Glottochronology (from Attic Greek γλῶττα tongue, language and χρόνος time) is the part of lexicostatistics which involves comparative linguistics and deals with the chronological relationship between languages.[1]: 131

The idea was developed by Morris Swadesh in the 1950s in his article on Salish internal relationships.[2] He developed the idea under two assumptions: there indeed exists a relatively stable basic vocabulary (referred to as Swadesh lists) in all languages of the world; and, any replacements happen in a way analogous to radioactive decay in a constant percentage per time elapsed. Using mathematics and statistics, Swadesh developed an equation to determine when languages separated and give an approximate time of when the separation occurred. His methods aimed to aid linguistic anthropologists by giving them a definitive way to determine a separation date between two languages. The formula provides an approximate number of centuries since two languages were supposed to have separated from a singular common ancestor. His methods also purported to provide information on when ancient languages may have existed.[3]

Despite multiple studies and literature containing the information of glottochronology, it is not widely used today and is surrounded with controversy.[3] Glottochronology tracks language separation from thousands of years ago but many linguists are skeptical of the concept because it is more of a 'probability' rather than a 'certainty.' On the other hand, some linguists may say that glottochronology is gaining traction because of its relatedness to archaeological dates. Glottochronology is not as accurate as archaeological data, but some linguists still believe that it can provide a solid estimate.[4]

Over time many different extensions of the Swadesh method evolved; however, Swadesh's original method is so well known that 'glottochronology' is usually associated with him.[1]: 133 [5]

Methodology

Word list

The original method of glottochronology presumed that the core vocabulary of a language is replaced at a constant (or constant average) rate across all languages and cultures and so can be used to measure the passage of time. The process makes use of a list of lexical terms and morphemes which are similar to multiple languages.

Lists were compiled by Morris Swadesh and assumed to be resistant against borrowing (originally designed in 1952 as a list of 200 items, but the refined 100-word list in Swadesh (1955)[6] is much more common among modern day linguists). The core vocabulary was designed to encompass concepts common to every human language such as personal pronouns, body parts, heavenly bodies and living beings, verbs of basic actions, numerals, basic adjectives, kin terms, and natural occurrences and events.[7] Through a basic word list, one eliminates concepts that are specific to a particular culture or time period. It has been found through differentiating word lists that the ideal is really impossible and that the meaning set may need to be tailored to the languages being compared. Word lists are not homogenous throughout studies and they are often changed and designed to suit both languages being studied. Linguists find that it is difficult to find a word list where all words used are culturally unbiased.[8] Many alternative word lists have been compiled by other linguists and often use fewer meaning slots.

The percentage of cognates (words with a common origin) in the word lists is then measured. The larger the percentage of cognates, the more recently the two languages being compared are presumed to have separated.

Below is an example of a basic word list composed of basic Turkish words and their English translations.[9]

| hep (all) | ateş (fire) | boyun (neck) | bu (that) |

| kül (ashes) | balık (fish) | yeni (new) | şu (this) |

| kabuk (bark) | uçmak (fly) | gece (night) | sen (thou) |

| karın (belly) | ayak (foot) | burun (nose) | dil (tongue) |

| büyük (big) | vermek (give) | bir (one) | diş (tooth) |

| kuş (bird) | iyi (good) | kişi (person) | ağaç (tree) |

| ısırmak (bite) | yeşil (green) | yağmur (rain) | iki (two) |

| kara (black) | saç (hair) | kızıl (red) | yürümek (walk) |

| kan (blood) | el (hand) | yol (road) | sıcak (warm) |

| kemik (bone) | baş (head) | kök (root) | su (water) |

| yakmak (burn) | duymak (hear) | kum (sand) | biz (we) |

| bulut (cloud) | gönül (heart) | demek (say) | ne (what) |

| soğuk (cold) | ben (I) | görmek (see) | beyaz (white) |

| gelmek (come) | öldürmek (kill) | tohum (seed) | kim (who) |

| ölmek (die) | bilmek (know) | oturmak (sit) | kadın (woman) |

| köpek (dog) | yaprak (leaf) | deri (skin) | sarı (yellow) |

| içmek (drink) | yalan (lie) | uyumak (sleep) | uzun (long) |

| kuru (dry) | ciğer (liver) | küçük (small) | yok (not) |

| kulak (ear) | bit (louse) | duman (smoke) | göğüş (breast) |

| yer (earth) | erkek (man-male) | ayaktakalmak (stand) | hayvan tırnagı (claw) |

| yemek (eat) | çok (many) | yıldız (star) | dolu (full) |

| yumurta (egg) | et (meat-flesh) | taş (stone) | boynuz (horn) |

| göz (eye) | dağ (mountain) | güneş (sun) | diz (knee) |

| yağ (fat-grease) | ağız (mouth) | yüzmek (swim) | ay (moon) |

| tüy (feather) | isim (name) | kuyruk (tail) | yuvarlak (round) |

Glottochronologic constant

Determining word lists rely on morpheme decay or change in vocabulary. Morpheme decay must stay at a constant rate for glottochronology to be applied to a language. This leads to a critique of the glottochronologic formula because some linguists argue that the morpheme decay rate is not guaranteed to stay the same throughout history.[8]

American Linguist Robert Lees obtained a value for the "glottochronological constant" (r) of words by considering the known changes in 13 pairs of languages using the 200 word list. He obtained a value of 0.805 ± 0.0176 with 90% confidence. For his 100-word list Swadesh obtained a value of 0.86, the higher value reflecting the elimination of semantically unstable words. The constant is related to the retention rate of words by the following formula:

L is the rate of replacement, ln represents the natural logarithm and r is the glottochronological constant.

Divergence time

The basic formula of glottochronology in its shortest form is this:

t = a given period of time from one stage of the language to another (measured in millennia),[10] c = proportion of wordlist items retained at the end of that period and L = rate of replacement for that word list.

One can also therefore formulate:

By testing historically verifiable cases in which t is known by nonlinguistic data (such as the approximate distance from Classical Latin to modern Romance languages), Swadesh arrived at the empirical value of approximately 0.14 for L, which means that the rate of replacement constitutes around 14 words from the 100-wordlist per millennium.

Results

Glottochronology was found to work in the case of Indo-European, accounting for 87% of the variance. It is also postulated to work for Afro-Asiatic (Fleming 1973), Chinese (Munro 1978) and Amerind (Stark 1973; Baumhoff and Olmsted 1963). For Amerind, correlations have been obtained with radiocarbon dating and blood groups[dubious ] as well as archaeology.[citation needed]

The approach of Gray and Atkinson,[11] as they state, has nothing to do with "glottochronology".

Discussion

The concept of language change is old, and its history is reviewed in Hymes (1973) and Wells (1973). In some sense, glottochronology is a reconstruction of history and can often be closely related to archaeology. Many linguistic studies find the success of glottochronology to be found alongside archaeological data.[4] Glottochronology itself dates back to the mid-20th century.[6][12][7] An introduction to the subject is given in Embleton (1986)[13] and in McMahon and McMahon (2005).[14]

Glottochronology has been controversial ever since, partly because of issues of accuracy but also because of the question of whether its basis is sound (for example, Bergsland 1958; Bergsland and Vogt 1962; Fodor 1961; Chrétien 1962; Guy 1980). The concerns have been addressed by Dobson et al. (1972), Dyen (1973)[15] and Kruskal, Dyen and Black (1973).[16] The assumption of a single-word replacement rate can distort the divergence-time estimate when borrowed words are included (Thomason and Kaufman 1988).

An overview of recent arguments can be obtained from the papers of a conference held at the McDonald Institute in 2000.[17] The presentations vary from "Why linguists don't do dates" to the one by Starostin discussed above.[clarification needed] Since its original inception, glottochronology has been rejected by many linguists, mostly Indo-Europeanists of the school of the traditional comparative method. Criticisms have been answered in particular around three points of discussion:

- Criticism levelled against the higher stability of lexemes in Swadesh lists alone (Haarmann 1990) misses the point because a certain amount of losses only enables the computations (Sankoff 1970). The non-homogeneity of word lists often leads to lack of understanding between linguists. Linguists also have difficulties finding a completely unbiased list of basic cultural words. it can take a long time for linguists to find a viable word list which can take several test lists to find a usable list.[8]

- Traditional glottochronology presumes that language changes at a stable rate.

- Thus, in Bergsland & Vogt (1962), the authors make an impressive demonstration, on the basis of actual language data verifiable by extralinguistic sources, that the "rate of change" for Icelandic constituted around 4% per millennium, but for closely connected Riksmal (Literary Norwegian), it would amount to as much as 20% (Swadesh's proposed "constant rate" was supposed to be around 14% per millennium).

- That and several other similar examples effectively proved that Swadesh's formula would not work on all available material, which is a serious accusation since evidence that can be used to "calibrate" the meaning of L (language history recorded during prolonged periods of time) is not overwhelmingly large in the first place.

- It is highly likely that the chance of replacement is different for every word or feature ("each word has its own history", among hundreds of other sources:[18]).

- That global assumption has been modified and downgraded to single words, even in single languages, in many newer attempts (see below).

- There is a lack of understanding of Swadesh's mathematical/statistical methods. Some linguists reject the methods in full because the statistics lead to 'probabilities' when linguists trust 'certainties' more.[8]

- A serious argument is that language change arises from socio-historical events that are, of course, unforeseeable and, therefore, uncomputable.

- New methods developed by Gray & Atkinson are claimed to avoid those issues but are still seen as controversial, primarily since they often produce results that are incompatible with known data and because of additional methodological issues.

Modifications

Somewhere in between the original concept of Swadesh and the rejection of glottochronology in its entirety lies the idea that glottochronology as a formal method of linguistic analysis becomes valid with the help of several important modifications. Thus, inhomogeneities in the replacement rate were dealt with by Van der Merwe (1966)[8] by splitting the word list into classes each with their own rate, while Dyen, James and Cole (1967)[19] allowed each meaning to have its own rate. Simultaneous estimation of divergence time and replacement rate was studied by Kruskal, Dyen and Black.[16]

Brainard (1970) allowed for chance cognation, and drift effects were introduced by Gleason (1959). Sankoff (1973) suggested introducing a borrowing parameter and allowed synonyms.

A combination of the various improvements is given in Sankoff's "Fully Parameterised Lexicostatistics". In 1972, Sankoff in a biological context developed a model of genetic divergence of populations. Embleton (1981) derives a simplified version of that in a linguistic context. She carries out a number of simulations using this which are shown to give good results.

Improvements in statistical methodology related to a completely different branch of science, phylogenetics; the study of changes in DNA over time sparked a recent renewed interest. The new methods are more robust than the earlier ones because they calibrate points on the tree with known historical events and smooth the rates of change across them. As such, they no longer require the assumption of a constant rate of change (Gray & Atkinson 2003).

Starostin's method

Another attempt to introduce such modifications was performed by the Russian linguist Sergei Starostin, who had proposed the following:

- Systematic loanwords, borrowed from one language into another, are a disruptive factor and must be eliminated from the calculations; the one thing that really matters is the "native" replacement of items by items from the same language. The failure to notice that factor was a major reason in Swadesh's original estimation of the replacement rate at under 14 words from the 100-wordlist per millennium, but the real rate is much slower (around 5 or 6). Introducing that correction effectively cancels out the "Bergsland & Vogt" argument since a thorough analysis of the Riksmal data shows that its basic wordlist includes about 15 to 16 borrowings from other Germanic languages (mostly Danish), and the exclusion of those elements from the calculations brings the rate down to the expected rate of 5 to 6 "native" replacements per millennium.

- The rate of change is not really constant but depends on the time period during which the word has existed in the language (the chance of lexeme X being replaced by lexeme Y increases in direct proportion to the time elapsed, the so-called "aging of words" is empirically understood as gradual "erosion" of the word's primary meaning under the weight of acquired secondary ones).

- Individual items on the 100 word-list have different stability rates (for instance, the word "I" generally has a much lower chance of being replaced than the word "yellow").

The resulting formula, taking into account both the time dependence and the individual stability quotients, looks as follows:

In that formula, −Lc reflects the gradual slowing down of the replacement process because of different individual rates since the least stable elements are the first and the quickest to be replaced, and the square root represents the reverse trend, the acceleration of replacement as items in the original wordlist "age" and become more prone to shifting their meaning. This formula is obviously more complicated than Swadesh's original one, but, it yields, as shown by Starostin, more credible results than the former and more or less agrees with all the cases of language separation that can be confirmed by historical knowledge. On the other hand, it shows that glottochronology can really be used only as a serious scientific tool on language families whose historical phonology has been meticulously elaborated (at least to the point of being able to distinguish between cognates and loanwords clearly).

Time-depth estimation

The McDonald Institute hosted a conference on the issue of time-depth estimation in 2000. The published papers[17] give an idea of the views on glottochronology at that time. They vary from "Why linguists don't do dates" to the one by Starostin discussed above. Note that in the referenced Gray and Atkinson paper, they hold that their methods cannot be called "glottochronology" by confining this term to its original method.

See also

- Basic English

- Cognate

- Dolgopolsky list

- Historical linguistics

- Indo-European studies

- Leipzig–Jakarta list

- Lexicostatistics

- Mass lexical comparison

- Proto-language

- Quantitative comparative linguistics

- Swadesh list

References

- Dyen, I., James, A. T., & J. W. L. Cole 1967 "Language divergence and estimated word retention rate", <Language 43: 150--171

Bibliography

- Arndt, Walter W. (1959). The performance of glottochronology in Germanic. Language, 35, 180–192.

- Bergsland, Knut; & Vogt, Hans. (1962). On the validity of glottochronology. Current Anthropology, 3, 115–153.

- Brainerd, Barron (1970). A Stochastic Process related to Language Change. Journal of Applied Probability 7, 69–78.

- Callaghan, Catherine A. (1991). Utian and the Swadesh list. In J. E. Redden (Ed.), Papers for the American Indian language conference, held at the University of California, Santa Cruz, July and August, 1991 (pp. 218–237). Occasional papers on linguistics (No. 16). Carbondale: Department of Linguistics, Southern Illinois University.

- Campbell, Lyle. (1998). Historical Linguistics; An Introduction [Chapter 6.5]. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 0-7486-0775-7.

- Chretien, Douglas (1962). The Mathematical Models of Glottochronology. Language 38, 11–37.

- Crowley, Terry (1997). An introduction to historical linguistics. 3rd ed. Auckland: Oxford Univ. Press. pp. 171–193.

- Dyen, Isidore (1965). "A Lexicostatistical classification of the Austronesian languages." International Journal of American Linguistics, Memoir 19.

- Gray, R.D. & Atkinson, Q.D. (2003): "Language-tree divergence times support the Anatolian theory of Indo-European origin." Nature 426-435-439.

- Gudschinsky, Sarah. (1956). The ABC's of lexicostatistics (glottochronology). Word, 12, 175–210.

- Haarmann, Harald. (1990). "Basic vocabulary and language contacts; the disillusion of glottochronology. In Indogermanische Forschungen 95:7ff.

- Hockett, Charles F. (1958). A course in modern linguistics (Chap. 6). New York: Macmillan.

- Hoijer, Harry. (1956). Lexicostatistics: A critique. Language, 32, 49–60.

- Holm, Hans J. (2003). The Proportionality Trap. Or: What is wrong with lexicostatistical Subgrouping Archived 2019-06-02 at the Wayback Machine.Indogermanische Forschungen, 108, 38–46.

- Holm, Hans J. (2005). Genealogische Verwandtschaft. Kap. 45 in Quantitative Linguistik; ein internationales Handbuch. Herausgegeben von R.Köhler, G. Altmann, R. Piotrowski, Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

- Holm, Hans J. (2007). The new Arboretum of Indo-European 'Trees'; Can new algorithms reveal the Phylogeny and even Prehistory of IE?. Journal of Quantitative Linguistics 14-2:167–214

- Hymes, Dell H. (1960). Lexicostatistics so far. Current Anthropology, 1 (1), 3–44.

- McWhorter, John. (2001). The power of Babel. New York: Freeman. ISBN 978-0-7167-4473-3.

- Nettle, Daniel. (1999). Linguistic diversity of the Americas can be reconciled with a recent colonization. in PNAS 96(6):3325–9.

- Sankoff, David (1970). "On the Rate of Replacement of Word-Meaning Relationships." Language 46.564–569.

- Sjoberg, Andree; & Sjoberg, Gideon. (1956). Problems in glottochronology. American Anthropologist, 58 (2), 296–308.

- Starostin, Sergei. Methodology Of Long-Range Comparison. 2002. pdf

- Thomason, Sarah Grey, and Kaufman, Terrence. (1988). Language Contact, Creolization, and Genetic Linguistics. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Tischler, Johann, 1973. Glottochronologie und Lexikostatistik [Innsbrucker Beiträge zur Sprachwissenschaft 11]; Innsbruck.

- Wittmann, Henri (1969). "A lexico-statistic inquiry into the diachrony of Hittite." Indogermanische Forschungen 74.1–10.[1]

- Wittmann, Henri (1973). "The lexicostatistical classification of the French-based Creole languages." Lexicostatistics in genetic linguistics: Proceedings of the Yale conference, April 3–4, 1971, dir. Isidore Dyen, 89–99. La Haye: Mouton.[2]

- Zipf, George K. (1965). The Psychobiology of Language: an Introduction to Dynamic Philology. Cambridge, MA: M.I.T.Press.

External links

- Swadesh list in Wiktionary.

- Discussion with some statistics

- A simplified explanation of the difference between glottochronology and lexicostatistics.

- Queryable experiment: quantification of the genetic proximity between 110 languages - with trees and discussion

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Glottochronology

Linguistic reconstruction is the practice of establishing the features of an unattested ancestor language of one or more given languages. There are two kinds of reconstruction:

- Internal reconstruction uses irregularities in a single language to make inferences about an earlier stage of that language – that is, it is based on evidence from that language alone.

- Comparative reconstruction, usually referred to just as reconstruction, establishes features of the ancestor of two or more related languages, belonging to the same language family, by means of the comparative method. A language reconstructed in this way is often referred to as a proto-language (the common ancestor of all the languages in a given family); examples include Proto-Indo-European and Proto-Dravidian.

Texts discussing linguistic reconstruction commonly preface reconstructed forms with an asterisk (*) to distinguish them from attested forms.

An attested word from which a root in the proto-language is reconstructed is a reflex. More generally, a reflex is the known derivative of an earlier form, which may be either attested or reconstructed. Reflexes of the same source are cognates.

Methods

First, languages that are thought to have arisen from a common proto-language must meet certain criteria in order to be grouped together; this is a process called subgrouping. Since this grouping is based purely on linguistics, manuscripts and other historical documentation should be analyzed to accomplish this step. However, the assumption that the delineations of linguistics always align with those of culture and ethnicity must not be made. One of the criteria is that the grouped languages usually exemplify shared innovation. This means that the languages must show common changes made throughout history. In addition, most grouped languages have shared retention. This is similar to the first criterion, but instead of changes, they are features that have stayed the same in both languages.[1]

Because linguistics, as in other scientific areas, seeks to reflect simplicity, an important principle in the linguistic reconstruction process is to generate the least possible number of phonemes that correspond to available data. This principle is again reflected when choosing the sound quality of phonemes, as the one which results in the fewest changes (with respect to the data) is preferred.[2]

Comparative Reconstruction makes use of two rather general principles: The Majority Principle and the Most Natural Development Principle.[3] The Majority Principle is the observation that if a cognate set displays a certain pattern (such as a repeating letter in specific positions within a word), it is likely that this pattern was retained from its mother language. The Most Natural Development Principle states that some alterations in languages, diachronically speaking, are more common than others. There are four key tendencies:

- The final vowel in a word may be omitted.

- Voiceless sounds, often between vowels, become voiced.

- Phonetic stops become fricatives.

- Consonants become voiceless at the end of words.

Sound construction

The Majority Principle is applied in identifying the most likely pronunciation of the predicted etymon (the original word from which the cognates originated). Since the Most Natural Development Principle describes the general directions in which languages appear to change, one can seek these indicators out. For example, from the word 'cantar' (Spanish) and 'chanter' (French) one can argue that, because phonetic stops generally become fricatives, the cognate with the stop [k] is older than the cognate with the fricative [ʃ], the former is most likely to more closely resemble the original pronunciation.[3]

See also

References

- Yule, George (2 January 2020). The Study of Language 2019. New York, NY: Cambridge University Printing House. ISBN 9781108499453.

Sources

- Anthony Fox, Linguistic Reconstruction: An Introduction to Theory and Method (Oxford University Press, 1995) ISBN 0-19-870001-6.

- George Yule, The Study of Language (7th Ed.) (Cambridge University Press, 2019) ISBN 978-1-108-73070-9.

- Henry M. Hoenigswald, Language Change and Linguistic Reconstruction (University of Chicago Press, 1960) ISBN 0-226-34741-9.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Linguistic_reconstruction

| Discipline | Linguistics |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Publication details | |

| History | 1995-present |

| Publisher | The Association for the Study of Language In Prehistory (ASLIP) (United States) |

| Frequency | Annual |

| Standard abbreviations | |

| ISO 4 | Mother Tongue |

| Links | |

Mother Tongue is an annual academic journal published by the Association for the Study of Language in Prehistory (ASLIP) that has been published since 1995.[1] Its goal is to encourage international and interdisciplinary information sharing, discussion, and debate among geneticists, paleoanthropologists, archaeologists, and historical linguists on questions relating to the origin of language and ancestral human spoken languages. This includes, but is not limited to, discussion of linguistic macrofamily hypotheses.

See also

References

External links

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mother_Tongue_(journal)

| Ural-Altaic | |

|---|---|

| (obsolete as a genealogical proposal) | |

| Geographic distribution | Eurasia |

| Linguistic classification | convergence zone |

| Subdivisions | |

| Glottolog | None |

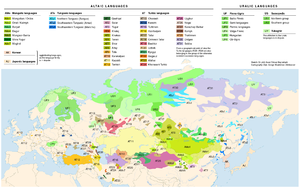

Distribution of Uralic, Altaic, and Yukaghir languages | |

Ural-Altaic, Uralo-Altaic or Uraltaic is a linguistic convergence zone and former language-family proposal uniting the Uralic and the Altaic (in the narrow sense) languages. It is generally now agreed that even the Altaic languages do not share a common descent: the similarities among Turkic, Mongolic and Tungusic are better explained by diffusion and borrowing.[1][2][3][4] Just as Altaic, internal structure of the Uralic family also has been debated since the family was first proposed.[5] Doubts about the validity of most or all of the proposed higher-order Uralic branchings (grouping the nine undisputed families) are becoming more common.[6][7][8] The term continues to be used for the central Eurasian typological, grammatical and lexical convergence zone.[9]

Indeed, "Ural-Altaic" may be preferable to "Altaic" in this sense. For example, J. Janhunen states that "speaking of 'Altaic' instead of 'Ural-Altaic' is a misconception, for there are no areal or typological features that are specific to 'Altaic' without Uralic."[10] Originally suggested in the 18th century, the genealogical and racial hypotheses remained debated into the mid-20th century, often with disagreements exacerbated by pan-nationalist agendas.[11]

It had many proponents in Britain.[12] Since the 1960s, the proposed language family has been widely rejected.[13][14][15][16] A relationship between the Altaic, Indo-European and Uralic families was revived in the context of the Nostratic hypothesis, which was popular for a time,[17] with for example Allan Bomhard treating Uralic, Altaic and Indo-European as coordinate branches.[18] However, Nostratic too is now rejected.[10]

History as a hypothesized language family

The concept of a Ural-Altaic ethnic and language family goes back to the linguistic theories of Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz; in his opinion there was no better method for specifying the relationship and origin of the various peoples of the Earth, than the comparison of their languages. In his Brevis designatio meditationum de originibus gentium ductis potissimum ex indicio linguarum,[19] written in 1710, he originates every human language from one common ancestor language. Over time, this ancestor language split into two families; the Japhetic and the Aramaic. The Japhetic family split even further, into Scythian and Celtic branches. The members of the Scythian family were: the Greek language, the family of Sarmato-Slavic languages (Russian, Polish, Czech, Dalmatian, Bulgar, Slovene, Avar and Khazar), the family of Turkic languages (Turkish, Cuman, Kalmyk and Mongolian), the family of Finno-Ugric languages (Finnish, Saami, Hungarian, Estonian, Liv and Samoyed). Although his theory and grouping were far from perfect, they had a considerable effect on the development of linguistic research, especially in German-speaking countries.

In his book An historico-geographical description of the north and east parts of Europe and Asia,[20] published in 1730, Philip Johan von Strahlenberg, Swedish prisoner-of-war and explorer of Siberia, who accompanied Daniel Gottlieb Messerschmidt on his expeditions, described Finno-Ugric, Turkic, Samoyedic, Mongolic, Tungusic and Caucasian peoples as sharing linguistic and cultural commonalities. 20th century scholarship has on several occasions incorrectly credited him with proposing a Ural-Altaic language family, though he does not claim linguistic affinity between any of the six groups.[21][note 1]

Danish philologist Rasmus Christian Rask described what he called "Scythian" languages in 1834, which included Finno-Ugric, Turkic, Samoyedic, Eskimo, Caucasian, Basque and others.

The Ural-Altaic hypothesis was elaborated at least as early as 1836 by W. Schott[22] and in 1838 by F. J. Wiedemann.[23]

The "Altaic" hypothesis, as mentioned by Finnish linguist and explorer Matthias Castrén[24][25] by 1844, included the Finno-Ugric and Samoyedic, grouped as "Chudic", and Turkic, Mongolic, and Tungusic, grouped as "Tataric". Subsequently, in the latter half of the 19th century, Turkic, Mongolic, and Tungusic came to be referred to as Altaic languages, whereas Finno-Ugric and Samoyedic were called Uralic. The similarities between these two families led to their retention in a common grouping, named Ural–Altaic.

Friedrich Max Müller, the German Orientalist and philologist, published and proposed a new grouping of the non-Aryan and non-Semitic Asian languages in 1855. In his work The Languages of the Seat of War in the East, he called these languages "Turanian". Müller divided this group into two subgroups, the Southern Division, and the Northern Division.[26] In the long run, his evolutionist theory about languages' structural development, tying growing grammatical refinement to socio-economic development, and grouping languages into 'antediluvian', 'familial', 'nomadic', and 'political' developmental stages,[27] proved unsound, but his Northern Division was renamed and re-classed as the "Ural-Altaic languages".

Between the 1850s and 1870s, there were efforts by Frederick Roehrig to including some Native American languages in a "Turanian" or "Ural-Altaic" family, and between the 1870s and 1890s, there was speculation about links with Basque.[28]

In Hungary, where the national language is Uralic but with heavy historical Turkic influence -- a fact which by itself spurred the popularity of the "Ural-Altaic" hypothesis -- the idea of the Ural–Altaic relationship remained widely implicitly accepted in the late 19th and the mid-20th century, though more out of pan-nationalist than linguistic reasons, and without much detailed research carried out.[clarification needed] Elsewhere the notion had sooner fallen into discredit, with Ural–Altaic supporters elsewhere such as the Finnish Altaicist Martti Räsänen being in the minority.[29] The contradiction between Hungarian linguists' convictions and the lack of clear evidence eventually provided motivation for scholars such as Aurélien Sauvageot and Denis Sinor to carry out more detailed investigation of the hypothesis, which so far has failed to yield generally accepted results. Nicholas Poppe in his article The Uralo-Altaic Theory in the Light of the Soviet Linguistics (1940) also attempted to refute Castrén's views by showing that the common agglutinating features may have arisen independently.[30]

Beginning in the 1960s, the hypothesis came to be seen even more controversial, due to the Altaic family itself also falling out universal acceptance. Today, the hypothesis that Uralic and Altaic are related more closely to one another than to any other family has almost no adherents.[31] In his Altaic Etymological Dictionary, co-authored with Anna V. Dybo and Oleg A. Mudrak, Sergei Starostin characterized the Ural–Altaic hypothesis as "an idea now completely discarded".[31] There are, however, a number of hypotheses that propose a larger macrofamily including Uralic, Altaic and other families. None of these hypotheses has widespread support. In Starostin's sketch of a "Borean" super-phylum, he puts Uralic and Altaic as daughters of an ancestral language of c. 9,000 years ago from which the Dravidian languages and the Paleo-Siberian languages, including Eskimo–Aleut, are also descended. He posits that this ancestral language, together with Indo-European and Kartvelian, descends from a "Eurasiatic" protolanguage some 12,000 years ago, which in turn would be descended from a "Borean" protolanguage via Nostratic.[32]

In the 1980s, Russian linguist N. D. Andreev (Nikolai Dmitrievich Andreev) proposed a "Boreal languages" hypothesis linking the Indo-European, Uralic, and Altaic (including Korean in his later papers) language families. Andreev also proposed 203 lexical roots for his hypothesized Boreal macrofamily. After Andreev's death in 1997, the Boreal hypothesis was further expanded by Sorin Paliga (2003, 2007).[33][34]

Angela Marcantonio (2002) argues that there is no sufficient evidence for a Finno-Ugric or Uralic group connecting the Finno-Permic and Ugric languages, and suggests that they are no more closely related to each other than either is to Turkic, thereby positing a grouping very similar to Ural–Altaic or indeed to Castrén's original Altaic proposal. This thesis has been criticized by mainstream Uralic scholars.[35][36][37]

Typology

There is general agreement on several typological similarities being widely found among the languages considered under Ural–Altaic:[38]

- head-final and subject–object–verb word order

- in most of the languages, vowel harmony

- morphology that is predominantly agglutinative and suffixing

- zero copula

- non-finite clauses

- lack of grammatical gender

- lack of consonant clusters in word-initial position

- having a separate verb for existential clause which is different from ordinary possession verbs like "to have"

Such similarities do not constitute sufficient evidence of genetic relationship all on their own, as other explanations are possible. Juha Janhunen has argued that although Ural–Altaic is to be rejected as a genealogical relationship, it remains a viable concept as a well-defined language area, which in his view has formed through the historical interaction and convergence of four core language families (Uralic, Turkic, Mongolic and Tungusic), and their influence on the more marginal Korean and Japonic.[39]

Contrasting views on the typological situation have been presented by other researchers. Michael Fortescue has connected Uralic instead as a part of an Uralo-Siberian typological area (comprising Uralic, Yukaghir, Chukotko-Kamchatkan and Eskimo–Aleut), contrasting with a more narrowly defined Altaic typological area;[40] while Anderson has outlined a specifically Siberian language area, including within Uralic only the Ob-Ugric and Samoyedic groups; within Altaic most of the Tungusic family as well as Siberian Turkic and Buryat (Mongolic); as well as Yukaghir, Chukotko-Kamchatkan, Eskimo–Aleut, Nivkh, and Yeniseian.[41]

Relationship between Uralic and Altaic

The Altaic language family was generally accepted by linguists from the late 19th century up to the 1960s, but since then has been in dispute. For simplicity's sake, the following discussion assumes the validity of the Altaic language family.

Two senses should be distinguished in which Uralic and Altaic might be related.

- Do Uralic and Altaic have a demonstrable genetic relationship?

- If they do have a demonstrable genetic relationship, do they form a valid linguistic taxon? For example, Germanic and Iranian have a genetic relationship via Proto-Indo-European, but they do not form a valid taxon within the Indo-European language family, whereas in contrast Iranian and Indo-Aryan do via Indo-Iranian, a daughter language of Proto-Indo-European that subsequently calved into Indo-Aryan and Iranian.

In other words, showing a genetic relationship does not suffice to establish a language family, such as the proposed Ural–Altaic family; it is also necessary to consider whether other languages from outside the proposed family might not be at least as closely related to the languages in that family as the latter are to each other. This distinction is often overlooked but is fundamental to the genetic classification of languages.[42] Some linguists indeed maintain that Uralic and Altaic are related through a larger family, such as Eurasiatic or Nostratic, within which Uralic and Altaic are no more closely related to each other than either is to any other member of the proposed family, for instance than Uralic or Altaic is to Indo-European (for example Greenberg).[43]

To demonstrate the existence of a language family, it is necessary to find cognate words that trace back to a common proto-language. Shared vocabulary alone does not show a relationship, as it may be loaned from one language to another or through the language of a third party.

There are shared words between, for example, Turkic and Ugric languages, or Tungusic and Samoyedic languages, which are explainable by borrowing. However, it has been difficult to find Ural–Altaic words shared across all involved language families. Such words should be found in all branches of the Uralic and Altaic trees and should follow regular sound changes from the proto-language to known modern languages, and regular sound changes from Proto-Ural–Altaic to give Proto-Uralic and Proto-Altaic words should be found to demonstrate the existence of a Ural–Altaic vocabulary. Instead, candidates for Ural–Altaic cognate sets can typically be supported by only one of the Altaic subfamilies.[44] In contrast, about 200 Proto-Uralic word roots are known and universally accepted, and for the proto-languages of the Altaic subfamilies and the larger main groups of Uralic, on the order of 1000–2000 words can be recovered.

Some[who?] linguists point out strong similarities in the personal pronouns of Uralic and Altaic languages, although the similarities also exist with the Indo-European pronouns as well.

The basic numerals, unlike those among the Indo-European languages (compare Proto-Indo-European numerals), are particularly divergent between all three core Altaic families and Uralic, and to a lesser extent even within Uralic.[45]

| Numeral | Uralic | Turkic | Mongolic | Tungusic | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Finnish | Hungarian | Tundra Nenets | Old Turkic | Classical Mongolian | Proto-Tungusic | |

| 1 | yksi | egy | ŋob | bir | nigen | *emün |

| 2 | kaksi | kettő/két | śiďa | eki | qoyar | *džör |

| 3 | kolme | három | ńax°r | üs | ɣurban | *ilam |

| 4 | neljä | négy | ťet° | tört | dörben | *dügün |

| 5 | viisi | öt | səmp°ľaŋk° | baš | tabun | *tuńga |

| 6 | kuusi | hat | mət°ʔ | eltı | ǰirɣuɣan | *ńöŋün |

| 7 | seitsemän | hét | śīʔw° | jeti | doluɣan | *nadan |

| 8 | kahdeksan | nyolc | śid°nťet° | säkiz | naiman | *džapkun |

| 9 | yhdeksän | kilenc | xasuyu" | toquz | yisün | *xüyägün |

| 10 | kymmenen | tíz | yūʔ | on | arban | *džuvan |

One alleged Ural-Altaic similarity among this data are the Hungarian (három) and Mongolian (ɣurban) numerals for '3'. According to Róna-Tas (1983),[46] elevating this similarity to a hypothesis of common origin would still require several ancillary hypotheses:

- that this Finno-Ugric lexeme, and not the incompatible Samoyedic lexeme, is the original Uralic numeral;

- that this Mongolic lexeme, and not the incompatible Turkic and Tungusic lexemes, is the original Altaic numeral;

- that the Hungarian form with -r-, and not the -l- seen in cognates such as in Finnish kolme, is more original;

- that -m in the Hungarian form is originally a suffix, since -bVn, found also in other Mongolian numerals, is also a suffix and not an original part of the word root;

- that the voiced spirant ɣ- in Mongolian can correspond to the voiceless stop *k- in Finno-Ugric (known to be the source of Hungarian h-).

Sound correspondences

The following consonant correspondences between Uralic and Altaic are asserted by Poppe (1983):[47]

- Word-initial bilabial stop: Uralic *p- = Altaic *p- (> Turkic and Mongolic *h-)

- Sibilants: Uralic *s, *š, *ś = Altaic *s

- Nasals: Uralic *n, *ń, *ŋ = Altaic *n, *ń, *ŋ (in Turkic word-initial *n-, *ń- > *j-; in Mongolic *ń(V) > *n(i))

- Liquids: Uralic *-l-, *-r- = Altaic *-l-, *r-[note 2]

As a convergence zone

Regardless of a possible common origin or lack thereof, Uralic-Altaic languages can be spoken of as a convergence zone. Although it has not yet been possible to demonstrate a genetic relationship or a significant amount of common vocabulary between the languages other than loanwords, according to the linguist Juha Jahunen, the languages must have had a common linguistic homeland. The Turkic, Mongolic and Tungusic languages have been spoken in the Manchurian region, and there is little chance that a similar structural typology of Uralic languages could have emerged without close contact with them.[48][49][50] The languages of Turkish and Finnish have many similar structures, such as vowel harmony and agglutination.[51]

Similarly, according to Janhunen, the common typology of the Altaic languages can be inferred as a result of mutual contacts in the past, perhaps from a few thousand years ago.[52]

See also

Notes

- Treated only word-medially.

References

- Janhunen 2009: 62.

Bibliography

- Greenberg, Joseph H. (2000). Indo-European and Its Closest Relatives: The Eurasiatic Language Family, Volume 1: Grammar. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Greenberg, Joseph H. (2005). Genetic Linguistics: Essays on Theory and Method, edited by William Croft. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Marcantonio, Angela (2002). The Uralic Language Family: Facts, Myths and Statistics. Publications of the Philological Society. Vol. 35. Oxford – Boston: Blackwell.

- Ponaryadov, V. V. (2011). A tentative reconstruction of Proto-Uralo-Mongolian. Syktyvkar. 44 p. (Scientific Reports / Komi Science Center of the Ural Division of the Russian Academy of Sciences; Issue 510).

- Shirokogoroff, S. M. (1931). Ethnological and Linguistical Aspects of the Ural–Altaic Hypothesis. Peiping, China: The Commercial Press.

- Sinor, Denis (1988). "The Problem of the Ural-Altaic relationship". In Sinor, Denis (ed.). The Uralic Languages: Description, History and Modern Influences. Leiden: Brill. pp. 706–741.

- Starostin, Sergei A., Anna V. Dybo, and Oleg A. Mudrak. (2003). Etymological Dictionary of the Altaic Languages. Brill Academic Publishers. ISBN 90-04-13153-1.

- Vago, R. M. (1972). Abstract Vowel Harmony Systems in Uralic and Altaic Languages. Bloomington: Indiana University Linguistics Club.

External links

- Review of Marcantonio (2002) by Johanna Laasko

- Keane, Augustus Henry (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 27 (11th ed.). pp. 784–786. This reflects the contemporary transitional state of understanding of the relationships among the languages.

- Whitney, William Dwight; Rhyn, G. A. F. Van (1879). . The American Cyclopædia.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ural-Altaic_languages

| Austric | |

|---|---|

| (proposed) | |

| Geographic distribution | Southeast Asia, Pacific Islands, South Asia, East Asia, Madagascar |

| Linguistic classification | Proposed language family |

| Subdivisions |

|

| Glottolog | None |

| |

The Austric languages are a proposed language family that includes the Austronesian languages spoken in Taiwan, Maritime Southeast Asia, the Pacific Islands, and Madagascar, as well as the Austroasiatic languages spoken in Mainland Southeast Asia and South Asia. A genetic relationship between these language families is seen as plausible by some scholars, but remains unproven.[1][2]

Additionally, the Kra–Dai languages and Hmong–Mien languages are included by some linguists, and even Japanese was speculated to be Austric in an early version of the hypothesis by Paul K. Benedict.[3]

History

The Austric macrofamily was first proposed by the German missionary Wilhelm Schmidt in 1906. He showed phonological, morphological, and lexical evidence to support the existence of an Austric phylum consisting of Austroasiatic and Austronesian.[4][a] Schmidt's proposal had a mixed reception among scholars of Southeast Asian languages, and received only little scholarly attention in the following decades.[5]

Research interest into Austric resurged in the late 20th century,[6] culminating in a series of articles by La Vaughn H. Hayes who presented a corpus of Proto-Austric vocabulary together with a reconstruction of Proto-Austric phonology,[7] and by Lawrence Reid, focussing on morphological evidence.[8]

Evidence

Reid (2005) lists the following pairs as "probable" cognates between Proto-Austroasiatic and Proto-Austronesian.[9]

| Gloss | ashes | dog | snake | belly | eye | father | mother | rotten | buy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proto-Austroasiatic | *qabuh | *cu(q) | *[su](l̩)aR | *taʔal/*tiʔal | *mə(n)ta(q) | *(qa)ma(ma) | *(na)na | *ɣok | *pə[l̩]i |

| Proto-Austronesian | *qabu | *asu | *SulaR | *tiaN | *maCa | *t-ama | *t-ina | *ma-buRuk | *beli |

Among the morphological evidence, he compares reconstructed affixes such as the following, and notes that shared infixes are less likely to be borrowed (for a further discussion of infixes in Southeast Asian languages, see also Barlow 2022[10]).[11]

- prefix *pa- 'causative' (Proto-Austroasiatic, Proto-Austronesian)

- infix *-um- 'agentive' (Proto-Austroasiatic, Proto-Austronesian)

- infix *-in- 'instrumental' (Proto-Austroasiatic), 'nominalizer' (Proto-Austronesian)

Below are 10 selected Austric lexical comparisons by Diffloth (1994), as cited in Sidwell & Reid (2021):[12][13]

| Gloss | Proto-Austroasiatic | Proto-Austronesian |

|---|---|---|

| ‘fish’ | *ʔaka̰ːʔ | *Sikan |

| ‘dog’ | *ʔac(ṵə)ʔ | *asu |

| ‘wood’ | *kəɟh(uː)ʔ | *kaSi |

| ‘eye’ | *ma̰t | *maCa |

| ‘bone’ | *ɟlʔaːŋ | *CuqelaN |

| ‘hair’ | *s(ɔ)k | *bukeS |

| ‘bamboo rat’ | Khmu dəkən | Malay dəkan |

| ‘molar’ | Khmer thkìəm | Malay gərham |

| ‘left’ | p-Monic *ɟwiːʔ | *ka-wiʀi |

| ‘ashes’ | Stieng *buh | *qabu |

Extended proposals

The first extension to Austric was first proposed Wilhelm Schmidt himself, who speculated about including Japanese within Austric, mainly because of assumed similarities between Japanese and the Austronesian languages.[14] While the proposal about a link between Austronesian and Japanese still enjoys some following as a separate hypothesis, the inclusion of Japanese was not adopted by later proponents of Austric.

In 1942, Paul K. Benedict provisionally accepted the Austric hypothesis and extended it to include the Kra–Dai (Thai–Kadai) languages as an immediate sister branch to Austronesian, and further speculated on the possibility to include the Hmong–Mien (Miao–Yao) languages as well.[15] However, he later abandoned the Austric proposal in favor of an extended version of the Austro-Tai hypothesis.[16]

Sergei Starostin adopted Benedict's extended 1942 version of Austric (i.e. including Kra–Dai and Hmong–Mien) within the framework of his larger Dené–Daic proposal, with Austric as a coordinate branch to Dené–Caucasian, as shown in the tree below.[17]

| Dene-Daic |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Another long-range proposal for wider connections of Austric was brought forward by John Bengtson, who grouped Nihali and Ainu together with Austroasiatic, Austronesian, Hmong–Mien, and Kra–Dai in a "Greater Austric" family.[18]

Reception

In the second half of the last century, Paul K. Benedict raised a vocal critique of the Austric proposal, eventually calling it an 'extinct' proto-language.[19][16]

Hayes' lexical comparisons, which were presented as supporting evidence for Austric between 1992 and 2001, were criticized for the greater part as methodologically unsound by several reviewers.[20][21] Robert Blust, a leading scholar in the field of Austronesian comparative linguistics, pointed out "the radical disjunction of morphological and lexical evidence" which characterizes the Austric proposal; while he accepts the morphological correspondences between Austronesian and Austroasiatic as possible evidence for a remote genetic relationship, he considers the lexical evidence unconvincing.[22]

A 2015 analysis using the Automated Similarity Judgment Program (ASJP) did not support the Austric hypothesis. In this analysis, the supposed "core" components of Austric were assigned to two separate, unrelated clades: Austro-Tai and Austroasiatic-Japonic.[23] Note however that ASJP is not widely accepted among historical linguists as an adequate method to establish or evaluate relationships between language families.[24]

Distributions

Distribution of Austroasiatic languages

Distribution of Austronesian languages

Distribution of Kra–Dai languages

Distribution of Hmong–Mien languages

See also

- East Asian languages

- Austro-Tai languages

- Sino-Austronesian languages

- Mainland Southeast Asia linguistic area

- Classification of Southeast Asian languages

Notes

- The terms "Austroasiatic" and "Austronesian" were in fact both coined by Schmidt. The previous common designations "Mon-Khmer" and "Malayo-Polynesian" are still in use, but each with a scope that is more limited than "Austroasiatic" and "Austronesian".

References

- Cf. comments by Adelaar, Blust and Campbell in Holman (2011).

Works cited

- Benedict, Paul K. (1942). "Thai, Kadai, and Indonesian: A New Alignment in Southeastern Asia". American Anthropologist. 4 (44): 576–601. doi:10.1525/aa.1942.44.4.02a00040.

- ——— (1976). "Austro-Thai and Austroasiatic". In Jenner, Philip N.; Thompson, Laurence C.; Starosta, Stanley (eds.). Austroasiatic Studies, Part I. Oceanic Linguistics Special Publications. Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press. pp. 1–36. JSTOR 20019153.

- ——— (1991). "Austric: An 'Extinct' Proto-language". In Davidson, Jeremy H. C. S. (ed.). Austroasiatic Languages: Essays in Honour of H. L. Shorto. London: School of Oriental and African Studies. pp. 7–11.

- Blust, Robert (2013). The Austronesian Languages (revised ed.). Australian National University. hdl:1885/10191. ISBN 978-1-922185-07-5.

- Diffloth, Gerard (1990). "What Happened to Austric?" (PDF). Mon–Khmer Studies. 16–17: 1–9.

- ——— (1994). "The lexical evidence for Austric so far". Oceanic Linguistics. 33 (2): 309–321. doi:10.2307/3623131. JSTOR 3623131.

- van Driem, George (2001). Languages of the Himalayas. Vol. 1. Leiden: BRILL. ISBN 9004120629.

- ——— (2005). "Sino-Austronesian vs. Sino-Caucasian, Sino-Bodic vs. Sino-Tibetan, and Tibeto-Burman as default theory" (PDF). In Yadava, Yogendra P. (ed.). Contemporary Issues in Nepalese Linguistics. Linguistic Society of Nepal. pp. 285–338. ISBN 978-99946-57-69-8.

- Hayes, La Vaughn H. (1992). "On the Track of Austric, Part I: Introduction" (PDF). Mon–Khmer Studies. 21: 143–77.

- ——— (1997). "On the Track of Austric, Part II: Consonant Mutation in Early Austroasiatic" (PDF). Mon–Khmer Studies. 27: 13–41.

- ——— (1999). "On the Track of Austric, Part III: Basic Vocabulary Correspondence" (PDF). Mon–Khmer Studies. 29: 1–34.

- ——— (2000). "The Austric Denti-alveolar Sibilants". Mother Tongue. 5: 1–12.

- ——— (2001). "On the Origin of Affricates in Austric". Mother Tongue. 6: 95–117.

- Holman, Eric W. (2011). "Automated Dating of the World's Language Families Based on Lexical Similarity" (PDF). Current Anthropology. 52 (6): 841–875. doi:10.1086/662127. hdl:2066/94255. S2CID 60838510.

- Jäger, Gerhard (2015). "Support for linguistic macrofamilies from weighted sequence alignment". PNAS. 112 (41): 12752–12757. Bibcode:2015PNAS..11212752J. doi:10.1073/pnas.1500331112. PMC 4611657. PMID 26403857.

- Reid, Lawrence A. (1994). "Morphological evidence for Austric" (PDF). Oceanic Linguistics. 33 (2): 323–344. doi:10.2307/3623132. hdl:10125/32987. JSTOR 3623132.

- ——— (1999). "New linguistic evidence for the Austric hypothesis". In Zeitoun, Elizabeth; Li, Paul Jen-kuei (eds.). Selected Papers from the Eighth International Conference on Austronesian Linguistics. Taipei: Academia Sinica. pp. 5–30.

- ——— (2005). "The current status of Austric: A review and evaluation of the lexical and morphosyntactic evidence". In Sagart, Laurent; Blench, Roger; Sanchez-Mazas, Alicia (eds.). The peopling of East Asia: putting together archaeology, linguistics and genetics. London: Routledge Curzon. hdl:10125/33009.

- ——— (2009). "Austric Hypothesis". In Brown, Keith; Ogilvie, Sarah (eds.). Concise Encyclopaedia of Languages of the World. Oxford: Elsevier. pp. 92–94.

- Schmidt, Wilhelm (1906). "Die Mon–Khmer-Völker, ein Bindeglied zwischen Völkern Zentralasiens und Austronesiens ('[The Mon–Khmer Peoples, a Link between the Peoples of Central Asia and Austronesia')". Archiv für Anthropologie. 5: 59–109.

- ——— (1930). "Die Beziehungen der austrischen Sprachen zum Japanischen ('The connections of the Austric languages to Japanese')". Wiener Beitrag zur Kulturgeschichte und Linguistik. 1: 239–51..

- Shorto, H. L. (1976). "In Defense of Austric". Computational Analyses of Asian and African Languages. 6: 95–104.

- Solnit, David B. (1992). "Japanese/Austro-Tai By Paul K. Benedict (review)". Language. 68 (1): 188–196. doi:10.1353/lan.1992.0061. ISSN 1535-0665. S2CID 141811621.

Further reading

- Blazhek, Vaclav. 2000. Comments on Hayes "The Austric Denti-alveolar Sibilants". Mother Tongue V:15-17.

- Blust, Robert. 1996. Beyond the Austronesian homeland: The Austric hypothesis and its implications for archaeology. In: Prehistoric Settlement of the Pacific, ed. by Ward H.Goodenough, ISBN 978-0-87169-865-0 DIANE Publishing Co, Collingdale PA, 1996, pp. 117–137. (Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 86.5. (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society).

- Blust, Robert. 2000. Comments on Hayes, "The Austric Denti-alveolar Sibilants". Mother Tongue V:19-21.

- Fleming, Hal. 2000. LaVaughn Hayes and Robert Blust Discuss Austric. Mother Tongue V:29-32.

- Hayes, La Vaughn H. 2000. Response to Blazhek's Comments. Mother Tongue V:33-4.

- Hayes, La Vaughn H. 2000. Response to Blust's Comments. Mother Tongue V:35-7.

- Hayes, La Vaughn H. 2000. Response to Fleming's Comments. Mother Tongue V:39-40.

- Hayes, La Vaughn H. 2001. Response to Sidwell. Mother Tongue VI:123-7.

- Larish, Michael D. 2006. Possible Proto-Asian Archaic Residue and the Statigraphy of Diffusional Cumulation in Austro-Asian Languages. Paper presented at the Tenth International Conference on Austronesian Linguistics, 17–20 January 2006, Puerto Princesa City, Palawan, Philippines.

- Reid, Lawrence A. 1996. The current state of linguistic research on the relatedness of the language families of East and Southeast Asia. In: Ian C. Glover and Peter Bellwood, editorial co-ordinators, Indo-Pacific Prehistory: The Chiang Mai Papers, Volume 2, pp . 87-91. Bulletin of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association 15. Canberra: Australian National University.

- Sidwell, Paul. 2001. Comments on La Vaughn H. Hayes' "On the Origin of Affricates in Austric". Mother Tongue VI:119-121.

- Van Driem, George. 2000. Four Austric Theories. Mother Tongue V:23-27.

External links

- Glossary of purported lexical links among Austronesian and Austroasiatic languages

- Austronesian Basic Vocabulary Database: Austronesian, Tai–Kadai, Hmong–Mien, Austro-Asiatic word lists

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Austric_languages

| Nostratic | |

|---|---|

| (controversial) | |

| Geographic distribution | Europe, Asia except for the southeast, North and Northeast Africa, the Arctic |

| Linguistic classification | Hypothetical macrofamily |

| Subdivisions |

|

| Glottolog | None |

Nostratic is a hypothetical macrofamily, which includes many of the indigenous language families of Eurasia, although its exact composition and structure vary among proponents. It typically comprises Kartvelian, Indo-European and Uralic languages; some languages from the similarly controversial Altaic family; the Afroasiatic languages; as well as the Dravidian languages (sometimes also Elamo-Dravidian).

The hypothetical ancestral language of the Nostratic family is called Proto-Nostratic.[1] According to Allan R. Bomhard, Proto-Nostratic would have been spoken between 15,000 and 12,000 BCE, in the Epipaleolithic period, close to the end of the last glacial period, perhaps in or near the Fertile Crescent.[2][3]

The Nostratic hypothesis originates with Holger Pedersen in the early 20th century. The name "Nostratic" is due to Pedersen (1903), derived from the Latin nostrates "fellow countrymen". The hypothesis was significantly expanded in the 1960s by Soviet linguists, notably Vladislav Illich-Svitych and Aharon Dolgopolsky, termed the "Moscovite school" by Allan Bomhard (2008, 2011, and 2014), and it has received renewed attention in English-speaking academia since the 1990s.

The hypothesis is controversial and has varying degrees of acceptance amongst linguists worldwide with most rejecting Nostratic and many other macrofamily hypotheses.[4] In Russia, it is endorsed by a minority of linguists, such as Vladimir Dybo, but is not a generally accepted hypothesis.[citation needed] Some linguists take an agnostic view.[5][6][7][8] Eurasiatic, a similar grouping, was proposed by Joseph Greenberg (2000) and endorsed by Merritt Ruhlen: it is taken as a subfamily of Nostratic by Bomhard (2008).

History of research

Origin of the Nostratic hypothesis

The last quarter of the 19th century saw various linguists putting forward proposals linking the Indo-European languages to other language families, such as Finno-Ugric and Altaic.[9]

These proposals were taken much further in 1903 when Holger Pedersen proposed "Nostratic", a common ancestor for the Indo-European, Finno-Ugric, Samoyed, Turkish, Mongolian, Manchu, Yukaghir, Eskimo, Semitic, and Hamitic languages, with the door left open to the eventual inclusion of others.

The name Nostratic derives from the Latin word nostrās, meaning 'our fellow-countryman' (plural: nostrates) and has been defined, since Pedersen, as consisting of those language families that are related to Indo-European.[10] Merritt Ruhlen notes that this definition is not properly taxonomic but amorphous, since there are broader and narrower degrees of relatedness, and moreover, some linguists who broadly accept the concept (such as Greenberg and Ruhlen himself) have criticised the name as reflecting the ethnocentrism frequent among Europeans at the time.[11] Martin Bernal has described the term as distasteful because it implies that speakers of other language families are excluded from academic discussion.[12] Even so, the concept arguably transcends ethnocentric associations. (Indeed, Pedersen's older contemporary Henry Sweet attributed some of the resistance by Indo-European specialists to hypotheses of wider genetic relationships as "prejudice against dethroning [Indo-European] from its proud isolation and affiliating it to the languages of yellow races".)[13] Proposed alternative names such as Mitian, formed from the characteristic Nostratic first- and second-person pronouns mi 'I' and ti 'you' (exactly 'thee'),[14] have not attained the same currency.

An early supporter was the French linguist Albert Cuny—better known for his role in the development of the laryngeal theory[15]—who published his Recherches sur le vocalisme, le consonantisme et la formation des racines en « nostratique », ancêtre de l'indo-européen et du chamito-sémitique ('Researches on the Vocalism, Consonantism, and Formation of Roots in "Nostratic", Ancestor of Indo-European and Hamito-Semitic') in 1943. Although Cuny enjoyed a high reputation as a linguist, the work was coldly received.

Moscow School of Comparative Linguistics

While Pedersen's Nostratic hypothesis did not make much headway in the West, it became quite popular in what was then the Soviet Union. Working independently at first, Vladislav Illich-Svitych and Aharon Dolgopolsky elaborated the first version of the contemporary form of the hypothesis during the 1960s. They expanded it to include additional language families. Illich-Svitych also prepared the first dictionary of the hypothetical language.[16]

A principal source for the items in Illich-Svitych's dictionary was the earlier work of Alfredo Trombetti (1866–1929), an Italian linguist who had developed a classification scheme for all the world's languages, widely reviled at the time[17] and subsequently ignored by almost all linguists. In Trombetti's time, a widely held view on classifying languages was that similarity in inflections is the surest proof of genetic relationship. In the interim, the view had taken hold that the comparative method—previously used as a means of studying languages already known to be related and without any thought of classification[18]—is the most effective means to establish genetic relationship, eventually hardening into the conviction that it is the only legitimate means to do so. This view was basic to the outlook of the new Nostraticists. Although Illich-Svitych adopted many of Trombetti's etymologies, he sought to validate them by a systematic comparison of the sound systems of the languages concerned.

21st century

The chief events in Nostratic studies in 2008 were the online publication of the latest version of Dolgopolsky's Nostratic Dictionary[19] and the publication of Allan Bomhard's comprehensive treatment of the subject, Reconstructing Proto-Nostratic, in 2 volumes.[20] 2008 also saw the opening of a website, Nostratica, devoted to providing important texts in Nostratic studies online, which is now offline.[21] Also significant was Bomhard's partly critical review of Dolgopolsky's dictionary, in which he argued that only those Nostratic etymologies that are strongest should be included, in contrast to Dolgopolsky's more expansive approach, which includes many etymologies that are possible but not secure.[22]

In early 2014, Allan Bomhard published his latest monograph on Nostratic, A Comprehensive Introduction to Nostratic Comparative Linguistics.[23]

Constituent language families

The language families proposed for inclusion in Nostratic vary, but all Nostraticists agree on a common core of language families, with differences of opinion appearing over the inclusion of additional families.

The three groups universally accepted among Nostraticists are Indo-European, Uralic, and Altaic; the validity of the Altaic family, while itself controversial, is taken for granted by Nostraticists. Nearly all also include the Kartvelian and Dravidian language families.[24]

Following Pedersen, Illich-Svitych, and Dolgopolsky, most advocates of the theory have included Afroasiatic, though criticisms by Joseph Greenberg and others from the late 1980s onward suggested a reassessment of this position.

The Sumerian and Etruscan languages, usually regarded as language isolates, are thought by some to be Nostratic languages as well. Others, however, consider one or both to be members of another macrofamily called Dené–Caucasian. Another notional isolate, the Elamite language, also figures in a number of Nostratic classifications. It is frequently grouped with Dravidian as Elamo-Dravidian.[25][26]

In 1987 Joseph Greenberg proposed a similar macrofamily which he called Eurasiatic.[27] It included the same "Euraltaic" core (Indo-European, Uralic, and Altaic), but excluded some of the above-listed families, most notably Afroasiatic. At about this time Russian Nostraticists, notably Sergei Starostin, constructed a revised version of Nostratic which was slightly broader than Greenberg's grouping but which similarly left out Afroasiatic.

Beginning in the early 2000s, a consensus emerged among proponents of the Nostratic hypothesis. Greenberg basically agreed with the Nostratic concept, though he stressed a deep internal division between its northern 'tier' (his Eurasiatic) and a southern 'tier' (principally Afroasiatic and Dravidian). The American Nostraticist Allan Bomhard considers Eurasiatic a branch of Nostratic alongside other branches: Kartvelian, Afroasiatic, and Elamo-Dravidian. Similarly, Georgiy Starostin (2002) arrives at a tripartite overall grouping: he considers Afroasiatic, Nostratic and Elamite to be roughly equidistant and more closely related to each other than to anything else.[28] Sergei Starostin's school has now re-included Afroasiatic in a broadly defined Nostratic, while reserving the term Eurasiatic to designate the narrower subgrouping which comprises the rest of the macrofamily. Recent proposals thus differ mainly on the precise placement of Kartvelian and Dravidian.

According to Greenberg, Eurasiatic and Amerind form a genetic node, being more closely related to each other than either is to "the other families of the Old World".[29] There are a number of hypotheses incorporating Nostratic into an even broader linguistic 'mega-phylum', sometimes called Borean, which would also include at least the Dené–Caucasian and perhaps the Amerind and Austric superfamilies. The term SCAN has been used for a group that would include Sino-Caucasian, Amerind, and Nostratic.[30]

The following table summarizes the constituent language families of Nostratic, as described by Holger Pedersen, Vladislav Illich-Svitych, Sergei Starostin, Allan Bomhard, and Aharon Dolgopolsky.

| Linguist | Indo-European | Afroasiatic | Uralic | Altaic | Dravidian | Kartvelian | Eskimo-Aleut | Yukaghir | Sumerian | Chukchi-Kamchatkan | Gilyak | Etruscan |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pedersen[31] | ||||||||||||

| Illich-Svitych[32] | ||||||||||||

| Starostin[33] | ||||||||||||

| Bomhard[34] | ||||||||||||

| Dolgopolsky[35] | ||||||||||||

|

Urheimat and differentiation

Allan Bomhard and Colin Renfrew are in broad agreement with the earlier conclusions of Illich-Svitych and Dolgopolsky in seeking the Nostratic Urheimat (original homeland) within the Mesolithic (or Epipaleolithic) in the Fertile Crescent, the stage which directly preceded the Neolithic and was transitional to it.

Looking at the cultural assemblages of this period, two sequences, in particular, stand out as possible archeological correlates of the earliest Nostratians or their immediate precursors. Both hypotheses place Proto-Nostratic within the Fertile Crescent at around the end of the last glacial period.

- The first of these is focused on the Levant. The Kebaran culture (20,000–17,000 BP)[36] not only introduced the microlithic assemblage into the region, it also has African affinity specifically with the Ouchtata retouch technique associated with the microlithic Halfan culture of Egypt (20,000–17,000 BP)[37] The Kebarans in their turn were directly ancestral to the succeeding Natufian culture (10,500–8500 BCE), which has enormous significance for prehistorians as the clearest evidence of hunters and gatherers in actual transition to Neolithic food production. Both cultures extended their influence outside the region into southern Anatolia. For example, in Cilicia the Belbaşı culture (13,000–10,000 BC) shows Kebaran influence, while the Beldibi culture (10,000–8500 BC) shows clear Natufian influence.

- The second possibility as a culture associated with the Nostratic family is the Zarzian (12,400–8500 BC) culture of the Zagros mountains, stretching northwards into Kohistan in the Caucasus and eastwards into Iran. In western Iran, the M'lefatian culture (10,500–9000 BC) was ancestral to the assemblages of Ali Tappah (9000–5000 BC) and Jeitun (6000–4000 BC). Still further east, the Hissar culture has been seen as the Mesolithic precursor to the Keltiminar culture (5500–3500 BC) of the Kyrgyz steppe.

It has been proposed that the broad spectrum revolution[38] of Kent Flannery (1969),[39] associated with microliths, the use of the bow and arrow, and the domestication of the dog, all of which are associated with these cultures, might have been the cultural "motor" that led to their expansion. Certainly, cultures which appeared at Franchthi Cave in the Aegean and Lepenski Vir in the Balkans, and the Murzak-Koba (9100–8000 BC) and Grebenki (8500–7000 BC) cultures of the Ukrainian steppe, all displayed these adaptations.

Bomhard (2008) suggests a differentiation of Proto-Nostratic by 8,000 BCE, the beginning of the Neolithic Revolution in the Levant, over a territory spanning the entire Fertile Crescent and beyond into the Caucasus (Proto-Kartvelian), Egypt and along the Red Sea to the Horn of Africa (Proto-Afroasiatic), the Iranian Plateau (Proto-Elamo-Dravidian) and into Central Asia (Proto-Eurasiatic, to be further subdivided by 5,000 BCE into Proto-Indo-European, Proto-Uralic and Proto-Altaic).

According to some scholarly opinion the Kebaran is derived from the Levantine Upper Palaeolithic in which the microlithic component originated,[40] although microlithic cultures were earlier found in Africa.

Ouchtata retouch is also a characteristic of the Late Ahmarian Upper Palaeolithic culture of the Levant and may not indicate African influence.[40]

Reconstruction of Proto-Nostratic

The following data is taken from Kaiser and Shevoroshkin (1988) and Bengtson (1998) and transcribed into the IPA.

Phonology

The phonemes tabulated below are commonly reconstructed for the Proto-Nostratic language (Kaiser and Shevoroshkin 1988). Allan Bomhard (2008), who relies more heavily on Afroasiatic and Dravidian than on Uralic, as do members of the "Moscow School", reconstructs a different vowel system, with three pairs of vowels represented as: /a/~/ə/, /e/~/i/, /o/~/u/, as well as independent /i/, /o/, and /u/. In the first three pairs of vowels, Bomhard is attempting to specify the subphonemic variation involved, inasmuch as that variation led to some of the vowel gradation (ablaut) and vowel harmony patterning found in various daughter languages.

Consonants

The reconstructed consonants of Nostratic are shown in the table below. Every distinction is supposed to be contrastive by the Nostraticists who reconstruct them.

| Bilabial | Alveolar or dental | Alveolo- palatal |

Post- alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Pharyngeal | Glottal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| central | lateral | ||||||||||

| Plosive | ejective | pʼ[41] | tʼ | kʼ | qʼ | ʔ | |||||

| voiceless | p | t | k | q | |||||||

| voiced | b | d | ɡ | ɢ | |||||||

| Affricate | ejective | tsʼ | tɬʼ | tɕʼ[41] | tʃʼ | ||||||

| voiceless | ts | tɬ | tɕ[41] | tʃ | |||||||

| voiced | dz | dɮ[41] | dʑ[41] | dʒ | |||||||

| Fricative | voiceless | s | ɬ | ɕ[41] | ʃ | χ | ħ | h | |||

| voiced | ʁ | ʕ | |||||||||

| Nasal | m | n | nʲ | ŋ | |||||||

| Trill | r | rʲ[41] | |||||||||

| Approximant | l | lʲ | j | w | |||||||

Vowels

|

|

Front | Central | Back |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | */i/ • */y/[42] | */u/ | |

| Mid | */e/ |

|

*/o/ |

| Near-open | */æ/ |

|

|

| Open | */a/ | ||

Sound correspondences

The following table is compiled from data given by Kaiser and Shevoroshkin (1988) and Starostin.[43] They follow Illich-Svitych's correspondences in which Nostratic voiceless stops give (traditional) PIE voiced ones, and Nostratic glottalized stops give (traditional) PIE voiceless stops,[44] in contradiction with the PIE glottalic theory, which makes traditional PIE voiced stops appear like glottalized ones. To correct this anomaly, linguists such as Manaster Ramer[45] and Bomhard[46] have proposed to correlate Nostratic voiceless and glottalized stops with PIE ones, so this is done in the table.

Because linguists working on Proto-Indo-European, Proto-Uralic, and Proto-Dravidian do not usually use the IPA, the transcriptions used in those fields are also given where the letters differ from the IPA symbols. The IPA symbols are between slashes because this is a phonemic transcription. The exact values of the phoneme "*p₁" in Proto-Afroasiatic and Proto-Dravidian are unknown. "∅" indicates disappearance without a trace. Hyphens indicate different developments at the beginning and in the interior of words; no consonants ever occurred at the ends of word roots. (Starostin's list of affricate and fricative correspondences does not mention Afroasiatic or Dravidian, and Kaiser and Shevoroshkin don't mention these sounds much; hence the holes in the table.)

Note that there are at present several different mutually incompatible reconstructions of Proto-Afroasiatic (see [1] for two recent reconstructions). The one used here has been said to be based too strongly on Proto-Semitic (Yakubovich 1998[47]).

Similarly, the paper by Kaiser and Shevoroshkin is much older than the Etymological Dictionary of the Altaic Languages (2003; see Altaic languages article) and therefore assumes a somewhat different phonological system for Proto-Altaic.

| Consonants | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proto-Nostratic | Proto-Indo-European | Proto-Kartvelian | Proto-Uralic | Proto-Altaic | Proto-Dravidian | Proto-Afroasiatic | |||

| /p/ | /p/, /b/ | /p/, /b/ | /p/ | /p/ | "p₁"-, -/p/-, /v/- | "p₁"-, -/p/-, -/b/- | |||

| /pʼ/[48] | /p/ | /pʼ/-, /p/- | /p/-, -pp- -/pː/-, -/p/- | /pʰ/-, -/p/-, -/b/- | /b/-, -/p/-, -/v/- | /p/ | |||

| /b/ | bʰ /bʱ/ | /b/ | /p/-, -/w/- | /b/ | /b/-, -/v/-, -/p/- | /b/ | |||

| /m/ | /m/ | /m/ | /m/ | /m/, /b/ | /m/ | /m/ | |||

| /w/ | w/u̯ /w/ | /w/, /u/ | /w/, /u/ | /b/-?, ∅-, -/b/-, -∅-, /u/ | /v/-, ∅-, -/v/- | /w/, /u/ | |||

| /t/ | /d/ | /t/ | /t/ | /d/ | /d/-, -/t/-, -/d/- | /t/ | |||

| /tʼ/ | /t/ | /tʼ/ | /t/-, -tt- -/tː/-, -/t/- | /tʰ/-, -/t/- | /d/-, -/t/-, /d/- | /tʼ/, /t/ | |||

| /d/ | dʰ /dʱ/ | /d/ | /t/-, -ð- -/ð/- | /d/ | /d/-, -ṭ- -/ʈ/-, -ḍ- -/ɖ/- | /d/ | |||

| /ts/ (/tɕ/) | /sk/-, -/s/- | /ts/, /tɕ/ | ć /tɕ/ | /tʃʰ/, -/s/- | -/c/- | -/s/- | |||

| /tsʼ/ (/tɕʼ/) | /sk/-, -/s/- | /tsʼ/, /tɕʼ/ | ć /tɕ/ | /s/ |

|

| |||

| /dz/ (/dʑ/) | /s/ | /dz/, /dʑ/, /z/, /ʑ/ | /s/, ś /ɕ/ | /dʒ/ |

|

/z/- | |||

| /s/ (/ɕ/) | /s/ | /s/, /ɕ/ | /s/, ś /ɕ/ | /s/ | j /ɟ/ | /s/ | |||

| /n/ | /n/ | -/n/- | /n/ | -/n/- | n- /n̪/-, -n- -/n̪/-, -ṉ- -/n̺/- | /n/ | |||

| /nʲ/ | y-/i̯- /j/-, /n/- |

|

ń /nʲ/ | /nʲ/-, -/n/-? | -ṇ-? -/ɳ/ | /n/ | |||

| /r/ (/rʲ/) | /r/ | /r/ | /r/ | /l/-?, -/r/-, /rʲ/ | /n̪/-, -/r/-, -ṟ- -/r̺/-, ṛ /ɻ/ | /r/ | |||

| /tɬ/ | /s/-, -/l/- | /l/ | j- /j/- |

|

|

/tɬ/-, -/l/- | |||

| /ɬ/ | /l/ | /l/ | -x-? -/ɬ/-[49] | /l/ | /d/, /ɭ/ | /l/ | |||

| /l/ | /l/ | /l/ | /l/ | /l/ | n- /n̪/-, -/l/- | /l/ | |||

| /lʲ/ | /l/ | /r/, /l/ | lˈ /lʲ/ | /lʲ/ | ḷ /ɭ/ | /l/ | |||

| /tʃ/ | /st/-, /s/- | /tʃ/ | ć /tɕ/ | /tʃʰ/ |

|

| |||

| /tʃʼ/ | /st/ | /tʃʼ/ | č, š /tʃ/, /ʃ/ | /tʃʰ/-, -/s/- |

|

| |||

| /dʒ/ | /st/ | /dʒ/ | č /tʃ/ | /dʒ/ |

|

| |||

| /ʃ/ | /s/ | /ʃ/ | š /ʃ/ | /s/ | /d/, /ɭ/ |

| |||

| /j/ | y/i̯ /j/ | /j/ | /j/- | /j/ | y /j/ | /j/ | |||

| /k/ | /ɡ/, ǵ /ɡʲ/, gʷ /ɡʷ/[50] | /k/ | /k/ | /k/-, -/ɡ/- | /ɡ/-, -/k/-, -/ɡ/- | /k/ | |||

| /kʼ/ | /k/, ḱ /kʲ/, kʷ /kʷ/[50] | /kʼ/ | /k/-, -kk- -/kː/-, -/k/- | /kʰ/-, -/k/- | /ɡ/-, -/k/-, -/ɡ/- | /kʼ/ | |||

| /ɡ/ | gʰ /ɡʱ/, ǵʰ /ɡʲʱ/, gʰʷ /ɡʷʱ/[50] | /ɡ/ | /k/-, -x- -/ʁ/-[49] | /ɡ/ | /ɡ/-, -∅- | /ɡ/ | |||

| /ŋ/ | -/n/- | -/m/-? | /ŋ/ | -/nʲ/- | n- /n̪/-, -ṉ- -/n̺/-, -/t/- | -/n/- | |||

| /q/ | h₂ /χ/[49] | /q/ | ∅-, -/k/- | ∅-, -/k/-, -/ɡ/- | ∅-, -/ɡ/- | /χ/ | |||

| /qʼ/ | /k/, ḱ /kʲ/, kʷ /kʷ/[50] | /qʼ/-, -/kʼ/- | /k/-, -kk- -/kː/- | /kʰ/-, -/k/- | /ɡ/-, -/k/-, -/ɡ/- | /kʼ/ | |||

| /ɢ/ | h₃ /ʁ/[49] | /ʁ/ | -x- ∅-, -/ʁ/-[49] | ∅-, -/ɡ/- | ∅ | /ʁ/ | |||

| /χ/ | h₂ /χ/[49] | /χ/ | ∅-, -x- -/ʁ/-?[49] | ∅- | ∅- | /ħ/ | |||

| /ʁ/ | h₃ /ʁ/[49] | /ʁ/ | ∅-, -x- -/ʁ/-?[49] | ∅- | ∅- | /ʕ/ | |||

| /ħ/ | h₁ /h/[49] | /h/ > ∅ | ∅-, -x- -/ʁ/-?[49] | ∅- | ∅- | /ħ/ | |||

| /ʕ/ | h₁ /h/[49] | /h/ > ∅ | ∅-, -x- -/ʁ/-?[49] | ∅- | ∅- | /ʕ/ | |||

| /ʔ/ | h₁ /ʔ/[49] | /h/ > ∅ | ∅ | ∅ | ∅ | /ʔ/ | |||

| /h/ | h₂? /χ/[49] | /h/ > ∅ | ∅-, -x- -/ʁ/-?[49] | ∅- | ∅- | /h/ | |||

| Vowels | |||||||||

| Proto-Nostratic | Proto-Indo-European[51] | Proto-Kartvelian[51] | Proto-Uralic | Proto-Altaic | Proto-Dravidian | Proto-Afroasiatic[51] | |||

| /a/ | /e/, /a/ | /e/ | /a/ | /a/ | /a/ | /a/ ? | |||

| /e/ | /e/, ∅ | /e/, ∅ | /e/ | /e/ | /e/, /i/ |

| |||

| /i/ | /ai̯/, /e/, /ei̯/, /i/, ∅ | /e/, /i/, ∅ | /i/ | /i/ | /i/ | /i/ ? | |||

| /o/ | /e/, /o/ | /we/ ~ /wa/ | /o/ | /o/ | /o/, /a/ |

| |||

| /u/ | /au̯/, /e/, /eu̯/, /u/ | /u/ ~ /wa/ | /u/ | /u/ | /u/, /o/ | /u/ ? | |||

| /æ/ | /e/ | /e/, /a/, /aː/ | /æ/ | ä /æ/ | /a/ |

| |||

| /y/ | /e/ | /u/ | /y/, /ø/ | ü /y/ | /u/ |

| |||

Morphology