahrhundert (in German). Rombach. ISBN 3793092682. Archived from the original on 11 December 2020. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- Simpson, J.M.Y. (2010). "Gothic". In Brown, Keith; Ogilvie, Sarah (eds.). Concise Encyclopedia of Languages of the World. pp. 459–61. ISBN 978-0080877754. Archived from the original on 5 December 2020. Retrieved 5 August 2020.

- Söderberg, Werner [in Swedish] (1896). "Nicolaus Ragvaldis tal i Basel 1434". Samlaren (in Swedish). Akademiska Boktryckeriet. 17: 187–95. Archived from the original on 13 June 2017. Retrieved 13 December 2006.

- Sprengling, Martin (1953). Third Century Iran: Sapor and Kartir. The Oriental Institute, University of Chicago. OCLC 941007640. Archived from the original on 18 September 2020. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- Stenroth, Ingmar (2015). Goternas Historia (in Swedish). Göteborg: Citytidningen CT. ISBN 978-9197419482.