A fairy tale (alternative names include fairytale, fairy story, magic tale, or wonder tale) is a short story that belongs to the folklore genre.[1] Such stories typically feature magic, enchantments, and mythical or fanciful beings. In most cultures, there is no clear line separating myth from folk or fairy tale; all these together form the literature of preliterate societies.[2] Fairy tales may be distinguished from other folk narratives such as legends (which generally involve belief in the veracity of the events described)[3] and explicit moral tales, including beast fables. Prevalent elements include dwarfs, dragons, elves, fairies, giants, gnomes, goblins, griffins, mermaids, talking animals, trolls, unicorns, monsters, witches, wizards, and magic and enchantments.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fairy_tale

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aarne%E2%80%93Thompson%E2%80%93Uther_Index

The Aarne–Thompson–Uther Index (ATU Index) is a catalogue of folktale types used in folklore studies. The ATU Index is the product of a series of revisions and expansions by an international group of scholars: originally composed in German by Finnish folklorist Antti Aarne (1910), the index was translated into English, revised, and expanded by American folklorist Stith Thompson (1928, 1961), and later further revised and expanded by German folklorist Hans-Jörg Uther (2004). The ATU Index, along with Thompson's Motif-Index of Folk-Literature (1932) – with which it is used in tandem, is an essential tool for folklorists.[1]

Definition of tale type

In The Folktale, Thompson defines a tale type as follows:

- A type is a traditional tale that has an independent existence. It may be told as a complete narrative and does not depend for its meaning on any other tale. It may indeed happen to be told with another tale, but the fact that it may be told alone attests its independence. It may consist of only one motif or of many.[2]

Predecessors

Austrian consul Johann Georg von Hahn devised a preliminary analysis of some 44 tale "formulae" as introduction to his book of Greek and Albanian folktales, published in 1864.[3][4]

Reverend Sabine Baring-Gould, in 1866, translated von Hahn's list and expanded to 52 tale types, which he called "Story Radicals".[5][6] Folklorist Joseph Jacobs expanded the list to seventy tale types and published it as Appendix C in Charlotte Sophia Burne and Laurence Gomme's Handbook of Folk-Lore.[7]

Before the edition of Antti Aarne's first folktale classification, Astrid Lunding translated Svend Grundtvig's system of folktale classification. This catalogue consisted of 134 types, mostly based on Danish folktale compilations in comparison to international collections available at the time by other folklorists, such as the Brothers Grimm's and Emmanuel Cosquin's.[8]

History

Antti Aarne was a student of Julius Krohn and his son Kaarle Krohn. Aarne developed the historic-geographic method of comparative folkloristics, and developed the initial version of what became the Aarne–Thompson tale type index for classifying folktales, first published in 1910 as Verzeichnis der Märchentypen ("List of Fairy Tale Types").[9] The system was based on identifying motifs and the repeated narrative ideas that can be seen as the building-blocks of traditional narrative; its scope was European.[10]

The American folklorist Stith Thompson revised Aarne's classification system in 1928, enlarging its scope, while also translating it from German into English.[11] In doing so, he created the "AT number system" (also referred to as "AaTh system") which remained in use through the second half of the century. Another edition with further revisions by Thompson followed in 1961. According to American folklorist D. L. Ashliman, "The Aarne–Thompson system catalogues some 2500 basic plots from which, for countless generations, European and Near Eastern storytellers have built their tales".[12]

The AT-number system was updated and expanded in 2004 with the publication of The Types of International Folktales: A Classification and Bibliography by German folklorist Hans-Jörg Uther. Uther noted that many of the earlier descriptions were cursory and often imprecise, that many "irregular types" are in fact old and widespread, and that "emphasis on oral tradition" often obscured "older, written versions of the tale types". To remedy these shortcomings Uther developed the Aarne–Thompson–Uther classification (ATU) system and included more tales from eastern and southern Europe as well as "smaller narrative forms" in this expanded listing. He also put the emphasis of the collection more explicitly on international folktales, removing examples whose attestation was limited to one ethnic group.[10][13]

System

The Aarne–Thompson Tale Type Index divides tales into sections with an AT number for each entry. The names given are typical, but usage varies; the same tale type number may be referred to by its central motif or by one of the variant folktales of that type, which can also vary, especially when used in different countries and cultures. The name does not have to be strictly literal for every folktale. For example, The Cat as Helper (545B) also includes tales where a fox helps the hero. Closely related folktales are often grouped within a type. For example, tale types 400–424 all feature brides or wives as the primary protagonist, for instance The Quest for a Lost Bride (400) or the Animal Bride (402). Subtypes within a tale type are designated by the addition of a letter to the AT number, for instance: tale 510, Persecuted Heroine (renamed in Uther's revision as Cinderella and Peau d'Âne ["Cinderella and Donkey Skin"]), has subtypes 510A, Cinderella, and 510B, Catskin (renamed in Uther's revision as Peau d'Asne [also "Donkey Skin"]).

As an example, the entry for 510A in the ATU index (with cross-references to motifs in Thompson's Motif-Index of Folk Literature in square brackets, and variants in parentheses) reads:

510A Cinderella. (Cenerentola, Cendrillon, Aschenputtel.) A young woman is mistreated by her stepmother and stepsisters [S31, L55] and has to live in the ashes as a servant. When the sisters and the stepmother go to a ball (church), they give Cinderella an impossible task (e.g. sorting peas from ashes), which she accomplishes with the help of birds [B450]. She obtains beautiful clothing from a supernatural being [D1050.1, N815] or a tree that grows on the grave of her deceased mother [D815.1, D842.1, E323.2] and goes unknown to the ball. A prince falls in love with her [N711.6, N711.4], but she has to leave the ball early [C761.3]. The same thing happens on the next evening, but on the third evening, she loses one of her shoes [R221, F823.2].

The prince will marry only the woman whom the shoe fits [H36.1]. The stepsisters cut pieces off their feet in order to make them fit into the shoe [K1911.3.3.1], but a bird calls attention to this deceit. Cinderella, who had first been hidden from the prince, tries on the shoe and it fits her. The prince marries her.

Combinations: This type is usually combined with episodes of one or more other types, esp. 327A, 403, 480, 510B, and also 408, 409, 431, 450, 511, 511A, 707, and 923.

Remarks: Documented by Basile, Pentamerone (I,6) in the 17th century.

The entry concludes, like others in the catalogue, with a long list of references to secondary literature on the tale, and variants of it.[14]

Critical response

In his essay "The Motif-Index and the Tale Type Index: A Critique", American folklorist Alan Dundes explains that the Aarne–Thompson indexes are some of the "most valuable tools in the professional folklorist's arsenal of aids for analysis".[1]

The tale type index was criticized by Vladimir Propp of the Russian Formalist school of the 1920s for ignoring the functions of the motifs by which they are classified. Furthermore, Propp contended that using a "macro-level" analysis means that the stories that share motifs might not be classified together, while stories with wide divergences may be grouped under one tale type because the index must select some features as salient.[15] He also observed that while the distinction between animal tales and tales of the fantastic was basically correct — no one would classify "Tsarevitch Ivan, the Fire Bird and the Gray Wolf" as an animal tale just because of the wolf — it did raise questions because animal tales often contained fantastic elements, and tales of the fantastic often contained animals; indeed a tale could shift categories if a peasant deceived a bear rather than a devil.[16]

In describing the motivation for his work,[17] Uther presents several criticisms of the original index. He points out that Thompson's focus on oral tradition sometimes neglects older versions of stories, even when written records exist, that the distribution of stories is uneven (with Eastern and Southern European as well as many other regions' folktale types being under-represented), and that some included folktale types have dubious importance. Similarly, Thompson had noted that the tale type index might well be called The Types of the Folk-Tales of Europe, West Asia, and the Lands Settled by these Peoples.[17] However, Alan Dundes notes that in spite of the flaws of tale type indexes (e. g., typos, redundancies, censorship, etc.; p. 198),[1] "they represent the keystones for the comparative method in folkloristics, a method which despite postmodern naysayers ... continues to be the hallmark of international folkloristics" (p. 200).[1]

Author Pete Jordi Wood claims that topics related to homosexuality have been excluded intentionally from the type index.[18] Similarly, folklorist Joseph P. Goodwin states that Thompson omitted "much of the extensive body of sexual and 'obscene' material", and that - as of 1995 - "topics like homosexuality are still largely excluded from the type and motif indexes."[19]

In regards to the geographical criticism, it has been said that the ATU folktype index seems to concentrate on Europe and North Africa,[20] or overrepresent Eurasia[a] and North America.[22] The catalogue appears to ignore or underrepresent, for example, Central Asia, a region from where, some scholars propose, may emerge new folktale types, previously not contemplated by the original catalogue, such as Yuri Berezkin's The Captive Khan and the Clever Daughter-in-Law (and variants)[20] and The travelling girl and her helpful siblings,[23] or Woman's Magical Horse, as named by researcher Veronica Muskheli of the University of Washington.[24]

In regards to the typological classification, some folklorists and tale comparativists have acknowledged singular tale types that, due to their own characteristics, would merit their own type.[b] However, such tales have not been listed in the international folktale system, yet they exist in regional or national classifications.[25]

Use in folkloristics

A quantitative study, published by folklorist Sara Graça da Silva and anthropologist Jamshid J. Tehrani in 2016, tried to evaluate the time of emergence for the "Tales of Magic" (ATU 300–ATU 749), based on a phylogenetic model.[26] They found four of them to belong to the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) stratum of magic tales:[c]

- ATU 328 The Boy Steals Ogre's Treasure (= Jack and the Beanstalk and Thirteen)

- ATU 330 The Smith and the Devil (KHM 81a)

- ATU 402 The Animal Bride (= The Three Feathers, KHM 63 and The Poor Miller's Boy and the Cat, KHM 106)

- ATU 554 The Grateful Animals (= The White Snake, KHM 17 and The Queen Bee, KHM 62)

Ten more magic tales were found to be current throughout the Western branch of the Indo-European languages, comprising the main European language families derived from PIE (i. e. Balto-Slavic, Germanic, Italic and Celtic):

- ATU 311 Rescue by Sister (= Fitcher's Bird, KHM 46)

- ATU 332 Godfather Death (= KHM 44)

- ATU 425C Beauty and the Beast

- ATU 470 Friends in Life and Death[27][28]

- ATU 500 The Name of the Supernatural Helper (= Rumpelstiltskin, KHM 55)

- ATU 505 The Grateful Dead

- ATU 531 The Clever Horse (= Ferdinand the Faithful and Ferdinand the Unfaithful, KHM 126)

- ATU 592 The Dance Among Thorns[29][d]

- ATU 650A Strong John (= Strong Hans, KHM 166)

- ATU 675 The Lazy Boy[31] (= Peruonto and Emelian the Fool)

List

- Bear's Son Tale and Jean de l'Ours, analyses of tale-types 301 and 650A

- Animal as Bridegroom, analysis of ATU 425 and related types

- The Bird Lover, analysis of tale-type 432

- The Spinning-Woman by the Spring, overview of type 480

- Grateful dead (folklore), analysis of types 505-508

- Calumniated Wife, an overview of ATU types 705-712

- The Three Golden Children, analysis of type ATU 707

- Riddle-tales (ancient and medieval), an analysis of types 851, 851A and 927

See also

Notes

- The original version of the "Dance Among the Thorns" tale-type comes from 15th century Europe, and features a monk who was forced to dance in a thorn bush, by a boy with a magic flute or fiddle. It reflected the anticlerical sentiment of many folk tales at the time, and implies that the monk deserves this punishment. Grimms' The Jew Among Thorns (KHM 110) is an example of this type of tale. An American version of this tale, told to folklorist Marie Campbell in 1958 in Kentucky, included this apology from the informant: "Seems like all the tales about Jews gives the Jews a bad name—greedy, grabbing for cash money, cheating their work hands out of their wages—I don't know what all. I never did know a Jew, never even met up with one."[30]

References

- Bottigheimer, Ruth B. (1993). "Luckless, Witless, and Filthy-Footed: A Sociocultural Study and Publishing History Analysis of "The Lazy Boy"". The Journal of American Folklore. 106 (421): 259–284. doi:10.2307/541421. JSTOR 541421.

Bibliography

- Antti Aarne. 1961. The Types of the Folktale: A Classification and Bibliography, The Finnish Academy of Science and Letters, Helsinki. ISBN 951-41-0132-4

- Ashliman, D. L. 1987. A Guide to Folktales in the English Language: Based on the Aarne–Thompson Classification System. New York, Greenwood Press.

- Azzolina, David S. 1987. Tale type- and motif-indexes: An annotated bibliography. New York, London: Garland.

- Dundes, Alan (1997). "The Motif-Index and the Tale Type Index: A Critique". Journal of Folklore Research. 34 (3): 195–202. JSTOR 3814885.

- Karsdorp, Folgert; van der Meulen, Marten; Meder, Theo; van den Bosch, Antal (2 January 2015). "MOMFER: A Search Engine of Thompson's Motif-Index of Folk Literature". Folklore. 126 (1): 37–52. doi:10.1080/0015587X.2015.1006954. S2CID 162278853.

- Thompson, Stith. 1977. The Folktale. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Uther, Hans-Jörg. 2004. The Types of International Folktales: A Classification and Bibliography. Based on the system of Antti Aarne and Stith Thompson. FF Communications no. 284–286. Helsinki: Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia. Three volumes. ISBN 951-41-0955-4 (vol. 1), ISBN 951-41-0961-9 (vol. 2), ISBN 951-41-0963-5 (vol. 3.)

Further reading

- Bortolini, Eugenio; Pagani, Luca; Crema, Enrico R.; Sarno, Stefania; Barbieri, Chiara; Boattini, Alessio; Sazzini, Marco; da Silva, Sara Graça; Martini, Gessica; Metspalu, Mait; Pettener, Davide; Luiselli, Donata; Tehrani, Jamshid J. (22 August 2017). "Inferring patterns of folktale diffusion using genomic data". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 114 (34): 9140–9145. Bibcode:2017PNAS..114.9140B. doi:10.1073/pnas.1614395114. PMC 5576778. PMID 28784786.

- Goldberg, Christine (2010). "Strength in Numbers: The Uses of Comparative Folktale Research". Western Folklore. 69 (1): 19–34. JSTOR 25735282.

- Conrad, JoAnn (March 2006). "Besprechungen (Review of) Asplund Ingemark, Camilla: The Genre of Trolls". Fabula. 47 (1–2): 133–188. doi:10.1515/FABL.2006.016. and subsequent reviews in the same chapter.

- Kawan, Christine Shojaei (2004). "Reflections on International Narrative Research on the Example of The Tale of the Three Oranges". Folklore. 27: 29–48. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.694.4230. doi:10.7592/FEJF2004.27.kawan.

- Uther, Hans-Jörg (30 June 2009). "Classifying tales: Remarks to indexes and systems of ordering". Narodna Umjetnost. 46 (1): 15–32.

- Campos, Camiño Noia (2021). Catalogue of Galician Folktales. Folklore Fellows Communications. Vol. 322. Helsinki: The Kalevala Society. ISBN 978-952-9534-01-2.

External links

- D. L. Ashliman, "Folklore and Mythology Electronic Texts"

- Index – Schnellsuche Märchentyp AT (in German)

- Kinnes, Tormod (2009). "The ATU System". AT Types of Folktales. Retrieved June 14, 2010.

- A search tool for ATU numbers' geographic distribution

- Folktale and Folk Motif Index, a list of folktales according to the ATU Index by the University of Missouri

- Volksverhalenbank by Meertens Institute (in Dutch)

- Names of the tale types according to the Enzyklopädie des Märchens (in German)

International collections:

- Web Platform of Comparative Folk Narrative Research, with record of Georgian folktales classified according to the ATU index

- Aarne-Thompson index to the Irish Folklore Commission online collection

- Online Repository of the Uysal-Walker Archive of Turkish Oral Narrative at Texas Tech University

- Folktales from the Setomaa region from the collection of Hendrik Prants (et) (In Estonian)

- Analysis of the Kalmykian tale corpus", by B. B. Goryaeva (In Russian).

- Digital collection of Norwegian Eventyr and Legends by the University of Oslo (In Norwegian)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aarne%E2%80%93Thompson%E2%80%93Uther_Index

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fan_fiction

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Diary

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fiction_writing

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amateur

An avocation is an activity that someone engages in as a hobby outside their main occupation. There are many examples of people whose professions were the ways that they made their livings, but for whom their activities outside their workplaces were their true passions in life.[1][2] Occasionally, as with Lord Baden-Powell and others, people who pursue an avocation are more remembered by history for their avocation than for their professional career.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Avocation

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Handicraft

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hobby

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_amateur_mathematicians

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amateur_professionalism

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gild

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Civilian

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neutral_country

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Traditional_story

The first collectors to attempt to preserve not only the plot and characters of the tale, but also the style in which they were told, was the Brothers Grimm, collecting German fairy tales; ironically, this meant although their first edition (1812 & 1815)[40] remains a treasure for folklorists, they rewrote the tales in later editions to make them more acceptable, which ensured their sales and the later popularity of their work.[54]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fairy_tale

Cutlery for children. Detail showing fairy-tale scenes: Snow White, Little Red Riding Hood, Hansel and Gretel.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fairy_tale

Many fairy tales feature an absentee mother, as an example Beauty and the Beast, The Little Mermaid, Little Red Riding Hood and Donkeyskin, where the mother is deceased or absent and unable to help the heroines. Mothers are depicted as absent or wicked in the most popular contemporary versions of tales like Rapunzel, Snow White, Cinderella and Hansel and Gretel, however, some lesser known tales or variants such as those found in volumes edited by Angela Carter and Jane Yolen depict mothers in a more positive light.[95]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fairy_tale

Carter's protagonist in The Bloody Chamber is an impoverished piano student married to a Marquis who was much older than herself to "banish the spectre of poverty". The story is a variant on Bluebeard, a tale about a wealthy man who murders numerous young women. Carter's protagonist, who is unnamed, describes her mother as "eagle-featured" and "indomitable". Her mother is depicted as a woman who is prepared for violence, instead of hiding from it or sacrificing herself to it. The protagonist recalls how her mother kept an "antique service revolver" and once "shot a man-eating tiger with her own hand."[95]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fairy_tale

John Bauer's illustration of trolls and a princess from a collection of Swedish fairy tales

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fairy_tale

Beauty and the Beast, illustration by Warwick Goble

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fairy_tale

Vladimir Propp specifically studied a collection of Russian fairy tales, but his analysis has been found useful for the tales of other countries.[118] Having criticized Aarne-Thompson type analysis for ignoring what motifs did in stories, and because the motifs used were not clearly distinct,[119] he analyzed the tales for the function each character and action fulfilled and concluded that a tale was composed of thirty-one elements ('functions') and seven characters or 'spheres of action' ('the princess and her father' are a single sphere). While the elements were not all required for all tales, when they appeared they did so in an invariant order – except that each individual element might be negated twice, so that it would appear three times, as when, in Brother and Sister, the brother resists drinking from enchanted streams twice, so that it is the third that enchants him.[120] Propp's 31 functions also fall within six 'stages' (preparation, complication, transference, struggle, return, recognition), and a stage can also be repeated, which can affect the perceived order of elements.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fairy_tale

Many fairy tales have been interpreted for their (purported) significance. One mythological interpretation saw many fairy tales, including Hansel and Gretel, Sleeping Beauty, and The Frog King, as solar myths; this mode of interpretation subsequently became rather less popular.[125] Freudian, Jungian, and other psychological analyses have also explicated many tales, but no mode of interpretation has established itself definitively.[126]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fairy_tale

Ballet, too, is fertile ground for bringing fairy tales to life. Igor Stravinsky's first ballet, The Firebird uses elements from various classic Russian tales in that work.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fairy_tale

- Hans Stumme, scholar and collector of North African folklore (1864–1936)

- Goldberg, Christine (2010). "The Forgotten Bride". Marvels & Tales. 24 (2): 345–347. JSTOR 41388963. Gale A241862735 Project MUSE 402467 ProQuest 763256457.

Africa

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fairy_tale

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Collections_of_fairy_tales

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/World_Tales

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grimms%27_Fairy_Tales

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/One_Thousand_and_One_Nights

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hero%27s_journey

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fairy_tale

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fairy_Tales_(Cummings_book)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nursery_rhyme

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fairy_tale_parody

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fantasy

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Folklore

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Narrative

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fairy

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Fantasy_genres

| Fairytale | |

|---|---|

Poster | |

| Directed by | Alexander Sokurov |

| Written by | Alexander Sokurov |

| Produced by | Nikolay Yankin |

| Music by | Murat Kabardokov |

Production company | Intonations |

Release date |

|

Running time | 78 minutes |

| Countries |

|

| Languages |

|

Fairytale (Russian: Сказка, romanized: Skazka) is a 2022 experimental animated fantasy film directed by Alexander Sokurov. It depicts conversations in purgatory among Adolf Hitler, Benito Mussolini, Joseph Stalin, and Winston Churchill, using archival footage, and also features Jesus and Napoleon.[1][2][3]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fairytale_(film)

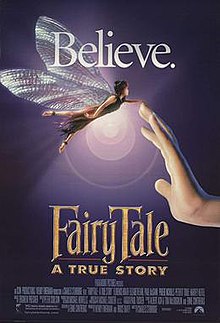

| FairyTale: A True Story | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Charles Sturridge |

| Screenplay by | Ernie Contreras |

| Story by | Albert Ash Tom McLoughlin Ernie Contreras |

| Produced by | Bruce Davey Wendy Finerman |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Michael Coulter |

| Edited by | Peter Coulson |

| Music by | Zbigniew Preisner |

Production companies | Icon Productions Icon Entertainment International Wendy Finerman Productions Anna K. Production C.V.[1] |

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures (United States) Warner Bros. (International)[2][3] |

Release date | 24 October 1997 (United States) |

Running time | 99 minutes |

| Countries | United States France |

| Language | English |

| Box office | $18 million |

FairyTale: A True Story is a 1997 fantasy drama film directed by Charles Sturridge and produced by Bruce Davey and Wendy Finerman. It is loosely based on the story of the Cottingley Fairies, and follows two children in 1917 England who take a photograph soon believed to be the first scientific evidence of the existence of fairies. The film was produced by Icon Productions and was distributed by Paramount Pictures in the United States and by Warner Bros. internationally.[2][3]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/FairyTale:_A_True_Story

A fairy tale is a story featuring folkloric characters.

Fairy Tale(s), Faerie Tale(s), Faery Tale(s),or Fairytale(s) may also refer to:

Films

- Fairytale (film), a 2022 experimental film

- Fairy Tales (film), a 1978 sex comedy

- FairyTale: A True Story, a 1997 film based on the story of the Cottingley Fairies

Games

- Fairy Tale (game), a card game

- A Fairy Tale (video game), a 2009 puzzle video game created by Reflexive Entertainment

- The Faery Tale Adventure, a 1987 adventure video game

Literature

- Faerie Tale, a 1988 fantasy novel by Raymond E. Feist

- Fairy Tales (Cummings book), a book of fairy tales by e.e. cummings

- Fairy Tales (Jones book), a book of children's stories by Terry Jones

- Fairy Tale (novel), a 2022 novel by Stephen King

- Fairytale fantasy, a subgenre of fantasy that uses of folklore motifs and plots

- Several collections of fairy tales with distinguished illustrations by John Dickson Batten, published by Joseph Jacobs

Music

- Fairy Tale (Suk), an orchestral suite by Josef Suk

Albums

- Fairy Tale (Mai Kuraki album), or the title song

- Fairy Tale (Michael Wong album), or the title song

- Fairy Tales (Divine album), 1998

- Fairy Tales (Mother Gong album), 1979

- Fairy Tales, a 2014 album by Futurecop!

- Fairytale (album), a 1965 album by Donovan

- Fairytales (Alexander Rybak album), or the title song (see below)

- Fairytales (Desirée Sparre-Enger album), or the title song

Songs

- "Fairy Tale", by Shaman from Ritual

- "Fairy Tale", by Loona 1/3 from Love & Live

- "Fairy Tales" (Anita Baker song), 1991

- "Fairytale" (Kalafina song)

- "Fairytale" (Pointer Sisters song), 1974

- "Fairytale" (Alexander Rybak song), the winning entry of the Eurovision Song Contest 2009

- "Fairytale" (Eneda Tarifa song), the Albanian entry for the Eurovision Song Contest 2016

- "Fairytale", by Sonata Arctica from The Ninth Hour

- "Fairytale", by Sara Bareilles from Careful Confessions and Little Voice

- "Fairytale", a 1976 single by Dana

- "Fairytale", by Edguy from Vain Glory Opera, 1998

- "Fairytale", by Enya from Enya

- "Fairytale", by Heavenly from Coming from the Sky

- "Fairytale", by Justin Bieber featuring Jaden Smith from Believe, 2012

- "Fairytales" (2 Brothers on the 4th Floor song), 1996

Television

- Fairy Tale (TV series), a Canadian LGBT dating show

- Fairy Tales (TV series), a 2008 British drama anthology series

- "Fairy Tale", the 12th episode in season 2 of the Disney Channel sitcom Wizards of Waverly Place

- "Fairytale" (The Crown), an episode of The Crown

- JJ Villard's Fairy Tales, an adult animated television series

Other uses

- A Fairy Tale (ballet), a ballet by Marius Petipa and Richter

- Fairy Tale (color), a shade of pink

See also

- Fairy godmother (disambiguation)

- Fairy Tail, a 2006 manga by Hiro Mashima

- Tooth Fairy (disambiguation)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fairy_tale_(disambiguation)

In storytelling, the heroine's journey is a female-centric version of the Hero's journey template developed and inspired by various authors[who?] who felt that the Hero's Journey did not fully encompass the journey that a female protagonist goes through in a story.

The heroine's journey came about in 1990 when Maureen Murdock, a Jungian psychotherapist and a student of Joseph Campbell, published a self-help book called The Heroine's Journey: Woman's Quest for Wholeness in response to Campbell's Hero's Journey model. She developed the guide while working with her female patients. Murdock stated that the heroine's journey is the healing of the wounding of the feminine that exists deep within her and the culture.[1] Murdock explains, "The feminine journey is about going down deep into soul, healing and reclaiming, while the masculine journey is up and out, to spirit."[2]

Other authors such as Victoria Lynn Schmidt have created similar versions of the Heroine's Journey based on Murdock's. Schmidt's version changes some stages of Murdock's to help the model fit a bigger range of topics and experiences.[3]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Heroine%27s_journey

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nati

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Venus

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aphrodite

The title of Hero is presented by various governments in recognition of acts of self-sacrifice to the state, and great achievements in combat or labor. It is originally a Soviet-type honor, and is continued by several nations including Belarus, Russia, and Ukraine. It was also awarded to cities and fortresses for collective efforts in heroic feats. Each hero receives a medal for public display, special privileges and rights for life, and the admiration and respect of the nation. Some countries without Soviet connections also award Hero honours.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hero_(title)

The first hero title established, "Hero of the Soviet Union", was created by decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR on 16 April 1934.[1] The identifying badge, the "Gold Star Medal", was not created until 1 August 1939. The title was awarded for "personal or collective deeds of heroism rendered to the USSR or socialist society" and it was awarded to both military personnel and civilians.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hero_(title)

First edition cover | |

| Author | Vladimir Nabokov |

|---|---|

| Country | France |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Novel |

| Publisher | Olympia Press |

Publication date | 1955 |

| Pages | 336 112,473 words[1] |

Lolita is a 1955 novel written by Russian-American novelist Vladimir Nabokov. The novel is notable for its controversial subject: the protagonist and unreliable narrator, a middle-aged literature professor under the pseudonym Humbert Humbert, is obsessed with a 12-year-old girl, Dolores Haze, whom he kidnaps and sexually abuses after becoming her stepfather. "Lolita", the Spanish nickname for Dolores, is what he calls her privately. The novel was originally written in English and first published in Paris in 1955 by Olympia Press.

The novel has been twice adapted into film: first by Stanley Kubrick in 1962, and later by Adrian Lyne in 1997. It has also been adapted several times for the stage and has been the subject of two operas, two ballets, and an acclaimed, but commercially unsuccessful, Broadway musical. It has been included in many lists of best books, such as Time's List of the 100 Best Novels, Le Monde's 100 Books of the Century, Bokklubben World Library, Modern Library's 100 Best Novels, and The Big Read.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lolita

In visual arts, a model sheet, also known as a character board, character sheet, character study or simply a study, is a document used to help standardize the appearance, poses, and gestures of a character in arts such as animation, comics, and video games.[1]

Model sheets are required when multiple artists are involved in the production of an animated film, game, or comic to help maintain continuity in characters from scene to scene. In animation, one animator may only do one shot out of the several hundred that are required to complete an animated feature film. A character not drawn according to the production's standardized model is referred to as off-model.[2]

Model sheets are also used for references in 3D modeling to guide proper proportions of models.[3]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Model_sheet

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Temperament_and_Character_Inventory

| Harm avoidance | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Psychiatry |

Harm avoidance (HA) is a personality trait characterized by excessive worrying; pessimism; shyness; and being fearful, doubtful, and easily fatigued. In MRI studies HA was correlated with reduced grey matter volume in the orbito-frontal, occipital and parietal regions.[1][2]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harm_avoidance

Versions

Originally developed in English, TCI has been translated to other languages, e.g., Swedish,[6] Japanese, Dutch, German, Polish, Korean,[7] Finnish, Chinese and French. There is also a revised version TCI-R. Whereas the original TCI had statements for which the subject should indicate true or false, the TCI-R has a five-point rating for each statement. The two versions hold 189 of the 240 statements in common. The revised version has been translated into Spanish,[8] French,[9] Czech,[10] and Italian.[11]

The number of subscales on the different top level traits differ between TCI and TCI-R. The subscales of the TCI-R are:

- Novelty seeking (NS)

- Exploratory excitability (NS1)

- Impulsiveness (NS2)

- Extravagance (NS3)

- Disorderliness (NS4)

- Harm avoidance (HA)

- Anticipatory worry (HA1)

- Fear of uncertainty (HA2)

- Shyness (HA3)

- Fatigability (HA4)

- Reward dependence (RD)

- Sentimentality (RD1)

- Openness to warm communication (RD2)

- Attachment (RD3)

- Dependence (RD4)

- Persistence (PS)

- Eagerness of effort (PS1)

- Work hardened (PS2)

- Ambitious (PS3)

- Perfectionist (PS4)

- Self-directedness (SD)

- Responsibility (SD1)

- Purposeful (SD2)

- Resourcefulness (SD3)

- Self-acceptance (SD4)

- Enlightened second nature (SD5)

- Cooperativeness (C)

- Social acceptance (C1)

- Empathy (C2)

- Helpfulness (C3)

- Compassion (C4)

- Pure-hearted conscience (C5)

- Self-transcendence (ST)

- Self-forgetful (ST1)

- Transpersonal identification (ST2)

- Spiritual acceptance (ST3)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Temperament_and_Character_Inventory

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/mask

Relationship to other personality models

Cloninger argued that the Five Factor model does not assess domains of personality relevant to personality disorders such as autonomy, moral values, and aspects of maturity and self-actualization considered in humanistic and transpersonal psychology. Cloninger argued that these domains are captured by self-directedness, cooperativeness, and self-transcendence respectively.[5] He also argued that personality factors defined as independent by factor analysis, such as neuroticism and introversion, may actually share underlying etiological factors.

Research has found that all of the TCI dimensions are each related substantially to at least one of the dimensions in the Five Factor Model,[3] Eysenck's model, Zuckerman's alternative five:

- Harm avoidance is strongly positively associated with neuroticism and inversely associated with extraversion.

- Novelty seeking is most strongly associated with extraversion, although it also has a moderate positive association with openness to experience and a moderate negative association with conscientiousness.

- Persistence has a positive association with conscientiousness.

- Reward dependence is most strongly associated with extraversion, although it also has a moderate positive association with openness to experience.

- Cooperativeness is most strongly associated with agreeableness.

- Self-directedness has a strong negative association with neuroticism and a positive association with conscientiousness.

- Self-transcendence had a positive association with openness to experience and to a lesser extent extraversion.

- Relationships have also been found between the TCI dimensions and traits specific to the models of Zuckerman and Eysenck respectively.[3]

- Novelty seeking is related to Impulsive sensation seeking in Zuckerman's alternative five model and to psychoticism in Eysenck's model.

- Zuckerman and Cloninger have contended that Harm Avoidance is a composite dimension comprising neurotic introversion at one end and stable extraversion at the other end.

- Persistence is related to Zuckerman's Activity scale and inversely to psychoticism.

- Cooperativeness is inversely related to Zuckerman's Aggression-hostility scale and to psychoticism.

- Self-transcendence has no equivalent in either Zuckerman or Eysenck's model as neither model recognises openness to experience.[3]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Temperament_and_Character_Inventory

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Revised_NEO_Personality_Inventory

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Agreeableness

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conscientiousness

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neuroticism

Neuroticism has been included as one of the four dimensions that comprise core self-evaluations, one's fundamental appraisal of oneself, along with locus of control, self-efficacy, and self-esteem.[17] The concept of core self-evaluations was first examined by Judge, Locke, and Durham (1997),[17] and since then evidence has been found to suggest these have the ability to predict several work outcomes, specifically, job satisfaction and job performance.[17][18][19][20][21]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neuroticism

Internal consistency reliability of the International English Mini-Markers for the Neuroticism (emotional stability) measure for native English-speakers is reported as 0.84, and that for non-nati

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neuroticism

There is a risk of selection bias in surveys of neuroticism; a 2012 review of N-scores said that "many studies used samples drawn from privileged and educated populations".[6]

Neuroticism is highly correlated with the startle reflex in response to fearful conditions and inversely correlated with it in response to disgusting or repulsive stimuli.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neuroticism

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gray%27s_biopsychological_theory_of_personality

Thompson (2008)[1] systematically revised these measures to develop the International English Mini-Markers which has superior validity and reliability in populations both within and outside North America. Internal consistency reliability of the International English Mini-Markers for the Neuroticism (emotional stability) measure for native English-speakers is reported as 0.84, and that for non-native English-speakers is 0.77.[1]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neuroticism

Questions used in many neuroticism scales overlap with instruments used to assess mental disorders like anxiety disorders (especially social anxiety disorder) and mood disorders (especially major depressive disorder), which can sometimes confound efforts to interpret N scores and makes it difficult to determine whether each of neuroticism and the overlapping mental disorders might cause the other, or if both might stem from other cause. Correlations can be identified.[6]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neuroticism

The authors interpret these findings as suggesting that mental noise is "highly specific in nature" as it is related most strongly to attention slips triggered endogenously by associative memory. In other words, this may suggest that mental noise is mostly task-irrelevant cognitions such as worries and preoccupations.[30]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neuroticism

Terror management theory

According to terror management theory (TMT) neuroticism is primarily caused by insufficient anxiety buffers against unconscious death anxiety.[34] These buffers consist of:

- Cultural worldviews that impart life with a sense of enduring meaning, such as social continuity beyond one's death, future legacy and afterlife beliefs.

- A sense of personal value, or the self-esteem in the cultural worldview context, an enduring sense of meaning.

While TMT agrees with standard evolutionary psychology accounts that the roots of neuroticism in Homo sapiens or its ancestors are likely in adaptive sensitivities to negative outcomes, it posits that once Homo sapiens achieved a higher level of self-awareness, neuroticism increased enormously, becoming largely a spandrel, a non-adaptive byproduct of our adaptive intelligence, which resulted in a crippling awareness of death that threatened to undermine other adaptive functions. This overblown anxiety thus needed to be buffered via intelligently creative, but largely fictitious and arbitrary notions of cultural meaning and personal value. Since highly religious or supernatural conceptions of the world provide "cosmic" personal significance and literal immortality, they are deemed to offer the most efficient buffers against death anxiety and neuroticism. Thus, historically, the shift to more materialistic and secular cultures—starting in the neolithic, and culminating in the industrial revolution—is deemed to have increased neuroticism.[34]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neuroticism

In children and adolescents, psychologists speak of temperamental negative affectivity that, during adolescence, develops into the neuroticism personality domain.[26] Mean neuroticism levels change throughout the lifespan as a function of personality maturation and social roles,[36][37] but also the expression of new genes.[38] Neuroticism in particular was found to decrease as a result of maturity by decreasing through age 40 and then leveling off.[26] Generally speaking, the influence of environments on neuroticism increases over the lifespan,[38] although people probably select and evoke experiences based on their neuroticism levels.[27]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neuroticism

Due to the facets associated with neuroticism, it can be viewed as a negative personality trait. A common perception of the personality trait most closely associated with risky behaviors is extraversion, due to the correlated adjectives such as adventurous, enthusiastic, and outgoing.[50]These adjectives allow the individual to feel the positive emotions associated with risk-taking. However, neuroticism can also be a contributing factor, just for different reasons. As anxiety is one of the facets of neuroticism, it can lead to indulgence in anxiety-based maladaptive and risky behaviors. [51]Neuroticism is considerably stable over time, and research has shown that individuals with higher levels of neuroticism may prefer short-term solutions, such as risky behaviors, and neglect the long-term costs. [52]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neuroticism

| |||

| |||

| |||

| |||

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neuroticism

| Nightmare disorder | |

|---|---|

| |

| The Nightmare, by Johann Heinrich Füssli | |

| Specialty | Psychiatry |

| Frequency | c. 4%[1] |

Nightmare disorder is a sleep disorder characterized by repeated intense nightmares that most often center on threats to physical safety and security.[2] The nightmares usually occur during the REM stage of sleep, and the person who experiences the nightmares typically remembers them well upon waking.[2] More specifically, nightmare disorder is a type of parasomnia, a subset of sleep disorders categorized by abnormal movement or behavior or verbal actions during sleep or shortly before or after. Other parasomnias include sleepwalking, sleep terrors, bedwetting, and sleep paralysis.[3]

Nightmare disorders can be confused with sleep terror disorders.[4] The difference is that after a sleep terror episode, the patient wakes up with more dramatic symptoms than with a nightmare disorder, such as screaming and crying.[4] Furthermore, they don't remember the reason of the fear, while a patient with a nightmare disorder remembers every detail of the dream.[4] Finally, the sleep terrors usually occur during NREM Sleep.[5][6]

Nightmares also have to be distinguished from bad dreams, which are less emotionally intense.[7] Furthermore, nightmares contain more scenes of aggression than bad dreams and more unhappy endings.[7] Finally, people experiencing nightmares feel more fear than with bad dreams.[7]

The treatment depends on whether or not there is a comorbid PTSD diagnosis.[1] About 4% of American adults are affected.[1] Studies examining nightmare disorders have found that the prevalence rates range from 2-6% with the prevalence being similar in the USA, Canada, France, Iceland, Sweden, Belgium, Finland, Austria, Japan, and the Middle East.[8]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nightmare_disorder

| Parasomnia | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Sleep medicine, psychology |

Parasomnias are a category of sleep disorders that involve abnormal movements, behaviors, emotions, perceptions, and dreams that occur while falling asleep, sleeping, between sleep stages, or during arousal from sleep. Parasomnias are dissociated sleep states which are partial arousals during the transitions between wakefulness, NREM sleep, and REM sleep, and their combinations.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Parasomnia

The newest version of the International Classification of Sleep Disorders (ICSD, 3rd. Ed.) uses State Dissociation as the paradigm for parasomnias.[1][2] Unlike before, where wakefulness, non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep, and rapid eye movement (REM) sleep were considered exclusive states, research has shown that combinations of these states are possible and thus, may result in unusual unstable states that could eventually manifest as parasomnias or as altered levels of awareness.[1][3][4][5][6][7]

Although the previous definition is technically correct, it contains flaws. The consideration of the State Dissociation paradigm facilitates the understanding of the sleep disorder and provides a classification of 10 core categories.[1][2]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Parasomnia

Some NREM parasomnias (sleep-walking, night-terrors, and confusional arousal) are common during childhood but decrease in frequency with increasing age. They can be triggered in certain individuals, by alcohol, sleep deprivation, physical activity, emotional stress, depression, medications, or a fevered illness. These disorders of arousal can range from confusional arousals, somnambulism, to night terrors. Other specific disorders include sleepeating, sleep sex, teeth grinding, rhythmic movement disorder, restless legs syndrome, and somniloquy.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Parasomnia

Nightmares are like dreams primarily associated with REM sleep. Nightmare disorder is defined as recurrent nightmares associated with awakening dysphoria that impairs sleep or daytime functioning.[1][2] It is rare in children, however persists until adulthood.[11][33] About 2/3 of the adult population report experiencing nightmares at least once in their life.[11]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Parasomnia

Night terror, also called sleep terror, is a sleep disorder causing feelings of panic or dread and typically occurring during the first hours of stage 3–4 non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep[1] and lasting for 1 to 10 minutes.[2] It can last longer, especially in children.[2] Sleep terror is classified in the category of NREM-related parasomnias in the International Classification of Sleep Disorders.[3] There are two other categories: REM-related parasomnias and other parasomnias.[3] Parasomnias are qualified as undesirable physical events or experiences that occur during entry into sleep, during sleep, or during arousal from sleep.[4]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Night_terror

Sleep-related hallucinations are brief episodes of dream-like imagery that can be of any sensory modality, i.e., auditory, visual, or tactile.[2] They are differentiated between hypnagogic hallucination, that occur at sleep onset, and hypnapompic hallucinations, which occur at the transition of sleep to awakening.[2] Although normal individuals have reported nocturnal hallucinations, they are more frequent in comorbidity with other sleep disorders, e.g. narcolepsy.[1][2][37]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Parasomnia

Hypnopompia (also known as hypnopompic state) is the state of consciousness leading out of sleep, a term coined by the psychical researcher Frederic Myers. Its mirror is the hypnagogic state at sleep onset; though often conflated, the two states are not identical and have a different phenomenological character. Hypnopompic and hypnagogic hallucinations are frequently accompanied by sleep paralysis, which is a state wherein one is consciously aware of one's surroundings but unable to move or speak.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hypnopompia

See also

- Dyssomnia

- Insomnia

- Rhythmic movement disorder

- Sleep medicine

- Sleep paralysis

- Alien abduction, which some investigators claim is caused by parasomnia.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Parasomnia

Anorexia nervosa (AN), often referred to simply as anorexia,[12] is an eating disorder characterized by low weight, food restriction, body image disturbance, fear of gaining weight, and an overpowering desire to be thin.[1]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anorexia_nervosa

| Hypersomnia | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Hypersomnolence |

| Specialty | Psychiatry, neurology, sleep medicine |

Hypersomnia is a neurological disorder of excessive time spent sleeping or excessive sleepiness. It can have many possible causes (such as seasonal affective disorder) and can cause distress and problems with functioning.[1] In the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), hypersomnolence, of which there are several subtypes, appears under sleep-wake disorders.[2]

Hypersomnia is a pathological state characterized by a lack of alertness during the waking episodes of the day.[3] It is not to be confused with fatigue, which is a normal physiological state.[4] Daytime sleepiness appears most commonly during situations where little interaction is needed.[5]

Since hypersomnia impairs patients' attention levels (wakefulness), quality of life may be impacted as well.[6] This is especially true for people whose jobs request high levels of attention, such as in the healthcare field.[6]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hypersomnia

A nightmare, also known as a bad dream,[1] is an unpleasant dream that can cause a strong emotional response from the mind, typically fear but also despair, anxiety, disgust or great sadness. The dream may contain situations of discomfort, psychological or physical terror, or panic. After a nightmare, a person will often awaken in a state of distress and may be unable to return to sleep for a short period of time.[2] Recurrent nightmares may require medical help, as they can interfere with sleeping patterns and cause insomnia.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nightmare

| Other specified feeding or eating disorder (OSFED) | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Psychiatry |

Other specified feeding or eating disorder (OSFED) is a subclinical DSM-5 category that, along with unspecified feeding or eating disorder (UFED), replaces the category formerly called eating disorder not otherwise specified (EDNOS) in the DSM-IV-TR.[1] It captures feeding disorders and eating disorders of clinical severity that do not meet diagnostic criteria for anorexia nervosa (AN), bulimia nervosa (BN), binge eating disorder (BED), avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID), pica, or rumination disorder.[2] OSFED includes five examples:

- atypical anorexia nervosa,

- atypical bulimia nervosa of low frequency and/or limited duration,

- binge eating disorder of low frequency and/or limited duration,

- purging disorder, and

- night eating syndrome (NES).[2]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Other_specified_feeding_or_eating_disorder

| Insomnia | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Sleeplessness, trouble sleeping |

| |

| Depiction of insomnia from the 14th century medical manuscript Tacuinum Sanitatis | |

| Pronunciation | |

| Specialty | Psychiatry, sleep medicine |

| Symptoms | Trouble sleeping, daytime sleepiness, low energy, irritability, depressed mood[1] |

| Complications | Motor vehicle collisions[1] |

| Causes | Unknown, psychological stress, chronic pain, heart failure, hyperthyroidism, heartburn, restless leg syndrome, others[2] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms, sleep study[3] |

| Differential diagnosis | Delayed sleep phase disorder, restless leg syndrome, sleep apnea, psychiatric disorder[4] |

| Treatment | Sleep hygiene, cognitive behavioral therapy, sleeping pills[5][6][7] |

| Frequency | ~20%[8][9][10] |

Insomnia, also known as sleeplessness, is a sleep disorder in which people have trouble sleeping.[1] They may have difficulty falling asleep, or staying asleep for as long as desired.[9][11] Insomnia is typically followed by daytime sleepiness, low energy, irritability, and a depressed mood.[1] It may result in an increased risk of motor vehicle collisions, as well as problems focusing and learning.[1] Insomnia can be short term, lasting for days or weeks, or long term, lasting more than a month.[1] The concept of the word insomnia has two possibilities: insomnia disorder and insomnia symptoms, and many abstracts of randomized controlled trials and systematic reviews often underreport on which of these two possibilities the word insomnia refers to.[12]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Insomnia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Parasomnia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Somatic_symptom_disorder

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adjustment_disorder

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Social_anxiety

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Social_anxiety_disorder

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Generalized_anxiety_disorder

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Depersonalization-derealization_disorder

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dissociative_identity_disorder

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fugue_state

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mass_psychogenic_illness

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Delusion

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Illusion

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mania

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thought_broadcasting

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ideas_and_delusions_of_reference

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grandiose_delusions

This condition is more common among people who have poor hearing or sight. Also, ongoing stressors have been associated with a higher possibility of developing delusions. Examples of such stressors are immigration, low socioeconomic status, and even possibly the accumulation of smaller daily struggles.[16]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Delusion

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cotard_delusion

Higher levels of dopamine qualify as a symptom of disorders of brain function. That they are needed to sustain certain delusions was examined by a preliminary study on delusional disorder (a psychotic syndrome) instigated to clarify if schizophrenia had a dopamine psychosis.[18] There were positive results - delusions of jealousy and persecution had different levels of dopamine metabolite HVA and homovanillyl alcohol (which may have been genetic). These can be only regarded as tentative results; the study called for future research with a larger population.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Delusion

On the influence of personality, it has been said: "Jaspers considered there is a subtle change in personality due to the illness itself; and this creates the condition for the development of the delusional atmosphere in which the delusional intuition arises."[22]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Delusion

The aberrant salience model suggests that delusions are a result of people assigning excessive importance to irrelevant stimuli. In support of this hypothesis, regions normally associated with the salience network demonstrate reduced grey matter in people with delusions, and the neurotransmitter dopamine, which is widely implicated in salience processing, is also widely implicated in psychotic disorders.[citation needed]

Specific regions have been associated with specific types of delusions. The volume of the hippocampus and parahippocampus is related to paranoid delusions in Alzheimer's disease, and has been reported to be abnormal post mortem in one person with delusions. Capgras delusions have been associated with occipito-temporal damage and may be related to failure to elicit normal emotions or memories in response to faces.[26]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Delusion

It is important to distinguish true delusions from other symptoms such as anxiety, fear, or paranoia. To diagnose delusions a mental state examination may be used. This test includes appearance, mood, affect, behavior, rate and continuity of speech, evidence of hallucinations or abnormal beliefs, thought content, orientation to time, place and person, attention and concentration, insight and judgment, as well as short-term memory.[37]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Delusion

Furthermore, when beliefs involve value judgments, only those which cannot be proven true are considered delusions. For example: a man claiming that he flew into the Sun and flew back home. This would be considered a delusion,[42] unless he were speaking figuratively, or if the belief had a cultural or religious source. Only the first three criteria remain cornerstornes of the current definition of a delusion in the DSM-5.

Robert Trivers writes that delusion is a discrepancy in relation to objective reality, but with a firm conviction in reality of delusional ideas, which is manifested in the "affective basis of delusion."[43]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Delusion

Anthropologist David Graeber have criticized psychiatry's assumption that an absurd belief goes from being delusional to "being there for a reason" merely because it is shared by many people by arguing that just as genetic pathogens like viruses can take advantage of an organism without benefitting said organism, memetic phenomena can spread while being harmful to societies, implying that entire societies can become ill.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Delusion

See also

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Delusion

Folie à deux (French- 'folly of two', or 'madness [shared] by two'), additionally known as shared psychosis[2] or shared delusional disorder (SDD), is a psychiatric syndrome in which symptoms of a delusional belief, and sometimes hallucinations,[3] are transmitted from one individual to another.[4] The same syndrome shared by more than two people may be called folie à trois ('three') or quatre ('four'); and further, folie en famille ('family madness') or even folie à plusieurs ('madness of several').

The disorder, first conceptualized in 19th-century French psychiatry by Charles Lasègue and Jules Falret, is also known as Lasègue–Falret syndrome.[3][5]

Recent psychiatric classifications refer to the syndrome as shared psychotic disorder (DSM-4 – 297.3) and induced delusional disorder (ICD-10 – F24), although the research literature largely uses the original name.

This disorder is not in the current, fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), which considers the criteria to be insufficient or inadequate. DSM-5 does not consider Shared Psychotic Disorder (Folie à Deux) as a separate entity; rather, the physician should classify it as "Delusional Disorder" or in the "Other Specified Schizophrenia Spectrum and Other Psychotic Disorder".

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Folie_%C3%A0_deux

A conspiracy theory is an explanation for an event or situation that asserts the existence of a conspiracy by powerful and sinister groups, often political in motivation,[3][4][5] when other explanations are more probable.[3][6][7] The term generally has a negative connotation, implying that the appeal of a conspiracy theory is based in prejudice, emotional conviction, or insufficient evidence.[8] A conspiracy theory is distinct from a conspiracy; it refers to a hypothesized conspiracy with specific characteristics, including but not limited to opposition to the mainstream consensus among those who are qualified to evaluate its accuracy, such as scientists or historians.[9][10][11]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conspiracy_theory

The Eye of Providence, as seen on the US $1 bill, has been perceived by some to be evidence of a conspiracy linking the Founding Fathers of the United States to the Illuminati.[1]: 58 [2]: 47–49

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conspiracy_theory

A conspiracy theory is an explanation for an event or situation that asserts the existence of a conspiracy by powerful and sinister groups, often political in motivation,[3][4][5] when other explanations are more probable.[3][6][7] The term generally has a negative connotation, implying that the appeal of a conspiracy theory is based in prejudice, emotional conviction, or insufficient evidence.[8] A conspiracy theory is distinct from a conspiracy; it refers to a hypothesized conspiracy with specific characteristics, including but not limited to opposition to the mainstream consensus among those who are qualified to evaluate its accuracy, such as scientists or historians.[9][10][11]

Conspiracy theories are generally designed to resist falsification and are reinforced by circular reasoning: both evidence against the conspiracy and absence of evidence for it are misinterpreted as evidence of its truth,[8][12] whereby the conspiracy becomes a matter of faith rather than something that can be proven or disproven.[1][13] Studies have linked belief in conspiracy theories to distrust of authority and political cynicism.[14][15][16] Some researchers suggest that conspiracist ideation—belief in conspiracy theories—may be psychologically harmful or pathological,[17][18] and that it is correlated with lower analytical thinking, low intelligence, psychological projection, paranoia, and Machiavellianism.[19] Psychologists usually attribute belief in conspiracy theories to a number of psychopathological conditions such as paranoia, schizotypy, narcissism, and insecure attachment,[9] or to a form of cognitive bias called "illusory pattern perception".[20][21] However, a 2020 review article found that most cognitive scientists view conspiracy theorizing as typically nonpathological, given that unfounded belief in conspiracy is common across cultures both historical and contemporary, and may arise from innate human tendencies towards gossip, group cohesion, and religion.[9]

Historically, conspiracy theories have been closely linked to prejudice, propaganda, witch hunts, wars, and genocides.[22][23][24][25] They are often strongly believed by the perpetrators of terrorist attacks, and were used as justification by Timothy McVeigh and Anders Breivik, as well as by governments such as Nazi Germany, the Soviet Union,[22] and Turkey.[26] AIDS denialism by the government of South Africa, motivated by conspiracy theories, caused an estimated 330,000 deaths from AIDS,[27][28][29] QAnon and denialism about the 2020 United States presidential election results led to the January 6 United States Capitol attack,[30][31][32] while belief in conspiracy theories about genetically modified foods led the government of Zambia to reject food aid during a famine,[23] at a time when three million people in the country were suffering from hunger.[33] Conspiracy theories are a significant obstacle to improvements in public health,[23][34] encouraging opposition to vaccination and water fluoridation among others, and have been linked to outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases.[23][27][34][35] Other effects of conspiracy theories include reduced trust in scientific evidence,[23][36] radicalization and ideological reinforcement of extremist groups,[22][37] and negative consequences for the economy.[22]

Conspiracy theories once limited to fringe audiences have become commonplace in mass media, the internet, and social media,[9] emerging as a cultural phenomenon of the late 20th and early 21st centuries.[38][39][40][41] They are widespread around the world and are often commonly believed, some even being held by the majority of the population.[42][43][44] Interventions to reduce the occurrence of conspiracy beliefs include maintaining an open society and improving the analytical thinking skills of the general public.[42][43]

Origin and usage

The Oxford English Dictionary defines conspiracy theory as "the theory that an event or phenomenon occurs as a result of a conspiracy between interested parties; spec. a belief that some covert but influential agency (typically political in motivation and oppressive in intent) is responsible for an unexplained event." It cites a 1909 article in The American Historical Review as the earliest usage example,[45][46] although it also appeared in print for several decades before.[47]

The earliest known usage was by the American author Charles Astor Bristed, in a letter to the editor published in The New York Times on January 11, 1863.[48] He used it to refer to claims that British aristocrats were intentionally weakening the United States during the American Civil War in order to advance their financial interests.

England has had quite enough to do in Europe and Asia, without going out of her way to meddle with America. It was a physical and moral impossibility that she could be carrying on a gigantic conspiracy against us. But our masses, having only a rough general knowledge of foreign affairs, and not unnaturally somewhat exaggerating the space which we occupy in the world's eye, do not appreciate the complications which rendered such a conspiracy impossible. They only look at the sudden right-about-face movement of the English Press and public, which is most readily accounted for on the conspiracy theory.[48]

The word "conspiracy" derives from the Latin con- ("with, together") and spirare ("to breathe").

Robert Blaskiewicz comments that examples of the term were used as early as the nineteenth century and states that its usage has always been derogatory.[49] According to a study by Andrew McKenzie-McHarg, in contrast, in the nineteenth century the term conspiracy theory simply "suggests a plausible postulate of a conspiracy" and "did not, at this stage, carry any connotations, either negative or positive", though sometimes a postulate so-labeled was criticized.[50]

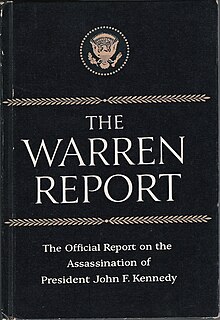

The term "conspiracy theory" is itself the subject of a conspiracy theory, which posits that the term was popularized by the CIA in order to discredit conspiratorial believers, particularly critics of the Warren Commission, by making them a target of ridicule.[51] In his 2013 book Conspiracy Theory in America, political scientist Lance deHaven-Smith wrote that the term entered everyday language in the United States after 1964, the year in which the Warren Commission published its findings on the Kennedy assassination, with The New York Times running five stories that year using the term.[52]

The idea that the CIA was responsible for popularising the term “conspiracy theory” was analyzed by Michael Butter, a Professor of American Literary and Cultural History at the University of Tübingen. Butter wrote in 2020 that the CIA document, Concerning Criticism of the Warren Report, which proponents of the theory use as evidence of CIA motive and intention, does not contain the phrase "conspiracy theory" in the singular, and only uses the term "conspiracy theories" once, in the sentence: "Conspiracy theories have frequently thrown suspicion on our organisation [sic], for example, by falsely alleging that Lee Harvey Oswald worked for us."[53]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conspiracy_theory

A conspiracy theory can be local or international, focused on single events or covering multiple incidents and entire countries, regions and periods of history.[10] According to Russell Muirhead and Nancy Rosenblum, historically, traditional conspiracism has entailed a "theory", but over time, "conspiracy" and "theory" have become decoupled, as modern conspiracism is often without any kind of theory behind it.[66][67]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conspiracy_theory

Walker's five kinds

Jesse Walker (2013) has identified five kinds of conspiracy theories:[68]

- The "Enemy Outside" refers to theories based on figures alleged to be scheming against a community from without.

- The "Enemy Within" finds the conspirators lurking inside the nation, indistinguishable from ordinary citizens.

- The "Enemy Above" involves powerful people manipulating events for their own gain.

- The "Enemy Below" features the lower classes working to overturn the social order.

- The "Benevolent Conspiracies" are angelic forces that work behind the scenes to improve the world and help people.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conspiracy_theory

Murray Rothbard argues in favor of a model that contrasts "deep" conspiracy theories to "shallow" ones. According to Rothbard, a "shallow" theorist observes an event and asks Cui bono? ("Who benefits?"), jumping to the conclusion that a posited beneficiary is responsible for covertly influencing events. On the other hand, the "deep" conspiracy theorist begins with a hunch and then seeks out evidence. Rothbard describes this latter activity as a matter of confirming with certain facts one's initial paranoia.[70]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conspiracy_theory

Lack of evidence

Belief in conspiracy theories is generally based not on evidence, but in the faith of the believer.[71] Noam Chomsky contrasts conspiracy theory to institutional analysis which focuses mostly on the public, long-term behavior of publicly known institutions, as recorded in, for example, scholarly documents or mainstream media reports.[72] Conspiracy theory conversely posits the existence of secretive coalitions of individuals and speculates on their alleged activities.[73][74] Belief in conspiracy theories is associated with biases in reasoning, such as the conjunction fallacy.[75]

Clare Birchall at King's College London describes conspiracy theory as a "form of popular knowledge or interpretation".[a] The use of the word 'knowledge' here suggests ways in which conspiracy theory may be considered in relation to legitimate modes of knowing.[b] The relationship between legitimate and illegitimate knowledge, Birchall claims, is closer than common dismissals of conspiracy theory contend.[77]

Theories involving multiple conspirators that are proven to be correct, such as the Watergate scandal, are usually referred to as investigative journalism or historical analysis rather than conspiracy theory.[78] By contrast, the term "Watergate conspiracy theory" is used to refer to a variety of hypotheses in which those convicted in the conspiracy were in fact the victims of a deeper conspiracy.[79] There are also attempts to analyze the theory of conspiracy theories (conspiracy theory theory) to ensure that the term "conspiracy theory" is used to refer to narratives that have been debunked by experts, rather than as a generalized dismissal.[80]

Rhetoric

Conspiracy theory rhetoric exploits several important cognitive biases, including proportionality bias, attribution bias, and confirmation bias.[27] Their arguments often take the form of asking reasonable questions, but without providing an answer based on strong evidence.[81] Conspiracy theories are most successful when proponents can gather followers from the general public, such as in politics, religion and journalism. These proponents may not necessarily believe the conspiracy theory; instead, they may just use it in an attempt to gain public approval. Conspiratorial claims can act as a successful rhetorical strategy to convince a portion of the public via appeal to emotion.[23]

Conspiracy theories typically justify themselves by focusing on gaps or ambiguities in knowledge, and then arguing that the true explanation for this must be a conspiracy.[54] In contrast, any evidence that directly supports their claims is generally of low quality. For example, conspiracy theories are often dependent on eyewitness testimony, despite its unreliability, while disregarding objective analyses of the evidence.[54]

Conspiracy theories are not able to be falsified and are reinforced by fallacious arguments. In particular, the logical fallacy circular reasoning is used by conspiracy theorists: both evidence against the conspiracy and an absence of evidence for it are re-interpreted as evidence of its truth,[8][12] whereby the conspiracy becomes a matter of faith rather than something that can be proved or disproved.[1][13] The epistemic strategy of conspiracy theories has been called "cascade logic": each time new evidence becomes available, a conspiracy theory is able to dismiss it by claiming that even more people must be part of the cover-up.[23][54] Any information that contradicts the conspiracy theory is suggested to be disinformation by the alleged conspiracy.[36] Similarly, the continued lack of evidence directly supporting conspiracist claims is portrayed as confirming the existence of a conspiracy of silence; the fact that other people have not found or exposed any conspiracy is taken as evidence that those people are part of the plot, rather than considering that it may be because no conspiracy exists.[27][54] This strategy lets conspiracy theories insulate themselves from neutral analyses of the evidence, and makes them resistant to questioning or correction, which is called "epistemic self-insulation".[27][54]

Conspiracy theorists often take advantage of false balance in the media. They may claim to be presenting a legitimate alternative viewpoint that deserves equal time to argue its case; for example, this strategy has been used by the Teach the Controversy campaign to promote intelligent design, which often claims that there is a conspiracy of scientists suppressing their views. If they successfully find a platform to present their views in a debate format, they focus on using rhetorical ad hominems and attacking perceived flaws in the mainstream account, while avoiding any discussion of the shortcomings in their own position.[23]

The typical approach of conspiracy theories is to challenge any action or statement from authorities, using even the most tenuous justifications. Responses are then assessed using a double standard, where failing to provide an immediate response to the satisfaction of the conspiracy theorist will be claimed to prove a conspiracy. Any minor errors in the response are heavily emphasized, while deficiencies in the arguments of other proponents are generally excused.[23]

In science, conspiracists may suggest that a scientific theory can be disproven by a single perceived deficiency, even though such events are extremely rare. In addition, both disregarding the claims and attempting to address them will be interpreted as proof of a conspiracy.[23] Other conspiracist arguments may not be scientific; for example, in response to the IPCC Second Assessment Report in 1996, much of the opposition centered on promoting a procedural objection to the report's creation. Specifically, it was claimed that part of the procedure reflected a conspiracy to silence dissenters, which served as motivation for opponents of the report and successfully redirected a significant amount of the public discussion away from the science.[23]

Consequences

Historically, conspiracy theories have been closely linked to prejudice, witch hunts, wars, and genocides.[22][23] They are often strongly believed by the perpetrators of terrorist attacks, and were used as justification by Timothy McVeigh, Anders Breivik and Brenton Tarrant, as well as by governments such as Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union.[22] AIDS denialism by the government of South Africa, motivated by conspiracy theories, caused an estimated 330,000 deaths from AIDS,[27][28][29] while belief in conspiracy theories about genetically modified foods led the government of Zambia to reject food aid during a famine,[23] at a time when 3 million people in the country were suffering from hunger.[33]

Conspiracy theories are a significant obstacle to improvements in public health.[23][34] People who believe in health-related conspiracy theories are less likely to follow medical advice, and more likely to use alternative medicine instead.[22] Conspiratorial anti-vaccination beliefs, such as conspiracy theories about pharmaceutical companies, can result in reduced vaccination rates and have been linked to outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases.[27][23][35][34] Health-related conspiracy theories often inspire resistance to water fluoridation, and contributed to the impact of the Lancet MMR autism fraud.[23][34]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conspiracy_theory