Category:Lost films

| This is a container category. Due to its scope, it should contain only subcategories. |

Subcategories

This category has the following 21 subcategories, out of 21 total.

- Rediscovered films (2 C, 6 P)

A

- Lost animated films (17 P)

C

- Lost crime films (2 C, 18 P)

D

- Lost drama films (10 C, 1,356 P)

F

- Lost fantasy films (2 C, 10 P)

H

- Lost horror films (1 C, 23 P)

L

- Lists of lost films (10 P)

M

- Lost mystery films (1 C, 33 P)

R

- Lost romance films (2 C, 18 P)

S

- Lost sports films (2 C, 5 P)

W

- Lost Western (genre) films (1 C, 248 P)

Pages in category "Lost films"

The following 3 pages are in this category, out of 3 total. This list may not reflect recent changes.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Lost_films

In Greek and Roman mythology, the Giants, also called Gigantes (Greek: Γίγαντες, Gígantes, singular: Γίγας, Gígas), were a race of great strength and aggression, though not necessarily of great size. They were known for the Gigantomachy (or Gigantomachia), their battle with the Olympian gods.[2] According to Hesiod, the Giants were the offspring of Gaia (Earth), born from the blood that fell when Uranus (Sky) was castrated by his Titan son Cronus.[3]

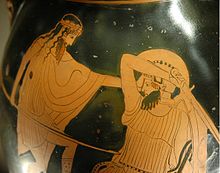

Archaic and Classical representations show Gigantes as man-sized hoplites (heavily armed ancient Greek foot soldiers) fully human in form.[4] Later representations (after c. 380 BC) show Gigantes with snakes for legs.[5] In later traditions, the Giants were often confused with other opponents of the Olympians, particularly the Titans, an earlier generation of large and powerful children of Gaia and Uranus.

The vanquished Giants were said to be buried under volcanoes and to be the cause of volcanic eruptions and earthquakes.

Origins

The name "Gigantes" is usually taken to imply "earth-born",[6] and Hesiod's Theogony makes this explicit by having the Giants be the offspring of Gaia (Earth). According to Hesiod, Gaia, mating with Uranus, bore many children: the first generation of Titans, the Cyclopes, and the Hundred-Handers.[7] However, Uranus hated his children and, as soon as they were born, he imprisoned them inside of Gaia, causing her much distress. Therefore, Gaia made a sickle of adamant which she gave to Cronus, the youngest of her Titan sons, and hid him (presumably still inside Gaia's body) to wait in ambush.[8] When Uranus came to lie with Gaia, Cronus castrated his father, and "the bloody drops that gushed forth [Gaia] received, and as the seasons moved round she bore ... the great Giants."[9] From these same drops of blood also came the Erinyes (Furies) and the Meliai (ash tree nymphs), while the severed genitals of Uranus falling into the sea resulted in a white foam from which Aphrodite grew. The mythographer Apollodorus also has the Giants being the offspring of Gaia and Uranus, though he makes no connection with Uranus' castration, saying simply that Gaia "vexed on account of the Titans, brought forth the Giants".[10]

There are three brief references to the Gigantes in Homer's Odyssey, though it's not entirely clear that Homer and Hesiod understood the term to mean the same thing.[11] Homer has Giants among the ancestors of the Phaiakians, a race of men encountered by Odysseus, their ruler Alcinous being the son of Nausithous, who was the son of Poseidon and Periboea, the daughter of the Giant king Eurymedon.[12] Elsewhere in the Odyssey, Alcinous says that the Phaiakians, like the Cyclopes and the Giants, are "near kin" to the gods.[13] Odysseus describes the Laestrygonians (another race encountered by Odysseus in his travels) as more like Giants than men.[14] Pausanias, the 2nd century AD geographer, read these lines of the Odyssey to mean that, for Homer, the Giants were a race of mortal men.[15]

The 6th–5th century BC lyric poet Bacchylides calls the Giants "sons of the Earth".[16] Later the term "gegeneis" ("earthborn") became a common epithet of the Giants.[17] The first century Latin writer Hyginus has the Giants being the offspring of Gaia and Tartarus, another primordial Greek deity.[18]

Confusion with Titans and others

Though distinct in early traditions,[19] Hellenistic and later writers often confused or conflated the Giants and their Gigantomachy with an earlier set of offspring of Gaia and Uranus, the Titans and their war with the Olympian gods, the Titanomachy.[20] This confusion extended to other opponents of the Olympians, including the huge monster Typhon,[21] the offspring of Gaia and Tartarus, whom Zeus finally defeated with his thunderbolt, and the Aloadae, the large, strong and aggressive brothers Otus and Ephialtes, who piled Pelion on top of Ossa in order to scale the heavens and attack the Olympians (though in the case of Ephialtes there was probably a Giant with the same name).[22] For example, Hyginus includes the names of three Titans, Coeus, Iapetus, and Astraeus, along with Typhon and the Aloadae, in his list of Giants,[23] and Ovid seems to conflate the Gigantomachy with the later siege of Olympus by the Aloadae.[24]

Ovid also seems to confuse the Hundred-Handers with the Giants, whom he gives a "hundred arms".[25] So perhaps do Callimachus and Philostratus, since they both make Aegaeon the cause of earthquakes, as was often said about the Giants (see below).[26]

Descriptions

Homer describes the Giant king Eurymedon as "great-hearted" (μεγαλήτορος), and his people as "insolent" (ὑπερθύμοισι) and "froward" (ἀτάσθαλος).[27] Hesiod calls the Giants "strong" (κρατερῶν) and "great" (μεγάλους) which may or may not be a reference to their size.[28] Though a possible later addition, the Theogony also has the Giants born "with gleaming armour, holding long spears in their hands".[29]

Other early sources characterize the Giants by their excesses. Pindar describes the excessive violence of the Giant Porphyrion as having provoked "beyond all measure".[30] Bacchylides calls the Giants arrogant, saying that they were destroyed by "Hybris" (the Greek word hubris personified).[31] The earlier seventh century BC poet Alcman perhaps had already used the Giants as an example of hubris, with the phrases "vengeance of the gods" and "they suffered unforgettable punishments for the evil they did" being possible references to the Gigantomachy.[32]

Homer's comparison of the Giants to the Laestrygonians is suggestive of similarities between the two races. The Laestrygonians, who "hurled ... rocks huge as a man could lift", certainly possessed great strength, and possibly great size, as their king's wife is described as being as big as a mountain.[33]

Over time, descriptions of the Giants make them less human, more monstrous and more "gigantic". According to Apollodorus the Giants had great size and strength, a frightening appearance, with long hair and beards and scaly feet.[34] Ovid makes them "serpent-footed" with a "hundred arms",[35] and Nonnus has them "serpent-haired".[36]

The Gigantomachy

The most important divine struggle in Greek mythology was the Gigantomachy, the battle fought between the Giants and the Olympian gods for supremacy of the cosmos.[37] It is primarily for this battle that the Giants are known, and its importance to Greek culture is attested by the frequent depiction of the Gigantomachy in Greek art.

Early sources

The references to the Gigantomachy in archaic sources are sparse.[39] Neither Homer nor Hesiod mention anything about the Giants battling the gods.[40] Homer's remark that Eurymedon "brought destruction on his froward people" might possibly be a reference to the Gigantomachy[41] and Hesiod's remark that Heracles performed a "great work among the immortals"[42] is probably a reference to Heracles' crucial role in the gods' victory over the Giants.[43] The Hesiodic Catalogue of Women (or the Ehoia) following mentions of his sacks of Troy and of Kos, refers to Heracles having slain "presumptious Giants".[44] Another probable reference to the Gigantomachy in the Catalogue has Zeus produce Heracles to be "a protector against ruin for gods and men".[45]

There are indications that there might have been a lost epic poem, a Gigantomachia, which gave an account of the war: Hesiod's Theogony says that the Muses sing of the Giants,[46] and the sixth century BC poet Xenophanes mentions the Gigantomachy as a subject to be avoided at table.[47] The Apollonius scholia refers to a "Gigantomachia" in which the Titan Cronus (as a horse) sires the centaur Chiron by mating with Philyra (the daughter of two Titans), but the scholiast may be confusing the Titans and Giants.[48] Other possible archaic sources include the lyric poets Alcman (mentioned above) and the sixth-century Ibycus.[49]

The late sixth early fifth century BC lyric poet Pindar provides some of the earliest details of the battle between the Giants and the Olympians. He locates it "on the plain of Phlegra" and has Teiresias foretell Heracles killing Giants "beneath [his] rushing arrows".[50] He calls Heracles "you who subdued the Giants",[51] and has Porphyrion, who he calls "the king of the Giants", being overcome by the bow of Apollo.[52] Euripides' Heracles has its hero shooting Giants with arrows,[53] and his Ion has the chorus describe seeing a depiction of the Gigantomachy on the late sixth century Temple of Apollo at Delphi, with Athena fighting the Giant Enceladus with her "gorgon shield", Zeus burning the Giant Mimas with his "mighty thunderbolt, blazing at both ends", and Dionysus killing an unnamed Giant with his "ivy staff".[54] The early 3rd century BC author Apollonius of Rhodes briefly describes an incident where the sun god Helios takes up Hephaestus, exhausted from the fight in Phlegra, on his chariot.[55]

Apollodorus

The most detailed account of the Gigantomachy[57] is that of the (first or second-century AD) mythographer Apollodorus.[58] None of the early sources give any reasons for the war. Scholia to the Iliad mention the rape of Hera by the Giant Eurymedon,[59] while according to the scholia to Pindar's Isthmian 6, it was the theft of the cattle of Helios by the Giant Alcyoneus that started the war.[60] Apollodorus, who also mentions the theft of Helios' cattle by Alcyoneus,[61] suggests a mother's revenge as the motive for the war, saying that Gaia bore the Giants because of her anger over the Titans (who had been vanquished and imprisoned by the Olympians).[62] Seemingly, as soon as the Giants are born they begin hurling "rocks and burning oaks at the sky".[63]

There was a prophecy that the Giants could not be killed by the gods alone, but they could be killed with the help of a mortal.[64] Hearing this, Gaia sought for a certain plant (pharmakon) that would protect the Giants. Before Gaia or anyone else could find this plant, Zeus forbade Eos (Dawn), Selene (Moon) and Helios (Sun) to shine, harvested all of the plant himself and then he had Athena summon Heracles.

According to Apollodorus, Alcyoneus and Porphyrion were the two strongest Giants. Heracles shot Alcyoneus, who fell to the ground but then revived, for Alcyoneus was immortal within his native land. So Heracles, with Athena's advice, dragged him beyond the borders of that land, where Alcyoneus then died (compare with Antaeus).[65] Porphyrion attacked Heracles and Hera, but Zeus caused Porphyrion to become enamoured of Hera, whom Porphyrion then tried to rape, but Zeus struck Porphyrion with his thunderbolt and Heracles killed him with an arrow.[66]

Other Giants and their fates are mentioned by Apollodorus. Ephialtes was blinded by an arrow from Apollo in his left eye, and another arrow from Heracles in his right. Eurytus was killed by Dionysus with his thyrsus, Clytius by Hecate with her torches and Mimas by Hephaestus with "missiles of red-hot metal" from his forge.[67] Athena crushed Enceladus under the Island of Sicily and flayed Pallas, using his skin as a shield. Poseidon broke off a piece of the island of Kos called Nisyros, and threw it on top of Polybotes (Strabo also relates the story of Polybotes buried under Nisyros but adds that some say Polybotes lies under Kos instead).[68] Hermes, wearing Hades' helmet, killed Hippolytus, Artemis killed Gration, and the Moirai (Fates) killed Agrius and Thoas with bronze clubs. The rest of the giants were "destroyed" by thunderbolts thrown by Zeus, with each Giant being shot with arrows by Heracles (as the prophecy seemingly required).

Ovid

The Latin poet Ovid gives a brief account of the Gigantomachy in his poem Metamorphoses.[69] Ovid, apparently including the Aloadae's attack upon Olympus as part of the Gigantomachy, has the Giants attempt to seize "the throne of Heaven" by piling "mountain on mountain to the lofty stars" but Jove (i.e. Jupiter, the Roman Zeus) overwhelms the Giants with his thunderbolts, overturning "from Ossa huge, enormous Pelion".[70] Ovid tells that (as "fame reports") from the blood of the Giants came a new race of beings in human form.[71] According to Ovid, Earth [Gaia] did not want the Giants to perish without a trace, so "reeking with the copious blood of her gigantic sons", she gave life to the "steaming gore" of the blood soaked battleground. These new offspring, like their fathers the Giants, also hated the gods and possessed a bloodthirsty desire for "savage slaughter".

Later in the Metamorphoses, Ovid refers to the Gigantomachy as: "The time when serpent footed giants strove / to fix their hundred arms on captive Heaven".[72] Here Ovid apparently conflates the Giants with the Hundred-Handers,[73] who, though in Hesiod fought alongside Zeus and the Olympians, in some traditions fought against them.[74]

Other late sources

Eratosthenes records that Dionysus, Hephaestus and several satyrs mounted on donkeys and charged against the Giants. As they drew closer and before the Giants had spotted them, the donkeys brayed, scaring off some Giants who ran away in terror of the unseen enemies, for they had never heard a donkey's bray before.[75] Dionysus placed the donkeys in the skies in gratitude, and in vase paintings from the classical period, satyrs and Maenads can sometimes be seen confronting their gigantic opponents.[76]

A late Latin grammarian of the fifth century AD, Servius, mentions that during the battle, the eagle of Zeus (who once had been the boy Aëtos before his metamorphosis) assisted his master by placing the lightning bolts on his hands.[77]

Location

Various places have been associated with the Giants and the Gigantomachy. As noted above Pindar has the battle occur at Phlegra ("the place of burning"),[78] as do other early sources.[79] Phlegra was said to be an ancient name for Pallene (modern Kassandra)[80] and Phlegra/Pallene was the usual birthplace of the Giants and site of the battle.[81] Apollodorus, who placed the battle at Pallene, says the Giants were born "as some say, in Phlegrae, but according to others in Pallene". The name Phlegra and the Gigantomachy were also often associated, by later writers, with a volcanic plain in Italy, west of Naples and east of Cumae, called the Phlegraean Fields.[82] The third century BC poet Lycophron, apparently locates a battle of gods and Giants in the vicinity of the volcanic island of Ischia, the largest of the Phlegraean Islands off the coast of Naples, where he says the Giants (along with Typhon) were "crushed" under the island.[83] At least one tradition placed Phlegra in Thessaly.[84]

According to the geographer Pausanias, the Arcadians claimed that battle took place "not at Pellene in Thrace" but in the plain of Megalopolis where "rises up fire".[85] Another tradition apparently placed the battle at Tartessus in Spain.[86] Diodorus Siculus presents a war with multiple battles, with one at Pallene, one on the Phlegraean Fields, and one on Crete.[87] Strabo mentions an account of Heracles battling Giants at Phanagoria, a Greek colony on the shores of the Black Sea.[88] Even when, as in Apollodorus, the battle starts at one place. Individual battles between a Giant and a god might range farther afield, with Enceladus buried beneath Sicily, and Polybotes under the island of Nisyros (or Kos). Other locales associated with Giants include Attica, Corinth, Cyzicus, Lipara, Lycia, Lydia, Miletus, and Rhodes.[89]

The presence of volcanic phenomena, and the frequent unearthing of the fossilized bones of large prehistoric animals throughout these locations may explain why such sites became associated with the Giants.[90]

In art

Sixth century BC

From the sixth century BC onwards, the Gigantomachy was a popular and important theme in Greek art, with over six hundred representations cataloged in the Lexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae (LIMC).[92]

The Gigantomachy was depicted on the new peplos (robe) presented to Athena on the Acropolis of Athens as part of the Panathenaic festival celebrating her victory over the Giants, a practice dating from perhaps as early as the second millennium BC.[93] The earliest extant indisputable representations of Gigantes are found on votive pinakes from Corinth and Eleusis, and Attic black-figure pots, dating from the second quarter of the sixth century BC (this excludes early depictions of Zeus battling single snake-footed creatures, which probably represent his battle with Typhon, as well as Zeus' opponent on the west pediment of the Temple of Artemis on Kerkyra (modern Corfu) which is probably not a Giant).[94]

Though all these early Attic vases[95] are fragmentary, the many common features in their depictions of the Gigantomachy suggest that a common model or template was used as a prototype, possibly Athena's peplos.[96] These vases depict large battles, including most of the Olympians, and contain a central group which appears to consist of Zeus, Heracles, Athena, and sometimes Gaia.[97] Zeus, Heracles and Athena are attacking Giants to the right.[98] Zeus mounts a chariot brandishing his thunderbolt in his right hand, Heracles, in the chariot, bends forward with drawn bow and left foot on the chariot pole, Athena, beside the chariot, strides forward toward one or two Giants, and the four chariot horses trample a fallen Giant. When present, Gaia is shielded behind Herakles, apparently pleading with Zeus to spare her children.

On either side of the central group are the rest of the gods engaged in combat with particular Giants. While the gods can be identified by characteristic features, for example Hermes with his hat (petasos) and Dionysus his ivy crown, the Giants are not individually characterized and can only be identified by inscriptions which sometimes name the Giant.[99] The fragments of one vase from this same period (Getty 81.AE.211)[100] name five Giants: Pankrates against Heracles,[101] Polybotes against Zeus,[102] Oranion against Dionysus,[103] Euboios and Euphorbos fallen[104] and Ephialtes.[105] Also named, on two other of these early vases, are Aristaeus battling Hephaestus (Akropolis 607), Eurymedon and (again) Ephialtes (Akropolis 2134). An amphora from Caere from later in the sixth century, gives the names of more Giants: Hyperbios and Agasthenes (along with Ephialtes) fighting Zeus, Harpolykos against Hera, Enceladus against Athena and (again) Polybotes, who in this case battles Poseidon with his trident holding the island of Nisyros on his shoulder (Louvre E732).[106] This motif of Poseidon holding the island of Nisyros, ready to hurl it at his opponent, is another frequent feature of these early Gigantomachies.[107]

The Gigantomachy was also a popular theme in late sixth century sculpture. The most comprehensive treatment is found on the north frieze of the Siphnian Treasury at Delphi (c. 525 BC), with more than thirty figures, named by inscription.[108] From left to right, these include Hephaestus (with bellows), two females fighting two Giants; Dionysus striding toward an advancing Giant; Themis[109] in a chariot drawn by a team of lions which are attacking a fleeing Giant; the archers Apollo and Artemis; another fleeing Giant (Tharos or possibly Kantharos);[110] the Giant Ephialtes lying on the ground;[111] and a group of three Giants, which include Hyperphas[112] and Alektos,[113] opposing Apollo and Artemis. Next comes a missing central section presumably containing Zeus, and possibly Heracles, with chariot (only parts of a team of horses remain). To the right of this comes a female stabbing her spear[114] at a fallen Giant (probably Porphyrion);[115] Athena fighting Eriktypos[116] and a second Giant; a male stepping over the fallen Astarias[117] to attack Biatas[118] and another Giant; and Hermes against two Giants. Then follows a gap which probably contained Poseidon and finally, on the far right, a male fighting two Giants, one fallen, the other the Giant Mimon (possibly the same as the Giant Mimas mentioned by Apollodorus).[119]

The Gigantomachy also appeared on several other late sixth century buildings, including the west pediment of the Alkmeonid Temple of Apollo at Delphi, the pediment of the Megarian Treasury at Olympia, the east pediment of the Old Temple of Athena on the Acropolis of Athens, and the metopes of Temple F at Selinous.[120]

Fifth century BC

The theme continued to be popular in the fifth century BC. A particularly fine example is found on a red-figure cup (c. 490–485 BC) by the Brygos Painter (Berlin F2293). On one side of the cup is the same central group of gods (minus Gaia) as described above: Zeus wielding his thunderbolt, stepping into a quadriga, Heracles with lion skin (behind the chariot rather than on it) drawing his (unseen) bow and, ahead, Athena thrusting her spear into a fallen Giant. On the other side are Hephaestus flinging flaming missiles of red-hot metal from two pairs of tongs, Poseidon, with Nisyros on his shoulder, stabbing a fallen Giant with his trident and Hermes with his petasos hanging in back of his head, attacking another fallen Giant. None of the Giants are named.[121]

Phidias used the theme for the metopes of the east façade of the Parthenon (c. 445 BC) and for the interior of the shield of Athena Parthenos.[122] Phidias' work perhaps marks the beginning of a change in the way the Giants are presented. While previously the Giants had been portrayed as typical hoplite warriors armed with the usual helmets, shields, spears and swords, in the fifth century the Giants begin to be depicted as less handsome in appearance, primitive and wild, clothed in animal skins or naked, often without armor and using boulders as weapons.[123] A series of red-figure pots from c. 400 BC, which may have used Phidas' shield of Athena Parthenos as their model, show the Olympians fighting from above and the Giants fighting with large stones from below.[124]

Fourth century BC and later

With the beginning of the fourth century BC probably comes the first portrayal of the Giants in Greek art as anything other than fully human in form, with legs that become coiled serpents having snake heads at the ends in place of feet.[125] Such depictions were perhaps borrowed from Typhon, the monstrous son of Gaia and Tartarus, described by Hesiod as having a hundred snake heads growing from his shoulders.[126] This snake-legged motif becomes the standard for the rest of antiquity, culminating in the monumental Gigantomachy frieze of the second century BC Pergamon Altar. Measuring nearly 400 feet long and over seven feet high, here the Gigantomachy receives its most extensive treatment, with over one hundred figures.[127]

Although fragmentary, much of the Gigantomachy frieze has been restored. The general sequence of the figures and the identifications of most of the approximately sixty gods and goddesses have been more or less established.[128] The names and positions of most Giants remain uncertain. Some of the names of the Giants have been determined by inscription,[129] while their positions are often conjectured on the basis of which gods fought which Giants in Apollodorus' account.[130]

The same central group of Zeus, Athena, Heracles and Gaia, found on many early Attic vases, also featured prominently on the Pergamon Altar. On the right side of the East frieze, the first encountered by a visitor, a winged Giant, usually identified as Alcyoneus, fights Athena.[131] Below and to the right of Athena, Gaia rises from the ground, touching Athena's robe in supplication. Flying above Gaia, a winged Nike crowns the victorious Athena. To the left of this grouping a snake-legged Porphyrion battles Zeus[132] and to the left of Zeus is Heracles.[133]

On the far left side of the East frieze, a triple Hecate with torch battles a snake-legged Giant usually identified (following Apollodorus) as Clytius.[134] To the right lays the fallen Udaeus, shot in his left eye by an arrow from Apollo,[135] along with Demeter who wields a pair of torches against Erysichthon.[136]

The Giants are depicted in a variety of ways. Some Giants are fully human in form, while others are a combination of human and animal forms. Some are snake-legged, some have wings, one has bird claws, one is lion-headed, and another is bull-headed. Some Giants wear helmets, carry shields and fight with swords. Others are naked or clothed in animal skins and fight with clubs or rocks.[137]

The large size of the frieze probably necessitated the addition of many more Giants than had been previously known. Some, like Typhon and Tityus, who were not strictly speaking Giants, were perhaps included. Others were probably invented.[138] The partial inscription "Mim" may mean that the Giant Mimas was also depicted. Other less-familiar or otherwise unknown Giant names include Allektos, Chthonophylos, Eurybias, Molodros, Obrimos, Ochthaios and Olyktor.[139]

In post-classical art

The subject was revived in the Renaissance, most famously in the frescos of the Sala dei Giganti in the Palazzo del Te, Mantua. These were painted around 1530 by Giulio Romano and his workshop, and aimed to give the viewer the unsettling idea that the large hall was in the process of collapsing. The subject was also popular in Northern Mannerism around 1600, especially among the Haarlem Mannerists, and continued to be painted into the 18th century.[140]

Symbolism, meaning and interpretations

Historically, the myth of the Gigantomachy (as well as the Titanomachy) may reflect the "triumph" of the new imported gods of the invading Greek speaking peoples from the north (c. 2000 BC) over the old gods of the existing peoples of the Greek peninsula.[141] For the Greeks, the Gigantomachy represented a victory for order over chaos—the victory of the divine order and rationalism of the Olympian gods over the discord and excessive violence of the earth-born chthonic Giants. More specifically, for sixth and fifth century BC Greeks, it represented a victory for civilization over barbarism, and as such was used by Phidias on the metopes of the Parthenon and the shield of Athena Parthenos to symbolize the victory of the Athenians over the Persians. Later the Attalids similarly used the Gigantomachy on the Pergamon Altar to symbolize their victory over the Galatians of Asia Minor.[142]

The attempt of the Giants to overthrow the Olympians also represented the ultimate example of hubris, with the gods themselves punishing the Giants for their arrogant challenge to the gods' divine authority.[143] The Gigantomachy can also be seen as a continuation of the struggle between Gaia (Mother Earth) and Uranus (Father Sky), and thus as part of the primal opposition between female and male.[144] Plato compares the Gigantomachy to a philosophical dispute about existence, wherein the materialist philosophers, who believe that only physical things exist, like the Giants, wish to "drag down everything from heaven and the invisible to earth".[145]

In Latin literature, in which the Giants, the Titans, Typhon and the Aloadae are all often conflated, Gigantomachy imagery is a frequent occurrence.[147] Cicero, while urging the acceptance of aging and death as natural and inevitable, allegorizes the Gigantomachy as "fighting against Nature".[148] The rationalist Epicurean poet Lucretius, for whom such things as lightning, earthquakes and volcanic eruptions had natural rather than divine causes, used the Gigantomachy to celebrate the victory of philosophy over mythology and superstition. In the triumph of science and reason over traditional religious belief, the Gigantomachy symbolized for him Epicurus storming heaven. In a reversal of their usual meaning, he represents the Giants as heroic rebels against the tyranny of Olympus.[149] Virgil—reversing Lucretius' reversal—restores the conventional meaning, making the Giants once again enemies of order and civilization.[150] Horace makes use of this same meaning to symbolize the victory of Augustus at the Battle of Actium as a victory for the civilized West over the barbaric East.[151]

Ovid, in his Metamorphoses, describes mankind's moral decline through the ages of gold, silver, bronze and iron, and presents the Gigantomachy as a part of that same descent from natural order into chaos.[152] Lucan, in his Pharsalia, which contains many Gigantomachy references,[153] makes the Gorgon's gaze turn the Giants into mountains.[154] Valerius Flaccus, in his Argonautica, makes frequent use of Gigantomachy imagery, with the Argo (the world's first ship) constituting a Gigantomachy-like offense against natural law, and example of hubristic excess.[155]

Claudian, the fourth-century AD court poet of emperor Honorius, composed a Gigantomachia that viewed the battle as a metaphor for vast geomorphic change: "The puissant company of the giants confounds all differences between things; islands abandon the deep; mountains lie hidden in the sea. Many a river is left dry or has altered its ancient course....robbed of her mountains Earth sank into level plains, parted among her own sons."[156]

Association with volcanoes and earthquakes

Various locations associated with the Giants and the Gigantomachy were areas of volcanic and seismic activity (e.g. the Phlegraean Fields west of Naples), and the vanquished Gigantes (along with other "giants") were said to be buried under volcanos. Their subterranean movements were said to be the cause of volcanic eruptions and earthquakes.[157]

The Giant Enceladus was thought to lay buried under Mount Etna, the volcano's eruptions being the breath of Enceladus, and its tremors caused by the Giant rolling over from side to side beneath the mountain[158] (the monster Typhon[159] and the Hundred-Hander Briareus[160] were also said to be buried under Etna). The Giant Alcyoneus along with "many giants" were said to lie under Mount Vesuvius,[161] Prochyte (modern Procida), one of the volcanic Phlegraean Islands was supposed to sit atop the Giant Mimas,[162] and Polybotes was said to lie pinned beneath the volcanic island of Nisyros, supposedly a piece of the island of Kos broken off and thrown by Poseidon.[163]

Describing the catastrophic eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD, which buried the towns of Pompeii and Herculaneum, Cassius Dio relates accounts of the appearance of many Giant-like creatures on the mountain and in the surrounding area followed by violent earthquakes and the final cataclysmic eruption, saying "some thought that the Giants were rising again in revolt (for at this time also many of their forms could be discerned in the smoke and, moreover, a sound as of trumpets was heard)".[164]

Named Giants

Names for the Giants can be found in ancient literary sources and inscriptions. Vian and Moore provide a list with over seventy entries, some of which are based upon inscriptions which are only partially preserved.[165] Some of the Giants identified by name are:

- Aezeius: father of Lycaon, possibly the maternal grandfather of Lycaon, the King of Arcadia.[166][167]

- Agrius: According to Apollodorus, he was killed by the Moirai (Fates) with bronze clubs.[168]

- Alcyoneus: According to Apollodorus, he was (along with Porphyrion), the greatest of the Giants. Immortal while fighting in his native land, he was dragged from his homeland and killed by Heracles.[169] According to Pindar, he was a herdsman and, in a separate battle from the Gigantomachy, he was killed by Heracles and Telamon, while they were traveling through Phlegra.[170] Representations of Heracles fighting Alcyoneus are found on many sixth century BC and later works of art.[171]

- Alektos/Allektos: Named on the late sixth century Siphnian Treasury (Alektos),[172] and the second century BC Pergamon Altar (Allektos).[173]

- Aristaeus: According to the Suda, he was the only Giant to "survive".[174] He is probably named on an Attic black-figure dinos by Lydos (Akropolis 607) dating from the second quarter of the sixth century BC, fighting Hephaestus.[175]

- Astarias [See Asterius below]

- Aster [See Asterius below]

- Asterius ("Bright One" or "Glitterer"):[176] A Giant (also called Aster), killed by Athena whose death, according to some accounts, was celebrated by the Panathenaea.[177] Probably the same as the Giant Astarias named on the late sixth century Siphnian Treasury.[178] Probably also the same as Asterus, mentioned in the epic poem Meropis, as an invulnerable warrior killed by Athena.[179] In the poem, Heracles, while fighting the Meropes, a race of Giants, on the Island of Kos, would have been killed but for Athena's intervention.[180] Athena kills and flays Asterus and uses his impenetrable skin for her aegis. Other accounts name others whose hide provided Athena's aegis:[181] Apollodorus has Athena flay the Giant Pallas,[182] while Euripides' Ion has Gorgon, here considered to be a Giant, as Athena's victim.[183]

- Asterus [See Asterius above]

- Clytius: According to Apollodorus, he was killed by Hecate with her torches.[184]

- Damysus: The fastest of the Giants. Chiron exhumed his body, removed the ankle and incorporated it into Achilles burnt foot.[185]

- Enceladus: A Giant named Enceladus, fighting Athena, is attested in art as early as an Attic Black-figure pot dating from the second quarter of the sixth century BC (Louvre E732).[186] Euripides has Athena fighting him with her "Gorgon shield" (her aegis).[187] According to Apollodorus, he was crushed by Athena under the Island of Sicily.[188] Virgil has him struck by Zeus' lightning bolt, and both Virgil and Claudian have him buried under Mount Etna[189] (other traditions had Typhon or Briareus buried under Etna). For some Enceladus was instead buried in Italy.[190]

- Ephialtes (probably different from the Aload Giant who was also named Ephialtes):[191] According to Apollodorus he was blinded by arrows from Apollo and Heracles.[192] He is named on three Attic black-figure pots (Akropolis 2134, Getty 81.AE.211, Louvre E732) dating from the second quarter of the sixth century BC.[193] On Louvre E732 he is, along with Hyperbios and Agasthenes, opposed by Zeus, while on Getty 81.AE.211 his opponents are apparently Apollo and Artemis.[194] He is also named on the late sixth century BC Siphnian Treasury,[195] where he is probably one of the opponents of Apollo and Artemis, and probably as well on what might be the earliest representation of the Gigantomachy, a pinax fragment from Eleusis (Eleusis 349).[196] He is also named on a late fifth century BC cup from Vulci (Berlin F2531), shown battling Apollo.[197] Although the usual opponent of Poseidon among the Giants is Polybotes, one early fifth century red-figure column krater (Vienna 688) has Poseidon attacking Ephialtes.[198]

- Euryalus: He is named on a late sixth century red-figure cup (Akropolis 2.211) and an early fifth century red-figure cup (British Museum E 47) fighting Hephaestos.[199]

- Eurymedon: According to Homer, he was a king of the Giants and father of Periboea (mother of Nausithous, king of the Phaeacians, by Poseidon), who "brought destruction on his froward people".[200] He was possibly the Eurymedon who raped Hera producing Prometheus as offspring (according to an account attributed to the Hellenistic poet Euphorion).[201] He is probably named on Akropolis 2134.[202] He is possibly mentioned by the Latin poet Propertius as an opponent of Jove.[203]

- Eurytus: According to Apollodorus, he was killed by Dionysus with his thyrsus.[204]

- Gration: According to Apollodorus, he was killed by Artemis.[205] His name may have been corrupted text, as various emendations have been suggested, including Aigaion (Αἰγαίων - "goatish", "stormy"), Eurytion (Εὐρυτίων - "fine flowing", "widely honored") and Rhaion (Ῥαίων - "more adaptable", "more relaxed").[206]

- Hopladamas or Hopladamus: Possibly named (as Hoplodamas) on two vases dating from the second quarter of the sixth century BC, on one (Akropolis 607) being speared by Apollo, while on the other (Getty 81.AE.211) attacking Zeus.[207] Mentioned (as Hopladamus) by the geographer Pausanias as being a leader of Giants enlisted by the Titaness Rhea, pregnant with Zeus, to defend herself from her husband Cronus.[208]

- Hippolytus: According to Apollodorus, he was killed by Hermes, who was wearing Hades' helmet[209] which made its wearer invisible.[210]

- Lion or Leon: Possibly a Giant, he is mentioned by Photius (as ascribed to Ptolemy Hephaestion) as a giant who was challenged to single combat by Heracles and killed.[211] Lion-headed Giants are shown on the Gigantomachy frieze of the second century BC Pergamon Altar.[212]

- Mimas: According to Apollodorus, he was killed by Hephaestus.[213] Euripides has Zeus burning him "to ashes" with his thunderbolt.[214] According to others he was killed by Ares.[215] "Mimos"—possibly in error for "Mimas"—is inscribed (retrograde) on Akropolis 607.[216] He was said to be buried under Prochyte.[217] Mimas is possibly the same as the Giant named Mimon on the late sixth century BC Siphnian Treasury, as well as on a late fifth century BC cup from Vulci (Berlin F2531) shown fighting Ares.[218] Several depictions in Greek art, though, show Aphrodite as the opponent of Mimas.[219]

- Mimon [See Mimas above]

- Mimos [See Mimas above]

- Pallas: According to Apollodorus, he was flayed by Athena, who used his skin as a shield.[221] Other accounts name others whose hyde provided Athena's aegis:[222] the epic poem Meropis has Athena kill and flay the Giant Asterus (see Asterius above) while Euripides' Ion has Gorgon, here considered to be a Giant, as Athena's victim.[223] Claudian names him as one of several Giants turned to stone by Minerva's Gorgon shield.[224]

- Pelorus: According to Claudian, he was killed by Mars, the Roman equivalent of Ares.[225]

- Picolous: A Giant who fled the battle and came to Circe's island and attempted to chase her away, only to be killed by Helios. It is said that the legendary moly plant first sprang forth from Picolous' blood as it seeped into the ground.[226]

- Polybotes: According to Apollodorus, he was crushed under Nisyros, a piece of the island of Kos broken off and thrown by Poseidon.[227] He is named on two sixth century BC pots, on one (Getty 81.AE.211) he is opposed by Zeus, on the other (Louvre E732) he is opposed by Poseidon carrying Nisyros on his shoulder.[228]

- Porphyrion: According to Apollodorus, he was (along with Alcyoneus), the greatest of the Giants. He attacked Heracles and Hera but Zeus "smote him with a thunderbolt, and Hercules shot him dead with an arrow."[229] According to Pindar, who calls him "king of the Giants", he was slain by an arrow from the bow of Apollo.[230] He is named on a late fifth century BC cup from Vulci (Berlin F2531), where he is battling with Zeus.[231] He was also probably named on the late sixth century BC Siphnian Treasury.[232]

- Thoas (or Thoon?): According to Apollodorus, he was killed by the Moirai (Fates) with bronze clubs.[233]

See also

Notes

- Parada, s.v. Thoas 5; Grant, pp. 519–520; Smith, s.v. Thoon; Apollodorus, 1.6.2. Frazer translates Apollodorus 1.6.2 Θόωνα as "Thoas". Citing only Apollodorus 1.6.2, Parada names the Giant "Thoas" (Θόας), and Smith names the Giant "Thoon (Θόων)". Grant, citing no sources, names the Giant "Thoas", but says "he was also called Thoon".

References

- Aeschylus, The Eumenides in Aeschylus, with an English translation by Herbert Weir Smyth, Ph. D. in two volumes. Vol 2. Cambridge, Massachusetts. Harvard University Press. 1926. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Aeschylus (?), Prometheus Bound in Aeschylus, with an English translation by Herbert Weir Smyth, Ph. D. in two volumes. Vol 2. Cambridge, Massachusetts. Harvard University Press. 1926. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Anderson, William S., Ovid's Metamorphoses, Books 1-5, University of Oklahoma Press, 1997. ISBN 9780806128948.

- Andrews, Tamra, Dictionary of Nature Myths: Legends of the Earth, Sea, and Sky, Oxford University Press, 2000. ISBN 9780195136777.

- Apollodorus, Apollodorus, The Library, with an English Translation by Sir James George Frazer, F.B.A., F.R.S. in 2 Volumes. Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1921. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Apollonius of Rhodes, Apollonius Rhodius: the Argonautica, translated by Robert Cooper Seaton, W. Heinemann, 1912. Internet Archive

- Arafat, K. W., Classical Zeus: A Study in Art and Literature, Oxford: Clarendon Press 1990. ISBN 0-19-814912-3.

- Aristophanes, Birds in The Complete Greek Drama, vol. 2. Eugene O'Neill, Jr. New York. Random House. 1938. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Aristophanes, Knights in The Complete Greek Drama, vol. 2. Eugene O'Neill, Jr. New York. Random House. 1938. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Barber, E. J. W. (1991), Prehistoric Textiles: The Development of Cloth in the Neolithic and Bronze Ages with Special Reference to the Aegean, Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691002248.

- Barber, E. J. W. (1992), "The Peplos of Athena" in Goddess and Polis: The Panathenaic Festival in Ancient Athens, Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691002231.

- Bacchylides, Odes Translated by Diane Arnson Svarlien. 1991. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Batrachomyomachia in Hesiod, the Homeric hymns, and Homerica with an English translation by Hugh G. Evelyn-White, W. Heinemann, The Macmillan Co. in London, New York. 1914. Internet Archive

- Beazley, John D., The Development of Attic Black-Figure, Revised edition, University of California Press, 1986. ISBN 9780520055933. Online version at University of California Press E-Books Collection

- Brill's New Pauly. Antiquity volumes edited by: Hubert Cancik and, Helmuth Schneider. Brill Online, 2014. Reference. 1 March 2014 "Gegeneis"

- Brinkmann, Vinzenz, "Die aufgemalten Namensbeischriften an Nord- und Ostfries des Siphnierschatzhauses", Bulletin de Correspondance Hellénique 109 77-130 (1985).

- Brown, John Pairman, Israel and Hellas, Walter de Gruyter, 1995. ISBN 9783110142334.

- Burkert, Walter (1991), Greek Religion, Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN 978-0631156246

- Cairns, Francis, Roman Lyric: Collected Papers on Catullus and Horace, Walter de Gruyter, 2012. ISBN 9783110267228.

- Callimachus, Hymn 4 (to Delos) in Callimachus and Lycophron with an English translation by A. W. Mair ; Aratus, with an English translation by G. R. Mair, London: W. Heinemann, New York: G. P. Putnam 1921. Internet Archive

- Castriota, David, Myth, Ethos, and Actuality: Official Art in Fifth-century B.C. Athens, Univ of Wisconsin Press, 1992. ISBN 9780299133542.

- Chaudhuri, Pramit, The War with God: Theomachy in Roman Imperial Poetry, Oxford University Press, 2014. ISBN 9780199993390.

- Cicero, On Old Age On Friendship On Divination, translation by William Armistead Falconer. Loeb Classical Library Volume 154. Cambridge, Massachusetts. Harvard University Press. 1923. ISBN 978-0674991705.

- Claudian, Claudian with an English translation by Maurice Platnauer, Volume II, Loeb Classical Library No. 136. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press; London: William Heinemann, Ltd.. 1922. ISBN 978-0674991514. Internet Archive.

- Cohen, Beth, "Outline as a Special Technique in Black- and Red-figure Vase-painting", in The Colors of Clay: Special Techniques in Athenian Vases, Getty Publications, 2006, ISBN 9780892369423.

- Commager, Steele, The Odes of Horace: A Critical Study, University of Oklahoma Press, 1995. ISBN 9780806127293.

- Conington, John, The works of Virgil, with a Commentary by John Conington, M.A. Late Corpus Professor of Latin in the University of Oxford. London. Whittaker and Co., Ave Maria Lane. 1876.

- Connelly, Joan Breton, The Parthenon Enigma, Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 2014. ISBN 978-0385350501.

- Cook, Arthur Bernard, Zeus: A Study in Ancient Religion, Volume III: Zeus God of the Dark Sky (Earthquakes, Clouds, Wind, Dew, Rain, Meteorites), Part I: Text and Notes, Cambridge University Press 1940. Internet Archive

- Cunningham, Lawrence, John Reich, Lois Fichner-Rathus, Culture and Values: A Survey of the Western Humanities, Volume 1, Cengage Learning, 2014. ISBN 9781285974460.

- Day, Joseph W., Archaic Greek Epigram and Dedication: Representation and Reperformance, Cambridge University Press, 2010. ISBN 9780521896306.

- de Grummond, Nancy Thomson, "Gauls, Giants, Skylla, and the Palladion" in From Pergamon to Sperlonga: Sculpture and Context, Nancy Thomson de Grummond, Brunilde Sismondo Ridgway, editors, University of California Press, 2000. ISBN 9780520223271.

- Dinter, Martin, "Lucan's Epic Body" in Lucan im 21. Jahrhundert, Christine Walde editor, Walter de Gruyter, 2005. ISBN 9783598730269.

- Diodorus Siculus, Diodorus Siculus: The Library of History. Translated by C. H. Oldfather. Twelve volumes. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press; London: William Heinemann, Ltd. 1989.

- Durling, Robert M., The Divine Comedy of Dante Alighieri : Volume 1: Inferno, Oxford University Press, 1996. ISBN 9780195087444.

- Dwyer, Eugene, "Excess" in Encyclopedia of Comparative Iconography: Themes Depicted in Works of Art, edited by Helene E. Roberts, Routledge, 2013, ISBN 9781136787935.

- Ellis, Robinson, Aetna: A Critical Recension of the Text, Based on a New Examination of Mss. With Prolegomena, Translation, Textual and Exegetical Commentary, Excursus, and Complete Index of the Words, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1901.

- Euripides, Hecuba, translated by E. P. Coleridge in The Complete Greek Drama, edited by Whitney J. Oates and Eugene O'Neill, Jr. Volume 1. New York. Random House. 1938.

- Euripides, Heracles, translated by E. P. Coleridge in The Complete Greek Drama, edited by Whitney J. Oates and Eugene O'Neill, Jr. Volume 1. New York. Random House. 1938.

- Euripides, Iphigenia in Tauris, translated by Robert Potter in The Complete Greek Drama, edited by Whitney J. Oates and Eugene O'Neill, Jr. Volume 2. New York. Random House. 1938.

- Euripides, Ion, translated by Robert Potter in The Complete Greek Drama, edited by Whitney J. Oates and Eugene O'Neill, Jr. Volume 1. New York. Random House. 1938.

- Euripides, The Phoenician Women, translated by E. P. Coleridge in The Complete Greek Drama, edited by Whitney J. Oates and Eugene O'Neill, Jr. Volume 2. New York. Random House. 1938.

- Ferrari, Gloria, Alcman and the Cosmos of Sparta, University of Chicago Press, 2008. ISBN 9780226668673.

- Frazer, J. G. (1898a), Pausanias's Description of Greece. Translated with a Commentary by J. G. Frazer. Vol II. Commentary on Book I, Macmillan, 1898. Internet Archive.

- Frazer, J. G. (1898b), Pausanias's Description of Greece. Translated with a Commentary by J. G. Frazer. Vol IV. Commentary on Books VI-VIII, Macmillan, 1898. Internet Archive.

- Frazer, J. G. (1914), Adonis Attis Osiris: Studies in the History of Oriental Religion, Macmillan and Co., Limited, London 1914. Internet Archive

- Fontenrose, Joseph Eddy, Python: A Study of Delphic Myth and Its Origins, University of California Press, 1959. ISBN 9780520040915.

- Gantz, Timothy, Early Greek Myth: A Guide to Literary and Artistic Sources, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996, Two volumes: ISBN 978-0-8018-5360-9 (Vol. 1), ISBN 978-0-8018-5362-3 (Vol. 2).

- Gale, Monica, Virgil on the Nature of Things: The Georgics, Lucretius and the Didactic Tradition, Cambridge University Press, 2000. ISBN 9781139428477.

- Gee, Emma, Ovid, Aratus and Augustus: Astronomy in Ovid's Fasti, Cambridge University Press, 2000. ISBN 9780521651875.

- Grant, Michael, John Hazel, Who's Who in Classical Mythology, Routledge, 2004. ISBN 9781134509430.

- Green, Steven, J., Ovid, Fasti 1: A Commentary, BRILL, 2004. ISBN 9789004139855.

- Grimal, Pierre, The Dictionary of Classical Mythology, Wiley-Blackwell, 1996, ISBN 9780631201021.

- Hanfmann, George, M. A. (1937), "Studies in Etruscan Bronze Reliefs: The Gigantomachy", The Art Bulletin 19:463-85. 1937.

- George M. A. Hanfmann (1992), "Giants" in The Oxford Classical Dictionary, second edition, Hammond, N.G.L. and Howard Hayes Scullard (editors), Oxford University Press, 1992. ISBN 0-19-869117-3.

- Hansen, William, Handbook of Classical Mythology, ABC-CLIO, 2004. ISBN 978-1576072264.

- Hard, Robin (2015). Constellation Myths: With Aratus's 'Phaenomena'. Oxford World's Classics. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-871698-3.

- Hard, Robin, The Routledge Handbook of Greek Mythology: Based on H.J. Rose's "Handbook of Greek Mythology", Psychology Press, 2004, ISBN 9780415186360.

- Hardie, Philip (2007), "Lucretius and later Latin literature in antiquity", in The Cambridge Companion to Lucretius, edited by Stuart Gillespie, Philip Hardie, Cambridge University Press, 2007. ISBN 9781139827522.

- Hardie, Philip (2014), The Last Trojan Hero: A Cultural History of Virgil's Aeneid, I.B.Tauris, 2014. ISBN 9781780762470.

- Hesiod, Theogony, in The Homeric Hymns and Homerica with an English Translation by Hugh G. Evelyn-White, Cambridge, Massachusetts.,Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1914. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Hesiod, Shield of Heracles, in The Homeric Hymns and Homerica with an English Translation by Hugh G. Evelyn-White, Cambridge, Massachusetts.,Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1914. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Heyworth, S. J., Cynthia : A Companion to the Text of Propertius, Oxford University Press, 2007. ISBN 9780191527920.

- Homer, The Iliad with an English Translation by A.T. Murray, Ph.D. in two volumes. Cambridge, Massachusetts., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann, Ltd. 1924. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Homer, The Odyssey of Homer, translated by Lattimore, Richard, Harper Perennial Modern Classics, 2006. ISBN 978-0061244186.

- Homer, The Odyssey with an English Translation by A.T. Murray, PH.D. in two volumes. Cambridge, Massachusetts., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann, Ltd. 1919. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Horace, The Odes and Carmen Saeculare of Horace. John Conington. trans. London. George Bell and Sons. 1882. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Hunter, Richard L., The Hesiodic Catalogue of Women, Cambridge University Press, 2008. ISBN 9781139444040.

- Hurwit, Jeffery M., The Athenian Acropolis: History, Mythology, and Archaeology from the Neolithic Era to the Present, Cambridge University Press, 1999. ISBN 0-521-41786-4.

- Hyginus, Gaius Julius, Fabulae, in The Myths of Hyginus, edited and translated by Mary A. Grant, Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 1960. Online version at ToposText.

- Janko, Richard, The Iliad: A Commentary: Volume 4, Books 13-16, Cambridge University Press, 1992. ISBN 978-0521237123.

- Keith, A. M., Propertius: Poet of Love and Leisure, A&C Black, 2008. ISBN 9780715634530.

- Kerenyi, Karl (1951). The Gods of the Greeks. London, UK: Thames and Hudson.

- Kirk, G. S., J. E. Raven, M. Schofield, The Presocratic Philosophers: A Critical History with a Selection of Texts, Cambridge University Press, Dec 29, 1983. ISBN 9780521274555.

- Kleiner, Fred S., Gardner's Art Through the Ages: A Global History, Fourteenth Edition, Cengage Learning, 2012. ISBN 9781285288673.

- Knox, Peter, A Companion to Ovid, Wiley-Blackwell, 2012. ISBN 978-1118451342.

- Lemprière, John, A Classical Dictionary, E. Duyckinck, G. Long, 1825.

- Lapatin, Kenneth, "The Statue of Athena and Other Treasures in the Parthenon" in The Parthenon: From Antiquity to the Present, edited by Jenifer Neils, Cambridge University Press, 2005. ISBN 9780521820936.

- Leigh, Matthew, Lucan: Spectacle and Engagement, Oxford University Press, 1997. ISBN 9780198150671.

- Lescher, James H., Xenophanes of Colophon: Fragments : a Text and Translation with a Commentary, University of Toronto Press, 2001. ISBN 9780802085085.

- Liddell, Henry George, Robert Scott. A Greek-English Lexicon. Revised and augmented throughout by Sir Henry Stuart Jones with the assistance of. Roderick McKenzie. Oxford. Clarendon Press. 1940. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library

- Lightfoot, J. L., Hellenistic Collection: Philitas, Alexander of Aetolia, Hermesianax, Euphorion, Parthenius Harvard University Press, 2009. ISBN 9780674996366.

- Ling, Roger, The Cambridge Ancient History: Plates to Volume VII Part 1, Cambridge University Press, 1984. ISBN 9780521243544.

- Lovatt, Helen, Statius and Epic Games: Sport, Politics and Poetics in the Thebaid, Cambridge University Press, 2005. ISBN 9780521847421.

- Lucan, Pharsalia, Sir Edward Ridley. London. Longmans, Green, and Co. 1905. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Lucretius, De Rerum Natura, William Ellery Leonard, Ed. Dutton. 1916.

- Lyne, R. O. A. M., Horace: Behind the Public Poetry, Yale University Press, 1995. ISBN 9780300063226.

- Lycophron, Alexandra (or Cassandra) in Callimachus and Lycophron with an English translation by A. W. Mair ; Aratus, with an English translation by G. R. Mair, London: W. Heinemann, New York: G. P. Putnam 1921 . Internet Archive

- Manilius, Astronomica, edited and translated by G. P. Goold. Loeb Classical Library No. 469. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1977. Online version at Harvard University Press

- Mayor, Adrienne, The First Fossil Hunters: Dinosaurs, Mammoths, and Myth in Greek and Roman Times, Princeton University Press, 2011. ISBN 9781400838448.

- McKay, Kenneth John, Erysichthon, Brill Archive, 1962.

- Merry, W. Walter, James Riddell, D, B, Monro, Homer's Odyssey, Clarendon Press. 1886–1901.

- Mineur, W. H., Callimachus: Hymn to Delos, Brill Archive, 1984. ISBN 9789004072305.

- Moore, Mary B. (1979), "Lydos and the Gigantomachy" in American Journal of Archaeology 83 (1979) 79–99.

- Moore, Mary B. (1985), "Giants at the Getty" in Greek Vases in the J. Paul Getty Museum Volume 2, Getty Publications.

- Moore, Mary B. (1997), "The Gigantomachy of the Siphnian Treasury: Reconstruction of the three Lacunae" in Bulletin de correspondance hellénique, Suppl. 4, 1977. pp. 305–335.

- Morford, Mark P. O., Robert J. Lenardon, Classical Mythology, Eighth Edition, Oxford University Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0-19-530805-1.

- Most, G.W. (2006), Hesiod: Theogony, Works and Days, Testimonia, Loeb Classical Library, vol. no. 57, Cambridge, Massachusetts, ISBN 978-0-674-99622-9.

- Most, G.W. (2007), Hesiod: The Shield, Catalogue of Women, Other Fragments, Loeb Classical Library, vol. no. 503, Cambridge, Massachusetts, ISBN 978-0-674-99623-6. English translation with facing Greek text; takes much recent scholarship into consideration.

- Neils, Jenifer, "Chapter Twelve: Athena, Alter Ego of Zeus" in Athena in the Classical World, edited by Susan Deacy, Alexandra Villing, Brill Academic Pub, 2001, ISBN 9789004121423.

- Newlands, Carole E., An Ovid Reader: Selections from Seven Works, Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers, 2014. ISBN 9781610411189.

- Nonnus, Dionysiaca; translated by Rouse, W H D, I Books I–XV. Loeb Classical Library No. 344, Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1940. Internet Archive

- Ogden, Daniel, Drakon: Dragon Myth and Serpent Cult in the Greek and Roman Worlds, Oxford University Press, 2013. ISBN 9780199557325.

- O'Hara, James J., Inconsistency in Roman Epic: Studies in Catullus, Lucretius, Vergil, Ovid and Lucan, Cambridge University Press, 2007. ISBN 9781139461320.

- Ovid, Amores, Christopher Marlowe, Ed. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library

- Ovid, Ovid's Fasti: With an English translation by Sir James George Frazer, London: W. Heinemann LTD; Cambridge, Massachusetts: : Harvard University Press, 1959. Internet Archive.

- Ovid, Metamorphoses, Brookes More. Boston. Cornhill Publishing Co. 1922. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Parada, Carlos, Genealogical Guide to Greek Mythology, Jonsered, Paul Åströms Förlag, 1993. ISBN 978-91-7081-062-6.

- Parker, Robert B. (2006), Polytheism and Society at Athens. Oxford, GBR: Oxford University Press, UK. ISBN 978-0199274833.

- Parker, Robert B. (2011), On Greek Religion, Cornell University Press, ISBN 978-0801462016.

- Pausanias, Pausanias Description of Greece with an English Translation by W.H.S. Jones, Litt.D., and H.A. Ormerod, M.A., in 4 Volumes. Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1918. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Peck, Harry Thurston, Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities, New York. Harper and Brothers. 1898. "Gigantes"

- Philostratus, The Life of Apollonius of Tyana: Volume I. Books 1-5, translated by F.C. Conybeare, Loeb Classical Library No. 16. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts. 1912. ISBN 978-0674990180. Internet Archive

- Philostratus, On Heroes, editors Jennifer K. Berenson MacLean, Ellen Bradshaw Aitken, BRILL, 2003, ISBN 9789004127012.

- Philostratus the Elder, Imagines, translated by A. Fairbanks, Loeb Classical Library No, 256. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts. 1931. ISBN 978-0674992825. Internet Archive

- Pindar, Odes, Diane Arnson Svarlien. 1990. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Plato, Euthyphro in Plato in Twelve Volumes, Vol. 1, translated by Harold North Fowler, Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1966.

- Plato, Republic in Plato in Twelve Volumes, Vols. 5 & 6, translated by Paul Shorey. Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1969.

- Plato, Sophist in Plato in Twelve Volumes, Vol. 12 translated by Harold N. Fowler. Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1921.

- Plumptre, Edward Hayes, Æschylos: Tragedies and Fragments, Heath, 1901.

- Powell, J. G. F., Cicero: Cato Maior de Senectute, Cambridge University Press, 1988. ISBN 9780521335010.

- Propertius, The Complete Elegies of Sextus Propertius, translated by Vincent Katz, Princeton University Press, 2004. ISBN 9780691115825.

- Rahner, Hugo, Greek Myths and Christian Mystery New York Biblo & Tannen Publishers, 1971.

- Richards, G.C., "Selected Vase-fragments from the Acropolis of Athens—I", The Journal of Hellenic Studies 13, The Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies, 1893, pp. 281–292.

- Ridgway, Brunilde Sismondo (2000), Hellenistic Sculpture II: The Styles of ca. 200-100 B.C., University of Wisconsin Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0299167103.

- Ridgway, Brunilde Sismondo (2005), Review of François Queyrel, L'Autel de Pergame. Images et pouvoir en Grèce d'Asie. Antiqua vol. 9. in Bryn Mawr Classical Review, 2005.08.39

- Ridgway, David, The First Western Greeks, CUP Archive, 1992. ISBN 9780521421645.

- Rose, Herbert Jennings, "Typhon, Typhoeus" in The Oxford Classical Dictionary, second edition, Hammond, N.G.L. and Howard Hayes Scullard (editors), Oxford University Press, 1992. ISBN 0-19-869117-3.

- Queyrel, François, L'Autel de Pergame: Images et pouvoir en Grèce d'Asie, Paris: Éditions A. et J. Picard, 2005. ISBN 2-7084-0734-1.

- Quintus Smyrnaeus, Quintus Smyrnaeus: The Fall of Troy, Translator: A.S. Way; Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA, 1913. Internet Archive

- Robertson, Martin, A Shorter History of Greek Art, Cambridge University Press, 1981. ISBN 9780521280846.

- Robertson, Noel, "Chapter Two: Athena as Weather-Goddess: the Aigis in Myth and Ritual" in Athena in the Classical World, edited by Susan Deacy, Alexandra Villing, Brill Academic Pub, 2001, ISBN 9789004121423.

- Pollitt, Jerome Jordan (1986), Art in the Hellenistic Age, Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521276726.

- Pollitt, Jerome Jordan (1990), The Art of Ancient Greece: Sources and Documents, Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521273664.

- Schefold, Karl, Luca Giuliani, Gods and Heroes in Late Archaic Greek Art, Cambridge University Press, 1992 ISBN 9780521327183.

- Scheid, John, Jesper Svenbro, The Craft of Zeus: Myths of Weaving and Fabric, Penn State Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0674005785.

- Schwab, Katherine A., "Celebrations of victory: The Metopes of the Parthenon" in The Parthenon: From Antiquity to the Present, edited by Jenifer Neils, Cambridge University Press, 2005. ISBN 9780521820936.

- Seneca, Tragedies, Volume I: Hercules. Trojan Women. Phoenician Women. Medea. Phaedra. Edited and translated by John G. Fitch. Loeb Classical Library No. 62. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2002. ISBN 978-0-674-99602-1. Online version at Harvard University Press.

- Seneca, Tragedies, Volume II: Oedipus. Agamemnon. Thyestes. Hercules on Oeta. Octavia. Edited and translated by John G. Fitch. Loeb Classical Library No. 78. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0-674-99610-6. Online version at Harvard University Press.

- Shapiro, H. A., The Cambridge Companion to Archaic Greece, Cambridge University Press, 2007. ISBN 9781139826990.

- Silius Italicus, Punica with an English translation by J. D. Duff, Volume I, Cambridge, Massachusetts., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann, Ltd. 1927. Internet Archive

- Silius Italicus, Punica with an English translation by J. D. Duff, Volume II, Cambridge, Massachusetts., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann, Ltd. 1934. Internet Archive

- Simon, Erika, "Theseus and Athenian Festivals" in Worshipping Athena: Panathenaia and Parthenon, edited by Jenifer Neils, Univ of Wisconsin Press, 1996. ISBN 9780299151140.

- Singleton, George S. The Divine Comedy, Inferno 2: Commentary, Princeton University Press, 1989 ISBN 9780691018959.

- Smith, R. R. R., Hellenistic Sculpture: a handbook, Thames and Hudson, 1991. ISBN 9780500202494.

- Smith, William, Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, London (1873). "Gigantes"

- Sophocles, Women of Trachis, Translated by Robert Torrance. Houghton Mifflin. 1966. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Statius, Statius with an English Translation by J. H. Mozley, Volume II, Thebaid, Books V–XII, Achilleid, Loeb Classical Library No. 207, London: William Heinemann, Ltd., New York: G. P. Putnamm's Sons, 1928. ISBN 978-0674992283. Internet Archive

- Stewart, Andrew F., Greek Sculpture: An Exploration, Yale University Press, 1990.

- Stover, Epic and Empire in Vespasianic Rome: A New Reading of Valerius Flaccus' Argonautica, Oxford University Press, 2012. ISBN 9780199644087.

- Strabo, Geography, translated by Horace Leonard Jones; Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press; London: William Heinemann, Ltd. (1924). LacusCurtis, Books 6–14, at the Perseus Digital Library

- Torrance, Isabelle, Metapoetry in Euripides, Oxford University Press, 2013. ISBN 9780199657834.

- Tripp, Edward, Crowell's Handbook of Classical Mythology, Thomas Y. Crowell Co; First edition (June 1970). ISBN 069022608X.

- Valerius Flaccus, Gaius, Argonautica, translated by J. H. Mozley, Loeb Classical Library Volume 286. Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1928.

- Vian, Francis (1951), Répertoire des gigantomachie figurées dans l'art grec et romain (Paris).

- Vian, Francis (1952), La guerre des Géants: Le mythe avant l'epoque hellenistique, (Paris).

- Vian, Francis, Moore, Mary B. (1988), "Gigantes" in Lexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae (LIMC) IV.1. Artemis Verlag, Zürich and Munich, 1988. ISBN 3760887511.

- Virgil, Aeneid, Theodore C. Williams. trans. Boston. Houghton Mifflin Co. 1910. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library

- Wheeler, Stephen Michael, Narrative Dynamics in Ovid's Metamorphoses, Gunter Narr Verlag, 2000. ISBN 9783823348795.

- Wilkinson, Claire Louise, The Lyric of Ibycus: Introduction, Text and Commentary, Walter de Gruyter, 2012. ISBN 9783110295146.

- Yasumura, Noriko, Challenges to the Power of Zeus in Early Greek Poetry, Bloomsbury Academic, 2013. ISBN 978-1472504470.

- Zissos, Andrew, "Sailing and Sea-Storm in Valerius Flaccus (Argonautica 1.574–642): The Rhetoric of Inundation" in Flavian Poetry, Ruurd Robijn Nauta, Harm-Jan Van Dam, Johannes Jacobus Louis Smolenaars (editors), BRILL, 2006. ISBN 9789004147942.

- Zucker, Arnaud, Clair Le Feuvre, Ancient and Medieval Greek Etymology: Theory and Practice I, Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG, 2021.

External links

- Gigantes – Theoi Project

- Gigantomachy: Sculpture & Vase Representations - Wesleyan

- The Siphnian Treasury: The North side of the frieze (The Gigantomachy - Hall V)

- Gigantes

- Deeds of Aphrodite

- Deeds of Apollo

- Deeds of Artemis

- Deeds of Athena

- Deeds of Demeter

- Deeds of Hera

- Deeds of Poseidon

- Deeds of Zeus

- Dionysus in mythology

- Helios in mythology

- Mythology of Heracles

- Ancient Greek military art

- Children of Gaia

- Deeds of Gaia

- Deeds of Hermes

- Deeds of Ares

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Giants_(Greek_mythology)

Stephanus or Stephen of Byzantium (Latin: Stephanus Byzantinus; Greek: Στέφανος Βυζάντιος, Stéphanos Byzántios; fl. 6th century AD), was a Byzantine grammarian and the author of an important geographical dictionary entitled Ethnica (Ἐθνικά). Only meagre fragments of the dictionary survive, but the epitome is extant, compiled by one Hermolaus, not otherwise identified.

Life

Nothing is known about the life of Stephanus, except that he was a Greek grammarian[1] who was active in Constantinople, and lived after the time of Arcadius and Honorius, and before that of Justinian II. Later writers provide no information about him, but they do note that the work was later reduced to an epitome by a certain Hermolaus, who dedicated his epitome to Justinian; whether the first or second emperor of that name is meant is disputed, but it seems probable that Stephanus flourished in Byzantium in the earlier part of the sixth century AD, under Justinian I.[2]

The Ethnica

Even as an epitome, the Ethnica is of enormous value for geographical, mythological, and religious information about ancient Greece. Nearly every article in the epitome contains a reference to some ancient writer, as an authority for the name of the place. From the surviving fragments, we see that the original contained considerable quotations from ancient authors, besides many interesting particulars, topographical, historical, mythological, and others. Stephanus cites Artemidorus, Polybius, Aelius Herodianus, Herodotus, Thucydides, Xenophon, Strabo and other writers.[3]

The chief fragments remaining of the original work are preserved by Constantine Porphyrogennetos, De administrando imperio, ch. 23 (the article Ίβηρίαι δύο) and De thematibus, ii. 10 (an account of Sicily); the latter includes a passage from the comic poet Alexis on the Seven Largest Islands. Another respectable fragment, from the article Δύμη to the end of Δ, exists in a manuscript of the Fonds Coislin, the library formed by Pierre Séguier.[4]

The first modern printed edition of the work was that published by the Aldine Press in Venice, 1502. The complete standard edition is still that of Augustus Meineke (1849, reprinted at Graz, 1958), and by convention, references to the text use Meineke's page numbers. A new completely revised edition in German, edited by B. Wyss, C. Zubler, M. Billerbeck, J.F. Gaertner, was published between 2006 and 2017, with a total of 5 volumes.[5]

Editions

- Aldus Manutius (pr.), 1502, Στέφανος. Περὶ πόλεων (Peri poleōn) = Stephanus. De urbibus ("On cities") (Venice). Google Books

- Guilielmus Xylander, 1568, Στέφανος. Περὶ πόλεων = Stephanus. De urbibus (Basel).

- Thomas de Pinedo, 1678, Στέφανος. Περὶ πόλεων = Stephanus. De urbibus (Amsterdam). Contains parallel Latin translation. Google Books

- Claudius Salmasius (Claude Saumaise) and Abraham van Berkel, 1688, Στεφάνου Βυζαντίου Ἐθνικὰ κατ' ἐπιτομήν Περὶ πόλεων = Stephani Byzantini Gentilia per epitomen, antehac De urbibus inscripta (Leiden). Contains parallel Latin translation. Google Books

- Lucas Holstenius, 1692, Notae & castigationes in Stephanum Byzantium De urbibus (Leiden). Google Books

- Thomas de Pinedo, 1725, Stephanus de urbibus (Amsterdam). Google Books

- Karl Wilhelm Dindorf, 1825, Stephanus Byzantinus. Opera, 4 vols, (Leipzig). Incorporating notes by L. Holsteinius, A. Berkelius, and T. de Pinedo. Google Books

- Anton Westermann, 1839, Stephani Byzantii ethnikon quae supersunt (Leipzig). Google Books

- Augustus Meineke, 1849, Stephani Byzantii ethnicorum quae supersunt (Berlin). Google Books

- Margarethe Billerbeck et al. (edd), Stephani Byzantii Ethnica. 5 volumes: 2006–2017. Berlin/New York: Walter de Gruyter, (Corpus Fontium Historiae Byzantinae 43/1)[5][6][7]

References

Further reading

- Smith, W., Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, vol. 3, s.v. "Stephanus" (2) of Byzantium.

- Diller, Aubrey 1938, "The tradition of Stephanus Byzantius", Transactions of the American Philological Association 69: 333–48.

- E.H. Bunbury, 1883, History of Ancient Geography (London), vol. i. 102, 135, 169; ii. 669–71.

- Holstenius, L., 1684 (posth.), Lucae Holstenii Notae et castigationes postumae in Stephani Byzantii Ethnika, quae vulgo Peri poleōn inscribuntur (Leiden).

- Niese, B., 1873, De Stephani Byzantii auctoribus (Kiel)

- Johannes Geffcken, 1886, De Stephano Byzantio (Göttingen)

- Whitehead, D. (ed.), 1994, From political architecture to Stephanus Byzantius : sources for the ancient Greek polis (Stuttgart).

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stephanus_of_Byzantium

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cosmas_Indicopleustes

The Book of Psalms (/sɑː(l)mz/ SAH(L)MZ or /sɔː(l)mz/ SAW(L)MZ;[2] Hebrew: תְּהִלִּים, Tehillim, lit. "praises"), also known as the Psalms, or the Psalter, is the first book of the third section of the Hebrew Bible called Ketuvim ("Writings"), and a book of the Old Testament.[3]

The book is an anthology of Hebrew religious hymns. In the Jewish and Western Christian traditions, there are 150 psalms, and several more in the Eastern Christian churches.[4][5] The book is divided into five sections, each ending with a doxology, or a hymn of praise. There are several types of psalms, including hymns or songs of praise, communal and individual laments, royal psalms and individual thanksgivings. The book also includes psalms of communal thanksgiving, wisdom, pilgrimage and other categories.

While many of the psalms contain attributions to the name of King David and other Biblical figures including Asaph, the sons of Korah, and Solomon, David's authorship is not accepted by most modern Bible scholars, who instead attribute the composition of the psalms to various authors writing between the 9th and 5th centuries BC. The psalms were written from the time of the Israelite conquest of Canaan to the post-exilic period and the book was probably compiled and edited into its present form during the post-exilic period in the 5th century BC.[5]

In English, the title of the book is derived from the Greek word ψαλμοί (psalmoi), meaning "instrumental music" and, by extension, "the words accompanying the music".[6] The Hebrew name of the book, Tehillim (תהילים), means “praises,” as it contains many praises and supplications to God. In the Quran, the Arabic word Zabur is used for in reference to the psalms.[7]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Psalms

The elixir of life, also known as elixir of immortality, is a potion that supposedly grants the drinker eternal life and/or eternal youth. This elixir was also said to cure all diseases. Alchemists in various ages and cultures sought the means of formulating the elixir.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elixir_of_life

| Moon rabbit | |||

|---|---|---|---|

The image of a rabbit and mortar delineated on the Moon's surface | |||

| Chinese name | |||

| Chinese | 月兔 | ||

| Literal meaning | Moon rabbit/hare | ||

| |||

| Alternative Chinese name | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | 玉兔 | ||

| Literal meaning | Jade rabbit/hare | ||

| |||

| Vietnamese name | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Vietnamese alphabet | thỏ ngọc | ||

| Chữ Hán | 玉兔 | ||

| Korean name | |||

| Hangul | 달토끼 | ||

| |||

| Japanese name | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Kanji | 月の兎 | ||

|

The Moon rabbit or Moon hare is a mythical figure in East Asian and indigenous American folklore, based on pareidolic interpretations that identify the dark markings on the near side of the Moon as a rabbit or hare. In East Asia, the rabbit is seen as pounding with a mortar and pestle, but the contents of the mortar differ among Chinese, Japanese, Korean and Vietnamese folklore. In Chinese folklore, the rabbit is often portrayed as a companion of the Moon goddess Chang'e, constantly pounding the elixir of life[1] for her and some show the making of cakes or rice cakes; but in Japanese and Korean versions, the rabbit is pounding the ingredients for mochi or some other type of rice cakes; in the Vietnamese version, the Moon rabbit often appears with Hằng Nga and Chú Cuội, and like the Chinese version, the Vietnamese Moon rabbit also pounding the elixir of immortality in the mortar. In some Chinese versions, the rabbit pounds medicine for the mortals and some include making of mooncakes. Moon folklore from certain Amerindian cultures of North America also has rabbit themes and characters.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moon_rabbit

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moon_rabbit

The lunar maria (/ˈmɑːri.ə/ MAR-ee-ə; SG mare /ˈmɑːreɪ/ MAR-ay)[1] are large, dark, basaltic plains on Earth's Moon, formed by ancient asteroid impacts on the far side on the Moon that triggered volcanic activity on the opposite (near) side.[2] They were dubbed maria (Latin for 'seas'), by early astronomers who mistook them for actual seas.[3] They are less reflective than the "highlands" as a result of their iron-rich composition, and hence appear dark to the naked eye. The maria cover about 16% of the lunar surface, mostly on the side visible from Earth. The few maria on the far side are much smaller, residing mostly in very large craters. The traditional nomenclature for the Moon also includes one oceanus (ocean), as well as features with the names lacus ('lake'), palus ('marsh'), and sinus ('bay'). The last three are smaller than maria, but have the same nature and characteristics.

The names of maria refer to sea features (Mare Humorum, Mare Imbrium, Mare Insularum, Mare Nubium, Mare Spumans, Mare Undarum, Mare Vaporum, Oceanus Procellarum, Mare Frigoris), sea attributes (Mare Australe, Mare Orientale, Mare Cognitum, Mare Marginis), or states of mind (Mare Crisium, Mare Ingenii, Mare Serenitatis, Mare Tranquillitatis). Mare Humboldtianum and Mare Smythii were established before the final nomenclature, that of states of mind, was accepted, and do not follow this pattern.[4] When Mare Moscoviense was discovered by the Luna 3, and the name was proposed by the Soviet Union, it was only accepted by the International Astronomical Union with the justification that Moscow is a state of mind.[5]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lunar_mare

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Aztec_legendary_creatures

Ulmecatl (from Nahuatl, 'where the rubber is born') is one of the six giants sons of Mixcoatl and Tlaltecuhtli[1] that populated the Earth after the Great Flood during the Fifth Sun in Aztec Mythology. The third son who founded Cuetlachoapan, the place where Puebla is now, in addition to Tontonihuacan and Huitzilapan.[2]

Surrounded the Earth by the seas and submerged in them for a long time, the old frog, with a thousand jaws and bloody tongues, and the strange name it takes, Tlaltecuhtli; Iztac-Mixcoatl, the fierce white cloud serpent, who lives in Citlalco, joins her in sweet collusion. And six tlacame with love engender; the six brothers on earth dwell and are the trunk of various races: the first-born, the giant Xelhua, of Itzocan and Epatlan, and Cuauquechollan, the cities he founded. Tenoch, the great Aztec claudillo, in Mexico stops the march of his people, and builds the great Tenochtitlan, a lake city. The strong Cuetlachoapan founds Ulmecatl, and gives its indolent people a seat. On the shores of the gulf, Xicalancatl, the brave Mixtecatl takes refuge. Of Mixtecapan in the sour lands; Otomitl, the xocoyotl, always lives in mountains near Mexico, and there it thrives in rich populations such as Tollan, Xilotepec and Otompan[3]

— Gerónimo de Mendieta (1525–1604)

References

- Guilhem Olivier (2015). Cacería, Sacrificio y Poder en Mesoamérica: Tras las Huellas de Mixcóatl (in Spanish). Fondo de Cultura Económica. ISBN 978-607-16-3216-6.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ulmecatl

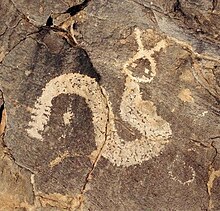

The Horned Serpent appears in the mythologies of many cultures including Native American peoples,[1] European, and Near Eastern mythology. Details vary among cultures, with many of the stories associating the mystical figure with water, rain, lightning, thunder, and rebirth. Horned Serpents were major components of the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex of North American prehistory.[2][3]

In Native American cultures