Crustaceans (Crustacea /krʌˈsteɪʃə/) form a large, diverse arthropod taxon which includes such animals as crabs, lobsters, crayfish, shrimps, prawns, krill, woodlice, and barnacles.[1] The crustacean group can be treated as a subphylum under the clade Mandibulata; because of recent molecular studies it is now well accepted that the crustacean group is paraphyletic, and comprises all animals in the clade Pancrustaceaother than hexapods.[2] Some crustaceans (Remipedia, Cephalocarida, Malacostraca) are more closely related to insects and the other hexapods than they are to certain other crustaceans.[3]

The 67,000 described species range in size from Stygotantulus stocki at 0.1 mm (0.004 in), to the Japanese spider crab with a leg span of up to 3.8 m (12.5 ft) and a mass of 20 kg (44 lb). Like other arthropods, crustaceans have an exoskeleton, which they moult to grow. They are distinguished from other groups of arthropods, such as insects, myriapods and chelicerates, by the possession of biramous (two-parted) limbs, and by their larval forms, such as the nauplius stage of branchiopods and copepods.

Most crustaceans are free-living aquatic animals, but some are terrestrial (e.g. woodlice), some are parasitic(e.g. Rhizocephala, fish lice, tongue worms) and some are sessile (e.g. barnacles). The group has an extensive fossil record, reaching back to the Cambrian, and includes living fossils such as Triops cancriformis, which has existed apparently unchanged since the Triassic period. More than 7.9 million tons of crustaceans per year are produced by fishery or farming for human consumption,[4] most of it being shrimp and prawns. Krill and copepods are not as widely fished, but may be the animals with the greatest biomass on the planet, and form a vital part of the food chain. The scientific study of crustaceans is known as carcinology (alternatively, malacostracology, crustaceology or crustalogy), and a scientist who works in carcinology is a carcinologist.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Crustacean

The Decapoda or decapods (literally "ten-footed") are an order of crustaceans within the class Malacostraca, including many familiar groups, such as crayfish, crabs, lobsters, prawns, and shrimp. Most decapods are scavengers. The order is estimated to contain nearly 15,000 species in around 2,700 genera, with around 3,300 fossil species.[1] Nearly half of these species are crabs, with the shrimp (about 3,000 species) and Anomuraincluding hermit crabs, porcelain crabs, squat lobsters (about 2500 species) making up the bulk of the remainder.[1] The earliest fossil decapod is the Devonian Palaeopalaemon.[2]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Decapoda

Crabs are decapod crustaceans of the infraorder Brachyura, which typically have a very short projecting "tail" (abdomen) (Greek: βραχύς, romanized: brachys = short,[2] οὐρά / οura = tail[3]), usually hidden entirely under the thorax. They live in all the world's oceans, in fresh water, and on land, are generally covered with a thick exoskeleton, and have a single pair of pincers. Many other animals with similar names – such as hermit crabs, king crabs, porcelain crabs, horseshoe crabs, stone crabs, and crab lice – are not true crabs, but many have evolved features similar to true crabs through a process known as carcinisation.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Crab

SAR or Harosa (informally the SAR supergroup) is a clade that includes stramenopiles (heterokonts), alveolates, and Rhizaria.[2][3][4][5] The name is an acronym derived from the first letters of each of these clades; it has been alternatively spelled "RAS".[6][7] The term "Harosa" (at the subkingdom level) has also been used.[8] The SAR supergroup was formulated as the node-based taxon[6].

Note that as a formal taxon, "Sar" has only its first letter capitalized, while the earlier abbreviation, SAR, retains all uppercase letters. Both names refer to the same group of organisms, unless further taxonomic revisions deem otherwise. Members of the SAR supergroup were once included under the separate supergroups Chromalveolata (Chromista and Alveolata) and Rhizaria, until phylogenetic studies confirmed that stramenopiles and alveolates diverged with Rhizaria.[9] This apparently excluded haptophytes and cryptomonads, leading Okamoto et al. (2009) to propose the clade Hacrobia to accommodate them.[10]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SAR_supergroup

Daphniidae is a family of water fleas in the suborder Anomopoda.

The family Daphniidae contains 121 species in five genera:[3][4][5]

- Ceriodaphnia Dana, 1853

- Daphnia O. F. Müller, 1785

- Megafenestra Dumont & Pensaert, 1983

- Scapholeberis Schoedler, 1858

- Simocephalus Schoedler, 1858

| Scapholeberis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scapholeberis sp., Japan | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Subphylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | Scapholeberis Schoedler, 1858 |

| Glassworm | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Aquatic larvae (above) and winged adult (below) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Diptera |

| Family: | Chaoboridae |

| Genus: | Chaoborus Lichtenstein, 1800 |

| Synonyms | |

Sayomyia Coquillett, 1903 | |

Cercopagis pengoi, or the fishhook waterflea, is a species of planktonic cladoceran crustaceans that is native in the brackish fringes of the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea.[2] In recent decades it has spread as an invasive species to some freshwater waterways and reservoirs of Eastern Europe and to the brackish Baltic Sea. Further it was introduced in ballast water to the Great Lakes of North America and a number of adjacent lakes, and has become a pest classified among the 100 worst invasive species of the world.[2]

Cercopagis pengoi is a predatory cladoceran and thus a competitor to other planktivorous invertebrates and smaller fishes. On the other hand, it has provided a new food source for planktivorous fishes. It is also a nuisance to fisheries as it tends to clog nets and fishing gear.[3]

| Cercopagis pengoi | |

|---|---|

| |

| Cercopagis pengoi (above, total length 10 mm) and Bythotrephes longimanus (below) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Subphylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | C. pengoi |

| Binomial name | |

| Cercopagis pengoi (Ostroumov, 1891) [1] | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Stramenopile is a clade of organisms distinguished by the presence of stiff tripartite external hairs. In most species, the hairs are attached to flagella, in some they are attached to other areas of the cellular surface, and in some they have been secondarily lost (in which case relatedness to stramenopile ancestors is evident from other shared cytological features or from genetic similarity). Stramenopiles represent one of the three major clades in the SAR supergroup, along with Alveolata and Rhizaria.

Members of the clade are referred to as 'stramenopiles'. Stramenopiles are eukaryotes; since they are neither fungi, animals, nor plants, they are classified as protists. Most stramenopiles are single-celled, but some are multicellular algae including some brown algae. The group includes a variety of algal protists, heterotrophic flagellates, opalinesand closely related proteromonad flagellates (all endobionts in other organisms); the actinophryid heliozoa, and oomycetes. The tripartite hairs have been lost in some stramenopiles - for example in most diatoms (although these organisms still express mastigonemic proteins - see below).

Many stramenopiles are unicellular flagellates, and most others produce flagellated cells at some point in their lifecycles, for instance as gametes or zoospores. Most flagellated heterokonts have two flagella; the anterior flagellum has one or two rows of stiff hairs or mastigonemes, and the posterior flagellum is without such embellishments, being smooth, usually shorter, or in a few cases not projecting from the cell.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stramenopile

Amoebozoa is a major taxonomic group containing about 2,400 described species of amoeboid protists,[2]often possessing blunt, fingerlike, lobose pseudopods and tubular mitochondrial cristae.[3][4] In most classification schemes, Amoebozoa is ranked as a phylum within either the kingdom Protista[5] or the kingdom Protozoa.[6] In the classification favored by the International Society of Protistologists, it is retained as an unranked "supergroup" within Eukaryota.[3] Molecular genetic analysis supports Amoebozoa as a monophyletic clade. Most phylogenetic trees identify it as the sister group to Opisthokonta, another major clade which contains both fungi and animals as well as some 300 species of unicellular protists.[2][4]Amoebozoa and Opisthokonta are sometimes grouped together in a high-level taxon, variously named Unikonta,[6] Amorphea[3] or Opimoda.[7]

| Amoebozoa | |

|---|---|

| |

| Chaos carolinensis | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| (unranked): | Unikonta |

| Phylum: | Amoebozoa Lühe, 1913 emend. Cavalier-Smith, 1998 |

| Subphyla, infraphyla and classes | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amoebozoa

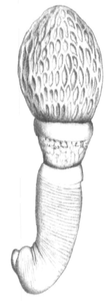

Dinobryon is a type of microscopic algae. It is one of the 22 genera in the family Dinobryaceae. Dinobryon are mixotrophs,[2] capable of obtaining energy and carbon through photosynthesis and phagotrophy of bacteria. The genus comprises at least 37 described species.[3] The best-known species are D. cylindricum and D. divergens, which come to the attention of humans annually due to transient blooms in the photic zone of temperate lakes and ponds. Such blooms may produce volatile organic compounds (VOCs) that produce odors and affect water quality.[4]

Dinobryon can exist as free-living, solitary cells or in branching colonies.

| Dinobryon | |

|---|---|

| |

| Dinobryon divergens | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Clade: | SAR |

| Phylum: | Ochrophyta |

| Class: | Chrysophyceae |

| Order: | Chromulinales |

| Family: | Dinobryaceae |

| Genus: | Dinobryon Ehrenb.[1] |

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dinobryon

Chaoboridae, commonly known as phantom midges or glassworms, is a family of fairly common midges with a cosmopolitan distribution. They are closely related to the Corethrellidae and Chironomidae; the adults are differentiated through peculiarities in wing venation.

If they eat at all, the adults feed on nectar. The larvae are aquatic and unique in their feeding method: the antennae of phantom midge larvae are modified into grasping organs slightly resembling the raptorial arms of a mantis, with which they capture prey. They feed largely on small insects such as mosquito larvae and crustaceans such as Daphnia. The antennae impale or crush the prey, and then bring it to the larval mouth, or stylet.

The larvae swim and sometimes form large swarms in their lacustrinehabitats.

| Chaoboridae | |

|---|---|

| |

| Chaoborus pupa | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Diptera |

| Infraorder: | Culicomorpha |

| Family: | Chaoboridae Edwards, 1912 |

| Subfamilies | |

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chaoboridae

The Spiralia are a morphologically diverse clade of protostome animals, including within their number the molluscs, annelids, platyhelminths and other taxa.[1] The term Spiralia is applied to those phyla that exhibit canonical spiral cleavage, a pattern of early development found in most (but not all) members of the Lophotrochozoa.[2]

| Spiralia | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Subkingdom: | Eumetazoa |

| Clade: | ParaHoxozoa |

| Clade: | Bilateria |

| Clade: | Nephrozoa |

| (unranked): | Protostomia |

| (unranked): | Spiralia sensu Edgecombe et al. 2011 |

| Clade | |

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spiralia

Deuterostomia /ˈdjuːtəroʊstoʊmiə/ (lit. 'second mouth' in Greek)[2][3] are animals typically characterized by their anus forming before their mouth during embryonic development. The group's sister clade is Protostomia, animals whose digestive tract development is more varied. Some examples of deuterostomes include vertebrates, sea stars, and crinoids.

In deuterostomy, the developing embryo's first opening (the blastopore) becomes the anus, while the mouth is formed at a different site later on. This was initially the group's distinguishing characteristic, but deuterostomy has since been discovered among protostomes as well.[4] This group is also known as enterocoelomates, because their coelom develops through enterocoely.

The three major clades of deuterostomes are Chordata (e.g. vertebrates), Echinodermata (e.g. starfish), and Hemichordata (e.g. acorn worms). Together with Protostomia and their out-group Xenacoelomorpha, these compose the Bilateria, animals with bilateral symmetry and three germ layers.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deuterostome

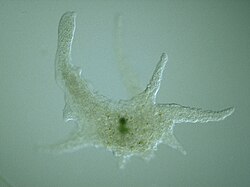

Brachionus calyciflorus is a planktonic rotifer species occurring in freshwater. It is commonly used as a model organism in toxicology, ecology and evolutionary biology.

Its advantages include the small size and short generation time (average generation time of B. calyciflorus is around 2.2 days at 24 °C).

| Brachionus calyciflorus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Rotifera |

| Class: | Monogononta |

| Order: | Ploima |

| Family: | Brachionidae |

| Genus: | Brachionus |

| Species: | B. calyciflorus |

| Binomial name | |

| Brachionus calyciflorus Pallas, 1766 | |

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brachionus_calyciflorus

Gnathifera (from the Greek gnáthos, “jaw”, and the Latin -fera, “bearing”) is a clade of generally small spiralianscharacterized by complex jaws made of chitin. It comprises the phyla Gnathostomulida, Rotifera, Micrognathozoa, and Chaetognatha.[1] It may also include the Cycliophora.[2]

Gnathiferans include some of the most abundant phyla. Rotifers are among the most diverse and abundant freshwater animals and chaetognaths are among the most abundant marine plankton.[3][4]

| Gnathifera | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Subkingdom: | Eumetazoa |

| Clade: | ParaHoxozoa |

| Clade: | Bilateria |

| Clade: | Nephrozoa |

| (unranked): | Protostomia |

| (unranked): | Spiralia |

| Clade: | Gnathifera Ahlrichs, 1995 |

| Phyla | |

| |

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gnathifera_(clade)

Archiacanthocephala is a class within the phylum of Acanthocephala.[2] They are parasitic worms that attach themselves to the intestinal wall of terrestrial vertebrates, including humans. They are characterised by the body wall and the lemnisci (which are a bundle of sensory nerve fibers), which have nuclei that divide without spindle formation or the appearance of chromosomes or it has a few amoebae-like giant nuclei. Typically, there are eight separate cement glands in the male which is one of the few ways to distinguish the dorsal and ventral sides of these organisms.

| Archiacanthocephala | |

|---|---|

| |

| Apororhynchus hemignathi | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Acanthocephala |

| Class: | Archiacanthocephala Meyer, 1931[1] |

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Archiacanthocephala

Xenacoelomorpha[2] /ˌzɛnəˌsɛloʊˈmɔːrfə/ is a small phylum of bilaterian invertebrate animals, consisting of two sister groups: xenoturbellids and acoelomorphs. This new phylum was named in February 2011 and suggested based on morphological synapomorphies (physical appearances shared by the animals in the clade),[3] which was then confirmed by phylogenomic analyses of molecular data (similarities in the DNA of the animals within the clade).[2][4]

| Xenacoelomorpha | |

|---|---|

| |

| Xenoturbella japonica, a xenacoelomorph member (xenoturbellids) | |

| |

| Proporus sp., another xenacoelomorph member (acoelomorphs) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Subkingdom: | Eumetazoa |

| Clade: | ParaHoxozoa |

| Clade: | Bilateria |

| Phylum: | Xenacoelomorpha Philippe et al. 2011[1] |

| Subphyla | |

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Xenacoelomorpha

Nematoida is a grouping of animals, including the roundworms and horsehair worms.[1][2]

| Nematoida | |

|---|---|

| |

| Paragordius tricuspidatus | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Subkingdom: | Eumetazoa |

| Clade: | ParaHoxozoa |

| Clade: | Bilateria |

| Clade: | Nephrozoa |

| (unranked): | Protostomia |

| Superphylum: | Ecdysozoa |

| Clade: | Nematoida Schmidt-Rhaesa, 1996 |

| Phyla | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nematoida

Xenoturbella japonica is a marine benthic worm-like species that belongs to the genus Xenoturbella. It has been discovered in western Pacific Ocean by a group of Japanese scientists from the University of Tsukuba. The species was described in 2017 in a study published in the journal BMC Evolutionary Biology,[1] and amended in 2018.[2]

Xenotrubella japonica is known for lacking respiratory, circulatory and an excretory system.[3][4][1]

| Xenoturbella japonica | |

|---|---|

| |

| X. japonica holotype female. The white arrowhead indicates the ring furrow. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Xenacoelomorpha |

| Family: | Xenoturbellidae |

| Genus: | Xenoturbella |

| Species: | X. japonica |

| Binomial name | |

| Xenoturbella japonica Nakano, Miyazawa, Maeno, Shiroishi, Kakui, Koyanagi, Kanda, Satoh, Omori & Kohtsuka, 2018 | |

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Xenoturbella_japonica

Nectonema is a genus of marine horsehair worms first described by Addison E. Verrill in 1879.[1] It is the only genus in the family Nectonematidae described by Henry B. Ward in 1892, in the order Nectonematoidea, and in the class Nectonematoida. The genus contains five species; all species have a parasitic larval stage inhabiting crustacean hosts and a free-living adult stage that swims in open water.[2][3]

| Nectonema | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Superphylum: | Ecdysozoa |

| Clade: | Nematoida |

| Phylum: | Nematomorpha |

| Class: | Nectonematoida |

| Order: | Nectonematoidea Rauther, 1930 |

| Family: | Nectonematidae Ward, 1892 |

| Genus: | Nectonema Verrill, 1879 |

| Species | |

N. agile | |

Spinochordodes tellinii is a parasitic nematomorph hairworm whose larvae develop in grasshoppers and crickets. This parasite is able to influence its host's behavior: once the parasite is grown, it causes its grasshopper host to jump into water, where the grasshopper will likely drown. The parasite then leaves its host; the adult worm lives and reproduces in water.[2] S. tellinii does not influence its host to actively seek water over large distances, but only when it is already close to water.[3]

The microscopic larvae are ingested by their insect hosts and develop inside them into worms that can be three to four times longer than the host.

The precise molecular mechanism underlying the modification of the host's behaviour is not yet known. A study in 2005 indicated that grasshoppers which contain the parasite express, or create, different proteins in their brains compared to uninfected grasshoppers. Some of these proteins have been linked to neurotransmitter activity, others to geotactic activity, or the body's response to changes in gravity. Furthermore, it appears that the parasite produces proteins from the Wnt family that act directly on the development of the central nervous system and are similar to proteins known from other insects, suggesting an instance of molecular mimicry.[4]

A similar parasitic worm is Paragordius tricuspidatus.[5]

| Spinochordodes tellinii | |

|---|---|

| |

| Spinochordodes tellinii with its bush-cricket host (Meconema thalassinum) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Nematomorpha |

| Class: | Gordioida |

| Order: | Gordioidea |

| Family: | Chordodidae |

| Subfamily: | Chordodinae |

| Genus: | Spinochordodes |

| Species: | S. tellinii |

| Binomial name | |

| Spinochordodes tellinii | |

| Meconema | |

|---|---|

| |

| Meconema thalassinum | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Orthoptera |

| Suborder: | Ensifera |

| Family: | Tettigoniidae |

| Tribe: | Meconematini |

| Genus: | Meconema Serville 1831[1] |

The Cladocera, commonly known as water fleas are an order of small crustaceans that feed on microscopic chunks of organic matter (excluding some predatory forms). [1]

Over 650 species have been recognised so far, with many more undescribed.[2][3][4][5] The oldest fossils of cladocerans date to the Jurassic, though their modern morphology suggests that they originated substantially earlier, during the Paleozoic. Some have also adapted to a life in the ocean, the only members of Branchiopoda to do so, even if several anostracans live in hypersaline lakes.[6] Most are 0.2–6.0 mm (0.01–0.24 in) long, with a down-turned head with a single median compound eye, and a carapace covering the apparently unsegmented thorax and abdomen. Most species show cyclical parthenogenesis, where asexual reproduction is occasionally supplemented by sexual reproduction, which produces resting eggs that allow the species to survive harsh conditions and disperse to distant habitats.

| Cladocera | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Subphylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Subclass: | |

| Superorder: | Cladocera Latreille, 1829 |

| Suborders | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

Eucladocera (no evidence for grouping together all other cladocerans as the sister taxon to the monotypic Haplopoda (Leptodora)) | |

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cladocera

Deinacanthon is a genus of the botanical family Bromeliaceae, subfamily Bromelioideae. The genus name is from the Greek “deinos” - terrible and “anthos” - flower.[1]

| Deinacanthon | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| (unranked): | |

| (unranked): | |

| (unranked): | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Subfamily: | |

| Genus: | Deinacanthon Mez |

| Species | |

See text | |

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deinacanthon

Delftia acidovorans is a Gram-negative, motile, non-sporulating, rod-shaped bacterium[1] known for its ability to biomineralize gold[2] and bioremediation characteristics.[3] It was first isolated from soil in Delft, Netherlands.[1] The bacterium was originally categorized as Psuedamonas acidovorans and Comamonas acidovorans before being reclassified as Delftia acidovorans.[4]

| Delftia acidovorans | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Binomial name | |

| Delftia acidovorans (den Dooren de Jong 1926) Wen et al. 1999 | |

| Type strain | |

| ATCC 15668T | |

| Synonyms | |

Comamonas acidovorans (den Dooren de Jong 1926) Tamaoka et al.1987 | |

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Delftia_acidovorans

Cupriavidus metallidurans strain CH34 (renamed from Ralstonia metallidurans[1] and previously known as Ralstonia eutropha and Alcaligenes eutrophus[2]) is a non-spore-forming, Gram-negative bacterium which is adapted to survive several forms of heavy metal stress.[3][4] [5]Therefore, it is an ideal subject to study heavy metal disturbance of cellular processes. This bacterium shows a unique combination of advantages not present in this form in other bacteria.

- Its genome has been fully sequenced (preliminary, annotated sequence data were obtained from the DOE Joint Genome Institute)

- It is not pathogenic, therefore, models of the cell can also be tested in artificial environments similar to its natural habitats.

- It is related to the plant pathogen Ralstonia solanacearum.[6]

- It is of ecological importance since related bacteria are predominant in mesophilic heavy metal-contaminated environments.[2][7]

- It is of industrial importance and used for heavy metal remediation and sensing.[4]

- It is an aerobic chemolithoautotroph, facultatively able to grow in a mineral salts medium in the presence of H2, O2, and CO2 without an organic carbon source.[8] The energy-providing subsystem of the cell under these conditions is composed only of the hydrogenase, the respiratory chain, and the F1F0-ATPase. This keeps this subsystem simple and clearly separated from the anabolic subsystems that starts with the Calvin cycle for CO2-fixation.

- It is able to degrade xenobiotics even in the presence of high heavy metal concentrations.[9]

- Finally, strain CH34 is adapted to the outlined harsh conditions by a multitude of heavy-metal resistance systems that are encoded by the two indigenous megaplasmids pMOL28 and pMOL30 on the bacterial chromosome(s).[3][4][10]

Also it plays a vital role, together with the species Delftia acidovorans, in the formation of gold nuggets, by precipitating metallic gold from a solution of gold(III) chloride, a compound highly toxic to most other microorganisms.[11][12][13]

| Cupriavidus metallidurans | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Binomial name | |

| Cupriavidus metallidurans Goris et al. 2001; Van Damme and Coenye 2004 | |

The Phyllopharyngea are a class of ciliates, including some which are extremely specialized. Motile cells typically have cilia restricted to the ventral surface, or some part thereof, arising from monokinetids with a characteristic ultrastructure. In both chonotrichs and suctoria, however, only newly formed cells are motile and the sessile adults have undergone considerable modifications of form and appearance. Chonotrichs, found mainly on crustaceans, are vase-shaped, with cilia restricted to a funnel leading down into the mouth. Mature suctorians lack cilia altogether, and initially were not classified as ciliates.

The mouths of Phyllopharyngea are characteristically surrounded by microtubular ribbons, called phyllae. Nematodesmata, rods found in several other classes of ciliates, occur among the subclass Phyllopharyngia, most of which are free-living. In others, the mouth is often modified to form an extensible tentacle, with toxic extrusomesat the tip. These are especially characteristic of the suctoria, which feed upon other ciliates, and are unique among them in having multiple mouths on each cell. They are also found in many rhynchodids which are mostly parasites of bivalves.

| Phyllopharyngea | |

|---|---|

| |

| Suctoria | |

| Scientific classification | |

| (unranked): | Diaphoretickes |

| Clade: | TSAR |

| Clade: | SAR |

| Infrakingdom: | Alveolata |

| Phylum: | Ciliophora |

| Class: | Phyllopharyngea de Puytorac et al.1974[1] |

| Typical orders | |

Subclass Phyllopharyngia | |

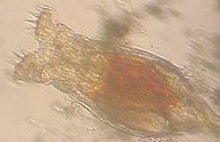

Ostracods, or ostracodes, are a class of the Crustacea (class Ostracoda), sometimes known as seed shrimp. Some 70,000 species (only 13,000 of which are extant) have been identified,[1] grouped into several orders. They are small crustaceans, typically around 1 mm (0.039 in) in size, but varying from 0.2 to 30 mm (0.008 to 1.181 in) in the case of Gigantocypris. Their bodies are flattened from side to side and protected by a bivalve-like, chitinousor calcareous valve or "shell". The hinge of the two valves is in the upper (dorsal) region of the body. Ostracods are grouped together based on gross morphology. While early work indicated the group may not be monophyletic;[2] and early molecular phylogeny was ambiguous on this front,[3] recent combined analyses of molecular and morphological data found support for monophyly in analyses with broadest taxon sampling.[4]

Ecologically, marine ostracods can be part of the zooplankton or (most commonly) are part of the benthos, living on or inside the upper layer of the sea floor. Many ostracods, especially the Podocopida, are also found in fresh water, and terrestrial species of Mesocypris are known from humid forest soils of South Africa, Australia and New Zealand.[5] They have a wide range of diets, and the group includes carnivores, herbivores, scavengers and filter feeders.

As of 2008, around 2000 species and 200 genera of nonmarine ostracods are found.[6] However, a large portion of diversity is still undescribed, indicated by undocumented diversity hotspots of temporary habitats in Africa and Australia.[7] Of the known specific and generic diversity of nonmarine ostracods, half (1000 species, 100 genera) belongs to one family (of 13 families), Cyprididae.[7] Many Cyprididae occur in temporary water bodies and have drought-resistant eggs, mixed/parthenogenetic reproduction, and the ability to swim. These biological attributes preadapt them to form successful radiations in these habitats.[8]

| Ostracod | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Subphylum: | Crustacea |

| Superclass: | Oligostraca |

| Class: | Ostracoda Latreille, 1802 |

| Subclasses and orders | |

| |

Ostracods, or ostracodes, are a class of the Crustacea (class Ostracoda), sometimes known as seed shrimp. Some 70,000 species (only 13,000 of which are extant) have been identified,[1] grouped into several orders. They are small crustaceans, typically around 1 mm (0.039 in) in size, but varying from 0.2 to 30 mm (0.008 to 1.181 in) in the case of Gigantocypris. Their bodies are flattened from side to side and protected by a bivalve-like, chitinousor calcareous valve or "shell". The hinge of the two valves is in the upper (dorsal) region of the body. Ostracods are grouped together based on gross morphology. While early work indicated the group may not be monophyletic;[2] and early molecular phylogeny was ambiguous on this front,[3] recent combined analyses of molecular and morphological data found support for monophyly in analyses with broadest taxon sampling.[4]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ostracod

Scalpellomorpha is an order of acorn barnacles in the class Thecostraca. There are about 11 families in 3 superfamilies and more than 450 described species in Scalpellomorpha.[1][2]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scalpellomorpha

Shallot latent virus (SLV), a species of Carlavirus, was first identified in shallots in Netherlands.[1] The virus particle is elongated, 650 nm in length.

| Shallot latent virus | |

|---|---|

| Virus classification | |

| (unranked): | Virus |

| Realm: | Riboviria |

| Kingdom: | Orthornavirae |

| Phylum: | Kitrinoviricota |

| Class: | Alsuviricetes |

| Order: | Tymovirales |

| Family: | Betaflexiviridae |

| Genus: | Carlavirus |

| Species: | Shallot latent virus |

Since its first detection in shallots, SLV has been found infecting garlic, onion, and leek on five continents.[2][3][4][5][6]In Indonesia, the virus has been identified in shallot, which is widely grown and used as a food ingredient, and also in garlic.[7] In Turkey, where shallot is less commonly cultivated, SLV was identified in onion in Amasya province instead.[8] However, SLV was not detected in onion samples collected in Ankara province.[9] Molecular study also detected SLV in other Allium species such as Allium cyathophorum, Allium moly, Allium scorodoprasum, and Allium senescens subsp. montanum.[10]

The virus is widespread in shallot and garlic without causing any clear symptoms, hence its name 'latent'. However, in mixed infection with leek yellow stripe virus (LYSV, Potyvirus) induces severe chlorotic and white stripes on shallot leaves.[1] The aphids Myzus ascalonicus and Aphis fabae transmit SLV in a non-persistent manner, but Myzus persicae does not transmit the virus.[1] It is also mechanically transmitted.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shallot_latent_virus

Myzus persicae, known as the green peach aphid, greenfly, or the peach-potato aphid,[2] is a small green aphid belonging to the order Hemiptera. It is the most significant aphid pest of peach trees, causing decreased growth, shrivelling of the leaves and the death of various tissues. It also acts as a vector for the transport of plant viruses such as cucumber mosaic virus (CMV), potato virus Y (PVY) and tobacco etch virus (TEV). Potato virus Y and potato leafroll virus can be passed to members of the nightshade/potato family (Solanaceae), and various mosaic viruses to many other food crops.[3]

Originally described by Swiss entomologist Johann Heinrich Sulzer in 1776, its specific name is derived from the Latin genitive persicae "of the peach".[4]

| Myzus persicae | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hemiptera |

| Suborder: | Sternorrhyncha |

| Family: | Aphididae |

| Genus: | Myzus |

| Species: | M. persicae |

| Binomial name | |

| Myzus persicae | |

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Myzus_persicae

Platysulcidae is a monotypic family of heterokonts that was recently discovered to be the earliest diverging lineage of the Heterokont phylogenetic tree.[1]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Platysulcidae

Oomycota or oomycetes (/ˌoʊəˈmaɪsiːts/[4]) form a distinct phylogenetic lineage of fungus-like eukaryoticmicroorganisms. They are filamentous and heterotrophic, and can reproduce both sexually and asexually. Sexual reproduction of an oospore is the result of contact between hyphae of male antheridia and female oogonia; these spores can overwinter and are known as resting spores.[5] Asexual reproduction involves the formation of chlamydospores and sporangia, producing motile zoospores.[5] Oomycetes occupy both saprophytic and pathogenic lifestyles, and include some of the most notorious pathogens of plants, causing devastating diseases such as late blight of potato and sudden oak death. One oomycete, the mycoparasitePythium oligandrum, is used for biocontrol, attacking plant pathogenic fungi.[6] The oomycetes are also often referred to as water molds (or water moulds), although the water-preferring nature which led to that name is not true of most species, which are terrestrial pathogens.

Oomycetes were originally grouped with fungi due to similarities in morphology and lifestyle. However, molecular and phylogenetic studies revealed significant differences between fungi and oomycetes which means the latter are now grouped with the stramenopiles (which include some types of algae). The Oomycota have a very sparse fossil record; a possible oomycete has been described from Cretaceousamber.[7]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oomycete

Aconchulinida[1] is an order of Cercozoa in the subclass Filosia. The outer zone is clear ectoplasm and has many vacuoles. It has a single nucleus. Its size range from 10 to 400 micrometers.[2] It contains few genera, possibly including only Penardia,[2] but usually also considered to encompass all of the Vampyrellidae.

| Aconchulinida | |

|---|---|

| |

| Vampyrella lateritia | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Clade: | SAR |

| Phylum: | Cercozoa |

| Class: | Proteomyxidea |

| Order: | Aconchulinida |

| Families | |

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aconchulinida

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Crustacean

The Cephalocarida are a class in the subphylum Crustacea comprising only 12 benthic species. They were discovered in 1955 by Howard L. Sanders,[1] and are commonly referred to as horseshoe shrimps. They have been grouped together with the Remipedia in the Xenocarida. Although a second family, Lightiellidae, is sometimes used, all cephalocaridans are generally considered to belong in just one family: Hutchinsoniellidae. Though no fossil record of cephalocaridans has been found, most specialists believe them to be primitive among crustaceans.

| Cephalocarida | |

|---|---|

| |

| Hutchinsoniella macracantha | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Subphylum: | Crustacea |

| Class: | Cephalocarida |

| Order: | Brachypoda |

| Family: | Hutchinsoniellidae Sanders, 1955 |

| Genera | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Taxonomy[edit]

- Class Cephalocarida Sanders 1955[2]

- Order Brachypoda Birshteyn 1960

- Family Hutchinsoniellidae Sanders 1955

- Genus Chiltoniella Knox & Fenwick 1977

- Chiltoniella elongata Knox & Fenwick 1977

- Genus Hampsonellus Hessler & Wakabara 2000

- Hampsonellus brasiliensis Hessler & Wakabara 2000

- Genus Hutchinsoniella Sanders 1955

- Hutchinsoniella macracantha Sanders 1955

- Genus Lightiella Jones 1961

- Lightiella floridana McLaughlin 1976

- Lightiella incisa Gooding 1963

- Lightiella magdalenina Carcupino et al. 2006

- Lightiella monniotae Cals & Delamare Deboutteville 1970

- Lightiella serendipita Jones 1961

- Genus Sandersiella Shiino 1965

- Sandersiella acuminata Shiino 1965

- Sandersiella bathyalis Hessler & Sanders 1973

- Sandersiella calmani Hessler & Sanders 1973

- Sandersiella kikuchii Shimomura & Akiyama 2008

Extant Arthropoda classes by subphylum | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chelicerata |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Myriapoda | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pancrustacea (Crustacea + Hexapoda) |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cephalocarida

The Protura, or proturans, and sometimes nicknamed coneheads,[2][3] are very small (<2 mm long), soil-dwelling animals, so inconspicuous they were not noticed until the 20th century. The Protura constitute an order of hexapods that were previously regarded as insects, and sometimes treated as a class in their own right.[1][4][5]

Some evidence indicates the Protura are basal to all other hexapods,[6] although not all researchers consider them Hexapoda, rendering the monophyly of Hexapoda unsettled.[7] Uniquely among hexapods, proturans show anamorphic development, whereby body segments are added during moults.[8]

There are close to 800 species, described in seven families. Nearly 300 species are contained in a single genus, Eosentomon.[1][9]

| Protura | |

|---|---|

| |

| Acerentomon species under stereo microscope | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Entognatha |

| Order: | Protura Silvestri, 1907 |

| Families [1] | |

Acerentomata Eosentomata | |

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Protura

A woodlouse (plural woodlice) is a crustacean from the monophyletic[2] suborder Oniscidea within the isopods. This name is descriptive of their being found in old wood.[3]

The first woodlice were marine isopods which are presumed to have colonised land in the Carboniferous, though the oldest known fossils are from the Cretaceous period.[4] They have many common names and although often referred to as terrestrial isopods, some species live semiterrestrially or have recolonised aquatic environments. Woodlice in the families Armadillidae, Armadillidiidae, Eubelidae, Tylidae and some other genera can roll up into a roughly spherical shape as a defensive mechanism; others have partial rolling ability but most cannot conglobate at all.

Woodlice have a basic morphology of a segmented, dorso-ventrally flattened body with seven pairs of jointed legs, specialised appendages for respiration and like other peracarids, females carry fertilised eggs in their marsupium, through which they provide developing embryos with water, oxygen and nutrients. The immature young hatch as mancae and receive further maternal care in some species. Juveniles then go through a series of moults before reaching maturity.

| Woodlice | |

|---|---|

| |

| Clockwise from top right: Ligia oceanica, Hemilepistus reaumuri, Platyarthrus hoffmannseggii and Schizidium tiberianum | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Subphylum: | Crustacea |

| Class: | Malacostraca |

| Superorder: | Peracarida |

| Order: | Isopoda |

| Suborder: | Oniscidea Latreille 1802[1] |

| Sections | |

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Woodlouse

Krill are small crustaceans of the order Euphausiacea, and are found in all the world's oceans. The name "krill" comes from the Norwegian word krill, meaning "small fry of fish",[1] which is also often attributed to species of fish.

Krill are considered an important trophic level connection – near the bottom of the food chain. They feed on phytoplankton and (to a lesser extent) zooplankton, yet also are the main source of food for many larger animals. In the Southern Ocean, one species, the Antarctic krill, Euphausia superba, makes up an estimated biomass of around 379,000,000 tonnes,[2] making it among the species with the largest total biomass. Over half of this biomass is eaten by Whales, seals, Penguins, squid, and fish each year. Most krill species display large daily vertical migrations, thus providing food for predators near the surface at night and in deeper waters during the day.

Krill are fished commercially in the Southern Ocean and in the waters around Japan. The total global harvest amounts to 150,000–200,000 tonnes annually, most of this from the Scotia Sea. Most of the krill catch is used for aquaculture and aquarium feeds, as bait in sport fishing, or in the pharmaceutical industry. In Japan, the Philippines, and Russia, krill are also used for human consumption and are known as okiami (オキアミ) in Japan. They are eaten as camarones in Spain and Philippines. In the Philippines, krill are also known as alamang and are used to make a salty paste called bagoong.

Krill are also the main prey of baleen whales, including the blue whale.

| Krill | |

|---|---|

| |

| Northern krill (Meganyctiphanes norvegica) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Subphylum: | Crustacea |

| Class: | Malacostraca |

| Superorder: | Eucarida |

| Order: | Euphausiacea Dana, 1852 |

| Families and genera | |

| |

| Amphipoda | |

|---|---|

| |

| Gammarus roeselii | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Subphylum: | Crustacea |

| Class: | Malacostraca |

| Subclass: | Eumalacostraca |

| Superorder: | Peracarida |

| Order: | Amphipoda Latreille, 1816[1] |

| Suborders | |

Traditional division[2] Revised division (2013)[1] | |

Crayfish are freshwater crustaceans resembling small lobsters (to which they are related). In some locations, they are also known as crawfish, craydids, crawdaddies, crawdads, freshwater lobsters, mountain lobsters, rock lobsters, mudbugs, or yabbies. Taxonomically, they are members of the superfamilies Astacoidea and Parastacoidea. They breathe through feather-like gills. Some species are found in brooks and streams, where fresh water is running, while others thrive in swamps, ditches, and paddy fields. Most crayfish cannot tolerate polluted water, although some species, such as Procambarus clarkii, are hardier. Crayfish feed on animals and plants, either living or decomposing, and detritus.[1]

The term "crayfish" is applied to saltwater species in some countries.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Crayfish

The glaucophytes, also known as glaucocystophytes or glaucocystids, are a small group of freshwater unicellular algae,[1] less common today than they were during the Proterozoic.[2] Only 15 species have been described, but more species are likely to exist.[3] Together with the red algae (Rhodophyta) and the green algaeplus land plants (Viridiplantae or Chloroplastida), they form the Archaeplastida. However, the relationships among the red algae, green algae and glaucophytes are unclear,[4] in large part due to limited study of the glaucophytes.[5]

The glaucophytes are of interest to biologists studying the development of chloroplasts because some studies suggest they may be similar to the original algal type that led to green plants and red algae in that they may be basal Archaeplastida.[1][6]

Unlike red and green algae, glaucophytes only have asexual reproduction.[7]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Glaucophyte

Shellfish is a colloquial and fisheries term for exoskeleton-bearing aquatic invertebrates used as food, including various species of molluscs, crustaceans, and echinoderms. Although most kinds of shellfish are harvested from saltwater environments, some are found in freshwater. In addition, a few species of land crabs are eaten, for example Cardisoma guanhumi in the Caribbean. Shellfish are among the most common food allergens.[1]

Despite the name, shellfish are not fish. Most shellfish are low on the food chain and eat a diet composed primarily of phytoplankton and zooplankton.[2] Many varieties of shellfish, and crustaceans in particular, are actually closely related to insects and arachnids; crustaceans make up one of the main subphyla of the phylum Arthropoda. Molluscs include cephalopods (squids, octopuses, cuttlefish) and bivalves (clams, oysters), as well as gastropods(aquatic species such as whelks and winkles; land species such as snails and slugs).

Molluscs used as a food source by humans include many species of clams, mussels, oysters, winkles, and scallops. Some crustaceans that are commonly eaten are shrimp, lobsters, crayfish, and crabs.[3] Echinodermsare not as frequently harvested for food as molluscs and crustaceans; however, sea urchin roe is quite popular in many parts of the world, where the live delicacy is harder to transport.[4][5]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shellfish

Mussel (/ˈmʌsəl/) is the common name used for members of several families of bivalve molluscs, from saltwater and freshwater habitats. These groups have in common a shell whose outline is elongated and asymmetrical compared with other edible clams, which are often more or less rounded or oval.

The word "mussel" is frequently used to mean the bivalves of the marine family Mytilidae, most of which live on exposed shores in the intertidal zone, attached by means of their strong byssal threads ("beard") to a firm substrate.[1] A few species (in the genus Bathymodiolus) have colonised hydrothermal vents associated with deep ocean ridges.

In most marine mussels the shell is longer than it is wide, being wedge-shaped or asymmetrical. The external colour of the shell is often dark blue, blackish, or brown, while the interior is silvery and somewhat nacreous.

The common name "mussel" is also used for many freshwater bivalves, including the freshwater pearl mussels. Freshwater mussel species inhabit lakes, ponds, rivers, creeks, canals, and they are classified in a different subclass of bivalves, despite some very superficial similarities in appearance.

Freshwater zebra mussels and their relatives in the family Dreissenidae are not related to previously mentioned groups, even though they resemble many Mytilus species in shape, and live attached to rocks and other hard surfaces in a similar manner, using a byssus. They are classified with the Heterodonta, the taxonomic group which includes most of the bivalves commonly referred to as "clams".

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mussel

Whelk (also known as scungilli)[1] is a common name that is applied to various kinds of sea snail.[2] Although a number of whelks are relatively large and are in the family Buccinidae (the true whelks), the word whelk is also applied to some other marine gastropod species within several families of sea snails that are not very closely related.

Many have historically been used, or are still used, by humans and other animals for food. In a 100-gram (31⁄2-ounce) reference serving of whelk, there are 570 kilojoules (137 kilocalories) of food energy, 24 g of protein, 0.34 g of fat, and 8 g of carbohydrates.[3]

Dog whelks were used in antiquity to make a rich red dye that improves in color as it ages.[4]

True whelks are carnivorous, feeding on worms, crustaceans, mussels and other molluscs, drilling holes through shells to gain access to the soft tissues. Whelks use chemoreceptors to locate their prey.[5]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Whelk

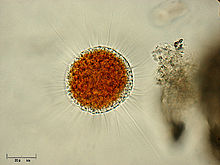

The dinoflagellates (Greek δῖνος dinos "whirling" and Latin flagellum "whip, scourge") are single-celled eukaryotes constituting the phylum Dinoflagellata[5] and usually considered algae. Dinoflagellates are mostly marine plankton, but they also are common in freshwater habitats. Their populations vary with sea surface temperature, salinity, and depth. Many dinoflagellates are photosynthetic, but a large fraction of these are in fact mixotrophic, combining photosynthesis with ingestion of prey (phagotrophy and myzocytosis).[6][7]

In terms of number of species, dinoflagellates are one of the largest groups of marine eukaryotes, although substantially smaller than diatoms.[8] Some species are endosymbionts of marine animals and play an important part in the biology of coral reefs. Other dinoflagellates are unpigmented predators on other protozoa, and a few forms are parasitic (for example, Oodinium and Pfiesteria). Some dinoflagellates produce resting stages, called dinoflagellate cysts or dinocysts, as part of their lifecycles, and is known from 84 of the 350 described freshwater species, and from a little more than 10% of the known marine species.[9][10] Dinoflagellates are alveolatespossessing two flagella, the ancestral condition of bikonts.

About 1,555 species of free-living marine dinoflagellates are currently described.[11] Another estimate suggests about 2,000 living species, of which more than 1,700 are marine (free-living, as well as benthic) and about 220 are from fresh water.[12] The latest estimates suggest a total of 2,294 living dinoflagellate species, which includes marine, freshwater, and parasitic dinoflagellates.[2]

A rapid accumulation of certain dinoflagellates can result in a visible coloration of the water, colloquially known as red tide (a harmful algal bloom), which can cause shellfish poisoning if humans eat contaminated shellfish. Some dinoflagellates also exhibit bioluminescence—primarily emitting blue-green light. Thus, some parts of the Indian Ocean light up at night giving blue-green light.

| Dinoflagellate | |

|---|---|

| |

| Ceratium sp. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Clade: | SAR |

| Infrakingdom: | Alveolata |

| Phylum: | Myzozoa |

| Subphylum: | Dinozoa |

| Superclass: | Dinoflagellata Bütschli 1885 [1880-1889] sensu Gomez 2012[2][3][4] |

| Classes | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

| Peripatus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Onychophora |

| Class: | Udeonychophora |

| Order: | Euonychophora |

| Family: | Peripatidae |

| Genus: | Peripatus Guilding, 1826 |

| Species | |

See text | |

| Barnacle | |

|---|---|

| |

| Chthamalus stellatus | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Subphylum: | Crustacea |

| Class: | Thecostraca |

| Subclass: | Cirripedia Burmeister, 1834 |

| Infraclasses | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

Thyrostraca, Cirrhopoda, Cirrhipoda, and Cirrhipedia. | |

| Argulidae | |

|---|---|

| |

| Argulus sp. on a stickleback | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Subphylum: | Crustacea |

| Class: | Maxillopoda |

| Subclass: | Branchiura |

| Order: | Arguloida Yamaguti, 1963 |

| Family: | Argulidae Leach, 1819 |

| Genera & species | |

See text | |

Classification[edit]

The 173 recognised species are divided among six genera.[5] The centres of diversity are the Afrotropical and Neotropical realms.[3]

Argulus O. F. Müller, 1785:[6]

- Argulus africanus Thiele, 1900

- Argulus alexandrensis C. B. Wilson, 1923

- Argulus alosae Gould, 1841

- Argulus amazonicus Malta & Santos-Silva, 1986

- Argulus ambloplites C. B. Wilson, 1920

- Argulus ambystoma Poly, 2003

- Argulus americanus C. B. Wilson, 1902

- Argulus angusticeps Cunnington, 1913

- Argulus annae Schuurmans Stekhoven J.H. Jr, 1951

- Argulus appendiculosus C. B. Wilson, 1907

- Argulus arcassonensis Cuénot, 1912

- Argulus argulus Leach, 1814

- Argulus armiger O. F. Müller, 1785

- Argulus australiensis Byrnes, 1985

- Argulus belones Kampen, 1909

- Argulus bengalensis Ramakrishna, 1951

- Argulus bicolor Bere, 1936

- Argulus biramosus Bere, 1931

- Argulus boli Tripathi, 1975

- Argulus borealis C. B. Wilson, 1912

- Argulus brachypeltis Fryer, 1959

- Argulus caecus C. B. Wilson, 1922

- Argulus canadensis C. B. Wilson, 1916

- Argulus capensis Barnard, 1955

- Argulus carteri Cunnington, 1931

- Argulus catostomi Dana & Herrick, 1837

- Argulus cauveriensis Thomas & Devaraj, 1975

- Argulus charon O. F. Müller, 1785

- Argulus chesapeakensis Cressey, 1971

- Argulus chicomendesi Malta & Varella, 2000

- Argulus chilensis Martinez, 1952

- Argulus chinensis Ku & Yang, 1955

- Argulus chromidis Kroyer, 1863

- Argulus confuscus Rushton-Mellor, 1994

- Argulus coregoni Thorell, 1865

- Argulus cubensis C. B. Wilson, 1936

- Argulus dactylopteri Thorell, 1865

- Argulus dageti Dollfus, 1960

- Argulus dartevellei Brian, 1940

- Argulus delphinus O. F. Müller, 1785

- Argulus diversicolor Byrnes, 1985

- Argulus diversus C. B. Wilson, 1944

- Argulus ellipticaudatus K. N. Wang, 1960

- Argulus elongatus Heller, 1857

- Argulus ernsti Weibezahn & Cobo, 1964

- Argulus exiguus Cunnington, 1913

- Argulus flavescens C. B. Wilson, 1916

- Argulus floridensis Meehan, 1940

- Argulus fluviatilis Thomas & Devaraj, 1975

- Argulus foliaceus (Linnaeus, 1758)

- Argulus fryeri Rushton-Mellor, 1994

- Argulus funduli Krøyer, 1863

- Argulus fuscus Bere, 1936

- Argulus giordanii Brian, 1959

- Argulus gracilis Rushton-Mellor, 1994

- Argulus hylae Lemos de Castro & Gomes-Correa, 1985

- Argulus ichesi Bouvier, 1910

- Argulus incisus Cunnington, 1913

- Argulus indicus Weber, 1892

- Argulus ingens C. B. Wilson, 1912

- Argulus intectus C. B. Wilson, 1944

- Argulus izintwala J. G. Van As & L. L. Van As, 2001

- Argulus japonicus Thiele, 1900

- Argulus jollymani Fryer, 1956

- Argulus juparanensis Lemos de Castro, 1950

- Argulus kosus Avenant-Oldewage, 1994

- Argulus kunmingensis Shen, 1948

- Argulus kusafugu Yamaguti& Yamasu, 1959

- Argulus laticauda S. I. Smith, 1874

- Argulus latus S. I. Smith, 1874

- Argulus lepidostei Kellicott, 1877

- Argulus longicaudatus C. B. Wilson, 1944

- Argulus lunatus C. B. Wilson, 1944

- Argulus macropterus Heegaard, 1962

- Argulus maculosus C. B. Wilson, 1902

- Argulus major K. N. Wang, 1960

- Argulus mangalorensis Natarajan, 1982

- Argulus matuii Sikama, 1938

- Argulus meehani Cressey, 1971

- Argulus megalops S. I. Smith, 1874

- Argulus melanostictus C. B. Wilson, 1935

- Argulus melita Beneden, 1891

- Argulus mexicanus Pineda, Paramo & del Rio, 1995

- Argulus mississippiensis C. B. Wilson, 1916

- Argulus mongolianus Tokioka, 1939

- Argulus monodi Fryer, 1959

- Argulus multicolor Schuurmans Stekhoven J.H. Jr, 1937

- Argulus multipocula Barnard, 1955

- Argulus nativus Kirtisinghe, 1959

- Argulus natterei Heller, 1857

- Argulus niger C. B. Wilson, 1902

- Argulus nobilis Thiele, 1904

- Argulus onodai Tokioka, 1936

- Argulus papuensis Rushton-Mellor, 1994

- Argulus paranensis Ringuelet, 1943

- Argulus parsi Tripathi, 1975

- Argulus paulensis C. B. Wilson, 1924

- Argulus personatus Cunnington, 1913

- Argulus pestifer Ringuelet, 1948

- Argulus petagonicus Ringuelet, 1943

- Argulus phoxini Leydig, 1871

- Argulus piperatus C. B. Wilson, 1920

- Argulus pugettensis Dana, 1852

- Argulus puthenveliensis Ramakrishna, 1959

- Argulus quadristriatus Devaraj & Ameer Hamsa, 1977

- Argulus reticulatus C. B. Wilson, 1920

- Argulus rhamdiae C. B. Wilson, 1936

- Argulus rhipidiophorus Monod, 1931

- Argulus rijckmansii Brian, 1940

- Argulus rotundus C. B. Wilson, 1944

- Argulus rubescens Cunnington, 1913

- Argulus rubropunctatus Cunnington, 1913

- Argulus salminei Kroyer, 1863

- Argulus scutiformis Thiele, 1900

- Argulus shoutedeni Monod, 1928

- Argulus siamensis C. B. Wilson, 1926

- Argulus silvestrii Lahille, 1926

- Argulus smalei Avenant-Oldewage & Oldewage, 1995

- Argulus spinulosus Silva, 1980

- Argulus stizostethii Kellicott, 1880

- Argulus striatus Cunnington, 1913

- Argulus taliensis Shen, 1948

- Argulus tientsinensis Ku & Wang, 1956

- Argulus trachynoti Brian, 1927

- Argulus trilineatus C. B. Wilson, 1904

- Argulus varians Bere, 1936

- Argulus versicolor C. B. Wilson, 1902

- Argulus vierai Pereira-Fonseca, 1939

- Argulus violaceus Thomsen, 1925

- Argulus vittatus (Rafinesque-Schmaltz, 1814)

- Argulus wilsoni Brian, 1940

- Argulus yucatanus Poly, 2005

- Argulus yucatanus Poly, 2004

- Argulus yuii K. N. Wang, 1958

- Argulus yunnanensis Shen, 1948

Binoculus Geoffroy St. Hilaire, 1762:[7]

- Binoculus bicornutus Risso, 1816

- Binoculus caudatus Say, 1818

- Binoculus gasterostei Geoffroy, 1762

- Binoculus haemisphericus Geoffroy, 1762

- Binoculus palustris O. F. Müller, 1776

- Binoculus piscinus O. F. Müller, 1776

- Binoculus productus Nordmann, 1832

- Binoculus salmoneus O. F. Müller, 1785

- Binoculus sexsetaceus Nordmann, 1832

Chonopeltis Thiele, 1900:[8]

- Chonopeltis australis Boxshall, 1976

- Chonopeltis australissumus Fryer, 1977

- Chonopeltis brevis Fryer, 1961

- Chonopeltis congicus Fryer, 1959

- Chonopeltis elongatus Fryer, 1974

- Chonopeltis flaccifrons Fryer, 1960

- Chonopeltis fryeri Van As, 1986

- Chonopeltis inermis Thiele, 1900

- Chonopeltis koki Van As, 1992

- Chonopeltis lisikili J. G. Van As & L. L. Van As, 1996

- Chonopeltis meridionalis Fryer, 1964

- Chonopeltis minutus Fryer, 1977

- Chonopeltis schoutedeni Brian, 1940

- Chonopeltis victori Avenant-Oldewage, 1991

Dipteropeltis Callman, 1912:[9]

- Dipteropeltis hirundo Calman, 1912

- Dolops bidentata (Bouvier, 1899)

- Dolops carvalhoi Lemos de Castro, 1949

- Dolops discoidalis Bouvier, 1899

- Dolops doradis (Cornalia, 1860)

- Dolops geayi (Bouvier, 1897)

- Dolops intermedia da Silva, 1978

- Dolops kollari (Heller, 1857)

- Dolops lacordairei Audouin, 1837

- Dolops longicauda (Heller, 1857)

- Dolops nana Lemos de Castro, 1950

- Dolops ranarum (Stuhlmann, 1891)

- Dolops reperta (Bouvier, 1899)

- Dolops striata (Bouvier, 1899)

- Dolops tasmanicus Fryer, 1969

- Huargulus chinensis Yü, 1938

Copepods (/ˈkoʊpɪpɒd/; meaning "oar-feet") are a group of small crustaceans found in nearly every freshwaterand saltwater habitat. Some species are planktonic (inhabiting sea waters), some are benthic (living on the ocean floor), a number of species have parasitic phases, and some continental species may live in limnoterrestrial habitats and other wet terrestrial places, such as swamps, under leaf fall in wet forests, bogs, springs, ephemeral ponds, and puddles, damp moss, or water-filled recesses (phytotelmata) of plants such as bromeliads and pitcher plants. Many live underground in marine and freshwater caves, sinkholes, or stream beds. Copepods are sometimes used as biodiversity indicators.

As with other crustaceans, copepods have a larval form. For copepods, the egg hatches into a nauplius form, with a head and a tail but no true thorax or abdomen. The larva molts several times until it resembles the adult and then, after more molts, achieves adult development. The nauplius form is so different from the adult form that it was once thought to be a separate species. The metamorphosis had, until 1832, led to copepods being misidentified as zoophytes or insects (albeit aquatic ones), or, for parasitic copepods, 'fish lice'.[1]

| Copepod | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Subphylum: | Crustacea |

| Class: | Hexanauplia |

| Subclass: | Copepoda H. Milne-Edwards, 1840 |

| Orders | |

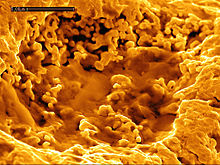

n addition to being parasites themselves, copepods are subject to parasitic infection. The most common parasite is the marine dinoflagellates, Blastodinium spp., which are gut parasites of many copepod species.[21][22] Currently, 12 species of Blastodinium are described, the majority of which were discovered in the Mediterranean Sea.[21] Most Blastodinium species infect several different hosts, but species-specific infection of copepods does occur. Generally, adult copepod females and juveniles are infected.

During the naupliar stage, the copepod host ingests the unicellular dinospore of the parasite. The dinospore is not digested and continues to grow inside the intestinal lumen of the copepod. Eventually, the parasite divides into a multicellular arrangement called a trophont.[23] This trophont is considered parasitic, contains thousands of cells, and can be several hundred micrometers in length.[22] The trophont is greenish to brownish in color as a result of well-defined chloroplasts. At maturity, the trophont ruptures and Blastodinium spp. are released from the copepod anus as free dinospore cells. Not much is known about the dinospore stage of Blastodinium and its ability to persist outside of the copepod host in relatively high abundances.[24]

The copepod Calanus finmarchicus, which dominates the northeastern Atlantic coast, has been shown to be greatly infected by this parasite. A 2014 study in this region found up to 58% of collected C. finmarchicus females to be infected.[23] In this study, Blastodinium-infected females had no measurable feeding rate over a 24-hour period. This is compared to uninfected females which, on average, ate 2.93 × 104 cells copepod−1 d−1.[23] Blastodinium-infected females of C. finmarchicus exhibited characteristic signs of starvation, including decreased respiration, fecundity, and fecal pellet production. Though photosynthetic, Blastodinium spp. procure most of their energy from organic material in the copepod gut, thus contributing to host starvation.[22]Underdeveloped or disintegrated ovaries, as well as decreased fecal pellet size, are a direct result of starvation in female copepods.[25] Infection from Blastodinium spp. could have serious ramifications on the success of copepod species and the function of entire marine ecosystems. Parasitism via Blastodinium spp.' is not lethal, but has negative impacts on copepod physiology, which in turn may alter marine biogeochemical cycles.

Freshwater copepods of the Cyclops genus are the intermediate host of Dracunculus medinensis, the Guinea worm nematode that causes dracunculiasisdisease in humans. This disease may be close to being eradicated through efforts at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization.[26]

Live copepods are used in the saltwater aquarium hobby as a food source and are generally considered beneficial in most reef tanks. They are scavengers and also may feed on algae, including coralline algae. Live copepods are popular among hobbyists who are attempting to keep particularly difficult species such as the mandarin dragonet or scooter blenny. They are also popular to hobbyists who want to breed marine species in captivity. In a saltwater aquarium, copepods are typically stocked in the refugium.

Copepods are sometimes found in public main water supplies, especially systems where the water is not mechanically filtered,[27] such as New York City, Boston, and San Francisco.[28] This is not usually a problem in treated water supplies. In some tropical countries, such as Peru and Bangladesh, a correlation has been found between copepods' presence and cholera in untreated water, because the cholera bacteria attach to the surfaces of planktonic animals. The larvae of the guinea worm must develop within a copepod's digestive tract before being transmitted to humans. The risk of infection with these diseases can be reduced by filtering out the copepods (and other matter), for example with a cloth filter.[29]

Copepods have been used successfully in Vietnam to control disease-bearing mosquitoes such as Aedes aegypti that transmit dengue fever and other human parasitic diseases.[30][31]

The copepods can be added to water-storage containers where the mosquitoes breed.[27] Copepods, primarily of the genera Mesocyclops and Macrocyclops (such as Macrocyclops albidus), can survive for periods of months in the containers, if the containers are not completely drained by their users. They attack, kill, and eat the younger first- and second-instar larvae of the mosquitoes. This biological control method is complemented by community trash removal and recycling to eliminate other possible mosquito-breeding sites. Because the water in these containers is drawn from uncontaminated sources such as rainfall, the risk of contamination by cholera bacteria is small, and in fact no cases of cholera have been linked to copepods introduced into water-storage containers. Trials using copepods to control container-breeding mosquitoes are underway in several other countries, including Thailand and the southern United States. The method, though, would be very ill-advised in areas where the guinea worm is endemic.

The presence of copepods in the New York City water supply system has caused problems for some Jewish people who observe kashrut. Copepods, being crustaceans, are not kosher, nor are they quite small enough to be ignored as nonfood microscopic organisms, since some specimens can be seen with the naked eye. When a group of rabbis in Brooklyn, New York, discovered the copepods in the summer of 2004, they triggered such debate in rabbinic circles that some observant Jews felt compelled to buy and install filters for their water.[32] The water was ruled kosher by posek Yisrael Belsky.[33]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Copepod

Etymology[edit]

Noun[edit]

dinospore (plural dinospores)

- (microbiology) A spore produced through multiple fission of a dinomastigote

Coordinate terms[edit]

Anagrams[edit]

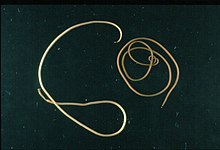

Dracunculus medinensis, or Guinea worm, is a nematode that causes dracunculiasis, also known as guinea worm disease.[1] The disease is caused by the female[2] which, at up to 80 centimetres (31 inches) in length,[3] is among the longest nematodes infecting humans.[4] In contrast, the longest recorded male Guinea worm is only 4 cm (11⁄2 in).[3]

Guinea worm is on target to be the second infectious disease to be eradicated. It was formerly endemic to a wide swath of Africa and Eurasia; as of 2021, it remains endemic in five countries: Chad, Ethiopia, Mali, South Sudan and Angola, with most cases in Chad and Ethiopia. Guinea worm spread to Angola in ca. 2018, and it is now considered endemic there. Infection of domestic dogs is a serious complication in Chad.

The common name "guinea worm" is derived from the Guinea region of Western Africa.

| Guinea worm | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Nematoda |

| Class: | Secernentea |

| Order: | Camallanida |

| Family: | Dracunculidae |

| Genus: | Dracunculus |

| Species: | D. medinensis |

| Binomial name | |

| Dracunculus medinensis | |

| Synonyms | |

Macrocyclops albidus is a larvivorous copepod species.

Ecology[edit]

It makes its habitat in still fresh waters such as in residential roadside ditches, pools, ponds, and other environments with sufficient food supply.

Macrocyclopsis feed on mosquito larvae. Macrocyclops albidus has proven highly efficient in controlling mosquitoes, reaching close to 90% reduction in larval survival under field conditions and exceeding the recommended predation rates for effective mosquito control in laboratory experiments.[2] In laboratory studies, the common Macrocyclopsis killed an average of 27 first-instar Culex quinquefasciatus larvae/copepod/day.[3]

Macrocyclops albidus is a known intermediate host for the hermaphroditic parasite Schistocephalus solidus, a tapeworm of fish and fish-eating birds.

Classification[edit]

Macrocyclops is a member of Crustacea: Copepoda. The genus Macrocyclops is characterized by a fifth leg of two distinct segments, the distal segment bearing three spines or setae on its terminal end.[4] Macrocyclops albidus is distinguished by the bare medial surface of the caudal rami and the hyaline membrane on the last segment of the antennule, which is smooth or finely serrated.[4]

| Macrocyclops albidus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Subphylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Subclass: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | M. albidus |

| Binomial name | |

| Macrocyclops albidus | |

No comments:

Post a Comment