Amputation is the removal of a limb by trauma, medical illness, or surgery. As a surgical measure, it is used to control pain or a disease process in the affected limb, such as malignancy or gangrene. In some cases, it is carried out on individuals as a preventive surgery for such problems. A special case is that of congenital amputation, a congenital disorder, where fetal limbs have been cut off by constrictive bands. In some countries, amputation is currently used to punish people who commit crimes.[1][2][3][4] Amputation has also been used as a tactic in war and acts of terrorism; it may also occur as a war injury. In some cultures and religions, minor amputations or mutilations are considered a ritual accomplishment.[5][6][7] When done by a person, the person executing the amputation is an amputator.[8][9] The oldest evidence of this practice comes from a skeleton found buried in Liang Tebo cave, East Kalimantan, Indonesian Borneo dating back to at least 31,000 years ago, where it was done when the amputee was a young child.[10]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amputation

An accident is an unintended, normally unwanted event that was not directly caused by humans.[1] The term accident implies that nobody should be blamed, but the event may have been caused by unrecognized or unaddressed risks. Most researchers who study unintentional injury avoid using the term accident and focus on factors that increase risk of severe injury and that reduce injury incidence and severity.[2] For example, when a tree falls down during a wind storm, its fall may not have been caused by humans, but the tree's type, size, health, location, or improper maintenance may have contributed to the result. Most car wrecks are not true accidents; however English speakers started using that word in the mid-20th century as a result of media manipulation by the US automobile industry.[3]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Accident

https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?search=rebuild+surgery&title=Special%3ASearch&ns0=1

Otofacial syndrome is an extraordinarily rare congenital deformity in which a person is born without a mandible, and, consequently, without a chin.

In nearly all cases, the child does not survive because it is unable to breathe and eat properly. Even with reconstructive surgery, the tongue is extremely underdeveloped, making unaided breathing and swallowing impossible.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Otofacial_syndrome

https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=DNA_surgery&redirect=no

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cheap_Trick

Aesthetic flat closure after mastectomy is contouring of the chest wall after mastectomy without traditional breast reconstruction.[1] Vernacular synonyms and related vernacular and technical terms include “going flat”,[2] "flat closure",[3] "optimal flat closure",[4] "nonreconstructive mastectomy",[5] “oncoplastic mastectomy”,[6] “non-skin sparing mastectomy”,[7] “mastectomy without reconstruction”,[8] and “aesthetic primary closure post-mastectomy”.[5]

Women who have decided against traditional reconstructive surgery following mastectomy have gained media visibility in recent years.[9] Media reports have covered patients' claims that their choices not to undergo reconstruction have been overridden by their surgeons.[10][11] Recent research has characterized the "going flat" movement and patient experience going flat[12][13][14] and described aesthetic flat closure surgical technique.[15][16][17]

Aesthetic flat closure is the surgical work required to produce a smooth flat chest wall contour after the removal of one or both breasts, including obliteration of the inframammary fold and excision of excess lateral tissue (to avoid "dog ears.")[18][19] It is defined by the National Cancer Institute as the following: “A type of surgery that is done to rebuild the shape of the chest wall after one or both breasts are removed. An aesthetic flat closure may also be done after removal of a breast implant that was used to restore breast shape. During an aesthetic flat closure, extra skin, fat, and other tissue in the breast area are removed. The remaining tissue is then tightened and smoothed out so that the chest wall appears flat.”[20]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Flat_closure_after_mastectomy

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

- Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

- Perestroika (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Union political movement

- Critical reconstruction, an architectural theory related to the reconstruction of Berlin after the end of the Berlin Wall

- Economic reconstruction

- Ministry of Reconstruction, a UK government department

- The Reconstruction era of the United States, the period after the Civil War, 1865–1877

- The Reconstruction Acts, or Military Reconstruction Acts, addressing requirements for Southern States to be readmitted to the Union

- Reconstruction Finance Corporation, a United States government agency from 1932 to 1957

Arts, entertainment, and media

Films

- Reconstruction (1968 film), a Romanian tragicomedy

- Reconstruction (2001 film), about the 1959 Ioanid Gang bank heist in Romania

- Reconstruction (2003 film), a Danish psychological romantic drama

Music

- Reconstruction (band), featuring Jerry Garcia, Nick Kahner and John Kahn

- Reconstruction (Hugh Masekela album), 1970

- Reconstruction (Max Romeo album), 1977

- Reconstructions (Don Diablo album)

- Reconstructions (Kerry Livgren album)

Television

- "Reconstruction" (Jericho episode)

- Red vs. Blue: Reconstruction, a machinima comedy series

Other uses in arts, entertainment, and media

- Reconstruction (magazine), a monthly edited by Allan L. Benson from 1919 to 1921

- ReConStruction, a 2010 science fiction convention

- Memorial reconstruction, a hypothesis regarding the transcription of 17th-century plays

Science and computing

- 3D reconstruction in computer vision

- Ancestral reconstruction, the analysis of organisms' relationships via genome data

- Cone beam reconstruction, a computational microtomography method

- Crime reconstruction

- Event reconstruction, the interpretation of signals from a particle detector

- Forensic facial reconstruction, the process of recreating the face of an individual from its skeletal remains

- Iterative reconstruction, methods to construct images of objects

- Reconstruction algorithm, an algorithm used in iterative reconstruction

- Reconstruction conjecture, in graph theory

- Reconstructive plastic surgery

- Shooting reconstruction

- Signal reconstruction, the determination of an original continuous signal from samples

- Single particle reconstruction, the combination of multiple images of molecules to produce a three-dimensional image

- Surface reconstruction, the process which alters atomic structure in crystal surfaces

- Tomographic reconstruction

- Vector field reconstruction, the creation of a vector field from experimental data

Other uses

- 3D sound reconstruction

- Reconstruction (architecture), the act of rebuilding a destroyed structure

- Linguistic reconstruction

See also

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reconstruction

| Polydactyly | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Hyperdactyly |

| Specialty | Medical genetics |

| Usual onset | During pregnancy |

| Duration | Lifelong unless surgically removed |

| Treatment | Surgery in some cases |

| Deaths | None |

Polydactyly or polydactylism (from Greek πολύς (polys) 'many', and δάκτυλος (daktylos) 'finger'),[1] also known as hyperdactyly, is an anomaly in humans and animals resulting in supernumerary fingers and/or toes.[2] Polydactyly is the opposite of oligodactyly (fewer fingers or toes).

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polydactyly

Anorexia is a medical term for a loss of appetite. While the term outside of the scientific literature is often used interchangeably with anorexia nervosa, many possible causes exist for a loss of appetite, some of which may be harmless, while others indicate a serious clinical condition or pose a significant risk.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anorexia_(symptom)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Artificial_organ

Artificial ventilation (also called artificial respiration) is a means of assisting or stimulating respiration, a metabolic process referring to the overall exchange of gases in the body by pulmonary ventilation, external respiration, and internal respiration.[1][2] It may take the form of manually providing air for a person who is not breathing or is not making sufficient respiratory effort,[3] or it may be mechanical ventilation involving the use of a mechanical ventilator to move air in and out of the lungs when an individual is unable to breathe on their own, for example during surgery with general anesthesia or when an individual is in a coma or trauma.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Artificial_ventilation

Artificial photosynthesis is a chemical process that biomimics the natural process of photosynthesis to convert sunlight, water, and carbon dioxide into carbohydrates and oxygen. The term artificial photosynthesis is commonly used to refer to any scheme for capturing and storing the energy from sunlight in the chemical bonds of a fuel (a solar fuel). Photocatalytic water splitting converts water into hydrogen and oxygen and is a major research topic of artificial photosynthesis. Light-driven carbon dioxide reduction is another process studied that replicates natural carbon fixation.

Research on this topic includes the design and assembly of devices for the direct production of solar fuels, photoelectrochemistry and its application in fuel cells, and the engineering of enzymes and photoautotrophic microorganisms for microbial biofuel and biohydrogen production from sunlight.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Artificial_photosynthesis

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Synthetic biology |

|---|

| Synthetic biological circuits |

| Genome editing |

| Artificial cells |

| Xenobiology |

| Other topics |

Synthetic biology (SynBio) is a multidisciplinary field of science that focuses on living systems and organisms, and it applies engineering principles to develop new biological parts, devices, and systems or to redesign existing systems found in nature.[1]

It is a branch of science that encompasses a broad range of methodologies from various disciplines, such as biotechnology, biomaterials, material science/engineering, genetic engineering, molecular biology, molecular engineering, systems biology, membrane science, biophysics, chemical and biological engineering, electrical and computer engineering, control engineering and evolutionary biology.

It includes designing and constructing biological modules, biological systems, and biological machines or, re-design of existing biological systems for useful purposes.[2]

Additionally, it is the branch of science that focuses on the new abilities of engineering into existing organisms to redesign them for useful purposes.[3]

In order to produce predictable and robust systems with novel functionalities that do not already exist in nature, it is also necessary to apply the engineering paradigm of systems design to biological systems. According to the European Commission, this possibly involves a molecular assembler based on biomolecular systems such as the ribosome.[4]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Synthetic_biology

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Timeline_of_biotechnology?wprov=srpw1_5

An artificial cell, synthetic cell or minimal cell is an engineered particle that mimics one or many functions of a biological cell. Often, artificial cells are biological or polymeric membranes which enclose biologically active materials.[1] As such, liposomes, polymersomes, nanoparticles, microcapsules and a number of other particles can qualify as artificial cells.

The terms "artificial cell" and "synthetic cell" are used in a variety of different fields and can have different meanings, as it is also reflected in the different sections of this article. Some stricter definitions are based on the assumption that the term "cell" directly relates to biological cells and that these structures therefore have to be alive (or part of a living organism) and, further, that the term "artificial" implies that these structures are artificially built from the bottom-up, i.e. from basic components. As such, in the area of synthetic biology, an artificial cell can be understood as a completely synthetically made cell that can capture energy, maintain ion gradients, contain macromolecules as well as store information and have the ability to replicate.[2] This kind of artificial cell has not yet been made.

However, in other cases, the term "artificial" does not imply that the entire structure is man-made, but instead, it can refer to the idea that certain functions or structures of biological cells can be modified, simplified, replaced or supplemented with a synthetic entity.

In other fields, the term "artificial cell" can refer to any compartment that somewhat resembles a biological cell in size or structure, but is synthetically made, or even fully made from non-biological components. The term "artificial cell" is also used for structures with direct applications such as compartments for drug delivery. Micro-encapsulation allows for metabolism within the membrane, exchange of small molecules and prevention of passage of large substances across it.[3][4] The main advantages of encapsulation include improved mimicry in the body, increased solubility of the cargo and decreased immune responses. Notably, artificial cells have been clinically successful in hemoperfusion.[5]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Artificial_cell

Artificial kidney is often a synonym for hemodialysis, but may also refer to the other renal replacement therapies (with exclusion of kidney transplantation) that are in use and/or in development. This article deals mainly with bioengineered kidneys/bioartificial kidneys that are grown from renal cell lines/renal tissue.

The first successful artificial kidney was developed by Willem Kolff in the Netherlands during the early 1940s: Kolff was the first to construct a working dialyzer in 1943.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Artificial_kidney

An induced coma – also known as a medically induced coma (MIC), barbiturate-induced coma, or drug-induced coma – is a temporary coma (a deep state of unconsciousness) brought on by a controlled dose of an anesthetic drug, often a barbiturate such as pentobarbital or thiopental. Other intravenous anesthetic drugs such as midazolam or propofol may be used.[1][2]

Drug-induced comas are used to protect the brain during major neurosurgery, as a last line of treatment in certain cases of status epilepticus that have not responded to other treatments,[2] and in refractory intracranial hypertension following traumatic brain injury.[1]

Induced coma usually results in significant systemic adverse effects. The patient is likely to completely lose respiratory drive and require mechanical ventilation; gut motility is reduced; hypotension can complicate efforts to maintain cerebral perfusion pressure and often requires the use of vasopressor drugs. Hypokalemia often results. The completely immobile patient is at increased risk of bed sores as well as infection from catheters.[citation needed]

Induced coma is a feature of the Milwaukee protocol, a controversial method that is promoted as a means of treating rabies infection in people.[3][4]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Induced_coma

Artificial constructs

Scientists have modified strains of viruses in order to study their behavior, as in the case of the H5N1 influenza virus. While funding for such research has aroused controversy at times due to safety concerns, leading to a temporary pause, it has subsequently proceeded.[5][6]

In biotechnology, microbial strains have been constructed to establish metabolic pathways suitable for treating a variety of applications.[7] Historically, a major effort of metabolic research has been devoted to the field of biofuel production.[8] Escherichia coli is most common species for prokaryotic strain engineering. Scientists have succeeded in establishing viable minimal genomes from which new strains can be developed.[9] These minimal strains provide a near guarantee that experiments on genes outside the minimal framework will not be effected by non-essential pathways. Optimized strains of E. coli are typically used for this application. E. coli are also often used as a chassis for the expression of simple proteins. These strains, such as BL21, are genetically modified to minimize protease activity, hence enabling potential for high efficiency industrial scale protein production.[10]

Strains of yeasts are the most common subjects of eukaryotic genetic modification, especially with respect to industrial fermentation.[11]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Strain_(biology)#Artificial_constructs

Artificial gene synthesis, or simply gene synthesis, refers to a group of methods that are used in synthetic biology to construct and assemble genes from nucleotides de novo. Unlike DNA synthesis in living cells, artificial gene synthesis does not require template DNA, allowing virtually any DNA sequence to be synthesized in the laboratory. It comprises two main steps, the first of which is solid-phase DNA synthesis, sometimes known as DNA printing.[1] This produces oligonucleotide fragments that are generally under 200 base pairs. The second step then involves connecting these oligonucleotide fragments using various DNA assembly methods. Because artificial gene synthesis does not require template DNA, it is theoretically possible to make a completely synthetic DNA molecule with no limits on the nucleotide sequence or size.

Synthesis of the first complete gene, a yeast tRNA, was demonstrated by Har Gobind Khorana and coworkers in 1972.[2] Synthesis of the first peptide- and protein-coding genes was performed in the laboratories of Herbert Boyer and Alexander Markham, respectively.[3][4] More recently, artificial gene synthesis methods have been developed that will allow the assembly of entire chromosomes and genomes. The first synthetic yeast chromosome was synthesised in 2014, and entire functional bacterial chromosomes have also been synthesised.[5] In addition, artificial gene synthesis could in the future make use of novel nucleobase pairs (unnatural base pairs).[6][7][8]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Artificial_gene_synthesis

Artificial life

The chemoton has laid the foundation of some aspects of artificial life. The computational basis has become a topic of software development and experimentation in the investigation of artificial life.[10] The main reason is that the chemoton simplifies the otherwise complex biochemical and molecular functions of living cells. Since the chemoton is a system consisting of a large but fixed number of interacting molecular species, it can effectively be implemented in a process algebra-based computer language.[11]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chemoton#Artificial_life

Hairy root culture, also called transformed root culture, is a type of plant tissue culture that is used to study plant metabolic processes or to produce valuable secondary metabolites or recombinant proteins, often with plant genetic engineering.[1]

A naturally occurring soil bacterium Agrobacterium rhizogenes that contains root-inducing plasmids (also called Ri plasmids) can infect plant roots and cause them to produce a food source for the bacterium, opines, and to grow abnormally.[2] The abnormal roots are particularly easy to culture in artificial media because hormones are not needed in contrast to adventitious roots,[2] and they are neoplastic, with indefinite growth. The neoplastic roots produced by A. rhizogenes infection have a high growth rate (compared to untransformed adventitious roots), as well as genetic and biochemical stability.

Currently the main constraint for commercial utilization of hairy root culture is the development and up-scaling of appropriate (bioreactors) vessels for the delicate and sensitive hairy roots.[2][3][4]

Some of the applied research on utilization of hairy root cultures has been and is conducted at VTT Technical Research Centre of Finland Ltd.[5][6] Other labs working on hairy roots are the phytotechnology lab of Amiens University and the Arkansas Biosciences Institute.

Metabolic studies

Hairy root cultures can be used for phytoremediation, and are particularly valuable for studies of the metabolic processes involved in phytoremediation.[2]

Further applications include detailed studies of fundamental molecular, genetic and biochemical aspects of genetic transformation and of hairy root induction.[7]

Genetically transformed cultures

The Ri plasmids can be engineered to also contain T-DNA, used for genetic transformation (biotransformation) of the plant cells. The resulting genetically transformed root cultures can produce high levels of secondary metabolites, comparable or even higher than those of intact plants.[8]

Use in plant propagation

Hairy root culture can also be used for regeneration of whole plants and for production of artificial seeds.[7]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (August 2010) |

See also

- Crown gall, a plant disease with similar uses caused by a related bacterium, Agrobacterium tumefaciens

References

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hairy_root_culture

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Urine_anion_gap

A powered exoskeleton, also known as power armor, powered armor, powered suit, cybernetic suit, cybernetic armor, exosuit, hardsuit, exoframe or augmented mobility,[1] is a mobile machine that is wearable over all or part of the human body, providing ergonomic structural support and powered by a system of electric motors, pneumatics, levers, hydraulics or a combination of cybernetic technologies, while allowing for sufficient limb movement with increased strength and endurance.[2] The exoskeleton is designed to provide better mechanical load tolerance, and its control system aims to sense and synchronize with the user's intended motion and relay the signal to motors which manage the gears. The exoskeleton also protects the user's shoulder, waist, back and thigh against overload, and stabilizes movements when lifting and holding heavy items.[3]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Powered_exoskeleton

Artificial cartilage is a synthetic material made of hydrogels[1] or polymers that aims to mimic the functional properties of natural cartilage in the human body. Tissue engineering principles are used in order to create a non-degradable and biocompatible material that can replace cartilage.[2] While creating a useful synthetic cartilage material, certain challenges need to be overcome. First, cartilage is an avascular structure in the body and therefore does not repair itself.[3] This creates issues in regeneration of the tissue. Synthetic cartilage also needs to be stably attached to its underlying surface, bone. Lastly, in the case of creating synthetic cartilage to be used in joint spaces, high mechanical strength under compression needs to be an intrinsic property of the material.[4]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Artificial_cartilage

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Artificial_ovary

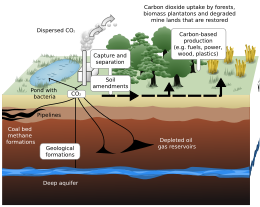

Carbon sequestration (or carbon storage) is the process of storing carbon (in particular atmospheric carbon dioxide) in a carbon pool.[2]: 2248 Carbon sequestration is a naturally occurring process but it can also be enhanced or achieved with technology, for example within carbon capture and storage projects. There are two main types of carbon sequestration: geologic and biologic (also called biosequestration).[3]

Carbon dioxide (CO

2) is naturally captured from the atmosphere through biological, chemical, and physical processes.[4]

These changes can be accelerated through changes in land use and

agricultural practices, such as converting crop land into land for

non-crop fast growing plants.[5] Artificial processes have been devised to produce similar effects,[4] including large-scale, artificial capture and sequestration of industrially produced CO

2 using subsurface saline aquifers or aging oil fields. Other technologies that work with carbon sequestration include bio-energy with carbon capture and storage, biochar, enhanced weathering, direct air carbon capture and sequestration (DACCS).

Forests, kelp beds, and other forms of plant life absorb carbon dioxide from the air as they grow, and bind it into biomass. However, these biological stores are considered volatile carbon sinks as the long-term sequestration cannot be guaranteed. For example, natural events, such as wildfires or disease, economic pressures and changing political priorities can result in the sequestered carbon being released back into the atmosphere.[6] Carbon dioxide that has been removed from the atmosphere can also be stored in the Earth's crust by injecting it into the subsurface, or in the form of insoluble carbonate salts (mineral sequestration). These methods are considered non-volatile because they remove carbon from the atmosphere and sequester it indefinitely and presumably for a considerable duration (thousands to millions of years).

To enhance carbon sequestration processes in oceans the following technologies have been proposed but none have achieved large scale application so far: Seaweed farming, ocean fertilisation, artificial upwelling, basalt storage, mineralization and deep sea sediments, adding bases to neutralize acids. The idea of direct deep-sea carbon dioxide injection has been abandoned.[7]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carbon_sequestration

Artificial insemination

Artificial insemination is a mechanism in which spermatozoa are deposited into the reproductive tract of a female.[8] Artificial insemination provides a number of benefits relating to reproduction in the poultry industry. Broiler breeds have been selected specifically for growth, causing them to develop large pectoral muscles, which interfere with and reduce natural mating.[9] The amount of sperm produced and deposited in the hen's reproductive tract may be limited because of this. Additionally, the males' overall sex drive may be significantly reduced due to growth selection.[10] Artificial insemination has allowed many farmers to incorporate selected genes into their stock, increasing their genetic quality.[11]

Abdominal massage is the most common method used for semen collection.[9] During this process, the rooster is restrained and the back region located towards the tail and behind the wings is caressed. This is done gently but quickly. Within a short period of time, the male should get an erection of the phallus. Once this occurs, the cloaca is squeezed and semen is collected from the external papilla of the vas deferens.[12]

During artificial insemination, semen is most frequently deposited intra-vaginally by means of a plastic syringe. In order for semen to be deposited here, the vaginal orifice is everted through the cloaca. This is simply done by applying pressure to the abdomen of the hen. The semen-containing instrument is placed 2–4 cm into the vaginal orifice. As the semen is being deposited, the pressure applied to the hen's abdomen is being released simultaneously.[9] The person performing this procedure typically uses one hand to move and direct the tail feathers, while using the other hand to insert the instrument and semen into the vagina.[12]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Broiler#Artificial_insemination

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Organ_(biology)

Sterilization may refer to:

- Sterilization (microbiology), killing or inactivation of micro-organisms

- Soil steam sterilization, a farming technique that sterilizes soil with steam in open fields or greenhouses

- Sterilization (medicine) renders a human unable to reproduce

- Neutering is the surgical sterilization of animals

- Irradiation induced sterility is used in the sterile insect technique

- A chemosterilant is a chemical compound that causes sterility

- Sterilization (economics), central bank operations aimed at neutralizing foreign exchange operations' impact on domestic money supply, or offset adverse consequences of large capital flows

See also

Soil steam sterilization (soil steaming) is a farming technique that sterilizes soil with steam in open fields or greenhouses. Pests of plant cultures such as weeds, bacteria, fungi and viruses are killed through induced hot steam which causes vital cellular proteins to unfold. Biologically, the method is considered a partial disinfection. Important heat-resistant, spore-forming bacteria can survive and revitalize the soil after cooling down. Soil fatigue can be cured through the release of nutritive substances blocked within the soil. Steaming leads to a better starting position, quicker growth and strengthened resistance against plant disease and pests. Today, the application of hot steam is considered the best and most effective way to disinfect sick soil, potting soil and compost. It is being used as an alternative to bromomethane, whose production and use was curtailed by the Montreal Protocol. "Steam effectively kills pathogens by heating the soil to levels that cause protein coagulation or enzyme inactivation."[1]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Soil_steam_sterilization

Apertium is a free/open-source rule-based machine translation platform. It is free software and released under the terms of the GNU General Public License.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Apertium

Fertilisation or fertilization (see spelling differences), also known as generative fertilisation, syngamy and impregnation,[1] is the fusion of gametes to give rise to a new individual organism or offspring and initiate its development.[2] While processes such as insemination or pollination which happen before the fusion of gametes are also sometimes informally referred to as fertilisation,[3] these are technically separate processes. The cycle of fertilisation and development of new individuals is called sexual reproduction. During double fertilisation in angiosperms the haploid male gamete combines with two haploid polar nuclei to form a triploid primary endosperm nucleus by the process of vegetative fertilisation.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fertilisation

Double fertilization is a complex fertilization mechanism of flowering plants (angiosperms). This process involves the joining of a female gametophyte (megagametophyte, also called the embryo sac) with two male gametes (sperm). It begins when a pollen grain adheres to the stigma of the carpel, the female reproductive structure of a flower. The pollen grain then takes in moisture and begins to germinate, forming a pollen tube that extends down toward the ovary through the style. The tip of the pollen tube then enters the ovary and penetrates through the micropyle opening in the ovule. The pollen tube proceeds to release the two sperm in the embryo sac.

The cells of an embryo sac of an unfertilized ovule are 8 in number and arranged in the form of 3+2+3 (from top to bottom) i.e. 3 antipodal cells, 2 polar central cells, 2 synergids & 1 egg cell. One sperm fertilizes the egg cell and the other sperm combines with the two polar nuclei of the large central cell of the megagametophyte. The haploid sperm and haploid egg combine to form a diploid zygote, the process being called syngamy, while the other sperm and the two haploid polar nuclei of the large central cell of the megagametophyte form a triploid nucleus (triple fusion). Some plants may form polyploid nuclei. The large cell of the gametophyte will then develop into the endosperm, a nutrient-rich tissue which provides nourishment to the developing embryo. The ovary, surrounding the ovules, develops into the fruit, which protects the seeds and may function to disperse them.[1]

The two central cell maternal nuclei (polar nuclei) that contribute to the endosperm, arise by mitosis from the same single meiotic product that gave rise to the egg. The maternal contribution to the genetic constitution of the triploid endosperm is double that of the sperm.

In a study conducted in 2008 of the plant Arabidopsis thaliana, the migration of male nuclei inside the female gamete, in fusion with the female nuclei, has been documented for the first time using in vivo imaging. Some of the genes involved in the migration and fusion process have also been determined.[2]

Evidence of double fertilization in Gnetales, which are non-flowering seed plants, has been reported.[3]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Double_fertilization

Internal fertilization is the union of an egg and sperm cell during sexual reproduction inside the female body. Internal fertilization, unlike its counterpart, external fertilization, brings more control to the female with reproduction.[1] For internal fertilization to happen there needs to be a method for the male to introduce the sperm into the female's reproductive tract.

Most taxa that reproduce by internal fertilization are gonochoric.[2]: 124–125 In mammals, reptiles, and certain other groups of animals, this is done by copulation, an intromittent organ being introduced into the vagina or cloaca.[3][4] In most birds, the cloacal kiss is used, the two animals pressing their cloacas together while transferring sperm.[5] Salamanders, spiders, some insects and some molluscs undertake internal fertilization by transferring a spermatophore, a bundle of sperm, from the male to the female. Following fertilization, the embryos are laid as eggs in oviparous organisms, or continue to develop inside the reproductive tract of the mother to be born later as live young in viviparous organisms.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Internal_fertilization

| In vitro fertilisation | |

|---|---|

This image shows intracytoplasmic sperm injection, the most commonly used IVF technique. | |

| Specialty | Reproductive Endocrinology & Infertility |

| ICD-10-PCS | 8E0ZXY1 |

In vitro fertilisation (IVF) is a process of fertilisation where an egg is combined with sperm in vitro ("in glass"). The process involves monitoring and stimulating a woman's ovulatory process, removing an ovum or ova (egg or eggs) from her ovaries and letting sperm fertilise them in a culture medium in a laboratory. After the fertilised egg (zygote) undergoes embryo culture for 2–6 days, it is transferred by catheter into the uterus, with the intention of establishing a successful pregnancy.

IVF is a type of assisted reproductive technology used for infertility treatment, gestational surrogacy, and, in combination with pre-implantation genetic testing, avoiding transmission of genetic conditions. A fertilised egg from a donor may implant into a surrogate's uterus, and the resulting child is genetically unrelated to the surrogate. Some countries have banned or otherwise regulate the availability of IVF treatment, giving rise to fertility tourism. Restrictions on the availability of IVF include costs and age, in order for a woman to carry a healthy pregnancy to term. Children born through IVF are colloquially called test tube babies.

In July 1978, Louise Brown was the first child successfully born after her mother received IVF treatment.[1] Brown was born as a result of natural-cycle IVF, where no stimulation was made. The procedure took place at Dr Kershaw's Cottage Hospital (now Dr Kershaw's Hospice) in Royton, Oldham, England. Robert G. Edwards was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 2010. The physiologist co-developed the treatment together with Patrick Steptoe and embryologist Jean Purdy but the latter two were not eligible for consideration as they had died and the Nobel Prize is not awarded posthumously.[2][3]

With egg donation and IVF, women who are past their reproductive years, have infertile partners, have idiopathic female-fertility issues, or have reached menopause can still become pregnant. After the IVF treatment, some couples get pregnant without any fertility treatments.[4] In 2018, it was estimated that eight million children had been born worldwide using IVF and other assisted reproduction techniques.[5] A 2019 study that explores 10 adjuncts with IVF (screening hysteroscopy, DHEA, testosterone, GH, aspirin, heparin, antioxidants in males and females, seminal plasma and PRP) suggests that until more evidence is done to show that these adjuncts are safe and effective, they should be avoided.[6]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/In_vitro_fertilisation

External fertilization is a mode of reproduction in which a male organism's sperm fertilizes a female organism's egg outside of the female's body.[1] It is contrasted with internal fertilization, in which sperm are introduced via insemination and then combine with an egg inside the body of a female organism.[2] External fertilization typically occurs in water or a moist area to facilitate the movement of sperm to the egg.[3] The release of eggs and sperm into the water is known as spawning.[4] In motile species, spawning females often travel to a suitable location to release their eggs.

However, sessile species are less able to move to spawning locations and must release gametes locally.[4] Among vertebrates, external fertilization is most common in amphibians and fish.[5] Invertebrates utilizing external fertilization are mostly benthic, sessile, or both, including animals such as coral, sea anemones, and tube-dwelling polychaetes.[3] Benthic marine plants also use external fertilization to reproduce.[3] Environmental factors and timing are key challenges to the success of external fertilization. While in the water, the male and female must both release gametes at similar times in order to fertilize the egg.[3] Gametes spawned into the water may also be washed away, eaten, or damaged by external factors.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/External_fertilization

Iron fertilization is the intentional introduction of iron to iron-poor areas of the ocean surface to stimulate phytoplankton production. This is intended to enhance biological productivity and/or accelerate carbon dioxide (CO2) sequestration from the atmosphere. Iron is a trace element necessary for photosynthesis in plants. It is highly insoluble in sea water and in a variety of locations is the limiting nutrient for phytoplankton growth. Large algal blooms can be created by supplying iron to iron-deficient ocean waters. These blooms can nourish other organisms.

Ocean iron fertilization is an example of a geoengineering technique.[1] Iron fertilization[2] attempts to encourage phytoplankton growth, which removes carbon from the atmosphere for at least a period of time.[3][4] This technique is controversial because there is limited understanding of its complete effects on the marine ecosystem,[5] including side effects and possibly large deviations from expected behavior. Such effects potentially include release of nitrogen oxides,[6] and disruption of the ocean's nutrient balance.[1] Controversy remains over the effectiveness of atmospheric CO

2 sequestration and ecological effects.[7]

Since 1990, 13 major large scale experiments have been carried out to

evaluate efficiency and possible consequences of the iron fertilization

in ocean waters. A study in 2017 determined that the method is unproven;

sequestering efficiency is low and sometimes no effect was seen and the

amount of iron deposits that is needed to make a small cut in the

carbon emissions is in the million tons per year.[8]

Approximately 25 per cent of the ocean surface has ample macronutrients, with little plant biomass (as defined by chlorophyll). The production in these high-nutrient low-chlorophyll (HNLC) waters is primarily limited by micronutrients, especially iron.[9] The cost of distributing iron over large ocean areas is large compared with the expected value of carbon credits.[10] Research in the early 2020s suggested that it could only permanently sequester a small amount of carbon.[11]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Iron_fertilization

Selfing" redirects here. For self-pollination specifically in flowering plants, see Self-pollination.

Autogamy, or self-fertilization, refers to the fusion of two gametes that come from one individual. Autogamy is predominantly observed in the form of self-pollination, a reproductive mechanism employed by many flowering plants. However, species of protists have also been observed using autogamy as a means of reproduction. Flowering plants engage in autogamy regularly, while the protists that engage in autogamy only do so in stressful environments.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Autogamy

Occurrence

Protists

Paramecium aurelia

Paramecium aurelia is the most commonly studied protozoan for autogamy. Similar to other unicellular organisms, Paramecium aurelia typically reproduce asexually via binary fission or sexually via cross-fertilization. However, studies have shown that when put under nutritional stress, Paramecium aurelia will undergo meiosis and subsequent fusion of gametic-like nuclei.[1] This process, defined as hemixis, a chromosomal rearrangement process, takes place in a number of steps. First, the two micronuclei of P. aurelia enlarge and divide two times to form eight nuclei. Some of these daughter nuclei will continue to divide to create potential future gametic nuclei. Of these potential gametic nuclei, one will divide two more times. Of the four daughter nuclei arising from this step, two of them become anlagen, or cells that will form part of the new organism. The other two daughter nuclei become the gametic micronuclei that will undergo autogamous self-fertilization.[2] These nuclear divisions are observed mainly when the P. aurelia is put under nutritional stress. Research shows that P. aurelia undergo autogamy synchronously with other individuals of the same species.

Clonal aging and rejuvenation

In Paramecium tetraurelia, vitality declines over the course of successive asexual cell divisions by binary fission. Clonal aging is associated with a dramatic increase in DNA damage.[3][4][5] When paramecia that have experienced clonal aging undergo meiosis, either during conjugation or automixis, the old macronucleus disintegrates and a new macronucleus is formed by replication of the micronuclear DNA that had just experienced meiosis followed by syngamy. These paramecia are rejuvenated in the sense of having a restored clonal lifespan. Thus it appears that clonal aging is due in large part to the progressive accumulation of DNA damage, and that rejuvenation is due to repair of DNA damage during meiosis that occurs in the micronucleus during conjugation or automixis and reestablishment of the macronucleus by replication of the newly repaired micronuclear DNA.

Tetrahymena rostrata

Similar to Paramecium aurelia, the parasitic ciliate Tetrahymena rostrata has also been shown to engage in meiosis, autogamy and development of new macronuclei when placed under nutritional stress.[6] Due to the degeneration and remodeling of genetic information that occurs in autogamy, genetic variability arises and possibly increases an offspring's chances of survival in stressful environments.

Allogromia laticollaris

Allogromia laticollaris is perhaps the best-studied foraminiferan amoeboid for autogamy. A. laticollaris can alternate between sexual reproduction via cross-fertilization and asexual reproduction via binary fission. The details of the life cycle of A. laticollaris are unknown, but similar to Paramecium aurelia, A. laticollaris is also shown to sometimes defer to autogamous behavior when placed in nutritional stress. As seen in Paramecium, there is some nuclear dimorphism observed in A. laticollaris. There are often observations of macronuclei and chromosomal fragments coexisting in A. laticollaris. This is indicative of nuclear and chromosomal degeneration, a process similar to the subdivisions observed in P. aurelia. Multiple generations of haploid A. laticollaris individuals can exist before autogamy actually takes place.[7] The autogamous behavior in A. laticollaris has the added consequence of giving rise to daughter cells that are substantially smaller than those rising from binary fission.[8] It is hypothesized that this is a survival mechanism employed when the cell is in stressful environments, and thus not able to allocate all resources to creating offspring. If a cell was under nutritional stress and not able to function regularly, there would be a strong possibility of its offspring's fitness being sub-par.

Self-pollination in flowering plants

About 10–15% of flowering plants are predominantly self-fertilizing.[9] Self-pollination is an example of autogamy that occurs in flowering plants. Self-pollination occurs when the sperm in the pollen from the stamen of a plant goes to the carpels of that same plant and fertilizes the egg cell present. Self-pollination can either be done completely autogamously or geitonogamously. In the former, the egg and sperm cells that unite come from the same flower. In the latter, the sperm and egg cells can come from a different flower on the same plant. While the latter method does blur the lines between autogamous self-fertilization and normal sexual reproduction, it is still considered autogamous self-fertilization.[10]

Self-pollination can lead to inbreeding depression due to expression of deleterious recessive mutations.[11] Meiosis followed by self-pollination results in little genetic variation, raising the question of how meiosis in self-pollinating plants is adaptively maintained over an extended period in preference to a less complicated and less costly asexual ameiotic process for producing progeny. For instance, Arabidopsis thaliana is a predominantly self-pollinating plant that has an outcrossing rate in the wild estimated at less than 0.3%,[12] and self-pollination appears to have evolved roughly a million years ago or more.[13] An adaptive benefit of meiosis that may explain its long-term maintenance in self-pollinating plants is efficient recombinational repair of DNA damage.[14]

Fungi

There are basically two distinct types of sexual reproduction among fungi. The first is outcrossing (in heterothallic fungi). In this case, mating occurs between two different haploid individuals to form a diploid zygote, that can then undergo meiosis. The second type is self-fertilization or selfing (in homothallic fungi). In this case, two haploid nuclei derived from the same individual fuse to form a zygote than can then undergo meiosis. Examples of homothallic fungi that undergo selfing include species with an aspergillus-like asexual stage (anamorphs) occurring in many different genera,[15] several species of the ascomycete genus Cochliobolus,[16] and the ascomycete Pneumocystis jirovecii[17] (for other examples, see Homothallism). A review of evidence on the evolution of sexual reproduction in the fungi led to the concept that the original mode of sexual reproduction in the last eukaryotic common ancestor was homothallic or self-fertile unisexual reproduction.[18]

Advantages of autogamy

There are several advantages for the self-fertilization observed in flowering plants and protists. In flowering plants, it is important for some plants not to be dependent on pollinating agents that other plants rely on for fertilization. This is unusual, however, considering that many plant species have evolved to become incompatible with their own gametes. While these species would not be well served by having autogamous self-fertilization as a reproductive mechanism, other species, which do not have self-incompatibility, would benefit from autogamy. Protists have the advantage of diversifying their modes of reproduction. This is useful for a multitude of reasons. First, if there is an unfavorable change in the environment that puts the ability to deliver offspring at risk, then it is advantageous for an organism to have autogamy at its disposal. In other organisms, it is seen that genetic diversity arising from sexual reproduction is maintained by changes in the environment that favor certain genotypes over others. Aside from extreme circumstances, it is possible that this form of reproduction gives rise to a genotype in the offspring that will increase fitness in the environment. This is due to the nature of the genetic degeneration and remodeling intrinsic to autogamy in unicellular organisms. Thus, autogamous behavior may become advantageous to have if an individual wanted to ensure offspring viability and survival. This advantage also applies to flowering plants. However, it is important to note that this change has not shown to produce a progeny with more fitness in unicellular organisms.[19] It is possible that the nutrition deprived state of the parent cells before autogamy created a barrier for producing offspring that could thrive in those same stressful environments.

Disadvantages of autogamy

In flowering plants, autogamy has the disadvantage of producing low genetic diversity in the species that use it as the predominant mode of reproduction. This leaves those species particularly susceptible to pathogens and viruses that can harm it. In addition, the foraminiferans that use autogamy have shown to produce substantially smaller progeny as a result.[20] This indicates that since it is generally an emergency survival mechanism for unicellular species, the mechanism does not have the nutritional resources that would be provided by the organism if it were undergoing binary fission.

Genetic consequences of self-fertilization

Self-fertilization results in the loss of genetic variation within an individual (offspring), because many of the genetic loci that were heterozygous become homozygous. This can result in the expression of harmful recessive alleles, which can have serious consequences for the individual. The effects are most extreme when self-fertilization occurs in organisms that are usually out-crossing.[21] In plants, selfing can occur as autogamous or geitonogamous pollinations and can have varying fitness affects that show up as autogamy depression. After several generations, inbreeding depression is likely to purge the deleterious alleles from the population because the individuals carrying them have mostly died or failed to reproduce.

If no other effects interfere, the proportion of heterozygous loci is halved in each successive generation, as shown in the following table.

- Parental : x (100%), and in

- 1 generation gives: : : , which means that the frequency of heterozygotes now is 50% of the starting value.

- By the 10 generation, heterozygotes have almost completely disappeared, and the population is polarized, with almost exclusively homozygous individuals ( and )

Illustration model of the decrease in genetic variation in a population of self-fertilized organisms derived from a heterozygous individual, assuming equal fitness

| Generation | AA (%) |

Aa (%) |

aa (%) |

| P | – | 100 | – |

| F1 | 25 | 50 | 25 |

| F2 | 37.5 | 25 | 37.5 |

| F3 | 43.75 | 12.5 | 43.75 |

| F4 | 46.875 | 6.25 | 46.875 |

| F5 | 48.4375 | 3.125 | 48.4375 |

| F6 | 49.21875 | 1.5625 | 49.21875 |

| F7 | 49.609375 | 0.78125 | 49.609375 |

| F8 | 49.8046875 | 0.390625 | 49.8046875 |

| F9 | 49.90234375 | 0.1953125 | 49.90234375 |

| F10 | 49.995117187 ≈ 50.0 | 0.09765626 ≈ 0.0 | 49.995117187 ≈ 50.0 |

Evolution of autogamy

The evolutionary shift from outcrossing to self-fertilization is one of the most frequent evolutionary transitions in plants. Since autogamy in flowering plants and autogamy in unicellular species is fundamentally different, and plants and protists are not related, it is likely that both instances evolved separately. However, due to the little overall genetic variation that arises in progeny, it is not fully understood how autogamy has been maintained in the tree of life.

See also

- Effective selfing model

- Parthenogenesis

- Inbreeding

- Outcrossing

- Inbreeding depression

- Outbreeding depression

- Sequential hermaphroditism; the organism spends part of its life as a female and part as a male; self-fertilization is not possible.

References

- Bernstein H, Byerly HC, Hopf FA, Michod RE (September 1985). "Genetic damage, mutation, and the evolution of sex". Science. 229 (4719): 1277–81. Bibcode:1985Sci...229.1277B. doi:10.1126/science.3898363. PMID 3898363.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Autogamy

Reconstructive surgery is surgery performed to restore normal appearance and function to body parts malformed by a disease or medical condition.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reconstructive_surgery

The Reconstruction era was a period in American history following the American Civil War (1861–1865) and lasting until approximately the Compromise of 1877. During Reconstruction, attempts were made to rebuild the country after the bloody Civil War, bring the former Confederate states back into the United States, and to counteract the political, social, and economic legacies of slavery.

During the era, Congress abolished slavery, ended the remnants of Confederate secession in the South, and passed the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments to the Constitution (the Reconstruction Amendments) ostensibly guaranteeing the newly freed slaves (freedmen) the same civil rights as those of whites. Following a year of violent attacks against Blacks in the South, in 1866 Congress federalized the protection of civil rights, and placed formerly secessionist states under the control of the U.S. military, requiring ex-Confederate states to adopt guarantees for the civil rights of freedmen before they could be readmitted to the Union. In nearly all ex-Confederate states, Republican coalitions set out to transform Southern society. The Freedmen's Bureau and the U.S. Army both aimed to implement a post-slavery free labor economy, protect the legal rights of freedmen, negotiate labor contracts, and helped establish networks of schools and churches. Thousands of Northerners ("Carpetbaggers") came to the South to serve in the social and economic programs of Reconstruction. White Southerners who supported Reconstruction policies and efforts were known as "Scalawags".

Fighting against suffrage and full rights for freedmen, and in favor of giving the returning Southern states relatively free rein over former slaves, were the white "Redeemers"; Southern Bourbon Democrats;[2] Vice President Andrew Johnson, a Southerner who assumed the presidency after the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln; and especially the Ku Klux Klan, which intimidated, terrorized, and murdered freedmen and Republicans, including Arkansas Congressman James M. Hinds, throughout the former Confederacy.

Republican President Ulysses S. Grant (1869–1877) succeeded Johnson and supported congressional Reconstruction and the protection of African Americans in the South, but eventually support for Reconstruction declined in the North with "Liberal Republicans" joining Democrats in calling for a withdrawal of the Army from the South. In 1877, as part of a congressional compromise to elect a Republican as president after a disputed election, federal troops were withdrawn from the three Southern states where they remained.

Among the many "shortcomings and failures" of Reconstruction were the failure to protect freed blacks from Ku Klux Klan violence prior to 1871, starvation, disease and death, brutal treatment of Union soldiers, and the offering of reparations to former slaveowners but not to former slaves.[3] However, Reconstruction did succeed in restoring the federal Union, limiting reprisals against the South directly after the war, establishing the constitutional rights to national birthright citizenship, due process, equal protection of the laws, and male suffrage regardless of race, and a framework for eventual legal equality for black people.[4]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reconstruction_era

Reconstructive memory is a theory of memory recall, in which the act of remembering is influenced by various other cognitive processes including perception, imagination, motivation, semantic memory and beliefs, amongst others. People view their memories as being a coherent and truthful account of episodic memory and believe that their perspective is free from an error during recall. However, the reconstructive process of memory recall is subject to distortion by other intervening cognitive functions such as individual perceptions, social influences, and world knowledge, all of which can lead to errors during reconstruction.

Reconstructive process

Memory rarely relies on a literal recount of past experiences. By using multiple interdependent cognitive processes, there is never a single location in the brain where a given complete memory trace of experience is stored.[1] Rather, memory is dependent on constructive processes during encoding that may introduce errors or distortions. Essentially, the constructive memory process functions by encoding the patterns of perceived physical characteristics, as well as the interpretive conceptual and semantic functions that act in response to the incoming information.[2]

In this manner, the various features of the experience must be joined together to form a coherent representation of the episode.[3] If this binding process fails, it can result in memory errors. The complexity required for reconstructing some episodes is quite demanding and can result in incorrect or incomplete recall.[4] This complexity leaves individuals susceptible to phenomena such as the misinformation effect across subsequent recollections.[5] By employing reconstructive processes, individuals supplement other aspects of available personal knowledge and schema into the gaps found in episodic memory in order to provide a fuller and more coherent version, albeit one that is often distorted.[6]

Many errors can occur when attempting to retrieve a specific episode. First, the retrieval cues used to initiate the search for a specific episode may be too similar to other experiential memories and the retrieval process may fail if the individual is unable to form a specific description of the unique characteristics of the given memory they would like to retrieve.[7] When there is little available distinctive information for a given episode there will be more overlap across multiple episodes, leading the individual to recall only the general similarities common to these memories. Ultimately proper recall for a desired target memory fails due to the interference of non-target memories that are activated because of their similarity.[3]

Secondly, a large number of errors that occur during memory reconstruction are caused by faults in the criterion-setting and decision making processes used to direct attention towards retrieving a specific target memory. When there are lapses in the recall of aspects of episodic memory, the individual tends to supplement other aspects of knowledge that are unrelated to the actual episode to form a more cohesive and well-rounded reconstruction of the memory, regardless of whether or not the individual is aware of such supplemental processing. This process is known as confabulation. All of the supplemental processes occurring during the course of reconstruction rely on the use of schema, information networks that organize and store abstract knowledge in the brain.

Characteristics

Schema

Schema are generally defined as mental information networks that represent some aspect of collected world knowledge. Frederic Bartlett was one of the first psychologists to propose Schematic theory, suggesting that the individual's understanding of the world is influenced by elaborate neural networks that organize abstract information and concepts.[8] Schema are fairly consistent and become strongly internalized in the individual through socialization, which in turn alters the recall of episodic memory. Schema is understood to be central to reconstruction, used to confabulate, and fill in gaps to provide a plausible narrative. Bartlett also showed that schema can be tied to cultural and social norms.[9]

Jean Piaget's theory of schema

Piaget's theory proposed an alternative understanding of schema based on the two concepts: assimilation and accommodation. Piaget defined assimilation as the process of making sense of the novel and unfamiliar information by using previously learned information. To assimilate, Piaget defined a second cognitive process that served to integrate new information into memory by altering preexisting schematic networks to fit novel concepts, what he referred to as accommodation.[10] For Piaget, these two processes, accommodation, and assimilation, are mutually reliant on one another and are vital requirements for people to form basic conceptual networks around world knowledge and to add onto these structures by utilizing preexisting learning to understand new information, respectively.

According to Piaget, schematic knowledge organizes features information in such a way that more similar features are grouped so that when activated during recall the more strongly related aspects of memory will be more likely to activate together. An extension of this theory, Piaget proposed that the schematic frameworks that are more frequently activated will become more strongly consolidated and thus quicker and more efficient to activate later.[11]

Frederic Bartlett's experiments

Frederic Bartlett originally tested his idea of the reconstructive nature of recall by presenting a group of participants with foreign folk tales (his most famous being "War of the Ghosts"[12]) with which they had no previous experience. After presenting the story, he tested their ability to recall and summarize the stories at various points after the presentation to newer generations of participants. His findings showed that the participants could provide a simple summary but had difficulty recalling the story accurately, with the participants' own account generally being shorter and manipulated in such a way that aspects of the original story that were unfamiliar or conflicting to the participants' own schematic knowledge were removed or altered in a way to fit into more personally relevant versions.[8] For instance, allusions made to magic and Native American mysticism that were in the original version were omitted as they failed to fit into the average Westerner schematic network. Besides, after several recounts of the story had been made by successive generations of participants, certain aspects of the recalled tale were embellished so they were more consistent with the participants' cultural and historical viewpoint compared to the original text (e.g. Emphasis placed on one of the characters desire to return to care for his dependent elderly mother). These findings lead Bartlett to conclude that recall is predominately a reconstructive rather than reproductive process.[9]

James J. Gibson built off of the work that Bartlett originally laid down, suggesting that the degree of change found in a reproduction of an episodic memory depends on how that memory is later perceived.[13] This concept was later tested by Carmichael, Hogan, and Walter (1932) who exposed a group of participants to a series of simple figures and provided different words to describe each images. For example, all participants were exposed to an image of two circles attached by a single line, where some of the participants were told it was a barbell and the rest were told it was a pair of reading glasses. The experiment revealed that when the participants were later tasked with replicating the images, they tended to add features to their own reproduction that more closely resembled the word they were primed with.

Confirmation bias

During retrieval of episodic memories, people use their schematic knowledge to fill in information gaps, though they generally do so in a manner that implements aspects of their own beliefs, moral values, and personal perspective that leads the reproduced memory to be a biased interpretation of the original version. Confirmation bias results in overconfidence in personal perception and usually leads to a strengthening of beliefs, often in the face of contradictory dis-confirming evidence.[14]

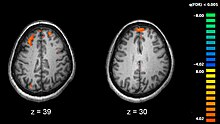

Associated neural activity

Recent research using neuro-imaging technology including PET and fMRI scanning has shown that there is an extensive amount of distributed brain activation during the process of episodic encoding and retrieval. Among the various regions, the two most active areas during the constructive processes are the medial temporal lobe (including the hippocampus) and the prefrontal cortex.[15] The Medial Temporal lobe is especially vital for encoding novel events in episodic networks, with the Hippocampus acting as one of the central locations that acts to both combine and later separate the various features of an event.[16][17] Most popular research holds that the Hippocampus becomes less important in long term memory functioning after more extensive consolidation of the distinct features present at the time of episode encoding has occurred. In this way long term episodic functioning moves away from the CA3 region of the Hippocampal formation into the neocortex, effectively freeing up the CA3 area for more initial processing.[17] Studies have also consistently linked the activity of the Prefrontal Cortex, especially that which occurs in the right hemisphere, to the process of retrieval.[18] The Prefrontal cortex appears to be utilized for executive functioning primarily for directing the focus of attention during retrieval processing, as well as for setting the appropriate criterion required to find the desired target memory.[15]

Applications

Eyewitness testimony

Eyewitness testimony is a commonly recurring topic in the discussion of reconstructive memory and its accuracy is the subject of many studies. Eyewitness testimony is any firsthand accounts given by individuals of an event they have witnessed. Eyewitness testimony is used to acquire details about the event and even to identify the perpetrators of the event.[19] Eyewitness testimony is used often in court and is viewed favorably by juries as a reliable source of information.[19] Unfortunately, eyewitness testimony can be easily manipulated by a variety of factors such as:

- Anxiety and stress

- Schema

- The cross-race effect

Anxiety and stress

Anxiety is a state of distress or uneasiness of mind caused by fear[20] and it is a consistently associated with witnessing crimes. In a study done by Yuille and Cutshall (1986), they discovered that witnesses of real-life violent crimes were able to remember the event quite vividly even five months after it originally occurred.[19] In fact, witnesses to violent or traumatic crimes often self-report the memory as being particularly vivid. For this reason, eyewitness memory is often listed as an example of flashbulb memory.

However, in a study by Clifford and Scott (1978), participants were shown either a film of a violent crime or a film of a non-violent crime. The participants who viewed the stressful film had difficulty remembering details about the event compared to the participants that watched the non-violent film.[19] In a study by Brigham et al. (2010), subjects who experienced an electrical shock were less accurate in facial recognition tests, suggesting that some details were not well remembered under stressful situations.[21] In fact, in the case of the phenomena known as weapon focus, eyewitnesses to stressful crimes involving weapons may perform worse during suspect identification.[22]

Further studies on flashbulb memories seem to indicate that witnesses may recall vivid sensory content unrelated to the actual event but which enhance its perceived vividness.[23] Due to this vividness, eyewitnesses may place higher confidence in their reconstructed memories.[24]

Application of schema

The use of schemas has been shown to increase the accuracy of recall of schema-consistent information but this comes at the cost of decreased recall of schema-inconsistent information. A study by Tuckey and Brewer[25] found that after 12 weeks, memories of information inconsistent with a schema-typical robbery decays much faster than those that are schema-consistent. These were memories such as the method of getaway, demands by the robbers, and the robbers' physical appearance. The study also found that information that was schema-inconsistent but stood out as very abnormal for the participants was usually recalled more readily and was retained for the duration of the study. The authors of the study advise that interviewers of eyewitnesses should take note of such reports because there is a possibility that they may be accurate.

Cross-race effect

Reconstructing the face of another race requires the use of schemas that may not be as developed and refined as those of the same race.[26] The cross-race effect is the tendency that people have to distinguish among other of their race than of other races. Although the exact cause of the effect is unknown, two main theories are supported. The perceptual expertise hypothesis postulates that because most people are raised and are more likely to associate with others of the same race, they develop an expertise in identifying the faces of that race. The other main theory is the in-group advantage. It has been shown in the lab that people are better at discriminating the emotions of in-group members than those of out-groups.[27]

Leading questions

Often during eyewitness testimonies, the witness is interrogated about their particular view of an incident and often the interrogator will use leading questions to direct and control the type of response that is elicited by the witness.[28] This phenomenon occurs when the response a person gives can be persuaded by the way a question is worded. For example, a person could be posed a question in two different forms:

- "What was the approximate height of the robber?" which would lead the respondent to estimate the height according to their original perceptions. They could alternatively be asked:

- "How short was the robber?" which would persuade the respondent to recall that the robber was actually shorter than they had originally perceived.

Using this method of controlled interrogation, the direction of a witness cross-examination can often be controlled and manipulated by the individual who is posing questions to fit their own needs and intentions.

Retrieval cues

After the information is encoded and stored in our memory, specific cues are often needed to retrieve these memories. These are known as retrieval cues[citation needed] and they play a major role in reconstructive memory. The use of retrieval cues can both promote the accuracy of reconstructive memory as well as detract from it. The most common aspect of retrieval cues associated with reconstructive memory is the process that involves recollection. This process uses logical structures, partial memories, narratives, or clues to retrieve the desired memory.[29] However, the process of recollection is not always successful due to cue-dependent forgetting and priming.

Cue-dependent forgetting

Cue-dependent forgetting (also known as retrieval failure) occurs when memories are not obtainable because the appropriate cues are absent.[30] This is associated with a relatively common occurrence known as the tip of the tongue (TOT) phenomenon, originally developed by the psychologist William James. Tip of the tongue phenomenon refers to when an individual knows particular information, and they are aware that they know this information, yet can not produce it even though they may know certain aspects about the information.[31] For example, during an exam a student is asked who theorized the concept of Psychosexual Development, the student may be able to recall the details about the actual theory but they are unable to retrieve the memory associated with who originally introduced the theory.

Priming

Priming refers to an increased sensitivity to certain stimuli due to prior experience.[32] Priming is believed to occur outside of conscious awareness, which makes it different from memory that relies on the direct retrieval of information.[33] Priming can influence reconstructive memory because it can interfere with retrieval cues. Psychologist Elizabeth Loftus presented many papers concerning the effects of proactive interference on the recall of eyewitness events. Interference involving priming was established in her classic study with John Palmer in 1974.[34] Loftus and Palmer recruited 150 participants and showed each of them a film of a traffic accident. After, they had the participants fill out a questionnaire concerning the video's details. The participants were split into three groups:

- Group A contained 50 participants that were asked: "About how fast were the cars going when they hit each other?”

- Group B contained 50 participants that were asked: "About how fast were the cars going when they smashed each other?"

- Group C contained 50 participants and were not asked this question because they were meant to represent a control group

A week later, all of the participants were asked whether or not there had been any broken glass in the video. A statistically significant number of participants in the group B answered that they remembered seeing broken glass in the video (p < -.05). However, there was not any broken glass in the video. The difference between this group and the others was that they were primed with the word “smashed” in the questionnaire, one week before answering the question. By changing one word in the questionnaire, their memories were re-encoded with new details.[35]

Reconstructive errors

Confabulation

Confabulation is the involuntary false remembering of events and can be a characteristic of several psychological diseases such as Korsakoff's syndrome, Alzheimer's disease, schizophrenia and traumatic injury of certain brain structures.[36] Those confabulating don't know that what they are remembering is false and have no intent to deceive.[37]

In the regular process of reconstruction, several sources are used to accrue information and add detail to memory. For patients producing confabulations, some key sources of information are missing and so other sources are used to produce a cohesive, internally consistent, and often believable false memory.[38] The source and type of confabulations differ for each type of disease or area of traumatic damage.

Selective memory

Selective memory involves actively forgetting negative experiences or enhancing positive ones.[39] This process actively affects reconstructive memory by distorting recollections of events. This affects reconstructive memories in two ways:

- by preventing memories from being recalled, even when appropriate cues are present

- by enhancing one's own role in previous experiences, also known as motivated self-enhancement

Many autobiographies are excellent examples of motivated self-enhancement because when recalling the events that have taken place in one's life, there is a tendency to make oneself appear to be more involved in positive experiences, though others may remember the event differently.

See also

References

- Waulhauser, G. (2011, July 11). Selective memory does exist. The Telegraph.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reconstructive_memory

A belief is a subjective attitude that a proposition is true or a state of affairs is the case. A subjective attitude is a mental state of having some stance, take, or opinion about something.[1] In epistemology, philosophers use the term "belief" to refer to attitudes about the world which can be either true or false.[2] To believe something is to take it to be true; for instance, to believe that snow is white is comparable to accepting the truth of the proposition "snow is white". However, holding a belief does not require active introspection. For example, few carefully consider whether or not the sun will rise tomorrow, simply assuming that it will. Moreover, beliefs need not be occurrent (e.g. a person actively thinking "snow is white"), but can instead be dispositional (e.g. a person who if asked about the color of snow would assert "snow is white").[2]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Belief

Compulsory sterilization, also known as forced or coerced sterilization, is a government-mandated program to involuntarily sterilize a specific group of people. Sterilization removes a person's capacity to reproduce, and is usually done through surgical procedures. Several countries implemented sterilization programs in the early 20th century.[1] Although such programs have been made illegal in most countries of the world, instances of forced or coerced sterilizations persist.

Rationalizations for compulsory sterilization have included eugenics, population control, gender discrimination, limiting the spread of HIV,[2] "gender-normalizing" surgeries for intersex people, and ethnic genocide. In some countries, transgender individuals are required to undergo sterilization before gaining legal recognition of their gender, a practice that the United Nations Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment has described as a violation of the Yogyakarta Principles.[3]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Compulsory_sterilization

Sterilization law is the area of law, within reproductive rights, that gives a person the right to choose or refuse reproductive sterilization and governs when the government may limit this fundamental right. Sterilization law includes federal and state constitutional law, statutory law, administrative law, and common law. This article primarily focuses on laws concerning compulsory sterilization that have not been repealed or abrogated and are still good laws, in whole or in part, in each jurisdiction.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sterilization_law_in_the_United_States