Metallurgy is a domain of materials science and engineering that studies the physical and chemical behavior of metallic elements, their inter-metallic compounds, and their mixtures, which are called alloys. Metallurgy encompasses both the science and the technology of metals; that is, the way in which science is applied to the production of metals, and the engineering of metal components used in products for both consumers and manufacturers. Metallurgy is distinct from the craft of metalworking. Metalworking relies on metallurgy in a similar manner to how medicine relies on medical science for technical advancement. A specialist practitioner of metallurgy is known as a metallurgist.

The science of metallurgy is subdivided into two broad categories: chemical metallurgy and physical metallurgy. Chemical metallurgy is chiefly concerned with the reduction and oxidation of metals, and the chemical performance of metals. Subjects of study in chemical metallurgy include mineral processing, the extraction of metals, thermodynamics, electrochemistry, and chemical degradation (corrosion).[1] In contrast, physical metallurgy focuses on the mechanical properties of metals, the physical properties of metals, and the physical performance of metals. Topics studied in physical metallurgy include crystallography, material characterization, mechanical metallurgy, phase transformations, and failure mechanisms.[2]

Historically, metallurgy has predominately focused on the production of metals. Metal production begins with the processing of ores to extract the metal, and includes the mixture of metals to make alloys. Metal alloys are often a blend of at least two different metallic elements. However, non-metallic elements are often added to alloys in order to achieve properties suitable for an application. The study of metal production is subdivided into ferrous metallurgy (also known as black metallurgy) and non-ferrous metallurgy (also known as colored metallurgy). Ferrous metallurgy involves processes and alloys based on iron, while non-ferrous metallurgy involves processes and alloys based on other metals. The production of ferrous metals accounts for 95% of world metal production.[3]

Modern metallurgists work in both emerging and traditional areas as part of an interdisciplinary team alongside material scientists, and other engineers. Some traditional areas include mineral processing, metal production, heat treatment, failure analysis, and the joining of metals (including welding, brazing, and soldering). Emerging areas for metallurgists include nanotechnology, superconductors, composites, biomedical materials, electronic materials (semiconductors) and surface engineering.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Metallurgy

Alchemy (from Arabic: al-kīmiyā; from Ancient Greek: khumeía)[1] is an ancient branch of natural philosophy, a philosophical and protoscientific tradition that was historically practiced in China, India, the Muslim world, and Europe.[2]In its Western form, alchemy is first attested in a number of pseudepigraphical texts written in Greco-Roman Egyptduring the first few centuries CE.[3]

Alchemists attempted to purify, mature, and perfect certain materials.[2][4][5][n 1] Common aims were chrysopoeia, the transmutation of "base metals" (e.g., lead) into "noble metals" (particularly gold);[2] the creation of an elixir of immortality;[2] and the creation of panaceas able to cure any disease.[6] The perfection of the human body and soul was thought to result from the alchemical magnum opus ("Great Work").[2] The concept of creating the philosophers' stonewas variously connected with all of these projects.

Islamic and European alchemists developed a basic set of laboratory techniques, theories, and terms, some of which are still in use today. They did not abandon the Ancient Greek philosophical idea that everything is composed of four elements, and they tended to guard their work in secrecy, often making use of cyphers and cryptic symbolism. In Europe, the 12th-century translations of medieval Islamic works on science and the rediscovery of Aristotelian philosophy gave birth to a flourishing tradition of Latin alchemy.[2] This late medieval tradition of alchemy would go on to play a significant role in the development of early modern science (particularly chemistry and medicine).[7]

Modern discussions of alchemy are generally split into an examination of its exoteric practical applications and its esoteric spiritual aspects, despite criticisms by scholars such as Eric J. Holmyard and Marie-Louise von Franz that they should be understood as complementary.[8][9] The former is pursued by historians of the physical sciences, who examine the subject in terms of early chemistry, medicine, and charlatanism, and the philosophical and religious contexts in which these events occurred. The latter interests historians of esotericism, psychologists, and some philosophers and spiritualists. The subject has also made an ongoing impact on literature and the arts.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alchemy

A blacksmith is a metalsmith who creates objects primarily from wrought iron or steel, but sometimes from other metals, by forging the metal, using tools to hammer, bend, and cut (cf. tinsmith). Blacksmiths produce objects such as gates, grilles, railings, light fixtures, furniture, sculpture, tools, agricultural implements, decorative and religious items, cooking utensils, and weapons. There was an historical opposition between the heavy work of the blacksmith and the more delicate operation of a whitesmith, who usually worked in gold, silver, pewter, or the finishing steps of fine steel.[1] The place where a blacksmith works is called variously a smithy, a forge or a blacksmith's shop.

While there are many people who work with metal such as farriers, wheelwrights, and armorers, in former times the blacksmith had a general knowledge of how to make and repair many things, from the most complex of weapons and armor to simple things like nails or lengths of chain.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blacksmith

A whitesmith is a metalworker who does finishing work on iron and steel such as filing, lathing, burnishing or polishing.[1][2][3] The term also refers to a person who works with "white" or light-coloured metals, and is sometimes used as a synonym for tinsmith.[4]

History[edit]

The first known description of Whitesmith is from 1686: [5]

Whitesmithing developed as a speciality of blacksmithing in the 1700s, when extra time was given to filing and polishing certain products. In 1836 the trade was described by Isaac Taylor:[6]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Whitesmith

A tinsmith is a person who makes and repairs things made of tin or other light metals. The profession may sometimes also be known as a tinner, tinker, tinman, or tinplate worker; whitesmith may also refer to this profession,[1] though the same word may also refer to an unrelated specialty of iron-smithing. By extension it can also refer to the person who deals in tinware, or tin plate.[2] Tinsmith was a common occupation in pre-industrial times.

Unlike blacksmiths (who work mostly with hot metals), tinsmiths do the majority of their work on cold metal (although they might use a hearth to heat and help shape their raw materials). Tinsmiths fabricate items such as water pitchers, forks, spoons, and candle holders.

Training of tinsmiths[edit]

The tinsmith learned his trade, like many other artisans, by serving an apprenticeship of 4 to 6 years with a master tinsmith. Apprenticeships were considered "indentures" and an apprentice would start first with simply cleaning the shop, polishing tools, keeping the fires lit, filing sharp edges, and polishing finished pieces. Later he would trace patterns on sheets and cut them out, then soldering joints, and inserting rivets. Finally, he was allowed to cut out and complete objects.[3][page needed] He learned first to make cake stamps (cookie cutters), pillboxes and other simple items. Next, he formed objects such as milk pails, basins, or cake and pie pans. Later he tackled more complicated pieces such as chandeliers and crooked-spout coffee pots.

After his apprenticeship was completed, he then became a journeyman, not yet being a master smith employing others. Many young tinsmiths took to the road as peddlers or tinkers to save enough money to open a shop in town.

Raw material[edit]

Tinplate consists of sheet iron coated with tin and then run through rollers. This process was first discovered in the 16th century, with the development of the British tinplate address in 1661 with a patent to Dud Dudley and William Chamberlayne.[4][page needed] Previously Great Britain had imported most tinplate from Hamburg.

The British Iron Act of 1750 prohibited (among other things) the erection of new rolling mills, which prevented the erection of new tinplate works in America until after the American Revolution. Certificates submitted by colonial governors to the British Board of Trade following the Act indicate that no tinplate works then existed though there were several slitting mills, some described as slitting and rolling mills.

Pure tin is an expensive and soft metal and it is not practical to use it alone. However, it could be alloyed with lead and copper to make pewter or alloyed with copper alone to produce bronze. Today's tinplate is mild steel electroplated with tin. Tin's non-rusting qualities make it an invaluable coating. However, the tinplate's quality depends on the iron or steel is free from rust and the surface in an unbroken coating. A piece of tinware may develop rust if the tin coating has worn away or been cut in the metal. The respective properties of the metals mean that corrosion once started is likely to be rapid.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tinsmith

Metalworking

hidevte

Smithing

Smiths

Blacksmith Bladesmith Coppersmith Goldsmith Gunsmith Locksmith Pewtersmith Silversmith Tinsmith

Processes

Forging Pattern welding Planishing Raising Sinking Swaging

Tools

Anvil Forge Fuller Hammer Hardy tools Pritchel Steam hammer Swage block Trip hammer

Casting Fabrication Forming Jewellery Machining Metallurgy Smithing Tools and terminology Welding

Authority control Edit this at Wikidata

Integrated Authority File (Germany)

Categories: TinsmithsOccupationsMetalworking occupations

Pattern welding is the practice in sword and knife making of forming a blade of several metal pieces of differing composition that are forge-welded together and twisted and manipulated to form a pattern.[1] Often mistakenly called Damascus steel, blades forged in this manner often display bands of slightly different patterning along their entire length. These bands can be highlighted for cosmetic purposes by proper polishing or acid etching. Pattern welding was an outgrowth of laminated or piled steel, a similar technique used to combine steels of different carbon contents, providing a desired mix of hardness and toughness. Although modern steelmaking processes negate the need to blend different steels,[2] pattern welded steel is still used by custom knifemakers for the cosmetic effects it produces.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pattern_welding

A steam hammer, also called a drop hammer, is an industrial power hammer driven by steam that is used for tasks such as shaping forgings and driving piles. Typically the hammer is attached to a piston that slides within a fixed cylinder, but in some designs the hammer is attached to a cylinder that slides along a fixed piston.

The concept of the steam hammer was described by James Watt in 1784, but it was not until 1840 that the first working steam hammer was built to meet the needs of forging increasingly large iron or steel components. In 1843 there was an acrimonious dispute between François Bourdon of France and James Nasmyth of Britain over who had invented the machine. Bourdon had built the first working machine, but Nasmyth claimed it was built from a copy of his design.

Steam hammers proved to be invaluable in many industrial processes. Technical improvements gave greater control over the force delivered, greater longevity, greater efficiency and greater power. A steam hammer built in 1891 by the Bethlehem Iron Company delivered a 125-ton blow. In the 20th century steam hammers were gradually displaced in forging by mechanical and hydraulic presses, but some are still in use. Compressed air power hammers, descendants of the early steam hammers, are still manufactured.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Steam_hammer

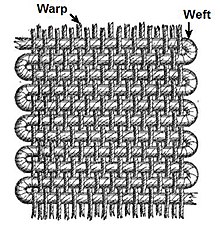

Weaving is a method of textile production in which two distinct sets of yarns or threads are interlaced at right angles to form a fabric or cloth. Other methods are knitting, crocheting, felting, and braiding or plaiting. The longitudinal threads are called the warp and the lateral threads are the weft, woof, or filling. (Weft is an old English word meaning "that which is woven"; compare leave and left.[a]) The method in which these threads are inter-woven affects the characteristics of the cloth.[1] Cloth is usually woven on a loom, a device that holds the warp threads in place while filling threads are woven through them. A fabric band that meets this definition of cloth (warp threads with a weft thread winding between) can also be made using other methods, including tablet weaving, back strap loom, or other techniques that can be done without looms.[2]

The way the warp and filling threads interlace with each other is called the weave. The majority of woven products are created with one of three basic weaves: plain weave, satin weave, or twill weave. Woven cloth can be plain or classic (in one colour or a simple pattern), or can be woven in decorative or artistic design.

Archaeology[edit]

There are some indications that weaving was already known in the Paleolithic Era, as early as 27,000 years ago. An indistinct textile impression has been found at the Dolní Věstonice site.[15] According to the find, the weavers of the Upper Palaeolithic were manufacturing a variety of cordage types, produced plaited basketry and sophisticated twined and plain woven cloth. The artifacts include imprints in clay and burned remnants of cloth.[16]

The oldest known textiles found in the Americas are remnants of six finely woven textiles and cordage found in Guitarrero Cave, Peru. The weavings, made from plant fibres, are dated between 10100 and 9080 BCE.[17][18]

In 2013 a piece of cloth woven from hemp was found in burial F. 7121 at the Çatalhöyük site,[19] suggested to be from around 7000 B.C.[20][21] Further finds come from the Neolithic civilisation preserved in the pile dwellings in Switzerland.[22]

Another extant fragment from the Neolithic was found in Fayum, at a site dated to about 5000 BCE.[23] This fragment is woven at about 12 threads by 9 threads per centimetre in a plain weave. Flax was the predominant fibre in Egypt at this time (3600 BCE) and had continued popularity in the Nile Valley, though wool became the primary fibre used in other cultures around 2000 BCE.[citation needed].

The oldest-known weavings in North America come from the Windover Archaeological Site in Florida. Dating from 4900 to 6500 B.C. and made from plant fibres, the Windover hunter-gatherers produced "finely crafted" twined and plain weave textiles.[24][25]Eighty-seven pieces of fabric were found associated with 37 burials.[citation needed] Researchers have identified seven different weaves in the fabric.[citation needed] One kind of fabric had 26 strands per inch (10 strands per centimetre). There were also weaves using two-strand and three-strand wefts. A round bag made from twine was found, as well as matting. The yarn was probably made from palm leaves. Cabbage palm, saw palmetto and scrub palmetto are all common in the area, and would have been so 8,000 years ago.[26][27]

Evidence of weaving as a commercial household industry in the historical region of Macedonia has been found at the Olynthus site. When the city was destroyed by Philip II in 348 BC, artifacts were preserved in the houses. Loomweights were found in many houses, enough to produce cloth to meet the needs of the household, but some of the houses contained more loomweights, enough for commercial production, and one of the houses was adjacent to the agora and contained three shops where many coins were found. It is probable that such homes were engaged in commercial textile manufacture.[28]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Weaving

The warp-weighted loom is a simple and ancient form of loom in which the warp yarns hang freely from a bar supported by upright poles which can be placed at a convenient slant against a wall. Bundles of warp threads are tied to hanging weights called loom weights which keep the threads taut.[1] Evidence of the warp-weighted loom appears in the Neolithicperiod in central Europe. It is depicted in artifacts of Bronze Age Greece and was common throughout Europe, remaining in use in Scandinavia into modern times. Loom weights from the Bronze Age were excavated in Miletos, a Greek city in Anatolia.[2]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Warp-weighted_loom

Subcategories

This category has the following 16 subcategories, out of 16 total.

Pages in category "Ancient Greek culture"

The following 62 pages are in this category, out of 62 total. This list may not reflect recent changes (learn more).

No comments:

Post a Comment