A cave dweller, or troglodyte, is a human who inhabits a cave or the area beneath the overhanging rocks of a cliff.

Prehistory

Some prehistoric humans were cave dwellers, but most were not (see Homo and Human evolution). Such early cave dwellers, and other prehistoric peoples, are also called cave men (the term also refers to the stereotypical "caveman" stock character type from fiction and popular culture). Despite the name, only a small portion of humanity has ever dwelt in caves: caves are rare across most of the world; most caves are dark, cold, and damp; and other cave inhabitants, such as bears and cave bears, cave lions, and cave hyenas, often made caves inhospitable for people.

The Grotte du Vallonnet, a cave in the French Riviera, was used by people approximately one million years ago. Although stone tools and the remains of eaten animals have been found in the cave, there is no indication that people dwelt in it.

Since about 750,000 years ago, the Zhoukoudian cave system, in Beijing, China, has been inhabited by various species of human being, including Peking Man (Homo erectus pekinensis) and modern humans (Homo sapiens).

Starting about 170,000 years ago, some Homo sapiens lived in some cave systems in what is now South Africa, such as Pinnacle Point and Diepkloof Rock Shelter. The stable temperatures of caves provided a cool habitat in summers and a warm, dry shelter in the winter. Remains of grass bedding have been found in nearby Border Cave.[1]

About 100,000 years ago, some Neanderthals dwelt in caves in Europe and western Asia. Caves there also were inhabited by some Cro-Magnons, from about 35,000 years ago until about 8000 B.C. Both species built shelters, including tents, at the mouths of caves and used the caves’ dark interiors for ceremonies. The Cro-Magnon people also made representational paintings on cave walls.[2]

Also about 100,000 years ago, some Homo sapiens worked in Blombos Cave, in what became South Africa. They made the earliest paint workshop now known, but apparently did not dwell in the caves.[3]

Writers of the classical Greek and Roman period made several allusions to cave-dwelling tribes in different parts of the world. For details, see "Troglodytae".[4]

Historical

Especially during war and other times of strife, small groups of people have lived temporarily in caves, where they have hidden or otherwise sought refuge. They also have used caves for clandestine and other special purposes while living elsewhere.

Perhaps fleeing the violence of Ancient Romans, people left the Dead Sea Scrolls in eleven caves near Qumran, in what is now an area of the West Bank managed by Qumran National Park, in Israel. The documents remained undisturbed there for about 2,000 years, until their discovery in the 1940s and 1950s.

The DeSoto Caverns, in what became Alabama in the United States, were a burial ground for local tribes; the same caves became a violent speakeasy in the 1920s. The Caves of St. Louis may have been a hiding-place along the Underground Railroad.

From about 1000 to about 1300, some Pueblo people lived in villages that they built beneath cliffs in what is now the Southwestern United States.

In Hirbet Tawani, near Yatta Village, in the Southern Hebron Hills, in an area contested by the Palestinian Authority and Israel, there are Palestinians living in caves. People also inhabited caves there during the time of the Ottoman Empire and of the British Mandate for Palestine. In recent years some have been evicted by the Israeli government and settlers.[5]

In her book Home Life in Colonial Days, Alice Morse Earle wrote of some of the first European settlers in New England, New York, and Pennsylvania living in cave dwellings, also known as "smoaky homes":

In Pennsylvania caves were used by newcomers as homes for a long time, certainly half a century. They generally were formed by digging into the ground about four feet in depth on the banks or low cliffs near the river front. The walls were then built up of sods or earth laid on poles or brush; thus half only of the chamber was really under ground. If dug into a side hill, the earth formed at least two walls. The roofs were layers of tree limbs covered over with sod, or bark, or rushes and bark. The chimneys were laid of cobblestone or sticks of wood mortared with clay and grass. The settlers were thankful even for these poor shelters, and declared that they found them comfortable. By 1685 many families were still living in caves in Pennsylvania, for the Governor's Council then ordered the caves to be destroyed and filled in.[6]

In the 1970s, several members of the Tasaday apparently inhabited caves near Cotabato, in the Philippines.

Caves at Sacromonte, near Granada, Spain, are home to about 3,000 Gitano people, whose dwellings range from single rooms to caves of nearly 200 rooms, along with churches, schools, and stores in the caves.

Some families have built modern homes in caves, and renovated old ones, as in Missouri;[7] Matera, Italy;[8][9] and Spain.[10]

At least 30,000,000 people in China live in cave homes, called yaodongs; because they are warm in the winter and cool in the summer, some people find caves more desirable than concrete homes in the city.[11]

In the Australian desert mining towns of Coober Pedy and Lightning Ridge, many families have carved homes into the underground opal mines, to escape the heat.

In the Loire Valley, abandoned caves are being privately renovated as affordable housing.[12]

In England, the rock houses at Kinver Edge were inhabited until the middle of the 20th century.[13]

In Greece, some Christian hermits and saints are known by the epithet "cave dweller" (Greek: Σπηλαιώτης, romanized: Spileótis) since they lived in cave dwellings; examples include Joseph the Cave Dweller (also known as Joseph the Hesychast) and Arsenios the Cave Dweller.[14]

In 2021-2023 Beatriz Flamini spent 500 days alone in a cave in Spain in an experiment on the effects of social isolation.[15][16]

See also

References

- Rodriguez, Elena (14 April 2023). "Spanish athlete emerges into daylight after 500 days in cave". Reuters.

External links

- Ernest Ingersoll (1920). . Encyclopedia Americana.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cave_dweller

A lava tube, or pyroduct,[1] is a natural conduit formed by flowing lava from a volcanic vent that moves beneath the hardened surface of a lava flow. If lava in the tube empties, it will leave a cave.

Formation

A lava tube is a type of lava cave formed when a low-viscosity lava flow develops a continuous and hard crust, which thickens and forms a roof above the still-flowing lava stream. Tubes form in one of two ways: either by the crusting over of lava channels, or from pāhoehoe flows where the lava is moving under the surface.[2]

Lava usually leaves the point of eruption in channels. These channels tend to stay very hot as their surroundings cool. This means they slowly develop walls around them as the surrounding lava cools and/or as the channel melts its way deeper. These channels can get deep enough to crust over, forming an insulating tube that keeps the lava molten and serves as a conduit for the flowing lava. These types of lava tubes tend to be closer to the lava eruption point.

Farther away from the eruption point, lava can flow in an unchanneled, fan-like manner as it leaves its source, which is usually another lava tube leading back to the eruption point. Called pāhoehoe flows, these areas of surface-moving lava cool, forming either a smooth or rough, ropy surface. The lava continues to flow this way until it begins to block its source. At this point, the subsurface lava is still hot enough to break out at a point, and from this point the lava begins as a new "source". Lava flows from the previous source to this breakout point as the surrounding lava of the pāhoehoe flow cools. This forms an underground channel that becomes a lava tube.[3]

Characteristics

A broad lava-flow field often consists of a main lava tube and a series of smaller tubes that supply lava to the front of one or more separate flows. When the supply of lava stops at the end of an eruption or lava is diverted elsewhere, lava in the tube system drains downslope and leaves partially empty caves.

Such drained tubes commonly exhibit step marks on their walls that mark the various depths at which the lava flowed, known as flow ledges or flow lines depending on how prominently they protrude from the walls. Lava tubes generally have pāhoehoe floors, although this may often be covered in breakdown from the ceiling. A variety of speleothems may be found in lava tubes[4] including a variety of stalactite forms generally known as lavacicles, which can be of the splash, "shark tooth", or tubular varieties. Lavacicles are the most common of lava tube speleothems. Drip stalagmites may form under tubular lava stalactites, and the latter may grade into a form known as a tubular lava helictite. A runner is a bead of lava that is extruded from a small opening and then runs down a wall. Lava tubes may also contain mineral deposits that most commonly take the form of crusts or small crystals, and less commonly, as stalactites and stalagmites. Some stalagmites may contain a central conduit and are interpreted as hornitos extruded from the tube floor.[5]

Lava tubes can be up to 14–15 metres (46–49 ft) wide, though are often narrower, and run anywhere from 1–15 metres (3 ft 3 in – 49 ft 3 in) below the surface. Lava tubes can also be extremely long; one tube from the Mauna Loa 1859 flow enters the ocean about 50 kilometers (31 mi) from its eruption point, and the Cueva del Viento–Sobrado system on Teide, Tenerife island, is over 18 kilometers (11 mi) long, due to extensive braided maze areas at the upper zones of the system.

A lava tube system in Kiama, Australia, consists of over 20 tubes, many of which are breakouts of a main lava tube. The largest of these lava tubes is 2 meters (6.6 ft) in diameter and has columnar jointing due to the large cooling surface. Other tubes have concentric and radial jointing features. The tubes are infilled due to the low slope angle of emplacement.

Extraterrestrial lava tubes

Lunar lava tubes have been discovered[6] and have been studied as possible human habitats, providing natural shielding from radiation.[7]

Martian lava tubes are associated with innumerable lava flows and lava channels on the flanks of Olympus Mons. Partially collapsed lava tubes are visible as chains of pit craters, and broad lava fans formed by lava emerging from intact, subsurface tubes are also common.[8]

Caves, including lava tubes, are considered candidate biotopes of interest for extraterrestrial life.[9]

Notable examples

- Iceland

- Raufarhólshellir

- Surtshellir – For a long time, this was the longest known lava tube in the world.[10]

- Kenya

- Leviathan Cave – At 12.5 kilometres, it is the longest lava tube in Africa.[11]

- Portugal

- Gruta das Torres – Lava tube system of the Azores.

- South Korea

- Manjang Cave – more than 8 kilometers long, located in Jeju Island, is a popular tourism spot.[12]

- Spain

- Cueva de los Verdes – Lava tube system. Lanzarote, Canary Islands.

- United States

- Kazumura Cave, Hawaii – Not only the world's most extensive lava tube, but at 65.5 kilometres (40.7 mi), it has the greatest linear extent of any cave known.[13]

- Lava River Cave in Oregon's Newberry National Volcanic Monument.[14]

See also

- Caving – Recreational pastime of exploring cave systems

- Geology of the Moon – Structure and composition of the Moon

- Lava cave – Cave formed in volcanic rock, especially one formed via volcanic processes

- Mars habitat – Facility where humans could live on Mars

- Speleology – Science of cave and karst systems

- Speleothem – Structure formed in a cave by the deposition of minerals from water

Notes

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lava_tube

A storm shelter or storm cellar is a type of underground bunker designed to protect the occupants from violent severe weather, particularly tornadoes. They are most frequently seen in the Midwest ("Tornado Alley") and Southeastern United States ("Dixie Alley") where tornadoes are generally frequent and the low water table permits underground structures.

Average storm shelter

An average storm cellar for a single family is built close enough to the home to allow instant access in an emergency, but not so close that the house could tumble on the door during a storm, trapping the occupants inside. This is also the reason the main door on most storm cellars is mounted at an angle rather than perpendicular with the ground. An angled door allows for debris to blow up and over the door, or sand to slide off, without blocking it, and the angle also reduces the force necessary to open the door if rubble has piled up on top. Floor area is generally around eight by twelve feet (2.5 × 3.5 m), with an arched roof like that of a Quonset hut, but entirely underground. In most cases the entire structure is built of blocks faced with cement and rebar through the bricks for protection from the storm. Doing so makes it nearly impossible for the bricks to collapse. New ones are sometimes made of septic tanks that have been modified with a steel door and vents. Some new shelters are rotationally molded from polyethylene.[1]

Most storm cellars are accessible by a covered stairwell, and at the opposite end of the structure there can be conduits for air that reach the surface, and perhaps a small window to serve as an emergency exit and also to provide some light. Storm cellars, when connected to the house, may potentially compromise security.[2]

Fully enclosed underground storm shelters offer superior tornado protection to that of a traditional basement (cellar) because they provide separate overhead cover without the risk of occupants being trapped or killed by collapsing rubble from above. For this reason they also provide the only reliable form of shelter against "violent" (EF4 and EF5) tornadoes which tend to rip the house from its foundation, removing the overhead cover which was protecting the occupant.[citation needed]

There are several different styles of storm cellars. There are the generic underground storm/tornado cellar, also called storm or tornado shelters, as well as the new above-ground safe rooms. A "cellar" is an underground unit, but for the sake of the specified use of a "storm cellar" to protect one from high-wind storms, it seems relevant to mention saferooms. There are two basic styles of underground storm cellars. One is the "hillside" or "embankment" and the other is the "flat" ground.

One other style of shelter is the under garage.[3] While similar to other underground shelters, its main difference is that it is installed in a garage rather than outside. Having it installed in the garage allows access to it without having to go outside during a storm. It is sometimes not an option to have a shelter installed outside either due to insufficient space, or local ordinances.

Hillside/embankment shelters

Hillside or embankment models are usually installed in one of two ways. It can be installed in an existing hill/embankment or dirt is built up around a freestanding unit, forming a hill around it. The door can be set at an angle or vertically. There can be steps leading into the unit, or it can be installed to where the floor is level with the ground outside. The embankment storm cellar can be made from concrete, steel, fiberglass, or any other structurally sound material or composite and is usually installed in a hill or embankment, leaving only the door exposed. In some situations, they can hold an entire neighborhood or town as with a community shelter. More often, they are built to hold one or two families, specified as a residential shelter. All underground "storm or tornado" shelters must be properly anchored.

Above ground shelters

Above ground shelters are used in many areas of the country and by a wide variety of homeowners and businesses. Groundwater tables may make it impossible to install or build a shelter below ground, elderly or people with limited mobility may be unable to access a below ground shelter, or people may have significant phobias pertaining to below ground sheltering. FEMA P-320, Taking Shelter from the Storm: Building a Safe Room for Your Home or Small Business (2014)[4] and ICC/NSSA Standard for the Design and Construction of Storm Shelters[5] provide engineering and testing requirements to ensure that above ground shelters manufactured to the published specifications will withstand winds in excess of 250 mph (400 km/h) (EF5 tornado). Above ground shelters may be built of different materials such as steel reinforced concrete[6] or 1/8" 10 ga. hot rolled steel and may be installed inside a home, garage, or outbuilding, or as a stand-alone unit. These types of shelters are typically prefabricated and installed on a home site or commercial location. Walls can be provided which form a deflector baffle entry so that the path of the storm debris must touch two impact resistant surfaces before it penetrates into the protected area of the occupants.[7][8]

Wind engineering specialists from Texas Tech University's National Wind Institute have done extensive research that concludes that sheltering in an above ground storm shelter that meets the engineering criteria outlined in FEMA Pub. 320 and 361 and ICC/NSSA Standard for the Design and Construction of Storm Shelters is as safe as seeking below ground shelter during massive EF4 and EF5 tornadoes. TTU engineer Joseph Dannemiller presented the research findings at a TEDxTexasTechUniversity symposium in February 2014.[9]

Below-ground shelters

The below-ground shelters are designed so that the door is flat with the ground and can be made from any one of the materials previously described. This unit is put in a hole deep enough to cover the bottom section, and then the excavated dirt is filled in around the top and packed down. Storm shelters must be designed, built, tested, and installed properly for them to meet any of the US FEMA-320,[4] FEMA-361,[10] ICC-500,[11] NPCTS (National Performance Criteria for Tornado Shelters), or ICC/NSSA Standards.

Geolocation services

Many storm shelter manufacturers include geolocation services or incorporate GPS technologies to assist in ensuring recovery from the shelter after a storm or other catastrophic event. In addition, shelter owners may opt to incorporate their own geolocation services in their shelter. Shelter owners can provide their shelter's GPS coordinates to an emergency response center that is linked to a nationwide severe weather notification system. If a storm occurs, the emergency response center places a phone call to the shelter owner and then secondary contacts, lastly contacting local emergency response if unable to contact the shelter owner.[12]

Additional uses

Since it is functionally just an underground bunker, storm cellars can also be used as improvised bomb shelters or fallout shelters (although they are not usually dug as deeply or equipped with filtered ventilation). Since the underground construction makes them cool and dark, storm cellars on farmsteads in the Midwest are traditionally used as root cellars to store seasonal canned goods for consumption during the winter.

See also

References

- Malagarie, Danielle (August 12, 2017). "Family shares why it's important to register storm shelters". newschannel6now.com. Wichita Falls, Texas: KAUZ. Retrieved 1 April 2019.

Further reading

- Skousen, Joel M. (1999). The Secure Home (3rd ed.). American Fork, Utah: Swift Learning Resources. ISBN 978-1-56861-055-9. OCLC 42930398.

- "National Storm Shelter Association (NSSA)". Retrieved 28 March 2013.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Storm_cellar

Trench warfare is the type of land warfare using occupied lines largely comprising military trenches, in which troops are well-protected from the enemy's small arms fire and are substantially sheltered from artillery. It became archetypically associated with World War I (1914–1918), when the Race to the Sea rapidly expanded trench use on the Western Front starting in September 1914.[1]

Trench warfare proliferated when a revolution in firepower was not matched by similar advances in mobility,[clarification needed] resulting in a grueling form of warfare in which the defender held the advantage.[2] On the Western Front in 1914–1918, both sides constructed elaborate trench, underground, and dugout systems opposing each other along a front, protected from assault by barbed wire. The area between opposing trench lines (known as "no man's land") was fully exposed to artillery fire from both sides. Attacks, even if successful, often sustained severe casualties.

The development of armoured warfare and combined arms tactics permitted static lines to be bypassed and defeated, leading to the decline of trench warfare after the war. Following World War I, "trench warfare" became a byword for stalemate, attrition, sieges, and futility in conflict.[3]

Precursors

Field works have existed for as long as there have been armies. Roman legions, when in the presence of an enemy, entrenched camps nightly when on the move.[4] The Roman general Belisarius had his soldiere dig a trench as part of the Battle of Dara in 530 CE.

Trench warfare was also documented during the defence of Medina in a siege known as the Battle of the Trench (627 AD). The architect of the plan was Salman the Persian who suggested digging a trench to defend Medina.

There are examples of trench digging as a defensive measure during the Middle Ages in Europe, such as during the Piedmontese Civil War, where it was documented that on the morning of May 12, 1640, the French soldiers, having already captured the left bank of the Po river and gaining control of the bridge connecting the two banks of the river, and wanting to advance to the Capuchin Monastery of the Monte, deciding that their position wasn't secure enough for their liking, then choose to advance on a double attack on the trenches, but were twice repelled. Eventually, on the third attempt, the French broke through and the defenders were forced to flee with the civilian population, seeking the sanctuary of the local Catholic church, the Santa Maria al Monte dei Cappuccini, in Turin, also known at that time as the Capuchin Monastery of the Monte. An interesting read is about the Eucharistic Miracle of Turin, Italy, on May 12, 1640.[5]

In early modern warfare troops used field works to block possible lines of advance.[6] Examples include the Lines of Stollhofen, built at the start of the War of the Spanish Succession of 1702–1714,[7] the Lines of Weissenburg built under the orders of the Duke of Villars in 1706,[8] the Lines of Ne Plus Ultra during the winter of 1710–1711,[6] and the Lines of Torres Vedras in 1809 and 1810.[4]

In the New Zealand Wars (1845–1872), the Māori developed elaborate trench and bunker systems as part of fortified areas known as pa, employing them successfully as early as the 1840s to withstand British artillery bombardments.[9][10] According to one British observer, "the fence round the pa is covered between every paling with loose bunches of flax, against which the bullets fall and drop; in the night they repair every hole made by the guns".[11] These systems included firing trenches, communication trenches, tunnels, and anti-artillery bunkers. Ruapekapeka is often considered to be the most sophisticated and technologically impressive by historians.[12] British casualty rates of up to 45 percent, such as at Gate Pa in 1864 and the Battle of Ohaeawai in 1845, suggested that contemporary weaponry, such as muskets and cannon, proved insufficient to dislodge defenders from a trench system.[13] There has been an academic debate surrounding this since the 1980s, when in his book The New Zealand Wars, historian James Belich claimed that Northern Māori had effectively invented trench warfare during the first stages of the New Zealand Wars. However, this has been criticised by a few academics of the same period, with Gavin McLean noting that while the Māori had certainly adapted pa to suit contemporary weaponry, many historians have dismissed Belich's claim as "baseless... revisionism".[14] Others more recently have said that while it is difficult to assert for certain whether Māori invented trench warfare first - Maori did invent trench-based defences without any offshore aid - many believed they played a significant role in the 20th-century methods most commonly identified with it.[15][16]

The Crimean War (1853–1856) saw "massive trench works and trench warfare",[17] even though "the modernity of the trench war was not immediately apparent to the contemporaries".[18]

Union and Confederate armies employed field works and extensive trench systems in the American Civil War (1861–1865) — most notably in the sieges of Vicksburg (1863) and Petersburg (1864–1865), the latter of which saw the first use by the Union Army of the rapid-fire Gatling gun,[19] the important precursor to modern-day machine guns. Trenches were also utilized in the Paraguayan War (which started in 1864), the Second Anglo-Boer War (1899–1902), and the Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905).

Adoption

Although technology had dramatically changed the nature of warfare by 1914, the armies of the major combatants had not fully absorbed the implications. Fundamentally, as the range and rate of fire of rifled small-arms increased, a defender shielded from enemy fire (in a trench, at a house window, behind a large rock, or behind other cover) was often able to kill several approaching foes before they closed around the defender's position. Attacks across open ground became even more dangerous after the introduction of rapid-firing artillery, exemplified by the "French 75", and high explosive fragmentation rounds. The increases in firepower had outstripped the ability of infantry (or even cavalry) to cover the ground between firing lines, and the ability of armour to withstand fire. It would take a revolution in mobility to change that.[20]

The French and German armies adopted different tactical doctrines: the French relied on the attack with speed and surprise, and the Germans relied on firepower, investing heavily in howitzers and machine guns. The British lacked an official tactical doctrine, with an officer corps that rejected theory in favour of pragmatism.[21]

While the armies expected to use entrenchments and cover, they did not allow for the effect of defences in depth. They required a deliberate approach to seizing positions from which fire support could be given for the next phase of the attack, rather than a rapid move to break the enemy's line.[22] It was assumed that artillery could still destroy entrenched troops, or at least suppress them sufficiently for friendly infantry and cavalry to manoeuvre.[23]

Digging-in when defending a position was a standard practice by the start of WWI. To attack frontally was to court crippling losses, so an outflanking operation was the preferred method of attack against an entrenched enemy. After the Battle of the Aisne in September 1914, an extended series of attempted flanking moves, and matching extensions to the fortified defensive lines, developed into the "race to the sea", by the end of which German and Allied armies had produced a matched pair of trench lines from the Swiss border in the south to the North Sea coast of Belgium.

By the end of October 1914, the whole front in Belgium and France had solidified into lines of trenches, which lasted until the last weeks of the war. Mass infantry assaults were futile in the face of artillery fire, as well as rapid rifle and machine-gun fire. Both sides concentrated on breaking up enemy attacks and on protecting their own troops by digging deep into the ground.[24] After the buildup of forces in 1915, the Western Front became a stalemated struggle between equals, to be decided by attrition. Frontal assaults, and their associated casualties, became inevitable because the continuous trench lines had no open flanks. Casualties of the defenders matched those of the attackers, as vast reserves were expended in costly counter-attacks or exposed to the attacker's massed artillery. There were periods in which rigid trench warfare broke down, such as during the Battle of the Somme, but the lines never moved very far. The war would be won by the side that was able to commit the last reserves to the Western Front. Trench warfare prevailed on the Western Front until the Germans launched their Spring Offensive on 21 March 1918.[25] Trench warfare also took place on other fronts, including in Italy and at Gallipoli.

Armies were also limited by logistics. The heavy use of artillery meant that ammunition expenditure was far higher in WWI than in any previous conflict. Horses and carts were insufficient for transporting large quantities over long distances, so armies had trouble moving far from railheads. This greatly slowed advances, making it impossible for either side to achieve a breakthrough that would change the war. This situation would only be altered in WWII with greater use of motorized vehicles.[26][27]

Construction

Trenches were longer, deeper, and better defended by steel, concrete, and barbed wire than ever before. They were far stronger and more effective than chains of forts, for they formed a continuous network, sometimes with four or five parallel lines linked by interfacings. They were dug far below the surface of the earth out of reach of the heaviest artillery....Grand battles with the old maneuvers were out of the question. Only by bombardment, sapping, and assault could the enemy be shaken, and such operations had to be conducted on an immense scale to produce appreciable results. Indeed, it is questionable whether the German lines in France could ever have been broken if the Germans had not wasted their resources in unsuccessful assaults, and the blockade by sea had not gradually cut off their supplies. In such warfare no single general could strike a blow that would make him immortal; the "glory of fighting" sank down into the dirt and mire of trenches and dugouts.

— James Harvey Robinson and Charles A. Beard, The Development Of Modern Europe Volume II The Merging Of European Into World History[28]

Early World War I trenches were simple. They lacked traverses, and according to pre-war doctrine were to be packed with men fighting shoulder to shoulder. This doctrine led to heavy casualties from artillery fire. This vulnerability, and the length of the front to be defended, soon led to frontline trenches being held by fewer men. The defenders augmented the trenches themselves with barbed wire strung in front to impede movement; wiring parties went out every night to repair and improve these forward defences.[29]

The small, improvised trenches of the first few months grew deeper and more complex, gradually becoming vast areas of interlocking defensive works. They resisted both artillery bombardment and mass infantry assault. Shell-proof dugouts became a high priority.[30]

A well-developed trench had to be at least 2.5 m (8 ft) deep to allow men to walk upright and still be protected.

There were three standard ways to dig a trench: entrenching, sapping, and tunnelling. Entrenching, where a man would stand on the surface and dig downwards, was most efficient, as it allowed a large digging party to dig the full length of the trench simultaneously. However, entrenching left the diggers exposed above ground and hence could only be carried out when free of observation, such as in a rear area or at night. Sapping involved extending the trench by digging away at the end face. The diggers were not exposed, but only one or two men could work on the trench at a time. Tunnelling was like sapping except that a "roof" of soil was left in place while the trench line was established and then removed when the trench was ready to be occupied. The guidelines for British trench construction stated that it would take 450 men 6 hours at night to complete 250 m (270 yd) of front-line trench system. Thereafter, the trench would require constant maintenance to prevent deterioration caused by weather or shelling.

Trenchmen were a specialized unit of trench excavators and repairmen. They usually dug or repaired in groups of four with an escort of two armed soldiers. Trenchmen were armed with one 1911 semi-automatic pistol, and were only utilized when either a new trench needed to be dug or expanded quickly, or when a trench was destroyed by artillery fire. Trenchmen were trained to dig with incredible speed; in a dig of three to six hours they could accomplish what would take a normal group of frontline infantry soldiers around two days. Trenchmen were usually looked down upon by fellow soldiers because they did not fight. They were usually called cowards because if they were attacked while digging, they would abandon the post and flee to safety. They were instructed to do this though because through the war there were only around 1,100 trained trenchmen. They were highly valued only by officers higher on the chain of command.

Components

The banked earth on the lip of the trench facing the enemy was called the parapet and had a fire step. The embanked rear lip of the trench was called the parados, which protected the soldier's back from shells falling behind the trench. The sides of the trench were often revetted with sandbags, wire mesh, wooden frames and sometimes roofs. The floor of the trench was usually covered by wooden duckboards. In later designs the floor might be raised on a wooden frame to provide a drainage channel underneath. Due to the substantial casualties taken from indirect fire, some trenches were reinforced with corrugated metal roofs over the top as an improvised defence from shrapnel.[31]

The static movement of trench warfare and a need for protection from snipers created a requirement for loopholes both for discharging firearms and for observation.[32] Often a steel plate was used with a "key hole", which had a rotating piece to cover the loophole when not in use.[32] German snipers used armour-piercing bullets that allowed them to penetrate loopholes. Another means to see over the parapet was the trench periscope – in its simplest form, just a stick with two angled pieces of mirror at the top and bottom. A number of armies made use of the periscope rifle, which enabled soldiers to snipe at the enemy without exposing themselves over the parapet, although at the cost of reduced shooting accuracy. The device is most associated with Australian and New Zealand troops at Gallipoli, where the Turks held the high ground.

Dugouts of varying degrees of comfort were built in the rear of the support trench. British dugouts were usually 2.5 to 5 m (8 to 16 ft) deep. The Germans, who had based their knowledge on studies of the Russo-Japanese War,[33] made something of a science out of designing and constructing defensive works. They used reinforced concrete to construct deep, shell-proof, ventilated dugouts, as well as strategic strongpoints. German dugouts were typically much deeper, usually a minimum of 4 m (12 ft) deep and sometimes dug three stories down, with concrete staircases to reach the upper levels.

Layout

Trenches were never straight but were dug in a zigzagging or stepped pattern, with all straight sections generally kept less than a dozen metres. Later, this evolved to have the combat trenches broken into distinct fire bays connected by traverses. While this isolated the view of friendly soldiers along their own trench, this ensured the entire trench could not be enfiladed if the enemy gained access at any one point; or if a bomb, grenade, or shell landed in the trench, the blast could not travel far.

Very early in the war, British defensive doctrine suggested a main trench system of three parallel lines, interconnected by communications trenches. The point at which a communications trench intersected the front trench was of critical importance, and it was usually heavily fortified. The front trench was lightly garrisoned and typically occupied in force only during "stand to" at dawn and dusk. Between 65 and 90 m (70 and 100 yd) behind the front trench was located the support (or "travel") trench, to which the garrison would retreat when the front trench was bombarded.

Between 90 and 270 metres (100 and 300 yd) further to the rear was located the third reserve trench, where the reserve troops could amass for a counter-attack if the front trenches were captured. This defensive layout was soon rendered obsolete as the power of artillery grew; however, in certain sectors of the front, the support trench was maintained as a decoy to attract the enemy bombardment away from the front and reserve lines. Fires were lit in the support line to make it appear inhabited and any damage done immediately repaired.

Temporary trenches were also built. When a major attack was planned, assembly trenches would be dug near the front trench. These were used to provide a sheltered place for the waves of attacking troops who would follow the first waves leaving from the front trench. "Saps" were temporary, unmanned, often dead-end utility trenches dug out into no-man's land. They fulfilled a variety of purposes, such as connecting the front trench to a listening post close to the enemy wire or providing an advance "jumping-off" line for a surprise attack. When one side's front line bulged towards the opposition, a salient was formed. The concave trench line facing the salient was called a "re-entrant." Large salients were perilous for their occupants because they could be assailed from three sides.

Behind the front system of trenches there were usually at least two more partially prepared trench systems, kilometres to the rear, ready to be occupied in the event of a retreat. The Germans often prepared multiple redundant trench systems; in 1916 their Somme front featured two complete trench systems, one kilometre apart, with a third partially completed system a further kilometre behind. This duplication made a decisive breakthrough virtually impossible. In the event that a section of the first trench system was captured, a "switch" trench would be dug to connect the second trench system to the still-held section of the first.

Wire

The use of lines of barbed wire, razor wire, and other wire obstacles, in belts 15 m (49 ft) deep or more, is effective in stalling infantry travelling across the battlefield. Although the barbs or razors might cause minor injuries, the purpose was to entangle the limbs of enemy soldiers, forcing them to stop and methodically pull or work the wire off, likely taking several seconds, or even longer. This is deadly when the wire is emplaced at points of maximum exposure to concentrated enemy firepower, in plain sight of enemy fire bays and machine guns. The combination of wire and firepower was the cause of most failed attacks in trench warfare and their very high casualties. Liddell Hart identified barbed wire and the machine gun as the elements that had to be broken to regain a mobile battlefield.

A basic wire line could be created by draping several strands of barbed wire between wooden posts driven into the ground. Loose lines of wire can be more effective in entangling than tight ones, and it was common to use the coils of barbed wire as delivered only partially stretched out, called concertina wire. Placing and repairing wire in no man's land relied on stealth, usually done at night by special wiring parties, who could also be tasked with secretly sabotaging enemy wires. The screw picket, invented by the Germans and later adopted by the Allies during the war, was quieter than driving stakes. Wire often stretched the entire length of a battlefield's trench line, in multiple lines, sometimes covering a depth 30 metres (100 ft) or more.

Methods to defeat it were rudimentary. Prolonged artillery bombardment could damage them, but not reliably. The first soldier meeting the wire could jump onto the top of it, hopefully depressing it enough for those that followed to get over him; this still took at least one soldier out of action for each line of wire. In World War I, British and Commonwealth forces relied on wire cutters, which proved unable to cope with the heavier gauge German wire.[34] The Bangalore torpedo was adopted by many armies, and continued in use past the end of World War II.[35]

The barbed wire used differed between nations; the German wire was heavier gauge, and British wire cutters, designed for the thinner native product, were unable to cut it.[34]

Geography

The confined, static, and subterranean nature of trench warfare resulted in it developing its own peculiar form of geography. In the forward zone, the conventional transport infrastructure of roads and rail were replaced by the network of trenches and trench railways. The critical advantage that could be gained by holding the high ground meant that minor hills and ridges gained enormous significance. Many slight hills and valleys were so subtle as to have been nameless until the front line encroached upon them. Some hills were named for their height in metres, such as Hill 60. A farmhouse, windmill, quarry, or copse of trees would become the focus of a determined struggle simply because it was the largest identifiable feature. However, it would not take the artillery long to obliterate it, so that thereafter it became just a name on a map.

The battlefield of Flanders presented numerous problems for the practice of trench warfare, especially for the Allied forces, mainly British and Canadians, who were often compelled to occupy the low ground. Heavy shelling quickly destroyed the network of ditches and water channels which had previously drained this low-lying area of Belgium. In most places, the water table was only a metre or so below the surface, meaning that any trench dug in the ground would quickly flood. Consequently, many "trenches" in Flanders were actually above ground and constructed from massive breastworks of sandbags filled with clay. Initially, both the parapet and parados of the trench were built in this way, but a later technique was to dispense with the parados for much of the trench line, thus exposing the rear of the trench to fire from the reserve line in case the front was breached.

In the Alps, trench warfare even stretched onto vertical slopes and deep into the mountains, to heights of 3,900 m (12,800 ft) above sea level. The Ortler had an artillery position on its summit near the front line. The trench-line management and trench profiles had to be adapted to the rough terrain, hard rock, and harsh weather conditions. Many trench systems were constructed within glaciers such as the Adamello-Presanella group or the famous city below the ice on the Marmolada in the Dolomites.

Observation

Observing the enemy in trench warfare was difficult, prompting the invention of technology such as the camouflage tree.[36]

No man's land

The space between the opposing trenches was referred to as "no man's land" and varied in width depending on the battlefield. On the Western Front it was typically between 90 and 275 metres (100 and 300 yd), though only 25 metres (30 yd) on Vimy Ridge.

After the German withdrawal to the Hindenburg Line in March 1917, no man's land stretched to over a kilometre in places. At the "Quinn's Post" in the cramped confines of the Anzac battlefield at Gallipoli, the opposing trenches were only 15 metres (16 yd) apart and the soldiers in the trenches constantly threw hand grenades at each other. On the Eastern Front and in the Middle East, the areas to be covered were so vast, and the distances from the factories supplying shells, bullets, concrete and barbed wire so great, trench warfare in the West European style often did not occur.

Weaponry

Infantry weapons and machine guns

At the start of the First World War, the standard infantry soldier's primary weapons were the rifle and bayonet; other weapons got less attention. Especially for the British, what hand grenades were issued tended to be few in numbers and less effective. This emphasis began to shift as soon as trench warfare began; militaries rushed improved grenades into mass production, including rifle grenades.

The hand grenade came to be one of the primary infantry weapons of trench warfare. Both sides were quick to raise specialist grenadier groups. The grenade enabled a soldier to engage the enemy without exposing himself to fire, and it did not require precise accuracy to kill or maim. Another benefit was that if a soldier could get close enough to the trenches, enemies hiding in trenches could be attacked. The Germans and Turks were well equipped with grenades from the start of the war, but the British, who had ceased using grenadiers in the 1870s and did not anticipate a siege war, entered the conflict with virtually none, so soldiers had to improvise bombs with whatever was available (see Jam Tin Grenade). By late 1915, the British Mills bomb had entered wide circulation, and by the end of the war 75 million had been used.

Since the troops were often not adequately equipped for trench warfare, improvised weapons were common in the first encounters, such as short wooden clubs and metal maces, spears, hatchets, hammers, entrenching tools, as well as trench knives and brass knuckles. According to the semi-biographical war novel All Quiet on the Western Front, many soldiers preferred to use a sharpened spade as an improvised melee weapon instead of the bayonet, as the bayonet tended to get "stuck" in stabbed opponents, rendering it useless in heated battle. The shorter length also made them easier to use in the confined quarters of the trenches. These tools could then be used to dig in after they had taken a trench. Modern military digging tools are as a rule designed to also function as a melee weapon. As the war progressed, better equipment was issued, and improvised arms were discarded.

A specialised group of fighters called trench sweepers (Nettoyeurs de Tranchées or Zigouilleurs) evolved to fight within the trenches. They cleared surviving enemy personnel from recently overrun trenches and made clandestine raids into enemy trenches to gather intelligence. Volunteers for this dangerous work were often exempted from participation in frontal assaults over open ground and from routine work like filling sandbags, draining trenches, and repairing barbed wire in no-man's land. When allowed to choose their own weapons, many selected grenades, knives and pistols. FN M1900 pistols were highly regarded for this work, but never available in adequate quantities. Colt Model 1903 Pocket Hammerless, Savage Model 1907, Star Bonifacio Echeverria and Ruby pistols were widely used.[37]

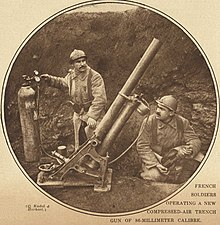

Various mechanical devices were invented for throwing hand grenades into enemy trenches. The Germans used the Wurfmaschine, a spring-powered device for throwing a hand grenade about 200 m (220 yd).[38] The French responded with the Sauterelle and the British with the Leach Trench Catapult and West Spring Gun which had varying degrees of success and accuracy. By 1916, catapult weapons were largely replaced by rifle grenades and mortars.[39]

The Germans employed Flammenwerfer (flamethrowers) during the war for the first time against the French on 25 June 1915, then against the British 30 July in Hooge. The technology was in its infancy, and use was not very common until the end of 1917 when portability and reliability were improved. It was used in more than 300 documented battles. By 1918, it became a weapon of choice for Stoßtruppen (stormtroopers) with a team of six Pioniere (combat engineers) per squad.

Used by American soldiers in the Western front, the pump action shotgun was a formidable weapon in short range combat, enough so that Germany lodged a formal protest against their use on 14 September 1918, stating "every prisoner found to have in his possession such guns or ammunition belonging thereto forfeits his life", though this threat was apparently never carried out. The U.S. military began to issue models specially modified for combat, called "trench guns", with shorter barrels, higher capacity magazines, no choke, and often heat shields around the barrel, as well as lugs for the M1917 bayonet. Anzac and some British soldiers were also known to use sawn-off shotguns in trench raids, because of their portability, effectiveness at close range, and ease of use in the confines of a trench. This practice was not officially sanctioned, and the shotguns used were invariably modified sporting guns.

The Germans embraced the machine gun from the outset—in 1904, sixteen units were equipped with the 'Maschinengewehr'—and the machine gun crews were the elite infantry units; these units were attached to Jaeger (light infantry) battalions. By 1914, British infantry units were armed with two Vickers machine guns per battalion; the Germans had six per battalion, and the Russians eight.[40] It would not be until 1917 that every infantry unit of the American forces carried at least one machine gun.[41] After 1915, the Maschinengewehr 08 was the standard issue German machine gun; its number "08/15" entered the German language as idiomatic for "dead plain". At Gallipoli and in Palestine the Turks provided the infantry, but it was usually Germans who manned the machine guns.

The British High Command were less enthusiastic about machine guns, supposedly considering the weapon too "unsporting" and encouraging defensive fighting; and they lagged behind the Germans in adopting it. Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig is quoted as saying in 1915, "The machine gun is a much overrated weapon; two per battalion is more than sufficient".[42] The defensive firepower of the machine gun was exemplified during the first day of the Battle of the Somme when 60,000 British soldiers were rendered casualties, "the great majority lost under withering machine gun fire".[43] In 1915 the Machine Gun Corps was formed to train and provide sufficient heavy machine gun teams.

It was the Canadians that made the best practice, pioneering area denial and indirect fire (soon adopted by all Allied armies) under the guidance of former French Army Reserve officer Major General Raymond Brutinel. Minutes before the attack on Vimy Ridge the Canadians thickened the artillery barrage by aiming machine guns indirectly to deliver plunging fire on the Germans. They also significantly increased the number of machine guns per battalion. To match demand, production of the Vickers machine gun was contracted to firms in the United States. By 1917, every company in the British forces were also equipped with four Lewis light machine guns, which significantly enhanced their firepower.

The heavy machine gun was a specialist weapon, and in a static trench system was employed in a scientific manner, with carefully calculated fields of fire, so that at a moment's notice an accurate burst could be fired at the enemy's parapet or a break in the wire. Equally it could be used as light artillery in bombarding distant trenches. Heavy machine guns required teams of up to eight men to move them, maintain them, and keep them supplied with ammunition. This made them impractical for offensive manoeuvres, contributing to the stalemate on the Western Front.

One machine gun nest was theoretically able to mow down hundreds of enemies charging in the open through no man's land. However, while WWI machine guns were able to shoot hundreds of rounds per minute in theory, they were still prone to overheating and jamming, which often necessitated firing in short bursts.[44] However, their potential was increased significantly when emplaced behind multiple lines of barbed wire to slow any advancing enemy.

In 1917 and 1918, new types of weapons were fielded. They changed the face of warfare tactics and were later employed during World War II.

The French introduced the CSRG 1915 Chauchat during Spring 1916 around the concept of "walking fire", employed in 1918 when 250,000 weapons were fielded. More than 80,000 of the best shooters received the semi-automatic RSC 1917 rifle, allowing them to rapid fire at waves of attacking soldiers. Firing ports were installed in the newly arrived Renault FT tanks.

The French Army fielded a ground version of the Hotchkiss Canon de 37 mm used by the French Navy. It was primarily used to destroy German machine gun nests and concrete reinforced pillboxes with high explosive and armour-piercing rounds.

A new type of machine gun was introduced in 1916. Initially an aircraft weapon, the Bergmann LMG 15 was modified for ground use, with the later dedicated ground version being the LMG 15 n. A. It was used as an infantry weapon on all European and Middle Eastern fronts until the end of World War I. It later inspired the MG 30 and the MG 34 as well as the concept of the general-purpose machine gun.

What became known as the submachine gun had its genesis in World War I, developed around the concepts of infiltration and fire and movement, specifically to clear trenches of enemy soldiers when engagements were unlikely to occur beyond a range of a few feet. The MP 18 was the first practical submachine gun used in combat. It was fielded in 1918 by the German Army as the primary weapon of the stormtroopers – assault groups that specialised in trench combat. Around the same time, the Italians had developed the Beretta M1918 submachine gun, based on a design from earlier in the war.

Artillery

Artillery dominated the battlefields of trench warfare. An infantry attack was rarely successful if it advanced beyond the range of its supporting artillery. In addition to bombarding the enemy infantry in the trenches, the artillery could be used to precede infantry advances with a creeping barrage, or engage in counter-battery duels to try to destroy the enemy's guns. Artillery mainly fired fragmentation, high-explosive, shrapnel or, later in the war, gas shells. The British experimented with firing thermite incendiary shells, to set trees and ruins alight. However, all armies experienced shell shortages during the first year or two of World War I, due to underestimating their usage in intensive combat. This knowledge had been gained by the combatant nations in the Russo-Japanese War, when daily artillery fire consumed ten times more than daily factory output, but had not been applied.[45]

Artillery pieces were of two types: infantry support guns and howitzers. Guns fired high-velocity shells over a flat trajectory and were often used to deliver fragmentation and to cut barbed wire. Howitzers lofted the shell over a high trajectory so it plunged into the ground. The largest calibers were usually howitzers. The German 420 mm (17 in) howitzer weighed 20 tons and could fire a one-ton shell over 10 km (6.2 mi). A critical feature of period artillery pieces was the hydraulic recoil mechanism, which meant the gun did not need to be re-aimed after each shot, permitting a tremendous increase in rate of fire.

Initially each gun would need to register its aim on a known target, in view of an observer, in order to fire with precision during a battle. The process of gun registration would often alert the enemy an attack was being planned. Towards the end of 1917, artillery techniques were developed enabling fire to be delivered accurately without registration on the battlefield—the gun registration was done behind the lines then the pre-registered guns were brought up to the front for a surprise attack.

Mortars, which lobbed a shell in a high arc over a relatively short distance, were widely used in trench fighting for harassing the forward trenches, for cutting wire in preparation for a raid or attack, and for destroying dugouts, saps and other entrenchments. In 1914, the British fired a total of 545 mortar shells; in 1916, they fired over 6,500,000. Similarly, howitzers, which fire on a more direct arc than mortars, raised in number from over 1,000 shells in 1914, to over 4,500,000 in 1916. The smaller numerical difference in mortar rounds, as opposed to howitzer rounds, is presumed by many to be related to the expanded costs of manufacturing the larger and more resource intensive howitzer rounds.

The main British mortar was the Stokes, a precursor of the modern mortar. It was a light mortar, simple in operation, and capable of a rapid rate of fire by virtue of the propellant cartridge being attached to the base shell. To fire the Stokes mortar, the round was simply dropped into the tube, where the percussion cartridge was detonated when it struck the firing pin at the bottom of the barrel, thus being launched. The Germans used a range of mortars. The smallest were grenade-throwers ('Granatenwerfer') which fired the stick grenades which were commonly used. Their medium trench-mortars were called mine-throwers ('Minenwerfer'). The heavy mortar was called the 'Ladungswerfer', which threw "aerial torpedoes", containing a 200 lb (91 kg) charge to a range of 1,000 yd (910 m). The flight of the missile was so slow and leisurely that men on the receiving end could make some attempt to seek shelter.

Mortars had certain advantages over artillery such as being much more portable and the ability to fire without leaving the relative safety of trenches. Moreover, mortars were able to fire directly into the trenches, which was hard to do with artillery.[46]

Strategy and tactics

The fundamental strategy of trench warfare in World War I was to defend one's own position strongly while trying to achieve a breakthrough into the enemy's rear. The effect was to end up in attrition; the process of progressively grinding down the opposition's resources until, ultimately, they are no longer able to wage war. This did not prevent the ambitious commander from pursuing the strategy of annihilation—the ideal of an offensive battle which produces victory in one decisive engagement.

The Commander in Chief of the British forces during most of World War I, General Douglas Haig, was constantly seeking a "breakthrough" which could then be exploited with cavalry divisions. His major trench offensives—the Somme in 1916 and Flanders in 1917—were conceived as breakthrough battles but both degenerated into costly attrition. The Germans actively pursued a strategy of attrition in the Battle of Verdun, the sole purpose of which was to "bleed the French Army white". At the same time the Allies needed to mount offensives in order to draw attention away from other hard-pressed areas of the line.[47]

The popular image of a trench assault is of a wave of soldiers, bayonets fixed, going "over the top" and marching in a line across no man's land into a hail of enemy fire. This was the standard method early in the war; it was rarely successful. More common was an attack at night from an advanced post in no man's land, having cut the barbed wire beforehand. In 1915, the Germans innovated with infiltration tactics where small groups of highly trained and well-equipped troops would attack vulnerable points and bypass strong points, driving deep into the rear areas. The distance they could advance was still limited by their ability to supply and communicate.

The role of artillery in an infantry attack was twofold. The first aim of a bombardment was to prepare the ground for an infantry assault, killing or demoralising the enemy garrison and destroying their defences. The duration of these initial bombardments varied, from seconds to days. Artillery bombardments prior to infantry assaults were often ineffective at destroying enemy defences, only serving to provide advance notice of an attack. The British bombardment that began the Battle of the Somme lasted eight days but did little damage to either the German barbed wire or their deep dug-outs, where defenders were able to wait out the bombardment in relative safety.[48]

Once the guns stopped, the defenders had time to emerge and were usually ready for the attacking infantry. The second aim was to protect the attacking infantry by providing an impenetrable "barrage" or curtain of shells to prevent an enemy counter-attack. The first attempt at sophistication was the "lifting barrage" where the first objective of an attack was intensely bombarded for a period before the entire barrage "lifted" to fall on a second objective farther back. However, this usually expected too much of the infantry, and the usual outcome was that the barrage would outpace the attackers, leaving them without protection.

This resulted in the use of the "creeping barrage" which would lift more frequently but in smaller steps, sweeping the ground ahead and moving so slowly that the attackers could usually follow closely behind it. This became the standard method of attack from late 1916 onward. The main benefit of the barrage was suppression of the enemy rather than to cause casualties or material damage.

Capturing the objective was half the battle, but the battle was won only if the objective was held. The attacking force would have to advance with not only the weapons required to capture a trench but also the tools—sandbags, picks and shovels, barbed wire—to fortify and defend from counter-attack. A successful advance would take the attackers beyond the range of their own field artillery, making them vulnerable, and it took time to move guns up over broken ground. The Germans placed great emphasis on immediately counter-attacking to regain lost ground. This strategy cost them dearly in 1917 when the British started to limit their advances so as to be able to meet the anticipated counter-attack from a position of strength. Part of the British artillery was positioned close behind the original start line and took no part in the initial bombardment, so as to be ready to support later phases of the operation while other guns were moved up.

The Germans were the first to apply the concept of "defence in depth", where the front-line zone was hundreds of metres deep and contained a series of redoubts rather than a continuous trench. Each redoubt could provide supporting fire to its neighbours, and while the attackers had freedom of movement between the redoubts, they would be subjected to withering enfilade fire. They were also more willing than their opponents to make a strategic withdrawal to a superior prepared defensive position. The British eventually adopted a similar approach, but it was incompletely implemented when the Germans launched the 1918 Spring Offensive and proved disastrously ineffective. France, by contrast, relied on artillery and reserves, not entrenchment.

Life in the trenches

An individual unit's time in a front-line trench was usually brief; from as little as one day to as much as two weeks at a time before being relieved. The 31st Australian Battalion once spent 53 days in the line at Villers-Bretonneux, but such a duration was a rare exception. The 10th Battalion, CEF, averaged frontline tours of six days in 1915 and 1916.[49] The units who manned the frontline trenches the longest were the Portuguese Expeditionary Corps from Portugal stationed in Northern France; unlike the other allies the Portuguese couldn't rotate units from the front lines due to lack of reinforcements sent from Portugal, nor could they replace the depleted units that lost manpower due to the war of attrition. With this rate of casualties and no reinforcements forthcoming, most of the men were denied leave and had to serve long periods in the trenches with some units spending up to six consecutive months in the front line with little to no leave during that time.[50]

On an individual level, a typical British soldier's year could be divided as follows:

- 15% front line

- 10% support line

- 30% reserve line

- 20% rest

- 25% other (hospital, travelling, leave, training courses, etc.)

Even when in the front line, the typical battalion would be called upon to engage in fighting only a handful of times a year; making an attack, defending against an attack or participating in a raid. The frequency of combat would increase for the units of the "elite" fighting divisions; on the Allied side, these were the British regular divisions, the Canadian Corps, the French XX Corps, and the Anzacs.

Some sectors of the front saw little activity throughout the war, making life in the trenches comparatively easy. When the I Anzac Corps first arrived in France in April 1916 after the evacuation of Gallipoli, they were sent to a relatively peaceful sector south of Armentières to "acclimatise". In contrast, some other sectors were in a perpetual state of violent activity. On the Western Front, Ypres was invariably hellish, especially for the British in the exposed, overlooked salient. However, even quiet sectors amassed daily casualties through sniper fire, artillery, disease, and poison gas. In the first six months of 1916, before the launch of the Somme Offensive, the British did not engage in any significant battles on their sector of the Western Front and yet suffered 107,776 casualties.

A sector of the front would be allocated to an army corps, usually comprising three divisions. Two divisions would occupy adjacent sections of the front, and the third would be in rest to the rear. This breakdown of duty would continue down through the army structure, so that within each front-line division, typically comprising three infantry brigades (regiments for the Germans), two brigades would occupy the front and the third would be in reserve. Within each front-line brigade, typically comprising four battalions, two battalions would occupy the front with two in reserve, and so on for companies and platoons. The lower down the structure this division of duty proceeded, the more frequently the units would rotate from front-line duty to support or reserve.

During the day, snipers and artillery observers in balloons made movement perilous, so the trenches were mostly quiet. It was during these daytime hours that the soldiers would amuse themselves with trench magazines. Because of the peril associated with daytime activities, trenches were busiest at night when the cover of darkness allowed movement of troops and supplies, the maintenance and expansion of the barbed wire and trench system, and reconnaissance of the enemy's defences. Sentries in listening posts out in no man's land would try to detect enemy patrols and working parties, or indications that an attack was being prepared.

Pioneered by the Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry in February 1915,[51] trench raids were carried out in order to capture prisoners and "booty"—letters and other documents to provide intelligence about the unit occupying the opposing trenches. As the war progressed, raiding became part of the general British policy, the intention being to maintain the fighting spirit of the troops and to deny no man's land to the Germans. As well, they were intended to compel the enemy to reinforce, which exposed their troops to artillery fire.[51]

Such dominance was achieved at a high cost when the enemy replied with their own artillery,[51] and a post-war British analysis concluded the benefits were probably not worth the cost. Early in the war, surprise raids would be mounted, particularly by the Canadians, but increased vigilance made achieving surprise difficult as the war progressed. By 1916, raids were carefully planned exercises in combined arms and involved close co-operation between infantry and artillery.

A raid would begin with an intense artillery bombardment designed to drive off or kill the front-trench garrison and cut the barbed wire. Then the bombardment would shift to form a "box barrage", or cordon, around a section of the front line to prevent a counter-attack intercepting the raid. However, the bombardment also had the effect of notifying the enemy of the location of the planned attack, thus allowing reinforcements to be called in from wider sectors.

Dangers

Approximately 10–15 percent of all soldiers who fought in the First World War died as a result.[52]

While the main cause of death in the trenches came from shelling and gunfire, diseases and infections were always present, and became prevalent for all sides as the war progressed. Medical procedures, while considerably more effective than at any previous time in history, were still not very helpful; antibiotics had not yet been discovered or invented. As a result, an infection caught in a trench often went untreated and could fester until the soldier died.

Injuries

The main killer in the trenches was artillery fire; around 75 percent of known casualties.[53] Even if a soldier was not hit directly by the artillery, shell fragments and debris had a high chance of wounding those in close proximity to the blast. Artillery use increased tremendously during the war; for example, the percentage of the French army that was artillerymen grew from 20 percent in 1914 to 38 percent by 1918.[53] The second largest contributor to death was gunfire (bullets from rifles and machine-guns), which was responsible for 34 percent of French military casualties.[52]

Once the war entered the static phase of trench warfare, the number of lethal head wounds that troops were receiving from fragmentation increased dramatically. The French were the first to see a need for greater protection and began to introduce steel helmets in the summer of 1915. The Adrian helmet replaced the traditional French kepi and was later adopted by the Belgian, Italian and many other armies. At about the same time the British were developing their own helmets. The French design was rejected as not strong enough and too difficult to mass-produce. The design that was eventually approved by the British was the Brodie helmet. This had a wide brim to protect the wearer from falling objects, but offered less protection to the wearer's neck. When the Americans entered the war, this was the helmet they chose, though some units used the French Adrian helmet.

Disease

The predominant disease in the trenches of the Western Front was trench fever. Trench fever was a common disease spread through the faeces of body lice, which were rampant in trenches. Trench fever caused headaches, shin pain, splenomegaly, rashes and relapsing fevers – resulting in lethargy for months.[54] First reported on the Western Front in 1915 by a British medical officer, additional cases of trench fever became increasingly common mostly in the frontline troops.[55] In 1921, microbiologist Sir David Bruce reported that over one million Allied soldiers were infected by trench fever throughout the war.[56] Even after the Great War had ended, disabled veterans in Britain attributed their decreasing quality of life to trench fever they had sustained during wartime.

Early in the war, gas gangrene commonly developed in major wounds, in part because the Clostridium bacteria responsible are ubiquitous in manure-fertilized soil[57] (common in western European agriculture, such as France and Belgium), and dirt would often get into a wound (or be rammed in by shrapnel, explosion, or bullet). In 1914, 12% of wounded British soldiers developed gas gangrene, and at least 100,000 German soldiers died directly from the infection.[58] After rapid advances in medical procedures and practices, the incidence of gas gangrene fell to 1% by 1918.[59]

Entrenched soldiers also carried many intestinal parasites, such as ascariasis, trichuriasis and tapeworm.[60] These parasites were common amongst soldiers, and spread amongst them, due to the unhygienic environment created by the common trench, where there were no true sewage management procedures. This ensured that parasites (and diseases) would spread onto rations and food sources that would then be eaten by other soldiers.[60]

Trench foot was a common environmental ailment affecting many soldiers, especially during the winter. It is one of several immersion foot syndromes. It was characterized by numbness and pain in the feet, but in bad cases could result in necrosis of the lower limbs. Trench foot was a large problem for the Allied forces, resulting in 2000 American and 75,000 British casualties.[61] Mandatory routine (daily or more often) foot inspections by fellow soldiers, along with systematic use of soap, foot powder, and changing socks, greatly reduced cases of trench foot.[62] In 1918, US infantry were issued with an improved and more waterproof 'Pershing boot' in an attempt to reduce casualties from trench foot.

To the surprise of medical professionals at the time, there was no outbreak of typhus in the trenches of the Western Front, despite the cold and harsh conditions being perfect for the reproduction of body lice that transmit the disease.[63] However, on the Eastern Front an epidemic of typhus claimed between 150,000 – 200,000 lives in Serbia.[64] Russia also suffered a globally unprecedented typhus epidemic during the last two years of the conflict that was exacerbated by harsh winters. This outbreak resulted in approximately 2.5 million recorded deaths, 100,000 of them being Red Army soldiers.[65] Symptoms of typhus include a characteristic spotted rash (which was not always present), severe headache, sustained high fever of 39 °C (102 °F), cough, severe muscle pain, chills, falling blood pressure, stupor, sensitivity to light, and delirium; 10% to 60% die. Typhus is spread by body lice.

Trench rats

The trenches were inhabitated by millions of rats which were often responsible for the spread of diseases. Soldiers' attempts to cull hordes of trench rats with rifle bayonets were common early in the war, but the rats reproduced faster than they could be slaughtered.[66] However, soldiers still partook in rat hunts as a form of entertainment. Rats would feed on half-eaten or uneaten rations as well as corpses. Many soldiers were more afraid of rats than other horrors found in the trenches.[67]

Psychological impact

Nervous and mental breakdowns amongst soldiers were common, due to unrelenting shellfire and the claustrophobic trench environment.[68] Men who suffered such intense breakdowns were often rendered completely immobile, and were often seen cowering low in the trenches, unable even to perform instinctive human responses such as running away or fighting back. This condition came to be known as "shell shock", "war neurosis" or "battle hypnosis".[69] Although trenches provided cover from shelling and small-arms fire, they also amplified the psychological effects of shell shock, as there was no way to escape a trench if shellfire was coming.[70] If a soldier became too debilitated from shell shock, they were evacuated from the trench and hospitalized if possible.[71] In some cases, shell shocked soldiers were executed for "cowardice" by their commanders as they became a liability.[72] This was often done by a firing squad composed of their fellow soldiers – often from the same unit.[73] Only years later would it be understood that such men were suffering from shell shock. During the war, 306 British soldiers were officially executed by their own side.[74]

Circumvention

Throughout World War I, the major combatants slowly developed different ways of breaking the stalemate of trench warfare; the Germans focused more on new tactics while the British and French focused on tanks.

Infiltration tactics

As far back as the 18th century, Prussian military doctrine (Vernichtungsgedanke) stressed manoeuvre and force concentration to achieve a decisive battle. The German military searched for ways to apply this in the face of trench warfare. Experiments with new tactics by Willy Rohr, a Prussian captain serving in the Vosges mountains in 1915, got the attention of the Minister of War. These tactics carried Prussian military doctrine down to smallest units — specially trained troops manoeuvred and massed to assault positions they chose on their own.[75] During the next two years the German army tried to establish special stormtrooper detachments in all its units by sending selected men to Rohr and have those men then train their comrades in their original units.

Similar tactics were developed independently in other countries, such as French Army captain André Laffargue in 1915 and Russian general Aleksei Brusilov in 1916, but these failed to be adopted as any military doctrine.[76]

The German stormtrooper methods involved men rushing forward in small groups using whatever cover was available and laying down covering fire for other groups in the same unit as they moved forward. The new tactics, intended to achieve surprise by disrupting entrenched enemy positions, aimed to bypass strongpoints and to attack the weakest parts of an enemy's line. Additionally, they acknowledged the futility of managing a grand detailed plan of operations from afar, opting instead for junior officers on the spot to exercise initiative.[77]

The Germans employed and improved infiltration tactics in a series of smaller to larger battles, each increasingly successful, leading up to the Battle of Caporetto against the Italians in 1917, and finally the massive German spring offensive in 1918 against the British and French. German infiltration tactics are sometimes called "Hutier tactics" by others, after Oskar von Hutier, the general leading the German 18th Army, which had the farthest advance in that offensive. After a stunningly rapid advance, the offensive failed to achieve a breakthrough; German forces stalled after outrunning their supply, artillery, and reinforcements, which could not catch up over the shell-torn ground left ruined by Allied attacks in the Battle of the Somme in 1916. The exhausted German forces were soon pushed back in the Allied Hundred Days Offensive, and the Germans were unable to organise another major offensive before the war's end. In post-war years, other nations did not fully appreciate these German tactical innovations amidst the overall German defeat.

Mining

Mines – tunnels under enemy lines packed with explosives and detonated – were widely used in WWI to destroy or disrupt enemy's trench lines. Mining and counter-mining became a major part of trench warfare.[78][79]