Accession Day tilt

The Accession Day tilts were a series of elaborate festivities held annually at the court of Elizabeth I of England to celebrate her Accession Day, 17 November, also known as Queen's Day.[1] The tilts combined theatrical elements with jousting, in which Elizabeth's courtiers competed to outdo each other in allegorical armour and costume, poetry, and pageantry to exalt the queen and her realm of England.[2]

The last Elizabethan Accession Day tilt was held in November 1602; the queen died the following spring. Tilts continued as part of festivities marking the Accession Day of James I, 24 March, until 1624, the year before his death.[3]

Origins

Sir Henry Lee of Ditchley, Queen's Champion, devised the Accession Day tilts, which became the most important Elizabethan court festival from the 1580s.[4] The celebrations are likely to have begun somewhat informally in the early 1570s.[2] By 1581, the Queen's Day tilts "had been deliberately developed into a gigantic public spectacle eclipsing every other form of court festival", with thousands in attendance; the public were admitted for a small charge.[5] Lee himself oversaw the annual festivities until he retired as Queen's Champion at the tilt of 1590, handing over the role to George Clifford, 3rd Earl of Cumberland.[6] Following Lee's retirement, orchestration of the tilts fell to the Earl of Worcester in his capacity of Master of Horse and to the queen's favourite, the Earl of Essex, although Lee remained as a sort of Master of Ceremonies at the request of the queen.[7]

The pageants were held at the tiltyard at the Palace of Whitehall,[8] where the royal party viewed the festivities from the Tiltyard Gallery. The Office of Works constructed a platform with staircases below the gallery to facilitate presentations to the queen.[9]

Participants

Knights

Tilt lists for the Accession Day pageants have survived; these establish that the majority of the participating jousters came from the ranks of the Queen's Gentlemen Pensioners. Entrants included such powerful members of the court as the Earl of Bedford, the Earl of Oxford, the Earl of Southampton, Lord Howard of Effingham,[11] and the Earl of Essex.[12] Many of those participating had seen active service in Ireland or on the Continent, but the atmosphere of romance and entertainment seems to have predominated over the serious military exercises that were medieval tournaments.[13] Sir James Scudamore, a knight who tilted in the 1595 tournament, was immortalised as "Sir Scudamour" in Book Four of The Faerie Queene by Edmund Spenser.

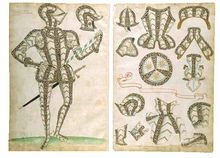

Knights participating in the spectacle entered in pageant cars or on horseback, disguised as some heroic, romantic, or metaphorical figure, with their servants in fancy dress according to the theme of the entry. A squire presented a pasteboard pageant shield decorated with the character's device or impresa to the Queen and explained the significance of his disguise in prose or poetry.[11] Entrants went to considerable expense to devise themes, order armour and costumes for their followers, and in some cases to hire poets or dramatists and even professional actors to carry out their programmes.

Classical, pastoral, and Arthurian settings were typically combined with story lines flattering to the queen, but serious subtexts were common, especially among those who used these occasions to express public contrition or desolation for having aroused the queen's displeasure, or to plead for royal favour.[15] In the painting on the left, Essex wears black (sable) armour, which he wore as part of his 1590 entrance to the tilts. At this particular tilt, Essex entered as the head of a funeral procession, carried on a bier by his attendants. This was meant to atone for his failure to subdue Ireland, but Elizabeth was not impressed and did not forgive him readily.

Poets

Poets associated with court circles who wrote allegorical verses to accompany the knights' presentations include John Davies, Edward de Vere, Philip Sidney[16] and the young Francis Bacon, who composed speeches and helped stage presentations for his patron, the Earl of Essex.[17] Sidney, in particular, as both poet and knight, embodied the chivalric themes of the tilts; a remembrance of Sidney was part of the tilt programme of 1586, the year after his death.[18] Sidney's friend and protégé Sir James Scudamore, who would go on to be one of the primary competitors in the Accession Day tilt in 1595, carried the pennant of Sidney's arms at the age of eighteen.[19] Edmund Spenser wrote of The Faerie Queene, which turns upon the Accession Day festivities as its fundamental structural device: "I devise that the Faery Queen kept her Annuall feast xii. days, upon which xii. severall days, the occasions of the xii. severall adventures hapned, which being undertaken by xii. severall knights, are in these xii. books severally handled and discoursed";[20]

A visitor's account

The fullest straightforward account of a Tilt is by Lupold von Wedel, a German traveller who saw the 1584 celebrations:

Now approached the day, when on November 17 the tournament was to be held... About twelve o’clock the queen and her ladies placed themselves at the windows in a long room at Weithol [Whitehall] palace, near Westminster, opposite the barrier where the tournament was to be held. From this room a broad staircase led downwards, and round the barrier stands were arranged by boards above the ground, so that everybody by paying 12d. would get a stand and see the play... Many thousand spectators, men, women and girls, got places, not to speak of those who were within the barrier and paid nothing.

During the whole time of the tournament all those who wished to fight entered the list by pairs, the trumpets being blown at the time and other musical instruments. The combatants had their servants clad in different colours, they, however, did not enter the barrier, but arranged themselves on both sides. Some of the servants were disguised like savages, or like Irishmen, with the hair hanging down to the girdle like women, others had horses equipped like elephants, some carriages were drawn by men, others appeared to move by themselves; altogether the carriages were very odd in appearance. Some gentlemen had their horses with them and mounted in full armour directly from the carriage. There were some who showed very good horsemanship and were also in fine attire. The manner of the combat each had settled before entering the lists. The costs amounted to several thousand pounds each.

When a gentleman with his servants approached the barrier, on horseback or in a carriage, he stopped at the foot of the staircase leading to the queen’s room, while one of his servants in pompous attire of a special pattern mounted the steps and addressed the queen in well-composed verses or with a ludicrous speech, making her and her ladies laugh. When the speech was ended he in the name of his lord offered to the queen a costly present... Now always two by two rode against each other, breaking lances across the beam... The fête lasted until five o’clock in the afternoon...[21]

See also

- Artists of the Tudor court

- Elizabethan era

- English Renaissance theatre

- The Speeches at Prince Henry's Barriers

- Jousting

Notes

- SHAFE Archived December 3, 2008, at the Wayback Machine Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, New Series IX (1895)pp. 258-9, quoted Strong, 1984, Yates Astrea etc

References

- Hutton, Ronald: The Rise and Fall of Merry England: The Ritual Year 1400-1700, Oxford University Press, 1994, ISBN 978-0-19-820363-6

- Strong, Roy: The Cult of Elizabeth: Elizabethan Portraiture and Pageantry, Thames and Hudson, 1977, ISBN 0-500-23263-6

- Strong, Roy; Art and Power; Renaissance Festivals 1450-1650, 1984, The Boydell Press, ISBN 0-85115-200-7

- Yates, Frances A.: Astraea: The Imperial Theme in the Sixteenth Century, Routledge & Keegan Paul, 1975, ISBN 0-7100-7971-0

- Young, Alan: Tudor and Jacobean Tournaments, Sheridan House, 1987, ISBN 0-911378-75-8

External links

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Accession_Day_tilt

The Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus (also known as the Ringling Bros. Circus, Ringling Bros., the Barnum & Bailey Circus, Barnum & Bailey, or simply Ringling) is an American traveling circus company billed as The Greatest Show on Earth. It and its predecessor shows ran from 1871 to 2017. Known as Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey, the circus started in 1919 when the Barnum & Bailey's Greatest Show on Earth, a circus created by P. T. Barnum and James Anthony Bailey, was merged with the Ringling Bros. World's Greatest Shows. The Ringling brothers had purchased Barnum & Bailey Ltd. following Bailey's death in 1906, but ran the circuses separately until they were merged in 1919.

After 1957, the circus no longer exhibited under its own portable "big top" tents, instead using permanent venues such as sports stadiums and arenas. In 1967, Irvin Feld and his brother Israel, along with Houston Judge Roy Hofheinz, bought the circus from the Ringling family. In 1971, the Felds and Hofheinz sold the circus to Mattel, buying it back from the toy company in 1981. Since the death of Irvin Feld in 1984, the circus had been a part of Feld Entertainment, an international entertainment firm headed by his son Kenneth Feld, with its headquarters in Ellenton, Florida.

With weakening attendance, many animal rights protests, and high operating costs, the circus performed its final show on May 21, 2017, at Nassau Veterans Memorial Coliseum and closed after 146 years.[1]

On May 18, 2022, after a five-year hiatus, Feld Entertainment announced that the circus would resume touring in the fall of 2023, but without animals like There's No Business Like Show Business (1954).[2]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ringling_Bros._and_Barnum_%26_Bailey_Circus

Circus clowns (1906)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ringling_Bros._and_Barnum_%26_Bailey_Circus

Circus Williams's elephants arriving in Rotterdam, 1961

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ringling_Bros._and_Barnum_%26_Bailey_Circus

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Schoolhouse_Rock!

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cirque_du_Soleil

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Barnum%27s_Kaleidoscape

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sarasota_Opera_House

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Center_for_Elephant_Conservation

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Florida_State_Fairgrounds

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Seminole_Gulf_Railway

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/American_Broadcasting_Company

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/King_Charles_Troupe

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ringling_Bros._and_Barnum_%26_Bailey_Clown_College

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Circus_World_(theme_park)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Walt_Disney_World

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/There%27s_No_Business_Like_Show_Business_(film)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nassau_Coliseum

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amica_Mutual_Pavilion

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Humane_Society_of_the_United_States

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reporting_mark

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rolling_stock

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Circus_train

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Robinson_Circus

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Barnum_and_Bailey%27s_Favorite

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Las_Vegas

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Principal_photography

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/20th_Century_Studios

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paramount_Pictures

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/People_for_the_Ethical_Treatment_of_Animals

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Feld_Entertainment

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Racketeer_Influenced_and_Corrupt_Organizations_Act

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/American_Society_for_the_Prevention_of_Cruelty_to_Animals

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_Department_of_Agriculture

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Animal_rights

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Federal_Government

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Federal_government_of_the_United_States

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Former_Mattel_subsidiaries

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Re-established_companies

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Recurring_events_established_in_1871

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Circuses

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Circus_festivals

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Fiction_set_in_circuses

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Circus_skills

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Circus_schools

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Ringling_Bros._and_Barnum_%26_Bailey_Circus

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Circus_museums

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Horse_circuses_and_entertainment

| Make*A*Circus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Origin | |

| Country | United States |

| Founder(s) | Peter Frankham |

| Year founded | 1975 |

| Defunct | 2002 |

Make*A*Circus was a professional, recreational, and educational circus that created free day-long events in which children observed a professional circus performance, took workshops in the circus skills of their choice, and finally performed their own circus. It took place outdoors in parks, in primarily underserved neighborhoods in the San Francisco Bay Area, and all over the state of California, with 400 to 700 children per show. It lasted for 25 years, from 1975 to 2002.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Make*A*Circus

A Day at the Circus

A Make*A*Circus day began with the company arriving in the morning and setting up bleachers, circus ring, mats, a backdrop and sideshow booths. At the same time, neighborhood groups arrived with the children they served.[5]

Teen apprentices painted children's faces and ran games in the sideshow. The youth were affiliated with the San Francisco Summer Youth program, now the Mayor’s Youth Employment and Education Program.

From 1975 to 1983, a parade was announced at noon, and children took a short walk around the neighborhood, convincing performers, placed along the pre-planned route, to join the show.

At 1:00 pm, the single ring circus show began. It included jugglers, clowns, and acrobats, as well as skills such as stilts, slack-rope, fire-eating, balancing, trapeze, and unicycling. Clown performances functioned as a narrative through-line until, beginning in 1980, all acts were included in the narrative. The show was accompanied by a live brass band. Many of the performers and band members were professionals who were also concurrently involved with other arts organizations and projects of this time including the Pickle Family Circus, and the San Francisco Mime Troupe.[5]

At 2:00 pm, the children were invited to choose the circus skill workshop of their choice. Workshops were offered in all the skills the children had just seen. The workshops lasted for 30 minutes, and included ten to 30 children.

At 3:00 pm, the second show was announced. This show starred the children and was accompanied by the band. Children performed as clowns, acrobats, jugglers, slack-rope walkers, stilt-walkers, animals, musicians, and more. Adult performers added support.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Make*A*Circus

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/San_Francisco_Arts_Commission

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Comprehensive_Employment_and_Training_Act

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/CETA_Employment_of_Artists_(1974-1981)

A hoax is a widely publicized falsehood so fashioned as to invite reflexive, unthinking acceptance by the greatest number of people of the most varied social identities and of the highest possible social pretensions to gull its victims into putting up the highest possible social currency in support of the hoax.[1]

Whereas the promoters of frauds, fakes, and scams devise them so that they will withstand the highest degree of scrutiny customary in the affair, hoaxers are confident, justifiably or not, that their representations will receive no scrutiny at all. They have such confidence because their representations belong to a world of notions fundamental to the victims' views of reality, but whose truth and importance they accept without argument or evidence, and so never question.

Some hoaxers intend eventually to unmask their representations as in fact a hoax so as to expose their victims as fools; seeking some form of profit, other hoaxers hope to maintain the hoax indefinitely, so that it is only when sceptical persons willing to investigate their claims publish their findings that at last they stand revealed as hoaxers.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hoax

A parody is a creative work designed to imitate, comment on, and/or mock its subject by means of satiric or ironic imitation. Often its subject is an original work or some aspect of it (theme/content, author, style, etc), but a parody can also be about a real-life person (e.g. a politician), event, or movement (e.g. the French Revolution or 1960s counterculture). Literary scholar Professor Simon Dentith defines parody as "any cultural practice which provides a relatively polemical allusive imitation of another cultural production or practice".[1] The literary theorist Linda Hutcheon said "parody ... is imitation, not always at the expense of the parodied text." Parody may be found in art or culture, including literature, music, theater, television and film, animation, and gaming. Some parody is practiced in theater.

The writer and critic John Gross observes in his Oxford Book of Parodies, that parody seems to flourish on territory somewhere between pastiche ("a composition in another artist's manner, without satirical intent") and burlesque (which "fools around with the material of high literature and adapts it to low ends").[2] Meanwhile, the Encyclopédie of Denis Diderot distinguishes between the parody and the burlesque, "A good parody is a fine amusement, capable of amusing and instructing the most sensible and polished minds; the burlesque is a miserable buffoonery which can only please the populace."[3] Historically, when a formula grows tired, as in the case of the moralistic melodramas in the 1910s, it retains value only as a parody, as demonstrated by the Buster Keaton shorts that mocked that genre.[4]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Parody

| Literature | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| Oral literature | ||||||

| Major written forms | ||||||

| Prose genres | ||||||

|

||||||

| Poetry genres | ||||||

|

||||||

| Dramatic genres | ||||||

| History and lists | ||||||

| Discussion | ||||||

| Topics | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Part of a series on |

| Performing arts |

|---|

Satire is a genre of the visual, literary, and performing arts, usually in the form of fiction and less frequently non-fiction, in which vices, follies, abuses, and shortcomings are held up to ridicule, often with the intent of shaming or exposing the perceived flaws of individuals, corporations, government, or society itself into improvement.[1] Although satire is usually meant to be humorous, its greater purpose is often constructive social criticism, using wit to draw attention to both particular and wider issues in society.

A feature of satire is strong irony or sarcasm —"in satire, irony is militant", according to literary critic Northrop Frye—[2] but parody, burlesque, exaggeration,[3] juxtaposition, comparison, analogy, and double entendre are all frequently used in satirical speech and writing. This "militant" irony or sarcasm often professes to approve of (or at least accept as natural) the very things the satirist wishes to question.

Satire is found in many artistic forms of expression, including internet memes, literature, plays, commentary, music, film and television shows, and media such as lyrics.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Satire

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/irony

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/humor

Hazing (American English), initiation,[1] beasting[2] (British English), bastardisation (Australian English), ragging (South Asian English) or deposition refers to any activity expected of someone in joining or participating in a group that humiliates, degrades, abuses, or endangers them regardless of a person's willingness to participate.[3]

Hazing is seen in many different types of social groups, including gangs, sports teams, schools, cliques, universities, military units, prisons, fraternities and sororities, and even workplaces in some cases. The initiation rites can range from relatively benign pranks to protracted patterns of behavior that rise to the level of abuse or criminal misconduct.[4] Hazing is often prohibited by law or institutions such as colleges and universities because it may include either physical or psychological abuse, such as humiliation, nudity, or sexual abuse.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hazing

Harassment covers a wide range of behaviors of offensive nature. It is commonly understood as behavior that demeans, humiliates or embarrasses a person, and it is characteristically identified by its unlikelihood in terms of social and moral reasonableness. In the legal sense, these are behaviors that appear to be disturbing, upsetting or threatening. Traditional forms evolve from discriminatory grounds, and have an effect of nullifying a person's rights or impairing a person from benefiting from their rights.[citation needed] When these behaviors become repetitive, it is defined as bullying. The continuity or repetitiveness and the aspect of distressing, alarming or threatening may distinguish it from insult.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harassment

One way of initiating a new member into a street gang is for multiple other members of the gang to assault the new member with a beating.[7]

Hazing activities can involve forms of ridicule and humiliation within the group or in public, while other hazing incidents are akin to pranks. A snipe hunt is such a prank, when a newcomer or credulous person is given an impossible task. Examples of snipe hunts include being sent to find a tin of Tartan paint, or a "dough repair kit" in a bakery,[8] while in the early 1900s rookies in the Canadian military were ordered to obtain a "brass magnet" when brass is not magnetic.[9]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hazing

Markings may also be made on clothing or bare skin. They are painted, written, tattooed or shaved on, sometimes collectively forming a message (one letter, syllable or word on each pledge) or may receive tarring and feathering (or rather a mock version using some glue) or branding.[citation needed]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hazing

A 2014 paper by Harvey Whitehouse[28] discusses theories that hazing can cause social cohesion though group identification and identity fusion.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hazing

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Groupthink

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stanford_prison_experiment

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rosenhan_experiment

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Group_processes

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Victimisation

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Playing_the_victim

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Victim_blaming

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scapegoating

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Just-world_hypothesis

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Smear_campaign

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Social_exclusion

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Social_undermining

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moving_the_goalposts

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blacklisting

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Smear_campaign

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Destabilisation

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Isolation_to_facilitate_abuse

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Intimidation

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Incivility

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harassment

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gaslighting

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/False_accusation

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Betrayal

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Character_assassination

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coercion

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Defamation

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Doxing

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peer_victimization

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mobbing

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Abuse

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Hazing

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dedovshchina

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anti-social_behaviour

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conscription_of_people_with_disabilities

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neglect

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dehumanization

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Denial

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Psychological_projection

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Narcissism

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Minimisation_(psychology)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lie

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Exaggeration

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rationalization_(psychology)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Privilege_escalation

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abuse_of_Privilege

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Requests_and_inquiries#Request_for_any_other_privilege

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/implied

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Domain_hijacking

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/White_privilege

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Parliamentary_privilege

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Defamation#Absolute_privilege

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Defamation

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oppression#Hierarchy_of_oppression

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caste_politics

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Genocide_justification

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Acceptable_use_policy

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_copyright

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lookism

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/State_secrets_privilege

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abuse_of_process

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Male_privilege

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Muslim_privilege

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_New_Freedom

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Human_Action#Part_Two%3A_Action_Within_the_Framework_of_Society

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Intellectual_property

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Class_discrimination

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Passing_(sociology)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neurodiversity

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Privilege_(Catholic_canon_law)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Intersectionality

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Patent

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Kingston_Gazette

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Discrimination_of_excellence

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_anti-discrimination_acts

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Short_Parliament

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Acts_of_the_Parliament_of_Great_Britain,_1770%E2%80%931779

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black_supremacy

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Corruption

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Transferred_intent

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Structural_discrimination

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Timeline_of_abolition_of_slavery_and_serfdom

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gross_negligence

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Denial-of-service_attack

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Res_ipsa_loquitur

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bill_of_Rights_1689

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tort_of_deceit

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Current_War

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Institutional_discrimination

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mueller_report

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Loss_of_use

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Evidence_(law)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/An_Apology_for_Poetry

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mueller_special_counsel_investigation

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Qui_facit_per_alium_facit_per_se

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tortious_interference

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antisemitism

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Malpractice

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trojan_horse_(computing)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trojan_horse_(computing)

Anthropocentrism (/ˌænθroʊpoʊˈsɛntrɪzəm/;[1] from Ancient Greek ἄνθρωπος (ánthrōpos) 'human being', and κέντρον (kéntron) 'center') is the belief that human beings are the central or most important entity in the universe.[2] The term can be used interchangeably with humanocentrism, and some refer to the concept as human supremacy or human exceptionalism. From an anthropocentric perspective, humankind is seen as separate from nature and superior to it, and other entities (animals, plants, minerals, etc.) are viewed as resources for humans to use.[2]

Anthropocentrism interprets or regards the world in terms of human values and experiences.[3] It is considered to be profoundly embedded in many modern human cultures and conscious acts. It is a major concept in the field of environmental ethics and environmental philosophy, where it is often considered to be the root cause of problems created by human action within the ecosphere.[4] However, many proponents of anthropocentrism state that this is not necessarily the case: they argue that a sound long-term view acknowledges that the global environment must be made continually suitable for humans and that the real issue is shallow anthropocentrism.[5][6]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anthropocentrism

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dehumanization

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/malicious-tort

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Malicious_Damage_Act_1861

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Malicious_falsehood

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Malicious

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Malicious_Intent

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Separation_of_duties

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arson

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saturday_Night_Massacre

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vienna_Convention_on_Diplomatic_Relations

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reverse_racism

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/English_defamation_law

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Watergate_scandal#Aftermath

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Malpractice#Proof_of_malpractice

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Revisionism_(Marxism)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nepotism

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Estates_General_of_1789

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fair_comment

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alienation_of_affections

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Discrimination_based_on_hair_texture

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Social_stigma_of_obesity

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Comparative_negligence

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Socioeconomic_status

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_common_misconceptions

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Numerus_clausus

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Implied_consent

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Consanguinity

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cattle_trespass

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Volenti_non_fit_injuria

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proximate_cause

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Contributory_negligence

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dissolution_of_the_monasteries

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Negligence

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Code_injection

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Assumption_of_risk

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Respondeat_superior

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Declaration_of_the_Rights_of_Man_and_of_the_Citizen

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Injunction

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Patriarchy

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stereotypes_of_Jews

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Matrix_of_domination

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_II_of_England

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Parliamentary_immunity

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scapegoating

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Negrophobia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frivolous_litigation

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/French_Revolution

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Infantilization

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blood_libel

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fall_of_the_Western_Roman_Empire

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Habeas_corpus

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Disposal_of_human_corpses

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Redlining

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abolition_of_feudalism_in_France

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Discipline

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anti-intellectualism

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Androcentrism

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bourgeoisie

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Discrimination

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Government_of_Canada

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Internment

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Power_(social_and_political)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Objectivity_(science)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nordicism#Post-Nazi_re-evaluation_and_decline_of_Nordicism

| Blackpool Tower | |

|---|---|

Looking northeast | |

Location in Blackpool | |

| General information | |

| Type | Observation Tower, Radio Tower, Tourist Attraction |

| Location | Blackpool, Lancashire, England |

| Coordinates | 53°48′57″N 3°03′19″W |

| Construction started | 1891 |

| Completed | 1894 |

| Opening | 14 May 1894 |

| Management | Blackpool Council, Merlin Entertainments Group |

| Height | |

| Roof | 518 ft 9 in (158.1 m) |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Maxwell and Tuke |

| Structural engineer | Heenan & Froude |

| Designations | |

Listed Building – Grade I | |

| Official name | Tower Buildings |

| Designated | 10 October 1973 |

| Reference no. | 1205810 |

| Website | |

| www | |

Blackpool Tower is a tourist attraction in Blackpool, Lancashire, England, which was opened to the public on 14 May 1894. When it opened, Blackpool Tower was the tallest man made structure in the British Empire.[1] Inspired by the Eiffel Tower in Paris, it is 518 feet (158 metres) tall and is the 125th-tallest freestanding tower in the world.[2] Blackpool Tower is also the common name for the Tower Buildings, an entertainment complex in a red-brick three-storey block that comprises the tower, Tower Circus, the Tower Ballroom, and roof gardens, which was designated a Grade I listed building in 1973.[3]

Background

The Blackpool Tower Company was founded by London-based Standard Contract & Debenture Corporation in 1890; it bought an aquarium on Central Promenade with the intention of building a replica Eiffel Tower on the site. John Bickerstaffe, a former mayor of Blackpool, was asked to become chairman of the new company, and its shares went on sale in July 1891. The Standard Corporation kept 30,000 £1 shares and offered £150,000 worth of shares to the public; initially only two-thirds were taken up, forcing the company to ask for more cash contributions from its existing shareholders, but the poor financial situation of the company, exacerbated by the falling share price, rendered it unable to pay. Bickerstaffe, to avoid the potential collapse of the venture, bought any available shares until his original holding of £500 amounted to £20,000. He also released the Standard Corporation from its share commitments. When the Tower opened in 1894, its success justified the investment of nearly £300,000, and the company made a £30,000 profit in 1896.[4]

Two Lancashire architects, James Maxwell and Charles Tuke, designed the tower and oversaw the laying of its foundation stone[5] on 29 September 1891.[6] By the time the Tower finally opened on 14 May 1894, both men had died.[5] Heenan & Froude, then of Manchester, were appointed structural engineers, supplying and constructing both the tower, the electric lighting and the steel front pieces for the aquariums. A new system of hydraulic riveting was used, based on the technology of Fielding & Platt of Gloucester.[7]

The total cost for the design and construction of the tower and buildings was about £290,000.[8] Five million Accrington bricks, 3,478 long tons (3,534 t) of steel and 352 long tons (358 t) of cast iron were used to construct the tower and base.[8][9] Unlike the Eiffel Tower, Blackpool Tower is not freestanding. Its base is hidden by the building that houses Blackpool Tower Circus. The building occupies a total of 6,040 square yards (1.25 acres; 5,050 m2).[3] At the summit of the tower there is a flagpole[10][11] where the height at the top measures 518 feet 9 inches (158.12 m) from the ground.[9] A time capsule was buried under the foundation stone on 25 September 1891.[8]

The tower's design was ahead of its time. As a writer for the BBC noted: "In heavy winds the building will gently sway, what a magnificent Victorian engineering masterpiece."[11]

History

When the Tower opened, 3,000 customers took the first rides to the top.[5] Tourists paid sixpence for admission, sixpence more for a ride in the lifts to the top, and a further sixpence for the circus.[8] The first members of the public to ascend the tower had been local journalists in September 1893, using constructors' ladders.[12] The top of the Tower caught fire in 1897, and the platform was seen on fire from up to 50 miles (80 km) away.[6]

The Tower was not painted properly during its first thirty years and became corroded, leading to discussions about demolishing it. However, it was decided to rebuild it instead, and all the steelwork in the structure was replaced and renewed between 1920 and 1924.[9][13] On 22 December 1894, Norwegian ship Abana was sailing from Liverpool to Savannah, Georgia, but was caught up in a storm, and mistook the recently built Blackpool Tower for a lighthouse. Abana was first seen off North Pier, and later drifted to Little Bispham where she was wrecked, and can still be seen at low tide. The ship's bell still hangs in St Andrews Church in Cleveleys.[14]

In 1940, during the Second World War, the crow's nest was removed to allow the structure to be used as a Royal Air Force radar station known as 'RAF Tower',[10] which proved unsuccessful.

A post box was opened at the top of the tower in 1949.[12] The hydraulic lifts to the top of the tower were replaced in 1956–57 and the winding-gear was converted to use an electric motor.[3]

The top of the tower was painted silver in 1977 as part of Queen Elizabeth's Silver Jubilee celebrations.[3] A giant model of King Kong was placed on the side of the tower in 1984.[3] In 1985, escapologist Karl Bartoni and his bride were married suspended in a cage from the tower.[12]

The lifts and winding gear were again replaced in 1992.[3] The same year, the tower complex was renamed Tower World, and was opened by Diana, Princess of Wales.[15] The tower is usually painted in dark red, except for its centenary year in 1994 when it was painted gold by abseiling painters.[3][10] In 1998, a "Walk of Faith" glass floor panel was opened at the top of the tower. Made up of two sheets of laminated glass, it weighs half a tonne and is two inches thick.[12] In October 2007, a laser beam installed on the Tower for the duration of the annual Illuminations was criticised by astronomer Sir Patrick Moore, presenter of television programme The Sky at Night, who said: "Light pollution is a huge problem. I am not saying we should turn all the lights out, that is not practical, but there are some things which are very unnecessary. The Blackpool Tower light is certainly something I do not think we should be doing. I very much oppose it." The beam could be seen 30 miles (48 km) away; Moore called for it to be stopped. The centre for Astrophysics at the University of Central Lancashire in Preston said the laser has added to a spiralling problem affecting astronomy.[16]

The tower has transmitters for local FM station Radio Wave 96.5 and some non-broadcast services.

The tower continued to be owned by the Bickerstaffe family until 1964, when the Blackpool Tower Company was sold to EMI.[17] Since then it has been owned by Trust House Forte, First Leisure, and Leisure Parcs Ltd, owned by Trevor Hemmings.[18] In March 2010, it was announced that Blackpool Council had bought Blackpool Tower, and that the Merlin Entertainment Group would manage it and add various attractions, including a new Dungeon attraction, and a new observation deck called Blackpool Tower Eye would operate at the top of the tower.[19] The company was also to manage the Blackpool Louis Tussauds waxwork museum, to be rebranded as Madame Tussauds.[20]

On 12 December 2021, the Tower was evacuated after reports of smoke.[21] Fire services found it was caused by an electrical fault in a neighbouring property.[22]

Blackpool Tower Eye

The top of the tower is currently known as the Blackpool Tower Eye. At a height of 380 feet (120 m), the Eye is the highest observation deck in North West England. It was previously known simply as the Tower Top, until it reopened in September 2011. Reopening after a major renovation, new owner Blackpool Council brought in Merlin Entertainments to manage the attractions, with Merlin deciding to incorporate the tower into its range of "Eye" branded attractions.[23]

Tower Ballroom

The original ballroom, the Tower Pavilion, opened in August 1894. It was smaller than the present ballroom, and occupied the front of the tower complex.[24] The Tower Ballroom was built between 1897 and 1898 to the designs of Frank Matcham, who also designed Blackpool Grand Theatre, and it opened in 1899. It was commissioned by the Tower company in response to the opening of the Empress Ballroom in the Winter Gardens. The ballroom floor is 120 ft × 102 ft (37 m × 31 m) and is made up of 30,602 blocks of mahogany, oak and walnut.[24] Above the stage is the inscription "Bid me discourse, I will enchant thine ear", from the poem Venus and Adonis by William Shakespeare. Each crystal chandelier in the ballroom can be lowered to the floor to be cleaned, which takes over a week.[25]

From 1930 until his retirement in 1970, the resident organist was Reginald Dixon, known affectionately worldwide as "Mr. Blackpool". The first Wurlitzer organ was installed in 1929, but it was replaced in 1935 by one designed by Dixon. Ernest Broadbent took over as resident organist in 1970, retiring due to ill-health in 1977. The current resident organist is Phil Kelsall who has been playing the organ at the Tower since 1975, when he started in the circus. Kelsall became resident in the ballroom in 1977, and he was awarded an MBE like Dixon in 2010 for services to music.

The ballroom was damaged by fire in December 1956; the dance floor was destroyed, along with the restaurant underneath the ballroom. Restoration took two years and cost £500,000, with many of the former designers and builders coming out of retirement to assist; the restaurant then became the Tower Lounge.[25]

The BBC series Come Dancing was televised from the Tower Ballroom for many years;[26] it has also hosted editions of Strictly Come Dancing, including the grand finals of the second and ninth series, on 11 December 2004 and 17 December 2011 respectively.[27]

The Blackpool Junior Dance Festival ("Open to the World") has been held each year in the ballroom since 1964.[24] Also, the World Modern Jive Championships are held annually.

Dancing was not originally allowed on Sundays; instead, sacred music was played. The ballroom also originally had very strict rules, including:

- "Gentlemen may not dance unless with a Lady" and

- "Disorderly conduct means immediate expulsion".[25]

The ballroom has had a number of resident dance bands including Bertini and his band, and Charlie Barlow.[28][29] Other smaller dance bands have also appeared as residents, including the Eric Delaney Band[30] and the Mike James Band.[31]

Under the management of Leisure Parcs, and the direction of bandleader Greg Francis, the Blackpool Tower Big Band was reformed in 2001 after an absence of 25 years. The New Squadronaires, the Memphis Belle Swing Orchestra and the Glenn Miller Tribute Orchestra also performed.[32] Themed nights were also introduced along with the sixteen-piece orchestra, with resident singers including Tony Benedict, Lynn Kennedy, Robert Young and Mark Porter.[citation needed] The Empress Orchestra became resident in the ballroom in 2005, alongside the specially created and smaller Empress Dance Band.[33]

The Tower's orchestrion is now in the collection of Thinktank, Birmingham Science Museum.[34] The ballroom, together with the Tower, Circus and Roof Garden, were designated a Grade I listed building in 1973.[35]

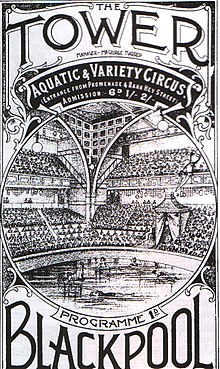

Tower Circus

The Tower Circus is positioned at the base of the tower, between its four legs. The circus first opened to the public on 14 May 1894, when admission was from 6d, and has not missed a season since.[36]

The present interior was designed by Frank Matcham and was completed in 1900.

The circus ring can be lowered into a pool of water and holds 42,000 imperial gallons (190,000 L) at a depth of up to 4 ft 6 in (1.37 m),[36] which allows for Grand Finales with Dancing Fountains. The Tower Circus is one of four left in the world that can do this.

The clown Charlie Cairoli appeared at the tower for 39 years. Britain's best-known ringmaster Norman Barrett worked the ring for 25 years, while Henry Lytton Jr. was Ringmaster here from 1954 to 1965.

Animals appeared in the circus until 1990.[36] It was planned to close the circus at the end of the 1990 season and replace it with an animatronic attraction. Public opinion and the fact the animatronics were not ready meant that the circus continued.

Today, the circus is produced and directed by Hungarian Laci Endresz, who is married to Maureen, one of the Roberts family who have a long association with the Tower Circus. A live band (sometimes accompanied by Mooky the Clown) provides all the music for the show, often dynamically syncing with the performers' movements. The circus band play a variety of different songs, usually Latin for the acts. In winter, the circus stages a pantomime instead of the regular show.

Menagerie and aquarium

Dr. Cocker's Aquarium, Aviary and Menagerie had existed on the site since 1873.[37] It was kept open to earn revenue while the Tower building went up around it, and then became one of the Tower's major attractions. The aquarium was modelled on the limestone caverns in Derbyshire. It housed 57 different species of fresh water and salt water fish, and the largest tank held 32,000 litres (7,000 imp gal; 8,500 US gal) of salt water.[38] The menagerie and aviary were regarded as one of the finest collections in the country, and included lions, tigers, and polar bears.[39]

The menagerie continued until 1973,[37] when it was closed following the opening of Blackpool Zoo near Stanley Park. Due to the Tower being run by Merlin Entertainments, which also runs the nearby Sea Life Centre, the aquarium closed in 2010, and was remodelled to make way for a new "Dungeons" attraction.[40][41]

Other attractions

Jungle Jim's Children's Indoor Play was a large indoor children's adventure playground situated within the Tower. It featured a £3 million interactive play scheme, based on a notional lost city, covering over 2,500 square metres (27,000 sq ft). Children could tackle a series of adventures in search of hidden treasure.[42] A new attraction "The Fifth Floor" which is a brand new multi-functional free family entertainment and events area opened in September 2019 as well as a VR roller coaster ride and a circus themed arcade.

The Tower Lounge Bar was a large pub with a capacity of 1,700, but staff usually limited occupancy to 1,400 for a more relaxed atmosphere. It closed down in 2014, and has since reopened as a Harry Ramsden's fish and chip restaurant.

The Blackpool Tower Dungeon is part of an international chain of Dungeon experiences operated by Merlin Entertainments. Opened in 2011, it incorporates elements of history with fear, and shows based on gallows humour. It also features "Drop Dead", a 26 ft (7.9 m) drop tower that simulates being executed by hanging. As an addition to the Dungeon brand Merlin introduced the first ever Dungeon themed Escape Room in 2017.[43]

Merlin Entertainments launched Dino Mini Golf, an indoor crazy golf course with "9 holes of prehistoric fun", in March 2018. It has been described by Aaron Edgar, the Blackpool Tower Operations manager, as "65 years in the making".[44]

Visible through the glass floor of the Tower Eye on the promenade some 380 ft (120 m) below, is Blackpool's famous Comedy Carpet.[45] In front of the tower, the Comedy Carpet by Gordon Young[46] is a celebration of the resort's long comedic history in the form of a visual pavement of jokes and catchphrases, embedded into the surface of the revamped promenade.[47] From above, it is easy to read the eternal catchphrase of the late Sir Bruce Forsyth, "Nice to see you - to see you... nice!".[48]

Tower maintenance

Painting the Tower structure takes seven years to complete,[11][18] and the workers who maintain the structure are known as "Stick Men". There are 563 steps from the roof of the Tower building to the top of the Tower, which the maintenance teams use for the structure's upkeep. If the wind speed exceeds 45 mph (72 km/h), the top of the Tower is closed as a safety precaution;[9] if the wind reaches 70 miles per hour (110 km/h) the tower top sways by an inch.[18] 5 miles (8 km) of cables are used to feed the 10,000 light bulbs which are used to illuminate the Tower.[18] In April 2002, the Tower maintenance team was featured in the BBC One programme Britain’s Toughest Jobs.[49]

Popular culture

This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2018) |

- Blackpool Tower is referred to several times in the humorous monologues written by Marriott Edgar, as performed by Stanley Holloway and others:[50][51]

- In Three Ha'pence a Foot (1932), Sam Oglethwaite escapes the consequences of declining a bargain with Noah by standing on the top of Blackpool Tower, up to his neck in floodwater, finally exclaiming "The sky's took a turn since this morning: I think it'll brighten up yet."

- In The Lion and Albert (1932)[52] and The Return of Albert (1934), Albert Ramsbottom is swallowed whole, then eventually disgorged, by a lion called "Wallace". The incident takes place in the Blackpool Tower Menagerie,[53] which did indeed have lions.

- Artists who have performed at the Tower include Arthur Askey, Duke Ellington, Paderewski, Dame Clara Butt, Cleo Laine, Peter Dawson and the band Busted.[15]

- Comedian Peter Kay performed shows in the Circus Arena on 10 and 11 April 2000; these were later released on DVD as Live at the Top of the Tower.

- The film Dick Barton Strikes Back (1947) featured a fight scene on the tower.[3]

- The film Forbidden (1949) features the tower in a climactic scene.

- The song "Up the 'Pool" from Jethro Tull's 1972 album Living in the Past briefly mentions the tower. ("The iron tower smiles down upon the silver sea...")

- The film Funny Bones (1995) features the tower in several key scenes.

- In April 2007, punk rock band Revisit performed on the Walk of Faith at the top of the tower.[54]

- Tim Burton's 2016 film Miss Peregrine's Home for Peculiar Children has its climax and last scenes surrounding Blackpool's Tower.

- The Killers filmed the music video for the song "Here with Me" in Blackpool.[55] The music video starred Winona Ryder and Craig Roberts, and included various scenes in Blackpool Pleasure Beach, and Ryder and Roberts dancing in the Tower Ballroom whilst the band perform on stage.

Visual reporting point

Known as "the tall tower", the tower is a visual reporting point (VRP) for general aviation aircraft in the local Blackpool airspace.[56]

See also

- List of tallest structures built before the 20th century

- List of works by Maxwell and Tuke

- List of towers

- Reginald Dixon

- Horace Finch

- Theatre organ

- Wade Dooley, local rugby union player capped 55 times for England and nicknamed "Blackpool Tower"

- Wurlitzers in the United Kingdom

References

When completed, Blackpool Tower was the tallest building in Britain.

External links

- The Blackpool Tower official website

- Computer-generated virtual panorama from the top of the Tower

- The Merlin Entertainments Group

- The Blackpool Tower Dungeon

- History of Blackpool Tower at pastscape.org

- Blackpool Tower at Structurae

- "Oxford DNB biography podcast: James Maxwell and Charles Tuke, architects of Blackpool Tower" (Podcast). Oxford University Press. 23 April 2014. Retrieved 12 September 2014.

- The Blackpool Comedy Carpet at Gordon Young Ltd

- Buildings and structures in Blackpool

- Tourist attractions in Blackpool

- Towers in Lancashire

- Observation towers in the United Kingdom

- Grade I listed buildings in Lancashire

- Grade I listed towers

- Towers completed in 1894

- Merlin Entertainments Group

- Rebuilt buildings and structures in the United Kingdom

- Public venues with a theatre organ

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blackpool_Tower#Tower_Ballroom

No comments:

Post a Comment