| Part of a series on |

| Renaissance music |

|---|

| Overview |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Burgundian School was a group of composers active in the 15th century in what is now northern and eastern France, Belgium, and the Netherlands, centered on the court of the Dukes of Burgundy. The school inaugurated the music of Burgundy.

The main names associated with this school are Guillaume Dufay, Gilles Binchois, Antoine Busnois and (as an influence), the English composer John Dunstaple. The Burgundian School was the first phase of activity of the Franco-Flemish School, the central musical practice of the Renaissance in Europe.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Burgundian_School

The term festa teatrale (Italian: [ˈfɛsta teaˈtraːle], plural: feste teatrali [ˈfɛste teaˈtraːli]) refers to a genre of drama, and of opera in particular. The genre cannot be rigidly defined, and in any case feste teatrali tend to be split into two different sets: feste teatrali divided by acts are operas, while works in this genre performed without division, or merely cut into two parts, are serenatas. A festa teatrale is a dramatic work, performed on stage (unlike many serenatas, which are labelled drammatico but were not performed in dramatic contexts).

The festa teatrale was always a fairly minor genre, born of courtly entertainments and the celebration of royalty – hence the abbreviated length of most festi teatrale, and the focus on drama, spectacle and chorus, as opposed to elaborate music. The poet and librettist Metastasio applied the term to 9 of his libretti. All but one of these were first performed for the court at Vienna. The last of these was Johann Adolph Hasse's Partenope, performed during 1767. Christoph Willibald Gluck's Orfeo ed Euridice, the first of his "reform operas" (also first seen at Vienna), is also often considered part of the genre of festa teatrale. Handel's Parnasso in Festa, presented in London in 1734 as part of the celebrations for the wedding of Anne, Princess Royal, is another example of the genre.[1] The genre does not seem to have survived after Metastasio, though it had been in existence for over a century – Francesco Cavalli wrote feste teatrali, among many other early composers.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Festa_teatrale

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Social_season_(United_Kingdom)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Parade

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ritual

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ceremony

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anniversary

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/World%27s_fair

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Festival

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/House_party

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ball_(dance_party)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Symposium

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wedding_reception

The Garde-Meuble de la Couronne was, in the organisation of the French royal household under the Ancien Régime, the department of the Maison du Roi responsible for the order, upkeep, storage and repair of all the furniture, art, and other movable objects in the royal palaces.

It oversaw the administration of the Beauvais Manufactory and Gobelins Manufactory.

Since 1870, the organisation is called the Mobilier National.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Garde-Meuble_de_la_Couronne

The Menus-Plaisirs du Roi (French pronunciation: [məny pleziʁ dy ʁwa]) was, in the organisation of the French royal household under the Ancien Régime, the department of the Maison du Roi responsible for the "lesser pleasures of the King", which meant in practice that it was in charge of all the preparations for ceremonies, events and festivities, down to the last detail of design and order.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Menus-Plaisirs_du_Roi

Burgundian can refer to any of the following:

- Someone or something from Burgundy.

- Burgundians, an East Germanic tribe, who first appear in history in South East Europe. Later Burgundians colonised the area of Gaul that is now known as Burgundy (French Bourgogne)

- The Old Burgundian language (Germanic), an East Germanic language spoken by the Burgundians

- The Modern Burgundian language (Oïl), an Oïl language also known as Bourguignon spoken in the region of Burgundy, France.

- Frainc-Comtou dialect, sometimes regarded as part of the Burgundian group of languages

- Burgundian (party), a political faction in early 15th century during the Hundred Years' War

See also

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Burgundian

The Burgundians (Latin: Burgundes, Burgundiōnes, Burgundī; Old Norse: Burgundar; Old English: Burgendas; Greek: Βούργουνδοι) were an early Germanic tribe or group of tribes. They appeared in the middle Rhine region, near the Roman Empire, and were later moved into the empire, in eastern Gaul. They were possibly mentioned much earlier in the time of the Roman Empire as living in part of the region of Germania that is now part of Poland.

The Burgundians are first mentioned together with the Alamanni as early as the 11th panegyric to emperor Maximian given in Trier in 291 AD, referring to events that must have happened between 248 and 291, and they apparently remained neighbours for centuries.[1] By 411 a Burgundian group had established themselves on the Rhine, between Franks and Alamanni, holding the cities of Worms, Speyer, and Strasbourg. In 436 AD, Aëtius defeated the Burgundians on the Rhine with the help of Hunnish forces, and then in 443, he re-settled the Burgundians within the empire, in eastern Gaul.

This Gaulish domain became the Kingdom of the Burgundians. This later became a component of the Frankish Empire. The name of this kingdom survives in the regional appellation, Burgundy, which is a region in modern France, representing only a part of that kingdom.

Another part of the Burgundians formed a contingent in Attila's Hunnic army by 451 AD.[2][3]

Before clear documentary evidence begins, the Burgundians may have originally emigrated from the Baltic island of Bornholm to the Vistula basin, in the middle of what is now Poland.[4]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Burgundians

Name

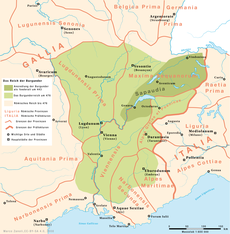

The ethnonym Burgundians is commonly used in English to refer to the Burgundi (Burgundionei, Burgundiones or Burgunds) who settled in eastern Gaul and the western Alps during the 5th century AD. The original Kingdom of the Burgundians barely intersected the modern Bourgogne and more closely matched the boundaries of Franche-Comté in northeastern France, the Rhône-Alpes in southeastern France, Romandy in west Switzerland, and Aosta Valley, in north west Italy.

In modern usage, however, "Burgundians" can sometimes refer to later inhabitants of the geographical Bourgogne or Borgogne (Burgundy), named after the old kingdom, but not corresponding to the original boundaries of it. Between the 6th and 20th centuries, the boundaries and political connections of "Burgundy" have changed frequently. In modern times the only area still referred to as Burgundy is in France, which derives its name from the Duchy of Burgundy. But in the context of the Middle Ages the term Burgundian (or similar spellings) can refer even to the powerful political entity the Dukes controlled which included not only Burgundy itself but had actually expanded to have a strong association with areas now in modern Belgium and Southern Netherlands. The parts of the old Kingdom not within the French controlled Duchy tended to come under different names, except for the County of Burgundy.

History

Uncertain early history

The origins of the Burgundians before they reached the area near the Roman-controlled Rhine is a subject of various old proposals, but these are doubted by some modern scholars such as Ian Wood and Walter Goffart. As remarked by Susan Reynolds:[5]

Wood suggests that those who were called Burgundians in their early sixth-century laws were not a single ethnic group, but covered any non-Roman follower of Gundobad and Sigismund. Some of the leaders of Goths and Burgundians may have descended from long-distant ancestors somewhere around the Baltic. Maybe, but everyone has a lot of ancestors, and some of theirs may well have come from elsewhere. There is, as Walter Goffart has repeatedly argued, little reason to believe that sixth-century or later references to what looks like names for Scandinavia, or for places in it, mean that traditions from those particular ancestors had been handed through thick and thin.

They have long been associated with Scandinavian origin based on place-name evidence and archaeological evidence (Stjerna) and many consider their tradition to be correct (e.g. Musset, p. 62). According to such proposals, the Burgundians are believed to have then emigrated to the Baltic island of Bornholm ("the island of the Burgundians" in Old Norse). By about 250 AD, the population of Bornholm had largely disappeared from the island. Most cemeteries ceased to be used, and those that were still used had few burials (Stjerna, in German 1925:176). In Þorsteins saga Víkingssonar (The Saga of Thorstein, Viking's Son), a man (or group) named Veseti settled on a holm (island) called borgundarhólmr in Old Norse, i.e. Bornholm. Alfred the Great's translation of Orosius uses the name Burgenda land to refer to a territory next to the land of Sweons ("Swedes").[6] The 19th century poet and mythologist Viktor Rydberg asserted from an early medieval source, Vita Sigismundi, that they themselves retained oral traditions about their Scandinavian origin.

Early Roman sources, such as Tacitus and Pliny the Elder, knew little concerning the Germanic peoples east of the Elbe river, or on the Baltic Sea. Pliny (IV.28) however mentions a group with a similar name among the Vandalic or Eastern Germanic Germani peoples, including the Goths. Claudius Ptolemy lists these as living between the Suevus (probably the Oder) and Vistula rivers, north of the Lugii, and south of the coast dwelling tribes. Around the mid-2nd century AD, there was a significant migration by Germanic tribes of Scandinavian origin (Rugii, Goths, Gepidae, Vandals, Burgundians, and others)[7] towards the south-east, creating turmoil along the entire Roman frontier.[7][8][9][10] These migrations culminated in the Marcomannic Wars, which resulted in widespread destruction and the first invasion of Italy in the Roman Empire period.[10] Jordanes reports that during the 3rd century AD, the Burgundians living in the Vistula basin were almost annihilated by Fastida, king of the Gepids, whose kingdom was at the mouth of the Vistula.

In the late 3rd century AD, the Burgundians appeared on the east bank of the Rhine, apparently confronting Roman Gaul. Zosimus (1.68) reports them being defeated by the emperor Probus in 278 near a river, together with the Silingi and Vandals. A few years later, Claudius Mamertinus mentions them along with the Alamanni, a Suebic people. These two peoples had moved into the Agri Decumates on the eastern side of the Rhine, an area still referred to today as Swabia, at times attacking Roman Gaul together and sometimes fighting each other. He also mentions that the Goths had previously defeated the Burgundians.

Ammianus Marcellinus, on the other hand, claimed that the Burgundians descended from the Romans. The Roman sources do not speak of any specific migration from Poland by the Burgundians (although other Vandalic peoples are more clearly mentioned as having moved west in this period), and so there have historically been some doubts about the link between the eastern and western Burgundians.[11]

In 369/370 AD, the Emperor Valentinian I enlisted the aid of the Burgundians in his war against the Alamanni.

Approximately four decades later, the Burgundians appear again. Following Stilicho's withdrawal of troops to fight Alaric I the Visigoth in 406–408 AD, a large group of peoples from central Europe north of the Danube came west and crossed the Rhine, entering the Empire near the lands of the Burgundians who had moved much earlier. The dominant groups were Alans, Vandals (Hasdingi and Silingi), and Danubian Suevi. The majority of these Danubian peoples moved through Gaul and eventually established themselves in kingdoms in Roman Hispania. One group of Alans was settled in northern Gaul by the Romans.

Some Burgundians also migrated westwards and settled as foederati in the Roman province of Germania Prima along the Middle Rhine. Other Burgundians, however, remained outside the empire and apparently formed a contingent in Attila's Hunnic army by 451 AD.[2][3]

Kingdom

Rhineland

In 411, the Burgundian king Gundahar (or Gundicar) set up a puppet emperor, Jovinus, in cooperation with Goar, king of the Alans. With the authority of the Gallic emperor that he controlled, Gundahar settled on the left (Roman) bank of the Rhine, between the river Lauter and the Nahe, seizing Worms, Speyer, and Strassburg. Apparently as part of a truce, the Emperor Honorius later officially "granted" them the land,[12] with its capital at the old Celtic Roman settlement of Borbetomagus (present Worms).

Despite their new status as foederati, Burgundian raids into Roman Upper Gallia Belgica became intolerable and were ruthlessly brought to an end in 436, when the Roman general Aëtius called in Hun mercenaries, who overwhelmed the Rhineland kingdom in 437. Gundahar was killed in the fighting, reportedly along with the majority of the Burgundian tribe.[13]

The destruction of Worms and the Burgundian kingdom by the Huns became the subject of heroic legends that were afterwards incorporated in the Nibelungenlied—on which Wagner based his Ring Cycle—where King Gunther (Gundahar) and Queen Brünhild hold their court at Worms, and Siegfried comes to woo Kriemhild. (In Old Norse sources the names are Gunnar, Brynhild, and Gudrún as normally rendered in English.) In fact, the Etzel of the Nibelungenlied is based on Attila the Hun.

Settlement in eastern Gaul

For reasons not cited in the sources, the Burgundians were granted foederati status a second time, and in 443 were resettled by Aëtius in Sapaudia[n 1], part of the Gallo-Roman province of Maxima Sequanorum.[15] Burgundians probably even lived near Lugdunum, known today as Lyon.[16] A new king, Gundioc or Gunderic, presumed to be Gundahar's son, appears to have reigned following his father's death.[17] The historian Pline[citation needed] tells us that Gunderic ruled the areas of Saône, Dauphiny, Savoie and a part of Provence. He set up Vienne as the capital of the kingdom of Burgundy. In all, eight Burgundian kings of the house of Gundahar ruled until the kingdom was overrun by the Franks in 534.

As allies of Rome in its last decades, the Burgundians fought alongside Aëtius and a confederation of Visigoths and others against Attila at the Battle of Châlons (also called "The Battle of the Catalaunian Fields") in 451. The alliance between Burgundians and Visigoths seems to have been strong, as Gundioc and his brother Chilperic I accompanied Theodoric II to Spain to fight the Sueves in 455.[18]

Aspirations to the empire

Also in 455, an ambiguous reference infidoque tibi Burdundio ductu[19] implicates an unnamed treacherous Burgundian leader in the murder of the emperor Petronius Maximus in the chaos preceding the sack of Rome by the Vandals. The Patrician Ricimer is also blamed; this event marks the first indication of the link between the Burgundians and Ricimer, who was probably Gundioc's brother-in-law and Gundobad's uncle.[20]

In 456, the Burgundians, apparently confident in their growing power, negotiated a territorial expansion and power sharing arrangement with the local Roman senators.[21]

In 457, Ricimer overthrew another emperor, Avitus, raising Majorian to the throne. This new emperor proved unhelpful to Ricimer and the Burgundians. The year after his ascension, Majorian stripped the Burgundians of the lands they had acquired two years earlier. After showing further signs of independence, he was murdered by Ricimer in 461.

Ten years later, in 472, Ricimer–who was by now the son-in-law of the Western Emperor Anthemius–was plotting with Gundobad to kill his father-in-law; Gundobad beheaded the emperor (apparently personally).[22] Ricimer then appointed Olybrius; both died, surprisingly of natural causes, within a few months. Gundobad seems then to have succeeded his uncle as Patrician and king-maker, and raised Glycerius to the throne.[23]

In 474, Burgundian influence over the empire seems to have ended. Glycerius was deposed in favor of Julius Nepos, and Gundobad returned to Burgundy, presumably at the death of his father Gundioc. At this time or shortly afterwards, the Burgundian kingdom was divided among Gundobad and his brothers, Godigisel, Chilperic II, and Gundomar I.[24]

Consolidation of the kingdom

According to Gregory of Tours, the years following Gundobad's return to Burgundy saw a bloody consolidation of power. Gregory states that Gundobad murdered his brother Chilperic, drowning his wife and exiling their daughters (one of whom was to become the wife of Clovis the Frank, and was reputedly responsible for his conversion).[25] This is contested by, e.g., Bury, who points out problems in much of Gregory's chronology for the events.

In c. 500, when Gundobad and Clovis were at war, Gundobad appears to have been betrayed by his brother Godegisel, who joined the Franks; together Godegisel's and Clovis' forces "crushed the army of Gundobad".[26] Gundobad was temporarily holed up in Avignon, but was able to re-muster his army and sacked Vienne, where Godegisel and many of his followers were put to death. From this point, Gundobad appears to have been the sole king of Burgundy.[27] This would imply that his brother Gundomar was already dead, though there are no specific mentions of the event in the sources.

Either Gundobad and Clovis reconciled their differences, or Gundobad was forced into some sort of vassalage by Clovis' earlier victory, as the Burgundian king appears to have assisted the Franks in 507 in their victory over Alaric II the Visigoth.

During the upheaval, sometime between 483 and 501, Gundobad began to set forth the Lex Gundobada (see below), issuing roughly the first half, which drew upon the Lex Visigothorum.[17] Following his consolidation of power, between 501 and his death in 516, Gundobad issued the second half of his law, which was more originally Burgundian.

Fall

The Burgundians were extending their power over eastern Gaul—that is western Switzerland and eastern France, as well as northern Italy. In 493, Clovis, king of the Franks, married the Burgundian princess Clotilda (daughter of Chilperic), who converted him to the Catholic faith.

At first allied with Clovis' Franks against the Visigoths in the early 6th century, the Burgundians were eventually conquered at Autun by the Franks in 532 after a first attempt in the Battle of Vézeronce. The Burgundian kingdom was made part of the Merovingian kingdoms, and the Burgundians themselves were by and large absorbed as well.

Physical appearance

The 5th century Gallo-Roman poet and landowner Sidonius, who at one point lived with the Burgundians, described them as a long-haired people of immense physical size:

Why... do you [an obscure senator by the name of Catullinus] bid me compose a song dedicated to Venus... placed as I am among long-haired hordes, having to endure Germanic speech, praising often with a wry face the song of the gluttonous Burgundian who spreads rancid butter on his hair? ... You don't have a reek of garlic and foul onions discharged upon you at early morn from ten breakfasts, and you are not invaded before dawn... by a crowd of giants.[28]

Language

| Burgundian | |

|---|---|

| Region | Germania |

| Extinct | 6th century |

Indo-European

| |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | None (mis) |

qlb | |

| Glottolog | None |

The Burgundians and their language were described as Germanic by the poet Sidonius Apollinaris.[29] Herwig Wolfram has interpreted this as being because they had entered Gaul from Germania.[30]

More specifically their language is thought to have belonged to the East Germanic language group, based upon their presumed equivalence to the Burgundians named much earlier by Pliny in the east, and some names and placenames. However this is now considered uncertain.[31] Little is known of the language. Some proper names of Burgundians are recorded, and some words used in the area in modern times are thought to be derived from the ancient Burgundian language,[32] but it is often difficult to distinguish these from Germanic words of other origin, and in any case the modern form of the words is rarely suitable to infer much about the form in the old language.

The language appears to have become extinct during the late 6th century, likely due to the early conversion of the Burgundians to Latin Christianity.[32]

Religion

Somewhere in the east the Burgundians had converted to the Arian Christianity from earlier Germanic paganism. Their Arianism proved a source of suspicion and distrust between the Burgundians and the Catholic Western Roman Empire.

Divisions were evidently healed or healing circa 500, however, as Gundobad, one of the last Burgundian kings, maintained a close personal friendship with Avitus, the bishop of Vienne. Moreover, Gundobad's son and successor, Sigismund, was himself a Catholic, and there is evidence that many of the Burgundian people had converted by this time as well, including several female members of the ruling family.

Law

The Burgundians left three legal codes, among the earliest from any of the Germanic tribes.

The Liber Constitutionum sive Lex Gundobada ("The Book of Constitutions or Law of Gundobad"), also known as the Lex Burgundionum, or more simply the Lex Gundobada or the Liber, was issued in several parts between 483 and 516, principally by Gundobad, but also by his son, Sigismund.[33] It was a record of Burgundian customary law and is typical of the many Germanic law codes from this period. In particular, the Liber borrowed from the Lex Visigothorum[34] and influenced the later Lex Ripuaria.[35] The Liber is one of the primary sources for contemporary Burgundian life, as well as the history of its kings.

Like many of the Germanic tribes, the Burgundians' legal traditions allowed the application of separate laws for separate ethnicities. Thus, in addition to the Lex Gundobada, Gundobad also issued (or codified) a set of laws for Roman subjects of the Burgundian kingdom, the Lex Romana Burgundionum (The Roman Law of the Burgundians).

In addition to the above codes, Gundobad's son Sigismund later published the Prima Constitutio.

See also

- Dauphiné

- Duchy of Burgundy

- Franche-Comté

- List of ancient Germanic peoples and tribes

- List of kings of Burgundy

- Nibelung (later legends of the Burgundian kings)

Notes

- The territory, which has no modern counterpart, was perhaps bounded by the rivers Ain and Rhône, Lake Geneva, the Jura and the Aar, though historians differ, and there seems to be insufficient evidence.[14]

References

- Rivers, p. 9

Sources

- Buchberger, Erica (2018). "Burgundians". In Nicholson, Oliver (ed.). The Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780191744457. Retrieved January 26, 2020.

- Bury, J. B. The Invasion of Europe by the Barbarians. London: Macmillan and Co., 1928.

- Dalton, O. M. The History of the Franks, by Gregory of Tours. Oxford: The Clarendon Press, 1927.

- Darvill, Timothy, ed. (2009). "Burgundians". The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Archaeology (3 ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780191727139. Retrieved January 26, 2020.

- Drew, Katherine Fischer. The Burgundian Code. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1972.

- Drinkwater, John Frederick (2012). "Burgundians". In Hornblower, Simon; Spawforth, Antony; Eidinow, Esther (eds.). The Oxford Classical Dictionary (4 ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780191735257. Retrieved January 25, 2020.

- Gordon, C.D. The Age of Attila. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1961.

- Guichard, Rene, Essai sur l'histoire du peuple burgonde, de Bornholm (Burgundarholm) vers la Bourgogne et les Bourguignons, 1965, published by A. et J. Picard et Cie.

- Hartmann, Frederik / Riegger, Ciara. 2021. The Burgundian language and its phylogeny - A cladistical investigation. Nowele 75, p. 42-80.

- Heather, Peter (June 11, 2007). The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195325416. Retrieved May 31, 2015.

- Hitchner, R. Bruce (2005). "Burgundians". In Kazhdan, Alexander P. (ed.). The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195187922. Retrieved January 26, 2020.

- Murray, Alexander Callander. From Roman to Merovingian Gaul. Broadview Press, 2000.

- Musset, Lucien. The Germanic Invasions: The Making of Europe AD 400–600. University Park, Pennsylvania: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 1975. ISBN 978-0-271-01198-1.

- Nerman, Birger. Det svenska rikets uppkomst. Generalstabens litagrafiska anstalt: Stockholm. 1925.

- Rivers, Theodore John. Laws of the Salian and Ripuarian Franks. New York: AMS Press, 1986.

- Rolfe, J.C., trans, Ammianus Marcellinus. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1950.

- Shanzer, Danuta. 'Dating the Baptism of Clovis.' In Early Medieval Europe, volume 7, pages 29–57. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers Ltd, 1998.

- Shanzer, D. and I. Wood. Avitus of Vienne: Letters and Selected Prose. Translated with an Introduction and Notes. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2002.

- Werner, J. (1953). "Beiträge sur Archäologie des Attila-Reiches", Die Bayerische Akademie der Wissenschaft. Abhandlungen. N.F. XXXVIII A Philosophische-philologische und historische Klasse. Münche

- Wolfram, Herwig (1997). The Roman Empire and Its Germanic Peoples. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520085114.

- Wood, Ian N. "Ethnicity and the Ethnogenesis of the Burgundians". In Herwig Wolfram and Walter Pohl, editors, Typen der Ethnogenese unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Bayern, volume 1, pages 53–69. Vienna: Denkschriften der Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1990.

- Wood, Ian N. The Merovingian Kingdoms. Harlow, England: The Longman Group, 1994.

External links

Media related to Burgundians at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Burgundians at Wikimedia Commons

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Burgundians

Language

| Burgundian | |

|---|---|

| Region | Germania |

| Extinct | 6th century |

Indo-European

| |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | None (mis) |

qlb | |

| Glottolog | None |

The Burgundians and their language were described as Germanic by the poet Sidonius Apollinaris.[29] Herwig Wolfram has interpreted this as being because they had entered Gaul from Germania.[30]

More specifically their language is thought to have belonged to the East Germanic language group, based upon their presumed equivalence to the Burgundians named much earlier by Pliny in the east, and some names and placenames. However this is now considered uncertain.[31] Little is known of the language. Some proper names of Burgundians are recorded, and some words used in the area in modern times are thought to be derived from the ancient Burgundian language,[32] but it is often difficult to distinguish these from Germanic words of other origin, and in any case the modern form of the words is rarely suitable to infer much about the form in the old language.

The language appears to have become extinct during the late 6th century, likely due to the early conversion of the Burgundians to Latin Christianity.[32]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Burgundians#Language

This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2020) |

| Burgundian | |

|---|---|

| bregognon | |

| Native to | France |

| Region | Burgundy |

Native speakers | (50,000 have some knowledge of the language cited 1988)[1] 20,000 (2022)[2] |

Early forms | |

| Latin | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Glottolog | bour1247 |

| Linguasphere | 51-AAA-hk & 51-AAA-hl |

Situation of Burgundian (in lilac) among the Oïl languages. | |

Burgundian is classified as Severely Endangered by the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger [4] | |

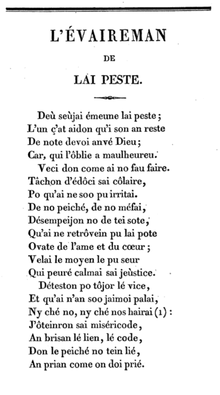

The Burgundian language, also known by French names Bourguignon-morvandiau, Bourguignon, and Morvandiau, is an Oïl language spoken in Burgundy and particularly in the Morvan area of the region.

The arrival of the Burgundians brought Germanic elements into the Gallo-Romance speech of the inhabitants. The occupation of the Low Countries by the Dukes of Burgundy also brought Burgundian into contact with Dutch; e.g., the word for gingerbread couque derives from Middle Dutch kooke (cake).

Dialects of the south along the Saône river, such as Brionnais-Charolais, have been influenced by the Arpitan language, which is spoken mainly in a neighbouring area that approximates the heartland of the original Kingdom of Burgundy.

Eugène de Chambure published a Glossaire du Morvan in 1878.[5]

Literature

Apart from songs dating from the eighteenth century, there is little surviving literature from before the nineteenth century. In 1854 the Papal Bull Ineffabilis Deus was translated into the Morvan dialect by the Abbé Jacques-François Baudiau, and into the Dijon dialect by the Abbé Lereuil. The Abbé Baudiau also transcribed storytelling.

Folklorists collected vernacular literature from the mid-nineteenth century and by the end of the century a number of writers were establishing an original literature. Achille Millien (1838–1927) collected songs from the oral tradition in the Nivernais. Louis de Courmont, nicknamed the "Botrel of the Morvan," was a chansonnier who after a career in Paris returned to his native region. A statue was erected to him in Château-Chinon. Emile Blin wrote a number of stories and monologues aimed at a tourist market; a collection was published in 1933 under the title Le Patois de Chez Nous. Alfred Guillaume published a large number of vernacular texts for use on picturesque postcards at the beginning of the twentieth century, and in 1923 published a book in Burgundian, L'âme du Morvan. More recently, Marinette Janvier published Ma grelotterie (1974) and Autour d'un teugnon (1989).

References

- Le morvandiau tel qu'on le parle, Roger Dron, Autun 2004, (no ISBN)

- Paroles d'oïl, 1994, ISBN 2-905061-95-2

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Burgundian_language_(O%C3%AFl)

This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2010) |

This article includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. (April 2023) |

|

| Frainc-Comtou | |

|---|---|

| Native to | France, Switzerland |

| Region | Franche-Comté, Canton of Jura, Bernese Jura |

Native speakers | (undated figure of c. 1,000) |

Early forms | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Glottolog | fran1270 |

| Linguasphere | 51-AAA-ja & 51-AAA-hc |

Situation of Frainc-Comtou among the Oïl languages. | |

Frainc-Comtou (French: franc-comtois) is a Romance language of the langues d'oïl language family spoken in the Franche-Comté region of France and in the Canton of Jura and Bernese Jura in Switzerland.

Sample vocabulary

| Word | French Translation | English Translation | Usage Example | French Translation | English Translation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| avoir meilleur temps | avoir avantage à (faire d'une certaine façon) | have/had better | tu as meilleur temps d'y aller (par opposition à rester). | tu ferais mieux d'y aller (plutôt que de rester) | you’d better go |

| bon as in "avoir/faire bon chaud" | - | comfortably | il fait bon chaud | il fait agréablement chaud | it’s comfortably warm |

| fin | - | wily | il est pas bien fin | il n’est pas très malin/futé | he’s not very wily |

| frayer | - | to streak (window panes) | ne fraye pas les vitres ! | don’t streak the panes ! | |

| pépet/pépêt | thick and lightly sticky | cette crème est un peu pépêt. Ne cuis pas trop les patates, ça va devenir du pépet. | (as for cream, dessert). Don't overcook the potatoes... | ||

| douillet | - | onctuous and lightly heavy to digest | un dessert douillet |

| |

| fier | - | sour | un fruit fier, une pêche fière | a sour peach | |

| crû | - | cool, lightly damp and chilly | il fait crû |

| |

| dépiouler/dépieuler | perdre ses aiguilles (sapin) | drop their needles (as of firs) | le sapin, y dépioule | the fir is dropping their needles | |

| cheni / chni | tas de poussières, saletés après avoir balayé | pile of dust, coarser dust (after sweeping the floor) | ramasse le cheni !

avoir un cheni dans l'oeil |

clean up / brush up the dust ! | |

| voir (adverbe) | - | (used superfluously, as a verbosity) | viens voir l’eau! | can you pass me the water! | |

| viôce, viosse, viôsse, viausse | - | (used pejoratively especially for a cow, horse, or mule) nasty critter | elle veut pas avancer cette viôce! | this nasty critter doesn’t want to move! | |

| récurer | passer la serpillière | to mop | tu peux récurer la cuisine si tu veux | you may mop in the kitchen if you like | |

| s’oublier | - | to oversleep | je me suis oublié | I overslept | |

| taper (au bout) | - | to take more from an end piece of food

(as of bread, saucisson…) |

tape au bout ! | have more ! | |

| beau (en parlant d’un enfant) | sweet, nice (as of a child) | tu peux ranger le pot d’eau, et tu seras beau! | can you put the jug away, you’ll be so nice! | ||

| émichloquer | to convolute, to | make tortuous | |||

| rapondre | raccorder | link together | Rapondre les bouts d'une courroie plate. | raccorder les bouts d'une courroie plate | Joint the ends of a flat drive belt. |

| raponce | raccord | joint | Te fous pas les doigts dans la raponce de la courroie. | Prends garde à tes doigts avec le raccord de la courroie. | Careful with the belt joint. |

| au bout le bout | l’un après l’autre/ les uns après les autres | one after the other in a line | |||

| cornet | sachet en plastique | plastic bag | |||

| se gêner | - | to be timid | |||

| arquer | marcher | walk, proceed | Je ne peux plus arquer | Je ne peux plus marcher | I cannot walk anymore |

| chouiner | pleurer | weep | Arrête de chouiner | Arrête de pleurer | Stop crying / weeping / sobbing |

| cornet | sac en plastique (à l'origine, un sac conique fait avec du papier journal sur les marchés). | plastic bag | (dans un magasin): vous voulez un cornet? | Vous voulez un sac? | |

| cru | froid et humide | cold and wet | |||

| daubot | idiot, simplet | stupid | Il est un peu daubot | Il est un peu idiot | He's a bit dumb. |

| fier | acide, amer | sour | Ce vin est fier | Ce vin est acide | This wine is sour. |

| clairer | luire (verbe intransitif, alors que éclairer est transitif) | luire | T'as laissé clairer la lampe du sous-sol. | Tu a laissé la lampe du sous-sol allumée | You left the light on in the basement. |

| gaugé | trempé | drenched | (un jour de pluie) J'ai marché dans l'herbe, je suis gaugé. | J'ai marché dans l'herbe, je suis trempé. | I walked in the grass, I'm drenched. |

| gauper | habiller | dress | Elle est mal gaupée. | Elle est mal habillée | She's badly dressed. |

| grailler | manger | eat | Y'a rien à grailler dans c'te baraque. | Il n'y a rien à manger dans cette maison. | There is nothing to eat in this house. |

| pê, pêute (prononcer pe comme le début de penaud) | laid, laide | ugly | |||

| pelle à cheni | ramasse-poussière | dustpan | |||

| treuiller | boire | drink | |||

| yoyoter | dire des sornettes, dérailler (au sens d'être sénile). | tell nonsense | Elle a 102 ans, mais elle yoyote pas du tout. | Elle a 102 ans, mais a encore toute sa tête. | |

|

|

|

|

Bibliography

- Dalby, David (1999/2000). The Linguasphere Register of the World's Languages and Speech Communities. (Vol. 2). Hebron, Wales, UK: Linguasphere Press. ISBN 0-9532919-2-8.

See also

- Languages of France

- Languages of Switzerland

- Linguasphere Observatory (Observatoire Linguistique)

References

- Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin; Bank, Sebastian (2022-05-24). "Oil". Glottolog. Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. Archived from the original on 2022-10-08. Retrieved 2022-10-07.

External links

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frainc-Comtou

This article may be expanded with text translated from the corresponding article in French. (December 2019) Click [show] for important translation instructions. |

The Burgundian party was a political allegiance against France that formed during the latter half of the Hundred Years' War. The term "Burgundians" refers to the supporters of the Duke of Burgundy, John the Fearless, that formed after the assassination of Louis I, Duke of Orléans. Their opposition to the Armagnac party, the supporters of Charles, Duke of Orléans, led to a civil war in the early 15th century, itself part of the larger Hundred Years' War.

Geography

The Duke of Burgundy had inherited a large number of lands scattered from what is now the border of Switzerland up to the North Sea. The Duchy of Burgundy had been granted as an appanage to Philip the Bold in the 14th century, and this was followed by other territories inherited by Philip and his heirs during the late 14th and 15th centuries, including the County of Burgundy (the Franche-Comté), Flanders, Artois and many other domains in what are now Belgium, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and northeastern France. Prosperous textile manufacture in the Low Countries made this among the wealthiest realms in Europe, and explained their desire to maintain trade with wool-producing England.

Politics

Partisan use of the term "Burgundian" arose from a feud between John II, Duke of Burgundy and Louis of Valois, Duke of Orléans. The latter was the brother of King Charles VI, the former was his cousin. When Charles VI’s mental illness interrupted his ability to rule, John II and Louis I vied for power in a bitter dispute. Popular rumor attributed an adulterous affair to the Duke of Orléans and French queen Isabeau of Bavaria. Supporters of the two dukes became known as "Burgundians" and "Orleanists", respectively.

Other than in Burgundy's own lands, the Duke's supporters were particularly powerful in Paris, where the butchers' guild, notably, closely supported him.

The partisan terms outlasted the lives of these two men. John, Duke of Burgundy ordered the assassination of Louis of Orléans in 1407. Burgundian partisans at the University of Paris published a treatise justifying this as tyrannicide in the belief that the Duke of Orléans had been plotting to kill the king and usurp the throne. Leadership of his party passed nominally to his son, Charles, but in fact to the young duke's father-in-law, Bernard VII, Count of Armagnac. Bernard VII would form a league in opposition to the Burgundians in Gien, the Armagnac party. Both parties sought the support of the Kingdom of England. The Armagnacs through treaty with the English King Henry IV, to secure his military aid; the Burgundians by remaining neutral when the English invaded Normandy. That neutrality led to Orléans's capture by the English at Agincourt in 1415. After Armagnac's murder by a Burgundian mob in Paris in 1418, leadership of the party devolved upon the young Dauphin, who retreated to Bourges.

After 1418, then, Burgundy controlled both Paris and the person of the king. However, the whole dispute was proving deleterious to the war effort against the English, as both sides focused more on fighting one another than on preventing the English from conquering Normandy. In 1419, the Duke and the Dauphin negotiated a truce to allow both sides to focus on fighting the English. However, in a further parley, the Duke was murdered by the Dauphin's supporters as revenge for the murder of Orléans twelve years before.

Burgundian party leadership passed to Philip III, Duke of Burgundy. Duke Philip entered an alliance with England. Due to his influence and that of the queen, Isabeau, who had by now joined the Burgundian party, the mad king was induced to sign the Treaty of Troyes with England in 1420, by which Charles VI recognized Henry V of England as his heir, disinheriting his own son the Dauphin.

When Henry V and Charles VI both died within months of each other, leaving Henry's son Henry VI of England as heir to both England and France, Philip the Good and the Burgundians continued to support the English. Nevertheless, dissension grew between Philip and the English regent, John, Duke of Bedford. Although family ties between Burgundy and Bedford (who had married the Duke's sister) prevented an outright rupture during Bedford's lifetime. Burgundy gradually withdrew support for the English and began to seek an understanding with the Dauphin, by now Charles VII of France. The two sides finally reconciled at the Congress of Arras in 1435, resulting in a treaty which allowed the French king to finally return to his capital.

Notable Burgundians

- John the Fearless, Duke of Burgundy

- Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy

- Jean Petit, Theologian at the University of Paris

- Claude de Beauvoir, Marshal of France

- Nicolas Rolin, Chancellor of Burgundy

- Simon Caboche, prominent member of the Parisian butcher's guild

- Pierre Cauchon, Bishop of Beauvais

See also

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Burgundian_(party)

Joan of Arc | |

|---|---|

Historiated initial depicting Joan (dated to the second half of the 15th century, Archives Nationales, Paris, AE II 2490)[a] | |

| Virgin | |

| Born | c. 1412 Domrémy, Duchy of Bar, Kingdom of France |

| Died | 30 May 1431 (aged c. 19) Rouen, Normandy (then under English rule) |

| Venerated in | |

| Beatified | 18 April 1909 by Pope Pius X |

| Canonized | 16 May 1920 by Pope Benedict XV |

| Feast | 30 May |

| Patronage | France |

Joan of Arc (French: Jeanne d'Arc pronounced [ʒan daʁk]; c. 1412 – 30 May 1431) is a patron saint of France, honored as a defender of the French nation for her role in the siege of Orléans and her insistence on the coronation of Charles VII of France during the Hundred Years' War. Claiming to be acting under divine guidance, she became a military leader who transcended gender roles and gained recognition as a savior of France.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joan_of_Arc

| Philip the Good | |

|---|---|

Philip, wearing the collar of firesteels of the Order of the Golden Fleece he instituted, copy of a Rogier van der Weyden of c. 1450 | |

| Duke of Burgundy | |

| Reign | 10 September 1419 – 15 June 1467 |

| Predecessor | John the Fearless |

| Successor | Charles the Bold |

| Born | 31 July 1396 Dijon, Duchy of Burgundy |

| Died | 15 June 1467 (aged 70) Bruges, Flanders, Burgundian Netherlands |

| Burial | |

| Spouse | |

| Issue among others |

Illegitimate: |

| House | Valois-Burgundy |

| Father | John the Fearless |

| Mother | Margaret of Bavaria |

| Signature |  |

Philip III (French: Philippe le Bon; Dutch: Filips de Goede; 31 July 1396 in Dijon – 15 June 1467 in Bruges) was Duke of Burgundy from 1419 until his death. He was a member of a cadet line of the Valois dynasty, to which all 15th-century kings of France belonged. During his reign, the Burgundian State reached the apex of its prosperity and prestige, and became a leading centre of the arts.

Philip is known for his administrative reforms, his patronage of Flemish artists such as Jan van Eyck and Franco-Flemish composers such as Gilles Binchois, and perhaps most significantly the seizure of Joan of Arc, whom Philip ransomed to the English after his soldiers captured her, resulting in her trial and eventual execution. In political affairs, he alternated between alliances with the English and the French in an attempt to improve his dynasty's powerbase. Additionally, as ruler of Flanders, Brabant, Limburg, Artois, Hainaut, Holland, Luxembourg, Zeeland, Friesland and Namur, he played an important role in the history of the Low Countries.

He was married three times, and had three sons, only one of whom reached adulthood. He had 24 documented mistresses and fathered at least 18 illegitimate children.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philip_the_Good

| Armagnac–Burgundian Civil War | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Hundred Years' War | ||||||||

The Cabochien revolt in 1413 | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| Belligerents | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | ||||||||

|

|

|

| ||||||

The Armagnac–Burgundian Civil War was a conflict between two cadet branches of the French royal family – the House of Orléans (Armagnac faction) and the House of Burgundy (Burgundian faction) from 1407 to 1435. It began during a lull in the Hundred Years' War against the English and overlapped with the Western Schism of the papacy.

Causes

The leaders of both parties were closely related to the French king through the male line. For this reason, they were called "princes of the blood", and exerted much influence on the affairs of the kingdom of France. Their rivalries and disputes for control of the government would serve as much of the basis for the conflict. The Orléans branch of the family, also referred to as House of Valois-Orléans, stemmed from Louis I, Duke of Orléans, younger son of King Charles V of France (r. 1364–1380). The House of Valois-Burgundy originated from Charles V's youngest brother, Philip the Bold, the Duke of Burgundy. Both their respective namesake duchies of Orléans and Burgundy were held in the status of appanage, as none of its holders were first in the line of succession to the French throne.

The war's causes were rooted in the reign of Charles VI of France (Charles V's eldest son and successor) and a confrontation between two different economic, social and religious systems. On the one hand was France, very strong in agriculture, with a strong feudal and religious system, and on the other was England, a country whose rainy climate favoured pasture and sheep farming and where artisans, the middle classes and cities were important.[citation needed] The Burgundians were in favour of the English model (the more so since the County of Flanders, whose cloth merchants were the main market for English wool, belonged to the Duke of Burgundy), while the Armagnacs defended the French model. In the same way, the Western Schism induced the election of an Armagnac-backed antipope based at Avignon, Pope Clement VII, opposed by the English-backed pope of Rome, Pope Urban VI.

With Charles VI mentally ill, from 1393, his wife Isabeau of Bavaria presided over a regency counsel, on which sat the grandees of the kingdom. The uncle of Charles VI, Philip the Bold, Duke of Burgundy, who acted as regent during the king's minority (from 1380 to 1388), was a great influence on the queen (he had organized the royal marriage during his regency). This influence progressively shifted to Louis I, Duke of Orléans, the king's brother, and it was suspected, the queen's lover.[1] On the death of Philip the Bold, his son John the Fearless (who was less linked to Isabeau) again lost influence at court. The other uncle of Charles VI, John, Duke of Berry, served as a mediator between the Orléans party (what would become the Armagnacs) and the Burgundy party, whose rivalry would increase bit by bit and in the end, result in a true civil war.

To oppose the territorial expansion of the Dukedom of Burgundy, the Duke of Orléans acquired Luxembourg in 1402. While Louis of Orléans, getting 90% of his income from the royal treasury, bought lands and strongholds in the eastern marches of the kingdom that the Burgundians considered their private hunting ground, John the Fearless (lacking the fiery prestige of his father) saw royal largess towards him drying up (Philip received 200,000 livres per year, but John had to satisfy himself with 37,000).

The Duke of Orléans, son-in-law of Gian Galeazzo Visconti and holding the title for more or less hypothetical fiefdoms in the peninsula, wanted to let Charles VI intervene militarily in his favor. What is more, it seems he wanted to let the Anglo-French truce break down, even so far as provoking Henry IV of England to a duel, which John the Fearless could not allow, since Flemish industry depended totally on imported English wool and would have been ruined by an embargo on English goods.

The quarrel at first respected all forms of courtesy: John the Fearless adopted the nettle as his emblem, whilst Louis of Orléans chose the gnarled stick and the duke of Burgundy the plane or rabot[clarification needed] (distributing "rabotures", or badges, to his supporters).[1]

Outbreak of the war

The king's brother, Louis of Orléans, "who whinnied like a stallion after almost all the beautiful women",[attribution needed] was accused of having wanted to seduce or worse, "esforcier", Margaret of Bavaria, the duchess of Burgundy. Moreover, and even if it was only a rumor, this seducer was – as Burgundian propaganda ran – the queen's lover and the real father of Charles, the future Charles VII. Louis was certainly close to the queen and benefited from the benevolence of his brother the king, whenever he was out of crisis; he thus succeeded in ousting the Burgundians on the counsel.

Ousted from power and toyed with by Louis, this was too much for John the Fearless. Taking advantage of rising anger among the taxpayers, always under pressure in peacetime, and noting that their taxes serve to finance court festivities,[2] John began to campaign for support, financing demagoguery (promising, for example, tax cuts and state reforms, that is, a controlled monarchy).[2] He thus won over the merchants, the small people and the university.[2]

John threatened Paris in 1405 with a demonstration of his power, but even this did not prove sufficient to restore his influence. He thus decided to get rid of his exasperating rival, having him murdered on rue Vieille du Temple in Paris on 23 November 1407, whilst he was leaving the queen's residence at Hôtel Barbette, a few days after she had given birth to her twelfth child.[1] Thomas de Courteheuse then sent word to Louis that the king, Charles VI of France, urgently needed him at hôtel Saint-Paul. Leaving the Hôtel Barbette, Louis was stabbed by fifteen masked criminals[1] led by Raoulet d'Anquetonville, a servant of the Duke of Burgundy.[3] Louis's escort of valets and guards were powerless to protect him. John had the support of Paris's population and university, whom he had won over by promising the establishment of an ordinance like that of 1357.[4] Thus able to take power, he could thus also publicly acknowledge the assassination – far from hiding it, he publicized it in an elegy in praise of tyrannicide by the Sorbonne university theologian Jean Petit.[3] The assassination thus finally unleashed a civil war that would last almost 30 years.

Civil war

This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2008) |

Intending to avenge his father, Charles of Orléans (Louis's son) backed the enemies of the Dukes of Burgundy wherever he could but even so, in 1409, a peace concluded at Chartres seemed to bring an end to hostilities. However, on 15 April 1410, at the marriage of Charles and Bonne d'Armagnac at Gien, the Duke of Orléans, his new father-in-law and the grandees of France formed a league against John and his supporters. The marriage gave the Orléans faction a new head to replace Louis (Charles's new father-in-law, Bernard VII, Count of Armagnac, who became the natural protector of the Duke) and a new name (the Armagnac party). Other members of the league included the Dukes of Berry, Bourbon and Brittany, as well as the Counts of Clermont and Alençon.

Bernard VII recruited warbands in the Midi that fought with unheard-of ferocity: the Écorcheurs. At their head, he ravaged the vicinity of Paris and advanced into the Saint-Marcel suburb. A new treaty, signed at Bicêtre on 2 November 1410, suspended hostilities, but both sides had taken up arms again as early as spring 1411. In October 1411, with an army 60,000 strong, the Duke of Burgundy entered Paris and attacked the Bretons allied to the Armagnacs, who had retrenched at La Chapelle. He had to withdraw in the end but, in the night of 8 to 9 November, he left via the porte Saint-Jacques, marched across Saint-Cloud and decisively defeated the Écorcheurs. Then John the Fearless pursued the princes of Orléans and their allies to Bourges, which Orléans was besieging, but the royal army appeared in front of the city on 11 June 1412. Another peace was signed at Bourges on 15 July and confirmed at Auxerre on 22 August.

The English took advantage of the situation by punctually supporting the two parties or buying their neutrality. The Armagnacs concluded a treaty with Henry IV of England in 1412, to prevent an Anglo-Burgundian alliance, so they yielded Guyenne to him and recognized his suzerainty over Poitou, Angoulême and Périgord. All the same, John the Fearless managed the English well, since an English wool embargo could ruin the cloth merchants of Flanders.

In 1413, John the Fearless supported the Cabochien Revolt[1] that brought about a slaughter in Paris. The Parisian population, terrified, called on the Armagnacs for aid. Their troops retook the city in 1414. When Henry V of England renewed hostilities in 1415, the duke of Burgundy remained neutral, leaving Henry able to defeat the French army (essentially provided by the Armagnacs), at the battle of Agincourt in October 1415.

On May 29, 1418, thanks to the treason of a certain Perrinet Leclerc and the support of the craftsmen and university, Paris was delivered to Jean de Villiers de L'Isle-Adam, captain of a troop favouring the duke of Burgundy. On the following 12 June, Bernard VII and other Armagnacs were slaughtered by a mob. John thus became master of Paris once again, and so he entered into negotiations with the English in which he seemed willing to welcome the king of England's claim on the French throne. It thus became imperative for the Dauphin to negotiate a rapprochement with the Burgundians, again to avoid an Anglo-Burgundian alliance. John the Fearless, on his part, had become master of a large part of the kingdom after his capture of Paris, but his finances were at rock bottom. John was thus in favor of meeting the Dauphin, Charles VII of France, in order to sign up to an advantageous peace, so several meetings were thus organized.

Assassination of John the Fearless

However, having set the precedent for assassinations, on 10 September 1419, John himself was murdered on the bridge at Montereau-Fault-Yonne, whilst in the town for an interview with Charles. Both sides agreed to meet on the bridge. Charles's men accused the Burgundians of not keeping their promise to break off their alliances with the English. They, on high alert because they had heard that Jean intended to kidnap or attack the dauphin, reacted swiftly when the Lord of Navailles raised his sword. In the ensuing scuffle, the duke was killed.[5] This act prevented all appeasement, and thereby enabled a continuation of English military successes with the collusion of Burgundy.

Aftermath

Philip the Good, the new Duke of Burgundy, then entered into an alliance with the English, which resulted in the Treaty of Troyes. This treaty disinherited the Dauphin Charles and handed the succession to Henry V through a marriage to Charles VI's daughter, Catherine of Valois. The treaty named Henry "regent and heir of France" (although the English only had effective control over northern France and Guyenne) until Charles's death. The treaty was denounced by the Armagnacs, who reasoned "that the king belongs to the crown and not vice versa". Despite his expectations, Henry V predeceased his sickly father-in-law by a few months, in 1422. In 1429, the intervention of Joan of Arc culminated in a successful coronation campaign that allowed Charles VII to be crowned at Reims Cathedral, the traditional coronation site of French kings, on 17 July 1429. The ten-year-old Henry VI of England was crowned as King of France on 16 December 1431 at Notre-Dame de Paris.

End of the war

Engaged in a patient reconquest of French territory, Charles VII wished to isolate the English from the Burgundians. In 1435, he concluded the treaty of Arras with Philip the Good, ending the civil war. Philip the Good was personally exempted from rendering homage to Charles VII (for having been complicit in his father's murder). This agreement officially put an end to the war and allowed Charles VII to recapture practically all the English continental possessions, leaving them in 1453 with Calais alone. Philip the Good later secured the release of Charles, Duke of Orléans, ending the feud between the two houses.

See also

Notes

- Walravens, C.J.H. (1971). Alain Chartier. Amsterdam: Meulenhoff-Didier. p. 166.

References

- Bertrand Schnerb, Les Armagnacs et les Bourguignons. La maudite guerre, Paris, 1988.

- Jacques d'Avout, La Querelle des Armagnacs et des Bourguignons, 431 pages, Paris, Librairie Gallimard Editeur, 1943

- Nicolas Offenstadt, « Armagnacs et Bourguignons. L’affreuse discorde », L’Histoire, 311, July–August 2006, n° spécial La guerre civile, pp. 24–27.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Armagnac%E2%80%93Burgundian_Civil_War

John of Horne (1380–1436)

This article relies largely or entirely on a single source. (August 2018) |

John of Horne (Dutch: Jan van Hoorn; French: Jean de Hornes; c. 1380 – 22 August 1436), lord of Baucignies,[1] was an Admiral of Flanders.

He was a son of Arnold of Horne and Joanna of Hondschoote. From his father he inherited the Lordships of Baucigny, Montcornet, Heeze and Leende. From his mother he inherited the Lordships Hondschoote, Houtkerque, Lokeren, Veurne and Sint-Winoksbergen. He also obtained Gaasbeek in 1434.

John of Horne was Seneschal of Brabant and Grand Chamberlain of both John the Fearless and Philip the Good. In 1420 he was knighted during the siege of Melun. He also became keeper of Castle Loevestein after the abdication of Jacqueline, Countess of Hainaut.

John of Horne is best known for his role in the 1436 Siege of Calais. Philip the Good besieged the English-held city and as Admiral of Flanders, it was John's task to block the harbor of Calais. He sank 5 to 6 ships laden with stone in the harbor entrance, but the people of Calais were able to approach these wrecks during low tide and dismantled them. Furthermore, John was forced to return his fleet to Holland because of bad weather. His failure to block the harbor contributed to the overall failure of the siege.

After the siege, Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester led an expeditionary army into Flanders and English pirates plundered the Flemish coast. Unable to stop these English raids, John of Horne was held accountable by the Flemish people and he was lynched in the dunes near Ostend.

John married Margareth de la Tremouille in 1410, and they had one son, Philip (1421).

References

- Vaughan, Richard (2004). Philip the Good (reprinted new ed.). Boydell Press. p. 101. ISBN 978-0-85115-917-1.

- Flemish nobility

- 1436 deaths

- Burgundian knights

- Medieval admirals

- Burgundian faction

- People of the Hundred Years' War

- Government advisors

- Philip the Good (Duke of Burgundy)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_of_Horne_(1380%E2%80%931436)

Burgundian War may refer to:

- Burgundian Wars (1474-77)

- Cologne Diocesan Feud (1473-80)

- Armagnac–Burgundian Civil War (1407-35)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Burgundian_War

| Burgundian Wars | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

The battle of Morat, from Diebold Schilling's Berne Chronicle | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

The Burgundian Wars (1474–1477) were a conflict between the Burgundian State and the Old Swiss Confederacy and its allies. Open war broke out in 1474, and the Duke of Burgundy, Charles the Bold, was defeated three times on the battlefield in the following years and was killed at the Battle of Nancy in 1477. The Duchy of Burgundy and several other Burgundian lands then became part of France, and the Burgundian Netherlands and Franche-Comté were inherited by Charles's daughter, Mary of Burgundy, and eventually passed to the House of Habsburg upon her death because of her marriage to Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor.

Background

The dukes of Burgundy had succeeded, over a period of about 100 years, in establishing their rule as a strong force between the Holy Roman Empire and France. The consolidation of regional principalities with varying wealth into the Burgundian State brought great economic opportunity and wealth to the new power. A deciding factor for many elites in consolidating their lands was the relatively safe guarantee of making a profit under the economically stable Duchy of Burgundy.[1] Their possessions included, besides their original territories of the Franche-Comté and the Duchy of Burgundy, the economically-strong regions of Flanders and Brabant as well as Luxembourg.

The dukes of Burgundy generally pursued aggressive expansionist politics, especially in Alsace and Lorraine, seeking to unite their northern and southern possessions geographically.[2] Having already been in conflict with the French king, Burgundy had sided with the English in the Hundred Years' War but then the Yorkists in the Wars of the Roses, when Henry VI sided with France. The conflict had left the regional powers of France and England in a weakened state and allowed for the rise of the Burgundian power, alongside its fierce French rivals.[3] The repercussions of the Black Death also continued to affect Europe and assisted in maintaining a diminished society. According to some historians, the extremely profitable region of the Low Countries supplied the Duchy of Burgundy with sufficient funds to support their ambitions internally but especially externally.[4] In this period of expansion, treaties of trade and peace were signed with Swiss cantons, and would benefit the security of each power against Habsburg and French ambitions.[5] Charles's advances along the Rhine brought him into conflict with the Habsburgs, especially Emperor Frederick III.

The results of war began to appear east of Burgundy, which pressed its influence over its Swiss neighbors. The Swiss Confederation had been in frequent conflict with the Ottomans for decades[citation needed] and led up in the 1470s to papal calls for a crusade against the Ottomans. The idea of the "German nation" (German: teutshe nation) was used as a unifying force.[citation needed] According to a Cambridge publication on Swiss history, both the Swiss and the Burgundians had made aggression a significant impact on the region's foreign affairs. In the effort of consolidating the Swiss Confederacy and for independence from Habsburg rule, Swiss forces gained control of the Habsburg town of Thurgau in an effort to expand its borders and influence.[6] The Bernese people were more frequently being attacked by Charles the Bold's Lombard mercenaries. That raised concern to the Bernese as they began to call on their Swiss allies for assistance in the conflict with Burgundy. The aggressive actions of Charles the Bold would eventually culminate in the Swiss giving him the nickname, "the Turk in the West", and make Burgundy as fierce a rival as the Ottomans in the East.

Conflict

Initially in 1469, Duke Sigismund of Habsburg of Austria pawned his possessions in the Alsace in the Treaty of Saint-Omer as a fiefdom to the Duke of Burgundy for a loan or sum of 50,000 florins, as well as an alliance with Charles the Bold, to have them better protected from the expansion of the Eidgenossen (the Old Swiss Confederacy).[7] Charles's involvement west of the Rhine gave him no reason to attack the confederates, as Sigismund had wanted, but his embargo politics against the cities of Basel, Strasbourg and Mulhouse, directed by his reeve Peter von Hagenbach, prompted them to turn to Bern for help. Charles's expansionist strategy suffered a first setback in his politics when his attack on the Archbishopric of Cologne failed after the unsuccessful Siege of Neuss (1474–75).

In the conflict's second phase, Sigismund sought to achieve a peace agreement with the Swiss confederates, which eventually was concluded in Konstanz in 1474 (later called the Ewige Richtung or Perpetual Accord). He wanted to buy back his Alsace possessions from Charles, who refused. Shortly afterwards, von Hagenbach was captured and executed by decapitation in Alsace, and the Swiss, united with the Alsace cities and Sigismund of Habsburg in an anti-Burgundian league, conquered part of the Burgundian Jura (Franche-Comté) by winning the Battle of Héricourt in November 1474. King Louis XI of France joined the coalition by the Treaty of Andernach in December.[8] The next year, Bernese forces conquered and ravaged Vaud, which belonged to the Duchy of Savoy, which was allied with Charles the Bold. Bern had called out to its Swiss allies for expansion into the Vaud region of Savoy to prevent future aggression by Charles near Bernese lands that were geographically closer to Burgundy than those of the rest of the Swiss Confederation. However, the other Swiss cities had become displeased at the ever-growing expansionist and aggressive Bernese foreign policy and so initially did not support Bern. The Confederacy was a collective defense agreement between the Swiss members and ensured that if one city were attacked, the others would come to its aid. Because the military actions by Bern in Savoy were an invasion, the other Confederacy allies had no legal obligation to come to the aid of the Bernese.

In the Valais, the independent republics of the Sieben Zenden, with the help of Bernese and other confederate forces, drove the Savoyards out of the lower Valais after a victory in the Battle on the Planta in November 1475. In 1476, Charles retaliated and marched to Grandson, which belonged to Pierre de Romont of Savoy but had recently been taken by the Swiss. There, he had the capitulated garrison hanged or drowned in the lake.[7] When the confederate forces arrived a few days later, Charles was defeated in the Battle of Grandson and was forced to flee the battlefield, leaving behind his artillery and many provisions and valuables. Having rallied his army, he was dealt a devastating blow by the confederates at the Battle of Morat. As Burgundian losses continued, Charles the Bold lost the support of his lords, who were losing men and profit, and a rebellion soon began, led by René II, Duke of Lorraine. As the revolt continued, René used his land's strategic location between northern and southern Burgundy to cut off communication and to disrupt war capabilities.[9] The internal conflict only made the war with the Swiss more difficult and pulled Charles's attention away from the Confederacy to deal with the more pressing matter of René's revolt. Charles the Bold raised a new army but fell during the Battle of Nancy in 1477 in which the Swiss fought alongside an army of René. The military failures of Charles the Bold are summarized by a common contemporary Swiss quote: "Charles the Bold lost his goods at Grandson, his bravery at Morat and his blood at Nancy."

Near the end of 1476, the Swiss Confederacy began receiving orders from Pope Sixtus IV, who called for an end of the war and the signing of peace between the Swiss and Charles.[10] Although that seemed to be a peaceful resolution to the war, the Pope's aspirations for Charles to divert his attention away from the Swiss and onto the Muslims in a crusade began to show. The papal pressure was eventually ignored by the Swiss, who refused to end the war unless Charles left the Duchy of Lorraine, whose lands were controlled by René II. It is evident through contemporary writings that espionage and censorship played an influential role in both Swiss and Burgundian actions throughout the war. Professional spies were hired by both sides to recover information of enemy movements and weak points. However, this profession proved to be extremely lethal, as some Swiss cities suffered heavy losses, and obtaining information of the opposing side continued to be a difficult task throughout the war.[11]

The Burgundian Wars also assisted in the shift of military strategy across Europe after the Swiss victories over the numerically-superior Burgundians. The Gewalthaufen proved to be an effective Swiss military strategy against the superior Burgundian forces. Until that point, battles had been dominated by cavalry, which could easily overpower infantry troops on the battlefield. However, the Gewalthaufen tactic used long spears to counter cavalry with remarkable success. That marked a key shift in military history and tipped the balance in favour of infantry troops over mounted soldiers.[5]

Aftermath

The results of the conflict would prove to have significant repercussions for the future of the Duchy of Burgundy and for the regional stability of Western Europe. With the death of Charles the Bold, the Valois dynasty of the dukes of Burgundy died out, and widespread revolts engulfed the Duchy, which soon collapsed under those pressures. The northern territories of the dukes of Burgundy became a possession of the Habsburgs when Archduke Maximilian of Austria, who would later become Holy Roman Emperor, married Charles's only daughter, Mary of Burgundy. The duchy proper reverted to the crown of France under King Louis XI. The Franche-Comté initially also became French but was ceded to Maximilian's son Philip in 1493 by Charles VIII at the Treaty of Senlis in an attempt to bribe the emperor to remain neutral during Charles's planned invasion of Italy.

The victories of the Eidgenossen (Swiss Confederation) over what was one of the most powerful military forces in Europe gained it a reputation of being nearly invincible, and the Burgundian Wars marked the beginning of the rise of Swiss mercenaries on the battlefields of Europe.[5] Although Bern and other Swiss cities invaded and controlled large swathes of Savoyard territories, the Confederacy maintained only Grandson, Morat and Echallens as notable cities. Inside the Confederacy itself, however, the outcome of the war led to internal conflict since the city cantons insisted on having the lion's share of the proceeds as they had supplied the most troops. The country cantons resented that, and the Dreizehn Orte disputes almost led to war. They were settled by the Stanser Verkommnis of 1481.

See also

Further reading

- Vaughan, Richard (1973), Charles the Bold: The Last Valois Duke of Burgundy, London: Longman Group, ISBN 0-582-50251-9.

- Deuchler, Florens (1963), Die Burgunderbeute: Inventar der Beutestücke aus den Schlachten von Grandson, Murten und Nancy 1476/1477 (in German), Bern: Verlag Stämpfli & Cie.

References

- Curry, Anne (2011). Journal of Medieval Military History. Rochester: The Boydell Press. pp. 76–131. ISBN 978-1-84383-668-1.

External links

- Burgundian Wars in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- Franche-Comté in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Burgundian_Wars

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pope

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antipope

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Western_Schism

Burgundy became a major center for musical development during the Renaissance era. Among the dances Burgundy has produced is the elegant, energetic basse danse and the bransle which was associated with the lower-classes in the Middle Ages while the upper-class likely danced pavanes and galliards. Modern Burgundy is home to music festivals like the Ainey International Music Festival.

The Burgundian School was a group of composers active in the 15th century in what is now eastern France, Belgium, and the Netherlands, centered on the court of the Dukes of Burgundy. The main names associated with this school are Guillaume Dufay, Gilles Binchois, and Antoine Busnois. For a time in the early 15th century, the court of Burgundy was the musical center of gravity of Europe, eclipsing even Rome, the seat of the Papacy, and Avignon, the home of the Antipopes. By late in the 15th century the Burgundian style was subsumed into the larger stream of Franco-Flemish music.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Music_of_Burgundy

| Part of a series on |

| Medieval music |

|---|

| Overview |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

John Dunstaple (or Dunstable, c. 1390 – 24 December 1453) was an English composer whose music helped inaugurate the transition from the medieval to the Renaissance periods.[1] The central proponent of the Contenance angloise style (lit. 'English manner'), Dunstaple was the leading English composer of his time, and is often coupled with William Byrd and Henry Purcell as England's most important early music composers.[2] His surviving music is exclusively vocal, and frequently uses isorhythms, while pioneering the prominent use of harmonies with thirds and sixths. His style would have an immense influence on the subsequent music of continental Europe, inspiring composers such as Du Fay, Binchois, Ockeghem and Busnois.[2]

Information on Dunstaple's life is largely non-existent or speculative,[3] with the only certain date of his activity being his death on Christmas Eve of 1453. Probably born in Dunstable in Bedfordshire during the late 14th-century, Dunstaple was associated with Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester and Joan of Navarre, and, through them, St Albans Abbey. Another important patron was John, Duke of Bedford, with whom Dunstaple may have travelled to France.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Dunstaple

The Capetian house of Valois[a] (UK: /ˈvælwɑː/ VAL-wah, also US: /vælˈwɑː, vɑːlˈwɑː/ va(h)l-WAH,[1] French: [valwa]) was a cadet branch of the Capetian dynasty. They succeeded the House of Capet (or "Direct Capetians") to the French throne, and were the royal house of France from 1328 to 1589. Junior members of the family founded cadet branches in Orléans, Anjou, Burgundy, and Alençon.

The Valois descended from Charles, Count of Valois (1270–1325), the second surviving son of King Philip III of France (reigned 1270–1285). Their title to the throne was based on a precedent in 1316 (later retroactively attributed to the Merovingian Salic law) which excluded females (Joan II of Navarre), as well as male descendants through the distaff side (Edward III of England), from the succession to the French throne.

After holding the throne for several centuries the Valois male line became extinct and the House of Bourbon succeeded the Valois to the throne as the senior-surviving branch of the Capetian dynasty.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/House_of_Valois

| Charles the Bold | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Charles in about 1460, wearing the collar of the Order of the Golden Fleece, painted by Rogier van der Weyden, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin | |||||

| Duke of Burgundy | |||||

| Reign | 15 June 1467 – 5 January 1477 | ||||

| Predecessor | Philip the Good | ||||

| Successor | Mary the Rich | ||||

| Born | 10 November 1433 Dijon, Burgundy | ||||

| Died | 5 January 1477 (aged 43) Nancy, Lorraine | ||||

| Burial | |||||

| Spouses |

| ||||

| Issue | Mary the Rich | ||||

| |||||

| House | Valois-Burgundy | ||||

| Father | Philip the Good | ||||

| Mother | Isabella of Portugal | ||||

| Religion | Roman Catholicism | ||||

| Signature | |||||

Charles I (Charles Martin; German: Karl Martin; Dutch: Karel Maarten; 10 November 1433 – 5 January 1477), nicknamed the Bold[1] (German: der Kühne; Dutch: de Stoute; French: le Téméraire), was Duke of Burgundy from 1467 to 1477.

Charles's main objective was to be crowned king by turning the growing Burgundian State into a territorially continuous kingdom. He declared himself and his lands independent, bought Upper Alsace and conquered Zutphen, Guelders and Lorraine, uniting at last Burgundian northern and southern possessions. This caused the enmity of several European powers and triggered the Burgundian Wars.

Charles's early death at the Battle of Nancy at the hands of Swiss mercenaries fighting for René II, Duke of Lorraine, was of great consequence in European history. The Burgundian domains, long wedged between the Kingdom of France and the Habsburg Empire, were divided, but the precise disposition of the vast and disparate territorial possessions involved was disputed among the European powers for centuries.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_the_Bold

In the 14th century, the main centers of musical activity were northern France, Avignon, and Italy, as represented by Guillaume de Machaut and the ars nova, the ars subtilior, and Landini respectively; Avignon had a brief but important cultural flowering because it was the location of the Papacy during the Western Schism. When France was ravaged by the Hundred Years' War (1337–1453), the cultural center migrated farther east, to towns in Burgundy and the Low Countries, known then collectively as the Netherlands.[1]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Burgundian_School