Category:Philanthropy

Subcategories

This category has the following 11 subcategories, out of 11 total.

- Philanthropy by country (15 C)

A

- Awards for contributions to society (4 C, 29 P)

E

- Effective altruism (3 C, 4 P)

F

- Fundraising (6 C, 38 P)

G

- Giving (10 C, 81 P)

H

- Humanitarian and service awards (9 C, 106 P)

O

- Philanthropic organizations (6 C, 15 P)

P

- Private aid programs (20 C, 21 P)

U

- Universal basic income (4 C, 22 P)

Pages in category "Philanthropy"

The following 53 pages are in this category, out of 53 total. This list may not reflect recent changes.

C

K

P

R

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Philanthropy

| Part of a series on |

| Universalism |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Category |

Universal basic income (UBI)[note 1] is a social welfare proposal in which all citizens of a given population regularly receive a guaranteed income in the form of an unconditional transfer payment (i.e., without a means test or need to work).[2][3][4] It would be received independently of any other income. If the level is sufficient to meet a person's basic needs (i.e., at or above the poverty line), it is sometimes called a full basic income; if it is less than that amount, it may be called a partial basic income.[5] No country has yet introduced either, although there have been numerous pilot projects and the idea is discussed in many countries. Some have labelled UBI as utopian due to its historical origin.[clarification needed][6][7][8]

There are several welfare arrangements that can be considered similar to basic income, although they are not unconditional. Many countries have a system of child benefit, which is essentially a basic income for guardians of children. A pension may be a basic income for retired persons. There are also quasi-basic income programs that are limited to certain population groups or time periods, like Bolsa Familia in Brazil, which is concentrated on the poor, or the Thamarat Program in Sudan, which was introduced by the transitional government to ease the effects of the economic crisis inherited from the Bashir regime.[9] Likewise, the economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic prompted some countries to send direct payments to its citizens. The Alaska Permanent Fund is a fund for all residents of the U.S. state of Alaska which averages $1,600 annually (in 2019 currency), and is sometimes described as the only example of a real basic income in practice. A negative income tax (NIT) can be viewed as a basic income for certain income groups in which citizens receive less and less money until this effect is reversed the more a person earns.[10]

Critics claim that a basic income at an appropriate level for all citizens is not financially feasible, fear that the introduction of a basic income would lead to fewer people working, and/or consider it socially unjust that everyone should receive the same amount of money regardless of their individual need. Proponents say it is indeed financeable, arguing that such a system, instead of many individual means-tested social benefits, would eliminate a lot of expensive social administration and bureaucratic efforts, and expect that unattractive jobs would have to be better paid and their working conditions improved because there would have to be an incentive to do them when already receiving an income, which would increase the willingness to work. Advocates also argue that a basic income is fair because it ensures that everyone has a sufficient financial basis to build on and less financial pressure, thus allowing people to find work that suits their interests and strengths.[11]

Early historical examples of unconditional payments date back to antiquity, and the first proposals to introduce a regular unconditionally paid income for all citizens were developed and disseminated between the 16th and 18th centuries. After the Industrial Revolution, public awareness and support for the concept increased. At least since the mid-20th century, basic income has repeatedly been the subject of political debates. In the 21st century, several discussions are related to the debate about basic income, including those regarding automation, artificial intelligence (AI), and the future of the necessity of work. A key issue in these debates is whether automation and AI will significantly reduce the number of available jobs and whether a basic income could help prevent or alleviate such problems by allowing everyone to benefit from a society's wealth, as well as whether a UBI could be a stepping stone to a resource-based or post-scarcity economy.

History

Antiquity

In a 46 BC triumph, Roman general and dictator Julius Caesar gave each common Roman citizen 100 denarii. Following his assassination in 44 BC, Caesar's will left 300 sestertii (or 75 denarii) to each citizen.[12]

Trajan, emperor of Rome from 98–117 AD, personally gave 650 denarii (equivalent to perhaps US$430 in 2023) to all common Roman citizens who applied.[13]

16th to 18th century

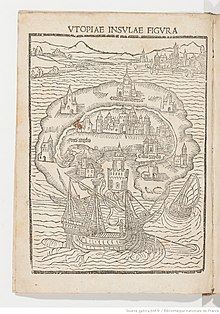

In his Utopia (1516), English statesman and philosopher Thomas More depicts a society in which every person receives a guaranteed income.[14] In this book, basic income is proposed as an answer to the statement "No penalty on earth will stop people from stealing, if it's their only way of getting food", stating:[15]

instead of inflicting these horrible punishments, it would be far more to the point to provide everyone with some means of livelihood, so that nobody's under the frightful necessity of becoming first a thief, and then a corpse.

Spanish scholar Johannes Ludovicus Vives (1492–1540) proposed that the municipal government should be responsible for securing a subsistence minimum to all its residents "not on the grounds of justice but for the sake of a more effective exercise of morally required charity." Vives also argued that to qualify for poor relief, the recipient must "deserve the help he or she gets by proving his or her willingness to work."[16] In the late 18th century, English Radical Thomas Spence and English-born American philosopher Thomas Paine both had ideas in the same direction.

Paine authored Common Sense (1776) and The American Crisis (1776–1783), the two most influential pamphlets at the start of the American Revolution. He is also the author of Agrarian Justice, published in 1797. In it, he proposed concrete reforms to abolish poverty. In particular, he proposed a universal social insurance system comprising old-age pensions and disability support, and universal stakeholder grants for young adults, funded by a 10% inheritance tax focused on land.

Early 20th century

Around 1920, support for basic income started growing, primarily in England.

Bertrand Russell (1872–1970) argued for a new social model that combined the advantages of socialism and anarchism, and that basic income should be a vital component in that new society.

Dennis and Mabel Milner, a Quaker married couple of the Labour Party, published a short pamphlet entitled "Scheme for a State Bonus" (1918) that argued for the "introduction of an income paid unconditionally on a weekly basis to all citizens of the United Kingdom." They considered it a moral right for everyone to have the means to subsistence, and thus it should not be conditional on work or willingness to work.

C. H. Douglas was an engineer who became concerned that most British citizens could not afford to buy the goods that were produced, despite the rising productivity in British industry. His solution to this paradox was a new social system he called social credit, a combination of monetary reform and basic income.

In 1944 and 1945, the Beveridge Committee, led by the British economist William Beveridge, developed a proposal for a comprehensive new welfare system of social insurance, means-tested benefits, and unconditional allowances for children. Committee member Lady Rhys-Williams argued that the incomes for adults should be more like a basic income. She was also the first to develop the negative income tax model.[17][18] Her son Brandon Rhys Williams proposed a basic income to a parliamentary committee in 1982, and soon after that in 1984, the Basic Income Research Group, now the Citizen's Basic Income Trust, began to conduct and disseminate research on basic income.[19]

Late 20th century

In his 1964 State of the Union address, U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson introduced legislation to fight the "war on poverty". Johnson believed in expanding the federal government's roles in education and health care as poverty reduction strategies. In this political climate, the idea of a guaranteed income for every American also took root. Notably, a document, signed by 1200 economists, called for a guaranteed income for every American. Six ambitious basic income experiments started up on the related concept of negative income tax. Succeeding President Richard Nixon explained its purpose as "to provide both a safety net for the poor and a financial incentive for welfare recipients to work."[20] Congress eventually approved a guaranteed minimum income for the elderly and the disabled.[20]

In the mid-1970s the main competitor to basic income and negative income tax, the Earned income tax credit (EITC), or its advocates, won over enough legislators for the US Congress to pass laws on that policy. In 1986, the Basic Income European Network, later renamed to Basic Income Earth Network (BIEN), was founded, with academic conferences every second year.[21] Other advocates included the green political movement, as well as activists and some groups of unemployed people.[22]

In the latter part of the 20th century, discussions were held around automatization and jobless growth, the possibility of combining economic growth with ecologically sustainable development, and how to reform the welfare state bureaucracy. Basic income was interwoven in these and many other debates. During the BIEN academic conferences, there were papers about basic income from a wide variety of perspectives, including economics, sociology, and human rights approaches.

21st century

In recent years the idea has come to the forefront more than before. The Swiss referendum about basic income in Switzerland 2016 was covered in media worldwide, despite its rejection.[23] Famous business people like Elon Musk,[24] Pierre Omidyar,[25] and Andrew Yang have lent their support, as have high-profile politicians like Jeremy Corbyn[26] and Tulsi Gabbard.[27]

In 2019, in California, then-Stockton Mayor Michael Tubbs initiated an 18-month pilot program of guaranteed income for 125 residents as part of the privately-funded S.E.E.D. project there.[28]

In the 2020 Democratic Party primaries, political newcomer Andrew Yang touted basic income as his core policy. His policy, referred to as a "Freedom Dividend", would have provided adult American citizens US$1,000 a month independent of employment status.[29]

On 21 January 2021, in California, the two-year donor-funded Compton Pledge[28] began distributing monthly guaranteed income payments to a "pre-verified" pool of low-income residents,[28] in a program gauged for a maximum of 800 recipients, at which point it will be one of the larger among 25 U.S. cities exploring this approach to community economics.

Beginning in December 2021, Tacoma, Washington, piloted "Growing Resilience in Tacoma" (GRIT), a guaranteed income initiative that provides $500 a month to 110 families. GRIT is part of the University of Pennsylvania's Center for Guaranteed Income Research larger study. A report on the results of the GRIT experiment will be published in 2024.[30]

Response to COVID-19

As a response to the COVID-19 pandemic and related economic impact, universal basic income and similar proposals such as helicopter money and cash transfers were increasingly discussed across the world.[31] Most countries implemented forms of partial unemployment schemes, which effectively subsidized workers' incomes without a work requirement. Around ninety countries and regions including the United States, Spain, Hong Kong, and Japan introduced temporary direct cash transfer programs to their citizens.[32][33]

In Europe, a petition calling for an "emergency basic income" gathered more than 200,000 signatures,[34] and polls suggested widespread support in public opinion for it.[35][36] Unlike the various stimulus packages of the US administration, the EU's stimulus plans did not include any form of income-support policies.[37]

Pope Francis has stated in response to the economic harm done to workers by the pandemic that "this may be the time to consider a universal basic wage".[38]

Basic income vs negative income tax

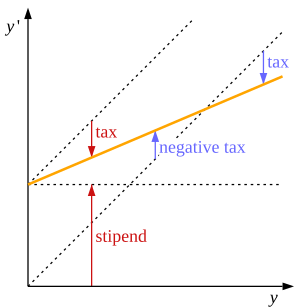

The diagram shows a basic income/negative tax system combined with flat income tax (the same percentage in tax for every income level).

Y is here the pre-tax salary given by the employer and y' is the net income.

Negative income tax

For low earnings, there is no income tax in the negative income tax system. They receive money, in the form of a negative income tax, but they don't pay any tax. Then, as their labour income increases, this benefit, this money from the state, gradually decreases. That decrease is to be seen as a mechanism for the poor, instead of the poor paying tax.

Basic income

That is, however, not the case in the corresponding basic income system in the diagram. There everyone typically pays income taxes. But on the other hand, everyone also gets the same amount of basic income.

But the net income is the same

But, as the orange line in the diagram shows, the net income is anyway the same. No matter how much or how little one earns, the amount of money one gets in one's pocket is the same, regardless of which of these two systems are used.

Basic income and negative income tax are generally seen to be similar in economic net effects, but there are some differences:

- Psychological. Philip Harvey accepts that "both systems would have the same redistributive effect and tax earned income at the same marginal rate" but does not agree that "the two systems would be perceived by taxpayers as costing the same".[39]: 15, 13

- Tax profile. Tony Atkinson made a distinction based on whether the tax profile was flat (for basic income) or variable (for NIT).[40]

- Timing. Philippe Van Parijs states that "the economic equivalence between the two programs should not hide the fact that they have different effects on recipients because of the different timing of payments: ex-ante in Basic Income, ex-post in Negative Income Tax".[41]

Perspectives and arguments

Automation

There is a prevailing opinion that we are in an era of technological unemployment – that technology is increasingly making skilled workers obsolete.

Prof. Mark MacCarthy (2014)[42]

One central rationale for basic income is the belief that automation and robotisation could result in technological unemployment, leading to a world with fewer paid jobs. A key question in this context is whether a basic income could help prevent or alleviate such problems by allowing everyone to benefit from a society's wealth, as well as whether a UBI could be a stepping stone to a resource-based or post-scarcity economy.[24][43][44][45]

U.S. presidential candidate and nonprofit founder Andrew Yang has stated that automation caused the loss of 4 million manufacturing jobs and advocated for a UBI (which he calls a Freedom Dividend) of $1,000/month rather than worker retraining programs.[46] Yang has stated that he is heavily influenced by Martin Ford. Ford, in his turn, believes that the emerging technologies will fail to deliver a lot of employment; on the contrary, because the new industries will "rarely, if ever, be highly labor-intensive".[47] Similar ideas have been debated many times before in history—that "the machines will take the jobs"—so the argument is not new. But what is quite new is the existence of several academic studies that do indeed forecast a future with substantially less employment, in the decades to come.[48][49][50] Additionally, President Barack Obama has stated that he believes that the growth of artificial intelligence will lead to an increased discussion around the idea of "unconditional free money for everyone".[51]

Economics and costs

Some proponents of UBI have argued that basic income could increase economic growth because it would sustain people while they invest in education to get higher-skilled and well-paid jobs.[52][53] However, there is also a discussion of basic income within the degrowth movement, which argues against economic growth.[54]

Advocates contend that the guaranteed financial security of a UBI will increase the population's willingness to take risks,[55] which would create a culture of inventiveness and strengthen the entrepreneurial spirit.[56]

The cost of a basic income is one of the biggest questions in the public debate as well as in the research and depends on many things. It first and foremost depends on the level of the basic income as such, and it also depends on many technical points regarding exactly how it is constructed.

While opponents claim that a basic income at an adequate level for all citizens cannot be financed, their supporters propose that it could indeed be financed, with some advocating a strong redistribution and restructuring of bureaucracy and administration for this purpose.[57]

According to the George Gibbs Chair in Political Economy and Senior Research Fellow at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University and nationally syndicated columnist[58][59] Veronique de Rugy's statements made in 2016, as of 2014, the annual cost of a UBI in the US would have been about $200 billion cheaper than the US system put in place at that date. By 2020, it would have been nearly a trillion dollars cheaper.[60]

American economist Karl Widerquist argues that simply multiplying the amount of the grant by the population would be a naive calculation, as this is the gross costs of UBI and does not take into account that UBI is a system where people pay taxes on a regular basis and receive the grant at the same time.[61]

According to Swiss economist Thomas Straubhaar, the concept of UBI is basically financeable without any problems. He describes it as "at its core, nothing more than a fundamental tax reform" that "bundles all social policy measures into a single instrument, the basic income paid out unconditionally."[62] He also considers a universal basic income to be socially just, arguing, although all citizens would receive the same amount in the form of the basic income at the beginning of the month, the rich would have lost significantly more money through taxes at the end of the month than they would have received through the basic income, while the opposite is the case for poorer people, similar to the concept of a negative income tax.[62]

Inflation of labor and rental costs

One of the most common arguments against UBI stems from the upward pressure on prices, in particular for labor and housing rents, which would likely cause inflation.[63] Public policy choices such as rent controls would likely affect the inflationary potential of universal basic income.[63]

Work

Many critics of basic income argue that people, in general, will work less, which in turn means less tax revenue and less money for the state and local governments.[64][65][66][67] Although it is difficult to know for sure what will happen if a whole country introduces basic income, there are nevertheless some studies who have attempted to look at this question:

- In negative income tax experiments in the United States in 1970 there was a five percent decline in the hours worked. The work reduction was largest for second earners in two-earner households and weakest for primary earners. The reduction in hours was higher when the benefit was higher.[65]

- In the Mincome experiment in rural Dauphin, Manitoba, also in the 1970s, there were slight reductions in hours worked during the experiment. However, the only two groups who worked significantly less were new mothers, and teenagers working to support their families. New mothers spent this time with their infant children, and working teenagers put significant additional time into their schooling.[68]

- A study from 2017 showed no evidence that people worked less because of the Iranian subsidy reform (a basic income reform).[69]

Regarding the question of basic income vs jobs, there is also the aspect of so-called welfare traps. Proponents of basic income often argue that with a basic income, unattractive jobs would necessarily have to be better paid and their working conditions improved, so that people still do them without need, reducing these traps.[70]

Philosophy and morality

By definition, universal basic income does not make a distinction between "deserving" and "undeserving" individuals when making payments. Opponents argue that this lack of discrimination is unfair: "Those who genuinely choose idleness or unproductive activities cannot expect those who have committed to doing productive work to subsidize their livelihood. Responsibility is central to fairness."[71]

Proponents usually view UBI as a fundamental human right that enables an adequate standard of living which every citizen should have access to in modern society.[72] It would be a kind of foundation guaranteed for everyone, on which one could build and never fall below that subsistence level.

It is also argued that this lack of discrimination between those who supposedly deserve it and those who don't is a way to reduce social stigma.[71]

In addition, proponents of UBI may argue that the "deserving" and "undeserving" categories are a superficial classification, as people who are not in regular gainful employment also contribute to society, e.g. by raising children, caring for people, or doing other value-creating activities which are not institutionalized. UBI would provide a balance here and thus overcomes a concept of work that is reduced to pure gainful employment and disregards sideline activities too much.[73]

Health and poverty

The first comprehensive systematic review of the health impact of basic income (or rather unconditional cash transfers in general) in low- and middle-income countries, a study that included 21 studies of which 16 were randomized controlled trials, found a clinically meaningful reduction in the likelihood of being sick by an estimated 27%. Unconditional cash transfers, according to the study, may also improve food security and dietary diversity. Children in recipient families are also more likely to attend school and the cash transfers may increase money spent on health care.[74] A 2022 update of this landmark review confirmed these findings based on a grown body of evidence (35 studies, the majority being large randomized controlled trials) and additionally found sufficient evidence that unconditional cash transfers also reduce the likelihood of living in extreme poverty.[75]

The Canadian Medical Association passed a motion in 2015 in clear support of basic income and for basic income trials in Canada.[76]

Advocates

Pilot programs and experiments

Since the 1960s, but in particular, since the late 2000s, several pilot programs and experiments on basic income have been conducted. Some examples include:

1960s−1970s

- Experiments with negative income tax in the United States and Canada in the 1960s and 1970s.

- The province of Manitoba, Canada experimented with Mincome, a basic guaranteed income, in the 1970s. In the town of Dauphin, Manitoba, labor only decreased by 13%, much less than expected.[77][78]

2000−2009

- The basic income grant in Namibia launched in 2008 and ended in 2009.[79]

- An independent pilot implemented in São Paulo, Brazil launched in 2009.[80]

2010−2019

- Basic income trials run in 2011-2012 in several villages in India,[81] whose government has proposed a guaranteed basic income for all citizens.[82] It was found that basic income in the region raised the education rate of young people by 25%.[83]

- Iran introduced a national basic income program in the autumn of 2010. It is paid to all citizens and replaces the gasoline subsidies, electricity, and some food products,[84] that the country applied for years to reduce inequalities and poverty. The sum corresponded in 2012 to approximately US$40 per person per month, US$480 per year for a single person, and US$2,300 for a family of five people.[85][86]

- In Spain, the ingreso mínimo vital, the income guarantee system, is an economic benefit guaranteed by the social security in Spain, but in 2016 was considered in need of reform.[87]

- In South Korea the Youth Allowance Program was started in 2016 in the City of Seongnam, which would give every 24-year-old citizen 250,000 won (~215 USD) every quarter in the form of a "local currency" that could only be used in local businesses. This program was later expanded to the entire Province of Gyeonggi in 2018.[88][89]

- The GiveDirectly experiment in a disadvantaged village of Nairobi, Kenya, benefitting over 20,000 people living in rural Kenya, is the longest-running basic income pilot as of November 2017, which is set to run for 12 years.[90][91][92]

- A project called Eight in a village in Fort Portal, Uganda, that a nonprofit organization launched in January 2017, which provides income for 56 adults and 88 children through mobile money.[93]

- A two-year pilot the Finnish government began in January 2017 which involved 2,000 subjects[94][95] In April 2018, the Finnish government rejected a request for funds to extend and expand the program from Kela (Finland's social security agency).[96]

- An experiment in the city of Utrecht, Netherlands launched in early 2017, that is testing different rates of aid.[82]

- A three-year basic income pilot that the Ontario provincial government, Canada, launched in the cities of Hamilton, Thunder Bay and Lindsay in July 2017.[97] Although called basic income, it was only made available to those with a low income and funding would be removed if they obtained employment,[98] making it more related to the current welfare system than true basic income. The pilot project was canceled on 31 July 2018 by the newly elected Progressive Conservative government under Ontario Premier Doug Ford.

- In Israel, in 2018 a non-profit initiative GoodDollar started with an objective to build a global economic framework for providing universal, sustainable, and scalable basic income through the new digital asset technology of blockchain. The non-profit aims to launch a peer-to-peer money transfer network in which money can be distributed to those most in need, regardless of their location, based on the principles of UBI. The project raised US$1 million from a financial company.[99][100]

- The Rythu Bandhu scheme is a welfare scheme started in the state of Telangana, India, in May 2018, aimed at helping farmers. Each farm owner receives 4,000 INR per acre twice a year for rabi and kharif harvests. To finance the program a budget allocation of 120 billion INR (US$1.55 Billion as of May 2022) was made in the 2018–2019 state budget.[101]

2020−present

- Swiss non-profit Social Income started paying out basic incomes in the form of mobile money in 2020 to people in need in Sierra Leone. Contributions finance the international initiative from people worldwide, who donate 1% of their monthly paychecks.[102]

- In May 2020, Spain introduced a minimum basic income, reaching about 2% of the population, in response to COVID-19 in order to "fight a spike in poverty due to the coronavirus pandemic". It is expected to cost state coffers three billion euros ($3.5 billion) a year."[103]

- In August 2020, a project in Germany started that gives a 1,200 Euros monthly basic income in a lottery system to citizens who applied online. The crowdsourced project will last three years and be compared against 1,380 people who do not receive basic income.[104]

- In October 2020, HudsonUP[105] was launched in Hudson, New York, by The Spark of Hudson[106] and Humanity Forward Foundation[107] to give $500 monthly basic income to 25 residents. It will last five years and be compared against 50 people who are not receiving basic income.

- In May 2021, the government of Wales, which has devolved powers in matters of Social Welfare within the UK, announced the trialling of a universal basic income scheme to "see whether the promises that basic income holds out are genuinely delivered".[108] From July 2022 over 500 people leaving care in Wales were offered £1600 per month in a 3-year £20 million pilot scheme, to evaluate the effect on the lives of those involved in the hope of providing independence and security to people.[109]

- In July 2022, Chicago began a year-long guaranteed income program by sending $500 to 5,000 households for one year in a lottery system to citizens who applied online.[110] A similar program was launched in late 2022 by Cook County, Illinois (which encompasses the entirety of Chicago as well as several suburbs) which sent monthly $500 payments to 3,250 residents with a household income at or below 250% of the federal poverty level for two years.[111]

Payments with similarities

Alaska Permanent Fund

The Permanent Fund of Alaska in the United States provides a kind of yearly basic income based on the oil and gas revenues of the state to nearly all state residents. More precisely the fund resembles a sovereign wealth fund, investing resource revenues into bonds, stocks, and other conservative investment options with the intent to generate renewable revenue for future generations. The fund has had a noticeable yet diminishing effect on reducing poverty among rural Alaska Indigenous people, notably in the elderly population.[112] However, the payment is not high enough to cover basic expenses, averaging $1,600 annually per resident in 2019 currency[113] (it has never exceeded $2,100), and is not a fixed, guaranteed amount. For these reasons, it is not always considered a basic income. However, some consider it to be the only example of a real basic income.[114][115]

Wealth Partaking Scheme

Macau's Wealth Partaking Scheme provides some annual basic income to permanent residents, funded by revenues from the city's casinos. However, the amount disbursed is not sufficient to cover basic living expenses, so it is not considered a basic income.[116]

Bolsa Família

Bolsa Família is a large social welfare program in Brazil that provides money to many low-income families in the country. The system is related to basic income, but has more conditions, like asking the recipients to keep their children in school until graduation. As of March 2020, the program covers 13.8 million families, and pays an average of $34 per month, in a country where the minimum wage is $190 per month.[117]

Other welfare programs

- Pension: A payment that in some countries is guaranteed to all citizens above a certain age. The difference from true basic income is that it is restricted to people over a certain age.

- Child benefit: A program similar to pensions but restricted to parents of children, usually allocated based on the number of children.

- Conditional cash transfer: A regular payment given to families, but only to the poor. It is usually dependent on basic conditions such as sending their children to school or having them vaccinated. Programs include Bolsa Família in Brazil and Programa Prospera in Mexico.

- Guaranteed minimum income differs from a basic income in that it is restricted to those in search of work and possibly other restrictions, such as savings being below a certain level. Example programs are unemployment benefits in the UK, the revenu de solidarité active in France, and citizens' income in Italy.

Petitions, polls and referendums

- 2008: An official petition for basic income was launched in Germany by Susanne Wiest.[118] The petition was accepted, and Susanne Wiest was invited for a hearing at the German parliament's Commission of Petitions. After the hearing, the petition was closed as "unrealizable".[119]

- 2013–2014: A European Citizens' Initiative collected 280,000 signatures demanding that the European Commission study the concept of an unconditional basic income.[120]

- 2015: A citizen's initiative in Spain received 185,000 signatures, short of the required number to mandate that the Spanish parliament discuss the proposal.[121]

- 2016: The world's first universal basic income referendum in Switzerland on 5 June 2016 was rejected with a 76.9% majority.[122][123] Also in 2016, a poll showed that 58% of the EU's population is aware of basic income, and 64% would vote in favour of the idea.[124]

- 2017: Politico/Morning Consult asked 1,994 Americans about their opinions on several political issues including national basic income; 43% either "strongly supported" or "somewhat supported" the idea.[125]

- 2018: The results of a poll by Gallup conducted last year between September and October were published. 48% of respondents supported universal basic income.[126]

- 2019: In November, an Austrian initiative received approximately 70,000 signatures but failed to reach the 100,000 signatures needed for a parliamentary discussion. The initiative was started by Peter Hofer. His proposal suggested a basic income sourced from a financial transaction tax, of €1,200, for every Austrian citizen.[127]

- 2020: A study by Oxford University found that 71% of Europeans are now in favour of basic income. The study was conducted in March, with 12,000 respondents and in 27 EU-member states and the UK.[128] A YouGov poll likewise found a majority for universal basic income in United Kingdom[129] and a poll by University of Chicago found that 51% of Americans aged 18–36 support a monthly basic income of $1,000.[130] In the UK there was also a letter, signed by over 170 MPs and Lords from multiple political parties, calling on the government to introduce a universal basic income during the COVID-19 pandemic.[131]

- 2020: A Pew Research Center survey, conducted online in August 2020, of 11,000 U.S. adults found that a majority (54%) oppose the federal government providing a guaranteed income of $1,000 per month to all adults, while 45% support it.[132]

- 2020: In a poll by Hill-HarrisX, 55% of Americans voted in favour of UBI in August, up from 49% in September 2019 and 43% in February 2019.[133]

- 2020: The results of an online survey of 2,031 participants conducted in 2018 in Germany were published: 51% were either "very much in favor" or "in favor" of UBI being introduced.[134]

- 2021: A Change.org petition calling for monthly stimulus checks in the amount of $2,000 per adult and $1,000 per child for the remainder of the COVID-19 pandemic had received almost 3 million signatures.[135]

See also

- Citizen's dividend

- Economic, social and cultural rights

- Equality of outcome

- Estovers

- FairTax § monthly tax rebate

- Geolibertarianism

- Global basic income

- Happiness economics

- Humanistic economics

- Involuntary unemployment

- Job guarantee

- Left-libertarianism

- Limitarianism (ethical)

- Living wage

- Moral universalism

- New Cuban economy

- Old Age Security

- Participation income

- Post-work society

- Quatinga Velho

- Rationing

- Social safety net

- Speenhamland system

- The Triple Revolution

- Universal Credit

- Universal value

- Universalism

- Wage subsidy

- Welfare capitalism

- Workfare

- Working time

References

...in order to pay for meaningful retraining, if retraining works. My plan is to just give everyone $1,000 a month, and then have the economy geared more to serve human goals and needs.

[See graphs] The annual check this year will be delivered to 631,000 Alaskans, most of the state population, and come largely from earnings of the state's $64 billion fund that for decades has been seeded with income from oil-production revenue. ... This year's dividend amount, similar to last year's, is in line with the average annual payment since they began at $1,000 in 1982 when inflation is taken into account, said Mouhcine Guettabi, an economist with the University of Alaska Anchorage Institute of Social and Economic Research.

Family allowance - Brazil is renowned for its massive, nearly 2-decade-old cash-transfer program for the poor, Bolsa Família (often translated as "family allowance"). As of March, it reached 13.8 million families, paying an average of $34 per month. (The national minimum wage is about $190 per month.)

- Shalvey, Kevin (4 July 2021). "Stimulus-check petitions calling for the 4th round of $2,000 monthly payments gain almost 3 million signatures". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 4 July 2021. Retrieved 4 July 2021.

Notes

- Also variously known as unconditional basic income, citizen's basic income, basic income guarantee, basic living stipend, guaranteed annual income,[1] universal income security program, or universal demogrant

Further reading

- Ailsa McKay, The Future of Social Security Policy: Women, Work and a Citizens Basic Income, Routledge, 2005, ISBN 9781134287185.

- Benjamin M. Friedman, "Born to Be Free" (review of Philippe Van Parijs and Yannick Vanderborght, Basic Income: A Radical Proposal for a Free Society and a Sane Economy, Harvard University Press, 2017), The New York Review of Books, vol. LXIV, no. 15 (12 October 2017), pp. 39–41.

- Bryce Covert, "What Money Can Buy: The promise of a universal basic income – and its limitations", The Nation, vol. 307, no. 6 (10 / 17 September 2018), pp. 33–35.

- Colombino, U. (2015). "Five Crossroads on the Way to Basic Income: An Italian Tour" (PDF). Italian Economic Journal. 1 (3): 353–389. doi:10.1007/s40797-015-0018-3. S2CID 26507450. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 December 2022. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- Ewan McGaughey, 'Will Robots Automate Your Job Away? Full Employment, Basic Income, and Economic Democracy Archived 24 May 2018 at the Wayback Machine' (2018) SSRN Archived 24 May 2018 at the Wayback Machine, part 4(2).

- John Lanchester, "Good New Idea: John Lanchester makes the case for Universal Basic Income" (discusses 8 books, published between 2014 and 2019, comprehensively advocating Universal Basic Income), London Review of Books, vol. 41, no. 14 (18 July 2019), pp. 5–8.

- Karl Widerquist, ed., Exploring the Basic Income Guarantee Archived 23 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine, (book series), Palgrave Macmillan.

- Karl Widerquist, Independence, Propertylessness, and Basic Income: A Theory of Freedom as the Power to Say No Archived 16 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine, New York, Palgrave Macmillan, March 2013. Early drafts of each chapter are available online for free at this link Archived 13 June 2017 at the Wayback Machine.

- Karl Widerquist, Jose Noguera, Yannick Vanderborght, and Jurgen De Wispelaere (editors). Basic Income: An Anthology of Contemporary Research Archived 14 September 2019 at the Wayback Machine, Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2013.

- Lowrey, Annie (2018). Give People Money: How a Universal Basic Income Would End Poverty, Revolutionize Work, and Remake the World. Crown. ISBN 978-1524758769.

- Marinescu, Ioana (February 2018). "No Strings Attached: The Behavioral Effects of U.S. Unconditional Cash Transfer Programs". NBER Working Paper No. 24337. doi:10.3386/w24337.

- Paul O'Brien, Universal Basic Income: Pennies from Heaven, The History Press, 2017, ISBN 978 1 84588 367 6.

External links

- Basic Income Earth Network

- Basic Income India

- Basic Income Lab (BIL)

- Citizen’s Basic Income Trust

- Red Humanista por la Renta Básica Universal (in Spanish)

- Unconditional Basic Income Europe

- v:Should universal basic income be established?

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Universal_basic_income

Egalitarianism (from French égal 'equal'), or equalitarianism,[1][2] is a school of thought within political philosophy that builds on the concept of social equality, prioritizing it for all people.[3] Egalitarian doctrines are generally characterized by the idea that all humans are equal in fundamental worth or moral status.[4] Egalitarianism is the doctrine that all citizens of a state should be accorded exactly equal rights.[5] Egalitarian doctrines have motivated many modern social movements and ideas, including the Enlightenment, feminism, civil rights, and international human rights.[6]

The term egalitarianism has two distinct definitions in modern English,[7] either as a political doctrine that all people should be treated as equals and have the same political, economic, social and civil rights,[8] or as a social philosophy advocating the removal of economic inequalities among people, economic egalitarianism, or the decentralization of power. Sources define egalitarianism as equality reflecting the natural state of humanity.[9][10][11]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Egalitarianism

Category:Egalitarianism

Subcategories

This category has the following 8 subcategories, out of 8 total.

A

- Agriculturalism (5 P)

E

- Equality rights (10 C, 46 P)

G

- Gender equality (12 C, 157 P)

S

- Social privilege (3 C, 29 P)

U

- Universal basic income (4 C, 22 P)

W

- Women, Life, Freedom (4 P)

Pages in category "Egalitarianism"

The following 63 pages are in this category, out of 63 total. This list may not reflect recent changes.

E

- Egalitarian cake-cutting

- Egalitarian dialogue

- Egalitarian equivalence

- Egalitarian item allocation

- Egalitarian rule

- Egalitarianism as a Revolt Against Nature and Other Essays

- Empowerment

- Equal justice under law

- Equal opportunity

- Equal Protection Clause

- Equality before the law

- Equality feminism

- Equality of autonomy

- Equality of outcome

- Equality of sacrifice

- Equinet

S

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Egalitarianism

A utopia (/juːˈtoʊpiə/ yoo-TOH-pee-ə) typically describes an imaginary community or society that possesses highly desirable or nearly perfect qualities for its members.[1] It was coined by Sir Thomas More for his 1516 book Utopia, describing a fictional island society in the New World. However, it may also denote an intentional community.

Hypothetical utopias focus on—amongst other things—equality, in such categories as economics, government and justice, with the method and structure of proposed implementation varying based on ideology.[2] Lyman Tower Sargent argues that the nature of a utopia is inherently contradictory because societies are not homogeneous and have desires which conflict and therefore cannot simultaneously be satisfied. To quote:

There are socialist, capitalist, monarchical, democratic, anarchist, ecological, feminist, patriarchal, egalitarian, hierarchical, racist, left-wing, right-wing, reformist, free love, nuclear family, extended family, gay, lesbian and many more utopias [ Naturism, Nude Christians, ...] Utopianism, some argue, is essential for the improvement of the human condition. But if used wrongly, it becomes dangerous. Utopia has an inherent contradictory nature here.

— Lyman Tower Sargent, Utopianism: A very short introduction (2010)[3]

The opposite of a utopia is a dystopia. Utopian and dystopian fiction has become a popular literary category. Despite being common parlance for something imaginary, utopianism inspired and was inspired by some reality-based fields and concepts such as architecture, file sharing, social networks, universal basic income, communes, open borders and even pirate bases.

Etymology and history

The word utopia was coined in 1516 from Ancient Greek by the Englishman Sir Thomas More for his Latin text Utopia. It literally translates as “no place”, coming from the Greek: οὐ (“not”) and τόπος (“place”), and meant any non-existent society, when ‘described in considerable detail’.[4] However, in standard usage, the word's meaning has shifted and now usually describes a non-existent society that is intended to be viewed as considerably better than contemporary society.[5]

In his original work, More carefully pointed out the similarity of the word to eutopia, meaning “good place”, from Greek: εὖ (“good” or “well”) and τόπος (“place”), which ostensibly would be the more appropriate term for the concept in modern English. The pronunciations of eutopia and utopia in English are identical, which may have given rise to the change in meaning.[5][6] Dystopia, a term meaning "bad place" coined in 1868, draws on this latter meaning. The opposite of a utopia, dystopia is a concept which surpassed utopia in popularity in the fictional literature from the 1950s onwards, chiefly because of the impact of George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four.

In 1876, writer Charles Renouvier published a novel called Uchronia (French Uchronie).[7] The neologism, using chronos instead of topos, has since been used to refer to non-existent idealized times in fiction, such as Philip Roth's The Plot Against America (2004),[8] and Philip K. Dick's The Man in the High Castle (1962).[9]

According to the Philosophical Dictionary, proto-utopian ideas begin as early as the period of ancient Greece and Rome, medieval heretics, peasant revolts and establish themselves in the period of the early capitalism, reformation and Renaissance (Hus, Müntzer, More, Campanella), democratic revolutions (Meslier, Morelly, Mably, Winstanley, later Babeufists, Blanquists,) and in a period of turbulent development of capitalism that highlighted antagonisms of capitalist society (Saint-Simon, Fourier, Owen, Cabet, Lamennais, Proudhon and their followers).[10]

Definitions and interpretations

Famous writers about utopia:

- "There is nothing like a dream to create the future. Utopia to-day, flesh and blood tomorrow." —Victor Hugo

- "A map of the world that does not include Utopia is not worth even glancing at, for it leaves out the one country at which Humanity is always landing. And when Humanity lands there, it looks out, and, seeing a better country, sets sail. Progress is the realisation of Utopias." —Oscar Wilde

- "Utopias are often only premature truths." —Alphonse De Lamartine

- "None of the abstract concepts comes closer to fulfilled utopia than that of eternal peace." —Theodor W. Adorno

- "I think that there is always a part of utopia in any romantic relationship." —Pedro Almodovar

- "In ourselves alone the absolute light keeps shining, a sigillum falsi et sui, mortis et vitae aeternae [false signal and signal of eternal life and death itself], and the fantastic move to it begins: to the external interpretation of the daydream, the cosmic manipulation of a concept that is utopian in principle." —Ernst Bloch

- "When I die, I want to die in a Utopia that I have helped to build." —Henry Kuttner

- "A man must be far gone in Utopian speculations who can seriously doubt that if these [United] States should either be wholly disunited, or only united in partial confederacies, the subdivisions into which they might be thrown would have frequent and violent contests with each other." —Alexander Hamilton, Federalist No. 6.

- "Most dictionaries associate utopia with ideal commonwealths, which they characterize as an empirical realization of an ideal life in an ideal society. Utopias, especially social utopias, are associated with the idea of social justice." — Lukáš Perný [11]

Utopian socialist Etienne Cabet in his utopian book The Voyage to Icaria cited the definition from the contemporary Dictionary of ethical and political sciences:

Utopias and other models of government, based on the public good, may be inconceivable because of the disordered human passions which, under the wrong governments, seek to highlight the poorly conceived or selfish interest of the community. But even though we find it impossible, they are ridiculous to sinful people whose sense of self-destruction prevents them from believing.

Marx and Engels used the word "utopia" to denote unscientific social theories.[12]

Philosopher Slavoj Žižek told about utopia:

Which means that we should reinvent utopia but in what sense. There are two false meanings of utopia one is this old notion of imagining this ideal society we know will never be realized, the other is the capitalist utopia in the sense of new perverse desire that you are not only allowed but even solicited to realize. The true utopia is when the situation is so without issue, without the way to resolve it within the coordinates of the possible that out of the pure urge of survival you have to invent a new space. Utopia is not kind of a free imagination utopia is a matter of inner most urgency, you are forced to imagine it, it is the only way out, and this is what we need today."[13]

Philosopher Milan Šimečka said:

... utopism was a common type of thinking at the dawn of human civilization. We find utopian beliefs in the oldest religious imaginations, appear regularly in the neighborhood of ancient, yet pre-philosophical views on the causes and meaning of natural events, the purpose of creation, the path of good and evil, happiness and misfortune, fairy tales and legends later inspired by poetry and philosophy ... the underlying motives on which utopian literature is built are as old as the entire historical epoch of human history. ”[14]

Philosopher Richard Stahel said:

... every social organization relies on something that is not realized or feasible, but has the ideal that is somewhere beyond the horizon, a lighthouse to which it may seek to approach if it considers that ideal socially valid and generally accepted."[15]

Varieties

Chronologically, the first recorded Utopian proposal is Plato's Republic.[16] Part conversation, part fictional depiction and part policy proposal, Republic would categorize citizens into a rigid class structure of "golden," "silver," "bronze" and "iron" socioeconomic classes. The golden citizens are trained in a rigorous 50-year-long educational program to be benign oligarchs, the "philosopher-kings." Plato stressed this structure many times in statements, and in his published works, such as the Republic. The wisdom of these rulers will supposedly eliminate poverty and deprivation through fairly distributed resources, though the details on how to do this are unclear. The educational program for the rulers is the central notion of the proposal. It has few laws, no lawyers and rarely sends its citizens to war but hires mercenaries from among its war-prone neighbors. These mercenaries were deliberately sent into dangerous situations in the hope that the more warlike populations of all surrounding countries will be weeded out, leaving peaceful peoples.

During the 16th century, Thomas More's book Utopia proposed an ideal society of the same name.[17] Readers, including Utopian socialists, have chosen to accept this imaginary society as the realistic blueprint for a working nation, while others have postulated that Thomas More intended nothing of the sort.[18] It is believed that More's Utopia functions only on the level of a satire, a work intended to reveal more about the England of his time than about an idealistic society.[19] This interpretation is bolstered by the title of the book and nation and its apparent confusion between the Greek for "no place" and "good place": "utopia" is a compound of the syllable ou-, meaning "no" and topos, meaning place. But the homophonic prefix eu-, meaning "good," also resonates in the word, with the implication that the perfectly "good place" is really "no place."

Mythical and religious utopias

In many cultures, societies, and religions, there is some myth or memory of a distant past when humankind lived in a primitive and simple state but at the same time one of perfect happiness and fulfillment. In those days, the various myths tell us, there was an instinctive harmony between humanity and nature. People's needs were few and their desires limited. Both were easily satisfied by the abundance provided by nature. Accordingly, there were no motives whatsoever for war or oppression. Nor was there any need for hard and painful work. Humans were simple and pious and felt themselves close to their God or gods. According to one anthropological theory, hunter-gatherers were the original affluent society.

These mythical or religious archetypes are inscribed in many cultures and resurge with special vitality when people are in difficult and critical times. However, in utopias, the projection of the myth does not take place towards the remote past but either towards the future or towards distant and fictional places, imagining that at some time in the future, at some point in space, or beyond death, there must exist the possibility of living happily.

In the United States and Europe, during the Second Great Awakening (ca. 1790–1840) and thereafter, many radical religious groups formed utopian societies in which faith could govern all aspects of members' lives. These utopian societies included the Shakers, who originated in England in the 18th century and arrived in America in 1774. A number of religious utopian societies from Europe came to the United States in the 18th and 19th centuries, including the Society of the Woman in the Wilderness (led by Johannes Kelpius (1667–1708)), the Ephrata Cloister (established in 1732) and the Harmony Society, among others. The Harmony Society was a Christian theosophy and pietist group founded in Iptingen, Germany, in 1785. Due to religious persecution by the Lutheran Church and the government in Württemberg,[20] the society moved to the United States on October 7, 1803, settling in Pennsylvania. On February 15, 1805, about 400 followers formally organized the Harmony Society, placing all their goods in common. The group lasted until 1905, making it one of the longest-running financially successful communes in American history.

The Oneida Community, founded by John Humphrey Noyes in Oneida, New York, was a utopian religious commune that lasted from 1848 to 1881. Although this utopian experiment has become better known today for its manufacture of Oneida silverware, it was one of the longest-running communes in American history. The Amana Colonies were communal settlements in Iowa, started by radical German pietists, which lasted from 1855 to 1932. The Amana Corporation, manufacturer of refrigerators and household appliances, was originally started by the group. Other examples are Fountain Grove (founded in 1875), Riker's Holy City and other Californian utopian colonies between 1855 and 1955 (Hine), as well as Sointula[21] in British Columbia, Canada. The Amish and Hutterites can also be considered an attempt towards religious utopia. A wide variety of intentional communities with some type of faith-based ideas have also started across the world.

Anthropologist Richard Sosis examined 200 communes in the 19th-century United States, both religious and secular (mostly utopian socialist). 39 percent of the religious communes were still functioning 20 years after their founding while only 6 percent of the secular communes were.[22] The number of costly sacrifices that a religious commune demanded from its members had a linear effect on its longevity, while in secular communes demands for costly sacrifices did not correlate with longevity and the majority of the secular communes failed within 8 years. Sosis cites anthropologist Roy Rappaport in arguing that rituals and laws are more effective when sacralized.[23] Social psychologist Jonathan Haidt cites Sosis's research in his 2012 book The Righteous Mind as the best evidence that religion is an adaptive solution to the free-rider problem by enabling cooperation without kinship.[24] Evolutionary medicine researcher Randolph M. Nesse and theoretical biologist Mary Jane West-Eberhard have argued instead that because humans with altruistic tendencies are preferred as social partners they receive fitness advantages by social selection,[list 1] with Nesse arguing further that social selection enabled humans as a species to become extraordinarily cooperative and capable of creating culture.[29]

The Book of Revelation in the Christian Bible depicts an eschatological time with the defeat of Satan, of Evil and of Sin. The main difference compared to the Old Testament promises is that such a defeat also has an ontological value (Rev 21:1;4: "Then I saw 'a new heaven and a new earth,' for the first heaven and the first earth had passed away, and there was no longer any sea...'He will wipe every tear from their eyes. There will be no more death' or mourning or crying or pain, for the old order of things has passed away") and no longer just gnosiological (Isaiah 65:17: "See, I will create/new heavens and a new earth./The former things will not be remembered,/nor will they come to mind").[30][31] Narrow interpretation of the text depicts Heaven on Earth or a Heaven brought to Earth without sin. Daily and mundane details of this new Earth, where God and Jesus rule, remain unclear, although it is implied to be similar to the biblical Garden of Eden. Some theological philosophers believe that heaven will not be a physical realm but instead an incorporeal place for souls.[32]

Golden Age

The Greek poet Hesiod, around the 8th century BC, in his compilation of the mythological tradition (the poem Works and Days), explained that, prior to the present era, there were four other progressively less perfect ones, the oldest of which was the Golden Age.

Scheria

Perhaps the oldest Utopia of which we know, as pointed out many years ago by Moses Finley,[33] is Homer’s Scheria, island of the Phaeacians.[34] A mythical place, often equated with classical Corcyra, (modern Corfu/Kerkyra), where Odysseus was washed ashore after 10 years of storm-tossed wandering and escorted to the King’s palace by his daughter Nausicaa. With stout walls, a stone temple and good harbours, it is perhaps the ‘ideal’ Greek colony, a model for those founded from the middle of the 8th C onward. A land of plenty, home to expert mariners (with the self-navigating ships), and skilled craftswomen who live in peace under their king's rule and fear no strangers.

Plutarch, the Greek historian and biographer of the 1st century, dealt with the blissful and mythic past of humanity.

Arcadia

From Sir Philip Sidney's prose romance The Old Arcadia (1580), originally a region in the Peloponnesus, Arcadia became a synonym for any rural area that serves as a pastoral setting, a locus amoenus ("delightful place").

The Biblical Garden of Eden

The Biblical Garden of Eden as depicted in the Old Testament Bible's Book of Genesis 2 (Authorized Version of 1611):

And the Lord God planted a garden eastward in Eden; and there he put the man whom he had formed. Out of the ground made the Lord God to grow every tree that is pleasant to the sight and good for food; the tree of life also in the midst of the garden and the tree of knowledge of good and evil. [...]

And the Lord God took the man and put him into the garden of Eden to dress it and to keep it. And the Lord God commanded the man, saying, Of every tree of the garden thou mayest freely eat: but of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, thou shalt not eat of it: for in the day that thou eatest thereof thou shalt surely die. [...]

And the Lord God said, It is not good that the man should be alone; [...] And the Lord God caused a deep sleep to fall upon Adam and he slept: and he took one of his ribs and closed up the flesh instead thereof and the rib, which the Lord God had taken from man, made he a woman and brought her unto the man.

According to the exegesis that the biblical theologian Herbert Haag proposes in the book Is original sin in Scripture?,[35] published soon after the Second Vatican Council, Genesis 2:25 would indicate that Adam and Eve were created from the beginning naked of the divine grace, an originary grace that, then, they would never have had and even less would have lost due to the subsequent events narrated. On the other hand, while supporting a continuity in the Bible about the absence of preternatural gifts (Latin: dona praeternaturalia)[36] with regard to the ophitic event, Haag never makes any reference to the discontinuity of the loss of access to the tree of life.

The Land of Cockaigne

The Land of Cockaigne (also Cockaygne, Cokaygne), was an imaginary land of idleness and luxury, famous in medieval stories and the subject of several poems, one of which, an early translation of a 13th-century French work, is given in George Ellis' Specimens of Early English Poets. In this, "the houses were made of barley sugar and cakes, the streets were paved with pastry and the shops supplied goods for nothing." London has been so called (see Cockney) but Boileau applies the same to Paris.[37] Schlaraffenland is an analogous German tradition. All these myths also express some hope that the idyllic state of affairs they describe is not irretrievably and irrevocably lost to mankind, that it can be regained in some way or other.

One way might be a quest for an "earthly paradise" – a place like Shangri-La, hidden in the Tibetan mountains and described by James Hilton in his utopian novel Lost Horizon (1933). Christopher Columbus followed directly in this tradition in his belief that he had found the Garden of Eden when, towards the end of the 15th century, he first encountered the New World and its indigenous inhabitants.[citation needed]

The Peach Blossom Spring

The Peach Blossom Spring (桃花源), a prose piece written by the Chinese poet Tao Yuanming, describes a utopian place.[38][39] The narrative goes that a fisherman from Wuling sailed upstream a river and came across a beautiful blossoming peach grove and lush green fields covered with blossom petals.[40] Entranced by the beauty, he continued upstream and stumbled onto a small grotto when he reached the end of the river.[40] Though narrow at first, he was able to squeeze through the passage and discovered an ethereal utopia, where the people led an ideal existence in harmony with nature.[41] He saw a vast expanse of fertile lands, clear ponds, mulberry trees, bamboo groves and the like with a community of people of all ages and houses in neat rows.[41] The people explained that their ancestors escaped to this place during the civil unrest of the Qin dynasty and they themselves had not left since or had contact with anyone from the outside.[42] They had not even heard of the later dynasties of bygone times or the then-current Jin dynasty.[42] In the story, the community was secluded and unaffected by the troubles of the outside world.[42]

The sense of timelessness was predominant in the story as a perfect utopian community remains unchanged, that is, it had no decline nor the need to improve.[42] Eventually, the Chinese term Peach Blossom Spring came to be synonymous for the concept of utopia.[43]

Datong

Datong is a traditional Chinese Utopia. The main description of it is found in the Chinese Classic of Rites, in the chapter called "Li Yun" (禮運). Later, Datong and its ideal of 'The World Belongs to Everyone/The World is Held in Common' 'Tianxia weigong/天下爲公' 'influenced modern Chinese reformers and revolutionaries, such as Kang Youwei.

Ketumati

It is said, once Maitreya is reborn into the future kingdom of Ketumati, a utopian age will commence.[44] The city is described in Buddhism as a domain filled with palaces made of gems and surrounded by Kalpavriksha trees producing goods. During its years, none of the inhabitants of Jambudvipa will need to take part in cultivation and hunger will no longer exist.[45]

Modern utopias

In the 21st century, discussions around utopia for some authors include post-scarcity economics, late capitalism, and universal basic income; for example, the "human capitalism" utopia envisioned in Utopia for Realists (Rutger Bregman 2016) includes a universal basic income and a 15-hour workweek, along with open borders.[46]

Scandinavian nations, which as of 2019 ranked at the top of the World Happiness Report, are sometimes cited as modern utopias, although British author Michael Booth has called that a myth and wrote a 2014 book about the Nordic countries.[47]

Economics

Particularly in the early 19th century, several utopian ideas arose, often in response to the belief that social disruption was created and caused by the development of commercialism and capitalism. These ideas are often grouped in a greater "utopian socialist" movement, due to their shared characteristics. A once common characteristic is an egalitarian distribution of goods, frequently with the total abolition of money. Citizens only do work which they enjoy and which is for the common good, leaving them with ample time for the cultivation of the arts and sciences. One classic example of such a utopia appears in Edward Bellamy's 1888 novel Looking Backward. William Morris depicts another socialist utopia in his 1890 novel News from Nowhere, written partially in response to the top-down (bureaucratic) nature of Bellamy's utopia, which Morris criticized. However, as the socialist movement developed, it moved away from utopianism; Marx in particular became a harsh critic of earlier socialism which he described as "utopian". (For more information, see the History of Socialism article.) In a materialist utopian society, the economy is perfect; there is no inflation and only perfect social and financial equality exists.

Edward Gibbon Wakefield's utopian theorizing on systematic colonial settlement policy in the early-19th century also centred on economic considerations, but with a view to preserving class distinctions;[48] Wakefield influenced several colonies founded in New Zealand and Australia in the 1830s, 1840s and 1850s.

In 1905, H.G. Wells published A Modern Utopia, which was widely read and admired and provoked much discussion. Also consider Eric Frank Russell's book The Great Explosion (1963), the last section of which details an economic and social utopia. This forms the first mention of the idea of Local Exchange Trading Systems (LETS).

During the "Khrushchev Thaw" period,[49] the Soviet writer Ivan Efremov produced the science-fiction utopia Andromeda (1957) in which a major cultural thaw took place: humanity communicates with a galaxy-wide Great Circle and develops its technology and culture within a social framework characterized by vigorous competition between alternative philosophies.

The English political philosopher James Harrington (1611-1677), author of the utopian work The Commonwealth of Oceana, published in 1656, inspired English country-party republicanism (1680s to 1740s) and became influential in the design of three American colonies. His theories ultimately contributed to the idealistic principles of the American Founders. The colonies of Carolina (founded in 1670), Pennsylvania (founded in 1681), and Georgia (founded in 1733) were the only three English colonies in America that were planned as utopian societies with an integrated physical, economic and social design. At the heart of the plan for Georgia was a concept of "agrarian equality" in which land was allocated equally and additional land acquisition through purchase or inheritance was prohibited; the plan was an early step toward the yeoman republic later envisioned by Thomas Jefferson.[50][51][52]

The communes of the 1960s in the United States often represented an attempt to greatly improve the way humans live together in communities. The back-to-the-land movements and hippies inspired many to try to live in peace and harmony on farms or in remote areas and to set up new types of governance.[53] Communes like Kaliflower, which existed between 1967 and 1973, attempted to live outside of society's norms and to create their own ideal communalist society.[54][55]

People all over the world organized and built intentional communities with the hope of developing a better way of living together. While many of these new small communities failed, some continue to grow, such as the religion-based Twelve Tribes, which started in the United States in 1972. Since its inception, it has grown into many groups around the world.

Science and technology

Though Francis Bacon's New Atlantis is imbued with a scientific spirit, scientific and technological utopias tend to be based in the future, when it is believed that advanced science and technology will allow utopian living standards; for example, the absence of death and suffering; changes in human nature and the human condition. Technology has affected the way humans have lived to such an extent that normal functions, like sleep, eating or even reproduction, have been replaced by artificial means. Other examples include a society where humans have struck a balance with technology and it is merely used to enhance the human living condition (e.g. Star Trek). In place of the static perfection of a utopia, libertarian transhumanists envision an "extropia", an open, evolving society allowing individuals and voluntary groupings to form the institutions and social forms they prefer.

Mariah Utsawa presented a theoretical basis for technological utopianism and set out to develop a variety of technologies ranging from maps to designs for cars and houses which might lead to the development of such a utopia.

One notable example of a technological and libertarian socialist utopia is Scottish author Iain Banks' Culture.

Opposing this optimism is the prediction that advanced science and technology will, through deliberate misuse or accident, cause environmental damage or even humanity's extinction. Critics, such as Jacques Ellul and Timothy Mitchell advocate precautions against the premature embrace of new technologies. Both raise questions about changing responsibility and freedom brought by division of labour. Authors such as John Zerzan and Derrick Jensen consider that modern technology is progressively depriving humans of their autonomy and advocate the collapse of the industrial civilization, in favor of small-scale organization, as a necessary path to avoid the threat of technology on human freedom and sustainability.

There are many examples of techno-dystopias portrayed in mainstream culture, such as the classics Brave New World and Nineteen Eighty-Four, often published as "1984", which have explored some of these topics.

Ecological

Ecological utopian society describes new ways in which society should relate to nature. Ecotopia: The Notebooks and Reports of William Weston from 1975 by Ernest Callenbach was one of the first influential ecological utopian novels.[56] Richard Grove's book Green Imperialism: Colonial Expansion, Tropical Island Edens and the Origins of Environmentalism 1600–1860 from 1995 suggested the roots of ecological utopian thinking.[57] Grove's book sees early environmentalism as a result of the impact of utopian tropical islands on European data-driven scientists.[58] The works on ecological eutopia perceive a widening gap between the modern Western way of living that destroys nature[59] and a more traditional way of living before industrialization.[60] Ecological utopias may advocate a society that is more sustainable. According to the Dutch philosopher Marius de Geus, ecological utopias could be inspirational sources for movements involving green politics.[61]

Feminism

Utopias have been used to explore the ramifications of genders being either a societal construct or a biologically "hard-wired" imperative or some mix of the two.[62] Socialist and economic utopias have tended to take the "woman question" seriously and often to offer some form of equality between the sexes as part and parcel of their vision, whether this be by addressing misogyny, reorganizing society along separatist lines, creating a certain kind of androgynous equality that ignores gender or in some other manner. For example, Edward Bellamy's Looking Backward (1887) responded, progressively for his day, to the contemporary women's suffrage and women's rights movements. Bellamy supported these movements by incorporating the equality of women and men into his utopian world's structure, albeit by consigning women to a separate sphere of light industrial activity (due to women's lesser physical strength) and making various exceptions for them in order to make room for (and to praise) motherhood. One of the earlier feminist utopias that imagines complete separatism is Charlotte Perkins Gilman's Herland (1915).[citation needed]

In science fiction and technological speculation, gender can be challenged on the biological as well as the social level. Marge Piercy's Woman on the Edge of Time portrays equality between the genders and complete equality in sexuality (regardless of the gender of the lovers). Birth-giving, often felt as the divider that cannot be avoided in discussions of women's rights and roles, has been shifted onto elaborate biological machinery that functions to offer an enriched embryonic experience. When a child is born, it spends most of its time in the children's ward with peers. Three "mothers" per child are the norm and they are chosen in a gender neutral way (men as well as women may become "mothers") on the basis of their experience and ability. Technological advances also make possible the freeing of women from childbearing in Shulamith Firestone's The Dialectic of Sex. The fictional aliens in Mary Gentle's Golden Witchbreed start out as gender-neutral children and do not develop into men and women until puberty and gender has no bearing on social roles. In contrast, Doris Lessing's The Marriages Between Zones Three, Four and Five (1980) suggests that men's and women's values are inherent to the sexes and cannot be changed, making a compromise between them essential. In My Own Utopia (1961) by Elizabeth Mann Borghese, gender exists but is dependent upon age rather than sex – genderless children mature into women, some of whom eventually become men.[62] "William Marston's Wonder Woman comics of the 1940s featured Paradise Island, also known as Themyscira, a matriarchal all-female community of peace, loving submission, bondage and giant space kangaroos."[63]

Utopian single-gender worlds or single-sex societies have long been one of the primary ways to explore implications of gender and gender-differences.[64] In speculative fiction, female-only worlds have been imagined to come about by the action of disease that wipes out men, along with the development of technological or mystical method that allow female parthenogenic reproduction. Charlotte Perkins Gilman's 1915 novel approaches this type of separate society. Many feminist utopias pondering separatism were written in the 1970s, as a response to the Lesbian separatist movement;[64][65][66] examples include Joanna Russ's The Female Man and Suzy McKee Charnas's Walk to the End of the World and Motherlines.[66] Utopias imagined by male authors have often included equality between sexes, rather than separation, although as noted Bellamy's strategy includes a certain amount of "separate but equal".[67] The use of female-only worlds allows the exploration of female independence and freedom from patriarchy. The societies may be lesbian, such as Daughters of a Coral Dawn by Katherine V. Forrest or not, and may not be sexual at all – a famous early sexless example being Herland (1915) by Charlotte Perkins Gilman.[65] Charlene Ball writes in Women's Studies Encyclopedia that use of speculative fiction to explore gender roles in future societies has been more common in the United States compared to Europe and elsewhere,[62] although such efforts as Gerd Brantenberg's Egalia's Daughters and Christa Wolf's portrayal of the land of Colchis in her Medea: Voices are certainly as influential and famous as any of the American feminist utopias.

See also

- List of utopian literature

- New world order (Bahá'í)

- Utopia (disambiguation)

- Utopia for Realists

- Utopian and dystopian fiction

Notes

This goodness theme is advanced most definitively through the promise of a renewal of all creation, a hope present in OT prophetic literature (Isa. 65:17–25) but portrayed most strikingly through Revelation's vision of a "new heaven and a new earth" (Rev. 21:1). There the divine king of creation promises to renew all of reality: "See, I am making all things new" (Rev. 21:5).

By alluding to the new Creation prophecy of Isaiah John emphasizes the qualitatively new state of affairs that will exist at God's new creative act. In addition to the passing of the former heaven and earth, John also asserts that the sea was no more in 21:1c.

{{cite web}}: |last= has generic name (help)

In Wakefield's utopia, land policy would limit the expansion of the frontier and regulate class relationships.

- Martha A. Bartter, The Utopian Fantastic, "Momutes", Robin Anne Reid, p. 102[ISBN missing]

- Bundled references

References

- Utopia: The History of an Idea (2020), by Gregory Claeys. London: Thames & Hudson.

- Two Kinds of Utopia, (1912) by Vladimir Lenin. www

.marxists .org /archive /lenin /works /1912 /oct /00 .htm - Development of Socialism from Utopia to Science (1870?) by Friedrich Engels.

- Ideology and Utopia: an Introduction to the Sociology of Knowledge (1936), by Karl Mannheim, translated by Louis Wirth and Edward Shils. New York, Harcourt, Brace. See original, Ideologie Und Utopie, Bonn: Cohen.

- History and Utopia (1960), by Emil Cioran.

- Utopian Thought in the Western World (1979), by Frank E. Manuel & Fritzie Manuel. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 0-674-93185-8

- California's Utopian Colonies (1983), by Robert V. Hine. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-04885-7

- The Principle of Hope (1986), by Ernst Bloch. See original, 1937–41, Das Prinzip Hoffnung

- Demand the Impossible: Science Fiction and the Utopian Imagination (1986) by Tom Moylan. London: Methuen, 1986.

- Utopia and Anti-utopia in Modern Times (1987), by Krishnan Kumar. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-16714-5

- The Concept of Utopia (1990), by Ruth Levitas. London: Allan.