Germany–Soviet Union relations, 1918–1941 (redirect from Hitler-Stalin alliance)loaded than the issue of the policies of the Soviet Union under Joseph Stalin towards Nazi Germany between the Nazi seizure of power and the German invasion...112 KB (14,235 words) - 13:25, 15 May 2023"collective farm". Stalin began to push for the collectivization of farms, claiming that economies of scale would help alleviate grain shortages, and seeking...22 KB (2,952 words) - 17:40, 11 May 2023Russe. 38 (1): 127–162. doi:10.3406/cmr.1997.2486. Robert Gellately. Lenin, Stalin, and Hitler: The Age of Social Catastrophe Archived May 5, 2016, at the...30 KB (1,551 words) - 22:57, 23 March 2023Red Famine (redirect from Red Famine: Stalin's War on Ukraine)Red Famine: Stalin's War on Ukraine is a 2017 non-fiction book by Anne Applebaum, focusing on the history of the Holodomor. The book won the Lionel Gelber...8 KB (793 words) - 06:45, 19 April 2023

Germany–Soviet Union relations, 1918–1941 (redirect from Hitler-Stalin alliance)loaded than the issue of the policies of the Soviet Union under Joseph Stalin towards Nazi Germany between the Nazi seizure of power and the German invasion...112 KB (14,235 words) - 13:25, 15 May 2023"collective farm". Stalin began to push for the collectivization of farms, claiming that economies of scale would help alleviate grain shortages, and seeking...22 KB (2,952 words) - 17:40, 11 May 2023Russe. 38 (1): 127–162. doi:10.3406/cmr.1997.2486. Robert Gellately. Lenin, Stalin, and Hitler: The Age of Social Catastrophe Archived May 5, 2016, at the...30 KB (1,551 words) - 22:57, 23 March 2023Red Famine (redirect from Red Famine: Stalin's War on Ukraine)Red Famine: Stalin's War on Ukraine is a 2017 non-fiction book by Anne Applebaum, focusing on the history of the Holodomor. The book won the Lionel Gelber...8 KB (793 words) - 06:45, 19 April 2023

https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?limit=20&offset=40&profile=default&search=stalin+grain&title=Special:Search&ns0=1

political repression and for carrying out the Great Purge under Joseph Stalin. It was led by Genrikh Yagoda, Nikolai Yezhov, and Lavrentiy Beria. The...44 KB (5,001 words) - 15:44, 6 May 2023

political repression and for carrying out the Great Purge under Joseph Stalin. It was led by Genrikh Yagoda, Nikolai Yezhov, and Lavrentiy Beria. The...44 KB (5,001 words) - 15:44, 6 May 2023 Sino-Soviet split (category Stalinism)warfare. In 1956, CPSU first secretary Nikita Khrushchev denounced Stalin and Stalinism in the speech On the Cult of Personality and its Consequences and...83 KB (9,490 words) - 14:39, 9 May 2023

Sino-Soviet split (category Stalinism)warfare. In 1956, CPSU first secretary Nikita Khrushchev denounced Stalin and Stalinism in the speech On the Cult of Personality and its Consequences and...83 KB (9,490 words) - 14:39, 9 May 2023- sparrow populations (which disrupted the ecosystem); over-reporting of grain production; and ordering millions of farmers to switch to iron and steel...89 KB (10,007 words) - 15:24, 14 May 2023

Cold War (section Cominform and the Tito–Stalin Split)Gerhard (2008). Stalin and the Cold War in Europe. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-7425-5542-6. Wood, Alan (2005). Stalin and Stalinism. ISBN 978-0-415-30731-4...328 KB (35,646 words) - 02:43, 15 May 2023

Cold War (section Cominform and the Tito–Stalin Split)Gerhard (2008). Stalin and the Cold War in Europe. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-7425-5542-6. Wood, Alan (2005). Stalin and Stalinism. ISBN 978-0-415-30731-4...328 KB (35,646 words) - 02:43, 15 May 2023 under the monitoring of the NKVD). In 1929, the government led by Josef Stalin designated some regions (known as districts) of Western Siberia as locations...24 KB (2,546 words) - 11:41, 14 May 2023

under the monitoring of the NKVD). In 1929, the government led by Josef Stalin designated some regions (known as districts) of Western Siberia as locations...24 KB (2,546 words) - 11:41, 14 May 2023- sparrow populations (which disrupted the ecosystem); over-reporting of grain production; and ordering millions of farmers to switch to iron and steel...89 KB (10,007 words) - 15:24, 14 May 2023

Marshall Plan (section Rejection by Stalin)Germany, Poland, etc.) from accepting. Secretary Marshall became convinced Stalin had no interest in helping restore economic health in Western Europe. President...123 KB (14,967 words) - 21:33, 6 May 2023two countries and presented a plan to the Soviets on December 1, 1938. Stalin, however, was not willing to sell his increasingly strong economic bargaining...36 KB (4,499 words) - 15:52, 21 April 2023

Marshall Plan (section Rejection by Stalin)Germany, Poland, etc.) from accepting. Secretary Marshall became convinced Stalin had no interest in helping restore economic health in Western Europe. President...123 KB (14,967 words) - 21:33, 6 May 2023two countries and presented a plan to the Soviets on December 1, 1938. Stalin, however, was not willing to sell his increasingly strong economic bargaining...36 KB (4,499 words) - 15:52, 21 April 2023- Authoritarian socialism (category Stalinism)as the "Stalin of the Caribbean" and the "tropical Stalin", respectively. According to The Daily Beast, Maduro has embraced the "tropical Stalin" moniker...304 KB (35,531 words) - 21:31, 6 May 2023

- Comintern in 1935. Although the term “Third Period” is closely associated with Stalin, it was first coined by Bukharin in 1926, at the Seventh Plenum of the ECCI...16 KB (2,097 words) - 23:41, 6 December 2022

- the socialist economy, by any means necessary. The aim was to requisition grain, cattle and horses, recruit young people to the army, and punish villages...85 KB (11,262 words) - 06:41, 19 May 2023

Russification of Ukraine (section Joseph Stalin)Holodomor, Stalin attacked Mykola Skrypnyk for non-Bolshevik conduct of Ukrainization and blamed resistance to forced collectivization and grain requisitions...112 KB (15,856 words) - 06:21, 16 April 2023

Russification of Ukraine (section Joseph Stalin)Holodomor, Stalin attacked Mykola Skrypnyk for non-Bolshevik conduct of Ukrainization and blamed resistance to forced collectivization and grain requisitions...112 KB (15,856 words) - 06:21, 16 April 2023

changed dramatically in the 1930s–1940s under the leadership of Joseph Stalin (despite his own Georgian ethnic roots) with the advent of a repressive...40 KB (4,062 words) - 01:14, 20 April 2023widescale theft of Ukrainian grain was continuing and involved both private companies and Russian state operatives. Some of the stolen grain is laundered...5 KB (396 words) - 23:14, 27 March 2023

changed dramatically in the 1930s–1940s under the leadership of Joseph Stalin (despite his own Georgian ethnic roots) with the advent of a repressive...40 KB (4,062 words) - 01:14, 20 April 2023widescale theft of Ukrainian grain was continuing and involved both private companies and Russian state operatives. Some of the stolen grain is laundered...5 KB (396 words) - 23:14, 27 March 2023 Sand (redirect from Sand-grain)particles. Sand has various compositions but is defined by its grain size. Sand grains are smaller than gravel and coarser than silt. Sand can also refer...32 KB (3,860 words) - 13:58, 10 May 2023

Sand (redirect from Sand-grain)particles. Sand has various compositions but is defined by its grain size. Sand grains are smaller than gravel and coarser than silt. Sand can also refer...32 KB (3,860 words) - 13:58, 10 May 2023 Food storage (section Grain)practical grain storage uses closed-top #10 metal cans). Storage in grain sacks is ineffective; mold and pests destroy a 25 kg cloth sack of grain in a year...21 KB (2,632 words) - 07:36, 12 April 20231920s Kloran, setting out KKK terms and traditions. Like many KKK terms, this is a portmanteau term, formed from Klan and Koran.

Food storage (section Grain)practical grain storage uses closed-top #10 metal cans). Storage in grain sacks is ineffective; mold and pests destroy a 25 kg cloth sack of grain in a year...21 KB (2,632 words) - 07:36, 12 April 20231920s Kloran, setting out KKK terms and traditions. Like many KKK terms, this is a portmanteau term, formed from Klan and Koran.Ku Klux Klan (KKK) nomenclature has evolved over the order's nearly 160 years of existence. The titles and designations were first laid out in the original Klan's prescripts of 1867 and 1868, then revamped with William J. Simmons's Kloran of 1916. Subsequent Klans have made various modifications.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ku_Klux_Klan_titles_and_vocabulary

Dekulakization (Russian: раскулачивание, raskulachivanie; Ukrainian: розкуркулення, rozkurkulennia) was the Soviet campaign of political repressions, including arrests, deportations, or executions of millions of kulaks (prosperous peasants) and their families. Redistribution of farmland started in 1917 and lasted until 1933, but was most active in the 1929–1932 period of the first five-year plan. To facilitate the expropriations of farmland, the Soviet government announced the "liquidation of the kulaks as a class" on 27 December 1929, portraying kulaks as class enemies of the Soviet Union.

More than 1.8 million peasants were deported in 1930–1931.[3][4][5] The campaign had the stated purpose of fighting counter-revolution and of building socialism in the countryside. This policy, carried out simultaneously with collectivization in the Soviet Union, effectively brought all agriculture and all the labourers in Soviet Russia under state control.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dekulakization

The terms enemy of the people and enemy of the nation are designations for the political opponents and for the social-class opponents of the power group within a larger social unit, who, thus identified, can be subjected to political repression.[1] In political praxis, the term enemy of the people implies that political opposition to the ruling power group renders the people in opposition into enemies acting against the interests of the greater social unit, e.g. the political party, society, the nation, etc.

In the 20th century, the politics of the Soviet Union (1922–1991) much featured the term enemy of the people to discredit any opposition, especially during the régime of Stalin (r. 1924–1953), when it was often applied to Trotsky.[2][3] In the 21st century, the former U.S. president Donald Trump (r. 2017–2021) regularly used the enemy of the people term against critical politicians and journalists.[4][5]

Like the term enemy of the state, the term enemy of the people originated and derives from the Latin: hostis publicus, a public enemy of the Roman Empire. In literature, the term enemy of the people features in the title of the stageplay An Enemy of the People (1882), by Henrik Ibsen, and is a theme in the stageplay Coriolanus (1605), by William Shakespeare.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Enemy_of_the_people

A counter-revolutionary or an anti-revolutionary is anyone who opposes or resists a revolution, particularly one who acts after a revolution in order to try to overturn it or reverse its course, in full or in part.[1][2] The adjective "counter-revolutionary" pertains to movements that would restore the state of affairs, or the principles, that prevailed during a prerevolutionary era.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Counter-revolutionary

Classicide

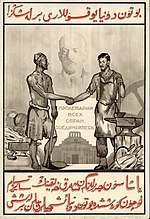

Another 1930s Soviet propaganda poster stating: "Kick kulaks from kolkhozes".In February 1928, the Pravda newspaper published for the first time materials that claimed to expose the kulaks; they described widespread domination by the rich peasantry in the countryside and invasion by kulaks of Communist party cells.[15] Expropriation of grain stocks from kulaks and middle-class peasants was called a "temporary emergency measure"; temporary emergency measures turned into a policy of "eliminating the kulaks as a class" by the 1930s.[15] Sociologist Michael Mann described the Soviet attempt to collectivize and liquidate perceived class enemies as fitting his proposed category of classicide.[16]

The party's appeal to the policy of eliminating the kulaks as a class had been formulated by Stalin, who stated: "In order to oust the kulaks as a class, the resistance of this class must be smashed in open battle and it must be deprived of the productive sources of its existence and development (free use of land, instruments of production, land-renting, right to hire labour, etc.). That is a turn towards the policy of eliminating the kulaks as a class. Without it, talk about ousting the kulaks as a class is empty prattle, acceptable and profitable only to the Right deviators."[17]

In 1928, the Right Opposition of the All-Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) was still trying to support the prosperous peasantry and soften the struggle against the kulaks. In particular, Alexei Rykov, criticizing the policy of dekulakization and "methods of war communism", declared that an attack on the kulaks should be carried out but not by methods of so-called dekulakization. He argued against taking action against individual farming in the village, the productivity of which was two times lower than in European countries. He believed that the most important task of the party was the development of the individual farming of peasants with the help of the government.[18]

The requisition of grains from wealthy peasants (kulak) during the forced collectivization in Timashyovsky District, Kuban, Soviet Union, 1933The government increasingly noticed an open and resolute protest among the poor against the well-to-do middle peasants.[19] The growing discontent of the poor peasants was reinforced by the famine in the countryside. The Bolsheviks preferred to blame the "rural counterrevolution" of the kulaks, intending to aggravate the attitude of the people towards the party: "We must repulse the kulak ideology coming in the letters from the village. The main advantage of the kulak is bread embarrassments." Red Army peasants sent letters supporting anti-kulak ideology: "The kulaks are the furious enemies of socialism. We must destroy them, don't take them to the kolkhoz, you must take away their property, their inventory." The letter of the Red Army soldier of the 28th Artillery Regiment became widely known: "The last bread is taken away, the Red Army family is not considered. Although you are my dad, I do not believe you. I'm glad that you had a good lesson. Sell bread, carry surplus – this is my last word."[20][21]

The official goal of kulak liquidation came without precise instructions, and encouraged local leaders to take radical action, which resulted in physical elimination. The campaign to liquidate the kulaks as a class constituted the main part of Stalin's social engineering policies in the early 1930s.[22]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dekulakization

The "liquidation of kulaks as a class" was the name of a Soviet policy enforced in 1930–1931 for forced, uncompensated alienation of property (expropriation) from portions of the peasantry and isolation of victims from such actions by way of their forceful deportation from their place of residence. The official goal of kulak liquidation came without precise instructions, and encouraged local leaders to take radical action, which resulted in physical elimination. The campaign to liquidate the kulaks as a class constituted the main part of Stalin's social engineering policies in the early 1930s.

Liquidation was a term used to describe a Soviet government policy of eradicating political adversaries, intellectuals, and rich persons. The Cheka, the secret police of the Soviet Union, carried out this program through arrests, executions, and other types of repression. Early in the 1920s, a liquidation effort was launched, and it lasted the entire decade.

In the Soviet Union, the term "liquidation" referred to a strategy of removing the Soviet government's adversaries, such as political rivals, intellectuals, and affluent people. The New Economic Policy (NEP), which was implemented by the Soviet secret police known as the Cheka, gave rise to the phrase "liquidation" in the early 1920s (16).

The liquidation campaign was directed at those who were thought to pose a threat to the Soviet government's attempt to consolidate its control, such as former Tsarist regime members, bourgeois intellectuals, and other deemed adversaries of the state. The liquidation campaign, which included arrests, executions, and other acts of repression, was part of a larger initiative to quell dissent and solidify the Soviet Communist Party's power. (1)

The liquidation campaign was largely focused on the political opponents of the Bolshevik government in the early years of the Soviet Union. The campaign's objectives, however, changed in the late 1920s to include perceived adversaries of the Soviet economy, such as the so-called "kulaks" or prosperous peasant farmers. The drive to eliminate the kulaks was a component of a larger collectivization strategy that attempted to centralize agricultural output under state control.

The liquidation campaign, which lasted through the 1920s and the beginning of the 1930s, was a crucial component of the Soviet Union's endeavor to achieve complete control over all facets of society. Although it is difficult to assess the scope of the campaign and the number of casualties, historians estimate that tens of thousands of individuals were put to death or imprisoned during this time.

The Soviet government targeted the so-called "kulaks" or wealthy peasant farmers, who were viewed as a threat to the collectivization of agriculture, during the most intense era of liquidation, which took place in the late 1920s and early 1930s. Millions of kulaks and their families were deported to remote regions of the Soviet Union as a result of the liquidation campaign against the kulaks, which also drove the collectivization of agriculture. An estimated 5 million people died as a result of this strategy, either through starvation, disease, or violence.

The Soviet authorities targeted a number of additional groups during the liquidation campaign in addition to the kulaks, including former Tsarist regime members, bourgeois intellectuals, and other organizations seen as state adversaries. Depending on the objective and the time period, the campaign's scope and the number of victims varied, but it is obvious that the liquidation campaign was a harsh and repressive measure that resulted in considerable suffering and death.

The program of removing opponents of the Soviet leadership, such as political rivals, intellectuals, and affluent people, was referred to as "liquidation" by the Soviet authorities. The word is an English translation of the Russian verb "likvidirovat," which meaning "to liquidate" or "to eliminate." The phrase was not specifically applied to Soviet politics in its earlier usage; rather, it referred to the act of removing barriers or resolving issues. However, the phrase came to be linked with the oppressive and murderous practices of the Soviet secret police, known as the Cheka, in the setting of the Soviet Union.

Effects of Liquidation in the Soviet Union

- Political purges: The Soviet government targeted several groups during the 1930s, including former Communist Party members, academics, and other so-called enemies of the state. Millions of individuals were imprisoned, subjected to torture, and executed as a result of these purges. (8)

- Industrialization: The government adopted a strategy of "liquidating" small-scale businesses in favor of sizable, state-run factories. The economy was significantly impacted by this, and major industrial hubs like Magnitogorsk and Norilsk were built as a result.

- Agriculture: The forced collectivization of farms and elimination of affluent farmers (kulaks), who were regarded as a threat to the socialist state, were referred to as "liquidation" in the context of agriculture. Significant damage was done to the agricultural industry as a consequence, and many people suffered, especially in Ukraine. (8)

- Social and cultural impact: Liquidation had an effect that transcended solely the political and economic spheres. Soviet society and culture were profoundly affected by the purges of the 1930s and other campaigns, which resulted in widespread fear, mistrust, and trauma. The media, the arts, and education were all significantly impacted by the government's attempts to influence and shape public opinion. (8).

The Soviet Union's liquidation had a wide-ranging effect and serious repercussions for both the nation and its citizens. In Russia and other former Soviet governments, the consequences of these policies are still felt today.

See also

- Collectivization in the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic

- Committees of Poor Peasants

- Decossackization

- Population transfer in the Soviet Union

- Holodomor

- Involuntary settlements in the Soviet Union

- Land reform in North Vietnam

- Podkulachnik

- Red Terror

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dekulakization

De-Cossackization (Russian: Расказачивание, Raskazachivaniye) was the Bolshevik policy of systematic repressions against Cossacks of the Russian Empire, especially of the Don and the Kuban, between 1919 and 1933 aimed at the elimination of the Cossacks as a distinct collectivity by exterminating the Cossack elite, coercing all other Cossacks into compliance and eliminating Cossack distinctness.[1] The campaign began in March 1919 in response to growing Cossack insurgency.[1] According to Nicolas Werth, one of the authors of The Black Book of Communism, Soviet leaders deciding to "eliminate, exterminate, and deport the population of a whole territory", which they had taken to calling the "Soviet Vendée".[2] The de-Cossackization is sometimes described as a genocide of the Cossacks,[3][4][5][6][7] although this view is disputed,[8] with some historians asserting that this label is an exaggeration.[9] The process has been described by scholar Peter Holquist as part of a "ruthless" and "radical attempt to eliminate undesirable social groups" that showed the Soviet regime's "dedication to social engineering".[10][9] Throughout this period, the policy underwent significant modifications, which resulted in the "normalization" of Cossacks as a component part of Soviet society.[9]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/De-Cossackization

Podkulachnik (Russian: Подкулачник, lit. 'person under the kulaks'; also translated as "sub-kulak" or "kulak henchman") was a political label used in the Soviet Union in the 1920s and 1930s to brand people considered traitors to the Soviet Government.

Podkulachnik is considered by many to be a Stalinist neologism from the late 1920s.[1] After the Russian Revolution, the Kulaks - relatively affluent and well-endowed peasants - were persecuted by the Soviet Government as class enemies of the poor, and hence enemies of the Revolution itself.

In Hungary under Mátyás Rákosi, a Podkulachnik was called Kulákbérenc, meaning Kulak Hessian.[citation needed]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Podkulachnik

Category:Property crimes

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Property crimes.

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Property crimes.Subcategories

This category has the following 12 subcategories, out of 12 total.

A

Acts of sabotage (2 C, 29 P)Animal theft (7 P)- Arson (10 C, 5 P)

C

- Commercial crimes (10 C, 54 P)

E

Embezzlement (1 C, 15 P)- Extortion (7 C, 29 P)

F

Financial crimes (10 C, 26 P)- Fraud (35 C, 144 P)

L

- Looting (8 C, 126 P)

T

- Theft (18 C, 89 P)

U

- Usury (8 P)

V

- Vandalism (6 C, 38 P)

Pages in category "Property crimes"

The following 36 pages are in this category, out of 36 total. This list may not reflect recent changes.

U

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Property_crimesArticles relating to usury, the practice of making unethical or immoral monetary loans that unfairly enrich the lender. The term may be used in a moral sense—condemning, taking advantage of others' misfortunes—or in a legal sense, where an interest rate is charged in excess of the maximum rate that is allowed by law. A loan may be considered usurious because of excessive or abusive interest rates or other factors defined by a nation's laws. Someone who practices usury can be called an usurer, but in contemporary English may be called a loan shark.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Usury

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Commercial_crimes

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Acts_of_sabotage

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Train_wrecks_caused_by_sabotage

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Theft_of_government_property

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/kuklas-peasants-americans-caucasians-varis-vars-humans-lowequity-infgen-stochtrafam-trafficking-human-product-etc.

No comments:

Post a Comment