Category:Roman Catholic churches in the 1st arrondissement of Paris

Pages in category "Roman Catholic churches in the 1st arrondissement of Paris"

The following 7 pages are in this category, out of 7 total. This list may not reflect recent changes.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Roman_Catholic_churches_in_the_1st_arrondissement_of_Paris

Saint-Leu-Saint-Gilles de Paris

| Location | 1st arrondissement of Paris |

|---|---|

| Country | France |

| Denomination | Roman Catholic |

| History | |

| Relics held | Saint Helena |

| Architecture | |

| Heritage designation | Monument historique (1915) |

| Architectural type | church |

| Style | Gothic |

| Groundbreaking | 1235 |

| Completed | 1780 |

The Église Saint-Leu-Saint-Gilles de Paris is a Roman Catholic parish church in the 1st arrondissement of Paris. It has housed the relics of the Empress Saint Helena, mother of Constantine, since 1819, for which it remains a site of veneration in the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches.[1] In 1915 the French Ministry of Culture listed it as a monument of historical value.[2]

History

In the 12th century, a small chapel dedicated to Saint Gilles, a hermit or monk in the Rhone Valley in the 6th century, occupied the site, within the Monastery of Saint-Maggiore, and close to the royal road that led from Paris to the Basilica of Saint-Denis. In 1235 construction began of a new church independent of the monastery, dedicated to Saint Gilles and later also to Saint Lupus of Troyes, or Saint Leu, who was credited at the time with saving Troyes from an attack by Atilla the Hun.[3]

As the population of the neighborhood grew, the church was rebuilt in 1319, and underwent several major renovations and modifications, notably in 1611, 1727, and 1780, when an underground chapel was added.[4] It was closed and badly damaged during the French Revolution, when it was turned into a storehouse for food. It was returned to the church in 1802 under Napoleon Bonaparte.

The Boulevard de Sébastopol was constructed behind the church by then-President and future Emperor Napoleon III, resulting in the demolition of three chapels and the apse. A renovation was carried out by architects Étienne-Hippolyte Godde and Victor Baltard. The church was closed and damaged again during the Paris Commune in 1871, but was restored.

The Knights of the Holy Sepulchre and the reliquary of Saint Helena

In 1780 the Knights of the Order of the Holy Sepulchre, a religious order which had originally been created in 1099 during the Crusades to protect early Christian sites in the Holy Land, established their headquarters in the church. They particulary venerated Saint Helena, the nother of the Emperor Constantine and an important figure in the early history of Christianity. In 1819 the relics of Saint Helena had been transferred to the church from the Abbaye Saint-Pierre d’Hautvillers by the Knights. In 1875, the reliquary of Saint Lupus of Sens was opened in order to carry out an anatomical analysis of the remains of Saint Helena. Based on the medical findings, Monsignor Richard, Archbishop of Paris, announced that the “reliquary contained the almost-complete torso of Saint Helena”, that “the head was missing and the limbs compressed”, and that “the state of the body conserved in the reliquary of the Église Saint-Leu-Saint-Gilles corresponded to the descriptions known to the Bollandistes in the 18th century”. The reliquary was subsequently placed on open display above and behind the high altar, at the feet of the large crucifix, suspended between two pillars of the apse.[5]

The Knights of the Holy Sepulchre moved their headquarters from the church in 1830, but on 16 October 1928, Cardinal Dubois, Archbishop of Paris, held a ceremony in the church for the “Reintegration of the Knights of the Holy Sepulchre”. The building was subsequently made chapter house of that order. The order undertook a new mission to assist the Christian community in the Holy Land.

On 17 March 2000 the relics of Saint Helena were transferred to the crypt of the order’s knights, making them more easily accessible for veneration.[6] The first Eastern Orthodox liturgy was celebrated before the relics of Saint Helena on 22 February 2003.[7]

The church is now managed by the Trinitarian Order. It pays particular attention to the homeless of its neighborhood, Les Halles.

Exterior

The facade on Rue Saint-Denis is distinguished by two high towers, but the rest of the exterior is difficult to see because of the narrow streets. The outer aisles of the nave and choir were added later, and probably replaced earlier external buttresses. The apse of the church was considerably shortened in the 19th century and three chapels were removed to make space for the new boulevard built by Napoleon III.[8]

Interior

The church is built in the Gothic style of the 14th century. This was a period of economic hardship, political conflict, and an outbreak of the black death, or plague in Paris. As a consequence the interior of the church was more austere than earlier or later Gothic churches in Paris.The church’s single nave counts numerous stained-glass windows. It is flanked by aisles, but the church has no transept. pl THe church did not originally have collateral aisles and chapels, which were added in the 16th century. It most likely had external buttresses placed where the collateral aisles are today. The four-part Gothic rib vaults over the nave transfer the weight of the roof downward and outwards to rows of columns, which form arcades with pointed arches.[9]

The present choir, the area of the church where the clergy worship, was constructed in 1611 after a large crypt was built underneath the church. The choir in the Renaissance style, blended with rib vaults and other Gothic elements.[10]

Chapels and the Crypt

Statue of Saint Anne and the Virgin, by Jean Bullant (1515-1578)

The first chapel on the lower aisle on the left side dates from the 16th century, and was originally used for baptisms. It was later given for the exclusive use of the Order of the Knights of the Holy Sepulchre for their ceremonies and meetings. The gilded reliquary in the form of a church, which holds relics of the Saint Helen, is displayed here. The chapel has a very imposing cast iron gate decorated with emblems of the Maltese Cross, the symbol of the Order. The interior is decorated like a formal salon, with murals painted by the 19th-century artist Jean-Louis Bezard (1799-1881) depicting "The Baptism of Christ" and "The Original Sin". These were the last works painted by Bezard, whose paintings was strongly influenced by those of Raphael.[11]

The second chapel displays a work of 16th-centry sculpture by Jean Bullant (1550-1578) , who was better-known as an architect than as a sculptor; his famous buildings included the Château de Chenonceau in the Loire Valley, bridging the River Cher. The statue depicts Saint Anne and education of the Virgin Mary; Mary is a smiling child, holding an apple, while Saint Anne, with a stern face, holds a book.[12]

The Crypt was built beneath the choir in 1780 by architect Charles de Wailly. It was created for the Knights of the Holy Sepulchre, particularly to display the relics of Saint Helen, the mother of the Emperor Constantine, brought to France by the Knights of the Holy Sepulchre. Some of the relics are kept here, with others are in the reliquary of the chapel of the Knights of the Holy Sepulchre on the main floor.[13]

The disambulatory of the church, next to the sacristy, displays an unusual art treasure; a retable with three bas-reliefs made of alabaster, depicting scenes from the life of Christ. They were created in Nottingham, England and date to the 15th century. They illustrate "The Last Supper", "The Kiss of Judas", 'and 'The Flagelation of Christ". THey are made in a small format, designed for display in private oratories and in the altar pieces and retables of churches. According to tradition, these sculotures were originally located in Holy Innocents' Cemetery in Paris, the largest cemetery in Paris until the end of the 18th century.[14]

Stained Glass

Saint Genevieve praying for the defenders of Paris against the Huns

The stained glass windows date to the 19th century, between about 1861 and 1869. They were made by Eugène-Stanislas Oudinot (1827–1889), Prosper Lafaye and Paul Nicod. The windows were damaged during the Paris Commune, but were restored by Henri Chabin between 1875 and 1881.

Alabaster Sculpture

The disambulatory of the church displays an unusual art treasure; a retable with three bas-reliefs made of alabaster, depicting scenes from the life of Christ. They were created in Nottingham, England and date to the 15th century. They illustrate "The Last Supper", "The Kiss of Judas", 'and 'The Flagelation of Christ". THey are made in a small format, designed for display in private oratories and in the altar pieces and retables of churches. According to tradition, these sculptures were originally located in Holy Innocents' Cemetery in Paris, the largest cemetery in Paris until the end of the 18th century.[15]

Organ

The church’s main organ dates to shortly before 1603.[16] It was enlarged between 1637 and 1659 by Guy Jolly, giving it three keyboards and a set of pedals for a total of 27 stops. A fourth keyboard and pedals were added in 1671.

The major part of the present organ was built by François-Henri Clicquot between 1786 and 1783. bringing the number of stops to twenty-eight. It was modified again by Louis Suret in 1855; he preserved most of the Clicquot organ, giving it five keyboards, one new, and an additional three to five stops. The next work was done in 1911 and 1912 by Mutin[17]

The present instrument has three keyboards and a set of pedals, for a total of twenty-five stops.[18] It was protected as an object of historical significance in 1915, and underwent further restoration in 1983[19]

A smaller organ is located in the choir, behind the altar.

See also

References

- Base Palissy: PM75004212, Ministère français de la Culture. (in French)

External links

- [1] Website of the church (in French)

- [2] Description of protected objects in church from French Ministry of Culture

Bibliography (in French)

- Dumoulin, Aline; Ardisson, Alexandra; Maingard, Jérôme; Antonello, Murielle; Églises de Paris (2017), Éditions Massin, Issy-Les-Moulineaux, ISBN 978-2-7072-0683-1 (in French)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saint-Leu-Saint-Gilles_de_Paris

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Italianate_architecture

West facade of Speyer Cathedral, by Heinrich Hübsch (left). The yellow tone of the 19th-century addition contrasts with the reddish tone of the surviving medieval parts behind it.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Romanesque_Revival_architecture

The Romanesque Revival or Norman Revival in Great Britain

The development of the Norman revival style took place over a long time in the British Isles, starting with Inigo Jones's refenestration of the White Tower of the Tower of London in 1637–38 and work at Windsor Castle by Hugh May for King Charles II, but this was little more than restoration work. In the 18th century, the use of round arched windows was thought of as being Saxon rather than Norman, and examples of buildings with round arched windows include Shirburn Castle in Oxfordshire, Wentworth in Yorkshire, and Enmore Castle in Somerset. In Scotland the style started to emerge with the Duke of Argyl's castle at Inverary, started in 1744, and castles by Robert Adam at Culzean (1771), Oxenfoord (1780–82), Dalquharran, (1782–85) and Seton Palace, 1792. In England James Wyatt used round arched windows at Sandleford Priory, Berkshire, in 1780–89 and the Duke of Norfolk started to rebuild Arundel Castle, while Eastnor Castle in Herefordshire was built by Robert Smirke between 1812 and 1820.[5]

At this point, the Norman Revival became a recognisable architectural style. In 1817, Thomas Rickman published his An Attempt to Discriminate the Styles of English Architecture from the Conquest To the Reformation. It was now realised that 'round-arch architecture' was largely Romanesque in the British Isles and came to be described as Norman rather than Saxon.[6] The start of an "archaeologically correct" Norman Revival can be recognised in the architecture of Thomas Hopper. His first attempt at this style was at Gosford Castle in Armagh in Ireland, but far more successful was his Penrhyn Castle near Bangor in North Wales. This was built for the Pennant family, between 1820 and 1837. The style did not catch on for domestic buildings, though many country houses and mock castles were built in the Castle Gothic or Castellated style during the Victorian period, which was a mixed Gothic style.[7]

However, the Norman Revival did catch on for church architecture. Thomas Penson, a Welsh architect, would have been familiar with Hopper's work at Penrhyn, who developed Romanesque Revival church architecture. Penson was influenced by French and Belgian Romanesque Revival architecture, and particularly the earlier Romanesque phase of German Brick Gothic. At St David's Newtown, 1843–47, and St Agatha's Llanymynech, 1845, he copied the tower of St. Salvator's Cathedral, Bruges. Other examples of Romanesque revival by Penson are Christ Church, Welshpool, 1839–1844, and the porch to Langedwyn Church. He was an innovator in his use of Terracotta to produce decorative Romanesque mouldings, saving on the expense of stonework.[8] Penson's last church in the Romanesque Revival style was Rhosllannerchrugog, Wrexham, 1852.[9]

The Romanesque adopted by Penson contrasts with the Italianate Romanesque of other architects such as Thomas Henry Wyatt, who designed Saint Mary and Saint Nicholas Church, in this style at Wilton, which was built between 1841 and 1844 for the Dowager Countess of Pembroke and her son, Lord Herbert of Lea.[10] During the 19th century, the architecture selected for Anglican churches depended on the churchmanship of particular congregations. Whereas high churches and Anglo-Catholic, which were influenced by the Oxford Movement, were built in Gothic Revival architecture, low churches and broad churches of the period were often built in the Romanesque Revival style. Some of the later examples of this Romanesque Revival architecture is seen in Non-conformist or Dissenting churches and chapels. A good example of this is by the Lincoln architects Drury and Mortimer, who designed the Mint Lane Baptist Chapel in Lincoln in a debased Italianate Romanesque revival style in 1870.[11] After about 1870 this style of Church architecture in Britain disappears, but in the early 20th century, the style is succeeded by Byzantine Revival architecture.

Gosford Castle, Armagh by Thomas Hopper

Penrhyn Castle, by Thomas Hopper, 1820–1837

Canada

Two of Canada's provincial legislatures, the Ontario Legislative Building in Toronto and the British Columbia Parliament Buildings in Victoria, are Romanesque Revival in style.

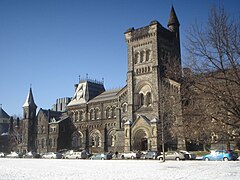

University College, one of seven colleges at the University of Toronto, is an example of the Romanesque Revival style.[12] Construction of the final design began on 4 October 1856.[13]

University College, Toronto, Ontario

Holy Rosary Roman Catholic Cathedral, Regina, Saskatchewan

Sweden

The Vasa Church in Gothenburg, Sweden, is another prime example of the Neo-Romanesque style of architecture.

United States

The Church of the Pilgrims—now the Maronite Cathedral of Our Lady of Lebanon—in Brooklyn Heights, Brooklyn, designed by Richard Upjohn and built 1844–46, is generally considered the first work of Romanesque Revival architecture in the United States.[14] It was soon followed by a more prominent design for the Smithsonian Institution Building in Washington, DC, designed by James Renwick Jr. and built 1847–51. Renwick allegedly submitted two proposals to the design competition, one Gothic and the other Romanesque in the style. The Smithsonian chose the latter, which was based on designs from German architecture books.[15] Several concurrent forces contributed to the popularizing of the Romanesque Revival in the United States. The first was an influx of German immigrants in the 1840s, who brought the style of the Rundbogenstil with them.[15] Second, a series of works on the style was published concurrently with the earliest built examples. The first of these, Hints on Public Architecture, written by social reformer Robert Dale Owen in 1847–48, was prepared for the Building Committee of the Smithsonian Institution and prominently featured illustrations of Renwick's Smithsonian Institution Building. Owen argued that Greek Revival architecture—then the prevailing style in the United States for everything from churches to banks to private residences—was unsuitable as a national American style. He maintained that the Greek temples upon which the style was based had neither the windows, chimneys, nor stairs required by modern buildings, and that the low-pitched temple roofs and tall colonnades were ill-adapted to cold northern climates. To Owen, most Greek Revival buildings thus lacked architectural truth, because they attempted to hide 19th-century necessities behind classical temple facades.[16] In its place, he offered that the Romanesque style was ideal for a more flexible and economic American architecture.[17]

Soon after, the Congregational Church published A Book of Plans for Churches and Parsonages in 1853, containing 18 designs by 10 architects, including Upjohn, Renwick, Henry Austin, and Gervase Wheeler, most in the Romanesque Revival style. Richard Salter Storrs and other clergy on the book's committee were members or frequent preachers of Upjohn's Church of the Pilgrims.[18] St. Joseph Church in Hammond, Indiana, is Romanesque Revival.[19]

The most celebrated "Romanesque Revival" architect of the late 19th century was H. H. Richardson, whose mature style was so individual that it is known as "Richardsonian Romanesque". Among his most prominent buildings are Trinity Church (Boston) and Sever Hall and Austin Hall at Harvard University.

Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception

The Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception is a large Catholic minor basilica and national shrine located in Washington, D.C., United States of America. The shrine is the largest Catholic church in North America, one of the largest churches in the world,[20] and the tallest habitable building in Washington, D.C.[21][22][23] Its construction of Byzantine Revival and Romanesque Revival architecture began on September 23, 1920, with renowned contractor John McShain and was completed on December 8, 2017, with the dedication and solemn blessing of the Trinity Dome mosaic on December 8, 2017, the Feast of the Immaculate Conception, by Cardinal Donald William Wuerl.[24]

The Smithsonian Institution Building, an early example of American Romanesque Revival designed by James Renwick Jr. in 1855

Main building, Illinois Institute of Technology

Bomberger Hall, Ursinus College, Collegeville, Pennsylvania, built in 1891

Barge Hall, Central Washington University, Ellensburg

Basilica of St. Adalbert, Grand Rapids, Michigan, completed in 1913

Scottish Rite Cathedral, Long Beach, California, built in 1926

Gallery

Georgi Rakovski Military Academy, Sofia, Bulgaria

Fisherman's Bastion, Budapest, Hungary

Chapel, Vajdahunyad Castle, Budapest, Hungary

Preston School of Industry, Ione, California

Đakovo Cathedral, Croatia

See also

- Alexander Brown House, Syracuse, New York

- Gothic Revival architecture

- Museum of Early Trades and Crafts

- Romanesque Revival architecture in the United Kingdom

- Richardsonian Romanesque

- Rundbogenstil

- Venetian Gothic

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Romanesque_Revival_architecture

Influences upon Gothic architecture

The Gothic style of architecture was strongly influenced by the Romanesque architecture which preceded it. Why the Gothic style emerged from Romanesque, and what the key influences on its development were, is a difficult problem for which there is a lack of concrete evidence because medieval Gothic architecture was not accompanied by contemporary written theory, in contrast to the 'Renaissance' and its treatises.[1][2] A number of contrasting theories on the origins of Gothic have been advanced: for example, that Gothic emerged organically as a 'rationalist' answer to structural challenges;[3] that Gothic was informed by the methods of medieval Scholastic philosophy;[4] that Gothic was an attempt to imitate heaven and the light referred to in various Biblical passages such as Revelation;[5] that Gothic was 'medieval modernism' deliberately rejecting the 'historicist' forms of classical architecture.[6] Beyond specific theories, the style was also shaped by the specific geographical, political, religious and cultural context of Europe in the 12th century onwards (the 'first' Gothic building is considered to have been St Denis, in France in the 1140s by scholarly consensus[7]).

Political

At the end of the 12th century, Europe was divided into a multitude of city states and kingdoms. The area encompassing modern Germany, southern Denmark, the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, Switzerland, Austria, Czech Republic and much of northern Italy (excluding Venice and Papal States) was nominally part of the Holy Roman Empire, but local rulers exercised considerable autonomy. France, Denmark, Poland, Hungary, Portugal, Scotland, Castile, Aragon, Navarre, and Cyprus were independent kingdoms, as was the Angevin Empire, whose Plantagenet kings ruled England and large domains in what was to become modern France.[8][page needed] Norway came under the influence of England, while the other Scandinavian countries and Poland were influenced by trading contacts with the Hanseatic League. Swabian kings brought the Gothic tradition from Germany to Southern Italy, part of the Norman Kingdom of Sicily, while after the First Crusade the Lusignan kings introduced French Gothic architecture to Cyprus and the Kingdom of Jerusalem.[citation needed]

Throughout Europe at this time there was a rapid growth in trade and an associated growth in towns.[9][page needed][10][page needed] Germany and the Lowlands had large flourishing towns that grew in comparative peace, in trade and competition with each other, or united for mutual weal, as in the Hanseatic League. Civic building was of great importance to these towns as a sign of wealth and pride. England and France remained largely feudal and produced grand domestic architecture for their kings, dukes and bishops, rather than grand town halls for their burghers.[citation needed]

Religious

The Roman Catholic Church prevailed across Western Europe at this time, influencing not only faith but also wealth and power. Bishops were appointed by the feudal lords (kings, dukes and other landowners) and they often ruled as virtual princes over large estates. The early mediaeval periods had seen a rapid growth in monasticism, with several different orders being prevalent and spreading their influence widely. Foremost were the Benedictines whose great abbey churches vastly outnumbered any others in France, Normandy and England.[citation needed] A part of their influence was that towns developed around them and they became centres of culture, learning and commerce.[citation needed] They were the builders of the Abbey of Saint-Denis, and Abbey of Saint-Remi in France.[citation needed] Later Benedictine projects (constructions and renovations) include Rouen's Abbey of Saint-Ouen, the Abbey La Chaise-Dieu, and the choir of Mont Saint-Michel in France. English examples are Westminster Abbey, originally built as a Benedictine order monastic church; and the reconstruction of the Benedictine church at Canterbury.[citation needed]

The Cluniac and Cistercian Orders were prevalent in France, the great monastery at Cluny having established a formula for a well planned monastic site which was then to influence all subsequent monastic building for many centuries.[9][page needed][10][page needed] The Cistercians spread the style as far east and south as Poland and Hungary.[11] Smaller orders such as the Carthusians and Premonstratensians also built some 200 churches, usually near cities.[12]

In the 13th century Francis of Assisi established the Franciscans, or so-called "Grey Friars", a mendicant order. Saint Dominic founded the mendicant Dominicans, in Toulouse and Bologna, were particularly influential in the building of Italy's Gothic churches.[9][page needed][10][page needed]

The Teutonic Order, a military order, spread Gothic art into Pomerania, East Prussia, and the Baltic region.[13]

Geographic

From the 10th to the 13th century, Romanesque architecture had become a pan-European style and manner of construction, affecting buildings in countries as far apart as Ireland, Croatia, Sweden and Sicily. The same wide geographic area was then affected by the development of Gothic architecture, but the acceptance of the Gothic style and methods of construction differed from place to place, as did the expressions of Gothic taste. The proximity of some regions meant that modern country borders do not define divisions of style.[9][page needed] On the other hand, some regions such as England and Spain produced defining characteristics rarely seen elsewhere, except where they have been carried by itinerant craftsmen, or the transfer of bishops.[citation needed] Regional differences that are apparent in the churches of the Romanesque period often become even more apparent in the Gothic.[10][page needed]

The local availability of materials affected both construction and style. In France, limestone was readily available in several grades, the very fine white limestone of Caen being favoured for sculptural decoration.[citation needed] England had coarse limestone and red sandstone as well as dark green Purbeck marble which was often used for architectural features.[citation needed]

In Northern Germany, Netherlands, northern Poland, Denmark, and the Baltic countries local building stone was unavailable but there was a strong tradition of building in brick. The resultant style, Brick Gothic, is called "Backsteingotik" in Germany and Scandinavia and is associated with the Hanseatic League.[citation needed] In Italy, stone was used for fortifications, but brick was preferred for other buildings. Because of the extensive and varied deposits of marble, many buildings were faced in marble, or were left with undecorated façade so that this might be achieved at a later date.[citation needed]

The availability of timber also influenced the style of architecture, with timber buildings prevailing in Scandinavia.[citation needed] Availability of timber affected methods of roof construction across Europe. It is thought that the magnificent hammer-beam roofs of England were devised as a direct response to the lack of long straight seasoned timber by the end of the mediaeval period, when forests had been decimated not only for the construction of vast roofs but also for ship building.[9][page needed][14][page needed]

Romanesque tradition

Gothic architecture grew out of the previous architectural genre, Romanesque. For the most part, there was not a clean break, as there was to be later in Renaissance Florence with the revival of the Classical style in the early 15th century.[citation needed]

By the 12th century, builders throughout Europe developed Romanesque architectural styles (termed Norman architecture in England because of its association with the Norman Conquest).[15] Scholars have focused on categories of Romanesque/Norman building, including the cathedral church, the parish church, the abbey church, the monastery, the castle, the palace, the great hall, the gatehouse, the civic building, the warehouse, and others.[16]

Many architectural features that are associated with Gothic architecture had been developed and used by the architects of Romanesque buildings, particularly in the building of cathedrals and abbey churches. These include ribbed vaults, buttresses, clustered columns, ambulatories, wheel windows, spires, stained glass windows, and richly carved door tympana. These were already features of ecclesiastical architecture before the development of the Gothic style, and all were to develop in increasingly elaborate ways.[17]

It was principally the development of the pointed arch which brought about the change that separates Gothic from Romanesque.[citation needed] This technological change broke the tradition of massive masonry and solid walls penetrated by small openings, replacing it with a style where light appears to triumph over substance.[citation needed] With its use came the development of many other architectural devices, previously put to the test in scattered buildings and then called into service to meet the structural, aesthetic and ideological needs of the new style. These include the flying buttresses, pinnacles and traceried windows.[9]

Eastern Christian, Sasanian, and Islamic Architecture

The pointed arch, one of the defining attributes of Gothic, appears in Late Roman Byzantine architecture and the Sasanian architecture of Iran during late antiquity, although the form had been used earlier, as in the possibly 1st century AD Temple of Bel, Dura Europos in Roman Mesopotamia.[18] In the Roman context it occurred in church buildings in Syria and occasional secular structures, like the Karamagara Bridge in modern Turkey. In Sassanid architecture parabolic and pointed arches were employed in both palace and sacred construction.[19] A very slightly pointed arch built in 549 exists in the apse of the Basilica of Sant'Apollinare in Classe in Ravenna, and slightly more pointed example from a church, built 564 at Qasr Ibn Wardan in Roman Syria.[20] Pointed arches' development may have been influenced by the elliptical and parabolic arches frequently employed in Sasanian buildings using pitched brick vaulting, which obviated any need for wooden centring and which had for millennia been used in Mesopotamia and Syria.[21] The oldest pointed arches in Islamic architecture are in the Dome of the Rock, completed in 691/2, while some others appear in the Great Mosque of Damascus, begun in 705.[22] The Umayyads were responsible for the oldest significantly pointed arches in medieval western Europe, employing them alongside horseshoe arches in the Great Mosque of Cordoba, built from 785 and repeatedly extended.[23] The Abbasid palace at al-Ukhaidir employed pointed arches in 778 as a dominant theme both structural and decorative throughout the façades and vaults of the complex, while the tomb of al-Muntasir, built 862, employed a dome with a pointed arch profile. Abbasid Samarra had many pointed arches, notably its surviving Bab al-ʿAmma (monumental triple gateway). By the 9th century the pointed arch was used in Egypt and North Africa: in the Nilometer at Fustat in 861, the 876 Mosque of Ibn Tulun in Cairo, and the 870s Great Mosque of Kairouan. Through the 8th and 9th centuries, the pointed arch was employed as standard in secular buildings in architecture throughout the Islamic world.[24] The 10th century Aljafería at Zaragoza displays numerous forms of arch, including many pointed arches decorated and elaborated to a level of design sophistication not seen in Gothic architecture for a further two centuries.[23]

Increasing military and cultural contacts with the Muslim world, including the Norman conquest of Islamic Sicily between 1060 and 1090, the Crusades, beginning 1096, and the Islamic presence in Spain, may have influenced medieval Europe's adoption of the pointed arch, although this hypothesis remains controversial.[25] The structural advantages of pointed arches seems first to have been realised in a medieval Latin Christian context at the abbey church known as Cluny III at Cluny Abbey.[26] Begun by abbot Hugh of Cluny in 1089, the great Romanesque church of Cluny III was the largest church in the west when completed in 1130.[27] Kenneth John Conant, who excavated the site of the church's ruins, argued that the architectural innovations of Cluny III were inspired by the Islamic architecture of Sicily via Monte Cassino.[26] The Abbey of Monte Cassino was the foundational community of the Benedictine Order and lay within the Norman Kingdom of Sicily, which at that time was majority Muslim and predominantly Arabic-speaking[citation needed]. The rib vault with pointed arches was used at Lessay Abbey in Normandy in 1098,[28] and at Durham Cathedral in England at about the same time.[29] In those parts of the Western Mediterranean subject to Islamic control or influence, rich regional variants arose, fusing Romanesque, Byzantine and later Gothic traditions with Islamic decorative forms, as seen, for example, in Monreale and Cefalù Cathedrals, the Alcázar of Seville, and Teruel Cathedral.[30][31]

Notes

- The Gothic south tower is surmounted by a Baroque spire.

Citations

- Harvey, L. P. (1992). "Islamic Spain, 1250 to 1500". Chicago : University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-31960-1; Boswell, John (1978). Royal Treasure: Muslim Communities Under the Crown of Aragon in the Fourteenth Century. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-02090-2.

Bibliography

- Bechmann, Roland (2017). Les Racines des Cathédrales (in French). Payot. ISBN 978-2-228-90651-7.

- Burton, Janet B.; Kerr, Julie (2011). The Cistercians in the Middle Ages. Monastic orders. Vol. 4 (Illustrated ed.). Boydell Press. ISBN 9781843836674.

- Bony, Jean (1983). French Gothic Architecture of the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-02831-9.

- Chastel, André (2000). L'Art Français Pré-Moyen Âge Moyen Âge (in French). Paris: Flammarion. ISBN 2-08-012298-3.

- Ching, Francis D.K. (2012). A Visual Dictionary of Architecture (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ISBN 978-0-470-64885-8.

- Clark, W. W.; King, R. (1983). Laon Cathedral, Architecture. Courtauld Institute Illustration Archives. 1. London: Harvey Miller Publishers. ISBN 9780905203553.

- Der Manuelian, Lucy (2001). "Ani: The Fabled Capital of Armenia". In Cowe, S. Peter (ed.). Ani: World Architectural Heritage of a Medieval Armenian Capital. Leuven Sterling. ISBN 978-90-429-1038-6.

- Draper, Peter (2005). "Islam and the West: The Early Use of the Pointed Arch Revisited". Architectural History. 5: 1–20. doi:10.1017/S0066622X00003701. ISSN 0066-622X. JSTOR 40033831. S2CID 194947480.

- Ducher, Robert (1988). Caractéristique des Styles (in French). Flammarion. ISBN 978-2-08-011539-3.

- Fiske, Kimball (1943). The Creation of the Rococo. Philadelphia Museum of Art.

- Fletcher, Banister (2001). A History of Architecture on the Comparative Method. Elsevier Science & Technology. ISBN 978-0-7506-2267-7.

- Garsoïan, Nina G. (2015). "Sirarpie Der Nersessian (1896–1989)". In Damico, Helen (ed.). Medieval Scholarship: Biographical Studies on the Formation of a Discipline: Religion and Art. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-77636-9.

- Giese, Francine; Pawlak, Anna; Thome, Markus (2018). Tomb – Memory – Space: Concepts of Representation in Premodern Christian and Islamic Art (in German). Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. ISBN 9783110517347.

- Grodecki, Louis (1977). Nervi, Luigi (ed.). Gothic Architecture. In collaboration with Anne Prache and Roland Recht, translated from French by I. Mark Paris. Abrams Books. ISBN 978-0-8109-1008-9.

- Harvey, John (1950). The Gothic World, 1100–1600. Batsford. ISBN 978-0-00-255228-8.

- Harvey, John (1974). Châteaux et Cathédrals-L'Art des Batisseurs, L'Encyclopedie de la Civilisation (in French). London: Thames and Hudson.

- Hughes, William; Punter, David; Smith, Andrew (2015). The Encyclopedia of the Gothic. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781119210412.

- Jones, Colin (1999). The Cambridge Illustrated History of France. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-66992-4.

- Lang, David Marshall (1980). Armenia: Cradle of Civilization. Allen & Unwin.

- Martin, G. H.; Highfield, J. R. L. (1997). A history of Merton College, Oxford. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-920183-8.

- Martindale, Andrew (1993). Gothic Art. Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-2-87811-058-6.

- McNamara, Denis (2017). Comprendre l'Art des Églises (in French). Larousse. ISBN 978-2-03-589952-1.

- Mignon, Olivier (2017). Architecture du Patrimoine Française - Abbayes, Églises, Cathédrales et Châteaux (in French). Éditions Ouest-France. ISBN 978-27373-7611-5.

- Mignon, Olivier (2015). Architecture des Cathédrales Gothiques (in French). Éditions Ouest-France. ISBN 978-2-7373-6535-5.

- Mitchell, Ann (1968). Cathedrals of Europe. Great Buildings of the World. Hamlyn. ASIN B0006C19ES.

- Moffat, Fazio & Wodehouse (2003). A World History of Architecture. Laurence King Publishing. ISBN 1-85669-353-8.

- Montagnon, Pierre (2016). La France des Clochers (in French). Editions Telemaque. ISBN 978-2-7533-0307-2.

- Oggins, R.O. (2000). Cathedrals. Metrobooks. Friedman/Fairfax Publishers. ISBN 9781567993462. Retrieved 6 October 2010.

- Pevsner, Nikolaus (1964). An Outline of European Architecture. Pelican Books. ISBN 978-0-14-061613-2.

- Poisson, Georges; Poisson, Olivier (2014). Eugène Viollet-le-Duc (in French). Paris: Picard. ISBN 978-2-7084-0952-1.

- Raeburn, Michael (1980). "The Middle Ages". In Coldstream, Nicola (ed.). Architecture of the Western World. With a foreword by Sir Hugh Casson. Rizzoli International. ISBN 978-0-8478-0349-1.

- Renault, Christophe; Lazé, Christophe (2006). Les Styles de l'architecture et du mobilier (in French). Gisserot. ISBN 978-2-87747-465-8.

- Scott, Robert A. (2003). The Gothic enterprise: a guide to understanding the Medieval cathedral. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-23177-1.

- Stewart, Cecil (1959). History of Architectural Development: Early Christian, Byzantine and Romanesque Architecture. Longman.

- Swaan, Wim (1988). The Gothic Cathedral. Omega Books. ISBN 978-0-907853-48-0.

- Rice, David Talbot (1972). The Appreciation of Byzantine Art. Oxford University Press.

- Texier, Simon (2012). Paris Panorama de l'architecture de l'Antiquité à nos jours (in French). Parigramme. ISBN 978-2-84096-667-8.

- Toman, Rolf (2007). Néoclassicisme et Romantisme. Ulmann. ISBN 978-3-8331-3557-6.

- Vasari, Giorgio (1907). Brown, Gerald Baldwin; Maclehose, Louisa (eds.). Vasari on Technique: Being the Introduction to the Three Arts of Design, Architecture, Sculpture and Painting, Prefixed to the Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors and Architects. J. M. Dent & Co.

- Vasari, Giorgio (1991). The Lives of the Artists. Translated with an introduction and notes by J.C. and P. Bondanella. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-953719-8.

- Viollet-le-Duc, Eugène (1868). Dictionnaire raisonné de l'architecture française du XIe au XVIe siècle. Édition BANCE.

- Watkin, David (1986). A History of Western Architecture. Barrie and Jenkins. ISBN 0-7126-1279-3.

- Wenzler, Claude (2018). Les cathédrales gothiques: Un défi médiéval (in French). Éditions Ouest-France. ISBN 978-2-7373-7712-9.

- "Chartres Cathedral Royal Portal Sculpture". Chartres Cathedral. Chartres Cathedral. 2020. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- Gothic architecture

- Architectural history

- Architectural styles

- European architecture

- Gothic art

- Architecture in England

- Architecture in Italy

- Medieval French architecture

- Catholic architecture

- 12th-century architecture

- 13th-century architecture

- 14th-century architecture

- 15th-century architecture

- 16th-century architecture

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Influences_upon_Gothic_architecture

Storybook architecture

Storybook architecture is a style popularized in the 1920s in England and the United States. Houses built in this style may be referred to as storybook houses.

Description

Much of a building’s Storybook character is expressed in the roof design. The roof is often designed to appear thatched with undulating and uneven shingles applied in waving patterns. Steeply pitched roofs of multiple gables with rolled or pointed eaves are accented with turrets and dovecotes capped with conical roofs.[1]

The storybook style is a nod toward Hollywood design technically called Provincial Revivalism and more commonly called Fairy Tale or Hansel and Gretel. While there is no specific definition of what makes a house storybook style, the main factor may be a sense of playfulness and whimsy. Most seemed snapped out of a craggy old-world village with intentionally uneven roofs, many cobblestone, doors and windows which may look mismatched and odd-shaped. It took a foothold in California, particularly in Los Angeles, during the 1920s and 1930s.[2]

A primary example can be found in the 1927 Montclair, Oakland, firehouse, and in a more traditional English cottage-style in the 1930 Montclair branch library. Idora Park in north Oakland, California, is a four-square-block storybook architecture development begun in 1927 on the grounds of the old amusement park. Other examples in Los Angeles are the Snow White Cottages, designed in 1931 by architect Ben Sherwood; Charlie Chaplin Studios, built in 1919 by architects Meyer & Holler; the Charlie Chaplin Cottages, built in 1923 by Arthur and Nina Zwebell, a husband-and-wife architectural team; and the "Hobbit House" built between 1940 and 1970 by Disney artist Lawrence Joseph.

Architects and examples

The primary architects that worked in this style are Harry Oliver, Ben Sherwood, William R. Yelland, Walter W. Dixon, Hugh W. Comstock, and Carr Jones among many other local architects.

Los Angeles area

A dovecote is a small, decorative shelter for pigeons often built on top of a house. It looks like a receptacle for secret messages from a fairy-tale world, and this whimsy makes up for the fact that no one actually wants pigeons roosting on their house. Dovecotes are especially common in certain parts of the Los Angeles suburbs, on ‘‘storybook ranch’’ homes — houses recast on the exterior to resemble a cottage that one of the Seven Dwarves might live in... as an intern at a historic preservation firm in Sherman Oaks, I was assigned the task of documenting every dovecote within 10 blocks of the office.[3]

Oliver is noted for his Spadena House in Beverly Hills, and the Tam O'Shanter Inn in Atwater Village, Los Angeles. Harry Oliver worked on more than 30 Hollywood films as an art director or set decorator between 1919–1938. The Spadena House, also known as the Witch's House was originally built to function as offices and dressing rooms for Willat Studios, a silent film studio in Culver City. It was moved to Beverly Hills in either 1926 or 1934 (accounts vary) and has served as a private residence since that time. The Tam O'Shanter Inn, also a Storybook building, was designed by Oliver and built in 1922. Harry Oliver was also responsible for Van de Kamp bakery's trademark windmill buildings which were designed during the same time period.

Sherwood is noted for the Snow White Cottages built in 1931 in Los Angeles.

Another example are cupola-topped storybook homes in a lot in Culver City constructed between 1946 and 1970. They are collectively known as the Hobbit Houses.

San Francisco Bay area

William Yelland is noted for his (Thornburg) Normandy Village and Tupper & Reed Music Store, both located in Berkeley. Yelland designed homes in Oakland, Piedmont, Berkeley, San Leandro, Hayward, Woodland, Modesto, Clarksburg, Sacramento, Kensington and San Francisco.

W. W. Dixon is noted for his work with developer R. C. Hillen in creating the Dixon & Hillen catalog of home plans. Dixon is noted for Stonehenge & Stoneleigh villages in Alameda as well as Picardy Drive in Oakland.

Carr Jones is noted for the post office (now Postino Restaurant) in Lafayette. He also designed and built one-of-a-kind homes in Oakland, Berkeley and Piedmont such as the impressive Houvenin House at 85 Wildwood Gardens in Piedmont. He also built the Steve Jobs home in Palo Alto.

Hugh W. Comstock is noted for his "Fairy Tale," storybook architectural style, that has been closely identified with Carmel-by-the-Sea, California.[4]

Gallery

Hugh W. Comstock's The Tuck Box storybook house in Carmel-by-the-Sea, Monterey, California

See also

References

- Grimes, Teresa; Heumann, Leslie. "Historic Context Statement Carmel-by-the-Sea" (PDF). Leslie Heumann and Associates1994. Retrieved 2022-01-18.

Further reading

- Gellner, Arrol; Keister, Douglas (2001). Storybook Style: America's Whimsical Homes of the Twenties. ISBN 0-670-89385-4.

External links

- Oakland California Storybook House neighborhood

- Storybook Style homeowners club maintained by John Robert Marlow

- Thornburg (Normandy) Village, Berkeley, California by Daniella Thompson, Berkeley Architectural Heritage Association

![Temple Neuf, Metz[25]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/62/Metz_Temple_Neuf_R02.jpg/116px-Metz_Temple_Neuf_R02.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment