| Part of the Politics series |

| Democracy |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Part of the Politics series |

| Basic forms of government |

|---|

| List of forms of government |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

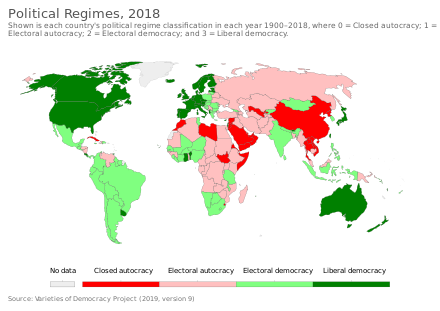

Types of democracy refers to pluralism of governing structures such as governments (local through to global) and other constructs like workplaces, families, community associations, and so forth. Types of democracy can cluster around values. For example, some like direct democracy, electronic democracy, participatory democracy, real democracy, and deliberative democracy, strive to allow people to participate equally and directly in protest, discussion, decision-making, or other acts of politics. Different types of democracy - like representative democracy - strive for indirect participation as this procedural approach to collective self-governance is still widely considered the only means for the more or less stable democratic functioning of mass societies.[1] Types of democracy can be found across time, space, and language.[2] In the English language the noun "democracy" has been modified by 2,234 adjectives.[3] These adjectival pairings, like atomic democracy or Zulu democracy, act as signal words that point not only to specific meanings of democracy but to groups, or families, of meaning as well.

Direct democracy

A direct democracy, or pure democracy, is a type of democracy where the people govern directly. It requires wide participation of citizens in politics.[4] Athenian democracy, or classical democracy, refers to a direct democracy developed in ancient times in the Greek city-state of Athens. A popular democracy is a type of direct democracy based on referendums and other devices of empowerment and concretization of popular will.

An industrial democracy is an arrangement which involves workers making decisions, sharing responsibility and authority in the workplace (see also workplace).

Representative democracies

A representative democracy is an indirect democracy where sovereignty is held by the people's representatives.

- A liberal democracy is a representative democracy with protection for individual liberty and property by rule of law.

- An illiberal democracy has weak or no limits on the power of the elected representatives to rule as they please.

Types of representative democracy include:

- Electoral democracy – type of representative democracy based on election, on electoral vote, as modern occidental or liberal democracies. Also, electoral democracy can guaranteed to protect personal freedoms.[5]

- Dominant-party system – democratic party system where only one political party can realistically become the government, by itself or in a coalition government.

- Parliamentary democracy

– democratic system of government where the executive branch of a

parliamentary government is typically a cabinet, and headed by a prime

minister who is considered the head of government.

- Westminster democracy – parliamentary system of government modeled after that of the United Kingdom system.

- Presidential democracy

– democratic system of government where a head of government is also

head of state and leads an executive branch that is separate from the

legislative branch.

- Jacksonian democracy – a variant of presidential democracy popularized by U.S. President Andrew Jackson which promoted the strength of the executive branch and the Presidency at the expense of Congressional power.

A demarchy has people randomly selected from the citizenry through sortition to either act as general governmental representatives or to make decisions in specific areas of governance (defense, environment, etc.).

A non-partisan democracy is system of representative government or organization such that universal and periodic elections (by secret ballot) take place without reference to political parties.

An organic or authoritarian democracy is a democracy where the ruler holds a considerable amount of power, but their rule benefits the people. The term was first used by supporters of Bonapartism.[6]

Types based on location

A cellular democracy, developed by Georgist libertarian economist Fred E. Foldvary, uses a multi-level bottom-up structure based on either small neighborhood governmental districts or contractual communities.[7]

A workplace democracy refers to the application of democracy to the workplace[8] (see also industrial democracy).

Types based on level of freedom

A liberal democracy is a representative democracy with protection for individual liberty and property by rule of law. In contrast, a defensive democracy limits some rights and freedoms in order to protect the institutions of the democracy.

Types based on ethnic influence

Religious democracies

A religious democracy is a form of government where the values of a particular religion have an effect on the laws and rules, often when most of the population is a member of the religion, such as:

Other types of democracy

Types of democracy include:

- Autocratic Democracy: where the party elected ruler will control unilaterally the state.

- Anticipatory democracy – relies on some degree of disciplined and usually market-informed anticipation of the future, to guide major decisions.

- Associationalism, or Associative Democracy – emphasis on freedom via voluntary and democratically self-governing associations.

- Adversialism, or Adversial Democracy – with an emphasis on freedom based on adversial relationships between individuals and groups as best expressed in democratic judicial systems.

- Bourgeois democracy – some Marxists, communists, socialists and anarchists refer to liberal democracy as bourgeois democracy, alleging that ultimately politicians fight only for the rights of the bourgeoisie.

- Consensus democracy – rule based on consensus rather than traditional majority rule.

- Constitutional democracy – governed by a constitution.

- Deliberative democracy – in which authentic deliberation, not only voting, is central to legitimate decision making. It adopts elements of both consensus decision-making and majority rule.

- Democratic centralism – an organizational method where members of a political party discuss and debate matters of policy and direction and after the decision is made by majority vote, all members are expected to follow that decision in public.

- Democratic dictatorship (also known as democratur)

- Democratic republic – republic which has democracy through elected representatives

- Democratic socialism – form of socialism ideologically opposed to the Marxist–Leninist styles that have become synonymous with socialism; democratic socialists place an emphasis on decentralized governance in political democracy with social ownership of the means of production and social and economic institutions with workers' self-management.

- Economic democracy – theory of democracy involving people having access to subsistence, or equity in living standards.

- Grassroots democracy – emphasizes trust in small decentralized units at the municipal government level, possibly using urban secession to establish the formal legal authority to make decisions made at this local level binding.

- Guided democracy – a form of democratic government with increased autocracy where citizens exercise their political rights without meaningfully affecting the government's policies, motives, and goals.

- Inclusive democracy – a left-libertarian formulation of democracy that includes democracy in the social, political, economic, and ecological spheres; primarily due to Greek philosopher Takis Fotopoulos.

- Interactive democracy – a proposed form of democracy utilising information technology to allow citizens to propose new policies, "second" proposals and vote on the resulting laws (that are refined by Parliament) in a referendum.

- Jeffersonian democracy – named after American statesman Thomas Jefferson, who believed in equality of political opportunity and opposed to privilege, aristocracy and corruption.

- Liquid democracy – a form of democratic control whereby voting power is vested in individual citizens who may self-select provisional delegates, rather than elected representatives.

- Market democracy – another name for democratic capitalism, an economic ideology based on a tripartite arrangement of a market-based economy based predominantly on economic incentives through free markets, a democratic polity and a liberal moral-cultural system which encourages pluralism.

- Multiparty democracy – an electoral democracy where the people have free and fair elections and can choose between multiple political parties, unlike dictatorships that have usually one party that dominates the other parties or it is the only legally allowed party to rule.

- New Democracy – Maoist concept based on Mao Zedong's "Bloc of Four Classes" theory in post-revolutionary China.

- Participatory democracy – involves more lay citizen participation in decision making and offers greater political representation than traditional representative democracy, e.g., wider control of proxies given to representatives by those who get directly involved and actually participate.

- People's democracy – multi-class rule in which the proletariat dominates.

- Radical democracy – type of democracy that focuses on the importance of nurturing and tolerating difference and dissent in decision-making processes.

- Revolutionary democracy – ideology of the Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Democratic Front

- Semi-direct democracy – representative democracy with instruments, elements, and/or features of direct democracy.

- Sociocracy – a democratic system of governance based on consent decision making, circle organization, subsidiarity, and double-linked representation.

See also

- Global Foundation for Democracy and Development (GFDD)

- Fundación Global Democracia y Desarrollo (FUNGLODE)

- Communalism

- Corsican Constitution

- Democracy Index

- Democracy promotion

- Democracy Ranking

- Democratic capitalism

- Direct Action and Democracy Today

- Education Index

- The End of History and the Last Man

- Four boxes of liberty

- Holacracy

- International Centre for Democratic Transition

- Islam and democracy

- Isonomia

- Jewish and Democratic State

- Kleroterion

- List of wars between democracies

- Motion (democracy)

- National Democratic Institute for International Affairs

- United Front for Democracy Against Dictatorship

- Netherlands Institute for Multiparty Democracy

- Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights

- Penn, Schoen & Berland

- Polity data series

- Post-democracy

- Potsdam Declaration

- Public sphere

- Ratification

- Synoecism

- Trustee model of representation

- Vox populi

- Why Democracy?

- Workplace democracy

- World Bank's Inspection Panel

- World Forum for Democratization in Asia

- World Youth Movement for Democracy

- Constitutional economics

- Cosmopolitan democracy

- Community of Democracies

- Democracy Index

- Democracy promotion

- Democratic Peace Theory

- Democratization

- Direct Action and Democracy Today

- Empowered democracy

- Foucault/Habermas debate

- Freedom deficit

- Liberal democracy

- List of direct democracy parties

- Majority rule

- Media democracy

- Netocracy

- Poll

- Panarchy

- Polyarchy

- Sociocracy

- Sortition

- Subversion

- Rule According to Higher Law

- Voting

Further types

Bibliography

- Living Database of Democracy with Adjectives Gagnon, Jean-Paul. 2020. "Democracy with Adjectives Database, at 3539 entries". Latest entry April 8. Provided by the Foundation for the Philosophy of Democracy and the University of Canberra. Hosted by Cloudstor / Aarnet / Instaclustr.

- Appendix A: Types of Democracies M. Haas, Why Democracies Flounder and Fail, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-74070-6, June 2018

References

- Rayasam, Renuka (24 April 2008). "Why Workplace Democracy Can Be Good Business". U.S. News & World Report. Archived from the original on 12 July 2012. Retrieved 16 August 2010.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Types_of_democracy

Breeding back is a form of artificial selection by the deliberate selective breeding of domestic (but not exclusively) animals, in an attempt to achieve an animal breed with a phenotype that resembles a wild type ancestor, usually one that has gone extinct. Breeding back is not to be confused with dedomestication.

It must be kept in mind that a breeding-back breed may be very similar to the extinct wild type in phenotype, ecological niche, and to some extent genetics, but the gene pool of that wild type was different prior to its extinction. Even the superficial authenticity of a bred-back animal depends on the particular stock used to breed the new lineage. As a result of this, some breeds, like Heck cattle, are at best a vague look-alike of the extinct wild type aurochs, according to the literature.[1]

Background

The aim of breeding back programs is to restore the wild traits which may have been unintentionally preserved in the lineages of domesticated animals. Commonly, not only the new animal's phenotype, but also its ecological capacity, are considered in back-breeding projects, as hardy, "bred back" animals may be used in certain conservation projects. In nature, usually only individuals well suited to their natural circumstances will survive and reproduce, whereas humans select animals with additional attractive, docile or productive characteristics, protecting them from the dangers once found in their ancestral environment (predation, drought, disease, extremes of weather, lack of mating opportunities, etc.). In such cases, selection criteria in nature differ from those found in domesticated conditions. Because of this, domesticated animals often differ significantly in phenotype, behaviour and genetics from their wild forerunners. It is the hope of breeding-back programs to re-express, within a new breeding lineage, the wild, ancient traits that may have "lain buried" in the DNA of domestic animals.

In many cases, the extinct wild type ancestors of a given species are known only through skeletons and, in some cases, historical descriptions, making their phenotype poorly understood. Given that situation, there is currently no certainty of achieving success with a back-breeding attempt, and any results must be reviewed with great caution. In order to test genetic closeness, DNA (both mitochondrial and nuclear) of the breeding animals must be compared against that of the extinct animal.

Successful breeding back might be possible: humans have selected animals only for superficial traits, and as a rule did not intentionally change less-observable traits, such as metabolic biochemistry.[1] Further, since many domestic species show behaviours derived from their wild ancestors (such as the herding instinct of cattle or the social instincts of dogs), and are fit to survive outside the sphere of human interference (as evidenced by the many feral populations of various domestic animals), it can be presumed that "bred back" animals might be able to function like their wild ancestors.[1] For example, food preferences are assumed to be largely the same in domesticated animals as in their wild type ancestors.

Natural selection might serve as an additional tool in creating "authentic" robustness, "authentic" behaviour, and perhaps, the original phenotype as well. In some cases, a sufficient predator population would be necessary to enable such a selection process; in today's Europe, where many breeding-back attempts take place, this predator population is largely absent.

Use

Bred-back breeds are desirable in conservation biology, as they may fill an ecological gap left open by the extinction of a wild type due to human activities. As long as food preference, behaviour, robustness, defence against predators, hunting or foraging instincts and phenotype are the same as in the wild type, the bred-back phenotype will function similarly in the ecosystem. Releasing such animals into the wild would re-fill the previously empty niche, and allow a natural dynamic among the various species of the ecosystem to re-establish. However, not all breeding-back attempts will result in an animal that is closer to the wild type than are primitive domestic breeds. For example, Heck cattle bear less resemblance to the aurochs than do many Iberian fighting cattle.[1]

Examples

Aurochs

Ideas for creating an aurochs-like animal from domestic cattle have been around since 1835. In the 1920s, Heinz and Lutz Heck tried to breed an aurochs look-alike, using central European dairy breeds and southern European cattle. The result, Heck cattle, are hardy, but differ from the aurochs in many respects, although a resemblance in colour and, less reliably, horns has been achieved.[1] From 1996 onwards, Heck cattle have been crossed with "primitive" Iberian breeds like Sayaguesa Cattle and fighting cattle, as well as the very large Italian breed Chianina, in a number of German reserves, in order to enhance the resemblance to the aurochs. The results are called Taurus cattle, being larger and longer-legged than Heck cattle and having more aurochs-like horns. Another of the projects to achieve a type of cattle that resembles the aurochs is the TaurOs Project, using primitive, hardy southern European breeds, along with Scottish Highland cattle.

European wild horse

The Polish Konik horse is often erroneously considered the result of a breeding-back experiment to "recreate" the phenotype of the Tarpan. The Konik is actually a hardy landrace breed originating in Poland, which was called Panje horse before agriculturist Tadeusz Vetulani coined the name "Konik" in the 1920s. Vetulani started an experiment to reconstruct the Tarpan using Koniks; ultimately, his stock made only a minor contribution to the present-day Konik population.[2]

During the Second World War, the Heck brothers crossed Koniks with Przewalski's horses and ponies, such as the Icelandic horse and the Gotland pony; the result is now called the Heck Horse. During recent decades, Heck horses have been continually crossed with Koniks, making the two phenotypes at present nearly indistinguishable, excepting that the Heck horse tends to have a lighter build.[3]

Pigs

Boar–pig hybrids, which are hybrids of wild boars and domestic pigs and exist as an invasive species throughout Eurasia, the Americas, Australia, and in other places where European settlers imported wild boars to use as game animals, are also used for selective breeding to re-create the type of pigs represented in prehistoric artworks dating from the Iron Age and earlier in ancient Europe. A project to create them, under the name of the Iron Age pig, started in the early 1980s by crossing a male wild boar with a Tamworth sow to produce an animal resembling what Iron Age pigs are believed to have looked like.[4] Iron Age pigs are generally only raised in Europe for the specialty meat market, and in keeping with their heritage are generally more aggressive and harder to handle than purebred domesticated pigs.[4]

Quagga

The Quagga Project is an attempt, based in South Africa, to breed animals which strongly resemble the now-extinct quagga, a subspecies of the plains zebra which died out in 1883. Accordingly, the project is limited to selecting for the physical appearance of the original, as recorded by twenty-three mounted specimens, many contemporary illustrations, and a number of written accounts of the animals.[5]

The two most noticeable characteristics of the quagga, fewer stripes and a darker pelage, are frequently observed to varying degrees in wild plains zebra populations. Animals with these two traits have been sought out for the Quagga Project breeding programme.[5] In its fourth breeding iteration, the Quagga Project has resulted in foals displaying faint to absent striping on the hind legs and body, although the brown background color of the extinct quagga has yet to emerge. The project refers to their animals as "Rau quaggas", after the project founder Reinhold Rau.[6]

The project has been criticized for its focus on the morphological characteristics of the quagga, as the extinct animal may have possessed unrecorded behavioral or non-visible traits that would be impossible to reliably breed back from plains zebras.[5]

Wolf

Although the wolf, the wild ancestor of domestic dogs, is not extinct, its phenotype is the target of several developmental breeds including the Northern Inuit Dog and the Tamaskan Dog. They are all crossbreeds of German Shepherds, Alaskan Malamutes and huskies, selected for phenotypic wolf characteristics. These new breeds may be viewed as breeding-back attempts as well.[7]

Although extinct, Japanese wolf DNA survives in the modern domestic Shikoku Inu. It is thought that crossing this breed with some subspecies of Asian wolves would result in an authentic analogue to fill the ecological niche left empty in the absence of this apex predator.[citation needed]

The Dire Wolf Project, started in 1988, aims to bring back the look of the extinct prehistoric dire wolf by breeding different domestic dog breeds that resemble it.[8]

See also

References

- "The Dire Wolf Project". www.direwolfproject.com. Archived from the original on 6 May 2020. Retrieved 16 July 2019.

Further reading

- Koene, P., & Gremmen, B. (2001). Genetics of dedomestication in large herbivores. In 35th ISAE Conference, Davis, California, 2001 (pp. 68–68).

External links

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Breeding_back

A feral (from Latin fera 'a wild beast') animal or plant is one that lives in the wild but is descended from domesticated individuals. As with an introduced species, the introduction of feral animals or plants to non-native regions may disrupt ecosystems and has, in some cases, contributed to extinction of indigenous species. The removal of feral species is a major focus of island restoration.

Animals

A feral animal is one that has escaped from a domestic or captive status and is living more or less as a wild animal, or one that is descended from such animals.[1] Other definitions[2] include animals that have changed from being domesticated to being wild, natural, or untamed. Some common examples of animals with feral populations are horses, dogs, goats, cats, rabbits, camels, and pigs. Zoologists generally exclude from the feral category animals that were genuinely wild before they escaped from captivity: neither lions escaped from a zoo nor the white-tailed eagles re-introduced to the UK are regarded as feral.[3]

Plants

Domesticated plants that revert to wild are referred to as escaped, introduced, naturalized, or sometimes as feral crops. Individual plants are known as volunteers. Large numbers of escaped plants may become a noxious weed. The adaptive and ecological variables seen in plants that go wild closely resemble those of animals. Feral populations of crop plants, along with hybridization between crop plants and their wild relatives, brings a risk that genetically engineered characteristics such as pesticide resistance could be transferred to weed plants.[4] The unintended presence of genetically modified crop plants or of the modified traits in other plants as a result of cross-breeding is known as "adventitious presence (AP)".[5][6]

Variables

Certain familiar animals go feral easily and successfully, while others are much less inclined to wander and usually fail promptly outside domestication. Some species will detach readily from humans and pursue their own devices, but do not stray far or spread readily. Others depart and are gone, seeking out new territory or range to exploit and displaying active invasiveness. Whether they leave readily and venture far, the ultimate criterion for success is longevity. Persistence depends on their ability to establish themselves and reproduce reliably in the new environment. Neither the duration nor the intensity with which a species has been domesticated offers a useful correlation with its feral potential.[citation needed]

Species of feral animals

The cat returns readily to a feral state if it has not been socialized when young. Feral cats, especially if left to proliferate, are frequently considered to be pests in both rural and urban areas, and may be blamed for devastating the bird, reptile, and mammal populations. A local population of feral cats living in an urban area and using a common food source is sometimes called a feral cat colony. As feral cats multiply quickly, it is difficult to control their populations. Animal shelters attempt to adopt out feral cats, especially kittens, but often are overwhelmed with sheer numbers and euthanasia is used. In rural areas, excessive numbers of feral cats are often shot.[citation needed] The "trap-neuter-return" method has been used in many locations as an alternative means of managing the feral cat population.[citation needed]

The goat is one of the oldest domesticated creatures, yet readily returns to a feral state. Sheep are close contemporaries and cohorts of goats in the history of domestication, but the domestic sheep is vulnerable to predation and injury, and thus rarely seen in a feral state. However, in places where there are few predators, they may thrive, for example in the case of the Soay sheep. Both goats and sheep were sometimes intentionally released and allowed to go feral on island waypoints frequented by mariners, to serve as a ready food source.

The dromedary camel, which has been domesticated for over 3,000 years, will also readily go feral. A substantial population of feral dromedaries, descended from pack animals that escaped in the 19th and early 20th centuries, thrives in the Australian interior today.

Water buffalo run rampant in Western and Northern Australia. The Australian government encourages the hunting of feral water buffalo because of their large numbers.

Cattle have been domesticated since the neolithic era, but can survive on open range for months or years with little or no supervision.[7] Their ancestors, the aurochs, were aggressive, similar to the modern Cape buffalo. Modern cattle, especially those raised on open range, are generally more docile, but when threatened can display aggression. Cattle, particularly those raised for beef, are often allowed to roam quite freely and have established long term independence in Australia, New Zealand and several Pacific Islands along with small populations of semi-feral animals roaming the southwestern United States and northern Mexico. Such cattle are variously called mavericks, scrubbers or cleanskins. Most free roaming cattle, however untamed, are generally too valuable not to be eventually rounded up and recovered in closely settled regions.

Horses and donkeys, domesticated about 5000 BC, are feral in open grasslands worldwide. In Australia, they are called Brumbies; in the American west, they are called mustangs. Other isolated feral populations exist, including the Chincoteague Pony and the Banker horse. They are often referred to as "wild horses", but this is a misnomer. There are truly "wild" horses that have never been domesticated, most notably Przewalski's horse.[8] While the horse was originally indigenous to North America, the wild ancestor died out at the end of the last ice age. In both Australia and the Americas, modern "wild" horses descended from domesticated horses brought by European explorers and settlers that escaped, spread, and thrived. Australia hosts a feral donkey population, as do the Virgin Islands and the American southwest.

The pig has established feral populations worldwide, including in Australia, New Zealand, the United States, New Guinea and the Pacific Islands. Pigs were introduced to the Melanesian and Polynesian regions by humans from several thousand to 500 years ago, and to the Americas within the past 500 years. In Australia, domesticated pigs escaped in the 18th century, and now cover 40 percent of Australia,[9] with a population estimated at 30 million. While pigs are thought to have been brought to New Zealand by the original Polynesian settlers, this population had become extinct by the time of European colonization, and all feral pigs in New Zealand today are descendants of European stock.[citation needed] Many European wild boar populations are also partially descended from escaped domestic pigs and are thus feral animals within the native range of the ancestral species.[citation needed]

Rock pigeons were formerly kept for their meat or more commonly as racing animals and have established feral populations in cities worldwide.

Colonies of honey bees often escape into the wild from managed apiaries when they swarm; their behavior, however, is no different from their behavior in captivity, unless they breed with other feral honey bees of a different genetic stock, which may lead them to become more docile or more aggressive (see Africanized bees).

Large colonies of feral parrots are present in various parts of the world, with rose-ringed parakeets, monk parakeets and red-masked parakeets (the latter of which became the subject of the documentary film, The Wild Parrots of Telegraph Hill) being particularly successful outside of their native habitats and adapting well to suburban environments.

Wild cocks are derived from domestic chickens (Gallus gallus domesticus) who have returned to the wild. Like the red junglefowl (the closest wild relative of domestic chickens), wild cocks will take flight and roost in tall trees and bushes in order to avoid predators at night. Wild cocks typically form social groups composed of, a dominant cockerel, several hens, and subordinate cocks. Sometimes the dominant cockerel is designated by a fight between cocks.[10]

Effects of feralization

Ecological impact

A feral population can have a significant impact on an ecosystem by predation on vulnerable plants or animals, or by competition with indigenous species. Feral plants and animals constitute a significant share of invasive species, and can be a threat to endangered species. However, they may also replace species lost from an ecosystem on initial human arrival to an area, or increase the biodiversity of a human-altered area by being able to survive in it in ways local species cannot. Feral zebu have been reintroduced in Kuno Wildlife Sanctuary in order to replace their ancestor, the aurochs.

Genetic pollution

Animals of domestic origin sometimes can produce fertile hybrids with native, wild animals which leads to genetic pollution (not a clear term itself) in the naturally evolved wild gene pools, many times threatening rare species with extinction. Cases include the mallard duck, wild boar, the rock dove or pigeon, the red junglefowl (Gallus gallus) (ancestor of all chickens), carp, and more recently salmon.[11][full citation needed] Other examples of genetic swamping lie in the breeding history of dingoes. Dingoes are wild true dogs that will interbreed with dogs of other origins, thus leading to the proliferation of dingo hybrids and the possibility of the extinction of pure wild dingoes.[12] Researches in Scotland have remarked on a similar phenomenon of the genetic mixing of feral domestic cats and their wild counterparts.[13]

Economic harm

Feral animals compete with domestic livestock, and may degrade fences, water sources, and vegetation (by overgrazing or introducing seeds of invasive plants). Although hotly disputed, some cite as an example the competition between feral horses and cattle in the western United States. Another example is of goats competing with cattle in Australia, or goats that degrade trees and vegetation in environmentally-stressed regions of Africa. Accidental crossbreeding by feral animals may result in harm to breeding programs of pedigreed animals; their presence may also excite domestic animals and push them to escape. Feral populations can also pass on transmissible infections to domestic herds. Loss to farmers by aggressive feral dog population is common in India.

Economic benefits

Many feral animals can sometimes be captured at little cost and thus constitute a significant resource. Throughout most of Polynesia and Melanesia feral pigs constitute the primary sources of animal protein. Prior to the Wild and Free-Roaming Horses and Burros Act of 1971, American mustangs were routinely captured and sold for horsemeat. In Australia feral goats, pigs and dromedaries are harvested for the export for their meat trade. At certain times, animals were sometimes deliberately left to go feral, typically on islands,[citation needed] in order to be later recovered for profit or food use for travelers (particularly sailors) at the end of a few years.

Scientific value

Populations of feral animals present good sources for studies of population dynamics, and especially of ecology and behavior (ethology) in a wide state of species known mainly in a domestic state. Such observations can provide useful information for the stock breeders or other owners of the domesticated conspecifics (i.e. animals of the same species).

Cultural or historic value

American mustangs have been protected since 1971 in part due to their romance and connection to the history of the American West. A similar situation is that of the Danube Delta horse from the Letea Forest in the Danube Delta. The Romanian government is considering the protection of the feral horses and transforming them into a tourist attraction, after it first approved the killing of the entire population. Due to the intervention of numerous organizations and widespread popular disapproval of the Romanians the horses have been saved, but still have an uncertain fate as their legal status is unclear and local people continue to claim the right to use the horses in their own interest.[14]

See also

References

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty |title= (help)

- "Noah's Ark – Project Horses Romania". Archived from the original on February 20, 2012.

External links

The dictionary definition of feral at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of feral at Wiktionary

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Feral

De-extinction (also known as resurrection biology, or species revivalism) is the process of generating an organism that either resembles or is an extinct species.[1] There are several ways to carry out the process of de-extinction. Cloning is the most widely proposed method, although genome editing and selective breeding have also been considered. Similar techniques have been applied to certain endangered species, in hopes to boost their genetic diversity. The only method of the three that would provide an animal with the same genetic identity is cloning.[2] There are benefits and malefits to the process of de-extinction ranging from technological advancements to ethical issues.

Methods

Cloning

Cloning is a commonly suggested method for the potential restoration of an extinct species. It can be done by extracting the nucleus from a preserved cell from the extinct species and swapping it into an egg, without a nucleus, of that species' nearest living relative.[3] The egg can then be inserted into a host from the extinct species' nearest living relative. It is important to note that this method can only be used when a preserved cell is available, meaning it would be most feasible for recently extinct species.[4] Cloning has been used by scientists since the 1950s.[5] One of the most well known clones is Dolly the sheep. Dolly was born in the mid 1990s and lived normally until the abrupt midlife onset of health complications resembling premature aging, that led to her death.[5] Other known cloned animal species include domestic cats, dogs, pigs, and horses.[5]

Genome editing

Genome editing has been rapidly advancing with the help of the CRISPR/Cas systems, particularly CRISPR/Cas9. The CRISPR/Cas9 system was originally discovered as part of the bacterial immune system.[6] Viral DNA that was injected into the bacterium became incorporated into the bacterial chromosome at specific regions. These regions are called clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats, otherwise known as CRISPR. Since the viral DNA is within the chromosome, it gets transcribed into RNA. Once this occurs, the Cas9 binds to the RNA. Cas9 can recognize the foreign insert and cleaves it.[6] This discovery was very crucial because now the Cas protein can be viewed as a scissor in the genome editing process.

By using cells from a closely related species to the extinct species, genome editing can play a role in the de-extinction process. Germ cells may be edited directly, so that the egg and sperm produced by the extant parent species will produce offspring of the extinct species, or somatic cells may be edited and transferred via somatic cell nuclear transfer. The result is an animal which is not completely the extinct species, but rather a hybrid of the extinct species and the closely related, non-extinct species. Because it is possible to sequence and assemble the genome of extinct organisms from highly degraded tissues, this technique enables scientists to pursue de-extinction in a wider array of species, including those for which no well-preserved remains exist.[3] However, the more degraded and old the tissue from the extinct species is, the more fragmented the resulting DNA will be, making genome assembly more challenging.

Back breeding

Back breeding is a form of selective breeding. As opposed to breeding animals for a trait to advance the species in selective breeding, back breeding involves breeding animals for an ancestral characteristic that may not be seen throughout the species as frequently.[7] This method can recreate the traits of an extinct species, but the genome will differ from the original species.[4] Back breeding, however, is contingent on the ancestral trait of the species still being in the population in any frequency.[7] Back breeding is also a form of artificial selection by the deliberate selective breeding of domestic animals, in an attempt to achieve an animal breed with a phenotype that resembles a wild type ancestor, usually one that has gone extinct. Breeding back is not to be confused with dedomestication.

Iterative evolution

A natural process of de-extinction is iterative evolution. This occurs when a species becomes extinct, but then after some time a different species evolves into an almost identical creature. For example, the Aldabra rail was a flightless bird that lived on the island of Aldabra. It had evolved some time in the past from the flighted white-throated rail, but became extinct about 136,000 years ago due to an unknown event that caused sea levels to rise. About 100,000 years ago, sea levels dropped and the island reappeared, with no fauna. The white-throated rail recolonized the island, but soon evolved into a flightless species taxonomically identical to the extinct species.[8][9][10]

Advantages of de-extinction

The technologies being developed for de-extinction could lead to large advances in various fields:

- An advance in genetic technologies that are used to improve the cloning process for de-extinction could be used to prevent endangered species from becoming extinct.[11]

- By studying revived previously extinct animals, cures to diseases could be discovered.

- Revived species may support conservation initiatives by acting as "flagship species" to generate public enthusiasm and funds for conserving entire ecosystems.[12][13]

Prioritising de-extinction could lead to the improvement of current conservation strategies. Conservation measures would initially be necessary in order to reintroduce a species into the ecosystem, until the revived population can sustain itself in the wild.[14] Reintroduction of an extinct species could also help improve ecosystems that had been destroyed by human development. It may also be argued that reviving species driven to extinction by humans is an ethical obligation.[15]

Disadvantages of de-extinction

The reintroduction of extinct species could have a negative impact on extant species and their ecosystem. The extinct species' ecological niche may have been filled in its former habitat, making it an invasive species. This could lead to the extinction of other species due to competition for food or other competitive exclusion. It could also lead to the extinction of prey species if they have more predators in an environment that had few predators before the reintroduction of an extinct species.[15] If a species has been extinct for a long period of time the environment they are introduced to could be wildly different from the one that they can survive in. The changes in the environment due to human development could mean that the species may not survive if reintroduced into that ecosystem.[11] A species could also become extinct again after de-extinction if the reasons for its extinction are still a threat. The woolly mammoth might be hunted by poachers just like elephants for their ivory and could go extinct again if this were to happen. Or, if a species is reintroduced into an environment with disease it has no immunity to the reintroduced species could be wiped out by a disease that current species can survive.

De-extinction is a very expensive process. Bringing back one species can cost millions of dollars. The money for de-extinction would most likely come from current conservation efforts. These efforts could be weakened if funding is taken from conservation and put into de-extinction. This would mean that critically endangered species would start to go extinct faster because there are no longer resources that are needed to maintain their populations.[16] Also, since cloning techniques cannot perfectly replicate a species as it existed in the wild, the reintroduction of the species may not bring about positive environmental benefits. They may not have the same role in the food chain that they did before and therefore cannot restore damaged ecosystems.[17]

Current candidates for de-extinction

Woolly mammoth

This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2019) |

The existence of preserved soft tissue remains and DNA from woolly mammoths (Mammuthus primigenius) has led to the idea that the species could be recreated by scientific means. Two methods have been proposed to achieve this. The first would be to use the cloning process, however even the most intact mammoth samples have had little usable DNA because of their conditions of preservation. There is not enough DNA intact to guide the production of an embryo.[18] The second method would involve artificially inseminating an elephant egg cell with preserved sperm of the mammoth. The resulting offspring would be a hybrid of the mammoth and its closest living relative the Asian elephant. After several generations of cross-breeding these hybrids, an almost pure woolly mammoth could be produced. However, sperm cells of modern mammals are typically potent for up to 15 years after deep-freezing, which could hinder this method.[19] In 2008, a Japanese team found usable DNA in the brains of mice that had been frozen for 16 years. They hope to use similar methods to find usable mammoth DNA.[20] In 2011, Japanese scientists announced plans to clone mammoths within six years.[21]

In March 2014, the Russian Association of Medical Anthropologists reported that blood recovered from a frozen mammoth carcass in 2013 would now provide a good opportunity for cloning the woolly mammoth.[19] Another way to create a living woolly mammoth would be to migrate genes from the mammoth genome into the genes of its closest living relative, the Asian elephant, to create hybridized animals with the notable adaptations that it had for living in a much colder environment than modern day elephants. This is currently being done by a team led by Harvard geneticist George Church.[22] The team has made changes in the elephant genome with the genes that gave the woolly mammoth its cold-resistant blood, longer hair, and an extra layer of fat.[22] According to geneticist Hendrik Poinar, a revived woolly mammoth or mammoth-elephant hybrid may find suitable habitat in the tundra and taiga forest ecozones.[23]

George Church has hypothesized the positive effects of bringing back the extinct woolly mammoth would have on the environment, such as the potential for reversing some of the damage caused by global warming.[24] He and his fellow researchers predict that mammoths would eat the dead grass allowing the sun to reach the spring grass; their weight would allow them to break through dense, insulating snow in order to let cold air reach the soil; and their characteristic of felling trees would increase the absorption of sunlight.[24] In an editorial condemning de-extinction, Scientific American pointed out that the technologies involved could have secondary applications, specifically to help species on the verge of extinction regain their genetic diversity.[25]

Pyrenean ibex

The Pyrenean ibex (Capra pyrenaica pyrenaica) was a subspecies of Spanish ibex that lived on the Iberian Peninsula. While it was abundant through medieval times, over-hunting in the 19th and 20th centuries led to its demise. In 1999, only a single female named Celia was left alive in Ordesa National Park. Scientists captured her, took a tissue sample from her ear, collared her, then released her back into the wild, where she lived until she was found dead in 2000, having been crushed by a fallen tree.

In 2003, scientists used the tissue sample to attempt to clone Celia and resurrect the extinct subspecies. Despite having successfully transferred nuclei from her cells into domestic goat egg cells and impregnating 208 female goats, only one came to term. The baby ibex that was born had a lung defect, and lived for only seven minutes before suffocating from being incapable of breathing oxygen. Nevertheless, her birth was seen as a triumph and is considered the first de-extinction.[26] In late 2013, scientists announced that they would again attempt to resurrect the Pyrenean ibex.

A problem to be faced, in addition to the many challenges of reproduction of a mammal by cloning, is that only females can be produced by cloning the female individual Celia, and no males exist for those females to reproduce with. This could potentially be addressed by breeding female clones with the closely related Southeastern Spanish ibex, and gradually creating a hybrid animal that will eventually bear more resemblance to the Pyrenean ibex than the Southeastern Spanish ibex.[27]

Aurochs

The aurochs (Bos primigenius) was widespread across Eurasia, North Africa, and the Indian subcontinent during the Pleistocene, but only the European aurochs (B. p. primigenius) survived into historical times.[28] This species is heavily featured in European cave paintings, such as Lascaux and Chauvet cave in France,[29] and was still widespread during the Roman era. Following the fall of the Roman Empire, overhunting of the aurochs by nobility caused its population to dwindle to a single population in the Jaktorów forest in Poland, where the last wild one died in 1627.[30]

However, because the aurochs is ancestral to most modern cattle breeds, it is possible for it to be brought back through selective or back breeding. The first attempt at this was by Heinz and Lutz Heck using modern cattle breeds, which resulted in the creation of Heck cattle. This breed has been introduced to nature preserves across Europe; however, it differs strongly from the aurochs in physical characteristics, and some modern attempts claim to try to create an animal that is nearly identical to the aurochs in morphology, behavior, and even genetics.[31] There are several projects that aim to create a cattle breed similar to the aurochs through selectively breeding primitive cattle breeds over a course of twenty years to create a self-sufficient bovine grazer in herds of at least 150 animals in rewilded nature areas across Europe, for example the Tauros Programme and the separate Taurus Project.[32] This organization is partnered with the organization Rewilding Europe to help revert some European natural ecosystems to their prehistoric form.[33]

A competing project to recreate the aurochs is the Uruz Project by the True Nature Foundation, which aims to recreate the aurochs by a more efficient breeding strategy using genome editing, in order to decrease the number of generations of breeding needed and the ability to quickly eliminate undesired traits from the population of aurochs-like cattle.[34] It is hoped that aurochs-like cattle will reinvigorate European nature by restoring its ecological role as a keystone species, and bring back biodiversity that disappeared following the decline of European megafauna, as well as helping to bring new economic opportunities related to European wildlife viewing.[35]

Quagga

The quagga (Equus quagga quagga) is a subspecies of the plains zebra that was distinct in that it was striped on its face and upper torso, but its rear abdomen was a solid brown. It was native to South Africa, but was wiped out in the wild due to overhunting for sport, and the last individual died in 1883 in the Amsterdam Zoo.[36] However, since it is technically the same species as the surviving plains zebra, it has been argued that the quagga could be revived through artificial selection. The Quagga Project aims to breed a similar form of zebra by selective breeding of plains zebras.[37] This process is also known as back breeding. It also aims to release these animals onto the western Cape once an animal that fully resembles the quagga is achieved, which could have the benefit of eradicating introduced species of trees such as the Brazilian pepper tree, Tipuana tipu, Acacia saligna, bugweed, camphor tree, stone pine, cluster pine, weeping willow and Acacia mearnsii.[38]

Thylacine

The thylacine (Thylacinus cynocephalus), commonly known as the Tasmanian tiger, was native to the Australian mainland, Tasmania and New Guinea. It is believed to have become extinct in the 20th century. The thylacine had become extremely rare or extinct on the Australian mainland before British settlement of the continent. The last known thylacine died at the Hobart Zoo, on September 7, 1936. He is believed to have died as the result of neglect—locked out of his sheltered sleeping quarters, he was exposed to a rare occurrence of extreme Tasmanian weather: extreme heat during the day and freezing temperatures at night.[39] Official protection of the species by the Tasmanian government was introduced on July 10, 1936, roughly 59 days before the last known specimen died in captivity.[40]

In December 2017 it was announced in Nature Ecology and Evolution that the full nuclear genome of the thylacine had been successfully sequenced, marking the completion of the critical first step toward de-extinction that began in 2008, with the extraction of the DNA samples from the preserved pouch specimen.[41] The thylacine genome was reconstructed by using the genome editing method. The Tasmanian devil was used as a reference for the assembly of the full nuclear genome.[42] Andrew J. Pask from the University of Melbourne has stated that the next step toward de-extinction will be to create a functional genome, which will require extensive research and development, estimating that a full attempt to resurrect the species may be possible as early as 2027.[41]

In August 2022, the University of Melbourne and Colossal Biosciences announced a partnership to accelerate de-extinction of the thylacine via genetic modification of one of its closest living relatives, the fat-tailed dunnart.[43]

Passenger pigeon

The passenger pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius) numbered in the billions before being wiped out due to unsustainable commercial hunting and habitat loss during the early 20th century. The non-profit Revive & Restore obtained DNA from the passenger pigeon from museum specimens and skins; however, this DNA is degraded because it is so old. For this reason, simple cloning would not be an effective way to perform de-extinction for this species because parts of the genome would be missing. Instead, Revive & Restore focuses on identifying mutations in the DNA that would cause a phenotypic difference between the extinct passenger pigeon and its closest living relative, the band-tailed pigeon. In doing this, they can determine how to modify the DNA of the band-tailed pigeon to change the traits to mimic the traits of the passenger pigeon. In this sense, the de-extinct passenger pigeon would not be genetically identical to the extinct passenger pigeon, but it would have the same traits. The de-extinct passenger pigeon hybrid is expected to be ready for captive breeding by 2024 and released into the wild by 2030.[44]

Maclear's rat

The Maclear's rat (Rattus macleari), also known as the Christmas Island rat, was a large rat endemic to Christmas Island in the Indian Ocean. It is believed Maclear's rat might have been responsible for keeping the population of Christmas Island red crab in check. It is thought that the accidental introduction of black rats by the Challenger expedition infected the Maclear's rats with a disease (possibly a trypanosome),[45] which resulted in the numbers of the species declining.[46] The last recorded sighting was in 1903.[47] In March 2022, researchers discovered the Maclear's Rat shared about 95 percent of its genes with the living brown rat, thus sparking hopes in bringing the species back to life. Although scientists were mostly successful in using CRISPR technology to edit the DNA of the living species to match that of the extinct one, a few key genes were missing, which would mean resurrected rats would not be genetically pure replicas.[48]

Future potential candidates for de-extinction

A "De-extinction Task Force" was established in April 2014 under the auspices of the Species Survival Commission (SSC) and charged with drafting a set of Guiding Principles on Creating Proxies of Extinct Species for Conservation Benefit to position the IUCN SSC on the rapidly emerging technological feasibility of creating a proxy of an extinct species.[49]

Birds

- Little bush moa – A slender species of moa slightly larger than a turkey that went extinct abruptly, around 500-600 years ago following the arrival and proliferation of the Māori people in New Zealand, as well as the introduction of Polynesian dogs.[50] Scientists at Harvard University assembled the first nearly complete genome of the species from toe bones, thus bringing the species a step closer to being "resurrected".[51][52] New Zealand politician Trevor Mallard had previously suggested bringing back a medium-sized species of moa.[53]

- Heath hen – This subspecies of the prairie chicken became extinct on Martha's Vineyard in 1932 despite conservation efforts; however, the availability of usable DNA in museum specimens and protected areas in its former range makes this bird a possible candidate for de-extinction and reintroduction to its former habitat.[54]

- Dodo – This large, flightless ground bird endemic to Mauritius was last sighted in the 1640s and was most likely extinct by 1700, due to exploitation by humans and due to introduced species such as rats and pigs, which ate their eggs. It has since become a symbol of extinction in popular culture. Due to a wealth of bones and some tissues, it is possible that this species may live again as it has a close relative in the surviving Nicobar pigeon.[55]

- Elephant bird – Some of the largest birds to have ever existed, the elephant birds were driven to extinction by the early colonization of Madagascar. Ancient DNA has been obtained from the eggshells but may be too degraded for use in de-extinction.[56][57]

- Carolina parakeet - One of the only indigenous parrots to North America, it was driven to extinction by destruction of its habitat, overhunting, competition from introduced honeybees, and persecution for crop damages. Hundreds of specimens with viable DNA still exist in museums around the world, making them a prime candidate for revival.[56][52]

- Great auk - A flightless bird native to the North Atlantic similar to the penguin. The great auk went extinct in the 1800s due to overhunting by humans for food. The last two known great auks lived on an island near Iceland and were clubbed to death by sailors. There have been no known sightings since.[58] The great auk has been identified as a good candidate for de-extinction by Revive and Restore, a non-profit organization. Because the great auk is extinct it cannot be cloned, but its DNA can be used to alter the genome of its closest relative, the razorbill, and breed the hybrids to create a species that will be very similar to the original great auks. The plan is to introduce them back into their original habitat, which they would then share with razorbills and puffins, who are also at risk for extinction. This would help restore the biodiversity and restore that part of the ecosystem.[59]

- Imperial woodpecker[56][52]

- Ivory-billed woodpecker[56][52]

- Cuban macaw[56][52]

- Labrador duck[56][52]

- Huia[56][52]

- Moho[56][52]

- Nēnē-nui[56][52]

- New Zealand swan[56][52]

- New Zealand merganser[56][52]

- Chatham Island merganser[56][52]

- Mascarene teal[56][52]

- Mariana mallard[56][52]

- Anas chathamica[56][52]

- Amsterdam wigeon[56][52]

- Malagasy shelduck[56][52]

- Mauritius sheldgoose[56][52]

- Réunion sheldgoose[56][52]

- New Zealand musk duck[56][52]

Mammals

- Caribbean monk seal[56][52]

- Irish elk[56][52]

- Cave lion – The discovery of two preserved cubs in the Sakha Republic ignited a project to clone the animal.[60][61]

- Steppe bison – The discovery of the mummified steppe bison of 9,000 years ago could help people clone the ancient bison species back, even though the steppe bison would not be the first to be "resurrected".[62] Russian and South Korean scientists are collaborating to clone steppe bison in the future, using DNA preserved from a 8,000 year old tail,[63][64] in wood bison, which themselves have been introduced to Yakutia to fulfill a similar niche.

- Tarpan – A population of free-ranging horses in Europe that went extinct in 1909. Much like the aurochs, there have been many attempts to breed tarpan-like horses from domestic horses, the first being by the Heck brothers, creating the Heck horse as a result. Though it is not a genetic copy, it is claimed to bear many similarities to the tarpan.[65] Other attempts were made to create tarpan-like horses. A breeder named Harry Hegardt was able to breed a line of horses from American Mustangs.[66] Other breeds of supposedly tarpan-like horse include the Konik and Strobel's horse.[citation needed]

- Baiji[52]

- Steller's sea cow[56][52]

- Woolly rhinoceros[56][52]

- Cave bear[56][52]

Reptiles

- Floreana Island tortoise – In 2008, mitochondrial DNA from the Floreana tortoise species was found in museum specimens. In theory, a breeding program could be established to "resurrect" a pure Floreana species from living hybrids.[67][68]

Amphibians

- Gastric-brooding frog – In 2013, scientists in Australia successfully created a living embryo from non-living preserved genetic material, and hope that by using somatic-cell nuclear transfer methods, they can produce an embryo that can survive to the tadpole stage.[56][69]

Insects

Plants

See also

References

Further reading

- O'Connor, M.R. (2015). Resurrection Science: Conservation, De-Extinction and the Precarious Future of Wild Things. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 9781137279293. Archived from the original on 2016-07-04.

- Shapiro, Beth (2015). How to Clone a Mammoth: The Science of De-Extinction. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691157054.

- Pilcher, Helen (2016). Bring Back the King: The New Science of De-extinction Archived 2021-05-07 at the Wayback Machine. Bloomsbury Press ISBN 9781472912251

External links

- TEDx DeExtinction March 15, 2013 conference sponsored by Revive and Restore project of the Long Now Foundation, supported by TEDx and hosted by the National Geographic Society, that helped popularize the public understanding of the science of de-extinction. Video proceedings, meeting report, and links to press coverage freely available.

- De-Extinction: Bringing Extinct Species Back to Life April 2013 article by Carl Zimmer for National Geographic magazine reporting on 2013 conference.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/De-extinction

| Part of the Politics series |

| Politics |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Law |

|---|

|

| Foundations and Philosophy |

| Legal theory |

| Methodological background |

Bureaucracy (/bjʊəˈrɒkrəsi/) is a body of non-elected governing officials or an administrative policy-making group.[1] Historically, a bureaucracy was a government administration managed by departments staffed with non-elected officials.[2] Today, bureaucracy is the administrative system governing any large institution, whether publicly owned or privately owned.[3] The public administration in many jurisdictions and sub-jurisdictions exemplifies bureaucracy, but so does any centralized hierarchical structure of an institution, e.g. hospitals, academic entities, business firms, professional societies, social clubs, etc.

There are two key dilemmas in bureaucracy. The first dilemma revolves around whether bureaucrats should be autonomous or directly accountable to their political masters.[4] The second dilemma revolves around bureaucrats' responsibility to follow procedure, regulation and law or the amount of latitude they may have to determine appropriate solutions for circumstances that may appear unaccounted for in advance.[4]

Various commentators have argued for the necessity of bureaucracies in modern society. The German sociologist Max Weber (1864–1920) argued that bureaucracy constitutes the most efficient and rational way in which human activity can be organized and that systematic processes and organized hierarchies are necessary to maintain order, to maximize efficiency, and to eliminate favoritism. On the other hand, Weber also saw unfettered bureaucracy as a threat to individual freedom, with the potential of trapping individuals in an impersonal "iron cage" of rule-based, rational control.[5][6]

Etymology and usage

The term "bureaucracy" originated in the French language: it combines the French word bureau – desk or office – with the Greek word κράτος (kratos) – rule or political power.[7] The French economist Jacques Claude Marie Vincent de Gournay (1712–1759) coined the word in the mid-18th century.[8] Gournay never wrote the term down but a letter from a contemporary later quoted him:

The late M. de Gournay... sometimes used to say: "We have an illness in France which bids fair to play havoc with us; this illness is called bureaumania." Sometimes he used to invent a fourth or fifth form of government under the heading of "bureaucracy."

— Baron von Grimm (1723–1807)[9]

The first known English-language use dates to 1818[7] with Irish novelist Lady Morgan referring to the apparatus used by the British government to subjugate Ireland as "the Bureaucratie, or office tyranny, by which Ireland has so long been governed".[10] By the mid-19th century the word appeared in a more neutral sense, referring to a system of public administration in which offices were held by unelected career officials. In this context "bureaucracy" was seen as a distinct form of management, often subservient to a monarchy.[11] In the 1920s the German sociologist Max Weber expanded the definition to include any system of administration conducted by trained professionals according to fixed rules.[11] Weber saw bureaucracy as a relatively positive development; however, by 1944 the Austrian economist Ludwig von Mises opined in the context of his experience in the Nazi regime that the term bureaucracy was "always applied with an opprobrious connotation",[12] and by 1957 the American sociologist Robert Merton suggested that the term "bureaucrat" had become an "epithet, a Schimpfwort" in some circumstances.[13]

The word "bureaucracy" is also used in politics and government with a disapproving tone to disparage official rules that appear to make it difficult—by insistence on procedure and compliance to rule, regulation, and law—to get things done.[by whom?] In workplaces, the word is used[by whom?] very often to blame complicated rules, processes, and written work that are interpreted as obstacles rather than safeguards and accountability assurances.[14] Socio-bureaucracy would then refer to certain social influences that may affect the function of a society.[15]

In modern usage, modern bureaucracy has been defined as comprising four features:[16]

- hierarchy (clearly defined spheres of competence and divisions of labor)

- continuity (a structure where administrators have a full-time salary and advance within the structure)

- impersonality (prescribed rules and operating rules rather than arbitrary actions)

- expertise (officials are chosen according to merit, have been trained, and hold access to knowledge)

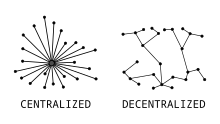

Bureaucracy in a political theory is mainly a centralized form of management and tends to be differentiated from adhocracy, in which management tends more to decentralization.

History

Ancient

Although the term "bureaucracy" first originated in the mid-18th century, organized and consistent administrative systems existed much earlier. The development of writing (c. 3500 BC) and the use of documents was critical to the administration of this system, and the first definitive emergence of bureaucracy occurred in ancient Sumer, where an emergent class of scribes used clay tablets to administer the harvest and to allocate its spoils.[17] Ancient Egypt also had a hereditary class of scribes that administered the civil-service bureaucracy.[18]

In China, when the Qin dynasty (221–206 BC) unified China under the Legalist system, the emperor assigned administration to dedicated officials rather than nobility, ending feudalism in China, replacing it with a centralized, bureaucratic government. The form of government created by the first emperor and his advisors was used by later dynasties to structure their own government.[19][20] Under this system, the government thrived, as talented individuals could be more easily identified in the transformed society. The Han dynasty (202 BC – 220 AD) established a complicated bureaucracy based on the teachings of Confucius, who emphasized the importance of ritual in a family, in relationships, and in politics.[21] With each subsequent dynasty, the bureaucracy evolved. In 165 BC, Emperor Wen introduced the first method of recruitment to civil service through examinations, while Emperor Wu (r. 141–87 BC), cemented the ideology of Confucius into mainstream governance installed a system of recommendation and nomination in government service known as xiaolian, and a national academy[22][23][24] whereby officials would select candidates to take part in an examination of the Confucian classics, from which Emperor Wu would select officials.[25]

In the Sui dynasty (581–618) and the subsequent Tang dynasty (618–907) the shi class would begin to present itself by means of the fully standardized civil service examination system, of partial recruitment of those who passed standard exams and earned an official degree. Yet recruitment by recommendations to office was still prominent in both dynasties. It was not until the Song dynasty (960–1279) that the recruitment of those who passed the exams and earned degrees was given greater emphasis and significantly expanded.[26] During the Song dynasty (960–1279) the bureaucracy became meritocratic. Following the Song reforms, competitive examinations took place to determine which candidates qualified to hold given positions.[27] The imperial examination system lasted until 1905, six years before the Qing dynasty collapsed, marking the end of China's traditional bureaucratic system.[28]

A hierarchy of regional proconsuls and their deputies administered the Roman Empire.[citation needed] The reforms of Diocletian (Emperor from 284 to 305) doubled the number of administrative districts and led to a large-scale expansion of Roman bureaucracy.[29] The early Christian author Lactantius (c. 250 – c. 325) claimed that Diocletian's reforms led to widespread economic stagnation, since "the provinces were divided into minute portions, and many presidents and a multitude of inferior officers lay heavy on each territory."[30] After the Empire split, the Byzantine Empire developed a notoriously complicated administrative hierarchy, and in the 20th century the term "Byzantine" came to refer to any complex bureaucratic structure.[31][32]

Modern

Ashanti Empire

The government of the Ashanti Empire was built upon a sophisticated bureaucracy in Kumasi, with separate ministries which saw to the handling of state affairs. Ashanti's Foreign Office was based in Kumasi. Despite the small size of the office, it allowed the state to pursue complex negotiations with foreign powers. The Office was divided into departments that handled Ashanti relations separately with the British, French, Dutch, and Arabs. Scholars of Ashanti history, such as Larry Yarak and Ivor Wilkes, disagree over the power of this sophisticated bureaucracy in comparison to the Asantehene. However, both scholars agree that it was a sign of a highly developed government with a complex system of checks and balances.[33]

United Kingdom

Instead of the inefficient and often corrupt system of tax farming that prevailed in absolutist states such as France, the Exchequer was able to exert control over the entire system of tax revenue and government expenditure.[34] By the late 18th century, the ratio of fiscal bureaucracy to population in Britain was approximately 1 in 1300, almost four times larger than the second most heavily bureaucratized nation, France.[35] Thomas Taylor Meadows, Britain's consul in Guangzhou, argued in his Desultory Notes on the Government and People of China (1847) that "the long duration of the Chinese empire is solely and altogether owing to the good government which consists in the advancement of men of talent and merit only", and that the British must reform their civil service by making the institution meritocratic.[36] Influenced by the ancient Chinese imperial examination, the Northcote–Trevelyan Report of 1854 recommended that recruitment should be on the basis of merit determined through competitive examination, candidates should have a solid general education to enable inter-departmental transfers, and promotion should be through achievement rather than "preferment, patronage, or purchase".[37][36] This led to implementation of Her Majesty's Civil Service as a systematic, meritocratic civil service bureaucracy.[38]

In the British civil service, just as it was in China, entrance to the civil service was usually based on a general education in ancient classics, which similarly gave bureaucrats greater prestige. The Cambridge-Oxford ideal of the civil service was identical to the Confucian ideal of a general education in world affairs through humanism.[39] (Well into the 20th century, Classics, Literature, History and Language remained heavily favoured in British civil service examinations.[40] In the period of 1925–1935, 67 percent of British civil service entrants consisted of such graduates.[41]) Like the Chinese model's consideration of personal values, the British model also took personal physique and character into account.[42]

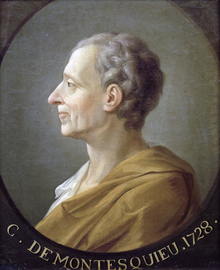

France

Like the British, the development of French bureaucracy was influenced by the Chinese system.[43] Under Louis XIV of France, the old nobility had neither power nor political influence, their only privilege being exemption from taxes. The dissatisfied noblemen complained about this "unnatural" state of affairs, and discovered similarities between absolute monarchy and bureaucratic despotism.[44] With the translation of Confucian texts during the Enlightenment, the concept of a meritocracy reached intellectuals in the West, who saw it as an alternative to the traditional ancien regime of Europe.[45] Western perception of China even in the 18th century admired the Chinese bureaucratic system as favourable over European governments for its seeming meritocracy; Voltaire claimed that the Chinese had "perfected moral science" and François Quesnay advocated an economic and political system modeled after that of the Chinese.[46] The governments of China, Egypt, Peru and Empress Catherine II were regarded as models of Enlightened Despotism, admired by such figures as Diderot, D'Alembert and Voltaire.[44]

Napoleonic France adopted this meritocracy system [45] and soon saw a rapid and dramatic expansion of government, accompanied by the rise of the French civil service and its complex systems of bureaucracy. This phenomenon became known as "bureaumania". In the early 19th century, Napoleon attempted to reform the bureaucracies of France and other territories under his control by the imposition of the standardized Napoleonic Code. But paradoxically, that led to even further growth of the bureaucracy.[47]

French civil service examinations adopted in the late 19th century were also heavily based on general cultural studies. These features have been likened to the earlier Chinese model.[42]

Other industrialized nations

By the mid-19th century, bureaucratic forms of administration were firmly in place across the industrialized world. Thinkers like John Stuart Mill and Karl Marx began to theorize about the economic functions and power-structures of bureaucracy in contemporary life. Max Weber was the first to endorse bureaucracy as a necessary feature of modernity, and by the late 19th century bureaucratic forms had begun their spread from government to other large-scale institutions.[11]

Within capitalist systems, informal bureaucratic structures began to appear in the form of corporate power hierarchies, as detailed in mid-century works like The Organization Man and The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit. Meanwhile, in the Soviet Union and Eastern Bloc nations, a powerful class of bureaucratic administrators termed nomenklatura governed nearly all aspects of public life.[48]

The 1980s brought a backlash against perceptions of "big government" and the associated bureaucracy. Politicians like Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan gained power by promising to eliminate government regulatory bureaucracies, which they saw as overbearing, and return economic production to a more purely capitalistic mode, which they saw as more efficient.[49][50] In the business world, managers like Jack Welch gained fortune and renown by eliminating bureaucratic structures inside corporations.[51] Still, in the modern world, most organized institutions rely on bureaucratic systems to manage information, process records, and administer complex systems, although the decline of paperwork and the widespread use of electronic databases is transforming the way bureaucracies function.[52]

Theories

Karl Marx

Karl Marx theorized about the role and function of bureaucracy in his Critique of Hegel's Philosophy of Right, published in 1843. In Philosophy of Right, Hegel had supported the role of specialized officials in public administration, although he never used the term "bureaucracy" himself. By contrast, Marx was opposed to bureaucracy. Marx posited that while corporate and government bureaucracy seem to operate in opposition, in actuality they mutually rely on one another to exist. He wrote that "The Corporation is civil society's attempt to become state; but the bureaucracy is the state which has really made itself into civil society."[53]

John Stuart Mill

Writing in the early 1860s, political scientist John Stuart Mill theorized that successful monarchies were essentially bureaucracies, and found evidence of their existence in Imperial China, the Russian Empire, and the regimes of Europe. Mill referred to bureaucracy as a distinct form of government, separate from representative democracy. He believed bureaucracies had certain advantages, most importantly the accumulation of experience in those who actually conduct the affairs. Nevertheless, he believed this form of governance compared poorly to representative government, as it relied on appointment rather than direct election. Mill wrote that ultimately the bureaucracy stifles the mind, and that "a bureaucracy always tends to become a pedantocracy."[54]

Max Weber

The fully developed bureaucratic apparatus compares with other organisations exactly as does the machine with the non-mechanical modes of production.

–Max Weber[55]

The German sociologist Max Weber was the first to formally study bureaucracy and his works led to the popularization of this term.[56] In his essay Bureaucracy,[1],[57] published in his magnum opus Economy and Society, Weber described many ideal-typical forms of public administration, government, and business. His ideal-typical bureaucracy, whether public or private, is characterized by:

- hierarchical organization

- formal lines of authority (chain of command)

- a fixed area of activity

- rigid division of labor

- regular and continuous execution of assigned tasks

- all decisions and powers specified and restricted by regulations

- officials with expert training in their fields

- career advancement dependent on technical qualifications

- qualifications evaluated by organizational rules, not individuals[5][58][59]