A missionary, Rev. Robert P. Wilder, quoted in a contemporary New York Times article,[12] asserted that the cause of plague was native practices such as going bare-foot, the distrust of the natives about the government segregation camps; further, that houses have been shut up with corpses inside, and search parties have been going around to unearth them. The same article included reported rumours that the plague has been caused by grain hoarded for twenty years by the banias or grocers being sold in the market, while others felt it was Queen Victoria's curse for the daubing of her statue with tar.[13]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chapekar_brothers

Following the forced abdication of Reza Shah in 1941, the British came to believe that Zahedi was planning a general uprising in cooperation with German forces, and as one of the worst grain-hoarders, was responsible for widespread popular discontent.[5][6][7] He was arrested in his own office by Fitzroy Maclean, who details the adventure in his 1949 memoir Eastern Approaches. On searching Zahidi's bedroom Maclean found "a collection of automatic weapons of German manufacture, a good deal of silk underwear, some opium, an illustrated register of the prostitutes of Isfahan," and correspondence from a local German agent.[5] Zahedi was flown out of the country and interned in Palestine.[5]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fazlollah_Zahedi

The Irish Famine of 1740–1741 (Irish: Bliain an Áir, meaning the Year of Slaughter) in the Kingdom of Ireland, is estimated to have killed between 13% and 20% of the 1740 population of 2.4 million people, which was a proportionately greater loss than during the Great Famine of 1845–1852.[1][2][3]

The famine of 1740–1741 was due to extremely cold and then dry weather in successive years, resulting in food losses in three categories: a series of poor grain harvests, a shortage of milk, and frost damage to potatoes.[4] At this time, grains, particularly oats, were more important than potatoes as staples in the diet of most workers.[citation needed]

Deaths from mass starvation in 1740–1741 were compounded by an outbreak of fatal diseases. The cold and its effects extended across Europe, but mortality was higher in Ireland because both grain and potatoes failed. This is now considered by scholars to be the last serious cold period at the end of the Little Ice Age of about 1400–1800.[citation needed]

The famine of 1740–1741 is different from the Great Famine of the 19th century. By the mid-19th century, potatoes made up a greater portion of Irish diets, with adverse consequences when the crop failed, causing famine from 1845 to 1852. The Great Famine differed by "cause, scale and timing" from the Irish Famine of 1740–1741. It was caused by an oomycete infection which destroyed much of the potato crop for several years running, a crisis exacerbated by the laissez-faire policies of the ruling British government, continued exportation of food, insufficient relief and rigid government regulations.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Irish_Famine_(1740%E2%80%931741)

https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Building_Steam_With_a_Grain_of_Salt&redirect=no

Hoards are very common in the Urnfield culture. The custom is abandoned at the end of the Bronze Age. They were often deposited in rivers and wet places like swamps. As these spots were often quite inaccessible, they most probably represent gifts to the gods. Other hoards contain either broken or miscast objects that were probably intended for reuse by bronze smiths. As Late Urnfield hoards often contain the same range of objects as earlier graves, some scholars interpret hoarding as a way to supply personal equipment for the hereafter. In the river Trieux, Côtes du Nord, complete swords were found together with numerous antlers of red deer that may have had a religious significance as well.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Urnfield_culture#Hoards

Pocket gophers, commonly referred to simply as gophers, are burrowing rodents of the family Geomyidae.[2] The roughly 41 species[3] are all endemic to North and Central America.[4] They are commonly known for their extensive tunneling activities and their ability to destroy farms and gardens.

The name "pocket gopher" on its own may refer to any of a number of genera within the family Geomyidae. These are the "true" gophers, but several ground squirrels in the distantly related family Sciuridae are often called "gophers", as well. The origin of the word "gopher" is uncertain; the French gaufre, meaning waffle, has been suggested, on account of the gopher tunnels resembling the honeycomb-like pattern of holes in a waffle;[5] another suggestion is that the word is of Muskogean origin.[6]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gopher

The Boston bread riot was the last of a series of three riots by the poor of Boston in Massachusetts Bay Colony between 1710 and 1713, in response to food shortages and high bread prices. The riot ended with minimal casualties.

Riot

In the early 18th century, the city of Boston had very little arable land, and most grain had to be imported from surrounding towns or from abroad. It was common practice for the larger local grain merchants to hoard grain to drive up local prices, and to sell grain in more lucrative foreign markets such as Europe or the sugar plantations of the West Indies. On top of this, Queen Anne's War (1702–1713) interfered with foreign trade. By 1709, Boston was experiencing a serious food shortage and skyrocketing bread prices.

In April 1710, a group of men broke the rudder of a cargo ship belonging to merchant Andrew Belcher to stop its cargo of wheat from being shipped away and sold abroad. The next day, about 50 men attempted to force the ship's captain ashore, intending to loot the ship of its grain. They were arrested, but popular support for their cause resulted in them being released without charges.

In May 1713, a mob of more than 200 rioted on Boston Common, protesting high bread prices. The mob again attacked Belcher's ships, and this time they "broke into his warehouses looking for corn, and shot the lieutenant governor when he tried to interfere."[1]

See also

Notes

- Zinn, Howard. A People's History of the United States. 1st Harper Perennial edition, HarperCollins. New York, NY. 1995, p. 51

- 1713 riots

- Riots and civil disorder in Massachusetts

- Food riots

- History of Boston

- 18th century in Boston

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Boston_bread_riot

One-dollar bill (obverse) | |

| ISO 4217 | |

|---|---|

| Code | USD (numeric: 840) |

| Subunit | 0.01 |

| Unit | |

| Symbol | $, US$, U$ |

| Nickname | |

List | |

| Denominations | |

|---|---|

| Superunit | |

| 10 | Eagle |

| Subunit | |

| 1⁄10 | Dime |

| 1⁄100 | Cent |

| 1⁄1000 | Mill |

| Symbol | |

| Cent | ¢ |

| Mill | ₥ |

| Banknotes | |

| Freq. used | $1, $5, $10, $20, $50, $100 |

| Rarely used | $2 (still printed); $500, $1,000, $5,000, $10,000 (discontinued, still legal tender) |

| Coins | |

| Freq. used | 1¢, 5¢, 10¢, 25¢ |

| Rarely used | 50¢, $1 (still minted); 1⁄2¢, 2¢, 3¢, 20¢, $2.50, $3, $5, $10, $20 (discontinued, still legal tender) |

| Demographics | |

| Date of introduction | April 2, 1792[1] |

| Replaced | Continental currency Various foreign currencies, including: Pound sterling Spanish dollar |

| User(s) | see § Formal (11), § Informal (11) |

| Issuance | |

| Central bank | Federal Reserve |

| Website | federalreserve |

| Printer | Bureau of Engraving and Printing |

| Website | www |

| Mint | United States Mint |

| Website | usmint |

| Valuation | |

| Inflation | 5% |

| Source | [2], March 2023 |

| Method | CPI |

| Pegged by | see § Pegged currencies |

The United States dollar (symbol: $; code: USD; also abbreviated US$ to distinguish it from other dollar-denominated currencies; referred to as the dollar, U.S. dollar, American dollar, or colloquially buck) is the official currency of the United States and several other countries. The Coinage Act of 1792 introduced the U.S. dollar at par with the Spanish silver dollar, divided it into 100 cents, and authorized the minting of coins denominated in dollars and cents. U.S. banknotes are issued in the form of Federal Reserve Notes, popularly called greenbacks due to their predominantly green color.

The monetary policy of the United States is conducted by the Federal Reserve System, which acts as the nation's central bank.

The U.S. dollar was originally defined under a bimetallic standard of 371.25 grains (24.057 g) (0.7735 troy ounces) fine silver or, from 1837, 23.22 grains (1.505 g) fine gold, or $20.67 per troy ounce. The Gold Standard Act of 1900 linked the dollar solely to gold. From 1934, its equivalence to gold was revised to $35 per troy ounce. Since 1971, all links to gold have been repealed.[2]

The U.S. dollar became an important international reserve currency after the First World War, and displaced the pound sterling as the world's primary reserve currency by the Bretton Woods Agreement towards the end of the Second World War. The dollar is the most widely used currency in international transactions,[3] and a free-floating currency. It is also the official currency in several countries and the de facto currency in many others,[4][5] with Federal Reserve Notes (and, in a few cases, U.S. coins) used in circulation.

As of February 10, 2021, currency in circulation amounted to US$2.10 trillion, $2.05 trillion of which is in Federal Reserve Notes (the remaining $50 billion is in the form of coins and older-style United States Notes).[6]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_dollar

| Garnet | |

|---|---|

| |

| General | |

| Category | Nesosilicate |

| Formula (repeating unit) | The general formula X3Y2(SiO4)3 |

| IMA symbol | Grt[1] |

| Crystal system | Isometric |

| Crystal class | |

| Space group | Ia3d |

| Identification | |

| Color | virtually all colors, blue is rare |

| Crystal habit | Rhombic dodecahedron or cubic |

| Cleavage | Indistinct |

| Fracture | conchoidal to uneven |

| Mohs scale hardness | 6.5–7.5 |

| Luster | vitreous to resinous |

| Streak | White |

| Diaphaneity | Can form with any diaphaneity, translucent is common |

| Specific gravity | 3.1–4.3 |

| Polish luster | vitreous to subadamantine[2] |

| Optical properties | Single refractive, often anomalous double refractive[2] |

| Refractive index | 1.72–1.94 |

| Birefringence | None |

| Pleochroism | None |

| Ultraviolet fluorescence | variable |

| Other characteristics | variable magnetic attraction |

| Major varieties | |

| Pyrope | Mg3Al2Si3O12 |

| Almandine | Fe3Al2Si3O12 |

| Spessartine | Mn3Al2Si3O12 |

| Andradite | Ca3Fe2Si3O12 |

| Grossular | Ca3Al2Si3O12 |

| Uvarovite | Ca3Cr2Si3O12 |

Garnets ( /ˈɡɑːrnɪt/) are a group of silicate minerals that have been used since the Bronze Age as gemstones and abrasives.

All species of garnets possess similar physical properties and crystal forms, but differ in chemical composition. The different species are pyrope, almandine, spessartine, grossular (varieties of which are hessonite or cinnamon-stone and tsavorite), uvarovite and andradite. The garnets make up two solid solution series: pyrope-almandine-spessartine (pyralspite), with the composition range [Mg,Fe,Mn]3Al2(SiO4)3; and uvarovite-grossular-andradite (ugrandite), with the composition range Ca3[Cr,Al,Fe]2(SiO4)3.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Garnet

The Communist Party of the Soviet Union had never been happy with private agriculture and saw collectivization as the best remedy for the problem. Lenin claimed, "Small-scale production gives birth to capitalism and the bourgeoisie constantly, daily, hourly, with elemental force, and in vast proportions."[6] Apart from ideological goals, Joseph Stalin also wished to embark on a program of rapid heavy industrialization which required larger surpluses to be extracted from the agricultural sector in order to feed a growing industrial workforce and to pay for imports of machinery (by exporting grain).[7] Social and ideological goals would also be served through the mobilization of the peasants in a co-operative economic enterprise that would provide social services to the people and empower the state. Not only was collectivization meant to fund industrialization, but it was also a way for the Bolsheviks to systematically exterminate the Kulaks and peasants in general in a back-handed manner. Stalin was incredibly suspicious of the peasants, viewing them as a major threat to socialism. Stalin's use of the collectivization process served to not only address the grain shortages, but his greater concern over the peasants' willingness to conform to the collective farm system and state mandated grain acquisitions.[8] He viewed this as an opportunity to punish the Kulaks as a class by means of collectivization.

Despite the initial plans, collectivization, accompanied by the bad harvest of 1932–1933, did not live up to expectations. Between 1929 and 1932 there was a massive fall in agricultural production resulting in famine in the countryside. Stalin and the CPSU blamed the prosperous peasants, referred to as 'kulaks' (Russian: fist), who were organizing resistance to collectivization. Allegedly, many kulaks had been hoarding grain in order to speculate on higher prices, thereby sabotaging grain collection. Stalin resolved to eliminate them as a class. The methods Stalin used to eliminate the kulaks were dispossession, deportation, and execution. The term "Ural-Siberian Method" was coined by Stalin, the rest of the population referred to it as the "new method". Article 107 of the criminal code was the legal means by which the state acquired grain.[22]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Collectivization_in_the_Soviet_Union

The Soviet government responded to these acts by cutting off food rations to peasants and areas where there was opposition to collectivization, especially in Ukraine. For peasants that were unable to meet the grain quota, they were fined five-times the quota. If the peasant continued to be defiant the peasants' property and equipment would be confiscated by the state. If none of the previous measures were effective the defiant peasant would be deported or exiled. The practice was made legal in 1929 under Article 61 of the criminal code.[22] Many peasant families were forcibly resettled in Siberia and Kazakhstan into exile settlements, and most of them died on the way. Estimates suggest that about a million so-called 'kulak' families, or perhaps some 5 million people, were sent to forced labour camps.[50][51]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Collectivization_in_the_Soviet_Union

On August 7, 1932, the Decree about the Protection of Socialist Property proclaimed that the punishment for theft of kolkhoz or cooperative property was the death sentence, which "under extenuating circumstances" could be replaced by at least ten years of incarceration. With what some called the Law of Spikelets ("Закон о колосках"), peasants (including children) who hand-collected or gleaned grain in the collective fields after the harvest were arrested for damaging the state grain production. Martin Amis writes in Koba the Dread that 125,000 sentences were passed for this particular offence in the bad harvest period from August 1932 to December 1933.

During the Famine of 1932–33 it's estimated that 7.8–11 million people died from starvation.[52] The implication is that the total death toll (both direct and indirect) for Stalin's collectivization program was on the order of 12 million people.[51] It is said that in 1945, Joseph Stalin confided to Winston Churchill at Yalta that 10 million people died in the course of collectivization.[53]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Collectivization_in_the_Soviet_Union

Siberia

Since the second half of the 19th century, Siberia had been a major agricultural region within Russia, espеcially its southern territories (nowadays Altai Krai, Omsk Oblast, Novosibirsk Oblast, Kemerovo Oblast, Khakassia, Irkutsk Oblast). Stolypin's program of resettlement granted a lot of land for immigrants from elsewhere in the empire, creating a large portion of well-off peasants and stimulating rapid agricultural development in the 1910s. Local merchants exported large quantities of labelled grain, flour, and butter into central Russia and Western Europe.[54] In May 1931, a special resolution of the Western-Siberian Regional Executive Committee (classified "top secret") ordered the expropriation of property and the deportation of 40,000 kulaks to "sparsely populated and unpopulated" areas in Tomsk Oblast in the northern part of the Western-Siberian region.[55] The expropriated property was to be transferred to kolkhozes as indivisible collective property and the kolkhoz shares representing this forced contribution of the deportees to kolkhoz equity were to be held in the "collectivization fund of poor and landless peasants" (фонд коллективизации бедноты и батрачества).

It has since been perceived by historians such as Lynne Viola as a Civil War of the peasants against the Bolshevik Government and the attempted colonization of the countryside.[56]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Collectivization_in_the_Soviet_Union

Coordinates: 51.9000°N 37.9000°E

This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2014) |

The Central Black Earth Region, Central Chernozem Region or Chernozemie (Russian: Центрально-черноземная область, Центральная черноземная область, Центрально-черноземная полоса[1]) is a segment of the Eurasian Black Earth belt that lies within Central Russia and comprises Voronezh Oblast, Lipetsk Oblast, Belgorod Oblast, Tambov Oblast, Oryol Oblast and Kursk Oblast. Between 1928 and 1934, these regions were briefly united into Central Black Earth Oblast, with the centre in Voronezh.

The Black Earth Region is famous for its high quality soil, called Chernozem (Black Earth). Although its importance has been primarily agricultural, the Chernozem Region was developed by the Soviets as an industrial region based on iron ores of the Kursk Magnetic Anomaly.

The area contains a biosphere nature reserve called Central Black Earth Nature Reserve (42 km2 (16 sq mi)). It was created in 1935 within the Kursk and Belgorod oblasts. A prime specimen of forest steppe in Europe, the nature reserve consists of typical virgin land (tselina) steppes and deciduous forests.

Juozas Vareikis was the First Secretary of Communist Party's Regional Committee for the Central Black Earth Region (1928–1934).

History

On May 14, 1928, the All-Russian Central Executive Committee and Government of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic passed a directive on the formation of the Central Black Earth Oblast[2] using the territory of the former Voronezh, Kursk, Oryol and Tambov Governorate Governorates with its centre as the city of Voronezh.

On July 16, 1928 the composition of the Central Black Earth Oblast was determined and on July 30 of the same year its districts were founded. Later, from 1929 to 1933, these districts were revised several times.

On June 3, 1929 the centre of the region, Voronezh, was designated as an independent administrative unit directly subordinate to the regional Congress of Soviets and its executive committee.

On September 16, 1929 the Voronezh Okrug was abolished and its territory was split among the newly founded Stary Oskol and Usman Okrugs.

See also

References

- Agriculture in the Black Sea Region Archived October 31, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Central_Black_Earth_Region

Kulak (/ˈkuːlæk/; Russian: кула́к; plural: кулаки́, kulakí, 'fist' or 'tight-fisted'), also kurkul (Ukrainian: куркуль) or golchomag (Azerbaijani: qolçomaq, plural: qolçomaqlar), was the term which was used to describe peasants who owned over 8 acres (3.2 hectares) of land towards the end of the Russian Empire. In the early Soviet Union, particularly in Soviet Russia and Azerbaijan, kulak became a vague reference to property ownership among peasants who were considered hesitant allies of the Bolshevik Revolution.[1] In Ukraine during 1930–1931, there also existed a term of pidkurkulnyk (almost wealthy peasant); these were considered "sub-kulaks".[2]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kulak

The Stolypin agrarian reforms were a series of changes to Imperial Russia's agricultural sector instituted during the tenure of Prime Minister Pyotr Stolypin. Most, if not all, of these reforms were based on recommendations from a committee known as the "Needs of Agricultural Industry Special Conference," which was held in Russia between 1901–1903 during the tenure of Minister of Finance Sergei Witte.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stolypin_reform

The terms enemy of the people and enemy of the nation are designations for the political opponents and for the social-class opponents of the power group within a larger social unit, who, thus identified, can be subjected to political repression.[1] In political praxis, the term enemy of the people implies that political opposition to the ruling power group renders the people in opposition into enemies acting against the interests of the greater social unit, e.g. the political party, society, the nation, etc.

In the 20th century, the politics of the Soviet Union (1922–1991) much featured the term enemy of the people to discredit any opposition, especially during the régime of Stalin (r. 1924–1953), when it was often applied to Trotsky.[2][3] In the 21st century, the former U.S. president Donald Trump (r. 2017–2021) regularly used the enemy of the people term against critical politicians and journalists.[4][5]

Like the term enemy of the state, the term enemy of the people originated and derives from the Latin: hostis publicus, a public enemy of the Roman Empire. In literature, the term enemy of the people features in the title of the stageplay An Enemy of the People (1882), by Henrik Ibsen, and is a theme in the stageplay Coriolanus (1605), by William Shakespeare.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Enemy_of_the_people

https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Class_enemies&redirect=no

Kulak originally referred to former peasants in the Russian Empire who became wealthier during the Stolypin reform of 1906 to 1914, which aimed to reduce radicalism amongst the peasantry and produce profit-minded, politically conservative farmers. During the Russian Revolution, kulak was used to chastise peasants who withheld grain from the Bolsheviks.[3] According to Marxist–Leninist political theories of the early 20th century, the kulaks were considered class enemies of the poorer peasants.[4][5] Vladimir Lenin described them as "bloodsuckers, vampires, plunderers of the people and profiteers, who fatten themselves during famines",[6] declaring revolution against them to liberate poor peasants, farm laborers, and proletariat (the much smaller class of urban and industrial workers).[7]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kulak

Soviet terminology divided the Russian peasants into three broad categories:

- Bednyak, or poor peasants.

- Serednyak, or mid-income peasants.

- Kulak, the higher-income farmers who had larger farms.

In addition, they had a category of batrak, landless seasonal agricultural workers for hire.[4]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kulak

The Red Terror (Russian: Красный террор, romanized: krasnyj terror) in Soviet Russia was a campaign of political repression and executions which was carried out by the Bolsheviks, chiefly through the Cheka, the Bolshevik secret police. It officially started in early September 1918 and lasted until 1922.[2][3]

Arising after assassination attempts on Vladimir Lenin and Petrograd Cheka leader Moisei Uritsky in retaliation for Bolshevik atrocities, the latter of which was successful, the Red Terror was modeled on the Reign of Terror of the French Revolution,[4] and sought to eliminate political dissent, opposition, and any other threat to Bolshevik power.[5] More broadly, the term is usually applied to Bolshevik political repression throughout the Civil War (1917–1922),[6][7][8] as distinguished from the White Terror carried out by the White Army (Russian and non-Russian groups opposed to Bolshevik rule) against their political enemies, including the Bolsheviks.

| Part of the Russian Civil War | |

Propaganda poster in Petrograd, 1918: "Death to the Bourgeoisie and its lapdogs – Long live the Red Terror"[1] | |

| Native name | Красный террор / Красный терроръ Krasnyy terror |

|---|---|

| Date | August 1918 – February 1922 |

| Duration | 3–4 years |

| Location | Soviet Russia |

| Motive | Political repression |

| Target | Anti-Bolshevik groups, clergy, rival socialists, counter-revolutionaries, peasants, and dissidents |

| Organized by | Cheka |

| Deaths | 50,000–200,000 (possibly more) |

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Red_Terror

| Mass repression in the Soviet Union |

|---|

| Economic repression |

| Political repression |

| Ideological repression |

| Ethnic repression |

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Red_Terror

|

| ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||

|

| ||||||||

|

||||||||

|

| ||||||||

|

||||||||

|

| ||||||||

|

||||||||

|

| ||||||||

|

||||||||

|

Russian Civil War | ||||||||

|

||||||||

|

| ||||||||

|

||||||||

|

| ||||||||

|

||||||||

The White movement (Russian: pre–1918 Бѣлое движеніе / post–1918 Белое движение, tr. Beloye dvizheniye, IPA: [ˈbʲɛləɪ dvʲɪˈʐenʲɪɪ])[a] also known as the Whites (Бѣлые / Белые, Beliye), was a loose confederation of anti-communist forces that fought the communist Bolsheviks, also known as the Reds, in the Russian Civil War (1917–1923) and that to a lesser extent continued operating as militarized associations of rebels both outside and within Russian borders in Siberia until roughly World War II (1939–1945). The movement's military arm was the White Army (Бѣлая армія / Белая армия, Belaya armiya), also known as the White Guard (Бѣлая гвардія / Белая гвардия, Belaya gvardiya) or White Guardsmen (Бѣлогвардейцы / Белогвардейцы, Belogvardeytsi).

During the Russian Civil War, the White movement functioned as a big-tent political movement representing an array of political opinions in Russia united in their opposition to the Bolsheviks—from the republican-minded liberals and Kerenskyite social democrats on the left through monarchists and supporters of a united multinational Russia to the ultra-nationalist Black Hundreds on the right.

Following the military defeat of the Whites, remnants and continuations of the movement remained in several organizations, some of which only had narrow support, enduring within the wider White émigré overseas community until after the fall of the European communist states in the Eastern European Revolutions of 1989 and the subsequent dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1990–1991. This community-in-exile of anti-communists often divided into liberal and the more conservative segments, with some still hoping for the restoration of the Romanov dynasty.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/White_movement

In the Russian context after 1917, "White" had three main connotations which were:

- Political contra-distinction to "the Reds", whose Red Army supported the Bolshevik government.

- Historical reference to absolute monarchy, specifically recalling Russia's first Tsar, Ivan III (reigned 1462–1505),[5] at a period when some styled the ruler of Muscovy Albus Rex ("the White King").[6]

- The white uniforms of Imperial Russia worn by some White Army soldiers.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/White_movement

|

| ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||

|

| ||||||||

|

||||||||

|

| ||||||||

|

||||||||

|

| ||||||||

|

||||||||

|

| ||||||||

|

||||||||

|

Russian Civil War | ||||||||

|

||||||||

|

| ||||||||

|

||||||||

|

| ||||||||

|

||||||||

The White movement (Russian: pre–1918 Бѣлое движеніе / post–1918 Белое движение, tr. Beloye dvizheniye, IPA: [ˈbʲɛləɪ dvʲɪˈʐenʲɪɪ])[a] also known as the Whites (Бѣлые / Белые, Beliye), was a loose confederation of anti-communist forces that fought the communist Bolsheviks, also known as the Reds, in the Russian Civil War (1917–1923) and that to a lesser extent continued operating as militarized associations of rebels both outside and within Russian borders in Siberia until roughly World War II (1939–1945). The movement's military arm was the White Army (Бѣлая армія / Белая армия, Belaya armiya), also known as the White Guard (Бѣлая гвардія / Белая гвардия, Belaya gvardiya) or White Guardsmen (Бѣлогвардейцы / Белогвардейцы, Belogvardeytsi).

During the Russian Civil War, the White movement functioned as a big-tent political movement representing an array of political opinions in Russia united in their opposition to the Bolsheviks—from the republican-minded liberals and Kerenskyite social democrats on the left through monarchists and supporters of a united multinational Russia to the ultra-nationalist Black Hundreds on the right.

Following the military defeat of the Whites, remnants and continuations of the movement remained in several organizations, some of which only had narrow support, enduring within the wider White émigré overseas community until after the fall of the European communist states in the Eastern European Revolutions of 1989 and the subsequent dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1990–1991. This community-in-exile of anti-communists often divided into liberal and the more conservative segments, with some still hoping for the restoration of the Romanov dynasty.

Structure and ideology

In the Russian context after 1917, "White" had three main connotations which were:

- Political contra-distinction to "the Reds", whose Red Army supported the Bolshevik government.

- Historical reference to absolute monarchy, specifically recalling Russia's first Tsar, Ivan III (reigned 1462–1505),[5] at a period when some styled the ruler of Muscovy Albus Rex ("the White King").[6]

- The white uniforms of Imperial Russia worn by some White Army soldiers.

Ideology

Above all, the White movement emerged as opponents of the Red Army.[7] The White Army had the stated aim to keep to reverse the October Revolution and remove the Bolsheviks from power before a constituent assembly (dissolved by the Bolsheviks in January 1918) can be convened.[8] They worked to remove Soviet organizations and functionaries in White-controlled territory.[9]

Overall, the White Army was nationalistic[10] and rejected ethnic particularism and separatism.[11] The White Army generally believed in a united multinational Russia and opposed separatists who wanted to create nation-states.[12] British parliamentary influential leader Winston Churchill (1874–1965) personally warned General Anton Denikin (1872–1947), formerly of the Imperial Army and later a major White military leader, whose forces effected pogroms and persecutions against the Jews:

[M]y task in winning support in Parliament for the Russian Nationalist cause will be infinitely harder if well-authenticated complaints continue to be received from Jews in the zone of the Volunteer Armies.[13]

Aside from being anti-Bolshevik and anti-communist[14] and patriotic, the Whites had no set ideology or main leader.[15] The White Armies did acknowledge a single provisional head of state in a Supreme Governor of Russia in a Provisional All-Russian Government, but this post was prominent only under the leadership in the war campaigns during 1918–1920 of Admiral Alexander Kolchak, formerly of the previous Russian Imperial Navy.[16]

The movement had no set foreign policy. Whites differed on policies toward the German Empire in its extended occupation of western Russia, the Baltic states, Poland and Ukraine on the Eastern Front in the closing days of the World War, debating whether or not to ally with it. The Whites wanted to keep from alienating any potential supporters and allies and thus saw an exclusively monarchist position as a detriment to their cause and recruitment. White-movement leaders, such as Anton Denikin, advocated for Russians to create their own government, claiming the military could not decide in Russians' steads.[17] Admiral Alexander Kolchak succeeded in creating a temporary wartime government in Omsk, acknowledged by most other White leaders, but it ultimately disintegrated after Bolshevik military advances.[18]

Some warlords who were aligned with the White movement, such as Grigory Semyonov and Roman Ungern von Sternberg, did not acknowledge any authority but their own. Consequently, the White movement had no unifying political convictions, as members could be monarchists, republicans,[19] rightists, or Kadets.[20] Among White Army leaders, neither General Lavr Kornilov nor General Anton Denikin were monarchists, yet General Pyotr Nikolayevich Wrangel was a monarchist willing to soldier for a republican Russian government. Moreover, other political parties supported the anti-Bolshevik White Army, among them the Socialist Revolutionary Party, and others who opposed Lenin's Bolshevik coup in October 1917. Depending on the time and place, those White Army supporters might also exchange right-wing allegiance for allegiance to the Red Army.

Unlike the Bolsheviks, the White Armies did not share a single ideology, methodology, or political goal. They were led by conservative generals with different agendas and methods, and for the most part they operated quite independently of each other, with little coordination or cohesion. The composition and command structure of White armies also varied, some containing hardened veterans of World War I, others more recent volunteers. These differences and divisions, along with their inability to offer an alternative government and win popular support, prevented the White armies from winning the Civil War.[21][22]

Structure

White Army

The Volunteer Army in South Russia became the most prominent and the largest of the various and disparate White forces.[7] Starting off as a small and well-organized military in January 1918, the Volunteer Army soon grew. The Kuban Cossacks joined the White Army and conscription of both peasants and Cossacks began. In late February 1918, 4,000 soldiers under the command of General Aleksei Kaledin were forced to retreat from Rostov-on-Don due to the advance of the Red Army. In what became known as the Ice March, they traveled to Kuban in order to unite with the Kuban Cossacks, most of whom did not support the Volunteer Army. In March, 3,000 men under the command of General Viktor Pokrovsky joined the Volunteer Army, increasing its membership to 6,000, and by June to 9,000. In 1919 the Don Cossacks joined the Army. In that year between May and October, the Volunteer Army grew from 64,000 to 150,000 soldiers and was better supplied than its Red counterpart.[23] The White Army's rank-and-file comprised active anti-Bolsheviks, such as Cossacks, nobles, and peasants, as conscripts and as volunteers.

The White movement had access to various naval forces, both seagoing and riverine, especially the Black Sea Fleet.

Aerial forces available to the Whites included the Slavo-British Aviation Corps (S.B.A.C.).[24] The Russian ace Alexander Kazakov operated within this unit.

Administration

The White movement's leaders and first members[25] came mainly from the ranks of military officers. Many came from outside the nobility, such as generals Mikhail Alekseev and Anton Denikin, who originated in serf families, or General Lavr Kornilov, a Cossack.

The White generals never mastered administration;[26] they often utilized "prerevolutionary functionaries" or "military officers with monarchististic inclinations" for administering White-controlled regions.[27]

The White Armies were often lawless and disordered.[8] Also, White-controlled territories had multiple different and varying currencies with unstable exchange-rates. The chief currency, the Volunteer Army's ruble, had no gold backing.[28]

Ranks and insignia

Theatres of operation

The Whites and the Reds fought the Russian Civil War from November 1917 until 1921, and isolated battles continued in the Far East until 1923. The White Army—aided by the Allied forces (Triple Entente) from countries such as Japan, the United Kingdom, France, Greece, Italy and the United States and (sometimes) the Central Powers forces such as Germany and Austria-Hungary—fought in Siberia, Ukraine, and the Crimea. They were defeated by the Red Army due to military and ideological disunity, as well as the determination and increasing unity of the Red Army.

The White Army operated in three main theatres:

Southern front

White organising in the South started on 15 November 1917, (Old Style) under General Mikhail Alekseev (1857–1918). In December 1917, General Lavr Kornilov took over the military command of the newly named Volunteer Army until his death in April 1918, after which General Anton Denikin took over, becoming head of the "Armed Forces of the South of Russia" in January 1919.

The Southern Front featured massive-scale operations and posed the most dangerous threat to the Bolshevik Government. At first it depended entirely upon volunteers in Russia proper, mostly the Cossacks, among the first to oppose the Bolshevik Government. On 23 June 1918, the Volunteer Army (8,000–9,000 men) began its so-called Second Kuban Campaign with support from Pyotr Krasnov. By September, the Volunteer Army comprised 30,000 to 35,000 members, thanks to mobilization of the Kuban Cossacks gathered in the North Caucasus. Thus, the Volunteer Army took the name of the Caucasus Volunteer Army. On 23 January 1919, the Volunteer Army under Denikin oversaw the defeat of the 11th Soviet Army and then captured the North Caucasus region. After capturing the Donbas, Tsaritsyn and Kharkiv in June, Denikin's forces launched an attack towards Moscow on 3 July, (N.S.). Plans envisaged 40,000 fighters under the command of General Vladimir May-Mayevsky storming the city.

After General Denikin's attack upon Moscow failed in 1919, the Armed Forces of the South of Russia retreated. On 26 and 27 March 1920, the remnants of the Volunteer Army evacuated from Novorossiysk to the Crimea, where they merged with the army of Pyotr Wrangel.

Eastern (Siberian) front

The Eastern Front started in spring 1918 as a secret movement among army officers and right-wing socialist forces. In that front, they launched an attack in collaboration with the Czechoslovak Legions, who were then stranded in Siberia by the Bolshevik Government, who had barred them from leaving Russia, and with the Japanese, who also intervened to help the Whites in the east. Admiral Alexander Kolchak headed the eastern White Army and a provisional Russian government. Despite some significant success in 1919, the Whites were defeated being forced back to Far Eastern Russia, where they continued fighting until October 1922. When the Japanese withdrew, the Soviet army of the Far Eastern Republic retook the territory. The Civil War was officially declared over at this point, although Anatoly Pepelyayev still controlled the Ayano-Maysky District at that time. Pepelyayev's Yakut revolt, which concluded on 16 June 1923, represented the last military action in Russia by a White Army. It ended with the defeat of the final anti-communist enclave in the country, signalling the end of all military hostilities relating to the Russian Civil War.

Northern and Northwestern fronts

Headed by Nikolai Yudenich, Evgeni Miller, and Anatoly Lieven, the White forces in the North demonstrated less co-ordination than General Denikin's Army of Southern Russia. The Northwestern Army allied itself with Estonia, while Lieven's West Russian Volunteer Army sided with the Baltic nobility. Authoritarian support led by Pavel Bermondt-Avalov and Stanisław Bułak-Bałachowicz played a role as well. The most notable operation on this front, Operation White Sword, saw an unsuccessful advance towards the Russian capital of Petrograd in the autumn of 1919.

Post-Civil War

The defeated anti-Bolshevik Russians went into exile, congregating in Belgrade, Berlin, Paris, Harbin, Istanbul, and Shanghai. They established military and cultural networks that lasted through World War II (1939–1945), e.g., the Russian community in Harbin and the Russian community in Shanghai. Afterward, the White Russians' anti-Communist activists established a home base in the United States, to which numerous refugees emigrated.

Moreover, in the 1920s and the 1930s the White Movement established organisations outside Russia, which were meant to depose the Soviet Government with guerrilla warfare, e.g., the Russian All-Military Union, the Brotherhood of Russian Truth, and the National Alliance of Russian Solidarists, a far-right anticommunist organization founded in 1930 by a group of young White emigres in Belgrade, Yugoslavia. Some White émigrés adopted pro-Soviet sympathies and were termed "Soviet patriots". These people formed organizations such as the Mladorossi, the Eurasianists, and the Smenovekhovtsy. A Russian cadet corps was established to prepare the next generation of anti-Communists for the "spring campaign"—a hopeful term denoting a renewed military campaign to reclaim Russia from the Soviet Government. In any event, many cadets volunteered to fight for the Russian Corps during the Second World War, when some White Russians participated in the Russian Liberation Movement.[29]

After the war, active anti-Soviet combat was almost exclusively continued by the National Alliance of Russian Solidarists. Other organizations either dissolved, or began concentrating exclusively on self-preservation and/or educating the youth. Various youth organizations, such as the Russian Scouts-in-Exteris, promoted providing children with a background in pre-Soviet Russian culture and heritage. Some supported Zog I of Albania during the 1920s and a few independently served with the Nationalists during the Spanish Civil War. White Russians also served alongside the Soviet Red Army during the Soviet invasion of Xinjiang and the Islamic rebellion in Xinjiang in 1937.

Prominent people

- Mikhail Alekseyev

- Vladimir Antonov

- Nicholas Savich Bakulin

- Pavel Bermondt-Avalov

- Stanisław Bułak-Bałachowicz

- Anton Denikin

- Mikhail Diterikhs

- Mikhail Drozdovsky

- Alexander Dutov

- Dmitrii Fedotoff-White

- Ivan Ilyin

- Nikolay Iudovich Ivanov

- Alexey Kaledin

- Vladimir Kappel

- Alexander Kolchak

- Lavr Kornilov

- Pyotr Krasnov

- Mikhail Kvetsinsky

- Alexander Kutepov

- Anatoly Lieven

- Konstantin Mamontov

- Sergey Markov

- Vladimir May-Mayevsky

- Evgeny Miller

- Konstantin Petrovich Nechaev

- Viktor Pokrovsky

- Leonid Punin

- Aleksandr Rodzyanko

- Grigory Semyonov

- Andrei Shkuro

- Roman von Ungern-Sternberg

- Pyotr Nikolayevich Wrangel

- Sergei Wojciechowski

- Nikolai Yudenich

- Vladimir Kappel

Related movements

After the February Revolution, in western Russia, Finland, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania declared themselves independent, but they had substantial Communist or Russian military presence. Civil wars followed, wherein the anti-communist side may be referred to as White Armies, e.g. the White Guard-led, partially conscripted army in Finland (valkoinen armeija) who fought against Soviet Russia-sponsored Red Guards. However, since they were nationalists, their aims were substantially different from the Russian White Army proper; for instance, Russian White generals never explicitly supported Finnish independence. The defeat of the Russian White Army made the point moot in this dispute. The countries remained independent and governed by non-Communist governments.

See also

- Russian State (1918–1920)

- 1st Infantry Brigade (South Africa)

- Allied intervention in the Russian Civil War

- Basmachi movement

- Czechoslovak Legions

- Estonian War of Independence

- Finnish Civil War

- Grand Orient of Russia's Peoples

- Great Siberian Ice March

- Italian Legione Redenta

- Russian All-Military Union

- Russian diaspora

- Red Terror

- Soviet–Ukrainian War

- White Terror (Russia)

- Ukrainian War of Independence

Notes

- The old spelling was retained by the Whites to differentiate from the Reds.

References

Footnotes

Then there occurred another story which has become traumatic, this one for the Russian nationalist psyche. At the end of the year 1918, after the Russian Revolution, the Chinese merchants in the Russian Far East demanded the Chinese government to send troops for their protection, and Chinese troops were sent to Vladivostok to protect the Chinese community: about 1600 soldiers and 700 support personnel.

It was Ivan III (1462–1505) who is well known as the first one to present himself as a tsar to foreigners, though it must be accepted that his use of the title was very sparse.

[...] the brief mention that the Muscovite ruler is by some called 'the White King' ('albus rex').

Soon after landing we started to recruit for the Slavo-British Aviation Corps (S.B.A.C.) [...].

- [1] Archived 2018-12-10 at the Wayback Machine Oleg Beyda, 'Iron Cross of the Wrangel's Army': Russian Emigrants as Interpreters in the Wehrmacht, Journal of Slavic Military Studies 27, no. 3 (2014): 430–448.

Bibliography

- Kenez, Peter (1980). "The Ideology of the White Movement". Soviet Studies. 32 (32): 58–83. doi:10.1080/09668138008411280.

- Kenez, Peter (1977). Civil War in South Russia, 1919–1920: The Defeat of the Whites. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Kenez, Peter (1971). Civil War in South Russia, 1918: The First Year of the Volunteer Army. Berkeley: University of California Press.

External links

- Anti-Bolshevik Russia in pictures

- Museum and Archives of the White Movement

- (in Russian) Memory and Honour Association

- (in Russian) History of the White Movement

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/White_movement

Republic of Belarus

| |

|---|---|

| Anthem: Дзяржаўны гімн Рэспублікі Беларусь (Belarusian) Dziaržaŭny Himn Respubliki Biełaruś Государственный гимн Республики Беларусь (Russian) Gosudarstvennyy gimn Respubliki Belarus "State Anthem of the Republic of Belarus" | |

| Capital and largest city | Minsk 53°55′N 27°33′E |

| Official languages | |

| Recognized minority languages | |

| Ethnic groups (2019)[1] |

|

| Religion (2020)[2] |

|

| Demonym(s) | Belarusian |

| Government | Unitary presidential republic under an authoritarian dictatorship[3][4] |

| Alexander Lukashenko (disputed)[5][6] | |

| Roman Golovchenko[7] | |

| Legislature | National Assembly |

| Council of the Republic | |

| House of Representatives | |

| Formation | |

| 987 | |

| 10th century | |

| 1236 | |

| 9 March 1918 | |

| 25 March 1918 | |

| 27 July 1990 | |

• Independence from USSR | 25 August 1991 |

| 15 March 1994 | |

| 8 December 1999 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 207,595 km2 (80,153 sq mi) (84th) |

• Water (%) | 1.4% (2.830 km2 or 1.093 sq mi)b |

| Population | |

• 2022 estimate | 9,255,524[8] (96th) |

• Density | 45.8/km2 (118.6/sq mi) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2022 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2022 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2019) | low |

| HDI (2021) | very high · 60th |

| Currency | Belarusian ruble (BYN) |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (MSK[12]) |

| Date format | dd.mm.yyyy |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +375 |

| ISO 3166 code | BY |

| Internet TLD | |

Website belarus.by | |

| |

Belarus,[b] officially the Republic of Belarus,[c] is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by Russia to the east and northeast, Ukraine to the south, Poland to the west, and Lithuania and Latvia to the northwest. Covering an area of 207,600 square kilometres (80,200 sq mi) and with a population of 9.2 million, Belarus is the 13th-largest and the 20th-most populous country in Europe. The country has a hemiboreal climate and is administratively divided into seven regions. Minsk is the capital and largest city.

Between the medieval period and the 20th century, different states at various times controlled the lands of modern-day Belarus, including Kievan Rus', the Principality of Polotsk, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, and the Russian Empire. In the aftermath of the Russian Revolution in 1917, different states arose competing for legitimacy amid the Civil War, ultimately ending in the rise of the Byelorussian SSR, which became a founding constituent republic of the Soviet Union in 1922. After the Polish-Soviet War, Belarus lost almost half of its territory to Poland. Much of the borders of Belarus took their modern shape in 1939, when some lands of the Second Polish Republic were reintegrated into it after the Soviet invasion of Poland, and were finalized after World War II.[14][15][16] During World War II, military operations devastated Belarus, which lost about a quarter of its population and half of its economic resources.[17] The republic was home to a widespread and diverse anti-Nazi insurgent movement which dominated politics until well into the 1970s, overseeing Belarus' transformation from an agrarian to industrial economy. In 1945, the Byelorussian SSR became a founding member of the United Nations, along with the Soviet Union.

The parliament of the republic proclaimed the sovereignty of Belarus on 27 July 1990, and during the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Belarus declared independence on 25 August 1991.[18] Following the adoption of a new constitution in 1994, Alexander Lukashenko was elected Belarus's first president in the country's first and only free election after independence, serving as president ever since.[19] Lukashenko heads a highly centralized authoritarian government.[20][4] Belarus ranks low in international measurements of freedom of the press and civil liberties. It has continued a number of Soviet-era policies, such as state ownership of large sections of the economy. In 2000, Belarus and Russia signed a treaty for greater cooperation, forming the Union State.

Belarus is a developing country, ranking 60th on the Human Development Index.[21] The country has been a member of the United Nations since its founding and has joined the CIS, the CSTO, the EAEU, the OSCE, and the Non-Aligned Movement. It has shown no aspirations of joining the European Union but nevertheless maintains a bilateral relationship with the bloc and also participates in two EU projects, the Baku Initiative and the Eastern Partnership. Belarus suspended its participation in the latter on 28 June 2021, after the EU imposed more sanctions against the country.[22][23]

Etymology

The name Belarus is closely related with the term Belaya Rus', i.e., White Rus'. There are several claims to the origin of the name White Rus'.[24] An ethno-religious theory suggests that the name used to describe the part of old Ruthenian lands within the Grand Duchy of Lithuania that had been populated mostly by Slavs who had been Christianized early, as opposed to Black Ruthenia, which was predominantly inhabited by pagan Balts.[25] An alternative explanation for the name comments on the white clothing worn by the local Slavic population.[24] A third theory suggests that the old Rus' lands that were not conquered by the Tatars (i.e., Polotsk, Vitebsk and Mogilev) had been referred to as White Rus'.[24] A fourth theory suggests that the color white was associated with the west, and Belarus was the western part of Rus in the 9th to 13th centuries.[26]

The name Rus is often conflated with its Latin forms Russia and Ruthenia, thus Belarus is often referred to as White Russia or White Ruthenia. The name first appeared in German and Latin medieval literature; the chronicles of Jan of Czarnków mention the imprisonment of Lithuanian grand duke Jogaila and his mother at "Albae Russiae, Poloczk dicto" in 1381.[27] The first known use of White Russia to refer to Belarus was in the late-16th century by Englishman Sir Jerome Horsey, who was known for his close contacts with the Russian royal court.[28] During the 17th century, the Russian tsars used White Rus to describe the lands added from the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.[29]

The term Belorussia (Russian: Белору́ссия, the latter part similar but spelled and stressed differently from Росси́я, Russia) first rose in the days of the Russian Empire, and the Russian Tsar was usually styled "the Tsar of All the Russias", as Russia or the Russian Empire was formed by three parts of Russia—the Great, Little, and White.[30] This asserted that the territories are all Russian and all the peoples are also Russian; in the case of the Belarusians, they were variants of the Russian people.[31]

After the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917, the term White Russia caused some confusion, as it was also the name of the military force that opposed the red Bolsheviks.[32] During the period of the Byelorussian SSR, the term Byelorussia was embraced as part of a national consciousness. In western Belarus under Polish control, Byelorussia became commonly used in the regions of Białystok and Grodno during the interwar period.[33]

The term Byelorussia (its names in other languages such as

English being based on the Russian form) was only used officially until

1991. Officially, the full name of the country is Republic of Belarus (Рэспубліка Беларусь, Республика Беларусь, Respublika Belarus ![]() listen (help·info)).[34][35] In Russia, the usage of Belorussia is still very common.[36]

listen (help·info)).[34][35] In Russia, the usage of Belorussia is still very common.[36]

In Lithuanian, besides Baltarusija (White Russia), Belarus is also called Gudija.[37][38] The etymology of the word Gudija is not clear. By one hypothesis the word derives from the Old Prussian name Gudwa, which, in turn, is related to the form Żudwa, which is a distorted version of Sudwa, Sudovia. Sudovia, in its turn, is one of the names of the Yotvingians. Another hypothesis connects the word with the Gothic Kingdom that occupied parts of the territory of modern Belarus and Ukraine in the 4th and 5th centuries. The self-naming of Goths was Gutans and Gytos, which are close to Gudija. Yet another hypothesis is based on the idea that Gudija in Lithuanian means "the other" and may have been used historically by Lithuanians to refer to any people who did not speak Lithuanian.[39]

History

Early history

From 5000 to 2000 BC, the Bandkeramik predominated in what now constitutes Belarus, and the Cimmerians as well as other pastoralists roamed through the area by 1,000 BC. The Zarubintsy culture later became widespread at the beginning of the 1st millennium. In addition, remains from the Dnieper–Donets culture were found in Belarus and parts of Ukraine.[40] The region was first permanently settled by Baltic tribes in the 3rd century. Around the 5th century, the area was taken over by the Slavs. The takeover was partially due to the lack of military coordination of the Balts, but their gradual assimilation into Slavic culture was peaceful in nature.[41] Invaders from Asia, among whom were the Huns and Avars, swept through c. 400–600 AD, but were unable to dislodge the Slavic presence.[42]

Kievan Rus'

In the 9th century the territory of modern Belarus became part of Kievan Rus', a vast East Slavic state ruled by the Rurikid dynasty. Upon the death of Kievan Rus' ruler Yaroslav I the Wise in 1054, the state split into independent principalities.[43] The Battle on the Nemiga River in 1067 was one of the more notable events of the period, the date of which is considered the founding date of Minsk.

Many early Rus' principalities were virtually razed or severely affected by a major Mongol invasion in the 13th century, but the lands of modern-day Belarus avoided the brunt of the invasion and eventually joined the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.[44] There are no sources of military seizure, but the annals affirm the alliance and united foreign policy of Polotsk and Lithuania for decades.[45] Trying to avoid the Tatar Yoke, the Principality of Minsk sought protection from Lithuanian princes further north and in 1242, the Principality of Minsk became a part of the expanding Grand Duchy of Lithuania.

Incorporation into the Grand Duchy of Lithuania resulted in an economic, political and ethno-cultural unification of Belarusian lands.[46] Of the principalities held by the duchy, nine of them were settled by a population that would eventually become the Belarusians.[47] During this time, the duchy was involved in several military campaigns, including fighting on the side of Poland against the Teutonic Knights at the Battle of Grunwald in 1410; the joint victory allowed the duchy to control the northwestern borderlands of Eastern Europe.[48]

The Muscovites, led by Ivan III of Moscow, began military campaigns in 1486 in an attempt to incorporate the former lands of Kievan Rus', specifically the territories of modern-day Belarus, Russia and Ukraine.[49]

Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

On 2 February 1386, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the Kingdom of Poland were joined in a personal union through a marriage of their rulers.[50] This union set in motion the developments that eventually resulted in the formation of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, created in 1569 by the Union of Lublin.[51][52]

The Lithuanian nobles were forced to seek rapprochement with the Poles because of a potential threat from Muscovy. To strengthen their independence within the format of the union, three editions of the Statutes of Lithuania were issued in the second half of the 16th century. The third Article of the Statutes established that all lands of the duchy will be eternally within the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and never enter as a part of other states. The Statutes allowed the right to own land only to noble families of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Anyone from outside the duchy gaining rights to a property would actually own it only after swearing allegiance to the Grand Duke of Lithuania (a title dually held by the King of Poland). These articles were aimed to defend the rights of the Lithuanian nobility within the duchy against Polish and other nobles of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.[citation needed]

In the years following the union, the process of gradual Polonization of both Lithuanians and Ruthenians gained steady momentum. In culture and social life, both the Polish language and Catholicism became dominant, and in 1696, Polish replaced Ruthenian as the official language, with Ruthenian being banned from administrative use.[53] However, the Ruthenian peasants continued to speak their native language. Also, the Belarusian Byzantine Catholic Church was formed by the Poles in order to bring Orthodox Christians into the See of Rome. The Belarusian church entered into a full communion with the Latin Church through the Union of Brest in 1595, while keeping its Byzantine liturgy in the Church Slavonic language.

The Statutes were initially issued in the Ruthenian language alone and later also in Polish. Around 1840 the Statutes were banned by the Russian tsar following the November Uprising. Ukrainian lands used them until 1860s.[citation needed]

Russian Empire

The union between Poland and Lithuania ended in 1795 with the Third Partition of Poland by Imperial Russia, Prussia, and Austria.[54] The Belarusian territories acquired by the Russian Empire under the reign of Catherine II[55] were included into the Belarusian Governorate (Russian: Белорусское генерал-губернаторство) in 1796 and held until their occupation by the German Empire during World War I.[56]

Under Nicholas I and Alexander III the national cultures were repressed. Policies of Polonization[57] changed by Russification,[58] which included the return to Orthodox Christianity of Belarusian Uniates. Belarusian language was banned in schools while in neighboring Samogitia primary school education with Samogitian literacy was allowed.[59]

In a Russification drive in the 1840s, Nicholas I prohibited use of the Belarusian language in public schools, campaigned against Belarusian publications and tried to pressure those who had converted to Catholicism under the Poles to reconvert to the Orthodox faith. In 1863, economic and cultural pressure exploded in a revolt, led by Konstanty Kalinowski (also known as Kastus). After the failed revolt, the Russian government reintroduced the use of Cyrillic to Belarusian in 1864 and no documents in Belarusian were permitted by the Russian government until 1905.[60]

During the negotiations of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, Belarus first declared independence under German occupation on 25 March 1918, forming the Belarusian People's Republic.[61][62] Immediately afterwards, the Polish–Soviet War ignited, and the territory of Belarus was divided between Poland and Soviet Russia.[63] The Rada of the Belarusian Democratic Republic exists as a government in exile ever since then; in fact, it is currently the world's longest serving government in exile.[64]

Early states and interwar period

Sitting, left to right:

Aliaksandar Burbis, Jan Sierada, Jazep Varonka, Vasil Zacharka.

Standing, left to right:

Arkadź Smolič, Pyotra Krecheuski, Kastus Jezavitau, Anton Ausianik, Liavon Zayats.

The Belarusian People's Republic was the first attempt to create an independent Belarusian state under the name "Belarus". Despite significant efforts, the state ceased to exist, primarily because the territory was continually dominated by the German Imperial Army and the Imperial Russian Army in World War I, and then the Bolshevik Red Army. It existed from only 1918 to 1919 but created prerequisites for the formation of a Belarusian state. The choice of name was probably based on the fact that core members of the newly formed government were educated in tsarist universities, with corresponding emphasis on the ideology of West-Russianism.[65]

The Republic of Central Lithuania was a short-lived political entity, which was the last attempt to restore Lithuania in the historical confederacy state (it was also supposed to create Lithuania Upper and Lithuania Lower). The republic was created in 1920 following the staged rebellion of soldiers of the 1st Lithuanian–Belarusian Division of the Polish Army under Lucjan Żeligowski. Centered on the historical capital of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, Vilna (Lithuanian: Vilnius, Polish: Wilno), for 18 months the entity served as a buffer state between Poland, upon which it depended, and Lithuania, which claimed the area.[66] After a variety of delays, a disputed election took place on 8 January 1922, and the territory was annexed to Poland. Żeligowski later in his memoir which was published in London in 1943 condemned the annexation of the Republic by Poland, as well as the policy of closing Belarusian schools and general disregard of Marshal Józef Piłsudski's confederation plans by Polish ally.[67]

In January 1919 a part of Belarus under Bolshevik Russian control was declared the Socialist Soviet Republic of Byelorussia (SSRB) for just two months, but then merged with the Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic (LSSR) to form the Socialist Soviet Republic of Lithuania and Belorussia (SSR LiB), which lost control of its territories by August.

The Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic (BSSR) was created in July 1920.

The contested lands were divided between Poland and the Soviet Union after the war ended in 1921, and the Byelorussian SSR became a founding member of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics in 1922.[61][68] In the 1920s and 1930s, Soviet agricultural and economic policies, including collectivization and five-year plans for the national economy, led to famine and political repression.[69]

The western part of modern Belarus remained part of the Second Polish Republic.[70][citation needed][71] After an early period of liberalization, tensions between increasingly nationalistic Polish government and various increasingly separatist ethnic minorities started to grow, and the Belarusian minority was no exception.[72][73] The polonization drive was inspired and influenced by the Polish National Democracy, led by Roman Dmowski, who advocated refusing Belarusians and Ukrainians the right for a free national development.[74] A Belarusian organization, the Belarusian Peasants' and Workers' Union, was banned in 1927, and opposition to Polish government was met with state repressions.[72][73] Nonetheless, compared to the (larger) Ukrainian minority, Belarusians were much less politically aware and active, and thus suffered fewer repressions than the Ukrainians.[72][73] In 1935, after the death of Piłsudski, a new wave of repressions was released upon the minorities, with many Orthodox churches and Belarusian schools being closed.[72][73] Use of the Belarusian language was discouraged.[75] Belarusian leadership was sent to Bereza Kartuska prison.[76]

World War II

In 1939, Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union invaded and occupied Poland, marking the beginning of World War II. The Soviets invaded and annexed much of eastern Poland, which had been part of the country since the Peace of Riga two decades earlier. Much of the northern section of this area was added to the Byelorussian SSR, and now constitutes West Belarus.[14][15][16][77] The Soviet-controlled Byelorussian People's Council officially took control of the territories, whose populations consisted of a mixture of Poles, Ukrainians, Belarusians and Jews, on 28 October 1939 in Białystok. Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union in 1941. The defense of Brest Fortress was the first major battle of Operation Barbarossa.

The Byelorussian SSR was the hardest-hit Soviet republic in World War II; it remained in Nazi hands until 1944. The German Generalplan Ost called for the extermination, expulsion, or enslavement of most or all Belarusians for the purpose of providing more living space in the East for Germans.[78] Most of Western Belarus became part of the Reichskommissariat Ostland in 1941, but in 1943 the German authorities allowed local collaborators to set up a client state, the Belarusian Central Council.[79]

During World War II, Belarus was home to a variety of guerrilla movements, including Jewish, Polish, and Soviet partisans. Belarusian partisan formations formed a large part of the Soviet partisans,[80] and in the modern day these partisans have formed a core part of the Belarusian national identity, with Belarus continuing to refer to itself as the "partisan republic" since the 1970s.[81][82] Following the war, many former Soviet partisans entered positions of government, among them Pyotr Masherov and Kirill Mazurov, both of whom were First Secretary of the Communist Party of Byelorussia. Until the late 1970s, the Belarusian government was almost entirely composed of former partisans.[83] Numerous pieces of media have been made about the Belarusian partisans, including the 1985 film Come and See and the works of authors Ales Adamovich and Vasil Bykaŭ.

The German occupation in 1941–1944 and war on the Eastern Front devastated Belarus. During that time, 209 out of 290 towns and cities were destroyed, 85% of the republic's industry, and more than one million buildings. After the war, it was estimated that 2.2 million local inhabitants had died and of those some 810,000 were combatants—some foreign. This figure represented a staggering quarter of the prewar population. In the 1990s some raised the estimate even higher, to 2.7 million.[84] The Jewish population of Belarus was devastated during the Holocaust and never recovered.[17][85][86] The population of Belarus did not regain its pre-war level until 1971.[85]

Post-war

After the war, Belarus was among the 51 founding member states of the United Nations Charter and as such it was allowed an additional vote at the UN, on top of the Soviet Union's vote. Vigorous postwar reconstruction promptly followed the end of the war and the Byelorussian SSR became a major center of manufacturing in the western USSR, creating jobs and attracting ethnic Russians.[citation needed] The borders of the Byelorussian SSR and Poland were redrawn, in accord with the 1919-proposed Curzon Line.[56]

Joseph Stalin implemented a policy of Sovietization to isolate the Byelorussian SSR from Western influences.[85] This policy involved sending Russians from various parts of the Soviet Union and placing them in key positions in the Byelorussian SSR government. After Stalin's death in 1953, Nikita Khrushchev continued his predecessor's cultural hegemony program, stating, "The sooner we all start speaking Russian, the faster we shall build communism."[85]

Soviet Belarusian communist politician Andrei Gromyko, who served as Soviet foreign minister (1957–1985) and as Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet (1985–1988), was responsible for many top decisions on Soviet foreign policy until he was replaced by Eduard Shevardnadze.[87] In 1986, the Byelorussian SSR was contaminated with most (70%) of the nuclear fallout from the explosion at the Chernobyl power plant located 16 km beyond the border in the neighboring Ukrainian SSR.[88][89]

By the late 1980s, political liberalization led to a national revival, with the Belarusian Popular Front becoming a major pro-independence force.[90][91]

Independence

In March 1990, elections for seats in the Supreme Soviet of the Byelorussian SSR took place. Though the opposition candidates, mostly associated with the pro-independence Belarusian Popular Front, took only 10% of the seats,[92] Belarus declared itself sovereign on 27 July 1990 by issuing the Declaration of State Sovereignty of the Belarusian Soviet Socialist Republic.[93]

Mass protests erupted in April 1991 and became known as the 1991 Belarusian strikes. With the support of the Communist Party, the country's name was changed to the Republic of Belarus on 25 August 1991.[92] Stanislau Shushkevich, the chairman of the Supreme Soviet of Belarus, met with Boris Yeltsin of Russia and Leonid Kravchuk of Ukraine on 8 December 1991 in Białowieża Forest to formally declare the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the formation of the Commonwealth of Independent States.[92]

Lukashenko era

A national constitution was adopted in March 1994 in which the functions of prime minister were given to the President of Belarus. A two-round election for the presidency on 24 June 1994 and 10 July 1994[35] catapulted the formerly unknown Alexander Lukashenko into national prominence. He garnered 45% of the vote in the first round and 80%[92] in the second, defeating Vyacheslav Kebich who received 14% of the vote.

Lukashenko was officially re-elected in 2001, in 2006, in 2010, in 2015 and again in 2020, although none of those elections were considered free or fair nor democratic.[94][95][96][97][98][99][100][101][102][103]

Amnesty International,[104] and Human Rights Watch[105] have criticized Lukashenko's violations of human rights.

The 2000s saw a number of economic disputes between Belarus and its primary economic partner, Russia. The first one was the 2004 Russia–Belarus energy dispute when Russian energy giant Gazprom ceased the import of gas into Belarus because of price disagreements. The 2007 Russia–Belarus energy dispute centered on accusations by Gazprom that Belarus was siphoning oil off of the Druzhba pipeline that runs through Belarus. Two years later the so-called Milk War, a trade dispute, started when Russia wanted Belarus to recognize the independence of Abkhazia and South Ossetia and through a series of events ended up banning the import of dairy products from Belarus.

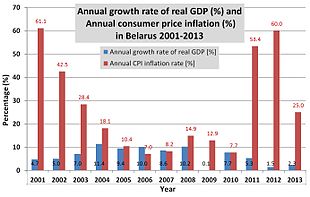

In 2011, Belarus suffered a severe economic crisis attributed to Lukashenko's government's centralized control of the economy, with inflation reaching 108.7%.[106] Around the same time the 2011 Minsk Metro bombing occurred in which 15 people were killed and 204 were injured. Two suspects, who were arrested within two days, confessed to being the perpetrators and were executed by shooting in 2012. The official version of events as publicised by the Belarusian government was questioned in the unprecedented wording of the UN Security Council statement condemning "the apparent terrorist attack" intimating the possibility that the Belarusian government itself was behind the bombing.[107]

Mass protests erupted across the country following the disputed 2020 Belarusian presidential election,[108] in which Lukashenko sought a sixth term in office.[109] Neighbouring countries Poland and Lithuania do not recognize Lukashenko as the legitimate president of Belarus and the Lithuanian government has allotted a residence for main opposition candidate Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya and other members of the Belarusian opposition in Vilnius.[110][111][112][113][114] Neither is Lukashenko recognized as the legitimate president of Belarus by the European Union, Canada, the United Kingdom nor the United States.[115][116][117][118] The European Union, Canada, the United Kingdom and the United States have all imposed sanctions against Belarus because of the rigged election and political oppression during the ongoing protests in the country.[119][120] Further sanctions were imposed in 2022 following the country's role in the invasion of Ukraine.[121][122] These include not only corporate offices and individual officers of government but also private individuals who work in the state-owned enterprise industrial sector.[123] Norway and Japan have joined the sanctions regime which aims to isolate Belarus from the international supply chain. Most major Belarusian banks are also under restrictions.[123]

Geography

Belarus lies between latitudes 51° and 57° N, and longitudes 23° and 33° E. Its extension from north to south is 560 km (350 mi), from west to east is 650 km (400 mi).[124] It is landlocked, relatively flat, and contains large tracts of marshy land.[125] About 40% of Belarus is covered by forests.[126][127] The country lies within two ecoregions: Sarmatic mixed forests and Central European mixed forests.[128]

Many streams and 11,000 lakes are found in Belarus.[125] Three major rivers run through the country: the Neman, the Pripyat, and the Dnieper. The Neman flows westward towards the Baltic sea and the Pripyat flows eastward to the Dnieper; the Dnieper flows southward towards the Black Sea.[129]

The highest point is Dzyarzhynskaya Hara (Dzyarzhynsk Hill) at 345 metres (1,132 ft), and the lowest point is on the Neman River at 90 m (295 ft).[125] The average elevation of Belarus is 160 m (525 ft) above sea level.[130] The climate features mild to cold winters, with January minimum temperatures ranging from −4 °C (24.8 °F) in southwest (Brest) to −8 °C (17.6 °F) in northeast (Vitebsk), and cool and moist summers with an average temperature of 18 °C (64.4 °F).[131] Belarus has an average annual rainfall of 550 to 700 mm (21.7 to 27.6 in).[131] The country is in the transitional zone between continental climates and maritime climates.[125]

Natural resources include peat deposits, small quantities of oil and natural gas, granite, dolomite (limestone), marl, chalk, sand, gravel, and clay.[125] About 70% of the radiation from neighboring Ukraine's 1986 Chernobyl nuclear disaster entered Belarusian territory, and about a fifth of Belarusian land (principally farmland and forests in the southeastern regions) was affected by radiation fallout.[132] The United Nations and other agencies have aimed to reduce the level of radiation in affected areas, especially through the use of caesium binders and rapeseed cultivation, which are meant to decrease soil levels of caesium-137.[133][134]

Belarus borders five countries: Latvia to the north, Lithuania to the northwest, Poland to the west, Russia to the north and the east, and Ukraine to the south. Treaties in 1995 and 1996 demarcated Belarus's borders with Latvia and Lithuania, and Belarus ratified a 1997 treaty establishing the Belarus-Ukraine border in 2009.[135] Belarus and Lithuania ratified final border demarcation documents in February 2007.[136]

Government and politics

Belarus, by constitution, is a presidential republic with separation of powers, governed by a president and the National Assembly. However, Belarus has often been described as "Europe's last dictatorship" and president Alexander Lukashenko as "Europe's last dictator"[137] by some media outlets, politicians and authors due to its authoritarian government.[138][139][140][141] Belarus has been considered an autocracy where power is ultimately concentrated in the hands of the president, elections are not free and judicial independence is weak.[142] The Council of Europe removed Belarus from its observer status since 1997 as a response for election irregularities in the November 1996 constitutional referendum and parliament by-elections.[143][144] Re-admission of the country into the council is dependent on the completion of benchmarks set by the council, including the improvement of human rights, rule of law, and democracy.[145]