Hyperkeratosis is thickening of the stratum corneum (the outermost layer of the epidermis, or skin), often associated with the presence of an abnormal quantity of keratin,[1] and also usually accompanied by an increase in the granular layer. As the corneum layer normally varies greatly in thickness in different sites, some experience is needed to assess minor degrees of hyperkeratosis.

It can be caused by vitamin A deficiency or chronic exposure to arsenic.

Hyperkeratosis can also be caused by B-Raf inhibitor drugs such as Vemurafenib and Dabrafenib.[2]

It can be treated with urea-containing creams, which dissolve the intercellular matrix of the cells of the stratum corneum, promoting desquamation of scaly skin, eventually resulting in softening of hyperkeratotic areas.[3]

| Hyperkeratosis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Micrograph showing prominent hyperkeratosis in skin without atypia. H&E stain. | |

| Pronunciation | |

| Specialty | Dermatology |

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hyperkeratosis

Mucus (/ˈmjuːkəs/ MEW-kəs) is a slippery aqueous secretion produced by, and covering, mucous membranes. It is typically produced from cells found in mucous glands, although it may also originate from mixed glands, which contain both serous and mucous cells. It is a viscous colloid containing inorganic salts, antimicrobialenzymes (such as lysozymes), immunoglobulins (especially IgA), and glycoproteins such as lactoferrin[1] and mucins, which are produced by goblet cells in the mucous membranes and submucosal glands. Mucus serves to protect epithelial cells in the linings of the respiratory, digestive, and urogenital systems, and structures in the visual and auditory systems from pathogenic fungi, bacteria[2] and viruses. Most of the mucus in the body is produced in the gastrointestinal tract.

Amphibians, fish, hagfish, snails, slugs, and some other invertebrates also produce external mucus from their epidermis as protection against pathogens, and to help in movement and is also produced in fish to line their gills. Plants produce a similar substance called mucilage that is also produced by some microorganisms.[3]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mucus

Above. Growth culture.

Mucociliary clearance (MCC), mucociliary transport, or the mucociliary escalator, describes the self-clearing mechanism of the airways in the respiratory system.[1] It is one of the two protective processes for the lungs in removing inhaled particles including pathogens before they can reach the delicate tissue of the lungs. The other clearance mechanism is provided by the cough reflex.[2]Mucociliary clearance has a major role in pulmonary hygiene.

MCC effectiveness relies on the correct properties of the airway surface liquid produced, both of the periciliary sol layer and the overlying mucus gel layer, and of the number and quality of the cilia present in the lining of the airways.[3] An important factor is the rate of mucin secretion. The ion channels CFTRand ENaC work together to maintain the necessary hydration of the airway surface liquid.[4]

Any disturbance in the closely regulated functioning of the cilia can cause a disease. Disturbances in the structural formation of the cilia can cause a number of ciliopathies, notably primary ciliary dyskinesia.[5]Cigarette smoke exposure can cause shortening of the cilia.[6]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mucociliary_clearance

Cirrhosis, also known as liver cirrhosis or hepatic cirrhosis, and end-stage liver disease, is the impaired liver function caused by the formation of scar tissue known as fibrosis, due to damage caused by liver disease.[9] Damage causes tissue repair and subsequent formation of scar tissue, which over time can replace normal functioning tissue leading to the impaired liver function of cirrhosis.[9][10] The disease typically develops slowly over months or years.[1] Early symptoms may include tiredness, weakness, loss of appetite, unexplained weight loss, nausea and vomiting, and discomfort in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen.[2] As the disease worsens, symptoms may include itchiness, swelling in the lower legs, fluid build-up in the abdomen, jaundice, bruising easily, and the development of spider-like blood vessels in the skin.[2] The fluid build-up in the abdomen may become spontaneously infected.[1] More serious complications include hepatic encephalopathy, bleeding from dilated veins in the esophagus, stomach, or intestines, and liver cancer.[11]

Cirrhosis is most commonly caused by alcoholic liver disease, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis(NASH) – (the progressive form of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease),[12] chronic hepatitis B, and chronic hepatitis C.[2][4] Heavy drinking over a number of years can cause alcoholic liver disease.[13] NASH has a number of causes, including obesity, high blood pressure, abnormal levels of cholesterol, type 2 diabetes, and metabolic syndrome.[3] Less common causes of cirrhosis include autoimmune hepatitis, primary biliary cholangitis, and primary sclerosing cholangitis that disrupts bile duct function, genetic disorders such as Wilson's disease and hereditary hemochromatosis, and chronic heart failure with liver congestion.[2]

Diagnosis is based on blood tests, medical imaging, and liver biopsy.[5][1]

Hepatitis B vaccine can prevent hepatitis B and the development of cirrhosis, but no vaccinationagainst hepatitis C is available.[1] No specific treatment for cirrhosis is known, but many of the underlying causes may be treated by a number of medications that may slow or prevent worsening of the condition.[6] Avoiding alcohol is recommended in all cases.[1] Hepatitis B and C may be treatable with antiviral medications.[1] Autoimmune hepatitis may be treated with steroid medications.[1] Ursodiol may be useful if the disease is due to blockage of the bile duct.[1] Other medications may be useful for complications such as abdominal or leg swelling, hepatic encephalopathy, and dilated esophageal veins.[1] If cirrhosis leads to liver failure a liver transplantmay be an option.[3]

Cirrhosis affected about 2.8 million people and resulted in 1.3 million deaths in 2015.[7][8] Of these deaths, alcohol caused 348,000, hepatitis C caused 326,000, and hepatitis B caused 371,000.[8]In the United States, more men die of cirrhosis than women.[1] The first known description of the condition is by Hippocrates in the fifth century BCE.[14] The term "cirrhosis" was invented in 1819, from a Greek word for the yellowish color of a diseased liver.[15]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cirrhosis

Primary biliary cholangitis (PBC), previously known as primary biliary cirrhosis, is an autoimmune disease of the liver.[1][2][3] It results from a slow, progressive destruction of the small bile ducts of the liver, causing bile and other toxins to build up in the liver, a condition called cholestasis. Further slow damage to the liver tissue can lead to scarring, fibrosis, and eventually cirrhosis.

Common symptoms are tiredness, itching, and in more advanced cases, jaundice. In early cases, the only changes may be in blood tests.[4]

PBC is a relatively rare disease, affecting up to one in 3,000–4,000 people.[5][6] It is much more common in women, with a sex ratio of at least 9:1 female to male.[1]

The condition has been recognised since at least 1851, and was named "primary biliary cirrhosis" in 1949.[7] Because cirrhosis is a feature only of advanced disease, a change of its name to "primary biliary cholangitis" was proposed by patient advocacy groups in 2014.[8][9]

| Primary biliary cholangitis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Primary biliary cirrhosis |

| |

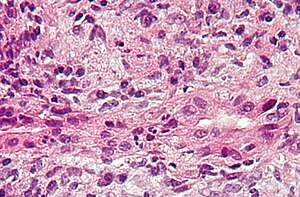

| Micrograph of PBC showing bile duct inflammation and injury, H&E stain | |

| Specialty | Gastroenterology, Hepatology |

| Symptoms | Cholestasis, pruritus, fatigue |

| Complications | Cirrhosis, hepatic failure, portal hypertension |

| Usual onset | Usually middle-aged women |

| Causes | Autoimmune |

| Risk factors | Female gender |

| Diagnostic method | Anti-mitochondrial antibodies, Liver biopsy |

| Differential diagnosis | Autoimmune hepatitis |

| Treatment | Ursodeoxycholic acid, obeticholic acid, cholestyramine |

| Frequency | 1 in 3,000–4,000 people |

PBC can eventually progress to cirrhosis of the liver. This, in turn, may lead to a number of symptoms or complications:

- Fluid retention in the abdomen (ascites) in more advanced disease

- Enlarged spleen in more advanced disease

- Oesophageal varices in more advanced disease

- Hepatic encephalopathy, including coma in extreme cases in more advanced disease.

People with PBC may also sometimes have the findings of an associated extrahepatic autoimmune disorder such as thyroid disease or rheumatoid arthritis or Sjögren's syndrome (in up to 80% of cases).[10][11]

PBC has an immunological basis, and is classified as an autoimmune disorder. It results from a slow, progressive destruction of the small bile ducts of the liver, with the intralobular ducts and the canals of Hering (intrahepatic ductules) being affected early in the disease.

Most people with PBC (more than 90%) have antimitochondrial antibodies (AMAS) against pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDC-E2), an enzyme complex found in the mitochondria. People who are negative for AMAs are usually found to be positive when more sensitive methods of detection are used.[12]

People with PBC may also have been diagnosed with another autoimmune disease, such as a rheumatological, endocrinological, gastrointestinal, pulmonary, or dermatological condition, suggesting shared genetic and immune abnormalities.[11] Common associations include Sjögren's syndrome, systemic sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, hypothyroidism, and coeliac disease.[13][14]

A genetic predisposition to disease has been thought to be important for some time. Evidence for this includes cases of PBC in family members, identical twins both having the condition (concordance), and clustering of PBC with other autoimmune diseases. In 2009, a Canadian-led group of investigators reported in the New England Journal of Medicine results from the first PBC genome-wide association study.[15][16] This research revealed parts of the IL12 signaling cascade, particularly IL12A and IL12RB2 polymorphisms, to be important in the aetiology of the disease in addition to the HLA region. In 2012, two independent PBC association studies increased the total number of genomic regions associated to 26, implicating many genes involved in cytokine regulation such as TYK2, SH2B3 and TNFSF11.[17][18]

A study of over 2000 patients identified a gene, POGLUT1, that appeared to be associated with this condition.[19] Earlier studies have also suggested that this gene may be involved. The implicated protein is an endoplasmic reticulum O-glucosyltransferase.

An environmental Gram-negative Alphaproteobacterium — Novosphingobium aromaticivorans[20] has been associated with this disease, with several reports suggesting an aetiological role for this organism.[21][22][23] The mechanism appears to be a cross-reaction between the proteins of the bacterium and the mitochondrial proteins of the liver cells. The gene encoding CD101 may also play a role in host susceptibility to this disease.[24]

A failure of immune tolerance against the mitochondrial pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDC-E2) is a primary cause, with shedding of the antigen into apoptotic bodies or "apotopes" leading to the anatomic localization.[25] Such autoreactivity may also be the case with other proteins, including the gp210 and p62 nuclear pore proteins. Gp210 has increased expression in the bile duct of anti-gp210 positive patients, and these proteins may be associated with prognosis.[26]

Most patients are currently diagnosed when asymptomatic, having been referred to the hepatologist for abnormal liver function tests (mostly raised GGT or alkaline phosphatase) performed for annual screening blood tests. Other frequent scenarios include screening of patients with nonliver autoimmune diseases, e.g. rheumatoid arthritis, or investigation of elevated cholesterol, evaluation of itch or unresolved cholestasis post partum. Diagnosing PBC is generally straightforward. The basis for a definite diagnosis are:

- Abnormalities in liver enzyme tests are usually present and elevated gamma-glutamyl transferase and alkaline phosphatase are found in early disease.[10] Elevations in bilirubin occur in advanced disease.

- Antimitochondrial antibodies are the characteristic serological marker for PBC, being found in 90-95% of patients and only 1% of controls. PBC patients have AMA against pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDC-E2), an enzyme complex that is found in the mitochondria.[10] Those people who are AMA negative but with disease similar to PBC have been found to have AMAs when more sensitive detection methods are employed.[12]

- Other auto-antibodies may be present:

- Antinuclear antibody measurements are not diagnostic for PBC because they are not specific, but may have a role in prognosis.

- Anti-glycoprotein-210 antibodies, and to a lesser degree anti-p62 antibodies, correlate with the disease's progression toward end-stage liver failure. Anti-gp210 antibodies are found in 47% of PBC patients.[27][28]

- Anti-centromere antibodies often correlate with developing portal hypertension.[29]

- Anti-np62[30] and anti-sp100 are also found in association with PBC.

- Abdominal ultrasound, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography or a CT scan is usually performed to rule out blockage to the bile ducts. This may be needed if a condition causing secondary biliary cirrhosis, such as other biliary duct disease or gallstones, needs to be excluded. A liver biopsy may help, and if uncertainty remains as in some patients, an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, an endoscopicinvestigation of the bile duct, may be performed.

Given the high specificity of serological markers, liver biopsy is not necessary for the diagnosis of PBC; however, it is still necessary when PBC-specific antibodies are absent, or when co-existent autoimmune hepatitis or nonalcoholic steatohepatitis is suspected. Liver biopsy can be useful to stage the disease for fibrosis and ductopenia. Finally, it may also be appropriate in the presence of other extrahepatic comorbidities.

On microscopic examination of liver biopsy specimens, PBC is characterized by chronic, nonsuppurative inflammation, which surrounds and destroys interlobular and septal bile ducts. These histopathologic findings in primary biliary cholangitis include:[31]

- Inflammation of the bile ducts, characterized by intraepithelial lymphocytes

- Periductal epithelioid granulomas.

- Proliferation of bile ductules

- Fibrosis (scarring)

The Ludwig and Scheuer scoring systems have historically been used to stratify four stages of PBC, with stage 4 indicating the presence of cirrhosis. In the new system of Nakanuma, the stage of disease is based on fibrosis, bile duct loss, and features of cholestasis, i.e. deposition of orcein-positive granules, whereas the grade of necroinflammatory activity is based on cholangitis and interface hepatitis. The accumulation of orcein-positive granules occurs evenly across the PBC liver, which means that staging using the Nakanuma system is more reliable regarding sampling variability.

Liver biopsy for the diagnosis and staging of PBC lost favour after the evidence of a patchy distribution of the duct lesions and fibrosis across the organ. The widespread availability of noninvasive measures of fibrosis means that liver biopsy for staging of PBC is somewhat obsolete. Liver biopsy does, however, remain useful in certain settings. The main indications are to confirm the diagnosis of PBC when PBC-specific antibodies are absent and confirm a diagnosis of PBC with AIH features (i.e. overlap PBC-AIH). Liver biopsy is also useful to assess the relative contribution of each liver injury when a comorbid liver disease is present, such as non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. In patients with inadequate response to UDCA, liver biopsy may provide the explanation and could undoubtedly inform risk stratification. For example, it may identify a previously unsuspected variant syndrome, steatohepatitis, or interface hepatitis of moderate or greater severity. It is also useful in AMA and ANA-specific antibody negative cholestatic patients to indicate an alternative process, e.g. sarcoidosis, small duct PSC, adult idiopathic ductopenia.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Primary_biliary_cholangitis

No comments:

Post a Comment