A magic item is any object that has magical powers inherent in it. These may act on their own or be the tools of the person or being whose hands they fall into. Magic items are commonly found in both folklore and modern fantasy. Their fictional appearance is as old as the Iliad in which Aphrodite's magical girdle is used by Hera as a love charm.[1]

Magic items often act as a plot device to grant magical abilities. They may give magical abilities to a person lacking in them, or enhance the power of a wizard. For instance, in J.R.R. Tolkien's The Hobbit, the magical ring allows Bilbo Baggins to be instrumental in the quest, exceeding the abilities of the dwarves.[2]

Magic items are often, also, used as MacGuffins. The characters in a story must collect an arbitrary number of magical items, and when they have the full set, the magic is sufficient to resolve the plot. In video games, these types of items are usually collected in fetch quests.

Fairy tales

Certain kinds of fairy tales have their plots dominated by the magic items they contain. One such is the tale where the hero has a magic item that brings success, loses the item either accidentally (The Tinder Box) or through an enemy's actions (The Bronze Ring), and must regain it to regain his success.[3] Another is the magic item that runs out of control when the character knows how to start it but not to stop it: the mill in Why the Sea Is Salt or the pot in Sweet Porridge.[4] A third is the tale in which a hero has two rewards stolen from him, and a third reward attacks the thief.[5]

Types of magic items

Many works of folklore and fantasy include very similar items, that can be grouped into types. These include:

- Magic swords

- Sentient weapons

- Magic rings

- Cloaks of invisibility

- Potions

- Magic carpets

- Seven-league boots

- Fairy ointments

- Wands

Artifacts

In role-playing games and fantasy literature, an artifact is a magical object with great power. Often, this power is so great that it cannot be duplicated by any known art allowed by the premises of the fantasy world, and often cannot be destroyed by ordinary means. Artifacts often serve as MacGuffins, the central focus of quests to locate, capture, or destroy them. The One Ring of The Lord of the Rings is a typical artifact: it was alarmingly powerful, of ancient and obscure origin, and nearly indestructible.

In fiction

This interpretation may have arisen as an extension of the archaeological meaning of the word; fantasy artifacts are often the remains of earlier civilisations established by beings of great magical power (cf. many artifacts in Lovecraft's Cthulhu Mythos, as well as the "Forgotten Realms" Dungeons & Dragons setting).[citation needed]

In Dungeons & Dragons

In Dungeons & Dragons, artifacts are magic items that either cannot be created by players or the secrets to their creation is not given. In any event, artifacts have no market price and have no hit points (that is, they are indestructible by normal spells). Artifacts typically have no inherent limit of using their powers. Under strict rules, any artifact can theoretically be destroyed by the sorcerer/wizard spell Mordenkainen's Disjunction, but for the purposes of a campaign centered on destroying an artifact, a plot-related means of destruction is generally substituted. Artifacts in D&D are split into two categories. Minor artifacts are common, but they can no longer be created, whereas major artifacts are unique – only one of each item exists.[6]

In Harry Potter

In the Harry Potter series by J. K. Rowling, several magical objects exist for the use of the characters. Some of them play a crucial role in the main plot. There are objects for different purposes such as communication, transportation, games, storage, as well as legendary artifacts and items with dark properties.

References

- Cook, Monte (July 2003). Dungeon Master's Guide (v.3.5 ed.). Renton, WA: Wizards of the Coast. pp. 277–280.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Magic_item

| Magna Carta | |

|---|---|

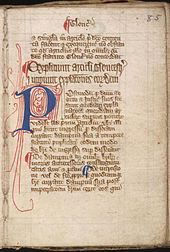

Cotton MS. Augustus II. 106, one of four surviving exemplifications of the 1215 text | |

| Created | 1215 |

| Location | Two at the British Library; one each in Lincoln Castle and in Salisbury Cathedral |

| Author(s) | |

| Purpose | Peace treaty |

| Full Text | |

| Part of the Politics series |

| Monarchy |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| This article is part of a series on |

| Politics of the United Kingdom |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

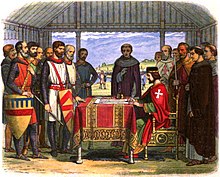

Magna Carta Libertatum (Medieval Latin for "Great Charter of Freedoms"), commonly called Magna Carta (also Magna Charta; "Great Charter"),[a] is a royal charter[4][5] of rights agreed to by King John of England at Runnymede, near Windsor, on 15 June 1215.[b] First drafted by the Archbishop of Canterbury, Cardinal Stephen Langton, to make peace between the unpopular king and a group of rebel barons, it promised the protection of church rights, protection for the barons from illegal imprisonment, access to swift justice, and limitations on feudal payments to the Crown, to be implemented through a council of 25 barons. Neither side stood behind their commitments, and the charter was annulled by Pope Innocent III, leading to the First Barons' War.

After John's death, the regency government of his young son, Henry III, reissued the document in 1216, stripped of some of its more radical content, in an unsuccessful bid to build political support for their cause. At the end of the war in 1217, it formed part of the peace treaty agreed at Lambeth, where the document acquired the name "Magna Carta", to distinguish it from the smaller Charter of the Forest which was issued at the same time. Short of funds, Henry reissued the charter again in 1225 in exchange for a grant of new taxes. His son, Edward I, repeated the exercise in 1297, this time confirming it as part of England's statute law. The charter became part of English political life and was typically renewed by each monarch in turn, although as time went by and the fledgling Parliament of England passed new laws, it lost some of its practical significance.

At the end of the 16th century, there was an upsurge in interest in Magna Carta. Lawyers and historians at the time believed that there was an ancient English constitution, going back to the days of the Anglo-Saxons, that protected individual English freedoms. They argued that the Norman invasion of 1066 had overthrown these rights, and that Magna Carta had been a popular attempt to restore them, making the charter an essential foundation for the contemporary powers of Parliament and legal principles such as habeas corpus. Although this historical account was badly flawed, jurists such as Sir Edward Coke used Magna Carta extensively in the early 17th century, arguing against the divine right of kings. Both James I and his son Charles I attempted to suppress the discussion of Magna Carta. The political myth of Magna Carta and its protection of ancient personal liberties persisted after the Glorious Revolution of 1688 until well into the 19th century. It influenced the early American colonists in the Thirteen Colonies and the formation of the United States Constitution, which became the supreme law of the land in the new republic of the United States.[c] Research by Victorian historians showed that the original 1215 charter had concerned the medieval relationship between the monarch and the barons, rather than the rights of ordinary people, but the charter remained a powerful, iconic document, even after almost all of its content was repealed from the statute books in the 19th and 20th centuries. None of the original 1215 Magna Carta is currently in force as it was repealed, however four clauses of the original charter (1 (part), 13, 39 and 40) are enshrined in the 1297 reissued Magna Carta and do still remain in force in England and Wales (as clauses 1, 9 and 29 of the 1297 statute).[6][7]

Magna Carta still forms an important symbol of liberty today, often cited by politicians and campaigners, and is held in great respect by the British and American legal communities, Lord Denning describing it as "the greatest constitutional document of all times—the foundation of the freedom of the individual against the arbitrary authority of the despot".[8] In the 21st century, four exemplifications of the original 1215 charter remain in existence, two at the British Library, one at Lincoln Castle and one at Salisbury Cathedral. There are also a handful of the subsequent charters in public and private ownership, including copies of the 1297 charter in both the United States and Australia. Although scholars refer to the 63 numbered "clauses" of Magna Carta, this is a modern system of numbering, introduced by Sir William Blackstone in 1759; the original charter formed a single, long unbroken text. The four original 1215 charters were displayed together at the British Library for one day, 3 February 2015, to mark the 800th anniversary of Magna Carta.

History

13th century

Background

Magna Carta originated as an unsuccessful attempt to achieve peace between royalist and rebel factions in 1215, as part of the events leading to the outbreak of the First Barons' War. England was ruled by King John, the third of the Angevin kings. Although the kingdom had a robust administrative system, the nature of government under the Angevin monarchs was ill-defined and uncertain.[9][10] John and his predecessors had ruled using the principle of vis et voluntas, or "force and will", taking executive and sometimes arbitrary decisions, often justified on the basis that a king was above the law.[10] Many contemporary writers believed that monarchs should rule in accordance with the custom and the law, with the counsel of the leading members of the realm, but there was no model for what should happen if a king refused to do so.[10]

John had lost most of his ancestral lands in France to King Philip II in 1204 and had struggled to regain them for many years, raising extensive taxes on the barons to accumulate money to fight a war which ended in expensive failure in 1214.[11] Following the defeat of his allies at the Battle of Bouvines, John had to sue for peace and pay compensation.[12] John was already personally unpopular with many of the barons, many of whom owed money to the Crown, and little trust existed between the two sides.[13][14][15] A triumph would have strengthened his position, but in the face of his defeat, within a few months after his return from France, John found that rebel barons in the north and east of England were organising resistance to his rule.[16][17]

The rebels took an oath that they would "stand fast for the liberty of the church and the realm", and demanded that the King confirm the Charter of Liberties that had been declared by King Henry I in the previous century, and which was perceived by the barons to protect their rights.[17][18][19] The rebel leadership was unimpressive by the standards of the time, even disreputable, but were united by their hatred of John;[20] Robert Fitzwalter, later elected leader of the rebel barons, claimed publicly that John had attempted to rape his daughter,[21] and was implicated in a plot to assassinate John in 1212.[22]

John held a council in London in January 1215 to discuss potential reforms, and sponsored discussions in Oxford between his agents and the rebels during the spring.[23] Both sides appealed to Pope Innocent III for assistance in the dispute.[24] During the negotiations, the rebellious barons produced an initial document, which historians have termed "the Unknown Charter of Liberties", which drew on Henry I's Charter of Liberties for much of its language; seven articles from that document later appeared in the "Articles of the Barons" and the subsequent charter.[25][26][27]

It was John's hope that the Pope would give him valuable legal and moral support, and accordingly John played for time; the King had declared himself to be a papal vassal in 1213 and correctly believed he could count on the Pope for help.[24][28] John also began recruiting mercenary forces from France, although some were later sent back to avoid giving the impression that the King was escalating the conflict.[23] In a further move to shore up his support, John took an oath to become a crusader, a move which gave him additional political protection under church law, even though many felt the promise was insincere.[29][30]

Letters backing John arrived from the Pope in April, but by then the rebel barons had organised into a military faction. They congregated at Northampton in May and renounced their feudal ties to John, marching on London, Lincoln, and Exeter.[31] John's efforts to appear moderate and conciliatory had been largely successful, but once the rebels held London, they attracted a fresh wave of defectors from the royalists.[32] The King offered to submit the problem to a committee of arbitration with the Pope as the supreme arbiter, but this was not attractive to the rebels.[33] Stephen Langton, the archbishop of Canterbury, had been working with the rebel barons on their demands, and after the suggestion of papal arbitration failed, John instructed Langton to organise peace talks.[32][34]

Great Charter of 1215

John met the rebel leaders at Runnymede, a water-meadow on the south bank of the River Thames, on 10 June 1215. Runnymede was a traditional place for assemblies, but it was also located on neutral ground between the royal fortress of Windsor Castle and the rebel base at Staines, and offered both sides the security of a rendezvous where they were unlikely to find themselves at a military disadvantage.[35][36] Here the rebels presented John with their draft demands for reform, the 'Articles of the Barons'.[32][34][37] Stephen Langton's pragmatic efforts at mediation over the next ten days turned these incomplete demands into a charter capturing the proposed peace agreement; a few years later, this agreement was renamed Magna Carta, meaning "Great Charter".[34][37][38] By 15 June, general agreement had been made on a text, and on 19 June, the rebels renewed their oaths of loyalty to John and copies of the charter were formally issued.[34][37]

Although, as the historian David Carpenter has noted, the charter "wasted no time on political theory", it went beyond simply addressing individual baronial complaints, and formed a wider proposal for political reform.[32][39] It promised the protection of church rights, protection from illegal imprisonment, access to swift justice, and, most importantly, limitations on taxation and other feudal payments to the Crown, with certain forms of feudal taxation requiring baronial consent.[16][40] It focused on the rights of free men—in particular, the barons.[39] The rights of serfs were included in articles 16, 20 and 28.[41][d] Its style and content reflected Henry I's Charter of Liberties, as well as a wider body of legal traditions, including the royal charters issued to towns, the operations of the Church and baronial courts and European charters such as the Statute of Pamiers.[44][45]

Under what historians later labelled "clause 61", or the "security clause", a council of 25 barons would be created to monitor and ensure John's future adherence to the charter.[46] If John did not conform to the charter within 40 days of being notified of a transgression by the council, the 25 barons were empowered by clause 61 to seize John's castles and lands until, in their judgement, amends had been made.[47] Men were to be compelled to swear an oath to assist the council in controlling the King, but once redress had been made for any breaches, the King would continue to rule as before.[48]

In one sense this was not unprecedented. Other kings had previously conceded the right of individual resistance to their subjects if the King did not uphold his obligations. Magna Carta was novel in that it set up a formally recognised means of collectively coercing the King.[48] The historian Wilfred Warren argues that it was almost inevitable that the clause would result in civil war, as it "was crude in its methods and disturbing in its implications".[49] The barons were trying to force John to keep to the charter, but clause 61 was so heavily weighted against the King that this version of the charter could not survive.[47]

John and the rebel barons did not trust each other, and neither side seriously attempted to implement the peace accord.[46][50] The 25 barons selected for the new council were all rebels, chosen by the more extremist barons, and many among the rebels found excuses to keep their forces mobilised.[51][52][53] Disputes began to emerge between the royalist faction and those rebels who had expected the charter to return lands that had been confiscated.[54]

Clause 61 of Magna Carta contained a commitment from John that he would "seek to obtain nothing from anyone, in our own person or through someone else, whereby any of these grants or liberties may be revoked or diminished".[55][56] Despite this, the King appealed to Pope Innocent for help in July, arguing that the charter compromised the Pope's rights as John's feudal lord.[54][57] As part of the June peace deal, the barons were supposed to surrender London by 15 August, but this they refused to do.[58] Meanwhile, instructions from the Pope arrived in August, written before the peace accord, with the result that papal commissioners excommunicated the rebel barons and suspended Langton from office in early September.[59]

Once aware of the charter, the Pope responded in detail: in a letter dated 24 August and arriving in late September, he declared the charter to be "not only shameful and demeaning but also illegal and unjust" since John had been "forced to accept" it, and accordingly the charter was "null, and void of all validity for ever"; under threat of excommunication, the King was not to observe the charter, nor the barons try to enforce it.[54][58][60][61]

By then, violence had broken out between the two sides. Less than three months after it had been agreed, John and the loyalist barons firmly repudiated the failed charter: the First Barons' War erupted.[54][62][63] The rebel barons concluded that peace with John was impossible, and turned to Philip II's son, the future Louis VIII, for help, offering him the English throne.[54][64][e] The war soon settled into a stalemate. The King became ill and died on the night of 18 October 1216, leaving the nine-year-old Henry III as his heir.[65]

Charters of the Welsh Princes

The Magna Carta of 1215 was the first document in which reference is made to English and Welsh law alongside one another, including the principle of the common acceptance of the lawful judgement of peers.

Chapter 56: The return of lands and liberties to Welshmen if those lands and liberties had been taken by English (and vice versa) without a law abiding judgement of their peers.

Chapter 57: The return of Gruffydd ap Llywelyn, illegitimate son of Llywelyn ap Iorwerth (Llywelyn the Great) along with other Welsh hostages which were originally taken for "peace" and "good".[66][67]

Lists of participants in 1215

Counsellors named in Magna Carta

The preamble to Magna Carta includes the names of the following 27 ecclesiastical and secular magnates who had counselled John to accept its terms. The names include some of the moderate reformers, notably Archbishop Stephen Langton, and some of John's loyal supporters, such as William Marshal, Earl of Pembroke. They are listed here in the order in which they appear in the charter itself:[68]

- Stephen Langton, Archbishop of Canterbury and Cardinal

- Henry de Loundres, Archbishop of Dublin

- William of Sainte-Mère-Église, Bishop of London

- Peter des Roches, Bishop of Winchester

- Jocelin of Wells, Bishop of Bath and Glastonbury

- Hugh of Wells, Bishop of Lincoln

- Walter de Gray, Bishop of Worcester

- William de Cornhill, Bishop of Coventry

- Benedict of Sausetun, Bishop of Rochester

- Pandulf Verraccio, subdeacon and papal legate to England

- Eymeric, Master of the Knights Templar in England

- William Marshal, Earl of Pembroke

- William Longespée, Earl of Salisbury

- William de Warenne, Earl of Surrey

- William d'Aubigny, Earl of Arundel

- Alan of Galloway, Constable of Scotland

- Warin FitzGerold

- Peter FitzHerbert

- Hubert de Burgh, Seneschal of Poitou

- Hugh de Neville

- Matthew FitzHerbert

- Thomas Basset

- Alan Basset

- Philip d'Aubigny

- Robert of Ropsley

- John Marshal

- John FitzHugh

The Council of Twenty-Five Barons

The names of the Twenty-Five Barons appointed under clause 61 to monitor John's future conduct are not given in the charter itself, but do appear in four early sources, all seemingly based on a contemporary listing: a late-13th-century collection of law tracts and statutes, a Reading Abbey manuscript now in Lambeth Palace Library, and the Chronica Majora and Liber Additamentorum of Matthew Paris.[69][70][71] The process of appointment is not known, but the names were drawn almost exclusively from among John's more active opponents.[72] They are listed here in the order in which they appear in the original sources:

- Richard de Clare, Earl of Hertford

- William de Forz, Earl of Albemarle

- Geoffrey de Mandeville, Earl of Essex and Gloucester

- Saer de Quincy, Earl of Winchester

- Henry de Bohun, Earl of Hereford

- Roger Bigod, Earl of Norfolk and Suffolk

- Robert de Vere, Earl of Oxford

- William Marshal junior

- Robert Fitzwalter, baron of Little Dunmow

- Gilbert de Clare, heir to the earldom of Hertford

- Eustace de Vesci, Lord of Alnwick Castle

- Hugh Bigod, heir to the Earldoms of Norfolk and Suffolk

- William de Mowbray, Lord of Axholme Castle

- William Hardell, Mayor of the City of London

- William de Lanvallei, Lord of Walkern

- Robert de Ros, Baron of Helmsley

- John de Lacy, Constable of Chester and Lord of Pontefract Castle

- Richard de Percy

- John FitzRobert de Clavering, Lord of Warkworth Castle

- William Malet

- Geoffrey de Saye

- Roger de Montbegon, Lord of Hornby Castle, Lancashire[f]

- William of Huntingfield, Sheriff of Norfolk and Suffolk

- Richard de Montfichet

- William d'Aubigny, Lord of Belvoir

Excommunicated rebels

In September 1215, the papal commissioners in England—Subdeacon Pandulf, Peter des Roches, Bishop of Winchester, and Simon, Abbot of Reading—excommunicated the rebels, acting on instructions earlier received from Rome. A letter sent by the commissioners from Dover on 5 September to Archbishop Langton explicitly names nine senior rebel barons (all members of the Council of Twenty-Five), and six clerics numbered among the rebel ranks:[73]

Barons

Clerics

- Giles de Braose, Bishop of Hereford

- William, Archdeacon of Hereford

- Alexander the clerk (possibly Alexander of St Albans)

- Osbert de Samara

- John de Fereby

- Robert, chaplain to Robert Fitzwalter

Great Charter of 1216

Although the Charter of 1215 was a failure as a peace treaty, it was resurrected under the new government of the young Henry III as a way of drawing support away from the rebel faction. On his deathbed, King John appointed a council of thirteen executors to help Henry reclaim the kingdom, and requested that his son be placed into the guardianship of William Marshal, one of the most famous knights in England.[74] William knighted the boy, and Cardinal Guala Bicchieri, the papal legate to England, then oversaw his coronation at Gloucester Cathedral on 28 October.[75][76][77]

The young King inherited a difficult situation, with over half of England occupied by the rebels.[78][79] He had substantial support though from Guala, who intended to win the civil war for Henry and punish the rebels.[80] Guala set about strengthening the ties between England and the Papacy, starting with the coronation itself, during which Henry gave homage to the Papacy, recognising the Pope as his feudal lord.[75][81] Pope Honorius III declared that Henry was the Pope's vassal and ward, and that the legate had complete authority to protect Henry and his kingdom.[75] As an additional measure, Henry took the cross, declaring himself a crusader and thereby entitled to special protection from Rome.[75]

The war was not going well for the loyalists, but Prince Louis and the rebel barons were also finding it difficult to make further progress.[82][83] John's death had defused some of the rebel concerns, and the royal castles were still holding out in the occupied parts of the country.[83][84] Henry's government encouraged the rebel barons to come back to his cause in exchange for the return of their lands, and reissued a version of the 1215 Charter, albeit having first removed some of the clauses, including those unfavourable to the Papacy and clause 61, which had set up the council of barons.[85][86] The move was not successful, and opposition to Henry's new government hardened.[87]

Great Charter of 1217

In February 1217, Louis set sail for France to gather reinforcements.[88] In his absence, arguments broke out between Louis' French and English followers, and Cardinal Guala declared that Henry's war against the rebels was the equivalent of a religious crusade.[89] This declaration resulted in a series of defections from the rebel movement, and the tide of the conflict swung in Henry's favour.[90] Louis returned at the end of April, but his northern forces were defeated by William Marshal at the Battle of Lincoln in May.[91][92]

Meanwhile, support for Louis' campaign was diminishing in France, and he concluded that the war in England was lost.[93] He negotiated terms with Cardinal Guala, under which Louis would renounce his claim to the English throne. In return, his followers would be given back their lands, any sentences of excommunication would be lifted, and Henry's government would promise to enforce the charter of the previous year.[94] The proposed agreement soon began to unravel amid claims from some loyalists that it was too generous towards the rebels, particularly the clergy who had joined the rebellion.[95]

In the absence of a settlement, Louis stayed in London with his remaining forces, hoping for the arrival of reinforcements from France.[95] When the expected fleet arrived in August, it was intercepted and defeated by loyalists at the Battle of Sandwich.[96] Louis entered into fresh peace negotiations. The factions came to agreement on the final Treaty of Lambeth, also known as the Treaty of Kingston, on 12 and 13 September 1217.[96]

The treaty was similar to the first peace offer, but excluded the rebel clergy, whose lands and appointments remained forfeit. It included a promise that Louis' followers would be allowed to enjoy their traditional liberties and customs, referring back to the Charter of 1216.[97] Louis left England as agreed. He joined the Albigensian Crusade in the south of France, bringing the war to an end.[93]

A great council was called in October and November to take stock of the post-war situation. This council is thought to have formulated and issued the Charter of 1217.[98] The charter resembled that of 1216, although some additional clauses were added to protect the rights of the barons over their feudal subjects, and the restrictions on the Crown's ability to levy taxation were watered down.[99] There remained a range of disagreements about the management of the royal forests, which involved a special legal system that had resulted in a source of considerable royal revenue. Complaints existed over both the implementation of these courts, and the geographic boundaries of the royal forests.[100]

A complementary charter, the Charter of the Forest, was created, pardoning existing forest offences, imposing new controls over the forest courts, and establishing a review of the forest boundaries.[100] To distinguish the two charters, the term 'magna carta libertatum' ("the great charter of liberties") was used by the scribes to refer to the larger document, which in time became known simply as Magna Carta.[101][102]

Great Charter of 1225

Magna Carta became increasingly embedded into English political life during Henry III's minority.[103] As the King grew older, his government slowly began to recover from the civil war, regaining control of the counties and beginning to raise revenue once again, taking care not to overstep the terms of the charters.[104] Henry remained a minor and his government's legal ability to make permanently binding decisions on his behalf was limited. In 1223, the tensions over the status of the charters became clear in the royal court, when Henry's government attempted to reassert its rights over its properties and revenues in the counties, facing resistance from many communities that argued—if sometimes incorrectly—that the charters protected the new arrangements.[105][106]

This resistance resulted in an argument between Archbishop Langton and William Brewer over whether the King had any duty to fulfil the terms of the charters, given that he had been forced to agree to them.[107] On this occasion, Henry gave oral assurances that he considered himself bound by the charters, enabling a royal inquiry into the situation in the counties to progress.[108]

In 1225, the question of Henry's commitment to the charters re-emerged, when Louis VIII of France invaded Henry's remaining provinces in France, Poitou and Gascony.[109][110] Henry's army in Poitou was under-resourced, and the province quickly fell.[111] It became clear that Gascony would also fall unless reinforcements were sent from England.[112] In early 1225, a great council approved a tax of £40,000 to dispatch an army, which quickly retook Gascony.[113][114] In exchange for agreeing to support Henry, the barons demanded that the King reissue Magna Carta and the Charter of the Forest.[115][116] The content was almost identical to the 1217 versions, but in the new versions, the King declared that the charters were issued of his own "spontaneous and free will" and confirmed them with the royal seal, giving the new Great Charter and the Charter of the Forest of 1225 much more authority than the previous versions.[116][117]

The barons anticipated that the King would act in accordance with these charters, subject to the law and moderated by the advice of the nobility.[118][119] Uncertainty continued, and in 1227, when he was declared of age and able to rule independently, Henry announced that future charters had to be issued under his own seal.[120][121] This brought into question the validity of the previous charters issued during his minority, and Henry actively threatened to overturn the Charter of the Forest unless the taxes promised in return for it were actually paid.[120][121] In 1253, Henry confirmed the charters once again in exchange for taxation.[122]

Henry placed a symbolic emphasis on rebuilding royal authority, but his rule was relatively circumscribed by Magna Carta.[77][123] He generally acted within the terms of the charters, which prevented the Crown from taking extrajudicial action against the barons, including the fines and expropriations that had been common under his father, John.[77][123] The charters did not address the sensitive issues of the appointment of royal advisers and the distribution of patronage, and they lacked any means of enforcement if the King chose to ignore them.[124] The inconsistency with which he applied the charters over the course of his rule alienated many barons, even those within his own faction.[77]

Despite the various charters, the provision of royal justice was inconsistent and driven by the needs of immediate politics: sometimes action would be taken to address a legitimate baronial complaint, while on other occasions the problem would simply be ignored.[125] The royal courts, which toured the country to provide justice at the local level, typically for lesser barons and the gentry claiming grievances against major lords, had little power, allowing the major barons to dominate the local justice system.[126] Henry's rule became lax and careless, resulting in a reduction in royal authority in the provinces and, ultimately, the collapse of his authority at court.[77][126]

In 1258, a group of barons seized power from Henry in a coup d'état, citing the need to strictly enforce Magna Carta and the Charter of the Forest, creating a new baronial-led government to advance reform through the Provisions of Oxford.[127] The barons were not militarily powerful enough to win a decisive victory, and instead appealed to Louis IX of France in 1263–1264 to arbitrate on their proposed reforms. The reformist barons argued their case based on Magna Carta, suggesting that it was inviolable under English law and that the King had broken its terms.[128]

Louis came down firmly in favour of Henry, but the French arbitration failed to achieve peace as the rebellious barons refused to accept the verdict. England slipped back into the Second Barons' War, which was won by Henry's son, the Lord Edward. Edward also invoked Magna Carta in advancing his cause, arguing that the reformers had taken matters too far and were themselves acting against Magna Carta.[129] In a conciliatory gesture after the barons had been defeated, in 1267 Henry issued the Statute of Marlborough, which included a fresh commitment to observe the terms of Magna Carta.[130]

Witnesses in 1225

Great Charter of 1297: statute

King Edward I reissued the Charters of 1225 in 1297 in return for a new tax.[132] It is this version which remains in statute today, although with most articles now repealed.[133][134]

The Confirmatio Cartarum (Confirmation of Charters) was issued in Norman French by Edward I in 1297.[135] Edward, needing money, had taxed the nobility, and they had armed themselves against him, forcing Edward to issue his confirmation of Magna Carta and the Forest Charter to avoid civil war.[136] The nobles had sought to add another document, the De Tallagio, to Magna Carta. Edward I's government was not prepared to concede this, they agreed to the issuing of the Confirmatio, confirming the previous charters and confirming the principle that taxation should be by consent,[132] although the precise manner of that consent was not laid down.[137]

A passage mandates that copies shall be distributed in "cathedral churches throughout our realm, there to remain, and shall be read before the people two times by the year",[138] hence the permanent installation of a copy in Salisbury Cathedral.[139] In the Confirmation's second article, it is confirmed that

if any judgement be given from henceforth contrary to the points of the charters aforesaid by the justices, or by any other our ministers that hold plea before them against the points of the charters, it shall be undone, and holden for nought.[140][141]

With the reconfirmation of the Charters in 1300, an additional document was granted, the Articuli super Cartas (The Articles upon the Charters).[142] It was composed of 17 articles and sought in part to deal with the problem of enforcing the Charters. Magna Carta and the Forest Charter were to be issued to the sheriff of each county, and should be read four times a year at the meetings of the county courts. Each county should have a committee of three men who could hear complaints about violations of the Charters.[143]

Pope Clement V continued the papal policy of supporting monarchs (who ruled by divine grace) against any claims in Magna Carta which challenged the King's rights, and annulled the Confirmatio Cartarum in 1305. Edward I interpreted Clement V's papal bull annulling the Confirmatio Cartarum as effectively applying to the Articuli super Cartas, although the latter was not specifically mentioned.[144] In 1306 Edward I took the opportunity given by the Pope's backing to reassert forest law over large areas which had been "disafforested". Both Edward and the Pope were accused by some contemporary chroniclers of "perjury", and it was suggested by Robert McNair Scott that Robert the Bruce refused to make peace with Edward I's son, Edward II, in 1312 with the justification: "How shall the king of England keep faith with me, since he does not observe the sworn promises made to his liege men ...".[145][146]

Magna Carta's influence on English medieval law

The Great Charter was referred to in legal cases throughout the medieval period. For example, in 1226, the knights of Lincolnshire argued that their local sheriff was changing customary practice regarding the local courts, "contrary to their liberty which they ought to have by the charter of the lord king".[147] In practice, cases were not brought against the King for breach of Magna Carta and the Forest Charter, but it was possible to bring a case against the King's officers, such as his sheriffs, using the argument that the King's officers were acting contrary to liberties granted by the King in the charters.[148]

In addition, medieval cases referred to the clauses in Magna Carta which dealt with specific issues such as wardship and dower, debt collection, and keeping rivers free for navigation.[149] Even in the 13th century, some clauses of Magna Carta rarely appeared in legal cases, either because the issues concerned were no longer relevant, or because Magna Carta had been superseded by more relevant legislation. By 1350 half the clauses of Magna Carta were no longer actively used.[150]

14th–15th centuries

During the reign of King Edward III six measures, later known as the Six Statutes, were passed between 1331 and 1369. They sought to clarify certain parts of the Charters. In particular the third statute, in 1354, redefined clause 29, with "free man" becoming "no man, of whatever estate or condition he may be", and introduced the phrase "due process of law" for "lawful judgement of his peers or the law of the land".[151]

Between the 13th and 15th centuries Magna Carta was reconfirmed 32 times according to Sir Edward Coke, and possibly as many as 45 times.[152][153] Often the first item of parliamentary business was a public reading and reaffirmation of the Charter, and, as in the previous century, parliaments often exacted confirmation of it from the monarch.[153] The Charter was confirmed in 1423 by King Henry VI.[154][155][156]

By the mid-15th century, Magna Carta ceased to occupy a central role in English political life, as monarchs reasserted authority and powers which had been challenged in the 100 years after Edward I's reign.[157] The Great Charter remained a text for lawyers, particularly as a protector of property rights, and became more widely read than ever as printed versions circulated and levels of literacy increased.[158]

16th century

During the 16th century, the interpretation of Magna Carta and the First Barons' War shifted.[159] Henry VII took power at the end of the turbulent Wars of the Roses, followed by Henry VIII, and extensive propaganda under both rulers promoted the legitimacy of the regime, the illegitimacy of any sort of rebellion against royal power, and the priority of supporting the Crown in its arguments with the Papacy.[160]

Tudor historians rediscovered the Barnwell chronicler, who was more favourable to King John than other 13th-century texts, and, as historian Ralph Turner describes, they "viewed King John in a positive light as a hero struggling against the papacy", showing "little sympathy for the Great Charter or the rebel barons".[161] Pro-Catholic demonstrations during the 1536 uprising cited Magna Carta, accusing the King of not giving it sufficient respect.[162]

The first mechanically printed edition of Magna Carta was probably the Magna Carta cum aliis Antiquis Statutis of 1508 by Richard Pynson, although the early printed versions of the 16th century incorrectly attributed the origins of Magna Carta to Henry III and 1225, rather than to John and 1215, and accordingly worked from the later text.[163][164][165] An abridged English-language edition was published by John Rastell in 1527. Thomas Berthelet, Pynson's successor as the royal printer during 1530–1547, printed an edition of the text along with other "ancient statutes" in 1531 and 1540.[166]

In 1534, George Ferrers published the first unabridged English-language edition of Magna Carta, dividing the Charter into 37 numbered clauses.[167]

The mid-sixteenth century funerary monument Sir Rowland Hill of Soulton, placed in St Stephens Wallbroke, included a full statue[168] of the Tudor statesman and judge holding a copy of Magna Carta.[169] Hill was a Mercer and a Lord Mayor of London; both of these statuses were shared with Serlo the Mercer who was a negotiator and enforcer of Magna Carta.[170] The original monument was lost in the Great Fire of London, but it was restated on a 110 foot tall column on his family's estates in Shropshire.[171]

At the end of the 16th century, there was an upsurge in antiquarian interest in England.[162] This work concluded that there was a set of ancient English customs and laws, temporarily overthrown by the Norman invasion of 1066, which had then been recovered in 1215 and recorded in Magna Carta, which in turn gave authority to important 16th-century legal principles.[162][172][173] Modern historians note that although this narrative was fundamentally incorrect—many refer to it as a "myth"—it took on great importance among the legal historians of the time.[173][g]

The antiquarian William Lambarde, for example, published what he believed were the Anglo-Saxon and Norman law codes, tracing the origins of the 16th-century English Parliament back to this period, albeit misinterpreting the dates of many documents concerned.[172] Francis Bacon argued that clause 39 of Magna Carta was the basis of the 16th-century jury system and judicial processes.[178] Antiquarians Robert Beale, James Morice and Richard Cosin argued that Magna Carta was a statement of liberty and a fundamental, supreme law empowering English government.[179] Those who questioned these conclusions, including the Member of Parliament Arthur Hall, faced sanctions.[180][181]

17th–18th centuries

Political tensions

In the early 17th century, Magna Carta became increasingly important as a political document in arguments over the authority of the English monarchy.[182] James I and Charles I both propounded greater authority for the Crown, justified by the doctrine of the divine right of kings, and Magna Carta was cited extensively by their opponents to challenge the monarchy.[175]

Magna Carta, it was argued, recognised and protected the liberty of individual Englishmen, made the King subject to the common law of the land, formed the origin of the trial by jury system, and acknowledged the ancient origins of Parliament: because of Magna Carta and this ancient constitution, an English monarch was unable to alter these long-standing English customs.[175][182][183][184] Although the arguments based on Magna Carta were historically inaccurate, they nonetheless carried symbolic power, as the charter had immense significance during this period; antiquarians such as Sir Henry Spelman described it as "the most majestic and a sacrosanct anchor to English Liberties".[173][175][182]

Sir Edward Coke was a leader in using Magna Carta as a political tool during this period. Still working from the 1225 version of the text – the first printed copy of the 1215 charter only emerged in 1610 – Coke spoke and wrote about Magna Carta repeatedly.[173] His work was challenged at the time by Lord Ellesmere, and modern historians such as Ralph Turner and Claire Breay have critiqued Coke as "misconstruing" the original charter "anachronistically and uncritically", and taking a "very selective" approach to his analysis.[175][185] More sympathetically, J. C. Holt noted that the history of the charters had already become "distorted" by the time Coke was carrying out his work.[186]

In 1621, a bill was presented to Parliament to renew Magna Carta; although this bill failed, lawyer John Selden argued during Darnell's Case in 1627 that the right of habeas corpus was backed by Magna Carta.[187][188] Coke supported the Petition of Right in 1628, which cited Magna Carta in its preamble, attempting to extend the provisions, and to make them binding on the judiciary.[189][190] The monarchy responded by arguing that the historical legal situation was much less clear-cut than was being claimed, restricted the activities of antiquarians, arrested Coke for treason, and suppressed his proposed book on Magna Carta.[188][191] Charles initially did not agree to the Petition of Right, and refused to confirm Magna Carta in any way that would reduce his independence as King.[192][193]

England descended into civil war in the 1640s, resulting in Charles I's execution in 1649. Under the republic that followed, some questioned whether Magna Carta, an agreement with a monarch, was still relevant.[194] An anti-Cromwellian pamphlet published in 1660, The English devil, said that the nation had been "compelled to submit to this Tyrant Nol or be cut off by him; nothing but a word and a blow, his Will was his Law; tell him of Magna Carta, he would lay his hand on his sword and cry Magna Farta".[195] In a 2005 speech the Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales, Lord Woolf, repeated the claim that Cromwell had referred to Magna Carta as "Magna Farta".[196]

The radical groups that flourished during this period held differing opinions of Magna Carta. The Levellers rejected history and law as presented by their contemporaries, holding instead to an "anti-Normanism" viewpoint.[197] John Lilburne, for example, argued that Magna Carta contained only some of the freedoms that had supposedly existed under the Anglo-Saxons before being crushed by the Norman yoke.[198] The Leveller Richard Overton described the charter as "a beggarly thing containing many marks of intolerable bondage".[199]

Both saw Magna Carta as a useful declaration of liberties that could be used against governments they disagreed with.[200] Gerrard Winstanley, the leader of the more extreme Diggers, stated "the best lawes that England hath, [viz., Magna Carta] were got by our Forefathers importunate petitioning unto the kings that still were their Task-masters; and yet these best laws are yoaks and manicles, tying one sort of people to be slaves to another; Clergy and Gentry have got their freedom, but the common people still are, and have been left servants to work for them."[201][202]

Glorious Revolution

The first attempt at a proper historiography was undertaken by Robert Brady,[203] who refuted the supposed antiquity of Parliament and belief in the immutable continuity of the law. Brady realised that the liberties of the Charter were limited and argued that the liberties were the grant of the King. By putting Magna Carta in historical context, he cast doubt on its contemporary political relevance;[204] his historical understanding did not survive the Glorious Revolution, which, according to the historian J. G. A. Pocock, "marked a setback for the course of English historiography."[205]

According to the Whig interpretation of history, the Glorious Revolution was an example of the reclaiming of ancient liberties. Reinforced with Lockean concepts, the Whigs believed England's constitution to be a social contract, based on documents such as Magna Carta, the Petition of Right, and the Bill of Rights.[206] The English Liberties (1680, in later versions often British Liberties) by the Whig propagandist Henry Care (d. 1688) was a cheap polemical book that was influential and much-reprinted, in the American colonies as well as Britain, and made Magna Carta central to the history and the contemporary legitimacy of its subject.[207]

Ideas about the nature of law in general were beginning to change. In 1716, the Septennial Act was passed, which had a number of consequences. First, it showed that Parliament no longer considered its previous statutes unassailable, as it provided for a maximum parliamentary term of seven years, whereas the Triennial Act (1694) (enacted less than a quarter of a century previously) had provided for a maximum term of three years.[208]

It also greatly extended the powers of Parliament. Under this new constitution, monarchical absolutism was replaced by parliamentary supremacy. It was quickly realised that Magna Carta stood in the same relation to the King-in-Parliament as it had to the King without Parliament. This supremacy would be challenged by the likes of Granville Sharp. Sharp regarded Magna Carta as a fundamental part of the constitution, and maintained that it would be treason to repeal any part of it. He also held that the Charter prohibited slavery.[209]

Sir William Blackstone published a critical edition of the 1215 Charter in 1759, and gave it the numbering system still used today.[210] In 1763, Member of Parliament John Wilkes was arrested for writing an inflammatory pamphlet, No. 45, 23 April 1763; he cited Magna Carta continually.[211] Lord Camden denounced the treatment of Wilkes as a contravention of Magna Carta.[212] Thomas Paine, in his Rights of Man, would disregard Magna Carta and the Bill of Rights on the grounds that they were not a written constitution devised by elected representatives.[213]

Use in the Thirteen Colonies and the United States

When English colonists left for the New World, they brought royal charters that established the colonies. The Massachusetts Bay Company charter, for example, stated that the colonists would "have and enjoy all liberties and immunities of free and natural subjects."[214] The Virginia Charter of 1606, which was largely drafted by Sir Edward Coke, stated that the colonists would have the same "liberties, franchises and immunities" as people born in England.[215] The Massachusetts Body of Liberties contained similarities to clause 29 of Magna Carta; when drafting it, the Massachusetts General Court viewed Magna Carta as the chief embodiment of English common law.[216] The other colonies would follow their example. In 1638, Maryland sought to recognise Magna Carta as part of the law of the province, but the request was denied by Charles I.[217]

In 1687, William Penn published The Excellent Privilege of Liberty and Property: being the birth-right of the Free-Born Subjects of England, which contained the first copy of Magna Carta printed on American soil. Penn's comments reflected Coke's, indicating a belief that Magna Carta was a fundamental law.[218] The colonists drew on English law books, leading them to an anachronistic interpretation of Magna Carta, believing that it guaranteed trial by jury and habeas corpus.[219]

The development of parliamentary supremacy in the British Isles did not constitutionally affect the Thirteen Colonies, which retained an adherence to English common law, but it directly affected the relationship between Britain and the colonies.[220] When American colonists fought against Britain, they were fighting not so much for new freedom, but to preserve liberties and rights that they believed to be enshrined in Magna Carta.[221]

In the late 18th century, the United States Constitution became the supreme law of the land, recalling the manner in which Magna Carta had come to be regarded as fundamental law.[221] The Constitution's Fifth Amendment guarantees that "no person shall be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law", a phrase that was derived from Magna Carta.[222] In addition, the Constitution included a similar writ in the Suspension Clause, Article 1, Section 9: "The privilege of the writ of habeas corpus shall not be suspended, unless when in cases of rebellion or invasion, the public safety may require it."[223]

Each of these proclaim that no person may be imprisoned or detained without evidence that he or she committed a crime. The Ninth Amendment states that "The enumeration in the Constitution, of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people." The writers of the U.S. Constitution wished to ensure that the rights they already held, such as those that they believed were provided by Magna Carta, would be preserved unless explicitly curtailed.[224][225]

The U.S. Supreme Court has explicitly referenced Edward Coke's analysis of Magna Carta as an antecedent of the Sixth Amendment's right to a speedy trial.[226]

19th–21st centuries

Interpretation

Initially, the Whig interpretation of Magna Carta and its role in constitutional history remained dominant during the 19th century. The historian William Stubbs's Constitutional History of England, published in the 1870s, formed the high-water mark of this view.[228] Stubbs argued that Magna Carta had been a major step in the shaping of the English nation, and he believed that the barons at Runnymede in 1215 were not just representing the nobility, but the people of England as a whole, standing up to a tyrannical ruler in the form of King John.[228][229]

This view of Magna Carta began to recede. The late-Victorian jurist and historian Frederic William Maitland provided an alternative academic history in 1899, which began to return Magna Carta to its historical roots.[230] In 1904, Edward Jenks published an article entitled "The Myth of Magna Carta", which undermined the previously accepted view of Magna Carta.[231] Historians such as Albert Pollard agreed with Jenks in concluding that Edward Coke had largely "invented" the myth of Magna Carta in the 17th century; these historians argued that the 1215 charter had not referred to liberty for the people at large, but rather to the protection of baronial rights.[232]

This view also became popular in wider circles, and in 1930 Sellar and Yeatman published their parody on English history, 1066 and All That, in which they mocked the supposed importance of Magna Carta and its promises of universal liberty: "Magna Charter was therefore the chief cause of Democracy in England, and thus a Good Thing for everyone (except the Common People)".[233][234]

In many literary representations of the medieval past, however, Magna Carta remained a foundation of English national identity. Some authors used the medieval roots of the document as an argument to preserve the social status quo, while others pointed to Magna Carta to challenge perceived economic injustices.[230] The Baronial Order of Magna Charta was formed in 1898 to promote the ancient principles and values felt to be displayed in Magna Carta.[235] The legal profession in England and the United States continued to hold Magna Carta in high esteem; they were instrumental in forming the Magna Carta Society in 1922 to protect the meadows at Runnymede from development in the 1920s, and in 1957, the American Bar Association erected the Magna Carta Memorial at Runnymede.[222][236][237] The prominent lawyer Lord Denning described Magna Carta in 1956 as "the greatest constitutional document of all times—the foundation of the freedom of the individual against the arbitrary authority of the despot".[238]

Repeal of articles and constitutional influence

Radicals such as Sir Francis Burdett believed that Magna Carta could not be repealed,[239] but in the 19th century clauses which were obsolete or had been superseded began to be repealed. The repeal of clause 26 in 1829, by the Offences Against the Person Act 1828 (9 Geo. 4 c. 31 s. 1)[h][240] was the first time a clause of Magna Carta was repealed. Over the next 140 years, nearly the whole of Magna Carta (1297) as statute was repealed,[241] leaving just clauses 1, 9 and 29 still in force (in England and Wales) after 1969. Most of the clauses were repealed in England and Wales by the Statute Law Revision Act 1863, and in modern Northern Ireland and also in the modern Republic of Ireland by the Statute Law (Ireland) Revision Act 1872.[240]

Many later attempts to draft constitutional forms of government trace their lineage back to Magna Carta. The British dominions, Australia and New Zealand,[242] Canada[243] (except Quebec), and formerly the Union of South Africa and Southern Rhodesia, reflected the influence of Magna Carta in their laws, and the Charter's effects can be seen in the laws of other states that evolved from the British Empire.[244]

Modern legacy

Magna Carta continues to have a powerful iconic status in British society, being cited by politicians and lawyers in support of constitutional positions.[238][245] Its perceived guarantee of trial by jury and other civil liberties, for example, led to Tony Benn's reference to the debate in 2008 over whether to increase the maximum time terrorism suspects could be held without charge from 28 to 42 days as "the day Magna Carta was repealed".[246] Although rarely invoked in court in the modern era, in 2012 the Occupy London protestors attempted to use Magna Carta in resisting their eviction from St. Paul's Churchyard by the City of London. In his judgment the Master of the Rolls gave this short shrift, noting somewhat drily that although clause 29 was considered by many the foundation of the rule of law in England, he did not consider it directly relevant to the case, and that the two other surviving clauses ironically concerned the rights of the Church and the City of London and could not help the defendants.[247][248]

Magna Carta carries little legal weight in modern Britain, as most of its clauses have been repealed and relevant rights ensured by other statutes, but the historian James Holt remarks that the survival of the 1215 charter in national life is a "reflexion of the continuous development of English law and administration" and symbolic of the many struggles between authority and the law over the centuries.[249] The historian W. L. Warren has observed that "many who knew little and cared less about the content of the Charter have, in nearly all ages, invoked its name, and with good cause, for it meant more than it said".[250]

It also remains a topic of great interest to historians; Natalie Fryde characterised the charter as "one of the holiest of cows in English medieval history", with the debates over its interpretation and meaning unlikely to end.[229] In many ways still a "sacred text", Magna Carta is generally considered part of the uncodified constitution of the United Kingdom; in a 2005 speech, the Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales, Lord Woolf, described it as the "first of a series of instruments that now are recognised as having a special constitutional status".[196][251]

Magna Carta was reprinted in New Zealand in 1881 as one of the Imperial Acts in force there.[252] Clause 29 of the document remains in force as part of New Zealand law.[253]

The document also continues to be honoured in the United States as an antecedent of the United States Constitution and Bill of Rights.[254] In 1976, the UK lent one of four surviving originals of the 1215 Magna Carta to the United States for their bicentennial celebrations and also donated an ornate display case for it. The original was returned after one year, but a replica and the case are still on display in the United States Capitol Crypt in Washington, D.C.[255]

Celebration of the 800th anniversary

The 800th anniversary of the original charter occurred on 15 June 2015, and organisations and institutions planned celebratory events.[256] The British Library brought together the four existing copies of the 1215 manuscript in February 2015 for a special exhibition.[257] British artist Cornelia Parker was commissioned to create a new artwork, Magna Carta (An Embroidery), which was shown at the British Library between May and July 2015.[258] The artwork is a copy of the Wikipedia article about Magna Carta (as it appeared on the document's 799th anniversary, 15 June 2014), hand-embroidered by over 200 people.[259]

On 15 June 2015, a commemoration ceremony was conducted in Runnymede at the National Trust park, attended by British and American dignitaries.[260] On the same day, Google celebrated the anniversary with a Google Doodle.[261]

The copy held by Lincoln Cathedral was exhibited in the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C., from November 2014 until January 2015.[262] A new visitor centre at Lincoln Castle was opened for the anniversary.[263] The Royal Mint released two commemorative two-pound coins.[264][265]

In 2014, Bury St Edmunds in Suffolk celebrated the 800th anniversary of the barons' Charter of Liberties, said to have been secretly agreed there in November 1214.[266]

Content

Physical format

Numerous copies, known as exemplifications, were made of the various charters, and many of them still survive.[267] The documents were written in heavily abbreviated medieval Latin in clear handwriting, using quill pens on sheets of parchment made from sheep skin, approximately 15 by 20 inches (380 by 510 mm) across.[268][269] They were sealed with the royal great seal by an official called the spigurnel, equipped with a special seal press, using beeswax and resin.[269][270] There were no signatures on the charter of 1215, and the barons present did not attach their own seals to it.[271] The text was not divided into paragraphs or numbered clauses: the numbering system used today was introduced by the jurist Sir William Blackstone in 1759.[210]

Exemplifications

1215 exemplifications

At least thirteen original copies of the charter of 1215 were issued by the royal chancery during that year, seven in the first tranche distributed on 24 June and another six later; they were sent to county sheriffs and bishops, who were probably charged for the privilege.[272] Slight variations exist between the surviving copies, and there was probably no single "master copy".[273] Of these documents, only four survive, all held in England: two now at the British Library, one at Salisbury Cathedral, and one, the property of Lincoln Cathedral, on permanent loan to Lincoln Castle.[274] Each of these versions is slightly different in size and text, and each is considered by historians to be equally authoritative.[275]

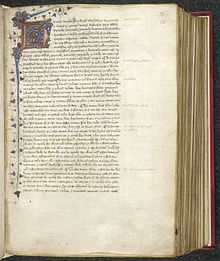

The two 1215 charters held by the British Library, known as Cotton MS. Augustus II.106 and Cotton Charter XIII.31A, were acquired by the antiquarian Sir Robert Cotton in the 17th century.[276] The first had been found by Humphrey Wyems, a London lawyer, who may have discovered it in a tailor's shop, and who gave it to Cotton in January 1629.[277] The second was found in Dover Castle in 1630 by Sir Edward Dering. The Dering charter was traditionally thought to be the copy sent in 1215 to the Cinque Ports,[278] but in 2015 the historian David Carpenter argued that it was more probably that sent to Canterbury Cathedral, as its text was identical to a transcription made from the Cathedral's copy of the 1215 charter in the 1290s.[279][280][281] This copy was damaged in the Cotton library fire of 1731, when its seal was badly melted. The parchment was somewhat shrivelled but otherwise relatively unscathed. An engraved facsimile of the charter was made by John Pine in 1733. In the 1830s, an ill-judged and bungled attempt at cleaning and conservation rendered the manuscript largely illegible to the naked eye.[282][283] This is the only surviving 1215 copy still to have its great seal attached.[284][285]

Lincoln Cathedral's copy has been held by the county since 1215. It was displayed in the Common Chamber in the cathedral, before being moved to another building in 1846.[274][286] Between 1939 and 1940 it was displayed in the British Pavilion at the 1939 World Fair in New York City, and at the Library of Congress.[287] When the Second World War broke out, Winston Churchill wanted to give the charter to the American people, hoping that this would encourage the United States, then neutral, to enter the war against the Axis powers, but the cathedral was unwilling, and the plans were dropped.[288][289]

After December 1941, the copy was stored in Fort Knox, Kentucky, for safety, before being put on display again in 1944 and returned to Lincoln Cathedral in early 1946.[287][288][290][291] It was put on display in 1976 in the cathedral's medieval library.[286] It was displayed in San Francisco, and was taken out of display for a time to undergo conservation in preparation for another visit to the United States, where it was exhibited in 2007 at the Contemporary Art Center of Virginia and the National Constitution Center in Philadelphia.[286][292][293] In 2009 it returned to New York to be displayed at the Fraunces Tavern Museum.[294] It is currently on permanent loan to the David P. J. Ross Vault at Lincoln Castle, along with an original copy of the 1217 Charter of the Forest.[295][296]

The fourth copy, held by Salisbury Cathedral, was first given in 1215 to its predecessor, Old Sarum Cathedral.[297] Rediscovered by the cathedral in 1812, it has remained in Salisbury throughout its history, except when being taken off-site for restoration work.[298][299] It is possibly the best preserved of the four, although small pin holes can be seen in the parchment from where it was once pinned up.[299][300][301] The handwriting on this version is different from that of the other three, suggesting that it was not written by a royal scribe but rather by a member of the cathedral staff, who then had it exemplified by the royal court.[267][298]

Later exemplifications

Other early versions of the charters survive today. Only one exemplification of the 1216 charter survives, held in Durham Cathedral.[302] Four copies of the 1217 charter exist; three of these are held by the Bodleian Library in Oxford and one by Hereford Cathedral.[302][303] Hereford's copy is occasionally displayed alongside the Mappa Mundi in the cathedral's chained library and has survived along with a small document called the Articuli super Cartas that was sent along with the charter, telling the sheriff of the county how to observe the conditions outlined in the document.[304] One of the Bodleian's copies was displayed at San Francisco's California Palace of the Legion of Honor in 2011.[305]

Four exemplifications of the 1225 charter survive: the British Library holds one, which was preserved at Lacock Abbey until 1945; Durham Cathedral also holds a copy, with the Bodleian Library holding a third.[303][306][307] The fourth copy of the 1225 exemplification was held by the museum of the Public Record Office and is now held by The National Archives.[308][309] The Society of Antiquaries also holds a draft of the 1215 charter (discovered in 2013 in a late-13th-century register from Peterborough Abbey), a copy of the 1225 third re-issue (within an early-14th-century collection of statutes) and a roll copy of the 1225 reissue.[310]

Only two exemplifications of Magna Carta are held outside England, both from 1297. One of these was purchased in 1952 by the Australian Government for £12,500 from King's School, Bruton, England.[311] This copy is now on display in the Members' Hall of Parliament House, Canberra.[312] The second was originally held by the Brudenell family, earls of Cardigan, before they sold it in 1984 to the Perot Foundation in the United States, which in 2007 sold it to U.S. businessman David Rubenstein for US$21.3 million.[313][314][315] Rubenstein commented "I have always believed that this was an important document to our country, even though it wasn't drafted in our country. I think it was the basis for the Declaration of Independence and the basis for the Constitution". This exemplification is now on permanent loan to the National Archives in Washington, D.C.[316][317] Only two other 1297 exemplifications survive,[318] one of which is held in the UK's National Archives,[319] the other in the Guildhall, London.[318]

Seven copies of the 1300 exemplification by Edward I survive,[318][320] in Faversham,[321] Oriel College, Oxford, the Bodleian Library, Durham Cathedral, Westminster Abbey, the City of London (held in the archives at the London Guildhall[322]) and Sandwich (held in the Kent County Council archives). The Sandwich copy was rediscovered in early 2015 in a Victorian scrapbook in the town archives of Sandwich, Kent, one of the Cinque Ports.[320] In the case of the Sandwich and Oriel College exemplifications, the copies of the Charter of the Forest originally issued with them also survive.

Clauses

Most of the 1215 charter and later versions sought to govern the feudal rights of the Crown over the barons.[323] Under the Angevin kings, and in particular during John's reign, the rights of the King had frequently been used inconsistently, often in an attempt to maximise the royal income from the barons. Feudal relief was one way that a king could demand money, and clauses 2 and 3 fixed the fees payable when an heir inherited an estate or when a minor came of age and took possession of his lands.[323]

Scutage was a form of medieval taxation. All knights and nobles owed military service to the Crown in return for their lands, which theoretically belonged to the King. Many preferred to avoid this service and offer money instead. The Crown often used the cash to pay for mercenaries.[324] The rate of scutage that should be payable, and the circumstances under which it was appropriate for the King to demand it, was uncertain and controversial. Clauses 12 and 14 addressed the management of the process.[323]

The English judicial system had altered considerably over the previous century, with the royal judges playing a larger role in delivering justice across the country. John had used his royal discretion to extort large sums of money from the barons, effectively taking payment to offer justice in particular cases, and the role of the Crown in delivering justice had become politically sensitive among the barons. Clauses 39 and 40 demanded due process be applied in the royal justice system, while clause 45 required that the King appoint knowledgeable royal officials to the relevant roles.[325]

Although these clauses did not have any special significance in the original charter, this part of Magna Carta became singled out as particularly important in later centuries.[325] In the United States, for example, the Supreme Court of California interpreted clause 45 in 1974 as establishing a requirement in common law that a defendant faced with the potential of incarceration be entitled to a trial overseen by a legally trained judge.[326]

Royal forests were economically important in medieval England and were both protected and exploited by the Crown, supplying the King with hunting grounds, raw materials, and money.[327][328] They were subject to special royal jurisdiction and the resulting forest law was, according to the historian Richard Huscroft, "harsh and arbitrary, a matter purely for the King's will".[327] The size of the forests had expanded under the Angevin kings, an unpopular development.[329]

The 1215 charter had several clauses relating to the royal forests. Clauses 47 and 48 promised to deforest the lands added to the forests under John and investigate the use of royal rights in this area, but notably did not address the forestation of the previous kings, while clause 53 promised some form of redress for those affected by the recent changes, and clause 44 promised some relief from the operation of the forest courts.[330] Neither Magna Carta nor the subsequent Charter of the Forest proved entirely satisfactory as a way of managing the political tensions arising in the operation of the royal forests.[330]

Some of the clauses addressed wider economic issues. The concerns of the barons over the treatment of their debts to Jewish moneylenders, who occupied a special position in medieval England and were by tradition under the King's protection, were addressed by clauses 10 and 11.[331] The charter concluded this section with the phrase "debts owing to other than Jews shall be dealt with likewise", so it is debatable to what extent the Jews were being singled out by these clauses.[332] Some issues were relatively specific, such as clause 33 which ordered the removal of all fishing weirs—an important and growing source of revenue at the time—from England's rivers.[330]

The role of the English Church had been a matter for great debate in the years prior to the 1215 charter. The Norman and Angevin kings had traditionally exercised a great deal of power over the church within their territories. From the 1040s onwards successive popes had emphasised the importance of the church being governed more effectively from Rome, and had established an independent judicial system and hierarchical chain of authority.[333] After the 1140s, these principles had been largely accepted within the English church, even if accompanied by an element of concern about centralising authority in Rome.[334][335]

These changes brought the customary rights of lay rulers such as John over ecclesiastical appointments into question.[334] As described above, John had come to a compromise with Pope Innocent III in exchange for his political support for the King, and clause 1 of Magna Carta prominently displayed this arrangement, promising the freedoms and liberties of the church.[323] The importance of this clause may also reflect the role of Archbishop Langton in the negotiations: Langton had taken a strong line on this issue during his career.[323]

Clauses in detail

Clauses remaining in English law

Only three clauses of Magna Carta still remain on statute in England and Wales.[245] These clauses concern 1) the freedom of the English Church, 2) the "ancient liberties" of the City of London (clause 13 in the 1215 charter, clause 9 in the 1297 statute), and 3) a right to due legal process (clauses 39 and 40 in the 1215 charter, clause 29 in the 1297 statute).[245] In detail, these clauses (using the numbering system from the 1297 statute) state that:

- I. FIRST, We have granted to God, and by this our present Charter have confirmed, for Us and our Heirs for ever, that the Church of England shall be free, and shall have all her whole Rights and Liberties inviolable. We have granted also, and given to all the Freemen of our Realm, for Us and our Heirs for ever, these Liberties under-written, to have and to hold to them and their Heirs, of Us and our Heirs for ever.

- IX. THE City of London shall have all the old Liberties and Customs which it hath been used to have. Moreover We will and grant, that all other Cities, Boroughs, Towns, and the Barons of the Five Ports, as with all other Ports, shall have all their Liberties and free Customs.

- XXIX. NO Freeman shall be taken or imprisoned, or be disseised of his Freehold, or Liberties, or free Customs, or be outlawed, or exiled, or any other wise destroyed; nor will We not pass upon him, nor condemn him, but by lawful judgment of his Peers, or by the Law of the land. We will sell to no man, we will not deny or defer to any man either Justice or Right.[240][339]

See also

- Civil liberties in the United Kingdom

- Charter of the Forest

- Fundamental Laws of England

- Haandfæstning

- History of democracy

- History of human rights

- List of most expensive books and manuscripts

- Magna Carta Hiberniae – an issue of the English Magna Carta, or Great Charter of Liberties in Ireland

- Statutes of Mortmain

Notes

- I.e., section 1 of the 31st statute issued in the 9th year of George IV; "nor will We not" in clause 29 is correctly quoted from this source.

References

The sarcasm of the Master of the Rolls was plain

May we give you – at least as a token of our feelings – something of no intrinsic value whatever: a bit of parchment, more than seven hundred years old, rather the worse for wear.

The words "We will sell to no man" were intended to abolish the fines demanded by King John in order to obtain justice. "Will not deny" referred to the stopping of suits and the denial of writs. "Delay to any man" meant the delays caused either by the counter-fines of defendants, or by the prerogative of the King.

- Hindley 1990, p. 201.

Bibliography

- Aurell, Martin (2003). L'Empire de Plantagenêt, 1154–1224 (in French). Paris: Tempus. ISBN 978-2262022822.

- Barnes, Thomas Garden (2008). Shaping the Common Law: From Glanvill to Hale, 1188–1688. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0804779593.

- Black, Charles (1999). A New Birth of Freedom: Human Rights, Named and Unnamed. New Haven, CN: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300077346.

- Breay, Claire (2010). Magna Carta: Manuscripts and Myths. London: The British Library. ISBN 978-0712358330.

- Breay, Claire; Harrison, Julian, eds. (2015). Magna Carta: Law, Liberty, Legacy. London: The British Library. ISBN 978-0712357647.

- Browning, Charles Henry (1898). "The Magna Charta Described". The Magna Charta Barons and Their American Descendants with the Pedigrees of the Founders of the Order of Runnemede Deduced from the Sureties for the Enforcement of the Statutes of the Magna Charta of King John. Philadelphia. OCLC 9378577.

- Burdett, Francis (1810). Sir Francis Burdett to His Constituents. R. Bradshaw.

- Carpenter, David A. (1990). The Minority of Henry III. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0413623607.

- Carpenter, David (1996). The Reign of Henry III. London: Hambledon Press. ISBN 978-1852851378.

- Carpenter, David A. (2004). Struggle for Mastery: The Penguin History of Britain 1066–1284. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0140148244.

- Clanchy, Michael T. (1997). Early Medieval England. The Folio Society.

- Clark, David (2000). "The Icon of Liberty: The Status and Role of Magna Carta in Australian and New Zealand Law". Melbourne University Law Review. 24 (3).

- Cobbett, William; Howell, Thomas Bayly; Howell, Th.J.; Jardine, William (1810). Cobbett's Complete Collection of State Trials and Proceedings for High Treason and Other Crimes and Misdemeanors from the Earliest Period to the Present Time. Bagshaw.

- Crouch, David (1996). William Marshal: Court, Career and Chivalry in the Angevin Empire 1147–1219. Longman. ISBN 978-0582037861.

- Danziger, Danny; Gillingham, John (2004). 1215: The Year of Magna Carta. Hodder Paperbacks. ISBN 978-0340824757.