| Rape |

|---|

| Types |

| Effects and motivations |

| By country |

| During conflicts |

| Laws |

| Related articles |

|

Rape and revenge films are a subgenre of exploitation film that was particularly popular in the 1970s, but attracted controversy as a target of extreme cinema.

Explanation of the subgenre

Rape and revenge films generally follow the same three-act structure:[citation needed]

- Act I: The character is (violently) raped and maybe further abused, tortured or left for dead.

- Act II: The character survives and may rehabilitate themselves.

- Act III: The character exacts revenge and/or kills their rapist(s).

In Gaspar Noé's 2002 film Irréversible, the structure was reversed, with the first act depicting the revenge before tracing back the events which led to that point. Roger Ebert argues that, by using this structure as well as a false revenge, Irréversible cannot be classified as an exploitation film, as no exploitation of the subject matter takes place.[1]

In popular culture

- The genre has attracted critical attention.[2][3][4][5] Much of this critical attention comes from feminist critics examining the complex politics involved in the genre and its impact on cinema more generally. More recently, a broad analysis of the rape-revenge genre and concept was published in Rape-Revenge Films: A Critical Study, by Alexandra Heller-Nicholas. The book argues against a simplistic notion of the term "rape-revenge" and suggests a film-specific approach in order to avoid generalizing films which may "diverge not over the treatment of sexual assault as much as they do in regard to the morality of the revenge act."[6]

- In addition to American and French films, rape/revenge films have been made in Japan (e.g., Takashi Ishii's Freeze Me), Finland,[7] Russia (The Voroshilov Sharpshooter), Argentina (e.g., I'll Never Die Alone; [2008]; original title: No Moriré Sola), Norway (e.g., The Whore [2009]; original title: Hora, and Sweden (e.g., The Virgin Spring [1960]; original title: Jungfrukällan which also won the Oscar for best foreign film at the 33rd Academy Awards.))

See also

References

- Makela, Anna. "Political rape, private revenge. The story of sexual violence in Finnish Film and Television". Archived from the original on September 7, 2004. Retrieved 2010-01-25.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rape_and_revenge_film

Category:Exploitation films

| Pages in this category should be moved to subcategories where applicable. This category may require frequent maintenance to avoid becoming too large. It should directly contain very few, if any, pages and should mainly contain subcategories. |

Subcategories

This category has the following 19 subcategories, out of 19 total.

- Exploitation films by decade (11 C)

A

B

- Bruceploitation (3 C, 8 P)

C

- Canadian exploitation films (1 C, 5 P)

F

- French exploitation films (8 P)

H

- Hong Kong exploitation films (1 P)

I

- Italian exploitation films (1 C, 21 P)

J

- Japanese exploitation films (1 P)

M

- Mondo films (30 P)

N

- Nazi exploitation films (18 P)

O

- Outlaw biker films (72 P)

R

- Redsploitation (9 P)

S

- Spaghetti Western (5 C, 2 P)

T

- Teensploitation (1 C, 98 P)

Σ

- Exploitation film stubs (140 P)

Pages in category "Exploitation films"

The following 30 pages are in this category, out of 30 total. This list may not reflect recent changes.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Exploitation_films

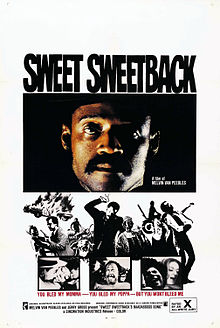

Poster of the iconic Blaxploitation film Sweet Sweetback's Baadasssss Song (1971) | |

| Years active | 1970s |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Major figures | |

| Influences | |

| Influenced | |

Blaxploitation is an ethnic subgenre of the exploitation film that emerged in the United States during the early 1970s. The term, a portmanteau of the words "black" and "exploitation", was coined in August 1972 by Junius Griffin, the president of the Beverly Hills–Hollywood NAACP branch. He claimed the genre was "proliferating offenses" to the black community in its perpetuation of stereotypes often involved in crime.[1] The genre does rank among the first after the race films in the 1940s and 1960s in which black characters and communities are the protagonists and subjects of film and television, rather than sidekicks, antagonists or victims of brutality.[2] The genre's inception coincides with the rethinking of race relations in the 1970s.

Blaxploitation films were originally aimed at an urban African-American audience but the genre's audience appeal soon broadened across racial and ethnic lines.[3] Hollywood realized the potential profit of expanding the audiences of blaxploitation films.

Variety credited Sweet Sweetback's Baadasssss Song and the less radical Hollywood-financed film Shaft (both released in 1971) with the invention of the blaxploitation genre, although Cotton Comes to Harlem was released the prior year.[4] Blaxploitation films were also the first to feature soundtracks of funk and soul music.[5]

Description

General themes

[S]upercharged, bad-talking, highly romanticized melodramas about Harlem superstuds, the pimps, the private eyes and the pushers who more or less singlehandedly make whitey's corrupt world safe for black pimping, black private-eyeing and black pushing.

Blaxploitation films set in the Northeast or West Coast mainly take place in poor urban neighborhoods. Pejorative terms for white characters, such as "cracker" and "honky," are commonly used. Blaxploitation films set in the South often deal with slavery and miscegenation.[7][8] The genre's films are often bold in their statements and use violence, sex, drug trafficking and other shocking qualities to provoke the audience.[2] The films usually portray black protagonists overcoming "The Man" or emblems of the white majority that oppresses the black community.

Blaxploitation includes several subtypes, including crime (Foxy Brown), action/martial arts (Three the Hard Way), westerns (Boss Nigger), horror (Abby, Blacula), prison (Penitentiary), comedy (Uptown Saturday Night), nostalgia (Five on the Black Hand Side), coming-of-age (Cooley High/Cornbread, Earl and Me), and musical (Sparkle).

Following the example set by Sweet Sweetback's Baadasssss Song, many blaxploitation films feature funk and soul jazz soundtracks with heavy bass, funky beats and wah-wah guitars. These soundtracks are notable for complexity that was not common to the radio-friendly funk tracks of the 1970s. They also often feature a rich orchestration which included flutes and violins.[9]

Following the popularity of these films in the 1970s, movies within other genres began to feature black characters with stereotypical blaxploitation characteristics, such as the Harlem underworld characters in the James Bond film Live and Let Die (1973), Jim Kelly's character in Enter the Dragon (1973) and Fred Williamson's character in The Inglorious Bastards (1978).

Black Power

Afeni Shakur claimed that every aspect of culture (including cinema) in the 1960s and 1970s was influenced by the Black Power movement. Sweet Sweetback's Baadasssss Song was one of the first films to incorporate black power ideology and permit black actors to be the stars of their own narratives, rather than being relegated to the typical roles available to them (such as the "mammy" figure and other low-status characters).[10][11] Films such as Shaft brought the black experience to film in a new way, allowing black political and social issues that had been ignored in cinema to be explored. Shaft and its protagonist, John Shaft, brought African American culture to the mainstream world.[11] Sweetback and Shaft were both influenced by the black power movement, containing Marxist themes, solidarity and social consciousness alongside the genre-typical images of sex and violence.

Knowing that film could bring about social and cultural change, the Black Power movement seized the genre to highlight black socioeconomic struggles in the 1970s; many such films contained black heroes who were able to overcome the institutional oppression of African American culture and history.[2] Later films such as Super Fly softened the rhetoric of black power, encouraging resistance within the capitalist system rather than a radical transformation of society. Super Fly still embraced the black nationalist movement in its argument that black and white authority cannot coexist easily.

Stereotypes

The genre's role in exploring and shaping race relations in the United States has been controversial. Some held that the blaxploitation trend was a token of black empowerment but others accused the movies of perpetuating common white stereotypes about black people.[12] As a result, many called for the end of the genre. The NAACP, Southern Christian Leadership Conference and National Urban League joined to form the Coalition Against Blaxploitation. Their influence in the late 1970s contributed to the genre's demise. Literary critic Addison Gayle wrote in 1974, "The best example of this kind of nihilism / irresponsibility are the Black films; here is freedom pushed to its most ridiculous limits; here are writers and actors who claim that freedom for the artist entails exploitation of the very people to whom they owe their artistic existence."[13]

Films such as Super Fly and The Mack received intense criticism not only for the stereotype of the protagonist (generalizing pimps as representative of all African-American men, in this case) but for portraying all black communities as hotbeds for drugs and crime.[citation needed]

Blaxploitation films such as Mandingo (1975) provided mainstream Hollywood producers, in this case Dino De Laurentiis, a cinematic way to depict plantation slavery with all of its brutal, historical and racial contradictions and controversies, including sex, miscegenation, rebellion. The story world also depicts the plantation as one of the main origins of boxing as a sport in the U.S.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, a new wave of acclaimed black film makers, particularly Spike Lee (Do the Right Thing), John Singleton (Boyz n the Hood), and Allen and Albert Hughes (Menace II Society) focused on black urban life in their movies. These directors made use of blaxploitation elements while incorporating implicit criticism of the genre's glorification of stereotypical "criminal" behavior.

Alongside accusations of exploiting stereotypes, the NAACP also criticized the blaxploitation genre of exploiting the black community and culture of America, by creating films for a profit that those communities would never see, despite being the vastly misrepresented main focus of many blaxploitation film plots. Many film professionals still believe that there is no truly equal "Black Hollywood" as evidenced by the "Oscars So White" scandal in 2015 that caused uproar when no black actors were nominated for "Best Actor" Oscar Awards.[11]

Slavesploitation

Slavesploitation, a subgenre of blaxploitation in literature and film, flourished briefly in the late 1960s and 1970s.[14][15] As its name suggests, the genre is characterized by sensationalistic depictions of slavery.

Abrams, arguing that Quentin Tarantino's Django Unchained (2012) finds its historical roots in the slavesploitation genre, observes that slavesploitation films are characterized by "crassly exploitative representations of oppressed slave protagonists".[16]

One early antecedent of the genre is Slaves (1969), which Gaines notes was "not 'slavesploitation' in the vein of later films", but which nonetheless featured graphic depictions of beatings and sexual violence against slaves.[17] Novotny argues that Blacula (1972), although it does not depict slavery directly, is historically linked to the slavesploitation subgenre.[18]

By far the best-known and best-studied exemplar of slavesploitation is Mandingo, a 1957 novel which was adapted into a 1961 play and a 1975 film. Indeed, Mandingo was so well known that a contemporary reviewer of Die the Long Day, a 1972 novel by Orlando Patterson, called it an example of the "Mandingo genre".[19] The film, panned on its release, has been subject to widely divergent critical assessments.[20] Robin Wood, for instance, argued in 1998 that it is the "greatest film about race ever made in Hollywood, certainly prior to Spike Lee and in some respects still".[21]

Legacy

Influence

Blaxploitation films have had an enormous and complicated influence on American cinema. Filmmaker and exploitation film fan Quentin Tarantino, for example, has made numerous references to the blaxploitation genre in his films. An early blaxploitation tribute can be seen in the character of "Lite," played by Sy Richardson, in Repo Man (1984).[citation needed] Richardson later wrote Posse (1993), which is a kind of blaxploitation Western.

Some of the later, blaxploitation-influenced movies such as Jackie Brown (1997), Undercover Brother (2002), Austin Powers in Goldmember (2002), Kill Bill Vol. 1 (2003), and Django Unchained (2012) feature pop culture nods to the genre. The parody Undercover Brother, for example, stars Eddie Griffin as an afro-topped agent for a clandestine organization satirically known as the "B.R.O.T.H.E.R.H.O.O.D.". Likewise, Austin Powers in Goldmember co-stars Beyoncé Knowles as the Tamara Dobson/Pam Grier-inspired heroine, Foxxy Cleopatra. In the 1977 parody film The Kentucky Fried Movie, a mock trailer for Cleopatra Schwartz depicts another Grier-like action star married to a rabbi. In a famous scene in Reservoir Dogs, the protagonists discuss Get Christie Love!, a mid-1970s blaxploitation television series. In the catalytic scene of True Romance, the characters watch the movie The Mack.

John Singleton's Shaft (2000), starring Samuel L. Jackson, is a modern-day interpretation of a classic blaxploitation film. The 1997 film Hoodlum starring Laurence Fishburne portrays a fictional account of black mobster Ellsworth "Bumpy" Johnson and recasts gangster blaxploitation with a 1930s twist. In 2004, Mario Van Peebles released Baadasssss!, about the making of his father Melvin's movie (with Mario playing Melvin). 2007's American Gangster, based on the true story of heroin dealer Frank Lucas, takes place in the early 1970s in Harlem and has many elements similar in style to blaxploitation films, specifically its prominent featuring of the song "Across 110th Street".

Blaxploitation films have profoundly impacted contemporary hip-hop culture. Several prominent hip hop artists, including Snoop Dogg, Big Daddy Kane, Ice-T, Slick Rick, and Too Short, have adopted the no-nonsense pimp persona popularized first by ex-pimp Iceberg Slim's 1967 book Pimp and subsequently by films such as Super Fly, The Mack, and Willie Dynamite. In fact, many hip-hop artists have paid tribute to pimping within their lyrics (most notably 50 Cent's hit single "P.I.M.P.") and have openly embraced the pimp image in their music videos, which include entourages of scantily-clad women, flashy jewelry (known as "bling"), and luxury Cadillacs (referred to as "pimpmobiles"). The most famous scene of The Mack, featuring the "Annual Players Ball", has become an often-referenced pop culture icon—most recently by Chappelle's Show, where it was parodied as the "Playa Hater's Ball". The genre's overseas influence extends to artists such as Norway's hip-hop duo Madcon.[22]

In Michael Chabon's novel Telegraph Avenue, set in 2004, two characters are former blaxploitation stars.[23]

In 1980, opera director Peter Sellars (not to be confused with actor Peter Sellers) produced and directed a staging of Mozart's opera Don Giovanni in the manner of a blaxploitation film, set in contemporary Spanish Harlem, with African-American singers portraying the anti-heroes as street-thugs, killing by gunshot rather than with a sword, using recreational drugs, and partying almost naked.[24] It was later released on commercial video and can be seen on YouTube.[25]

A 2016 video game, Mafia III, is set in the year 1968 and revolves around Lincoln Clay, a mixed-race African American orphan raised by "black mob".[26] After the murder of his surrogate family at the hands of the Italian mafia, Lincoln Clay seeks vengeance on those who took away the only thing that mattered to him.

Cultural references

The notoriety of the blaxploitation genre has led to many parodies.[27] The earliest attempts to mock the genre, Ralph Bakshi's Coonskin and Rudy Ray Moore's Dolemite, date back to the genre's heyday in 1975.

Coonskin was intended to deconstruct racial stereotypes, from early minstrel show stereotypes to more recent stereotypes found in blaxploitation film itself. The work stimulated great controversy even before its release when the Congress of Racial Equality challenged it. Even though distribution was handed to a smaller distributor who advertised it as an exploitation film, it soon developed a cult following with black viewers.[4]

Dolemite, less serious in tone and produced as a spoof, centers around a sexually active black pimp played by Rudy Ray Moore, who based the film on his stand-up comedy act. A sequel, The Human Tornado, followed.

Later spoofs parodying the blaxploitation genre include I'm Gonna Git You Sucka, Pootie Tang, Undercover Brother, Black Dynamite, and The Hebrew Hammer, which featured a Jewish protagonist and was jokingly referred to by its director as a "Jewsploitation" film.

Robert Townsend's comedy Hollywood Shuffle features a young black actor who is tempted to take part in a white-produced blaxploitation film.

The satirical book Our Dumb Century features an article from the 1970s entitled "Congress Passes Anti-Blaxploitation Act: Pimps, Players Subject to Heavy Fines".

FOX's network television comedy, "MADtv", has frequently spoofed the Rudy Ray Moore-created franchise Dolemite, with a series of sketches performed by comic actor Aries Spears, in the role of "The Son of Dolemite". Other sketches include the characters "Funkenstein", "Dr. Funkenstein" and more recently Condoleezza Rice as a blaxploitation superhero. A recurring theme in these sketches is the inexperience of the cast and crew in the blaxploitation era, with emphasis on ridiculous scripting and shoddy acting, sets, costumes, and editing. The sketches are testaments to the poor production quality of the films, with obvious boom mike appearances and intentionally poor cuts and continuity.

Another of FOX's network television comedies, "Martin" starring Martin Lawrence, frequently references the blaxploitation genre. In the Season Three episode "All The Players Came", when Martin organizes a "Player's Ball" charity event to save a local theater, several stars of the blaxploitation era, such as Rudy Ray Moore, Antonio Fargas, Dick Anthony Williams and Pam Grier all make cameo appearances. In one scene, Martin, in character as aging pimp "Jerome", refers to Pam Grier as "Sheba, Baby" in reference to her 1975 blaxploitation feature film of the same name.

In the movie Leprechaun in the Hood, a character played by Ice-T pulls a baseball bat from his Afro. This scene alludes to a similar scene in Foxy Brown, in which Pam Grier hides a small semi-automatic pistol in her Afro.

Adult Swim's Aqua Teen Hunger Force series has a recurring character called "Boxy Brown" - a play on Foxy Brown. An imaginary friend of Meatwad, Boxy Brown is a cardboard box with a crudely drawn face with a French cut that dons an afro. Whenever Boxy speaks, '70s funk music, typical of blaxploitation films, plays in the background. The cardboard box also has a confrontational attitude and dialect similar to many heroes of this film genre.

Some of the TVs found in the action video game Max Payne 2: The Fall of Max Payne feature a Blaxploitation-themed parody of the original Max Payne game called Dick Justice, after its main character. Dick behaves much like the original Max Payne (down to the "constipated" grimace and metaphorical speech) but wears an afro and mustache and speaks in Ebonics.

Duck King, a fictional character created for the video game series Fatal Fury, is a prime example of foreign black stereotypes.

The sub-cult movie short Gayniggers from Outer Space is a blaxploitation-like science fiction oddity directed by Danish filmmaker, DJ, and singer Morten Lindberg.

Jefferson Twilight, a character in The Venture Bros., is a parody of the comic-book character Blade (a black, half human, half-vampire vampire hunter), as well as a blaxploitation reference. He has an afro, sideburns, and a mustache. He carries swords, dresses in stylish 1970s clothing, and says that he hunts "Blaculas". He looks and sounds like Samuel L. Jackson.[citation needed]

A scene from the Season 9 episode of The Simpsons, Simpson Tide", shows Homer Simpson watching "Exploitation Theatre." A voice-over announces the fake movie titles such as "The Blunch Black of Blotre Blame."

Martha Southgate's 2005 novel Third Girl from the Left is set in Hollywood during the era of blaxploitation films and references many blaxploitation films and stars such as Pam Grier and Coffy.

Notable blaxploitation films

1968

- Uptight (film) a 1968 American drama film directed by Jules Dassin. It was intended as an updated version of John Ford's 1935 film The Informer, based on the book of the same name by Liam O'Flaherty, but the setting was transposed from Dublin to Cleveland. The soundtrack was performed by Booker T. & the MG's. This movie follows the story of a Black nationalist organization in Cleveland (largely based in the Hough and Glenville neighborhoods) who becomes disillusioned with non-violence after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr and prepares for urban guerilla warfare.

1970

- The Black Angels is about a black motorcycle gang and is part of the outlaw biker film genre.

- They Call Me MISTER Tibbs! A sequel to In the Heat of the Night, it is a pre-Shaft blaxploitation, and stylistically different from the original film.

- Carter's Army is a television film about a unit of black soldiers in World War II.

- Cotton Comes to Harlem (dir. Ossie Davis) is based on a novel by Chester Himes. Features two black NYPD detectives, Coffin Ed Johnson (Raymond St. Jacques) and Gravedigger Jones (Godfrey Cambridge), on the hunt for a money-filled cotton bale stolen by a corrupt reverend named Deke O'Malley.

1971

- Sweet Sweetback's Baadasssss Song is written, produced, scored, directed by and stars Melvin Van Peebles. The hero, named Sweetback because of his sexual powers, is an apolitical sex worker. His pimp, Beadle, makes a deal with a couple of police officers to let them take Sweetback into the station so it looks like the cops are picking up suspects. While Sweetback is in custody, the police arrest a young black militant and take him to a rural area to torture him. Sweetback steps in and beats the police unconscious. With the police chasing him, Sweetback comes to understand the power of the black community sticking together. He uses his ingenuity and survival skills to outwit the police and escape to Mexico.[28] Music by Earth Wind & Fire.

- Shaft (dir. Gordon Parks) features Richard Roundtree as detective John Shaft. The soundtrack features contributions from Isaac Hayes, whose recording of the titular song won several awards, including an Academy Award. Shaft was deemed culturally relevant by the Library of Congress, and it spawned two sequels, Shaft's Big Score (1972) and Shaft in Africa (1973), as well as a short-lived TV series starring Roundtree.[29] The concept was revived in 2000 with an all-new sequel starring Samuel L. Jackson as the nephew of the original John Shaft, with Roundtree reprising his role as the original Shaft. A direct sequel to the 2000 film was released in 2019, also titled Shaft.

- The Bus Is Coming is a 1971 American drama film about a young black soldier who returns home to Los Angeles from combat in Vietnam to find out that his brother had been killed by a gang of racist cops. He struggles between maintaining his beliefs surrounding liberalism and centrism, or being radicalized from his brothers death, and possibly joining the Black nationalist organization the Black Fist. This movie was directed by Wendell James Franklin and starred Mike B. Simms and, Burl Bullock.

1972

- Come Back, Charleston Blue, starring Godfrey Cambridge and Raymond St. Jacques, loosely based on Chester Himes' novel The Heat's On. It is a sequel to the 1970 film Cotton Comes to Harlem. All tracks written by Donny Hathaway except "Little Ghetto Boy"

- Hit Man (dir. George Armitage) is the story of an Oakland hit man, played by former NFL player Bernie Casey, who comes to Los Angeles after his brother is murdered. He learns that his niece has been forced into pornography. She is eventually murdered. He sets out to murder everyone directly involved, from a porn star (Pam Grier), to a theater owner (Ed Cambridge), to a man he looked up to as a child (Rudy Challenger), and a mobster (Don Diamond).

- Super Fly (dir. Gordon Parks Jr.) features a soundtrack by Curtis Mayfield. Super Fly is one of the most controversial, profitable and popular classics of the genre.[30]

- The Legend of Nigger Charley (dir. Martin Goldman) is written by, co-produced by and stars Fred Williamson. It was followed by the sequel The Soul of Nigger Charley (1973).

- Hammer (dir. Bruce D. Clark) stars Fred Williamson as B.J. Hammer, a boxer who gets mixed up with a crooked manager who wants him to throw a fight for the Mafia.

- Across 110th Street (dir. Barry Shear) is a crime thriller about two detectives (played by Anthony Quinn and Yaphet Kotto) who try to catch a group of robbers who stole $300,000 from the Mob before the Mob catches up with them. The title track by Bobby Womack reached #19 on the Billboard Black Singles Chart.

- Black Mama, White Mama is a women in prison film partly inspired by The Defiant Ones (1958) starring Pam Grier and Margaret Markov in the roles originated by Sidney Poitier and Tony Curtis.

- Blacula is a take on Dracula which features an African prince (played by William H. Marshall) who is bitten and imprisoned by Count Dracula. Once freed from his coffin, he spreads terror in modern-day Los Angeles.

- Melinda (dir. Hugh Robertson) features music by Jerry Peters and Jerry Butler.[31]

- Slaughter stars Jim Brown as an ex-Green Beret who seeks revenge against a crime syndicate for the murder of his parents. It spawned the sequel, Slaughter's Big Rip-Off (1973).

- Trouble Man stars Robert Hooks as "Mr. T.", a hard-edged private detective who tends to take justice into his own hands. Although the film itself was unsuccessful, it did enjoy a successful soundtrack written, produced and performed by Motown artist Marvin Gaye.

- The Final Comedown (dir. Oscar Williams) features music by Grant Green and Wade Marcus, and stars Billy Dee Williams. The film is an examination of racism in the United States and depicts a shootout between a radical black nationalist group and the police, with the backstory leading up to the shootout told through flashbacks.

- Black Gunn is a 1972 American neo-noir crime thriller film, directed by Robert Hartford-Davis and starring Jim Brown, Martin Landau, Brenda Sykes, Herbert Jefferson Jr. and Luciana Paluzzi. The film is considered an entry blaxploitation sub-genre, but is unique to the genre in several different ways. The film is set in Los Angeles where a nighttime robbery of an illegal mafia bookmaking operation is carried out by the militant African-American organization BAG (Black Action Group). Though successful, several of the bookmakers and one of the burglars are killed. The mastermind behind the robbery, a Vietnam veteran named Scott, is the brother of a prominent nightclub owner, Gunn. Seeking safe haven, Scott hides out at his brother's mansion after a brief reunion.

1973

- Black Caesar, Tommy Gibbs (Fred Williamson) is a street-smart hoodlum who has worked his way up to being the crime boss of Harlem. Music by James Brown.

- Blackenstein is a parody of Frankenstein and features a black Frankenstein's monster.

- Cleopatra Jones (1973) and its sequel, Cleopatra Jones and the Casino of Gold (1975), star Tamara Dobson as a karate-chopping government agent, with the mutual support of the Black Nationalist B&S (Brothers & Sisters) House. The first film marks the beginning of a subgenre of blaxploitation films focusing on strong female leads taking an active role in shootouts and fights. Some of these films include Coffy, Black Belt Jones, Foxy Brown and T.N.T. Jackson.

- Coffy, Pam Grier stars as Coffy, a nurse turned vigilante who takes revenge on all those who hooked her 11-year-old sister on heroin. Coffy marks Grier's biggest hit and was re-worked for Foxy Brown, Friday Foster and Sheba Baby.

- Detroit 9000 is set in Detroit, MI and features street-smart white detective Danny Bassett (Alex Rocco) who teams with educated black detective Sgt. Jesse Williams (Hari Rhodes) to investigate the theft of $400,000 at a fund-raiser for Representative Aubrey Hale Clayton (Rudy Challenger). Championed by Quentin Tarantino, it was released on video by Miramax in April 1999.

- Gordon's War stars Paul Winfield as a Vietnam vet who recruits ex-Army buddies to fight the Harlem drug dealers and pimps responsible for the heroin-fueled death of his wife.

- Live and Let Die, a James Bond movie directed by Guy Hamilton and starring Roger Moore. Many of the villains and allies are based on stock blaxploitation characters.

- The Mack is a film starring Max Julien and Richard Pryor.[32] It was produced during the era of such Blaxploitations as Dolemite. It is not considered by its makers a true blaxploitation picture. It is more a social commentary according to Mackin' Ain't Easy, a documentary about the making of The Mack, which can be found on the DVD edition of the film. The movie tells the story of the life of John Mickens (a.k.a. Goldie), a former drug dealer recently released from prison who becomes a big-time pimp. Standing in his way is another pimp: Pretty Tony. Two corrupt white cops, a local crime lord, and his own brother (a black nationalist), all try to force him out of the business. Set in Oakland, California, it was the highest grossing blaxploitation of its time. Its soundtrack was recorded by Motown artist Willie Hutch.

- Scream Blacula Scream is the sequel to Blacula. William H. Marshall reprises his role as Blacula/Mamuwalde.

- The Spook Who Sat By the Door is adapted from Sam Greenlee's novel and directed by Ivan Dixon with music by Herbie Hancock. A token black CIA employee, who is secretly a black nationalist, leaves his position to train a street gang in CIA tactics and guerilla warfare to become an army of "freedom fighters". The film was reportedly pulled from distribution because of its politically controversial message and depictions of an American race war. Until its 2004 DVD release, it was hard to find, save for infrequent bootleg VHS copies. In 2012, the film was included in the USA Library of Congress National Film Registry.[33]

- Superfly TNT (dir. Ron O'Neil)

- That Man Bolt, starring Fred Williamson, is the first spy film in this genre, combining elements of James Bond with martial arts action in an international setting.

- Trick Baby is based on the book of the same name by ex-pimp Iceberg Slim.

- Hell Up in Harlem is the sequel to Black Caesar and stars Fred Williamson and Gloria Hendry, with a soundtrack by Motown singer Edwin Starr.

1974

- Abby is a version of The Exorcist and stars Carol Speed as a virtuous young woman possessed by a demon. Ms. Speed also sings the title song. William H. Marshall (of Blacula fame) conducts the exorcism of Abby on the floor of a discotheque. A hit in its time, it was later pulled from the theaters after Warner Bros. successfully sued AIP over copyright issues.

- Black Belt Jones, Jim Kelly, who is better known for his role as "Mister Williams" in the Bruce Lee film Enter the Dragon, is given a leading role. He plays Black Belt Jones, a federal agent/martial arts expert who takes on the mob as he avenges the murder of a karate school owner.

- Black Eye is an action-mystery starring Fred Williamson as a private detective investigating murders connected with a drug ring.

- The Black Godfather stars Rod Perry as a man rising to underworld power based on The Godfather.

- The Black Six is about a black motorcycle gang seeking revenge. It combines blaxploitation and outlaw biker film.

- Foxy Brown is largely a remake of the hit film Coffy. Pam Grier once again plays a nurse on a vendetta against a drug ring, who seeks help from the Black Panthers.[34] Originally written as a sequel to Coffy, the film's working title was Burn, Coffy, Burn!. The soundtrack was recorded by Willie Hutch.

- Claudine (film): Music by Curtis Mayfield and Gladys Knight & the Pips. Cast/Diahann Carroll.[35]

- Get Christie Love! is a TV movie later released to some theaters. This police drama, starring an attractive young black woman (Teresa Graves) as an undercover cop, was later made into a short-lived TV series.

- Johnny Tough stars Dion Gossett and Renny Roker.

- Space Is the Place is a psychedelically themed blaxploitation film featuring Sun Ra & His Intergalactic Solar Arkestra.

- Sugar Hill is set in Houston and features a female fashion photographer (played by Marki Bey) who wreaks revenge on the local crime Mafia that murdered her fiancé with the use of voodoo magic.

- Three the Hard Way features three black men (Fred Williamson, Jim Kelly, and Jim Brown) who must stop a white supremacist plot to eliminate all blacks with a serum in the water supply. Directed by Gordon Parks Jr.

- Three Tough Guys stars Isaac Hayes and music by Isaac Hayes.

- TNT Jackson stars Jean Bell (one of the first black Playboy playmates) and is partly set in Hong Kong. It is notable for blending blaxploitation with the then-popular "chop-socky" martial arts genre.

- Together Brothers is set in Galveston, Texas, where a street gang solves the murder of a Galveston, TX police officer (played by Ed Bernard who has been a mentor to the gang leader). This was the first blaxploitation film to feature a transgender character as the villain. Galveston, TX native Barry White composed the score. The soundtrack features music by the Love Unlimited Orchestra.

- Truck Turner (dir. Jonathan Kaplan) stars Isaac Hayes, Yaphet Kotto and Nichelle Nichols. A former football player turned bounty hunter is pitted against a powerful prostitution crime syndicate in Los Angeles. Music by Isaac Hayes.[36]

- Willie Dynamite, Roscoe Orman (Gordon from Sesame Street fame) plays a pimp. As in many blaxploitation films, the lead character drives a customized Cadillac Eldorado Coupe (the same car was used in Magnum Force).

1975

- Sheba, Baby, a female private eye (Pam Grier) tries to help her father save his loan business from a gang of thugs.

- The Black Gestapo, Rod Perry plays General Ahmed, who has started an inner-city People's Army to try to relieve the misery of the citizens of Watts, Los Angeles. When the Mafia moves in, they establish a military-style squad.

- Boss Nigger, along with his friend Amos (D'Urville Martin), Boss Nigger (Fred Williamson) takes over the vacated position of Sheriff in a small western town in this Western blaxploitation film. Because of its controversial title, it was released in some markets as The Boss, The Black Bounty Killer or The Black Bounty Hunter.

- Coonskin (dir. Ralph Bakshi) is a controversial animated/live-action film about Br'er Fox, Br'er Rabbit and Br'er Bear in a blaxploitation parody of Disney's Song of the South. It features the voice of Barry White as Br'er Bear.

- Darktown Strutters (dir. William Witney) is a farce produced by Roger Corman's brother, Gene. A Colonel Sanders-type figure with a chain of urban fried chicken restaurants is trying to wipe out the black race by making them impotent through his drugged fried chicken.

- Dr. Black, Mr. Hyde is the retelling of the Jekyll and Hyde tale, starring Bernie Casey.

- Dolemite is also the name of its principal character, played by Rudy Ray Moore, who co-wrote the script. Moore had developed the alter-ego as a stand-up comedian and released several comedy albums using this persona. The film was directed by D'Urville Martin, who appears as the villain Willie Green. The film has attained cult status, earning it a following and making it more well-known than many of its counterparts. A sequel, The Human Tornado, was released in 1976.

- Mandingo is based on a series of lurid Civil War novels and focuses on the abuses of slavery and the sexual relations between slaves and slave owners. It features Richard Ward and Ken Norton. It was followed by a sequel, Drum (1976) starring Pam Grier.

- The Candy Tangerine Man opens with pageantry pimp Baron (John Daniels) driving his customized two-tone red and yellow Rolls-Royce around downtown L.A at night. His ladies have been coming up short lately and he wants to know why. It turns out that two L.A.P.D. cops - Dempsey and Gordon, who have been after Baron for some time now, have resorted to rousting his girls every chance they get. Indeed, in the next scene they have set Baron up with a cop in drag to entrap him with procurement of prostitutes.

- Lady Cocoa (dir. Matt Cimber) stars Lola Falana.

- Let's Do It Again, Music: Composed by Curtis Mayfield.

- Welcome Home Brother Charles. After being released from prison, a wrongfully imprisoned black man takes vengeance on those who previously crossed him by strangling them with his penis.

1976

- Black Shampoo is a take-off of the Warren Beatty hit Shampoo.

- Ebony, Ivory & Jade (dir. Cirio Santiago) (also known as She Devils in Chains, American Beauty Hostages, Foxfire, Foxforce), features three female athletes who are kidnapped during an international track meet in Hong Kong and fight their way to freedom. This is another cross-genre blend of blaxploitation and martial arts action films.

- The Muthers is another Cirio Santiago combination of Filipino martial arts action and women-in-prison elements. Jeanne Bell and Jayne Kennedy rescue prisoners held at an evil coffee plantation.

- Passion Plantation (a.k.a. Black Emmanuel, White Emmanuel) is a blend of the Mandingo and Emmanuelle, erotic films with interracial sex and savagery.

- Velvet Smooth, Johnnie Hill is a female private detective hired to infiltrate the criminal underworld.

- The Human Tornado a.k.a. Dolemite II, Rudy Ray Moore reprises his role as Dolemite in the sequel to the 1975 film Dolemite.

- J. D.'s Revenge, a club driver is possessed by a dead gangster who seeks revenge for his murder over 30 years ago.

1977

- Black Fist features a street fighter who goes to work for a white gangster and a corrupt cop. The film is in the public domain. Cast members include Richard Lawson and Dabney Coleman

- Black Samurai (dir. Al Adamson) is based on a novel of the same name by Marc Olden, and stars Jim Kelly. The script is credited to B. Readick, with additional story ideas from Marco Joachim.

- Bare Knuckles stars Robert Viharo, Sherry Jackson and Gloria Hendry. The film is written and directed by Don Edmonds and follows L.A. bounty hunter Zachary Kane (Viharo) on the hunt for a masked serial killer.

- Petey Wheatstraw (a.k.a. Petey Wheatstraw, the Devil's Son-In-Law) is written by Cliff Roquemore and stars popular blaxploitation genre comedian Rudy Ray Moore along with Jimmy Lynch, Leroy Daniels, Ernest Mayhand and Ebony Wright. It is typical of Moore's other films of the era, Dolemite and The Human Tornado, in that it features Moore's rhyming dialogue.

1978

- Death Dimension is a martial arts film directed by Al Adamson and starring Jim Kelly, Harold Sakata, George Lazenby, Terry Moore, and Aldo Ray. The film also goes by the names Death Dimensions, Freeze Bomb, Icy Death, The Kill Factor and Black Eliminator. A scientist, Professor Mason, invents a powerful freezing bomb for a gangster leader nicknamed "The Pig" (Sakata).

1979

- Disco Godfather, also known as The Avenging Disco Godfather, is an action film starring Rudy Ray Moore and Carol Speed. Moore's character, a retired cop, owns and operates a disco and tries to shut down the local angel dust dealer after his nephew becomes hooked on the drug.

- Penitentiary (dir. Jamaa Franklin) follows the travails of Martel "Too Sweet" Gordone (Leon Isaac Kennedy) after his wrongful imprisonment. Set in a prison, the film exploits all of the tropes of the genre, including violence, sexuality and the eventual triumph of the lead character.

Post-1970s Blaxploitation films

- The Last Dragon (1985) is a martial arts action film with blaxploitation elements.

- I'm Gonna Git You Sucka (1988) is a comedic spoof of classic 1970s blaxploitation and features many of its stars: Jim Brown, Bernie Casey, Antonio Fargas and Isaac Hayes.

- Action Jackson (1988) is a film where the protagonist Jericho Jackson (Carl Weathers), uses catchphrases to taunt his opponents. Craig T. Nelson, Sharon Stone and Vanity also star.

- Tales from the Hood (1995, dir. Rusty Cundiff) is a Comedy horror anthology film with Urban themes.

- Original Gangstas (1996) brings together 1970s blaxploitation stars Pam Grier, Richard Roundtree, Fred Williamson and Jim Brown.

- Jackie Brown (1997, dir. Quentin Tarantino) stars Pam Grier and Samuel L. Jackson in an homage to the blaxploitation genre. Based on the Elmore Leonard novel Rum Punch, Tarantino's title change, casting of Grier and 1970s-style poster art, are all references to Grier's 1974 film Foxy Brown.

- Pootie Tang (2001) incorporates many blaxploitation elements comedically.

- The Return of Dolemite (2002), the third chapter to the Dolemite series, later retitled as The Dolemite Explosion for the DVD release.

- Undercover Brother (2002) stars Eddie Griffin as a blaxploitation-style secret agent.

- Full Clip (2004) is made in the graphic novel style.

- Hookers In Revolt (2008, dir. Sean Weathers). With its prevalence of pimps and prostitutes, it is an inventive throwback to early 1970s blaxploitation.[37]

- Black Dynamite (2009) stars Michael Jai White and spoofs blaxploitation films.

- Proud Mary (2018) is an action thriller starring Taraji P. Henson and Danny Glover.[38]

- Get Christie Love! (2018), a made-for-TV remake of the 1974 film starring Kylie Bunbury which, unlike the original, was never picked up for a TV series.

- Superfly (2018) is a remake of the 1972 film, starring Trevor Jackson and Jason Mitchell.

- Undercover Brother 2 (2019), a sequel to the 2002 film starring Michael Jai White.

- The Harder They Fall (2021) is a Netflix Western film starring Jonathan Majors and Idris Elba.

Other

- Baadasssss! (2003), a biopic about the making of Sweet Sweetback's Baadasssss Song, starring Mario Van Peebles.

- Dolemite Is My Name (2019), a biopic about the making of Dolemite, starring Eddie Murphy as Rudy Ray Moore.

See also

- Hood film

- Race film

- Race record

- List of blaxploitation films

- List of topics related to Black and African people#Cinema and theater

- Stereotypes of African Americans#Film and television

- Post-civil rights era African-American history

References

- "Five Pam Grier Classics to Stream After 'Proud Mary'". ScreenCrush.

Further reading

- Blaxploitation Films by Mikel J. Koven, 2010, Kamera Books, ISBN 978-1-903047-58-3

- "The Rise and Fall of Blaxploitation" by Ed Guerrero, in The Wiley-Blackwell History of American Film, eds. Cynthia Lucia, Roy Grundmann, Art Simon, (New York, 2012): Vol 3, pp. 435–469, ISBN 978-1-4051-7984-3.

- What It Is ... What It Was!; The Black Film Explosion of the '70s in Words and Pictures by Andres Chavez, Denise Chavez, Gerald Martinez ISBN 0-7868-8377-4

- "The So Called Fall of Blaxploitation" by Ed Guerrero, The Velvet Light Trap #64 Fall 2009

- "Black Outlaws and the Struggle for Empowerment in Blaxploitation Cinema," by Joshua K. Wright, Spectrum: A Journal on Black Men, Vol. 2, No. 2 (Spring 2014), pp. 63–86 (24 pages), Indiana University Press on JStor.

External links

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blaxploitation

A grindhouse or action house[1] is an American term for a theatre that mainly shows low-budget horror, splatter, and exploitation films for adults. According to historian David Church, this theater type was named after the "grind policy", a film-programming strategy dating back to the early 1920s which continuously showed films at cut-rate ticket prices that typically rose over the course of each day. This exhibition practice was markedly different from the era's more common practice of fewer shows per day and graduated pricing for different seating sections in large urban theatres, which were typically studio-owned.

History

Due to these theaters' proximity to controversially sexualized forms of entertainment like burlesque, the term "grindhouse" has often been erroneously associated with burlesque theaters in urban entertainment areas such as 42nd Street in New York City,[2][3] where bump and grind dancing and striptease were featured.[4] In the film Lady of Burlesque (1943) one of the characters refers to one such burlesque theatre on 42nd Street as a "grindhouse," but Church points out the primary definition in the Oxford English Dictionary is for a movie theater distinguished by three criteria:[2]

- Shows a variety of films, in continuous succession

- Low admission fees

- Films screened are frequently of poor quality or low (artistic) merit

Church states the first use of the term "grind house" was in a 1923 Variety article,[5] which may have adopted the contemporary slang usage of "grind" to refer to the actions of barkers exhorting potential patrons to enter the venue.[2]

Double, triple, and "all night" bills on a single admission charge often encouraged patrons to spend long periods of time in the theaters.[6] The milieu was largely and faithfully captured at the time by the magazine Sleazoid Express.

Because grindhouse theaters were associated with a lower class audience, grindhouse theaters gradually became perceived as disreputable places that showed disreputable films, regardless of the variety of films – including subsequent-run Hollywood films – that were actually screened.[7] Similar second-run screenings are held at discount theaters and neighborhood theatres; the distinguishing characteristics of the "grindhouse" are its typical urban setting and the programming of first-run films of low merit, not predominantly second-run films which had received wide releases.

Television pressure

The introduction of television greatly eroded the audience for local and single-screen movie theaters, many of which were built during the cinema boom of the 1930s. In combination with urban decay after white flight out of older city areas in the mid to late 1960s, changing economics forced these theaters to either close or offer something that television could not. In the 1970s, many of these theaters became venues for exploitation films,[4] such as adult pornography and sleaze, or slasher horror, and dubbed martial arts films from Hong Kong.[8]

Content

Films shot for and screened at grindhouses characteristically contain large amounts of sex, violence, or bizarre subject matter. One featured genre were "roughies" or sexploitation films, a mix of sex, violence and sadism. Quality varied, but low budget production values and poor print quality were common. Critical opinions varied regarding typical grindhouse fare, but many films acquired cult following and critical praise.

Decline

By the mid 1980s, home video and cable movie channels threatened to render the grindhouse obsolete. By the end of the decade, these theaters had vanished from Los Angeles's Broadway and Hollywood Boulevard, New York City's Times Square and San Francisco's Market Street. Another example was the Jolar Theater in Nashville, Tennessee, on lower Broadway, which was active until it burned down on April 14, 1978.[9]

By the mid-1990s, these particular theaters had all but disappeared from the United States; very few exist today.[when?]

Homage

The Robert Rodriguez film Planet Terror and the Quentin Tarantino film Death Proof, which were released together as Grindhouse in 2007, were created as an homage to the cinematic genre. A movie with a mock-trailer in Grindhouse, Machete (also by Rodriguez), was subsequently made into its own feature-length film, with care to include the scene from the Grindhouse trailer (originally filmed as a trailer of a movie that did not/would never exist). The Canadian release of Grindhouse included one additional faux-trailer, Hobo With a Shotgun, that was also subsequently made into a feature-length film. Similar films such as Chillerama, Drive Angry and Sign Gene have appeared since. S. Craig Zahler's film Brawl in Cell Block 99 is a modern example of the genre, along with his 2018 noir film Dragged Across Concrete.

Manhunt, Red Dead Revolver, The House of the Dead: Overkill, Wet, Shank, RAGE and Shadows of the Damned are several examples of video games that serve as homages to the grindhouse movies.

The author Jacques Boyreau released the book Portable Grindhouse: The Lost Art of the VHS Box in 2009 about the history of the genre.[10] The field is also the focus of the 2010 documentary American Grindhouse. Additionally, authors Bill Landis and Michelle Clifford released Sleazoid Express, both an homage to the various grindhouses within Times Square, but also a history of the various genres that each theater featured.

The Syfy TV show Blood Drive takes inspiration from grindhouse, with each episode featuring a different theme.

The novel Our Lady of the Inferno is both written as an homage to grindhouse films and features several chapters that take place in a grindhouse theater.[11]

The animated series, Seis Manos has a similar premise as grindhouse films of a kung fu story taking place in 1970's Mexico and is shown with a similar grainy film filter and simulated projection miscues.

Ti West's slasher film X (2022) pays homage to grindhouse.[12]

Gallery

Million Dollar Theater in Los Angeles (2012), marquee advertising Mickey One and Blast of Silence

See also

References

I spent my first night in San Diego sleeping in the back row of the Cabrillo Theater.

In that pre-Gaslamp, pre-multiplex downtown of 1978 or so, half a dozen wonderfully eclectic – if mildly disreputable – late night movie houses operated within a few blocks of each other. Each grindhouses was a colorful oasis, plopped down in the middle of a seedy urban sprawl perfectly suited to the sailors on shore leave and porn aficionados that comprised much of its foot traffic.

A couple of bucks got you a double or triple bill, screened 'round the clock in cavernous single-screen movie theaters harkening back to Hollywood's golden age, rich in cinematic history and replete with big wide aisles and accommodating balconies. Horton Plaza had the Carbillo [sic] and the Plaza Theater, both operated by Walnut Properties, whose owner Vince Miranda maintained a suite at the Hotel San Diego (which he also owned).

Because grindhouse theaters were nasty places, full of nasty people, and most of us wouldn't be caught dead in one. The few folks who were there for the actual movies were either poverty tourists or cinephiles who didn't notice anything except the flickering screen, and, in many cases, their cinephilia had burned out their sense of discrimination, because a lot of the movies that showed in grindhouses were bad.

- "X review – back-to-basics slasher pits porn stars against elderly killers". The Guardian. March 16, 2022.

Bibliography

- Church, David (2015). Grindhouse Nostalgia: Memory, home video and exploitation film fandom. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-9910-0. Retrieved March 24, 2017.

- Fisher, Austin; Walker, Johnny, eds. (2016). Grindhouse—Cultural Exchange on 42nd Street, and Beyond. New York City: Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-1-6289-2747-4. Retrieved March 24, 2017.

External links

- Grindhouse Cinema Database

- The Grindhouse Schoolhouse: Exploring Classic Adult Cinema

- A review of Grindhouse: The Forbidden World of "Adults Only" Cinema, by Eddie Muller and Daniel Faris.

- Grindhouse.com

- "The Original Grindhouse Theatres. Located On 42nd Street, New York". Grindhouse Therapy. Retrieved March 24, 2017.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grindhouse

| Years active | 1970s-current |

|---|---|

| Country | China, Japan, United States |

| Major figures | |

| Influences | |

| Influenced |

Bruceploitation (a portmanteau of "Bruce Lee" and "exploitation") is an exploitation film subgenre that emerged after the death of martial arts film star Bruce Lee in 1973, during which time filmmakers from Hong Kong, Taiwan and South Korea cast Bruce Lee look-alike actors ("Lee-alikes") to star in imitation martial arts films, in order to exploit Lee's sudden international popularity.[1] Bruce Lee look-alike characters also commonly appear in other media, including anime, comic books, manga, and video games.

History

When martial arts film star Bruce Lee died on July 20, 1973, he was Hong Kong's most famous martial arts actor. When Enter the Dragon became a box office success worldwide, many Hong Kong studios feared that a movie without their most famous star in it would not be financially successful and decided to play on Lee's sudden international fame by making movies that sounded like Bruce Lee starring vehicles. They cast actors who looked like Lee and changed their screen names to variations of Lee's name, such as Bruce Li and Bruce Le.[2]

Actors

After Bruce Lee's death, many actors assumed Lee-like stage names. Bruce Li (黎小龍 from his real name Ho Chung Tao 何宗道), Bruce Chen, Bruce Lai (real name Chang Yi-Tao), Bruce Le (呂小龍 from his real name Wong Kin Lung, 黃建龍), Bruce Lie, Bruce Leung, Saro Lee, Bruce Ly, Bruce Thai, Brute Lee, Myron Bruce Lee, Lee Bruce, and Bruce Lei / Dragon Lee (real name Moon Kyoung-seok) were hired by studios to play Lee-styled roles.[3] Bruce Li appeared in Bruce Lee Against Supermen, in which he stars as Kato, assistant of the Green Hornet, a role originally played by the real Bruce Lee.[4]

Additionally, when some Japanese karate and Korean taekwondo films were dubbed into English for U.S. release, the protagonists were given new Lee-like stage names. Such was the case with Jun Chong (credited as Bruce K. L. Lea in the altered and English-dubbed Bruce Lee Fights Back from the Grave) and Tadashi Yamashita (credited as Bronson Lee in the altered English-dubbed Bronson Lee, Champion).

Jackie Chan, who started his movie career as an extra and stunt artist in some of Bruce Lee's movies, was also given roles where he was promoted as the next Bruce Lee as Chan Yuen Lung (with Yuen Lung's stage name borrowed from his fellow Fortunes actor Sammo Hung), such as New Fist of Fury (1976). Only when he made some comedy-themed movies for another studio was he able to attain box-office success.[citation needed]

In 2001, actor Danny Chan Kwok-kwan sported Lee's look in the Cantonese comedy film Shaolin Soccer. The role landed him to play Lee in the biographical television series The Legend of Bruce Lee.[citation needed]

Film and television

Some of the films, such as Re-Enter the Dragon, Enter Three Dragons, Return of Bruce, Enter Another Dragon, Return of the Fists of Fury, or Enter the Game of Death, were rehashes of Bruce Lee's classics. Others told Lee's life story and explored his mysteries, such as Bruce Lee's Secret (a farcical rehash starring Bruce-clone Bruce Li in San Francisco defending Chinese immigrants from thugs), Exit the Dragon, Enter the Tiger (where Bruce Li is asked by Bruce Lee to replace him after his death), and Bruce's Fist of Vengeance.

Other films used his death as a plot element such as The Clones of Bruce Lee (where clones of Bruce Lee portrayed by some of the above actors are created by scientists) or The Dragon Lives Again (where Bruce Lee fights fictional characters such as James Bond, Clint Eastwood and Dracula in Hell and finds allies amongst others such as Popeye and Kwai Chang Caine). Others, such as Bruce Lee Fights Back from the Grave, featured Lee imitators but with a plot having nothing to do with Bruce Lee.

One of Lee's fight choreographers, actor-director Sammo Hung, famously satirised the phenomenon of Bruceploitation in his 1978 film, Enter the Fat Dragon. Elliott Hong's They Call Me Bruce? satirised the tendency for all male Asian actors (and by extension, male Asians in general) to have to sell themselves as Bruce Lee-types to succeed.

One notable film is Fist of Fear, Touch of Death released in 1980. While the real Lee does appear in the movie, it is only through dubbed stock footage.[5] The movie passes itself off as non-fiction but is fictional. The plot involves a martial arts tournament where the prize is recognition as Lee's successor. This is intertwined with what the movie passes off as the life story of Bruce Lee. The film says that Lee's parents did not want him be a martial artist, and he ran away from home to become an actor. In real life, they encouraged his careers.[5] The film conflates China and Japan by stating Lee's martial art was Karate (a Japanese art) instead of Kung Fu (a Chinese art) and that his great-grandfather was a samurai (impossible as samurai are found in Japan, not China).[6]

Partial list of films

- The Pig Boss (Philippines, 1972), starring Ramon Zamora

- Shadow of the Dragon (Philippines, 1973), starring Ramon Zamora

- The Game of Death! (Philippines, 1974), starring Ramon Zamora

- Bruce Lee: A Dragon Story (Hong Kong, 1974), starring Bruce Li

- Goodbye Bruce Lee: His Last Game of Death (Taiwan, 1975), starring Bruce Li

- Exit the Dragon, Enter the Tiger (Taiwan/Hong Kong, 1976), starring Bruce Li

- Bruce Lee Fights Back from the Grave (South Korea, 1976), starring Jun Chong

- New Fist of Fury (Hong Kong, 1976), a sequel to Fist of Fury starring Jackie Chan

- The Dragon Lives (Taiwan/Hong Kong, 1976), starring Bruce Li

- Bruce Lee: The Man, The Myth (Hong Kong, 1976), starring Bruce Li

- The Dragon Lives Again (Hong Kong, 1977), starring Bruce Leung

- Fist of Fury II (Hong Kong, 1977), a sequel to Fist of Fury starring Bruce Li; unrelated to New Fist of Fury

- Return of the Tiger (Hong Kong, 1978), starring Bruce Li

- The Image of Bruce Lee (Hong Kong, 1978), starring Bruce Li

- Fists of Bruce Lee (Hong Kong, 1978), starring Bruce Li

- Enter the Game of Death (South Korea/Hong Kong, 1978), starring Bruce Le

- Fist of Fury III (Hong Kong, 1979), starring Bruce Li

- They Call Him Bruce Lee (Philippines, 1979), starring Jack Lee and Rey Malonzo

- Kungfu Fever (South Korea/Taiwan, 1979), starring Dragon Lee

- Fist of Fear, Touch of Death (United States, 1980), starring Bruce Lee (archival footage) and Fred Williamson

- The Clones of Bruce Lee (South Korea/Hong Kong, 1980), starring Bruce Le, Dragon Lee, Bruce Lai, and Bruce Thai

- Bruce's Fist of Vengeance (Philippines, 1980), starring Bruce Le

- Katilon Ke Kaatil (India, 1981), Hindi film featuring Bruce Le in several scenes[7]

- Jackie and Bruce to the Rescue (Hong Kong, 1982), starring Tong Lung

End of a trend

Bruceploitation ended when Jackie Chan made a name for himself with the success of the kung fu comedies Snake in the Eagle's Shadow and Drunken Master. These films established him as the "new king" of Hong Kong martial arts cinema. Another factor in the end of Bruceploitation was the beginning of the Shaw Brothers film era in the late 1970s, which started with movies such as Five Deadly Venoms which featured new martial arts stars in the Venom Mob. Since the end of the trend, Bruce Lee's influence on Hong Kong action cinema remained strong, but the actors began establishing their own personalities, and the films began to take on a more comedic approach.[8][9]

Documentary

In 2017, Michael Worth began an effort to shine more light on the subject, producing what would become Enter the Clones of Bruce (2023), the first official documentary on the subject with Severin Films. The documentary interviews many of the key players of the Bruceploitation movement, including Ho Chung-tao (Bruce Li), Huang Jianlong (Bruce Le), Ryong Keo (Dragon Lee), and Leung Choi-sang (Bruce Liang). The film will have its world premiere at the 2023 Tribeca Film Festival.[10]

Rebirth

This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (July 2015) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

The neutrality of this article is disputed. Relevant discussion may be found on the talk page. Please do not remove this message until conditions to do so are met. (June 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

Bruceploitation has continued in the United States in a muted form since the 1970s. Films such as Force: Five, No Retreat, No Surrender, and The Last Dragon used Bruce Lee as a marketing hook, and the genre continues to be a source of exploration for fans of the late Little Dragon and his doppelgangers. Fist of Fear, Touch of Death told a fictional life story of the star.

In May 2010, Carl Jones published the book Here Come the Kung Fu Clones. It focuses on a particular Lee-a-like, Ho Chung Tao, but it also explores the best and worst actors and films that the genre has to offer.[11]

In the third season of the 2012 Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles animated series, the character of Hun (originally a muscle-bound Caucasian from the 2003 cartoon series) makes his debut, with his appearance and behaviour closely patterned after Bruce Lee.[12]

The first Spanish book on the genre by Ivan E. Fernandez Fojón, Bruceploitation. Los clones de Bruce Lee was published by Applehead Team Creaciones in November 2017.

Stewart Home’s book Re-Enter The Dragon: Genre Theory, Brucesploitation & the Sleazy Joys of Lowbrow Cinema (Ledatape Organisation, Melbourne 2018) "is cleaning up the territory and sharpening the contours of the category of Bruceploitation which as he sees it has not been worked out rigorously enough by early pioneers."[13] This book appeared after Home made and exhibited an art film meditation on the subject of Bruceploitation for Glasgow International in 2016.[14]

The Legend of Bruce Lee (2008), a Chinese television drama series based on the life of Bruce Lee, has been watched by over 400 million viewers in China through CCTV, making it the most-watched Chinese television drama series of all time, as of 2017.[15][16] It has also been aired in other parts of the world: United States (KTSF), Italy (RAI 4), Canada (FTV), Brazil (Rede CNT; Band), Vietnam (HTV2; DN1-RTV), South Korea (SBS), Japan (NTV), Hong Kong (ATV Home), Philippines (Q), Taiwan (TTV), Iran (IRIB), Venezuela (Televen), United Kingdom (Netflix) and Indonesia (Hi Indo).

Comics and animation

This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (July 2015) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

The comic book medium also gave birth to several characters inspired by Bruce Lee, most notably in Japanese comics or manga.

Bruce Lee had an influence on several American comic book writers, notably Marvel Comics founder Stan Lee,[17] who considered Bruce Lee to be a superhero without a costume.[18] Shortly after his death, Lee inspired the Marvel character Iron Fist (debuted 1974) and the comic book series The Deadly Hands of Kung Fu (debuted 1974). According to Stan Lee, any character that is a martial artist since then owes their origin to Bruce Lee in some form.[18] Paul Gulacy was inspired by Bruce Lee when he drew the Marvel character Shang-Chi.[19]

Manga and anime

In Tetsuo Hara and Buronson’s influential shōnen manga and anime series Hokuto no Ken, known to Western audiences as Fist of the North Star, the main character Kenshiro was deliberately created by them based on Bruce Lee, combined with influences from the film Mad Max.[20] Kenshiro’s appearance resembles that of Lee, as well as mannerisms inspired by Lee, such as his fighting style and battle cries. Additionally, in Hokuto no Ken’s prequel Souten no Ken, the main character is Kenshiro’s uncle, named Kenshiro Kasumi, who is also modelled after Lee’s physique and mannerisms in the same way as his nephew.

Akira Toriyama's influential shonen manga and anime series Dragon Ball was also inspired by Bruce Lee films, such as Enter the Dragon (1973).[21][22] The title Dragon Ball was inspired by Enter the Dragon as well as later Bruceploitation knockoff kung fu movies which frequently had the word "Dragon" in the title.[21] Later, when Toriyama created the Super Saiyan transformation during the Freeza arc, he gave Goku piercing eyes based on Bruce Lee's paralysing glare.[23]

In Masashi Kishimoto’s Naruto manga, the characters Might Guy and Rock Lee were modelled by him after Bruce Lee.

Video games

Bruce Lee films such as Game of Death and Enter the Dragon were the foundation for video game genres such as beat 'em up action games and fighting games.[24][25][26] Kung-Fu Master (1984), considered the first beat 'em up game, is based on Lee's Game of Death, with the five-level Devil's Temple reflecting the movie's setting of a five-level pagoda with a martial arts master in each level.[27] Kung-Fu Master in turn served as the prototype for most subsequent martial arts action games in the late 1980s.[28] Datasoft Inc. also released the game Bruce Lee in 1984.

The fighting game Yie Ar Kung-Fu (1985) was also inspired by Bruce Lee films, with the main player character Oolong modelled after Lee (like Bruceploitation films). In turn, Yie Ar Kung-Fu established the template for subsequent fighting games.[29] The Street Fighter video game franchise (1987 debut) was inspired by Enter the Dragon, with the gameplay centered around an international fighting tournament, and each character having a unique combination of ethnicity, nationality and fighting style; Street Fighter went on to set the template for all fighting games that followed.[30]

Since then, numerous fighting games have featured Bruce Lee look-alike characters, starting with World Heroes which introduced Kim Dragon in 1992.[24] Super Street Fighter II character Fei Long was designed as a homage to Bruce Lee as well. The character Liu Kang in the Mortal Kombat franchise was also modelled after Bruce Lee.[31] The Tekken franchise followed suit with Marshall Law, and just once had him substituted by introducing his son Forest Law. EA Sports UFC includes Bruce Lee as an unlockable character, though it came with the approval of his daughter Shannon.

Another notable game that features Bruce Lee is The Dragon, released in 1995 by Ramar International (also called Rinco) and Tony Tech in Taiwan.[32] The game is for the Famicom (better known as the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) in the west) but is not licensed by Nintendo or the Bruce Lee estate. The game's plot is loosely based on the plots of Lee's films and most levels are given titles from them.[32] The game mixes fighting parts with platforming parts and is also noted for stealing graphics from Mortal Kombat (including using Liu Kang to represent Lee), being one of the few Famicom/NES games to have two languages (English and Arabic) available in game and one of the few in Arabic at all.[32] The game's official Arabic title as shown on the title screen is التنين ("Al-Tinneen") and the box also gives the game the Chinese title of 李小龍 ("Lǐ Xiǎolóng", Bruce Lee's name in Chinese) and the alternate title of Lee Dragon.[32]

Many other video games have characters based on Lee, although he is rarely credited. Video game characters synonymous with Lee are usually spotted by fighting techniques and signature "jumping stance", physical appearances, clothing, and iconic battle cries and yells similar to those of Lee. Examples include fighting game characters such as Maxi in the Soulcalibur series and Jann Lee in the Dead or Alive series.

Commercials

Though Bruce Lee did not appear in commercials during his lifetime, his likeness and image has since appeared in hundreds of commercials around the world.[18]

Nokia launched an Internet-based campaign in 2008 with staged "documentary-looking" footage of Bruce Lee playing ping-pong with his nunchaku and also igniting matches as they are thrown toward him. The videos went viral on YouTube, creating confusion as some people believed them to be authentic footage.[33]

Merchandise

The clothing apparel company Bow & Arrow released the "Gung Fu Scratch" t-shirt, featuring an image of Bruce Lee photoshopped to make it look like he is DJing. The t-shirt has been worn by celebrities such as Justin Bieber, Will Smith, Nas, Snoop Dogg and Ne-Yo.[34] The image became more popular following its appearance in the Marvel Cinematic Universe superhero film Avengers: Age of Ultron (2015), in which Tony Stark (Robert Downey Jr.) wears it. Sales of the t-shirt increased substantially following the film's release.[35]

See also

- Media about Bruce Lee

- Bruce Lee (comics)

- Bruce Lee filmography

- Bruce Lee Library

- List of awards and honors received by Bruce Lee

- Jeet Kune Do

References

- Guerrasio, Jason. "Sales for this Bruce Lee DJing shirt in 'Avengers: Age of Ultron' are through the roof". Business Insider. Retrieved May 16, 2022.

External links

- Bruceploitation by Keith Dixon

- Brucesploitation @ The Deuce: Grindhouse Cinema Database

- Clones of Bruce Lee

- Here Come the Kung Fu Clones by Carl Jones

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bruceploitation

Cannibal films, alternatively known as the cannibal genre or the cannibal boom, are a subgenre of horror films made predominantly by Italian filmmakers during the 1970s and 1980s. This subgenre is a collection of graphically violent movies that usually depict cannibalism by primitive, Stone Age natives deep within the Asian or South American rainforests. While cannibalism is the uniting feature of these films, the general emphasis focuses on various forms of shocking, realistic and graphic violence, typically including torture, rape and genuine cruelty to animals. This subject matter was often used as the main advertising draw of cannibal films in combination with exaggerated or sensational claims regarding the films' reputations.

The genre evolved in the early 1970s from a similar subgenre known as mondo films, exploitation documentaries which claimed to present genuine taboo behaviors from around the world. Umberto Lenzi is often cited as originating the cannibal genre with his 1972 film Man from Deep River, while Antonio Climati's Natura contro from 1988 is similarly regarded to have brought the trend to a close.[1] Ruggero Deodato's Cannibal Holocaust, released in 1980,[2] is often considered to be the best-known film of the genre due to the significant controversy surrounding its release, and is one of the few films of the genre to garner mainstream attention. In recent years, the genre has experienced a cult following and revival, as new productions influenced by the original wave of films have been released.

Due to their graphic content, the films of this subgenre are often the center of controversy, and many have been censored or banned in countries around the world. The animal cruelty featured in many of the films is often the focal point of the controversy, and these scenes have been targeted by certain countries' film boards. Several cannibal films also appeared on the video nasty list released by the Director of Public Prosecutions in 1983 in the United Kingdom. Nonetheless, the genre has occasionally fallen under favorable or more positive critical interpretation, and certain cannibal films have been noted for containing themes of anti-imperialism and critiques or commentary on Third World oppression and exploitation.

Characteristics

This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (September 2022) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

The plots of cannibal films usually involved Western characters entering the Amazon or South East Asian rainforests on an expedition, only to encounter hostile natives on the way to their destination. Other films that are sometimes associated with the genre, such as Cannibal Apocalypse and We're Going to Eat You, do not follow this plotline. The films are known for their lurid content, such as sex, nudity and various forms of graphic violence. Sexual assault, torture, and the on-screen depiction of cannibalism are also common, and these acts are performed by both the Westerners and the natives.

The films' advertising focused on the presentation of this content rather than any critical acclaim. This form of advertising was sometimes accompanied by claims regarding the film's notoriety. For instance, the posters for Cannibal Ferox claimed that the film was banned in 31 countries, while the British home video cover for Eaten Alive! similarly noted that the film was previously banned in the country.

History

This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (September 2022) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

Films containing elements similar to cannibal films existed before the genre's inception. Rainforest adventure films were often found popular in cinema (such as with the Tarzan movies of the 1930s and 1940s starring Johnny Weissmuller). Some of these films even included primitive, and in some cases, alleged cannibal tribes, and could be seen as the prototype for the modern cannibal film. One movie that can almost be definitively linked as the predecessor to the cannibal genre is Cornel Wilde's 1965 film The Naked Prey, which involved a white man being chased by a tribe of natives because his safari group offended their chief.

Another influential film on this genre was the 1970 Richard Harris western A Man Called Horse which, although it involved non-cannibalistic Native Americans, was about a civilized white man being captured by, and forced to live with, a tribe of savages, during which time he comes to respect, and strives to join, his captors. The basic plot of Man from Deep River is an almost scene-for-scene swipe from that film, merely substituting rainforest cannibals for the Native Americans. This film, created to imitate the famous 1970 Richard Harris western, would wind up becoming the template for what would later become the Italian cannibal film genre.

The subgenre as it is known today is usually regarded to have started with Italian director Umberto Lenzi's 1972 film Man from Deep River. It was released in New York City as Sacrifice!, and was a 42nd Street hit.[3] This film inspired several other similar films to be made during the late 1970s, a period identified by genre fans as the "cannibal boom".[4] Included in these films are Ruggero Deodato's 1977 film Ultimo mondo cannibale (a.k.a. Last Cannibal World, a.k.a. Jungle Holocaust), Sergio Martino's 1978 film The Mountain of the Cannibal God and a few films by Joe D'Amato starring Laura Gemser. However, Deodato also claims to be the forefather of the subgenre, with his film Ultimo mondo cannibale. Lenzi said in an interview for Calum Waddell's documentary Eaten Alive! The Rise and Fall of the Italian Cannibal Film:

Well, Mr. Ruggero Deodato, my "dear friend", says that he invented this genre. He says that I copied him because he had done Last Cannibal World and then Cannibal Holocaust. However, it is actually down to me that he did those films. It was down to me because after I filmed Man from Deep River, which was called Mondo Cannibale in Germany and did very well, the producer then signed another contract with the German distributors. It gave them an 80% guarantee based on another cannibal film directed by Umberto Lenzi and starring Me Me Lai and Ivan Rassimov. The producer signed this contract and he was at my house for dinner expecting me to do another film like the one we had just done and telling me how he had sold it to the Germans. I said okay, fine, but as the film did so well, I want to be paid exactly double of what I was given before. He refused, saying it was too much and so on. I said okay, good luck to you. Plus I was already signed up with Dania Film to do Almost Human. So what the producer did, so as not to void the contract with the Germans, was to change directors, stating I was ill or something. But he kept Me Me Lai and Ivan Rassimov. But Rassimov had a smaller part now. Nevertheless, both of them remained as part of this contract. So it was down to me that he [Deodato] got to do Last Cannibal World. It was me that said no. So he did it instead. However, if I had accepted it, like the contract stated, maybe he would never have done a cannibal film.[5]

In response, Deodato, being interviewed for the same film, stated: