"Auricularia" larva (by Ernst Haeckel)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sea_cucumber#

Sequential hermaphroditism (called dichogamy in botany) is one of the two types of hermaphroditism, the other type being simultaneous hermaphroditism. It occurs when the organism's sex changes at some point in its life.[1] In particular, a sequential hermaphrodite produces eggs (female gametes) and sperm (male gametes) at different stages in life.[2] Sequential hermaphroditism occurs in many fish, gastropods, and plants. Species that can undergo these changes do so as a normal event within their reproductive cycle, usually cued by either social structure or the achievement of a certain age or size.[3] In some species of fish, sequential hermaphroditism is much more common than simultaneous hermaphroditism.[4]

In animals, the different types of change are male to female (protandry or protandrous hermaphroditism), female to male (protogyny or protogynous hermaphroditism),[5] and bidirectional (serial or bidirectional hermaphroditism).[6] Both protogynous and protandrous hermaphroditism allow the organism to switch between functional male and functional female.[7] Bidirectional hermaphrodites have the capacity for sex change in either direction between male and female or female and male, potentially repeatedly during their lifetime.[6] These various types of sequential hermaphroditism may indicate that there is no advantage based on the original sex of an individual organism.[7] Those that change gonadal sex can have both female and male germ cells in the gonads or can change from one complete gonadal type to the other during their last life stage.[8]

In plants, individual flowers are called dichogamous if their function has the two sexes separated in time, although the plant as a whole may have functionally male and functionally female flowers open at any one moment. A flower is protogynous if its function is first female, then male, and protandrous if its function is male then female. It used to be thought that this reduced inbreeding,[9] but it may be a more general mechanism for reducing pollen-pistil interference.[10]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sequential_hermaphroditism

All echinoderms also possess anatomical feature(s) called mutable collagenous tissues, or MCTs.[38] Such tissues can rapidly change their passive mechanical properties from soft to stiff under the control of the nervous system and coordinated with muscle activity. Different echinoderm classes use MCTs in different ways. The asteroids, sea stars, can detach limbs for self-defense and then regenerate them. The Crinoidea, sea fans, can go from stiff to limp depending on the current for optimal filter feeding. The Echinoidea, sand dollars, use MCTs to grow and replace their rows of teeth when they need new ones. The Holothuroidea, sea cucumbers, use MCTs to eviscerate their gut as a self-defense response. MCTs can be used in many ways but are all similar at the cellular level and in mechanics of function. A common trend in the uses of MCTs is that they are generally used for self-defense mechanisms and in regeneration.[38]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sea_cucumber#

Elasipodida like this "sea pig" Scotoplanes have a translucent body with specific appendages; they live in the abyss.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sea_cucumber#

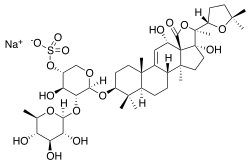

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

|

| Identifiers | |

|---|---|

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChemSpider | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| Properties | |

|---|---|

| C54H85NaO25S | |

| Molar mass | 1189.3 g/mol |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

|

| Identifiers | |

|---|---|

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChemSpider | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| Properties | |

|---|---|

| C54H85NaO27S | |

| Molar mass | 1221.3 g/mol |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

|

| Identifiers | |

|---|---|

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChemSpider | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| Properties | |

|---|---|

| C41H63NaO17S | |

| Molar mass | 883 g/mol |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

The holothurins are a group of toxins originally isolated from the sea cucumber Actinopyga agassizii.[4] They are contained within clusters of sticky threads called Cuvierian tubules which are expelled from the sea cucumber as a mode of self-defence.[5] The holothurins belong to the class of compounds known as saponins and are anionic surfactants which can cause red blood cells to rupture.[6][7] The holothurins can be toxic to humans if ingested in high amounts.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Holothurin

| Giant tun | |

|---|---|

| |

| Five views of a shell of Tonna galea | |

| |

| A live giant tun, from Greece | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Mollusca |

| Class: | Gastropoda |

| Subclass: | Caenogastropoda |

| Order: | Littorinimorpha |

| Family: | Tonnidae |

| Genus: | Tonna |

| Species: | T. galea

|

| Binomial name | |

| Tonna galea | |

| Synonyms | |

|

See List of synonyms | |

Tonna galea, commonly known as the giant tun, is a species of marine gastropod mollusc in the family Tonnidae (also known as the tun shells). This very large sea snail or tun snail is found in the North Atlantic Ocean as far as the coast of West Africa, in the Mediterranean Sea and the Caribbean Sea. The species was first described by Carl Linnaeus in 1758.[1]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tonna_galea

Cuvierian tubules are clusters of fine tubes located at the base of the respiratory tree in some sea cucumbers in the genera Bohadschia, Holothuria and Pearsonothuria, all of which are included in the family Holothuriidae. The tubules can be discharged through the anus when the sea cucumber is stressed. They lengthen when they come into contact with seawater and become adhesive when they encounter objects so that they function as a defence against potential predators. They are named after the French zoologist Georges Cuvier, who first described them.[1]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cuvierian_tubules

The anglerfish are fish of the teleost order Lophiiformes (/ˌlɒfiɪˈfɔːrmiːz/).[1] They are bony fish named for their characteristic mode of predation, in which a modified luminescent fin ray (the esca or illicium) acts as a lure for other fish. The luminescence comes from symbiotic bacteria, which are thought to be acquired from seawater,[2][3] that dwell in and around the sea.

Some anglerfish are notable for extreme sexual dimorphism and sexual symbiosis of the small male with the much larger female, seen in the suborder Ceratioidei, the deep sea anglerfish. In these species, males may be several orders of magnitude smaller than females.[4]

Anglerfish occur worldwide. Some are pelagic (dwelling away from the sea floor), while others are benthic (dwelling close to the sea floor). Some live in the deep sea (such as the Ceratiidae), while others on the continental shelf, such as the frogfishes and the Lophiidae (monkfish or goosefish). Pelagic forms are most often laterally compressed, whereas the benthic forms are often extremely dorsoventrally compressed (depressed), often with large upward-pointing mouths.[citation needed]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anglerfish

| Teleost Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Teleosts of different orders, painted by Castelnau, 1856 (left to right, top to bottom): Fistularia tabacaria (Syngnathiformes), Mylossoma duriventre (Characiformes), Mesonauta acora (Cichliformes), Corydoras splendens and Pseudacanthicus spinosus (Siluriformes), Acanthurus coeruleus (Acanthuriformes), Stegastes pictus (Incertae sedis, Pomacentridae) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Subclass: | Neopterygii |

| Infraclass: | Teleostei J. P. Müller, 1845[3] |

| Subdivisions | |

|

See text | |

Teleostei (/ˌtɛliˈɒstiaɪ/; Greek teleios "complete" + osteon "bone"), members of which are known as teleosts (/ˈtɛliɒsts, ˈtiːli-/),[4] is, by far, the largest infraclass in the class Actinopterygii, the ray-finned fishes,[a] containing 96% of all extant species of fish. Teleosts are arranged into about 40 orders and 448 families. Over 26,000 species have been described. Teleosts range from giant oarfish measuring 7.6 m (25 ft) or more, and ocean sunfish weighing over 2 t (2.0 long tons; 2.2 short tons), to the minute male anglerfish Photocorynus spiniceps, just 6.2 mm (0.24 in) long. Including not only torpedo-shaped fish built for speed, teleosts can be flattened vertically or horizontally, be elongated cylinders or take specialised shapes as in anglerfish and seahorses.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Teleost

| Seahorses Temporal range: Lower Miocene to present –

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Short-snouted seahorse (Hippocampus hippocampus) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Syngnathiformes |

| Family: | Syngnathidae |

| Subfamily: | Hippocampinae |

| Genus: | Hippocampus Rafinesque, 1810[1][2] |

| Type species | |

| Hippocampus heptagonus Rafinesque, 1810

| |

| Species | |

|

see Species. | |

| Synonyms | |

A seahorse (also written sea-horse and sea horse) is any of 46 species of small marine fish in the genus Hippocampus. "Hippocampus" comes from the Ancient Greek hippókampos (ἱππόκαμπος), itself from híppos (ἵππος) meaning "horse" and kámpos (κάμπος) meaning "sea monster"[4][5] or "sea animal".[6] Having a head and neck suggestive of a horse, seahorses also feature segmented bony armour, an upright posture and a curled prehensile tail.[7] Along with the pipefishes and seadragons (Phycodurus and Phyllopteryx) they form the family Syngnathidae.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Seahorse

Seahorses are mainly found in shallow tropical and temperate salt water throughout the world, from about 45°S to 45°N.[8] They live in sheltered areas such as seagrass beds, estuaries, coral reefs, and mangroves. Four species are found in Pacific waters from North America to South America. In the Atlantic, Hippocampus erectus ranges from Nova Scotia to Uruguay. H. zosterae, known as the dwarf seahorse, is found in the Bahamas.

Colonies have been found in European waters such as the Thames Estuary.[9]

Three species live in the Mediterranean Sea: H. guttulatus (the long-snouted seahorse), H. hippocampus (the short-snouted seahorse), and H. fuscus (the sea pony). These species form territories; males stay within 1 m2 (10 sq ft) of habitat, while females range over about one hundred times that.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Seahorse

Seahorses in Phase 2 of courtship

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Seahorse#/media/File:Seahorse_mating_dance.JPG

Seahorses rely on stealth to ambush small prey such as copepods. They use pivot feeding to catch the copepod, which involves rotating their snout at high speed and then sucking in the copepod.[41]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Seahorse#/media/File:Black_Sea_fauna_Seahorse.JPG

Seahorses (Hippocampus erectus) at the New England Aquarium

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Seahorse#/media/File:Seahorse-aquarium.jpg

Dried seahorse

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Seahorse#/media/File:Seahorse_Skeleton_Macro_8_-_edit.jpg

H. kuda, known as the "common seahorse"

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Seahorse#/media/File:Hippocampus_kuda_(Estuary_seahorse).jpg

H. subelongatus, known as the "West Australian seahorse"

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Seahorse#/media/File:Hippocampus_elongatus.jpg

No comments:

Post a Comment