Above. lil deucedeuce witch encounter remix

Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) is the ninth known human herpesvirus; its formal name according to the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) is Human gammaherpesvirus 8, or HHV-8 in short.[1] Like other herpesviruses, its informal names are used interchangeably with its formal ICTV name. This virus causes Kaposi's sarcoma, a cancer commonly occurring in AIDS patients,[2] as well as primary effusion lymphoma,[3] HHV-8-associated multicentric Castleman's disease and KSHV inflammatory cytokine syndrome.[4] It is one of seven currently known human cancer viruses, or oncoviruses.[2] Even after so many years of discovery of KSHV/HHV8, there is no known cure for KSHV associated tumorigenesis.

Virus classificatio

(unranked):VirusRealm:DuplodnaviriaKingdom:HeunggongviraePhylum:PeploviricotaClass:HerviviricetesOrder:HerpesviralesFamily:HerpesviridaeGenus:RhadinovirusSpecies:

In 1872, Moritz Kaposi described a blood vessel tumor[5] (originally called "idiopathic multiple pigmented sarcoma of the skin") that has since been eponymously named Kaposi's sarcoma (KS). KS was at first thought to be an uncommon tumor of Jewish and Mediterranean populations until it was later determined to be extremely common throughout sub-Saharan African populations. This led to the first suggestions in the 1950s that this tumor might be caused by a virus. With the onset of the AIDS epidemic in the early 1980s, there was a sudden resurgence of KS affecting primarily gay and bisexual AIDS patients, with up to 50% of reported AIDS patients having this tumor—an extraordinary rate of cancer predisposition.[citation needed]

The pathogen was ultimately identified in 1994 by Yuan Chang and Patrick S. Moore, a wife and husband team at Columbia University, through the isolation of DNA fragments from a herpesvirus found in a KS tumor in an AIDS patient.[7][8][9] Chang and Moore used representational difference analysis, or RDA, to find KSHV by comparing KS tumor tissue from an AIDS patient to his own unaffected tissue. The idea behind this experiment was that if a virus causes KS, the genomic DNA in the two samples should be precisely identical except for DNA belonging to the virus. In their initial RDA experiment, they isolated two small DNA fragments that represented less than 1% of the actual viral genome. These fragments were similar (but still distinct from) the known herpevirus sequences, indicating the presence of a new virus. Starting from these fragments, this research team was then able to sequence the entire genome of the virus less than two years later.[citation needed]

The discovery of this herpesvirus sparked considerable controversy and scientific in-fighting until sufficient data had been collected to show that indeed KSHV was the causative agent of Kaposi's sarcoma.[10] The virus is now known to be a widespread infection of people living in sub-Saharan Africa; intermediate levels of infection occur in Mediterranean populations (including Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, Italy, and Greece) and low levels of infection occur in most Northern European and North American populations. Gay and bisexual men are more susceptible to infection (through still unknown routes of sexual transmission) whereas the virus is transmitted through non-sexual routes in developing countries.[citation needed]

After infection, the virus enters into lymphocytes via macropinosomes where it remains in a latent ("quiet") state. Only a subset of genes that are encoded in KSHV latency associated region (KLAR) are expressed during latency including latency-associated nuclear antigen (LANA), vFLIP, vCyclin and 12 microRNA.

LANA tethers the viral DNA to cellular chromosomes, inhibits p53 and retinoblastoma protein and suppresses viral genes needed for full virus production and assembly ("lytic replication")....

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kaposi%27s_sarcoma-associated_herpesvirus

Human herpesvirus 8 associated multicentric Castleman disease (HHV-8-associated MCD) is a subtype of Castleman disease (also known as giant lymph node hyperplasia, lymphoid hamartoma, or angiofollicular lymph node hyperplasia), a group of rare lymphoproliferative disorders characterized by lymph node enlargement, characteristic features on microscopic analysis of enlarged lymph node tissue, and a range of symptoms and clinical findings.

People with human herpesvirus 8 associated multicentric Castelman disease (HHV-8-associated MCD) have enlarged lymph nodes in multiple regions and often have flu-like symptoms, abnormal findings on blood tests, and dysfunction of vital organs, such as the liver, kidneys, and bone marrow.

HHV-8-associated MCD is known to be caused by uncontrolled infection with the human herpesvirus 8 virus (HHV-8) and is most frequently diagnosed in patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). HHV-8-associated MCD is treated with a variety of medications, including immunosuppressants, chemotherapy, and antivirals.

Castleman disease is named after Dr. Benjamin Castleman, who first described the disease in 1956. The Castleman Disease Collaborative Network is the largest organization focused on the disease and is involved in research, awareness, and patient support.

rashes such as cherry hemangiomas or Kaposi sarcoma; enlargement of the liver and/or spleen; and extravascular fluid accumulation in the extremities (edema), abdomen (ascites), or lining of the lungs (pleural effusion).[1]

In HHV-8-associated MCD the HHV-8 virus infects B cells and plasmablasts in lymph nodes and causes infected cells to release proinflammatory cytokines, signaling molecules that increase the activity of immune cells. In particular, HHV-8 infection of immune cells leads to increased levels of Interleukin-6 (IL-6), a cytokine known to play a role in other forms of Castleman disease.[citation needed]

The HHV-8 virus contains a gene coding for a viral variant of the IL-6 molecule. Cells infected by HHV-8 produce the viral variant of IL-6 and normal human IL-6, both of which contribute to the increased B cell proliferation and clinical findings seen in HHV-8-associated MCD.[4]

| HHV-8-associated MCD | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Giant lymph node hyperplasia, lymphoid hamartoma, angiofollicular lymph node hyperplasia |

| |

| Micrograph of HHV8-associated Castleman's Disease showing LANA-1 positive lymphoblasts in a regressed germinal center and mantle zone. LANA-1 stain. | |

Idiopathic multicentric Castleman disease (iMCD) is a subtype of Castleman disease (also known as giant lymph node hyperplasia, lymphoid hamartoma, or angiofollicular lymph node hyperplasia), a group of lymphoproliferative disorders characterized by lymph node enlargement, characteristic features on microscopic analysis of enlarged lymph node tissue, and a range of symptoms and clinical findings.

People with iMCD have enlarged lymph nodes in multiple regions and often have flu-like symptoms, abnormal findings on blood tests, and dysfunction of vital organs, such as the liver, kidneys, and bone marrow.

iMCD has features often found in autoimmune diseases and cancers, but the underlying disease mechanism is unknown. Treatment for iMCD may involve the use of a variety of medications, including immunosuppressants and chemotherapy.

Castleman disease was named after Dr. Benjamin Castleman, who first described the disease in 1956. The Castleman Disease Collaborative Network is the largest organization focused on the disease and is involved in research, awareness, and patient support.

| Idiopathic multicentric Castleman disease | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Giant lymph node hyperplasia, lymphoid hamartoma, angiofollicular lymph node hyperplasia |

| |

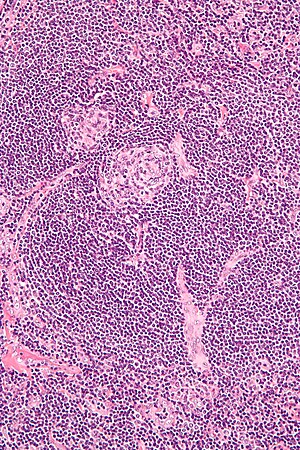

| Micrograph of lymph node biopsy demonstrating hyaline vascular features consistent with Castleman disease | |

| Specialty | Hematology, immunology, rheumatology, pathology |

| Diagnostic method | Based on patient history, physical exam, laboratory testing, medical imaging, histopathology |

| Frequency | approximately 1500-1800 new cases per year in the United States |

Several theoretical mechanisms for iMCD have been proposed based on existing research and observed similarities between iMCD and other diseases that present with similar clinical findings and lymph node histology:[2]

- Autoimmune – The immune system may produce antibodies that target healthy cells in the body instead of bacteria and viruses. Self-directed antibodies are commonly seen in autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematous and rheumatoid arthritis.

- Autoinflammatory – A mutation in a gene controlling inflammatory systems may contribute to harmful activation of inflammatory pathways in patients with iMCD.

- Neoplastic – Genetic mutations that develop in mature cells (somatic mutations) may cause an overgrowth of abnormal cells as in cancers such as lymphoma.

- Pathogen – Human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) is the known causative agent in HHV-8-associated MCD, which has very similar symptoms and findings to iMCD. While iMCD by definition is not caused by HHV-8, an unknown virus may cause the disease.

There have been no reported cases of UCD transforming into iMCD.[citation needed]

Idiopathic multicentric Castleman disease[edit]

iMCD may be further differentiated by the presence of associated diseases, such as polyneuropathy, organomegaly, endocrinopathy, monoclonal protein, skin changes syndrome (POEMS syndrome), or by distinct clinical features, such as thrombocytopenia, anasarca, myelofibrosis, renal dysfunction, and organomegaly syndrome (TAFRO syndrome).[5]

Diagnostic criteria[edit]

Diagnosis of iMCD requires: the presence of both major criteria, multiple regions of enlarged lymph nodes as demonstrated by medical imaging; the presence of at least two minor criteria, at least one of which must be an abnormal laboratory test; and exclusion of diseases that can mimic iMCD.[citation needed]

Major criteria 1: multiple regions of enlarged lymph nodes[edit]

Radiologic imaging must demonstrate enlarged lymph nodes in multiple regions.[5]

Major criteria 2: microscopic analysis of lymph node biopsy consistent with iMCD[edit]

The microscopic appearance (histology) of biopsied tissue from an enlarged lymph node must demonstrate a constellation of features consistent with Castleman disease. There are three patterns of characteristic histologic features associated with iMCD:[5]

- Hypervascular - regressed germinal centers, follicular dendritic cell prominence, hypervascularity in interfollicular regions, and prominent mantle zoneswith an “onion-skin” appearance.

- Plasmacytic – increased number of follicles with large hyperplastic germinal centers and sheet-like plasmacytosis (increased number of plasma cells).

- Mixed – features of both hypervascular and plasmacytic.

iMCD most commonly demonstrates plasmacytic features; however, hypervascular features or a mixture of both hypervascular and plasmacytic features may also be seen in iMCD lymph nodes. The clinical utility of subtyping iMCD by histologic features is uncertain, as histologic subtypes do not consistently predict disease severity or treatment response.[citation needed]

Staining with latency-associated nuclear antigen (LANA-1), a marker of HHV-8 infection, must be negative to diagnose iMCD.[5]

Minor criteria

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Idiopathic_multicentric_Castleman_disease

Cytokines are a broad and loose category of small proteins (~5–20 kDa) important in cell signaling. Cytokines are peptides and cannot cross the lipid bilayer of cells to enter the cytoplasm. Cytokines have been shown to be involved in autocrine, paracrine and endocrine signaling as immunomodulating agents. Their definite distinction from hormones is still part of ongoing research.

Cytokines include chemokines, interferons, interleukins, lymphokines, and tumour necrosis factors, but generally not hormones or growth factors (despite some overlap in the terminology). Cytokines are produced by a broad range of cells, including immune cells like macrophages, B lymphocytes, T lymphocytes and mast cells, as well as endothelial cells, fibroblasts, and various stromal cells; a given cytokine may be produced by more than one type of cell.[1][2] They act through cell surface receptors and are especially important in the immune system; cytokines modulate the balance between humoral and cell-based immune responses, and they regulate the maturation, growth, and responsiveness of particular cell populations. Some cytokines enhance or inhibit the action of other cytokines in complex ways. They are different from hormones, which are also important cell signaling molecules. Hormones circulate in higher concentrations, and tend to be made by specific kinds of cells. Cytokines are important in health and disease, specifically in host immune responsesto infection, inflammation, trauma, sepsis, cancer, and reproduction.

The word comes from the ancient Greek language: cyto, from Greek κύτος, kytos, 'cavity, cell' + kines, from Greek κίνησις, kinēsis, 'movement'.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cytokine

No comments:

Post a Comment