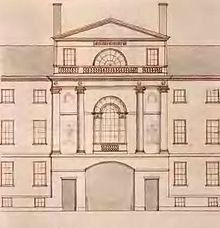

Houghton Hall (/ˈhaʊtən/ HOW-tən)[1] is a country house in the parish of Houghton in Norfolk, England. It is the residence of David Cholmondeley, 7th Marquess of Cholmondeley.[2]

It was commissioned by the de facto first British Prime Minister, Sir Robert Walpole, in 1722, and is a key building in the history of Neo-Palladian architecture in England. It is a Grade I listed building surrounded by 1,000 acres (4.0 km2) of parkland, and is a few miles from Sandringham House.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Houghton_Hall

Palazzo style refers to an architectural style of the 19th and 20th centuries based upon the palazzi (palaces) built by wealthy families of the Italian Renaissance. The term refers to the general shape, proportion and a cluster of characteristics, rather than a specific design; hence it is applied to buildings spanning a period of nearly two hundred years, regardless of date, provided they are a symmetrical, corniced, basemented and with neat rows of windows. "Palazzo style" buildings of the 19th century are sometimes referred to as being of Italianate architecture, but this term is also applied to a much more ornate style, particularly of residences and public buildings.

While early Palazzo style buildings followed the forms and scale of the Italian originals closely, by the late 19th century the style was more loosely adapted and applied to commercial buildings many times larger than the originals. The architects of these buildings sometimes drew their details from sources other than the Italian Renaissance, such as Romanesque and occasionally Gothic architecture. In the 20th century, the style was superficially applied, like the Gothic Revival style, to multi-storey buildings. In the late 20th and 21st century some Postmodern architects have again drawn on the Palazzo style for city buildings.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Palazzo_style_architecture

| 1893 Chicago | |

|---|---|

Chicago World's Columbian Exposition 1893, with The Republic statue and Administration Building | |

| Overview | |

| BIE-class | Universal exposition |

| Category | Historical Expo |

| Name | World's Columbian Exposition |

| Area | 690 acres (280 hectares) |

| Visitors | 27,300,000 |

| Participant(s) | |

| Countries | 46 |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| City | Chicago |

| Venue | Jackson Park and Midway Plaisance |

| Coordinates | 41°47′24″N 87°34′48″W |

| Timeline | |

| Bidding | 1882 |

| Awarded | 1890 |

| Opening | May 1, 1893 |

| Closure | October 30, 1893 |

| Universal expositions | |

| Previous | Exposition Universelle (1889) in Paris |

| Next | Brussels International (1897) in Brussels |

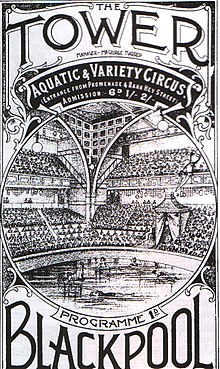

The World's Columbian Exposition (also known as the Chicago World's Fair) was a world's fair held in Chicago in 1893 to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus's arrival in the New World in 1492.[1] The centerpiece of the Fair, held in Jackson Park, was a large water pool representing the voyage Columbus took to the New World. Chicago had won the right to host the fair over several other cities, including New York City, Washington, D.C., and St. Louis. The exposition was an influential social and cultural event and had a profound effect on American architecture, the arts, American industrial optimism, and Chicago's image.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/World%27s_Columbian_Exposition

Bob Vila | |

|---|---|

| Born | June 20, 1946[1] Miami, Florida, U.S. |

| Education | University of Florida (Journalism,[2] 1969) |

| Occupation(s) | Television host entrepreneur |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 3[1] |

| Website | bobvila.com |

Robert Joseph Vila (born June 20, 1946)[1] is an American home improvement television show host known for This Old House (1979–1989), Bob Vila's Home Again (1990–2005), and Bob Vila (2005–2007).

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bob_Vila

| Chester | |

|---|---|

| City | |

Coat of arms | |

Location within Cheshire | |

| Population | 79,645 |

| Demonym | Cestrian |

| OS grid reference | SJ405665 |

| • London | 165 mi (266 km)[1] SE |

| Unitary authority | |

| Ceremonial county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | CHESTER |

| Postcode district | CH1-CH4 |

| Dialling code | 01244 |

| Police | Cheshire |

| Fire | Cheshire |

| Ambulance | North West |

| UK Parliament | |

Chester is a cathedral city and the county town of Cheshire, England, on the River Dee, close to the English–Welsh border. With a population of 79,645 in 2011,[2] it is the most populous settlement of Cheshire West and Chester (a unitary authority which had a population of 329,608 in 2011)[2] and serves as its administrative headquarters. It is also the historic county town of Cheshire and the second-largest settlement in Cheshire after Warrington.

Chester was founded in 79 AD as a "castrum" or Roman fort with the name Deva Victrix during the reign of Emperor Vespasian. One of the main army camps in Roman Britain, Deva later became a major civilian settlement. In 689, King Æthelred of Mercia founded the Minster Church of West Mercia, which later became Chester's first cathedral, and the Angles extended and strengthened the walls to protect the city against the Danes. Chester was one of the last cities in England to fall to the Normans, and William the Conqueror ordered the construction of a castle to dominate the town and the nearby Welsh border. Chester was granted city status in 1541.

The city walls of Chester are some of the best-preserved in the country and have Grade I listed status. It has a number of medieval buildings, but many of the black-and-white buildings within the city centre are Victorian restorations, originating from the Black-and-white Revival movement.[3] Apart from a 100-metre (330 ft) section, the walls are almost complete.[4] The Industrial Revolution brought railways, canals, and new roads to the city, which saw substantial expansion and development; Chester Town Hall and the Grosvenor Museum are examples of Victorian architecture from this period. Tourism, the retail industry, public administration, and financial services are important to the modern economy. Chester signs itself as Chester International Heritage City on road signs on the main roads entering the city.[5]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chester

| London England Temple | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Lua error in Module:Mapframe at line 384: attempt to perform arithmetic on local 'lat_d' (a nil value). | ||||

| Number | 12 | |||

| Dedication | September 7, 1958, by David O. McKay | |||

| Site | 32 acres (13 ha) | |||

| Floor area | 42,652 sq ft (3,962.5 m2) | |||

| Height | 190 ft (58 m) | |||

| Official website • News & images | ||||

| Church chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Additional information | ||||

| Announced | February 17, 1955 | |||

| Groundbreaking | August 27, 1955, by David O. McKay | |||

| Open house | August 16 – September 3, 1958 October 8–14, 1992 | |||

| Rededicated | October 18, 1992, by Gordon B. Hinckley | |||

| Current president | David R. Irwin (2019- ) | |||

| Designed by | Edward O. Anderson | |||

| Location | Newchapel, Surrey, England | |||

| Exterior finish | brick masonry faced with white Portland limestone; the spire is lead-coated copper | |||

| Temple design | Modern contemporary, single spire | |||

| Ordinance rooms | 4 (Movie, stationary rooms) | |||

| Sealing rooms | 7 | |||

| Clothing rental | Yes | |||

| Visitors' center | Yes | |||

| () | ||||

The London England Temple (formerly the London Temple) is the twelfth operating temple of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) and is located in Newchapel, Surrey, England.[1] Despite its name, it is not located within London or Greater London.

The temple serves church members in south Wales, the Channel Islands, southern parts of England, the Limerick District of Ireland, and Jordan.[2]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/London_England_Temple

| White matter | |

|---|---|

Micrograph showing white matter with its characteristic fine meshwork-like appearance (left of image – lighter shade of pink) and grey matter, with the characteristic neuronal cell bodies (right of image – dark shade of pink). HPS stain. | |

Human

brain right dissected lateral view, showing grey matter (the darker

outer parts), and white matter (the inner and prominently whiter parts). | |

| Details | |

| Location | Central nervous system |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | substantia alba |

| MeSH | D066127 |

| TA98 | A14.1.00.009 A14.1.02.024 A14.1.02.201 A14.1.04.101 A14.1.05.102 A14.1.05.302 A14.1.06.201 |

| TA2 | 5366 |

| FMA | 83929 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

White matter refers to areas of the central nervous system (CNS) that are mainly made up of myelinated axons, also called tracts.[1] Long thought to be passive tissue, white matter affects learning and brain functions, modulating the distribution of action potentials, acting as a relay and coordinating communication between different brain regions.[2]

White matter is named for its relatively light appearance resulting from the lipid content of myelin. However, the tissue of the freshly cut brain appears pinkish-white to the naked eye because myelin is composed largely of lipid tissue veined with capillaries. Its white color in prepared specimens is due to its usual preservation in formaldehyde.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/White_matter

| Elizabethan era | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1558–1603 | |||

| |||

| Monarch(s) | Elizabeth I | ||

| Leader(s) |

| ||

| |||

| Periods in English history |

|---|

|

|

| Timeline |

The Elizabethan era is the epoch in the Tudor period of the history of England during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I (1558–1603). Historians often depict it as the golden age in English history. The symbol of Britannia (a female personification of Great Britain) was first used in 1572, and often thereafter, to mark the Elizabethan age as a renaissance that inspired national pride through classical ideals, international expansion, and naval triumph over Spain.

This "golden age"[1] represented the apogee of the English Renaissance and saw the flowering of poetry, music and literature. The era is most famous for its theatre, as William Shakespeare and many others composed plays that broke free of England's past style of theatre. It was an age of exploration and expansion abroad, while back at home, the Protestant Reformation became more acceptable to the people, most certainly after the Spanish Armada was repelled. It was also the end of the period when England was a separate realm before its royal union with Scotland.

The Elizabethan age contrasts sharply with the previous and following reigns. It was a brief period of internal peace between the Wars of the Roses in the previous century, the English Reformation, and the religious battles between Protestants and Catholics prior to Elizabeth's reign, and then the later conflict of the English Civil War and the ongoing political battles between parliament and the monarchy that engulfed the remainder of the seventeenth century. The Protestant/Catholic divide was settled, for a time, by the Elizabethan Religious Settlement, and parliament was not yet strong enough to challenge royal absolutism.

England was also well-off compared to the other nations of Europe. The Italian Renaissance had come to an end following the end of the Italian Wars, which left the Italian Peninsula impoverished. The Kingdom of France was embroiled in the French Wars of Religion (1562–1598). They were (temporarily) settled in 1598 by a policy of tolerating Protestantism with the Edict of Nantes. In part because of this, but also because the English had been expelled from their last outposts on the continent by Spain's tercios, the centuries-long Anglo-French Wars were largely suspended for most of Elizabeth's reign.

The one great rival was Habsburg Spain, with whom England clashed both in Europe and the Americas in skirmishes that exploded into the Anglo-Spanish War of 1585–1604. An attempt by Philip II of Spain to invade England with the Spanish Armada in 1588 was famously defeated. In turn England launched an equally unsuccessful expedition to Spain with the Drake–Norris Expedition of 1589. Three further Spanish Armadas also failed in 1596, 1597 and 1602. The war ended with the Treaty of London the year following Elizabeth's death.

England during this period had a centralised, well-organised, and effective government, largely a result of the reforms of Henry VII and Henry VIII, as well as Elizabeth's harsh punishments for any dissenters. Economically, the country began to benefit greatly from the new era of trans-Atlantic trade and persistent theft of Spanish and Portuguese treasures, most notably as a result of Francis Drake's circumnavigation.

The term Elizabethan era was already well-established in English and British historical consciousness, long before the accession of Queen Elizabeth II, and generally refers solely to the time of the earlier Queen of this name.

Romance and reality

The Victorian era and the early 20th century idealised the Elizabethan era. The Encyclopædia Britannica maintains that "[T]he long reign of Elizabeth I, 1558–1603, was England's Golden Age... 'Merry England', in love with life, expressed itself in music and literature, in architecture and in adventurous seafaring".[2] This idealising tendency was shared by Britain and an Anglophilic America. In popular culture, the image of those adventurous Elizabethan seafarers was embodied in the films of Errol Flynn.[3]

In response and reaction to this hyperbole, modern historians and biographers have tended to take a more dispassionate view of the Tudor period.[4]

Government

Elizabethan England was not particularly successful in a military sense during the period, but it avoided major defeats and built up a powerful navy. On balance, it can be said that Elizabeth provided the country with a long period of general if not total peace and generally increased prosperity due in large part to stealing from Spanish treasure ships, raiding settlements with low defenses, and selling African slaves. Having inherited a virtually bankrupt state from previous reigns, her frugal policies restored fiscal responsibility. Her fiscal restraint cleared the regime of debt by 1574, and ten years later the Crown enjoyed a surplus of £300,000.[5] Economically, Sir Thomas Gresham's founding of the Royal Exchange (1565), the first stock exchange in England and one of the earliest in Europe, proved to be a development of the first importance, for the economic development of England and soon for the world as a whole. With taxes lower than other European countries of the period, the economy expanded; though the wealth was distributed with wild unevenness, there was clearly more wealth to go around at the end of Elizabeth's reign than at the beginning.[6] This general peace and prosperity allowed the attractive developments that "Golden Age" advocates have stressed.[7]

Plots, intrigues, and conspiracies

The Elizabethan Age was also an age of plots and conspiracies, frequently political in nature, and often involving the highest levels of Elizabethan society. High officials in Madrid, Paris and Rome sought to kill Elizabeth, a Protestant, and replace her with Mary, Queen of Scots, a Catholic. That would be a prelude to the religious recovery of England for Catholicism. In 1570, the Ridolfi plot was thwarted. In 1584, the Throckmorton Plot was discovered, after Francis Throckmorton confessed his involvement in a plot to overthrow the Queen and restore the Catholic Church in England. Another major conspiracy was the Babington Plot – the event which most directly led to Mary's execution, the discovery of which involved a double agent, Gilbert Gifford, acting under the direction of Francis Walsingham, the Queen's highly effective spy master.

The Essex Rebellion of 1601 has a dramatic element, as just before the uprising, supporters of the Earl of Essex, among them Charles and Joscelyn Percy (younger brothers of the Earl of Northumberland), paid for a performance of Richard II at the Globe Theatre, apparently with the goal of stirring public ill will towards the monarchy.[8] It was reported at the trial of Essex by Chamberlain's Men actor Augustine Phillips, that the conspirators paid the company forty shillings "above the ordinary" (i. e., above their usual rate) to stage the play, which the players felt was too old and "out of use" to attract a large audience.[8]

In the Bye Plot of 1603, two Catholic priests planned to kidnap King James and hold him in the Tower of London until he agreed to be more tolerant towards Catholics. Most dramatic was the 1605 Gunpowder Plot to blow up the House of Lords during the State Opening of Parliament. It was discovered in time with eight conspirators executed, including Guy Fawkes, who became the iconic evil traitor in English lore.[9]

While Henry VIII had launched the Royal Navy, Edward and Mary had ignored it and it was little more than a system of coastal defense. Elizabeth made naval strength a high priority.[10] She risked war with Spain by supporting the "Sea Dogs", such as John Hawkins and Francis Drake, who preyed on the Spanish merchant ships carrying gold and silver from the New World. The Navy yards were leaders in technical innovation, and the captains devised new tactics. Parker (1996) argues that the full-rigged ship was one of the greatest technological advances of the century and permanently transformed naval warfare. In 1573 English shipwrights introduced designs, first demonstrated in the "Dreadnaught", that allowed the ships to sail faster and maneuver better and permitted heavier guns.[11] Whereas before warships had tried to grapple with each other so that soldiers could board the enemy ship, now they stood off and fired broadsides that would sink the enemy vessel. When Spain finally decided to invade and conquer England it was a fiasco. Superior English ships and seamanship foiled the invasion and led to the destruction of the Spanish Armada in 1588, marking the high point of Elizabeth's reign. Technically, the Armada failed because Spain's over-complex strategy required coordination between the invasion fleet and the Spanish army on shore. Moreover, the poor design of the Spanish cannons meant they were much slower in reloading in a close-range battle. Spain and France still had stronger fleets, but England was catching up.[12]

Parker has speculated on the dire consequences if the Spanish had landed their invasion army in 1588. He argues that the Spanish army was larger, more experienced, better-equipped, more confident, and had better financing. The English defenses, on the other hand, were thin and outdated; England had too few soldiers and they were at best only partially trained. Spain had chosen England's weakest link and probably could have captured London in a week. Parker adds that a Catholic uprising in the north and in Ireland could have brought total defeat.[13]

Colonising the New World

The discoveries of Christopher Columbus electrified all of western Europe, especially maritime powers like England. King Henry VII commissioned John Cabot to lead a voyage to find a northern route to the Spice Islands of Asia; this began the search for the North West Passage. Cabot sailed in 1497 and reached Newfoundland.[14] He led another voyage to the Americas the following year, but nothing was heard of him or his ships again.[15]

In 1562 Elizabeth sent privateers Hawkins and Drake to seize booty from Spanish and Portuguese ships off the coast of West Africa.[16] When the Anglo-Spanish Wars intensified after 1585, Elizabeth approved further raids against Spanish ports in the Americas and against shipping returning to Europe with treasure.[17] Meanwhile, the influential writers Richard Hakluyt and John Dee were beginning to press for the establishment of England's own overseas empire. Spain was well established in the Americas, while Portugal, in union with Spain from 1580, had an ambitious global empire in Africa, Asia and South America. France was exploring North America.[18] England was stimulated to create its own colonies, with an emphasis on the West Indies rather than in North America.

Martin Frobisher landed at Frobisher Bay on Baffin Island in August 1576; He returned in 1577, claiming it in Queen Elizabeth's name, and in a third voyage tried but failed to found a settlement in Frobisher Bay.[19][20]

From 1577 to 1580, Francis Drake circumnavigated the globe. Combined with his daring raids against the Spanish and his great victory over them at Cádiz in 1587, he became a famous hero[21]—his exploits are still celebrated—but England did not follow up on his claims.[22] In 1583, Humphrey Gilbert sailed to Newfoundland, taking possession of the harbour of St. John's together with all land within two hundred leagues to the north and south of it.[23]

In 1584, the queen granted Walter Raleigh a charter for the colonisation of Virginia; it was named in her honour. Raleigh and Elizabeth sought both immediate riches and a base for privateers to raid the Spanish treasure fleets. Raleigh sent others to found the Roanoke Colony; it remains a mystery why the settlers all disappeared.[24] In 1600, the queen chartered the East India Company in an attempt to break the Spanish and Portuguese monopoly of far Eastern trade.[25] It established trading posts, which in later centuries evolved into British India, on the coasts of what is now India and Bangladesh. Larger scale colonisation to North America began shortly after Elizabeth's death.[26]

Distinctions

England in this era had some positive aspects that set it apart from contemporaneous continental European societies. Torture was rare, since the English legal system reserved torture only for capital crimes like treason[27]—though forms of corporal punishment, some of them extreme, were practised. The persecution of witches began in 1563, and hundreds were executed, although there was nothing like the frenzy on the Continent.[28] Mary had tried her hand at an aggressive anti-Protestant Inquisition and was hated for it; it was not to be repeated.[29] Nevertheless, more Catholics were persecuted, exiled, and burned alive than under Queen Mary.[30][31]

Religion

Elizabeth managed to moderate and quell the intense religious passions of the time. This was in significant contrast to previous and succeeding eras of marked religious violence.[32]

Elizabeth said "I have no desire to make windows into men's souls". Her desire to moderate the religious persecutions of previous Tudor reigns – the persecution of Catholics under Edward VI, and of Protestants under Mary I – appears to have had a moderating effect on English society. Elizabeth, Protestant, but undogmatic one,[33] reinstated the 1552 Book of Common Prayer with modifications which made clear that the Church of England believed in the (spiritual) Real Presence of Christ in the Holy Communion but without a definition how in favor of leaving this a mystery, and she had the Black Rubric removed from the Articles of Faith: this had allowed kneeling to receive communion without implying that by doing so it meant the real and essential presence of Christ in the bread and wine: she believed it so. She was not able to get an unmarried clergy or the Protestant Holy Communion celebrated to look like a Mass,.[34] The Apostolic Succession was maintained, the institution of the church continued without a break (with 98% of the clergy remaining at their posts) and the attempt to ban music in church was defeated. The Injunctions of 1571 forbade any doctrines that did not conform to the teaching of the Church Fathers and the Catholic Bishops. The Queen's hostility to strict Calvinistic doctrines blocked the Radicals.

Almost no original theological thought came out of the English Reformation; instead, the Church relied on the Catholic Consensus of the first Four Ecumenical Councils. The preservation of many Catholic doctrines and practices was the cuckoos nest that eventually resulted in the formation of the Via Media during the 17th century.[35] She spent the rest of her reign ferociously fending off radical reformers and Roman Catholics who wanted to modify the Settlement of Church affairs: The Church of England was Protestant, "with its peculiar arrested development in Protestant terms, and the ghost which it harboured of an older world of Catholic traditions and devotional practice".[36]

For a number of years, Elizabeth refrained from persecuting Catholics because she was against Catholicism, not her Catholic subjects if they made no trouble. In 1570, Pope Pius V declared Elizabeth a heretic who was not the legitimate queen and that her subjects no longer owed her obedience. The pope sent Jesuits and seminarians to secretly evangelize and support Catholics. After several plots to overthrow her, Catholic clergy were mostly considered to be traitors, and were pursued aggressively in England. Often priests were tortured or executed after capture unless they cooperated with the English authorities. People who publicly supported Catholicism were excluded from the professions; sometimes fined or imprisoned.[31] This was justified on the grounds that Catholics were not persecuted for their religion but punished for being traitors who supported the Queen's Spanish foe; in practice, however, Catholics perceived it as religious persecution and regarded those executed as martyrs.

Science, technology, and exploration

Lacking a dominant genius or a formal structure for research (the following century had both Sir Isaac Newton and the Royal Society), the Elizabethan era nonetheless saw significant scientific progress. The astronomers Thomas Digges and Thomas Harriot made important contributions; William Gilbert published his seminal study of magnetism, De Magnete, in 1600. Substantial advancements were made in the fields of cartography and surveying. The eccentric but influential John Dee also merits mention.

Much of this scientific and technological progress related to the practical skill of navigation. English achievements in exploration were noteworthy in the Elizabethan era. Sir Francis Drake circumnavigated the globe between 1577 and 1581, and Martin Frobisher explored the Arctic. The first attempt at English settlement of the eastern seaboard of North America occurred in this era—the abortive colony at Roanoke Island in 1587.

While Elizabethan England is not thought of as an age of technological innovation, some progress did occur. In 1564 Guilliam Boonen came from the Netherlands to be Queen Elizabeth's first coach-builder —thus introducing the new European invention of the spring-suspension coach to England, as a replacement for the litters and carts of an earlier transportation mode. Coaches quickly became as fashionable as sports cars in a later century; social critics, especially Puritan commentators, noted the "diverse great ladies" who rode "up and down the countryside" in their new coaches.[37]

Social history

Historians since the 1960s have explored many facets of the social history, covering every class of the population.[38]

Health

Although home to only a small part of the population the Tudor municipalities were overcrowded and unhygienic. Most towns were unpaved with poor public sanitation. There were no sewers or drains, and rubbish was simply abandoned in the street. Animals such as rats thrived in these conditions. In larger towns and cities, such as London, common diseases arising from lack of sanitation included smallpox, measles, malaria, typhus, diphtheria, scarlet fever, and chickenpox.[39]

Outbreaks of the Black Death pandemic occurred in 1498, 1535, 1543, 1563, 1589 and 1603. The reason for the speedy spread of the disease was the increase of rats infected by fleas carrying the disease.[40]

Child mortality was low in comparison with earlier and later periods, at about 150 or fewer deaths per 1000 babies.[41] By age 15 a person could expect 40–50 more years of life.[42]

Homes and dwelling

The great majority were tenant farmers who lived in small villages. Their homes were, as in earlier centuries, thatched huts with one or two rooms, although later on during this period, roofs were also tiled. Furniture was basic, with stools being commonplace rather than chairs.[39] The walls of Tudor houses were often made from timber and wattle and daub, or brick; stone and tiles were more common in the wealthier homes. The daub was usually then painted with limewash, making it white, and the wood was painted with black tar to prevent rotting, but not in Tudor times; the Victorians did this afterwards. The bricks were handmade and thinner than modern bricks. The wooden beams were cut by hand, which makes telling the difference between Tudor houses and Tudor-style houses easy, as the original beams are not straight. The upper floors of Tudor houses were often larger than the ground floors, which would create an overhang (or jetty). This would create more floor-surface above while also keeping maximum street width. During the Tudor period, the use of glass when building houses was first used, and became widespread. It was very expensive and difficult to make, so the panes were made small and held together with a lead lattice, in casement windows. People who could not afford glass often used polished horn, cloth or paper. Tudor chimneys were tall, thin, and often decorated with symmetrical patterns of molded or cut brick. Early Tudor houses, and the homes of poorer people, did not have chimneys. The smoke in these cases would be let out through a simple hole in the roof.

Mansions had many chimneys for the many fireplaces required to keep the vast rooms warm. These fires were also the only way of cooking food. Wealthy Tudor homes needed many rooms, where a large number of guests and servants could be accommodated, fed and entertained. Wealth was demonstrated by the extensive use of glass. Windows became the main feature of Tudor mansions, and were often a fashion statement. Mansions were often designed to a symmetrical plan; "E" and "H" shapes were popular.[43]

Cities

The population of London increased from 100,000 to 200,000 between the death of Mary Tudor in 1558 and the death of Elizabeth I in 1603. Inflation was rapid and the wealth gap was wide. Poor men, women, and children begged in the cities, as the children only earned sixpence a week. With the growth of industry, many landlords decided to use their land for manufacturing purposes, displacing the farmers who lived and worked there. Despite the struggles of the lower class, the government tended to spend money on wars and exploration voyages instead of on welfare.

Poverty

About one-third of the population lived in poverty, with the wealthy expected to give alms to assist the impotent poor.[44] Tudor law was harsh on the able-bodied poor, i.e., those unable to find work. Those who left their parishes in order to locate work were termed vagabonds and could be subjected to punishments, including whipping and putting at the stocks.[45][46]

The idea of the workhouse for the able-bodied poor was first suggested in 1576.[47]

Education

There was an unprecedented expansion of education in the Tudor period. Until then, few children went to school.[48] Those that did go were mainly the sons of wealthy or ambitious fathers who could afford to pay the attendance fee. Boys were allowed to go to school and began at the age of 4, they then moved to grammar school when they were 7 years old. Girls were either kept at home by their parents to help with housework or sent out to work to bring money in for the family. They were not sent to school. Boys were educated for work and the girls for marriage and running a household so when they married they could look after the house and children.[49] Wealthy families hired a tutor to teach the boys at home. Many Tudor towns and villages had a parish school where the local vicar taught boys to read and write. Brothers could teach their sisters these skills. At school, pupils were taught English, Latin, Greek, catechism and arithmetic. The pupils practised writing in ink by copying the alphabet and the Lord's Prayer. There were few books, so pupils read from hornbooks instead. These wooden boards had the alphabet, prayers or other writings pinned to them and were covered with a thin layer of transparent cow's horn. There were two types of school in Tudor times: petty school was where young boys were taught to read and write; grammar school was where abler boys were taught English and Latin.[50] It was usual for students to attend six days a week. The school day started at 7:00 am in winter and 6:00 am in summer and finished about 5:00 pm. Petty schools had shorter hours, mostly to allow poorer boys the opportunity to work as well. Schools were harsh and teachers were very strict, often beating pupils who misbehaved.[51]

Education would begin at home, where children were taught the basic etiquette of proper manners and respecting others.[52] It was necessary for boys to attend grammar school, but girls were rarely allowed in any place of education other than petty schools, and then only with a restricted curriculum.[52] Petty schools were for all children aged from 5 to 7 years of age. Only the most wealthy people allowed their daughters to be taught, and only at home. During this time, endowed schooling became available. This meant that even boys of very poor families were able to attend school if they were not needed to work at home, but only in a few localities were funds available to provide support as well as the necessary education scholarship.[53]

Boys from wealthy families were taught at home by a private tutor. When Henry VIII shut the monasteries he closed their schools. He refounded many former monastic schools—they are known as "King's schools" and are found all over England. During the reign of Edward VI many free grammar schools were set up to take in non-fee paying students. There were two universities in Tudor England: Oxford and Cambridge. Some boys went to university at the age of about 14.[54]

Food

Availability

England's food supply was plentiful throughout most of the reign; there were no famines. Bad harvests caused distress, but they were usually localized. The most widespread came in 1555–57 and 1596–98.[55] In the towns the price of staples was fixed by law; in hard times the size of the loaf of bread sold by the baker was smaller.[56]

Trade and industry flourished in the 16th century, making England more prosperous and improving the standard of living of the upper and middle classes. However, the lower classes did not benefit much and did not always have enough food. As the English population was fed by its own agricultural produce, a series of bad harvests in the 1590s caused widespread starvation and poverty. The success of the wool trading industry decreased attention on agriculture, resulting in further starvation of the lower classes. Cumbria, the poorest and most isolated part of England, suffered a six-year famine beginning in 1594. Diseases and natural disasters also contributed to the scarce food supply.[57]

In the 17th century, the food supply improved. England had no food crises from 1650 to 1725, a period when France was unusually vulnerable to famines. Historians point out that oat and barley prices in England did not always increase following a failure of the wheat crop, but did do so in France.[58]

England was exposed to new foods (such as the potato imported from South America), and developed new tastes during the era. The more prosperous enjoyed a wide variety of food and drink, including exotic new drinks such as tea, coffee, and chocolate. French and Italian chefs appeared in the country houses and palaces bringing new standards of food preparation and taste. For example, the English developed a taste for acidic foods—such as oranges for the upper class—and started to use vinegar heavily. The gentry paid increasing attention to their gardens, with new fruits, vegetables and herbs; pasta, pastries, and dried mustard balls first appeared on the table. The apricot was a special treat at fancy banquets. Roast beef remained a staple for those who could afford it. The rest ate a great deal of bread and fish. Every class had a taste for beer and rum.[59]

Diet

The diet in England during the Elizabethan era depended largely on social class. Bread was a staple of the Elizabethan diet, and people of different statuses ate bread of different qualities. The upper classes ate fine white bread called manchet, while the poor ate coarse bread made of barley or rye.

- Diet of the lower class

The poorer among the population consumed a diet largely of bread, cheese, milk, and beer, with small portions of meat, fish and vegetables, and occasionally some fruit. Potatoes were just arriving at the end of the period, and became increasingly important. The typical poor farmer sold his best products on the market, keeping the cheap food for the family. Stale bread could be used to make bread puddings, and bread crumbs served to thicken soups, stews, and sauces.[60]

- Diet of the middle class

At a somewhat higher social level families ate an enormous variety of meats, who could choose among venison, beef, mutton, veal, pork, lamb, fowl, salmon, eel, and shellfish. The holiday goose was a special treat. Rich spices were used by the wealthier people to offset the smells of old salt-preserved meat. Many rural folk and some townspeople tended a small garden which produced vegetables such as asparagus, cucumbers, spinach, lettuce, beans, cabbage, turnips, radishes, carrots, leeks, and peas, as well as medicinal and flavoring herbs. Some grew their own apricots, grapes, berries, apples, pears, plums, strawberries, currants, and cherries. Families without a garden could trade with their neighbors to obtain vegetables and fruits at low cost. Fruits and vegetables were used in desserts such as pastries, tarts, cakes, crystallized fruit, and syrup.[61][62]

- Diet of the upper class

At the rich end of the scale the manor houses and palaces were awash with large, elaborately prepared meals, usually for many people and often accompanied by entertainment. The upper classes often celebrated religious festivals, weddings, alliances and the whims of the king or queen. Feasts were commonly used to commemorate the "procession" of the crowned heads of state in the summer months, when the king or queen would travel through a circuit of other nobles' lands both to avoid the plague season of London, and alleviate the royal coffers, often drained through the winter to provide for the needs of the royal family and court. This would include a few days or even a week of feasting in each noble's home, who depending on his or her production and display of fashion, generosity and entertainment, could have his way made in court and elevate his or her status for months or even years.

Among the rich private hospitality was an important item in the budget. Entertaining a royal party for a few weeks could be ruinous to a nobleman. Inns existed for travellers, but restaurants were not known.

Special courses after a feast or dinner which often involved a special room or outdoor gazebo (sometimes known as a folly) with a central table set with dainties of "medicinal" value to help with digestion. These would include wafers, comfits of sugar-spun anise or other spices, jellies and marmalades (a firmer variety than we are used to, these would be more similar to our gelatin jigglers), candied fruits, spiced nuts and other such niceties. These would be eaten while standing and drinking warm, spiced wines (known as hypocras) or other drinks known to aid in digestion. Sugar in the Middle Ages or Early Modern Period was often considered medicinal, and used heavily in such things. This was not a course of pleasure, though it could be as everything was a treat, but one of healthful eating and abetting the digestive capabilities of the body. It also, of course, allowed those standing to show off their gorgeous new clothes and the holders of the dinner and banquet to show off the wealth of their estate, what with having a special room just for banqueting.

Gender

While the Tudor era presents an abundance of material on the women of the nobility—especially royal wives and queens—historians have recovered scant documentation about the average lives of women. There has, however, been extensive statistical analysis of demographic and population data which includes women, especially in their childbearing roles.[63] The role of women in society was, for the historical era, relatively unconstrained; Spanish and Italian visitors to England commented regularly, and sometimes caustically, on the freedom that women enjoyed in England, in contrast to their home cultures. England had more well-educated upper-class women than was common anywhere in Europe.[64][65]

The Queen's marital status was a major political and diplomatic topic. It also entered into the popular culture. Elizabeth's unmarried status inspired a cult of virginity. In poetry and portraiture, she was depicted as a virgin or a goddess or both, not as a normal woman.[66] Elizabeth made a virtue of her virginity: in 1559, she told the Commons, "And, in the end, this shall be for me sufficient, that a marble stone shall declare that a queen, having reigned such a time, lived and died a virgin".[67] Public tributes to the Virgin by 1578 acted as a coded assertion of opposition to the queen's marriage negotiations with the Duc d'Alençon.[68]

In contrast to her father's emphasis on masculinity and physical prowess, Elizabeth emphasized the maternalism theme, saying often that she was married to her kingdom and subjects. She explained "I keep the good will of all my husbands – my good people – for if they did not rest assured of some special love towards them, they would not readily yield me such good obedience",[69] and promised in 1563 they would never have a more natural mother than she.[70] Coch (1996) argues that her figurative motherhood played a central role in her complex self-representation, shaping and legitimating the personal rule of a divinely appointed female prince.[71]

Marriage

Over ninety percent of English women (and adults, in general) entered marriage at the end of the 1500s and beginning of the 1600s, at an average age of about 25–26 years for the bride and 27–28 years for the groom, with the most common ages being 25–26 for grooms (who would have finished their apprenticeships around this age) and 23 for brides.[72][73][74] Among the nobility and gentry, the average was around 19–21 for brides and 24–26 for grooms.[75] Many city and townswomen married for the first time in their thirties and forties[76] and it was not unusual for orphaned young women to delay marriage until the late twenties or early thirties to help support their younger siblings,[77] and roughly a quarter of all English brides were pregnant at their weddings.[78]

High culture

Theatre

With William Shakespeare at his peak, as well as Christopher Marlowe and many other playwrights, actors and theatres constantly busy, the high culture of the Elizabethan Renaissance was best expressed in its theatre. Historical topics were especially popular, not to mention the usual comedies and tragedies.[79]

Literature

Elizabethan literature is considered one of the "most splendid" in the history of English literature. In addition to drama and the theatre, it saw a flowering of poetry, with new forms like the sonnet, the Spenserian stanza, and dramatic blank verse, as well as prose, including historical chronicles, pamphlets, and the first English novels. Edmund Spenser, Richard Hooker, and John Lyly, as well as Marlowe and Shakespeare, are major Elizabethan writers.[80]

Music

Travelling musicians were in great demand at Court, in churches, at country houses, and at local festivals. Important composers included William Byrd (1543–1623), John Dowland (1563–1626) Thomas Campion (1567–1620), and Robert Johnson (c. 1583–c. 1634). The composers were commissioned by church and Court, and deployed two main styles, madrigal and ayre.[81] The popular culture showed a strong interest in folk songs and ballads (folk songs that tell a story). It became the fashion in the late 19th century to collect and sing the old songs.[82]

Fine arts

It has often been said that the Renaissance came late to England, in contrast to Italy and the other states of continental Europe; the fine arts in England during the Tudor and Stuart eras were dominated by foreign and imported talent—from Hans Holbein the Younger under Henry VIII to Anthony van Dyck under Charles I. Yet within this general trend, a native school of painting was developing. In Elizabeth's reign, Nicholas Hilliard, the Queen's "limner and goldsmith", is the most widely recognized figure in this native development; but George Gower has begun to attract greater notice and appreciation as knowledge of him and his art and career has improved.[83]

Popular culture

Pastimes

The Annual Summer Fair and other seasonal fairs such as May Day were often bawdy affairs.

Watching plays became very popular during the Tudor period. Most towns sponsored plays enacted in town squares followed by the actors using the courtyards of taverns or inns (referred to as inn-yards) followed by the first theatres (great open-air amphitheatres and then the introduction of indoor theatres called playhouses). This popularity was helped by the rise of great playwrights such as William Shakespeare and Christopher Marlowe using London theatres such as the Globe Theatre. By 1595, 15,000 people a week were watching plays in London. It was during Elizabeth's reign that the first real theatres were built in England. Before theatres were built, actors travelled from town to town and performed in the streets or outside inns.[84]

Miracle plays were local re-enactments of stories from the Bible. They derived from the old custom of mystery plays, in which stories and fables were enacted to teach lessons or educate about life in general. They influenced Shakespeare.[85]

Festivals were popular seasonal entertainments.[86]

Sports

There were many different types of Elizabethan sports and entertainment. Animal sports included bear and bull baiting, dog fighting and cock fighting.

The rich enjoyed tennis, fencing, and jousting. Hunting was strictly limited to the upper class. They favoured their packs of dogs and hounds trained to chase foxes, hares and boars. The rich also enjoyed hunting small game and birds with hawks, known as falconry.

Jousting

Jousting was an upscale, very expensive sport where warriors on horseback raced toward each other in full armor trying to use their lance to knock the other off his horse. It was a violent sport--King Henry II of France was killed in a tournament in 1559, as were many lesser men. King Henry VIII was a champion; he finally retired from the lists after a hard fall left him unconscious for hours.[87]

Other sports included archery, bowling, hammer-throwing, quarter-staff contests, troco, quoits, skittles, wrestling and mob football.

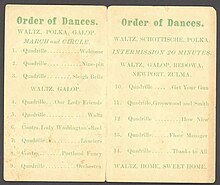

Gambling and card games

Dice was a popular activity in all social classes. Cards appeared in Spain and Italy about 1370, but they probably came from Egypt. They began to spread throughout Europe and came into England around 1460. By the time of Elizabeth's reign, gambling was a common sport. Cards were not played only by the upper class. Many of the lower classes had access to playing cards. The card suits tended to change over time. The first Italian and Spanish decks had the same suits: Swords, Batons/ Clubs, Cups, and Coins. The suits often changed from country to country. England probably followed the Latin version, initially using cards imported from Spain but later relying on more convenient supplies from France.[88] Most of the decks that have survived use the French Suit: Spades, Hearts, Clubs, and Diamonds. Yet even before Elizabeth had begun to reign, the number of cards had been standardized to 52 cards per deck. The lowest court subject in England was called the "knave". The lowest court card was therefore called the knave until later when the term "Jack" became more common. Popular card games included Maw, One and Thirty, Bone-ace. (These are all games for small group players.) Ruff and Honors was a team game.

Festivals, holidays and celebrations

During the Elizabethan era, people looked forward to holidays because opportunities for leisure were limited, with time away from hard work being restricted to periods after church on Sundays. For the most part, leisure and festivities took place on a public church holy day. Every month had its own holiday, some of which are listed below:

- The first Monday after Twelfth Night of January (any time between 7 January and 14 January) was Plough Monday. It celebrated returning to work after the Christmas celebrations and the New Year.

- 2 February: Candlemas. Although often still very cold, Candlemas was celebrated as the first day of spring. All Christmas decorations were burned on this day, in candlelight and torchlight processions.

- 14 February: Valentine's Day.

- Between 3 March and 9 March: Shrove Tuesday (known as Mardi Gras

or Carnival on the Continent). On this day, apprentices were allowed to

run amok in the city in mobs, wreaking havoc, because it supposedly

cleansed the city of vices before Lent.

The day after Shrove Tuesday was Ash Wednesday, the first day of Lent when all were to abstain from eating and drinking certain things.

24 March: Lady Day or the feast of the Annunciation, the first of the Quarter Days on which rents and salaries were due and payable. It was a legal New Year when courts of law convened after a winter break, and it marked the supposed moment when the Angel Gabriel came to announce to the Virgin Mary that she would bear a child. - 1 May: May Day, celebrated as the first day of summer. This was one of the few Celtic festivals with no connection to Christianity and patterned on Beltane. It featured crowning a May Queen, a Green Man and dancing around a maypole.

- 21 June: Midsummer (Christianized as the feast of John the Baptist) and another Quarter Day.

- 1 August: Lammastide, or Lammas Day. Traditionally, the first day of August, in which it was customary to bring a loaf of bread to the church.

- 29 September: Michaelmas. Another Quarter Day. Michaelmas celebrated the beginning of autumn, and Michael the Archangel.

- 25 October: St. Crispin's Day. Bonfires, revels, and an elected 'King Crispin' were all featured in this celebration. Dramatized by Shakespeare in Henry V.

28 October: The Lord Mayor's Show, which still takes place today in London.

31 October: All Hallows Eve or Halloween. The beginning celebration of the days of the dead. - 1 November: All Hallows or All Saints' Day, followed by All Souls' Day.

- 17 November: Accession Day or Queen's Day, the anniversary of Queen Elizabeth's accession to the throne, celebrated with lavish court festivities featuring jousting during her lifetime and as a national holiday for dozens of years after her death.[89]

- 24 December: The Twelve Days of Christmas started at sundown and lasted until Epiphany on 6 January. Christmas was the last of the Quarter Days for the year.

See also

References

- Hutton 1994, p. 146–151

Further reading

- Arnold, Janet: Queen Elizabeth's Wardrobe Unlock'd (W S Maney and Son Ltd, Leeds, 1988) ISBN 0-901286-20-6

- Ashelford, Jane. The Visual History of Costume: The Sixteenth Century. 1983 edition (ISBN 0-89676-076-6)

- Bergeron, David, English Civic Pageantry, 1558–1642 (2003)

- Black, J. B. The Reign of Elizabeth: 1558–1603 (2nd ed. 1958) survey by leading scholar

- Braddick, Michael J. The nerves of state: taxation and the financing of the English state, 1558–1714 (Manchester University Press, 1996).

- Digby, George Wingfield. Elizabethan Embroidery. New York: Thomas Yoseloff, 1964.

- Elton, G.R. Modern Historians on British History 1485–1945: A Critical Bibliography 1945–1969 (1969), annotated guide to history books on every major topic, plus book reviews and major scholarly articles; pp 26–50, 163–97. online

- Fritze, Ronald H., ed. Historical Dictionary of Tudor England, 1485–1603 (Greenwood, 1991) 595pp.

- Goodman, Ruth (2014). How to Be a Victorian: A Dawn-to-Dusk Guide to Victorian Life. Liveright. ISBN 978-0871404855.

- Hartley, Dorothy, and Elliot Margaret M. Life and Work of the People of England. A pictorial record from contemporary sources. The Sixteenth Century. (1926).

- Hutton, Ronald:The Rise and Fall of Merry England: The Ritual Year, 1400–1700, 2001. ISBN 0-19-285447-X

- Mennell, Stephen. All manners of food: eating and taste in England and France from the Middle Ages to the present (University of Illinois Press, 1996).

- Morrill, John, ed. The Oxford illustrated history of Tudor & Stuart Britain (1996) online; survey essays by leading scholars; heavily illustrated

- Pound, John F. Poverty and vagrancy in Tudor England (Routledge, 2014).

- Shakespeare's England. An Account of the Life and Manners of his Age (2 vol. 1916); essays by experts on social history and customs vol 1 online

- Singman, Jeffrey L. Daily Life in Elizabethan England (1995)

- Strong, Roy: The Cult of Elizabeth (The Harvill Press, 1999). ISBN 0-7126-6493-9

- Wagner, John A. Historical Dictionary of the Elizabethan World: Britain, Ireland, Europe, and America (1999)

- Wilson, Jean. Entertainments for Elizabeth I (Studies in Elizabethan and Renaissance Culture) (2007)

- World History Encyclopedia – Food & Drink in the Elizabethan Era

- Wright Louis B. Middle-Class Culture in Elizabethan England (1935)

- Wrightson, Keith. English Society 1580–1680 (Routledge, 2013).

- Yates, Frances A. The Occult Philosophy in the Elizabethan Age. London, Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1979.

- Yates, Frances A. Theatre of the World. Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1969.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elizabethan_era

| Elizabeth | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Portrait by Vigilius Eriksen, 1757 | |||||

| Empress of Russia | |||||

| Reign | 6 December (25 November) 1741 – 5 January (25 December) 1762 | ||||

| Coronation | 6 May (25 April) 1742 | ||||

| Predecessor | Ivan VI | ||||

| Successor | Peter III | ||||

| Born | Elizaveta Petrovna Romanova 29 December 1709 Kolomenskoye, Moscow, Tsardom of Russia | ||||

| Died | 5 January 1762 (aged 52) Winter Palace, Saint Petersburg, Russian Empire | ||||

| Burial | 3 February 1762 (O.S.) | ||||

| |||||

| House | Romanov | ||||

| Father | Peter I of Russia | ||||

| Mother | Catherine I of Russia | ||||

| Religion | Russian Orthodoxy | ||||

| Signature |  | ||||

Elizabeth or Elizaveta Petrovna (Russian: Елизаве́та Петро́вна; 29 December [O.S. 18 December] 1709 – 5 January [O.S. 25 December] 1762) reigned as Empress of Russia from 1741 until her death in 1762. She remains one of the most popular Russian monarchs because of her decision not to execute a single person during her reign, her numerous construction projects, and her strong opposition to Prussian policies.[1]

The second-eldest daughter of Tsar Peter the Great (r. 1682–1725), Elizabeth lived through the confused successions of her father's descendants following her half-brother Alexei's death in 1718. The throne first passed to her mother Catherine I of Russia (r. 1725–1727), then to her nephew Peter II, who died in 1730 and was succeeded by Elizabeth's first cousin Anna (r. 1730–1740). After the brief rule of Anna's infant great-nephew, Ivan VI, Elizabeth seized the throne with the military's support and declared her own nephew, the future Peter III, her heir.

During her reign Elizabeth continued the policies of her father and brought about a remarkable Age of Enlightenment in Russia. Her domestic policies allowed the nobles to gain dominance in local government while shortening their terms of service to the state. She encouraged Mikhail Lomonosov's foundation of the University of Moscow, the highest-ranking Russian educational institution. Her court became one of the most splendid in all Europe, especially regarding architecture: she modernised Russia's roads, encouraged Ivan Shuvalov's foundation of the Imperial Academy of Arts, and financed grandiose Baroque projects of her favourite architect, Bartolomeo Rastrelli, particularly in Peterhof Palace. The Winter Palace and the Smolny Cathedral in Saint Petersburg are among the chief monuments of her reign.[1]

Elizabeth led the Russian Empire during the two major European conflicts of her time: the War of Austrian Succession (1740–1748) and the Seven Years' War (1756–1763). She and diplomat Aleksey Bestuzhev-Ryumin solved the first event by forming an alliance with Austria and France, but indirectly caused the second. Russian troops enjoyed several victories against Prussia and briefly occupied Berlin, but when Frederick the Great was finally considering surrender in January 1762, the Russian Empress died. She was the last agnatic member of the House of Romanov to reign over the Russian Empire.

Early life

Childhood and teenage years

Elizabeth was born at Kolomenskoye, near Moscow, Russia, on 18 December 1709 (O.S.). Her parents were Peter the Great, Tsar of Russia and Catherine.[2] Catherine was the daughter of Samuel Skowroński, a subject of Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Although no documentary record exists, her parents were said to have married secretly at the Cathedral of the Holy Trinity in Saint Petersburg at some point between 23 October and 1 December 1707.[3] Their official marriage was at Saint Isaac's Cathedral in Saint Petersburg on 9 February 1712. On this day, the two children previously born to the couple (Anna and Elizabeth) were legitimised by their father[3] and given the title of Tsarevna ("princess") on 6 March 1711.[2] Of the twelve children born to Peter and Catherine (five sons and seven daughters), only the sisters survived to adulthood.[4] They had one older surviving sibling, crown prince Alexei Petrovich, who was Peter's son by his first wife, noblewoman Eudoxia Lopukhina.[citation needed]

As a child, Elizabeth was the favourite of her father, whom she resembled both physically and temperamentally.[5] Even though he adored his daughter, Peter did not devote time or attention to her education; having both a son and grandson from his first marriage to a noblewoman, he did not anticipate that a daughter born to his former maid might one day inherit the Russian throne, which had until that point never been occupied by a woman; as such, it was left to Catherine to raise the girls, a task met with considerable difficulty due to her own lack of education. Despite this, Elizabeth was still considered to be a bright girl, if not brilliant,[6] and had a French governess who gave lessons of mathematics, arts, languages, and sports. She grew interested in architecture, became fluent in Italian, German, and French, and became an excellent dancer and rider.[2] Like her father, she was physically active and loved horseriding, hunting, sledging, skating, and gardening.[7]

From her earliest years, Elizabeth was recognised as a vivacious young woman, and was regarded as the leading beauty of the Russian Empire.[2] The wife of the British ambassador described Grand Duchess Elizabeth as "fair, with light brown hair, large sprightly blue eyes, fine teeth and a pretty mouth. She is inclinable to be fat, but is very genteel and dances better than anyone I ever saw. She speaks German, French and Italian, is extremely gay, and talks to everyone..."[8]

Marriage plans

With much of his fame resting on his effective efforts to modernise Russia, Tsar Peter desired to see his children married into the royal houses of Europe, something which his immediate predecessors had consciously tended to avoid. Peter's son Aleksei Petrovich, born of his first marriage to a Russian noblewoman, had no problem securing a bride from the ancient house of Brunswick-Lüneburg. However, the Tsar experienced difficulties in arranging similar marriages for the daughters born of his second wife. When Peter offered either of his daughters in marriage to the future Louis XV, the Bourbons of France snubbed him due to the girls' post-facto legitimisation.[4]

In 1724, Peter betrothed his daughters to two young princes, first cousins to each other, who hailed from the tiny north German principality of Holstein-Gottorp and whose family was undergoing a period of political and economic turmoil. Anna Petrovna (aged 16) was to marry Charles Frederick, Duke of Holstein-Gottorp, who was then living in exile in Russia as Peter's guest after having failed in his attempt to succeed his maternal uncle as King of Sweden and whose patrimony was at that time under Danish occupation.[4] Despite all this, the prince was of impeccable birth and well-connected to many royal houses; it was a respectable and politically useful alliance.[9] In the same year, Elizabeth was betrothed to marry Charles Frederick's first cousin, Charles Augustus of Holstein-Gottorp,[9] the eldest son of Christian Augustus, Prince of Eutin. Anna Petrovna's wedding took place in 1725 as planned, even though her father had died (8 February [O.S. 28 January] 1725) a few weeks before the nuptials. In Elizabeth's case, however, her fiancé died on 31 May 1727, before her wedding could be celebrated. This came as a double blow to Elizabeth, because her mother (who had ascended to the throne as Catherine I) had died just two weeks previously, on 17 May 1727.[citation needed]

By the end of May 1727, 17-year-old Elizabeth had lost her fiancé and both of her parents. Furthermore, her half-nephew Peter II had ascended the throne. Her marriage prospects continued to fail to improve three years later, when her nephew died and was succeeded on the throne by Elizabeth's first cousin Anna, daughter of Ivan V. There was little love lost between the cousins and no prospect of either any Russian nobleman or any foreign prince seeking Elizabeth's hand in marriage. Nor could she marry a commoner because it would cost her royal status, property rights and claim to the throne.[10] The fact that Elizabeth was something of a beauty did not improve marriage prospects, but instead earned her resentment. When the Empress Anna asked the Chinese minister in Saint Petersburg to identify the most beautiful woman at her court, he pointed to Elizabeth, much to Anna's displeasure.[11]

Elizabeth's response to the lack of marriage prospects was to take Alexander Shubin, a handsome sergeant in the Semyonovsky Life Guards Regiment, as her lover. When Empress Anna found out about this, she banished him to Siberia. After consoling herself, Elizabeth turned to handsome coachmen and footmen for her sexual pleasure.[10] She eventually found a long-term companion in Alexei Razumovsky, a kind-hearted and handsome Ukrainian peasant serf with a good bass voice. Razumovsky had been brought from his village to Saint Petersburg by a nobleman to sing for a church choir, but the Grand Duchess purchased the talented serf from the nobleman for her own choir. A simple-minded man, Razumovsky never showed interest in affairs of state during all the years of his relationship with Elizabeth, which spanned from the days of her obscurity to the height of her power. As the couple was devoted to each other, there is reason to believe[citation needed] that they might even have married in a secret ceremony. In 1742, the Holy Roman Emperor made Razumovsky a count of the Holy Roman Empire. In 1756, Elizabeth made him a prince and field marshal.[10]

Imperial coup

While Aleksandr Danilovich Menshikov remained in power (until September 1727), the government of Elizabeth's adolescent nephew Peter II (reigned 1727–1730) treated her with liberality and distinction. However, the Dolgorukovs, an ancient boyar family, deeply resented Menshikov. With Peter II's attachment to Prince Ivan Dolgorukov and two of their family members on the Supreme State Council, they had the leverage for a successful coup. Menshikov was arrested, stripped of all his honours and properties, and exiled to northern Siberia, where he died in November 1729.[12] The Dolgorukovs hated the memory of Peter the Great and practically banished his daughter from Court.[13]

During the reign of her cousin Anna (1730–1740), Elizabeth was gathering support in the background. Being the daughter of Peter the Great, she enjoyed much support from the Russian Guards regiments. She often visited the elite Guards regiments, marking special events with the officers and acting as godmother to their children. After the death of Empress Anna, the regency of Anna Leopoldovna for the infant Ivan VI was marked by high taxes and economic problems. [1] The French ambassador in Saint Petersburg, the Marquis de La Chétardie was deeply involved in planning a coup to depose the regent, whose foreign policy was opposed to the interests of France, and bribed numerous officers in the Imperial Guard to support Elizabeth's coup.[14] The French adventurer Jean Armand de Lestocq helped her actions according to the advice of the marquis de La Chétardie and the Swedish ambassador, who were particularly interested in toppling the regime of Anna Leopoldovna.[1]

On the night of 25 November 1741 (O.S.), Elizabeth seized power with the help of the Preobrazhensky Life Guards Regiment. Arriving at the regimental headquarters wearing a warrior's metal breastplate over her dress and grasping a silver cross, she challenged them: "Whom do you want to serve: me, your natural sovereign, or those who have stolen my inheritance?" Won over, the regiment marched to the Winter Palace and arrested the infant Emperor, his parents, and their own lieutenant-colonel, Count Burkhard Christoph von Munnich. It was a daring coup and, amazingly, succeeded without bloodshed. Elizabeth had vowed that if she became Empress, she would not sign a single death sentence, an extraordinary promise at the time but one that she kept throughout her life.[1]

Despite Elizabeth's promise, there was still cruelty in her regime. Although she initially thought of allowing the young tsar and his mother to leave Russia, she imprisoned them later in a Shlisselburg Fortress, worried that they would stir up trouble for her in other parts of Europe.[15] Fearing a coup on Ivan's favour, Elizabeth set about destroying all papers, coins or anything else depicting or mentioning Ivan. She had issued an order that if any attempt were made for the adult Ivan to escape, he was to be eliminated. Catherine the Great upheld the order, and when an attempt was made, he was killed and secretly buried within the fortress.[16]

Another case was Countess Natalia Lopukhina. The circumstances of Elizabeth's birth would later be used by her political opponents to challenge her right to the throne on grounds of illegitimacy. When Countess Lopukhina's son, Ivan Lopukhin, complained of Elizabeth in a tavern, he implicated his mother, himself and others in a plot to reinstate Ivan VI as tsar. Ivan Lopukhin was overheard and tortured for information. All male conspirators were sentenced to death while the female conspirators had their tongues removed and were publicly flogged.[17] [18]

Reign

Elizabeth crowned herself Empress in the Dormition Cathedral on 25 April 1742 (O.S.), which would become standard for all emperors of Russia until 1896. At the age of thirty-three, with relatively little political experience, she found herself at the head of a great empire at one of the most critical periods of its existence. Her proclamation explained that the preceding reigns had led Russia to ruin: "The Russian people have been groaning under the enemies of the Christian faith, but she has delivered them from the degrading foreign oppression."

Russia had been under the domination of German advisers, so its Empress exiled the most unpopular of them, including Andrey Osterman and Burkhard Christoph von Münnich.[19] She passed down several pieces of legislation that undid much of the work her father had done to limit the power of the church.[20]

With all her shortcomings (documents often waited months for her signature),[21] Elizabeth had inherited her father's genius for government. Her usually keen judgement and her diplomatic tact again and again recalled Peter the Great. What sometimes appeared as irresolution and procrastination was most often a wise suspension of judgement under exceptionally difficult circumstances. From the Russian point of view, her greatness as a stateswoman consisted of her steady appreciation of national interests and her determination to promote them against all obstacles.[citation needed]

Educational reforms

Despite the substantial changes made by Peter the Great, he had not exercised a really formative influence on the intellectual attitudes of the ruling classes as a whole. Although Elizabeth lacked the early education necessary to flourish as an intellectual (once finding the reading of secular literature to be "injurious to health"),[22] she was clever enough to know its benefits and made considerable groundwork for her eventual successor, Catherine the Great.[23] She made education freely available to all social classes (except for serfs), encouraged establishment of the very first university in Russia founded in Moscow by Mikhail Lomonosov, and helped to finance the establishment of the Imperial Academy of Fine Arts.[24]

Internal peace

A gifted diplomat, Elizabeth hated bloodshed and conflict and went to great lengths to alter the Russian system of punishment, even outlawing capital punishment.[25] According to historian Robert Nisbet Bain, it was one of her "chief glories that, so far as she was able, she put a stop to that mischievous contention of rival ambitions at Court, which had disgraced the reigns of Peter II, Anna, and Ivan VI, and enabled foreign powers to freely interfere in the domestic affairs of Russia."[26]

Construction projects

Elizabeth enjoyed and excelled in architecture, overseeing and financing many construction projects during her reign. One of the many projects from the Italian architect Bartolomeo Rastrelli was the reconstruction of Peterhof Palace, adding several wings between 1745 and 1755. Her most famous creations were the Winter Palace, though she died before its completion, and the Smolny Convent. The Palace is said to contain 1,500 rooms, 1,786 doors, and 1,945 windows, including bureaucratic offices and the Imperial Family's living quarters arranged in two enfilades, from the top of the Jordan Staircase. Regarding the latter building, historian Robert Nisbet Bain stated that "No other Russian sovereign ever erected so many churches."[27]

The expedited completion of buildings became a matter of importance to the Empress and work continued throughout the year, even in winter's severest months. 859,555 rubles had been allocated to the project, a sum raised by a tax on state-owned taverns, but work temporarily ceased due to lack of resources. Ultimately, taxes were increased on salt and alcohol to completely fund the extra costs. However, Elizabeth's incredible extravagance ended up greatly benefiting the country's infrastructure. Needing goods shipped from all over the world, numerous roads in all Russia were modernised at her orders.[28]

Selection of an heir

As an unmarried and childless empress, it was imperative for Elizabeth to find a legitimate heir to secure the Romanov dynasty. She chose her nephew, Peter of Holstein-Gottorp. [16] The young Peter had lost his mother shortly after he was born, and his father at the age of eleven. Elizabeth invited her young nephew to Saint Petersburg, where he was received into the Russian Orthodox Church and proclaimed the heir to the throne on 7 November 1742.[29] Keen to see the dynasty secured, Elizabeth immediately gave Peter the best Russian tutors and settled on Princess Sophie of Anhalt-Zerbst as a bride for her heir. Incidentally, Sophie's mother, Joanna Elisabeth of Holstein-Gottorp, was a sister of Elizabeth's own fiancé, who had died before the wedding. On her conversion to the Russian Orthodox Church, Sophie was given the name Catherine in memory of Elizabeth's mother. The marriage took place on 21 August 1745. Nine years later a son, the future Paul I, was born on 20 September 1754.[30]

There is considerable speculation as to the actual paternity of Paul. It is suggested that he was not Peter's son at all but that his mother had engaged in an affair, to which Elizabeth had consented, with a young officer, Sergei Vasilievich Saltykov, who would have been Paul's biological father.[31] Peter never gave any indication that he believed Paul to have been fathered by anyone but himself but took no interest in parenthood. Elizabeth most certainly took an active interest and acted as if she were his mother, instead of Catherine.[32] Shortly after Paul’s birth the Empress ordered the midwife to take the baby and to follow her, and Catherine did not see her child for another month, for a short churching ceremony. Six months later, Elizabeth let Catherine see the child again. The child had, in effect, become a ward of the state and, in a larger sense, the property of the state.[33]

Foreign policy

Elizabeth abolished the cabinet council system that had been used under Anna, and reconstituted the Senate as it had been under Peter the Great, with the chiefs of the departments of state (none of them German) attending. Her first task after this was to address the war with Sweden. On 23 January 1743, direct negotiations between the two powers were opened at Åbo. In the Treaty of Åbo, on 7 August 1743 (O.S.), Sweden ceded to Russia all of southern Finland east of the Kymmene River, which became the boundary between the two states. The treaty also gave Russia the fortresses of Villmanstrand and Fredrikshamn.[34]

Bestuzhev

The concessions to Russia can be credited to the diplomatic ability of the new vice chancellor, Aleksey Bestuzhev-Ryumin, who had Elizabeth's support.[35] She placed Bestuzhev at the head of foreign affairs immediately after her accession. He represented the anti-Franco-Prussian side of her council, and his objective was an alliance with England and Austria. At that time, it was probably advantageous to Russia. Both the Lopukhina affair and other attempts of Frederick the Great and Louis XV to get rid of Bestuzhev failed. Instead, they put the Russian court into the centre of a tangle of intrigue during the earlier years of Elizabeth's reign.[34] Ultimately, the minister's strong support from the Empress prevailed.[35]

Bestuzhev had many achievements. His effective diplomacy and 30,000 troops sent to the Rhine accelerated the peace negotiations, leading to the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle (18 October 1748). He extricated his country from the Swedish imbroglio and reconciled his imperial mistress with the courts of Vienna and London. He enabled Russia to assert herself effectually in Poland, the Ottoman Empire, Sweden, and isolated the King of Prussia by forcing him into hostile alliances. All this would have been impossible without the steady support of Elizabeth who trusted him completely in spite of the Chancellor's many enemies, most of whom were her personal friends.[34]

However, on 14 February 1758, Bestuzhev was removed from office. The future Catherine II recorded, "He was relieved of all his decorations and rank, without a soul being able to reveal for what crimes or transgressions the first gentleman of the Empire was so despoiled, and sent back to his house as a prisoner." No specific crime was ever pinned on Bestuzhev. Instead, it was inferred that he had attempted to sow discord between the Empress and her heir and his consort. Enemies of the pro-Austrian Bestuzhev were his rivals; the Shuvalov family, Vice-Chancellor Mikhail Vorontsov, and the French ambassador.[36][clarification needed]

Seven Years' War

The great event of Elizabeth's later years was the Seven Years' War. Elizabeth regarded the Convention of Westminster (16 January 1756) in which Great Britain and Prussia agreed to unite their forces to oppose the entry of or the passage through Germany of troops of every foreign power, as utterly subversive of the previous conventions between Great Britain and Russia. Elizabeth sided against Prussia over a personal dislike of Frederick the Great.[21] She wanted him reduced within proper limits so that he might no longer be an alleged danger to the empire. Elizabeth acceded to the Second Treaty of Versailles, thus entering into an alliance with France and Austria against Prussia. On 17 May 1757, the Imperial Russian Army, 85,000 strong, advanced against Königsberg.[37]

The serious illness of the Empress, which began with a fainting-fit at Tsarskoe Selo (19 September 1757), the fall of Bestuzhev (21 February 1758) and the cabals and intrigues of the various foreign powers at Saint Petersburg, did not interfere with the progress of the war. The crushing defeat of Kunersdorf (12 August 1759)[38] at last brought Frederick to the verge of ruin. From that day, he despaired of success, but he was saved for the moment by the jealousies of the Russian and Austrian commanders, which ruined the military plans of the allies.[34]

From the end of 1759 to the end of 1761, the eagerness of the Russian Empress was the one constraining political force that held together the heterogeneous, incessantly jarring elements of the anti-Prussian combination. From the Russian point of view, her greatness as a stateswoman consisted of her steady appreciation of Russian interests and her determination to promote them against all obstacles. She insisted throughout that the King of Prussia must be reduced to the rank of a Prince-Elector.[34]