- Social inclusion, action taken to support people of different backgrounds sharing life together.

- Inclusion (disability rights), promotion of people with disabilities sharing various aspects of life and life as a whole with those without disabilities.

- Inclusion (education), to do with students with special educational needs spending most or all of their time with non-disabled students

Science and technology

- Inclusion (mineral), any material that is trapped inside a mineral during its formation

- Inclusion bodies, aggregates of stainable substances in biological cells

- Inclusion (cell), insoluble non-living substance suspended in a cell's cytoplasm

- Inclusion (taxonomy), combining of biological species

- Include directive, in computer programming

Mathematics

- Inclusion (set theory), or subset

- Inclusion (Boolean algebra), the Boolean analogue to the subset relation

- Inclusion map, or inclusion function, or canonical injection

- Inclusion (logic), the concept that all the contents of one object are also contained within a second object

Other uses

- Clusivity, a linguistic concept

- Include (horse), a racehorse

- Inclusion by reference, legal documentation process

- Centre for Economic and Social Inclusion, a former British think-tank known as Inclusion

See also

- Inclusive (disambiguation)

- Transclusion, the inclusion of part or all of an electronic document into one or more other documents by hypertext reference

- Inclusion–exclusion principle, in combinatorics

- All pages with titles beginning with Inclusion

- All pages with titles beginning with Include

If an internal link led you here, you may wish to change the link to point directly to the intended article.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Inclusion

Academic tenure in the United States and Canada is a contractual right that grants a teacher or professor a permanent position of employment at an academic institution such as a university or school.[1] Tenure is intended to protect teachers from dismissal without just cause, and to allow development of thoughts or ideas considered unpopular or controversial among the community. In North America, tenure is granted only to educators whose work is considered to be exceptionally productive and beneficial in their careers.[2][3]

Academic tenure became a standard for education institutions in North America with the introduction of the American Association of University Professors (AAUP)'s 1940 Statement of Principles on Academic Freedom and Tenure. In this statement, the AAUP provides a definition of academic tenure: "a means to certain ends, specifically: (1) freedom of teaching and research and of extramural activities, and (2) a sufficient degree of economic security to make the profession attractive to men and women of ability."[4]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Academic_tenure_in_North_America

Gentrification is the process of changing the character of a neighborhood through the influx of more affluent residents and businesses.[1] It is a common and controversial topic in urban politics and planning. Gentrification often increases the economic value of a neighborhood, but the resulting demographic displacement may itself become a major social issue. Gentrification often sees a shift in a neighborhood's racial or ethnic composition and average household income as housing and businesses become more expensive and resources that had not been previously accessible are extended and improved.[2][3][4]

The gentrification process is typically the result of increasing attraction to an area by people with higher incomes spilling over from neighboring cities, towns, or neighborhoods. Further steps are increased investments in a community and the related infrastructure by real estate development businesses, local government, or community activists and resulting economic development, increased attraction of business, and lower crime rates. In addition to these potential benefits, gentrification can lead to population migration and displacement. In extreme cases, gentrification can be brought on by a prosperity bomb.[5] However, some view the fear of displacement, which dominates the debate about gentrification, as hindering discussion about genuine progressive approaches to distribute the benefits of urban redevelopment strategies.[6]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gentrification

Inclusionary zoning (IZ), also known as inclusionary housing, refers to municipal and county planning ordinances that require a given share of new construction to be affordable by people with low to moderate incomes. The term inclusionary zoning indicates that these ordinances seek to counter exclusionary zoning practices, which aim to exclude low-cost housing from a municipality through the zoning code. There are variations among different inclusionary zoning programs. Firstly, they can be mandatory or voluntary.[1] Though voluntary programs exist, the great majority has been built as a result of local mandatory programmes requiring developers to include the affordable units in their developments.[2] There are also variations among the set-aside requirements, affordability levels coupled with the period of control.[1] In order to encourage engagements in these zoning programs, developers are awarded with incentives for engaging in these programs, such as density bonus, expedited approval and fee waivers.[1]

In practice, these policies involve placing deed restrictions on 10–30% of new houses or apartments in order to make the cost of the housing affordable to lower-income households. The mix of "affordable housing" and "market-rate" housing in the same neighborhood is seen as beneficial by city planners and sociologists.[3] Inclusionary zoning is a tool for local municipalities in the United States to allegedly help provide a wider range of housing options than a free market provides on its own. Many economists consider the program as a price control on a percentage of units, which negatively impacts the supply of housing.[4]

Most inclusionary zoning is enacted at the municipal or county level; when imposed by the state, as in Massachusetts, it has been argued that such laws usurp local control. In such cases, developers can use inclusionary zoning to avoid certain aspects of local zoning laws.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Inclusionary_zoning

A minimum spanning tree (MST) or minimum weight spanning tree is a subset of the edges of a connected, edge-weighted undirected graph that connects all the vertices together, without any cycles and with the minimum possible total edge weight.[1] That is, it is a spanning tree whose sum of edge weights is as small as possible.[2] More generally, any edge-weighted undirected graph (not necessarily connected) has a minimum spanning forest, which is a union of the minimum spanning trees for its connected components.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Minimum_spanning_tree

In the theory of decision making, the analytic hierarchy process (AHP), also analytical hierarchy process,[1] is a structured technique for organizing and analyzing complex decisions, based on mathematics and psychology. It was developed by Thomas L. Saaty in the 1970s; Saaty partnered with Ernest Forman to develop Expert Choice software in 1983, and AHP has been extensively studied and refined since then. It represents an accurate approach to quantifying the weights of decision criteria. Individual experts’ experiences are utilized to estimate the relative magnitudes of factors through pair-wise comparisons. Each of the respondents compares the relative importance of each pair of items using a specially designed questionnaire.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Analytic_hierarchy_process

Multiple-criteria decision-making (MCDM) or multiple-criteria decision analysis (MCDA) is a sub-discipline of operations research that explicitly evaluates multiple conflicting criteria in decision making (both in daily life and in settings such as business, government and medicine). Conflicting criteria are typical in evaluating options: cost or price is usually one of the main criteria, and some measure of quality is typically another criterion, easily in conflict with the cost. In purchasing a car, cost, comfort, safety, and fuel economy may be some of the main criteria we consider – it is unusual that the cheapest car is the most comfortable and the safest one. In portfolio management, managers are interested in getting high returns while simultaneously reducing risks; however, the stocks that have the potential of bringing high returns typically carry high risk of losing money. In a service industry, customer satisfaction and the cost of providing service are fundamental conflicting criteria.

In their daily lives, people usually weigh multiple criteria implicitly and may be comfortable with the consequences of such decisions that are made based on only intuition.[1] On the other hand, when stakes are high, it is important to properly structure the problem and explicitly evaluate multiple criteria.[2] In making the decision of whether to build a nuclear power plant or not, and where to build it, there are not only very complex issues involving multiple criteria, but there are also multiple parties who are deeply affected by the consequences.

Structuring complex problems well and considering multiple criteria explicitly leads to more informed and better decisions. There have been important advances in this field since the start of the modern multiple-criteria decision-making discipline in the early 1960s. A variety of approaches and methods, many implemented by specialized decision-making software,[3][4] have been developed for their application in an array of disciplines, ranging from politics and business to the environment and energy.[5]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Multiple-criteria_decision_analysis

Industrial engineering is an engineering profession that is concerned with the optimization of complex processes, systems, or organizations by developing, improving and implementing integrated systems of people, money, knowledge, information and equipment. Industrial engineering is central to manufacturing operations.[1]

Industrial engineers use specialized knowledge and skills in the mathematical, physical and social sciences, together with the principles and methods of engineering analysis and design, to specify, predict, and evaluate the results obtained from systems and processes.[2] There are several industrial engineering principles followed in the manufacturing industry to ensure the effective flow of the systems, processes and operations.[1] This includes Lean Manufacturing, Six Sigma, Information Systems, Process Capability and Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve and Control (DMAIC). These principles allow the creation of new systems, processes or situations for the useful coordination of labor, materials and machines and also improve the quality and productivity of systems, physical or social.[3][4] Depending on the subspecialties involved, industrial engineering may also overlap with, operations research, systems engineering, manufacturing engineering, production engineering, supply chain engineering, management science, management engineering, financial engineering, ergonomics or human factors engineering, safety engineering, logistics engineering or others, depending on the viewpoint or motives of the user.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Industrial_engineering

A machine is a physical system using power to apply forces and control movement to perform an action. The term is commonly applied to artificial devices, such as those employing engines or motors, but also to natural biological macromolecules, such as molecular machines. Machines can be driven by animals and people, by natural forces such as wind and water, and by chemical, thermal, or electrical power, and include a system of mechanisms that shape the actuator input to achieve a specific application of output forces and movement. They can also include computers and sensors that monitor performance and plan movement, often called mechanical systems.

Renaissance natural philosophers identified six simple machines which were the elementary devices that put a load into motion, and calculated the ratio of output force to input force, known today as mechanical advantage.[1]

Modern machines are complex systems that consist of structural elements, mechanisms and control components and include interfaces for convenient use. Examples include: a wide range of vehicles, such as trains, automobiles, boats and airplanes; appliances in the home and office, including computers, building air handling and water handling systems; as well as farm machinery, machine tools and factory automation systems and robots.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Machine

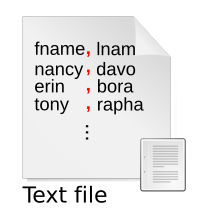

A delimiter is a sequence of one or more characters for specifying the boundary between separate, independent regions in plain text, mathematical expressions or other data streams.[1][2] An example of a delimiter is the comma character, which acts as a field delimiter in a sequence of comma-separated values. Another example of a delimiter is the time gap used to separate letters and words in the transmission of Morse code.

In mathematics, delimiters are often used to specify the scope of an operation, and can occur both as isolated symbols (e.g., colon in "

Delimiters represent one of various means of specifying boundaries in a data stream. Declarative notation, for example, is an alternate method that uses a length field at the start of a data stream to specify the number of characters that the data stream contains.[3]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Delimiter

An excursion is a trip by a group of people, usually made for leisure, education, or physical purposes. It is often an adjunct to a longer journey or visit to a place, sometimes for other (typically work-related) purposes.

Public transportation companies issue reduced price excursion tickets to attract business of this type. Often these tickets are restricted to off-peak days or times for the destination concerned.

Short excursions for education or for observations of natural phenomena are called field trips. One-day educational field studies are often made by classes as extracurricular exercises, e.g. to visit a natural or geographical feature.

The term is also used for short military movements into foreign territory, without a formal announcement of war.[1]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Excursion

Mass gatherings are events attended by a sufficient number of people to strain the planning and response resources of the host community, state/province, nation, or region where it is being held.[1][2] Definitions of a mass gathering generally include the following:

- Planned (long term or spontaneously planned) event

- “a specified number of persons (at least >1000 persons).

- at a specific location, for a specific purpose (e.g. social function, public event, sporting event) for a defined period of time”.

- Requires Multi-Agency Coordination[citation needed]

Mass gatherings are usually sporting events (such as Olympic Games) or religious pilgrimages (such as Kumbh Mela or Arba'een Pilgrimage). They are highly visible [3] and in some cases, millions of people attend them.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mass_gathering

A flash mob (or flashmob)[1] is a group of people who assemble suddenly in a public place, perform for a brief time, then quickly disperse, often for the purposes of entertainment, satire, and artistic expression.[2][3][4] Flash mobs may be organized via telecommunications, social media, or viral emails.[5][6][7][8][9]

The term, coined in 2003, is generally not applied to events and performances organized for the purposes of politics (such as protests), commercial advertisement, publicity stunts that involve public relation firms, or paid professionals.[7][10][11] In these cases of a planned purpose for the social activity in question, the term smart mobs is often applied instead.

The term "flash rob" or "flash mob robberies", a reference to the way flash mobs assemble, has been used to describe a number of robberies and assaults perpetrated suddenly by groups of teenage youth.[12][13][14] Bill Wasik, originator of the first flash mobs, and a number of other commentators have questioned or objected to the usage of "flash mob" to describe criminal acts.[14][15] Flash mob has also been featured in some Hollywood movie series, such as Step Up.[16]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Flash_mob

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Concise_Oxford_English_Dictionary

Mass psychogenic illness (MPI), also called mass sociogenic illness, mass psychogenic disorder, epidemic hysteria, involves the spread of illness symptoms through a population where there is no infectious agent responsible for contagion.[1] It is the rapid spread of illness signs and symptoms affecting members of a cohesive group, originating from a nervous system disturbance involving excitation, loss, or alteration of function, whereby physical complaints that are exhibited unconsciously have no corresponding organic causes that are known.[2]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mass_psychogenic_illness

https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Mass_hysteria&redirect=no

Oil agglomeration[1][2] is one of the special processes of mineral processing. It is based on differences in surface properties of desired and undesired minerals i.e., carbonaceous coal particles and gangue minerals. It is used for dressing, dehydration of finely dispersed naturally hydrophobic minerals – most often coal, in the first tests – for sulphide ores, in addition, adhesion minerals processing of gold and diamonds. The product of oil agglomeration of coal is carbonaceous agglomerate or granulate.

There are many factor which affect the oil agglomeration process such as coal ranks, moisture content, pulp density or solid concentration, oil dosage or oil concentration, particle size distribution, oil types, agglomeration time, conditioning time, concentration of salts, pH, vessel type, impeller design, number of baffles placed etc., which can be categorized into process variables and design variables.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oil_agglomeration

A clandestine operation is an intelligence or military operation carried out in such a way that the operation goes unnoticed by the general population or specific enemy forces.

Until the 1970s, clandestine operations were primarily political in nature, generally aimed at assisting groups or nations favored by the sponsor. Examples include U.S. intelligence involvement with German and Japanese war criminals after World War II. Today these operations are numerous and include technology-related clandestine operations.

The bulk of clandestine operations are related to the gathering of intelligence, typically by both people (clandestine human intelligence) and by hidden sensors. Placement of underwater or land-based communications cable taps, cameras, microphones, traffic sensors, monitors such as sniffers, and similar systems require that the mission go undetected and unsuspected. Clandestine sensors may also be on unmanned underwater vehicles, reconnaissance (spy) satellites (such as Misty), low-observability unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV), or unmanned detectors (as in Operation Igloo White and its successors), or hand-placed by clandestine human operations.

The United States Department of Defense Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms (Joint Publication JP 1-02, dated 8 November 2010, Amended Through 15 February 2016) defines "clandestine", "clandestine intelligence collection", and "clandestine operation" as[1]

clandestine — Any activity or operation sponsored or conducted by governmental departments or agencies with the intent to assure secrecy and concealment. (JP 2-01.2)

clandestine intelligence collection — The acquisition of protected intelligence information in a way designed to conceal the nature of the operation and protect the source. (JP 2-01.2)

clandestine operation — An operation sponsored or conducted by governmental departments or agencies in such a way as to assure secrecy or concealment. See also covert operation; overt operation. (JP 3-05)

The DOD Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms (January 2021) defines "clandestine" and "clandestine operation" the same way.[2]

The terms clandestine and covert are not synonymous. As noted in the definition (which has been used by the United States and NATO since World War II) in a covert operation the identity of the sponsor is concealed, while in a clandestine operation the operation itself is concealed. Put differently, clandestine means "hidden", where the aim is for the operation to not be noticed at all. Covert means "deniable", such that if the operation is noticed, it is not attributed to a group. The term stealth refers both to a broad set of tactics aimed at providing and preserving the element of surprise and reducing enemy resistance. It can also be used to describe a set of technologies (stealth technology) to aid in those tactics. While secrecy and stealthiness are often desired in clandestine and covert operations, the terms secret and stealthy are not used to formally describe types of missions. Some operations may have both clandestine and covert aspects, such as the use of concealed remote sensors or human observers to direct artillery attacks and airstrikes. The attack is obviously overt (coming under attack alerts the target that he has been located by the enemy), but the targeting component (the exact method that was used to locate targets) can remain clandestine.

In World War II, targets found through cryptanalysis of radio communication were attacked only if there had been aerial reconnaissance in the area, or, in the case of the shootdown of Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, where the sighting could be attributed to the Coastwatchers. During the Vietnam War, trucks attacked on the Ho Chi Minh trail were completely unaware of some sensors, such as the airborne Black Crow device that sensed their ignition. They could also have been spotted by a clandestine human patrol. Harassing and interdiction (H&I) or free-fire zone rules can also cause a target to be hit for purely random reasons.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Clandestine_operation

A covert operation or undercover operation is a military or police operation involving a covert agent or troops acting under an assumed cover to conceal the identity of the party responsible.[1] Some of the covert operations are also clandestine operations which are performed in secret and meant to stay secret, though many are not.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Covert_operation

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Don

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Background

A background actor or extra is a performer in a film, television show, stage, musical, opera, or ballet production who appears in a nonspeaking or nonsinging (silent) capacity, usually in the background (for example, in an audience or busy street scene). War films and epic films often employ background actors in large numbers: some films have featured hundreds or even thousands of paid background actors as cast members (hence the term "cast of thousands"). Likewise, grand opera can involve many background actors appearing in spectacular productions.[citation needed]

On a film or TV set, background actors are usually referred to as "junior artists", "atmosphere", "background talent", "background performers", "background artists", "background cast members", or simply "background",[1] while the term "extra" is rarely used.[citation needed] In a stage production, background actors are commonly referred to as "supernumeraries". In opera and ballet, they are called either "extras" or "supers".[citation needed]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Extra_(acting)

Casting is a manufacturing process in which a liquid material is usually poured into a mold, which contains a hollow cavity of the desired shape, and then allowed to solidify. The solidified part is also known as a casting, which is ejected or broken out of the mold to complete the process. Casting materials are usually metals or various time setting materials that cure after mixing two or more components together; examples are epoxy, concrete, plaster and clay. Casting is most often used for making complex shapes that would be otherwise difficult or uneconomical to make by other methods. Heavy equipment like machine tool beds, ships' propellers, etc. can be cast easily in the required size, rather than fabricating by joining several small pieces.[1] Casting is a 7,000-year-old process. The oldest surviving casting is a copper frog from 3200 BC.[2]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Casting

Casting is a manufacturing process using a fluid medium in a mould, so as to produce a casting. For casting metal, see casting (metalworking).

Casting may also refer to:

Creating a mold

- Casting, forming a protective orthopedic cast

- Casting, a process in sculpture of converting plastic materials into more solid form

Science and healthcare

- Casting (falconry), anything given to a hawk to purge and cleanse its gorge

- Casting, excretions from an earthworm

- Casting, moulting or shedding of hair in most breeds of dog and other mammals

- Casting, forming a protective orthopedic cast

Other uses

- Casting (fishing), the process of propelling a lure to catch fish

- Casting (performing arts), the process of selecting a cast of actors, or other visual talent such as models for a photo shoot

- Casting or footing, in bookkeeping, a method of summing a table of numbers by column

- Casting, to distribute a stream of data, images, sound, or voice, as in

- Screen mirroring:

- Casting, incantation of magical spells

- Casting, type conversion in computer programming

- Casting, propelling, as in casting off a boat or launching a rocket

See also

- Cast (disambiguation)

- Castang (disambiguation)

- Castaing, a surname

- Caster (disambiguation)

- Recast (disambiguation)

If an internal link led you here, you may wish to change the link to point directly to the intended article.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Casting_(disambiguation)

In the performing arts industry such as theatre, film, or television, casting, or a casting call, is a pre-production process for selecting a certain type of actor, dancer, singer, or extra for a particular role or part in a script, screenplay, or teleplay. This process may be used for a motion picture, television program, documentary film, music video, play, or advertisement, intended for an audience.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Casting_(performing_arts)

Storm Castle, el. 7,165 feet (2,184 m) is a mountain peak in the Gallatin Range in Gallatin County, Montana. The peak is located in the Gallatin National Forest. Storm Castle is also known as Castle Peak or Castle Mountain. The peak is a popular 5-mile (8.0 km) round trip hike from the Storm Castle trailhead in the Gallatin Canyon.[2]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Storm_Castle

| Gould's wattled bat[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Chiroptera |

| Family: | Vespertilionidae |

| Genus: | Chalinolobus |

| Species: | C. gouldii

|

| Binomial name | |

| Chalinolobus gouldii (Gray, 1841)

| |

| |

| Gould's wattled bat range | |

Gould's wattled bat (Chalinolobus gouldii) is a species of Australian wattled bat named after the English naturalist John Gould.[3]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gould%27s_wattled_bat

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/COVID-19

Americans are the citizens and nationals of the United States of America.[11][12] The United States is home to people of many racial and ethnic origins; consequently, American culture and law do not equate nationality with race or ethnicity, but with citizenship and an oath of permanent allegiance.[13][14][15][16]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Americans

Humans (Homo sapiens) are the most common and widespread species of primate. A great ape characterized by their bipedalism and high intelligence, humans' large brain and resulting cognitive skills have allowed them to thrive in a variety of environments and develop complex societies and civilizations. Humans are highly social and tend to live in complex social structures composed of many cooperating and competing groups, from families and kinship networks to political states. As such, social interactions between humans have established a wide variety of values, social norms, languages, and rituals, each of which bolsters human society. The desire to understand and influence phenomena has motivated humanity's development of science, technology, philosophy, mythology, religion, and other conceptual frameworks.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Human

A mammal (from Latin mamma 'breast')[1] is a vertebrate animal of the class Mammalia (/məˈmeɪli.ə/). Mammals are characterized by the presence of milk-producing mammary glands for feeding their young, a neocortex region of the brain, fur or hair, and three middle ear bones. These characteristics distinguish them from reptiles and birds, from which their ancestors diverged in the Carboniferous Period over 300 million years ago. Around 6,400 extant species of mammals have been described and divided into 29 orders.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mammal

Speciesism (/ˈspiːʃiːˌzɪzəm, -siːˌzɪz-/) is a term used in philosophy regarding the treatment of individuals of different species. The term has several different definitions within the relevant literature.[1] A common element of most definitions is that speciesism involves treating members of one species as morally more important than members of other species in the context of their similar interests.[2] Some sources specifically define speciesism as discrimination or unjustified treatment based on an individual's species membership,[3][4][5] while other sources define it as differential treatment without regard to whether the treatment is justified or not.[6][7] Richard Ryder, who coined the term, defined it as "a prejudice or attitude of bias in favour of the interests of members of one's own species and against those of members of other species."[8] Speciesism results in the belief that humans have the right to use non-human animals, which scholars say is pervasive in the modern society.[9][10][11] Studies increasingly suggest that people who support animal exploitation also tend to endorse racist, sexist, and other prejudicial views, which furthers the beliefs in human supremacy and group dominance to justify systems of inequality and oppression.[10][11][12][13][14]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Speciesism

Origin(s) or The Origin may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

Comics and manga

- Origin (comics), a Wolverine comic book mini-series published by Marvel Comics in 2002

- The Origin (Buffy comic), a 1999 Buffy the Vampire Slayer comic book series

- Origins (Judge Dredd story), a major Judge Dredd storyline running from 2006 through 2007

- Origin (manga), a 2016 manga by Boichi

- Mobile Suit Gundam: The Origin, a 2002 manga by Yoshikazu Yasuhiko

- Wolverine: Origins, a Marvel Comics series

Films and television

- Origin (TV series), 2018 science-fiction TV series

- "Origin" (Angel), a fifth-season episode of Angel

- Origin: Spirits of the Past, a 2006 anime movie also known as Gin-iro no Kami no Agito

- Origin (Stargate), the religion of the Ori

- "Origin" (Stargate SG-1), a ninth-season episode of Stargate SG-1

- X-Men Origins: Wolverine, a 2009 superhero film, prequel to the X-Men film trilogy

- Origins: The Journey of Humankind, a National Geographic TV series

- "The Origin" (Dark), episode 4 of season 3 of the Dark TV series

- The Origin (film), a 2022 British film

Gaming

- Origin (service), a video game digital distribution service and platform from Electronic Arts

- Origin Systems, a former video game developer

- Origin, King of the Summon Spirits in Tales of Phantasia and its prequel, Tales of Symphonia

- Origins, spirits that are attached to The Mystics in Legaia 2: Duel Saga

- Origins Award, presented by the Academy of Adventure Gaming Arts and Design at the Origins Game Fair

- Origins Game Fair, an annual board game event in Columbus, Ohio

- Assassin's Creed Origins, part of the Assassin's Creed franchise

- Batman: Arkham Origins, part of the Batman game franchise

- Dragon Age: Origins, a 2009 role-playing video game and first installment of the Dragon Age series

- F.E.A.R. 2: Project Origin, the sequel to F.E.A.R. by Monolith

- Rayman Origins, a 2011 installment in the Rayman series

- Silent Hill: Origins, the fifth installment of the Silent Hill survival horror series and prequel to the original 1999 game

- Origins, the final zombies map released for Call of Duty: Black Ops 2

- Origin, the final dungeon of Xenoblade Chronicles 3

Literature

Fiction

- Origin (Baxter novel), a 2001 science fiction book by Stephen Baxter

- Origin (Brown novel), a 2017 novel by Dan Brown, the fifth installment in the Robert Langdon series

- Origin, a 2007 novel by Diana Abu-Jaber

- Origins, a fantasy novel in the Fourth World series by Kate Thompson

- The Origin (novel), a biographical novel of Charles Darwin by Irving Stone

Nonfiction

- Origins (Cato), Cato the Elder's lost work on Roman and Italian history

- Origins, a book on evolution by Richard Leakey and Roger Lewin

Music

- The Origin (Einhorn), a 2009 opera/oratorio by Richard Einhorn

Groups

- Origin (band), an American metal band formed in 1997

- The Origin (band), an American rock and power pop band 1985–1992

- Origin, a jazz group led by Chick Corea

Albums

- Origin (Borknagar album), 2006

- Origin (Dayseeker album), 2015

- Origin (Evanescence album), 2000

- Origin (Origin album), 2000

- Origin, by Omnium Gatherum, 2021

- Origin, an EP by Kelly Moran, 2019

- The Origin (album), by The Origin, 1990

- Origins (Bridge to Grace album), 2015

- Origins (Eluveitie album), 2014

- Origins (God Is an Astronaut album), 2013

- Origins (Imagine Dragons album), 2018

- Origins (Dan Reed Network album) [de], by Dan Reed Network, 2018

- Origins, by Steve Roach, 1993

Songs

- "Origin", by Neurosis from their 2007 album Given to the Rising

Periodicals

- Origin (magazine), an American poetry magazine

- Origins, a theological journal published by Catholic News Service (CNS)

- Origins, a peer-reviewed creation science journal of the Geoscience Research Institute (GRI)

Brands and enterprises

- Atos Origin, a company formed by the merger of BSO and Philips C&P (Communications & Processing) division

- Origin Energy, an Australian gas and electricity company

- Origin Enterprises, Irish agribusiness multinational

- Origin PC, a personal computer manufacturer

- Origins (cosmetics), a plant-based skin care and fragrance company of Estée Lauder

- Toyota Origin, a limited edition Toyota automobile released in Japan

- Origin (3D printing), a San Francisco-based 3D printing company acquired by Stratasys

Philosophy and religion

- Creatio ex nihilo, Latin for "creation out of nothing", a phrase used in philosophical and theological contexts

- Creation myth, a symbolic account of how the world began and how people first came to inhabit it

- Origin myth, a story or explanation that describes the beginning of some feature of the natural or social world

- Origin story, or pourquoi story, a fictional narrative that explains why something is the way it is

- Origins, a theological journal published by Catholic News Service (CNS)

Science, technology and mathematics

Biology and medicine

- Origin (anatomy), the place or point at which a part or structure arises

- Abiogenesis, the study of how life on Earth arose from inanimate matter

- Noogenesis, the study of origin and evolution of mind

- Origin of humanity, the study of human evolution

- Origin of replication, the location at which DNA replication is initiated

- Paleoanthropology, the study of human origin

- Pedigree (dog), registered ancestry

Computing and technology

- Dalsa Origin, a digital movie camera

- Origin of a URI, as used in the Same-origin policy

- Origin (data analysis software), scientific graphing and data analysis software developed by OriginLab Corp

- Original equipment manufacturer (OEM), any company which manufactures products for another company's brand name

- SGI Origin 200, a series of entry-level MIPS-based server computers made by Silicon Graphics

- SGI Origin 2000, a series of mid-range to high-end MIPS-based server computers made by Silicon Graphics

- SGI Origin 3000, a series of mid-range to high-end MIPS-based server computers made by Silicon Graphics that succeeded the Origin 2000

Mathematics

- Origin (mathematics), a fixed point of reference for the geometry of the surrounding space

- Most commonly, the point of intersection of the axes in the Cartesian coordinate system

- Origin, the pole in the polar coordinate system

Time

- Origin, a general point in time

- Origin, an epochal date or event, see epoch

- Origin, in astronomy, an epochal moment, i.e., a reference for the orbital elements of a celestial body

Other

- Origin, in cosmogony, any theory concerning the origin of the universe

- Origin, in cosmology, the study of the universe and humanity's place in it

Sports

- City vs Country Origin, an annual Australian rugby league football match

- International Origin Match, England vs Exiles

- State of Origin series, annual best-of-three rugby league football match

Other uses

- Origin, or genealogy, the origin of families

- Origin, or etymology, the origin of words

- Origin, or toponymy, the origin of place names

See also

- Begin (disambiguation)

- Creation (disambiguation)

- Origen (disambiguation)

- Original (disambiguation)

- Point of origin (disambiguation)

- Source (disambiguation)

- Start (disambiguation)

- All pages with titles beginning with Origin

- All pages with titles containing Origin

If an internal link led you here, you may wish to change the link to point directly to the intended article.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Origin

Genesis may refer to:

Bible

- Book of Genesis, the first book of the biblical scriptures of both Judaism and Christianity, describing the creation of the Earth and of mankind

- Genesis creation narrative, the first several chapters of the Book of Genesis, which describes the origin of the Earth

- Genesis Rabbah, a midrash probably written between 300 and 500 CE with some later additions, comprising a collection of interpretations of the Book of Genesis

Literature and comics

- Genesis (DC Comics), a 1997 DC Comics crossover

- Genesis (Marvel Comics), a Marvel Comics supervillain

- Genesis, a fictional character in the comic book series Preacher

- Genesis, a 1951 story by H. Beam Piper

- Genesis: The Origins of Man and the Universe, a 1982 science text by John Gribbin

- Genesis, a 1988 epic poem by Frederick Turner

- Genesis, a 2000 story by Poul Anderson

- Genesis (novel), a 2006 work by Bernard Beckett

- Genesis, a 2007 story by Paul Chafe

- Genesis (journal), a scientific journal of biology

- Genesis (magazine), a pornographic magazine

- Genesis Publications, a British publishing company

- Genesis, a graphic novel by Nathan Edmondson

- The Book of Genesis (comics), comic-book adaptation illustrated by Robert Crumb

People

Given name

- Génesis Dávila (born 1990), Puerto Rican-American model and beauty pageant titleholder

- Génesis Franchesco (born 1990), Venezuelan female volleyball player

- Genesis Lynea (born 1989), Bermudian-British actress, singer, dancer, and model

- Genesis Potini (1963–2011), New Zealand speed chess player

- Genesis Rodriguez (born 1987), American actress

- Génesis Rodríguez (born 1994), Venezuelan female weightlifter

- Génesis Romero (born 1995), Venezuelan athlete

- Genesis Servania (born 1991), Filipino professional boxer

Surname

- Mercy Genesis (born 1997), Nigerian wrestler

Fictional characters

- Genesis Rhapsodos, main antagonist of the video game Crisis Core: Final Fantasy VII

Music

Artists

- Genesis (band), English rock band

- Génesis (band), Colombian folk rock band

- Genesis (1971–1974), original name for American rock/metal band Vixen

- Genesis P-Orridge (1950–2020), English musician and frontperson of Throbbing Gristle

- Genesis Drum and Bugle Corps, a drum and bugle corp from Austin, Texas

Albums

- Genesis (Busta Rhymes album)

- Genesis (Charles Sullivan album)

- Genesis, album by Coprofago

- Genesis (Diaura album)

- Genesis (Domo Genesis Album)

- Genesis (Elvin Jones album)

- Genesis (Genesis album)

- Genesis (The Gods album)

- Genesis, album by JJ Lin

- Genesis (Job for a Cowboy album)

- Genesis (Joy Williams album)

- Genesis, album by Larry Heard

- Génesis (Mary Ann Acevedo album)

- Genesis (Notaker EP)

- Genesis (Rotting Christ album)

- Genesis (S.H.E album)

- Genesis (Talisman album)

- Genesis, album by The-Dream

- Genesis (Woe, Is Me album)

- The Genesis, album by Yngwie Malmsteen

Songs

- "Genesis", by Ambrose Slade from Beginnings

- "Genesis", by Cult of Luna from The Beyond

- "Genesis", by Deftones from Ohms

- "Genesis", by Devin Townsend from Empath

- "Genesis", by Dua Lipa from Dua Lipa

- "Genesis", by Eir Aoi, from Aldnoah.Zero

- "Genesis", by Ghost, from Opus Eponymous

- "Genesis", by Glass Casket, from Desperate Man's Diary

- "Genesis" (Grimes song)

- "Genesis", by Jorma Kaukonen from Quah

- "Genesis", by Justice, from Cross

- "Génesis" (Lucecita Benítez song)

- "Génesis", by Mägo de Oz, from Jesús de Chamberí

- "Genesis" (Matthew Shell and Arun Shenoy song)

- "Genesis" (Michalis Hatzigiannis song)

- "Genesis" by Mumzy Stranger and Yasmin from Journey Begins

- "Genesis", by Northlane, from Singularity

- "Genesis", by Running Wild, from Black Hand Inn

- "Genesis", by The Ventures

- "Genesis" (VNV Nation song)

- "Génesis", by Vox Dei, from La Biblia

Technology

- Genesis, the time and date of the first block of a blockchain data structure

- GENESIS (software), GEneral NEural SImulation System

- Genesis Framework, a theme for the WordPress CMS

- Genesis LPMud, the first MUD of the LPMud family

- Norton 360, codenamed Project Genesis or simply Genesis

- X-COM: Genesis, a computer game

- Sega Genesis, a video game console

Television and film

Television

- "Genesis" (Arrow), episode of Arrow

- Genesis (TV series), Filipino television series

- "Genesis" (Heroes), pilot episode of Heroes

- "Genesis" (Quantum Leap episode)

- "Genesis" (Sliders), episode of Sliders

- "Genesis" (Survivors), episode of Survivors

- "Genesis" (Star Trek: The Next Generation), episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation

- Genesis II (film), science fiction TV movie created and produced by Gene Roddenberry

- Genesis Awards, television awards

- Genesis Entertainment, a News Corporation subsidiary

- Genesis Television Network, an American religious network

- TNA Genesis, a professional wrestling pay-per-view and television program

- Zoids: Genesis, fifth anime installment of the Zoids franchise

- Genesis (Air Gear), fictional Air Trek team in Air Gear

- Gênesis, Brazilian telenovela broadcast by RecordTV

Film

- Genesis (1986 film), an Indian film directed by Mrinal Sen Sen

- Genesis (1994 film), an Italian television film

- Genesis (1999 film), a Malian film

- Genesis (2004 film), a documentary

- Genesis (2018 Canadian film), a Canadian film

- Genesis (2018 Hungarian film), a Hungarian film

- [REC]³: Genesis, a 2012 Spanish horror film directed by Paco Plaza

- Project Genesis and the Genesis Planet, a fictional technology and the planet created by it in Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan and Star Trek III: The Search for Spock

Transportation

Vehicles

- Aviomania Genesis Duo G2SA, a Cypriot autogyro design

- Aviomania Genesis Solo G1SA, a Cypriot autogyro design

- Bertone Genesis, a concept truck

- GE Genesis, a locomotive

- Genesis (bikes), a British bicycle brand

- Genesis Motor, luxury vehicle division of Hyundai Motor Company Group.

- Genesis Transport, a bus company in the Philippines

- Oasis class cruise ship, a class of Royal Caribbean cruise ships, formerly known as Project Genesis

- SlipStream Genesis, kit aircraft

- Yamaha FZR600 Genesis, a motorcycle

Spacecraft

- Genesis (spacecraft), a NASA probe that collected solar samples

- Genesis I, a private spacecraft produced by Bigelow Aerospace

- Genesis II (space habitat), a follow-up to Genesis I

Companies

- Genesis, an American cryptocurrency brokerage

- Genesis Energy Limited, a New Zealand electricity generator and retailer

- Genesis HealthCare, a nursing home facility operator

- Genesis Microchip, a semiconductor company acquired by STMicroelectronics in 2007

Other uses

- Genesis (camera), a high-definition camera by Panavision

- Genesis Rock, a sample of lunar crust retrieved by Apollo 15 astronauts

- Sega Genesis, a 16-bit video game console also known as the Mega Drive

- Genesis (tournament), a Super Smash Bros. tournament in the San Francisco Bay Area

See also

- Terminator Genisys, a 2015 science fiction action film and fifth entry in the Terminator series

- Abiogenesis, the origin of life

- Biogenesis, the production of new living organisms

- Genesis Solar Energy Project, a solar power plant in California, United States

- Mass Effect Genesis, an interactive comic attached to the game Mass Effect 2

- Project Genesis (disambiguation)

- Genesys (disambiguation)

- Genisys (disambiguation)

- Gensis (disambiguation)

- Genesis (given name)

If an internal link led you here, you may wish to change the link to point directly to the intended article.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Genesis

In physical cosmology, the age of the universe is the time elapsed since the Big Bang. Astronomers have derived two different measurements of the age of the universe:[1] a measurement based on direct observations of an early state of the universe, which indicate an age of 13.787±0.020 billion years as interpreted with the Lambda-CDM concordance model as of 2021;[2] and a measurement based on the observations of the local, modern universe, which suggest a younger age.[3][4][5] The uncertainty of the first kind of measurement has been narrowed down to 20 million years, based on a number of studies that all show similar figures for the age and that includes studies of the microwave background radiation by the Planck spacecraft, the Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe and other space probes. Measurements of the cosmic background radiation give the cooling time of the universe since the Big Bang,[6] and measurements of the expansion rate of the universe can be used to calculate its approximate age by extrapolating backwards in time. The range of the estimate is also within the range of the estimate for the oldest observed star in the universe.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Age_of_the_universe

The age of Earth is estimated to be 4.54 ± 0.05 billion years (4.54 × 109 years ± 1%).[1][2][3][4] This age may represent the age of Earth's accretion, or core formation, or of the material from which Earth formed.[2] This dating is based on evidence from radiometric age-dating of meteorite[5] material and is consistent with the radiometric ages of the oldest-known terrestrial material[6] and lunar samples.[7]

Following the development of radiometric age-dating in the early 20th century, measurements of lead in uranium-rich minerals showed that some were in excess of a billion years old.[8] The oldest such minerals analyzed to date—small crystals of zircon from the Jack Hills of Western Australia—are at least 4.404 billion years old.[6][9][10] Calcium–aluminium-rich inclusions—the oldest known solid constituents within meteorites that are formed within the Solar System—are 4.567 billion years old,[11][12] giving a lower limit for the age of the Solar System.

It is hypothesised that the accretion of Earth began soon after the formation of the calcium-aluminium-rich inclusions and the meteorites. Because the time this accretion process took is not yet known, and predictions from different accretion models range from a few million up to about 100 million years, the difference between the age of Earth and of the oldest rocks is difficult to determine. It is also difficult to determine the exact age of the oldest rocks on Earth, exposed at the surface, as they are aggregates of minerals of possibly different ages.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Age_of_Earth

Development of modern geologic concepts

−4500 — – — – −4000 — – — – −3500 — – — – −3000 — – — – −2500 — – — – −2000 — – — – −1500 — – — – −1000 — – — – −500 — – — – 0 — |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Studies of strata—the layering of rocks and earth—gave naturalists an appreciation that Earth may have been through many changes during its existence. These layers often contained fossilized remains of unknown creatures, leading some to interpret a progression of organisms from layer to layer.[13][14]

Nicolas Steno in the 17th century was one of the first naturalists to appreciate the connection between fossil remains and strata.[14] His observations led him to formulate important stratigraphic concepts (i.e., the "law of superposition" and the "principle of original horizontality").[15] In the 1790s, William Smith hypothesized that if two layers of rock at widely differing locations contained similar fossils, then it was very plausible that the layers were the same age.[16] Smith's nephew and student, John Phillips, later calculated by such means that Earth was about 96 million years old.[17]

In the mid-18th century, the naturalist Mikhail Lomonosov suggested that Earth had been created separately from, and several hundred thousand years before, the rest of the universe[citation needed]. Lomonosov's ideas were mostly speculative[citation needed]. In 1779 the Comte du Buffon tried to obtain a value for the age of Earth using an experiment: He created a small globe that resembled Earth in composition and then measured its rate of cooling. This led him to estimate that Earth was about 75,000 years old.[18]

Other naturalists used these hypotheses to construct a history of Earth, though their timelines were inexact as they did not know how long it took to lay down stratigraphic layers.[15] In 1830, geologist Charles Lyell, developing ideas found in James Hutton's works, popularized the concept that the features of Earth were in perpetual change, eroding and reforming continuously, and the rate of this change was roughly constant. This was a challenge to the traditional view, which saw the history of Earth as dominated by intermittent catastrophes. Many naturalists were influenced by Lyell to become "uniformitarians" who believed that changes were constant and uniform.[citation needed]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Age_of_Earth

Mantle convection is the very slow creeping motion of Earth's solid silicate mantle as convection currents carry heat from the interior to the planet's surface.[1][2]

The Earth's surface lithosphere rides atop the asthenosphere and the two form the components of the upper mantle. The lithosphere is divided into a number of tectonic plates that are continuously being created or consumed at plate boundaries. Accretion occurs as mantle is added to the growing edges of a plate, associated with seafloor spreading. Upwelling beneath the spreading centers is a shallow, rising component of mantle convection and in most cases not directly linked to the global mantle upwelling. The hot material added at spreading centers cools down by conduction and convection of heat as it moves away from the spreading centers. At the consumption edges of the plate, the material has thermally contracted to become dense, and it sinks under its own weight in the process of subduction usually at an ocean trench. Subduction is the descending component of mantle convection.[3]

This subducted material sinks through the Earth's interior. Some subducted material appears to reach the lower mantle,[4] while in other regions, this material is impeded from sinking further, possibly due to a phase transition from spinel to silicate perovskite and magnesiowustite, an endothermic reaction.[5]

The subducted oceanic crust triggers volcanism, although the basic mechanisms are varied. Volcanism may occur due to processes that add buoyancy to partially melted mantle, which would cause upward flow of the partial melt due to decrease in its density. Secondary convection may cause surface volcanism as a consequence of intraplate extension[6] and mantle plumes.[7] In 1993 it was suggested that inhomogeneities in D" layer have some impact on mantle convection.[8]

Mantle convection causes tectonic plates to move around the Earth's surface.[9]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mantle_convection

A temperature gradient is a physical quantity that describes in which direction and at what rate the temperature changes the most rapidly around a particular location. The temperature gradient is a dimensional quantity expressed in units of degrees (on a particular temperature scale) per unit length. The SI unit is kelvin per meter (K/m).

Temperature gradients in the atmosphere are important in the atmospheric sciences (meteorology, climatology and related fields).

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Temperature_gradient

Radio is the technology of signaling and communicating using radio waves.[1][2][3] Radio waves are electromagnetic waves of frequency between 3 hertz (Hz) and 300 gigahertz (GHz). They are generated by an electronic device called a transmitter connected to an antenna which radiates the waves, and received by another antenna connected to a radio receiver. Radio is widely used in modern technology, in radio communication, radar, radio navigation, remote control, remote sensing, and other applications.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Radio

Psychoacoustics is the branch of psychophysics involving the scientific study of sound perception and audiology—how human auditory system perceives various sounds. More specifically, it is the branch of science studying the psychological responses associated with sound (including noise, speech, and music). Psychoacoustics is an interdisciplinary field of many areas, including psychology, acoustics, electronic engineering, physics, biology, physiology, and computer science.[1]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Psychoacoustics

Geopositioning, also known as geotracking, geolocalization, geolocating, geolocation, or geoposition fixing, is the process of determining or estimating the geographic position of an object.[1]

Geopositioning yields a set of geographic coordinates (such as latitude and longitude) in a given map datum; positions may also be expressed as a bearing and range from a known landmark. In turn, positions can determine a meaningful location, such as a street address.

Specific instances include: animal geotracking, the process of inferring the location of animals; positioning system, the mechanisms for the determination of geographic positions in general; internet geolocation, geolocating a device connected to the internet; and mobile phone tracking.[2]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Geopositioning

Cloning is the process of producing individual organisms with identical genomes, either by natural or artificial means. In nature, some organisms produce clones through asexual reproduction. In the field of biotechnology, cloning is the process of creating cloned organisms of cells and of DNA fragments.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cloning

Tracing may refer to:

Computer graphics

- Image tracing, digital image processing to convert raster graphics into vector graphics

- Path tracing, a method of rendering images of three-dimensional scenes such that the global illumination is faithful to reality

- Ray tracing (graphics), techniques in computer graphics

- Boundary tracing (also known as contour tracing), a segmentation technique that identifies the boundary pixels of the digital region

Software engineering

- Tracing (software), a method of debugging in computer programming

- System monitoring

- Application performance management

Physics

- Ray tracing (physics), a method for calculating the path of waves or particles

- Dye tracing, tracking various flows using dye added to the liquid in question

Other uses

- Tracing (art), copying an object or drawing, especially with the use of translucent tracing paper

- Tracing (criminology), determining crime scene activity from trace evidence left at crime scenes

- Tracing (law), a legal process by which a claimant demonstrates what has happened to their property

- Anterograde tracing, and Retrograde tracing, biological research techniques used to map the connections of neurons

- Call tracing, a procedure that permits an entitled user to be informed about the routing of data for an established connection

- Curve sketching, a process for determining the shape of a geometric curve

- Family Tracing and Reunification, a process whereby disaster response teams locate separated family members

- Tracking and tracing, a process of monitoring the location and status of property in transit

- Curve tracing, a method for analyzing the characteristics of semiconductors; see Semiconductor curve tracer

- Tracing (as with a gun or camera), tracking an object, as with the use of tracer ammunition

- Contact tracing, finding and identifying people in contact with someone with an infectious disease

See also

- All pages with titles containing Tracing

- Trace (disambiguation)

- Tracer (disambiguation)

- Tracking (disambiguation)

If an internal link led you here, you may wish to change the link to point directly to the intended article.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tracing

An error (from the Latin error, meaning "wandering")[1] is an action which is inaccurate or incorrect.[2] In some usages, an error is synonymous with a mistake. The etymology derives from the Latin term 'errare', meaning 'to stray'.

In statistics, "error" refers to the difference between the value which has been computed and the correct value.[3] An error could result in failure or in a deviation from the intended performance or behavior.[4]

Human behavior

One reference differentiates between "error" and "mistake" as follows:

An 'error' is a deviation from accuracy or correctness. A 'mistake' is an error caused by a fault: the fault being misjudgment, carelessness, or forgetfulness. Now, say that I run a stop sign because I was in a hurry, and wasn't concentrating, and the police stop me, that is a mistake. If, however, I try to park in an area with conflicting signs, and I get a ticket because I was incorrect on my interpretation of what the signs meant, that would be an error. The first time it would be an error. The second time it would be a mistake since I should have known better.[5]

In human behavior the norms or expectations for behavior or its consequences can be derived from the intention of the actor or from the expectations of other individuals or from a social grouping or from social norms. (See deviance.) Gaffes and faux pas can be labels for certain instances of this kind of error. More serious departures from social norms carry labels such as misbehavior and labels from the legal system, such as misdemeanor and crime. Departures from norms connected to religion can have other labels, such as sin.

An individual language user's deviations from standard language norms in grammar, pronunciation and orthography are sometimes referred to as errors. However, in light of the role of language usage in everyday social class distinctions, many feel that linguistics should restrain itself from such prescriptivist judgments to avoid reinforcing dominant class value claims about what linguistic forms should and should not be used. One may distinguish various kinds of linguistic errors[6] – some, such as aphasia or speech disorders, where the user is unable to say what they intend to, are generally considered errors, while cases where natural, intended speech is non-standard (as in vernacular dialects), are considered legitimate speech in scholarly linguistics, but might be considered errors in prescriptivist contexts. See also Error analysis (linguistics).

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Error

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Social_norm

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Acceptance

In law, acquiescence occurs when a person knowingly stands by, without raising any objection to, the infringement of their rights, while someone else unknowingly and without malice aforethought acts in a manner inconsistent with their rights.[1] As a result of acquiescence, the person whose rights are infringed may lose the ability to make a legal claim against the infringer, or may be unable to obtain an injunction against continued infringement. The doctrine infers a form of "permission" that results from silence or passiveness over an extended period of time.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Acquiescence

A silence procedure or tacit consent[1] or tacit acceptance procedure[2] (French: procédure d'approbation tacite; Latin: qui tacet consentire videtur, "he who is silent is taken to agree", "silence implies/means consent") is a way of formally adopting texts, often, but not exclusively in international political context.

A textbook on diplomacy describes the silence procedure thus:

... a proposal with strong support is deemed to have been agreed unless any member raises an objection to it before a precise deadline: silence signifies assent – or, at least, acquiescence. This procedure relies on a member in a minority fearing that raising an objection will expose it to the charge of obstructiveness and, thereby, the perils of isolation. Silence procedure is employed by NATO, the OSCE, in the framework of the Common Foreign and Security Policy of the European Union (EU) and, no doubt, in numerous other international bodies.[3]

In the context of international organisations, the subject of the procedure is often a joint statement or a procedural document, a formal vote on which with the members meeting in person is deemed unnecessary. Indeed, it is often impractical to try to stage a meeting between representatives of all member states either due to the limited importance of the text to be agreed upon or due to time constraints in the case of a joint declaration prompted by recent events. Organisations making extensive use of the procedure are, among others, the European Union, NATO and the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE).

A draft version of the text is circulated among participants who have a last opportunity to propose changes or amendments to the text. If no amendments are proposed (if no one 'breaks the silence') before the deadline of the procedure, the text is considered adopted by all participants. Often this procedure is the last step in adopting the text, after the basic premises of the text have been agreed upon in previous negotiations. 'Breaking the silence' is only a last resort in case a participant still has fundamental problems with parts of the text and is therefore the exception rather than the rule.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Silence_procedure

A code of silence is a condition in effect when a person opts to withhold what is believed to be vital or important information voluntarily or involuntarily.

The code of silence is usually followed because of threat of force or danger to oneself, or being branded as a traitor or an outcast within the unit or organization, as the experience of police whistleblower Frank Serpico illustrates. Police are known to have a well-developed blue wall of silence.

A more well-known example of the code of silence is omertà (Italian: omertà, from the Latin: humilitas=humility or modesty), the Mafia code of silence.

See also

- Blue wall of silence – Informal rule that American police do not report misconduct by other officers

- Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution

- Stop Snitchin'

- Spotlight, a 2015 film that explores a communal code of silence that reigned during the Boston sex abuse scandal

References

- Bill Maxwell, Opinion Columnist "Code of silence corrodes morality, puts blacks at risk" (2010, July 23)

- Board, Editorial. "Judgment day for Chicago's police code of silence". chicagotribune.com. Retrieved 2016-12-02.

This law enforcement–related article is a stub. You can help Wikipedia by expanding it. |

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Code_of_silence

To make an argument from silence (Latin: argumentum ex silentio) is to express a conclusion that is based on the absence of statements in historical documents, rather than their presence.[2][3] In the field of classical studies, it often refers to the assertion that an author is ignorant of a subject, based on the lack of references to it in the author's available writings.[3]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Argument_from_silence

Secundus the Silent (Ancient Greek: Σεκοῦνδος) (fl. 2nd century AD) was a Cynic or Neopythagorean philosopher who lived in Athens in the early 2nd century, who had taken a vow of silence. An anonymous text entitled Life of Secundus (Latin: Vita Secundi Philosophi) purports to give details of his life as well as answers to philosophical questions posed to him by the emperor Hadrian. The work enjoyed great popularity in the Middle Ages.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Secundus_the_Silent

Noble Silence is a term attributed to the Gautama Buddha, for his reported responses to certain questions about reality. One such instance is when he was asked the fourteen unanswerable questions. In similar situations he often responded to antinomy-based descriptions of reality by saying that both antithetical options presented to him were inappropriate.

A specific reference to noble silence in Buddha's teaching involved an occasion where Buddha forbade his disciples from continuing a discussion, saying that in such congregation the discussion of the sacred doctrine is proper or practicing noble silence.[1] This does not indicate misology or disdain for philosophy on the Buddha's part. Rather, it indicates that he viewed these questions as not leading to true knowledge.[2]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Noble_Silence

A conspiracy of silence, or culture of silence, describes the behavior of a group of people of some size, as large as an entire national group or profession or as small as a group of colleagues, that by unspoken consensus does not mention, discuss, or acknowledge a given subject. The practice may be motivated by positive interest in group solidarity or by such negative impulses as fear of political repercussion or social ostracism. It differs from avoiding a taboo subject in that the term is applied to more limited social and political contexts rather than to an entire culture. As a descriptor, conspiracy of silence implies dishonesty, sometimes cowardice, sometimes privileging loyalty to one social group over another. As a social practice, it is rather more extensive than the use of euphemisms to avoid addressing a topic directly.

Some instances of such a practice are sufficiently well-known or enduring to become known by their own specific terms, including code of silence for the refusal of law enforcement officers to speak out against crimes committed by fellow officers and omertà, cultural code of organized crime in Sicily.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conspiracy_of_silence_(expression)

Stonewalling is a refusal to communicate or cooperate. Such behaviour occurs in situations such as marriage guidance counseling, diplomatic negotiations, politics and legal cases.[1] Body language may indicate and reinforce this by avoiding contact and engagement with the other party.[2] People use deflection in a conversation in order to render a conversation pointless and insignificant. Tactics in stonewalling include giving sparse, vague responses, refusing to answer questions, or responding to questions with additional questions. Stonewalling can be used as a stalling tactic rather than an avoidance tactic.[3]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stonewalling

Obstructionism is the practice of deliberately delaying or preventing a process or change, especially in politics.[1]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Obstructionism

Exploit means to take advantage of something (a person, situation, etc.) for one's own end, especially unethically or unjustifiably.

Exploit can mean:

- Exploitation of natural resources

- Exploit (computer security)

- Video game exploit

- Exploitation of labour, Marxist and other sociological aspects

History

- Exploits River, the longest river on the island of Newfoundland

- Bay of Exploits, a bay of Newfoundland

Other

- Exploit (video game), a browser video game by Gregory Weir

- Exploit, episode of documentary Dark Net (TV series) 2016

See also

- The Exploited, a Scottish punk band

- Overexploitation

- Exploitation (disambiguation)

If an internal link led you here, you may wish to change the link to point directly to the intended article.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Exploit

Overexploitation, also called overharvesting, refers to harvesting a renewable resource to the point of diminishing returns.[2] Continued overexploitation can lead to the destruction of the resource, as it will be unable to replenish. The term applies to natural resources such as water aquifers, grazing pastures and forests, wild medicinal plants, fish stocks and other wildlife.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Overexploitation

The Catch Trap is a novel by Marion Zimmer Bradley, published in 1979. Set in the circus world of the 1940s and 1950s, it tells the story of two trapeze artists, Mario Santelli and Tommy Zane, and the professional relationship they develop which ultimately leads to love.

This rich tale encompasses the exhilarating highs of soaring under the Big Top down to the lows of having to hide their secret relationship from their extended colourful circus family due to the conservative times they live in. What does remain steadfast is their devotion and passion to both their craft and each other.[1]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Catch_Trap

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_states

A globe is a spherical model of Earth, of some other celestial body, or of the celestial sphere. Globes serve purposes similar to maps, but unlike maps, they do not distort the surface that they portray except to scale it down. A model globe of Earth is called a terrestrial globe. A model globe of the celestial sphere is called a celestial globe.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Globe

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Globe_(disambiguation)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Earth

Deliberative democracy or discursive democracy is a form of democracy in which deliberation is central to decision-making. It often adopts elements of both consensus decision-making and majority rule. Deliberative democracy differs from traditional democratic theory in that authentic deliberation, not mere voting, is the primary source of legitimacy for the law. Deliberative democracy is closely related to consultative democracy, in which public consultation with citizens is central to democratic processes.

While deliberative democracy is generally seen as some form of an amalgam of representative democracy and direct democracy, the actual relationship is usually open to dispute.[1] Some practitioners and theorists use the term to encompass representative bodies whose members authentically and practically deliberate on legislation without unequal distributions of power, while others use the term exclusively to refer to decision-making directly by lay citizens, as in direct democracy.

Joseph M. Bessette has been credited with coining the term in his 1980 work Deliberative Democracy: The Majority Principle in Republican Government.[2]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deliberative_democracy

Conscientious objection in the United States is based on the Military Selective Service Act,[1] which delegates its implementation to the Selective Service System.[2] Conscientious objection is also recognized by the Department of Defense.[3]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conscientious_objection_in_the_United_States

A conscientious objector (often shortened to conchie)[1] is an "individual who has claimed the right to refuse to perform military service"[2] on the grounds of freedom of thought, conscience, or religion.[3] The term has also been extended to objecting to working for the military–industrial complex due to a crisis of conscience.[4] In some countries, conscientious objectors are assigned to an alternative civilian service as a substitute for conscription or military service.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conscientious_objector

The inverted black triangle (German: schwarzes Dreieck) was an identification badge used in Nazi concentration camps to mark prisoners designated asozial ("asocial")[1][2] and arbeitsscheu ("work-shy"). The Roma and Sinti people were considered asocial and tagged with the black triangle.[1][3] The designation also included alcoholics, beggars, homeless people, lesbians, nomads, prostitutes, and violators of laws prohibiting sexual relations between Aryans and Jews.[1][2] [2][4]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black_triangle_(badge)

The forestry service[1] was a form of alternative service offered to German speaking Mennonites in lieu of military service in Russia from 1881 to 1918. At its peak during World War I, 7,000 men served in forestry and agricultural pest control in Ukraine and South Russia. The program ended in the turmoil of the Russian Revolution.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Forestry_service_(Russia)

Aamulehti (Finnish for "morning newspaper") is a Finnish-language daily newspaper published in Tampere, Finland.

History and profile

Aamulehti was founded in 1881[1][2] to "improve the position of the Finnish people and the Finnish language" during Russia's rule over Finland.[3] The founders were nationalistic Finns in Tampere.[1][4]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aamulehti

Fragments (Russian: Осколки) was a Russian humorous, literary and artistic weekly magazine published in St Petersburg from 1881 to 1916.

History

From 1881 to 1906 Fragments was published by the popular writer Nikolay Leykin. From 1906 to 1908 it was run by the humorist Viktor Bilibin.[1]

In the 1880s Fragments was known as the most liberal of Russian humorous magazines. Fragments played an important part in the early career of Anton Chekhov. From 1882 to 1887 Fragments published more than 270 of Chekhov's works.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fragments_(magazine)

The Swiss Civilian Service is a Swiss institution, created in 1996 as an civilian substitute service to military service. It was introduced as part of the so-called Vision 95 (Armeeleitbild 95) reform package.[1] Anyone who is unable to do military service for reasons of conscience can submit an application to perform civilian service instead. Formerly, the applicant was then forced to attend a hearing where they had to explain their reasons for refusal. Now, they must simply take part in a one-day introductory session to civilian service within three months of submitting their application.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Swiss_Civilian_Service

A construction soldier (German: Bausoldat, BS) was a non-combat role of the National People's Army, the armed forces of the German Democratic Republic (East Germany), from 1964 to 1990. Bausoldaten were conscientious objectors who accepted conscription but refused armed service and instead served in unarmed construction units. Bausoldaten were the only legal form of conscientious objection in the Warsaw Pact.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Construction_soldier

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not necessarily limited to, governments, nation states,[1] and capitalism. Anarchism advocates for the replacement of the state with stateless societies or other forms of free associations. As a historically left-wing movement, this reading of anarchism is placed on the farthest left of the political spectrum, it is usually described as the libertarian wing of the socialist movement (libertarian socialism).

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anarchism