| Disco | |

|---|---|

The ceiling of a discothèque in Arlington, Texas | |

| Stylistic origins | |

| Cultural origins | Late 1960s – early 1970s, Philadelphia and New York City[1] |

| Derivative forms | |

| Subgenres | |

| Fusion genres | |

| Regional scenes | |

| Local scenes | |

| |

| Other topics | |

Disco is a genre of dance music and a subculture that emerged in the 1970s from the United States' urban nightlife scene. Its sound is typified by four-on-the-floor beats, syncopated basslines, string sections, brass and horns, electric piano, synthesizers, and electric rhythm guitars.

Disco started as a mixture of music from venues popular with LGBTQ Americans, Italian Americans, Hispanic and Latino Americans, and black Americans[5] in Philadelphia and New York City during the late 1960s and early 1970s. Disco can be seen as a reaction by the 1960s counterculture to both the dominance of rock music and the stigmatization of dance music at the time. Several dance styles were developed during the period of disco's popularity in the United States, including "the Bump" and "the Hustle".

In the course of the 1970s, disco music was developed further, mainly by artists from the United States and Europe. Well-known artists included the Bee Gees, Donna Summer, Gloria Gaynor, Giorgio Moroder, Baccara, Boney M., Earth Wind & Fire, Chaka Khan, Chic, KC and the Sunshine Band, Thelma Houston, Sister Sledge, Sylvester, The Trammps, Diana Ross, Kool and the Gang & Village People.[6][7] While performers garnered public attention, record producers working behind the scenes played an important role in developing the genre. By the late 1970s, most major U.S. cities had thriving disco club scenes, and DJs would mix dance records at clubs such as Studio 54 in Manhattan, a venue popular among celebrities. Nightclub-goers often wore expensive, extravagant outfits, consisting predominantly of loose, flowing pants or dresses for ease of movement while dancing. There was also a thriving drug subculture in the disco scene, particularly for drugs that would enhance the experience of dancing to the loud music and the flashing lights, such as cocaine and quaaludes, the latter being so common in disco subculture that they were nicknamed "disco biscuits". Disco clubs were also associated with promiscuity as a reflection of the sexual revolution of this era in popular history. Films such as Saturday Night Fever (1977) and Thank God It's Friday (1978) contributed to disco's mainstream popularity.

Disco declined as a major trend in popular music in the United States following the infamous Disco Demolition Night, and it continued to sharply decline in popularity in the U.S. during the early 1980s; however, it remained popular in Italy and some European countries throughout the 1980s, and during this time also started becoming trendy in places elsewhere including India[8] and the Middle East,[9] where aspects of disco were blended with regional folk styles such as ghazals and belly dancing. Disco would eventually become a key influence in the development of electronic dance music, house music, hip hop, new wave, dance-punk, and post-disco. The style has had several revivals since the 1990s, and the influence of disco remains strong across American and European pop music. A revival has been underway since the early 2010s, coming to great popularity in the early 2020s. Albums that have contributed to this revival include Confessions On A Dance Floor, Random Access Memories, The Slow Rush, Cuz I Love You, Future Nostalgia, Hey U X, Melodrama, What's Your Pleasure?, About Last Night..., Róisín Machine, and Kylie Minogue's album itself titled Disco.[10][11][12][13]

Etymology

The term "disco" is shorthand for the word discothèque, a French word for "library of phonograph records" derived from "bibliothèque". The word "discothèque" had the same meaning in English in the 1950s.

"Discothèque" became used in French for a type of nightclub in Paris, after they had resorted to playing records during the Nazi occupation in the early 1940s. Some clubs used it as their proper name. In 1960, it was also used to describe a Parisian nightclub in an English magazine.

In the summer of 1964, a short sleeveless dress called the "discotheque dress" was briefly very popular in the United States. The earliest known use for the abbreviated form "disco" described this dress and has been found in The Salt Lake Tribune on July 12, 1964, Playboy magazine used it in September of the same year to describe Los Angeles nightclubs.[14]

Vince Aletti was one of the first to describe disco as a sound or a music genre. He wrote the feature article "Discotheque Rock Paaaaarty" that appeared in Rolling Stone magazine in September 1973.[15][16][17]

Musical characteristics

The music typically layered soaring, often-reverberated vocals, often doubled by horns,[citation needed] over a background "pad" of electric pianos and "chicken-scratch" rhythm guitars played on an electric guitar. Lead guitar features less frequently in disco than in rock. "The "rooster scratch" sound is achieved by lightly pressing the guitar strings against the fretboard and then quickly releasing them just enough to get a slightly muted poker [sound] while constantly strumming very close to the bridge."[18] Other backing keyboard instruments include the piano, electric organ (during early years), string synthesizers, and electromechanical keyboards such as the Fender Rhodes electric piano, Wurlitzer electric piano, and Hohner Clavinet. Donna Summer's 1977 song "I Feel Love", produced by Giorgio Moroder with a prominent Moog synthesizer on the beat, was one of the first disco tracks to use the synthesizer.[19]

The rhythm is laid down by prominent, syncopated basslines (with heavy use of broken octaves, that is, octaves with the notes sounded one after the other) played on the bass guitar and by drummers using a drum kit, African/Latin percussion, and electronic drums such as Simmons and Roland drum modules. The sound was enriched with solo lines and harmony parts played by a variety of orchestral instruments, such as harp, violin, viola, cello, trumpet, saxophone, trombone, clarinet, flugelhorn, French horn, tuba, English horn, oboe, flute (sometimes especially the alto flute and occasionally flute), piccolo, timpani and synth strings, string section or a full string orchestra.[citation needed]

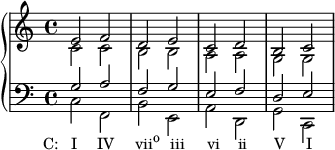

Most disco songs have a steady four-on-the-floor beat set by a bass drum, a quaver or semi-quaver hi-hat pattern with an open hissing hi-hat on the off-beat, and a heavy, syncopated bass line.[20][21] A recording error in the 1975 song "Bad Luck" by Harold Melvin & the Blue Notes where Earl Young's hi-hat was too loud in the recording is said to have established loud hi-hats in disco.[20] Other Latin rhythms such as the rhumba, the samba, and the cha-cha-cha are also found in disco recordings, and Latin polyrhythms, such as a rhumba beat layered over a merengue, are commonplace. The quaver pattern is often supported by other instruments such as the rhythm guitar and may be implied rather than explicitly present.

Songs often use syncopation, which is the accenting of unexpected beats. In general, the difference between disco, or any dance song, and a rock or popular song is that in dance music the bass drum hits four to the floor, at least once a beat (which in 4/4 time is 4 beats per measure).[citation needed] Disco is further characterized by a 16th note division of the quarter notes as shown in the second drum pattern below, after a typical rock drum pattern.

The orchestral sound usually known as "disco sound" relies heavily on string sections and horns playing linear phrases, in unison with the soaring, often reverberated vocals or playing instrumental fills, while electric pianos and chicken-scratch guitars create the background "pad" sound defining the harmony progression. Typically, all of the doubling of parts and use of additional instruments creates a rich "wall of sound". There are, however, more minimalist flavors of disco with reduced, transparent instrumentation.

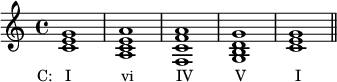

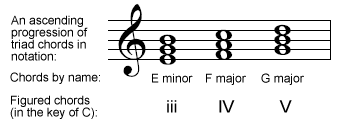

Harmonically, disco music typically contains major and minor seven chords,[citation needed] which are found more often in jazz than pop music.

Production

The "disco sound" was much more costly to produce than many of the other popular music genres from the 1970s. Unlike the simpler, four-piece-band sound of funk, soul music of the late 1960s or the small jazz organ trios, disco music often included a large band, with several chordal instruments (guitar, keyboards, synthesizer), several drum or percussion instruments (drumkit, Latin percussion, electronic drums), a horn section, a string orchestra, and a variety of "classical" solo instruments (for example, flute, piccolo, and so on).

Disco songs were arranged and composed by experienced arrangers and orchestrators, and record producers added their creative touches to the overall sound using multitrack recording techniques and effects units. Recording complex arrangements with such a large number of instruments and sections required a team that included a conductor, copyists, record producers, and mixing engineers. Mixing engineers had an important role in the disco production process because disco songs used as many as 64 tracks of vocals and instruments. Mixing engineers and record producers, under the direction of arrangers, compiled these tracks into a fluid composition of verses, bridges, and refrains, complete with builds and breaks. Mixing engineers and record producers helped to develop the "disco sound" by creating a distinctive-sounding, sophisticated disco mix.

Early records were the "standard" three-minute version until Tom Moulton came up with a way to make songs longer so that he could take a crowd of dancers at a club to another level and keep them dancing longer. He found that it was impossible to make the 45-RPM vinyl singles of the time longer, as they could usually hold no more than five minutes of good-quality music. With the help of José Rodriguez, his remaster/mastering engineer, he pressed a single on a 10" disc instead of 7". They cut the next single on a 12" disc, the same format as a standard album. Moulton and Rodriguez discovered that these larger records could have much longer songs and remixes. 12" single records, also known as "Maxi singles", quickly became the standard format for all DJs of the disco genre.[22]

Club culture

Nightclubs

By the late 1970s, most major US cities had thriving disco club scenes. The largest scenes were most notably in New York City but also in Philadelphia, San Francisco, Miami, and Washington, D.C. The scene was centered on discotheques, nightclubs and private loft parties.

In the 1970s, notable discos included "Crisco Disco", "The Sanctuary", "Leviticus", "Studio 54", and "Paradise Garage" in New York, "Artemis" in Philadelphia, "Studio One" in Los Angeles, "Dugan's Bistro" in Chicago, and "The Library" in Atlanta.[23][24]

In the late '70s, Studio 54 in Midtown Manhattan was arguably the best-known nightclub in the world. This club played a major formative role in the growth of disco music and nightclub culture in general. It was operated by Steve Rubell and Ian Schrager and was notorious for the hedonism that went on within: the balconies were known for sexual encounters and drug use was rampant. Its dance floor was decorated with an image of the "Man in the Moon" that included an animated cocaine spoon.

The "Copacabana", another New York nightclub dating to the 1940s, had a revival in the late 1970s when it embraced disco; it would become the setting of a Barry Manilow song of the same name.

In Washington, D.C., large disco clubs such as "The Pier" ("Pier 9") and "The Other Side", originally regarded exclusively as "gay bars", became particularly popular among the capital area's gay and straight college students in the late '70s.

By 1979 there were 15,000-20,000 disco nightclubs in the US, many of them opening in suburban shopping centers, hotels, and restaurants. The 2001 Club franchises were the most prolific chain of disco clubs in the country.[25] Although many other attempts were made to franchise disco clubs, 2001 was the only one to successfully do so in this time frame.[26]

Sound and light equipment

Powerful, bass-heavy, hi-fi sound systems were viewed as a key part of the disco club experience. "[Loft-party host David] Mancuso introduced the technologies of tweeter arrays (clusters of small loudspeakers, which emit high-end frequencies, positioned above the floor) and bass reinforcements (additional sets of subwoofers positioned at ground level) at the start of the 1970s to boost the treble and bass at opportune moments, and by the end of the decade sound engineers such as Richard Long had multiplied the effects of these innovations in venues such as the Garage."[27]

Typical lighting designs for disco dance floors include multi-colored lights that swirl around or flash to the beat, strobe lights, an illuminated dance floor, and a mirror ball.

DJs

Disco-era disc jockeys (DJs) would often remix existing songs using reel-to-reel tape machines, and add in percussion breaks, new sections, and new sounds. DJs would select songs and grooves according to what the dancers wanted, transitioning from one song to another with a DJ mixer and using a microphone to introduce songs and speak to the audiences. Other equipment was added to the basic DJ setup, providing unique sound manipulations, such as reverb, equalization, and echo effects unit. Using this equipment, a DJ could do effects such as cutting out all but the bassline of a song and then slowly mixing in the beginning of another song using the DJ mixer's crossfader. Notable U.S. disco DJs include Francis Grasso of The Sanctuary, David Mancuso of The Loft, Frankie Knuckles of the Chicago Warehouse, Larry Levan of the Paradise Garage, Nicky Siano, Walter Gibbons, Karen Mixon Cook, Jim Burgess, John "Jellybean" Benitez, Richie Kulala of Studio 54, and Rick Salsalini.

Some DJs were also record producers who created and produced disco songs in the recording studio. Larry Levan, for example, was a prolific record producer as well as a DJ. Because record sales were often dependent on dance floor play by DJs in the nightclubs, DJs were also influential in the development and popularization of certain types of disco music being produced for record labels.

Dance

In the early years, dancers in discos danced in a "hang loose" or "freestyle" approach. At first, many dancers improvised their own dance styles and dance steps. Later in the disco era, popular dance styles were developed, including the "Bump", "Penguin", "Boogaloo", "Watergate", and "Robot". By October 1975 the Hustle reigned. It was highly stylized, sophisticated, and overtly sexual. Variations included the Brooklyn Hustle, New York Hustle, and Latin Hustle.[24]

During the disco era, many nightclubs would commonly host disco dance competitions or offer free dance lessons. Some cities had disco dance instructors or dance schools, which taught people how to do popular disco dances such as "touch dancing", "the hustle", and "the cha cha". The pioneer of disco dance instruction was Karen Lustgarten in San Francisco in 1973. Her book The Complete Guide to Disco Dancing (Warner Books 1978) was the first to name, break down and codify popular disco dances as dance forms and distinguish between disco freestyle, partner, and line dances. The book topped the New York Times bestseller list for 13 weeks and was translated into Chinese, German, and French.

In Chicago, the Step By Step disco dance TV show was launched with the sponsorship support of the Coca-Cola company. Produced in the same studio that Don Cornelius used for the nationally syndicated dance/music television show, Soul Train, Step by Step's audience grew and the show became a success. The dynamic dance duo of Robin and Reggie led the show. The pair spent the week teaching disco dancing to dancers in the disco clubs. The instructional show aired on Saturday mornings and had a strong following. Its viewers would stay up all night on Fridays so they could be on the set the next morning, ready to return to the disco on Saturday night knowing with the latest personalized steps. The producers of the show, John Reid and Greg Roselli, routinely made appearances at disco functions with Robin and Reggie to scout out new dancing talent and promote upcoming events such as "Disco Night at White Sox Park".

In Sacramento, California, Disco King Paul Dale Roberts danced for the Guinness Book of World Records. He danced for 205 hours, the equivalent of 8½ days. Other dance marathons took place afterward and Roberts held the world record for disco dancing for a short period of time.[28]

Some notable professional dance troupes of the 1970s included Pan's People and Hot Gossip. For many dancers, a key source of inspiration for 1970s disco dancing was the film Saturday Night Fever (1977). Further influence came from the music and dance style of such films as Fame (1980), Disco Dancer (1982), Flashdance (1983), and The Last Days of Disco (1998). Interest in disco dancing also helped spawn dance competition TV shows such as Dance Fever (1979).

Fashion

Disco fashions were very trendy in the late 1970s. Discothèque-goers often wore glamorous, expensive, and extravagant fashions for nights out at their local disco club. Some women would wear sheer, flowing dresses, such as Halston dresses, or loose, flared pants. Other women wore tight, revealing, sexy clothes, such as backless halter tops, disco pants, "hot pants", or body-hugging spandex bodywear or "catsuits".[29] Men would wear shiny polyester Qiana shirts with colorful patterns and pointy, extra wide collars, preferably open at the chest. Men often wore Pierre Cardin suits, three piece suits with a vest, and double-knit polyester shirt jackets with matching trousers known as the leisure suit. Men's leisure suits were typically form-fitted to some parts of the body, such as the waist and bottom while the lower part of the pants were flared in a bell bottom style, to permit freedom of movement.[29]

During the disco era, men engaged in elaborate grooming rituals and spent time choosing fashion clothing, activities that would have been considered "feminine" according to the gender stereotypes of the era.[29] Women dancers wore glitter makeup, sequins, or gold lamé clothing that would shimmer under the lights.[29] Bold colors were popular for both genders. Platform shoes and boots for both genders and high heels for women were popular footwear.[29] Necklaces and medallions were a common fashion accessory. Less commonly, some disco dancers wore outlandish costumes, dressed in drag, covered their bodies with gold or silver paint, or wore very skimpy outfits leaving them nearly nude; these uncommon get-ups were more likely to be seen at invitation-only New York City loft parties and disco clubs.[29]

Drug subculture

In addition to the dance and fashion aspects of the disco club scene, there was also a thriving club drug subculture, particularly for drugs that would enhance the experience of dancing to the loud, bass-heavy music and the flashing colored lights, such as cocaine[30] (nicknamed "blow"), amyl nitrite ("poppers"),[31] and the "... other quintessential 1970s club drug Quaalude, which suspended motor coordination and gave the sensation that one's arms and legs had turned to 'Jell-O.'"[32] Quaaludes were so popular at disco clubs that the drug was nicknamed "disco biscuits".[33]

Paul Gootenberg states that "[t]he relationship of cocaine to 1970s disco culture cannot be stressed enough..."[30] During the 1970s, the use of cocaine by well-to-do celebrities led to its "glamorization" and to the widely held view that it was a "soft drug".[34] LSD, marijuana, and "speed" (amphetamines) were also popular in disco clubs, and the use of these drugs "...contributed to the hedonistic quality of the dance floor experience."[35] Since disco dances were typically held in liquor licensed-nightclubs and dance clubs, alcoholic drinks were also consumed by dancers; some users intentionally combined alcohol with the consumption of other drugs, such as Quaaludes, for a stronger effect.

Eroticism and sexual liberation

According to Peter Braunstein, the "massive quantities of drugs ingested in discothèques produced the next cultural phenomenon of the disco era: rampant promiscuity and public sex. While the dance floor was the central arena of seduction, actual sex usually took place in the nether regions of the disco: bathroom stalls, exit stairwells, and so on. In other cases the disco became a kind of 'main course' in a hedonist's menu for a night out."[32] At The Saint nightclub, a high percentage of the gay male dancers and patrons would have sex in the club; they typically had unprotected sex, because in 1980, HIV-AIDS had not yet been identified.[36] At The Saint, "dancers would elope to an un[monitored] upstairs balcony to engage in sex."[36] The promiscuity and public sex at discos was part of a broader trend towards exploring a freer sexual expression in the 1970s, an era that is also associated with "swingers clubs, hot tubs, [and] key parties."[37]

In his paper, "In Defense of Disco" (1979), Richard Dyer claims eroticism as one of the three main characteristics of disco.[38] As opposed to rock music which has a very phallic centered eroticism focusing on the sexual pleasure of men over other persons, Dyer describes disco as featuring a non-phallic full body eroticism.[38] Through a range of percussion instruments, a willingness to play with rhythm, and the endless repeating of phrases without cutting the listener off, disco achieved this full-body eroticism by restoring eroticism to the whole body for both sexes.[38] This allowed for the potential expression of sexualities not defined by the cock/penis, and the erotic pleasure of bodies that are not defined by a relationship to a penis.[38] The sexual liberation expressed through the rhythm of disco is further represented in the club spaces that disco grew within.

In Peter Shapiro's Modulations: A History of Electronic Music: Throbbing Words on Sound, he discusses eroticism through the technology disco utilizes to create its audacious sound.[39] The music, Shapiro states, is adjunct to "the pleasure-is-politics ethos of post-Stonewall culture." He explains how "mechano-eroticism", which links the technology used to create the unique mechanical sound of disco to eroticism, set the genre in a new dimension of reality living outside of naturalism and heterosexuality.

He uses Donna Summer's singles "Love to Love You Baby" (1975) and "I Feel Love" (1977) as examples of the ever-present relationship between the synthesized bass lines and backgrounds to the simulated sounds of orgasms. Summer's voice echoes in the tracks, and likens them to the drug-fervent, sexually liberated fans of disco who sought to free themselves through disco's "aesthetic of machine sex."[40] Shapiro sees this as an influence that creates sub-genres like hi-NRG and dub-disco, which allowed for eroticism and technology to be further explored through intense synth bass lines and alternative rhythmic techniques that tap into the entire body rather than the obvious erotic parts of the body.

The New York nightclub The Sanctuary under resident DJ Francis Grasso is a prime example of this sexual liberty. In their history of the disc jockey and club culture, Bill Brewster and Frank Broughton describe the Sanctuary as "poured full of newly liberated gay men, then shaken (and stirred) by a weighty concoction of dance music and pharmacoia of pills and potions, the result is a festivaly of carnality."[41] The Sanctuary was the "first totally uninhibited gay discotheque in America" and while sex was not allowed on the dancefloor, the dark corners, bathrooms. and hallways of the adjacent buildings were all utilized for orgy-like sexual engagements.[41]

By describing the music, drugs, and liberated mentality as a trifecta coming together to create the festival of carnality, Brewster and Broughton are inciting all three as stimuli for the dancing, sex, and other embodied movements that contributed to the corporeal vibrations within the Sanctuary. It supports the argument that disco music took a role in facilitating this sexual liberation that was experienced in the discotheques. The recent legalization of abortion and the introduction of antibiotics and the pill facilitated a culture shift around sex from one of procreation to pleasure and enjoyment. Thus was fostered a very sex-positive framework around discotheques.[42]

Further, in addition to gay sex being illegal in New York state, until 1973 the American Psychiatric Association classified homosexuality as an illness.[41] This law and classification coupled together can be understood to have heavily dissuaded the expression of queerness in public, as such the liberatory dynamics of discotheques can be seen as having provided space for self-realization for queer persons. David Mancuso's club/house party, The Loft, was described as having a "pansexual attitude [that] was revolutionary in a country where up until recently it had been illegal for two men to dance together unless there was a woman present; where women were legally obliged to wear at least one recognizable item of female clothing in public; and where men visiting gay bars usually carried bail money with them."[43]

History

1940s–1960s: First discotheques

Disco was mostly developed from music that was popular on the dance floor in clubs that started playing records instead of having a live band. The first discotheques mostly played swing music. Later on, uptempo rhythm and blues became popular in American clubs and northern soul and glam rock records in the UK. In the early 1940s, nightclubs in Paris resorted to playing jazz records during the Nazi occupation.

Régine Zylberberg claimed to have started the first discotheque and to have been the first club DJ in 1953 in the "Whisky à Go-Go" in Paris. She installed a dance floor with colored lights and two turntables so she could play records without having a gap in the music.[44] In October 1959, the owner of the Scotch Club in Aachen, West Germany chose to install a record player for the opening night instead of hiring a live band. The patrons were unimpressed until a young reporter, who happened to be covering the opening of the club, impulsively took control of the record player and introduced the records that he chose to play. Klaus Quirini later claimed to thus have been the world's first nightclub DJ.[14]

1960s–1974: Precursors and early disco music

During the 1960s, discotheque dancing became a European trend that was enthusiastically picked up by the American press.[14] At this time, when the discotheque culture from Europe became popular in the United States, several music genres with danceable rhythms rose to popularity and evolved into different sub-genres: rhythm and blues (originated in the 1940s), soul (late 1950s and 1960s), funk (mid-1960s) and go-go (mid-1960s and 1970s; more than "disco", the word "go-go" originally indicated a music club). Musical genres, that were primarily performed by African-American musicians would influence much of early disco.

Also during the 1960s, the Motown record label developed its own approach, described as having "1) simply structured songs with sophisticated melodies and chord changes, 2) a relentless four-beat drum pattern, 3) a gospel use of background voices, vaguely derived from the style of the Impressions, 4) a regular and sophisticated use of both horns and strings, 5) lead singers who were half way between pop and gospel music, 6) a group of accompanying musicians who were among the most dextrous, knowledgeable, and brilliant in all of popular music (Motown bassists have long been the envy of white rock bassists) and 7) a trebly style of mixing that relied heavily on electronic limiting and equalizing (boosting the high range frequencies) to give the overall product a distinctive sound, particularly effective for broadcast over AM radio."[45] Motown had many hits with early disco elements by acts like the Supremes ("You Keep Me Hangin' On" in 1966), Stevie Wonder ("Superstition" in 1972), The Jackson 5, and Eddie Kendricks ("Keep on Truckin'" in 1973).

At the end of the 1960s, musicians, and audiences from the Black, Italian, and Latino communities adopted several traits from the hippie and psychedelia subcultures. They included using music venues with a loud, overwhelming sound, free-form dancing, trippy lighting, colorful costumes, and the use of hallucinogenic drugs.[46][47][48] In addition, the perceived positivity, lack of irony, and earnestness of the hippies informed proto-disco music like MFSB's album Love Is the Message.[46][49] Partly through the success of Jimi Hendrix, psychedelic elements that were popular in rock music of the late 1960s found their way into soul and early funk music and formed the subgenre psychedelic soul. Examples can be found in the music of the Chambers Brothers, George Clinton with his Parliament-Funkadelic collective, Sly and the Family Stone, and the productions of Norman Whitfield with The Temptations.

The long instrumental introductions and detailed orchestration found in psychedelic soul tracks by the Temptations are also considered as cinematic soul. In the early 1970s, Curtis Mayfield and Isaac Hayes scored hits with cinematic soul songs that were actually composed for movie soundtracks: "Superfly" (1972) and "Theme from Shaft" (1971). The latter is sometimes regarded as an early disco song.[50] From the mid-1960s to early 1970s, Philadelphia soul and New York soul developed as sub-genres that also had lavish percussion, lush string orchestra arrangements, and expensive record production processes. In the early 1970s, the Philly soul productions by Gamble and Huff evolved from the simpler arrangements of the late-1960s into a style featuring lush strings, thumping basslines, and sliding hi-hat rhythms. These elements would become typical for disco music and are found in several of the hits they produced in the early 1970s:

- "Love Train" by the O'Jays (with MFSB as the backup band) was released in 1972 and topped the Billboard Hot 100 in March 1973

- "The Love I Lost" by Harold Melvin & the Blue Notes (1973)

- "Now That We Found Love" by The O'Jays (1973), later a hit for Third World in 1978

- "TSOP (The Sound of Philadelphia)" by MFSB with vocals by The Three Degrees, a wordless song written as the theme for Soul Train and a #1 hit on the Billboard Hot 100 in 1974

Other early disco tracks that helped shape disco and became popular on the dance floors of (underground) discotheque clubs and parties include:

- "Soul Makossa" by Manu Dibango was first released in France in 1972; it was picked up by the underground disco scene in New York and subsequently got a proper release in the U.S., reaching #35 on the Hot 100 in 1973

- "The Night" by the Four Seasons was released in 1972, but was not immediately popular; it appealed to the Northern soul scene and became a hit in the UK in 1975[51]

- "Love's Theme" by the Love Unlimited Orchestra, conducted by Barry White, an instrumental song originally featured on Under the Influence of... Love Unlimited in July 1973 from which it was culled as a single in November of that year; subsequently, the conductor included it on his own debut album Rhapsody in White (1974) where the track reached number one on the Billboard Hot 100 early that year.

- "Jungle Fever" by The Chakachas was first released in Belgium in 1971 and later released in the U.S. in 1972, where it reached #8 on the Billboard Hot 100 that same year

- "Girl You Need a Change of Mind" by Eddie Kendricks was released in May 1972, on the album People ... Hold On

Early disco was dominated by record producers and labels such as Salsoul Records (Ken, Stanley, and Joseph Cayre), West End Records (Mel Cheren), Casablanca (Neil Bogart), and Prelude (Marvin Schlachter). The genre was also shaped by Tom Moulton, who wanted to extend the enjoyment of dance songs — thus creating the extended mix or "remix", going from a three-minute 45 rpm single to the much longer 12" record. Other influential DJs and remixers who helped to establish what became known as the "disco sound" included David Mancuso, Nicky Siano, Shep Pettibone, Larry Levan, Walter Gibbons, and Chicago-based Frankie Knuckles. Frankie Knuckles was not only an important disco DJ; he also helped to develop house music in the 1980s.

Disco hit the television airwaves as part of the music/dance variety show Soul Train in 1971 hosted by Don Cornelius, then Marty Angelo's Disco Step-by-Step Television Show in 1975, Steve Marcus's Disco Magic/Disco 77, Eddie Rivera's Soap Factory, and Merv Griffin's Dance Fever, hosted by Deney Terrio, who is credited with teaching actor John Travolta to dance for his role in the film Saturday Night Fever, as well as DANCE, based out of Columbia, South Carolina.

In 1974, New York City's WPIX-FM premiered the first disco radio show.[52]

Early disco culture in the United States

In the 1970s, the key counterculture of the 1960s, the hippie movement, was fading away. The economic prosperity of the previous decade had declined, and unemployment, inflation, and crime rates had soared. Political issues like the backlash from the Civil Rights Movement culminating in the form of race riots, the Vietnam War, the assassinations of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and John F. Kennedy, and the Watergate scandal, left many feeling disillusioned and hopeless. The start of the '70s was marked by a shift in the consciousness of the American people: the rise of the feminist movement, identity politics, gangs, etc. very much shaped this era. Disco music and disco dancing provided an escape from negative social and economic issues.[53] The non-partnered dance style of disco music allowed people of all races and sexual orientations to enjoy the dancefloor atmosphere.[54]

In Beautiful Things in Popular Culture, Simon Frith highlights the sociability of disco and its roots in 1960s counterculture. "The driving force of the New York underground dance scene in which disco was forged was not simply that city's complex ethnic and sexual culture but also a 1960s notion of community, pleasure and generosity that can only be described as hippie", he says. "The best disco music contained within it a remarkably powerful sense of collective euphoria."[55]

The birth of disco is often claimed to be found in the private dance parties held by New York City DJ David Mancuso's home that became known as The Loft, an invitation-only non-commercial underground club that inspired many others.[17] He organized the first major party in his Manhattan home on Valentine's Day 1970 with the name "Love Saves The Day". After some months the parties became weekly events and Mancuso continued to give regular parties into the 1990s.[56] Mancuso required that the music played had to be soulful, rhythmic, and impart words of hope, redemption, or pride.[43]

When Mancuso threw his first informal house parties, the gay community (which made up much of The Loft's attendee roster) was often harassed in the gay bars and dance clubs, with many gay men carrying bail money with them to gay bars. But at The Loft and many other early, private discotheques, they could dance together without fear of police action thanks to Mancuso's underground, yet legal, policies. Vince Aletti described it "like going to party, completely mixed, racially and sexually, where there wasn't any sense of someone being more important than anyone else," and Alex Rosner reiterated this saying "It was probably about sixty percent black and seventy percent gay...There was a mix of sexual orientation, there was a mix of races, mix of economic groups. A real mix, where the common denominator was music."[43]

Film critic Roger Ebert called the popular embrace of disco's exuberant dance moves an escape from "the general depression and drabness of the political and musical atmosphere of the late seventies."[57] Pauline Kael, writing about the disco-themed film Saturday Night Fever, said the film and disco itself touched on "something deeply romantic, the need to move, to dance, and the need to be who you'd like to be. Nirvana is the dance; when the music stops, you return to being ordinary."[58]

Early disco culture in the United Kingdom

In the late 1960s, uptempo soul with heavy beats and some associated dance styles and fashion were picked up in the British mod scene and formed the northern soul movement. Originating at venues such as the Twisted Wheel in Manchester, it quickly spread to other UK dancehalls and nightclubs like the Chateau Impney (Droitwich), Catacombs (Wolverhampton), the Highland Rooms at Blackpool Mecca, Golden Torch (Stoke-on-Trent), and Wigan Casino. As the favoured beat became more uptempo and frantic in the early 1970s, northern soul dancing became more athletic, somewhat resembling the later dance styles of disco and break dancing. Featuring spins, flips, karate kicks, and backdrops, club dancing styles were often inspired by the stage performances of touring American soul acts such as Little Anthony & the Imperials and Jackie Wilson.

In 1974, there were an estimated 25,000 mobile discos and 40,000 professional disc jockeys in the United Kingdom. Mobile discos were hired deejays that brought their own equipment to provide music for special events. Glam rock tracks were popular, with, for example, Gary Glitter's 1972 single "Rock and Roll Part 2" becoming popular on UK dance floors while it did not get much radio airplay.[59]

1974–1977: Rise to mainstream

From 1974 to 1977, disco music increased in popularity as many disco songs topped the charts. The Hues Corporation's "Rock the Boat" (1974), a US number-one single and million-seller, was one of the early disco songs to reach number one. The same year saw the release of "Kung Fu Fighting", performed by Carl Douglas and produced by Biddu, which reached number one in both the UK and US, and became the best-selling single of the year[60] and one of the best-selling singles of all time with 11 million records sold worldwide,[61][62] helping to popularize disco to a great extent.[61] Another notable disco success that year was George McCrae's "Rock Your Baby":[63] it became the United Kingdom's first number one disco single.[64][63]

In the northwestern sections of the United Kingdom, the northern soul explosion, which started in the late 1960s and peaked in 1974, made the region receptive to disco, which the region's disc jockeys were bringing back from New York City. The shift by some DJs to the newer sounds coming from the U.S.A. resulted in a split in the scene, whereby some abandoned the 1960s soul and pushed a modern soul sound which tended to be more closely aligned with disco than soul.

In 1975, Gloria Gaynor released her first side-long vinyl album, which included a remake of the Jackson 5's "Never Can Say Goodbye" (which, in fact, is also the album title) and two other songs, "Honey Bee" and her disco version of "Reach Out (I'll Be There)". The album first topped the Billboard disco/dance charts in November 1974. Later in 1978, Gaynor's number-one disco song was "I Will Survive", which was seen as a symbol of female strength and a gay anthem,[65] like her further disco hit, a 1983 remake of "I Am What I Am". In 1979 she released "Let Me Know (I Have a Right)", a single which gained popularity in the civil rights movements. Also in 1975, Vincent Montana Jr.'s Salsoul Orchestra contributed with their Latin-flavored orchestral dance song "Salsoul Hustle", reaching number four on the Billboard Dance Chart; their 1976 hits were "Tangerine" and "Nice 'n' Naasty", the first being a cover of a 1941 song.[citation needed]

Songs such as Van McCoy's 1975 "The Hustle" and the humorous Joe Tex 1977 "Ain't Gonna Bump No More (With No Big Fat Woman)" gave names to the popular disco dances "the Bump" and "the Hustle". Other notable early successful disco songs include Barry White's "You're the First, the Last, My Everything" (1974); Labelle's "Lady Marmalade" (1974)'; Disco-Tex and the Sex-O-Lettes' "Get Dancin'" (1974); Silver Convention's "Fly, Robin, Fly" (1975) and "Get Up and Boogie" (1976)'; Vicki Sue Robinson's "Turn the Beat Around" (1976); and "More, More, More" (1976) by Andrea True (a former pornographic actress during the Golden Age of Porn, an era largely contemporaneous with the height of disco).

Formed by Harry Wayne Casey (a.k.a. "KC") and Richard Finch, Miami's KC and the Sunshine Band had a string of disco-definitive top-five singles between 1975 and 1977, including "Get Down Tonight", "That's the Way (I Like It)", "(Shake, Shake, Shake) Shake Your Booty", "I'm Your Boogie Man", "Boogie Shoes", and "Keep It Comin' Love". In this period, rock bands like the English Electric Light Orchestra featured in their songs a violin sound that became a staple of disco music, as in the 1975 hit "Evil Woman", although the genre was correctly described as orchestral rock.

Other disco producers such as Tom Moulton took ideas and techniques from dub music (which came with the increased Jamaican migration to New York City in the 1970s) to provide alternatives to the "four on the floor" style that dominated. DJ Larry Levan utilized styles from dub and jazz and remixing techniques to create early versions of house music that sparked the genre.[66]

Motown turning disco

Norman Whitfield was an influential producer and songwriter at Motown records, renowned for creating innovative "psychedelic soul" songs with many hits for Marvin Gaye, the Velvelettes, the Temptations, and Gladys Knight & The Pips. From around the production of the Temptations album Cloud Nine in 1968, he incorporated some psychedelic influences and started to produce longer, dance-friendly tracks, with more room for elaborate rhythmic instrumental parts. An example of such a long psychedelic soul track is "Papa Was a Rollin' Stone", which appeared as a single edit of almost seven minutes and an approximately 12-minute-long 12" version in 1972. By the early 70s, many of Whitfield's productions evolved more and more towards funk and disco, as heard on albums by the Undisputed Truth and the 1973 album G.I.T.: Get It Together by The Jackson 5. The Undisputed Truth, a Motown recording act assembled by Whitfield to experiment with his psychedelic soul production techniques, found success with their 1971 song "Smiling Faces Sometimes". Their disco single "You + Me = Love" (number 43) was produced by Whitfield and made number 2 on the US dance chart in 1976.

In 1975, Whitfield left Motown and founded his own label Whitfield records, on which also "You + Me = Love" was released. Whitfield produced some more disco hits, including "Car Wash" (1976) by Rose Royce from the album soundtrack to the 1976 film Car Wash. In 1977, singer, songwriter, and producer Willie Hutch, who had been signed to Motown since 1970, now signed with Whitfield's new label, and scored a successful disco single with his song "In and Out" in 1982.

Other Motown artists turned to disco as well. Diana Ross embraced the disco sound with her successful 1976 outing "Love Hangover" from her self-titled album. Her 1980 dance classics "Upside Down" and "I'm Coming Out" were written and produced by Nile Rodgers and Bernard Edwards of the group Chic. The Supremes, the group that made Ross famous, scored a handful of hits in the disco clubs without her, most notably 1976's "I'm Gonna Let My Heart Do the Walking" and, their last charted single before disbanding, 1977's "You're My Driving Wheel".

At the request of Motown that he produce songs in the disco genre, Marvin Gaye released "Got to Give It Up" in 1978, despite his dislike of disco. He vowed not to record any songs in the genre and actually wrote the song as a parody. However, several of Gaye's songs have disco elements, including "I Want You" (1975). Stevie Wonder released the disco single "Sir Duke" in 1977 as a tribute to Duke Ellington, the influential jazz legend who had died in 1974. Smokey Robinson left the Motown group the Miracles for a solo career in 1972 and released his third solo album A Quiet Storm in 1975, which spawned and lent its name to the "Quiet Storm" musical programming format and subgenre of R&B. It contained the disco single "Baby That's Backatcha". Other Motown artists who scored disco hits were Robinson's former group, the Miracles, with "Love Machine" (1975), Eddie Kendricks with "Keep On Truckin'" (1973), the Originals with "Down to Love Town" (1976), and Thelma Houston with her cover of the Harold Melvin and the Blue Notes song "Don't Leave Me This Way" (1976). The label continued to release successful songs into the 1980s with Rick James's "Super Freak" (1981), and the Commodores' "Lady (You Bring Me Up)" (1981).

Several of Motown's solo artists who left the label went on to have successful disco songs. Mary Wells, Motown's first female superstar with her signature song "My Guy" (written by Smokey Robinson), abruptly left the label in 1964. She briefly reappeared on the charts with the disco song "Gigolo" in 1980. Jimmy Ruffin, the elder brother of the Temptations lead singer David Ruffin, was also signed to Motown and released his most successful and well-known song "What Becomes of the Brokenhearted" as a single in 1966. Ruffin eventually left the record label in the mid-1970s, but saw success with the 1980 disco song "Hold On (To My Love)", which was written and produced by Robin Gibb of the Bee Gees, for his album Sunrise. Edwin Starr, known for his Motown protest song "War" (1970), reentered the charts in 1979 with a pair of disco songs, "Contact" and "H.A.P.P.Y. Radio". Kiki Dee became the first white British singer to sign with Motown in the US, and released one album, Great Expectations (1970), and two singles "The Day Will Come Between Sunday and Monday" (1970) and "Love Makes the World Go Round" (1971), the latter giving her first-ever chart entry (number 87 on the US Chart). She soon left the company and signed with Elton John's The Rocket Record Company, and in 1976 had her biggest and best-known single, "Don't Go Breaking My Heart", a disco duet with John. The song was intended as an affectionate disco-style pastiche of the Motown sound, in particular the various duets recorded by Marvin Gaye with Tammi Terrell and Kim Weston.

Many Motown groups who had left the record label charted with disco songs. The Jackson 5, one of Motown's premier acts in the early 1970s, left the record company in 1975 (Jermaine Jackson, however, remained with the label) after successful songs like "I Want You Back" (1969) and "ABC" (1970), and even the disco song "Dancing Machine" (1974). Renamed as 'the Jacksons' (as Motown owned the name 'the Jackson 5'), they went on to find success with disco songs like "Blame It on the Boogie" (1978), "Shake Your Body (Down to the Ground)" (1979), and "Can You Feel It?" (1981) on the Epic label.

The Isley Brothers, whose short tenure at the company had produced the song "This Old Heart of Mine (Is Weak for You)" in 1966, went on release successful disco songs like "It's a Disco Night (Rock Don't Stop)" (1979). Gladys Knight and the Pips, who recorded the most successful version of "I Heard It Through the Grapevine" (1967) before Marvin Gaye, scored commercially successful singles such as "Baby, Don't Change Your Mind" (1977) and "Bourgie, Bourgie" (1980) in the disco era. The Detroit Spinners were also signed to the Motown label and saw success with the Stevie Wonder-produced song "It's a Shame" in 1970. They left soon after, on the advice of fellow Detroit native Aretha Franklin, to Atlantic Records, and there had disco songs like "The Rubberband Man" (1976). In 1979, they released a successful cover of Elton John's "Are You Ready for Love", as well as a medley of the Four Seasons' song "Working My Way Back to You" and Michael Zager's "Forgive Me, Girl". The Four Seasons themselves were briefly signed to Motown's MoWest label, a short-lived subsidiary for R&B and soul artists based on the West Coast, and there the group produced one album, Chameleon (1972) – to little commercial success in the US. However, one single, "The Night", was released in Britain in 1975, and thanks to popularity from the Northern Soul circuit, reached number seven on the UK Singles Chart. The Four Seasons left Motown in 1974 and went on to have a disco hit with their song "December, 1963 (Oh, What a Night)" (1975) for Warner Curb Records.

Eurodisco

By far the most successful Euro disco act was ABBA (1972–1982). This Swedish quartet, which sang primarily in English, found success with singles such as "Waterloo" (1974), "Fernando" (1976), "Take a Chance on Me" (1978), "Gimme! Gimme! Gimme! (A Man After Midnight)" (1979), and their signature smash hit "Dancing Queen" (1976).

In the 1970s Munich, West Germany, music producers Giorgio Moroder and Pete Bellotte made a decisive contribution to disco music with a string of hits for Donna Summer, which became known as the "Munich Sound".[68] In 1975, Summer suggested the lyric "Love to Love You Baby" to Moroder and Bellotte, who turned the lyric into a full disco song. The final product, which contained the vocalizations of a series of simulated orgasms, initially was not intended for release, but when Moroder played it in the clubs it caused a sensation and he released it. The song became an international hit, reaching the charts in many European countries and the US (No. 2). It has been described as the arrival of the expression of raw female sexual desire in pop music. A nearly 17-minute 12-inch single was released. The 12" single became and remains a standard in discos today.[69][70] In 1976 Donna Summer's version of "Could It Be Magic" brought disco further into the mainstream. In 1977 Summer, Moroder and Bellotte further released "I Feel Love", as the B-side of "Can't We Just Sit Down (And Talk It Over)", which revolutionized dance music with its mostly electronic production and was a massive worldwide success, spawning the Hi-NRG subgenre.[69] Giorgio Moroder was described by AllMusic as "one of the principal architects of the disco sound".[71] Another successful disco music project by Moroder at that time was Munich Machine (1976–1980).

Boney M. (1974–1986) was a West German Euro disco group of four West Indian singers and dancers masterminded by record producer Frank Farian. Boney M. charted worldwide with such songs as "Daddy Cool" (1976) "Ma Baker" (1977) and "Rivers Of Babylon" (1978). Another successful West German Euro disco recording act was Silver Convention (1974–1979). The German group Kraftwerk also had an influence on Euro disco.

In France, Dalida released "J'attendrai" ("I Will Wait") in 1975, which also became successful in Canada, Europe, and Japan. Dalida successfully adjusted herself to disco and released at least a dozen of songs that charted in the top 10 in Europe. Claude François, who re-invented himself as the "king of French disco", released "La plus belle chose du monde", a French version of the Bee Gees song "Massachusetts", which became successful in Canada and Europe and "Alexandrie Alexandra" was posthumously released on the day of his burial and became a worldwide success. Cerrone's early songs, "Love in C Minor" (1976), "Supernature" (1977), and "Give Me Love" (1978) were successful in the US and Europe. Another Euro disco act was the French diva Amanda Lear, where Euro disco sound is most heard in "Enigma (Give a Bit of Mmh to Me)" (1978). French producer Alec Costandinos assembled the Euro disco group Love and Kisses (1977–1982).

In Italy Raffaella Carrà was the most successful Euro disco act, alongside La Bionda, Hermanas Goggi and Oliver Onions. Her greatest international single was "Tanti Auguri" ("Best Wishes"), which has become a popular song with gay audiences. The song is also known under its Spanish title "Para hacer bien el amor hay que venir al sur" (which refers to Southern Europe, since the song was recorded and taped in Spain). The Estonian version of the song "Jätke võtmed väljapoole" was performed by Anne Veski. "A far l'amore comincia tu" ("To make love, your move first") was another success for her internationally, known in Spanish as "En el amor todo es empezar", in German as "Liebelei", in French as "Puisque tu l'aimes dis le lui", and in English as "Do It, Do It Again". It was her only entry to the UK Singles Chart, reaching number 9, where she remains a one-hit wonder.[72] In 1977, she recorded another successful single, "Fiesta" ("The Party" in English) originally in Spanish, but then recorded it in French and Italian after the song hit the charts. "A far l'amore comincia tu" has also been covered in Turkish by a Turkish popstar Ajda Pekkan as "Sakın Ha" in 1977.

Recently, Carrà has gained new attention for her appearance as the female dancing soloist in a 1974 TV performance of the experimental gibberish song "Prisencolinensinainciusol" (1973) by Adriano Celentano.[73] A remixed video featuring her dancing went viral on the internet in 2008.[74][citation needed] In 2008 a video of a performance of her only successful UK single, "Do It, Do It Again", was featured in the Doctor Who episode "Midnight". Rafaella Carrà worked with Bob Sinclar on the new single "Far l'Amore" which was released on YouTube on March 17, 2011. The song charted in different European countries.[75] Another prominent European disco act was the pop group Luv' from the Netherlands.

Euro disco continued evolving within the broad mainstream pop music scene, even when disco's popularity sharply declined in the United States, abandoned by major U.S. record labels and producers.[76] Through the influence of Italo disco, it also played a role in the evolution of early house music in the early 1980s and later forms of electronic dance music, including early '90s Eurodance.

1977–1979: Pop preeminence

In December 1977, the film Saturday Night Fever was released. It was a huge success and its soundtrack became one of the best-selling albums of all time. The idea for the film was sparked by a 1976 New York magazine[77] article titled "Tribal Rites of the New Saturday Night" which supposedly chronicled the disco culture in mid-1970s New York City, but was later revealed to have been fabricated.[78] Some critics said the film "mainstreamed" disco, making it more acceptable to heterosexual white males.[79]

The Bee Gees used Barry Gibb's falsetto to garner hits such as "You Should Be Dancing", "Stayin' Alive", "Night Fever", "More Than A Woman", and "Love You Inside Out". Andy Gibb, a younger brother to the Bee Gees, followed with similarly styled solo singles such as "I Just Want to Be Your Everything", "(Love Is) Thicker Than Water", and "Shadow Dancing".

In 1978, Donna Summer's multi-million-selling vinyl single disco version of "MacArthur Park" was number one on the Billboard Hot 100 chart for three weeks and was nominated for the Grammy Award for Best Female Pop Vocal Performance. The recording, which was included as part of the "MacArthur Park Suite" on her double live album Live and More, was eight minutes and 40 seconds long on the album. The shorter seven-inch vinyl single version of MacArthur Park was Summer's first single to reach number one on the Hot 100; it does not include the balladic second movement of the song, however. A 2013 remix of "MacArthur Park" by Summer topped the Billboard Dance Charts marking five consecutive decades with a number-one song on the charts.[80] From mid-1978 to late 1979, Summer continued to release singles such as "Last Dance", "Heaven Knows" (with Brooklyn Dreams), "Hot Stuff", "Bad Girls", "Dim All the Lights" and "On the Radio", all very successful songs, landing in the top five or better, on the Billboard pop charts.

The band Chic was formed mainly by guitarist Nile Rodgers—a self-described "street hippie" from late 1960s New York—and bassist Bernard Edwards. Their popular 1978 single, "Le Freak", is regarded as an iconic song of the genre. Other successful songs by Chic include the often-sampled "Good Times" (1979), "I Want Your Love" (1979), and "Everybody Dance" (1979). The group regarded themselves as the disco movement's rock band that made good on the hippie movement's ideals of peace, love, and freedom. Every song they wrote was written with an eye toward giving it "deep hidden meaning" or D.H.M.[81]

Sylvester, a flamboyant and openly gay singer famous for his soaring falsetto voice, scored his biggest disco hit in late 1978 with "You Make Me Feel (Mighty Real)". His singing style was said to have influenced the singer Prince. At that time, disco was one of the forms of music most open to gay performers.[82]

The Village People were a singing/dancing group created by Jacques Morali and Henri Belolo to target disco's gay audience. They were known for their onstage costumes of typically male-associated jobs and ethnic minorities and achieved mainstream success with their 1978 hit song "Macho Man". Other songs include "Y.M.C.A." (1979) and "In the Navy" (1979).

Also noteworthy are The Trammps' "Disco Inferno" (1976), (1978, reissue due to the popularity gained from the Saturday Night Fever soundtrack), Heatwave's "Boogie Nights" (1977), Evelyn "Champagne" King's "Shame" (1977), A Taste of Honey's "Boogie Oogie Oogie" (1978), Cheryl Lynn's "Got to Be Real" (1978), Alicia Bridges's "I Love the Nightlife" (1978), Patrick Hernandez's "Born to Be Alive" (1978), Earth, Wind & Fire's "September" (1978) and "Boogie Wonderland" (1979), Peaches & Herb's "Shake Your Groove Thing" (1978), Sister Sledge's "We Are Family" and "He's the Greatest Dancer" (both 1979), McFadden and Whitehead's "Ain't No Stoppin' Us Now" (1979), Anita Ward's "Ring My Bell" (1979), Kool & the Gang's "Ladies' Night" (1979) and "Celebration" (1980), The Whispers's "And the Beat Goes On" (1979), Stephanie Mills's "What Cha Gonna Do with My Lovin'" (1979), Lipps Inc.'s "Funkytown" (1980), The Brothers Johnson's "Stomp!" (1980), George Benson's "Give Me the Night" (1980), Donna Summer's "Sunset People" (1980), and Walter Murphy's various attempts to bring classical music to the mainstream, most notably the disco song "A Fifth of Beethoven" (1976), which was inspired by Beethoven's fifth symphony.

At the height of its popularity, many non-disco artists recorded songs with disco elements, such as Rod Stewart with his "Da Ya Think I'm Sexy?" in 1979.[83] Even mainstream rock artists adopted elements of disco. Progressive rock group Pink Floyd used disco-like drums and guitar in their song "Another Brick in the Wall, Part 2" (1979),[84] which became their only number-one single in both the US and UK. The Eagles referenced disco with "One of These Nights" (1975)[85] and "Disco Strangler" (1979), Paul McCartney & Wings with "Silly Love Songs" (1976) and "Goodnight Tonight" (1979), Queen with "Another One Bites the Dust" (1980), the Rolling Stones with "Miss You" (1978) and "Emotional Rescue" (1980), Stephen Stills with his album Thoroughfare Gap (1978), Electric Light Orchestra with "Shine a Little Love" and "Last Train to London" (both 1979), Chicago with "Street Player" (1979), the Kinks with "(Wish I Could Fly Like) Superman" (1979), the Grateful Dead with "Shakedown Street", The Who with "Eminence Front" (1982), and the J. Geils Band with "Come Back" (1980). Even hard rock group KISS jumped in with "I Was Made for Lovin' You" (1979),[86] and Ringo Starr's album Ringo the 4th (1978) features a strong disco influence.

The disco sound was also adopted by artists from other genres, including the 1979 U.S. number one hit "No More Tears (Enough Is Enough)" by easy listening singer Barbra Streisand in a duet with Donna Summer. In country music, in an attempt to appeal to the more mainstream market, artists began to add pop/disco influences to their music. Dolly Parton launched a successful crossover onto the pop/dance charts, with her albums Heartbreaker and Great Balls of Fire containing songs with a disco flair. In particular, a disco remix of the track "Baby I'm Burnin'" peaked at number 15 on the Billboard Dance Club Songs chart; ultimately becoming one of the years biggest club hits.[87] Additionally, Connie Smith covered Andy Gibb's "I Just Want to Be Your Everything" in 1977, Bill Anderson recorded "Double S" in 1978, and Ronnie Milsap released "Get It Up" and covered blues singer Tommy Tucker's song "Hi-Heel Sneakers" in 1979.

Pre-existing non-disco songs, standards, and TV themes were frequently "disco-ized" in the 1970s, such as the I Love Lucy theme (recorded as "Disco Lucy" by the Wilton Place Street Band), "Aquarela do Brasil" (recorded as "Brazil" by The Ritchie Family), and "Baby Face" (recorded by the Wing and a Prayer Fife and Drum Corps). The rich orchestral accompaniment that became identified with the disco era conjured up the memories of the big band era—which brought out several artists that recorded and disco-ized some big band arrangements, including Perry Como, who re-recorded his 1945 song "Temptation", in 1975, as well as Ethel Merman, who released an album of disco songs entitled The Ethel Merman Disco Album in 1979.

Myron Floren, second-in-command on The Lawrence Welk Show, released a recording of the "Clarinet Polka" entitled "Disco Accordion." Similarly, Bobby Vinton adapted "The Pennsylvania Polka" into a song named "Disco Polka". Easy listening icon Percy Faith, in one of his last recordings, released an album entitled Disco Party (1975) and recorded a disco version of his "Theme from A Summer Place" in 1976. Even classical music was adapted for disco, notably Walter Murphy's "A Fifth of Beethoven" (1976, based on the first movement of Beethoven's 5th Symphony) and "Flight 76" (1976, based on Rimsky-Korsakov's "Flight of the Bumblebee"), and Louis Clark's Hooked On Classics series of albums and singles.

Many original television theme songs of the era also showed a strong disco influence, such as S.W.A.T. (1975), Wonder Woman (1975), Charlie's Angels (1976), NBC Saturday Night At The Movies (1976), The Love Boat (1977), The Donahue Show (1977), CHiPs (1977), The Professionals (1977), Dallas (1978), NBC Sports broadcasts (1978), Kojak (1977), and The Hollywood Squares (1979).

Disco jingles also made their way into many TV commercials, including Purina's 1979 "Good Mews" cat food commercial[88] and an "IC Light" commercial by Pittsburgh's Iron City Brewing Company.

Parodies

Several parodies of the disco style were created. Rick Dees, at the time a radio DJ in Memphis, Tennessee, recorded "Disco Duck" (1976) and "Dis-Gorilla" (1977); Frank Zappa parodied the lifestyles of disco dancers in "Disco Boy" on his 1976 Zoot Allures album and in "Dancin' Fool" on his 1979 Sheik Yerbouti album. "Weird Al" Yankovic's eponymous 1983 debut album includes a disco song called "Gotta Boogie", an extended pun on the similarity of the disco move to the American slang word "booger". Comedian Bill Cosby devoted his entire 1977 album Disco Bill to disco parodies. In 1980, Mad Magazine released a flexi-disc titled Mad Disco featuring six full-length parodies of the genre. Rock and roll songs critical of disco included Bob Seger's "Old Time Rock and Roll" and, especially, The Who's "Sister Disco" (both 1978)—although The Who's "Eminence Front" (four years later) had a disco feel.

1979–1981: Controversy and decline in popularity

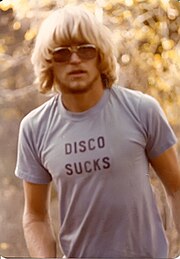

By the end of the 1970s, anti-disco sentiment developed among rock music fans and musicians, particularly in the United States.[89][90] Disco was criticized as mindless, consumerist, overproduced and escapist.[91] The slogans "Disco sucks" and "Death to disco"[89] became common. Rock artists such as Rod Stewart and David Bowie who added disco elements to their music were accused of selling out.[92][93]

The punk subculture in the United States and the United Kingdom was often hostile to disco,[89] although, in the UK, many early Sex Pistols fans such as the Bromley Contingent and Jordan liked disco, often congregating at nightclubs such as Louise's in Soho and the Sombrero in Kensington. The track "Love Hangover" by Diana Ross, the house anthem at the former, was cited as a particular favourite by many early UK punks.[94] The film The Great Rock 'n' Roll Swindle and its soundtrack album contained a disco medley of Sex Pistols songs, entitled Black Arabs and credited to a group of the same name.

However, Jello Biafra of the Dead Kennedys, in the song "Saturday Night Holocaust", likened disco to the cabaret culture of Weimar-era Germany for its apathy towards government policies and its escapism. Mark Mothersbaugh of Devo said that disco was "like a beautiful woman with a great body and no brains", and a product of political apathy of that era.[95] New Jersey rock critic Jim Testa wrote "Put a Bullet Through the Jukebox", a vitriolic screed attacking disco that was considered a punk call to arms.[96] Steve Hillage, shortly prior to his transformation from a progressive rock musician into an electronic artist at the end of the 1970s with the inspiration of disco, disappointed his rockist fans by admitting his love for disco, with Hillage recalling "it's like I'd killed their pet cat."[97]

Anti-disco sentiment was expressed in some television shows and films. A recurring theme on the show WKRP in Cincinnati was a hostile attitude towards disco music. In one scene of the 1980 comedy film Airplane!, a wayward airplane slices a radio tower with its wing, knocking out an all-disco radio station.[98] July 12, 1979, became known as "the day disco died" because of the Disco Demolition Night, an anti-disco demonstration in a baseball double-header at Comiskey Park in Chicago.[99] Rock station DJs Steve Dahl and Garry Meier, along with Michael Veeck, son of Chicago White Sox owner Bill Veeck, staged the promotional event for disgruntled rock fans between the games of a White Sox doubleheader which involved exploding disco records in centerfield. As the second game was about to begin, the raucous crowd stormed onto the field and proceeded to set fires and tear out seats and pieces of turf. The Chicago Police Department made numerous arrests, and the extensive damage to the field forced the White Sox to forfeit the second game to the Detroit Tigers, who had won the first game.

Disco's decline in popularity after Disco Demolition Night was rapid. On July 12, 1979, the top six records on the U.S. music charts were disco songs.[100] By September 22, there were no disco songs in the US Top 10 chart, with the exception of Herb Alpert's instrumental "Rise", a smooth jazz composition with some disco overtones.[100] Some in the media, in celebratory tones, declared disco "dead" and rock revived.[100] Karen Mixon Cook, the first female disco DJ, stated that people still pause every July 12 for a moment of silence in honor of disco. Dahl stated in a 2004 interview that disco was "probably on its way out [at the time]. But I think it [Disco Demolition Night] hastened its demise".[101]

Impact on the music industry

The anti-disco movement, combined with other societal and radio industry factors, changed the face of pop radio in the years following Disco Demolition Night. Starting in the 1980s, country music began a slow rise on the pop chart. Emblematic of country music's rise to mainstream popularity was the commercially successful 1980 movie Urban Cowboy. The continued popularity of power pop and the revival of oldies in the late 1970s was also related to disco's decline; the 1978 film Grease was emblematic of this trend. Coincidentally, the star of both films was John Travolta, who in 1977 had starred in Saturday Night Fever, which remains one of the most iconic disco films of the era.

During this period of decline in disco's popularity, several record companies folded were reorganized, or were sold. In 1979, MCA Records purchased ABC Records, absorbed some of its artists and then shut the label down. Midsong International Records ceased operations in 1980. RSO Records founder Robert Stigwood left the label in 1981 and TK Records closed in the same year. Salsoul Records continues to exist in the 2000s, but primarily is used as a reissue brand.[102] Casablanca Records had been releasing fewer records in the 1980s, and was shut down in 1986 by parent company PolyGram.

Many groups that were popular during the disco period subsequently struggled to maintain their success—even ones who tried to adapt to evolving musical tastes. The Bee Gees, for instance, had only one top-10 entry (1989's "One") and three more top-40 songs (despite completely abandoning disco in their 1980s and 1990s songs), even though numerous songs they wrote and had other artists perform were successful. Of the handful of groups not taken down by disco's fall from favor, Kool and the Gang, Donna Summer, the Jacksons, and Gloria Gaynor in particular—stand out. In spite of having helped define the disco sound early on,[103] they continued to make popular and danceable, if more refined, songs for yet another generation of music fans in the 1980s and beyond. Earth, Wind & Fire also survived the anti-disco trend and continued to produce successful singles at roughly the same pace for several more years, in addition to an even longer string of R&B chart hits that lasted into the 1990s.

Six months prior to Disco Demolition Night (in December 1978), popular progressive rock radio station WDAI (WLS-FM) had suddenly switched to an all-disco format, disenfranchising thousands of Chicago rock fans and leaving Dahl unemployed. WDAI, who survived the change of public sentiment and still had good ratings at this point, continued to play disco until it flipped to a short-lived hybrid Top 40/rock format in May 1980. Another disco outlet that competed against WDAI at the time, WGCI-FM, would later incorporate R&B and pop songs into the format, eventually evolving into an urban contemporary outlet that it continues with today. The latter also helped bring the Chicago house genre to the airwaves.[citation needed]

Factors contributing to disco's decline

Factors that have been cited as leading to the decline of disco in the United States include economic and political changes at the end of the 1970s, as well as burnout from the hedonistic lifestyles led by participants.[104] In the years since Disco Demolition Night, some social critics have described the "Disco sucks" movement as implicitly macho and bigoted, and an attack on non-white and non-heterosexual cultures.[89][93][99] It was also interpreted being part of a wider cultural "backlash", the move towards conservatism,[105] that also made its way into US politics with the election of conservative president Ronald Reagan in 1980, which also led to Republican control of the United States Senate for the first time since 1954, plus the subsequent rise of the Religious Right around the same time.

In January 1979, rock critic Robert Christgau argued that homophobia, and most likely racism, were reasons behind the movement,[92] a conclusion seconded by John Rockwell. Craig Werner wrote: "The Anti-disco movement represented an unholy alliance of funkateers and feminists, progressives, and puritans, rockers and reactionaries. Nonetheless, the attacks on disco gave respectable voice to the ugliest kinds of unacknowledged racism, sexism and homophobia."[106] Legs McNeil, founder of the fanzine Punk, was quoted in an interview as saying, "the hippies always wanted to be black. We were going, 'fuck the blues, fuck the black experience.'" He also said that disco was the result of an "unholy" union between homosexuals and blacks.[107]

Steve Dahl, who had spearheaded Disco Demolition Night, denied any racist or homophobic undertones to the promotion, saying, "It's really easy to look at it historically, from this perspective, and attach all those things to it. But we weren't thinking like that."[93] It has been noted that British punk rock critics of disco were very supportive of the pro-black/anti-racist reggae genre as well as the more pro-gay new romantics movement.[89] Christgau and Jim Testa have said that there were legitimate artistic reasons for being critical of disco.[92][96]

In 1979, the music industry in the United States underwent its worst slump in decades, and disco, despite its mass popularity, was blamed. The producer-oriented sound was having difficulty mixing well with the industry's artist-oriented marketing system.[108] Harold Childs, senior vice president at A&M Records, reportedly told the Los Angeles Times that "radio is really desperate for rock product" and "they're all looking for some white rock-n-roll".[99] Gloria Gaynor argued that the music industry supported the destruction of disco because rock music producers were losing money and rock musicians were losing the spotlight.[109]

1981–1989: Aftermath

Birth of electronic dance music

Disco was instrumental in the development of electronic dance music genres like house, techno, and eurodance. The Eurodisco song I Feel Love, produced by Giorgio Moroder for Donna Summer in 1976, has been described as a milestone and blueprint for electronic dance music because it was the first to combine repetitive synthesizer loops with a continuous four-on-the-floor bass drum and an off-beat hi-hat, which would become a main feature of techno and house ten years later.[68][69][110]

During the first years of the 1980s, the traditional disco sound characterized by complex arrangements performed by large ensembles of studio session musicians (including a horn section and an orchestral string section) began to be phased out, and faster tempos and synthesized effects, accompanied by guitar and simplified backgrounds, moved dance music toward electronic and pop genres, starting with hi-NRG. Despite its decline in popularity, so-called club music and European-style disco remained relatively successful in the early-to-mid 1980s with songs like Aneka's "Japanese Boy", Laura Branigan's "Self Control", and Baltimora's "Tarzan Boy". However, a revival of the traditional-style disco called nu-disco has been popular since the 1990s.

House music displayed a strong disco influence, which is why house music, regarding its enormous success in shaping electronic dance music and contemporary club culture, is often described being "disco's revenge."[111] Early house music was generally dance-based music characterized by repetitive four-on-the-floor beats, rhythms mainly provided by drum machines,[112] off-beat hi-hat cymbals, and synthesized basslines. While house displayed several characteristics similar to disco music, it was more electronic and minimalist,[112] and the repetitive rhythm of house was more important than the song itself. As well, house did not use the lush string sections that were a key part of the disco sound.

Legacy

DJ culture

The rising popularity of disco came in tandem with developments in the role of the DJ. DJing developed from the use of multiple record turntables and DJ mixers to create a continuous, seamless mix of songs, with one song transitioning to another with no break in the music to interrupt the dancing. The resulting DJ mix differed from previous forms of dance music in the 1960s, which were oriented towards live performances by musicians. It, in turn, affected the arrangement of dance music, since songs in the disco era typically contained beginnings and endings marked by a simple beat or riff that could be easily used to transition to a new song. The development of DJing was also influenced by new turntablism techniques, such as beatmatching and scratching, a process facilitated by the introduction of new turntable technologies such as the Technics SL-1200 MK 2, first sold in 1978, which had a precise variable pitch control and a direct drive motor. DJs were often avid record collectors, who would hunt through used record stores for obscure soul records and vintage funk recordings. DJs helped to introduce rare records and new artists to club audiences.

In the 1970s, individual DJs became more prominent, and some DJs, such as Larry Levan, the resident at Paradise Garage, Jim Burgess, Tee Scott, and Francis Grasso became famous in the disco scene. Levan, for example, developed a cult following among clubgoers, who referred to his DJ sets as "Saturday Mass". Some DJs would use reel-to-reel tape recorders to make remixes and tape edits of songs. Some DJs who were making remixes made the transition from the DJ booth to becoming a record producer, notably Burgess. Scott developed several innovations. He was the first disco DJ to use three turntables as sound sources, the first to simultaneously play two beat-matched records, the first to use electronic effects units in his mixes, and he was an innovator in mixing dialogue in from well-known movies, typically over a percussion break. These mixing techniques were also applied to radio DJs, such as Ted Currier of WKTU and WBLS. Grasso is particularly notable for taking the DJ "profession out of servitude and [making] the DJ the musical head chef."[113] Once he entered the scene, the DJ was no longer responsible for waiting on the crowd hand and foot, meeting their every song request. Instead, with increased agency and visibility, the DJ was now able to use their own technical and creative skills to whip up a nightly special of innovative mixes, refining their personal sound and aesthetic, and building their own reputation.[114]

Post-disco

The post-disco sound and genres associated with it originated in the 1970s and early 1980s with R&B and post-punk musicians focusing on a more electronic and experimental side of disco, spawning boogie, Italo disco, and alternative dance. Drawing from a diverse range of non-disco influences and techniques, such as the "one-man band" style of Kashif and Stevie Wonder and alternative approaches of Parliament-Funkadelic, it was driven by synthesizers, keyboards, and drum machines. Post-disco acts include D. Train, Patrice Rushen, ESG, Bill Laswell, Arthur Russell. Post-disco had an important influence on dance-pop and was bridging classical disco and later forms of electronic dance music.[115]

Early hip hop

The disco sound had a strong influence on early hip hop. Most of the early hip-hop songs were created by isolating existing disco bass guitar lines and dubbing over them with MC rhymes. The Sugarhill Gang used Chic's "Good Times" as the foundation for their 1979 song "Rapper's Delight", generally considered to be the song that first popularized rap music in the United States and around the world.