Charity may refer to:

Giving

- Charitable organization or charity, a non-profit organization whose primary objectives are philanthropy and social well-being of persons

- Charity (practice), the practice of being benevolent, giving and sharing

- Charity (Christian virtue), the Christian religious concept of unlimited love and kindness

- Principle of charity, in philosophy and rhetoric

Places

- Charity, Missouri, a community in the United States

- Charity, Guyana, a small township

- Mount Charity, Antarctica

- Charity Glacier, Livingston Island, Antarctica

- Charity Lake, British Columbia, Canada

- Charity Island (Michigan), United States

- Charity Island (Tasmania), Australia

- Little Charity Island, Lake Huron, Michigan

- Charity Creek, Sydney, Australia

Entertainment

- Charity (play), an 1874 play by W. S. Gilbert

- Charity (novel), third in the Faith, Hope, Charity espionage trilogy of novels by Len Deighton

- "Charity" (Dilbert episode)

- "Charity" (Malcolm in the Middle Episode)

Music

- "Charity", in the List of songs written by Cole Porter

- "Charity" (Courtney Barnett song)

- "Charity" (song), a 1995 single by Skunk Anansie

Paintings

Sports

- Charity (horse) (1830–?), winner of the 1841 Grand National

- Charity Golf Classic, a tournament on the LPGA Tour from 1973 to 1975

- Charity Cup, an annual association football competition in New Zealand

- Charity Cup, an Australian soccer competition held between 1903 and 1961 - see Football West State Cup

- Charity Bowl, a one-time postseason college football bowl game, played in 1937

People

- Charity (name), an English feminine given name (including a list of people with the name)

- Amy Charity (born 1976), American racing cyclist

- Nicole Matthews (born 1987), professional wrestler under the ring name Charity

Other uses

- HMS Charity, several British Royal Navy ships

- MV Charity, a Cypriot cargo ship briefly in service during September 1972

- Charity Hospital (disambiguation)

See also

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charity

| The Transplantation of Human Organs and Tissues Act, 1994 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Parliament of India | |

| |

| Citation | Transplantation of Human Organs and Tissues Act, 1994 |

|---|---|

| Enacted by | Parliament of India |

| Enacted | 8 July 1994 |

| Commenced | 4 February 1995 |

| Introduced by | Ministry of Health and Family Welfare |

| Status: In force | |

The Transplantation of Human Organs and Tissues Act, 1994 is the Law enacted by the Parliament of India and introduced by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare dated 4 February 1994, which deals with the transplantation and donation of 11 human organs and tissues of an alive donor or deceased person.[1] This act is applicable to only those Indian administered states where the act has been adopted or enforced by the state governments. But it applies to all Union territories.[2][3]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Transplantation_of_Human_Organs_and_Tissues_Act,_1994

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Limitation_Act_1980

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Limitation_Act_1623

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Limitation_Act_1963

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Church

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Catholic_Church

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Limitations

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Engineering

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Asset

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Essentialism

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_global_issues

An artificial organ is a human made organ device or tissue that is implanted or integrated into a human — interfacing with living tissue — to replace a natural organ, to duplicate or augment a specific function or functions so the patient may return to a normal life as soon as possible.[1] The replaced function does not have to be related to life support, but it often is. For example, replacement bones and joints, such as those found in hip replacements, could also be considered artificial organs.[2][3]

Implied by definition, is that the device must not be continuously tethered to a stationary power supply or other stationary resources such as filters or chemical processing units. (Periodic rapid recharging of batteries, refilling of chemicals, and/or cleaning/replacing of filters would exclude a device from being called an artificial organ.)[4] Thus, a dialysis machine, while a very successful and critically important life support device that almost completely replaces the duties of a kidney, is not an artificial organ.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Artificial_organ

An embryo is an initial stage of development of a multicellular organism. In organisms that reproduce sexually, embryonic development is the part of the life cycle that begins just after fertilization of the female egg cell by the male sperm cell. The resulting fusion of these two cells produces a single-celled zygote that undergoes many cell divisions that produce cells known as blastomeres. The blastomeres are arranged as a solid ball that when reaching a certain size, called a morula, takes in fluid to create a cavity called a blastocoel. The structure is then termed a blastula, or a blastocyst in mammals.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Embryo

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Builds

Humans (Homo sapiens) are the most common and widespread species of primate. A great ape characterized by their bipedalism and high intelligence, humans' large brain and resulting cognitive skills have allowed them to thrive in a variety of environments and develop complex societies and civilizations. Humans are highly social and tend to live in complex social structures composed of many cooperating and competing groups, from families and kinship networks to political states. As such, social interactions between humans have established a wide variety of values, social norms, languages, and rituals, each of which bolsters human society. The desire to understand and influence phenomena has motivated humanity's development of science, technology, philosophy, mythology, religion, and other conceptual frameworks.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Human

Illicit may refer to:

- Illicit antiquities

- Illicit cigarette trade

- Illicit drug trade

- Illicit financial flows

- Illicit major

- Illicit minor

- Illicit trade

- Illicit work

- Illicit Streetwear clothing company

- Illicit (Dance music group)

- Illicit (film), a 1931 film starring Barbara Stanwyck

- Illicit (album), a 1992 album by Tribal Tech

See also

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Illicit

- Violation of law

- Crime, the practice of breaking the criminal law

- An illegal immigrant, a person that performed illegal immigration

Entertainment

- The Illegal (novel) (2015), by Canadian writer Lawrence Hill

Films

- Illegal (1932 film), British

- Illegal (1955 film), American

- Illegal (2010 film), Belgian

- The Illegal (2019), film starring Suraj Sharma

Music

- Illegal (group), a 1990s rap group

- "Illegal" (song), a track from pop singer Shakira's 2005 release, Oral Fixation Vol. 2

See also

- All pages with titles beginning with Illegal

- Illegal agent, also known as Operational cover

- Illegals Program, Russian spies arrested in the United States in 2010

- The Illegal (disambiguation)

- Illegalism, an anarchist philosophy which openly embraced criminality as a lifestyle

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Illegal

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/fine

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/violation

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/infarction

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/expungement

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/remediation

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/simple

A fine or mulct (the latter synonym typically used in civil law) is a penalty of money that a court of law[1] or other authority decides has to be paid as punishment for a crime or other offense.[2][3][4][5] The amount of a fine can be determined case by case, but it is often announced in advance.[6]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fine_(penalty)

In philosophy and rhetoric, the principle of charity or charitable interpretation requires interpreting a speaker's statements in the most rational way possible and, in the case of any argument, considering its best, strongest possible interpretation.[1] In its narrowest sense, the goal of this methodological principle is to avoid attributing irrationality, logical fallacies, or falsehoods to the others' statements, when a coherent, rational interpretation of the statements is available. According to Simon Blackburn,[2] "it constrains the interpreter to maximize the truth or rationality in the subject's sayings."

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Principle_of_charity

The practice of charity is the voluntary giving of help to those in need, as a humanitarian act, unmotivated by self-interest. There are a number of philosophies about charity, often associated with religion.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charity_(practice)

Charity was a racehorse who won the 1841 Grand National at the second attempt, defeating ten rivals in a time of 13 minutes 25 seconds. William Vevers was the official trainer of Charity. The owner of the horse was William Craven, 2nd Earl of Craven.

Charity had previously taken part in the 1839 Grand National, falling at the wall, which was sited roughly where the water jump is situated on the modern course. The mare was remounted by her rider A Powell only to fall again before reaching the Becher's Brook for the second time.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charity_(horse)

Prohibition of dying is a political social phenomenon and taboo in which a law is passed stating that it is illegal to die, usually specifically in a certain political division or in a specific building.

The earliest case of prohibition of death occurred in the 5th century BC, on the Greek island of Delos; dying on Delos was prohibited on religious grounds.

Today, in most cases, the prohibition of death is a satirical response to the government's failure to approve the expansion of municipal cemeteries. In Spain, one town has prohibited death;[1] in France, there have been several settlements which have had death prohibited;[2][3][4][5] while in Biritiba Mirim, in Brazil, an attempt to prohibit death took place in 2005.[6][7]

There is a falsely rumoured prohibition on recording deaths in royal palaces in the United Kingdom, for rather different reasons[8][9]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prohibition_of_dying

Charity fraud is the act of using deception to get money from people who believe they are making donations to a charity.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charity_fraud

"Caritas" | |

| Gender | Female |

|---|---|

| Origin | |

| Word/name | English via Latin |

| Meaning | Charity |

| Region of origin | English-speaking countries |

Charity is an English feminine given name derived from the English word charity. It was used by the Puritans as a virtue name. An earlier form of the name, Caritas, was an early Christian name in use by Romans.[1]

Charity is also the usual English form of the name of Saint Charity, an early Christian child martyr, who was tortured to death with her sisters Faith and Hope. She is known as Agape in Biblical Greek and as Caritas in Church Latin and her name is translated differently in other languages.

Faith, Hope and Charity, the three theological virtues, are names traditionally given to triplet girls, just as Faith and Hope remain common names for twin girls. One example were the American triplets Faith, Hope and Charity Cardwell, who were born in 1899 in Texas and were recognized in 1994 by the Guinness Book of World Records as the world's longest lived triplets.[2]

Charity has never been as popular a name in the United States as Faith or Hope. It ranked in the top 500 names for American girls between 1880 and 1898 and in the top 1,000 between 1880 and 1927, when it disappeared from the top 1,000 names until it reemerged among the top 1,000 names in 1968 at No. 968. It was most popular between 1973 and 1986, when it ranked among the top 300 names in the United States. It has since declined in popularity and was ranked at No. 852 in 2011.[3]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charity_(name)

| Part of a series on the |

| Divine Mercy |

|---|

|

| Forms |

| People |

| Places |

| Other |

| Part of a series on |

| Love |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In Christian theology, charity (Latin: caritas) is considered one of the seven virtues and is understood by Thomas Aquinas as "the friendship of man for God", which "unites us to God". He holds it as "the most excellent of the virtues".[1] Further, Aquinas holds that "the habit of charity extends not only to the love of God, but also to the love of our neighbor".[2]

The Catechism of the Catholic Church defines "charity" as "the theological virtue by which we love God above all things for His own sake, and our neighbor as ourselves for the love of God".[3]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charity_(Christian_virtue)

Charity schools, sometimes called blue coat schools, or simply the Blue School, were significant in the history of education in England. They were built and maintained in various parishes by the voluntary contributions of the inhabitants to teach poor children to read and write, and for other necessary parts of education. They were usually maintained by religious organisations, which provided clothing and education to students freely or at little charge. In most charity schools, children were put out to trades, services, etc., by the same charitable foundation. Some schools were more ambitious than this and sent a few pupils on to university.

Charity schools began in London, and spread throughout most of the urban areas in England and Wales. By 1710, the statistics for charity schools in and around London were as follows: number of schools, 88; boys taught, 2,181; girls, 1,221; boys put out to apprentices, 967; girls, 407. By the 19th century, English elementary schools were predominantly charity schools.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charity_school

Roman Charity (Latin: Caritas romana; Italian: Carità Romana) is the exemplary story of a woman, Pero, who secretly breastfeeds her father, Cimon, after he is incarcerated and sentenced to death by starvation.[1]

Of Roman origin, it was often represented in art, especially in the Baroque period. Sometimes the title is Cimon and Pero.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roman_Charity

In the Catholic Church, a martyr of charity is someone who dies as a result of a charitable act or of administering Christian charity. While a martyr of the faith, which is what is usually meant by the word "martyr" (both in canon law and in lay terms), dies through being persecuted for being a Catholic or for being a Christian, a martyr of charity dies through practicing charity motivated by Christianity.[1] This is an unofficial form of martyrdom; when Pope Paul VI beatified Maximilian Kolbe he gave him that honorary title (in 1982, when Kolbe was canonized by Pope John Paul II that title was still not given official canonical recognition; instead, John Paul II overruled his advisory commission, which had said Kolbe was a Confessor, not a Martyr, ruling that the systematic hatred of the Nazis as a group toward the rest of humanity was in itself a form of hatred of the faith).

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Martyr_of_charity

Regulation and licensure in engineering is established by various jurisdictions of the world to encourage life, public welfare, safety, well-being, then environment and other interests of the general public[1] and to define the licensure process through which an engineer becomes licensed to practice engineering and to provide professional services and products to the public as a Professional Engineer.

As with many other professions and activities, engineering is a restricted activity.[2] Relatedly, jurisdictions that license according to particular engineering discipline define the boundaries of each discipline carefully so that practitioners understand what they are competent to do.

A licensed engineer takes legal responsibility for engineering work, product or projects (typically via a seal or stamp on the relevant design documentation) as far as the local engineering legislation is concerned. Regulations require that only a licensed engineer can sign, seal or stamp technical documentation such as reports, plans, engineering drawings and calculations for study estimate or valuation or carry out design analysis, repair, servicing, maintenance or supervision of engineering work, process or project. In cases where public safety, property or welfare is concerned, licensed engineers are trusted by the government and the public to perform the task in a competent manner.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Regulation_and_licensure_in_engineering

Regulation is the management of complex systems according to a set of rules and trends. In systems theory, these types of rules exist in various fields of biology and society, but the term has slightly different meanings according to context. For example:

- in biology, gene regulation and metabolic regulation allow living organisms to adapt to their environment and maintain homeostasis;

- in government, typically regulation means stipulations of the delegated legislation which is drafted by subject-matter experts[citation needed] to enforce primary legislation;

- in business, industry self-regulation occurs through self-regulatory organizations and trade associations which allow industries to set and enforce rules with less government involvement; and,

- in psychology, self-regulation theory is the study of how individuals regulate their thoughts and behaviors to reach goals.

Social

Regulation in the social, political, psychological, and economic domains can take many forms: legal restrictions promulgated by a government authority, contractual obligations (for example, contracts between insurers and their insureds[1]), self-regulation in psychology, social regulation (e.g. norms), co-regulation, third-party regulation, certification, accreditation or market regulation.[2]

State-mandated regulation is government intervention in the private market in an attempt to implement policy and produce outcomes which might not otherwise occur,[3] ranging from consumer protection to faster growth or technological advancement.

The regulations may prescribe or proscribe conduct ("command-and-control" regulation), calibrate incentives ("incentive" regulation), or change preferences ("preferences shaping" regulation). Common examples of regulation include limits on environmental pollution , laws against child labor or other employment regulations, minimum wages laws, regulations requiring truthful labelling of the ingredients in food and drugs, and food and drug safety regulations establishing minimum standards of testing and quality for what can be sold, and zoning and development approvals regulation. Much less common are controls on market entry, or price regulation.

One critical question in regulation is whether the regulator or government has sufficient information to make ex-ante regulation more efficient than ex-post liability for harm and whether industry self-regulation might be preferable.[4][5][6][7] The economics of imposing or removing regulations relating to markets is analysed in empirical legal studies, law and economics, political science, environmental science, health economics, and regulatory economics.

Power to regulate should include the power to enforce regulatory decisions. Monitoring is an important tool used by national regulatory authorities in carrying out the regulated activities.[8]

In some countries (in particular the Scandinavian countries) industrial relations are to a very high degree regulated by the labour market parties themselves (self-regulation) in contrast to state regulation of minimum wages etc.[9]

Reasons

This article contains weasel words: vague phrasing that often accompanies biased or unverifiable information. (March 2018) |

Regulations may create costs as well as benefits and may produce unintended reactivity effects, such as defensive practice.[10] Efficient regulations can be defined as those where total benefits exceed total costs.

Regulations can be advocated for a variety of reasons, including[citation needed]

- Market failures – regulation due to inefficiency. Intervention due to what economists call market failure.

- To constrain sellers' options in markets characterized by monopoly

- As a means to implement collective action, in order to provide public goods

- To assure adequate information in the market

- To mitigate undesirable externalities

- Collective desires – regulation about collective desires or considered judgments on the part of a significant segment of society[vague]

- Diverse experiences – regulation with a view of eliminating or enhancing opportunities for the formation of diverse preferences and beliefs[vague]

- Social subordination – regulation aimed to increase or reduce social subordination of various social groups[citation needed]

- Endogenous preferences – regulation intended to affect the development of certain preferences on an aggregate level[vague]

- Professional conduct – the regulation of members of professional bodies, either acting under statutory or contractual powers.[11]

- Interest group transfers – regulation that results from efforts by self-interest groups to redistribute wealth in their favor, which may be disguised as one or more of the justifications above.

The study of formal (legal or official) and informal (extra-legal or unofficial) regulation constitutes one of the central concerns of the sociology of law.

History

Regulation of businesses existed in the ancient early Egyptian, Indian, Greek, and Roman civilizations. Standardized weights and measures existed to an extent in the ancient world, and gold may have operated to some degree as an international currency. In China, a national currency system existed and paper currency was invented. Sophisticated law existed in Ancient Rome. In the European Early Middle Ages, law and standardization declined with the Roman Empire, but regulation existed in the form of norms, customs, and privileges; this regulation was aided by the unified Christian identity and a sense of honor regarding contracts.[12]: 5

Modern industrial regulation can be traced to the Railway Regulation Act 1844 in the United Kingdom, and succeeding Acts. Beginning in the late 19th and 20th centuries, much of regulation in the United States was administered and enforced by regulatory agencies which produced their own administrative law and procedures under the authority of statutes. Legislators created these agencies to allow experts in the industry to focus their attention on the issue. At the federal level, one of the earliest institutions was the Interstate Commerce Commission which had its roots in earlier state-based regulatory commissions and agencies. Later agencies include the Federal Trade Commission, Securities and Exchange Commission, Civil Aeronautics Board, and various other institutions. These institutions vary from industry to industry and at the federal and state level. Individual agencies do not necessarily have clear life-cycles or patterns of behavior, and they are influenced heavily by their leadership and staff as well as the organic law creating the agency. In the 1930s, lawmakers believed that unregulated business often led to injustice and inefficiency; in the 1960s and 1970s, concern shifted to regulatory capture, which led to extremely detailed laws creating the United States Environmental Protection Agency and Occupational Safety and Health Administration.

See also

- Consumer protection – Protect consumers against unfair practices

- Rulemaking – Process by which executive branch agencies create regulations

- Regulatory state

- Deregulation – Remove or reduce state regulations

- Environmental law – Branch of law concerning the natural environment

- Occupational safety and health – Field concerned with the safety, health and welfare of people at work

- Public administration – Implementation of government policy

- Regulation of science

- Regulatory capture – Form of political corruption

- Regulatory economics – Economics of regulation

- Tragedy of the commons – Self-interests causing depletion of a shared resource

- Public choice – Economic theory applied to political science

- Precautionary principle – Risk management strategy

References

- John Braithwaite, Péter Drahos. (2000). Global Business Regulation. Cambridge University Press.

External links

- Centre on Regulation in Europe (CERRE)

- New Perspectives on Regulation (2009) and Government and Markets: Toward a New Theory of Regulation (2009)

- US/Canadian Regulatory Cooperation: Archived 2011-04-30 at the Wayback Machine Schmitz on Lessons from the European Union, Canadian Privy Council Office Commissioned Study

- A Comparative Bibliography: Regulatory Competition on Corporate Law

Wikibooks

- Legal and Regulatory Issues in the Information Economy

- Lawrence A. Cunningham, A Prescription to Retire the Rhetoric of 'Principles-Based Systems' in Corporate Law, Securities Regulation and Accounting (2007)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Regulation

Line regulation is the ability of a power supply to maintain a constant output voltage despite changes to the input voltage, with the output current drawn from the power supply remaining constant.

where ΔVi is the change in input voltage while ΔVo is the corresponding change in output voltage.

It is desirable for a power supply to maintain a stable output regardless of changes in the input voltage. The line regulation is important when the input voltage source is unstable or unregulated and this would result in significant variations in the output voltage. The line regulation for an unregulated power supply is usually very high for a majority of operations, but this can be improved by using a voltage regulator. A low line regulation is always preferred. In practice, a well regulated power supply should have a line regulation of at most 0.1%.[1]

In the regulator device datasheets the line regulation is expressed as percent change in output with respect to change in input per volt of the output. Mathematically it is expressed as:

The unit here is %/V. For example, In the ABLIC Inc. S1206-series regulator device the typical line regulation is expressed as 0.05%/V which means that the change in the output with respect to change in the input of the regulator device is 0.05%, when the output of the device is set at 1V. Moreover, the line regulation of the device expressed in the datasheet is temperature dependent. Usually the datasheets mention line regulation at 25 °C.[2]

See also

Notes

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Line_regulation

Trade regulation is a field of law, often bracketed with antitrust (as in the phrase “antitrust and trade regulation law”),[1] including government regulation of unfair methods of competition and unfair or deceptive business acts or practices. Antitrust law is often considered a subset of trade regulation law. Franchise and distribution law, consumer protection law, and advertising law are sometimes considered parts of trade regulation law.[2]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trade_regulation

Night aviation regulations in the United States are administered and enforced by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). Unlike many countries,[1][2][3][4] the United States places no special restrictions on VFR flying at night.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Night_aviation_regulations_in_the_United_States

In general, compliance means conforming to a rule, such as a specification, policy, standard or law. Compliance has traditionally been explained by reference to the deterrence theory, according to which punishing a behavior will decrease the violations both by the wrongdoer (specific deterrence) and by others (general deterrence). This view has been supported by economic theory, which has framed punishment in terms of costs and has explained compliance in terms of a cost-benefit equilibrium (Becker 1968). However, psychological research on motivation provides an alternative view: granting rewards (Deci, Koestner and Ryan, 1999) or imposing fines (Gneezy Rustichini 2000) for a certain behavior is a form of extrinsic motivation that weakens intrinsic motivation and ultimately undermines compliance.

Regulatory compliance describes the goal that organizations aspire to achieve in their efforts to ensure that they are aware of and take steps to comply with relevant laws, policies, and regulations.[1] Due to the increasing number of regulations and need for operational transparency, organizations are increasingly adopting the use of consolidated and harmonized sets of compliance controls.[2] This approach is used to ensure that all necessary governance requirements can be met without the unnecessary duplication of effort and activity from resources.

Regulations and accrediting organizations vary among fields, with examples such as PCI-DSS and GLBA in the financial industry, FISMA for U.S. federal agencies, HACCP for the food and beverage industry, and the Joint Commission and HIPAA in healthcare. In some cases other compliance frameworks (such as COBIT) or even standards (NIST) inform on how to comply with regulations.

Some organizations keep compliance data—all data belonging or pertaining to the enterprise or included in the law, which can be used for the purpose of implementing or validating compliance—in a separate store for meeting reporting requirements. Compliance software is increasingly being implemented to help companies manage their compliance data more efficiently. This store may include calculations, data transfers, and audit trails.[3][4]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Regulatory_compliance

The Regulator Movement, also known as the Regulator Insurrection, War of Regulation, and War of the Regulation, was an uprising in Provincial North Carolina from 1766 to 1771 in which citizens took up arms against colonial officials, whom they viewed as corrupt. Though the rebellion did not change the power structure, some historians consider it a catalyst to the American Revolutionary War. Others like John Spencer Bassett take the view that the Regulators did not wish to change the form or principle of their government, but simply wanted to make the colony's political process more equal. They wanted better economic conditions for everyone, instead of a system that heavily benefited the colonial officials and their network of plantation owners mainly near the coast. Bassett interprets the events of the late 1760s in Orange and surrounding counties as "...a peasants' rising, a popular upheaval."[1]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Regulator_Movement

A courthouse clique, courthouse machine, courthouse ring, courthouse gang, or courthouse crowd is a type of political machine in the United States principally composed of county-level public officials. Historically, they were especially predominant in the South until the mid-20th century.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Courthouse_clique

The regulation of chemicals is the legislative intent of a variety of national laws or international initiatives such as agreements, strategies or conventions. These international initiatives define the policy of further regulations to be implemented locally as well as exposure or emission limits. Often, regulatory agencies oversee the enforcement of these laws.

Chemicals are regulated for:

- environmental protection (chemical waste, and chemical pollution of water, air, subterrestrial and terrestrial environments such as of pesticides)

- human health (such as in cosmetics and foods) and drugs (recreational and pharmaceuticals)

- chemical weapons prohibition (such as for the Chemical Weapons Convention)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Regulation_of_chemicals

Bank regulation in the United States is highly fragmented compared with other G10 countries, where most countries have only one bank regulator. In the U.S., banking is regulated at both the federal and state level. Depending on the type of charter a banking organization has and on its organizational structure, it may be subject to numerous federal and state banking regulations. Apart from the bank regulatory agencies the U.S. maintains separate securities, commodities, and insurance regulatory agencies at the federal and state level, unlike Japan and the United Kingdom (where regulatory authority over the banking, securities and insurance industries is combined into one single financial-service agency).[1] Bank examiners are generally employed to supervise banks and to ensure compliance with regulations.

U.S. banking regulation addresses privacy, disclosure, fraud prevention, anti-money laundering, anti-terrorism, anti-usury lending, and the promotion of lending to lower-income populations. Some individual cities also enact their own financial regulation laws (for example, defining what constitutes usurious lending).

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bank_regulation_in_the_United_States

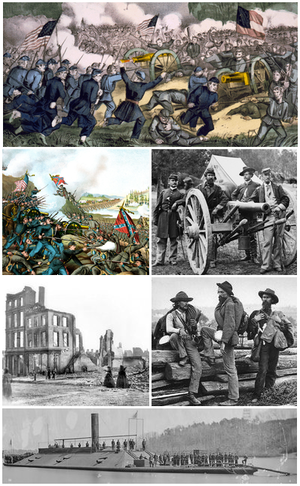

| American Civil War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Clockwise from top: | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

and others... |

and others... | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

2,200,000[c] 698,000 (peak)[3][4] |

750,000–1,000,000[c][5] 360,000 (peak)[3][6] | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| Total: 828,000+ casualties | Total: 864,000+ casualties | ||||||||

| This article is part of a series on the |

| History of the United States |

|---|

|

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union[f] ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states that had seceded. The central cause of the war was the dispute over whether slavery would be permitted to expand into the western territories, leading to more slave states, or be prevented from doing so, which was widely believed would place slavery on a course of ultimate extinction.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/American_Civil_War

The Mines and Minerals (Regulation and Development) Act (1957) is an Act of the Parliament of India enacted to regulate the mining sector in India. It was amended in 2015 and 2016. This act forms the basic framework of mining regulation in India.[1]

This act is applicable to all mineral except minor minerals and atomic minerals. It details the process and conditions for acquiring a mining or prospecting licence in India. Mining minor minerals comes under the purview of state governments.[1] River sand is considered a minor mineral.[2] For mining and prospecting in forest land, prior permission is needed from the Ministry of Environment and Forests.[3]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mines_and_Minerals_(Development_and_Regulation)_Act

The president of the United States (POTUS)[A] is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States Armed Forces.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/President_of_the_United_States

Regulatory affairs (RA), also called government affairs, is a profession within regulated industries, such as pharmaceuticals, medical devices, cosmetics, agrochemicals (plant protection products and fertilizers), energy, banking, telecom etc. Regulatory affairs also has a very specific meaning within the healthcare industries (pharmaceuticals, medical devices, biologics and functional foods).

Regulatory affairs professionals (aka regulatory professionals) usually have responsibility for the following general areas:

- Ensuring that their companies comply with all of the regulations and laws pertaining to their business.

- Working with federal, state, and local regulatory agencies and personnel on specific issues affecting their business, i.e., working with such agencies as the Food and Drug Administration or European Medicines Agency (pharmaceuticals and medical devices); The Department of Energy; or the Securities and Exchange Commission (banking).

- Advising their companies on the regulatory aspects and climate that would affect proposed activities. i.e. describing the "regulatory climate" around issues such as the promotion of prescription drugs and Sarbanes-Oxley compliance.[1]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Regulatory_affairs

| |

| Agency overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | June 30, 1906[1] |

| Preceding agencies |

|

| Jurisdiction | Federal government of the United States |

| Headquarters | White Oak Campus 10903 New Hampshire Avenue Silver Spring, Maryland 20993 39°02′07″N 76°58′59″W |

| Employees | 18,000 (2022)[2] |

| Annual budget | US$6.5 billion (2022)[2] |

| Agency executives |

|

| Parent agency | Department of Health and Human Services |

| Child agencies |

|

| Website | fda.gov |

The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA or US FDA) is a federal agency of the Department of Health and Human Services. The FDA is responsible for protecting and promoting public health through the control and supervision of food safety, tobacco products, caffeine products, dietary supplements, prescription and over-the-counter pharmaceutical drugs (medications), vaccines, biopharmaceuticals, blood transfusions, medical devices, electromagnetic radiation emitting devices (ERED), cosmetics, animal foods & feed[3] and veterinary products.

The FDA's primary focus is enforcement of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FD&C), but the agency also enforces other laws, notably Section 361 of the Public Health Service Act, as well as associated regulations. Much of this regulatory-enforcement work is not directly related to food or drugs, but involves such things as regulating lasers, cellular phones, and condoms, as well as control of disease in contexts varying from household pets to human sperm donated for use in assisted reproduction.

The FDA is led by the Commissioner of Food and Drugs, appointed by the President with the advice and consent of the Senate. The Commissioner reports to the Secretary of Health and Human Services. Robert Califf is the current commissioner, as of 17 February 2022.[4]

The FDA has its headquarters in unincorporated White Oak, Maryland.[5] The agency also has 223 field offices and 13 laboratories located throughout the 50 states, the United States Virgin Islands, and Puerto Rico.[6] In 2008, the FDA began to post employees to foreign countries, including China, India, Costa Rica, Chile, Belgium, and the United Kingdom.[7]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Food_and_Drug_Administration#Medications

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Economy_of_the_United_States

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Money_transmitter#Regulation

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Electrical_safety_standards

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_Congress

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Government_by_algorithm

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_systemically_important_banks

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Religion_in_the_United_States

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/T-Mobile_US

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Customer_Identification_Program

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/E-commerce#Governmental_regulation

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Medical_device#Regulation_and_oversight

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_Armed_Forces

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Regulation_of_tobacco_by_the_U.S._Food_and_Drug_Administration

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pollution

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Pentagon

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Constitution_of_the_United_States

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Demand_deposit

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Advertising#Regulation

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black_Codes_(United_States)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Video_games_in_the_United_States

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Red-eared_slider?wprov=srpw1_163#Infection_risks_and_United_States_federal_regulations_on_commercial_distribution

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_regions_of_the_United_States

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/AR-15_style_rifle

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Code_of_Practices_for_Television_Broadcasters

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Banned_gymnastics_skills

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Unlicensed_National_Information_Infrastructure

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/American_English

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/International_vehicle_registration_code

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wire_transfer

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Natural_monopoly

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_in_World_War_I

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Midwestern_United_States

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Languages_of_the_United_States

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trust_law

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/German_Steel_Trust

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/E_number

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/107%25_rule

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Soldier%27s_Medal_recipients

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/International_rankings_of_the_United_States

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Federal_government_of_the_United_States

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prescription_drug#Regulation

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_Department_of_Defense

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_passport

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Founding_Fathers_of_the_United_States

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Beauty_pageant

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Slaughterhouse#Regulation_and_expansion

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Metrication_in_the_United_States

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bank_account

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_unusual_biological_names

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Regulation_and_monitoring_of_pollution

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Telephone_number

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abortion_in_the_United_States

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pesticide#Regulation

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Transpiration#Regulation

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fracking_in_the_United_States#Regulation

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Good_laboratory_practice

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Negative_feedback#Error-controlled_regulation

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_Department_of_Energy

Law enforcement is the activity of some members of government who act in an organized manner to enforce the law by discovering, deterring, rehabilitating, or punishing people who violate the rules and norms governing that society.[1] The term encompasses police, courts, and corrections. These three components may operate independently of each other or collectively, through the use of record sharing and mutual cooperation.

The concept of law enforcement dates back to ancient times, and forms of law enforcement and police have existed in various forms across many human societies. Modern state legal codes use the term peace officer, or law enforcement officer, to include every person vested by the legislating state with police power or authority; traditionally, anyone sworn or badged, who can arrest any person for a violation of criminal law, is included under the umbrella term of law enforcement.

Although law enforcement may be most concerned with the prevention and punishment of crimes, organizations exist to discourage a wide variety of non-criminal violations of rules and norms, effected through the imposition of less severe consequences such as probation.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Law_enforcement

A pardon is a government decision to allow a person to be relieved of some or all of the legal consequences resulting from a criminal conviction. A pardon may be granted before or after conviction for the crime, depending on the laws of the jurisdiction.[1][2]

Pardons can be granted in many countries when individuals are deemed to have demonstrated that they have "paid their debt to society", or are otherwise considered to be deserving of them. In some jurisdictions of some nations, accepting a pardon may implicitly constitute an admission of guilt; the offer is refused in some cases. Cases of wrongful conviction are in recent times more often dealt with by appeal rather than by pardon; however, a pardon is sometimes offered when innocence is undisputed in order to avoid the costs that are associated with a retrial. Clemency plays a critical role when capital punishment exists in a jurisdiction.

Pardons are sometimes seen as a mechanism for combating corruption, allowing a particular authority to circumvent a flawed judicial process to free someone who is seen as wrongly convicted. Pardons can also be a source of controversy. In extreme cases, some pardons may be seen as acts of corruption by officials in the form of granting effective immunity as political favors.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pardon

In European Christianity, the divine right of kings, divine right, or God's mandation is a political and religious doctrine of political legitimacy of a monarchy. It stems from a specific metaphysical framework in which a monarch is, before birth, pre-ordained to inherit the crown, chosen by God and in the image of God. According to this theory of political legitimacy, the subjects of the crown have actively (and not merely passively) turned over the metaphysical selection of the king's soul – which will inhabit the body and rule them – to God. In this way, the "divine right" originates as a metaphysical act of humility and/or submission towards God. Divine right has been a key element of the legitimisation of many absolute monarchies.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Divine_right_of_kings

A manual override (MO) or manual analog override (MAO) is a mechanism where control is taken from an automated system and given to the user. For example, a manual override in photography refers to the ability for the human photographer to turn off the automatic aperture sizing, automatic focusing, or any other automated system on the camera.[1]

Some manual overrides can be used to veto an automated system's judgment when the system is in error. An example of this is a printer's ink level detection: in one case, a researcher found that when he overrode the system, up to 38% more pages could be printed at good quality by the printer than the automated system would have allowed.[2]

Automated systems are becoming increasingly common and integrated into everyday objects such as automobiles and domestic appliances. This development of ubiquitous computing raises general issues of policy and law about the need for manual overrides for matters of great importance such as life-threatening situations and major economic decisions. The loyalty of such autonomous devices then becomes an issue. If they follow rules installed by the manufacturer or required by law and refuse to cede control in some situations then the owners of the devices may feel disempowered, alienated and lacking true ownership.[3]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Manual_override

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emergency_brake_(train)#United_States

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dead_man%27s_switch

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Function_(mathematics)#Restrictions_and_extensions

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/FADEC

Body donation, anatomical donation, or body bequest is the donation of a whole body after death for research and education. There is usually no cost to donate a body to science; donation programs will often provide a stipend and/or cover the cost of cremation or burial once a donated cadaver has served its purpose and is returned to the family for interment.

For years, only medical schools accepted bodies for donation, but now[when?] private programs also accept donors. Depending on the program's need for body donation, some programs accept donors with different specifications.[clarification needed]

Any person wishing to donate their body may do so through a willed body program. The donor may be required, but not always, to make prior arrangements with the local medical school, university, or body donation program before death. Individuals may request a consent form, and will be supplied information about policies and procedures that will take place after the potential donor is deceased.

The practice is still relatively rare, and in attempts to increase these donations, many countries have instituted programs and regulations surrounding the donation of cadavers or body parts. For example, in some states within the United States and for academic-based programs, a person must make the decision to donate their remains themselves prior to death; the decision cannot be made by a power of attorney. If a person decides not to donate their whole body, or they are unable to, there are other forms of donation via which one can contribute their body to science after death, such as organ donation and tissue donation.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Body_donation

Reasons for donation and ethical issues

Living related donors donate to family members or friends in whom they have an emotional investment. The risk of surgery is offset by the psychological benefit of not losing someone related to them, or not seeing them suffer the ill effects of waiting on a list.

Paired exchange

A "paired-exchange" is a technique of matching willing living donors to compatible recipients using serotyping. For example, a spouse may be willing to donate a kidney to their partner but cannot since there is not a biological match. The willing spouse's kidney is donated to a matching recipient who also has an incompatible but willing spouse. The second donor must match the first recipient to complete the pair exchange. Typically the surgeries are scheduled simultaneously in case one of the donors decides to back out and the couples are kept anonymous from each other until after the transplant. Paired-donor exchange, led by work in the New England Program for Kidney Exchange as well as at Johns Hopkins University and the Ohio organ procurement organizations, may more efficiently allocate organs and lead to more transplants.

Paired exchange programs were popularized in the New England Journal of Medicine article "Ethics of a paired-kidney-exchange program" in 1997 by L.F. Ross.[39] It was also proposed by Felix T. Rapport[40] in 1986 as part of his initial proposals for live-donor transplants "The case for a living emotionally related international kidney donor exchange registry" in Transplant Proceedings.[41] A paired exchange is the simplest case of a much larger exchange registry program where willing donors are matched with any number of compatible recipients.[42] Transplant exchange programs have been suggested as early as 1970: "A cooperative kidney typing and exchange program."[43]

The first pair exchange transplant in the US was in 2001 at Johns Hopkins Hospital.[44] The first complex multihospital kidney exchange involving 12 people was performed in February 2009 by The Johns Hopkins Hospital, Barnes-Jewish Hospital in St. Louis and Integris Baptist Medical Center in Oklahoma City.[45] Another 12-person multihospital kidney exchange was performed four weeks later by Saint Barnabas Medical Center in Livingston, New Jersey, Newark Beth Israel Medical Center and New York-Presbyterian Hospital.[46] Surgical teams led by Johns Hopkins continue to pioneer this field with more complex chains of exchange, such as an eight-way multihospital kidney exchange.[47] In December 2009, a 13 organ 13 recipient matched kidney exchange took place, coordinated through Georgetown University Hospital and Washington Hospital Center, Washington, DC.[48]

Good Samaritan

Good Samaritan or "altruistic" donation is giving a donation to someone that has no prior affiliation with the donor. The idea of altruistic donation is to give with no interest of personal gain, it is out of pure selflessness. On the other hand, the current allocation system does not assess a donor's motive, so altruistic donation is not a requirement.[49] Some people choose to do this out of a personal need to donate. Some donate to the next person on the list; others use some method of choosing a recipient based on criteria important to them. Websites are being developed that facilitate such donation. Over half of the members of the Jesus Christians, an Australian religious group, have donated kidneys in such a fashion.[50]

Financial compensation

Monetary compensation for organ donors, in the form of reimbursement for out-of-pocket expenses, has been legalised in Australia,[51] and strictly only in the case of kidney transplant in the case of Singapore (minimal reimbursement is offered in the case of other forms of organ harvesting by Singapore). Kidney disease organizations in both countries have expressed their support.[52][53]

In compensated donation, donors get money or other compensation in exchange for their organs. This practice is common in some parts of the world, whether legal or not, and is one of the many factors driving medical tourism.[54]

In the illegal black market the donors may not get sufficient after-operation care,[55] the price of a kidney may be above $160,000,[56] middlemen take most of the money, the operation is more dangerous to both the donor and receiver, and the receiver often gets hepatitis or HIV.[57] In legal markets of Iran[58] the price of a kidney is $2,000 to $4,000.[57][59][60]

An article by Gary Becker and Julio Elias on "Introducing Incentives in the market for Live and Cadaveric Organ Donations"[61] said that a free market could help solve the problem of a scarcity in organ transplants. Their economic modeling was able to estimate the price tag for human kidneys ($15,000) and human livers ($32,000).

In the United States, The National Organ Transplant Act of 1984 made organ sales illegal. In the United Kingdom, the Human Organ Transplants Act 1989 first made organ sales illegal, and has been superseded by the Human Tissue Act 2004. In 2007, two major European conferences recommended against the sale of organs.[62] Recent development of websites and personal advertisements for organs among listed candidates has raised the stakes when it comes to the selling of organs, and have also sparked significant ethical debates over directed donation, "good-Samaritan" donation, and the current US organ allocation policy. Bioethicist Jacob M. Appel has argued that organ solicitation on billboards and the internet may actually increase the overall supply of organs.[63]

In an experimental survey, Elias, Lacetera and Macis (2019) find that preferences for compensation for kidney donors have strong moral foundations; participants in the experiment especially reject direct payments by patients, which they find would violate principles of fairness.[64]

Many countries have different approaches to organ donation such as the opt-out approach and many advertisements of organ donors, encouraging people to donate. Although these laws have been implemented in a certain country they are not forced upon everyone as it is an individual decision.

Two books, Kidney for Sale By Owner by Mark Cherry (Georgetown University Press, 2005) and Stakes and Kidneys: Why Markets in Human Body Parts are Morally Imperative by James Stacey Taylor: (Ashgate Press, 2005), advocate using markets to increase the supply of organs available for transplantation. In a 2004 journal article economist Alex Tabarrok argues that allowing organ sales, and elimination of organ donor lists will increase supply, lower costs and diminish social anxiety towards organ markets.[65]

Iran has had a legal market for kidneys since 1988.[66] The donor is paid approximately US$1200 by the government and also usually receives additional funds from either the recipient or local charities.[59][67] The Economist[68] and the Ayn Rand Institute[69] approve and advocate a legal market elsewhere. They argued that if 0.06% of Americans between 19 and 65 were to sell one kidney, the national waiting list would disappear (which, the Economist wrote, happened in Iran). The Economist argued that donating kidneys is no more risky than surrogate motherhood, which can be done legally for pay in most countries.

In Pakistan, 40 percent to 50 percent of the residents of some villages have only one kidney because they have sold the other for a transplant into a wealthy person, probably from another country, said Dr. Farhat Moazam of Pakistan, at a World Health Organization conference. Pakistani donors are offered $2,500 for a kidney but receive only about half of that because middlemen take so much.[70] In Chennai, southern India, poor fishermen and their families sold kidneys after their livelihoods were destroyed by the Indian Ocean tsunami on 26 December 2004. About 100 people, mostly women, sold their kidneys for 40,000–60,000 rupees ($900–1,350).[71] Thilakavathy Agatheesh, 30, who sold a kidney in May 2005 for 40,000 rupees said, "I used to earn some money selling fish but now the post-surgery stomach cramps prevent me from going to work." Most kidney sellers say that selling their kidney was a mistake.[72]

In Cyprus in 2010, police closed a fertility clinic under charges of trafficking in human eggs. The Petra Clinic, as it was known locally, brought in women from Ukraine and Russia for egg harvesting and sold the genetic material to foreign fertility tourists.[73] This sort of reproductive trafficking violates laws in the European Union. In 2010, Scott Carney reported for the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting and the magazine Fast Company explored illicit fertility networks in Spain, the United States and Israel.[74][75]

Forced donation

There have been concerns that certain authorities are harvesting organs from people deemed undesirable, such as prison populations. The World Medical Association stated that prisoners and other individuals in custody are not in a position to give consent freely, and therefore their organs must not be used for transplantation.[76]

According to former Chinese Deputy Minister of Health, Huang Jiefu, the practice of transplanting organs from executed prisoners is still occurring as of February 2017.[77][78] World Journal reported Huang had admitted approximately 95% of all organs used for transplantation are from executed prisoners.[78] The lack of a public organ donation program in China is used as a justification for this practice. In July 2006, the Kilgour-Matas report[79] stated, "the source of 41,500 transplants for the six-year period 2000 to 2005 is unexplained" and "we believe that there has been and continues today to be large scale organ seizures from unwilling Falun Gong practitioners".[79] Investigative journalist Ethan Gutmann estimates 65,000 Falun Gong practitioners were killed for their organs from 2000 to 2008.[80][81] However 2016 reports updated the death toll of the 15-year period since the persecution of Falun Gong began putting the death toll at 150,000[82] to 1.5 million.[83] In December 2006, after not getting assurances from the Chinese government about allegations relating to Chinese prisoners, the two major organ transplant hospitals in Queensland, Australia stopped transplantation training for Chinese surgeons and banned joint research programs into organ transplantation with China.[84]

In May 2008, two United Nations Special Rapporteurs reiterated their requests for "the Chinese government to fully explain the allegation of taking vital organs from Falun Gong practitioners and the source of organs for the sudden increase in organ transplants that has been going on in China since the year 2000".[85] People in other parts of the world are responding to this availability of organs, and a number of individuals (including US and Japanese citizens) have elected to travel to China or India as medical tourists to receive organ transplants which may have been sourced in what might be considered elsewhere to be unethical manner.[86][87][88][89][90]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Organ_transplantation#Reasons_for_donation_and_ethical_issues

Philanthropy is a form of altruism that consists of "private initiatives, for the public good, focusing on quality of life". Philanthropy contrasts with business initiatives, which are private initiatives for private good, focusing on material gain; and with government endeavors, which are public initiatives for public good, notably focusing on provision of public services.[1] A person who practices philanthropy is a philanthropist.

Etymology

The word philanthropy comes from Ancient Greek φιλανθρωπία (philanthrōpía) 'love of humanity', from phil- 'love, fond of' and anthrōpos 'humankind, mankind'.[2] In the second century AD, Plutarch used the Greek concept of philanthrôpía to describe superior human beings. During the Middle Ages, philanthrôpía was superseded in Europe by the Christian virtue of charity (Latin: caritas) in the sense of selfless love, valued for salvation and escape from purgatory.[3] Thomas Aquinas held that "the habit of charity extends not only to the love of God, but also to the love of our neighbor".[4]

Philanthropy was modernized by Sir Francis Bacon in the 1600s, who is credited in great part with preventing the word from being owned by horticulture.[clarification needed] Bacon considered philanthrôpía to be synonymous with "goodness", correlated with the Aristotelian conception of virtue, as consciously instilled habits of good behaviour. Samuel Johnson simply defined philanthropy as "love of mankind; good nature".[5] This definition still survives today and is often cited more gender-neutrally as the "love of humanity."[6][better source needed]

Europe

Great Britain

In London, prior to the 18th century, parochial and civic charities were typically established by bequests and operated by local church parishes (such as St Dionis Backchurch) or guilds (such as the Carpenters' Company). During the 18th century, however, "a more activist and explicitly Protestant tradition of direct charitable engagement during life" took hold, exemplified by the creation of the Society for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge and Societies for the Reformation of Manners.[7]

In 1739, Thomas Coram, appalled by the number of abandoned children living on the streets of London, received a royal charter to establish the Foundling Hospital to look after these unwanted orphans in Lamb's Conduit Fields, Bloomsbury.[8] This was "the first children's charity in the country, and one that 'set the pattern for incorporated associational charities' in general."[8] The hospital "marked the first great milestone in the creation of these new-style charities."[7]

Jonas Hanway, another notable philanthropist of the era, established The Marine Society in 1756 as the first seafarer's charity, in a bid to aid the recruitment of men to the navy.[9] By 1763, the society had recruited over 10,000 men and it was incorporated in 1772. Hanway was also instrumental in establishing the Magdalen Hospital to rehabilitate prostitutes. These organizations were funded by subscription and run as voluntary associations. They raised public awareness of their activities through the emerging popular press and were generally held in high social regard—some charities received state recognition in the form of the Royal Charter.

19th century

Philanthropists, such as anti-slavery campaigner William Wilberforce, began to adopt active campaigning roles, where they would champion a cause and lobby the government for legislative change. This included organized campaigns against the ill treatment of animals and children and the campaign that succeeded in ending the slave trade throughout the Empire starting in 1807.[10] Although there were no slaves allowed in Britain itself, many rich men owned sugar plantations in the West Indies, and resisted the movement to buy them out until it finally succeeded in 1833.[11]

Financial donations to organized charities became fashionable among the middle-class in the 19th century. By 1869 there were over 200 London charities with an annual income, all together, of about £2 million. By 1885, rapid growth had produced over 1000 London charities, with an income of about £4.5 million. They included a wide range of religious and secular goals, with the American import, YMCA, as one of the largest, and many small ones such as the Metropolitan Drinking Fountain Association. In addition to making annual donations, increasingly wealthy industrialists and financiers left generous sums in their wills. A sample of 466 wills in the 1890s revealed a total wealth of £76 million, of which £20 million was bequeathed to charities. By 1900 London charities enjoyed an annual income of about £8.5 million.[12]

Led by the energetic Lord Shaftesbury (1801–1885), philanthropists organized themselves.[13] In 1869 they set up the Charity Organisation Society. It was a federation of district committees, one in each of the 42 Poor Law divisions. Its central office had experts in coordination and guidance, thereby maximizing the impact of charitable giving to the poor.[14] Many of the charities were designed to alleviate the harsh living conditions in the slums. such as the Labourer's Friend Society founded in 1830. This included the promotion of allotment of land to labourers for "cottage husbandry" that later became the allotment movement, and in 1844 it became the first Model Dwellings Company—an organization that sought to improve the housing conditions of the working classes by building new homes for them, while at the same time receiving a competitive rate of return on any investment. This was one of the first housing associations, a philanthropic endeavor that flourished in the second half of the nineteenth century, brought about by the growth of the middle class. Later associations included the Peabody Trust, and the Guinness Trust. The principle of philanthropic intention with capitalist return was given the label "five per cent philanthropy."[15][16]

Switzerland

In 1863, the Swiss businessman Henry Dunant used his fortune to fund the Geneva Society for Public Welfare, which became the International Committee of the Red Cross. During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, Dunant personally led Red Cross delegations that treated soldiers. He shared the first Nobel Peace Prize for this work in 1901.[17]

The French Red Cross played a minor role in the war with Germany (1870–71). After that, it became a major factor in shaping French civil society as a non-religious humanitarian organization. It was closely tied to the army's Service de Santé. By 1914 it operated one thousand local committees with 164,000 members, 21,500 trained nurses, and over 27 million francs in assets.[18]

The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) played a major role in working with POW's on all sides in World War II. It was in a cash-starved position when the war began in 1939, but quickly mobilized its national offices set up a Central Prisoner of War Agency. For example, it provided food, mail and assistance to 365,000 British and Commonwealth soldiers and civilians held captive. Suspicions, especially by London, of ICRC as too tolerant or even complicit with Nazi Germany led to its side-lining in favour of the UN Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) as the primary humanitarian agency after 1945.[19]

France

In France, the Pasteur Institute had a monopoly of specialized microbiological knowledge allowed it to raise money for serum production from both private and public sources, walking the line between a commercial pharmaceutical venture and a philanthropic enterprise.[20]

By 1933, at the depth of the Great Depression, the French wanted a welfare state to relieve distress but did not want new taxes. War veterans came up with a solution: the new national lottery proved highly popular to gamblers, while generating the cash needed without raising taxes.[21]

American money proved invaluable. The Rockefeller Foundation opened an office in Paris and helped design and fund France's modern public health system, under the National Institute of Hygiene. It also set up schools to train physicians and nurses.[22][23]

Germany

The history of modern philanthropy on the European Continent is especially important in the case of Germany, which became a model for others, especially regarding the welfare state. The princes and in the various imperial states continued traditional efforts, such as monumental buildings, parks and art collections. Starting in the early 19th century, the rapidly emerging middle classes made local philanthropy a major endeavor to establish their legitimate role in shaping society, in contradistinction to the aristocracy and the military. They concentrated on support for social welfare institutions, higher education, and cultural institutions, as well as some efforts to alleviate the hardships of rapid industrialization. The bourgeoisie (upper-middle-class) was defeated in its effort to it gain political control in 1848, but it still had enough money and organizational skills that could be employed through philanthropic agencies to provide an alternative powerbase for its world view.[24]

Religion was a divisive element in Germany, as the Protestants, Catholics and Jews used alternative philanthropic strategies. The Catholics, for example, continued their medieval practice of using financial donations in their wills to lighten their punishment in purgatory after death. The Protestants did not believe in purgatory, but made a strong commitment to the improvement of their communities there and then. Conservative Protestants raised concerns about deviant sexuality, alcoholism and socialism, as well as illegitimate births. They used philanthropy to try to eradicate what they considered as "social evils" that were seen as utterly sinful.[25][26] All the religious groups used financial endowments, which multiplied in the number and wealth as Germany grew richer. Each was devoted to a specific benefit to that religious community, and each had a board of trustees; these were laymen who donated their time to public service.

Chancellor Otto von Bismarck, an upper class Junker, used his state-sponsored philanthropy, in the form of his invention of the modern welfare state, to neutralize the political threat posed by the socialistic labor unions.[27] The middle classes, however, made the most use of the new welfare state, in terms of heavy use of museums, gymnasiums (high schools), universities, scholarships, and hospitals. For example, state funding for universities and gymnasiums covered only a fraction of the cost; private philanthropy became the essential ingredient. 19th-century Germany was even more oriented toward civic improvement than Britain or the United States, when measured in terms of voluntary private funding for public purposes. Indeed, such German institutions as the kindergarten, the research university, and the welfare state became models copied by the Anglo-Saxons.[28]

The heavy human and economic losses of the First World War, the financial crises of the 1920s, as well as the Nazi regime and other devastation by 1945, seriously undermined and weakened the opportunities for widespread philanthropy in Germany. The civil society so elaborately build up in the 19th century was practically dead by 1945. However, by the 1950s, as the "economic miracle" was restoring German prosperity, the old aristocracy was defunct, and middle-class philanthropy started to return to importance.[29]

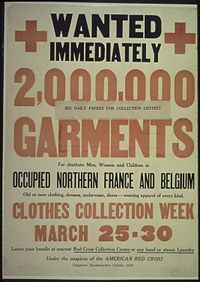

War and postwar: Belgium and Eastern Europe

The Commission for Relief in Belgium (CRB) was an international (predominantly American) organization that arranged for the supply of food to German-occupied Belgium and northern France during the First World War. It was led by Herbert Hoover.[30] Between 1914 and 1919, the CRB operated entirely with voluntary efforts and was able to feed 11,000,000 Belgians by raising the necessary money, obtaining voluntary contributions of money and food, shipping the food to Belgium and controlling it there. For example, the CRB shipped 697,116,000 pounds of flour to Belgium.[31] Biographer George Nash finds that by the end of 1916, Hoover "stood preeminent in the greatest humanitarian undertaking the world had ever seen."[32] Biographer William Leuchtenburg adds, "He had raised and spent millions of dollars, with trifling overhead and not a penny lost to fraud. At its peak, his organization was feeding nine million Belgians and French a day.[33]

When the war ended in late 1918, Hoover took control of the American Relief Administration (ARA), with the mission of food to Central and Eastern Europe. The ARA fed millions.[34] U.S. government funding for the ARA expired in the summer of 1919, and Hoover transformed the ARA into a private organization, raising millions of dollars from private donors. Under the auspices of the ARA, the European Children's Fund fed millions of starving children. When attacked for distributing food to Russia, which was under Bolshevik control, Hoover snapped, "Twenty million people are starving. Whatever their politics, they shall be fed!"[35][36]

United States

The first corporation founded in the Thirteen Colonies was Harvard College (1636), designed primarily to train young men for the clergy. A leading theorist was the Puritan theologian Cotton Mather (1662–1728), who in 1710 published a widely read essay, Bonifacius, or an Essay to Do Good. Mather worried that the original idealism had eroded, so he advocated philanthropic benefaction as a way of life. Though his context was Christian, his idea was also characteristically American and explicitly Classical, on the threshold of the Enlightenment.[37]

Benjamin Franklin (1706–1790) was an activist and theorist of American philanthropy. He was much influenced by Daniel Defoe's An Essay upon Projects (1697) and Cotton Mather's Bonifacius: an essay upon the good. (1710). Franklin attempted to motivate his fellow Philadelphians into projects for the betterment of the city: examples included the Library Company of Philadelphia (the first American subscription library), the fire department, the police force, street lighting and a hospital. A world-class physicist himself, he promoted scientific organizations including the Philadelphia Academy (1751) – which became the University of Pennsylvania – as well as the American Philosophical Society (1743), to enable scientific researchers from all 13 colonies to communicate.[38]

By the 1820s, newly rich American businessmen were initiating philanthropic work, especially with respect to private colleges and hospitals. George Peabody (1795–1869) is the acknowledged father of modern philanthropy. A financier based in Baltimore and London, in the 1860s he began to endow libraries and museums in the United States, and also funded housing for poor people in London. His activities became the model for Andrew Carnegie and many others.[39][40]

Andrew Carnegie

Andrew Carnegie (1835–1919) was the most influential leader of philanthropy on a national (rather than local) scale. After selling his steel company in 1901 he devoted himself to establishing philanthropic organizations, and making direct contributions to many educational, cultural and research institutions. He financed over 2500 public libraries built across the nation and abroad. He also funded Carnegie Hall in New York City and the Peace Palace in the Netherlands. His final and largest project was the Carnegie Corporation of New York, founded in 1911 with a $25 million endowment, later enlarged to $135 million. Carnegie Corporation has endowed or otherwise helped to establish institutions that include the Russian Research Center at Harvard University (now known as the Davis Center for Russian and Eurasian Studies),[41] the Brookings Institution and the Sesame Workshop. In all, Andrew Carnegie gave away 90% of his fortune.[42]

John D. Rockefeller

Other prominent American philanthropists of the early 20th century included John D. Rockefeller (1839–1937), Julius Rosenwald (1862–1932)[43][44] and Margaret Olivia Slocum Sage (1828–1918).[45] Rockefeller retired from business in the 1890s; he and his son John D. Rockefeller Jr. (1874–1960) made large-scale national philanthropy systematic, especially with regard to the study and application of modern medicine, higher education and scientific research. Of the $530 million the elder Rockefeller gave away, $450 million went to medicine.[46] Their leading advisor Frederick Taylor Gates launched several very large philanthropic projects staffed by experts who sought to address problems systematically at the roots rather than let the recipients deal only with their immediate concerns.[47]

By 1920, the Rockefeller Foundation was opening offices in Europe. It launched medical and scientific projects in Britain, France, Germany, Spain, and elsewhere. It supported the health projects of the League of Nations.[48] By the 1950s, it was investing heavily in the Green Revolution, especially the work by Norman Borlaug that enabled India, Mexico and many poor countries to dramatically upgrade their agricultural productivity.[49]

Ford Foundation