| William the Conqueror | |

|---|---|

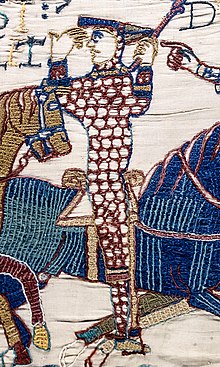

William as depicted in the Bayeux Tapestry during the Battle of Hastings, lifting his helmet to show that he is still alive | |

| King of England | |

| Reign | 25 December 1066 – 9 September 1087 |

| Coronation | 25 December 1066 |

| Predecessor |

|

| Successor | William II |

| Duke of Normandy | |

| Reign | 3 July 1035 – 9 September 1087 |

| Predecessor | Robert I |

| Successor | Robert II |

| Born | c. 1028[1] Falaise, Duchy of Normandy |

| Died | 9 September 1087 (aged about 59) Priory of Saint Gervase, Rouen, Duchy of Normandy |

| Burial | Saint-Étienne de Caen, Normandy |

| Spouse | Matilda of Flanders (married 1051/2; died 1083) |

| Issue Detail | |

| House | Normandy |

| Father | Robert the Magnificent |

| Mother | Herleva of Falaise |

William I[a] (c. 1028[1] – 9 September 1087), usually known as William the Conqueror and sometimes William the Bastard,[2][b] was the first Norman king of England, reigning from 1066 until his death in 1087. A descendant of Rollo, he was Duke of Normandy from 1035 onward. By 1060, following a long struggle to establish his throne, his hold on Normandy was secure. In 1066, following the death of Edward the Confessor, William invaded England, leading an army of Normans to victory over the Anglo-Saxon forces of Harold Godwinson at the Battle of Hastings, and suppressed subsequent English revolts in what has become known as the Norman Conquest. The rest of his life was marked by struggles to consolidate his hold over England and his continental lands, and by difficulties with his eldest son, Robert Curthose.

William was the son of the unmarried Duke Robert I of Normandy and his mistress Herleva. His illegitimate status and his youth caused some difficulties for him after he succeeded his father, as did the anarchy which plagued the first years of his rule. During his childhood and adolescence, members of the Norman aristocracy battled each other, both for control of the child duke, and for their own ends. In 1047, William was able to quash a rebellion and begin to establish his authority over the duchy, a process that was not complete until about 1060. His marriage in the 1050s to Matilda of Flanders provided him with a powerful ally in the neighbouring county of Flanders. By the time of his marriage, William was able to arrange the appointment of his supporters as bishops and abbots in the Norman church. His consolidation of power allowed him to expand his horizons, and he secured control of the neighbouring county of Maine by 1062.

In the 1050s and early 1060s, William became a contender for the throne of England held by the childless Edward the Confessor, his first cousin once removed. There were other potential claimants, including the powerful English earl Harold Godwinson, whom Edward named as king on his deathbed in January 1066. Arguing that Edward had previously promised the throne to him and that Harold had sworn to support his claim, William built a large fleet and invaded England in September 1066. He decisively defeated and killed Harold at the Battle of Hastings on 14 October 1066. After further military efforts, William was crowned king on Christmas Day, 1066, in London. He made arrangements for the governance of England in early 1067 before returning to Normandy. Several unsuccessful rebellions followed, but William's hold was mostly secure on England by 1075, allowing him to spend the greater part of his reign in continental Europe.

William's final years were marked by difficulties in his continental domains, troubles with his son, Robert, and threatened invasions of England by the Danes. In 1086, he ordered the compilation of the Domesday Book, a survey listing all of the land-holdings in England along with their pre-Conquest and current holders. He died in September 1087 while leading a campaign in northern France, and was buried in Caen. His reign in England was marked by the construction of castles, settling a new Norman nobility on the land, and change in the composition of the English clergy. He did not try to integrate his domains into one empire but continued to administer each part separately. His lands were divided after his death: Normandy went to Robert, and England went to his second surviving son, William Rufus.

Background

Norsemen first began raiding in what became Normandy in the late 8th century. Permanent Scandinavian settlement occurred before 911, when Rollo, one of the Viking leaders, and King Charles the Simple of France reached an agreement ceding the county of Rouen to Rollo. The lands around Rouen became the core of the later duchy of Normandy.[3] Normandy may have been used as a base when Scandinavian attacks on England were renewed at the end of the 10th century, which would have worsened relations between England and Normandy.[4] In an effort to improve matters, King Æthelred the Unready took Emma, sister of Richard II, Duke of Normandy, as his second wife in 1002.[5]

Danish raids on England continued, and Æthelred sought help from Richard, taking refuge in Normandy in 1013 when King Swein I of Denmark drove Æthelred and his family from England. Swein's death in 1014 allowed Æthelred to return home, but Swein's son Cnut contested Æthelred's return. Æthelred died unexpectedly in 1016, and Cnut became king of England. Æthelred and Emma's two sons, Edward and Alfred, went into exile in Normandy while their mother, Emma, became Cnut's second wife.[6]

After Cnut's death in 1035, the English throne fell to Harold Harefoot, his son by his first wife, while Harthacnut, his son by Emma, became king in Denmark. England remained unstable. Alfred returned to England in 1036 to visit his mother and perhaps to challenge Harold as king. One story implicates Earl Godwin of Wessex in Alfred's subsequent death, but others blame Harold. Emma went into exile in Flanders until Harthacnut became king following Harold's death in 1040, and his half-brother Edward followed Harthacnut to England; Edward was proclaimed king after Harthacnut's death in June 1042.[7][c]

Early life

William was born in 1027 or 1028 at Falaise, Duchy of Normandy, most likely towards the end of 1028.[1][8][d] He was the only son of Robert I, son of Richard II.[e] His mother Herleva was a daughter of Fulbert of Falaise; he may have been a tanner or embalmer.[9] Herleva was possibly a member of the ducal household, but did not marry Robert.[2] She later married Herluin de Conteville, with whom she had two sons – Odo of Bayeux and Count Robert of Mortain – and a daughter whose name is unknown.[f] One of Herleva's brothers, Walter, became a supporter and protector of William during his minority.[9][g] Robert I also had a daughter, Adelaide, by another mistress.[12]

Robert I succeeded his elder brother Richard III as duke on 6 August 1027.[1] The brothers had been at odds over the succession, and Richard's death was sudden. Robert was accused by some writers of killing Richard, a plausible but now unprovable charge.[13] Conditions in Normandy were unsettled, as noble families despoiled the Church and Alan III of Brittany waged war against the duchy, possibly in an attempt to take control. By 1031 Robert had gathered considerable support from noblemen, many of whom would become prominent during William's life. They included the duke's uncle Robert, the archbishop of Rouen, who had originally opposed the duke; Osbern, a nephew of Gunnor the wife of Richard I; and Gilbert of Brionne, a grandson of Richard I.[14] After his accession, Robert continued Norman support for the English princes Edward and Alfred, who were still in exile in northern France.[2]

There are indications that Robert may have been briefly betrothed to a daughter of King Cnut, but no marriage took place. It is unclear whether William would have been supplanted in the ducal succession if Robert had had a legitimate son. Earlier dukes had been illegitimate, and William's association with his father on ducal charters appears to indicate that William was considered Robert's most likely heir.[2] In 1034 the duke decided to go on pilgrimage to Jerusalem. Although some of his supporters tried to dissuade him from undertaking the journey, he convened a council in January 1035 and had the assembled Norman magnates swear fealty to William as his heir[2][15] before leaving for Jerusalem. He died in early July at Nicea, on his way back to Normandy.[15]

Duke of Normandy

Challenges

William faced several challenges on becoming duke, including his illegitimate birth and his youth: the evidence indicates that he was either seven or eight years old at the time.[16][17][h] He enjoyed the support of his great-uncle, Archbishop Robert, as well as King Henry I of France, enabling him to succeed to his father's duchy.[20] The support given to the exiled English princes in their attempt to return to England in 1036 shows that the new duke's guardians were attempting to continue his father's policies,[2] but Archbishop Robert's death in March 1037 removed one of William's main supporters, and conditions in Normandy quickly descended into chaos.[20]

The anarchy in the duchy lasted until 1047,[21] and control of the young duke was one of the priorities of those contending for power. At first, Alan of Brittany had custody of the duke, but when Alan died in either late 1039 or October 1040, Gilbert of Brionne took charge of William. Gilbert was killed within months, and another guardian, Turchetil, was also killed around the time of Gilbert's death.[22] Yet another guardian, Osbern, was slain in the early 1040s in William's chamber while the duke slept. It was said that Walter, William's maternal uncle, was occasionally forced to hide the young duke in the houses of peasants,[23] although this story may be an embellishment by Orderic Vitalis. The historian Eleanor Searle speculates that William was raised with the three cousins who later became important in his career – William fitzOsbern, Roger de Beaumont, and Roger of Montgomery.[24] Although many of the Norman nobles engaged in their own private wars and feuds during William's minority, the viscounts still acknowledged the ducal government, and the ecclesiastical hierarchy was supportive of William.[25]

King Henry continued to support the young duke,[26] but in late 1046 opponents of William came together in a rebellion centred in lower Normandy, led by Guy of Burgundy with support from Nigel, Viscount of the Cotentin, and Ranulf, Viscount of the Bessin. According to stories that may have legendary elements, an attempt was made to seize William at Valognes, but he escaped under cover of darkness, seeking refuge with King Henry.[27] In early 1047 Henry and William returned to Normandy and were victorious at the Battle of Val-ès-Dunes near Caen, although few details of the actual fighting are recorded.[28] William of Poitiers claimed that the battle was won mainly through William's efforts, but earlier accounts claim that King Henry's men and leadership also played an important part.[2] William assumed power in Normandy, and shortly after the battle promulgated the Truce of God throughout his duchy, in an effort to limit warfare and violence by restricting the days of the year on which fighting was permitted.[29] Although the Battle of Val-ès-Dunes marked a turning point in William's control of the duchy, it was not the end of his struggle to gain the upper hand over the nobility. The period from 1047 to 1054 saw almost continuous warfare, with lesser crises continuing until 1060.[30]

Consolidation of power

William's next efforts were against Guy of Burgundy, who retreated to his castle at Brionne, which William besieged. After a long effort, the duke succeeded in exiling Guy in 1050.[31] To address the growing power of the Count of Anjou, Geoffrey Martel,[32] William joined with King Henry in a campaign against him, the last known cooperation between the two. They succeeded in capturing an Angevin fortress but accomplished little else.[33] Geoffrey attempted to expand his authority into the county of Maine, especially after the death of Hugh IV of Maine in 1051. Central to the control of Maine were the holdings of the Bellême family, who held Bellême on the border of Maine and Normandy, as well as the fortresses at Alençon and Domfront. Bellême's overlord was the king of France, but Domfront was under the overlordship of Geoffrey Martel and Duke William was Alençon's overlord. The Bellême family, whose lands were quite strategically placed between their three different overlords, were able to play each of them against the other and secure virtual independence for themselves.[32]

On the death of Hugh of Maine, Geoffrey Martel occupied Maine in a move contested by William and King Henry; eventually, they succeeded in driving Geoffrey from the county, and in the process, William had been able to secure the Bellême family strongholds at Alençon and Domfront for himself. He was thus able to assert his overlordship over the Bellême family and compel them to act consistently with Norman interests.[34] However, in 1052 the king and Geoffrey Martel made common cause against William at the same time as some Norman nobles began to contest William's increasing power. Henry's about-face was probably motivated by a desire to retain dominance over Normandy, which was now threatened by William's growing mastery of his duchy.[35] William was engaged in military actions against his own nobles throughout 1053,[36] as well as with the new Archbishop of Rouen, Mauger.[37]

In February 1054 the king and the Norman rebels launched a double invasion of the duchy. Henry led the main thrust through the county of Évreux, while the other wing, under the king's brother Odo, invaded eastern Normandy.[38] William met the invasion by dividing his forces into two groups. The first, which he led, faced Henry. The second, which included some who became William's firm supporters, such as Robert, Count of Eu, Walter Giffard, Roger of Mortemer, and William de Warenne, faced the other invading force. This second force defeated the invaders at the Battle of Mortemer. In addition to ending both invasions, the battle allowed the duke's ecclesiastical supporters to depose Archbishop Mauger. Mortemer thus marked another turning point in William's growing control of the duchy,[39] although his conflict with the French king and the Count of Anjou continued until 1060.[40] Henry and Geoffrey led another invasion of Normandy in 1057 but were defeated by William at the Battle of Varaville. This was the last invasion of Normandy during William's lifetime. In 1058, William invaded the County of Dreux and took Tillières-sur-Avre and Thimert. Henry attempted to dislodge William, but the siege of Thimert dragged on for two years until Henry's death. The deaths of Count Geoffrey and the king in 1060 cemented the shift in the balance of power towards William.[41]

One factor in William's favour was his marriage to Matilda of Flanders, the daughter of Count Baldwin V of Flanders. The union was arranged in 1049, but Pope Leo IX forbade the marriage at the Council of Rheims in October 1049.[i] The marriage nevertheless went ahead some time in the early 1050s,[43][j] possibly unsanctioned by the pope. According to a late source not generally considered to be reliable, papal sanction was not secured until 1059, but as papal-Norman relations in the 1050s were generally good, and Norman clergy were able to visit Rome in 1050 without incident, it was probably secured earlier.[45] Papal sanction of the marriage appears to have required the founding of two monasteries in Caen – one by William and one by Matilda.[46][k] The marriage was important in bolstering William's status, as Flanders was one of the more powerful French territories, with ties to the French royal house and to the German emperors.[45] Contemporary writers considered the marriage, which produced four sons and five or six daughters, to be a success.[48]

Appearance and character

No authentic portrait of William has been found; the contemporary depictions of him on the Bayeux Tapestry and on his seals and coins are conventional representations designed to assert his authority.[49] There are some written descriptions of a burly and robust appearance, with a guttural voice. He enjoyed excellent health until old age, although he became quite fat in later life.[50] He was strong enough to draw bows that others were unable to pull and had great stamina.[49] Geoffrey Martel described him as without equal as a fighter and as a horseman.[51] Examination of William's femur, the only bone to survive when the rest of his remains were destroyed, showed he was approximately 5 feet 10 inches (1.78 m) in height.[49]

There are records of two tutors for William during the late 1030s and early 1040s, but the extent of his literary education is unclear. He was not known as a patron of authors, and there is little evidence that he sponsored scholarships or other intellectual activities.[2] Orderic Vitalis records that William tried to learn to read Old English late in life, but he was unable to devote sufficient time to the effort and quickly gave up.[52] William's main hobby appears to have been hunting. His marriage to Matilda appears to have been quite affectionate, and there are no signs that he was unfaithful to her – unusual in a medieval monarch. Medieval writers criticised William for his greed and cruelty, but his personal piety was universally praised by contemporaries.[2]

Norman administration

Norman government under William was similar to the government that had existed under earlier dukes. It was a fairly simple administrative system, built around the ducal household,[53] which consisted of a group of officers including stewards, butlers, and marshals.[54] The duke travelled constantly around the duchy, confirming charters and collecting revenues.[55] Most of the income came from the ducal lands, as well as from tolls and a few taxes. This income was collected by the chamber, one of the household departments.[54]

William cultivated close relations with the church in his duchy. He took part in church councils and made several appointments to the Norman episcopate, including the appointment of Maurilius as Archbishop of Rouen.[56] Another important appointment was that of William's half-brother, Odo, as Bishop of Bayeux in either 1049 or 1050.[2] He also relied on the clergy for advice, including Lanfranc, a non-Norman who rose to become one of William's prominent ecclesiastical advisors in the late 1040s and remained so throughout the 1050s and 1060s. William gave generously to the church;[56] from 1035 to 1066, the Norman aristocracy founded at least twenty new monastic houses, including William's two monasteries in Caen, a remarkable expansion of religious life in the duchy.[57]

English and continental concerns

In 1051 the childless King Edward of England appears to have chosen William as his successor.[58] William was the grandson of Edward's maternal uncle, Richard II of Normandy.[58]

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, in the "D" version, states that William visited England in the later part of 1051, perhaps to secure confirmation of the succession,[59] or perhaps William was attempting to secure aid for his troubles in Normandy.[60] The trip is unlikely given William's absorption in warfare with Anjou at the time. Whatever Edward's wishes, it was likely that any claim by William would be opposed by Godwin, Earl of Wessex, a member of the most powerful family in England.[59] Edward had married Edith, Godwin's daughter, in 1043, and Godwin appears to have been one of the main supporters of Edward's claim to the throne.[61] By 1050, however, relations between the king and the earl had soured, culminating in a crisis in 1051 that led to the exile of Godwin and his family from England. It was during this exile that Edward offered the throne to William.[62] Godwin returned from exile in 1052 with armed forces, and a settlement was reached between the king and the earl, restoring the earl and his family to their lands and replacing Robert of Jumièges, a Norman whom Edward had named Archbishop of Canterbury, with Stigand, the Bishop of Winchester.[63] No English source mentions a supposed embassy by Archbishop Robert to William conveying the promise of the succession, and the two Norman sources that mention it, William of Jumièges and William of Poitiers, are not precise in their chronology of when this visit took place.[60]

Count Herbert II of Maine died in 1062, and William, who had betrothed his eldest son Robert to Herbert's sister Margaret, claimed the county through his son. Local nobles resisted the claim, but William invaded and by 1064 had secured control of the area.[64] William appointed a Norman to the bishopric of Le Mans in 1065. He also allowed his son Robert Curthose to do homage to the new Count of Anjou, Geoffrey the Bearded.[65] William's western border was thus secured, but his border with Brittany remained insecure. In 1064 William invaded Brittany in a campaign that remains obscure in its details. Its effect, though, was to destabilise Brittany, forcing the duke, Conan II, to focus on internal problems rather than on expansion. Conan's death in 1066 further secured William's borders in Normandy. William also benefited from his campaign in Brittany by securing the support of some Breton nobles who went on to support the invasion of England in 1066.[66]

In England, Earl Godwin died in 1053 and his sons were increasing in power: Harold succeeded to his father's earldom, and another son, Tostig, became Earl of Northumbria. Other sons were granted earldoms later: Gyrth as Earl of East Anglia in 1057 and Leofwine as Earl of Kent sometime between 1055 and 1057.[67] Some sources claim that Harold took part in William's Breton campaign of 1064 and swore to uphold William's claim to the English throne at the end of the campaign,[65] but no English source reports this trip, and it is unclear if it actually occurred. It may have been Norman propaganda designed to discredit Harold, who had emerged as the main contender to succeed King Edward.[68] Meanwhile, another contender for the throne had emerged – Edward the Exile, son of Edmund Ironside and a grandson of Æthelred II, returned to England in 1057, and although he died shortly after his return, he brought with him his family, which included two daughters, Margaret and Christina, and a son, Edgar the Ætheling.[69][l]

In 1065 Northumbria revolted against Tostig, and the rebels chose Morcar, the younger brother of Edwin, Earl of Mercia, as earl in place of Tostig. Harold, perhaps to secure the support of Edwin and Morcar in his bid for the throne, supported the rebels and persuaded King Edward to replace Tostig with Morcar. Tostig went into exile in Flanders, along with his wife Judith, who was the daughter of Baldwin IV, Count of Flanders. Edward was ailing, and he died on 5 January 1066. It is unclear what exactly happened at Edward's deathbed. One story, deriving from the Vita Ædwardi, a biography of Edward, claims that he was attended by his wife Edith, Harold, Archbishop Stigand, and Robert FitzWimarc, and that the king named Harold as his successor. The Norman sources do not dispute the fact that Harold was named as the next king, but they declare that Harold's oath and Edward's earlier promise of the throne could not be changed on Edward's deathbed. Later English sources stated that Harold had been elected as king by the clergy and magnates of England.[71]

Invasion of England

Harold's preparations

Harold was crowned on 6 January 1066 in Edward's new Norman-style Westminster Abbey, although some controversy surrounds who performed the ceremony. English sources claim that Ealdred, the Archbishop of York, performed the ceremony, while Norman sources state that the coronation was performed by Stigand, who was considered a non-canonical archbishop by the papacy.[72] Harold's claim to the throne was not entirely secure, as there were other claimants, perhaps including his exiled brother Tostig.[73][m] King Harald Hardrada of Norway also had a claim to the throne as the uncle and heir of King Magnus I, who had made a pact with Harthacnut in about 1040 that if either Magnus or Harthacnut died without heirs, the other would succeed.[77] The last claimant was William of Normandy, against whose anticipated invasion King Harold Godwinson made most of his preparations.[73]

Harold's brother Tostig made probing attacks along the southern coast of England in May 1066, landing at the Isle of Wight using a fleet supplied by Baldwin of Flanders. Tostig appears to have received little local support, and further raids into Lincolnshire and near the River Humber met with no more success, so he retreated to Scotland, where he remained for a time. According to the Norman writer William of Jumièges, William had meanwhile sent an embassy to King Harold Godwinson to remind Harold of his oath to support William's claim, although whether this embassy actually occurred is unclear. Harold assembled an army and a fleet to repel William's anticipated invasion force, deploying troops and ships along the English Channel for most of the summer.[73]

William's preparations

William of Poitiers describes a council called by Duke William, in which the writer gives an account of a great debate that took place between William's nobles and supporters over whether to risk an invasion of England. Although some sort of formal assembly probably was held, it is unlikely that any debate took place, as the duke had by then established control over his nobles, and most of those assembled would have been anxious to secure their share of the rewards from the conquest of England.[78] William of Poitiers also relates that the duke obtained the consent of Pope Alexander II for the invasion, along with a papal banner. The chronicler also claimed that the duke secured the support of Henry IV, Holy Roman Emperor, and King Sweyn II of Denmark. Henry was still a minor, however, and Sweyn was more likely to support Harold, who could then help Sweyn against the Norwegian king, so these claims should be treated with caution. Although Alexander did give papal approval to the conquest after it succeeded, no other source claims papal support prior to the invasion.[n][79] Events after the invasion, which included the penance William performed and statements by later popes, do lend circumstantial support to the claim of papal approval. To deal with Norman affairs, William put the government of Normandy into the hands of his wife for the duration of the invasion.[2]

Throughout the summer, William assembled an army and an invasion fleet in Normandy. Although William of Jumièges's claim that the ducal fleet numbered 3,000 ships is clearly an exaggeration, it was probably large and mostly built from scratch. Although William of Poitiers and William of Jumièges disagree about where the fleet was built – Poitiers states it was constructed at the mouth of the River Dives, while Jumièges states it was built at Saint-Valery-sur-Somme – both agree that it eventually sailed from Valery-sur-Somme. The fleet carried an invasion force that included, in addition to troops from William's own territories of Normandy and Maine, large numbers of mercenaries, allies, and volunteers from Brittany, northeastern France, and Flanders, together with smaller numbers from other parts of Europe. Although the army and fleet were ready by early August, adverse winds kept the ships in Normandy until late September. There were probably other reasons for William's delay, including intelligence reports from England revealing that Harold's forces were deployed along the coast. William would have preferred to delay the invasion until he could make an unopposed landing.[79] Harold kept his forces on alert throughout the summer, but with the arrival of the harvest season he disbanded his army on 8 September.[80]

Tostig and Hardrada's invasion

Tostig Godwinson and Harald Hardrada invaded Northumbria in September 1066 and defeated the local forces under Morcar and Edwin at the Battle of Fulford near York. King Harold received word of their invasion and marched north, defeating the invaders and killing Tostig and Hardrada on 25 September at the Battle of Stamford Bridge.[77] The Norman fleet finally set sail two days later, landing in England at Pevensey Bay on 28 September. William then moved to Hastings, a few miles to the east, where he built a castle as a base of operations. From there, he ravaged the interior and waited for Harold's return from the north, refusing to venture far from the sea, his line of communication with Normandy.[80]

Battle of Hastings

After defeating Harald Hardrada and Tostig, Harold left much of his army in the north, including Morcar and Edwin, and marched the rest south to deal with the threatened Norman invasion.[80] He probably learned of William's landing while he was travelling south. Harold stopped in London, and was there for about a week before marching to Hastings, so it is likely that he spent about a week on his march south, averaging about 27 miles (43 kilometres) per day,[81] for the distance of approximately 200 miles (320 kilometres).[82] Although Harold attempted to surprise the Normans, William's scouts reported the English arrival to the duke. The exact events preceding the battle are obscure, with contradictory accounts in the sources, but all agree that William led his army from his castle and advanced towards the enemy.[83] Harold had taken a defensive position at the top of Senlac Hill (present-day Battle, East Sussex), about 6 miles (9.7 kilometres) from William's castle at Hastings.[84]

The battle began at about 9 am on 14 October and lasted all day, but while a broad outline is known, the exact events are obscured by contradictory accounts in the sources.[85] Although the numbers on each side were about equal, William had both cavalry and infantry, including many archers, while Harold had only foot soldiers and few, if any, archers.[86] The English soldiers formed up as a shield wall along the ridge and were at first so effective that William's army was thrown back with heavy casualties. Some of William's Breton troops panicked and fled, and some of the English troops appear to have pursued the fleeing Bretons until they themselves were attacked and destroyed by Norman cavalry. During the Bretons' flight, rumours swept through the Norman forces that the duke had been killed, but William succeeded in rallying his troops. Two further Norman retreats were feigned, to once again draw the English into pursuit and expose them to repeated attacks by the Norman cavalry.[87] The available sources are more confused about events in the afternoon, but it appears that the decisive event was Harold's death, about which differing stories are told. William of Jumièges claimed that Harold was killed by the duke. The Bayeux Tapestry has been claimed to show Harold's death by an arrow to the eye, but that may be a later reworking of the tapestry to conform to 12th-century stories in which Harold was slain by an arrow wound to the head.[88]

Harold's body was identified the day after the battle, either through his armour or marks on his body. The English dead, who included some of Harold's brothers and his housecarls, were left on the battlefield. Gytha Thorkelsdóttir, Harold's mother, offered the victorious duke the weight of her son's body in gold for its custody, but her offer was refused.[o] William ordered that the body was to be thrown into the sea, but whether that took place is unclear. Waltham Abbey, which had been founded by Harold, later claimed that his body had been secretly buried there.[92]

March on London

William may have hoped the English would surrender following his victory, but they did not. Instead, some of the English clergy and magnates nominated Edgar the Ætheling as king, though their support for Edgar was only lukewarm. After waiting a short while, William secured Dover, parts of Kent, and Canterbury, while also sending a force to capture Winchester, where the royal treasury was.[93] These captures secured William's rear areas and also his line of retreat to Normandy, if that was needed.[2] William then marched to Southwark, across the Thames from London, which he reached in late November. Next, he led his forces around the south and west of London, burning along the way. He finally crossed the Thames at Wallingford in early December. Stigand submitted to William there, and when the duke moved on to Berkhamsted soon afterwards, Edgar the Ætheling, Morcar, Edwin, and Ealdred also submitted. William then sent forces into London to construct a castle; he was crowned at Westminster Abbey on Christmas Day 1066.[93]

Consolidation

First actions

William remained in England after his coronation and tried to reconcile the native magnates. The remaining earls – Edwin (of Mercia), Morcar (of Northumbria), and Waltheof (of Northampton) – were confirmed in their lands and titles.[94] Waltheof was married to William's niece Judith, daughter of his half-sister Adelaide,[95] and a marriage between Edwin and one of William's daughters was proposed. Edgar the Ætheling also appears to have been given lands. Ecclesiastical offices continued to be held by the same bishops as before the invasion, including the uncanonical Stigand.[94] But the families of Harold and his brothers lost their lands, as did some others who had fought against William at Hastings.[96] By March, William was secure enough to return to Normandy, but he took with him Stigand, Morcar, Edwin, Edgar, and Waltheof. He left his half-brother Odo, the Bishop of Bayeux, in charge of England along with another influential supporter, William fitzOsbern, the son of his former guardian.[94] Both men were also named to earldoms – fitzOsbern to Hereford (or Wessex) and Odo to Kent.[2] Although he put two Normans in overall charge, he retained many of the native English sheriffs.[96] Once in Normandy the new English king went to Rouen and the Abbey of Fecamp,[94] and then attended the consecration of new churches at two Norman monasteries.[2]

While William was in Normandy, a former ally, Eustace, the Count of Boulogne, invaded at Dover but was repulsed. English resistance had also begun, with Eadric the Wild attacking Hereford and revolts at Exeter, where Harold's mother Gytha was a focus of resistance.[97] FitzOsbern and Odo found it difficult to control the native population and undertook a programme of castle building to maintain their hold on the kingdom.[2] William returned to England in December 1067 and marched on Exeter, which he besieged. The town held out for 18 days, and after it fell to William he built a castle to secure his control. Harold's sons were meanwhile raiding the southwest of England from a base in Ireland. Their forces landed near Bristol but were defeated by Eadnoth. By Easter, William was at Winchester, where he was soon joined by his wife Matilda, who was crowned in May 1068.[97]

English resistance

In 1068 Edwin and Morcar revolted, supported by Gospatric, Earl of Northumbria. The chronicler Orderic Vitalis states that Edwin's reason for revolting was that the proposed marriage between himself and one of William's daughters had not taken place, but another reason probably included the increasing power of fitzOsbern in Herefordshire, which affected Edwin's power within his own earldom. The king marched through Edwin's lands and built Warwick Castle. Edwin and Morcar submitted, but William continued on to York, building York and Nottingham Castles before returning south. On his southbound journey, he began constructing Lincoln, Huntingdon, and Cambridge Castles. William placed supporters in charge of these new fortifications – among them William Peverel at Nottingham and Henry de Beaumont at Warwick. Then the king returned to Normandy late in 1068.[97]

Early in 1069, Edgar the Ætheling rose in revolt and attacked York. Although William returned to York and built another castle, Edgar remained free, and in the autumn he joined up with King Sweyn.[p] The Danish king had brought a large fleet to England and attacked not only York but Exeter and Shrewsbury. York was captured by the combined forces of Edgar and Sweyn. Edgar was proclaimed king by his supporters. William responded swiftly, ignoring a continental revolt in Maine, and symbolically wore his crown in the ruins of York on Christmas Day 1069. He then proceeded to buy off the Danes. He marched to the River Tees, ravaging the countryside as he went. Edgar, having lost much of his support, fled to Scotland,[98] where King Malcolm III was married to Edgar's sister Margaret.[99] Waltheof, who had joined the revolt, submitted, along with Gospatric, and both were allowed to retain their lands. But William was not finished; he marched over the Pennines during the winter and defeated the remaining rebels at Shrewsbury before building Chester and Stafford Castles. This campaign, which included the burning and destruction of part of the countryside that the royal forces marched through, is usually known as the "Harrying of the North"; it was over by April 1070, when William wore his crown ceremonially for Easter at Winchester.[98]

Church affairs

While at Winchester in 1070, William met with three papal legates – John Minutus, Peter, and Ermenfrid of Sion – who had been sent by the pope. The legates ceremonially crowned William during the Easter court.[100] The historian David Bates sees this coronation as the ceremonial papal "seal of approval" for William's conquest.[2] The legates and the king then proceeded to hold a series of ecclesiastical councils dedicated to reforming and reorganising the English church. Stigand and his brother, Æthelmær, the Bishop of Elmham, were deposed from their bishoprics. Some of the native abbots were also deposed, both at the council held near Easter and at a further one near Whitsun. The Whitsun council saw the appointment of Lanfranc as the new Archbishop of Canterbury, and Thomas of Bayeux as the new Archbishop of York, to replace Ealdred, who had died in September 1069.[100] William's half-brother Odo perhaps expected to be appointed to Canterbury, but William probably did not wish to give that much power to a family member.[q] Another reason for the appointment may have been pressure from the papacy to appoint Lanfranc.[101] Norman clergy were appointed to replace the deposed bishops and abbots, and at the end of the process, only two native English bishops remained in office, along with several continental prelates appointed by Edward the Confessor.[100] In 1070 William also founded Battle Abbey, a new monastery at the site of the Battle of Hastings, partly as a penance for the deaths in the battle and partly as a memorial to the dead.[2] At an ecclesiastical council held in Lillebonne in 1080, he was confirmed in his ultimate authority over the Norman church.[102]

Troubles in England and on the Continent

Danish raids and rebellion

Although Sweyn had promised to leave England, he returned in early 1070, raiding along the Humber and East Anglia toward the Isle of Ely, where he joined up with Hereward the Wake, a local thegn. Hereward's forces attacked Peterborough Abbey, which they captured and looted. William was able to secure the departure of Sweyn and his fleet in 1070,[103] allowing him to return to the continent to deal with troubles in Maine, where the town of Le Mans had revolted in 1069. Another concern was the death of Count Baldwin VI of Flanders in July 1070, which led to a succession crisis as his widow, Richilde, was ruling for their two young sons, Arnulf and Baldwin. Her rule was contested by Robert, Baldwin's brother. Richilde proposed marriage to William fitzOsbern, who was in Normandy, and fitzOsbern accepted. But after he was killed in February 1071 at the Battle of Cassel, Robert became count. He was opposed to King William's power on the continent, thus the Battle of Cassel upset the balance of power in northern France as well as costing William an important supporter.[104]

In 1071 William defeated the last rebellion of the north. Earl Edwin was betrayed by his own men and killed, while William built a causeway to subdue the Isle of Ely, where Hereward the Wake and Morcar were hiding. Hereward escaped, but Morcar was captured, deprived of his earldom, and imprisoned. In 1072 William invaded Scotland, defeating Malcolm, who had recently invaded the north of England. William and Malcolm agreed to peace by signing the Treaty of Abernethy, and Malcolm probably gave up his son Duncan as a hostage for the peace. Perhaps another stipulation of the treaty was the expulsion of Edgar the Ætheling from Malcolm's court.[105] William then turned his attention to the continent, returning to Normandy in early 1073 to deal with the invasion of Maine by Fulk le Rechin, the Count of Anjou. With a swift campaign, William seized Le Mans from Fulk's forces, completing the campaign by 30 March 1073. This made William's power more secure in northern France, but the new count of Flanders accepted Edgar the Ætheling into his court. Robert also married his half-sister Bertha to King Philip I of France, who was opposed to Norman power.[106]

William returned to England to release his army from service in 1073 but quickly returned to Normandy, where he spent all of 1074.[107] He left England in the hands of his supporters, including Richard fitzGilbert and William de Warenne,[108] as well as Lanfranc.[109] William's ability to leave England for an entire year was a sign that he felt that his control of the kingdom was secure.[108] While William was in Normandy, Edgar the Ætheling returned to Scotland from Flanders. The French king, seeking a focus for those opposed to William's power, then proposed that Edgar be given the castle of Montreuil-sur-Mer on the Channel, which would have given Edgar a strategic advantage against William.[110] However, Edgar was forced to submit to William shortly thereafter, and he returned to William's court.[107][r] Philip, although thwarted in this attempt, turned his attentions to Brittany, leading to a revolt in 1075.[110]

Revolt of the Earls

In 1075, during William's absence, Ralph de Gael, the Earl of Norfolk, and Roger de Breteuil, the Earl of Hereford, conspired to overthrow William in the "Revolt of the Earls".[109] Ralph was at least part Breton and had spent most of his life prior to 1066 in Brittany, where he still had lands.[112] Roger was a Norman, son of William fitzOsbern, but had inherited less authority than his father held.[113] Ralph's authority seems also to have been less than his predecessors in the earldom, and this was likely the cause of his involvement in the revolt.[112]

The exact reason for the rebellion is unclear, but it was launched at the wedding of Ralph to a relative of Roger, held at Exning in Suffolk. Waltheof, the earl of Northumbria, although one of William's favourites, was also involved, and there were some Breton lords who were ready to rebel in support of Ralph and Roger. Ralph also requested Danish aid. William remained in Normandy while his men in England subdued the revolt. Roger was unable to leave his stronghold in Herefordshire because of efforts by Wulfstan, the Bishop of Worcester, and Æthelwig, the Abbot of Evesham. Ralph was bottled up in Norwich Castle by the combined efforts of Odo of Bayeux, Geoffrey de Montbray, Richard fitzGilbert, and William de Warenne. Ralph eventually left Norwich in the control of his wife and left England, finally ending up in Brittany. Norwich was besieged and surrendered, with the garrison allowed to go to Brittany. Meanwhile, the Danish king's brother, Cnut, had finally arrived in England with a fleet of 200 ships, but he was too late as Norwich had already surrendered. The Danes then raided along the coast before returning home.[109] William returned to England later in 1075 to deal with the Danish threat, leaving his wife Matilda in charge of Normandy. He celebrated Christmas at Winchester and dealt with the aftermath of the rebellion.[114] Roger and Waltheof were kept in prison, where Waltheof was executed in May 1076. Before this, William had returned to the continent, where Ralph had continued the rebellion from Brittany.[109]

Troubles at home and abroad

Earl Ralph had secured control of the castle at Dol, and in September 1076 William advanced into Brittany and laid siege to the castle. King Philip of France later relieved the siege and defeated William at the Battle of Dol in 1076, forcing him to retreat back to Normandy. Although this was William's first defeat in battle, it did little to change things. An Angevin attack on Maine was defeated in late 1076 or 1077, with Count Fulk le Rechin wounded in the unsuccessful attack. More serious was the retirement of Simon de Crépy, the Count of Amiens, to a monastery. Before he became a monk, Simon handed his county of the Vexin over to King Philip. The Vexin was a buffer state between Normandy and the lands of the French king, and Simon had been a supporter of William.[s] William was able to make peace with Philip in 1077 and secured a truce with Count Fulk in late 1077 or early 1078.[115]

In late 1077 or early 1078 trouble began between William and his eldest son, Robert. Although Orderic Vitalis describes it as starting with a quarrel between Robert and his two younger brothers, William and Henry, including a story that the quarrel was started when William and Henry threw water at Robert, it is much more likely that Robert was feeling powerless. Orderic relates that he had previously demanded control of Maine and Normandy and had been rebuffed. The trouble in 1077 or 1078 resulted in Robert leaving Normandy accompanied by a band of young men, many of them the sons of William's supporters. Included among them were Robert of Belleme, William de Breteuil, and Roger, the son of Richard fitzGilbert. This band of young men went to the castle at Remalard, where they proceeded to raid into Normandy. The raiders were supported by many of William's continental enemies.[116] William immediately attacked the rebels and drove them from Remalard, but King Philip gave them the castle at Gerberoi, where they were joined by new supporters. William then laid siege to Gerberoi in January 1079. After three weeks, the besieged forces sallied from the castle and managed to take the besiegers by surprise. William was unhorsed by Robert and was only saved from death by an Englishman, Toki son of Wigod, who was himself killed.[117] William's forces were forced to lift the siege, and the king returned to Rouen. By 12 April 1080, William and Robert had reached an accommodation, with William once more affirming that Robert would receive Normandy when he died.[118]

Word of William's defeat at Gerberoi stirred up difficulties in northern England. In August and September 1079 King Malcolm of Scots raided south of the River Tweed, devastating the land between the River Tees and the Tweed in a raid that lasted almost a month. The lack of Norman response appears to have caused the Northumbrians to grow restive, and in the spring of 1080 they rebelled against the rule of Walcher, the Bishop of Durham and Earl of Northumbria. Walcher was killed on 14 May 1080, and the king dispatched his half-brother Odo to deal with the rebellion.[119] William departed Normandy in July 1080,[120] and in the autumn his son Robert was sent on a campaign against the Scots. Robert raided into Lothian and forced Malcolm to agree to terms, building a fortification (the 'new castle') at Newcastle upon Tyne while returning to England.[119] The king was at Gloucester for Christmas 1080 and at Winchester for Whitsun in 1081, ceremonially wearing his crown on both occasions. A papal embassy arrived in England during this period, asking that William do fealty for England to the papacy, a request that he rejected.[120] William also visited Wales in 1081, although the English and the Welsh sources differ on the exact purpose of the visit. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle states that it was a military campaign, but Welsh sources record it as a pilgrimage to St Davids in honour of Saint David. William's biographer David Bates argues that the former explanation is more likely, explaining that the balance of power had recently shifted in Wales and that William would have wished to take advantage of the changed circumstances to extend Norman power. By the end of 1081, William was back on the continent, dealing with disturbances in Maine. Although he led an expedition into Maine, the result was instead a negotiated settlement arranged by a papal legate.[121]

Last years

Sources for William's actions between 1082 and 1084 are meagre. According to the historian David Bates, this probably means that little of note happened, and that because William was on the continent, there was nothing for the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle to record.[122] In 1082 William ordered the arrest of his half-brother Odo. The exact reasons are unclear, as no contemporary author recorded what caused the quarrel between the half-brothers. Orderic Vitalis later recorded that Odo had aspirations to become pope. Orderic also related that Odo had attempted to persuade some of William's vassals to join Odo in an invasion of southern Italy. This would have been considered tampering with the king's authority over his vassals, which William would not have tolerated. Although Odo remained in confinement for the rest of William's reign, his lands were not confiscated. More difficulties struck in 1083 when William's son Robert rebelled once more with support from the French king. A further blow was the death of Queen Matilda on 2 November 1083. William was always described as close to his wife, and her death would have added to his problems.[123]

Maine continued to be difficult, with a rebellion by Hubert de Beaumont-au-Maine, probably in 1084. Hubert was besieged in his castle at Sainte-Suzanne by William's forces for at least two years, but he eventually made his peace with the king and was restored to favour. William's movements during 1084 and 1085 are unclear – he was in Normandy at Easter 1084 but may have been in England before then to collect the danegeld assessed that year for the defence of England against an invasion by King Cnut IV of Denmark. Although English and Norman forces remained on alert throughout 1085 and into 1086, the invasion threat was ended by Cnut's death in July 1086.[124]

William as king

Changes in England

As part of his efforts to secure England, William ordered many castles, keeps, and mottes built – among them the central keep of the Tower of London, the White Tower. These fortifications allowed Normans to retreat into safety when threatened with rebellion and allowed garrisons to be protected while they occupied the countryside. The early castles were simple earth and timber constructions, later replaced with stone structures.[126]

At first, most of the newly settled Normans kept household knights and did not settle their retainers with fiefs of their own, but gradually these household knights came to be granted lands of their own, a process known as subinfeudation. William also required his newly created magnates to contribute fixed quotas of knights towards not only military campaigns but also castle garrisons. This method of organising the military forces was a departure from the pre-Conquest English practice of basing military service on territorial units such as the hide.[127]

By William's death, after weathering a series of rebellions, most of the native Anglo-Saxon aristocracy had been replaced by Norman and other continental magnates. Not all of the Normans who accompanied William in the initial conquest acquired large amounts of land in England. Some appear to have been reluctant to take up lands in a kingdom that did not always appear pacified. Although some of the newly rich Normans in England came from William's close family or from the upper Norman nobility, others were from relatively humble backgrounds.[128] William granted some lands to his continental followers from the holdings of one or more specific Englishmen; at other times, he granted a compact grouping of lands previously held by many different Englishmen to one Norman follower, often to allow for the consolidation of lands around a strategically placed castle.[129]

The medieval chronicler William of Malmesbury says that the king also seized and depopulated many miles of land (36 parishes), turning it into the royal New Forest region to support his enthusiastic enjoyment of hunting. Modern historians have come to the conclusion that the New Forest depopulation was greatly exaggerated. Most of the lands of the New Forest are poor agricultural lands, and archaeological and geographic studies have shown that it was likely sparsely settled when it was turned into a royal forest.[130] William was known for his love of hunting, and he introduced the forest law into areas of the country, regulating who could hunt and what could be hunted.[131]

Administration

After 1066, William did not attempt to integrate his separate domains into one unified realm with one set of laws. His seal from after 1066, of which six impressions still survive, was made for him after he conquered England and stressed his role as king, while separately mentioning his role as duke.[t] When in Normandy, William acknowledged that he owed fealty to the French king, but in England no such acknowledgement was made – further evidence that the various parts of William's lands were considered separate. The administrative machinery of Normandy, England, and Maine continued to exist separate from the other lands, with each one retaining its own forms. For example, England continued the use of writs, which were not known on the continent. Also, the charters and documents produced for the government in Normandy differed in formulas from those produced in England.[132]

William took over an English government that was more complex than the Norman system. England was divided into shires or counties, which were further divided into either hundreds or wapentakes. Each shire was administered by a royal official called a sheriff, who roughly had the same status as a Norman viscount. A sheriff was responsible for royal justice and collecting royal revenue.[54] To oversee his expanded domain, William was forced to travel even more than he had as duke. He crossed back and forth between the continent and England at least 19 times between 1067 and his death. William spent most of his time in England between the Battle of Hastings and 1072, and after that, he spent the majority of his time in Normandy.[133][u] Government was still centred on William's household; when he was in one part of his realms, decisions would be made for other parts of his domains and transmitted through a communication system that made use of letters and other documents. William also appointed deputies who could make decisions while he was absent, especially if the absence was expected to be lengthy. Usually, this was a member of William's close family – frequently his half-brother Odo or his wife Matilda. Sometimes deputies were appointed to deal with specific issues.[134]

William continued the collection of Danegeld, a land tax. This was an advantage for William, as it was the only universal tax collected by western European rulers during this period. It was an annual tax based on the value of landholdings, and it could be collected at differing rates. Most years saw the rate of two shillings per hide, but in crises, it could be increased to as much as six shillings per hide.[135] Coinage across his domains continued to be minted in different cycles and styles. English coins were generally of high silver content, with high artistic standards, and were required to be re-minted every three years. Norman coins had a much lower silver content, were often of poor artistic quality, and were rarely re-minted. Also, in England, no other coinage was allowed, while on the continent other coinage was considered legal tender. Nor is there evidence that many English pennies were circulating in Normandy, which shows little attempt to integrate the monetary systems of England and Normandy.[132]

Besides taxation, William's large landholdings throughout England strengthened his rule. As King Edward's heir, he controlled all of the former royal lands. He also retained control of much of the lands of Harold and his family, which made the king the largest secular landowner in England by a wide margin.[v]

Domesday Book

At Christmas 1085, William ordered the compilation of a survey of the landholdings held by himself and by his vassals throughout his kingdom, organised by counties. It resulted in a work now known as the Domesday Book. The listing for each county gives the holdings of each landholder, grouped by owners. The listings describe the holding, who owned the land before the Conquest, its value, what the tax assessment was, and usually the number of peasants, ploughs, and any other resources the holding had. Towns were listed separately. All the English counties south of the River Tees and River Ribble are included, and the whole work seems to have been mostly completed by 1 August 1086, when the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records that William received the results and that all the chief magnates swore the Salisbury Oath, a renewal of their oaths of allegiance.[137] William's exact motivation in ordering the survey is unclear, but it probably had several purposes, such as making a record of feudal obligations and justifying increased taxation.[2]

Death and aftermath

William left England towards the end of 1086. Following his arrival back on the continent he married his daughter Constance to Duke Alan of Brittany, in furtherance of his policy of seeking allies against the French kings. William's son Robert, still allied with the French king, appears to have been active in stirring up trouble, enough so that William led an expedition against the French Vexin in July 1087. While seizing Mantes, William either fell ill or was injured by the pommel of his saddle.[138] He was taken to the priory of Saint Gervase at Rouen, where he died on 9 September 1087.[2] Knowledge of the events preceding his death is confused because there are two different accounts. Orderic Vitalis preserves a lengthy account, complete with speeches made by many of the principals, but this is likely more of an account of how a king should die than of what actually happened. The other, the De obitu Willelmi, or On the Death of William, has been shown to be a copy of two 9th-century accounts with names changed.[138]

William left Normandy to Robert, and the custody of England was given to William's second surviving son, also called William, on the assumption that he would become king. The youngest son, Henry, received money. After entrusting England to his second son, the elder William sent the younger William back to England on 7 or 8 September, bearing a letter to Lanfranc ordering the archbishop to aid the new king. Other bequests included gifts to the Church and money to be distributed to the poor. William also ordered that all of his prisoners be released, including his half-brother Odo.[138]

Disorder followed William's death; everyone who had been at his deathbed left the body at Rouen and hurried off to attend to their own affairs. Eventually, the clergy of Rouen arranged to have the body sent to Caen, where William had desired to be buried in his foundation of the Abbaye-aux-Hommes. The funeral, attended by the bishops and abbots of Normandy as well as his son Henry, was disturbed by the assertion of a citizen of Caen who alleged that his family had been illegally despoiled of the land on which the church was built. After hurried consultations, the allegation was shown to be true, and the man was compensated. A further indignity occurred when the corpse was lowered into the tomb. The corpse was too large for the space, and when attendants forced the body into the tomb it burst, spreading a disgusting odour throughout the church.[139]

William's grave is currently marked by a marble slab with a Latin inscription dating from the early 19th century. The tomb has been disturbed several times since 1087, the first time in 1522 when the grave was opened on orders from the papacy. The intact body was restored to the tomb at that time, but in 1562, during the French Wars of Religion, the grave was reopened and the bones scattered and lost, with the exception of one thigh bone. This lone relic was reburied in 1642 with a new marker, which was replaced 100 years later with a more elaborate monument. This tomb was again destroyed during the French Revolution but was eventually replaced with the current ledger stone.[140][w]

Legacy

The immediate consequence of William's death was a war between his sons Robert and William over control of England and Normandy.[2] Even after the younger William's death in 1100 and the succession of his youngest brother Henry as king, Normandy and England remained contested between the brothers until Robert's capture by Henry at the Battle of Tinchebray in 1106. The difficulties over the succession led to a loss of authority in Normandy, with the aristocracy regaining much of the power they had lost to the elder William. His sons also lost much of their control over Maine, which revolted in 1089 and managed to remain mostly free of Norman influence thereafter.[142]

The impact on England of William's conquest was profound; changes in the Church, aristocracy, culture, and language of the country have persisted into modern times. The Conquest brought the kingdom into closer contact with France and forged ties between France and England that lasted throughout the Middle Ages. Another consequence of William's invasion was the sundering of the formerly close ties between England and Scandinavia. William's government blended elements of the English and Norman systems into a new one that laid the foundations of the later medieval English kingdom.[143] How abrupt and far-reaching the changes were is still a matter of debate among historians, with some such as Richard Southern claiming that the Conquest was the single most radical change in European history between the Fall of Rome and the 20th century. Others, such as H. G. Richardson and G. O. Sayles, see the changes brought about by the Conquest as much less radical than Southern suggests.[144] The historian Eleanor Searle describes William's invasion as "a plan that no ruler but a Scandinavian would have considered".[145]

William's reign has caused historical controversy since before his death. William of Poitiers wrote glowingly of William's reign and its benefits, but the obituary notice for William in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle condemns William in harsh terms.[144] In the years since the Conquest, politicians and other leaders have used William and the events of his reign to illustrate political events throughout English history. During the reign of Queen Elizabeth I of England, Archbishop Matthew Parker saw the Conquest as having corrupted a purer English Church, which Parker attempted to restore. During the 17th and 18th centuries, some historians and lawyers saw William's reign as imposing a "Norman yoke" on the native Anglo-Saxons, an argument that continued during the 19th century with further elaborations along nationalistic lines. These controversies have led to William being seen by some historians either as one of the creators of England's greatness or as inflicting one of the greatest defeats in English history. Others have viewed him as an enemy of the English constitution, or alternatively as its creator.[146]

Family and children

William and his wife Matilda had at least nine children.[48] The birth order of the sons is clear, but no source gives the relative order of birth of the daughters.[2]

- Robert was born between 1051 and 1054, died on 10 February 1134.[48] Duke of Normandy, married Sybilla, daughter of Geoffrey, Count of Conversano.[147]

- Richard was born before 1056, died around 1075.[48]

- William was born between 1056 and 1060, died on 2 August 1100.[48] King of England, killed in the New Forest.[148]

- Henry was born in late 1068, and died on 1 December 1135.[48] King of England, married Edith, daughter of Malcolm III of Scotland. His second wife was Adeliza of Louvain.[149]

- Adeliza (or Adelida,[150] Adelaide[149]) died before 1113, reportedly betrothed to Harold Godwinson, probably a nun of Saint Léger at Préaux.[150]

- Cecilia (or Cecily) was born before 1066, died 1127, Abbess of Holy Trinity, Caen.[48]

- Matilda[2][150] was born around 1061, died perhaps about 1086.[149] Mentioned in Domesday Book as a daughter of William.[48]

- Constance died 1090, married Alan IV, Duke of Brittany.[48]

- Adela died 1137, married Stephen, Count of Blois.[48]

- (Possibly) Agatha, the betrothed of Alfonso VI of León and Castile.[x]

There is no evidence of any illegitimate children born to William.[154]

Notes

- William of Poitiers relates that two brothers, Iberian kings, were competitors for the hand of a daughter of William, which led to a dispute between them.[151] Some historians have identified these as Sancho II of Castile and his brother García II of Galicia, and the bride as Sancho's documented wife Alberta, who bears a non-Iberian name.[152] The anonymous vita of Simon de Crépy instead makes the competitors Alfonso VI of León and Robert Guiscard, while William of Malmesbury and Orderic Vitalis both show a daughter of William to have been betrothed to Alfonso "king of Galicia" but to have died before the marriage. In his Historia Ecclesiastica, Orderic specifically names her as Agatha, "former fiancee of Harold".[151][152] This conflicts with Orderic's own earlier additions to the Gesta Normannorum Ducum, where he instead named Harold's fiance as William's daughter, Adelidis.[150] Recent accounts of the complex marital history of Alfonso VI have accepted that he was betrothed to a daughter of William named Agatha,[151][152][153] while Douglas dismisses Agatha as a confused reference to known daughter Adeliza.[48] Elisabeth van Houts is non-committal, being open to the possibility that Adeliza was engaged before becoming a nun, but also accepting that Agatha may have been a distinct daughter of William.[150]

Citations

- Given-Wilson and Curteis Royal Bastards p. 59

References

- Barlow, Frank (2004). "Edward (St Edward; known as Edward the Confessor) (1003x5–1066)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/8516. Retrieved 16 May 2012. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Barlow, Frank (1979). The English Church 1066–1154: A History of the Anglo-Norman Church. New York: Longman. ISBN 0-582-50236-5.

- Barlow, Frank (2004). "William II (c.1060–1100)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/29449. Retrieved 29 June 2012. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Bates, David (2001). William the Conqueror. Kings and Queens of Medieval England. Stroud, UK: Tempus. ISBN 0-7524-1980-3.

- Bates, David (2004). "William I (known as William the Conqueror)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/29448. Retrieved 26 March 2012. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Canal Sánchez-Pagín, José María (2020). "Jimena Muñoz, Amiga de Alfonso VI". Anuario de Estudios Medievales (in Spanish). 21: 11–40. doi:10.3989/aem.1991.v21.1103.

- Carpenter, David (2004). The Struggle for Mastery: The Penguin History of Britain 1066–1284. New York: Penguin. ISBN 0-14-014824-8.

- Clanchy, M. T. (2006). England and its Rulers: 1066–1307. Blackwell Classic Histories of England (Third ed.). Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 1-4051-0650-6.

- Collins, Roger (1999). Early Medieval Europe: 300–1000 (Second ed.). New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-21886-9.

- Crouch, David (2005). The Birth of Nobility: Constructing Aristocracy in England and France, 900–1300. New York: Longman. ISBN 0-582-36981-9.

- Douglas, David C. (1964). William the Conqueror: The Norman Impact Upon England. Berkeley: University of California Press. OCLC 399137.

- Douglas, David C.; Greenaway, G. W. (1981). English Historical Documents, 1042–1189. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-203-43951-1.

- Fryde, E. B.; Greenway, D. E.; Porter, S.; Roy, I. (1996). Handbook of British Chronology (Third revised ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-56350-X.

- Given-Wilson, Chris; Curteis, Alice (1995). The Royal Bastards of Medieval England. New York: Barnes & Noble. ISBN 1-56619-962-X.

- Huscroft, Richard (2009). The Norman Conquest: A New Introduction. New York: Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-1155-2.

- Huscroft, Richard (2005). Ruling England 1042–1217. London: Pearson/Longman. ISBN 0-582-84882-2.

- Lawson, M. K. (2002). The Battle of Hastings: 1066. Stroud, UK: Tempus. ISBN 0-7524-1998-6.

- Lewis, C. P. (2004). "Breteuil, Roger de, earl of Hereford (fl. 1071–1087)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/9661. Retrieved 25 June 2012. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Marren, Peter (2004). 1066: The Battles of York, Stamford Bridge & Hastings. Battleground Britain. Barnsley, UK: Leo Cooper. ISBN 0-85052-953-0.

- Miller, Sean (2001). "Ætheling". In Lapidge, Michael; Blair, John; Keynes, Simon; Scragg, Donald (eds.). Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Anglo-Saxon England. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. pp. 13–14. ISBN 978-0-631-22492-1.

- Pettifer, Adrian (1995). English Castles: A Guide by Counties. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell. ISBN 0-85115-782-3.

- Reilly, Bernard F. (1988). The Kingdom of Leon-Castile Under Alfonso VI. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-05515-2.

- Rex, Peter (2005). Harold II: The Doomed Saxon King. Stroud, UK: Tempus. ISBN 978-0-7394-7185-2.

- Salazar y Acha, Jaime de (1992–1993). "Contribución al estudio del reinado de Alfonso VI de Castilla: algunas aclaraciones sobre su política matrimonial". Anales de la Real Academia Matritense de Heráldica y Genealogía (in Spanish). 2: 299–336.

- Searle, Eleanor (1988). Predatory Kinship and the Creation of Norman Power, 840–1066. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-06276-0.

- Thomas, Hugh (2007). The Norman Conquest: England after William the Conqueror. Critical Issues in History. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7425-3840-5.

- Thompson, Kathleen (2004). "Robert, duke of Normandy (b. in or after 1050, d. 1134)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/23715. Retrieved 3 April 2012. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Turner, Ralph V. (1998). "Richard Lionheart and the Episcopate in His French Domains". French Historical Studies. 21 (4 Autumn): 517–542. doi:10.2307/286806. JSTOR 286806. S2CID 159612172.

- van Houts, Elizabeth (2004). "Adelida (Adeliza) (d. before 1113)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/164. Retrieved 26 March 2012. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- van Houts, Elisabeth (2002). "Les femmes dans l'histoire du duché de Normandie (Women in the history of ducal Normandy)". Tabularia "Études" (in French) (2): 19–34. doi:10.4000/tabularia.1736. S2CID 193557186.

- Walker, Ian (2000). Harold the Last Anglo-Saxon King. Gloucestershire, UK: Wrens Park. ISBN 0-905778-46-4.

- "William the Conqueror". The Royal Family. London: the Royal Household. Retrieved 16 March 2023.

- Williams, Ann (2003). Æthelred the Unready: The Ill-Counselled King. London: Hambledon & London. ISBN 1-85285-382-4.

- Williams, Ann (2004). "Godwine, earl of Wessex (d. 1053)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/10887. Retrieved 27 May 2012. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Williams, Ann (2004). "Ralph, earl (d. 1097x9)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/11707. Retrieved 25 June 2012. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Young, Charles R. (1979). The Royal Forests of Medieval England. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0-8122-7760-0.

- William the Conqueror

- 1020s births

- 1087 deaths

- 11th-century French people

- 11th-century monarchs of England

- 11th-century Dukes of Normandy

- Anglo-Normans

- Norman warriors

- British monarchs buried abroad

- Deaths by horse-riding accident in France

- English people of French descent

- English Roman Catholics

- French Roman Catholics

- House of Normandy

- Medieval child monarchs

- Norman conquest of England

- People from Falaise, Calvados

- Tower of London

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_the_Conqueror

Château de Falaise in Falaise, Lower Normandy, France; William was born in an earlier building here.

Diagram showing William's family relationships. Names with "---" under them were opponents of William, and names with "+++" were supporters of William. Some relatives switched sides over time, and are marked with both symbols.

Column at the site of the Battle of Val-ès-Dunes

Image from the Bayeux Tapestry showing William with his half-brothers. William is in the centre, Odo is on the left with empty hands, and Robert is on the right with a sword in his hand.

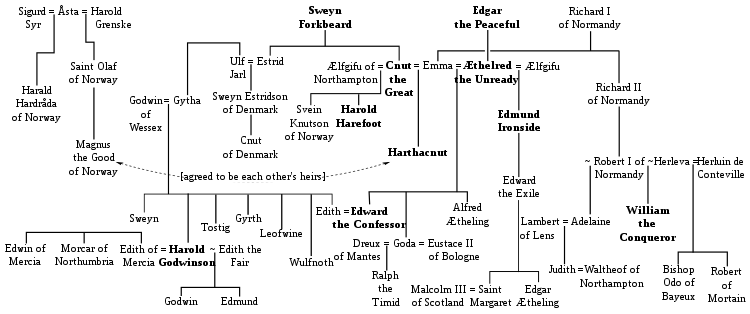

Family relationships of the claimants to the English throne in 1066, and others involved in the struggle. Kings of England are shown in bold.

The signatures of William I and Matilda are the first two large crosses on the Accord of Winchester from 1072.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_the_Conqueror

Roger I of Mortemer (Roger de Mortemer, Roger de Mortimer, Roger Mortimer) (fl.1054 [1] - aft. 1078), founded the abbey of St. Victor en Caux[2] in the Pays de Caux of Upper Normandy as early as 1074 CE.[3] Roger claimed the castle of Wigmore, Herefordshire that was built by William FitzOsbern, 1st Earl of Hereford. This castle became the chief barony of Roger's descendants.[4] He was the first Norman ancestor to assume the name Mortimer,[2] as in the place-name Mortemer-en-Brai, the land on which the village and castle was located.[1]

Background

Castle in Mortemer

In 1054, the territory of Évreux was invaded by French armies led by Odo, the brother of King Henry I of France.[2] In response, Duke William II of Normandy sent his general Roger "fili Episcopi", along with other commanders, to oppose Odo’s forces. They met at the castle in Mortemer, Seine-Maritime where the battle of Mortemer ensued.[5] Roger was victorious against Odo, with Guy Comte de Ponthieu taken prisoner. Roger then took possession of the castle in Mortemer and assumed its name. However, his hold on the property was short lived due to a breach of duty to Duke William.[4] Roger had entertained an enemy of the Duke,[3] who was a French operative known as Count Ralph III “the Great”.[4] Count Ralph was Roger’s father-in-law,[6] and thus gave the Count shelter for three days at his castle in Mortemer until he was able to safely return to his own territories. Upon discovering the news that Roger was providing safe haven for an enemy, Duke William banished Roger from Normandy and confiscated his possessions, giving them to his nephew, William de Warenne.[4] Eventually, Roger was pardoned by the Duke, but was never able to retain the castle in Mortemer.[7] It wasn’t until Roger’s son, Ranulph de Mortemer, was able to repossess the property by grant of Duke William. He is last seen in a document dated between 1078 and 1080.[8]

Family

The origin of Roger of Mortemer has been subject to much scholarly debate. Only two early sources provide information. Orderic Vitalis calls William de Warenne consanguineo ejus (his cousin/kinsman), while Robert de Torigny confusingly provides three different versions of his parentage that, though inconsistent, all make him either brother or son, of William de Warenne. Historian Thomas Stapleton would identify him with Roger filius Episcopi (bishop's son), who was child of Hugh, bishop of Coutances, and he makes Rodulf de Warenne another son of Hugh, thus making Roger de Mortimer uncle of William de Warenne.

However, L.C. Loyd showed that the two Rogers were distinct, and that Radulf, though related to Roger filius Episcopi, was not his brother. Loyd points to a Rogeri filii Radulfi de Warethna (Roger, son of Rodulf de Warenne) who appears in a pair of charters from the 1040s. Loyd was hesitant to connect them because William de Warenne was thought to have been son of this Rodulf, but evidence indicates he was not Roger's brother.[9]

Katherine Keats-Rohan concluded that two Rodulfs were mistakenly combined into one, and that Roger was son of Rodulf (I) de Warenne and his wife Beatrice, while William de Warenne was his nephew, son of Rodulf (II) and Emma, and as this removes many of Loyd's concerns, she identifies Roger de Mortimer with Roger, son of Rodulf.[10] C.P. Lewis calls this hypothesis the "most plausible" solution.[8] Robert de Torigny called Roger's mother, who is not named, one of the nieces of Gunnor, Duchess of Normandy. This would seemingly make Beatrice that niece. Keats-Rohan identifies her with a later widow, Beatrice, daughter of Tesselin, vicomte of Rouen.[10]

Roger married Hadewisa, a Lady who inherited the Mers-les-Bains on the river mouth of Bresle and the district of Vimeu. Her father might have been Ralph III "The Great", Count of Amiens.[3] Roger and Hadewisa had at least three children: Ranulph, Hugh, and William.[citation needed]

References

- Planché, J.R. On the Genealogy and Armorial Bearings of the Family of Mortimer, Journal of the British Archaeological Association, 1868, p. 21-27

- K. S. B. Keats-Rohan, "Aspects of Torigny's Genealogy Revisited", Nottingham Medieval Studies 37: 21–27

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roger_of_Mortemer

| Gunnor | |

|---|---|

Gunnor

confirming a charter of the abbey of the Mount-Saint-Michel, 12th

century (from archive of the abbey). Here she attested using her title

of countess.[1] | |

| Duchess consort of Normandy | |

| Tenure | 989–996 |

| Born | c. 936 - 950 Not known |

| Died | c. 1031- Uncertain Normandy, France |

| Spouse | Richard I, Duke of Normandy |