This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2007) |

The Baroque Revival, also known as Neo-Baroque (or Second Empire architecture in France and Wilhelminism in Germany), was an architectural style of the late 19th century.[1] The term is used to describe architecture and architectural sculptures which display important aspects of Baroque style, but are not of the original Baroque period. Elements of the Baroque architectural tradition were an essential part of the curriculum of the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, the pre-eminent school of architecture in the second half of the 19th century, and are integral to the Beaux-Arts architecture it engendered both in France and abroad. An ebullient sense of European imperialism encouraged an official architecture to reflect it in Britain and France, and in Germany and Italy the Baroque Revival expressed pride in the new power of the unified state.

Notable examples

- Akasaka Palace (1899–1909), Tokyo, Japan

- Alferaki Palace (1848), Taganrog, Russia

- Ashton Memorial (1907–1909), Lancaster, England

- Belfast City Hall (1898–1906), Belfast, Northern Ireland

- Beloselsky-Belozersky Palace (1747), Saint Petersburg, Russia

- Bode Museum (1904), Berlin, Germany

- British Columbia Parliament Buildings (1893–1897), Victoria, British Columbia, Canada

- Burgtheater (1888), Vienna, Austria

- Cardiff City Hall (1897-1906), Cardiff, Wales

- Christiansborg Palace (1907–1928), Copenhagen, Denmark

- Cluj-Napoca National Theatre (1904–1906), Cluj-Napoca, Romania

- Ortaköy Mosque (1854–6), Istanbul, Turkey

- Dolmabahçe Palace (1843–1856), Istanbul, Turkey

- The Elms Mansion (1899–1901), Newport, Rhode Island, United States

- Näsilinna (also known as the Milavida Palace) (1898), Tampere, Finland

- National Theatre (1899), Oslo, Norway

- Palais Garnier (also known as the Paris Opera) (1861–1875), Paris, France

- Port of Liverpool Building (1903–07) Liverpool, England

- Rosecliff Mansion (1898–1902), Newport, Rhode Island, United States

- Royal Museum for Central Africa (1905–1909), Tervuren, Belgium

- Semperoper (1878), Dresden, Germany

- Sofia University rectorate (1924–1934), Sofia, Bulgaria

- Zachęta National Gallery of Art (1898–1900), Warsaw, Poland

- St. Barbara's Church (1910), Brooklyn, New York, United States

- St. John Cantius Church (1893–1898), Chicago, United States

- Church of St. Ignatius Loyola (1895–1900), New York City, United States

- Church of Saints Peter and Paul (1932–39), Athlone, Ireland

- Cathedral of Salta (1882), Salta, Argentina

- Széchenyi thermal bath (1913), Budapest, Hungary

- Volkstheater (1889), Vienna, Austria

- National Art Gallery of Bulgaria (the former royal palace), Sofia, Bulgaria

- Wenckheim Palace (1886–1889), Budapest, Hungary

- Stefánia Palace (formerly named Park Club) (1893–1895), Budapest, Hungary

- Gran Teatro de La Habana (1908–1915), Havana, Cuba

- Old Parliament Building (1930), Colombo, Sri Lanka

- House of the National Assembly of Serbia (1907–1936), Belgrade, Serbia.

- Durban City Hall, South Africa

- Oceanographic Museum of Monaco, Principality of Monaco

There are also number of post-modern buildings with a style that might be called "Baroque", for example the Dancing House in Prague by Vlado Milunić and Frank Gehry, who have described it as "new Baroque".[2]

Baroque Revival architects

- Ferdinand Fellner (1847–1916) and Hermann Helmer (1849–1919)

- Arthur Meinig (1853–1904)

- Sir Edwin Lutyens (1869–1944)

- Members of the Armenian Balyan family (19th Century)

- Charles Garnier (1825–1898)

Gallery

Basilica of Saint Nicholas, Amsterdam (The Netherlans), 1887, by Adrianus Bleijs

Port of Liverpool (England), 1903–07, by Sir Arnold Thornely, F.B. Hobbs, Briggs and Wolstenholme

Apartment house in Berlin (Germany), 1889-1892, by Koebe & Weissmüller

Wenckheim Palace from Budapest (Hungary), 1886–1889, by Arthur Meinig

Sager House in Stockholm (Sweden), 1893, by Jean René Pierre Litoux

Building in Sibiu (Transylvania, Romania), 1892

Government Palace of Peru, in Lima, 1938, by Ricardo de Jaxa Malachowski

Window of a small family house in Bucharest, nearby Piața Romană

Wooden door with pediments of a 1896 house from Strasbourg (France). Even if it is Baroque Revival, it has many Neoclassical ornaments

Entrances of the Direction régionale des Impôts de Strasbourg, each of the doors having a mascaron

See also

- List of Baroque architecture

- List of Baroque residences

- Second Empire architecture

- Edwardian Baroque architecture

- Wilhelminism

References

- "The Dancing Building, which Frank Gehry and Vlado Milunic have described as "new Baroque", has divided opinion [...]", in "Architect recalls genesis of Dancing Building as coffee table book published", by Ian Willoughby, 11-07-2003, online at The international service of Czech Radio

Further reading

- James Stevens Curl; "Neo-Baroque." A Dictionary of Architecture and Landscape Architecture; Oxford University Press. 2000. — Encyclopedia.com . accessed 3 Jan. 2010.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baroque_Revival_architecture

This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2022) |

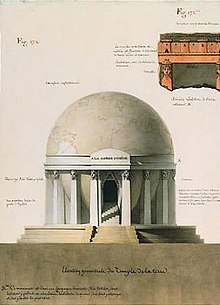

Architecture parlante (French: speaking architecture) is architecture that explains its own function or identity.

The phrase was originally associated with Claude Nicolas Ledoux, and was extended to other Paris-trained architects of the Revolutionary period, Étienne-Louis Boullée, and Jean-Jacques Lequeu.[1] Emil Kaufmann traced its first use to an anonymous critical essay with Ledoux's work as the subject, written for Magasin pittoresque in 1852, and entitled "Etudes d'architecture en France".[2]

Nonce orders

Within more practical applications, nonce orders, invented under the impetus of Neoclassicism, have served as examples of architecture parlante. Several orders, usually simply based upon the Composite order and only varying in the design of the capitals, have been invented under the inspiration of specific occasions, but have not been used again. Thus, they may be termed "nonce orders" on the analogy of nonce words.

In 1762, James Adam invented a British order featuring the heraldic lion and unicorn. In 1789, George Dance invented the Ammonite order, a variant of Ionic substituting volutes in the form of fossil ammonites for Boydell Shakespeare Gallery in Pall Mall, London. In the United States, Benjamin Latrobe, the architect of the Capitol Building in Washington DC, designed a series of American orders. Most famous is the order substituting corncobs and their husks, which was executed by Giuseppe Franzoni and installed in a vestibule of the Capitol Building.

Beaux-Arts

The same concept, in the somewhat more restrained form of allegorical sculpture and inscriptions, became one of the hallmarks of Beaux-Arts structures, and thereby filtered through to American civic architecture. One fine example is the 1901 New York Yacht Club building on 44th Street in Manhattan, designed by the team of Warren and Wetmore. Its three front windows are patterned on the sterns of early Dutch ships, and the façade fairly drips with nautical-themed applied sculpture. The same team designed the 1912 Grand Central Terminal, which also contains self-explaining architectural elements in the form of the oversized allegorical sculpture group, and in the ingenious way that the shapes, surfaces, steps, arches, ramps and passageways inherent in the structure constitute a language that helps visitors orient themselves and find their way through the building.

The same year, McKim, Mead & White designed the Farley Post Office Building with its famous inscription adapted from Herodotus: "Neither snow nor rain nor heat nor gloom of night stays these couriers from the swift completion of their appointed rounds."

The civic architecture of Washington, D.C. provides some of the most poetic and most verbose inscriptions. Beaux-Arts architect Daniel Burnham is responsible for the Washington Union Station (1908), with its inscription program developed by Harvard president Charles William Eliot. It includes over the main entrance this paean: "Fire: greatest of discoveries, enabling man to live in various climates, use many foods, and compel the forces of nature to do his work. Electricity: carrier of light and power, devourer of time and space, bearer of human speech over land and sea, greatest servant of man, itself unknown. Thou hast put all things under his feet."

Neo-Classical

The 1932 Commerce Department Building, part of the capital's neo-Classical building boom in the 1930s, has this example: "The inspiration that guided our forefathers led them to secure above all things the unity of our country. We rest upon government by consent of the governed and the political order of the United States as the expression of a patriotic ideal which welds together all the elements of our national energy promoting the organization that fosters individual initiative. Within this edifice are established agencies that have been created to buttress the life of the people, to clarify their problems and coordinate their resources, seeking to lighten burdens without lessening the responsibility of the citizen. In serving one and all they are dedicated to the purpose of the founders and to the highest hopes of the future with their local administration given to the integrity and welfare of the nation."[citation needed]

Beyond such inscriptions, in the United States the concept of architecture parlante likely reached its zenith in the Nebraska State Capitol (1922) and the Los Angeles Public Library (1925), both by architect Bertram Goodhue and both containing inscriptions by iconographer Hartley Burr Alexander.[3] With their extensive architectural sculpture programs, tile murals, painted murals, ornamental fixtures and inscriptions (Goodhue worked with a sort of multimedia repertory company of artists, such as the sculptor Lee Lawrie), both of these buildings seem particularly eager[citation needed] to communicate a set of social values.[which?]

Contemporary era

With the advent of Modernism, its formal rigor and its distaste for ornament of any kind, by 1940 or so architectural parlante was eliminated from the serious architectural vocabulary and found only in vernacular novelty architecture such as The Brown Derby.

Postmodern architecture has seen a revival of these ideas. Terry Farrell's eggcup-surmounted headquarters for TV-am in London and the book-shaped towers of the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris, can be seen as examples. Michael Graves's unbuilt project, Fargo-Moorhead Cultural Center, also is a revivalistic example of Ledoux's Inspector's House of Chaux.

In the terminology of Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown, "any building that is shaped like its product is called a 'duck',"[4] in reference to the Big Duck.

Notes

- Newsday (Feb. 21, 2007): "It Happened on Long Island" (column): "1988: Suffolk County Adopts the Big Duck", by Cynthia Blair

No comments:

Post a Comment