| Offa | |

|---|---|

A coin depicting Offa with the inscription Offa Rex Mercior[um] (Offa King of Mercia) | |

| King of Mercia | |

| Reign | 757 – 29 July 796 |

| Predecessor | Beornred |

| Successor | Ecgfrith |

| Died | 29 July 796 |

| Burial | |

| Spouse | Cynethryth |

| Issue Detail | |

| House | Iclingas |

| Father | Thingfrith |

Offa (died 29 July 796 AD) was King of Mercia, a kingdom of Anglo-Saxon England, from 757 until his death. The son of Thingfrith and a descendant of Eowa, Offa came to the throne after a period of civil war following the assassination of Æthelbald. Offa defeated the other claimant, Beornred. In the early years of Offa's reign, it is likely that he consolidated his control of Midland peoples such as the Hwicce and the Magonsæte. Taking advantage of instability in the kingdom of Kent to establish himself as overlord, Offa also controlled Sussex by 771, though his authority did not remain unchallenged in either territory. In the 780s he extended Mercian Supremacy over most of southern England, allying with Beorhtric of Wessex, who married Offa's daughter Eadburh, and regained complete control of the southeast. He also became the overlord of East Anglia and had King Æthelberht II of East Anglia beheaded in 794, perhaps for rebelling against him.

Offa was a Christian king who came into conflict with the Church, particularly with Jænberht, the Archbishop of Canterbury. Offa persuaded Pope Adrian I to divide the archdiocese of Canterbury in two, creating a new archdiocese of Lichfield. This reduction in the power of Canterbury may have been motivated by Offa's desire to have an archbishop consecrate his son Ecgfrith as king, since it is possible Jænberht refused to perform the ceremony, which took place in 787. Offa had a dispute with the Bishop of Worcester, which was settled at the Council of Brentford in 781.

Many surviving coins from Offa's reign carry elegant depictions of him, and the artistic quality of these images exceeds that of the contemporary Frankish coinage. Some of his coins carry images of his wife, Cynethryth—the only Anglo-Saxon queen ever depicted on a coin. Only three gold coins of Offa's have survived: one is a copy of an Abbasid dinar of 774 and carries Arabic text on one side, with "Offa Rex" on the other. The gold coins are of uncertain use but may have been struck to be used as alms or for gifts to Rome.

Many historians regard Offa as the most powerful Anglo-Saxon king before Alfred the Great. His dominance never extended to Northumbria, though he gave his daughter Ælfflæd in marriage to the Northumbrian king Æthelred I in 792. Historians once saw his reign as part of a process leading to a unified England, but this is no longer the majority view: in the words of historian Simon Keynes, "Offa was driven by a lust for power, not a vision of English unity; and what he left was a reputation, not a legacy."[1] His son Ecgfrith succeeded him after his death, but reigned for less than five months before Coenwulf of Mercia became king.

Background and sources

In the first half of the 8th century, the dominant Anglo-Saxon ruler was King Æthelbald of Mercia, who by 731 had become the overlord of all the provinces south of the River Humber.[2] Æthelbald was one of a number of strong Mercian kings who ruled from the mid-7th century to the early 9th, and it was not until the reign of Egbert of Wessex in the 9th century that Mercian power began to wane.[3]

The power and prestige that Offa attained made him one of the most significant rulers in Early Medieval Britain,[4] though no contemporary biography of him survives.[3] A key source for the period is the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, a collection of annals in Old English narrating the history of the Anglo-Saxons. The Chronicle was a West Saxon production, however, and is sometimes thought to be biased in favour of Wessex; hence it may not accurately convey the extent of power achieved by Offa, a Mercian.[5] That power can be seen at work in charters dating from Offa's reign. Charters were documents which granted land to followers or to churchmen and were witnessed by the kings who had the authority to grant the land.[6][7] A charter might record the names of both a subject king and his overlord on the witness list appended to the grant. Such a witness list can be seen on the Ismere Diploma, for example, where Æthelric, son of king Oshere of the Hwicce, is described as a "subregulus", or subking, of Æthelbald's.[8][9] The eighth-century monk and chronicler the Venerable Bede wrote a history of the English church called Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum; the history only covers events up to 731, but as one of the major sources for Anglo-Saxon history it provides important background information for Offa's reign.[10]

Offa's Dyke, most of which was probably built in his reign, is a testimony to the extensive resources Offa had at his command and his ability to organise them.[11] Other surviving sources include a problematic document known as the Tribal Hidage, which may provide further evidence of Offa's scope as a ruler, though its attribution to his reign is disputed.[12] A significant corpus of letters dates from the period, especially from Alcuin, an English deacon and scholar who spent over a decade at Charlemagne's court as one of his chief advisors, and corresponded with kings, nobles and ecclesiastics throughout England.[13] These letters in particular reveal Offa's relations with the continent, as does his coinage, which was based on Carolingian examples.[14][15]

Ancestry and family

Offa's ancestry is given in the Anglian collection, a set of genealogies that include lines of descent for four Mercian kings. All four lines descend from Pybba, who ruled Mercia early in the 7th century. Offa's line descends through Pybba's son Eowa and then through three more generations: Osmod, Eanwulf and Offa's father, Thingfrith. Æthelbald, who ruled Mercia for most of the forty years before Offa, was also descended from Eowa according to the genealogies: Offa's grandfather, Eanwulf, was Æthelbald's first cousin.[16] Æthelbald granted land to Eanwulf in the territory of the Hwicce, and it is possible that Offa and Æthelbald were from the same branch of the family. In one charter Offa refers to Æthelbald as his kinsman, and Headbert, Æthelbald's brother, continued to witness charters after Offa rose to power.[17][18]

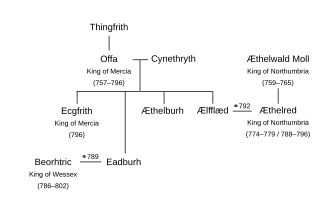

Offa's wife was Cynethryth, whose ancestry is unknown. The couple had a son, Ecgfrith, and at least three daughters: Ælfflæd, Eadburh and Æthelburh.[19] It has been speculated that Æthelburh was the abbess who was a kinswoman of King Ealdred of the Hwicce, but there are other prominent women named Æthelburh during that period.[18]

Early reign, the midland territories and the Middle and East Saxons

Æthelbald, who had ruled Mercia since 716, was assassinated in 757. According to a later continuation of Bede's Historia Ecclesiastica (written anonymously after Bede's death) the king was "treacherously murdered at night by his own bodyguards", though the reason why is unrecorded. Æthelbald was initially succeeded by Beornred, about whom little is known. The continuation of Bede comments that Beornred "ruled for a little while, and unhappily", and adds that "the same year, Offa, having put Beornred to flight, sought to gain the kingdom of the Mercians by bloodshed."[20] It is possible that Offa did not gain the throne until 758, however, since a charter of 789 describes Offa as being in the thirty-first year of his reign.[18]

The conflict over the succession suggests that Offa needed to re-establish control over Mercia's traditional dependencies, such as the Hwicce and the Magonsæte. Charters dating from the first two years of Offa's reign show the Hwiccan kings as reguli, or kinglets, under his authority; and it is likely that he was also quick to gain control over the Magonsæte, for whom there is no record of an independent ruler after 740.[1][18][21] Offa was probably able to exert control over the kingdom of Lindsey at an early date, as it appears that the independent dynasty of Lindsey had disappeared by this time.[1][22]

Little is known about the history of the East Saxons during the 8th century, but what evidence there is indicates that both London and Middlesex, which had been part of the kingdom of Essex, were finally brought under Mercian control during the reign of Æthelbald. Both Æthelbald and Offa granted land in Middlesex and London as they wished; in 767 a charter of Offa's disposed of land in Harrow without a local ruler as witness.[23] It is likely that both London and Middlesex were quickly under Offa's control at the start of his reign.[24] The East Saxon royal house survived the 8th century, so it is probable that the kingdom of Essex retained its native rulers, but under strong Mercian influence, for most or all of the 8th century.[25]

It is unlikely that Offa had significant influence in the early years of his reign outside the traditional Mercian heartland. The overlordship of the southern English which had been exerted by Æthelbald appears to have collapsed during the civil strife over the succession, and it is not until 764, when evidence emerges of Offa's influence in Kent, that Mercian power can be seen expanding again.[26]

Kent and Sussex

Offa appears to have exploited an unstable situation in Kent after 762.[27] Kent had a long tradition of joint kingship, with east and west Kent under separate kings, though one king was typically dominant.[28] Prior to 762 Kent was ruled by Æthelberht II and Eadberht I; Eadberht's son Eardwulf is also recorded as a king. Æthelberht died in 762, and Eadberht and Eardwulf are last mentioned in that same year. Charters from the next two years mention other kings of Kent, including Sigered, Eanmund and Heahberht. In 764, Offa granted land at Rochester in his own name, with Heahberht on the witness list as king of Kent. Another king of Kent, Ecgberht, appears on a charter in 765 along with Heahberht; the charter was subsequently confirmed by Offa.[29] Offa's influence in Kent at this time is clear, and it has been suggested that Heahberht was installed by Offa as his client.[27] There is less agreement among historians on whether Offa had general overlordship of Kent thereafter. He is known to have revoked a charter of Ecgberht's on the grounds that "it was wrong that his thegn should have presumed to give land allotted to him by his lord into the power of another without his witness", but the date of Ecgberht's original grant is unknown, as is the date of Offa's revocation of it.[30] It may be that Offa was the effective overlord of Kent from 764 until at least 776. The limited evidence for Offa's direct involvement in the kingdom between 765 and 776 includes two charters of 774 in which he grants land in Kent; but there are doubts about their authenticity, so Offa's intervention in Kent prior to 776 may have been limited to the years 764–65.[31]

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records that "the Mercians and the inhabitants of Kent fought at Otford" in 776, but does not give the outcome of the battle. It has traditionally been interpreted as a Mercian victory, but there is no evidence for Offa's authority over Kent until 785: a charter from 784 mentions only a Kentish king named Ealhmund, which may indicate that the Mercians were in fact defeated at Otford.[32] The cause of the conflict is also unknown: if Offa was ruling Kent before 776, the battle of Otford was probably a rebellion against Mercian control.[1] However, Ealhmund does not appear again in the historical record, and a sequence of charters by Offa from the years 785–89 makes his authority clear. During these years he treated Kent "as an ordinary province of the Mercian kingdom",[33] and his actions have been seen as going beyond the normal relation of overlordship and extending to the annexation of Kent and the elimination of a local royal line. After 785, in the words of one historian, "Offa was the rival, not the overlord, of Kentish kings".[34] Mercian control lasted until 796, the year of Offa's death, when Eadberht Præn was temporarily successful in regaining Kentish independence.[35]

Ealhmund was probably the father of Egbert of Wessex, and it is possible that Offa's interventions in Kent in the mid-780s are connected to the subsequent exile of Egbert to Francia. The Chronicle claims that when Egbert invaded Kent in 825, the men of the southeast turned to him "because earlier they were wrongly forced away from his relatives".[36] This is likely to be an allusion to Ealhmund, and may imply that Ealhmund had a local overlordship of the southeastern kingdoms. If so, Offa's intervention was probably intended to gain control of this relationship and take over the dominance of the associated kingdoms.[37]

The evidence for Offa's involvement in the kingdom of Sussex comes from charters, and as with Kent there is no clear consensus among historians on the course of events. What little evidence survives that bears on Sussex's kings indicates that several kings ruled at once, and it may never have formed a single kingdom. It has been argued that Offa's authority was recognised early in his reign by local kings in western Sussex, but that eastern Sussex (the area around Hastings) submitted to him less readily. Symeon of Durham, a twelfth-century chronicler, records that in 771 Offa defeated "the people of Hastings", which may record the extension of Offa's dominion over the entire kingdom.[38] However, doubts have been expressed about the authenticity of the charters which support this version of events, and it is possible that Offa's direct involvement in Sussex was limited to a short period around 770–71. After 772, there is no further evidence of Mercian involvement in Sussex until c. 790, and it may be that Offa gained control of Sussex in the late 780s, as he did in Kent.[39]

East Anglia, Wessex and Northumbria

In East Anglia, Beonna probably became king in about 758. Beonna's first coinage predates Offa's own, and implies independence from Mercia. Subsequent East Anglian history is quite obscure, but in 779 Æthelberht II became king, and was independent long enough to issue coins of his own.[40] In 794, according to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, "King Offa ordered King Æthelberht's head to be struck off". Offa minted pennies in East Anglia in the early 790s, so it is likely that Æthelberht rebelled against Offa and was beheaded as a result.[41] Accounts of the event have survived in which Aethelberht is killed through the machinations of Offa's wife Cynethryth, but the earliest manuscripts in which these possibly legendary accounts are found date from the 11th and 12th centuries, and recent historians do not regard them with confidence.[42] The legend also claims that Æthelberht was killed at Sutton St. Michael and buried four miles (6 km) to the south at Hereford, where his cult flourished, becoming at one time second only to Canterbury as a pilgrimage destination.[43][44]

To the south of Mercia, Cynewulf came to the throne of Wessex in 757 and recovered much of the border territory that Æthelbald had conquered from the West Saxons. Offa won an important victory over Cynewulf at the Battle of Bensington (in Oxfordshire) in 779, reconquering some of the land along the Thames.[45] No indisputably authentic charters from before this date show Cynewulf in Offa's entourage,[37] and there is no evidence that Offa ever became Cynewulf's overlord.[45] In 786, after the murder of Cynewulf, Offa may have intervened to place Beorhtric on the West Saxon throne. Even if Offa did not assist Beorhtric's claim, it seems likely that Beorhtric to some extent recognised Offa as his overlord shortly thereafter.[45][46] Offa's currency was used across the West Saxon kingdom, and Beorhtric had his own coins minted only after Offa's death.[47] In 789, Beorhtric married Eadburh, a daughter of Offa;[46] the Chronicle records that the two kings combined to exile Egbert to Francia for "three years", adding that "Beorhtric helped Offa because he had his daughter as his queen".[48] Some historians believe that the Chronicle's "three years" is an error, and should read "thirteen years", which would mean Egbert's exile lasted from 789 to 802, but this reading is disputed.[49] Eadburh is mentioned by Asser, a 9th-century monk who wrote a biography of Alfred the Great: Asser says that Eadburh had "power throughout almost the entire kingdom", and that she "began to behave like a tyrant after the manner of her father".[50] Whatever power she had in Wessex was no doubt connected with her father's overlordship.[51]

If Offa did not gain the advantage in Wessex until defeating Cynewulf in 779, it may be that his successes south of the river were a necessary prerequisite to his interventions in the south-east. In this view, Egbert of Kent's death in about 784 and Cynewulf's death in 786 were the events that allowed Offa to gain control of Kent and bring Beorhtric into his sphere of influence. This version of events also assumes that Offa did not have control of Kent after 764–65, as some historians believe.[52]

Offa's marital alliances extended to Northumbria when his daughter Ælfflæd married Æthelred I of Northumbria at Catterick in 792.[53] However, there is no evidence that Northumbria was ever under Mercian control during Offa's reign.[1]

Wales and Offa's Dyke

Offa was frequently in conflict with the various Welsh kingdoms. There was a battle between the Mercians and the Welsh at Hereford in 760, and Offa is recorded as campaigning against the Welsh in 778, 784 and 796 in the tenth-century Annales Cambriae.[54][55]

The best known relic associated with Offa's time is Offa's Dyke, a great earthen barrier that runs approximately along the border between England and Wales. It is mentioned by the monk Asser in his biography of Alfred the Great: "a certain vigorous king called Offa ... had a great dyke built between Wales and Mercia from sea to sea".[56] The dyke has not been dated by archaeological methods, but most historians find no reason to doubt Asser's attribution.[57] Early names for the dyke in both Welsh and English also support the attribution to Offa.[58] Despite Asser's comment that the dyke ran "from sea to sea", it is now thought that the original structure only covered about two-thirds of the length of the border: in the north it ends near Llanfynydd, less than five miles (8 km) from the coast, while in the south it stops at Rushock Hill, near Kington in Herefordshire, less than fifty miles (80 km) from the Bristol Channel. The total length of this section is about 64 miles (103 km).[57] Other earthworks exist along the Welsh border, of which Wat's Dyke is one of the largest, but it is not possible to date them relative to each other and so it cannot be determined whether Offa's Dyke was a copy of or the inspiration for Wat's Dyke.[59]

The construction of the dyke suggests that it was built to create an effective barrier and to command views into Wales. This implies that the Mercians who built it were free to choose the best location for the dyke.[57] There are settlements to the west of the dyke that have names that imply they were English by the 8th century, so it may be that in choosing the location of the barrier the Mercians were consciously surrendering some territory to the native Britons.[60] Alternatively it may be that these settlements had already been retaken by the Welsh, implying a defensive role for the barrier. The effort and expense that must have gone into building the dyke are impressive, and suggest that the king who had it built (whether Offa or someone else) had considerable resources at his disposal. Other substantial construction projects of a similar date do exist, however, such as Wat's Dyke and Danevirke, in what is now Germany as well as such sites as Stonehenge from millennia earlier. The dyke can be regarded in the light of these counterparts as the largest and most recent great construction of the preliterate inhabitants of Britain.[61]

Church

Offa ruled as a Christian king, but despite being praised by Charlemagne's advisor, Alcuin, for his piety and efforts to "instruct [his people] in the precepts of God",[62] he came into conflict with Jænberht, the Archbishop of Canterbury. Jænberht had been a supporter of Ecgberht II of Kent, which may have led to conflict in the 760s when Offa is known to have intervened in Kent. Offa rescinded grants made to Canterbury by Egbert, and it is also known that Jænberht claimed the monastery of Cookham, which was in Offa's possession.[63]

In 786 Pope Adrian I sent papal legates to England to assess the state of the church and provide canons (ecclesiastical decrees) for the guidance of the English kings, nobles and clergy. This was the first papal mission to England since Augustine had been sent by Pope Gregory the Great in 597 to convert the Anglo-Saxons.[64] The legates were Bishop George of Ostia, and Theophylact, the bishop of Todi. They visited Canterbury first, and then were received by Offa at his court. Both Offa and Cynewulf, king of the West Saxons, attended a council where the goals of the mission were discussed. George then went to Northumbria, while Theophylact visited Mercia and "parts of Britain". A report on the mission, sent by the legates to Pope Adrian, gives details of a council held by George in Northumbria, and the canons issued there, but little detail survives of Theophylact's mission. After the northern council George returned to the south and another council was held, attended by both Offa and Jænberht, at which further canons were issued.[65]

In 787, Offa succeeded in reducing the power of Canterbury through the establishment of a rival archdiocese at Lichfield. The issue must have been discussed with the papal legates in 786, although it is not mentioned in the accounts that have survived. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle reports a "contentious synod" in 787 at Chelsea, which approved the creation of the new archbishopric. It has been suggested that this synod was the same gathering as the second council held by the legates, but historians are divided on this issue. Hygeberht, already Bishop of Lichfield, became the new archdiocese's first and only archbishop, and by the end of 788 he received the pallium, a symbol of his authority, from Rome.[66] The new archdiocese included the sees of Worcester, Hereford, Leicester, Lindsey, Dommoc and Elmham; these were essentially the midland Anglian territories. Canterbury retained the sees in the south and southeast.[67]

The few accounts of the creation of the new archbishopric date from after the end of Offa's reign. Two versions of the events appear in the form of an exchange of letters between Coenwulf, who became king of Mercia shortly after Offa's death, and Pope Leo III, in 798. Coenwulf asserts in his letter that Offa wanted the new archdiocese created out of enmity for Jænberht; but Leo responds that the only reason the papacy agreed to the creation was because of the size of the kingdom of Mercia.[68] Both Coenwulf and Leo had their own reasons for representing the situation as they did: Coenwulf was entreating Leo to make London the sole southern archdiocese, while Leo was concerned to avoid the appearance of complicity with the unworthy motives Coenwulf imputed to Offa. These are therefore partisan comments. However, both the size of Offa's territory and his relationship with Jænberht and Kent are indeed likely to have been factors in Offa's request for the creation of the new archdiocese.[69] Coenwulf's version has independent support, with a letter from Alcuin to Archbishop Æthelheard giving his opinion that Canterbury's archdiocese had been divided "not, as it seems, by reasonable consideration, but by a certain desire for power".[70] Æthelheard himself later said that the award of a pallium to Lichfield depended on "deception and misleading suggestion".[71]

Another possible reason for the creation of an archbishopric at Lichfield relates to Offa's son, Ecgfrith of Mercia. After Hygeberht became archbishop, he consecrated Ecgfrith as king; the ceremony took place within a year of Hygeberht's elevation.[72] It is possible that Jænberht refused to perform the ceremony, and that Offa needed an alternative archbishop for that purpose.[73] The ceremony itself is noteworthy for two reasons: it is the first recorded consecration of any English king, and it is unusual in that it asserted Ecgfrith's royal status while his father was still alive. Offa would have been aware that Charlemagne's sons, Pippin and Louis, had been consecrated as kings by Pope Adrian,[74] and probably wished to emulate the impressive dignity of the Frankish court.[75] Other precedents did exist: Æthelred of Mercia is said to have nominated his son Coenred as king during his lifetime, and Offa may have known of Byzantine examples of royal consecration.[73]

Despite the creation of the new archdiocese, Jænberht retained his position as the senior cleric in the land, with Hygeberht conceding his precedence.[76] When Jænberht died in 792, he was replaced by Æthelheard, who was consecrated by Hygeberht, now senior in his turn. Subsequently, Æthelheard appears as a witness on charters and presides at synods without Hygeberht, so it appears that Offa continued to respect Canterbury's authority.[77]

A letter from Pope Adrian to Charlemagne survives which makes reference to Offa, but the date is uncertain; it may be as early as 784 or as late as 791. In it Adrian recounts a rumour that had reached him: Offa had reportedly proposed to Charlemagne that Adrian should be deposed, and replaced by a Frankish pope. Adrian disclaims all belief in the rumour, but it is clear it had been a concern to him.[78] The enemies of Offa and Charlemagne, described by Adrian as the source of the rumour, are not named. It is unclear whether this letter is related to the legatine mission of 786; if it predates it, then the mission might have been partly one of reconciliation, but the letter might well have been written after the mission.[79]

Offa was a generous patron of the church, founding several churches and monasteries, often dedicated to St Peter.[80] Among these was St Albans Abbey, which he probably founded in the early 790s.[1] He also promised a yearly gift of 365 mancuses to Rome; a mancus was a term of account equivalent to thirty silver pennies, derived from Abbasid gold coins that were circulating in Francia at the time.[81] Control of religious houses was one way in which a ruler of the day could provide for his family, and to this end Offa ensured (by acquiring papal privileges) that many of them would remain the property of his wife or children after his death.[80] This policy of treating religious houses as worldly possessions represents a change from the early 8th century, when many charters showed the foundation and endowment of small minsters, rather than the assignment of those lands to laypeople. In the 770s, an abbess named Æthelburh (who may have been the same person as Offa's daughter of that name) held multiple leases on religious houses in the territory of the Hwicce; her acquisitions have been described as looking "like a speculator assembling a portfolio". Æthelburh's possession of these lands foreshadows Cynethryth's control of religious lands, and the pattern was continued in the early 9th century by Cwoenthryth, the daughter of King Coenwulf.[82]

Either Offa or Ine of Wessex is traditionally supposed to have founded the Schola Saxonum in Rome, in what is today the Roman rione, or district, of Borgo. The Schola Saxonum took its name from the militias of Saxons who served in Rome, but it eventually developed into a hostelry for English visitors to the city.[83]

European connections

Offa's diplomatic relations with Europe are well documented, but appear to belong only to the last dozen years of his reign.[78] In letters dating from the late 780s or early 790s, Alcuin congratulates Offa for encouraging education and greets Offa's wife and son, Cynethryth and Ecgfrith.[84][85] In about 789, or shortly before, Charlemagne proposed that his son Charles marry one of Offa's daughters, most likely Ælfflæd. Offa countered with a request that his son Ecgfrith should also marry Charlemagne's daughter Bertha: Charlemagne was outraged by the request, and broke off contact with Britain, forbidding English ships from landing in his ports. Alcuin's letters make it clear that by the end of 790 the dispute was still not resolved, and that Alcuin was hoping to be sent to help make peace. In the end diplomatic relations were restored, at least partly by the agency of Gervold, the abbot of St Wandrille.[86][87]

Charlemagne sought support from the English church at the council of Frankfurt in 794, where the canons passed in 787 at the Second Council of Nicaea were repudiated, and the heresies of two Spanish bishops, Felix and Elipandus, were condemned.[88] In 796 Charlemagne wrote to Offa; the letter survives and refers to a previous letter of Offa's to Charlemagne. This correspondence between the two kings produced the first surviving documents in English diplomatic history.[78] The letter is primarily concerned with the status of English pilgrims on the continent and with diplomatic gifts, but it reveals much about the relations between the English and the Franks.[86] Charlemagne refers to Offa as his "brother", and mentions trade in black stones, sent from the continent to England, and cloaks (or possibly cloths), traded from England to the Franks.[89] Charlemagne's letter also refers to exiles from England, naming Odberht, who was almost certainly the same person as Eadberht Praen, among them. Egbert of Wessex was another refugee from Offa who took shelter at the Frankish court. It is clear that Charlemagne's policy included support for elements opposed to Offa; in addition to sheltering Egbert and Eadberht he also sent gifts to Æthelred I of Northumbria.[90]

Events in southern Britain to 796 have sometimes been portrayed as a struggle between Offa and Charlemagne, but the disparity in their power was enormous. By 796 Charlemagne had become master of an empire which stretched from the Atlantic Ocean to the Great Hungarian Plain, and Offa and then Coenwulf were clearly minor figures by comparison.[91]

Government

The nature of Mercian kingship is not clear from the limited surviving sources. There are two main theories regarding the ancestry of Mercian kings of this period. One is that descendants of different lines of the royal family competed for the throne. In the mid-7th century, for example, Penda had placed royal kinsmen in control of conquered provinces.[92] Alternatively, it may be that a number of kin-groups with local power-bases may have competed for the succession. The sub-kingdoms of the Hwicce, the Tomsæte and the unidentified Gaini are examples of such power-bases. Marriage alliances could also have played a part. Competing magnates, those called in charters "dux" or "princeps" (that is, leaders), may have brought the kings to power. In this model, the Mercian kings are little more than leading noblemen.[93] Offa seems to have attempted to increase the stability of Mercian kingship, both by the elimination of dynastic rivals to his son Ecgfrith, and the reduction in status of his subject kings, sometimes to the rank of ealdorman.[94] He was ultimately unsuccessful, however; Ecgfrith only survived in power for a few months, and 9th century Mercia continued to draw its kings from multiple dynastic lines.[95]

There is evidence that Offa constructed a series of defensive burhs, or fortified towns; the locations are not generally agreed on but may include Bedford, Hereford, Northampton, Oxford and Stamford. In addition to their defensive uses, these burhs are thought to have been administrative centres, serving as regional markets and indicating a transformation of the Mercian economy away from its origins as a grouping of midland peoples. The burhs are forerunners of the defensive network successfully implemented by Alfred the Great a century later to deal with the Danish invasions.[96][97] However, Offa did not necessarily understand the economic changes that came with the burhs, so it is not safe to assume he envisioned all their benefits.[11] In 749, Æthelbald of Mercia had issued a charter that freed ecclesiastical lands from all obligations except the requirement to build forts and bridges – obligations which lay upon everyone, as part of the trinoda necessitas.[98][99] Offa's Kentish charters show him laying these same burdens on the recipients of his grants there, and this may be a sign that the obligations were being spread outside Mercia.[100][101] These burdens were part of Offa's response to the threat of "the pagan seaman".[102][103]

Offa issued laws in his name, but no details of them have survived. They are known only from a mention by Alfred the Great, in the preface to Alfred's own law code. Alfred says that he has included in his code those laws of Offa, Ine of Wessex and Æthelberht of Kent which he found "most just".[104] The laws may have been an independent lawcode, but it is also possible that Alfred is referring to the report of the legatine mission in 786, which issued statutes that the Mercians undertook to obey.[105]

Coinage

At the start of the 8th century, sceattas were the primary circulating coinage. These were small silver pennies, which often did not bear the name of either the moneyer or the king for whom they were produced. To contemporaries these were probably known as pennies, and are the coins referred to in the laws of Ine of Wessex.[106][107][108] This light coinage (in contrast to the heavier coins minted later in Offa's reign) can probably be dated to the late 760s and early 770s. A second, medium-weight coinage can be identified before the early 790s.[109] These new medium-weight coins were heavier, broader and thinner than the pennies they replaced,[106] and were prompted by the contemporary Carolingian currency reforms.[84] The new pennies almost invariably carried both Offa's name and the name of the moneyer from whose mint the coins came.[106] The reform in the coinage appears to have extended beyond Offa's own mints: the kings of East Anglia, Kent and Wessex all produced coins of the new heavier weight in this period.[110]

Some coins from Offa's reign bear the names of the archbishops of Canterbury, Jænberht and, after 792, Æthelheard. Jænberht's coins all belong to the light coinage, rather than the later medium coinage. There is also evidence that coins were issued by Eadberht, who was Bishop of London in the 780s and possibly before. Offa's dispute with Jænberht may have led him to allow Eadberht coining rights, which may then have been revoked when the see of Lichfield was elevated to an archbishopric.[111]

The medium-weight coins often carry designs of high artistic quality, exceeding that of the contemporary Frankish currency.[109] Coin portraits of Offa have been described as "showing a delicacy of execution which is unique in the whole history of the Anglo-Saxon coinage".[81] The depictions of Offa on the coins include a "striking and elegant" portrait showing him with his hair in voluminous curls, and another where he wears a fringe and tight curls. Some coins show him wearing a necklace with a pendant. The variety of these depictions implies that Offa's die-cutters were able to draw on varied artistic sources for their inspiration.[112]

Offa's wife Cynethryth was the only Anglo-Saxon queen ever named or portrayed on coinage, in a remarkable series of pennies struck by the moneyer Eoba.[113] These were probably derived from contemporary coins from the reign of the Byzantine emperor Constantine VI, who minted a series showing a portrait of his mother, the later Empress Irene,[114] though the Byzantine coins show a frontal bust of Irene rather than a profile, and so cannot have been a direct model.[115]

Around the time of Jænberht's death and replacement with Æthelheard in 792–93, the silver currency was reformed a second time: in this "heavy coinage" the weight of the pennies was increased again, and a standardised non-portrait design was introduced at all mints. None of Jænberht's or Cynethryth's coins occur in this coinage, whereas all of Æthelheard's coins are of the new, heavier weight.[116]

There are also surviving gold coins from Offa's reign. One is a copy of an Abbasid dinar struck in 774 by Caliph Al-Mansur,[117] with "Offa Rex" centred on the reverse. It is clear that the moneyer had no understanding of Arabic as the Arabic text contains many errors. The coin may have been produced to trade with Islamic Spain; or it may be part of the annual payment of 365 mancuses that Offa promised to Rome.[118] There are other Western copies of Abbasid dinars of the period, but it is not known whether they are English or Frankish. Two other English gold coins of the period survive, from two moneyers, Pendraed and Ciolheard: the former is thought to be from Offa's reign but the latter may belong either to Offa's reign or to that of Coenwulf, who came to the throne in 796. Nothing definite is known about their use, but they may have been struck to be used as alms.[119][120]

Although many of the coins bear the name of a moneyer, there is no indication of the mint where each coin was struck. As a result, the number and location of mints used by Offa is uncertain. Current opinion is that there were four mints, in Canterbury, Rochester, East Anglia and London.[119]

Stature

The title Offa used on most of his charters was "rex Merciorium", or "king of the Mercians", though this was occasionally extended to "king of the Mercians and surrounding nations".[121] Some of his charters use the title "Rex Anglorum," or "King of the English," and this has been seen as a sweeping statement of his power. There is debate on this point, however, as several of the charters in which Offa is named "Rex Anglorum" are of doubtful authenticity. They may represent later forgeries of the 10th century, when this title was standard for kings of England.[67] The best evidence for Offa's use of this title comes from coins, not charters: there are some pennies with "Of ℞ A" inscribed, but it is not regarded as definite that this stood for "Offa Rex Anglorum."[111]

In Anglo-Saxon England, Stenton argued that Offa was perhaps the greatest king of the English kingdoms, commenting that "no other Anglo-Saxon king ever regarded the world at large with so ... acute a political sense".[122] Many historians regard Offa's achievements as second only to Alfred the Great among the Anglo-Saxon kings.[123] Offa's reign has sometimes been regarded as a key stage in the transition to a unified England, but this is no longer the general view among historians in the field. In the words of Simon Keynes, "Offa was driven by a lust for power, not a vision of English unity; and what he left was a reputation, not a legacy."[1] It is now believed that Offa thought of himself as "King of the Mercians," and that his military successes were part of the transformation of Mercia from an overlordship of midland peoples into a powerful and aggressive kingdom.[1][124]

Death and succession

Offa died on 29 July 796,[125][126][127][128] and may be buried in Bedford, though it is not clear that the "Bedeford" named in that charter was actually modern Bedford.[129][130] He was succeeded by his son, Ecgfrith of Mercia, but according to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle Ecgfrith died after a reign of only 141 days.[131] A letter written by Alcuin in 797 to a Mercian ealdorman named Osbert makes it apparent that Offa had gone to great lengths to ensure that his son Ecgfrith would succeed him. Alcuin's opinion is that Ecgfrith "has not died for his own sins; but the vengeance for the blood his father shed to secure the kingdom has reached the son. For you know very well how much blood his father shed to secure the kingdom on his son."[132] It is apparent that in addition to Ecgfrith's consecration in 787, Offa had eliminated dynastic rivals. This seems to have backfired, from the dynastic point of view, as no close male relatives of Offa or Ecgfrith are recorded, and Coenwulf, Ecgfrith's successor, was only distantly related to Offa's line.[133]

See also

References

- Yorke, Kings and Kingdoms, p. 118.

Sources

- Primary sources

- "Medieval Sourcebook: The Annales Cambriae (Annals of Wales)". Annales Cambriae. College of Staten Island, City University of New York. Retrieved 17 December 2007.

- Keynes, Simon; Lapidge, Michael (2004). Alfred the Great: Asser's Life of King Alfred and other contemporary sources. Penguin Classics. ISBN 0-14-044409-2.

- Bede (1991). D.H. Farmer (ed.). Ecclesiastical History of the English People. Translated by Leo Sherley-Price. Revised by R.E. Latham. London: Penguin. ISBN 0-14-044565-X.

- "Offa 7". Prosopography of Anglo-Saxon England. King's College London. Retrieved 6 April 2007.

- Swanton, Michael (1996). The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-92129-5.

- Swanton, Michael (2010). The Lives of Two Offas, Vitae Offarum Duorum. Crediton: The Medieval Press. ISBN 978-0-9557636-8-7.

- Whitelock, Dorothy (1968). English Historical Documents v. 1 c. 500–1042. London: Eyre & Spottiswoode.

- Secondary sources

- Abels, Richard, "Trinoda Necessitas", in Lapidge, Michael (1999). The Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Anglo-Saxon England. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 0-631-22492-0.

- Blackburn, Mark & Grierson, Philip, Medieval European Coinage. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, reprinted with corrections 2006. ISBN 0-521-03177-X

- Blair, John (2006). The Church in Anglo-Saxon Society. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-921117-5.

- Brown, Michelle P.; Farr, Carole A. (2001). Mercia: An Anglo-Saxon kingdom in Europe. Continuum. ISBN 0-8264-7765-8.

- Campbell, James (2000). The Anglo-Saxon State. Hambledon and London. ISBN 1-85285-176-7.

- Campbell, John; John, Eric; Wormald, Patrick (1991). The Anglo-Saxons. Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-014395-5.

- Featherstone, Peter, "The Tribal Hidage and the Ealdormen of Mercia", in Brown, Michelle P.; Farr, Carole A. (2001). Mercia: An Anglo-Saxon kingdom in Europe. Continuum. ISBN 0-8264-7765-8.

- Fletcher, Richard (1989). Who's Who in Roman Britain and Anglo-Saxon England. Shepheard-Walwyn. ISBN 0-85683-089-5.

- Gannon, Anna (2003). The Iconography of Early Anglo-Saxon Coinage: Sixth to Eighth Centuries. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-925465-6.

- Hunter Blair, Peter (1977). An Introduction to Anglo-Saxon England (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-29219-0.

- Hunter Blair, Peter (1966). Roman Britain and Early England: 55 B.C. – A.D. 871. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-00361-2.

- Kelly, S. E. (2007). "Offa (d. 796), king of the Mercians". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/20567. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Keynes, Simon, "Cynethryth", in Lapidge, Michael (1999). The Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Anglo-Saxon England. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 0-631-22492-0.

- idem, "Mercia", in Lapidge, Michael (1999). The Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Anglo-Saxon England. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 0-631-22492-0.

- idem, "Offa", in Lapidge, Michael (1999). The Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Anglo-Saxon England. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 0-631-22492-0.

- idem, "Mercia and Wessex in the Ninth Century", in Brown, Michelle P.; Farr, Carole A. (2001). Mercia: An Anglo-Saxon kingdom in Europe. Continuum. ISBN 0-8264-7765-8.

- Keynes, Simon; Lapidge, Michael (2004). Alfred the Great: Asser's Life of King Alfred and other contemporary sources. Penguin Classics. ISBN 0-14-044409-2.

- Kirby, D.P. (1992). The Earliest English Kings. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-09086-5.

- Lapidge, Michael, "Alcuin of York", in Lapidge, Michael (1999). The Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Anglo-Saxon England. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 0-631-22492-0.

- Lapidge, Michael (1999). The Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Anglo-Saxon England. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 0-631-22492-0.

- Nelson, Janet, "Carolingian Contacts", in Brown, Michelle P.; Farr, Carole A. (2001). Mercia: An Anglo-Saxon kingdom in Europe. Continuum. ISBN 0-8264-7765-8.

- Stafford, Pauline, "Political Women in Mercia, Eighth to Early Tenth Centuries", in Brown, Michelle P.; Farr, Carole A. (2001). Mercia: An Anglo-Saxon kingdom in Europe. Continuum. ISBN 0-8264-7765-8.

- Stenton, Frank M. (1971). Anglo-Saxon England. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-821716-1.

- Williams, Gareth, "Mercian Coinage and Authority", in Brown, Michelle P.; Farr, Carole A. (2001). Mercia: An Anglo-Saxon kingdom in Europe. Continuum. ISBN 0-8264-7765-8.

- idem, "Military Institutions and Royal Power", in Brown, Michelle P.; Farr, Carole A. (2001). Mercia: An Anglo-Saxon kingdom in Europe. Continuum. ISBN 0-8264-7765-8.

- Wormald, Patrick, "The Age of Offa and Alcuin", in Campbell, John; John, Eric; Wormald, Patrick (1991). The Anglo-Saxons. Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-014395-5.

- Wormald, Patrick; Bullough, D.; Collins, R. (1983). Ideal and Reality in Frankish and Anglo-Saxon Society. Oxford: B. Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-12661-9.

- Yorke, Barbara (1990). Kings and Kingdoms of Early Anglo-Saxon England. London: Seaby. ISBN 1-85264-027-8.

- Worthington, Margaret, "Offa's Dyke", in Lapidge, Michael (1999). The Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Anglo-Saxon England. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 0-631-22492-0.

- eadem, "Wat's Dyke", in Lapidge, Michael (1999). The Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Anglo-Saxon England. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 0-631-22492-0.

External links

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Offa_of_Mercia

| This article is part of a series on |

| the kings of Anglo-Saxon England |

|---|

|

The Kingdom of Mercia was a state in the English Midlands from the 6th century to the 10th century. For some two hundred years from the mid-7th century onwards it was the dominant member of the Heptarchy and consequently the most powerful of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms. During this period its rulers became the first English monarchs to assume such wide-ranging titles as King of Britain and King of the English.

Spellings varied widely in this period, even within a single document, and a number of variants exist for the names given below. For example, the sound th was usually represented with the Old English letters ð or þ.

For the Continental predecessors of the Mercians in Angeln, see List of kings of the Angles. For their successors see List of English monarchs.

Kings of the Mercians

The traditional rulers of Mercia were known as the Iclingas, descendants of the kings of the Angles. When the Iclingas became extinct in the male line, a number of other families, labelled B, C and W by historians, competed for the throne.[1]

All the following are kings, unless specified. Those in italics are probably legendary, are of dubious authenticity, or may not have reigned.

| Ruler | Reign | Biographical notes | Died |

|---|---|---|---|

| Icel | c. 515-c.535 | Son of Eomer, last King of the Angles in Angeln. Led his people across the North Sea to Britain. | c.535 |

| Cnebba | ? | Son of Icel. | ? |

| Cynewald | ? | Son of Cnebba. | ? |

| Creoda | c. 584–c. 593 | Son of Cynewald. Probable founder of the Mercian royal fortress at Tamworth. | c. 593 |

| Pybba | c. 593–c. 606 | Son of Creoda. Extended Mercian control into the western Midlands. | c. 606 |

| Cearl | c. 606–c. 626 | Named as king by Bede, not included in later regnal lists. | c. 626 |

| Penda | c. 626–655 | Son of Pybba. Raised Mercia to dominant status amongst the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms. Last pagan ruler of Mercia. Killed in battle by Oswiu of Northumbria. | 15 Nov 655 |

| Eowa | c. 635–642 | Son of Pybba. Co-ruler. Killed in battle. | 5 Aug 642 |

| Peada | c. 653–656 | Son of Penda. Co-ruler in the south-east Midlands. Murdered. | 17 Apr 656 |

| Oswiu of Northumbria | 655–658 | Briefly took direct control of Mercia after the death of Penda. Also King of Northumbria (655–670). | 15 Feb 670 |

| Wulfhere | 658–675 | Son of Penda. Restored Mercian dominance in England. First Christian king of all Mercia. | 675 |

| Æthelred I | 675–704 | Son of Penda. Abdicated and retired to a monastery at Bardney. | 716 |

| Cœnred | 704–709 | Son of Wulfhere. Abdicated and retired to Rome. | ? |

| Ceolred | 709–716 | Son of Æthelred I. Probably poisoned. | 716 |

| Ceolwald | 716 | Presumed son of Æthelred I (may not have existed). | 716 |

| Æthelbald | 716–757 | Grandson of Eowa. Proclaimed himself King of Britain in 736. Murdered by his bodyguards. | 757 |

| Beornred | 757 | No known relation to his predecessors. Deposed by Offa. | ? |

| Offa | 757–796 | Great-great-grandson of Eowa. The greatest and most powerful of all Mercian kings, he proclaimed himself King of the English in 774, built Offa's Dyke, and introduced the silver penny. | 29 Jul 796 |

| Ecgfrith | 787–796 | Son of Offa. Co-ruler, died suddenly a few months after his father. | 17 Dec 796 |

| Cœnwulf | 796–821 | Seventh generation descendant of Pybba, probably through a sister of Penda. Assumed the title of 'emperor'. | 821 |

| Cynehelm | c. 798–812 | Son of Cœnwulf. Although he existed, his status as co-ruler and his murder are legendary. Canonised (St Kenelm). | 812 |

| Ceolwulf I | 821–823 | Brother of Cœnwulf. Deposed by Beornwulf. | ? |

| Beornwulf | 823–826 | Conjectured kinsman of Beornred. Killed in battle against the East Anglians. | 826 |

| Ludeca | 826–827 | No known relation to his predecessors. Killed in battle against the East Anglians. | 827 |

| Wiglaf (1st reign) | 827–829 | No known relation to his predecessors. Deposed by Ecgberht of Wessex. | 839 |

| Ecgberht of Wessex | 829–830 | Briefly took direct control of Mercia after the deposition of Wiglaf. Also King of Wessex (802–839). | 4 Feb 839 |

| Wiglaf (2nd reign) | 830–839 | Restored. Although Mercia regained its independence, its dominance in England was lost. | 839 |

| Wigmund | c. 839–c. 840 | Son of Wiglaf and son-in-law of Ceolwulf I. Probably co-ruler. | c. 840 |

| Wigstan | 840 | Son of Wigmund. Declined the kingship and was later murdered by Beorhtwulf. Canonised (St Wystan). | 849 |

| Ælfflæd (Queen) | 840 | Daughter of Ceolwulf I, wife of Wigmund and mother of Wigstan. Appointed regent by Wigstan. | ? |

| Beorhtwulf | 840–852 | Claimed to be a cousin of Wigstan. Usurped the kingship and forced Ælfflæd to marry his son, Beorhtfrith. | 852 |

| Burgred | 852–874 | Conjectured kinsman of Beorhtwulf. Fled to Rome in the face of a Danish invasion. | ? |

| Ceolwulf II | 874–879 or c. 883 | Possibly a descendant of the C-dynasty, of which Ceolwulf I was a member, perhaps via intermarriage with W-dynasty. Lost eastern Mercia to the Danes in 877. | 879 |

| Æthelred II (Lord) | c. 883–911 | Recognised Alfred of Wessex as his overlord. Regarded as an 'ealdorman' by West Saxon sources. | 911 |

| Æthelflæd (Lady) | 911–918 | Wife of Æthelred and daughter of Alfred of Wessex. Possibly descended from earlier Mercian kings via her mother. With her brother, Edward the Elder, reconquered eastern Mercia. | 12 Jun 918 |

| Ælfwynn (Lady) | 918 | Daughter of Æthelred II and Æthelflæd. Deposed by her uncle, Edward the Elder, Dec 918, who annexed Mercia to Wessex. | ? |

Titular kings following Mercia's annexation

| Ruler | Reign | Biographical notes | Died |

|---|---|---|---|

| Æthelstan | 924 | Son of Edward the Elder and nephew of Æthelflæd. Became King of Mercia on Edward's death (Jul 924), and King of Wessex about 16 days later. | 27 Oct 939 |

| Eadgar | 957–959 | Nephew of Æthelstan. Seized control of Mercia and Northumbria in May 957, before succeeding to the reunited English throne in Oct 959. | 8 Jul 975 |

Ealdormen and Earls of the Mercians

The chief magnate of Mercia as an English province held the title of ealdorman until 1023/32, and earl thereafter. Both offices were royal appointments, but the latter in effect became hereditary.

| Ruler | Reign | Biographical notes | Died |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ælfhere | 957–983 | Appointed ealdorman of Mercia in 957 by Eadgar, when the English kingdom was disunited. | 983 |

| Ælfric Cild | 983–985 | Brother-in-law of Ælfhere. Deposed by Æthelred the Unready in 985. | ? |

| Wulfric Spot | ?–1004 | Possibly ealdorman of Mercia after the deposition of Ælfric Cild. | 22 Oct 1004 |

| Eadric Streona | 1007–1017 | Appointed by Æthelred. A notorious turncoat, he was later murdered by Cnut for his treachery. | 25 Dec 1017 |

| Leofwine | 1017–1023/32 | Possibly appointed by Cnut as ealdorman of Mercia, he was also ealdorman of the Hwicce. | 1023/32 |

| Leofric | 1023/32–1057 | Son of Leofwine, appointed by Cnut as earl. Chiefly remembered for his famous wife, Godgifu (Lady Godiva). | 31 Aug or 30 Sep 1057 |

| Ælfgar | 1057–1062 | Son of Leofric. Had previously been Earl of East Anglia until succeeding his father to Mercia. | 1062 |

| Eadwine | 1062–1071 | Son of Ælfgar. Submitted to William the Conqueror in 1066, but later rebelled, and was betrayed by his own men. Mercia was then broken up into smaller earldoms. | 1071 |

Earls of March

The title Earl of March (etymologically identical to 'Earl of Mercia') was created in the western Midlands for Roger Mortimer in 1328. It has fallen extinct, and been recreated, three times since then, and exists today as a subsidiary title of the Duke of Richmond and Lennox.

Kings of Mercia family tree

| Kings of Mercia family tree | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- Zaluckyj, Sarah & Feryok, Marge. Mercia: The Anglo-Saxon Kingdom of Central England (2001) ISBN 1-873827-62-8

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_monarchs_of_Mercia

The Connachta are a group of medieval Irish dynasties who claimed descent from the legendary High King Conn Cétchathach (Conn of the Hundred Battles). The modern western province of Connacht (Irish Cúige Chonnacht, province, literally "fifth", of the Connachta) takes its name from them, although the territories of the Connachta also included at various times parts of southern and western Ulster and northern Leinster. Their traditional capital was Cruachan (modern Rathcroghan, County Roscommon).[1]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Connachta

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/O%27Conor#Don

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/O%27Conor#Don

Key figures

Kings of Connacht

- Conchobar mac Taidg Mór 872–882

- Áed mac Conchobair 882–888

- Tadg mac Conchobair 888–900

- Cathal mac Conchobair 900–925

- Tadg mac Cathail 925–956

- Conchobar mac Tadg 967–973

- Cathal mac Tadg d. 973

- Cathal mac Conchobar mac Taidg 973–1010

- Ruaidrí na Saide Buide 1087–1092

- Tadg mac Ruaidrí Ua Conchobair d. 1097

- Domnall Ua Conchobair 1102–1106

- Tairrdelbach Ua Conchobair 1106–1156

- Ruaidrí Ua Conchobair 1156–1186

- Conchobar Máenmaige Ua Conchobhair 1186–1189

- Cathal Carragh Ua Conchobhair 1190–1202

- Cathal Crobderg Ua Conchobair 1202–1224

- Aedh Ua Conchobair 1224–1228

- Aedh mac Ruaidri Ua Conchobair 1228–1233

- Felim mac Cathal Crobderg Ua Conchobair 1233–1256

- Aedh Ó Conchobair 1256–1274

- Murtogh Moynagh O'Conor 1274–1280

- Magnus O'Conor 1288–1293

- Hugh McOwen O'Conor 1293–1309

- Ruaidri Ó Conchobair 1309–1310

- Felim McHugh O'Connor 1310–1316

- Rory na-bhFeadh Ó Conchobair 1316–1317

- Toirdelbach Ó Conchobair first reign 1317–1318 second reign, 1324–1350

- Cathal mac Domhnall Ó Conchobair 1318–1324

- Hugh McHugh Breifne O'Conor 1342; died 1350

- Aedh mac Tairdelbach Ó Conchobair

- Ruaidri mac Tairdelbach Ó Conchobair 1368–1384

Chiefs of the name

- Toirdhealbhach Óg Donn mac Aodha meic Toirdhealbhaigh, d. 9 December 1406.

- Cathal mac Ruaidhri Ó Conchobhair Donn, d. 19 March 1439.

- Aodh mac Toirdhealbhaigh Óig Ó Conchobhair Donn, d.15 May 1461.

- Feidhlimidh Geangcach mac Toirdhealbhaigh Óig Ó Conchobhair Donn, d. 1474 – last fully recognised King of Connacht.

- Tadhg mac Eoghain Ó Conchobhair Donn, d. 1476.

- Eoghan Caoch mac Feidhlimidh Gheangcaigh Ó Conchobhair Donn, d. 1485.

- Aodh Og mac Aodh Ó Conchobhair Donn

- Toirdhealbhach Óg mac Ruaidhri Ó Conchobhair Donn, d. 1503

- Conchobhar mac Eoghain Chaoich Ó Conchobhair Donn

- Cairbre mac Eoghain Chaoich Ó Conchobhair Donn, d. 1546

- Aodh mac Eoghain Chaoich Ó Conchobhair Donn, deposed 1550

- Diarmaid mac Cairbre Ó Conchobhair Donn, d. 1585

- Sir Hugh/Aedh Ó Conchobhair Donn, d. 1632

- An Calbhach mac Aedh Ó Conchobhair Donn, d. 1654 – popularly inaugurated king in 1643.

- Hugh Óg mac Aedh Ó Conchobhair Donn, d. 1662.

- Andrew O'Connor Don of Clonalis

- Dominick O'Connor Don of Clonalis, d. 1795

- Alexander O'Connor Don, d. 1820

- Owen O'Connor Don of Clonalis and Ballinagare, d.1831

- Denis O'Conor Don of Clonalis, 1794–1847

- Charles Owen O'Conor Don, 1838–1906

- Denis Charles O'Conor Don, 1869–1917

- Owen Phelim O'Conor Don, 1870–1943

- Fr. Charles O'Conor Don, 1906–1981

- Denis O'Conor Don, 1912 – 10 July 2000

- Desmond O'Conor Don (Former Chairman of the British-Chile Chamber of Commerce, former banker, resides in Sussex), b.1938

Other notable members of the family

- Hugo Oconór (Spanish Army Officer and Governor of Texas)

- Thomas O'Connor (Writer)

- Charles O'Conor (Irish American Lawyer and Politician)

- Nicholas Roderick O'Conor (British diplomat)

- Roderic O'Conor (Artist)

- Charles O'Conor (historian) (Historian)

- Charles O'Conor (priest) (Priest and historical author)

- Matthew O'Conor (Historian)

- Denis O'Conor (Politician)

- Charles Owen O'Conor (Politician)

- Denis Maurice O'Conor (Politician)

- Denis O'Conor Don (Prior Chief of the Name O'Conor, died 10 July 2000)

See also

- Ó Conchobhair Sligigh

- Clan Muircheartaigh Uí Conchobhair

- Gaelic nobility of Ireland

- Chief of the Name

- Irish nobility

- Irish royal families

- Chief Herald of Ireland

- O'Connor Sligo, a royal dynasty ruling the northern part of the Kingdom of Connacht

References

Footnotes

- O'Donovan, John (1891). The O'Conors of Connaught: An Historical Memoir. Dublin: Hodges, Figgis, and Co.

Bibliography

- Byrne, Vincent (2003). The Hidden Annals: A Thousand Years of the Kingdom of Connaught, 366-1385. Universal Publishers. ISBN 1581125682.

- O'Connor, Roderic, A Historical and Genealogical Memoir of the O'Connors, Kings of Connaught, and their Descendants. Dublin: McGlashan & Gill. 1861.

- O'Donovan, John and the Rt. Hon. Charles Owen O'Conor Don, The O'Conors of Connaught: An Historical Memoir. Dublin: Hodges, Figgis, and Co. 1891

External links

- O'Connor family pedigree at Library Ireland

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/O%27Conor#Don

Roderic O'Conor | |

|---|---|

Self portrait (c. 1903) | |

| Born | 17 October 1860 Castleplunket, County Roscommon, Ireland |

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roderic_O%27Conor

https://www.dib.ie/

Conchobar mac Taidg Mór (died 882) was a King of Connacht from the Uí Briúin branch of the Connachta. He was the grandson of Muirgius mac Tommaltaig (died 815), a previous king.[1] His father Tadg Mór (died 810) had been slain fighting in Muirgius' wars versus the minor tribes of Connacht.[2] He was of the Síl Muiredaig sept of the Uí Briúin. The Ó Conchobhair septs of Connacht are named for him.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conchobar_mac_Taidg_M%C3%B3r

| Book of Leinster | |

|---|---|

| Dublin, TCD, MS 1339 (olim MS H 2.18) | |

f. 53 | |

| Also known as | Lebor Laignech (Modern Irish Leabhar Laighneach); Lebor na Nuachongbála |

| Type | miscellany |

| Date | 12th century, second half |

| Place of origin | Terryglass (Co. Tipperary) and possibly Oughaval or Clonenagh (Co. Laois) |

| Scribe(s) | Áed Ua Crimthainn |

| Size | c. 13″ × 9″; 187 leaves |

| Condition | 45 leaves lost, according to manuscript note. |

| Previously kept | by the Ó Mhorda and Sir James Ware |

The Book of Leinster (Middle Irish: Lebor Laignech [ˈl͈ʲevər ˈlaɡʲnʲəx], LL) is a medieval Irish manuscript compiled c. 1160 and now kept in Trinity College Dublin, under the shelfmark MS H 2.18 (cat. 1339). It was formerly known as the Lebor na Nuachongbála "Book of Nuachongbáil", a monastic site known today as Oughaval.

Some fragments of the book, such as the Martyrology of Tallaght, are now in the collection of University College Dublin.[1]

Date and provenance

The manuscript is a composite work and more than one hand appears to have been responsible for its production. The principal compiler and scribe was probably Áed Ua Crimthainn,[2][3] who was abbot of the monastery of Tír-Dá-Glas on the Shannon, now Terryglass (County Tipperary), and the last abbot of that house for whom we have any record.[3] Internal evidence from the manuscript itself bears witness to Áed's involvement. His signature can be read on f. 32r (p. 313): Aed mac meic Crimthaind ro scrib in leborso 7 ra thinoil a llebraib imdaib ("Áed Húa Crimthaind wrote this book and collected it from many books"). In a letter copied by a later hand into a bottom margin (p. 288), the bishop of Kildare, Finn mac Gormáin (d. 1160), addresses him as a man of learning (fer léiginn) of the high-king of Leth Moga, the coarb (comarbu lit. 'successor') of Colum mac Crimthainn, and the chief scholar (prímsenchaid) of Leinster. An alternative theory was that by Eugene O'Curry, who suggested that Finn mac Gormáin transcribed or compiled the Book of Leinster for Áed.[3]

The manuscript was produced by Aéd and some of his pupils over a long period between 1151 and 1224.[3] From annals recorded in the manuscript we can say it was written between 1151 and 1201, with the bulk of the work probably complete in the 1160s. As Terryglass was burnt down in 1164, the manuscript must have been finalised in another scriptorium.[3] Suggested locations include Stradbally (Co. Loais) and Clonenagh (Co. Laois), the home of Uí Chrimthainn (see below).[3]

Eugene O'Curry suggested that the manuscript may have been commissioned by Diarmait Mac Murchada (d. 1171), king of Leinster, who had a stronghold (dún) in Dún Másc, near Oughaval (An Nuachongbáil). Dún Másc passed from Diarmait Mac Murchada to Strongbow, from Strongbow to his daughter Isabel, from Isabel to the Marshal Earls of Pembroke and from there, down several generations through their line. When Meiler fitz Henry established an Augustinian priory in Co. Laois, Oughaval was included in the lands granted to the priory.

History

Nothing certain is known of the manuscript's whereabouts in the next century or so after its completion, but in the 14th century, it came to light at Oughaval. It may have been kept in the vicarage in the intervening years.

The Book of Leinster owes its present name to John O'Donovan (d. 1861), who coined it on account of the strong associations of its textual contents with the province of Leinster, and to Robert Atkinson, who adopted it when he published the lithographic facsimile edition.[3]

However, it is now commonly accepted that the manuscript was originally known as the Lebor na Nuachongbála, that is the "Book of Noghoval", now Oughaval (Co. Laois), near Stradbally. This was established by R.I. Best, who observed that several short passages from the Book of Leinster are cited in an early 17th-century manuscript written by Sir James Ware (d. 1666), found today under the shelfmark London, British Library, Add. MS 4821. These extracts are attributed to the "Book of Noghoval" and were written at a time when Ware stayed at Ballina (Ballyna, Co. Kildare), enjoying the hospitality of Rory O'Moore. His family, the O'Moores (Ó Mhorda), had been lords of Noghoval since the early 15th century if not earlier, and it was probably with their help that he obtained access to the manuscript. The case for identification with the manuscript now known as the Book of Leinster is suggested by the connection of Rory's family to the Uí Chrimthainn, coarbs of Terryglass: his grandfather had a mortgage on Clonenagh, the home of Uí Chrimthainn.[4]

Best's suggestion is corroborated by evidence from Dublin, Royal Irish Academy MS B. iv. 2, also of the early 17th century. As Rudolf Thurneysen noted, the scribe copied several texts from the Book of Leinster, identifying his source as the "Leabhar na h-Uachongbála", presumably for Leabhar na Nuachongbála ("Book of Noughaval").[5] Third, in the 14th century, the Book of Leinster was located at Stradbally (Co. Laois), the place of a monastery known originally as Nuachongbáil "of the new settlement" (Noughaval) and later as Oughaval.[6]

Contents

The manuscript has 187 leaves, each approximately 13" by 9" (33 cm by 23 cm). A note in the manuscript suggests as many as 45 leaves have been lost. The book, a wide-ranging compilation, is one of the most important sources of medieval Irish literature, genealogy and mythology, containing, among many others, texts such as Lebor Gabála Érenn (the Book of Invasions), the most complete version of Táin Bó Cuailnge (the Cattle Raid of Cooley), the Metrical Dindshenchas and an Irish translation/adaptation of the De excidio Troiae Historia, and before its separation from the main volume, the Martyrology of Tallaght.

A diplomatic edition was published by the Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies in six volumes over a period of 29 years.

Notes

- Best, Book of Leinster, vol. 1, p. xi-xv

References

Editions

- Atkinson, Robert. The Book of Leinster, sometimes called the Book of Glendalough. Dublin, 1880. 1–374. Facsimile edition.

- Book of Leinster, ed. R.I. Best; Osborn Bergin; M.A. O'Brien; Anne O'Sullivan (1954–83). The Book of Leinster, formerly Lebar na Núachongbála. 6 vols. Dublin: DIAS. Available from CELT: vols. 1 (pp. 1–260), 2 (pp. 400–70), 3 (pp. 471–638, 663), 4 (pp. 761–81 and 785–841), 5 (pp. 1119–92 and 1202–1325) . Diplomatic edition.

Secondary sources

- Hellmuth, Petra S. (2006). "Lebor Laignech". In Koch, John T. (ed.). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, Denver, and Oxford: ABC-CLIO. pp. 1125–6.

- Ní Bhrolcháin, Muireann (2005). "Leinster, Book of". In Seán Duffy (ed.). Medieval Ireland. An Encyclopedia. New York and Abingdon: Routledge. pp. 272–4.

- Ó Concheanainn, Tomás (1984). "LL and the Date of the Reviser of LU". Éigse. 20: 212–25.

- O'Sullivan, William (1966). "Notes on the Scripts and Make-Up of the Book of Leinster". Celtica. 7: 1–31.

External links

- Contents of the Book of Leinster

- Translations into English for much of the Book of Leinster

- Irish text: volumes 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 & 6 at CELT

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Book_of_Leinster

| Kings of Connacht | |

|---|---|

| Rí Chonnacht | |

Map of Connacht, c. 10th century. | |

| Details | |

| Style | Rí Chonnacht |

| First monarch | Genann |

| Last monarch | Feidhlimidh Geangcach Ó Conchobair |

| Formation | Ancient |

| Abolition | 1474 |

| Residence | Rathcroghan Carnfree |

| Appointer | Tanistry |

| Pretender(s) | Desmond O'Conor Don (Ó Conchubhair Donn) |

The Kings of Connacht were rulers of the cóiced (variously translated as portion, fifth, province) of Connacht, which lies west of the River Shannon, Ireland. However, the name only became applied to it in the early medieval era, being named after the Connachta.

The old name for the province was Cóiced Ol nEchmacht (the fifth of the Ol nEchmacht). Ptolemy's map of c. 150 AD does in fact list a people called the Nagnatae as living in the west of Ireland. Some are of the opinion that Ptolemy's Map of Ireland may be based on cartography carried out as much as five hundred years before his time.

The Connachta were a group of dynasties who claimed descent from the three eldest sons of Eochaid Mugmedon: Brion, Ailill and Fiachrae. They took their collective name from their alleged descent from Conn Cétchathach. Their younger brother, Niall Noigiallach was ancestor to the Uí Néill.

The following is a list of kings of Connacht from the fifth to fifteenth centuries.

Prehistoric kings of Ol nEchmacht

- Genann

- Conrac Cas

- Eochaid Feidlech

- Eochaidh Allat

- Tinni mac Conri

- Medb, Queen of Connacht

- Medb and Ailill mac Máta

- Maine Aithreamhail mac Ailill Máta

- Sanbh Sithcheann mac Ceat mac Magha

- Cairbre mac Maine Aithreamhail

- Eochaidh Fionn

- Aodh mac Cu Odhar

- Eochaidh mac Cairbre

- Aonghus Fionn mac Domhnall

- Cormac Ulfhada

- Aonghus Feirt mac Aonghus Fionn

- Connall Cruchain mac Aonghus Feirt

- Fearadach mac Connal Cruchain

- Forghus Fiansa

- Forghus Fiansa and Art mac Conn

- Ceidghin Cruchain mac Connall Cruchain

- Aodh mac Eochaidh

- Aodh Alainn mac Eochaidh Baicidh

- Nia Mór mac Lughna

- Lughaidh mac Lughna Fear Tri

- Aodh Caomh mac Garadh Glundubh

- Coinne mac Fear Tri

- Muireadh Tireach mac Fiachra Sraibrintne

- Eochaid Mugmedon

- Niall Noigiallach/Niall of the Nine Hostages, died c. 450/455

List of historical kings

Uí Fiachrach, 406–482

| Name | Reign | Clan Arms | Parentage | Death |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amalgaid mac Fiachrae | 406–440 | Son of Fiachrae | 440 | |

| Nath Í mac Fiachrach | 440–445 | Son of Fiachrae | 445 | |

| Ailill Molt | 445–482 | Son of Nath Í mac Fiachrach | 482 |

Uí Briúin, 482–500

| Name | Reign | Clan Arms | Parentage | Death |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dauí Tenga Uma | 482–500 | Son of Brión mac Echach Muigmedóin | 500 |

Uí Fiachrach, 500–549

| Name | Reign | Clan Arms | Parentage | Death |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eógan Bél | 500–542 | Son of Cellaig, the son of Ailill Molt | 542 | |

| Ailill Inbanda | 542–549 | Son of Eógan Bél | 549 |

Uí Briúin, 549–600

| Name | Reign | Clan Arms | Parentage | Death |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Echu Tirmcharna | 549–556 | Son of Fergus mac Muireadach | 556 | |

| Áed mac Echach | 556–575 | Son of Echu Tirmcharna | 575 | |

| Uatu mac Áedo | 575–600 | Son of Áed mac Echach | 600 |

Uí Fiachrach Aidhne, 600–622

| Name | Reign | Clan Arms | Parentage | Death |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colmán mac Cobthaig | 600–622 | Son of Cobthach mac Gabran | 622 |

Uí Briúin, 622–649

| Name | Reign | Clan Arms | Parentage | Death |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rogallach mac Uatach | 622–649 | Son of Uatu mac Áedo | 649 |

Uí Fiachrach Aidhne, 649–663

| Name | Reign | Clan Arms | Parentage | Death |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loingsech mac Colmáin | 649–655 | Son of Colmán mac Cobthaig | 655 | |

| Guaire Aidne mac Colmáin | 655–663 | Son of Colmán mac Cobthaig | 663 |

Uí Briúin Seóla, 663–682

| Name | Reign | Clan Arms | Parentage | Death |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cenn Fáelad mac Colgan | 663–682 | Son of Colga mac Aodha | 682 |

Uí Fiachrach Muaidhe, 682–683

| Name | Reign | Clan Arms | Parentage | Death |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dúnchad Muirisci | 682–683 | Son of Tipraite mac Máel Dubh | 683 |

Uí Fiachrach Aidhne, 683–696

| Name | Reign | Clan Arms | Parentage | Death |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fergal Aidne mac Artgaile | 683–696 | Son of Artgal mac Guaire | 696 |

Uí Briúin Síl Muiredaig, 696–702

| Name | Reign | Clan Arms | Parentage | Death |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Muiredach Muillethan | 696–702 | Son of Fergus mac Rogallaig | 702 |

Uí Briúin Síl Cellaig, 702–705

| King | Clan sept | Reign |

|---|---|---|

| Cellach mac Rogallach mac Uatach | Uí Briúin | 702–705 |

Uí Fiachrach Muaidhe, 705–707

| Name | Reign | Clan Arms | Parentage | Death |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indrechtach mac Dúnchado | 705–707 | Son of Dúnchad Muirisci | 707 |

Uí Briúin Síl Muiredaig, 707–723

| Name | Reign | Clan Arms | Parentage | Death |