Chitons /ˈkaɪtənz/ are marine molluscs of varying size in the class Polyplacophora /ˌpɒlipləˈkɒfərə/,[3] formerly known as Amphineura.[4] About 940[5][6] extant and 430[7] fossil species are recognized.

They are also sometimes known as sea cradles or "coat-of-mail shells", or more formally as loricates, polyplacophorans, and occasionally as polyplacophores.

Chitons have a shell composed of eight separate shell plates or valves.[3] These plates overlap slightly at the front and back edges, and yet articulate well with one another. Because of this, the shell provides protection at the same time as permitting the chiton to flex upward when needed for locomotion over uneven surfaces, and even allows the animal to curl up into a ball when dislodged from rocks.[8] The shell plates are encircled by a skirt known as a girdle.

| Chiton | |

|---|---|

| |

| A live lined chiton, Tonicella lineataphotographed in situ: The anterior end of the animal is to the right. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Mollusca |

| Class: | Polyplacophora Blainville, 1816 |

| Subgroups | |

The primary sense organs of chitons are the subradular organ and a large number of unique organs called aesthetes. The aesthetes consist of light-sensitive cells just below the surface of the shell, although they are not capable of true vision. In some cases, however, they are modified to form ocelli, with a cluster of individual photoreceptor cells lying beneath a small aragonite-based lens.[18] Each lens can form clear images, and is composed of relatively large, highly crystallographically-aligned grains to minimize light scattering.[19] An individual chiton may have thousands of such ocelli.[16] These aragonite-based eyes[20] make them capable of true vision;[21] though research continues as to the extent of their visual acuity. It is known that they can differentiate between a predator's shadow and changes in light caused by clouds. An evolutionary trade-off has led to a compromise between the eyes and the shell; as the size and complexity of the eyes increase, the mechanical performance of their shells decrease, and vice versa.[22]

A relatively good fossil record of chiton shells exists, but ocelli are only present in those dating to 10 million years ago or younger; this would make the ocelli, whose precise function is unclear, likely the most recent eyes to evolve.[2]

Although chitons lack osphradia, statocysts, and other sensory organs common to other molluscs, they do have numerous tactile nerve endings, especially on the girdle and within the mantle cavity.

The order Lepidopleurida also have a pigmented sensory organ called the Schwabe organ, but its function still remains unknown.[23]

However, chitons lack a cerebral ganglion.[24]

A chiton creeps along slowly on a muscular foot. It has considerable power of adhesion and can cling to rocks very powerfully, like a limpet.

Chitons are generally herbivorous grazers, though some are omnivorous and some carnivorous.[30][31] They eat algae, bryozoans, diatoms, barnacles, and sometimes bacteria by scraping the rocky substrate with their well-developed radulae.

A few species of chitons are predatory, such as the small western Pacific species Placiphorella velata. These predatory chitons have enlarged anterior girdles. They catch other small invertebrates, such as shrimp and possibly even small fish, by holding the enlarged, hood-like front end of the girdle up off the surface, and then clamping down on unsuspecting, shelter-seeking prey.[32]

Chitons have separate sexes, and fertilization is usually external. The male releases sperm into the water, while the female releases eggs either individually, or in a long string. In most cases, fertilization takes place either in the surrounding water, or in the mantle cavity of the female. Some species brood the eggs within the mantle cavity, and the species Callistochiton viviparus even retains them within the ovary and gives birth to live young, an example of ovoviviparity.

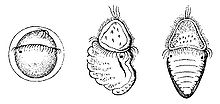

The egg has a tough spiny coat, and usually hatches to release a free-swimming trochophore larva, typical of many other mollusc groups. In a few cases, the trochophore remains within the egg (and is then called lecithotrophic – deriving nutrition from yolk), which hatches to produce a miniature adult. Unlike most other molluscs, there is no intermediate stage, or veliger, between the trochophore and the adult. Instead, a segmented shell gland forms on one side of the larva, and a foot forms on the opposite side. When the larva is ready to become an adult, the body elongates, and the shell gland secretes the plates of the shell. Unlike the fully grown adult, the larva has a pair of simple eyes, although these may remain for some time in the immature adult.[16]

Animals which prey on chitons include humans, seagulls, sea stars, crabs, lobsters and fish.[citation needed]

The name "chiton" is New Latin derived from the Ancient Greek word khitōn, meaning tunic (which also is the source of the word chitin). The Ancient Greek word khitōn can be traced to the Central Semitic word *kittan, which is from the Akkadian words kitû or kita'um, meaning flax or linen, and originally the Sumerian word gada or gida.[citation needed]

The Greek-derived name Polyplacophora comes from the words poly- (many), plako- (tablet), and -phoros (bearing), a reference to the chiton's eight shell plates.

Aragonite is a carbonate mineral, one of the three most common naturally occurring crystal forms of calcium carbonate, CaCO3 (the other forms being the minerals calcite and vaterite). It is formed by biological and physical processes, including precipitation from marine and freshwater environments.

The crystal lattice of aragonite differs from that of calcite, resulting in a different crystal shape, an orthorhombic crystal system with acicular crystal. Repeated twinning results in pseudo-hexagonal forms. Aragonite may be columnar or fibrous, occasionally in branching helictitic forms called flos-ferri ("flowers of iron") from their association with the ores at the Carinthian iron mines.[4]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aragonite

Aesthetes are organs in chitons, derived from the mantle of the organism. They are generally believed to be tiny 'eyes', too small to be seen unaided, embedded in the organism's shell,[1] acting in unison to function as a large, dispersed, compound eye.[2] However, in 2013 studies suggested that aesthetes may serve the function of releasing material to repair the periostracum, a proteinaceous material covering the shell and protecting it from abrasion.[3] This turned out to be false, as it was conclusively demonstrated in November 2015, that aesthetes are image forming eyes.[4] This layer is constantly worn away by waves and debris as a function of their rugged habitat, and must be continuously replaced to protect the shell. Some chitons also have larger lens-bearing eyes.[2]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aesthete_(chiton)

A trochophore (/ˈtroʊkəˌfɔːr, ˈtrɒ-, -koʊ-/;[1][2] also spelled trocophore) is a type of free-swimming planktonicmarine larva with several bands of cilia.

By moving their cilia rapidly, a water eddy is created. In this way they control the direction of their movement. Additionally, in this way they bring their food closer, in order to capture it more easily.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trochophore

Chitin (C8H13O5N)n (/ˈkaɪtɪn/ KY-tin) is a long-chain polymer of N-acetylglucosamine, an amide derivative of glucose. This polysaccharide is a primary component of cell walls in fungi, the exoskeletons of arthropods, such as crustaceans and insects, the radulae of molluscs, cephalopod beaks, and the scales of fish and skin of lissamphibians,[1] making it the second most abundant polysaccharide in nature,[2] behind only cellulose. The structure of chitin is comparable to cellulose, forming crystalline nanofibrils or whiskers. It is functionally comparable to the protein keratin. Chitin has proved useful for several medicinal, industrial and biotechnological purposes.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chitin

A veliger is the planktonic larva of many kinds of sea snails and freshwater snails, as well as most bivalvemolluscs (clams) and tusk shells.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Veliger

- "Isopoda". WoRMS. World Register of Marine Species. 2014. Retrieved 8 May 2014.

- ^ "Isopod". Merriam-Webster. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 27 June 2014.

No comments:

Post a Comment