Sword-and-sandal, also known as peplum (pepla plural), is a subgenre of largely Italian-made historical, mythological, or biblical epics mostly set in the Greco-Roman antiquity or the Middle Ages. These films attempted to emulate the big-budget Hollywood historical epics of the time, such as Samson and Delilah (1949), Quo Vadis (1951), The Robe (1953), The Ten Commandments (1956), Ben-Hur (1959), Spartacus (1960), and Cleopatra (1963).[1] These films dominated the Italian film industry from 1958 to 1965, eventually being replaced in 1965 by spaghetti Western and Eurospy films.[2][3]

The term "peplum" (a Latin word referring to the ancient Greek garment peplos), was introduced by French film critics in the 1960s.[2][3] The terms "peplum" and "sword-and-sandal" were used in a condescending way by film critics. Later, the terms were embraced by fans of the films, similar to the terms "spaghetti Western" or "shoot-'em-ups". In their English versions, peplum films can be immediately differentiated from their Hollywood counterparts by their use of "clumsy and inadequate" English language dubbing.[4] A 100-minute documentary on the history of Italy's peplum genre was produced and directed by Antonio Avati in 1977 entitled Kolossal: i magnifici Maciste (aka Kino Kolossal).[5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12]

Genre characteristics

Sword-and-sandal films are a specific class of Italian adventure films that have subjects set in Biblical or classical antiquity, often with plots based more or less loosely on Greco-Roman history or the other contemporary cultures of the time, such as the Egyptians, Assyrians, and Etruscans, as well as medieval times. Not all of the films were fantasy-based by any means. Many of the plots featured actual historical personalities such as Julius Caesar, Cleopatra, and Hannibal, although great liberties were taken with the storylines. Gladiators and slaves rebelling against tyrannical rulers, pirates and swashbucklers were also popular subjects.

As Robert Rushing defines it, peplum, "in its most stereotypical form, [...] depicts muscle-bound heroes (professional bodybuilders, athletes, wrestlers, or brawny actors) in mythological antiquity, fighting fantastic monsters and saving scantily clad beauties. Rather than lavish epics set in the classical world, they are low-budget films that focus on the hero's extraordinary body."[13] Thus, most sword-and-sandal films featured a superhumanly strong man as the protagonist, such as Hercules, Samson, Goliath, Ursus or Italy's own popular folk hero Maciste. In addition, the plots typically involved two women vying for the affection of the bodybuilder hero: the good love interest (a damsel in distress needing rescue), and an evil femme fatale queen who sought to dominate the hero.

Also, the films typically featured an ambitious ruler who would ascend the throne by murdering those who stood in his path, and often it was only the muscular hero who could depose him. Thus the hero's often political goal: "to restore a legitimate sovereign against an evil dictator."[14]

Many of the peplum films involved a clash between two populations, one civilized and the other barbaric, which typically included a scene of a village or city being burned to the ground by invaders. For their musical content, most films contained a colorful dancing girls sequence, meant to underline pagan decadence.

Precursors of the sword-and-sandal wave (pre-1958)

Italian films of the silent era

Italian filmmakers paved the way for the peplum genre with some of the earliest silent films dealing with the subject, including the following:

- The Sack of Rome (1905)

- Agrippina (1911)

- The Fall of Troy (1911)

- The Queen of Nineveh (1911, directed by Luigi Maggi)

- Brutus (1911)

- Quo Vadis (1913, directed by Enrico Guazzoni)

- Antony and Cleopatra (1913)

- Cabiria (1914, directed by Giovanni Pastrone)

- Julius Caesar (1914)

- Saffo (Sappho, 1918, directed by Antonio Molinari)

- The Crusaders (1918)

- Fabiola (1918) directed by Enrico Guazzoni

- Attila (1919, directed by F. Mari)

- Venere (Venus, 1919, directed by Antonio Molinari)

- Il mistero di Osiris (The Mystery of Osiris, 1919) directed by Antonio Molinari

- Giuliano l'Apostata (1919, directed by Ugo Falena)

- Giuditta e Oloferne (Judith and Holofernes, 1920) directed by Antonio Molinari

- The Sack of Rome, (1920) directed by Enrico Guazzoni

- Messalina, (1924) directed by Enrico Guazzoni

- Gli ultimi giorni di Pompei (The Last Days of Pompeii (1926) directed by Carmine Gallone and Amleto Palermi)[15]

The silent Maciste films (1914–1927)

The 1914 Italian silent film Cabiria was one of the first films set in antiquity to make use of a massively muscled character, Maciste (played by actor Bartolomeo Pagano), who served in this premiere film as the hero's slavishly loyal sidekick. Maciste became the public's favorite character in the film however, and Pagano was called back many times to reprise the role. The Maciste character appeared in at least two dozen Italian silent films from 1914 through 1926, all of which featured a protagonist named Maciste although the films were set in many different time periods and geographical locations.

Here is a complete list of the silent Maciste films in chronological order:

- Cabiria (1914) introduced the Maciste character

- Maciste (1915) a.k.a. "The Marvelous Maciste"

- Maciste bersagliere ("Maciste the Ranger", 1916)

- Maciste alpino ("Maciste The Warrior", 1916)

- Maciste atleta ("Maciste the Athlete", 1917)

- Maciste medium ("Maciste the Clairvoyant", 1917)

- Maciste poliziotto ("Maciste the Detective", 1917)

- Maciste turista ("Maciste the Tourist", 1917)

- Maciste sonnambulo ("Maciste the Sleepwalker", 1918)

- La Rivincita di Maciste ("The Revenge of Maciste", 1919)

- Il Testamento di Maciste ("Maciste's Will", 1919)

- Il Viaggio di Maciste ("Maciste's Journey", 1919)

- Maciste I ("Maciste the First", 1919)

- Maciste contro la morte ("Maciste vs Death", 1919)

- Maciste innamorato ("Maciste in Love", 1919)

- Maciste in vacanza ("Maciste on Vacation", 1920)

- Maciste salvato dalle acque ("Maciste Rescued from the Waters", 1920)

- Maciste e la figlia del re della plata ("Maciste and the Silver King's Daughter", 1922)

- Maciste und die Japanerin ("Maciste and the Japanese", 1922)

- Maciste contro Maciste ("Maciste vs. Maciste", 1923)

- Maciste und die chinesische truhe ("Maciste and the Chinese Trunk", 1923)

- Maciste e il nipote di America ("Maciste's American Nephew", 1924)

- Maciste imperatore ("Emperor Maciste", 1924)

- Maciste contro lo sceicco ("Maciste vs. the Sheik", 1925)

- Maciste all'inferno ("Maciste in Hell", 1925)

- Maciste nella gabbia dei leoni ("Maciste in the Lions' Den", 1926)

- il Gigante delle Dolemite ("The Giant From the Dolomite", released in 1927)

Italian fascist and post-war historical epics (1937-1956)

The Italian film industry released several historical films in the early sound era, such as the big-budget Scipione l'Africano (Scipio Africanus: The Defeat of Hannibal) in 1937. In 1949, the postwar Italian film industry remade Fabiola (which had been previously filmed twice in the silent era). The film was released in the United Kingdom and in the United States in 1951 in an edited, English-dubbed version. Fabiola was an Italian-French co-production like the following films The Last Days of Pompeii (1950) and Messalina (1951).

During the 1950s, a number of American historical epics shot in Italy were released. In 1951, MGM producer Sam Zimbalist cleverly used the lower production costs, use of frozen funds and the expertise of the Italian film industry to shoot the large-scale Technicolor epic Quo Vadis in Rome. In addition to its fictional account linking the Great Fire of Rome, the Persecution of Christians in the Roman Empire and Emperor Nero, the film - following the novel "Quo vadis" by the Polish writer Henryk Sienkiewicz - featured also a mighty protagonist named Ursus (Italian filmmakers later made several pepla in the 1960s exploiting the Ursus character). MGM also planned Ben Hur to be filmed in Italy as early as 1952.[16]

Riccardo Freda's Sins of Rome was filmed in 1953 and released by RKO in an edited, English-dubbed version the following year. Unlike Quo Vadis, there were no American actors or production crew. The Anthony Quinn film Attila (directed by Pietro Francisci in 1954), the Kirk Douglas epic Ulysses (co-directed by an uncredited Mario Bava in 1954) and Helen of Troy (directed by Robert Wise with Sergio Leone as an uncredited second unit director in 1955) were the first of the big peplum films of the 1950s. Riccardo Freda directed another peplum, Theodora, Slave Empress in 1954, starring his wife Gianna Maria Canale. Howard Hawks directed his Land of the Pharaohs (starring Joan Collins) in Italy and Egypt in 1955. Robert Rossen made his film Alexander the Great in Egypt in 1956, with a music score by famed Italian composer Mario Nascimbene.

The main sword-and-sandal period (1958-1965)

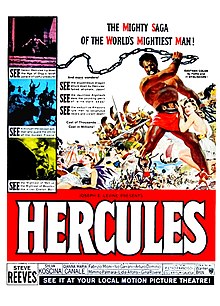

To cash in on the success of the Kirk Douglas film Ulysses, Pietro Francisci planned to make a film about Hercules, but searched unsuccessfully for years for a physically convincing yet experienced actor. His daughter spotted American bodybuilder Steve Reeves in the American film Athena and he was hired to play Hercules in 1957 when the film was made. (Reeves was paid $10,000 to star in the film).[17][18]

The genre's instantaneous growth began with the U.S. theatrical release of Hercules in 1959. American producer Joseph E. Levine acquired the U.S. distribution rights for $120,000, spent $1 million promoting the film and made more than $5 million profit.[19] This spawned the 1959 Steve Reeves sequel Hercules Unchained, the 1959 re-release of Cecil B. DeMille's Samson and Delilah (1949), and dozens of imitations that followed in their wake. Italian filmmakers resurrected their 1920s Maciste character in a brand new 1960s sound film series (1960–1964), followed rapidly by Ursus, Samson, Goliath and various other mighty-muscled heroes.

Almost all peplum films of this period featured bodybuilder stars, the most popular being Steve Reeves, Reg Park and Gordon Scott.[20] Some of these stars, such as Mickey Hargitay, Reg Lewis, Mark Forest, Gordon Mitchell and Dan Vadis, had starred in Mae West's touring stage review in the United States in the 1950s.[20] Bodybuilders of Italian origin, on the other hand, would adopt English pseudonyms for the screen; thus, stuntman Sergio Ciani became Alan Steel, and ex-gondolier Adriano Bellini was called Kirk Morris.[20]

To be sure, many of the films enjoyed widespread popularity among general audiences, and had production values that were typical for popular films of their day. Some films included frequent re-use of the impressive film sets that had been created for Ben-Hur and Cleopatra.

Although many of the bigger budget pepla were released theatrically in the US, fourteen of them were released directly to Embassy Pictures television in a syndicated TV package called The Sons of Hercules. Since few American viewers had a familiarity with Italian film heroes such as Maciste or Ursus, the characters were renamed[20] and the films molded into a series of sorts by splicing on the same opening and closing theme song and newly designed voice-over narration that attempted to link the protagonist of each film to the Hercules mythos. These films ran on Saturday afternoons in the 1960s.

Peplum films were, and still are, often ridiculed for their low budgets and bad English dubbing. The contrived plots, poorly overdubbed dialogue, novice acting skills of the bodybuilder leads, and primitive special effects that were often inadequate to depict the mythological creatures on screen all conspire to give these films a certain camp appeal now. In the 1990s, several of them have been subjects of riffing and satire in the United States comedy series Mystery Science Theater 3000.

However, in the early 1960s, a group of French critics, mostly writing for the Cahiers du cinéma, such as Luc Moullet, started to celebrate the genre and some of its directors, including Vittorio Cottafavi, Riccardo Freda, Mario Bava, Pietro Francisci, Duccio Tessari, and Sergio Leone.[21] Not only directors, but also some of the screenwriters, often put together in teams, worked past the typically formulaic plot structure to include a mixture of "bits of philosophical readings and scraps of psychoanalysis, reflections on the biggest political systems, the fate of the world and humanity, fatalistic notions of accepting the will of destiny and the gods, anthropocentric belief in the powers of the human physique, and brilliant syntheses of military treatises".[22]

With reference to the genre's free use of ancient mythology and other influences, Italian director Vittorio Cottafavi, who directed a number of peplum films, used the term "neo-mythologism".[23]

Hercules series (1958–1965)

A series of 19 Hercules movies were made in Italy in the late '50s and early '60s. The films were all sequels to the successful Steve Reeves peplum Hercules (1958), but with the exception of Hercules Unchained, each film was a stand-alone story not connected to the others. The actors who played Hercules in these films were Steve Reeves followed by Gordon Scott, Kirk Morris, Mickey Hargitay, Mark Forest, Alan Steel, Dan Vadis, Brad Harris, Reg Park, Peter Lupus (billed as Rock Stevens) and Mike Lane. In a 1997 interview, Reeves said he felt his two Hercules films could not be topped by another sequel, so he declined to do any more Hercules films.[24]

The films are listed below by their American release titles, and the titles in parentheses are their original Italian titles with an approximate English translation. Dates shown are the original Italian theatrical release dates, not the U.S. release dates (which were years later in some cases).

- Hercules (Le fatiche di Ercole / The Labors of Hercules, 1958) starring Steve Reeves

- Hercules Unchained (Ercole e la regina di Lidia / Hercules and the Queen of Lydia, 1959) starring Steve Reeves

- Goliath and the Dragon (La vendetta di Ercole / The Revenge of Hercules, 1960) starring Mark Forest as Hercules (Hercules' name was changed to Goliath when this film was dubbed in English and distributed in the U.S.)

- Hercules Vs The Hydra (Gli amori di Ercole / The Loves of Hercules, 1960) co-starring Mickey Hargitay (as Hercules) and Jayne Mansfield

- Hercules and the Captive Women (Ercole alla conquista di Atlantide / Hercules at the Conquest of Atlantis, 1961) starring Reg Park as Hercules (alternate U.S. title: Hercules and the Haunted Women)

- Hercules in the Haunted World (Ercole al centro della terra / Hercules at the Center of the Earth, 1961) directed by Mario Bava, starring Reg Park as Hercules

- Hercules in the Vale of Woe (Maciste contro Ercole nella valle dei guai / Maciste vs Hercules in the Vale of Woe) comedy starring Frank Gordon as Hercules, 1961

- Ulysses Against the Son of Hercules (Ulisse contro Ercole / Ulysses vs. Hercules) starring Mike Lane as Hercules, 1962

- The Fury of Hercules (La furia di Ercole / The Fury of Hercules) starring Brad Harris as Hercules, 1962 (alternate U.S. title: The Fury of Samson)

- Hercules, Samson and Ulysses (Ercole sfida Sansone / Hercules Challenges Samson) starring Kirk Morris as Hercules, 1963

- Hercules Against Moloch (Ercole contro Molock / Hercules vs. Molock) starring Gordon Scott as Hercules, 1963 (a.k.a. The Conquest of Mycenae)

- Son of Hercules in the Land of Darkness (Ercole l'invincibile / Hercules the Invincible) starring Dan Vadis as Hercules, 1964. (this was originally a Hercules film that was re-titled for inclusion in the U.S. syndicated TV package The Sons of Hercules).

- Hercules vs The Giant Warriors (il trionfo di Ercole / The Triumph of Hercules) starring Dan Vadis as Hercules, 1964 (alternate U.S. title: Hercules and the Ten Avengers)

- Hercules Against Rome (Ercole contro Roma / Hercules vs. Rome) starring Alan Steel as Hercules, 1964

- Hercules Against the Sons of the Sun (Ercole contro i figli del sole / Hercules vs. the Sons of the Sun) starring Mark Forest as Hercules, 1964

- Samson and His Mighty Challenge (Ercole, Sansone, Maciste e Ursus: gli invincibili / Hercules, Samson, Maciste and Ursus: The Invincibles) starring Alan Steel as Hercules, 1964 (a.k.a. Combate dei Gigantes or Le Grand Defi)

- Hercules and the Tyrants of Babylon (Ercole contro i tiranni di Babilonia / Hercules vs. the Tyrants of Babylon) starring Rock Stevens as Hercules, 1964

- Hercules and the Princess of Troy (no Italian title) starring Gordon Scott as Hercules, 1965 (a.k.a. Hercules vs. the Sea Monster; this U.S./ Italian co-production was made as a pilot for a Charles Band-produced TV series that never materialized and it was later distributed as a feature film)

- Hercules the Avenger (Sfida dei giganti / Challenge of the Giants) starring Reg Park as Hercules, 1965 (this film was composed mostly of re-edited footage from the two 1961 Reg Park Hercules films)

A number of English-dubbed Italian films that featured the word "Hercules" in the title were not made as Hercules movies originally, such as:

- Hercules Against the Moon Men, Hercules Against the Barbarians, Hercules Against the Mongols and Hercules of the Desert were all originally Maciste films. (See "Maciste" section below)

- Hercules and the Black Pirate and Hercules and the Treasure of the Incas were both re-titled Samson movies. (See "Samson" section below)

- Hercules, Prisoner of Evil was actually a re-titled Ursus film. (See "Ursus" section below)

- Hercules and the Masked Rider was actually a re-titled Goliath movie. (See "Goliath" section below)

None of these films in their original Italian versions involved the Hercules character in any way. Likewise, most of the Sons of Hercules movies shown on American TV in the 1960s had nothing to do with Hercules in their original Italian versions.

(see also The Three Stooges Meet Hercules (1962), an American-made genre parody starring peplum star Samson Burke as Hercules)

Goliath series (1959–1964)

The Italians used Goliath as the superhero protagonist in a series of adventure films (pepla) in the early 1960s. He was a man possessed of amazing strength, although he seemed to be a different person in each film. After the classic Hercules (1958) became a blockbuster sensation in the film industry, a 1959 Steve Reeves film Il terrore dei barbari (Terror of the Barbarians) was re-titled Goliath and the Barbarians in the U.S. The film was so successful at the box office, it inspired Italian filmmakers to do a series of four more films featuring a generic beefcake hero named Goliath, although the films were not related to each other in any way (the 1960 Italian peplum David and Goliath starring Orson Welles was not part of this series, since that movie was just a historical retelling of the Biblical story).

The titles in the Italian Goliath adventure series were as follows: (the first title listed for each film is the film's original Italian title along with its English translation, while the U.S. release title follows in bold type in parentheses)

- Il terrore dei barbari / Terror of the Barbarians (1959) (Goliath and the Barbarians in the U.S.), starring Steve Reeves as Goliath (although he is referred to as "Emiliano" in the original Italian-language version)

- Goliath contro i giganti / Goliath Against the Giants (Goliath Against the Giants) (1960) starring Brad Harris

- Goliath e la schiava ribelle / Goliath and the Rebel Slave (Tyrant of Lydia Against The Son of Hercules) (1963) starring Gordon Scott

- Golia e il cavaliere mascherato / Goliath and the Masked Rider (Hercules and the Masked Rider) (1964) starring Alan Steel (note: Goliath is referred to as "Hercules" in English-dubbed prints)

- Golia alla conquista di Bagdad / Goliath at the Conquest of Baghdad (Goliath at the Conquest of Damascus, 1964) starring Rock Stevens (aka Peter Lupus)

The name Goliath was also inserted into the English titles of three other Italian pepla that were re-titled for U.S. distribution in an attempt to cash in on the Goliath craze, but these films were not originally made as "Goliath movies" in Italy.

Both Goliath and the Vampires (1961) and Goliath and the Sins of Babylon (1963) actually featured the famed Italian folk hero Maciste in the original Italian versions, but American distributors did not feel the name "Maciste" meant anything to American audiences.

Goliath and the Dragon (1960) was originally an Italian Hercules movie called The Revenge of Hercules, but it was re-titled Goliath and the Dragon in the U.S. since at the time Goliath and the Barbarians was breaking box-office records, and the distributors may have thought the name "Hercules" was trademarked by distributor Joseph E. Levine.

Maciste series (1960–1965)

There were a total of 25 Maciste films from the 1960s peplum craze

(not counting the two dozen silent Maciste films made in Italy

pre-1930). By 1960, seeing how well the two Steve Reeves Hercules films were doing at the box office, Italian producers decided to revive the 1920s silent film character Maciste

in a new series of color/sound films. Unlike the other Italian peplum

protagonists, Maciste found himself in a variety of time periods ranging

from the Ice Age

to 16th century Scotland. Maciste was never given an origin, and the

source of his mighty powers was never revealed. However, in the first

film of the 1960s series, he mentions to another character that the name

"Maciste" means "born of the rock" (almost as if he was a god who would

just appear out of the earth itself in times of need). One of the 1920s

silent Maciste films was actually entitled "The Giant from the

Dolomite", hinting that Maciste may be more god than man, which would

explain his great strength.

The first title listed for each film is the film's original Italian

title along with its English translation, while the U.S. release title

follows in bold type in parentheses (note how many times Maciste's name

in the Italian title is altered to an entirely different name in the

American title):

- Maciste nella valle dei re / Maciste in the Valley of the Kings (Son of Samson, 1960) a.k.a. Maciste the Mighty, a.k.a. Maciste the Giant, starring Mark Forest

- Maciste nella terra dei ciclopi / Maciste in the Land of the Cyclops (Atlas in the Land of the Cyclops, 1961) starring Gordon Mitchell

- Maciste contro il vampiro / Maciste Vs. the Vampire (Goliath and the Vampires, 1961) starring Gordon Scott

- Il trionfo di Maciste / The Triumph of Maciste (Triumph of the Son of Hercules, 1961) starring Kirk Morris

- Maciste alla corte del gran khan / Maciste at the Court of the Great Khan (Samson and the Seven Miracles of the World, 1961) starring Gordon Scott

- Maciste, l'uomo più forte del mondo / Maciste, the Strongest Man in the World (Mole Men vs the Son of Hercules, 1961) starring Mark Forest

- Maciste contro Ercole nella valle dei guai / Maciste Against Hercules in the Vale of Woe (Hercules in the Vale of Woe, 1961) starring Kirk Morris as Maciste; this was a satire/spoof featuring the comedy team of Franco and Ciccio

- Totò contro Maciste / Totò vs. Maciste (no American title, 1962) starring Samson Burke; this was a comedy satirizing the peplum genre (part of the Italian "Toto" film series) and was never distributed in the U.S.; it is apparently not even available in English

- Maciste all'inferno / Maciste in Hell (The Witch's Curse, 1962) starring Kirk Morris

- Maciste contro lo sceicco / Maciste Against the Sheik (Samson Against the Sheik, 1962) starring Ed Fury

- Maciste, il gladiatore piu forte del mondo / Maciste, the World's Strongest Gladiator (Colossus of the Arena, 1962) starring Mark Forest

- Maciste contro i mostri / Maciste Against the Monsters (Fire Monsters Against the Son of Hercules, 1962) starring Reg Lewis

- Maciste contro i cacciatori di teste / Maciste Against the Headhunters (Colossus and the Headhunters, 1962) starring Kirk Morris; a.k.a. Fury of the Headhunters

- Maciste, l'eroe piu grande del mondo / Maciste, the World's Greatest Hero (Goliath and the Sins of Babylon, 1963) starring Mark Forest

- Zorro contro Maciste / Zorro Against Maciste (Samson and the Slave Queen, 1963) starring Alan Steel

- Maciste contro i mongoli / Maciste Against the Mongols (Hercules Against the Mongols, 1963) starring Mark Forest

- Maciste nell'inferno di Gengis Khan / Maciste in Genghis Khan's Hell (Hercules Against the Barbarians, 1963) starring Mark Forest

- Maciste alla corte dello zar / Maciste at the Court of the Czar (Atlas Against The Czar, 1964) starring Kirk Morris (a.k.a. Samson vs. the Giant King)

- Maciste, gladiatore di Sparta / Maciste, Gladiator of Sparta (Terror of Rome Against the Son of Hercules, 1964) starring Mark Forest

- Maciste nelle miniere de re salomone / Maciste in King Solomon's Mines (Samson in King Solomon's Mines, 1964) starring Reg Park

- Maciste e la regina de Samar / Maciste and the Queen of Samar (Hercules Against the Moon Men, 1964) starring Alan Steel

- La valle dell'eco tonante / Valley of the Thundering Echo (Hercules of the Desert, 1964) starring Kirk Morris, a.k.a. Desert Raiders, a.k.a. in France as Maciste and the Women of the Valley

- Ercole, Sansone, Maciste e Ursus: gli invincibili / Hercules, Samson, Maciste and Ursus: The Invincibles (Samson and His Mighty Challenge, 1964) starring Renato Rossini as Maciste (a.k.a. Combate dei Gigantes or Le Grand Defi)

- Gli invicibili fratelli Maciste / The Invincible Maciste Brothers (The Invincible Brothers Maciste, 1964) a.k.a. The Invincible Gladiators, starring Richard Lloyd as Maciste

- Maciste il Vendicatore dei Mayas / Maciste, Avenger of the Mayans (has no American title, 1965) (Note:* this Maciste film was made up almost entirely of re-edited stock footage from two older Maciste films, Maciste contro i mostri and Maciste contro i cacciatori di teste, so Maciste switches from Kirk Morris to Reg Lewis in various scenes; this movie is very scarce since it was never distributed in the U.S. and is apparently not even available in English)

In 1973, the Spanish cult film director Jesus Franco directed two low-budget "Maciste films" for French producers: Maciste contre la Reine des Amazones (Maciste vs the Queen of the Amazons) and Les exploits érotiques de Maciste dans l'Atlantide (The Erotic Exploits of Maciste in Atlantis). The films had almost identical casts, both starring Val Davis as Maciste, and appear to have been shot back-to-back. The former was distributed in Italy as a "Karzan" movie (a cheap Tarzan imitation), while the latter film was released only in France with hardcore inserts as Les Gloutonnes ("The Gobblers"). These two films were totally unrelated to the 1960s Italian Maciste series.

Ursus series (1960–1964)

Following Buddy Baer's portrayal of Ursus in the classic 1951 film Quo Vadis, Ursus was used as a superhuman Roman-era character who became the protagonist in a series of Italian adventure films made in the early 1960s.

When the "Hercules" film craze hit in 1959, Italian filmmakers were looking for other muscleman characters similar to Hercules whom they could exploit, resulting in the nine-film Ursus series listed below. Ursus was referred to as a "Son of Hercules" in two of the films when they were dubbed in English (in an attempt to cash in on the then-popular "Hercules" craze), although in the original Italian films, Ursus had no connection to Hercules whatsoever. In the English-dubbed version of one Ursus film (retitled Hercules, Prisoner of Evil), Ursus was actually referred to throughout the entire film as "Hercules".

There were a total of nine Italian films that featured Ursus as the main character, listed below as follows: Italian title / English translation of the Italian title (American release title);

- Ursus / Ursus (Ursus, Son of Hercules, 1960) a.k.a. Mighty Ursus (United Kingdom), starring Ed Fury

- La Vendetta di Ursus / The Revenge of Ursus (The Vengeance of Ursus, 1961) starring Samson Burke

- Ursus e la Ragazza Tartara / Ursus and the Tartar Girl (Ursus and the Tartar Princess, 1961) a.k.a. The Tartar Invasion, a.k.a. The Tartar Girl; starring Joe Robinson, Akim Tamiroff, Yoko Tani; directed by Remigio Del Grosso

- Ursus Nella Valle dei Leoni / Ursus in the Valley of the Lions (Valley of the Lions, 1962) starring Ed Fury; this film revealed the origin story of Ursus

- Ursus il gladiatore ribelle / Ursus the Rebel Gladiator (The Rebel Gladiators, 1962) starring Dan Vadis

- Ursus Nella Terra di Fuoco / Ursus in the Land of Fire (Son of Hercules in the Land of Fire, 1963) a.k.a. Son of Atlas in the Land of Fire; starring Ed Fury

- Ursus il terrore dei Kirghisi / Ursus, the Terror of the Kirghiz (Hercules, Prisoner of Evil, 1964) starring Reg Park

- Ercole, Sansone, Maciste e Ursus: gli invincibili / Hercules, Samson, Maciste and Ursus: The Invincibles (Samson and His Mighty Challenge, 1964) starring Yan Larvor as Ursus (a.k.a. Combate dei Gigantes or Le Grand Defi)

- Gli Invincibili Tre / The Invincible Three (Three Avengers, 1964) starring Alan Steel as Ursus

Samson series (1961–1964)

A character named Samson was featured in a series of five Italian peplum films in the 1960s, no doubt inspired by the 1959 re-release of the epic Victor Mature film Samson and Delilah. The character was similar to the Biblical Samson in the third and fifth films only; in the other three, he just appears to be a very strong man (not related at all to the Biblical figure).

The titles are listed as follows: Italian title / its English translation (U.S. release title in parentheses);

- Sansone / Samson (Samson) 1961, starring Brad Harris, a.k.a. in France as Samson Against Hercules

- Sansone contro i pirati / Samson Against the Pirates (Samson and the Sea Beast) 1963, starring Kirk Morris

- Ercole sfida Sansone / Hercules challenges Samson (Hercules, Samson and Ulysses) 1963, starring Richard Lloyd

- Sansone contro il corsaro nero / Samson Against the Black Pirate (Hercules and the Black Pirate) 1963, starring Alan Steel

- Ercole, Sansone, Maciste e Ursus: gli invincibili / Hercules, Samson, Maciste and Ursus: The Invincibles (Samson and the Mighty Challenge) 1964, starring Nadir Baltimore as Samson (a.k.a. Samson and His Mighty Challenge, Combate dei Gigantes or Le Grand Défi)

The name Samson was also inserted into the U.S. titles of six other Italian movies when they were dubbed in English for U.S. distribution, although these films actually featured the adventures of the famed Italian folk hero Maciste.

Samson Against the Sheik (1962), Son of Samson (1960), Samson and the Slave Queen (1963), Samson and the Seven Miracles of the World (1961), Samson vs. the Giant King (1964), and Samson in King Solomon's Mines (1964) were all re-titled Maciste movies, because the American distributors did not feel the name Maciste was marketable to U.S. filmgoers.

Samson and the Treasure of the Incas (a.k.a. Hercules and the Treasure of the Incas) (1965) sounds like a peplum title, but was actually a spaghetti Western.

The Sons of Hercules (TV syndication package)

The Sons of Hercules was a syndicated television show that aired in the United States in the 1960s. The series repackaged 14 randomly chosen Italian peplum films by unifying them with memorable title and end title theme songs and a standard voice-over intro relating the main hero in each film to Hercules any way they could. In some areas, each film was split into two one-hour episodes, so the 14 films were shown as 28 weekly episodes. None of the films were ever theatrically released in the U.S.

The films are not listed in chronological order, since they were not really related to each other in any way. The first title listed below for each film was its American broadcast television title, followed in parentheses by the English translation of its original Italian theatrical title:

- Ursus, Son of Hercules (Ursus) 1961, starring Ed Fury, a.k.a. Mighty Ursus in England

- Mole Men vs the Son of Hercules (Maciste, the Strongest Man in the World) 1961, starring Mark Forest

- Triumph of the Son of Hercules (The Triumph of Maciste) 1961, starring Kirk Morris

- Fire Monsters Against the Son of Hercules (Maciste vs. the Monsters) 1962, starring Reg Lewis

- Venus Against the Son of Hercules (Mars, God Of War) 1962, starring Roger Browne

- Ulysses Against the Son of Hercules (Ulysses against Hercules) 1962, starring Mike Lane

- Medusa Against the Son of Hercules (Perseus The Invincible) 1962, starring Richard Harrison

- Son of Hercules in the Land of Fire (Ursus In The Land Of Fire) 1963, starring Ed Fury

- Tyrant of Lydia Against The Son of Hercules (Goliath and the Rebel Slave) 1963, starring Gordon Scott

- Messalina Against the Son of Hercules (The Last Gladiator) 1963, starring Richard Harrison

- The Beast of Babylon Against the Son of Hercules (Hero of Babylon) 1963, starring Gordon Scott, a.k.a. Goliath, King of the Slaves

- Terror of Rome Against the Son of Hercules (Maciste, Gladiator of Sparta) 1964, starring Mark Forest

- Son of Hercules in the Land of Darkness (Hercules the Invincible) 1964, starring Dan Vadis

- Devil of the Desert Against the Son of Hercules (Anthar the Invincible) 1964, starring Kirk Morris, directed by Antonio Margheriti, a.k.a. The Slave Merchants, a.k.a. Soraya, Queen of the Desert

Steve Reeves pepla (in chronological order of production)

Steve Reeves appeared in 14 pepla made in Italy from 1958 to 1964, and most of his films are highly regarded examples of the genre. His pepla are listed below in order of production, not in order of release. The U.S. release titles are shown below, followed by the original Italian title and its translation (in parentheses)

- Hercules (1958) (Le fatiche di Ercole / The Labors of Hercules) actually filmed in 1957, released in Italy in 1958, released in the U.S. in 1959

- Hercules Unchained (1959) (Ercole e la regina di Lidia / Hercules and the Queen of Lydia) released in the U.S. in 1960

- Goliath and the Barbarians (1959) (Il terrore dei barbari / Terror of the Barbarians)

- The Giant of Marathon (1959) (La battaglia di Maratona / The Battle of Marathon)

- The Last Days of Pompeii (1959) (Gli ultimi giorni di Pompei / The Last Days of Pompeii)

- The White Warrior (1959) (Hadji Murad il Diavolo Bianco / Hadji Murad, The White Devil) directed by Riccardo Freda

- Morgan, the Pirate (1960) (Morgan, il pirata/ Morgan, the Pirate)

- The Thief of Baghdad (1960) (Il Ladro di Bagdad / The Thief of Baghdad)

- The Trojan Horse (1961) (La guerra di Troia/ The Trojan War)

- Duel of the Titans (1961) (Romolo e Remo / Romulus And Remus)

- The Slave (1962) (Il Figlio di Spartaco / Son of Spartacus)

- The Avenger (1962) (La leggenda di Enea / The Legend Of Aeneas) a.k.a. The Last Glory of Troy; (this was a sequel to The Trojan Horse)

- Sandokan the Great (1963) (Sandokan, la tigre di Mompracem/ Sandokan, the Tiger of Mompracem) directed by Umberto Lenzi

- Pirates of Malaysia (1964) a.k.a. Sandokan, the Pirate of Malaysia, a.k.a. Pirates of the Seven Seas; this was a sequel to Sandokan the Great, directed by Umberto Lenzi

Other (non-series) Italian pepla

There were many 1950s and 1960s Italian pepla that did not feature a major superhero (such as Hercules, Maciste or Samson), and as such they fall into a sort of miscellaneous category. Many were of the Cappa e spada (swashbuckler) variety, though they often feature well-known characters such as Ali Baba, Julius Caesar, Ulysses, Cleopatra, the Three Musketeers, Zorro, Theseus, Perseus, Achilles, Robin Hood, and Sandokan. The first really successful Italian films of this kind were Black Eagle (1946) and Fabiola (1949).

- Adventurer of Tortuga, The (1964), starring Guy Madison

- Adventures of Mandrin, The (1952) a.k.a. Captain Adventure a.k.a. Don Juan's Night of Love a.k.a. The Affair of Madame Pompadour, starring Raf Vallone and Silvana Pampanini,

- Adventures of Scaramouche, The (1963) a.k.a. The Mask of Scaramouche, starring Gérard Barray and Gianna Maria Canale

- Alexander The Great (1956), starring Richard Burton (U.S. film with music score by Mario Nascimbene)

- Ali Baba and the Sacred Crown (1962) a.k.a. The Seven Tasks of Ali Baba, starring Richard Lloyd

- Ali Baba and the Seven Saracens (1964) a.k.a. Sinbad Against the Seven Saracens, starring Gordon Mitchell

- Alone Against Rome (1962) a.k.a. Vengeance of the Gladiators, starring Lang Jeffries and Rossana Podestà

- Anthar the Invincible (1964) a.k.a. Devil of the Desert Against the Son of Hercules, starring Kirk Morris, directed by Antonio Margheriti

- Antigone (1961) a.k.a. Rites for the Dead, starring Irene Papas, a Greek production

- Arena, The (1974) a.k.a. Naked Warriors, directed by Steve Carver and Joe D'Amato, starring Pam Grier and Margaret Markov (a late entry in the genre)

- Arms of the Avenger (1963) a.k.a. The Devils of Spartivento/ The Fighting Legions, starring John Drew Barrymore

- Atlas (1961) a.k.a. Atlas, the Winner of Athena, directed in Greece by Roger Corman, starring Michael Forest

- Attack of the Moors (1959) a.k.a. The Kings of France

- Attack of the Normans (1962) a.k.a. The Normans, a.k.a. The Vikings Attack; starring Cameron Mitchell

- Attila (1954), directed by Pietro Francisci, starring Anthony Quinn and Sophia Loren

- Avenger of the Seven Seas (1961) a.k.a. Executioner of the Seas, starring Richard Harrison and Michèle Mercier

- Avenger of Venice, The (1963), starring Brett Halsey and Gianna Maria Canale

- Bacchantes, The (1961), starring Pierre Brice and Akim Tamiroff

- Balboa (Spanish, 1963) a.k.a. Conquistadors of the Pacific

- Barabbas (1961) produced by Dino de Laurentiis, starring Anthony Quinn, filmed in Italy

- Battle of the Amazons (1973) a.k.a. Amazons: Women of Love and War, a.k.a. Beauty of the Barbarian (directed by Alfonso Brescia)

- Beatrice Cenci (1956) directed by Riccardo Freda

- Beatrice Cenci (1969) directed by Lucio Fulci

- Behind the Mask of Zorro (1966) a.k.a. The Oath of Zorro, Tony Russel

- Bible, The (1966) (a.k.a. La Bibbia), Dino de Laurentiis, Ennio Morricone music, filmed in Italy

- Black Archer, The (1959)

- Black Devil, The (1957) starred Gerard Landry

- Black Duke, The (1963), starring Cameron Mitchell

- Black Eagle, The (1946) a.k.a. Return of the Black Eagle, directed by Riccardo Freda

- Black Lancers, The (1962) a.k.a. Charge of the Black Lancers, Mel Ferrer

- Brennus, Enemy of Rome (1964) a.k.a. Battle of the Valiant, Gordon Mitchell

- Burning of Rome, The (1963) a.k.a. The Magnificent Adventurer, Brett Halsey

- Caesar Against the Pirates (1962) Gordon Mitchell

- Caesar the Conqueror (1962), starring Cameron Mitchell

- Captain Falcon (1958) Lex Barker

- Captain from Toledo, The (1966)

- Captain of Iron, The (1961) a.k.a. Revenge of the Mercenaries, Barbara Steele

- Captain Phantom (1953)

- Captains of Adventure (1961) starring Paul Muller, Gerard Landry

- Caribbean Hawk, The (1963) Yvonne Monlaur

- Carthage in Flames (1960)

- Castillian, The (1963) Cesare Romero

- Catherine of Russia (1963) directed by Umberto Lenzi

- Cavalier in the Devil's Castle (1959)

- Centurion, The (1962) a.k.a. The Conqueror of Corinth

- Challenge of the Gladiator (1965) Peter Lupus

- Cleopatra's Daughter (1960) a.k.a. The Tomb of the Kings, Debra Paget

- Colossus and the Amazon Queen (1960), Ed Fury and Rod Taylor

- Colossus of Rhodes, The (1960) directed by Sergio Leone

- Conqueror of Atlantis (1965) a.k.a. The Kingdom in the Sand, Kirk Morris (U.S. dubbed version calls the hero "Hercules")

- Conqueror of Maracaibo, The (1961)

- Conqueror of the Orient (1961) starring Rik Battaglia

- Constantine and the Cross (1960) a.k.a. Constantine the Great, starring Cornel Wilde

- Coriolanus: Hero without a Country (1963) a.k.a. Thunder of Battle, Gordon Scott

- Cossacks, The (1959) Edmund Purdom

- The Count of Braggalone (1954) aka The Last Musketeer, starring Georges Marchal

- Count of Monte Cristo, The (1961) Louis Jourdan

- Damon and Pythias (1962) a.k.a. The Tyrant of Syracuse, Guy Williams

- David and Goliath (1960) Orson Welles

- Defeat of Hannibal, The (1937) a.k.a. Scipione l'Africano

- Defeat of the Barbarians (1962) a.k.a. King Manfred

- Desert Desperadoes (1959) Akim Tamiroff

- Desert Warrior (1957) a.k.a. The Desert Lovers, Ricardo Montalban

- Devil Made a Woman, The (1959) a.k.a. A Girl Against Napoleon

- Devil's Cavaliers, The (1959)

- Diary of a Roman Virgin (1974) a.k.a. Livia, una vergine per l'impero romano, directed by Joe D'Amato (used stock footage from The Last Days of Pompeii (1959) and The Arena (1974))

- Dragon's Blood, The (1957)[25] a.k.a. Sigfrido, based on the legend of the Niebelungen, special effects by Carlo Rambaldi

- Duel of Champions (1961) a.k.a. Horatio and Curiazi, Alan Ladd

- Erik the Conqueror (1961) a.k.a. Gli Invasori/ The Invaders, directed by Mario Bava, starring Cameron Mitchell

- Esther and the King (1961) Joan Collins, Richard Egan

- Executioner of Venice, The (1963) Lex Barker, Guy Madison

- Fabiola (1949) a.k.a. The Fighting Gladiator

- Falcon of the Desert (1965) a.k.a. The Magnificent Challenge, starring Kirk Morris

- Fall of Rome, The (1961) directed by Antonio Margheriti

- Fall of the Roman Empire, The (1964) U.S. production filmed in Spain, Sophia Loren

- Fighting Musketeers, The (1961)

- Fire Over Rome (1963)

- Fury of Achilles, The (1962) Gordon Mitchell

- Fury of the Pagans (1960) a.k.a. Fury of the Barbarians

- Giant of Metropolis, The (1961) Gordon Mitchell (this peplum had a science fiction theme instead of fantasy)

- Giant of the Evil Island (1965) a.k.a. Mystery of the Cursed Island, Peter Lupus

- Giants of Rome (1964) directed by Antonio Margheriti, starring Richard Harrison

- Giants of Thessaly (1960) directed by Riccardo Freda

- Gladiator of Rome (1962) a.k.a. Battle of the Gladiators, Gordon Scott

- Gladiators Seven (1962) a.k.a. The Seven Gladiators, Richard Harrison

- Golden Arrow, The (1962) directed by Antonio Margheriti

- Gold for the Caesars (1963) Jeffrey Hunter

- Golgotha (1935) a.k.a. Behold the Man (made in France)

- Guns of the Black Witch (1961) a.k.a. Terror of the Sea, Don Megowan

- Hannibal (1959) Victor Mature

- Hawk of the Caribbean (1963) a.k.a. The Caribbean Hawk

- Head of a Tyrant (1959) a.k.a. Judith and Holophernes

- Helen of Troy (1956) starring Jacques Sernas

- Hero of Babylon (1963) a.k.a. The Beast of Babylon vs. the Son of Hercules, Gordon Scott

- Hero of Rome (1964) a.k.a. The Colossus of Rome, Gordon Scott

- Herod the Great (1958)

- Huns, The (1960) a.k.a. Queen of the Tartars

- Invasion 1700 (1962) a.k.a. With Iron and Fire, a.k.a. With Fire and Sword, a.k.a. Daggers of Blood

- Ivanhoe, the Norman Swordsman (1971) a.k.a. La spada normanna, directed by Roberto Mauri

- Invincible Gladiator, The (1961) Richard Harrison

- Invincible Swordsman, The (1963)

- The Iron Swordsman (1949) a.k.a. Count Ugolino, directed by Riccardo Freda

- Jacob, The Man Who Fought With God (1963)

- Kampf um Rom (1968) a.k.a. The Last Roman, starring Laurence Harvey, Honor Blackman, Orson Welles

- Kindar, the Invulnerable (1965) Mark Forest

- King of the Vikings (1960) a.k.a. Prince in Chains, The

- Knight of a Hundred Faces, The (1960) a.k.a. The Silver Knight, a.k.a. Knight of a Thousand Faces, The, starring Lex Barker

- Knights of Terror (1963) a.k.a. Terror of the Red Capes, Tony Russel

- Knight Without a Country (1959) a.k.a. The Faceless Rider

- Knives of the Avenger (1967) a.k.a. Viking Massacre, directed by Mario Bava, starring Cameron Mitchell

- Last Gladiator, The (1963) a.k.a. Messalina Against the Son of Hercules

- Last of the Vikings (1961), starring Cameron Mitchell

- Legions of the Nile (1959) a.k.a. The Legions of Cleopatra

- Lion of St. Mark, The (1964) Gordon Scott

- Lion of Thebes, The (1964) a.k.a. Helen of Troy, Mark Forest

- Loves of Salammbo, The (1960) a.k.a. Salambo

- Magnificent Gladiator, The (1964) Mark Forest

- Marco Polo (1962) Rory Calhoun

- Marco the Magnificent (1965) Anthony Quinn, Orson Welles

- Mars, God of War (1962) a.k.a. Venus Against the Son of Hercules

- Masked Conqueror, The (1962)

- Masked Man Against the Pirates, The (1965)

- Mask of the Musketeers (1963) a.k.a. Zorro and the Three Musketeers, starring Gordon Scott

- Massacre in the Black Forest (1967), starring Cameron Mitchell

- Messalina (1960) Belinda Lee

- Michael Strogoff (1956) a.k.a. Revolt of the Tartars

- Mighty Crusaders, The (1958) a.k.a. Jerusalem Set Free, Gianna Maria Canale

- Minotaur, The (1960) a.k.a. Theseus Against the Minotaur, a.k.a. The Warlord of Crete

- Miracle of the Wolves (1961) a.k.a. Blood on his Sword, starring Jean Marais

- Missione sabbie roventi (Mission Burning Sands) (1966) starring Renato Rossini, directed by Alfonso Brescia

- Mongols, The (1961) directed by Riccardo Freda, starring Jack Palance

- Moses the Lawgiver (1973) aka Moses in Egypt, starring Burt Lancaster, Anthony Quayle (6-hour made-for-TV Italian/British co-production) also released theatrically

- Musketeers of the Sea (1962)

- My Son, The Hero (1961) a.k.a. Arrivano i Titani, a.k.a. The Titans

- Mysterious Rider, The (1948) directed by Riccardo Freda[26]

- Mysterious Swordsman, The (1956) starring Gerard Landry

- Nero and the Burning of Rome (1953) a.k.a. Nero and Messalina

- Night of the Great Attack (1961) a.k.a. Revenge of the Borgias

- Night They Killed Rasputin, The (1960) a.k.a. The Last Czar

- Nights of Lucretia Borgia, The (1959)

- Odyssey, The (1968) a.k.a. L'Odissea, Cyclops segment directed by Mario Bava; Samson Burke played Polyphemus the Cyclops

- Old Testament, The (1962) starred Brad Harris

- Perseus the Invincible (1962) a.k.a. Medusa vs. the Son of Hercules

- Pharaoh's Woman, The (1960)

- Pia of Ptolomey (1962)

- Pirate and the Slave Girl, The (1959) a.k.a. Scimitar of the Saracen, Lex Barker

- Pirate of the Black Hawk, The (1958) Gérard Landry

- Pirate of the Half Moon (1957)

- Pirates of the Coast (1960) Lex Barker

- Pontius Pilate (1962) Basil Rathbone

- Prince with the Red Mask, The (1955) a.k.a. The Red Eagle, starring Frank Latimore

- Prisoner of the Iron Mask, The (1962) a.k.a. The Revenge of the Iron Mask

- Pugni, Pirati e Karatè (1973) a.k.a. Fists, Pirates and Karate, directed by Joe D'Amato, starring Richard Harrison (a 1970s Italian spoof of pirate movies)

- Queen for Caesar, A (1962) Gordon Scott

- Queen of Sheba (1952) directed by Pietro Francisci

- Queen of the Amazons (1960) a.k.a. Colossus and the Amazon Queen

- Queen of the Nile (1961) a.k.a. Nefertiti, Vincent Price

- Queen of the Pirates (1960) a.k.a. The Venus of the Pirates, Gianna Maria Canale

- Queen of the Seas (1961) directed by Umberto Lenzi

- Quo Vadis (1951) filmed in Italy, Sergio Leone asst. dir.

- Rage of the Buccaneers (1961) a.k.a. Gordon, The Black Pirate, starring Vincent Price

- Rape of the Sabine Women, The (1961) a.k.a. Romulus and the Sabines, Roger Moore

- Red Cloak, The (1955) Bruce Cabot

- Red Sheik, The (1962)

- Revak the Rebel (1960) a.k.a. The Barbarians, Jack Palance

- Revenge of Black Eagle, The (1951) Gianna Maria Canale

- Revenge of Ivanhoe, The (1965) Rik Battaglia

- Revenge of Spartacus, The (1965) a.k.a. Revenge of the Gladiators, Roger Browne

- Revenge of the Barbarians (1960)

- Revenge of the Black Eagle (1951) directed by Riccardo Freda

- Revenge of the Conquered (1961) a.k.a. Drakut the Avenger

- Revenge of the Gladiators (1961) starring Mickey Hargitay

- Revenge of the Musketeers (1964) a.k.a. Dartagnan vs. the Three Musketeers, starring Fernando Lamas

- Revolt of the Barbarians (1964) directed by Guido Malatesta

- Revolt of the Mercenaries (1961)

- Revolt of the Praetorians (1964) a.k.a. The Invincible Warriors, starring Richard Harrison

- Revolt of the Seven (1964) a.k.a. The Spartan Gladiator, starring Helga Line

- Revolt of the Slaves, The (1960) Rhonda Fleming

- Robin Hood and the Pirates (1960) Lex Barker

- Roland the Mighty (1956) a.k.a. Orlando, directed by Pietro Francisci

- Rome Against Rome (1964) a.k.a. War of the Zombies

- Rome 1585 (1961) a.k.a. The Mercenaries, Debra Paget

- Rover, The (1967) a.k.a. The Adventurer, starring Anthony Quinn

- Sack of Rome, The (1953) a.k.a. The Barbarians, a.k.a. The Pagans

- Samson and Gideon (1965) Fernando Rey, Biblical film

- Sandokan Fights Back (1964) a.k.a. Sandokan to the Rescue, a.k.a. The Revenge of Sandokan

- Sandokan vs. the Leopard of Sarawak (1964) a.k.a. Throne of Vengeance

- Saracens, The (1965) a.k.a. The Devil's Pirate, a.k.a. The Flag of Death, starring Richard Harrison

- Saul and David (1964)

- Scheherazade (1963) starring Anna Karina

- Sea Pirate, The (1966) a.k.a. Thunder Over the Indian Ocean, a.k.a. Surcouf, Hero of the Seven Seas

- Secret Mark of D'Artagnan, The (1962)

- Secret Seven, The (1965) a.k.a. The Invincible Seven

- Seven from Thebes (1964)

- Seven Rebel Gladiators (1965) a.k.a. Seven Against All, starring Roger Browne

- Seven Revenges, The (1961) a.k.a. The Seven Challenges, a.k.a. Ivan the Conqueror, starring Ed Fury

- Seven Seas to Calais (1962) a.k.a. Sir Francis Drake, King of the Seven Seas, Rod Taylor

- Seven Slaves Against the World (1964) a.k.a. Seven Slaves Against Rome, starring Roger Browne and Gordon Mitchell

- Seven Tasks of Ali Baba, The (1962) a.k.a. Ali Baba and the Sacred Crown

- Seventh Sword, The (1962) Brett Halsey

- 79 A.D., the Destruction of Herculaneum (1962) Brad Harris

- Shadow of Zorro, The (1962)

- Sheba and the Gladiator (1959) a.k.a. The Sign of Rome, a.k.a. Sign of the Gladiator, Anita Ekberg

- Siege of Syracuse (1960) Tina Louise

- Simbad e il califfo di Bagdad (1973) directed by Pietro Francisci

- Sins of Rome (1953) a.k.a. Spartacus, directed by Riccardo Freda

- Slave Girls of Sheba (1963) starring Linda Cristal

- Slave of Rome (1960) starring Guy Madison

- Slave Queen of Babylon (1963) Yvonne Furneaux

- Slaves of Carthage, The (1956) a.k.a. The Sword and the Cross, Gianna Maria Canale (not to be confused with Mary Magdalene; see below)

- Sodom and Gomorrah (1962) Rosanna Podesta, U.S./Italian film shot in Italy, co-directed by Sergio Leone

- Son of Black Eagle (1968)

- Son of Captain Blood, The (1962)

- Son of Cleopatra, The (1965) Mark Damon

- Son of d'Artagnan (1950) directed by Riccardo Freda

- Son of El Cid, The (1965) a.k.a. 100 Horsemen, Mark Damon

- Son of the Red Corsair (1959) a.k.a. Son of the Red Pirate, Lex Barker

- Son of the Sheik (1961) a.k.a. Kerim, Son of the Sheik, starring Gordon Scott

- Spartacus and the Ten Gladiators (1964) a.k.a. Ten Invincible Gladiators, starring Dan Vadis

- Spartan Gladiator, The (1965) Tony Russel

- Story of Joseph and his Brethren, The (1961)

- Suleiman the Conqueror (1961)

- Sword and the Cross, The (1958) a.k.a. Mary Magdalene

- Sword in the Shadow, A (1961) starring Livio Lorenzon

- Sword of Damascus, The (1964) a.k.a. The Thief of Damascus

- Sword of El Cid, The (1962) a.k.a. The Daughters of El Cid

- Sword of Islam, The (1961)

- Sword of the Conqueror (1961) a.k.a. Rosamund and Alboino, Jack Palance

- Sword for the Empire, A (1965) a.k.a. Sword of the Empire

- Sword of the Rebellion, The (1964) a.k.a. The Rebel of Castelmonte

- Swordsman of Siena (1962) a.k.a. The Mercenary

- Sword of Vengeance (1961) a.k.a. La spada della vendetta

- Sword Without a Country (1961) a.k.a. Sword Without a Flag

- Tartars, The (1961) starring Victor Mature

- Taras Bulba, The Cossack (1963) a.k.a. Plains of Battle

- Taur, the Mighty (1963) a.k.a. Tor the Warrior, a.k.a. Taur, the King of Brute Force, starring Joe Robinson

- Temple of the White Elephant (1965) a.k.a. Sandok, the Giant of the Jungle, a.k.a. Sandok, the Maciste of the Jungle (not a Maciste film, however, in spite of the alternate title)

- Ten Gladiators, The (1963) starring Dan Vadis

- Terror of the Black Mask (1963) a.k.a. The Invincible Masked Rider

- Terror of the Red Mask (1960) starring Lex Barker

- Terror of the Steppes (1964) a.k.a. The Mighty Khan, Kirk Morris

- Tharus, Son of Attila (1962) a.k.a. Colossus and the Huns, Ricardo Montalban

- Theodora, Slave Empress (1954) directed by Riccardo Freda

- Thor and the Amazon Women (1963) starring Joe Robinson

- Three Hundred Spartans, The (1963) starring Richard Egan; U.S. film filmed in Greece using Italian screenwriters

- Three Swords for Rome (1965) starring Roger Browne

- Three Swords of Zorro, The (1963)

- Tiger of the Seven Seas (1962)

- Treasure of the Petrified Forest, The (1965) starring Gordon Mitchell

- Triumph of Robin Hood (1962) starring Samson Burke

- Triumph of the Ten Gladiators (1965) starring Dan Vadis

- Two Gladiators, The (1964) a.k.a. Fight or Die, starring Richard Harrison

- Tyrant of Castile, The (1964) starring Mark Damon

- Ulysses (1954) produced by Dino De Laurentiis, starring Kirk Douglas and Anthony Quinn

- Virgins of Rome, The (1961) a.k.a. Amazons of Rome

- Vulcan, Son of Jupiter (1962) a.k.a. Vulcan, Son of Jove, Gordon Mitchell, Richard Lloyd, Roger Browne

- War Goddess (1973) a.k.a. The Bare-Breasted Warriors, a.k.a. Le guerriere dal seno nudo, directed by Terence Young

- War Gods of Babylon (1962) a.k.a. The Seventh Thunderbolt, a.k.a. The Seven Glories of Assur

- Warrior and the Slave Girl, The (1958) a.k.a. The Revolt of the Gladiators, starring Gianna Maria Canale

- Warrior Empress, The (1960) a.k.a. Sappho, Venus of Lesbos, Kerwin Mathews, Tina Louise

- White Slave Ship (1961) directed by Silvio Amadio

- Women of Devil's Island (1962) starring Guy Madison

- Wonders of Aladdin, The (1961) starring Donald O'Connor

- Zorikan the Barbarian (1964) starring Dan Vadis

- Zorro (1975) Alain Delon

- Zorro and the Three Musketeers (1963) a.k.a. Mask of the Musketeers, starring Gordon Scott

- Zorro in the Court of England (1970) starring Spiros Focás

- Zorro at the Court of Spain (1962) a.k.a. The Masked Conqueror, George Ardisson

- Zorro of Monterrey (1971) a.k.a. El Zorro de Monterrey, Carlos Quiney

- Zorro, Rider of Vengeance (1971) Carlos Quiney

- Zorro's Last Adventure (1970) a.k.a. La última aventura del Zorro, Carlos Quiney

- Zorro the Avenger (1962) a.k.a. The Revenge of Zorro, Frank Latimore

- Zorro the Avenger (1969) a.k.a. El Zorro justiciero (1969) starring Fabio Testi

- Zorro the Fox (1968) a.k.a. El Zorro, George Ardisson

- Zorro, the Navarra Marquis (1969) Nino Vingelli

- Zorro the Rebel (1966) Howard Ross

- Zorro Against Maciste (1963) a.k.a. Samson and the Slave Queen (1963) starring Pierre Brice, Alan Steel

Gladiator films

Inspired by the success of Spartacus, there were a number of Italian peplums that heavily emphasized the gladiatorial arena in their plots, with it becoming almost a peplum subgenre in itself. One group of supermen known as "The Ten Gladiators" appeared in a trilogy, all three films starring Dan Vadis in the lead role.

- Alone Against Rome (1962) a.k.a. Vengeance of the Gladiators

- The Arena (1974) a.k.a. Naked Warriors, co-directed by Joe D'Amato, starring Pam Grier, Paul Muller and Rosalba Neri

- Challenge of the Gladiator (1965) starring Peter Lupus (a.k.a. Rock Stevens)

- Fabiola (1949) a.k.a. The Fighting Gladiator

- Gladiator of Rome (1962) a.k.a. Battle of the Gladiators, starring Gordon Scott

- Gladiators Seven (1962) a.k.a. The Seven Gladiators, starring Richard Harrison

- Invincible Gladiator, The (1961) Richard Harrison

- Last Gladiator, The (1963) a.k.a. Messalina Against the Son of Hercules

- Maciste, Gladiator of Sparta (1964) a.k.a. Terror of Rome Against the Son of Hercules

- Revenge of Spartacus, The (1965) a.k.a. Revenge of the Gladiators, starring Roger Browne

- Revenge of The Gladiators (1961) starring Mickey Hargitay

- Revolt of the Seven (1964) a.k.a. The Spartan Gladiator, starring Tony Russel and Helga Line

- Revolt of the Slaves (1961) Rhonda Fleming

- Seven Rebel Gladiators (1965) a.k.a. Seven Against All, starring Roger Browne

- Seven Slaves Against the World (1965) a.k.a. Seven Slaves Against Rome, a.k.a. The Strongest Slaves in the World, starring Roger Browne and Gordon Mitchell

- Sheba and the Gladiator (1959) a.k.a. The Sign of Rome, a.k.a. Sign of the Gladiator, Anita Ekberg

- Sins of Rome (1952) a.k.a. Spartacus, directed by Riccardo Freda

- Slave, The (1962) a.k.a. Son of Spartacus, Steve Reeves

- Spartacus and the Ten Gladiators (1964) a.k.a. Ten Invincible Gladiators, Dan Vadis

- Spartan Gladiator, The (1965) Tony Russel

- Ten Gladiators, The (1963) Dan Vadis

- Triumph of the Ten Gladiators (1965) Dan Vadis

- Two Gladiators, The (1964) a.k.a. Fight or Die, Richard Harrison

- Ursus, the Rebel Gladiator (1963) a.k.a. Rebel Gladiators, Dan Vadis

- Warrior and the Slave Girl, The (1958) a.k.a. The Revolt of the Gladiators, Gianna Maria Canale

Ancient Rome

- Brennus, Enemy of Rome (1964) a.k.a. Battle of the Valiant, Gordon Mitchell

- Caesar Against the Pirates (1962) Gordon Mitchell

- Caesar the Conqueror (1962) Cameron Mitchell, Rik Battaglia

- Carthage in Flames (1960) a.k.a. Cartagine in fiamme, directed by Carmine Gallone

- Centurion The (1962) a.k.a. The Conqueror of Corinth

- Colossus of Rhodes, The (1960) directed by Sergio Leone

- Constantine and the Cross (1960) a.k.a. Constantine the Great

- Coriolanus: Hero without a Country (1963) a.k.a. Thunder of Battle, Gordon Scott

- Diary of a Roman Virgin (1974) a.k.a. Livia, una vergine per l'impero romano, directed by Joe D'Amato (used stock footage from The Last Days of Pompeii (1959) and The Arena (1974))

- Duel of Champions (1961) a.k.a. Horatio and Curiazi, Alan Ladd

- Duel of the Titans (1962) a.k.a. Romulus and Remus, Steve Reeves, Gordon Scott

- Fall of Rome, The (1961) directed by Antonio Margheriti

- Fire Over Rome (1963)

- Giants of Rome (1963) directed by Antonio Margheriti, starring Richard Harrison

- Gold for the Caesars (1963) Jeffrey Hunter

- Hannibal (1959) Victor Mature

- Hero of Rome (1964) a.k.a. The Colossus of Rome, Gordon Scott

- Kampf um Rom (1968) a.k.a. The Last Roman, starring Laurence Harvey, Honor Blackman, Orson Welles

- Last Days of Pompeii (1959) Steve Reeves

- Massacre in the Black Forest (1967) Cameron Mitchell

- Messalina (1960)

- Nero and the Burning of Rome (1955) a.k.a. Nero and Messalina

- Quo Vadis (1951) assistant director Sergio Leone

- Rape of the Sabine Women, The (1961) Roger Moore

- Revenge of Spartacus, The (1965) Roger Browne

- Revenge of the Barbarians (1960)

- Revolt of the Praetorians (1965) Richard Harrison

- Rome Against Rome (1963) a.k.a. War of the Zombies

- The Secret Seven (1965) a.k.a. The Invincible Seven

- 79 A.D., the Destruction of Herculaneum (1962) Brad Harris

- Sheba and the Gladiator (1959) a.k.a. The Sign of Rome, a.k.a. Sign of the Gladiator, Anita Ekberg

- Sins of Rome (1952) a.k.a. Spartaco, directed by Riccardo Freda

- The Slave of Rome (1960) starring Guy Madison

- Slaves of Carthage, The (1956) a.k.a. The Sword and the Cross, Gianna Maria Canale (not to be confused with Mary Magdalene)

- Theodora, Slave Empress (1954) directed by Riccardo Freda

- Three Swords for Rome (1965) Roger Browne

- Virgins of Rome, The (1961) a.k.a. Amazons of Rome

Greek mythology

- The Avenger (1962) a.k.a. Legend of Aeneas, Steve Reeves

- Alexander The Great (1956) U.S. film with music score by Mario Nascimbene

- Antigone (1961) a.k.a. Rites for the Dead, a Greek production

- Bacchantes, The (1961)

- Battle of the Amazons (1973) a.k.a. Amazons: Women of Love and War, a.k.a. Beauty of the Barbarian (directed by Alfonso Brescia)

- The Colossus of Rhodes (1961) directed by Sergio Leone

- Conqueror of Atlantis (1965) starring Kirk Morris

- Damon and Pythias (1962) Guy Williams

- Fury of Achilles (1962) Gordon Mitchell

- Giant of Marathon (1959) (The Battle of Marathon) Steve Reeves

- Giants of Thessaly (1960) directed by Riccardo Freda

- Helen of Troy (1956) directed by Robert Wise

- Hercules Challenges Samson (1963) a.k.a. Hercules, Samson and Ulysses

- Lion of Thebes, The (1964) a.k.a. Helen of Troy, Mark Forest

- Mars, God of War (1962) a.k.a. Venus Against the Son of Hercules

- The Minotaur (1961) a.k.a. Theseus Against the Minotaur, a.k.a. The Warlord of Crete

- My Son, the Hero (1961) a.k.a. Arrivano i Titani, a.k.a. The Titans

- Odyssey, The (1968) Cyclops segment directed by Mario Bava; Samson Burke played Polyphemus the Cyclops

- Perseus the Invincible (1962) a.k.a. Medusa vs. the Son of Hercules

- Queen of the Amazons (1960) a.k.a. Colossus and the Amazon Queen

- Seven from Thebes (1964) André Lawrence

- Siege of Syracuse, The (1962) Tina Louise

- Treasure of the Petrified Forest (1965) Gordon Mitchell (the plot involves Amazons)

- Trojan Horse, The (1961) a.k.a. The Trojan War, Steve Reeves

- Ulysses (1954) starring Kirk Douglas and Anthony Quinn

- Vulcan, Son of Jupiter (1962) a.k.a. Vulcan, Son of Jove, Gordon Mitchell, Richard Lloyd, Roger Browne

- Warrior Empress, The (1960) a.k.a. Sappho, Venus of Lesbos, Kerwin Mathews, Tina Louise

Barbarian and Viking films

- Attack of the Normans (1962) a.k.a. The Normans, Cameron Mitchell

- Attila (1954) directed by Pietro Francisci, Anthony Quinn, Sophia Loren

- The Cossacks (1960)

- Defeat of the Barbarians (1962) a.k.a. King Manfred

- Dragon's Blood, The (1957)[25] a.k.a. Sigfrido, based on the legend of the Niebelungen, special effects by Carlo Rambaldi

- Erik the Conqueror (1961) a.k.a. The Invaders, directed by Mario Bava, starring Cameron Mitchell

- Fury of the Pagans (1960) a.k.a. Fury of the Barbarians

- Goliath and the Barbarians (1959) a.k.a. Terror of the Barbarians, Steve Reeves

- The Huns (1960) a.k.a. Queen of the Tartars

- Invasion 1700 (1962) a.k.a. With Iron and Fire, a.k.a. With Fire and Sword, a.k.a. Daggers of Blood

- King of the Vikings (1960) a.k.a. The Prince in Chains

- The Last of the Vikings (1961) starring Cameron Mitchell and Broderick Crawford

- Marco Polo (1962) Rory Calhoun

- Marco the Magnificent (1965) Anthony Quinn, Orson Welles

- Michel Strogoff (1956) a.k.a. Revolt of the Tartars

- The Mongols (1961) starring Jack Palance

- Revak the Rebel (1960) a.k.a. The Barbarians, Jack Palance

- Revolt of the Barbarians (1964) directed by Guido Malatesta

- Roland the Mighty (1956) directed by Pietro Francisci

- Saracens, The (1965) a.k.a. The Devil's Pirate, a.k.a. The Flag of Death

- The Seven Revenges (1961) a.k.a. The Seven Challenges, a.k.a. Ivan the Conqueror, starring Ed Fury

- Suleiman the Conqueror (1961)

- Sword of the Conqueror (1961) a.k.a. Rosamund and Alboino, Jack Palance

- Sword of the Empire (1964)

- Taras Bulba, The Cossack (1963) a.k.a. Plains of Battle

- The Tartars (1961) Victor Mature, Orson Welles

- Terror of the Steppes (1963) a.k.a. The Mighty Khan, starring Kirk Morris

- Tharus Son of Attila (1962) a.k.a. Colossus and the Huns, Ricardo Montalban

- Zorikan the Barbarian (1964) Dan Vadis

Swashbucklers / pirates

- Adventurer of Tortuga (1965) starring Guy Madison

- Adventures of Mandrin, The (1960) a.k.a. Captain Adventure

- Adventures of Scaramouche, The (1963) a.k.a. The Mask of Scaramouche, Gianna Maria Canale

- Arms of the Avenger (1963) a.k.a. The Devils of Spartivento, starring John Drew Barrymore

- At Sword's Edge (1952) dir. by Carlo Ludovico Bragaglia

- Attack of the Moors (1959) a.k.a. The Kings of France

- Avenger of the Seven Seas (1961) a.k.a. Executioner of the Seas, Richard Harrison

- Avenger of Venice, The (1963) directed by Riccardo Freda, starring Brett Halsey

- Balboa (Spanish, 1963) a.k.a. Conquistadors of the Pacific

- Beatrice Cenci (1956) directed by Riccardo Freda

- Beatrice Cenci (1969) directed by Lucio Fulci

- Behind the Mask of Zorro (1966) a.k.a. The Oath of Zorro, Tony Russel

- Black Archer, The (1959) Gerard Landry

- Black Devil, The (1957) Gerard Landry

- Black Duke, The (1963) Cameron Mitchell

- Black Eagle, The (1946) a.k.a. Return of the Black Eagle, directed by Riccardo Freda

- Black Lancers, The (1962) a.k.a. Charge of the Black Lancers, Mel Ferrer

- Captain from Toledo, The (1966)

- Captain of Iron, The (1962) a.k.a. Revenge of the Mercenaries, Barbara Steele

- Captain Phantom (1953)

- Captains of Adventure (1961) starring Paul Muller and Gerard Landry

- Caribbean Hawk, The (1963) Yvonne Monlaur

- Castillian, The (1963) Cesare Romero, U.S./Spanish co-production

- Catherine of Russia (1962) directed by Umberto Lenzi

- Cavalier in Devil's Castle (1959) a.k.a. Cavalier of Devil's Island

- Conqueror of Maracaibo, The (1961)

- The Count of Braggalone (1954) aka The Last Musketeer, starring Georges Marchal

- Count of Monte Cristo, The (1962) Louis Jourdan

- Devil Made a Woman, The (1959) a.k.a. A Girl Against Napoleon

- Devil's Cavaliers, The (1959) a.k.a. The Devil's Riders, Gianna Maria Canale

- Dick Turpin (1974) a Spanish production

- El Cid (1961) Sophia Loren, Charlton Heston, U.S./ Italian film shot in Italy

- Executioner of Venice, The (1963) Lex Barker, Guy Madison

- Fighting Musketeers, The (1961)

- Giant of the Evil Island (1965) a.k.a. Mystery of the Cursed Island, Peter Lupus

- Goliath and the Masked Rider (1964) a.k.a. Hercules and the Masked Rider, Alan Steel

- Guns of the Black Witch (1961) a.k.a. Terror of the Sea, Don Megowan

- Hawk of the Caribbean (1963)

- Invincible Swordsman, The (1963)

- The Iron Swordsman (1949) a.k.a. Count Ugolino, directed by Riccardo Freda

- Ivanhoe, the Norman Swordsman (1971) a.k.a. La spada normanna, directed by Roberto Mauri

- Knight of a Hundred Faces, The (1960) a.k.a. The Silver Knight, starring Lex Barker

- Knights of Terror (1963) a.k.a. Terror of the Red Capes, Tony Russel

- Knight Without a Country (1959) a.k.a. The Faceless Rider

- Lawless Mountain, The (1953) a.k.a. La montaña sin ley (stars Zorro)

- Lion of St. Mark, The (1964) Gordon Scott

- Mark of Zorro (1975) made in France, Monica Swinn

- Mark of Zorro (1976) George Hilton

- Masked Conqueror, The (1962)

- Mask of the Musketeers (1963) a.k.a. Zorro and the Three Musketeers, starring Gordon Scott

- Michael Strogoff (1956) a.k.a. Revolt of the Tartars

- Miracle of the Wolves (1961) a.k.a. Blood on his Sword, starring Jean Marais

- Morgan, the Pirate (1960) Steve Reeves

- Musketeers of the Sea (1960)

- Mysterious Rider, The (1948) directed by Riccardo Freda[26]

- Mysterious Swordsman, The (1956) starred Gerard Landry

- Nephews of Zorro, The (1968) Italian comedy with Franco and Ciccio

- Night of the Great Attack (1961) a.k.a. Revenge of the Borgias

- Night They Killed Rasputin, The (1960) a.k.a. The Last Czar

- Nights of Lucretia Borgia, The (1959)

- Pirate and the Slave Girl, The (1959) Lex Barker

- Pirate of the Black Hawk, The (1958)

- Pirate of the Half Moon (1957)

- Pirates of the Coast (1960) Lex Barker

- Prince with the Red Mask, The (1955) a.k.a. The Red Eagle

- Prisoner of the Iron Mask, The (1961) a.k.a. The Revenge of the Iron Mask

- Pugni, Pirati e Karatè (1973) a.k.a. Fists, Pirates and Karate, directed by Joe D'Amato, starring Richard Harrison (a 1970s Italian spoof of pirate movies)

- Queen of the Pirates (1961) a.k.a. The Venus of the Pirates, Gianna Maria Canale

- Queen of the Seas (1961) directed by Umberto Lenzi

- Rage of the Buccaneers (1961) a.k.a. Gordon, The Black Pirate, starring Vincent Price

- Red Cloak, The (1955) Bruce Cabot

- Revenge of Ivanhoe, The (1965) Rik Battaglia

- Revenge of the Black Eagle (1951) directed by Riccardo Freda

- Revenge of the Musketeers (1963) a.k.a. Dartagnan vs. the Three Musketeers, Fernando Lamas

- Revenge of Spartacus, The (1965) Roger Browne

- Revolt of the Mercenaries (1961)

- Robin Hood and the Pirates (1960) Lex Barker

- Roland, the Mighty (1956) directed by Pietro Francisci

- Rome 1585 (1961) a.k.a. The Mercenaries, Debra Paget, set in the 1500s

- Rover, The (1967) a.k.a. The Adventurer, starring Anthony Quinn

- The Sack of Rome (1953) a.k.a. The Barbarians, a.k.a. The Pagans (set in the 1500s)

- Samson vs. the Black Pirate (1963) a.k.a. Hercules and the Black Pirate, Alan Steel

- Samson vs. the Pirates (1963) a.k.a. Samson and the Sea Beast, Kirk Morris

- Sandokan Fights Back (1964) a.k.a. Sandokan to the Rescue, a.k.a. The Revenge of Sandokan, Guy Madison

- Sandokan the Great (1964) a.k.a. Sandokan, the Tiger of Mompracem, Steve Reeves

- Sandokan, the Pirate of Malaysia (1964) a.k.a. Pirates of Malaysia, a.k.a. Pirates of the Seven Seas, Steve Reeves, directed by Umberto Lenzi

- Sandokan vs. the Leopard of Sarawak (1964) a.k.a. Throne of Vengeance, Guy Madison

- Saracens, The (1965) a.k.a. The Devil's Pirate, a.k.a. The Flag of Death, starring Richard Harrison

- Sea Pirate, The (1966) a.k.a. Thunder Over the Indian Ocean, a.k.a. Surcouf, Hero of the Seven Seas

- Secret Mark of D'artagnan, The (1962)

- Seven Seas to Calais (1961) a.k.a. Sir Francis Drake, King of the Seven Seas, Rod Taylor

- Seventh Sword, The (1960) Brett Halsey

- Shadow of Zorro (1962) Frank Latimore

- Sign of Zorro, The (1952)

- Sign of Zorro (1963) a.k.a. Duel at the Rio Grande, Sean Flynn

- Son of Black Eagle (1968)

- Son of Captain Blood (1962)

- Son of d'Artagnan (1950) directed by Riccardo Freda

- Son of El Cid, The (1965) Mark Damon

- Son of the Red Corsair (1959) a.k.a. Son of the Red Pirate, Lex Barker

- Son of Zorro (1973) Alberto Dell'Acqua

- Sword in the Shadow, A (1961) starring Livio Lorenzon

- Sword of Rebellion, The (1964) a.k.a. The Rebel of Castelmonte

- Sword of Vengeance (1961) a.k.a. La spada della vendetta

- Swordsman of Siena, The (1961) a.k.a. The Mercenary

- Sword Without a Country (1960) a.k.a. Sword Without a Flag

- Taras Bulba, The Cossack (1963) a.k.a. Plains of Battle

- Terror of the Black Mask (1963) a.k.a. The Invincible Masked Rider

- Terror of the Red Mask (1960) Lex Barker

- Three Swords of Zorro, The (1963) a.k.a. The Sword of Zorro, Guy Stockwell

- Tiger of the Seven Seas (1963)

- Triumph of Robin Hood (1962) starring Samson Burke

- Tyrant of Castile, The (1964) Mark Damon

- White Slave Ship (1961) directed by Silvio Amadio

- The White Warrior (1959) a.k.a. Hadji Murad, the White Devil, Steve Reeves

- Women of Devil's Island (1962) starring Guy Madison

- Zorro (1968) a.k.a. El Zorro, a.k.a. Zorro the Fox, George Ardisson

- Zorro (1975) Alain Delon

- Zorro and the Three Musketeers (1963) Gordon Scott

- Zorro at the Court of England (1969) Spiros Focás as Zorro

- Zorro at the Court of Spain (1962) a.k.a. The Masked Conqueror, Georgio Ardisson

- Zorro of Monterrey (1971) a.k.a. El Zorro de Monterrey, Carlos Quiney

- Zorro, Rider of Vengeance (1971) Carlos Quiney

- Zorro's Last Adventure (1970) a.k.a. La última aventura del Zorro, Carlos Quiney

- Zorro the Avenger (1962) a.k.a. The Revenge of Zorro, Frank Latimore

- Zorro the Avenger (1969) a.k.a. El Zorro justiciero (1969) Fabio Testi

- Zorro, the Navarra Marquis (1969) Nadir Moretti as Zorro

- Zorro the Rebel (1966) Howard Ross

- Zorro Against Maciste (1963) a.k.a. Samson and the Slave Queen (1963) starring Pierre Brice, Alan Steel

Biblical

- Barabbas (1961) Dino de Laurentiis, Anthony Quinn, filmed in Italy

- Bible, The (1966) Dino de Laurentiis, John Huston, filmed in Italy

- David and Goliath (1960) Orson Welles

- Desert Desperadoes (1956) plot involves King Herod

- Esther and the King (1961) Joan Collins, Richard Egan

- Head of a Tyrant, The (1959)

- Herod the Great (1958) Edmund Purdom

- Jacob, the Man Who Fought with God (1964) Giorgio Cerioni

- Mighty Crusaders, The (1957) a.k.a. Jerusalem Set Free, Gianna Maria Canale

- Moses the Lawgiver (1973) aka Moses in Egypt, Burt Lancaster, Anthony Quayle (6-hour made-for-TV Italian/British co-production) also released theatrically

- Old Testament, The (1962) Brad Harris

- Pontius Pilate (1962) Jean Marais

- The Queen of Sheba (1952), directed by Pietro Francisci

- Samson and Gideon (1965) Fernando Rey

- Saul and David (1963) Gianni Garko

- Sodom and Gomorrah (1962) Rosanna Podesta, U.S./Italian film shot in Italy

- Story of Joseph and his Brethren, The (1960)

- Sword and the Cross, The (1958) a.k.a. Mary Magdalene, Gianna Maria Canale

Ancient Egypt

- Cleopatra's Daughter (1960) starring Debra Paget

- Legions of the Nile (1959) starring Linda Cristal

- Pharaoh's Woman, The (1960) with John Drew Barrymore

- Queen for Caesar, A (1962) Gordon Scott

- Queen of the Nile (1961) a.k.a. Nefertiti, Vincent Price

- Son of Cleopatra (1964) Mark Damon

Babylon / the Middle East

- Ali Baba and the Seven Saracens (1962) a.k.a. Sinbad Against the 7 Saracens,[27] starring Gordon Mitchell

- Anthar, The Invincible (1964) a.k.a. Devil of the Desert Against the Son of Hercules, starring Kirk Morris, directed by Antonio Margheriti

- Desert Warrior (1957) a.k.a. The Desert Lovers, Ricardo Montalban

- Falcon of the Desert (1965) a.k.a. The Magnificent Challenge, starring Kirk Morris

- Golden Arrow, The (1962) directed by Antonio Margheriti

- Goliath at the Conquest of Baghdad (1964) a.k.a. Goliath at the Conquest of Damascus, Peter Lupus

- Goliath and the Rebel Slave (1963) a.k.a. The Tyrant of Lydia vs. The Son of Hercules, Gordon Scott

- Goliath and the Sins of Babylon (1963) a.k.a. Maciste, the World's Greatest Hero, Mark Forest

- Hercules and the Tyrants of Babylon (1964)

- Hero of Babylon (1963) a.k.a. The Beast of Babylon vs. the Son of Hercules, Gordon Scott

- Kindar, the Invulnerable (1965) Mark Forest, Rosalba Neri[28]

- Missione sabbie roventi (Mission Burning Sands) (1966) starring Renato Rossini, directed by Alfonso Brescia

- Red Sheik, The (1962)

- Scheherazade (1963) starring Anna Karina

- Seven Tasks of Ali Baba, The (1962) a.k.a. Ali Baba and the Sacred Crown, starring Richard Lloyd

- Slave Girls of Sheba (1963) starring Linda Cristal

- Slave Queen of Babylon (1962) Yvonne Furneaux

- Son of the Sheik (1961) a.k.a. Kerim, Son of the Sheik, starring Gordon Scott

- Sword of Damascus, The (1964) a.k.a. The Thief of Damascus

- Sword of Islam, The (1961) a.k.a. Love and Faith; an Italian/ Egyptian co-production

- Thief of Baghdad, The (1961) Steve Reeves

- War Gods of Babylon (1962) a.k.a. The Seventh Thunderbolt

- Wonders of Aladdin, The (1961) Donald O'Connor

The second peplum wave: the 1980s

After the peplum gave way to the spaghetti Western and Eurospy films in 1965, the genre lay dormant for close to 20 years. Then in 1982, the box-office successes of Jean-Jacques Annaud's Quest for Fire (1981), Arnold Schwarzenegger's Conan the Barbarian (1982) and Clash of the Titans (1981 film) (1981) spurred a second renaissance of sword and sorcery Italian pepla in the five years immediately following. Most of these films had low budgets, focusing more on barbarians and pirates so as to avoid the need for expensive Greco-Roman sets. The filmmakers tried to compensate for their shortcomings with the addition of some graphic gore and nudity. Many of these 1980s entries were helmed by noted Italian horror film directors (Joe D'Amato, Lucio Fulci, Luigi Cozzi, etc.) and many featured actors Lou Ferrigno, Miles O'Keeffe and Sabrina Siani. Here is a list of the 1980s pepla:

- Adam and Eve (1983) a.k.a. Adamo ed Eva, la prima storia d'amore, contains stock footage from One Million Years B.C. (1966)

- Ator, the Fighting Eagle (1983) a.k.a. Ator the Invincible, starring Miles O'Keeffe and Sabrina Siani, directed by Joe D'Amato

- Ator 2: The Blade Master (1985) a.k.a. Cave Dwellers, starring Miles O'Keefe, directed by Joe D'Amato