This connotation may be connected with a popular false etymology explaining "innocent" as meaning "not knowing" (Latin noscere (To know, learn)). The actual etymology is from general negation prefix in- and the Latin nocere, "to harm".

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Innocence

A false etymology (fake etymology, popular etymology, etymythology,[1] pseudo-etymology, or par(a)etymology) is a popular but false belief about the origin or derivation of a specific word. It is sometimes called a folk etymology, but this is also a technical term in linguistics.

Such etymologies often have the feel of urban legends and can be more colorful and fanciful than the typical etymologies found in dictionaries, often involving stories of unusual practices in particular subcultures (e.g. Oxford students from non-noble families being supposedly forced to write sine nobilitate by their name, soon abbreviated to s.nob., hence the word snob).[2][3] Many recent examples are "backronyms" (acronyms made up to explain a term), such as posh for "port outward, starboard homeward".

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/False_etymology

Folk etymology (also known as popular etymology, analogical reformation, reanalysis, morphological reanalysis or etymological reinterpretation)[1] is a change in a word or phrase resulting from the replacement of an unfamiliar form by a more familiar one.[2][3][4] The form or the meaning of an archaic, foreign, or otherwise unfamiliar word is reinterpreted as resembling more familiar words or morphemes.

The term folk etymology is a loan translation from German Volksetymologie, coined by Ernst Förstemann in 1852.[5] Folk etymology is a productive process in historical linguistics, language change, and social interaction.[6] Reanalysis of a word's history or original form can affect its spelling, pronunciation, or meaning. This is frequently seen in relation to loanwords or words that have become archaic or obsolete.

Examples of words created or changed through folk etymology include the English dialectal form sparrowgrass, originally from Greek ἀσπάραγος ("asparagus") remade by analogy to the more familiar words sparrow and grass.[7] When the alteration of an unfamiliar word is limited to a single person, it is known as an eggcorn.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Folk_etymology

The roach, or rutilus roach (Rutilus rutilus), also known as the common roach, is a fresh- and brackish-water fish of the family Cyprinidae, native to most of Europe and western Asia. Fish called roach can be any species of the genera Rutilus and Hesperoleucus, depending on locality. The plural of the term is also roach.[3]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Common_roach

A loophole is an ambiguity or inadequacy in a system, such as a law or security, which can be used to circumvent or otherwise avoid the purpose, implied or explicitly stated, of the system.

Originally, the word meant an arrowslit, a narrow vertical window in a wall through which an archer (or, later, gunman) could shoot. Loopholes were commonly used in U.S. forts built during the 1800s. Located in the sally port, a loophole was considered a last ditch defense, where guards could close off the inner and outer doors trapping enemy soldiers and using small arms fire through the slits.[1]

Loopholes are distinct from lacunae, although the two terms are often used interchangeably.[citation needed] In a loophole, a law addressing a certain issue exists, but can be legally circumvented due to a technical defect in the law, such as a situation where the details are under-specified. A lacuna, on the other hand, is a situation in which no law exists in the first place to address that particular issue.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Loophole

Collective intelligence (CI) is shared or group intelligence (GI) that emerges from the collaboration, collective efforts, and competition of many individuals and appears in consensus decision making.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Collective_intelligence

Collective intelligence (CI) is shared or group intelligence (GI) that emerges from the collaboration, collective efforts, and competition of many individuals and appears in consensus decision making. The term appears in sociobiology, political science and in context of mass peer review and crowdsourcing applications. It may involve consensus, social capital and formalisms such as voting systems, social media and other means of quantifying mass activity.[1] Collective IQ is a measure of collective intelligence, although it is often used interchangeably with the term collective intelligence. Collective intelligence has also been attributed to bacteria and animals.[2]

It can be understood as an emergent property from the synergies among:

- data-information-knowledge

- software-hardware

- individuals (those with new insights as well as recognized authorities) that continually learns from feedback to produce just-in-time knowledge for better decisions than these three elements acting alone[1][3]

Or it can be more narrowly understood as an emergent property between people and ways of processing information.[4] This notion of collective intelligence is referred to as "symbiotic intelligence" by Norman Lee Johnson.[5] The concept is used in sociology, business, computer science and mass communications: it also appears in science fiction. Pierre Lévy defines collective intelligence as, "It is a form of universally distributed intelligence, constantly enhanced, coordinated in real time, and resulting in the effective mobilization of skills. I'll add the following indispensable characteristic to this definition: The basis and goal of collective intelligence is mutual recognition and enrichment of individuals rather than the cult of fetishized or hypostatized communities."[6] According to researchers Pierre Lévy and Derrick de Kerckhove, it refers to capacity of networked ICTs (Information communication technologies) to enhance the collective pool of social knowledge by simultaneously expanding the extent of human interactions.[7][8] A broader definition was provided by Geoff Mulgan in a series of lectures and reports from 2006 onwards [9] and in the book Big Mind [10] which proposed a framework for analysing any thinking system, including both human and machine intelligence, in terms of functional elements (observation, prediction, creativity, judgement etc.), learning loops and forms of organisation. The aim was to provide a way to diagnose, and improve, the collective intelligence of a city, business, NGO or parliament.

Collective intelligence strongly contributes to the shift of knowledge and power from the individual to the collective. According to Eric S. Raymond in 1998 and JC Herz in 2005,[11][12] open-source intelligence will eventually generate superior outcomes to knowledge generated by proprietary software developed within corporations.[13] Media theorist Henry Jenkins sees collective intelligence as an 'alternative source of media power', related to convergence culture. He draws attention to education and the way people are learning to participate in knowledge cultures outside formal learning settings. Henry Jenkins criticizes schools which promote 'autonomous problem solvers and self-contained learners' while remaining hostile to learning through the means of collective intelligence.[14] Both Pierre Lévy and Henry Jenkins support the claim that collective intelligence is important for democratization, as it is interlinked with knowledge-based culture and sustained by collective idea sharing, and thus contributes to a better understanding of diverse society.[15][16]

Similar to the g factor (g) for general individual intelligence, a new scientific understanding of collective intelligence aims to extract a general collective intelligence factor c factor for groups indicating a group's ability to perform a wide range of tasks.[17] Definition, operationalization and statistical methods are derived from g. Similarly as g is highly interrelated with the concept of IQ,[18][19] this measurement of collective intelligence can be interpreted as intelligence quotient for groups (Group-IQ) even though the score is not a quotient per se. Causes for c and predictive validity are investigated as well.

Writers who have influenced the idea of collective intelligence include Francis Galton, Douglas Hofstadter (1979), Peter Russell (1983), Tom Atlee (1993), Pierre Lévy (1994), Howard Bloom (1995), Francis Heylighen (1995), Douglas Engelbart, Louis Rosenberg, Cliff Joslyn, Ron Dembo, Gottfried Mayer-Kress (2003), and Geoff Mulgan.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Collective_intelligence

Ambiguity is the type of meaning in which a phrase, statement or resolution is not explicitly defined, making several interpretations plausible. A common aspect of ambiguity is uncertainty. It is thus an attribute of any idea or statement whose intended meaning cannot be definitively resolved, according to a rule or process with a finite number of steps. (The ambi- part of the term reflects an idea of "two," as in "two meanings.")

The concept of ambiguity is generally contrasted with vagueness. In ambiguity, specific and distinct interpretations are permitted (although some may not be immediately obvious), whereas with information that is vague, it is difficult to form any interpretation at the desired level of specificity.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ambiguity

Plausible deniability is the ability of people, typically senior officials in a formal or informal chain of command, to deny knowledge of or responsibility for actions committed by members of their organizational hierarchy. They may do so because of a lack or absence of evidence that can confirm their participation, even if they were personally involved in or at least willfully ignorant of the actions. If illegal or otherwise disreputable and unpopular activities become public, high-ranking officials may deny any awareness of such acts to insulate themselves and shift the blame onto the agents who carried out the acts, as they are confident that their doubters will be unable to prove otherwise. The lack of evidence to the contrary ostensibly makes the denial plausible (credible), but sometimes, it makes any accusations only unactionable.

The term typically implies forethought, such as intentionally setting up the conditions for the plausible avoidance of responsibility for one's future actions or knowledge. In some organizations, legal doctrines such as command responsibility exist to hold major parties responsible for the actions of subordinates who are involved in actions and nullify any legal protection that their denial of involvement would carry.

In politics and espionage, deniability refers to the ability of a powerful player or intelligence agency to pass the buck and to avoid blowback by secretly arranging for an action to be taken on its behalf by a third party that is ostensibly unconnected with the major player. In political campaigns, plausible deniability enables candidates to stay clean and denounce third-party advertisements that use unethical approaches or potentially libelous innuendo.

Although plausible deniability has existed throughout history, the term was coined by the CIA in the early 1960s to describe the withholding of information from senior officials to protect them from repercussions if illegal or unpopular activities became public knowledge.[1]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plausible_deniability

Falsifiability is a deductive standard of evaluation of scientific theories and hypotheses, introduced by the philosopher of science Karl Popper in his book The Logic of Scientific Discovery (1934).[B] A theory or hypothesis is falsifiable (or refutable) if it can be logically contradicted by an empirical test.

Popper proposed falsifiability as the cornerstone solution to both the problem of induction and the problem of demarcation. He insisted that, as a logical criterion, falsifiability is distinct from the related concept "capacity to be proven wrong" discussed in Lakatos' falsificationism.[C][D][E] Even being a logical criterion, its purpose is to make the theory predictive and testable, and thus useful in practice.

Popper contrasted falsifiability to the intuitively similar concept of verifiability that was then current in logical positivism. His argument goes that the only way to verify a claim such as "All swans are white" would be if one could theoretically observe all swans,[F] which is not possible. Instead, falsifiability searches for the anomalous instance, such that observing a single black swan is theoretically reasonable and sufficient to logically falsify the claim. On the other hand, the Duhem–Quine thesis says that definitive experimental falsifications are impossible[1] and that no scientific hypothesis is by itself capable of making predictions, because an empirical test of the hypothesis requires one or more background assumptions.[2]

According to Popper there is a clean asymmetry on the logical side[G] and falsifiability does not have the Duhem problem[H] because it is a logical criterion. Experimental research has the Duhem problem and other problems, such as induction,[I] but, according to Popper, statistical tests, which are only possible when a theory is falsifiable, can still be useful within a critical discussion. Philosophers such as Deborah Mayo consider that Popper "comes up short" in his description of the scientific role of statistical and data models.[3]

As a key notion in the separation of science from non-science and pseudoscience, falsifiability has featured prominently in many scientific controversies and applications, even being used as legal precedent.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Falsifiability

Imre Lakatos divided the problems of falsification in two categories. The first category corresponds to decisions that must be agreed upon by scientists before they can falsify a theory. The other category emerges when one tries to use falsifications and corroborations to explain progress in science. Lakatos described four kind of falsificationisms in view of how they address these problems. Dogmatic falsificationism ignores both types of problems. Methodological falsificationism addresses the first type of problems by accepting that decisions must be taken by scientists. Naive methodological falsificationism or naive falsificationism does not do anything to address the second type of problems.[62][63] Lakatos used dogmatic and naive falsificationism to explain how Popper's philosophy changed over time and viewed sophisticated falsificationism as his own improvement on Popper's philosophy, but also said that Popper some times appears as a sophisticated falsificationist.[64] Popper responded that Lakatos misrepresented his intellectual history with these terminological distinctions.[65]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Falsifiability#Falsificationism

Popper's way to analyze progress in science was through the concept of verisimilitude, a way to define how close a theory is to the truth, which he did not consider very significant, except (as an attempt) to describe a concept already clear in practice. Later, it was shown that the specific definition proposed by Popper cannot distinguish between two theories that are false, which is the case for all theories in the history of science.[BJ] Today, there is still on going research on the general concept of verisimilitude.[69]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Falsifiability#Falsificationism

Unfalsifiability versus falsity of astrology

Popper often uses astrology as an example of a pseudoscience. He says that it is not falsifiable because both the theory itself and its predictions are too imprecise.[CC] Kuhn, as an historian of science, remarked that many predictions made by astrologers in the past were quite precise and they were very often falsified. He also said that astrologers themselves acknowledged these falsifications.[CD]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Falsifiability#Falsificationism

In science and philosophy, an ad hoc hypothesis is a hypothesis added to a theory in order to save it from being falsified. Often, ad hoc hypothesizing is employed to compensate for anomalies not anticipated by the theory in its unmodified form.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ad_hoc_hypothesis

"Adding epicycles" has come to be used as a derogatory comment in modern scientific discussion. The term might be used, for example, to describe continuing to try to adjust a theory to make its predictions match the facts. There is a generally accepted idea that extra epicycles were invented to alleviate the growing errors that the Ptolemaic system noted as measurements became more accurate, particularly for Mars. According to this notion, epicycles are regarded by some as the paradigmatic example of bad science.[35]

Copernicus added an extra epicycle to his planets, but that was only in an effort to eliminate Ptolemy's equant, which he considered a philosophical break away from Aristotle's perfection of the heavens. Mathematically, the second epicycle and the equant produce the same results, and many Copernican astronomers before Kepler continued using the equant, as the mathematical calculations were easier. Copernicus' epicycles were also much smaller than Ptolemy's, and were required because the planets in his model moved in perfect circles. Johannes Kepler would later show that the planets move in ellipses, which removed the need for Copernicus' epicycles as well.[36]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deferent_and_epicycle#Bad_science

A paraconsistent logic is an attempt at a logical system to deal with contradictions in a discriminating[clarification needed] way. Alternatively, paraconsistent logic is the subfield of logic that is concerned with studying and developing "inconsistency-tolerant" systems of logic which reject the principle of explosion.

Inconsistency-tolerant logics have been discussed since at least 1910 (and arguably much earlier, for example in the writings of Aristotle);[1] however, the term paraconsistent ("beside the consistent") was first coined in 1976, by the Peruvian philosopher Francisco Miró Quesada Cantuarias.[2] The study of paraconsistent logic has been dubbed paraconsistency,[3] which encompasses the school of dialetheism.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paraconsistent_logic

Ad hoc is a Latin phrase meaning literally 'for this'. In English, it typically signifies a solution for a specific purpose, problem, or task rather than a generalized solution adaptable to collateral instances. (Compare with a priori.)

Common examples are ad hoc committees and commissions created at the national or international level for a specific task. In other fields, the term could refer to, for example, a military unit created under special circumstances (see task force), a handcrafted network protocol (e.g., ad hoc network), a temporary banding together of geographically-linked franchise locations (of a given national brand) to issue advertising coupons, or a purpose-specific equation.

Ad hoc can also be an adjective describing the temporary, provisional, or improvised methods to deal with a particular problem, the tendency of which has given rise to the noun adhocism.[1]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ad_hoc

Ad infinitum is a Latin phrase meaning "to infinity" or "forevermore".

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ad_infinitum

Confirmation bias is the tendency to search for, interpret, favor, and recall information in a way that confirms or supports one's prior beliefs or values.[1] People display this bias when they select information that supports their views, ignoring contrary information, or when they interpret ambiguous evidence as supporting their existing attitudes. The effect is strongest for desired outcomes, for emotionally charged issues, and for deeply entrenched beliefs. Confirmation bias cannot be eliminated, but it can be managed, for example, by education and training in critical thinking skills.

Biased search for information, biased interpretation of this information, and biased memory recall, have been invoked to explain four specific effects:

- attitude polarization (when a disagreement becomes more extreme even though the different parties are exposed to the same evidence)

- belief perseverance (when beliefs persist after the evidence for them is shown to be false)

- the irrational primacy effect (a greater reliance on information encountered early in a series)

- illusory correlation (when people falsely perceive an association between two events or situations).

A series of psychological experiments in the 1960s suggested that people are biased toward confirming their existing beliefs. Later work re-interpreted these results as a tendency to test ideas in a one-sided way, focusing on one possibility and ignoring alternatives. Explanations for the observed biases include wishful thinking and the limited human capacity to process information. Another proposal is that people show confirmation bias because they are pragmatically assessing the costs of being wrong, rather than investigating in a neutral, scientific way.

Flawed decisions due to confirmation bias have been found in a wide range of political, organizational, financial and scientific contexts. These biases contribute to overconfidence in personal beliefs and can maintain or strengthen beliefs in the face of contrary evidence. For example, confirmation bias produces systematic errors in scientific research based on inductive reasoning (the gradual accumulation of supportive evidence). Similarly, a police detective may identify a suspect early in an investigation, but then may only seek confirming rather than disconfirming evidence. A medical practitioner may prematurely focus on a particular disorder early in a diagnostic session, and then seek only confirming evidence. In social media, confirmation bias is amplified by the use of filter bubbles, or "algorithmic editing", which display to individuals only information they are likely to agree with, while excluding opposing views.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Confirmation_bias

Inductive reasoning is a method of reasoning in which a general principle is derived from a body of observations.[1] It consists of making broad generalizations based on specific observations.[2] Inductive reasoning is distinct from deductive reasoning, where the conclusion of a deductive argument is certain given the premises are correct; in contrast, the truth of the conclusion of an inductive argument is probable, based upon the evidence given.[3]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Inductive_reasoning

Ad hoc testing is a commonly used term for planned software testing that is performed without initial test case documentation;[1] however, ad hoc testing can also be applied to other scientific research and quality control efforts.[2] Ad hoc tests are useful for adding additional confidence to a resulting product or process, as well as quickly spotting important defects or inefficiencies,[1][3] but they have some disadvantages, such as having inherent uncertainties in their performance[4][5] and not being as useful without proper documentation post-execution and -completion.[1][3] Occasionally, ad hoc testing is compared to exploratory testing as being less rigorous, though others argue that ad hoc testing still has value as "improvised testing that deals well with verifying a specific subject."[6]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ad_hoc_testing

In music and other performing arts, the phrase ad libitum (/ædˈlɪbɪtəm/; from Latin for 'at one's pleasure' or 'as you desire'), often shortened to "ad lib" (as an adjective or adverb) or "ad-lib" (as a verb or noun), refers to various forms of improvisation.

The roughly synonymous phrase a bene placito ('in accordance with [one's] good pleasure') is less common but, in its Italian form a piacere, has entered the musical lingua franca (see below).

The phrase "at liberty" is often associated mnemonically (because of the alliteration of the lib- syllable), although it is not the translation (there is no cognation between libitum and liber). Libido is the etymologically closer cognate known in English.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ad_libitum

Improvisation is the activity of making or doing something not planned beforehand, using whatever can be found.[1] Improvisation in the performing arts is a very spontaneous performance without specific or scripted preparation. The skills of improvisation can apply to many different faculties, across all artistic, scientific, physical, cognitive, academic, and non-academic disciplines; see Applied improvisation.

Improvisation also exists outside the arts. Improvisation in engineering is to solve a problem with the tools and materials immediately at hand. Improvised weapons are often used by guerrillas, insurgents and criminals.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Improvisation

Extemporaneous Speaking (Extemp, or EXT) is a

speech delivery style/speaking style, and a term that identifies a

specific forensic competition. The competition is a speech event based

on research and original analysis, done with a limited-preparation; in

the United States those competitions are held for high school and college

students. In a Extemporaneous Speech competition, enrolled participants

prepare for thirty minutes on a question related to current events and

then give a seven-minute speech responding to that question.[1] The extemporaneous speaking delivery style, referred to as "off-the-cuff",[2] is a type of delivery method for a public presentation, that was carefully prepared and practiced but not memorized.[3]

Extemporaneous speech is considered to have elements of two other types of speeches, the manuscript (written text that can be read or memorized) and the impromptu (making remarks with little to no preparation).[4] When searching for "extemporaneous", the person will find that "impromptu" is a synonym for "extemporaneous". However, for speech delivery styles, this is not the case. An extemporaneous speech is planned and practiced, but when delivered, is not read. Presenters will normally rely on small notes or outlines with key points. This type of delivery style is recommended because audiences perceive it as more conversational, natural, and spontaneous, and it will be delivered in a slightly different manner each time, because it’s not memorized.[5]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Extemporaneous_speaking

Extemporaneous commentary (or extemp com for short) is a branch of normal extemporaneous speaking, an area of competition in high school forensics. Students participating in extemporaneous commentary are given 20 minutes to prepare a five-minute speech (with a 30-second grace period) on a topic relevant to modern politics. Students in commentary deliver their speeches sitting down, usually on the opposite side of a table from the judge(s). Students are score based on oration skills, speech organization, and use of sources and are ranked by the judges in comparison to the other competitors who give speeches in the same room.

At the beginning of a tournament, students participating in this event are brought to a holding room, where an order is assigned (usually by picking numbers at random). The first student then draws three topics, chooses one which s/he finds best, and then is given his/her 20 minutes of preparation. The remaining students draw their topics at seven-minute intervals to ensure that no student gets extra time to prepare. After all the students have given a speech, the judges rank the students in order of who they believed performed the best based on the categories above.

Originally, extemporaneous commentary topics were more general and more focused on opinions than extemporaneous topics were, making extemp commentary an almost "halfway point" between impromptu speaking and normal extemp. However, the success of those who integrated more sources into their speeches, plus the trending of the topics to mimic extemp's, has blurred the line between extemporaneous and extemporaneous commentary. In some cases extemp commentary has a shorter prep time, and shorter speeches. The only definitive difference between extemp and extemp commentary is the position in which the speeches are given (standing as opposed to sitting).

Extemp commentary has been an event at the National Speech and Debate Tournament since 1985.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Extemporaneous_commentary

- Script, a distinctive writing system, based on a repertoire of specific elements or symbols, or that repertoire

- Script (styles of handwriting)

- Script typeface, a typeface with characteristics of handwriting

- Script (Unicode), historical and modern scripts as organised in Unicode glyph encoding

Arts, entertainment, and media

- Script (comics), the dialogue for a comic book or comic strip

- Script (video games), the narrative and text of a video game

- Manuscript, any written document, often story-based and unpublished

- Play (theatre), the dialogue and stage directions for a theatrical production

- Rob Wagner's Script, a defunct literary magazine edited by Rob Wagner

- Screenplay, the dialogue, action and locations for film or television

- Scripted sequence, a predefined series of events in a video game triggered by player location or actions

- The Script, an Irish band

- The Script (album), their 2008 debut album

Computing and technology

- Scripting language, in which computer programming scripts are written

- SCRIPT (markup), a text formatting language developed by IBM

- script (Unix), a command that records a terminal session

- Script, a description of procedural knowledge used in script theory, also used in artificial intelligence

Medicine and psychology

- SCRIPT (medicine), a standard for electronically transmitted medical prescriptions

- SCRIPT (mnemonic), a memory aid related to heart murmurs

- Behavioral script, a sequence of expected behaviors

- Life (or childhood) script, in transactional analysis

- Medical prescription (abbreviated Rx, scrip, or script), official health instructions

Other uses

- SCRIPT (AHRC Centre), the Scottish Centre for Research in Intellectual Property and Technologies

See also

- Scrip, any currency substitute

- Scripps (disambiguation)

- Scripted (company), an online marketplace for businesses and freelance writers

- All pages with titles containing Script

- All pages with titles beginning with Script

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Script

| Old Hungarian 𐲥𐳋𐳓𐳉𐳗-𐲘𐳀𐳎𐳀𐳢 𐲢𐳛𐳮𐳁𐳤 Székely-magyar rovás | |

|---|---|

| Script type | |

Time period | Attested from 10th century. Marginal use into the 17th century, revived in the 20th. |

| Direction | right-to-left script |

| Languages | Hungarian |

| Related scripts | |

Parent systems | Old Turkic

|

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Hung (176), Old Hungarian (Hungarian Runic) |

| Unicode | |

Unicode alias | Old Hungarian |

| U+10C80–U+10CFF | |

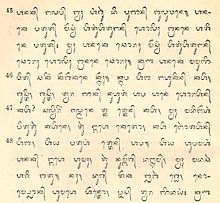

The Old Hungarian script or Hungarian runes (Hungarian: Székely-magyar rovás, 'székely-magyar runiform', or rovásírás) is an alphabetic writing system used for writing the Hungarian language. Modern Hungarian is written using the Latin-based Hungarian alphabet. The term "old" refers to the historical priority of the script compared with the Latin-based one.[1] The Old Hungarian script is a child system of the Old Turkic alphabet.[citation needed]

The Hungarians settled the Carpathian Basin in 895. After the establishment of the Christian Hungarian kingdom, the old writing system was partly forced out of use during the rule of King Stephen, and the Latin alphabet was adopted. However, among some professions (e.g. shepherds who used a "rovás-stick" to officially track the number of animals) and in Transylvania, the script has remained in use by the Székely Magyars, giving its Hungarian name (székely) rovásírás. The writing could also be found in churches, such as that in the commune of Atid.

Its English name in the ISO 15924 standard is Old Hungarian (Hungarian Runic).[2][3]

Name

In modern Hungarian, the script is known formally as Székely rovásírás ('Szekler script').[4] The writing system is generally known as rovásírás, székely rovásírás,[4] and székely-magyar írás (or simply rovás 'notch, score').[5]

History

Origins

Scientists cannot give an exact date or origin for the script.

Linguist András Róna-Tas derives Old Hungarian from the Old Turkic script,[6] itself recorded in inscriptions dating from c. AD 720. The origins of the Turkic scripts are uncertain. The scripts may be derived from Asian scripts such as the Pahlavi and Sogdian alphabets, or possibly from Kharosthi, all of which are in turn derived from the Aramaic script.[7] Alternatively, according to some opinions, ancient Turkic runes descend from primaeval Turkic graphic logograms.[8]

Speakers of Proto-Hungarian would have come into contact with Turkic peoples during the 7th or 8th century, in the context of the Turkic expansion, as is also evidenced by numerous Turkic loanwords in Proto-Hungarian.

All the letters but one for sounds which were shared by Turkic

and Ancient Hungarian can be related to their Old Turkic counterparts.

Most of the missing characters were derived by script internal

extensions, rather than borrowings, but a small number of characters

seem to derive from Greek, such as ![]() 'eF'.[9]

'eF'.[9]

The modern Hungarian term for this script (coined in the 19th century), rovás, derives from the verb róni ('to score') which is derived from old Uralic, general Hungarian terminology describing the technique of writing (írni 'to write', betű 'letter', bicska 'knife, also: for carving letters') derive from Turkic,[10] which further supports transmission via Turkic alphabets.

Medieval Hungary

Epigraphic evidence for the use of the Old Hungarian script in medieval Hungary dates to the 10th century, for example, from Homokmégy.[11] The latter inscription was found on a fragment of a quiver made of bone. Although there have been several attempts to interpret it, the meaning of it is still unclear.

In 1000, with the coronation of Stephen I of Hungary, Hungary (previously an alliance of mostly nomadic tribes) became a kingdom. The Latin alphabet was adopted as official script; however, Old Hungarian continued to be used in the vernacular.

The runic script was first mentioned in the 13th century Chronicle of Simon of Kéza,[12] where he stated that the Székelys may use the script of the Blaks.[13][14][15] Johannes Thuróczy wrote in the Chronica Hungarorum that the Székelys did not forget the Scythian letters and these are engraved on sticks by carving.[16]

There were still three thousand Huns who fled the battle of Crimhild, who fearing from the western nations, they remained on the cliff field until the time of Árpád, and they did not call themselves Huns, but Szekelys. These Szekelys were the remains of the Huns, who when they learned that the Hungarians had returned to Pannonia for the second time, went to the returnees on the border of Ruthenia and conquered Pannonia together, but not on the Pannonian plane, they were granted estates in the mountainous borderlands together with the Blackis, where mingling with the Blackis it is said they used their letters.

It is said that in addition to the Huns who escorted Csaba, from the same nation, three thousand more people retreating, cut themselves out of the said battle, remained in Pannonia, and first established themself in a camp called Csigla's Field. They were afraid of the Western nations which they harassed in Attila's life, and they marched to Transylvania, the frontier of the Pannonian landscape, and they did not call themselves Huns or Hungarians, but Siculus, in their own word Székelys, so that they would not know that they are the remnants of the Huns or Hungarians. In our time, no one doubts, that the Székelys are the remnants of the Huns who first came to Pannonia, and because their people do not seem to have been mixed with foreign blood since then, they are also more strict in their morals, they also differ from other Hungarians in the division of lands. They have not yet forgotten the Scythian letters, and these are not inked on paper, but engraved on sticks skillfully, in the way of the carving. They later grew into not insignificant people, and when the Hungarians came to Pannonia again from Scythia, they went to Ruthenia in front of them with great joy, as soon as the news of their coming came to them. When the Hungarians took possession of Pannonia again, at the division of the country, with the consent of the Hungarians, these Székelys were given the part of the country that they had already chosen as their place of residence.

Early Modern period

The Old Hungarian script became part of folk art in several areas during this period.[citation needed] In Royal Hungary, Old Hungarian script was used less, although there are relics from this territory, too. There is another copy – similar to the Nikolsburg Alphabet – of the Old Hungarian alphabet, dated 1609. The inscription from Énlaka, dated 1668, is an example of the "folk art use".

There are a number of inscriptions ranging from the 17th to the early 19th centuries,[18] including examples from Kibéd, Csejd, Makfalva, Szolokma, Marosvásárhely, Csíkrákos, Mezőkeresztes, Nagybánya, Torda, Felsőszemeréd,[19] Kecskemét and Kiskunhalas.

Scholarly discussion

Hungarian script[20] was first described in late Humanist/Baroque scholarship by János Telegdy in his primer Rudimenta Priscae Hunnorum Linguae. Published in 1598, Telegdi's primer presents his understanding of the script and contains Hungarian texts written with runes, such as the Lord's Prayer.

In the 19th century, scholars began to research the rules and the other features of the Old Hungarian script. From this time, the name rovásírás ('runic writing') began to re-enter the popular consciousness in Hungary, and script historians in other countries began to use the terms "Old Hungarian", Altungarisch, and so on. Because the Old Hungarian script had been replaced by Latin, linguistic researchers in the 20th century had to reconstruct the alphabet from historic sources. Gyula Sebestyén, an ethnographer and folklorist, and Gyula (Julius) Németh, a philologist, linguist, and Turkologist, did the lion's share of this work. Sebestyén's publications, Rovás és rovásírás (Runes and runic writing, Budapest, 1909) and A magyar rovásírás hiteles emlékei (The authentic relics of Hungarian runic writing, Budapest, 1915) contain valuable information on the topic.

Popular revival

Beginning with Adorján Magyar in 1915, the script has been promulgated as a means for writing modern Hungarian. These groups approached the question of representation of the vowels of modern Hungarian in different ways. Adorján Magyar made use of characters to distinguish a/á and e/é but did not distinguish the other vowels by length. A school led by Sándor Forrai from 1974 onward did, however, distinguish i/í, o/ó, ö/ő, u/ú, and ü/ű. The revival has become part of a significant ideological nationalist subculture present not only in Hungary (largely centered in Budapest), but also amongst the Hungarian diaspora, particularly in the United States and Canada.[21]

Old Hungarian has seen other usages in the modern period, sometimes in association with or referencing Hungarian neopaganism,[citation needed] similar to the way in which Norse neopagans have taken up the Germanic runes, and Celtic neopagans have taken up the ogham script for various purposes.

Controversies

Not all scholars agree with the "Old Hungarian" notion, mainly based on the actual literary facts. The linguist and sociolinguist Klára Sándor told in an interview that most of the "romantic" statements about the script appear to be false. According to her analysis, the origin of the writing is probably runiform (and with high probability its origins are in the western Turkic runiform writings) and it's not a different writing system and contrary to the sentiment the writing is neither Hungarian nor Székely-Hungarian; it is a Székely writing since there are no authentic findings outside the historic Székely lands (mainly today's Transylvania); the only writing found around 1000 AD had a different writing system. While it may have been sporadically used in Hungary its usage was not widespread. The "revived" writing (in the 1990s) was artificially expanded with (various) "new" letters which were unneeded in the past since the writing was cleanly phonetic, or the long vowels which were not present back in the time. The shape of many letters were substantially changed from the original. She stated that no works since 1915 has reached the expected quality of the state of the linguistic sciences, and many was influenced by various agendas.[22][23]

The use of the script often has a political undertone as it is often used along with irredentist or nationalist propaganda, and they can be found from time to time in graffiti with a variety of content.[21] Since most of the people cannot read the script it has led to various controversies, for example when the activists of the Hungarian Two-tailed Dog Party (opposition) exchanged the rovas sign of the city Érd to szia 'Hi!', which stayed unnoticed a month.[24]

Epigraphy

The inscription corpus includes:

- A labeled crest etched into stone from Pécs, late 13th century (Label: aBA SZeNTjeI vaGYUNK aKI eSZTeR ANna erZSéBeT; We are the saints [nuns] of Aba; who are Esther, Anna and Elizabeth.)[citation needed]

- Rod calendar, around 1300, copied by Luigi Ferdinando Marsigli in 1690.[25] It contains several feasts and names, thus it is one of the most extensive runic records.

- Nicholsburg alphabet[26]

- Runic record in Istanbul, 1515.[27]

- Székelyderzs: a brick with runic inscription, found in the Unitarian church[citation needed]

- Énlaka runic inscription, discovered by Balázs Orbán in 1864[26][28]

- Székelydálya: runic inscription, found in the Calvinist church[citation needed]

- The inscription from Felsőszemeréd (Horné Semerovce), Slovakia (15th century)[citation needed]

Characters

The runic alphabet included 42 letters. As in the Old Turkic script, some consonants had two forms, one to be used with back vowels (a, á, o, ó, u, ú) and another for front vowels (e, é, i, í, ö, ő, ü, ű). The names of the consonants are always pronounced with a vowel. In the old alphabet, the consonant-vowel order is reversed, unlike today's pronunciation (ep rather than pé). This is because the oldest inscriptions lacked vowels and were rarely written down, similar to other ancient languages' consonant-writing systems (Arabic, Hebrew, Aramaic, etc.). The alphabet did not contain letters for the phonemes dz and dzs of modern Hungarian, since these are relatively recent developments in the language's history. Nor did it have letters corresponding to the Latin q, w, x and y. The modern revitalization movement has created symbols for these; in Unicode encoding, they are represented as ligatures.

For more information about the transliteration's pronunciation, see Hungarian alphabet.

| Letter | Name | Phoneme (IPA) | Old Hungarian (image) | Old Hungarian (Unicode) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | a | /ɒ/ |

𐲀 𐳀 | |

| Á | á | /aː/ |

𐲁 𐳁 | |

| B | eb | /b/ |

𐲂 𐳂 | |

| C | ec | /ts/ |

𐲄 𐳄 | |

| Cs | ecs | /tʃ/ | 𐲆 𐳆 | |

| D | ed | /d/ |

𐲇 𐳇 | |

| (Dz) | dzé | /dz/ |

Ligature of 𐲇 and 𐲯 | |

| (Dzs) | dzsé | /dʒ/ | Ligature of 𐲇 and 𐲰 | |

| E | e | /ɛ/ |

𐲉 𐳉 | |

| É | é | /eː/ |

𐲋 𐳋 | |

| F | ef | /f/ |

𐲌 𐳌 | |

| G | eg | /ɡ/ |

𐲍 𐳍 | |

| Gy | egy | /ɟ/ |

𐲎 𐳎 | |

| H | eh | /h/ | 𐲏 𐳏 | |

| I | i | /i/ | 𐲐 𐳐 | |

| Í | í | /iː/ |

𐲑 𐳑 | |

| J | ej | /j/ |

𐲒 𐳒 | |

| K | ek | /k/ |

𐲓 𐳓 | |

| K | ak | /k/ |

𐲔 𐳔 | |

| L | el | /l/ |

𐲖 𐳖 | |

| Ly | elly, el-ipszilon | /j/ |

𐲗 𐳗 | |

| M | em | /m/ |

𐲘 𐳘 | |

| N | en | /n/ | 𐲙 𐳙 | |

| Ny | eny | /ɲ/ |

𐲚 𐳚 | |

| O | o | /o/ | 𐲛 𐳛 | |

| Ó | ó | /oː/ |

𐲜 𐳜 | |

| Ö | ö | /ø/ |

𐲝 𐳝 𐲞 𐳞 | |

| Ő | ő | /øː/ | 𐲟 𐳟 | |

| P | ep | /p/ |

𐲠 𐳠 | |

| (Q) | eq | (/kv/) | Ligature of 𐲓 and 𐲮 | |

| R | er | /r/ |

𐲢 𐳢 | |

| S | es | /ʃ/ |

𐲤 𐳤 | |

| Sz | esz | /s/ |

𐲥 𐳥 | |

| T | et | /t/ |

𐲦 𐳦 | |

| Ty | ety | /c/ |

𐲨 𐳨 | |

| U | u | /u/ | 𐲪 𐳪 | |

| Ú | ú | /uː/ |

𐲫 𐳫 | |

| Ü | ü | /y/ | 𐲬 𐳬 | |

| Ű | ű | /yː/ |

𐲭 𐳭 | |

| V | ev | /v/ |

𐲮 𐳮 | |

| (W) | dupla vé | /v/ |

Ligature of 𐲮 and 𐲮 | |

| (X) | iksz | (/ks/) | Ligature of 𐲓 and 𐲥 | |

| (Y) | ipszilon | /i/ ~ /j/ | Ligature of 𐲐 and 𐲒 | |

| Z | ez | /z/ |

𐲯 𐳯 | |

| Zs | ezs | /ʒ/ |

𐲰 𐳰 |

The Old Hungarian runes also include some non-alphabetical runes which are not ligatures but separate signs. These are identified in some sources as "capita dictionum" (likely a misspelling of capita dicarum[29]). Further research is needed to define their origin and traditional usage. Some common examples are:

Features

Old Hungarian letters were usually written from right to left on sticks.[citation needed] Later, in Transylvania, they appeared on several media. Writings on walls also were right to left[citation needed] and not boustrophedon style (alternating direction right to left and then left to right).

The numbers are almost the same as the Roman, Etruscan, and Chuvash numerals. Numbers of livestock were carved on tally sticks and the sticks were then cut in two lengthwise to avoid later disputes.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 50 | 100 | 500 | 1000 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 𐳺 | 𐳺𐳺 | 𐳺𐳺𐳺 | 𐳺𐳺𐳺𐳺 | 𐳻 | 𐳻𐳺 | 𐳻𐳺𐳺 | 𐳻𐳺𐳺𐳺 | 𐳻𐳺𐳺𐳺𐳺 | 𐳼 | 𐳽 | 𐳾 | ̲𐳽 | 𐳿 |

- Ligatures are common. (Note: the Hungarian runic script employed a number of ligatures. In some cases, an entire word was written with a single sign similar to a bind rune.) The Unicode standard supports ligatures explicitly by using the zero width joiner between the two characters.[30]

- There are no lower or upper case letters, but the first letter of a proper name was often written a bit larger. Though the Unicode standard has upper and lowercase letters, which are the same in shape, the difference is only their size.

- The writing system did not always mark vowels (similar to many Asian

writing systems). The rules for vowel inclusion were as follows:

- If there are two vowels side by side, both have to be written, unless the second could be readily determined.

- The vowels have to be written if their omission created ambiguity. (Example: krk –

can be interpreted as kerék –

can be interpreted as kerék –

(wheel) and kerek –

(wheel) and kerek –

(rounded), thus the writer had to include the vowels to differentiate the intended words.)

(rounded), thus the writer had to include the vowels to differentiate the intended words.) - The vowel at the end of the word must be written.

- Sometimes, especially when writing consonant clusters, a consonant was omitted. This is a phonologic process, with the script reflecting the exact surface realization.

Text example

Text from Csíkszentmárton, 1501. Runes originally written as ligatures are underlined.

Unicode transcription: 𐲪𐲢𐲙𐲔⁝𐲥𐲬𐲖𐲦𐲤𐲦𐲬𐲖⁝𐲌𐲛𐲍𐲮𐲀𐲙⁝𐲐𐲢𐲙𐲔⁝𐲯𐲢𐲞𐲦 ⁝𐲥𐲀𐲯𐲎⁝𐲥𐲦𐲙𐲇𐲞𐲂𐲉⁝𐲘𐲀𐲨𐲤⁝𐲒𐲀𐲙𐲛𐲤⁝𐲤𐲨𐲦𐲙⁝𐲓𐲛𐲮𐲀𐲆⁝𐲆𐲐𐲙𐲀𐲖𐲦𐲔⁝𐲘𐲀𐲨𐲀𐲤𐲘𐲤𐲦𐲢⁝𐲍𐲢𐲍𐲗𐲘𐲤𐲦𐲢𐲆𐲐𐲙𐲀𐲖𐲦𐲀𐲔 𐲍·𐲐𐲒·𐲀·𐲤·𐲐·𐲗·𐲗·𐲖𐲦·𐲀·

Interpretation in old Hungarian: "ÚRNaK SZÜLeTéSéTÜL FOGVÁN ÍRNaK eZeRÖTSZÁZeGY eSZTeNDŐBE MÁTYáS JÁNOS eSTYTáN KOVÁCS CSINÁLTáK MÁTYáSMeSTeR GeRGeLYMeSTeRCSINÁLTÁK G IJ A aS I LY LY LT A" (The letters actually written in the runic text are written with uppercase in the transcription.)

Interpretation in modern Hungarian: "(Ezt) az Úr születése utáni 1501. évben írták. Mátyás, János, István kovácsok csinálták. Mátyás mester (és) Gergely mester csinálták gijas ily ly lta"

English translation: "(This) was written in the 1501st year of our Lord. The smiths Matthias, John (and) Stephen did (this). Master Matthias (and) Master Gregory did (uninterpretable)

Unicode

After many proposals[31] Old Hungarian was added to the Unicode Standard in June, 2015 with the release of version 8.0.

The Unicode block for Old Hungarian is U+10C80–U+10CFF:

| Old Hungarian[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+10C8x | 𐲀 | 𐲁 | 𐲂 | 𐲃 | 𐲄 | 𐲅 | 𐲆 | 𐲇 | 𐲈 | 𐲉 | 𐲊 | 𐲋 | 𐲌 | 𐲍 | 𐲎 | 𐲏 |

| U+10C9x | 𐲐 | 𐲑 | 𐲒 | 𐲓 | 𐲔 | 𐲕 | 𐲖 | 𐲗 | 𐲘 | 𐲙 | 𐲚 | 𐲛 | 𐲜 | 𐲝 | 𐲞 | 𐲟 |

| U+10CAx | 𐲠 | 𐲡 | 𐲢 | 𐲣 | 𐲤 | 𐲥 | 𐲦 | 𐲧 | 𐲨 | 𐲩 | 𐲪 | 𐲫 | 𐲬 | 𐲭 | 𐲮 | 𐲯 |

| U+10CBx | 𐲰 | 𐲱 | 𐲲 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| U+10CCx | 𐳀 | 𐳁 | 𐳂 | 𐳃 | 𐳄 | 𐳅 | 𐳆 | 𐳇 | 𐳈 | 𐳉 | 𐳊 | 𐳋 | 𐳌 | 𐳍 | 𐳎 | 𐳏 |

| U+10CDx | 𐳐 | 𐳑 | 𐳒 | 𐳓 | 𐳔 | 𐳕 | 𐳖 | 𐳗 | 𐳘 | 𐳙 | 𐳚 | 𐳛 | 𐳜 | 𐳝 | 𐳞 | 𐳟 |

| U+10CEx | 𐳠 | 𐳡 | 𐳢 | 𐳣 | 𐳤 | 𐳥 | 𐳦 | 𐳧 | 𐳨 | 𐳩 | 𐳪 | 𐳫 | 𐳬 | 𐳭 | 𐳮 | 𐳯 |

| U+10CFx | 𐳰 | 𐳱 | 𐳲 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

𐳺 | 𐳻 | 𐳼 | 𐳽 | 𐳾 | 𐳿 |

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

Pre-Unicode encodings

A set of closely related 8-bit code pages exist, devised in the 1990s by Gabor Hosszú. These were mapped to Latin-1 or Latin-2 character set fonts. After installing one of them and applying their formatting to the document – because of the lack of capital letters – runic characters could be entered in the following way: those letters which are unique letters in today's Hungarian orthography are virtually lowercase ones, and can be written by simply pressing the specific key; and since the modern digraphs equal to separate rovás letters, they were encoded as 'uppercase' letters, i.e. in the space originally restricted for capitals. Thus, typing a lowercase g will produce the rovás character for the sound marked with Latin script g, but entering an uppercase G will amount to a rovás sign equivalent to a digraph gy in Latin-based Hungarian orthography.

Gallery

Stone Shield pattern of Pécs with Old Hungarian Script (circa 1250 AD), Hungary

Rovás inscription from Homoródkarácsonyfalva, 13th century

See also

Notes

- Old Hungarian/Szekely-Hungarian Rovas Ad Hoc Committee: Old Hungarian/Sekely-Hungarian Rovas Ad hoc Report Archived 2015-01-04 at the Wayback Machine, 2012-11-12

- Jenő Demeczky, György Giczi, Gábor Hosszú, Gergely Kliha, Borbála Obrusánszky, Tamás Rumi, László Sípos, Erzsébet Zelliger: About the consensus of the Rovas encoding – Response to N4373 (Resolutions of the 8th Hungarian World Congress on the encoding of Old Hungarian)[dead link]. Registered by UTC (L2/12-337), 2012-10-24

- György Gergely Gyetvay (World Federation of Hungarians): Resolutions of the 8th Hungarian World Congress on the encoding of Old Hungarian Archived 2015-01-04 at the Wayback Machine, 2012-10-22

- Jenő Demeczky, György Giczi, Gábor Hosszú, Gergely Kliha, Borbála Obrusánszky, Tamás Rumi, László Sípos, Erzsébet Zelliger: Additional information about the name of the Rovas script Archived 2014-02-22 at the Wayback Machine, 2012-10-21.

- Jenő Demeczky, Gábor Hosszú, Tamás Rumi, László Sípos, Erzsébet Zelliger: Revised proposal for encoding the Rovas in the UCS Archived 2014-03-17 at the Wayback Machine, 2012-10-14.

- Tamás Somfai: Contemporary Rovas in the word processing Archived 2015-01-04 at the Wayback Machine, 2012-05-25

- Michael Everson & André Szabolcs Szelp: Consolidated proposal for encoding the Old Hungarian script in the UCS Archived 2012-12-03 at the Wayback Machine, 2012-05-06

- Miklós Szondi (president of the "Természetesen" society and chair of the "Egységes rovás" conference) Declaration of Support for the Advancement of the Encoding of the old Hungarian Script Archived 2015-01-04 at the Wayback Machine, 2012-04-28

- Gábor Hosszú (Hungarian National Body): Code chart font for Rovas block Archived 2012-05-16 at the Wayback Machine, 2012-02-06

- André Szabolcs Szelp: Remarks on Old Hungarian and other scripts with regard to N4183 Archived 2012-05-27 at the Wayback Machine, 2012-01-30

- Michael Everson (Irish National Body): Code chart fonts for Old Hungarian Archived 2012-05-27 at the Wayback Machine, 2012-01-28

- Gábor Hosszú (Hungarian National Body): Proposal for encoding the Szekely-Hungarian Rovas, Carpathian Basin Rovas and Khazarian Rovas scripts into the Rovas block in the SMP of the UCS Archived 2012-04-07 at the Wayback Machine, 2011-12-15

- Hungarian Runic/Szekely-Hungarian Rovas Ad Hoc Committee: Hungarian Runic/Sekely-Hungarian Rovas Ad-hoc Report Archived 2011-06-29 at the Wayback Machine, 2011-06-08

- Gábor Hosszú: Issues of encoding the Rovas scripts Archived 2011-11-19 at the Wayback Machine, 2011-05-25

- Gábor Hosszú: Comments on encoding the Rovas scripts Archived 2011-11-19 at the Wayback Machine, 2011-05-22

- Gábor Hosszú: Revised proposal for encoding the Szekely-Hungarian Rovas script in the SMP of the UCS Archived 2011-05-23 at the Wayback Machine, 2011-05-21

- Gábor Hosszú: Notes on the Szekely-Hungarian Rovas script Archived 2011-05-23 at the Wayback Machine, 2011-05-15

- Michael Everson & André Szabolcs Szelp: Mapping between Hungarian Runic proposals in N3697 and N4007 Archived 2011-09-16 at the Wayback Machine, 2011-05-08

- Deborah Anderson: Comparison of Hungarian Runic and Szekely‐Hungarian Rovas proposals Archived 2011-06-29 at the Wayback Machine, 2011-05-07

- Deborah Anderson: Outstanding Issues on Old Hungarian/Szekler‐Hungarian Rovas/Hungarian Native Writing Archived 2012-04-07 at the Wayback Machine, 2009-04-22

- Michael Everson: Mapping between Old Hungarian proposals in N3531, N3527, and N3526 Archived 2009-03-06 at the Wayback Machine, 2008-11-02

- Michael Everson and Szabolcs Szelp: Revised proposal for encoding the Old Hungarian script in the UCS = Javított előterjesztés a rovásírás Egyetemes Betűkészlet-beli kódolására) Archived 2009-03-06 at the Wayback Machine, 2008-10-12

- Gábor Hosszú: Proposal for encoding the Szekler-Hungarian Rovas in the BMP and the SMP of the UCS Archived 2008-12-21 at the Wayback Machine, 2008-10-04

- Gábor Bakonyi: Hungarian native writing draft proposal Archived 2009-03-06 at the Wayback Machine, 2008-09-30

- Michael Everson and Szabolcs Szelp: Preliminary proposal for encoding the Old Hungarian script in the UCS Archived 2009-03-06 at the Wayback Machine, 2008-08-04

- Michael Everson: On encoding the Old Hungarian rovásírás in the UCS Archived 2006-06-21 at the Wayback Machine, 1998-05-02

- Michael Everson: Draft Proposal to encode Old Hungarian in Plane 1 of ISO/IEC 10646-2 Archived 2008-09-08 at the Wayback Machine, 1998-01-18

References

English

- Gábor Hosszú (2011): Heritage of Scribes. The Relation of Rovas Scripts to Eurasian Writing Systems. First edition. Budapest: Rovas Foundation, ISBN 978-963-88437-4-6, fully available from Google Books

- Edward D. Rockstein: "The Mystery of the Székely Runes", Epigraphic Society Occasional Papers, Vol. 19, 1990, pp. 176–183

Hungarian

- Új Magyar Lexikon (New Hungarian Encyclopaedia) – Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest, 1962 (Volume 5) ISBN 963-05-2808-8

- Gyula Sebestyén: A magyar rovásírás hiteles emlékei, Budapest, 1915

Latin

- J. Thelegdi: Rudimenta priscae Hunnorum linguae brevibus quaestionibus et responsionibus comprehensa, Batavia, 1598

External links

![]() Media related to Szekely-Hungarian Rovas script at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Szekely-Hungarian Rovas script at Wikimedia Commons

- Hungarian Runes / Rovás on Omniglot

- (in Hungarian and English) Rovásírás (Gábor Hosszú)

- (in Hungarian) Kiszely István: A magyar nép őstörténete

- (in Hungarian) Learning Rovas

- (in Hungarian) The Living Rovas

- (in Hungarian) Hungarian Rovas Portal

- (in Hungarian) Szekely-Hungarian Rovas

- Szekely-Hungarian Rovas on RovasPedia

- Old Hungarian Unicode fonts

- ALPHABETUM by Juan José Marcos (commercial font)

- Noto Sans Old Hungarian

- Old Hungarian by Zsolt Sz. Sztupák

- OptimaModoki by Dare-demo Iie

- TWB01x SMP fonts by Thomas Buchleither (archived on 2019-07-17)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Old_Hungarian_script

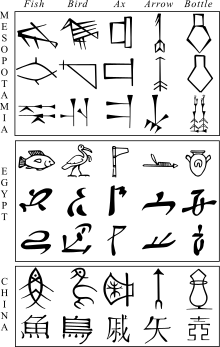

A writing system is a method of visually representing verbal communication, based on a script and a set of rules regulating its use. A writing system can be visually expressed through symbols and/or images such as Hieroglyphs or the Hieroglyphic Writing System.

While both writing and speech are useful in conveying messages, writing differs in also being a reliable form of information storage and transfer.[1] Writing systems require shared understanding between writers and readers of the meaning behind the sets of characters that make up a script. Without a mutual understanding of the meanings behind both writing and reading, a writing system can be rendered useless. Writing is usually recorded onto a durable medium, such as paper or electronic storage, although non-durable methods may also be used, such as writing on a computer display, on a blackboard, in sand, or by skywriting. Reading a text can be accomplished purely in the mind as an internal process, or expressed orally.

Writing systems can be placed into broad categories such as alphabets, syllabaries, or logographies, although any particular system may have attributes of more than one category. In the alphabetic category, a standard set of letters represent speech sounds. In a syllabary, each symbol correlates to a syllable or mora. In a logography, each character represents a semantic unit such as a word or morpheme. Abjads differ from alphabets in that vowels are not indicated, and in abugidas or alphasyllabaries each character represents a consonant–vowel pairing.

Alphabets typically use a set of less than 100 symbols to fully express a language, whereas syllabaries can have several hundred, and logographies can have thousands of symbols. Many writing systems also include a special set of symbols known as punctuation which is used to aid interpretation and help capture nuances and variations in the message's meaning that are communicated verbally by cues in timing, tone, accent, inflection or intonation.

Writing systems were preceded by proto-writing, which used pictograms, ideograms and other mnemonic symbols. Proto-writing lacked the ability to capture and express a full range of thoughts and ideas. The invention of writing systems, which dates back to the beginning of the Bronze Age in the late Neolithic Era of the late 4th millennium BC, enabled the accurate durable recording of human history in a manner that was not prone to the same types of error to which oral history is vulnerable. Soon after, writing provided a reliable form of long distance communication. With the advent of publishing, it provided the medium for an early form of mass communication.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Writing_system

No comments:

Post a Comment