In the United States, federal grants are economic aid issued by the United States government out of the general federal revenue. A federal grant is an award of financial assistance from a federal agency to a recipient to carry out a public purpose of support or stimulation authorized by a law of the United States.

Grants are federal assistance to individuals, benefits or entitlements. A grant is not used to acquire property or services for the federal government's direct benefit.

Grants may also be issued by private non-profit organizations such as foundations, not-for-profit corporations or charitable trusts which are all collectively referred to as charities.

Outside the United States grants, subventions or subsidies are used to in similar fashion by government or private charities to subsidize programs and projects that fit within the funding criteria of the grant-giving entity or donor. Grants can be unrestricted, to be used by the recipient in any fashion within the perimeter of the recipient organization's activities or they may be restricted to a specific purpose by the benefactor.

American definition

Federal grants are defined and governed by the Federal Grant and Cooperative Agreement Act of 1977, as incorporated in Title 31 Section 6304 of the U.S. Code. A Federal grant is a:

"...legal instrument reflecting the relationship between the United States Government and a State, a local government, or other entity when 1) the principal purpose of the relationship is to transfer a thing of value to the State or local government or other recipient to carry out a public purpose of support or stimulation authorized by a law of the United States instead of acquiring (by purchase, lease, or barter) property or services for the direct benefit or use of the United States Government; and 2) substantial involvement is not expected between the executive agency and the State, local government, or other recipient when carrying out the activity contemplated in the agreement."

When an awarding agency expects to be substantially involved in a project (beyond routine monitoring and technical assistance), the law requires use of a cooperative agreement instead. When the government is procuring goods or services for its own direct benefit, and not for a broader public purpose, the law requires use of a federal contract.[1]

Types of grants

- Categorical grants

may be spent only for narrowly defined purposes and recipients often

must match a portion of the federal funds. 33% of categorical grants are

considered to be formula grants. About 90% of federal aid dollars are

spent for categorical grants.

- Project grants are grants given by the government to fund research projects, such as a research project for medical purposes. An individual must acquire certain qualifications before applying for such a grant and the normal duration for project grants is three years.

- Formula grants provide funds as dictated by a law.

- Block grants are large grants provided from the federal government to state or local governments for use in a general purpose.[2]

- Earmark grants are explicitly specified in appropriations of the U.S. Congress. They are not competitively awarded and have become highly controversial because of the heavy involvement of paid political lobbyists used in securing them. In FY1996 appropriations, the Congressional Research Service found 3,023 earmarks totaling $19.5 billion, while in FY2006 it found 12,852 earmarks totaling $64 billion.[3]

For charitable grants and funds for schools and organizations see: Grant writing and Grants.

There are over 900 grant programs offered by the 26 federal grant-making agencies. These programs fall into 20 categories:

- Agriculture

- Arts

- Business and Commerce

- Community Development

- Consumer Protection

- Disaster Prevention and Relief

- Education Regional Development

- Employment, Labor, and Training

- Energy

- Environmental Quality

- Food and Nutrition

- Health

- Housing

- Humanities

- Information and Statistics

- Law, Justice, and Legal Services

- Natural Resources

- Science and Technology

- Social Services and Income Security

- Transportation

Information provided in grant applications

Award information in grants generally includes:

- Estimated funding

- Expected number of awards

- Anticipated award size

- Period of performance

Eligibility information includes:

- Eligible applicants

- Cost sharing

Criticism

Federal and state grants frequently receive criticism due to what are perceived to be excessive regulations and not include opportunities for small business, as well as for often giving more money per person to smaller states regardless of population or need. These criticisms include problems of overlap, duplication, excessive categorization, insufficient information, varying requirements, arbitrary federal decision-making, and grantsmanship (a funding bias toward entities most familiar with how to exploit the system, rather than to those most in need). Research also suggests that federal grants are often allocated politically, with more money going to areas represented by the political party commanding a majority in Congress or that controls the presidency.[4][5][6]

Examples of grants by type

Block

- Community Development Block Grant

- Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Services Block Grant (ADMS)

- Substance Abuse Prevention and Treatment Block Grant (SABG or SAPT)

- Community Mental Health Services Block Grant (MHBG or CMHS)

- Local Law Enforcement Block Grant

- National Institutes of Health for bioscience research

- National Science Foundation for physical science research

Formulary

Categorical

See also

- Grant writing

- Federally Funded Research and Development Center (FFRDC)

- Funding Opportunity Announcement

- Small Business Administration

- National Grants Management Association (NGMA)

References

- Napolio, Nicholas G. 2021. “Implementing Presidential Particularism: Bureaucracy and the Distribution of Federal Grants.” Political Science Research and Methods. Cambridge University Press, 1–11. doi:10.1017/psrm.2021.29.

External links

- Grants.gov: Official U.S. government site for finding grants for non-profits

- Business.gov Loans and Grants Search: Find small business grants and loans from government agencies

- Presidential Initiative: Grants Management Line of Business

- ED.gov Federal Pell Grant Program: Official site for the federal pell grant

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Federal_grants_in_the_United_States

Category:Subsidies

Subcategories

This category has the following 2 subcategories, out of 2 total.

A

- Agricultural subsidies (35 P)

P

- Press subsidies (2 P)

Pages in category "Subsidies"

The following 51 pages are in this category, out of 51 total. This list may not reflect recent changes.

C

E

P

S

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Subsidies

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Agricultural_subsidies

A subsidy or government incentive is a type of government expenditure targeted towards individuals and households, as well as businesses with the aim of stabilising the economy. It ensures that individuals and households are viable by having access to essential goods and services while giving businesses the opportunity to stay afloat and/or competitive. Subsidies not only promote long term economic stability but also help governments to respond to economic shocks during a recession or in response to unforeseen shocks such as COVID-19.[1]

Subsidies take various forms such as direct government expenditures, tax incentives, soft loans, price support, and government provision of goods and services.[2] For instance, the government may distribute direct payment subsidies to individuals and households during an economic downturn in order to help its citizens pay their bills and to stimulate economic activity. Here, subsidies act as an effective financial aid issued when the economy experiences economic hardship.[3] They can also be a good policy tool to revise market imperfections when rational and competitive firms fail to produce an optimal market outcome. For example, in an imperfect market condition, governments can inject subsidies to encourage firms to invest in R&D (research and development). This will not only benefit the firms but also produce some positive externalities such that it benefits the industry in which the firms belong, and most importantly, the society at large.[4]

Although commonly extended from the government, the term subsidy can relate to any type of support – for example from NGOs or as implicit subsidies.

Subsidies come in various forms including: direct (cash grants, interest-free loans) and indirect (tax breaks, insurance, low-interest loans, accelerated depreciation, rent rebates).[5][6] Furthermore, they can be broad or narrow, legal or illegal, ethical or unethical. The most common forms of subsidies are those to the producer or the consumer. Producer/production subsidies ensure producers are better off by either supplying market price support, direct support, or payments to factors of production. [6] Consumer/consumption subsidies commonly reduce the price of goods and services to the consumer. For example, in the US at one time it was cheaper to buy gasoline than bottled water.[7]

All countries use subsidies via national and sub-national entities through different forms such as tax incentives and direct grants. Likewise, subsidies have an economic influence on both a domestic and international level. On a domestic level, subsidies affect the allocation decision of domestic resources, the distribution of income, and expenditure productivity. On an international level, subsidies may increase or decrease international interaction and integration through trade.[8] For this reason, having a thorough subsidy policy is essential as its inadequacy can potentially lead to financial hardship and problems for not only the poor or low income individuals but the aggregate economy as a whole.[9]

At large, subsidies take up a substantial portion of the government and economy. Amongst OECD countries in 2020, the median of subsidies and other transfers such as social benefits and non-repayable transfers to private and public enterprises was 56.3 percent of total government expenses which was 34.9 percent (weighted average) of GDP in the same year.[10] Yet, the number of subsidy measures in force have been rapidly increasing since 2008.[11]

Types

Production subsidy

A production subsidy encourages suppliers to increase the output of a particular product by partially offsetting the production costs or losses.[12] The objective of production subsidies is to expand production of a particular product more so that the market would promote but without raising the final price to consumers. This type of subsidy is predominantly found in developed markets.[6] Other examples of production subsidies include the assistance in the creation of a new firm (Enterprise Investment Scheme), industry (industrial policy) and even the development of certain areas (regional policy). Production subsidies are critically discussed in the literature as they can cause many problems including the additional cost of storing the extra produced products, depressing world market prices, and incentivizing producers to over-produce, for example, a farmer overproducing in terms of his land's carrying capacity.

Consumer/consumption subsidy

A consumption subsidy is one that subsidizes the behavior of consumers. This type of subsidies are most common in developing countries where governments subsidise such things as food, water, electricity and education on the basis that no matter how impoverished, all should be allowed those most basic requirements.[6] For example, some governments offer 'lifeline' rates for electricity, that is, the first increment of electricity each month is subsidized.[6] Evidence from recent studies suggests that government expenditures on subsidies remain high in many countries, often amounting to several percentage points of GDP. Subsidization on such a scale implies substantial opportunity costs. There are at least three compelling reasons for studying government subsidy behavior. First, subsidies are a major instrument of government expenditure policy. Second, on a domestic level, subsidies affect domestic resource allocation decisions, income distribution, and expenditure productivity. A consumer subsidy is a shift in demand as the subsidy is given directly to consumers.

Export subsidy

An export subsidy is a support from the government for products that are exported, as a means of assisting the country's balance of payments.[12] Usha Haley and George Haley identified the subsidies to manufacturing industry provided by the Chinese government and how they have altered trade patterns.[5] Traditionally, economists have argued that subsidies benefit consumers but hurt the subsidizing countries. Haley and Haley provided data to show that over the decade after China joined the World Trade Organization industrial subsidies have helped give China an advantage in industries in which they previously enjoyed no comparative advantage such as the steel, glass, paper, auto parts, and solar industries.[5] China's shores have also collapsed from overfishing and industrialization, which is why the Chinese government heavily subsidizes its fishermen, who sail the world in search of new grounds.[13]

Export subsidy is known for being abused. For example, some exporters substantially over declare the value of their goods so as to benefit more from the export subsidy. Another method is to export a batch of goods to a foreign country but the same goods will be re-imported by the same trader via a circuitous route and changing the product description so as to obscure their origin. Thus the trader benefits from the export subsidy without creating real trade value to the economy. Export subsidy as such can become a self-defeating and disruptive policy.

Adam Smith observed that special government subsidies enabled exporters to sell abroad at substantial ongoing losses. He did not regard that as a sound and sustainable policy. That was because “… under normal industrial-commercial conditions their own interests soon oblige loss-making businesses to deploy their capital in other ways – or to move into markets where the sales prices do cover the supply costs and yield ordinary profits. Like other mercantilist schemes and devices, export bounties are a means of trying to force business capital into channels it would not naturally enter. The schemes are invariably costly and damaging in various ways.”[14]

Import subsidy

An import subsidy is support from the government for products that are imported. Rarer than an export subsidy, an import subsidy further reduces the price to consumers for imported goods. Import subsidies have various effects depending on the subject. For example, consumers in the importing country are better off and experience an increase in consumer welfare due to the decrease in price of the imported goods, as well as the decrease in price of the domestic substitute goods. Conversely, the consumers in the exporting country experience a decrease in consumer welfare due to an increase in the price of their domestic goods. Furthermore, producers of the importing country experience a loss of welfare due to a decrease of the price for the good in their market, while on the other side, the exporters of the producing country experience an increase in well being due to the increase in demand. Ultimately, the import subsidy is rarely used due to an overall loss of welfare for the country due to a decrease in domestic production and a reduction in production throughout the world. However, that can result in a redistribution of income.[15]

Employment subsidy

Employment or wage subsidies keep the employment relationship ongoing even during financial crisis. It is particularly beneficial for enterprises to recover quickly after a temporary suspension following a crisis. Workers are prevented from losing their jobs and other associated employment benefits such as annual leave entitlements and retirement pensions.[16]

Employment subsidies allow individual beneficiaries a minimum standard of living at the very least. However, less than half of active jobseekers in around 50% of OECD countries receive unemployment support.[17] The effect of employment subsidies may not be evident immediately. When employers received grants to subside a substantial part of the wages for retaining their employees or to create new jobs during severe recessions such as the 2008 GFC (Global Financial Crisis), there were minor impacts on employment during the first year. However, the subsidy began to yield positive effects on employment, particularly a decrease in the unemployment rate, in the second year as employers began to properly utilise the subsidy.[18]

Tax subsidy

Tax subsidies, also known as tax breaks or tax expenditures, are a way for governments to achieve certain outcomes without directly providing cash payments. By offering tax breaks, the government can incentivize behavior that is beneficial to the economy or society as a whole. However, tax subsidies can also have negative consequences.

One type of tax subsidy is a health tax deduction, which allows individuals or businesses to deduct their health expenses from their taxable income. This can be seen as a way to incentivize people to prioritize their health and well-being. However, it can also create distortions in the economy by encouraging people to spend more on health care than they otherwise would.

Another type of tax subsidy is related to Intellectual Property. Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) is a particular form of tax subsidy that involves companies shifting their profits to low-tax jurisdictions in order to reduce their overall tax burden. The [[Multilateral Convention to Implement Tax Treaty Related Measures to Prevent Base Erosion and Profit Shifting] is a treaty signed by half the nations of the world aimed at preventing this type of tax avoidance.

While tax subsidies can be effective in achieving certain outcomes, they are also less transparent than direct cash payments and can be difficult to undo. Additionally, some argue that tax breaks disproportionately benefit the wealthy and large corporations, further exacerbating income inequality. Therefore, it is important for governments to carefully consider the potential consequences of offering tax subsidies and ensure that they are targeted towards achieving the greatest public good.

Furthermore, tax subsidies can have unintended consequences, such as creating market distortions that favor certain industries or companies over others. For example, if a government offers tax breaks to incentivize investment in renewable energy, it may lead to a glut of renewable energy projects and an oversupply of energy in the market. This, in turn, can lead to lower prices for energy and financial losses for investors.

In addition, tax subsidies can be difficult to monitor and enforce, which can lead to abuse and fraud. Companies may claim tax breaks for activities that do not qualify, or may use complex legal structures to shift profits to lower tax jurisdictions. This can result in lost revenue for governments and a lack of fairness in the tax system.

Despite these concerns, tax subsidies remain a popular tool for governments to promote various policy objectives, such as economic growth, job creation, and environmental sustainability. The use of tax subsidies is often debated in political circles, with some arguing that they are necessary to support certain industries or to incentivize certain behaviors, while others argue that they create inefficiencies and distortions in the economy.

In conclusion, tax subsidies are a powerful tool for governments to achieve policy goals, but they come with their own set of challenges and limitations. It is important for policymakers to carefully consider the potential unintended consequences of tax subsidies and to design them in a way that maximizes their benefits while minimizing their costs. Additionally, strong monitoring and enforcement mechanisms are needed to ensure that tax subsidies are used appropriately and do not result in abuse or fraud.

Transport subsidies

Some governments subsidise transport, especially rail and bus transport, which decrease congestion and pollution compared to cars. In the EU, rail subsidies are around €73 billion, and Chinese subsidies reach $130 billion.[19][20]

Publicly owned airports can be an indirect subsidy if they lose money. The European Union, for instance, criticizes Germany for its high number of money-losing airports that are used primarily by low cost carriers, characterizing the arrangement as an illegal subsidy.[citation needed]

In many countries, roads and highways are paid for through general revenue, rather than tolls or other dedicated sources that are paid only by road users, creating an indirect subsidy for road transportation. The fact that long-distance buses in Germany do not pay tolls has been called an indirect subsidy by critics, who point to track access charges for railways.

Energy subsidies

Energy subsidies are measures that keep prices for customers below market levels, or for suppliers above market levels, or reduce costs for customers and suppliers.[21][22] Energy subsidies may be direct cash transfers to suppliers, customers, or related bodies, as well as indirect support mechanisms, such as tax exemptions and rebates, price controls, trade restrictions, and limits on market access.

The International Renewable Energy Agency tracked some $634 billion in energy-sector subsidies in 2020, and found that around 70% were fossil fuel subsidies. About 20% went to renewable power generation, 6% to biofuels and just over 3% to nuclear.[23]Fossil fuels

Fossil fuel subsidies are energy subsidies on fossil fuels. They may be tax breaks on consumption, such as a lower sales tax on natural gas for residential heating; or subsidies on production, such as tax breaks on exploration for oil. Or they may be free or cheap negative externalities; such as air pollution or climate change due to burning gasoline, diesel and jet fuel. Some fossil fuel subsidies are via electricity generation, such as subsidies for coal-fired power stations.

Eliminating fossil fuel subsidies would reduce the health risks of air pollution,[24] and would greatly reduce global carbon emissions thus helping to limit climate change.[25] As of 2021, policy researchers estimate that substantially more money is spent on fossil fuel subsidies than on environmentally harmful agricultural subsidies or environmentally harmful water subsidies.[26]

The International Energy Agency says that “High fossil fuel prices hit the poor hardest, but subsidies are rarely well-targeted to protect vulnerable groups and tend to benefit better-off segments of the population.”[27]

Despite the G20 countries having pledged to phase-out inefficient fossil fuel subsidies,[28] as of 2023 they continue because of voter demand[29] or for energy security.[30] Global fossil fuel consumption subsidies in 2022 have been estimated at one trillion dollars;[27] although they vary each year depending on oil prices they are consistently hundreds of billions of dollars.[31]Housing subsidies

Housing subsidies are designed to promote the construction industry and homeownership. As of 2018, U.S housing subsidies total around $15 billion per year. Housing subsidies can come in two types; assistance with down payment and interest rate subsidies. The deduction of mortgage interest from the federal income tax accounts for the largest interest rate subsidy. Additionally, the federal government will help low-income families with the down payment, coming to $10.9 million in 2008.[32]

As a housing policy tool, housing subsidies also help low income individuals gain and maintain liveable residency by easing the cost burdens of housing for low income individuals and households. However, some policy makers and experts believe they are costly to implement and may even reduce incentives for beneficiaries to participate in the labour market. In the contrary, certain literatures have found that subsidy cuts do not encourage employment or participation among beneficiaries. For example, research by Daniel Borbely found that reducing housing subsidies did not increase employment and labour force participation. Though, he also added that claimants relocated to other areas of the rental market to maintain their benefits.[33]

Nonetheless, the most common method for providing housing subsidies is via direct payments to renters by covering a part of their rent on the private rent market. This method of direct transfer of housing subsidies is often referred to as 'housing vouchers'. In the United States, the so-called Section 8 is a direct payment program subsidising the largest amount of money to renters for rental assistance.[34]

Environmental externalities

While conventional subsidies require financial support, many economists have described implicit subsidies in the form of untaxed environmental externalities.[7] These externalities include things such as pollution from vehicle emissions, pesticides, or other sources.

A 2015 report studied the implicit subsidies accruing to 20 fossil fuel companies. It estimated that the societal costs from downstream emissions and pollution attributable to these companies were substantial.[35][36] The report spans the period 2008–2012 and notes that: "for all companies and all years, the economic cost to society of their CO2 emissions was greater than their after‐tax profit, with the single exception of ExxonMobil in 2008."[35]: 4 Pure coal companies fare even worse: "the economic cost to society exceeds total revenue (employment, taxes, supply purchases, and indirect employment) in all years, with this cost varying between nearly $2 and nearly $9 per $1 of revenue."[35]: 4–5

Categorising subsidies

Direct and Indirect

The first important classification of subsidies are direct and indirect subsidies. Subsidies are categorised as direct when it involves actual cash outlays targeted towards a specified individual or household. Popular examples include is cash grants and interest-free loans. Subsidies can also be classified as indirect when they do not involve actual payments. An example would be an increase in disposable income arising from a decrease in price of an essential good or service that the government has enforced in a form of monetary support. In contrast, a decrease in the price of a good or service may lead to an increase in revenue for producers earned from the heightened demand by consumers.[37]

The use of indirect subsidies such as price controls is widespread among developing economies and emerging markets as a necessary tool for social policy. It has proven to be effective in many cases but price controls have a potential to dampen investment activity and growth, cause heavy fiscal burdens for the government, and may even complicate the optimal performance of monetary policy. To prevent the undesirable negative effects, price control regimes may be replaced by creating social safety nets and proposing sound reforms to encourage competition and growth.[38]

Production and Consumption

Another important classification of subsidies are producer/production subsidies and consumer/consumption subsidies. Production subsidies are designed to ensure producers are advantaged by creating fluid market activity through other market control mechanisms or by providing cash payments for factors of production. Consumption subsidies benefit consumers typically through a reduction in the market price of goods and services. They are commonly used by governments of many developing countries in an attempt to secure the most basic needs for its population.[39]

Broad and Narrow

These various subsidies can be divided into broad and narrow. Narrow subsidies are those monetary transfers that are easily identifiable and have a clear intent. They are commonly characterised by a monetary transfer between governments and institutions or businesses and individuals. A classic example is a government payment to a farmer.[40]

Monetary and Non-monetary

Conversely broad subsidies include both monetary and non-monetary subsidies and is often difficult to identify.[40] A broad subsidy is less attributable and less transparent. Environmental externalities are the most common type of broad subsidy.

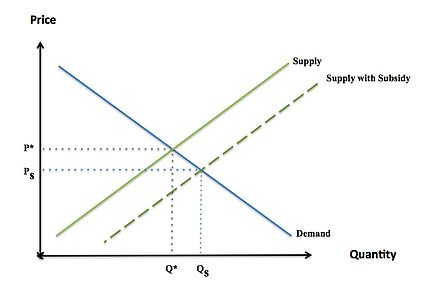

Economic effects

Competitive equilibrium is a state of balance between buyers and suppliers, in which the quantity demanded of a good is the quantity supplied at a specified price. When the price falls the quantity demand exceeds the equilibrium quantity, conversely, a reduction in the supply of a good beyond equilibrium quantity implies an increase in the price. The effect of a subsidy is to shift the supply or demand curve to the right (i.e. increases the supply or demand) by the amount of the subsidy. If a consumer is receiving the subsidy, a lower price of a good resulting from the marginal subsidy on consumption increases demand, shifting the demand curve to the right. If a supplier is receiving the subsidy, an increase in the price (revenue) resulting from the marginal subsidy on production results increases supply, shifting the supply curve to the right.

Assuming the market is in a perfectly competitive equilibrium, a subsidy increases the supply of the good beyond the equilibrium competitive quantity. The imbalance creates deadweight loss. Deadweight loss from a subsidy is the amount by which the cost of the subsidy exceeds the gains of the subsidy.[41] The magnitude of the deadweight loss is dependent on the size of the subsidy. This is considered a market failure, or inefficiency.[41]

Subsidies targeted at goods in one country, by lowering the price of those goods, make them more competitive against foreign goods, thereby reducing foreign competition.[42] As a result, many developing countries cannot engage in foreign trade, and receive lower prices for their products in the global market. This is considered protectionism: a government policy to erect trade barriers in order to protect domestic industries.[43] The problem with protectionism arises when industries are selected for nationalistic reasons (infant-industry), rather than to gain a comparative advantage. The market distortion, and reduction in social welfare, is the logic behind the World Bank policy for the removal of subsidies in developing countries.[44]

Subsidies create spillover effects in other economic sectors and industries. A subsidized product sold in the world market lowers the price of the good in other countries. Since subsidies result in lower revenues for producers of foreign countries, they are a source of tension between the United States, Europe and poorer developing countries.[45] While subsidies may provide immediate benefits to an industry, in the long-run they may prove to have unethical, negative effects. Subsidies are intended to support public interest, however, they can violate ethical or legal principles if they lead to higher consumer prices or discriminate against some producers to benefit others.[42] For example, domestic subsidies granted by individual US states may be unconstitutional if they discriminate against out-of-state producers, violating the Privileges and Immunities Clause or the Dormant Commerce Clause of the United States Constitution.[42] Depending on their nature, subsidies are discouraged by international trade agreements such as the World Trade Organization (WTO). This trend, however, may change in the future, as needs of sustainable development and environmental protection could suggest different interpretations regarding energy and renewable energy subsidies.[46] In its July 2019 report, "Going for Growth 2019: The time for reform is now", the OECD suggests that countries make better use of environmental taxation, phase out agricultural subsidies and environmentally harmful tax breaks.[47][48]

Preventing fraud

In the Netherlands, audits are performed to verify whether the funds that have been received has indeed been spent legally (and all requirements of the subsidy provider have been attained), for the purpose intended.[49] It hence prevents fraud.

Perverse subsidies

The neutrality of this section is disputed. Relevant discussion may be found on the talk page. Please do not remove this message until conditions to do so are met. (September 2019) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

Definitions

Although subsidies can be important, many are "perverse", in the sense of having adverse unintended consequences. To be "perverse", subsidies must exert effects that are demonstrably and significantly adverse both economically and environmentally.[6] A subsidy rarely, if ever, starts perverse, but over time a legitimate efficacious subsidy can become perverse or illegitimate if it is not withdrawn after meeting its goal or as political goals change. Perverse subsidies are now so widespread that as of 2007 they amounted $2 trillion per year in the six most subsidised sectors alone (agriculture, fossil fuels, road transportation, water, fisheries and forestry).[50]

Effects

The detrimental effects of perverse subsidies are diverse in nature and reach. Case-studies from differing sectors are highlighted below but can be summarised as follows.

Directly, they are expensive to governments by directing resources away from other legitimate should priorities (such as environmental conservation, education, health, or infrastructure),[51][40][52][53] ultimately reducing the fiscal health of the government.[54]

Indirectly, they cause environmental degradation (exploitation of resources, pollution, loss of landscape, misuse and overuse of supplies) which, as well as its fundamental damage, acts as a further brake on economies; tend to benefit the few at the expense of the many, and the rich at the expense of the poor; lead to further polarization of development between the Northern and Southern hemispheres; lower global market prices; and undermine investment decisions reducing the pressure on businesses to become more efficient.[7][53][55] Over time the latter effect means support becomes enshrined in human behaviour and business decisions to the point where people become reliant on, even addicted to, subsidies, 'locking' them into society.[56]

Consumer attitudes do not change and become out-of-date, off-target and inefficient;[7] furthermore, over time people feel a sense of historical right to them.[55]

Implementation

Perverse subsidies are not tackled as robustly as they should be. Principally, this is because they become 'locked' into society, causing bureaucratic roadblocks and institutional inertia.[57][58] When cuts are suggested many argue (most fervently by those 'entitled', special interest groups and political lobbyists) that it will disrupt and harm the lives of people who receive them, distort domestic competitiveness curbing trade opportunities, and increase unemployment.[55][59] Individual governments recognise this as a 'prisoner's dilemma' – insofar as that even if they wanted to adopt subsidy reform, by acting unilaterally they fear only negative effects will ensue if others do not follow.[56] Furthermore, cutting subsidies, however perverse they may be, is considered a vote-losing policy.[57]

Reform of perverse subsidies is at a propitious time. The current economic conditions mean governments are forced into fiscal constraints and are looking for ways to reduce activist roles in their economies.[58] There are two main reform paths: unilateral and multilateral. Unilateral agreements (one country) are less likely to be undertaken for the reasons outlined above, although New Zealand,[60] Russia, Bangladesh and others represent successful examples.[7] Multilateral actions by several countries are more likely to succeed as this reduces competitiveness concerns, but are more complex to implement requiring greater international collaboration through a body such as the WTO.[53] Irrespective of the path, the aim of policymakers should be to: create alternative policies that target the same issue as the original subsidies but better; develop subsidy removal strategies allowing market-discipline to return; introduce 'sunset' provisions that require remaining subsidies to be re-justified periodically; and make perverse subsidies more transparent to taxpayers to alleviate the 'vote-loser' concern.[7]

Examples

Agricultural subsidies

Support for agriculture dates back to the 19th century. It was developed extensively in the EU and USA across the two World Wars and the Great Depression to protect domestic food production, but remains important across the world today.[53][57] In 2005, US farmers received $14 billion and EU farmers $47 billion in agricultural subsidies.[42] Today, agricultural subsidies are defended on the grounds of helping farmers to maintain their livelihoods. The majority of payments are based on outputs and inputs and thus favour the larger producing agribusinesses over the small-scale farmers.[6][61] In the USA nearly 30% of payments go to the top 2% of farmers.[53][62][63]

By subsidising inputs and outputs through such schemes as 'yield based subsidisation', farmers are encouraged to over-produce using intensive methods, including using more fertilizers and pesticides; grow high-yielding monocultures; reduce crop rotation; shorten fallow periods; and promote exploitative land use change from forests, rainforests and wetlands to agricultural land.[53] These all lead to severe environmental degradation, including adverse effects on soil quality and productivity including erosion, nutrient supply and salinity which in turn affects carbon storage and cycling, water retention and drought resistance; water quality including pollution, nutrient deposition and eutrophication of waterways, and lowering of water tables; diversity of flora and fauna including indigenous species both directly and indirectly through the destruction of habitats, resulting in a genetic wipe-out.[6][53][64][65]

Cotton growers in the US reportedly receive half their income from the government under the Farm Bill of 2002. The subsidy payments stimulated overproduction and resulted in a record cotton harvest in 2002, much of which had to be sold at very reduced prices in the global market.[42] For foreign producers, the depressed cotton price lowered their prices far below the break-even price. In fact, African farmers received 35 to 40 cents per pound for cotton, while US cotton growers, backed by government agricultural payments, received 75 cents per pound. Developing countries and trade organizations argue that poorer countries should be able to export their principal commodities to survive, but protectionist laws and payments in the United States and Europe prevent these countries from engaging in international trade opportunities.

Fisheries

Today, much of the world's major fisheries are overexploited; in 2002, the WWF estimate this at approximately 75%. Fishing subsidies include "direct assistant to fishers; loan support programs; tax preferences and insurance support; capital and infrastructure programs; marketing and price support programs; and fisheries management, research, and conservation programs."[66] They promote the expansion of fishing fleets, the supply of larger and longer nets, larger yields and indiscriminate catch, as well as mitigating risks which encourages further investment into large-scale operations to the disfavour of the already struggling small-scale industry.[53][67] Collectively, these result in the continued overcapitalization and overfishing of marine fisheries.

There are four categories of fisheries subsidies. First are direct financial transfers, second are indirect financial transfers and services. Third, certain forms of intervention and fourth, not intervening. The first category regards direct payments from the government received by the fisheries industry. These typically affect profits of the industry in the short term and can be negative or positive. Category two pertains to government intervention, not involving those under the first category. These subsidies also affect the profits in the short term but typically are not negative. Category three includes intervention that results in a negative short-term economic impact, but economic benefits in the long term. These benefits are usually more general societal benefits such as the environment. The final category pertains to inaction by the government, allowing producers to impose certain production costs on others. These subsidies tend to lead to positive benefits in the short term but negative in the long term.[68]

Manufacturing subsidies

A survey of manufacturing in Britain found government subsidies had had various unintended dysfunctional consequences. The subsidies had usually been selective or discriminatory – benefiting some companies at the expense of others. Government money in the form of grants and awards of production and R&D contracts had gone to advanced and viable firms as well as old uneconomic enterprises. However, the main recipients had been larger, established companies – while most of the firms pioneering radical technical-product developments with long-term economic growth potential had been new small enterprises. The study concluded that instead of providing subsidies, governments wanting to benefit industrial-technological development and performance should lower standard rates of business taxation, raise tax allowances for investments in new plant, equipment and products, and remove obstacles to market competition and customer choice.[69]

Others

The US National Football League's (NFL) profits have topped records at $11 billion, the highest of all sports. The NFL had tax-exempt status until voluntarily relinquishing it in 2015, and new stadiums have been built with public subsidies.[70][71]

The Commitment to Development Index (CDI), published by the Center for Global Development, measures the effect that subsidies and trade barriers actually have on the undeveloped world. It uses trade, along with six other components such as aid or investment, to rank and evaluate developed countries on policies that affect the undeveloped world. It finds that the richest countries spend $106 billion per year subsidizing their own farmers – almost exactly as much as they spend on foreign aid.[72]

Short list of subsidies

- Agricultural subsidy

- Fisheries subsidy

- Export subsidy

- Energy subsidy

- Fossil fuel subsidies (oil subsidies, coal subsidies, gas subsidies)

- Photovoltaics subsidy

- Party subsidies

- Wage subsidy

- Artist subsidy (Netherlands)

See also

- Agricultural subsidy

- Cross subsidization

- Cultural subsidy

- Energy subsidy

- Subsidization of company cars

- Federal government

- Audit software in governmental procurement

- Municipal services

- Perverse incentive

- Rail subsidies

- Stadium subsidy

- Tax exemption

- Wage subsidy

References

"Fossil-fuel subsidies generally take two forms. Production subsidies...[and]...Consumption subsidies...

- Fowler, P.; Fokker, R. (2004). A Sweeter Future? The potential for EU sugar reform to contribute to poverty reduction in Southern Africa. Oxford: Oxfam International. ISBN 9781848141940.

Further reading

| Library resources about Subsidy |

- OECD (2001) Environmentally Harmful Subsidies: Policy Issues and Challenges. France: OECD Productions. http://www.inecc.gob.mx/descargas/dgipea/harmful_subsidies.pdf

External links

- Another Day, Another Bad Incentive Deal (2014-06-06), Naked Capitalism

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Subsidy

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Subsidary

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Subordinate_agency_etc.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Payments

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Payment_terms

In business practice, cash account refers to a business-to-business or business-to-consumer account which is conducted on an immediate payment basis i.e. no credit is offered.[1]

In accounting practice, "cash account" or "cash book" refers to a daybook (Main entry book) used to record all transactions related to cash, especially cash receipts and payments. Cash account is considered as a special daybook because of its dual impact in Accounting. Cash account acts as a main entry book as well as a ledger in Accounting. The dual impact of Cash book occurs due to the presence of two sides (entities):- Debit and Credit.

Cash account is the combination of Cash receipts journal and cash payment journal and hence called as "Cash receipts and payment journal". Receipt and payment voucher are the source documents of Cash book. Receipt is an evidence to the cash receipts and payment voucher is an evidence to the cash payments.

Simply cash account is considered as an account you have with a brokerage firm, in which you deposit cash to buy stocks, bonds and other securities[2]

References

- Staff, Investopedia (2003-11-18). "Cash Account". Investopedia. Retrieved 2017-09-15.

This finance-related article is a stub. You can help Wikipedia by expanding it. |

This accounting-related article is a stub. You can help Wikipedia by expanding it. |

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cash_account

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Accounting_journals_and_ledgers

| Part of a series on |

| Accounting |

|---|

|

|

|

Major types |

|

|

Key concepts |

|

|

Selected accounts |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

People and organizations |

|

|

Development |

|

|

Misconduct |

Debits and credits in double-entry bookkeeping are entries made in account ledgers to record changes in value resulting from business transactions. A debit entry in an account represents a transfer of value to that account, and a credit entry represents a transfer from the account.[1][2] Each transaction transfers value from credited accounts to debited accounts. For example, a tenant who writes a rent cheque to a landlord would enter a credit for the bank account on which the cheque is drawn, and a debit in a rent expense account. Similarly, the landlord would enter a credit in the rent income account associated with the tenant and a debit for the bank account where the cheque is deposited.

Debits and credits are traditionally distinguished by writing the transfer amounts in separate columns of an account book. The use of separate columns simplifies calculation of the balance for the account. First the debit column is totaled, then the credit column is totaled. The account balance is calculated by subtracting the smaller total from the larger total. Only one subtraction is needed, simplifying calculations before the availability of computers.

Alternately, debits and credits can be listed in one column, indicating debits with the suffix "Dr" or writing them plain, and indicating credits with the suffix "Cr" or a minus sign. Despite the use of a minus sign, debits and credits do not correspond directly to positive and negative numbers. When the total of debits in an account exceeds the total of credits, the account is said to have a net debit balance equal to the difference; when the opposite is true, it has a net credit balance.

Debit balances are normal for asset and expense accounts, and credit balances are normal for liability, equity and revenue accounts. When a particular account has a normal balance, it is reported as a positive number, while a negative balance indicates an abnormal situation, as when a bank account is overdrawn. [3] In some systems, negative balances are highlighted in red type.

History

The first known recorded use of the terms is Venetian Luca Pacioli's 1494 work, Summa de Arithmetica, Geometria, Proportioni et Proportionalita (A Summary of Arithmetic, Geometry, Proportions and Proportionality). Pacioli devoted one section of his book to documenting and describing the double-entry bookkeeping system in use during the Renaissance by Venetian merchants, traders and bankers. This system is still the fundamental system in use by modern bookkeepers.[4] Indian merchants had developed a double-entry bookkeeping system, called bahi-khata, predating Pacioli's work by at least many centuries,[5] and which was likely a direct precursor of the European adaptation.[6]

It is sometimes said that, in its original Latin, Pacioli's Summa used the Latin words debere (to owe) and credere (to entrust) to describe the two sides of a closed accounting transaction. Assets were owed to the owner and the owners' equity was entrusted to the company. At the time negative numbers were not in use. When his work was translated, the Latin words debere and credere became the English debit and credit. Under this theory, the abbreviations Dr (for debit) and Cr (for credit) derive directly from the original Latin.[7] However, Sherman[8] casts doubt on this idea because Pacioli uses Per (Italian for "by") for the debtor and A (Italian for "to") for the creditor in the Journal entries. Sherman goes on to say that the earliest text he found that actually uses "Dr." as an abbreviation in this context was an English text, the third edition (1633) of Ralph Handson's book Analysis or Resolution of Merchant Accompts[9] and that Handson uses Dr. as an abbreviation for the English word "debtor." (Sherman could not locate a first edition, but speculates that it too used Dr. for debtor.) The words actually used by Pacioli for the left and right sides of the Ledger are "in dare" and "in havere" (give and receive).[10] Geijsbeek the translator suggests in the preface:

'if we today would abolish the use of the words debit and credit in the ledger and substitute the ancient terms of "shall give" and "shall have" or "shall receive", the personification of accounts in the proper way would not be difficult and, with it, bookkeeping would become more intelligent to the proprietor, the layman and the student.'[11]

As Jackson has noted, "debtor" need not be a person, but can be an abstract party:

"...it became the practice to extend the meanings of the terms ... beyond their original personal connotation and apply them to inanimate objects and abstract conceptions..."[12]

This sort of abstraction is already apparent in Richard Dafforne's 17th-century text The Merchant's Mirror, where he states "Cash representeth (to me) a man to whom I … have put my money into his keeping; the which by reason is obliged to render it back."

Aspects of transactions

There are three kinds of accounts:

- Real accounts relate to the assets of a company, which may be tangible (machinery, buildings etc.) or intangible (goodwill, patents etc.)

- Personal accounts relate to individuals, companies, creditors, banks etc.

- Nominal accounts relate to expenses, losses, incomes or gains.

To determine whether to debit or credit a specific account, we use either the accounting equation approach (based on five accounting rules),[13] or the classical approach (based on three rules).[14] Whether a debit increases or decreases an account's net balance depends on what kind of account it is. The basic principle is that the account receiving benefit is debited, while the account giving benefit is credited. For instance, an increase in an asset account is a debit. An increase in a liability or an equity account is a credit.

The classical approach has three golden rules, one for each type of account:[15]

- Real accounts: Debit whatever comes in and credit whatever goes out.

- Personal accounts: Receiver's account is debited and giver's account is credited.

- Nominal accounts: Expenses and losses are debited and incomes and gains are credited.

The complete accounting equation based on the modern approach is very easy to remember if you focus on Assets, Expenses, Costs, Dividends (highlighted in chart). All those account types increase with debits or left side entries. Conversely, a decrease to any of those accounts is a credit or right side entry. On the other hand, increases in revenue, liability or equity accounts are credits or right side entries, and decreases are left side entries or debits.

| Kind of account | Debit | Credit |

|---|---|---|

| Asset | Increase | Decrease |

| Liability | Decrease | Increase |

| Income/Revenue | Decrease | Increase |

| Expense/Cost/Dividend | Increase | Decrease |

| Equity/Capital | Decrease | Increase |

| Accounts with normal debit balances are in bold | ||

Debits and credits occur simultaneously in every financial transaction in double-entry bookkeeping. In the accounting equation, Assets = Liabilities + Equity, so, if an asset account increases (a debit (left)), then either another asset account must decrease (a credit (right)), or a liability or equity account must increase (a credit (right)). In the extended equation, revenues increase equity and expenses, costs & dividends decrease equity, so their difference is the impact on the equation.

For example, if a company provides a service to a customer who does not pay immediately, the company records an increase in assets, Accounts Receivable with a debit entry, and an increase in Revenue, with a credit entry. When the company receives the cash from the customer, two accounts again change on the company side, the cash account is debited (increased) and the Accounts Receivable account is now decreased (credited). When the cash is deposited to the bank account, two things also change, on the bank side: the bank records an increase in its cash account (debit) and records an increase in its liability to the customer by recording a credit in the customer's account (which is not cash). Note that, technically, the deposit is not a decrease in the cash (asset) of the company and should not be recorded as such. It is just a transfer to a proper bank account of record in the company's books, not affecting the ledger.

To make it more clear, the bank views the transaction from a different perspective but follows the same rules: the bank's vault cash (asset) increases, which is a debit; the increase in the customer's account balance (liability from the bank's perspective) is a credit. A customer's periodic bank statement generally shows transactions from the bank's perspective, with cash deposits characterized as credits (liabilities) and withdrawals as debits (reductions in liabilities) in depositor's accounts. In the company's books the exact opposite entries should be recorded to account for the same cash. This concept is important since this is why so many people misunderstand what debit/credit really means.

Commercial understanding

This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (October 2014) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

When setting up the accounting for a new business, a number of accounts are established to record all business transactions that are expected to occur. Typical accounts that relate to almost every business are: Cash, Accounts Receivable, Inventory, Accounts Payable and Retained Earnings. Each account can be broken down further, to provide additional detail as necessary. For example: Accounts Receivable can be broken down to show each customer that owes the company money. In simplistic terms, if Bob, Dave, and Roger owe the company money, the Accounts Receivable account will contain a separate account for Bob, and Dave and Roger. All 3 of these accounts would be added together and shown as a single number (i.e. total 'Accounts Receivable' – balance owed) on the balance sheet. All accounts for a company are grouped together and summarized on the balance sheet in 3 sections which are: Assets, Liabilities and Equity.

All accounts must first be classified as one of the five types of accounts (accounting elements) ( asset, liability, equity, income and expense). To determine how to classify an account into one of the five elements, the definitions of the five account types must be fully understood. The definition of an asset according to IFRS is as follows, "An asset is a resource controlled by the entity as a result of past events from which future economic benefits are expected to flow to the entity".[16] In simplistic terms, this means that Assets are accounts viewed as having a future value to the company (i.e. cash, accounts receivable, equipment, computers). Liabilities, conversely, would include items that are obligations of the company (i.e. loans, accounts payable, mortgages, debts).

The Equity section of the balance sheet typically shows the value of any outstanding shares that have been issued by the company as well as its earnings. All Income and expense accounts are summarized in the Equity Section in one line on the balance sheet called Retained Earnings. This account, in general, reflects the cumulative profit (retained earnings) or loss (retained deficit) of the company.

The Profit and Loss Statement is an expansion of the Retained Earnings Account. It breaks-out all the Income and expense accounts that were summarized in Retained Earnings. The Profit and Loss report is important in that it shows the detail of sales, cost of sales, expenses and ultimately the profit of the company. Most companies rely heavily on the profit and loss report and review it regularly to enable strategic decision making.

Terminology

This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (October 2014) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

The words debit and credit can sometimes be confusing because they depend on the point of view from which a transaction is observed. In accounting terms, assets are recorded on the left side (debit) of asset accounts, because they are typically shown on the left side of the accounting equation (A=L+SE). Likewise, an increase in liabilities and shareholder's equity are recorded on the right side (credit) of those accounts, thus they also maintain the balance of the accounting equation. In other words, if "assets are increased with left side entries, the accounting equation is balanced only if increases in liabilities and shareholder’s equity are recorded on the opposite or right side. Conversely, decreases in assets are recorded on the right side of asset accounts, and decreases in liabilities and equities are recorded on the left side". Similar is the case with revenues and expenses, what increases shareholder's equity is recorded as credit because they are in the right side of equation and vice versa.[17] Typically, when reviewing the financial statements of a business, Assets are Debits and Liabilities and Equity are Credits. For example, when two companies transact with one another say Company A buys something from Company B then Company A will record a decrease in cash (a Credit), and Company B will record an increase in cash (a Debit). The same transaction is recorded from two different perspectives.

This use of the terms can be counter-intuitive to people unfamiliar with bookkeeping concepts, who may always think of a credit as an increase and a debit as a decrease. This is because most people typically only see their personal bank accounts and billing statements (e.g., from a utility). A depositor's bank account is actually a Liability to the bank, because the bank legally owes the money to the depositor. Thus, when the customer makes a deposit, the bank credits the account (increases the bank's liability). At the same time, the bank adds the money to its own cash holdings account. Since this account is an Asset, the increase is a debit. But the customer typically does not see this side of the transaction.[18]

On the other hand, when a utility customer pays a bill or the utility corrects an overcharge, the customer's account is credited. This is because the customer's account is one of the utility's accounts receivable, which are Assets to the utility because they represent money the utility can expect to receive from the customer in the future. Credits actually decrease Assets (the utility is now owed less money). If the credit is due to a bill payment, then the utility will add the money to its own cash account, which is a debit because the account is another Asset. Again, the customer views the credit as an increase in the customer's own money and does not see the other side of the transaction.

Debit cards and credit cards

Debit cards and credit cards are creative terms used by the banking industry to market and identify each card.[19] From the cardholder's point of view, a credit card account normally contains a credit balance, a debit card account normally contains a debit balance. A debit card is used to make a purchase with one's own money. A credit card is used to make a purchase by borrowing money.[20]

From the bank's point of view, when a debit card is used to pay a merchant, the payment causes a decrease in the amount of money the bank owes to the cardholder. From the bank's point of view, your debit card account is the bank's liability. A decrease to the bank's liability account is a debit. From the bank's point of view, when a credit card is used to pay a merchant, the payment causes an increase in the amount of money the bank is owed by the cardholder. From the bank's point of view, your credit card account is the bank's asset. An increase to the bank's asset account is a debit. Hence, using a debit card or credit card causes a debit to the cardholder's account in either situation when viewed from the bank's perspective.

General ledgers

General ledger is the term for the comprehensive collection of T-accounts (it is so called because there was a pre-printed vertical line in the middle of each ledger page and a horizontal line at the top of each ledger page, like a large letter T). Before the advent of computerized accounting, manual accounting procedure used a ledger book for each T-account. The collection of all these books was called the general ledger. The chart of accounts is the table of contents of the general ledger. Totaling of all debits and credits in the general ledger at the end of a financial period is known as trial balance.

"Daybooks" or journals are used to list every single transaction that took place during the day, and the list is totaled at the end of the day. These daybooks are not part of the double-entry bookkeeping system. The information recorded in these daybooks is then transferred to the general ledgers, where it is said to be posted. Modern computer software allows for the instant update of each ledger account; for example, when recording a cash receipt in a cash receipts journal a debit is posted to a cash ledger account with a corresponding credit to the ledger account from which the cash was received. Not every single transaction needs to be entered into a T-account; usually only the sum (the batch total) for the day of each book transaction is entered in the general ledger.

The five accounting elements

There are five fundamental elements[13] within accounting. These elements are as follows: Assets, Liabilities, Equity (or Capital), Income (or Revenue) and Expenses. The five accounting elements are all affected in either a positive or negative way. A credit transaction does not always dictate a positive value or increase in a transaction and similarly, a debit does not always indicate a negative value or decrease in a transaction. An asset account is often referred to as a "debit account" due to the account's standard increasing attribute on the debit side. When an asset (e.g. an espresso machine) has been acquired in a business, the transaction will affect the debit side of that asset account illustrated below:

| Asset | |

|---|---|

| Debits (Dr) | Credits (Cr) |

| X | |

The "X" in the debit column denotes the increasing effect of a transaction on the asset account balance (total debits less total credits), because a debit to an asset account is an increase. The asset account above has been added to by a debit value X, i.e. the balance has increased by £X or $X. Likewise, in the liability account below, the X in the credit column denotes the increasing effect on the liability account balance (total credits less total debits), because a credit to a liability account is an increase.

All "mini-ledgers" in this section show standard increasing attributes for the five elements of accounting.

| Liability | |

|---|---|

| Debits (Dr) | Credits (Cr) |

| X | |

| Income | |

|---|---|

| Debits (Dr) | Credits (Cr) |

| X | |

| Expenses | |

|---|---|

| Debits (Dr) | Credits (Cr) |

| X | |

| Equity | |

|---|---|

| Debits (Dr) | Credits (Cr) |

| X | |

Summary table of standard increasing and decreasing attributes for the accounting elements:

| ACCOUNT TYPE | DEBIT | CREDIT |

|---|---|---|

| Asset | + | − |

| Expense | + | − |

| Dividends | + | − |

| Liability | − | + |

| Revenue | − | + |

| Common shares | − | + |

| Retained earnings | − | + |

Attributes of accounting elements per real, personal, and nominal accounts

Real accounts are assets. Personal accounts are liabilities and owners' equity and represent people and entities that have invested in the business. Nominal accounts are revenue, expenses, gains, and losses. Accountants close out accounts at the end of each accounting period.[21] This method is used in the United Kingdom, where it is simply known as the Traditional approach.[14]

Transactions are recorded by a debit to one account and a credit to another account using these three "golden rules of accounting":

- Real account: Debit what comes in and credit what goes out

- Personal account: Debit who receives and Credit who gives.

- Nominal account: Debit all expenses & losses and Credit all incomes & gains

| Account type | Debit | Credit | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Real | Assets | Increase | Decrease |

| Personal | Liability | Decrease | Increase |

| Owner's equity | Decrease | Increase | |

| Nominal | Revenue | Decrease | Increase |

| Expenses | Increase | Decrease | |

| Gain | Decrease | Increase | |

| Loss | Increase | Decrease | |

Principle

This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (October 2014) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

Each transaction that takes place within the business will consist of at least one debit to a specific account and at least one credit to another specific account. A debit to one account can be balanced by more than one credit to other accounts, and vice versa. For all transactions, the total debits must be equal to the total credits and therefore balance.

The general accounting equation is as follows:

- Assets = Equity + Liabilities,[22]

- A = E + L.

The equation thus becomes A – L – E = 0 (zero). When the total debits equals the total credits for each account, then the equation balances.

The extended accounting equation is as follows:

- Assets + Expenses = Equity/Capital + Liabilities + Income,

- A + Ex = E + L + I.

In this form, increases to the amount of accounts on the left-hand side of the equation are recorded as debits, and decreases as credits. Conversely for accounts on the right-hand side, increases to the amount of accounts are recorded as credits to the account, and decreases as debits.

This can also be rewritten in the equivalent form:

- Assets = Liabilities + Equity/Capital + (Income − Expenses),

- A = L + E + (I − Ex),

where the relationship of the Income and Expenses accounts to Equity and profit is a bit clearer.[23] Here Income and Expenses are regarded as temporary or nominal accounts which pertain only to the current accounting period whereas Asset, Liability, and Equity accounts are permanent or real accounts pertaining to the lifetime of the business.[24] The temporary accounts are closed to the Equity account at the end of the accounting period to record profit/loss for the period. Both sides of these equations must be equal (balance).

Each transaction is recorded in a ledger or "T" account, e.g. a ledger account named "Bank" that can be changed with either a debit or credit transaction.

In accounting it is acceptable to draw-up a ledger account in the following manner for representation purposes:

| Bank | |

|---|---|

| Debits (Dr) | Credits (Cr) |

Accounts pertaining to the five accounting elements

Accounts are created/opened when the need arises for whatever purpose or situation the entity may have. For example, if your business is an airline company they will have to purchase airplanes, therefore even if an account is not listed below, a bookkeeper or accountant can create an account for a specific item, such as an asset account for airplanes. In order to understand how to classify an account into one of the five elements, a good understanding of the definitions of these accounts is required. Below are examples of some of the more common accounts that pertain to the five accounting elements:

Asset accounts

Asset accounts are economic resources which benefit the business/entity and will continue to do so.[25] They are Cash, bank, accounts receivable, inventory, land, buildings/plant, machinery, furniture, equipment, supplies, vehicles, trademarks and patents, goodwill, prepaid expenses, prepaid insurance, debtors (people who owe us money, due within one year), VAT input etc.

Two types of basic asset classification:[26]

- Current assets: Assets which operate in a financial year or assets that can be used up, or converted within one year or less are called current assets. For example, Cash, bank, accounts receivable, inventory (people who owe us money, due within one year), prepaid expenses, prepaid insurance, VAT input and many more.

- Non-current assets: Assets that are not recorded in transactions or hold for more than one year or in an accounting period are called Non-current assets. For example, land, buildings/plant, machinery, furniture, equipment, vehicles, trademarks and patents, goodwill etc.

Liability accounts

Liability accounts record debts or future obligations a business or entity owes to others. When one institution borrows from another for a period of time, the ledger of the borrowing institution categorises the argument under liability accounts.[27]

The basic classifications of liability accounts are:

- Current liability, when money only may be owed for the current accounting period or periodical. Examples include accounts payable, salaries and wages payable, income taxes, bank overdrafts, accrued expenses, sales taxes, advance payments (unearned revenue), debt and accrued interest on debt, customer deposits, VAT output, etc.

- Long-term liability, when money may be owed for more than one year. Examples include trust accounts, debenture, mortgage loans and more.

Equity accounts

Equity accounts record the claims of the owners of the business/entity to the assets of that business/entity.[28] Capital, retained earnings, drawings, common stock, accumulated funds, etc.

Income/revenue accounts

Income accounts record all increases in Equity other than that contributed by the owner/s of the business/entity.[29] Services rendered, sales, interest income, membership fees, rent income, interest from investment, recurring receivables, donation etc.

Expense accounts

Expense accounts record all decreases in the owners' equity which occur from using the assets or increasing liabilities in delivering goods or services to a customer – the costs of doing business.[30] Telephone, water, electricity, repairs, salaries, wages, depreciation, bad debts, stationery, entertainment, honorarium, rent, fuel, utility, interest etc.

Example

Quick Services business purchases a computer for £500, on credit, from ABC Computers. Recognize the following transaction for Quick Services in a ledger account (T-account):

Quick Services has acquired a new computer which is classified as an asset within the business. According to the accrual basis of accounting, even though the computer has been purchased on credit, the computer is already the property of Quick Services and must be recognised as such. Therefore, the equipment account of Quick Services increases and is debited:

| Equipment (Asset) | |

|---|---|

| (Dr) | (Cr) |

| 500 | |

As the transaction for the new computer is made on credit, the payable "ABC Computers" has not yet been paid. As a result, a liability is created within the entity's records. Therefore, to balance the accounting equation the corresponding liability account is credited:

| Payable ABC Computers (Liability) | |

|---|---|

| (Dr) | (Cr) |

| 500 | |

The above example can be written in journal form:

| Dr | Cr | |

|---|---|---|

| Equipment | 500 |

|

| ABC Computers (Payable) | 500 |

The journal entry "ABC Computers" is indented to indicate that this is the credit transaction. It is accepted accounting practice to indent credit transactions recorded within a journal.

In the accounting equation form:

- A = E + L,

- 500 = 0 + 500 (the accounting equation is therefore balanced).

Further examples

- A business pays rent with cash: You increase rent (expense) by recording a debit transaction, and decrease cash (asset) by recording a credit transaction.

- A business receives cash for a sale: You increase cash (asset) by recording a debit transaction, and increase sales (income) by recording a credit transaction.

- A business buys equipment with cash: You increase equipment (asset) by recording a debit transaction, and decrease cash (asset) by recording a credit transaction.

- A business borrows with a cash loan: You increase cash (asset) by recording a debit transaction, and increase loan (liability) by recording a credit transaction.

- A business pays salaries with cash: You increase salary (expenses) by recording a debit transaction, and decrease cash (asset) by recording a credit transaction.

- The totals show the net effect on the accounting equation and the double-entry principle, where the transactions are balanced.

| Account | Debit (Dr) | Credit (Cr) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Rent (Ex) | 100 |

|

| Cash (A) | 100 | ||

| 2. | Cash (A) | 50 |

|

| Sales (I) | 50 | ||

| 3. | Equipment (A) | 5200 |

|

| Cash (A) | 5200 | ||

| 4. | Cash (A) | 11000 |

|

| Loan (L) | 11000 | ||

| 5. | Salary (Ex) | 5000 |

|

| Cash (A) | 5000 | ||

| 6. | Total (Dr) | $21350 |

|

| Total (Cr) | $21350 |

T-accounts

The process of using debits and credits creates a ledger format that resembles the letter "T".[31] The term "T-account" is accounting jargon for a "ledger account" and is often used when discussing bookkeeping.[32] The reason that a ledger account is often referred to as a T-account is due to the way the account is physically drawn on paper (representing a "T"). The left column is for debit (Dr) entries, while the right column is for credit (Cr) entries.

| Debits (Dr) | Credits (Cr) |

|---|---|

Contra account

All accounts also can be debited or credited depending on what transaction has taken place. For example, when a vehicle is purchased using cash, the asset account "Vehicles" is debited and simultaneously the asset account "Bank or Cash" is credited due to the payment for the vehicle using cash. Some balance sheet items have corresponding "contra" accounts, with negative balances, that offset them. Examples are accumulated depreciation against equipment, and allowance for bad debts (also known as allowance for doubtful accounts) against accounts receivable.[33] United States GAAP utilizes the term contra for specific accounts only and does not recognize the second half of a transaction as a contra, thus the term is restricted to accounts that are related. For example, sales returns and allowance and sales discounts are contra revenues with respect to sales, as the balance of each contra (a debit) is the opposite of sales (a credit). To understand the actual value of sales, one must net the contras against sales, which gives rise to the term net sales (meaning net of the contras).[34]

A more specific definition in common use is an account with a balance that is the opposite of the normal balance (Dr/Cr) for that section of the general ledger.[34] An example is an office coffee fund: Expense "Coffee" (Dr) may be immediately followed by "Coffee – employee contributions" (Cr).[35] Such an account is used for clarity rather than being a necessary part of GAAP (generally accepted accounting principles).[34]

Accounts classification

Each of the following accounts is either an Asset (A), Contra Account (CA), Liability (L), Shareholders' Equity (SE), Revenue (Rev), Expense (Exp) or Dividend (Div) account.

Account transactions can be recorded as a debit to one account and a credit to another account using the modern or traditional approaches in accounting and following are their normal balances:

| Accounts | A/CA/L/SE/Rev/Exp/Div | Dr/ Cr |

|---|---|---|

| Inventory | A | Dr |

| Wages expense | Exp | Dr |

| Accounts payable | L | Cr |

| Retained earnings | SE | Cr |

| Revenue | Rev | Cr |

| Cost of goods sold | Exp | Dr |

| Accounts receivable | A | Dr |