| Brick | |

|---|---|

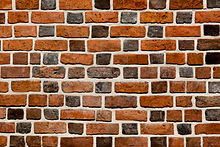

A single brick. |

A brick is a type of construction material used to build walls, pavements and other elements in masonry construction. Properly, the term brick denotes a unit primarily composed of clay, but is now also used informally to denote units made of other materials or other chemically cured construction blocks. Bricks can be joined using mortar, adhesives or by interlocking.[1][2] Bricks are usually produced at brickworks in numerous classes, types, materials, and sizes which vary with region, and are produced in bulk quantities.[3]

Block is a similar term referring to a rectangular building unit composed of clay or concrete, but is usually larger than a brick. Lightweight bricks (also called lightweight blocks) are made from expanded clay aggregate.

Fired bricks are one of the longest-lasting and strongest building materials, sometimes referred to as artificial stone, and have been used since circa 4000 BC. Air-dried bricks, also known as mud-bricks, have a history older than fired bricks, and have an additional ingredient of a mechanical binder such as straw.

Bricks are laid in courses and numerous patterns known as bonds, collectively known as brickwork, and may be laid in various kinds of mortar to hold the bricks together to make a durable structure.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brick

An old brick wall in English bond laid with alternating courses of headers and stretchers.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brick

The brickwork of Shebeli Tower in Iran displays 12th-century craftsmanship

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brick

The Roman Basilica Aula Palatina in Trier, Germany, built with fired bricks in the fourth century as an audience hall for Constantine I

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brick

Malbork Castle of the Teutonic Order in Poland – the largest brick castle in the world

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brick

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kaliningrad

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/East_Prussia

In the National Museum of Roman Art in Mérida, Spain (designed by Rafael Moneo and built in the 1980s) the coating of hard-fired clay bricks forms a compression-resistant element together with the fill of non-reinforced concrete.[23]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brick

At the end of the 19th century, the Hudson River region of New York State would become the world's largest brick manufacturing region, with 130 brickyards lining the shores of the Hudson River from Mechanicsville to Haverstraw and employing 8,000 people. At its peak, about 1 billion bricks were produced a year, with many being sent to New York City for use in its construction industry.[29]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brick

The demand for high office building construction at the turn of the 20th century led to a much greater use of cast and wrought iron, and later, steel and concrete. The use of brick for skyscraper construction severely limited the size of the building – the Monadnock Building, built in 1896 in Chicago, required exceptionally thick walls to maintain the structural integrity of its 17 storeys.[30]

Following pioneering work in the 1950s at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology and the Building Research Establishment in Watford, UK, the use of improved masonry for the construction of tall structures up to 18 storeys high was made viable. However, the use of brick has largely remained restricted to small to medium-sized buildings, as steel and concrete remain superior materials for high-rise construction.[31]

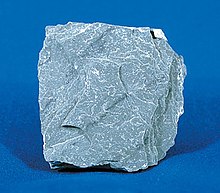

Bricks are often made of shale because it easily splits into thin layers.[citation needed]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brick

Brick making at the beginning of the 20th century

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brick

Yellow London Stocks at Waterloo station

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brick

Swedish Mexitegel is a sand-lime or lime-cement brick.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brick

This wall in Beacon Hill, Boston, shows different types of brickwork a

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brick

Comparison of typical brick sizes of assorted countries with isometric projections and dimensions in millimetres

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brick

Faces of a brick

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brick

In England, the length and width of the common brick remained fairly constant from 1625 when the size was regulated by statute at 9 x 4+1⁄2 x 3 inches[42] (but see brick tax), but the depth has varied from about two inches (51 mm) or smaller in earlier times to about 2+1⁄2 inches (64 mm) more recently. In the United Kingdom, the usual size of a modern brick (from 1965)[43] is 215 mm × 102.5 mm × 65 mm (8+1⁄2 in × 4 in × 2+1⁄2 in), which, with a nominal 10 millimetres (3⁄8 in) mortar joint, forms a unit size of 225 by 112.5 by 75 millimetres (9 in × 4+1⁄2 in × 3 in), for a ratio of 6:3:2.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brick

| Taxation in the United Kingdom |

|---|

|

| UK Government Departments |

| UK Government |

|

| Scottish Government |

| Welsh Government |

| Local Government |

The brick tax was a property tax introduced in Great Britain in 1784, during the reign of King George III, to help pay for the wars in the American Colonies. Bricks were initially taxed at 2s 6d per thousand.[1] The brick tax was eventually abolished in 1850.[2]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brick_tax

Clinker bricks are partially-vitrified bricks used in the construction of buildings.

Clinker bricks are produced when wet clay bricks are exposed to excessive heat during the firing process, sintering the surface of the brick and forming a shiny, dark-colored coating.[1] [2][3] Clinker bricks have a blackened appearance, and they are often misshapen or split.[2] Clinkers are so named for the metallic sound they make when struck together.[4]

Clinker bricks are denser, heavier, and more irregular than standard bricks.[3] Clinkers are water-resistant and durable, but have higher thermal conductivity than more porous red bricks, lending less insulation to climate-controlled structures.[3]

The brick-firing kilns of the early 20th century—called brick clamps or "beehive" kilns—did not heat evenly, and the bricks that were too close to the fire emerged harder, darker, and with more vibrant colors, according to the minerals present in the clay.[5] Initially, these clinkers were discarded as defective, but around 1900, the bricks were salvaged by architects who found them to be usable, distinctive, and charming. Clinker bricks were widely admired by adherents of the Arts and Crafts movement.[5][1]

In the United States, clinker bricks were popularized by the Pasadena, California architecture firm Greene and Greene, who used them for walls, foundations, and chimneys.[6] On the East Coast, clinkers were used extensively in the Colonial Revival style of architecture.[1]

Modern brick-making techniques do not produce clinker bricks, and they have become rare.[1] Builders can procure clinkers from salvage companies; alternatively, some brickmakers purposefully manufacture clinker bricks or produce imitations.[1]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Clinker_brick

Acid brick or acid resistant brick is a specially made form of masonry brick that is chemically resistant and thermally durable.[1] Acid brick is created from high silica shale and fired at higher temperatures than those used for conventional brick. Some manufacturers create the brick by baking it for over a week. It has an average compressive strength of approximately 23,000 PSI.

The ASTM specification C-279 creates specifications for acid brick properties. Acid brick is not resistant against hydrofluoric acid or strong alkali.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Acid_brick

London stock brick is the type of handmade brick which was used for the majority of building work in London and South East England until the growth in the use of Flettons and other machine-made bricks in the early 20th century. Its distinctive yellow colour is due to the addition of chalk. Another important admixture is 'spanish', which consists of ashes and cinders from rubbish. The spanish ignites on firing and reduces fuel costs at the firing stage. London Stocks are still made in comparatively small quantities in traditional brickworks, mainly in Kent and Sussex, for heritage work, and machine-made versions are available for use where a cheaper approximation to the traditional product is acceptable.[1] Red stock bricks are also fairly common, but only the yellow or brown bricks are usually known as London stocks.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/London_stock_brick

Roman brick is a type of brick used in Ancient Roman architecture and spread by the Romans to the lands they conquered, or a modern adaptation derived from the ancient prototypes. In both cases, it characteristically has longer and flatter dimensions than those of standard modern bricks.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roman_brick

Staffordshire blue brick is a strong type of construction brick, originally made in Staffordshire, England.

The brick is made from the local red clay, Etruria marl, which when fired at a high temperature in a low-oxygen reducing atmosphere takes on a deep blue colour and attains a very hard surface with high crushing strength and low water absorption.

Brickworks were a key industry across the whole Black Country throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, and were considered so important that they were designated as a reserved occupation during World War Two. The Black Country was a major producer of clay for brickmaking, often mined from beneath the 30 foot Staffordshire coal seam. The industry dates back to at least the 17th century, however brickworks really took off in the 19th century.[1] A key date is 1851 when the Joseph Hamblet brickworks were founded in West Bromwich, which became one of the largest producers of Staffordshire blue bricks. Other sites produced these as well, including Albion in West Bromwich, Cakemore works at Blackheath, Springfield at Rowley Regis, John Sadler, Blades and New Century at Oldbury, Coneygre at Tipton, and Bentley Hall near Darlaston.[2]

This type of brick was used for foundations as well as being extensively used for bridges and tunnels in canal construction, and later, for railways. Its lack of porosity makes it suitable for capping brick walls, and its hard-wearing properties make it ideal for steps and pathways. It is also used as a general facing brick for decorative reasons. Staffordshire Blue bricks have traditionally been "Class A" with a water absorption of less than 4.5%.[citation needed]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Staffordshire_blue_brick

Cream City brick is a cream or light yellow-colored brick made from a clay found around Milwaukee, Wisconsin, in the Menomonee River Valley and on the western banks of Lake Michigan. These bricks were one of the most common building materials used in Milwaukee during the mid and late 19th century, giving the city the nickname "Cream City" and the bricks the name "Cream City bricks".[1]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cream_City_brick

| Sedimentary rock | |

Shale | |

| Composition | |

|---|---|

| Clay minerals and quartz |

Shale is a fine-grained, clastic sedimentary rock formed from mud that is a mix of flakes of clay minerals (hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates, e.g. kaolin, Al2Si2O5(OH)4) and tiny fragments (silt-sized particles) of other minerals, especially quartz and calcite.[1] Shale is characterized by its tendency to split into thin layers (laminae) less than one centimeter in thickness. This property is called fissility.[1] Shale is the most common sedimentary rock.[2]

The term shale is sometimes applied more broadly, as essentially a synonym for mudrock, rather than in the more narrow sense of clay-rich fissile mudrock.[3]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shale

| Metamorphic rock | |

Slate | |

| Composition | |

|---|---|

| Primary | quartz, muscovite/illite |

| Secondary | biotite, chlorite, hematite, pyrite Specific gravity: 2.7 – 2.8,2.9 |

Slate is a fine-grained, foliated, homogeneous, metamorphic rock derived from an original shale-type sedimentary rock composed of clay or volcanic ash through low-grade, regional metamorphism. It is the finest-grained foliated metamorphic rock.[1] Foliation may not correspond to the original sedimentary layering, but instead is in planes perpendicular to the direction of metamorphic compression.[1]

The foliation in slate, called "slaty cleavage",[1] is caused by strong compression in which fine-grained clay forms flakes to regrow in planes perpendicular to the compression.[1] When expertly "cut" by striking parallel to the foliation, with a specialized tool in the quarry, many slates display a property called fissility, forming smooth, flat sheets of stone, which have long been used for roofing, floor tiles, and other purposes.[1] Slate is frequently grey in color, especially when seen en masse covering roofs. However, slate occurs in a variety of colors even from a single locality; for example, slate from North Wales can be found in many shades of grey, from pale to dark, and may also be purple, green, or cyan. Slate is not to be confused with shale, from which it may be formed, or schist.

The word "slate" is also used for certain types of object made from slate rock. It may mean a single roofing tile made of slate, or a writing slate, which was traditionally a small, smooth piece of the rock, often framed in wood, used with chalk as a notepad or notice board, and especially for recording charges in pubs and inns. The phrases "clean slate" and "blank slate" come from this usage.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Slate

https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?search=slate+tax&title=Special%3ASearch&ns0=1

A carbon tax is a tax levied on the carbon emissions required to produce goods and services. Carbon taxes are intended to make visible the "hidden" social costs of carbon emissions, which are otherwise felt only in indirect ways like more severe weather events. In this way, they are designed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by increasing prices of the fossil fuels

that emit them when burned. This both decreases demand for goods and

services that produce high emissions and incentivizes making them less carbon-intensive.[1] In its simplest form, a carbon tax covers only CO2 emissions; however, it could also cover other greenhouse gases, such as methane or nitrous oxide, by taxing such emissions based on their CO2-equivalent global warming potential.[2] When a hydrocarbon fuel such as coal, petroleum, or natural gas is burned, most or all of its carbon is converted to CO

2. Greenhouse gas emissions cause climate change, which damages the environment and human health. This negative externality can be reduced by taxing carbon content at any point in the product cycle.[3][4][5][6] Carbon taxes are thus a type of Pigovian tax.[7]

Research shows that carbon taxes effectively reduce emissions.[8] Many economists argue that carbon taxes are the most efficient (lowest cost) way to tackle climate change.[9][10][11][12][13] Seventy-seven countries and over 100 cities have committed to achieving net zero emissions by 2050.[14][8] As of 2019, carbon taxes have been implemented or scheduled for implementation in 25 countries,[15] while 46 countries put some form of price on carbon, either through carbon taxes or emissions trading schemes.[16]

On their own, carbon taxes are usually regressive, since lower-income households tend to spend a greater proportion of their income on emissions-heavy goods and services like transportation than higher-income households. To make them more progressive, policymakers can try to redistribute the revenue generated from carbon taxes to low-income groups by lowering income taxes or offering rebates,[17] then as part of the politics of climate change the overall policy initiative can be referred to as a carbon fee and dividend, rather than a tax.[18]

A carbon tax as well as carbon emission trading is used within the carbon price concept. Two common economic alternatives to carbon taxes are tradable permits/credits and subsidies.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carbon_tax

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/calorie

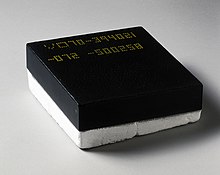

Pixel Slate with keyboard | |

| Developer | |

|---|---|

| Manufacturer | Quanta Computer[1] (under contract) |

| Product family | Google Pixel |

| Type | 2-in-1 detachable |

| Release date | October 9, 2018 |

| Introductory price | Celeron model: $599 USD (4 GB RAM) $699 USD (8 GB RAM) Core m3 Model: $799 USD Core i5 model: $999 USD Core i7 model: $1599 USD |

| Discontinued | January 20, 2021 |

| Operating system | Chrome OS |

| CPU | Intel Kaby Lake Celeron 3965Y, m3-8100Y, i5-8200Y, or i7-8500Y[2] |

| Memory | Celeron: 4 or 8 GB m3: 8 GB i5: 8 GB i7: 16 GB[2] |

| Storage | Celeron: 32 GB eMMC SSD 64 GB eMMC SSD m3: 64 GB eMMC SSD i5: 128 GB eMMC SSD i7: 256 GB eMMC SSD |

| Removable storage | USB external storage over USB-C[3] |

| Display | 312 mm (12.3 in) Molecular Display 3000x2000 (293 ppi, 115 px/cm) LTPS LCD with Gorilla Glass 5[2] |

| Graphics | Intel UHD Graphics 615 |

| Sound | Stereo dual-coil front-firing speakers, USB-C audio, included USB-C to 3.5mm headphone jack adapter, dual microphones[2] |

| Input | Multi-touch screen, Pixel Imprint fingerprint sensor,[2] 3-axis gyroscope/accelerometer, ambient light sensor, hall effect sensor[4] |

| Camera | Front: 8 MP, ƒ/1.9 aperture wide FoV, 1080p 30fps video, 1.4μm pixel size Rear: 8 MP, ƒ/1.8 aperture, 1080p 30fps video, 1.12μm pixel size[2] |

| Connectivity | Wi-Fi 802.11 a/b/g/n/ac, 2x2 MIMO, dual-band Bluetooth 4.2[2] Two USB-C ports Pogo pin accessory connector |

| Power | 48 Wh rechargeable battery, Power Delivery over USB-C |

| Dimensions | 202.04 mm (7.954 in) (h) 290.85 mm (11.451 in) (w) 7.0 mm (0.28 in) (d)[2] |

| Mass | 731 g (1.612 lb)[2] |

| Predecessor | Pixel C |

| Successor | Pixel Tablet |

| Related | Google Pixelbook Pixel 3 |

| Website | store |

The Pixel Slate is a 12.3-inch tablet running ChromeOS. It was developed by Google and released on October 9, 2018, at the Made by Google event. In June 2019, Google announced it will not further develop the product line, and canceled two models that were under development. The Pixel Slate was removed from the Google Store in January 2021.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pixel_Slate

Front Street along the Cane River in historic Natchitoches, Louisiana, is paved with bricks.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brick

In the United States, bricks have been used for both buildings and pavement. Examples of brick use in buildings can be seen in colonial era buildings and other notable structures around the country. Bricks have been used in paving roads and sidewalks especially during the late 19th century and early 20th century. The introduction of asphalt and concrete reduced the use of brick for paving, but they are still sometimes installed as a method of traffic calming or as a decorative surface in pedestrian precincts. For example, in the early 1900s, most of the streets in the city of Grand Rapids, Michigan, were paved with bricks. Today, there are only about 20 blocks of brick-paved streets remaining (totalling less than 0.5 percent of all the streets in the city limits).[47] Much like in Grand Rapids, municipalities across the United States began replacing brick streets with inexpensive asphalt concrete by the mid-20th century.[48]

In Northwest Europe, bricks have been used in construction for centuries. Until recently, almost all houses were built almost entirely from bricks. Although many houses are now built using a mixture of concrete blocks and other materials, many houses are skinned with a layer of bricks on the outside for aesthetic appeal.

Bricks in the metallurgy and glass industries are often used for lining furnaces, in particular refractory bricks such as silica, magnesia, chamotte and neutral (chromomagnesite) refractory bricks. This type of brick must have good thermal shock resistance, refractoriness under load, high melting point, and satisfactory porosity. There is a large refractory brick industry, especially in the United Kingdom, Japan, the United States, Belgium and the Netherlands.

Engineering bricks are used where strength, low water porosity or acid (flue gas) resistance are needed.

In the UK a red brick university is one founded in the late 19th or early 20th century. The term is used to refer to such institutions collectively to distinguish them from the older Oxbridge institutions, and refers to the use of bricks, as opposed to stone, in their buildings.

Colombian architect Rogelio Salmona was noted for his extensive use of red bricks in his buildings and for using natural shapes like spirals, radial geometry and curves in his designs.[49]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brick

A panorama after the 1906 San Francisco earthquake.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brick

Brick sidewalk in Cambridge, Massachusetts, U.S.

Brick made as a byproduct of ironstone mining Normanby – UK

Fired, clay bricks in Hainan, China

The largest brick warehouse in the world, Stanley Dock Tobacco Warehouse, Liverpool, UK

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brick

See also

- Autoclaved aerated concrete – Lightweight, precast building material

- Banna'i – Use of glazed tiles alternating with plain brick for decorative purposes

- Ceramic building material – Archaeological term for baked clay building material

- Glossary of British bricklaying – List of bricklaying terms and their meanings

- Opus africanum – Form of ashlar masonry used in Carthaginian and ancient Roman architecture

- Opus latericium – Ancient Roman brickwork construction

- Opus mixtum – Combination of Roman construction techniques

- Opus spicatum – Herringbone pattern of masonry construction used in Roman and medieval times

- Opus vittatum – Roman construction technique using horizontal courses of tuff blocks alternated with bricks

- Polychrome brickwork – Use of bricks of different colours for decoration

- Stockade Building System – Building block system using compressed wood shavings

- Surfaced block – Concrete masonry unit with a durable, slick surface

- Wienerberger – Manufacturer of bricks, pavers and pipes

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brick

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brick

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chimney

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fireplace

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Party_wall

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fire_lookout_tower

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Firewall_(construction)

A metallurgical furnace, more commonly referred to as a furnace, is a device used to heat and melt metal ore to remove gangue, primarily in iron and steel production. The heat energy to fuel a furnace may be supplied directly by fuel combustion, by electricity such as the electric arc furnace, or through induction heating in induction furnaces. There are several different types of furnaces used in metallurgy to work with specific metal and ores.[1]

Smelting furnaces

Smelting furnaces are used in smelting to extract metal from ore. Smelting furnaces include:

- The blast furnace, used to reduce iron ore to pig iron

- Steelmaking furnaces, including:

Other furnaces

- Furnaces used to remelt metal in foundries.

- Furnaces used to reheat and heat treat metal for use in:

- Rolling mills, including tinplate works and slitting mills.

- Forges

- Open hearth furnace

- Electric arc furnace

References

- D, C. H. (1923-11-24). "Metallurgical Furnaces". Nature. 112 (2821): 755–756. doi:10.1038/112755a0. ISSN 1476-4687. S2CID 28751324.

A fire brick, firebrick, or refractory is a block of ceramic material used in lining furnaces, kilns, fireboxes, and fireplaces. A refractory brick is built primarily to withstand high temperature, but will also usually have a low thermal conductivity for greater energy efficiency. Usually dense firebricks are used in applications with extreme mechanical, chemical, or thermal stresses, such as the inside of a wood-fired kiln or a furnace, which is subject to abrasion from wood, fluxing from ash or slag, and high temperatures. In other, less harsh situations, such as in an electric- or natural gas-fired kiln, more porous bricks, commonly known as "kiln bricks", are a better choice.[1] They are weaker, but they are much lighter and easier to form and insulate far better than dense bricks. In any case, firebricks should not spall, and their strength should hold up well during rapid temperature changes.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fire_brick

High-temperature reusable surface insulation (HRSI)

The black HRSI tiles provided protection against temperatures up to 1,260 °C (2,300 °F). There were 20,548 HRSI tiles which covered the landing gear doors, external tank umbilical connection doors, and the rest of the orbiter's under surfaces. They were also used in areas on the upper forward fuselage, parts of the orbital maneuvering system pods, vertical stabilizer leading edge, elevon trailing edges, and upper body flap surface. They varied in thickness from 1 to 5 inches (2.5 to 12.7 cm), depending upon the heat load encountered during reentry. Except for closeout areas, these tiles were normally 6 by 6 inches (15 by 15 cm) square. The HRSI tile was composed of high purity silica fibers. Ninety percent of the volume of the tile was empty space, giving it a very low density (9 lb/cu ft or 140 kg/m3) making it light enough for spaceflight.[1] The uncoated tiles were bright white in appearance and looked more like a solid ceramic than the foam-like material that they were.

The black coating on the tiles was Reaction Cured Glass (RCG) of which tetraboron silicide and borosilicate glass were some of several ingredients.[9] RCG was applied to all but one side of the tile to protect the porous silica and to increase the heat sink properties. The coating was absent from a small margin of the sides adjacent to the uncoated (bottom) side. To waterproof the tile, dimethylethoxysilane was injected into the tiles by syringe. Densifying the tile with tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS) also helped to protect the silica and added additional waterproofing.

An uncoated HRSI tile held in the hand feels like a very light foam, less dense than styrofoam, and the delicate, friable material must be handled with extreme care to prevent damage. The coating feels like a thin, hard shell and encapsulates the white insulating ceramic to resolve its friability, except on the uncoated side. Even a coated tile feels very light, lighter than a same-sized block of styrofoam. As expected for silica, they are odorless and inert.[citation needed]

HRSI was primarily designed to withstand transition from areas of extremely low temperature (the void of space, about −270 °C or −454 °F) to the high temperatures of re-entry (caused by interaction, mostly compression at the hypersonic shock, between the gases of the upper atmosphere & the hull of the Space Shuttle, typically around 1,600 °C or 2,910 °F).[1]

Fibrous Refractory Composite Insulation Tiles (FRCI)

The black FRCI tiles provided improved durability, resistance to coating cracking and weight reduction. Some HRSI tiles were replaced by this type.[1]

Toughened unipiece fibrous insulation (TUFI)

A stronger, tougher tile which came into use in 1996. TUFI tiles came in high temperature black versions for use in the orbiter's underside, and lower temperature white versions for use on the upper body. While more impact resistant than other tiles, white versions conducted more heat which limited their use to the orbiter's upper body flap and main engine area. Black versions had sufficient heat insulation for the orbiter underside but had greater weight. These factors restricted their use to specific areas.[1]

Low-temperature reusable surface insulation (LRSI)

White in color, these covered the upper wing near the leading edge. They were also used in selected areas of the forward, mid, and aft fuselage, vertical tail, and the OMS/RCS pods. These tiles protected areas where reentry temperatures are below 1,200 °F (649 °C). The LRSI tiles were manufactured in the same manner as the HRSI tiles, except that the tiles were 8 by 8 inches (20 by 20 cm) square and had a white RCG coating made of silica compounds with shiny aluminium oxide.[1] The white color was by design and helped to manage heat on orbit when the orbiter was exposed to direct sunlight.

These tiles were reusable for up to 100 missions with refurbishment (100 missions was also the design lifetime of each orbiter). They were carefully inspected in the Orbiter Processing Facility after each mission, and damaged or worn tiles were immediately replaced before the next mission. Fabric sheets known as gap fillers were also inserted between tiles where necessary. These allowed for a snug fit between tiles, preventing excess plasma from penetrating between them, yet allowing for thermal expansion and flexing of the underlying vehicle skin.

Prior to the introduction of FIB blankets, LRSI tiles occupied all of the areas now covered by the blankets, including the upper fuselage and the whole surface of the OMS pods. This TPS configuration was only used on Columbia and Challenger.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Space_Shuttle_thermal_protection_system#High-temperature_reusable_surface_insulation_(HRSI)

| |

| Author | Don W. Green, Marylee Z. Southard (Editors - 9th edition) |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Subject | Chemical Engineering |

| Publisher | McGraw-Hill |

Publication date | 23 September 2018 (9th Edition) |

| Media type | Hardback |

| Pages | 2272 (9th Edition) |

| ISBN | 0-07-142294-3 |

| OCLC | 72470708 |

| 660 22 | |

| LC Class | TP151 .P45 2008 |

Perry's Chemical Engineers' Handbook (also known as Perry's Handbook, Perry's, or The Chemical Engineer's Bible)[1][2] was first published in 1934 and the most current ninth edition was published in July 2018.[citation needed] It has been a source of chemical engineering knowledge for chemical engineers, and a wide variety of other engineers and scientists, through eight previous editions spanning more than 80 years.[citation needed]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Perry%27s_Chemical_Engineers%27_Handbook

No comments:

Post a Comment