English Renaissance theatre

| Reformation era literature |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

English Renaissance theatre, also known as Renaissance English theatre and Elizabethan theatre, refers to the theatre of England between 1558 and 1642.

This is the style of the plays of William Shakespeare, Christopher Marlowe and Ben Jonson.

Background

The term English Renaissance theatre encompasses the period between 1562—following a performance of Gorboduc, the first English play using blank verse, at the Inner Temple during the Christmas season of 1561—and the ban on theatrical plays enacted by the English Parliament in 1642. In a strict sense "Elizabethan" only refers to the period of Queen Elizabeth's reign (1558–1603). English Renaissance theatre may be said to encompass Elizabethan theatre from 1562 to 1603, Jacobean theatre from 1603 to 1625, and Caroline theatre from 1625 to 1642.

Along with the economics of the profession, the character of the drama changed towards the end of the period. Under Elizabeth, the drama was a unified expression as far as social class was concerned: the Court watched the same plays the commoners saw in the public playhouses. With the development of the private theatres, drama became more oriented towards the tastes and values of an upper-class audience. By the later part of the reign of Charles I, few new plays were being written for the public theatres, which sustained themselves on the accumulated works of the previous decades.[1]

Sites of dramatic performance

Grammar schools

The English grammar schools, like those on the continent, placed special emphasis on the trivium: grammar, logic, and rhetoric. Though rhetorical instruction was intended as preparation for careers in civil service such as law, the rhetorical canons of memory (memoria) and delivery (pronuntiatio), gesture and voice, as well as exercises from the progymnasmata, such as the prosopopoeia, taught theatrical skills.[2][3] Students would typically analyse Latin and Greek texts, write their own compositions, memorise them, and then perform them in front of their instructor and their peers.[4] Records show that in addition to this weekly performance, students would perform plays on holidays,[5] and in both Latin and English.[6]

Choir schools

Choir schools connected with the Elizabethan court included St. George’s Chapel, the Chapel Royal, and St. Paul’s.[7] These schools performed plays and other court entertainments for the Queen.[8] Between the 1560s and 1570s these schools had begun to perform for general audiences as well.[9] Playing companies of boy actors were derived from choir schools.[10] John Lyly is an earlier example of a playwright contracted to write for the children's companies; Lyly wrote Gallathea, Endymion, and Midas for Paul’s Boys.[11] Another example is Ben Jonson, who wrote Cynthia’s Revels.[12]

Universities

Academic drama stems from late medieval and early modern practices of miracles and morality plays as well as the Feast of Fools and the election of a Lord of Misrule.[13] The Feast of Fools includes mummer plays.[14] The universities, particularly Oxford and Cambridge, were attended by students studying for bachelor's degrees and master's degrees, followed by doctorates in Law, Medicine, and Theology.[15] In the 1400s, dramas were often restricted to mummer plays with someone who read out all the parts in Latin.[16] With the rediscovery and redistribution of classical materials during the English Renaissance, Latin and Greek plays began to be restaged.[17] These plays were often accompanied by feasts.[18] Queen Elizabeth I viewed dramas during her visits to Oxford and Cambridge.[19] A well-known play cycle which was written and performed in the universities was the Parnassus Plays.[13]

Inns of Court

Upon graduation, many university students, especially those going into law, would reside and participate in the Inns of Court. The Inns of Court were communities of working lawyers and university alumni.[20] Notable literary figures and playwrights who resided in the Inns of Court include John Donne, Francis Beaumont, John Marston, Thomas Lodge, Thomas Campion, Abraham Fraunce, Sir Philip Sidney, Sir Thomas More, Sir Francis Bacon, and George Gascoigne.[21][22] Like the university, the Inns of Court elected their own Lord of Misrule.[23] Other activities included participation in moot court, disputation, and masques.[23][22] Plays written and performed in the Inns of Court include Gorboduc, Gismund of Salerne, and The Misfortunes of Arthur.[22] An example of a famous masque put on by the Inns was James Shirley's The Triumph of Peace. Shakespeare's The Comedy of Errors and Twelfth Night were also performed here, although written for commercial theater.[24]

Masque

Establishment of playhouses

The first permanent English theatre, the Red Lion, opened in 1567[25] but it was a short-lived failure. The first successful theatres, such as The Theatre, opened in 1576.

The establishment of large and profitable public theatres was an essential enabling factor in the success of English Renaissance drama. Once they were in operation, drama could become a fixed and permanent, rather than transitory, phenomenon. Their construction was prompted when the Mayor and Corporation of London first banned plays in 1572 as a measure against the plague, and then formally expelled all players from the city in 1575.[26] This prompted the construction of permanent playhouses outside the jurisdiction of London, in the liberties of Halliwell/Holywell in Shoreditch and later the Clink, and at Newington Butts near the established entertainment district of St. George's Fields in rural Surrey.[26] The Theatre was constructed in Shoreditch in 1576 by James Burbage with his brother-in-law John Brayne (the owner of the unsuccessful Red Lion playhouse of 1567)[27] and the Newington Butts playhouse was set up, probably by Jerome Savage, some time between 1575[28] and 1577.[29] The Theatre was rapidly followed by the nearby Curtain Theatre (1577), the Rose (1587), the Swan (1595), the Globe (1599), the Fortune (1600), and the Red Bull (1604).[a]

Playhouse architecture

Archaeological excavations on the foundations of the Rose and the Globe in the late 20th century showed that all the London theatres had individual differences, but their common function necessitated a similar general plan.[30] The public theatres were three stories high and built around an open space at the centre. Usually polygonal in plan to give an overall rounded effect, although the Red Bull and the first Fortune were square. The three levels of inward-facing galleries overlooked the open centre, into which jutted the stage: essentially a platform surrounded on three sides by the audience. The rear side was restricted for the entrances and exits of the actors and seating for the musicians. The upper level behind the stage could be used as a balcony, as in Romeo and Juliet and Antony and Cleopatra, or as a position from which an actor could harangue a crowd, as in Julius Caesar.[31] The pit was the place where the poorest audience members could view the show. Around the 1600s a new area was introduced into the theaters, a 'gullet'. A gullet was an invisible corridor that the actors used to go to the wings of the stage where people usually changed clothes quickly[citation needed].

The playhouses were generally built with timber and plaster. Individual theatre descriptions give additional information about their construction, such as flint stones being used to build the Swan. Theatres were also constructed to be able to hold a large number of people.[32]

A different model was developed with the Blackfriars Theatre, which came into regular use on a long-term basis in 1599.[b] The Blackfriars was small in comparison to the earlier theatres and roofed rather than open to the sky. It resembled a modern theatre in ways that its predecessors did not. Other small enclosed theatres followed, notably the Whitefriars (1608) and the Cockpit (1617). With the building of the Salisbury Court Theatre in 1629 near the site of the defunct Whitefriars, the London audience had six theatres to choose from: three surviving large open-air public theatres—the Globe, the Fortune, and the Red Bull—and three smaller enclosed private theatres: the Blackfriars, the Cockpit, and the Salisbury Court.[c] Audiences of the 1630s benefited from a half-century of vigorous dramaturgical development; the plays of Marlowe and Shakespeare and their contemporaries were still being performed on a regular basis, mostly at the public theatres, while the newest works of the newest playwrights were abundant as well, mainly at the private theatres.[citation needed]

Audiences

Around 1580, when both the Theater and the Curtain were full on summer days, the total theater capacity of London was about 5000 spectators. With the building of new theater facilities and the formation of new companies, London's total theater capacity exceeded 10,000 after 1610.[33]

Ticket prices in general varied during this time period. The cost of admission was based on where in the theatre a person wished to be situated, or based on what a person could afford. If people wanted a better view of the stage or to be more separate from the crowd, they would pay more for their entrance. Due to inflation that occurred during this time period, admission increased in some theaters from a penny to a sixpence or even higher.[34]

Commercial theaters were largely located just outside the boundaries of the City of London, since City authorities tended to be wary of the adult playing companies, but plays were performed by touring companies all over England.[35] English companies even toured and performed English plays abroad, especially in Germany and in Denmark.[36][d]

Upper class spectators would pay for seats in the galleries, using cushions for comfort. In the Globe Theatre, nobles could sit directly by the side on the stage.[38]

Performances

The acting companies functioned on a repertory system: unlike modern productions that can run for months or years on end, the troupes of this era rarely acted the same play two days in a row.[39] Thomas Middleton's A Game at Chess ran for nine straight performances in August 1624 before it was closed by the authorities; but this was due to the political content of the play and was a unique, unprecedented and unrepeatable phenomenon. The 1592 season of Lord Strange's Men at the Rose Theatre was far more representative: between 19 February and 23 June the company played six days a week, minus Good Friday and two other days. They performed 23 different plays, some only once, and their most popular play of the season, The First Part of Hieronimo, based on Kyd's The Spanish Tragedy, 15 times. They never played the same play two days in a row, and rarely the same play twice in a week.[40][e] The workload on the actors, especially the leading performers like Richard Burbage or Edward Alleyn, must have been tremendous.

One distinctive feature of the companies was that they included only males. Female parts were played by adolescent boy players in women's costume. Some companies were composed entirely of boy players.[f] Performances in the public theatres (like the Globe) took place in the afternoon with no artificial lighting, but when, in the course of a play, the light began to fade, candles were lit.[43] In the enclosed private theatres (like the Blackfriars) artificial lighting was used throughout. Plays contained little to no scenery as the scenery was described by the actors or indicated by costume through the course of the play.[44]

In the Elizabethan era, research has been conclusive about how many actors and troupes there were in the 16th century, but little research delves into the roles of the actors on the English renaissance stage. The first point is that during the Elizabethan era, women were not allowed to act on stage. The actors were all male; in fact, most were boys. For plays written that had male and female parts, the female parts were played by the youngest boy players.[45] Stronger female roles in tragedies were acted by older boy players because they had more experience. [45] As a boy player, many skills had to be implemented such as voice and athleticism (fencing was one).[45]

In Elizabethan entertainment, troupes were created and they were considered the actor companies. They travelled around England as drama was the most entertaining art at the time.

Elizabethan actors never played the same show on successive days and added a new play to their repertoire every other week. These actors were getting paid within these troupes so for their job, they would constantly learn new plays as they toured different cities in England. In these plays, there were bookkeepers that acted as the narrators of these plays and they would introduce the actors and the different roles they played. At some points, the bookkeeper would not state the narrative of the scene, so the audience could find out for themselves. In Elizabethan and Jacobean plays, the plays often exceeded the number of characters/roles and did not have enough actors to fulfil them, thus the idea of doubling roles came to be.[46] Doubling roles is used to reinforce a plays theme by having the actor act out the different roles simultaneously.[47] The reason for this was for the acting companies to control salary costs, or to be able to perform under conditions where resources such as other actor companies lending actors were not present.[47]

There were two acting styles implemented: formal and natural. Formal acting is objective and traditional, while natural acting attempts to create an illusion for the audience by remaining in character and imitating the fictional circumstances. The formal actor symbolises while the natural actor interprets. The natural actor impersonates while the formal actor represents the role. Natural and formal are opposites of each other, where natural acting is subjective. Overall, the use of these acting styles and the doubled roles dramatic device made Elizabethan plays very popular.[48]

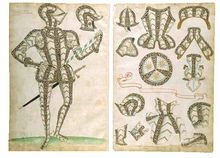

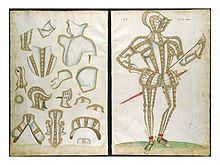

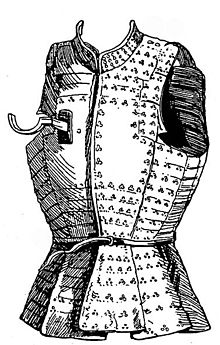

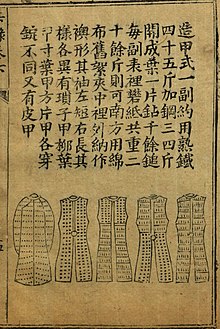

Costumes

One of the main uses of costume during the Elizabethan era was to make up for the lack of scenery, set, and props on stage. It created a visual effect for the audience, and it was an integral part of the overall performance.[49] Since the main visual appeal on stage were the costumes, they were often bright in colour and visually entrancing. Colours symbolized social hierarchy, and costumes were made to reflect that. For example, if a character was royalty, their costume would include purple. The colours, as well as the different fabrics of the costumes, allowed the audience to know the status of each character when they first appeared on stage.[50]

Costumes were collected in inventory. More often than not, costumes wouldn't be made individually to fit the actor. Instead, they would be selected out of the stock that theatre companies would keep. A theatre company reused costumes when possible and would rarely get new costumes made. Costumes themselves were expensive, so usually players wore contemporary clothing regardless of the time period of the play. The most expensive pieces were given to higher class characters because costuming was used to identify social status on stage. The fabrics within a playhouse would indicate the wealth of the company itself. The fabrics used the most were: velvet, satin, silk, cloth-of-gold, lace and ermine.[51] For less significant characters, actors would use their own clothes.

Actors also left clothes in their will for following actors to use. Masters would also leave clothes for servants in their will, but servants weren't allowed to wear fancy clothing, instead, they sold the clothes back to theatre companies.[50] In the Tudor and Elizabethan eras, there were laws stating that certain classes could only wear clothing fitting of their status in society. There was a discrimination of status within the classes. Higher classes flaunted their wealth and power through the appearance of clothing, however, courtesans and actors were the only exceptions – as clothing represented their 'working capital', as it were, but they were only permitted to dress so while working. If actors belonged to a licensed acting company, they were allowed to dress above their standing in society for specific roles in a production.[52]

Playwrights

The growing population of London, the growing wealth of its people, and their fondness for spectacle produced a dramatic literature of remarkable variety, quality and extent. Although most of the plays written for the Elizabethan stage have been lost, over 600 remain.

The people who wrote these plays were primarily self-made men from modest backgrounds.[g] Some of them were educated at either Oxford or Cambridge, but many were not. Although William Shakespeare and Ben Jonson were actors, the majority do not seem to have been performers, and no major author who came on to the scene after 1600 is known to have supplemented his income by acting. Their lives were subject to the same levels of danger and earlier mortality as all who lived during the early modern period: Christopher Marlowe was killed in an apparent tavern brawl, while Ben Jonson killed an actor in a duel. Several were probably soldiers.

Playwrights were normally paid in increments during the writing process, and if their play was accepted, they would also receive the proceeds from one day's performance. However, they had no ownership of the plays they wrote. Once a play was sold to a company, the company owned it, and the playwright had no control over casting, performance, revision or publication.

The profession of dramatist was challenging and far from lucrative.[54] Entries in Philip Henslowe's Diary show that in the years around 1600 Henslowe paid as little as £6 or £7 per play. This was probably at the low end of the range, though even the best writers could not demand too much more. A playwright, working alone, could generally produce two plays a year at most. In the 1630s Richard Brome signed a contract with the Salisbury Court Theatre to supply three plays a year, but found himself unable to meet the workload. Shakespeare produced fewer than 40 solo plays in a career that spanned more than two decades: he was financially successful because he was an actor and, most importantly, a shareholder in the company for which he acted and in the theatres they used. Ben Jonson achieved success as a purveyor of Court masques, and was talented at playing the patronage game that was an important part of the social and economic life of the era. Those who were purely playwrights fared far less well: the biographies of early figures like George Peele and Robert Greene, and later ones like Brome and Philip Massinger, are marked by financial uncertainty, struggle and poverty.

Playwrights dealt with the natural limitation on their productivity by combining into teams of two, three, four, and even five to generate play texts. The majority of plays written in this era were collaborations, and the solo artists who generally eschewed collaborative efforts, like Jonson and Shakespeare, were the exceptions to the rule. Dividing the work, of course, meant dividing the income; but the arrangement seems to have functioned well enough to have made it worthwhile. Of the 70-plus known works in the canon of Thomas Dekker, roughly 50 are collaborations. In a single year (1598) Dekker worked on 16 collaborations for impresario Philip Henslowe, and earned £30, or a little under 12 shillings per week—roughly twice as much as the average artisan's income of 1s. per day.[55] At the end of his career, Thomas Heywood would famously claim to have had "an entire hand, or at least a main finger" in the authorship of some 220 plays. A solo artist usually needed months to write a play (though Jonson is said to have done Volpone in five weeks); Henslowe's Diary indicates that a team of four or five writers could produce a play in as little as two weeks. Admittedly, though, the Diary also shows that teams of Henslowe's house dramatists—Anthony Munday, Robert Wilson, Richard Hathwaye, Henry Chettle, and the others, even including a young John Webster—could start a project, and accept advances on it, yet fail to produce anything stageworthy.[56]

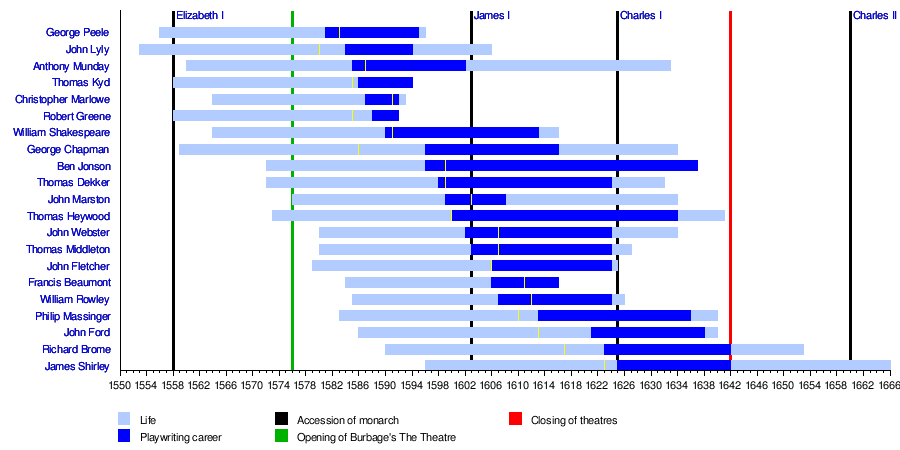

Timeline of English Renaissance playwrights

Short yellow lines indicate 27 years—the average age these authors began their playwrighting careers

Genres

Genres of the period included the history play, which depicted English or European history. Shakespeare's plays about the lives of kings, such as Richard III and Henry V, belong to this category, as do Christopher Marlowe's Edward II and George Peele's Famous Chronicle of King Edward the First. History plays also dealt with more recent events, like A Larum for London which dramatizes the sack of Antwerp in 1576. A better known play, Peele's The Battle of Alcazar (c. 1591), depicts the battle of Alcácer Quibir in 1578.

Tragedy was a very popular genre. Marlowe's tragedies were exceptionally successful, such as Dr. Faustus and The Jew of Malta. The audiences particularly liked revenge dramas, such as Thomas Kyd's The Spanish Tragedy. The four tragedies considered to be Shakespeare's greatest (Hamlet, Othello, King Lear and Macbeth) were composed during this period.

Comedies were common, too. A subgenre developed in this period was the city comedy, which deals satirically with life in London after the fashion of Roman New Comedy. Examples are Thomas Dekker's The Shoemaker's Holiday and Thomas Middleton's A Chaste Maid in Cheapside.

Though marginalised, the older genres like pastoral (The Faithful Shepherdess, 1608), and even the morality play (Four Plays in One, ca. 1608–13) could exert influences. After about 1610, the new hybrid subgenre of the tragicomedy enjoyed an efflorescence, as did the masque throughout the reigns of the first two Stuart kings, James I and Charles I.

Plays on biblical themes were common, Peele's David and Bethsabe being one of the few surviving examples.

Printed texts

Only a minority of the plays of English Renaissance theatre were ever printed. Of Heywood's 220 plays, only about 20 were published in book form.[57] A little over 600 plays were published in the period as a whole, most commonly in individual quarto editions. (Larger collected editions, like those of Shakespeare's, Ben Jonson's, and Beaumont and Fletcher's plays, were a late and limited development.) Through much of the modern era, it was thought that play texts were popular items among Renaissance readers that provided healthy profits for the stationers who printed and sold them. By the turn of the 21st century, the climate of scholarly opinion shifted somewhat on this belief: some contemporary researchers argue that publishing plays was a risky and marginal business[58]—though this conclusion has been disputed by others.[59] Some of the most successful publishers of the English Renaissance, like William Ponsonby or Edward Blount, rarely published plays.

A small number of plays from the era survived not in printed texts but in manuscript form.[h]

The end of English Renaissance theatre

The rising Puritan movement was hostile toward theatre, as they felt that "entertainment" was sinful. Politically, playwrights and actors were clients of the monarchy and aristocracy, and most supported the Royalist cause. The Puritan faction, long powerful in London, gained control of the city early in the First English Civil War, and on 2 September 1642, the Long Parliament, pushed by the Parliamentarian party, under Puritan influence, banned the staging of plays in the London theatres though it did not, contrary to what is commonly stated, order the closure, let alone the destruction, of the theatres themselves:

Whereas the distressed Estate of Ireland, steeped in her own Blood, and the distracted Estate of England, threatened with a Cloud of Blood by a Civil War, call for all possible Means to appease and avert the Wrath of God, appearing in these Judgements; among which, Fasting and Prayer, having been often tried to be very effectual, having been lately and are still enjoined; and whereas Public Sports do not well agree with Public Calamities, nor Public Stage-plays with the Seasons of Humiliation, this being an Exercise of sad and pious Solemnity, and the other being Spectacles of Pleasure, too commonly expressing lascivious Mirth and Levity: It is therefore thought fit, and Ordained, by the Lords and Commons in this Parliament assembled, That, while these sad causes and set Times of Humiliation do continue, Public Stage Plays shall cease, and be forborn, instead of which are recommended to the People of this Land the profitable and seasonable considerations of Repentance, Reconciliation, and Peace with God, which probably may produce outward Peace and Prosperity, and bring again Times of Joy and Gladness to these Nations.

— His Majesty's Stationery Office, Acts and Ordinances of the Interregnum, 1642–1660, "September 1642: Order for Stage-plays to cease"[60]

The Act purports the ban to be temporary ("... while these sad causes and set Times of Humiliation do continue, Public Stage Plays shall cease and be forborn") but does not assign a time limit to it.

Even after 1642, during the English Civil War and the ensuing Interregnum (English Commonwealth), some English Renaissance theatre continued. For example, short comical plays called drolls were allowed by the authorities, while full-length plays were banned. The theatre buildings were not closed but rather were used for purposes other than staging plays.[i]

The performance of plays remained banned for most of the next eighteen years, becoming allowed again after the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660. The theatres began performing many of the plays of the previous era, though often in adapted forms. New genres of Restoration comedy and spectacle soon evolved, giving English theatre of the later seventeenth century its distinctive character.

List of playwrights

- William Alabaster[61]

- William Alexander, Earl of Stirling

- Robert Armin

- Barnabe Barnes

- Lording Barry

- Francis Beaumont

- William Berkeley

- Samuel Brandon

- Antony Brewer

- Richard Brome

- Samuel Brooke

- William Browne (poet)

- Thomas Campion

- Lodowick Carlell

- William Cartwright

- Elizabeth Cary, Lady Falkland

- Robert Cecil, Earl of Salisbury

- George Chapman

- Henry Cheke

- Henry Chettle

- John Clavell

- Anthony Chute

- Robert Daborne

- Samuel Daniel

- William Davenant

- Robert Davenport

- John Davidson

- John Day

- Thomas Dekker

- Michael Drayton

- Richard Edwardes

- George Ferebe

- Nathan Field

- John Fletcher

- Phineas Fletcher

- John Ford

- Abraham Fraunce

- Ulpian Fulwell

- William Gager

- George Gascoigne

- Henry Glapthorne

- Thomas Goffe

- Arthur Golding

- Robert Greene

- Fulke Greville

- Matthew Gwinne

- William Haughton

- Walter Hawkesworth

- Mary Herbert (writer)

- Thomas Heywood

- Thomas Hughes

- Thomas Ingelend

- John Jeffere

- Ben Jonson

- Henry Killigrew

- Thomas Killigrew

- Thomas Kyd

- Sir Henry Lee

- Thomas Legge

- Thomas Lodge

- Thomas Lupton

- John Lyly

- Lewis Machin

- Francis Marbury

- Gervase Markham

- Christopher Marlowe

- Shackerley Marmion

- John Marston

- John Mason

- Philip Massinger

- Thomas May

- Thomas Middleton

- Anthony Munday

- Thomas Nabbes

- Thomas Nashe

- Thomas Nelson

- Thomas Norton

- George Peele

- William Percy

- John Phillip

- John Pickering (dramatist)

- Henry Porter

- Thomas Preston

- Samuel Rowley

- William Rowley

- George Ruggle

- Joseph Rutter

- Thomas Sackville

- William Sampson

- William Shakespeare

- Edward Sharpham

- James Shirley

- Sir Philip Sidney

- Wentworth Smith

- John Stephens

- Sir John Suckling

- Robert Tailor

- Richard Tarlton

- Thomas Tomkis

- Cyril Tourneur

- Francis Verney

- William Wager

- George Wapull

- William Warner (poet)

- John Webster

- George Whetstone

- George Wilkins

- Robert Wilmot

- Arthur Wilson

- Robert Wilson

- Nathaniel Woodes

- Robert Yarington

Actors

- William Alabaster

- Edward Alleyn

- Robert Armin

- William Barksted

- Richard Brome

- Richard Burbage

- William Cavendish

- Henry Condell

- Nathan Field

- Alexander Gough

- Thomas Greene

- Richard Gunnell

- Stephen Hammerton

- Charles Hart

- John Heminges

- Thomas Heywood

- John Honyman

- Ben Jonson

- Will Kempe

- John Lowin

- William Ostler

- Andrew Pennycuicke

- Augustine Phillips

- Thomas Pollard

- Thomas Pope

- Timothy Read

- Richard Robinson

- Samuel Rowley

- William Rowley

- William Shakespeare

- William Sly

- Robert Wilson

Playhouses

Playing companies

- King's Revels Children

- King's Revels Men

- Lady Elizabeth's Men

- Leicester's Men

- Lord Strange's Men (later Derby's Men)

- Oxford's Boys

- Oxford's Men

- Pembroke's Men

- Prince Charles's Men

- Queen Anne's Men

- Queen Elizabeth's Men

- Queen Henrietta's Men

- The Admiral's Men

- The Children of Paul's

- The Children of the Chapel (Queen's Revels)

- The King's Men

- The Lord Chamberlain's Men

- Sussex's Men

- Warwick's Men

- Worcester's Men

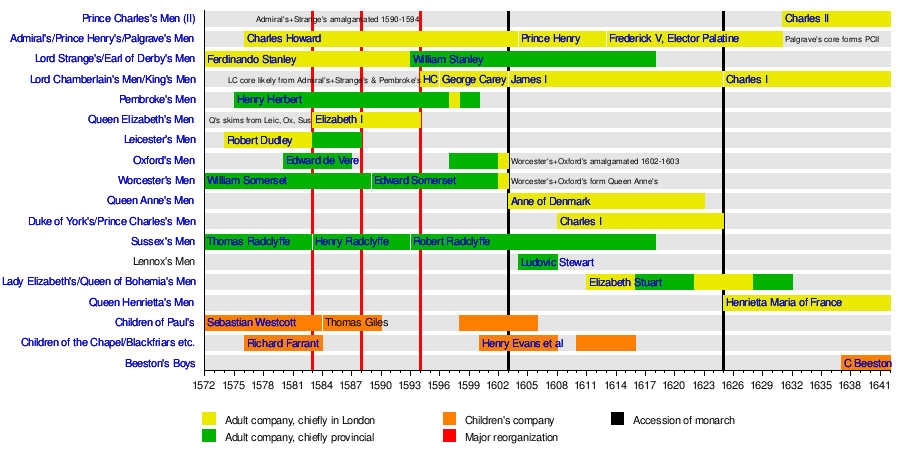

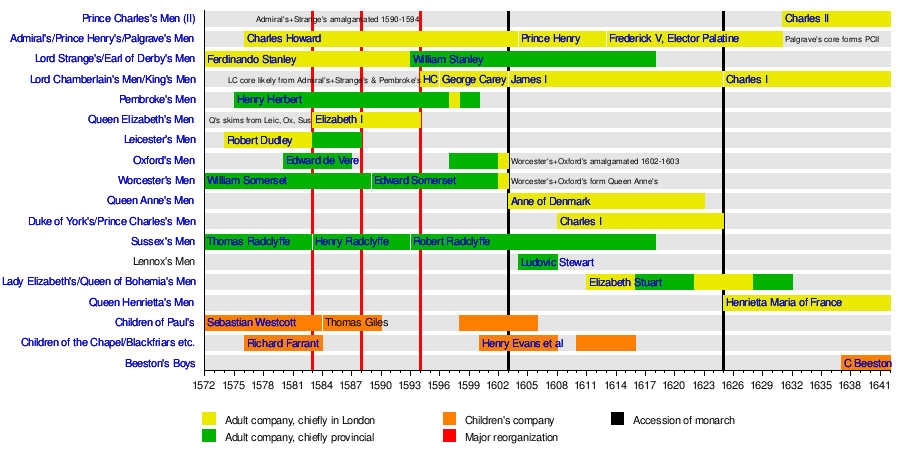

Timeline of English Renaissance playing companies

English Renaissance playing company timeline

This timeline charts the existence of major English playing companies from 1572 ("Acte for the punishment of Vacabondes", which legally restricted acting to players with a patron of sufficient degree) to 1642 (the closing of the theatres by Parliament). A variety of strolling players, and even early London-based troupes existed before 1572. The situations were often fluid, and much of this history is obscure; this timeline necessarily implies more precision than exists in some cases. The labels down the left indicate the most common names for the companies. The bar segments indicate the specific patron. In the case of children's companies (a distinct legal situation) some founders are noted.

Other significant figures

- Susan Baskervile, investor and litigant

- William Beeston, manager

- George Buc, Master of the Revels 1609–1622

- Cuthbert Burbage, entrepreneur

- James Burbage, entrepreneur

- Ralph Crane, scribe

- Philip Henslowe, entrepreneur

- Henry Herbert, Master of the Revels 1623–1673

- Edward Knight, prompter

- Francis Langley, entrepreneur

- John Rhodes, manager

- Edmund Tilney, Master of the Revels 1579–1609

See also

Notes and references

Notes

- See for example the Red Bull Theatre and Robert Cox

References

All references to Shakespeare's plays, unless otherwise specified, are taken from the Folger Shakespeare Library's Folger Digital Editions texts edited by Barbara Mowat, Paul Werstine, Michael Poston, and Rebecca Niles. Under their referencing system, 3.1.55 means act 3, scene 1, line 55. Prologues, epilogues, scene directions, and other parts of the play that are not a part of character speech in a scene, are referenced using Folger Through Line Number: a separate line numbering scheme that includes every line of text in the play.

- CITEREFChambers1923

Sources

- Astington, John H. (2010). Actors and Acting in Shakespeare's Time: The Art of Stage Playing. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511761379. ISBN 9780511761379 – via Cambridge Core.

- Bellinger, Martha Fletcher (1927). A Short History of the Drama. New York: Henry Holt and Company. hdl:2027/mdp.39015008227087. OL 17749089M.

- Blayney, Peter W. M. (1997). "The Publication of Playbooks". In Cox, John D.; Kastan, David Scott (eds.). A New History of Early English Drama. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 383–422. ISBN 9780231102438.

- Boas, Frederick S. (1914). University Drama in the Tudor Age. Oxford: Clarendon Press. hdl:2027/mdp.39015030766243. OL 7149074M.

- Bowsher, Julian; Miller, Pat (2010). The Rose and the Globe: Playhouses of Shakespeare's Bankside, Southwark: Excavations 1988–91. Museum of London Archaeology. ISBN 978-1-901992-85-4.

- Bryson, Bill (2008). Shakespeare: The World as a Stage. HarperPerennial. p. 78. ISBN 978-0007197903.

- Calore, Michela (2003). "Elizabethan Plots: A Shared Code of Theatrical and Fictional Language". Theatre Survey. Cambridge University Press. 44 (2): 249–261. doi:10.1017/S0040557403000127. eISSN 1475-4533. ISSN 0040-5574. S2CID 162509372 – via Cambridge Core.

- Chambers, E.K. (2009) [first published 1923]. The Elizabethan Stage. Vol. 3. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199567508.

- Christiansen, Nancy L. (1997). "Rhetoric as Character-Fashioning: The Implications of Delivery's 'Places' in the British Renaissance Paideia". Rhetorica: A Journal of the History of Rhetoric. International Society for the History of Rhetoric. 15 (3): 297–334. doi:10.1525/rh.1997.15.3.297. eISSN 1533-8541. ISSN 0734-8584. JSTOR 10.1525/rh.1997.15.3.297. S2CID 170122602.

- Cook, Ann Jennalie (2014). The Privileged Playgoers of Shakespeare's London, 1576-1642. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691614953.

- Cunningham, Karen J. (2007). "'So Many Books, So Many Rolls of Ancient Time': The Inns of Court and Gorboduc". In Kezar, Dennis (ed.). Solon and Thespis: Law and Theater in the English Renaissance. Notre Dame, Indiana: University of Notre Dame Press. pp. 197–217. ISBN 978-0-268-03313-2.

- Dawson, Anthony B. (2002). "International Shakespeare". In Wells, Stanley; Stanton, Sarah (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare on Stage. Cambridge Companions to Shakespeare. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 174–193. doi:10.1017/CCOL0521792959.010. ISBN 9780511999574 – via Cambridge Core.

- Farmer, Alan B.; Lesser, Zachary (2005). "The Popularity of Playbooks Revisited". Shakespeare Quarterly. Folger Shakespeare Library. 56 (1): 1–32. doi:10.1353/shq.2005.0043. eISSN 1538-3555. ISSN 0037-3222. JSTOR 3844024. S2CID 59134858.

- Firth, C.H.; Rait, R.S., eds. (1911). "September 1642: Order for Stage-plays to cease". Acts and Ordinances of the Interregnum, 1642-1660. Laws, etc. London: His Majesty's Stationery Office. hdl:2027/inu.30000046036137. OL 6559925M.

- Gurr, Andrew (2009). The Shakespearean Stage 1574–1642 (4th ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511819520. ISBN 9780511819520 – via Cambridge Core.

- Halliday, F.E. (1964). A Shakespeare Companion 1564–1964. Baltimore: Penguin. OCLC 683393. OL 5906173M.

- Hattaway, Michael (2008). Elizabethan Popular Theatre: Plays in Performance. London: Routledge. ISBN 9780415489010.

- Ingram, William (1992). The Business of Playing: The Beginnings of The Adult Professional Theater in Elizabethan London. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-2671-1.

- Ichikawa, Mariko (2012). The Shakespearean Stage Space. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139097192. ISBN 9781139097192 – via Cambridge Core.

- Keenan, Siobhan (2002). Travelling Players in Shakespeare's England. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1057/9780230597549. ISBN 978-0-333-96820-8.

- Keenan, Siobhan (2014). Acting Companies and their Plays in Shakespeare's London. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. doi:10.5040/9781472575692. ISBN 9781408146637.

- Kregor, Karl H. (1993). "Doubled Roles in English Renaissance Drama: Problems, Possibilities and Marlowe's Edward II". Theatre History Studies. University of Alabama Press. 13. ISSN 0733-2033.

- MacIntyre, Jean (1992). Costumes and Scripts in the Elizabethan Theatres. Edmonton: University of Alberta Press. ISBN 978-0-88864-226-4.

- Maclennan, Ian Burns (1994). "If I were a woman": A study of the boy player in the Elizabethan public theatre (PhD thesis).

- Mann, David Albert (1991). The Elizabethan Player: Contemporary Stage Representation. Routledge Library Editions. Routledge. ISBN 9781138235656.

- Montrose, Louis (1996). The Purpose of Playing: Shakespeare and the Cultural Politics of the Elizabethan Theatre. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226534831.

- Ordish, T. Fairman (1899). Early London Theatres: In the Fields. Antiquary's library. London: Elliot Stock. hdl:2027/hvd.hnnr4j. OL 16796098M.

- Triesault, Jon Lloyd (1970). Elizabethan public playhouse acting: Its development and complex style (MA thesis). University of Southern California.

- Wickham, Glynne; Berry, Herbert; Ingram, William (2000). English professional theatre, 1530-1660. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-23012-4.

External links

- Early Modern Drama database

- Shakespeare and the Globe from Encyclopædia Britannica; a more comprehensive resource on the theatre of this period than its name suggests.

- A Lecture on Elizabethan Theatre by Thomas Larque

- A site discussing the influence of Ancient Rome on English Renaissance Theatre

- Richard Southern archive at the University of Bristol Theatre Collection, University of Bristol

- Roy, Pinaki. "All the World's a Stage: Remembering the Prominent Renaissance London Playhouses". Yearly Shakespeare (ISSN 0976-9536), 11 (April 2013): 24–32.

- Roy, Pinaki. " If we ever meet again: The Three Groups of English Renaissance Playwrights". Yearly Shakespeare (ISSN 0976-9536), 17 (April 2019): 31–38.

- The Francis Longe Collection at the Library of Congress contains some early editions of theatrical works published in English between 1607 and 1812.

- [1]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/English_Renaissance_theatre

Sites of dramatic performance

Grammar schools

The English grammar schools, like those on the continent, placed special emphasis on the trivium: grammar, logic, and rhetoric. Though rhetorical instruction was intended as preparation for careers in civil service such as law, the rhetorical canons of memory (memoria) and delivery (pronuntiatio), gesture and voice, as well as exercises from the progymnasmata, such as the prosopopoeia, taught theatrical skills.[2][3] Students would typically analyse Latin and Greek texts, write their own compositions, memorise them, and then perform them in front of their instructor and their peers.[4] Records show that in addition to this weekly performance, students would perform plays on holidays,[5] and in both Latin and English.[6]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/English_Renaissance_theatre

A prosopopoeia (Greek: προσωποποιία, /prɒsoʊpoʊˈpiːə/) is a rhetorical device in which a speaker or writer communicates to the audience by speaking as another person or object. The term literally derives from the Greek roots prósopon "face, person", and poiéin "to make, to do".

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prosopopoeia

Progymnasmata (Greek προγυμνάσματα "fore-exercises"; Latin praeexercitamina) are a series of preliminary rhetorical exercises that began in ancient Greece and continued during the Roman Empire. These exercises were implemented by students of rhetoric, who began their schooling between ages twelve and fifteen. The purpose of these exercises was to prepare students for writing declamations after they had completed their education with the grammarians. There are only four surviving handbooks of progymnasmata, attributed to Aelius Theon, Hermogenes of Tarsus, Aphthonius of Antioch, and Nicolaus the Sophist.[1]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Progymnasmata

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Rhetoric |

|---|

| Five canons |

Pronuntiatio was the discipline of delivering speeches in Western classical rhetoric. It is one of the five canons of classical rhetoric (the others being inventio, dispositio, elocutio, and memoria) that concern the crafting and delivery of speeches. In literature the equivalent of ancient pronuntiatio is the recitation of epics (Aris. Po. 26.2.).[1]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pronuntiatio

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Rhetoric |

|---|

| Five canons |

Memoria was the term for aspects involving memory in Western classical rhetoric. The word is Latin, and can be translated as "memory".

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Memoria

This article has an unclear citation style. (January 2020) |

| Part of a series on |

| Linguistics |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Rhetoric |

|---|

| Five canons |

Rhetoric (/ˈrɛtərɪk/)[note 1] is the art of persuasion, which along with grammar and logic (or dialectic), is one of the three ancient arts of discourse. Rhetoric aims to study the techniques writers or speakers utilize to inform, persuade, or motivate particular audiences in specific situations.[5] Aristotle defines rhetoric as "the faculty of observing in any given case the available means of persuasion" and since mastery of the art was necessary for victory in a case at law, for passage of proposals in the assembly, or for fame as a speaker in civic ceremonies, he calls it "a combination of the science of logic and of the ethical branch of politics".[6] Rhetoric typically provides heuristics for understanding, discovering, and developing arguments for particular situations, such as Aristotle's three persuasive audience appeals: logos, pathos, and ethos. The five canons of rhetoric or phases of developing a persuasive speech were first codified in classical Rome: invention, arrangement, style, memory, and delivery.

From Ancient Greece to the late 19th century, rhetoric played a central role in Western education in training orators, lawyers, counsellors, historians, statesmen, and poets.[7][note 2]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rhetoric

The trivium is the lower division of the seven liberal arts and comprises grammar, logic, and rhetoric.[1]

The trivium is implicit in De nuptiis Philologiae et Mercurii ("On the Marriage of Philology and Mercury") by Martianus Capella, but the term was not used until the Carolingian Renaissance, when it was coined in imitation of the earlier quadrivium.[2] Grammar, logic, and rhetoric were essential to a classical education, as explained in Plato's dialogues. The three subjects together were denoted by the word trivium during the Middle Ages, but the tradition of first learning those three subjects was established in ancient Greece. Contemporary iterations have taken various forms, including those found in certain British and American universities (some being part of the Classical education movement) and at the independent Oundle School in the United Kingdom.[3]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trivium

The Honourable Society of the Inner Temple, commonly known as the Inner Temple, is one of the four Inns of Court and is a professional association for barristers and judges. To be called to the Bar and practise as a barrister in England and Wales, a person must belong to one of these Inns. It is located in the wider Temple area, near the Royal Courts of Justice, and within the City of London. As a liberty, it functions largely as an independent local government authority.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Inner_Temple

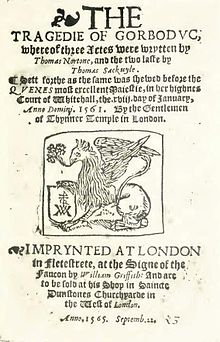

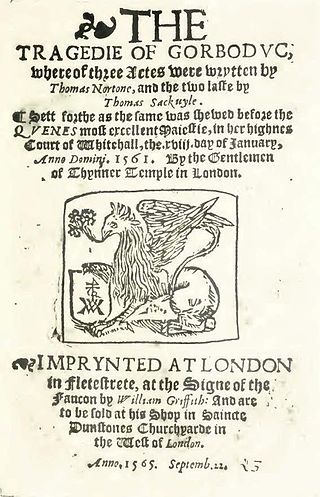

The Tragedie of Gorboduc, also titled Ferrex and Porrex, is an English play from 1561. It was first performed at the Christmas celebration given by the Inner Temple in 1561, and performed at Whitehall before Queen Elizabeth I on 18 January 1561,[1] by the Gentlemen of the Inner Temple.[2] The authors were Thomas Norton and Thomas Sackville, said to be responsible for the first three Acts, and the final two, respectively.

The first quarto, published by the bookseller William Griffith, was published 22 September 1565.[3] A second authorized quarto corrected by the authors followed in 1570, and was printed by John Day with the title The Tragedie of Ferrex and Porrex. A third edition was published in 1590 by Edward Allde.[4]

The play is notable for several reasons: as the first verse drama in English to employ blank verse; for its political subject matter (the realm of Gorboduc is disputed by his sons Ferrex and Porrex), which was still a touchy area in the early years of Elizabeth's reign, while the succession to the throne was unclear; for its manner, progressing from the models of the morality play and Senecan tragedy in the direction which would be followed by later playwrights. That is, it can be seen as a forerunner of the whole trend that would later produce Titus Andronicus[5] and King Lear. It also provides the first well-documented performance of a play in Ireland: Charles Blount, 8th Baron Mountjoy staged it at Dublin Castle in 1601.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gorboduc_(play)

The Tragedie of Gorboduc, also titled Ferrex and Porrex, is an English play from 1561. It was first performed at the Christmas celebration given by the Inner Temple in 1561, and performed at Whitehall before Queen Elizabeth I on 18 January 1561,[1] by the Gentlemen of the Inner Temple.[2] The authors were Thomas Norton and Thomas Sackville, said to be responsible for the first three Acts, and the final two, respectively.

The first quarto, published by the bookseller William Griffith, was published 22 September 1565.[3] A second authorized quarto corrected by the authors followed in 1570, and was printed by John Day with the title The Tragedie of Ferrex and Porrex. A third edition was published in 1590 by Edward Allde.[4]

The play is notable for several reasons: as the first verse drama in English to employ blank verse; for its political subject matter (the realm of Gorboduc is disputed by his sons Ferrex and Porrex), which was still a touchy area in the early years of Elizabeth's reign, while the succession to the throne was unclear; for its manner, progressing from the models of the morality play and Senecan tragedy in the direction which would be followed by later playwrights. That is, it can be seen as a forerunner of the whole trend that would later produce Titus Andronicus[5] and King Lear. It also provides the first well-documented performance of a play in Ireland: Charles Blount, 8th Baron Mountjoy staged it at Dublin Castle in 1601.

Synopsis

The playtext summarizes the plot in the 'Argument': "Gorboduc, King of Britain, divided his realm in his lifetime to his sons, Ferrex and Porrex. The sons fell to dissension. The younger killed the elder. The mother that more dearly loved the elder, for revenge killed the younger. The people, moved with the cruelty of the fact, rose in rebellion and slew both father and mother. The nobility assembled and most terribly destroyed the rebels. And afterward, for want of issue of the prince, whereby the succession of the crown became uncertain, they fell to civil war in which both they and many of their issues were slain, and the land for a long time almost desolate and miserably wasted."

Gorboduc announces his plan to divide his kingdom between his sons Ferrex and Porrex. His councillors advise against it, reminding him of the conflict that arose between the cousins Morgan and Cunedag when Britain was divided between them, which led to Morgan's death. Gorboduc appreciates their advice but goes ahead with his plan. Ferrex is advised by the parasite Hermon to take the whole Kingdom. Tyndar tells Porrex that his brother is making plans for war, meaning Porrex decides to invade Ferrex's realm. Dordan writes to Gorboduc of this. Gorboduc bewails this and is advised to raise a force against them. However, a nuntius (messenger) then enters, bearing the news of Ferrex's death. Porrex meets his father and justifies his actions, saying that he was content to rule his kingdom but that his brother plotted to take his lands. However, his mother Videna then stabs him dead while he is sleeping in revenge for Ferrex. The people rise up in anger and kill both her and Gorboduc, blaming the King for Porrex's death. The nobles prepare to act against the rebels. However, the succession is left uncertain. Fergus, Duke of Albany, plans to gain the throne and begins raising an army while his friends try to gather support. The nobles defeat the rebels, but hear that Fergus has raised an army and intends to take the crown. The nobles oppose Fergus, thinking of him as a foreign invader. Arostus says that Parliament must decide upon a new King. Eubulus bemoans the chaos that has happened to the country and says that Parliament should have been called while the King was alive, but that justice will eventually prevail.

Characters

- Gorboduc, King of Great Britain

- Videna, Queen and wife to King Gorboduc

- Ferrex, Elder Son to King Gorboduc

- Porrex, Younger Son to King Gorboduc

- Clotyn, Duke of Cornewall

- Fergus, Duke of Albany

- Mandud, Duke of Leagre

- Gwenard, Duke of Cumberland

- Eubulus, Secretary to the king Gorboduc

- Arostus, A Counsellour of king Gorboduc

- Dordan, A Counsellour assigned by the king to his Eldest Son Ferrex

- Philander, A Counsellour assigned by the king to his younger Son Porrex

- Hermon, A Parasite of Ferrex and Fergus's slave

- Tyndar, A Parasite of Porrex

- Nuntius, A Messenger of Ferrex's death

- Nuntius, A Messenger of Duke Fergus rising

- Marcella, A Lady of the Queen's privy Chamber

- Chorus, Four ancient and sage men of Britain

References

- Carroll, James D. (2004) "Gorboduc and Titus Andronicus", Notes and Queries, 51: 267-9.

External links

- The Tragedie of Gorboduc (1565) original black-letter edition.

- Gorboduc or Ferrex and Porrex, a tragedy, by T. Norton and T. Sackville, ed. by L.T. Smith (1883)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gorboduc_(play)

Blank verse is poetry written with regular metrical but unrhymed lines, almost always in iambic pentameter.[1] It has been described as "probably the most common and influential form that English poetry has taken since the 16th century",[2] and Paul Fussell has estimated that "about three quarters of all English poetry is in blank verse".[3]

The first known use of blank verse in English was by Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey in his translation of the Aeneid (composed c. 1540; published posthumously, 1554–1557[4]). He may have been inspired by the Latin original since classical Latin verse did not use rhyme, or possibly he was inspired by Ancient Greek verse or the Italian verse form of versi sciolti, both of which also did not use rhyme.

The play Arden of Faversham (around 1590 by an unknown author) is a notable example of end-stopped blank verse.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blank_verse

Not to be confused with free verse.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blank_verse

Universities

Academic drama stems from late medieval and early modern practices of miracles and morality plays as well as the Feast of Fools and the election of a Lord of Misrule.[13] The Feast of Fools includes mummer plays.[14] The universities, particularly Oxford and Cambridge, were attended by students studying for bachelor's degrees and master's degrees, followed by doctorates in Law, Medicine, and Theology.[15] In the 1400s, dramas were often restricted to mummer plays with someone who read out all the parts in Latin.[16] With the rediscovery and redistribution of classical materials during the English Renaissance, Latin and Greek plays began to be restaged.[17] These plays were often accompanied by feasts.[18] Queen Elizabeth I viewed dramas during her visits to Oxford and Cambridge.[19] A well-known play cycle which was written and performed in the universities was the Parnassus Plays.[13]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/English_Renaissance_theatre

The Parnassus plays are three satiric comedies, or full-length academic dramas each divided into five acts. They date from between 1598 and 1602.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Parnassus_plays

https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Parnassus_Plays&redirect=no

The English Renaissance was a cultural and artistic movement in England from the early 16th century to the early 17th century.[1] It is associated with the pan-European Renaissance that is usually regarded as beginning in Italy in the late 14th century. As in most of the rest of northern Europe, England saw little of these developments until more than a century later within the Northern Renaissance. Renaissance style and ideas were slow to penetrate England, and the Elizabethan era in the second half of the 16th century is usually regarded as the height of the English Renaissance. Many scholars see its beginnings in the early 16th century during the reign of Henry VIII.[2]

The English Renaissance is different from the Italian Renaissance in several ways. The dominant art forms of the English Renaissance were literature and music. Visual arts in the English Renaissance were much less significant than in the Italian Renaissance. The English period began far later than the Italian, which was moving into Mannerism and the Baroque by the 1550s or earlier.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/English_Renaissance

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Feast_of_Fools

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lord_of_Misrule

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mummers%27_play

The early modern period of modern history spans the period after the Late Middle Ages of the post-classical era (c. 1400–1500) to the beginning of the Age of Revolutions (c. 1800). Although the chronological limits of this period are open to debate, the timeframe is variously demarcated by historians as beginning with the fall of Constantinople in 1453, the Renaissance period in Europe and Timurid Central Asia,the end of the Crusades, the Age of Discovery (especially the voyages of Christopher Columbus beginning in 1492 but also Vasco da Gama's discovery of the sea route to India in 1498), and ending around the French Revolution in 1789, or Napoleon's rise to power.[1][2]

Historians in recent decades have argued that from a worldwide standpoint, the most important feature of the early modern period was its spreading globalizing character.[3] New economies and institutions emerged, becoming more sophisticated and globally articulated over the course of the period. The early modern period also included the rise of the dominance of mercantilism as an economic theory. Other notable trends of the period include the development of experimental science, increasingly rapid technological progress, secularized civic politics, accelerated travel due to improvements in mapping and ship design, and the emergence of nation states.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Early_modern_period

Western/Central Europe: Eastern Europe:

The Late Middle Ages, or late medieval period, was the period of European history lasting from AD 1300 to 1500. The Late Middle Ages followed the High Middle Ages and preceded the onset of the early modern period (and in much of Europe, the Renaissance).[1]

Around 1300, centuries of prosperity and growth in Europe came to a halt. A series of famines and plagues, including the Great Famine of 1315–1317 and the Black Death, reduced the population to around half of what it had been before the calamities.[2] Along with depopulation came social unrest and endemic warfare. France and England experienced serious peasant uprisings, such as the Jacquerie and the Peasants' Revolt, as well as over a century of intermittent conflict, the Hundred Years' War. To add to the many problems of the period, the unity of the Catholic Church was temporarily shattered by the Western Schism. Collectively, those events are sometimes called the Crisis of the Late Middle Ages.[3]

Despite the crises, the 14th century was also a time of great progress in the arts and sciences. Following a renewed interest in ancient Greek and Roman texts that took root in the High Middle Ages, the Italian Renaissance began. The absorption of Latin texts had started before the Renaissance of the 12th century through contact with Arabs during the Crusades, but the availability of important Greek texts accelerated with the Fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks, when many Byzantine scholars had to seek refuge in the West, particularly Italy.[4]

Combined with this influx of classical ideas was the invention of printing, which facilitated dissemination of the printed word and democratized learning. Those two things would later lead to the Reformation. Toward the end of the period, the Age of Discovery began. The expansion of the Ottoman Empire cut off trading possibilities with the East. Europeans were forced to seek new trading routes, leading to the Spanish expedition under Christopher Columbus to the Americas in 1492 and Vasco da Gama's voyage to Africa and India in 1498. Their discoveries strengthened the economy and power of European nations.

The changes brought about by these developments have led many scholars to view this period as the end of the Middle Ages and the beginning of modern history and of early modern Europe. However, the division is somewhat artificial, since ancient learning was never entirely absent from European society.[citation needed] As a result, there was developmental continuity between the ancient age (via classical antiquity) and the modern age.[citation needed] Some historians, particularly in Italy, prefer not to speak of the Late Middle Ages at all but rather see the high period of the Middle Ages transitioning to the Renaissance and the modern era.[citation needed]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Late_Middle_Ages

Academic drama refers to a theatrical movement that emerged in the mid 16th century during the Renaissance. Dedicated to the study of classical dramas for the purpose of higher education, universities in England began to produce the plays of Sophocles, Euripides, and Seneca the Younger (among others) in the Greek and Roman languages, as well as neoclassical dramas. These classical and neoclassical productions were performed by young scholars at universities in Cambridge and Oxford.[1] Other European countries, such as Spain and Italy adapted classical plays into a mixture of Latin and vernacular dramas. These Spanish and Italian adaptations were used in teaching morals in schools and colleges.[2] The intellectual development of dramas in schools, universities, and Inns of Court in Europe allowed the emergence of the great playwrights of the late 16th century.[3]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Academic_drama

Midas is an Elizabethan era stage play, a comedy written by John Lyly. It is arguably the most overtly and extensively allegorical of Lyly's allegorical plays.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Midas_(Lyly_play)

Gallathea or Galatea is an Elizabethan era stage play, a comedy by John Lyly. The first record of the play's performance was at Greenwich Palace on New Year's Day, 1588 where it was performed before Queen Elizabeth I and her court by the Children of St Paul's, a troupe of boy actors. At this point in his literary career, Lyly had already achieved success with his prose romance Euphues and was a writer in residence at Blackfriars theatre. The play is set in a village on the Lincolnshire shore of the river Humber and in the neighboring woods. It features a host of characters including Greek deities, nymphs, fairies, and some shepherds.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gallathea

| Old St Paul's Cathedral | |

|---|---|

Digital

reconstruction giving an impression of Old St Paul's during the Middle

Ages. The image is based on a model of the Cathedral in the Museum of London, composited with a modern city background. | |

Old St Paul's on a 1300 map of the City of London | |

| 51°30′49″N 0°5′54″W | |

| Denomination | Church of England |

| Previous denomination | Roman Catholic |

| History | |

| Dedication | Saint Paul |

| Events | Cathedral and canonry destroyed by fire—1087, 1666 |

| Architecture | |

| Previous cathedrals | 3 |

| Style | English Gothic |

| Years built |

|

| Administration | |

| Diocese | London |

| Deanery |

|

| Clergy | |

| Bishop(s) | Bishop of London |

| Dean | Dean of St Paul's |

Building details | |

| |

| Record height | |

|---|---|

| Tallest in the world from the mid-14th century to 1311[I] | |

| Preceded by | Great Pyramid of Giza |

| Surpassed by | Lincoln Cathedral |

Old St Paul's Cathedral was the cathedral of the City of London that, until the Great Fire of 1666, stood on the site of the present St Paul's Cathedral. Built from 1087 to 1314 and dedicated to Saint Paul, the cathedral was perhaps the fourth church at Ludgate Hill.[1]

Work on the cathedral began after a fire in 1087. Work took more than 200 years, and was delayed by another fire in 1135. The church was consecrated in 1240, enlarged in 1256 and again in the early 14th century. At its completion in the mid-14th century, the cathedral was one of the longest churches in the world, had one of the tallest spires and some of the finest stained glass.

The presence of the shrine of Saint Erkenwald made the cathedral a site of pilgrimage.[2] In addition to serving as the seat of the Diocese of London, the building developed a reputation as a social hub, with the nave aisle, "Paul's walk", known as a business centre and a place to hear the gossip on the London grapevine. After the Reformation, the open-air pulpit in the churchyard, St Paul's Cross, became the place for radical evangelical preaching and Protestant bookselling.

The cathedral was already in severe structural decline by the early 17th century. Restoration work begun by Inigo Jones in the 1620s was temporarily halted during the English Civil War (1642–1651). In 1666, further restoration was in progress under Sir Christopher Wren when the cathedral was devastated in the Great Fire of London. At that point, it was demolished, and the present cathedral was built on the site.[3]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Old_St_Paul%27s_Cathedral

| St George's Chapel, Windsor Castle | |

|---|---|

| The King's Free Chapel of the College of St George, Windsor Castle | |

| |

|

| 51°29′01″N 00°36′25″W | |

| Location | Windsor |

|---|---|

| Country | England |

| Denomination | Church of England |

| Previous denomination | Roman Catholicism |

| Churchmanship | High Church |

| Website | stgeorges-windsor |

| History | |

| Status | Chapel |

| Founded | 1475 |

| Dedication | St George |

| Architecture | |

| Functional status | Active |

| Heritage designation | Grade I listed |

| Style | Gothic |

| Years built | 1475 |

| Completed | 1511 |

| Specifications | |

| Capacity | 800 |

| Administration | |

| Diocese | Jurisdiction: Royal Peculiar Location: Oxford |

| Deanery | Dean and Canons of Windsor |

| Clergy | |

| Dean | David Conner |

| Precentor | Martin Poll (Chaplain) |

| Canon(s) | Mark Powell (Steward) |

| Canon Treasurer | Hueston Finlay (Vice-Dean) |

| Laity | |

| Organist/Director of music | James Vivian |

| Music group(s) | Choir of St George's Chapel |

St George's Chapel at Windsor Castle in England is a castle chapel built in the late-medieval Perpendicular Gothic style. It is a Royal Peculiar (a church under the direct jurisdiction of the monarch), and the Chapel of the Order of the Garter. St George's Chapel was founded in the 14th century by King Edward III and extensively enlarged in the late 15th century. It is located in the Lower Ward of the castle.[1] The castle has belonged to the monarchy for almost 1,000 years and was a principal residence of Elizabeth II before her death. The chapel has been the scene of many royal services, weddings and burials – in the 19th century, St George's Chapel and the nearby Frogmore Gardens superseded Westminster Abbey as the chosen burial place for the British royal family.[2] The running of the chapel is the responsibility of the dean and Canons of Windsor who make up the College of Saint George. They are assisted by a clerk, verger and other staff. The Society of the Friends of St George's and Descendants of the Knights of the Garter, a registered charity, was established in 1931 to assist the college in maintaining the chapel.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/St_George%27s_Chapel,_Windsor_Castle

Inns of Court

Upon graduation, many university students, especially those going into law, would reside and participate in the Inns of Court. The Inns of Court were communities of working lawyers and university alumni.[20] Notable literary figures and playwrights who resided in the Inns of Court include John Donne, Francis Beaumont, John Marston, Thomas Lodge, Thomas Campion, Abraham Fraunce, Sir Philip Sidney, Sir Thomas More, Sir Francis Bacon, and George Gascoigne.[21][22] Like the university, the Inns of Court elected their own Lord of Misrule.[23] Other activities included participation in moot court, disputation, and masques.[23][22] Plays written and performed in the Inns of Court include Gorboduc, Gismund of Salerne, and The Misfortunes of Arthur.[22] An example of a famous masque put on by the Inns was James Shirley's The Triumph of Peace. Shakespeare's The Comedy of Errors and Twelfth Night were also performed here, although written for commercial theater.[24]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/English_Renaissance_theatre

In the scholastic system of education of the Middle Ages, disputations (in Latin: disputationes, singular: disputatio) offered a formalized method of debate designed to uncover and establish truths in theology and in sciences. Fixed rules governed the process: they demanded dependence on traditional written authorities and the thorough understanding of each argument on each side.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Disputation

The masque was a form of festive courtly entertainment that flourished in 16th- and early 17th-century Europe, though it was developed earlier in Italy, in forms including the intermedio (a public version of the masque was the pageant). A masque involved music, dancing, singing and acting, within an elaborate stage design, in which the architectural framing and costumes might be designed by a renowned architect, to present a deferential allegory flattering to the patron. Professional actors and musicians were hired for the speaking and singing parts. Masquers who did not speak or sing were often courtiers: the English queen Anne of Denmark frequently danced with her ladies in masques between 1603 and 1611, and Henry VIII and Charles I of England performed in the masques at their courts.[citation needed] In the tradition of masque, Louis XIV of France danced in ballets at Versailles with music by Jean-Baptiste Lully.[1]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Masque

Moot court is a co-curricular activity at many law schools. Participants take part in simulated court or arbitration proceedings, usually involving drafting memorials or memoranda and participating in oral argument. In many countries, the phrase "moot court" may be shortened to simply "moot" or "mooting". Participants are either referred to as "mooters" or, less conventionally, "mooties".

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moot_court

Twelfth Night, or What You Will is a romantic comedy by William Shakespeare, believed to have been written around 1601–1602 as a Twelfth Night's entertainment for the close of the Christmas season. The play centres on the twins Viola and Sebastian, who are separated in a shipwreck. Viola (who is disguised as Cesario) falls in love with the Duke Orsino, who in turn is in love with Countess Olivia. Upon meeting Viola, Countess Olivia falls in love with her thinking she is a man.

The play expanded on the musical interludes and riotous disorder expected of the occasion,[1] with plot elements drawn from the short story "Of Apollonius and Silla" by Barnabe Rich, based on a story by Matteo Bandello. The first documented public performance was on 2 February 1602, at Candlemas, the formal end of Christmastide in the year's calendar. The play was not published until its inclusion in the 1623 First Folio.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Twelfth_Night

The Comedy of Errors is one of William Shakespeare's early plays. It is his shortest and one of his most farcical comedies, with a major part of the humour coming from slapstick and mistaken identity, in addition to puns and word play. It has been adapted for opera, stage, screen and musical theatre numerous times worldwide. In the centuries following its premiere, the play's title has entered the popular English lexicon as an idiom for "an event or series of events made ridiculous by the number of errors that were made throughout".[1]

Set in the Greek city of Ephesus, The Comedy of Errors tells the story of two sets of identical twins who were accidentally separated at birth. Antipholus of Syracuse and his servant, Dromio of Syracuse, arrive in Ephesus, which turns out to be the home of their twin brothers, Antipholus of Ephesus and his servant, Dromio of Ephesus. When the Syracusans encounter the friends and families of their twins, a series of wild mishaps based on mistaken identities lead to wrongful beatings, a near-seduction, the arrest of Antipholus of Ephesus, and false accusations of infidelity, theft, madness, and demonic possession.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Comedy_of_Errors

The Triumph of Peace was a Caroline era masque, "invented and written" by James Shirley, performed on 3 February 1634 and published the same year. The production was designed by Inigo Jones.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Triumph_of_Peace

The Misfortunes of Arthur, Uther Pendragon's son reduced into tragical notes is a play by the 16th-century English dramatist Thomas Hughes. Written in 1587, it was performed at Greenwich before Queen Elizabeth I on February 28, 1588. The play is based on the Arthurian legend, specifically the story of Mordred's treachery and King Arthur's death as told in Geoffrey of Monmouth's Historia Regum Britanniae.

Several of Hughes' fellow members at Gray's Inn participated in The Misfortunes of Arthur’s writing and production for the inn's revels.[1] Nicholas Trotte provided the introduction, Francis Flower the choruses of Acts I and II, William Fulbecke wrote two speeches, while Francis Bacon, Christopher Yelverton, John Lancaster, and Flower oversaw the dumb shows. Lancaster and John Penruddocke directed the drama at Court.[2] The play was greatly influenced by Seneca the Younger's tragedies, and was composed according to the Senecan model.[1] The ghost of Gorlois, a duke slain by Uther Pendragon, opens the play with a speech reproducing passages spoken by Tantalus' ghost in Thyestes. All action occurs offstage and is related by a chorus, while a messenger announces the tragic events. W. J. Cunliffe demonstrated the influence of Seneca on Hughes, suggesting the play consists largely of translations of Seneca with occasional original lines.[3]

The Misfortunes of Arthur was reprinted in John Payne Collier's supplement to Dodsley's Old Plays, and by Harvey Carson Grumline (Berlin, 1900), who points out that Hughes's source was Geoffrey of Monmouth's Historia Regum Britanniae rather than Thomas Malory's Le Morte d'Arthur.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Misfortunes_of_Arthur

Sir Thomas More | |

|---|---|

| |

| Lord Chancellor | |

| In office October 1529 – May 1532 | |

| Monarch | Henry VIII |

| Preceded by | Thomas Wolsey |

| Succeeded by | Thomas Audley |

| Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster | |

| In office 31 December 1525 – 3 November 1529 | |

| Monarch | Henry VIII |

| Preceded by | Richard Wingfield |

| Succeeded by | William FitzWilliam |

| Speaker of the House of Commons | |

| In office 15 April 1523 – 13 August 1523 | |

| Monarch | Henry VIII |

| Preceded by | Thomas Nevill |

| Succeeded by | Thomas Audley |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 7 February 1478 City of London, England |

| Died | 6 July 1535 (aged 57) Tower Hill, London, England |

| Spouses | |

| Children | Margaret, Elizabeth, Cicely, and John |

| Parent(s) | Sir John More Agnes Graunger |

| Education | University of Oxford Lincoln's Inn |

| Signature |  |

Philosophy career | |

| Notable work | Utopia (1516) Responsio ad Lutherum (1523) A Dialogue of Comfort against Tribulation (1553) |

| Era | Renaissance philosophy 16th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy, Catholic |

| School | Christian humanism[1] Renaissance humanism |

Main interests | Social philosophy Criticism of Protestantism |

Notable ideas | Utopia |

Influences | |

Influenced | |

Sir Thomas More (7 February 1478 – 6 July 1535), venerated in the Catholic Church as Saint Thomas More,[7][8] was an English lawyer, judge,[9] social philosopher, author, statesman, and noted Renaissance humanist. He also served Henry VIII as Lord High Chancellor of England from October 1529 to May 1532.[10] He wrote Utopia, published in 1516,[11] which describes the political system of an imaginary island state.

More opposed the Protestant Reformation, directing polemics against the theology of Martin Luther, Huldrych Zwingli, John Calvin and William Tyndale. More also opposed Henry VIII's separation from the Catholic Church, refusing to acknowledge Henry as supreme head of the Church of England and the annulment of his marriage to Catherine of Aragon. After refusing to take the Oath of Supremacy, he was convicted of treason and executed. On his execution, he was reported to have said: "I die the King's good servant, and God's first".

Pope Pius XI canonised More in 1935 as a martyr. Pope John Paul II in 2000 declared him the patron saint of statesmen and politicians.[12][13][14]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_More

Abraham Fraunce (c. 1558/1560 – c. 1592/1593) was an English poet.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abraham_Fraunce

Establishment of playhouses

The first permanent English theatre, the Red Lion, opened in 1567[25] but it was a short-lived failure. The first successful theatres, such as The Theatre, opened in 1576.

The establishment of large and profitable public theatres was an essential enabling factor in the success of English Renaissance drama. Once they were in operation, drama could become a fixed and permanent, rather than transitory, phenomenon. Their construction was prompted when the Mayor and Corporation of London first banned plays in 1572 as a measure against the plague, and then formally expelled all players from the city in 1575.[26] This prompted the construction of permanent playhouses outside the jurisdiction of London, in the liberties of Halliwell/Holywell in Shoreditch and later the Clink, and at Newington Butts near the established entertainment district of St. George's Fields in rural Surrey.[26] The Theatre was constructed in Shoreditch in 1576 by James Burbage with his brother-in-law John Brayne (the owner of the unsuccessful Red Lion playhouse of 1567)[27] and the Newington Butts playhouse was set up, probably by Jerome Savage, some time between 1575[28] and 1577.[29] The Theatre was rapidly followed by the nearby Curtain Theatre (1577), the Rose (1587), the Swan (1595), the Globe (1599), the Fortune (1600), and the Red Bull (1604).[a]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/English_Renaissance_theatre

| Address | Maiden Lane (now Park Street) Southwark[2][3] London England |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 51°30′24″N 00°5′41″W |

| Owner | Lord Chamberlain's Men |

| Type | Elizabethan theatre |

| Construction | |

| Opened | 1599 |

| Closed | 1642 |

| Demolished | 1644–45 |

| Rebuilt | 1614 |

The Globe Theatre was a theatre in London associated with William Shakespeare. It was built in 1599 at Southwark, close to the south bank of the Thames, by Shakespeare's playing company, the Lord Chamberlain's Men. It was destroyed by fire on 29 June 1613. A second Globe Theatre was built on the same site by June 1614 and stayed open until the London theatre closures of 1642. As well as plays by Shakespeare, early works by Ben Jonson, Thomas Dekker and John Fletcher were first performed here.[4]

A modern reconstruction of the Globe, named "Shakespeare's Globe", opened in 1997 approximately 750 feet (230 m) from the site of the original theatre.[5]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Globe_Theatre

The Theatre was an Elizabethan playhouse in Shoreditch (in Curtain Road, part of the modern London Borough of Hackney), just outside the City of London. It was the first permanent theatre ever built in England. It was built in 1576 after the Red Lion, and the first successful one. Built by actor-manager James Burbage, near the family home in Holywell Street, The Theatre is considered the first theatre built in London for the sole purpose of theatrical productions. The Theatre's history includes a number of important acting troupes including the Lord Chamberlain's Men, which employed Shakespeare as actor and playwright. After a dispute with the landlord, the theatre was dismantled and the timbers used in the construction of the Globe Theatre on Bankside.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Theatre

| Address | 86 Stepney Way Whitechapel High Street London Borough of Tower Hamlets |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 51°31′07″N 00°03′25″W |

| Owner | John Brayne |

| Type | Elizabethan playhouse |

| Capacity | standing yard with galleries |

| Construction | |

| Years active | 1567–1568 |

| Architect | William Sylvester and John Reynolds (carpenters) |