his article is about a means-based model of social welfare. For the system of unconditional income provided to every citizen, see Universal basic income. For the system where citizens receive an income stream through the public ownership of industry, see Social dividend.

Guaranteed minimum income (GMI), also called minimum income (or mincome for short),[1] is a social-welfare system that guarantees all citizens or families an income sufficient to live on, provided that certain eligibility conditions are met, typically: citizenship; a means test; and either availability to participate in the labor market, or willingness to perform community services.

The primary goal of a guaranteed minimum income is reduction of poverty. In circumstances when citizenship is the sole qualification, the program becomes a universal basic income system.

Elements

A system of guaranteed minimum income can consist of several elements, most notably:

- Calculation of the social minimum, usually below the minimum wage[2][3]

- Social safety net that helps those without sufficient financial means survive at the social minimum through payments or a loan, generally conditional on availability for work, performance of community services, some kind of social contract, or commitment to a social integration trajectory

- State child support

- Student loan and grants

- State pensions for the elderly

- Disability pensions for those who physically can't work

Differences from basic income

Basic income means the provision of identical payments from a government to all of its citizens. Guaranteed minimum income is a system of payments (possibly only one) by a government to citizens who fail to meet one or more means tests. While most modern countries have some form of GMI, a basic income is rare.

History

Pre-modern antecedents

Persian monarch Cyrus the Great ( ca 590-ca 529 B.C.), whose government used a regulated minimum wage, also provided special rations to families when a child was born.[4]

The Roman Republic and Empire offered the Cura Annonae, a regular distribution of free or subsidized grain or bread to poorer residents. The grain subsidy was first introduced by Gaius Gracchus in 123 B.C., then further institutionalized by Julius Caesar and Augustus Caesar.[5][6]

The first Sunni Muslim Caliph Abu Bakr, who came to power in 632 C.E., introduced a guaranteed minimum standard of income, granting each man, woman and child ten dirhams annually. This was later increased to twenty dirhams.[7][better source needed]

Modern proposals

In 1795, American revolutionary Thomas Paine advocated a citizen's dividend to all United States citizens as compensation for "loss of his or her natural inheritance, by the introduction of the system of landed property" (Agrarian Justice, 1795).

French Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte echoed Paine's sentiments and commented that 'man is entitled by birthright to a share of the Earth's produce sufficient to fill the needs of his existence' (Herold, 1955).

The American economist Henry George advocated for a dividend paid to all citizens from the revenue generated by a land value tax.[8]

American economist Milton Friedman began advocating a basic income in the form of a negative income tax in the early 1940’s. He discusses the proposal his 1962 book Capitalism and Freedom and his 1980 book Free to Choose.[9][10]

In 1963, Robert Theobald published the book Free Men and Free Markets, in which he advocated a guaranteed minimum income (the origin of the modern version of the phrase).

In 1966, the Cloward–Piven strategy advocated "overloading" the US welfare system to force its collapse in the hopes that it would be replaced by "a guaranteed annual income and thus an end to poverty".

In his final book Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community? (1967), Martin Luther King Jr. wrote[11]

I am now convinced that the simplest approach will prove to be the most effective—the solution to poverty is to abolish it directly by a now widely discussed measure: the guaranteed income.

— from the chapter titled "Where We Are Going"

In 1968, James Tobin, Paul Samuelson, John Kenneth Galbraith and another 1,200 economists signed a document calling for the US Congress to introduce in that year a system of income guarantees and supplements.[12]

In 1969, President Richard Nixon's Family Assistance Plan would have paid a minimum income to poor families. The proposal by Nixon passed in the House but never made it out of committee in the Senate.[citation needed]

In 1973, Daniel Patrick Moynihan wrote The Politics of a Guaranteed Income, in which he advocated the guaranteed minimum income and discussed Richard Nixon's Guaranteed Annual Income (GAI) proposal.[13]

In 1987, New Zealand's Labour Finance Minister Roger Douglas announced a Guaranteed Minimum Family Income Scheme to accompany a new flat tax. Both were quashed by then Prime Minister David Lange, who sacked Douglas.[14]

In his 1994 "autobiographical dialog", classical liberal Friedrich Hayek stated: "I have always said that I am in favor of a minimum income for every person in the country".[15]

In 2013, the Equal Life Foundation published the Living Income Guaranteed Proposal,[16] illustrating a practical way to implement and fund a minimum guaranteed income.[17]

In 2017, Harry A. Shamir (US) published the book Consumerism, or Capitalism Without Crises, in which the concept was promoted by another label, as a way to enable our civilization to survive in an era of automation and computerization and large scale unemployment. The book also innovates a method to fund the process, tapping into the underground economy and volunteerism.

Other modern advocates include Ayşe Buğra (Turkey), The Green Economics Institute (GEI),[18] and Andrew Coyne (Canada).[19]

Funding

This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2013) |

Tax revenues would fund the majority of GMI proposals. As most GMI proposals seek to create an earnings floor close to or above poverty lines amongst all citizens, the fiscal burden would require equally broad tax sources, such as income taxes or VATs. To varying degrees, a GMI might be funded through the reduction or elimination of other social security programs, such as unemployment insurance.

Another approach for funding is to acknowledge that all modern economies use fiat money and thus taxation is not necessary for funding. However, the fact that there are no financial constraints does not mean other constraints, such as on real resources, do not exist. A likely outcome based on the economic theory known as Modern Monetary Theory would be a moderate increase in taxation to ensure the extra income would not cause demand-pull inflation. This hypothetical Chartalist approach can be seen in the implementation of quantitative easing programs where, in the United States, over three trillion dollars[20][21] were created without requiring taxes.

Examples around the world

Brazil

Minimum income has been increasingly accepted by the Brazilian government. In 2004, President Lula da Silva signed into law a bill to establish a universal basic income.[22] This law is primarily implemented through the Bolsa Família program. Under this program, poorer families receive a direct cash payment via a government issued debit card. Bolsa Família is a conditional cash transfer program, meaning that beneficiaries receive their aid if they accomplish certain actions. Families who receive the aid must put their children in school and participate in vaccination programs. If they do not meet these requirements, they are cut off from aid.[23] The program has been criticised as vote-buying, trading productive individuals' earning for the votes of welfare recipients[24] As of 2011, approximately 50 million people, or a quarter of Brazil's population, were participating in Bolsa Família.[25]

Canada

Canada has experimented with minimum income trials. During the Mincome experiment in Manitoba in the 1970s, Mincome provided lower-income families with cash transfers to keep them out of poverty.[26] The trial was eventually ended but this was due to budget shortfalls and a change in government.

The province of Ontario began a minimum income experiment in 2017. Approximately 4000 citizens began to receive a stipend based on their family situation and income.[27] Recipients of this program could receive upwards of $10,000 per year. Government researchers used this pilot as a way of testing to see if a minimum income can help people meet their basic needs.[28] On 31 August 2018, following a change in government, incoming Premier Doug Ford announced that the pilot would be cancelled at the end of the current fiscal year.

China

China's Minimum Livelihood Guarantee also called dibao, is a means-tested social assistance scheme introduced in 1993 and expanded to all Chinese cities in 1999.[29][30][31]

Cyprus

In July 2013, the Cypriot government unveiled a plan to reform the welfare system in Cyprus and create a 'Guaranteed Minimum Income' for all citizens.[32]

Denmark

Kontanthjælp (formerly known as bistandshjælp) is a public benefit in Denmark granted to citizens who would otherwise not be able to support themselves or their families. In principle, cash benefits are a universal right for all citizens who meet certain statutory criteria.

Estonia

A subsistence allowance is financial help for a person or family in need, which provides minimal resources for everyday life (food, medicine, housing costs, etc.).

Finland

Basic subsistence allowance paid by Kela may be granted to a person or family whose income and assets are insufficient to cover the necessary daily expenses.

France

In 1988, France was one of the first countries to implement a minimum income, called the Revenu minimum d'insertion. In 2009, it was turned into Revenu de solidarité active (RSA), a new system that aimed to solve the poverty trap by providing low-wage workers a complementary income to encourage activity.

Iceland

Financial assistance (fjárhagsaðstoð) is for individuals and families who cannot support themselves and their livelihoods without assistance, with the aim of supporting people to help themselves and to be able to support themselves.[33]

India

Modern independent India developed many means and livelihood tested cash transfer programs through Direct Benefit Transfer at both the federal and the state level. At the federal level, these include minimum income social pension programs such as National Social Assistance Scheme, guaranteed employment program like National Rural Employment Guarantee Act, 2005 or a disability aid like Deendayal Disabled Rehabilitation Scheme. At the state level, there can be additional minimum income programs, one such being "Laksmir Bhandar" run by the state of West Bengal that transfers a minimum aid to families without work in the state.[34]

Ireland

In Ireland, €20 of earnings per day of permitted work (beneficiaries are allowed up to three days per week) is disregarded from employment income when calculating Jobseekers’ Allowance entitlement and deductions are calculated as 60 percent of earnings less this income disregard. In addition, the Part-time Job Incentive Scheme and Back to Work Family Dividend are fixed-duration payments offered to the long-term unemployed incentive moving into work. In return for relinquishing claims to primary assistance benefits, both schemes provide benefits for a fixed duration that are slightly lower than household GMI entitlements, but which are not tapered with employment income, subject to certain eligibility requirements. Ireland’s relatively generous tapering system serves to smooth disincentives to increase income and work and contributes to their lower measured participation tax rates (PTRs) and marginal effective tax rates (METRs).[35]

Italy

The citizens' income is a social welfare system created in Italy in January 2019.[36][37] Although its name recalls one of a universal basic income, this provision is actually a form of conditional and non-individual guaranteed minimum income.[38][39]

Netherlands

Norway

Income support can be granted if the applicant has insufficient income and resources to live on and is not entitled to other social security benefits. Income support is paid by the Norwegian Labour and Welfare Administration.

Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia has a Citizen’s Account Program which provides a basic income to registered citizens.[citation needed] In December 2017, immediately before the program began, more than 3.7 million households had registered, representing 13 million people, or more than half the population.[40]as of 2013, between one fifth and one third of Saudi residents are estimated to be non-citizens.[41][42][43][needs update]

Spain

In Spain, the ingreso mínimo vital is an economic benefit guaranteed by the Social security in Spain in its modality no contributory. The IMV is defined as a "subjective right" and is intended to prevent poverty and social exclusion of people who live alone or integrated into a coexistence unit when they are in a situation of vulnerability due to lack of sufficient financial resources to cover their basic needs.[44] The benefit, which is not fixed and varies depending on various factors, ranges between 462 and 1015 euros per month, is expected to cover 850,000 households (approximately 2.5 million people) and will cost the government 3 billion euros per year.[44][45]

Sweden

Social assistance consists partly of a "national standard" (riksnorm) and partly of "reasonable costs outside the national standard". The national standard includes costs such as food, clothing and footwear. Reasonable non-standard costs include rent and household electricity.

United States

No business which depends for existence on paying less than living wages to its workers has any right to continue in this country.

The United States has multiple social programs that provide guaranteed minimum incomes for individuals meeting certain criteria such as assets or disability. For instance, Supplemental Security Income (SSI) is a United States government program that provides stipends to low-income people who are either aged (65 or older), blind, or disabled. SSI was created in 1974 to replace federal-state adult assistance programs that served the same purpose. Today the program provides benefits to approximately eight million Americans. Another such program is Social Security Disability Insurance (SSD or SSDI), a payroll tax-funded, federal insurance program. It is managed by the Social Security Administration and is designed to provide income supplements to people who are restricted in their ability to work because of a disability, usually a physical disability. SSD can be supplied on either a temporary or permanent basis, usually directly correlated to whether the person's disability is temporary or permanent.

An early guaranteed minimum income program in the U.S. was the Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC), established by the Social Security Act. Where previously the responsibility to assist needy children lay in the hands of the states, AFDC transferred that authority to the federal government.[47] Over time, the AFDC was often criticized for creating disincentives to work, leading to many arguing for its replacement. In the 1970s, President Richard M. Nixon proposed the Family Assistance Program (FAP), which would replace the AFDC. FAP was intended to fix many of the problems of the AFDC, particularly the anti-work structure. Presidential nominee George McGovern also proposed a minimum income—in the form of a Universal Tax Credit. Ultimately, neither of these programs was implemented. Throughout the decade, many other experimental minimum income programs were carried out in cities throughout the country, such as the Seattle-Denver Income Maintenance Experiments.[48] In 1996, under President Bill Clinton, the AFDC was replaced with the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program. This would block grant funds to the states to allow them to decide how aid would be distributed.[47]

Another guaranteed minimum income program in the U.S. is the Earned Income Tax Credit. This is a refundable tax credit that gives poorer families cash assistance every year. The EITC avoids the welfare trap by subsidizing income, rather than replacing it.[49]

Other countries

- Romania [50]

See also

References

Deputy Prime Minister Pablo Iglesias told a news conference on Friday the creation of a minimum income worth €462 (£416.92) a month will target some 850,000 households or 2.5 million people. The government would pay the monthly stipend and top up existing revenue for people earning less so that they receive at least that minimum amount every month, he said. The minimum income would increase with the number of family members, up to a maximum of €1,015 (£916.30) each month. The programme would cost the government about €3 billion a year.

- "Venit minim garantat". May 2020.

Further reading

- Coady, D., Shang, B., Jahan, S., & Matsumoto, R. (2021). Guaranteed minimum income schemes in Europe: Landscape and design. IMF Working Papers, 2021(179), 1. https://doi.org/10.5089/9781513584379.001

- Colombino, U. (2011). Five issues in the design of Income support mechanisms: The case of Italy, IZA Discussion Papers 6059, Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA).

External links

- Basic income for all-Philipp van Parijs, Boston Review

- "Social minimum" in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Guaranteed Basic Income Studies: How it could be organised, Different Suggestions

- About a Guaranteed Basic Income: History

- "Guaranteed minimum income" in the Encyclopædia Britannica

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Guaranteed_minimum_income

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Guaranteed_minimum_income

| Part of a series on |

| Universalism |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Category |

Universal basic income (UBI)[note 1] is a social welfare proposal in which all citizens of a given population regularly receive a guaranteed income in the form of an unconditional transfer payment (i.e., without a means test or need to work).[2][3][4] It would be received independently of any other income. If the level is sufficient to meet a person's basic needs (i.e., at or above the poverty line), it is sometimes called a full basic income; if it is less than that amount, it may be called a partial basic income.[5] No country has yet introduced either, although there have been numerous pilot projects and the idea is discussed in many countries. Some have labelled UBI as utopian due to its historical origin.[clarification needed][6][7][8]

There are several welfare arrangements that can be considered similar to basic income, although they are not unconditional. Many countries have a system of child benefit, which is essentially a basic income for guardians of children. A pension may be a basic income for retired persons. There are also quasi-basic income programs that are limited to certain population groups or time periods, like Bolsa Familia in Brazil, which is concentrated on the poor, or the Thamarat Program in Sudan, which was introduced by the transitional government to ease the effects of the economic crisis inherited from the Bashir regime.[9] Likewise, the economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic prompted some countries to send direct payments to its citizens. The Alaska Permanent Fund is a fund for all residents of the U.S. state of Alaska which averages $1,600 annually (in 2019 currency), and is sometimes described as the only example of a real basic income in practice. A negative income tax (NIT) can be viewed as a basic income for certain income groups in which citizens receive less and less money until this effect is reversed the more a person earns.[10]

Critics claim that a basic income at an appropriate level for all citizens is not financially feasible, fear that the introduction of a basic income would lead to fewer people working, and/or consider it socially unjust that everyone should receive the same amount of money regardless of their individual need. Proponents say it is indeed financeable, arguing that such a system, instead of many individual means-tested social benefits, would eliminate a lot of expensive social administration and bureaucratic efforts, and expect that unattractive jobs would have to be better paid and their working conditions improved because there would have to be an incentive to do them when already receiving an income, which would increase the willingness to work. Advocates also argue that a basic income is fair because it ensures that everyone has a sufficient financial basis to build on and less financial pressure, thus allowing people to find work that suits their interests and strengths.[11]

Early historical examples of unconditional payments date back to antiquity, and the first proposals to introduce a regular unconditionally paid income for all citizens were developed and disseminated between the 16th and 18th centuries. After the Industrial Revolution, public awareness and support for the concept increased. At least since the mid-20th century, basic income has repeatedly been the subject of political debates. In the 21st century, several discussions are related to the debate about basic income, including those regarding automation, artificial intelligence (AI), and the future of the necessity of work. A key issue in these debates is whether automation and AI will significantly reduce the number of available jobs and whether a basic income could help prevent or alleviate such problems by allowing everyone to benefit from a society's wealth, as well as whether a UBI could be a stepping stone to a resource-based or post-scarcity economy.

History

Antiquity

In a 46 BC triumph, Roman general and dictator Julius Caesar gave each common Roman citizen 100 denarii. Following his assassination in 44 BC, Caesar's will left 300 sestertii (or 75 denarii) to each citizen.[12]

Trajan, emperor of Rome from 98–117 AD, personally gave 650 denarii (equivalent to perhaps US$430 in 2023) to all common Roman citizens who applied.[13]

16th to 18th century

In his Utopia (1516), English statesman and philosopher Thomas More depicts a society in which every person receives a guaranteed income.[14] In this book, basic income is proposed as an answer to the statement "No penalty on earth will stop people from stealing, if it's their only way of getting food", stating:[15]

instead of inflicting these horrible punishments, it would be far more to the point to provide everyone with some means of livelihood, so that nobody's under the frightful necessity of becoming first a thief, and then a corpse.

Spanish scholar Johannes Ludovicus Vives (1492–1540) proposed that the municipal government should be responsible for securing a subsistence minimum to all its residents "not on the grounds of justice but for the sake of a more effective exercise of morally required charity." Vives also argued that to qualify for poor relief, the recipient must "deserve the help he or she gets by proving his or her willingness to work."[16] In the late 18th century, English Radical Thomas Spence and English-born American philosopher Thomas Paine both had ideas in the same direction.

Paine authored Common Sense (1776) and The American Crisis (1776–1783), the two most influential pamphlets at the start of the American Revolution. He is also the author of Agrarian Justice, published in 1797. In it, he proposed concrete reforms to abolish poverty. In particular, he proposed a universal social insurance system comprising old-age pensions and disability support, and universal stakeholder grants for young adults, funded by a 10% inheritance tax focused on land.

Early 20th century

Around 1920, support for basic income started growing, primarily in England.

Bertrand Russell (1872–1970) argued for a new social model that combined the advantages of socialism and anarchism, and that basic income should be a vital component in that new society.

Dennis and Mabel Milner, a Quaker married couple of the Labour Party, published a short pamphlet entitled "Scheme for a State Bonus" (1918) that argued for the "introduction of an income paid unconditionally on a weekly basis to all citizens of the United Kingdom." They considered it a moral right for everyone to have the means to subsistence, and thus it should not be conditional on work or willingness to work.

C. H. Douglas was an engineer who became concerned that most British citizens could not afford to buy the goods that were produced, despite the rising productivity in British industry. His solution to this paradox was a new social system he called social credit, a combination of monetary reform and basic income.

In 1944 and 1945, the Beveridge Committee, led by the British economist William Beveridge, developed a proposal for a comprehensive new welfare system of social insurance, means-tested benefits, and unconditional allowances for children. Committee member Lady Rhys-Williams argued that the incomes for adults should be more like a basic income. She was also the first to develop the negative income tax model.[17][18] Her son Brandon Rhys Williams proposed a basic income to a parliamentary committee in 1982, and soon after that in 1984, the Basic Income Research Group, now the Citizen's Basic Income Trust, began to conduct and disseminate research on basic income.[19]

Late 20th century

In his 1964 State of the Union address, U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson introduced legislation to fight the "war on poverty". Johnson believed in expanding the federal government's roles in education and health care as poverty reduction strategies. In this political climate, the idea of a guaranteed income for every American also took root. Notably, a document, signed by 1200 economists, called for a guaranteed income for every American. Six ambitious basic income experiments started up on the related concept of negative income tax. Succeeding President Richard Nixon explained its purpose as "to provide both a safety net for the poor and a financial incentive for welfare recipients to work."[20] Congress eventually approved a guaranteed minimum income for the elderly and the disabled.[20]

In the mid-1970s the main competitor to basic income and negative income tax, the Earned income tax credit (EITC), or its advocates, won over enough legislators for the US Congress to pass laws on that policy. In 1986, the Basic Income European Network, later renamed to Basic Income Earth Network (BIEN), was founded, with academic conferences every second year.[21] Other advocates included the green political movement, as well as activists and some groups of unemployed people.[22]

In the latter part of the 20th century, discussions were held around automatization and jobless growth, the possibility of combining economic growth with ecologically sustainable development, and how to reform the welfare state bureaucracy. Basic income was interwoven in these and many other debates. During the BIEN academic conferences, there were papers about basic income from a wide variety of perspectives, including economics, sociology, and human rights approaches.

21st century

In recent years the idea has come to the forefront more than before. The Swiss referendum about basic income in Switzerland 2016 was covered in media worldwide, despite its rejection.[23] Famous business people like Elon Musk,[24] Pierre Omidyar,[25] and Andrew Yang have lent their support, as have high-profile politicians like Jeremy Corbyn[26] and Tulsi Gabbard.[27]

In 2019, in California, then-Stockton Mayor Michael Tubbs initiated an 18-month pilot program of guaranteed income for 125 residents as part of the privately-funded S.E.E.D. project there.[28]

In the 2020 Democratic Party primaries, political newcomer Andrew Yang touted basic income as his core policy. His policy, referred to as a "Freedom Dividend", would have provided adult American citizens US$1,000 a month independent of employment status.[29]

On 21 January 2021, in California, the two-year donor-funded Compton Pledge[28] began distributing monthly guaranteed income payments to a "pre-verified" pool of low-income residents,[28] in a program gauged for a maximum of 800 recipients, at which point it will be one of the larger among 25 U.S. cities exploring this approach to community economics.

Beginning in December 2021, Tacoma, Washington, piloted "Growing Resilience in Tacoma" (GRIT), a guaranteed income initiative that provides $500 a month to 110 families. GRIT is part of the University of Pennsylvania's Center for Guaranteed Income Research larger study. A report on the results of the GRIT experiment will be published in 2024.[30]

Response to COVID-19

As a response to the COVID-19 pandemic and related economic impact, universal basic income and similar proposals such as helicopter money and cash transfers were increasingly discussed across the world.[31] Most countries implemented forms of partial unemployment schemes, which effectively subsidized workers' incomes without a work requirement. Around ninety countries and regions including the United States, Spain, Hong Kong, and Japan introduced temporary direct cash transfer programs to their citizens.[32][33]

In Europe, a petition calling for an "emergency basic income" gathered more than 200,000 signatures,[34] and polls suggested widespread support in public opinion for it.[35][36] Unlike the various stimulus packages of the US administration, the EU's stimulus plans did not include any form of income-support policies.[37]

Pope Francis has stated in response to the economic harm done to workers by the pandemic that "this may be the time to consider a universal basic wage".[38]

Basic income vs negative income tax

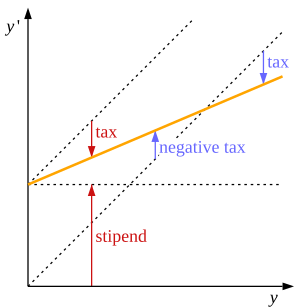

The diagram shows a basic income/negative tax system combined with flat income tax (the same percentage in tax for every income level).

Y is here the pre-tax salary given by the employer and y' is the net income.

Negative income tax

For low earnings, there is no income tax in the negative income tax system. They receive money, in the form of a negative income tax, but they don't pay any tax. Then, as their labour income increases, this benefit, this money from the state, gradually decreases. That decrease is to be seen as a mechanism for the poor, instead of the poor paying tax.

Basic income

That is, however, not the case in the corresponding basic income system in the diagram. There everyone typically pays income taxes. But on the other hand, everyone also gets the same amount of basic income.

But the net income is the same

But, as the orange line in the diagram shows, the net income is anyway the same. No matter how much or how little one earns, the amount of money one gets in one's pocket is the same, regardless of which of these two systems are used.

Basic income and negative income tax are generally seen to be similar in economic net effects, but there are some differences:

- Psychological. Philip Harvey accepts that "both systems would have the same redistributive effect and tax earned income at the same marginal rate" but does not agree that "the two systems would be perceived by taxpayers as costing the same".[39]: 15, 13

- Tax profile. Tony Atkinson made a distinction based on whether the tax profile was flat (for basic income) or variable (for NIT).[40]

- Timing. Philippe Van Parijs states that "the economic equivalence between the two programs should not hide the fact that they have different effects on recipients because of the different timing of payments: ex-ante in Basic Income, ex-post in Negative Income Tax".[41]

Perspectives and arguments

Automation

There is a prevailing opinion that we are in an era of technological unemployment – that technology is increasingly making skilled workers obsolete.

Prof. Mark MacCarthy (2014)[42]

One central rationale for basic income is the belief that automation and robotisation could result in technological unemployment, leading to a world with fewer paid jobs. A key question in this context is whether a basic income could help prevent or alleviate such problems by allowing everyone to benefit from a society's wealth, as well as whether a UBI could be a stepping stone to a resource-based or post-scarcity economy.[24][43][44][45]

U.S. presidential candidate and nonprofit founder Andrew Yang has stated that automation caused the loss of 4 million manufacturing jobs and advocated for a UBI (which he calls a Freedom Dividend) of $1,000/month rather than worker retraining programs.[46] Yang has stated that he is heavily influenced by Martin Ford. Ford, in his turn, believes that the emerging technologies will fail to deliver a lot of employment; on the contrary, because the new industries will "rarely, if ever, be highly labor-intensive".[47] Similar ideas have been debated many times before in history—that "the machines will take the jobs"—so the argument is not new. But what is quite new is the existence of several academic studies that do indeed forecast a future with substantially less employment, in the decades to come.[48][49][50] Additionally, President Barack Obama has stated that he believes that the growth of artificial intelligence will lead to an increased discussion around the idea of "unconditional free money for everyone".[51]

Economics and costs

Some proponents of UBI have argued that basic income could increase economic growth because it would sustain people while they invest in education to get higher-skilled and well-paid jobs.[52][53] However, there is also a discussion of basic income within the degrowth movement, which argues against economic growth.[54]

Advocates contend that the guaranteed financial security of a UBI will increase the population's willingness to take risks,[55] which would create a culture of inventiveness and strengthen the entrepreneurial spirit.[56]

The cost of a basic income is one of the biggest questions in the public debate as well as in the research and depends on many things. It first and foremost depends on the level of the basic income as such, and it also depends on many technical points regarding exactly how it is constructed.

While opponents claim that a basic income at an adequate level for all citizens cannot be financed, their supporters propose that it could indeed be financed, with some advocating a strong redistribution and restructuring of bureaucracy and administration for this purpose.[57]

According to the George Gibbs Chair in Political Economy and Senior Research Fellow at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University and nationally syndicated columnist[58][59] Veronique de Rugy's statements made in 2016, as of 2014, the annual cost of a UBI in the US would have been about $200 billion cheaper than the US system put in place at that date. By 2020, it would have been nearly a trillion dollars cheaper.[60]

American economist Karl Widerquist argues that simply multiplying the amount of the grant by the population would be a naive calculation, as this is the gross costs of UBI and does not take into account that UBI is a system where people pay taxes on a regular basis and receive the grant at the same time.[61]

According to Swiss economist Thomas Straubhaar, the concept of UBI is basically financeable without any problems. He describes it as "at its core, nothing more than a fundamental tax reform" that "bundles all social policy measures into a single instrument, the basic income paid out unconditionally."[62] He also considers a universal basic income to be socially just, arguing, although all citizens would receive the same amount in the form of the basic income at the beginning of the month, the rich would have lost significantly more money through taxes at the end of the month than they would have received through the basic income, while the opposite is the case for poorer people, similar to the concept of a negative income tax.[62]

Inflation of labor and rental costs

One of the most common arguments against UBI stems from the upward pressure on prices, in particular for labor and housing rents, which would likely cause inflation.[63] Public policy choices such as rent controls would likely affect the inflationary potential of universal basic income.[63]

Work

Many critics of basic income argue that people, in general, will work less, which in turn means less tax revenue and less money for the state and local governments.[64][65][66][67] Although it is difficult to know for sure what will happen if a whole country introduces basic income, there are nevertheless some studies who have attempted to look at this question:

- In negative income tax experiments in the United States in 1970 there was a five percent decline in the hours worked. The work reduction was largest for second earners in two-earner households and weakest for primary earners. The reduction in hours was higher when the benefit was higher.[65]

- In the Mincome experiment in rural Dauphin, Manitoba, also in the 1970s, there were slight reductions in hours worked during the experiment. However, the only two groups who worked significantly less were new mothers, and teenagers working to support their families. New mothers spent this time with their infant children, and working teenagers put significant additional time into their schooling.[68]

- A study from 2017 showed no evidence that people worked less because of the Iranian subsidy reform (a basic income reform).[69]

Regarding the question of basic income vs jobs, there is also the aspect of so-called welfare traps. Proponents of basic income often argue that with a basic income, unattractive jobs would necessarily have to be better paid and their working conditions improved, so that people still do them without need, reducing these traps.[70]

Philosophy and morality

By definition, universal basic income does not make a distinction between "deserving" and "undeserving" individuals when making payments. Opponents argue that this lack of discrimination is unfair: "Those who genuinely choose idleness or unproductive activities cannot expect those who have committed to doing productive work to subsidize their livelihood. Responsibility is central to fairness."[71]

Proponents usually view UBI as a fundamental human right that enables an adequate standard of living which every citizen should have access to in modern society.[72] It would be a kind of foundation guaranteed for everyone, on which one could build and never fall below that subsistence level.

It is also argued that this lack of discrimination between those who supposedly deserve it and those who don't is a way to reduce social stigma.[71]

In addition, proponents of UBI may argue that the "deserving" and "undeserving" categories are a superficial classification, as people who are not in regular gainful employment also contribute to society, e.g. by raising children, caring for people, or doing other value-creating activities which are not institutionalized. UBI would provide a balance here and thus overcomes a concept of work that is reduced to pure gainful employment and disregards sideline activities too much.[73]

Health and poverty

The first comprehensive systematic review of the health impact of basic income (or rather unconditional cash transfers in general) in low- and middle-income countries, a study that included 21 studies of which 16 were randomized controlled trials, found a clinically meaningful reduction in the likelihood of being sick by an estimated 27%. Unconditional cash transfers, according to the study, may also improve food security and dietary diversity. Children in recipient families are also more likely to attend school and the cash transfers may increase money spent on health care.[74] A 2022 update of this landmark review confirmed these findings based on a grown body of evidence (35 studies, the majority being large randomized controlled trials) and additionally found sufficient evidence that unconditional cash transfers also reduce the likelihood of living in extreme poverty.[75]

The Canadian Medical Association passed a motion in 2015 in clear support of basic income and for basic income trials in Canada.[76]

Advocates

Pilot programs and experiments

Since the 1960s, but in particular, since the late 2000s, several pilot programs and experiments on basic income have been conducted. Some examples include:

1960s−1970s

- Experiments with negative income tax in the United States and Canada in the 1960s and 1970s.

- The province of Manitoba, Canada experimented with Mincome, a basic guaranteed income, in the 1970s. In the town of Dauphin, Manitoba, labor only decreased by 13%, much less than expected.[77][78]

2000−2009

- The basic income grant in Namibia launched in 2008 and ended in 2009.[79]

- An independent pilot implemented in São Paulo, Brazil launched in 2009.[80]

2010−2019

- Basic income trials run in 2011-2012 in several villages in India,[81] whose government has proposed a guaranteed basic income for all citizens.[82] It was found that basic income in the region raised the education rate of young people by 25%.[83]

- Iran introduced a national basic income program in the autumn of 2010. It is paid to all citizens and replaces the gasoline subsidies, electricity, and some food products,[84] that the country applied for years to reduce inequalities and poverty. The sum corresponded in 2012 to approximately US$40 per person per month, US$480 per year for a single person, and US$2,300 for a family of five people.[85][86]

- In Spain, the ingreso mínimo vital, the income guarantee system, is an economic benefit guaranteed by the social security in Spain, but in 2016 was considered in need of reform.[87]

- In South Korea the Youth Allowance Program was started in 2016 in the City of Seongnam, which would give every 24-year-old citizen 250,000 won (~215 USD) every quarter in the form of a "local currency" that could only be used in local businesses. This program was later expanded to the entire Province of Gyeonggi in 2018.[88][89]

- The GiveDirectly experiment in a disadvantaged village of Nairobi, Kenya, benefitting over 20,000 people living in rural Kenya, is the longest-running basic income pilot as of November 2017, which is set to run for 12 years.[90][91][92]

- A project called Eight in a village in Fort Portal, Uganda, that a nonprofit organization launched in January 2017, which provides income for 56 adults and 88 children through mobile money.[93]

- A two-year pilot the Finnish government began in January 2017 which involved 2,000 subjects[94][95] In April 2018, the Finnish government rejected a request for funds to extend and expand the program from Kela (Finland's social security agency).[96]

- An experiment in the city of Utrecht, Netherlands launched in early 2017, that is testing different rates of aid.[82]

- A three-year basic income pilot that the Ontario provincial government, Canada, launched in the cities of Hamilton, Thunder Bay and Lindsay in July 2017.[97] Although called basic income, it was only made available to those with a low income and funding would be removed if they obtained employment,[98] making it more related to the current welfare system than true basic income. The pilot project was canceled on 31 July 2018 by the newly elected Progressive Conservative government under Ontario Premier Doug Ford.

- In Israel, in 2018 a non-profit initiative GoodDollar started with an objective to build a global economic framework for providing universal, sustainable, and scalable basic income through the new digital asset technology of blockchain. The non-profit aims to launch a peer-to-peer money transfer network in which money can be distributed to those most in need, regardless of their location, based on the principles of UBI. The project raised US$1 million from a financial company.[99][100]

- The Rythu Bandhu scheme is a welfare scheme started in the state of Telangana, India, in May 2018, aimed at helping farmers. Each farm owner receives 4,000 INR per acre twice a year for rabi and kharif harvests. To finance the program a budget allocation of 120 billion INR (US$1.55 Billion as of May 2022) was made in the 2018–2019 state budget.[101]

2020−present

- Swiss non-profit Social Income started paying out basic incomes in the form of mobile money in 2020 to people in need in Sierra Leone. Contributions finance the international initiative from people worldwide, who donate 1% of their monthly paychecks.[102]

- In May 2020, Spain introduced a minimum basic income, reaching about 2% of the population, in response to COVID-19 in order to "fight a spike in poverty due to the coronavirus pandemic". It is expected to cost state coffers three billion euros ($3.5 billion) a year."[103]

- In August 2020, a project in Germany started that gives a 1,200 Euros monthly basic income in a lottery system to citizens who applied online. The crowdsourced project will last three years and be compared against 1,380 people who do not receive basic income.[104]

- In October 2020, HudsonUP[105] was launched in Hudson, New York, by The Spark of Hudson[106] and Humanity Forward Foundation[107] to give $500 monthly basic income to 25 residents. It will last five years and be compared against 50 people who are not receiving basic income.

- In May 2021, the government of Wales, which has devolved powers in matters of Social Welfare within the UK, announced the trialling of a universal basic income scheme to "see whether the promises that basic income holds out are genuinely delivered".[108] From July 2022 over 500 people leaving care in Wales were offered £1600 per month in a 3-year £20 million pilot scheme, to evaluate the effect on the lives of those involved in the hope of providing independence and security to people.[109]

- In July 2022, Chicago began a year-long guaranteed income program by sending $500 to 5,000 households for one year in a lottery system to citizens who applied online.[110] A similar program was launched in late 2022 by Cook County, Illinois (which encompasses the entirety of Chicago as well as several suburbs) which sent monthly $500 payments to 3,250 residents with a household income at or below 250% of the federal poverty level for two years.[111]

Payments with similarities

Alaska Permanent Fund

The Permanent Fund of Alaska in the United States provides a kind of yearly basic income based on the oil and gas revenues of the state to nearly all state residents. More precisely the fund resembles a sovereign wealth fund, investing resource revenues into bonds, stocks, and other conservative investment options with the intent to generate renewable revenue for future generations. The fund has had a noticeable yet diminishing effect on reducing poverty among rural Alaska Indigenous people, notably in the elderly population.[112] However, the payment is not high enough to cover basic expenses, averaging $1,600 annually per resident in 2019 currency[113] (it has never exceeded $2,100), and is not a fixed, guaranteed amount. For these reasons, it is not always considered a basic income. However, some consider it to be the only example of a real basic income.[114][115]

Wealth Partaking Scheme

Macau's Wealth Partaking Scheme provides some annual basic income to permanent residents, funded by revenues from the city's casinos. However, the amount disbursed is not sufficient to cover basic living expenses, so it is not considered a basic income.[116]

Bolsa Família

Bolsa Família is a large social welfare program in Brazil that provides money to many low-income families in the country. The system is related to basic income, but has more conditions, like asking the recipients to keep their children in school until graduation. As of March 2020, the program covers 13.8 million families, and pays an average of $34 per month, in a country where the minimum wage is $190 per month.[117]

Other welfare programs

- Pension: A payment that in some countries is guaranteed to all citizens above a certain age. The difference from true basic income is that it is restricted to people over a certain age.

- Child benefit: A program similar to pensions but restricted to parents of children, usually allocated based on the number of children.

- Conditional cash transfer: A regular payment given to families, but only to the poor. It is usually dependent on basic conditions such as sending their children to school or having them vaccinated. Programs include Bolsa Família in Brazil and Programa Prospera in Mexico.

- Guaranteed minimum income differs from a basic income in that it is restricted to those in search of work and possibly other restrictions, such as savings being below a certain level. Example programs are unemployment benefits in the UK, the revenu de solidarité active in France, and citizens' income in Italy.

Petitions, polls and referendums

- 2008: An official petition for basic income was launched in Germany by Susanne Wiest.[118] The petition was accepted, and Susanne Wiest was invited for a hearing at the German parliament's Commission of Petitions. After the hearing, the petition was closed as "unrealizable".[119]

- 2013–2014: A European Citizens' Initiative collected 280,000 signatures demanding that the European Commission study the concept of an unconditional basic income.[120]

- 2015: A citizen's initiative in Spain received 185,000 signatures, short of the required number to mandate that the Spanish parliament discuss the proposal.[121]

- 2016: The world's first universal basic income referendum in Switzerland on 5 June 2016 was rejected with a 76.9% majority.[122][123] Also in 2016, a poll showed that 58% of the EU's population is aware of basic income, and 64% would vote in favour of the idea.[124]

- 2017: Politico/Morning Consult asked 1,994 Americans about their opinions on several political issues including national basic income; 43% either "strongly supported" or "somewhat supported" the idea.[125]

- 2018: The results of a poll by Gallup conducted last year between September and October were published. 48% of respondents supported universal basic income.[126]

- 2019: In November, an Austrian initiative received approximately 70,000 signatures but failed to reach the 100,000 signatures needed for a parliamentary discussion. The initiative was started by Peter Hofer. His proposal suggested a basic income sourced from a financial transaction tax, of €1,200, for every Austrian citizen.[127]

- 2020: A study by Oxford University found that 71% of Europeans are now in favour of basic income. The study was conducted in March, with 12,000 respondents and in 27 EU-member states and the UK.[128] A YouGov poll likewise found a majority for universal basic income in United Kingdom[129] and a poll by University of Chicago found that 51% of Americans aged 18–36 support a monthly basic income of $1,000.[130] In the UK there was also a letter, signed by over 170 MPs and Lords from multiple political parties, calling on the government to introduce a universal basic income during the COVID-19 pandemic.[131]

- 2020: A Pew Research Center survey, conducted online in August 2020, of 11,000 U.S. adults found that a majority (54%) oppose the federal government providing a guaranteed income of $1,000 per month to all adults, while 45% support it.[132]

- 2020: In a poll by Hill-HarrisX, 55% of Americans voted in favour of UBI in August, up from 49% in September 2019 and 43% in February 2019.[133]

- 2020: The results of an online survey of 2,031 participants conducted in 2018 in Germany were published: 51% were either "very much in favor" or "in favor" of UBI being introduced.[134]

- 2021: A Change.org petition calling for monthly stimulus checks in the amount of $2,000 per adult and $1,000 per child for the remainder of the COVID-19 pandemic had received almost 3 million signatures.[135]

See also

- Citizen's dividend

- Economic, social and cultural rights

- Equality of outcome

- Estovers

- FairTax § monthly tax rebate

- Geolibertarianism

- Global basic income

- Happiness economics

- Humanistic economics

- Involuntary unemployment

- Job guarantee

- Left-libertarianism

- Limitarianism (ethical)

- Living wage

- Moral universalism

- New Cuban economy

- Old Age Security

- Participation income

- Post-work society

- Quatinga Velho

- Rationing

- Social safety net

- Speenhamland system

- The Triple Revolution

- Universal Credit

- Universal value

- Universalism

- Wage subsidy

- Welfare capitalism

- Workfare

- Working time

References

...in order to pay for meaningful retraining, if retraining works. My plan is to just give everyone $1,000 a month, and then have the economy geared more to serve human goals and needs.

[See graphs] The annual check this year will be delivered to 631,000 Alaskans, most of the state population, and come largely from earnings of the state's $64 billion fund that for decades has been seeded with income from oil-production revenue. ... This year's dividend amount, similar to last year's, is in line with the average annual payment since they began at $1,000 in 1982 when inflation is taken into account, said Mouhcine Guettabi, an economist with the University of Alaska Anchorage Institute of Social and Economic Research.

Family allowance - Brazil is renowned for its massive, nearly 2-decade-old cash-transfer program for the poor, Bolsa Família (often translated as "family allowance"). As of March, it reached 13.8 million families, paying an average of $34 per month. (The national minimum wage is about $190 per month.)

- Shalvey, Kevin (4 July 2021). "Stimulus-check petitions calling for the 4th round of $2,000 monthly payments gain almost 3 million signatures". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 4 July 2021. Retrieved 4 July 2021.

Notes

- Also variously known as unconditional basic income, citizen's basic income, basic income guarantee, basic living stipend, guaranteed annual income,[1] universal income security program, or universal demogrant

Further reading

- Ailsa McKay, The Future of Social Security Policy: Women, Work and a Citizens Basic Income, Routledge, 2005, ISBN 9781134287185.

- Benjamin M. Friedman, "Born to Be Free" (review of Philippe Van Parijs and Yannick Vanderborght, Basic Income: A Radical Proposal for a Free Society and a Sane Economy, Harvard University Press, 2017), The New York Review of Books, vol. LXIV, no. 15 (12 October 2017), pp. 39–41.

- Bryce Covert, "What Money Can Buy: The promise of a universal basic income – and its limitations", The Nation, vol. 307, no. 6 (10 / 17 September 2018), pp. 33–35.

- Colombino, U. (2015). "Five Crossroads on the Way to Basic Income: An Italian Tour" (PDF). Italian Economic Journal. 1 (3): 353–389. doi:10.1007/s40797-015-0018-3. S2CID 26507450. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 December 2022. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- Ewan McGaughey, 'Will Robots Automate Your Job Away? Full Employment, Basic Income, and Economic Democracy Archived 24 May 2018 at the Wayback Machine' (2018) SSRN Archived 24 May 2018 at the Wayback Machine, part 4(2).

- John Lanchester, "Good New Idea: John Lanchester makes the case for Universal Basic Income" (discusses 8 books, published between 2014 and 2019, comprehensively advocating Universal Basic Income), London Review of Books, vol. 41, no. 14 (18 July 2019), pp. 5–8.

- Karl Widerquist, ed., Exploring the Basic Income Guarantee Archived 23 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine, (book series), Palgrave Macmillan.

- Karl Widerquist, Independence, Propertylessness, and Basic Income: A Theory of Freedom as the Power to Say No Archived 16 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine, New York, Palgrave Macmillan, March 2013. Early drafts of each chapter are available online for free at this link Archived 13 June 2017 at the Wayback Machine.

- Karl Widerquist, Jose Noguera, Yannick Vanderborght, and Jurgen De Wispelaere (editors). Basic Income: An Anthology of Contemporary Research Archived 14 September 2019 at the Wayback Machine, Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2013.

- Lowrey, Annie (2018). Give People Money: How a Universal Basic Income Would End Poverty, Revolutionize Work, and Remake the World. Crown. ISBN 978-1524758769.

- Marinescu, Ioana (February 2018). "No Strings Attached: The Behavioral Effects of U.S. Unconditional Cash Transfer Programs". NBER Working Paper No. 24337. doi:10.3386/w24337.

- Paul O'Brien, Universal Basic Income: Pennies from Heaven, The History Press, 2017, ISBN 978 1 84588 367 6.

External links

- Basic Income Earth Network

- Basic Income India

- Basic Income Lab (BIL)

- Citizen’s Basic Income Trust

- Red Humanista por la Renta Básica Universal (in Spanish)

- Unconditional Basic Income Europe

- v:Should universal basic income be established?

- Universal basic income

- Egalitarianism

- Grants (money)

- Income distribution

- Labor relations

- Market socialism

- Philanthropy

- Political sociology

- Political theories

- Government aid programs

- Public policy proposals

- Social programs

- Social security

- Universalism

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Universal_basic_income

In economics, a cycle of poverty or poverty trap is caused by self-reinforcing mechanisms that cause poverty, once it exists, to persist unless there is outside intervention.[1] It can persist across generations, and when applied to developing countries, is also known as a development trap.[2]

Families trapped in the cycle of poverty have few to no resources. There are many self-reinforcing disadvantages that make it virtually impossible for individuals to break the cycle.[3] This occurs when poor people do not have the resources necessary to escape poverty, such as financial capital, education, or connections. Impoverished individuals do not have access to economic and social resources as a result of their poverty. This lack may increase their poverty. This could mean that the poor remain poor throughout their lives.[2]

Controversial educational psychologist Ruby K. Payne, author of A Framework for Understanding Poverty, distinguishes between situational poverty, which can generally be traced to a specific incident within the lifetimes of the person or family members in poverty, and generational poverty, which is a cycle that passes from generation to generation, and goes on to argue that generational poverty has its own distinct culture and belief patterns.[4]

Measures of social mobility examine how frequently poor people become wealthier, and how often children are wealthier or achieve higher income than their parents.

Causes of the cycle

Economic factors

According to the United States Census, in 2012 people aged 18–64 living in poverty in the country gave the reason they did not work, by category:[5]

- 31% - Ill or disabled

- 26% - Home or family reasons

- 21% - School or other

- 13% - Cannot find work

- 8% - Retired early

Some activities can also cost poor people more than wealthier people. For example, if unable to afford the first month's rent and security deposit for a typical apartment lease, people sometimes must live in a hotel or motel at a higher daily rate. If unable to afford an apartment with a refrigerator, kitchen, and stove, people may need to spend more on prepared meals than if they could cook for themselves and store leftovers.[6]

In the case of banking, people who cannot maintain a minimum daily balance in a savings account are often charged fees by the bank, whereas people with larger amounts of wealth can earn interest on savings and substantial returns from investments. Unbanked people must use higher-cost alternative financial services, such as check-cashing services for payroll and money orders for transferring to other people. People who have had previous credit problems, such as overdrafting an account, may not be eligible to open a checking or savings account. Major reasons for not opening a bank account include not trusting banks, being concerned about not making a payment due to a bank error or delay, not understanding how banks work, and not having enough money to qualify for a free account.[7]

Though most industrialized countries have free universal health care, in the United States and many developing countries, people with little savings often postpone expensive medical treatment as long as possible. This can cause a relatively small medical condition to become a serious condition that costs more to treat, and possibly causing lost wages due to missed hourly work. (Though poor people may have lower overall personal medical expenses simply because illnesses and medical conditions go untreated, and on average life span is shorter.) Higher-income workers typically have medical insurance which prevents them from experiencing excessive costs and often provides free preventive care for example. In addition to personal savings they can use, higher-income workers are also more likely to be salaried and get sick time that prevents them from losing wages while seeking treatment. Because no skills or experience are required, some people in poverty make money by volunteering for medical studies or donating blood plasma.[8]

Internal and external factors sustaining poverty

Amongst the most popular characterizations of the ongoing experience of poverty are that:

- it is systemic or institutionalized or

- a person is misguided by emotional challenges driven by historical experiences or

- a person is affected by a mental disability,

or a combination of all three reasons (Bertrand, Mullainathan, & Shafir, 2004[9]).

Systemic factors

Donald Curtis (2006),[10] a researcher at the School of Public Policy in the United Kingdom, identified that governments regard the welfare system as an enabling task. Curtis (2006)[10] maintained, however, that the system lacks cohesiveness, and is not designed to be an empowerment tool.

For example, outside parties are funded to manage the effort without much oversight creating a disconnected system, for which no one leads (Curtis, 2006).[10] The result is mismanagement of budget without forwarding progress, and those that remain in the poverty loophole are accused of draining the system (Curtis, 2006).[10]

Bias

Jill Suttie (2018),[11] wrote that implicit bias, which can be transferred nonverbally to children with no more than a look or a gesture, and as such is a learned behavior. Critical thinking skills can ward off implicit bias, but without education and practice, habitual thoughts can cloud judgment and poorly affect future decisions.

Decision-making

A Dartmouth College (2016)[12] study reported that probabilistic decision-making follows prior-based knowledge of failure in similar situations. Rather than choose success, people respond as if the failure has already taken place. Those who have experienced intergenerational poverty are most susceptible to this kind of learned behavior (Wagmiller & Adelman, 2009).[13]

Intergenerational

Professors of Sociology Wagmiller and Adelman (2009)[13] asserted that roughly 35–46% of people who have experienced hardship in young and middle adulthood also experienced moderate to severe poverty in childhood. As of 2018, 7.5 million people experienced poverty in California alone (Downs, 2018).[14]

Mental illness

In a qualitative study, Rudnick et al., (2014),[15] studied people living in poverty with mental illness and determined that participants felt that wellness care, nutrition, housing, and jobs were severely lacking. Respondents asserted that the most significant problem was access to quality services; bureaucratic systems appear to be devoid of logic and treatment by providers were often unaccommodating and uncooperative (Rudnick et al., 2014).[15]

Lowered productivity

The stress of worrying about one's personal finances can cause lower productivity. One study on factory workers in India found payment earlier in the work period increased average worker output by 6.2%.[16]

Choices and culture

According to the Brookings Institution, people who finish high school, get a full-time job, and wait until age 21 to marry and have children end up with a poverty rate of only 2%, whereas people who follow none of the steps end up with a poverty rate of 76%.[17][18]

Early childhood adversity and basic needs stressors contributing to the cycle of generational poverty

- The stress of early childhood adversities, including basic need stressors and, at times, abuse and neglect are major causes of generational poverty. Studies have shown that the trauma of child abuse manifests negatively in adult life in overall health and even in employment status.[19] Abuse and neglect are potential adversities facing those in poverty, the adversity that is shared among all below the poverty line is the daily stress over basic needs. "The stress of meeting basic needs takes all precedent in the family, and children learn that the only way to survive is to focus on getting basic needs met".[20] Every member of a household in poverty lives the struggle of basic needs stressors and is impacted by it. The ability to secure and pay for childcare is another contributing factor to the problems those in poverty have with finding and keeping a job.[21] These stressors are not just unpleasant, they are catastrophic to a body's health and development. Exposure to chronic stress can induce changes in the architecture of different regions of the developing brain (e.g., amygdala, hippocampus), which can impact a range of important functions, such as regulating the stress response, attention, memory, planning, and learning new skills, and also contribute to dysregulation of inflammatory response systems that can lead to a chronic "wear and tear" effect on multiple organ systems.[19] Chronic stress is detrimental to our health and has even been proven to harm memory and organs, including the brain. Working memory, defined as a human's capacity to store information in the brain for immediate use, is known to be shorter for children raised in poverty versus those raised in even a middle-class environment.[22] Children suffering through basic needs stressors from the earliest of years have to work harder than their peers to learn and absorb information.

Family background

A 2002 research paper titled "The Changing Effect of Family Background on the Incomes of American Adults" analyzed changes in the determinants of family income between 1961 and 1999, focusing on the effect of parental education, occupational rank, income, marital status, family size, region of residence, race, and ethnicity. The paper (1) outlines a simple framework for thinking about how family background affects children's family and income, (2) summarizes previous research on trends in intergenerational inheritance in the United States, (3) describes the data used as a basis for the research which it describes, (4) discusses trends in inequality among parents, (5) describes how the effects of parental inequality changed between 1961 and 1999, (6) contrasts effects at the top and bottom of the distribution, and (7) discusses whether intergenerational correlations of zero would be desirable. The paper concludes by posing the question of whether reducing the intergenerational correlation is an efficient strategy for reducing poverty or inequality.

Because improving the skills of disadvantaged children seems relatively easy, it is an attractive strategy. However, judging by American experience since the 1960s, improving the skills of disadvantaged children has proved difficult. As a result, the paper suggests, there are probably cheaper and easier ways to reduce poverty and inequality, such as supplementing the wages of the poor or changing immigration policy so that it drives down the relative wages of skilled rather than unskilled workers. These alternative strategies would not reduce intergenerational correlations, but they would reduce the economic gap between children who started life with all the disadvantages instead of all the advantages.[23]

Another paper, titled Do poor children become poor adults?, which was originally presented at a 2004 symposium on the future of children from disadvantaged families in France, and was later included in a 2006 collection of papers related to the theme of the dynamics of inequality and poverty, discusses generational income mobility in North America and Europe. The paper opens by observing that in the United States almost one half of children born to low income parents become low income adults, four in ten in the United Kingdom, and one-third in Canada. The paper goes on to observe that rich children also tend to become rich adults—four in ten in the U.S. and the U.K., and as many as one-third in Canada. The paper argues, however, that money is not the only or even the most important factor influencing intergenerational income mobility. The rewards to higher skilled and/or higher educated individuals in the labor market and the opportunities for children to obtain the required skills and credentials are two important factors.[clarification needed] Conclusions that income transfers to lower income individuals may be important to children but they should not be counted on to strongly promote generational mobility. The paper recommends that governments focus on investments in children to ensure that they have the skills and opportunities to succeed in the labor market, and observes that though this has historically meant promoting access to higher and higher levels of education, it is becoming increasingly important that attention be paid to preschool and early childhood education.[24]

Lack of jobs due to deindustrialization

Sociologist William Julius Wilson has said that the economic restructuring of changes from manufacturing to a service-based economy has led to a high percentage of joblessness in the inner-cities and with it a loss of skills and an inability to find jobs. This "mismatch" of skills to jobs available is said to be the main driver of poverty.[citation needed]

Effects of modern education

Research shows that schools with students who perform lower than the norm are also those hiring least-qualified teachers as a result of new teachers generally working in the area that they grew up in. This leads to certain schools not producing many students who enter tertiary education. Graduates who previously attended these schools are not as skilled as they would be if they had gone to a school with higher-qualified instructors. This leads to education perpetuating a cycle of poverty. People who choose to work in the schools close to them do not adequately supply the school with enough teachers. The schools must then outsource their teachers from other areas. Susanna Loeb from the School of Education at Stanford conducted a study and found that teachers who are brought in from the suburbs are 10 times more likely to transfer out of the school after their initial year. The fact that the teachers from the suburbs leave appears to be an influential factor for schools hiring more teachers from that area. The lack of adequate education for children is part of what allows for the cycle of poverty to continue.[25] The problem undergoing this is the lack of updating the knowledge of the staff. Schools have continued to conduct professional development the same way they have for decades.[26]

Culture of poverty

Another theory for the perpetual cycle of poverty is that poor people have their own culture with a different set of values and beliefs that keep them trapped within that cycle from generation to generation. This theory has been explored by Ruby K. Payne in her book A Framework for Understanding Poverty. In this book she explains how a social class system in the United States exists, where there is a wealthy upper class, a middle class, and the working poor class. These classes each have their own set of rules and values, which differ from each other. To understand the culture of poverty, Payne describes how these rules affect the poor and tend to keep them trapped in this continual cycle. Time is treated differently by the poor; they generally do not plan ahead but simply live in the moment, which keeps them from saving money that could help their children escape poverty.

Payne emphasizes how important it is when working with the poor to understand their unique cultural differences so that one does not get frustrated but instead tries to work with them on their ideologies and help them to understand how they can help themselves and their children escape the cycle. One aspect of generational poverty is a learned helplessness that is passed from parents to children; a mentality that there is no way for one to get out of poverty and so in order to make the best of the situation one must enjoy what one can when one can. This leads to such habits as spending money immediately, often on unnecessary goods such as alcohol and cigarettes, thus teaching their children to do the same and trapping them in poverty. Another important point Payne makes is that leaving poverty is not as simple as acquiring money and moving into a higher class but also includes giving up certain relationships in exchange for achievement. A student's peers can have an influence on the child's level of achievement. Coming from a low-income household a child could be teased or expected to fall short academically. This can cause a student to feel discouraged and hold back when it comes to getting involved more with their education because they are scared to be teased if they fail. This helps to explain why the culture of poverty tends to endure from generation to generation as most of the relationships the poor have are within that class.[27]

The "culture of poverty" theory has been debated and critiqued by many people including Eleanor Burke Leacock (and others) in her book The Culture of Poverty: A Critique.[28] Leacock claims that people who use the term, "culture of poverty" only "contribute to the distorted characterizations of the poor." In addition, Michael Hannan in an essay[29] argues that the "culture of poverty" is "essentially untestable." This is due to many things including the highly subjective nature of poverty and issues concerning the universal act of classifying only some impoverished people as trapped in the culture.

Life shocks

2004 research in New Zealand[30][31] produced a report that showed that "life shocks" can be endured only to a limited extent, after which people are much more likely to be tipped into hardship. The researchers found very little differences in living standards for people who have endured up to 7 negative events in their lifetime. People who had 8 or more life shocks were dramatically more likely to live in poverty than those who had 0 to 7 life shocks. A few of the life shocks studied were:

- Marriage (or similar) break-ups (divorce)

- Forced sale of house

- Unexpected and substantial drop in income

- Eviction

- Bankruptcy

- Substantial financial loss

- Redundancy (being laid off from a job)

- Becoming a single parent

- 3 months or more unemployed

- Major damage to home

- House burgled

- Victim of violence

- Incarceration

- A non-custodial sentence (community service, or fines, but not imprisonment)

- Illness lasting three weeks or more

- Major injury or health problem

- Unplanned pregnancy and birth of a child

The study focused on just a few possible life shocks, but many others are likely as traumatic or more so. Chronic PTSD, complex PTSD, and depression sufferers could have innumerable causes for their mental illness, including those studied above. The study is subject to some criticism.[32]

Tracking in education

History in the United States has shown that Americans saw education as the way to end the perpetual cycle of poverty. In the present, children from low to middle income households are at a disadvantage. They are twice as likely to be held back and more likely not to graduate from high school. Recent studies have shown that the cause for the disparity among academic achievement results from the school's structure where some students succeed from an added advantage and others fail as a result of lacking that advantage. Educational institutions with a learning disparity are causing education to be a sustaining factor for the cycle of poverty. One prominent example of this type of school structures is tracking, which is predominantly used to help organize a classroom so the variability of academic ability in classes is decreased. Students are tracked based on their ability level, generally based on a standardized test after which they are given different course requirements. Some people[who?] believe that tracking "enhances academic achievement and improves the self-concept of students by permitting them to progress at their own pace."[33]