The three-sector model in economics divides economies into three sectors of activity: extraction of raw materials (primary), manufacturing (secondary), and service industries which exist to facilitate the transport, distribution and sale of goods produced in the secondary sector (tertiary).[1] The model was developed by Allan Fisher,[2][3][4] Colin Clark,[5] and Jean Fourastié[6] in the first half of the 20th century, and is a representation of an industrial economy. It has been criticised as inappropriate as a representation of the economy in the 21st century.[7]

According to the three-sector model, the main focus of an economy's activity shifts from the primary, through the secondary and finally to the tertiary sector. Countries with a low per capita income are in an early state of development; the main part of their national income is achieved through production in the primary sector. Countries in a more advanced state of development, with a medium national income, generate their income mostly in the secondary sector. In highly developed countries with a high income, the tertiary sector dominates the total output of the economy.

The rise of the post-industrial economy in which an increasing proportion of economic activity is not directly related to physical goods has led some economists to expand the model by adding a fourth quaternary or fifth quinary sectors, while others have ceased to use the model.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Three-sector_model

History of taxation in the United Kingdom

The history of taxation in the United Kingdom includes the history of all collections by governments under law, in money or in kind, including collections by monarchs and lesser feudal lords, levied on persons or property subject to the government, with the primary purpose of raising revenue.

Background

Prior to the formation of the United Kingdom in 1707, taxation had been levied in the countries that joined to become the UK. For example, in England, King John introduced an export tax on wool in 1203 and King Edward I introduced taxes on wine in 1275. Also in England, a Poor Law tax was established in 1572 to help the deserving poor, and then changed from a local tax to a national tax in 1601.[1] In June 1628, England's Parliament passed the Petition of Right which among other measures, prohibited the use of taxes without its agreement. This prevented the Crown from creating arbitrary taxes and imposing them upon subjects without consultation.

One of the key taxes introduced by Charles II was to help pay for the rebuilding of the City of London after the Great Fire in 1666. Coal tax acts were passed in 1667 and in 1670. The tax was eventually repealed in 1889.[2]

In 1692, the Parliament of England introduced its national land tax. This tax was levied on rental values and applied both to rural and to urban land. No provision was made for re-assessing the 1692 valuations and consequently they remained in force well into the 18th century.[3]

From 1707

Window tax

When the United Kingdom of Great Britain came into being on 1 May 1707, the window tax, which had been introduced across England and Wales under the Act of Making Good the Deficiency of the Clipped Money in 1696,[4] continued. It had been designed to impose tax relative to the prosperity of the taxpayer, but without the controversy that then surrounded the idea of income tax. At that time, many people opposed income tax on principle because they believed that the disclosure of personal income represented an unacceptable governmental intrusion into private matters, and a potential threat to personal liberty.[5] In fact the first permanent British income tax was not introduced until 1842, and the issue remained intensely controversial well into the 20th century.[6]

When the window tax was introduced, it consisted of two parts: a flat-rate house tax of 2 shillings per house (equivalent to £14.76 in 2021) and a variable tax for the number of windows above ten windows. Properties with between ten and twenty windows paid a total of four shillings (comparable to £29.52 in 2021),[7] and those above twenty windows paid eight shillings (£59.05 as of 2021).[7][8]

Income tax

Income tax was first implemented in Great Britain by William Pitt the Younger in his budget of December 1798 to pay for weapons and equipment in preparation for the Napoleonic Wars. Pitt's new graduated (progressive) income tax began at a levy of 2 old pence in the pound (1⁄120th) on incomes over £60 (£6,719 as of 2021),[7] and increased up to a maximum of 2 shillings (10%) on incomes of over £200. Pitt hoped that the new income tax would raise £10 million, but actual receipts for 1799 totalled just over £6 million.[6]

19th century

Pitt's income tax was levied from 1799 to 1802, when it was abolished by Henry Addington during the Peace of Amiens. Addington had taken over as prime minister in 1801, after Pitt's resignation over Catholic Emancipation. The income tax was reintroduced by Addington in 1803 when hostilities recommenced, but it was again abolished in 1816, one year after the Battle of Waterloo.

Addington's Act for a 'contribution of the profits arising from property, professions, trades and offices' (the words 'income tax' were deliberately avoided) introduced two significant changes. First, it allowed taxation at the source; for example, the Bank of England would deduct an amount, to be paid as tax, from interest paid to holders of gilt-edged securities. Secondly, it introduced schedules:

- Schedule A (tax on income from UK land)

- Schedule B (tax on commercial occupation of land)

- Schedule C (tax on income from public securities)

- Schedule D (tax on trading income, income from professions and vocations, interest, overseas income and casual income)

- Schedule E (tax on employment income)

Income not falling within those schedules was not taxed. (Later a sixth schedule, schedule F – tax on UK dividend income – was added.)

Although the maximum tax rate under Addington's Act was 5% – only one-half of the 10% allowed under Pitt's – the other changes resulted in a 50% increase in revenue, largely because they doubled the number of persons liable for the tax and somewhat expanded the scope.[6]

Pitt in opposition had argued against Addington's innovations: he adopted them largely unchanged, however, when he returned to office in 1805. The one major change he made was to raise the maximum rate back to the 10%, the rate in his original bill, in 1806. Income tax changed little for the duration of the Napoleonic Wars, despite changes in government.[6]

Nicholas Vansittart was Chancellor in 1815, at the time of the Battle of Waterloo. He was inclined to maintain the income tax, but public sentiment was heavily against it, and predictably, the opposition championed its abolition. It was thus repealed in 1816 'with a thundering peal of applause'. In fact, the tax was so unpopular that Parliament ordered the destruction of all documents connected with it. This was more show than substance, for the King's Remembrancer had made duplicates and retained them.[6]

Under Peel

The general election of 1841 was won by the Conservatives with Sir Robert Peel as Prime Minister. Although he had opposed the unpopular income tax during the campaign, an empty Exchequer and a growing deficit gave rise to the surprise return of the tax in his 1842 Budget. Peel sought only to tax those with incomes above £150 per annum, and he reduced customs duties on 750 articles out of a total number taxed of 1,200. The less wealthy benefited, and trade revived as a consequence.[9][10] Peel's income tax was 7d in the pound (about 3%). It was imposed for three years, with the possibility of a two-year extension. A funding crisis in the railways and increasing national expenditure ensured that it was maintained. For Peel, the debate was academic. In 1846 he repealed the Corn Laws – which supported landowners by imposing tariffs on corn that was cheaper than that produced at home – and lost the support of much of his party. The Whigs resumed power the same year, to be joined by some notable 'Peelites'.[9]

Gladstone and Disraeli

The second half of the 19th century was dominated by two politicians – Benjamin Disraeli and William Ewart Gladstone.

A Conservative, Disraeli opposed Peel's repeal of the Corn Laws (which had inflated the price of imported grain to support home farmers). He was three times Chancellor of the Exchequer and twice Prime Minister.

Formerly a Conservative, Gladstone supported the repeal of the Corn Laws and moved to the opposition (Whigs, and from 1868 Liberals). He was four times Chancellor and four times Prime Minister – his final term starting at age 82.

Disraeli and Gladstone agreed about little, although both promised to repeal income tax at the 1874 General Election. Disraeli won – the tax stayed.

Gladstone spoke for nearly five hours introducing his 1853 Budget. He outlined plans for phasing out income tax over seven years (which the Crimean War was to upset), of extending the tax to Ireland, and introduced tax deductions for expenses 'wholly, exclusively and necessarily' incurred in the performance of an office – including keeping and maintaining a horse for work purposes. The 1853 Budget speech included a review of the history of the tax and its place in society, it is regarded as one of the most memorable ever made.

With the Whigs defeated in 1858, Disraeli returned as Chancellor and in his Budget speech described income tax as 'unjust, unequal and inquisitorial' and 'to continue for a limited time on the distinct understanding that it should ultimately be repealed'. But the Conservatives return to power was short-lived. From 1859 to 1866, the Whigs were back with Viscount Palmerston as Prime Minister and Gladstone as Chancellor.

Gladstone had set 1860 as the year for the repeal of income tax, and his Budget that year was eagerly awaited. Ill health caused it to be delayed and for his speech to be shortened to four hours. But he had to tell the House of Commons that he had no choice but to renew the tax. The hard fact was that it raised £10 million a year, and government expenditure had increased by £14 million since 1853 to £70 million (these figures should be multiplied by 50 for a modern equivalent).

Gladstone was still determined that income tax should be ended. When a select committee was set up against his wishes to consider reforms which might preserve it, he packed the committee with supporters to ensure that no improvements could be made. In 1866, the Whigs' modest attempts at parliamentary reform failed to win support in Parliament and the Conservatives returned to power, although with no overall majority. Disraeli succeeded where Gladstone had failed, seeing the Reform Bill of 1867 become law. This gave the vote to all householders and to those paying more than £10 in rent in towns – and so enfranchising many of the working class for the first time. Similar provisions for those living in the country came with Gladstone in 1884.

While Disraeli had gambled that an increased electorate would ensure a Conservative majority, and in 1868 he was prime minister, the election of that year saw the Liberals – as the Whigs had become – victorious under Gladstone. Income tax was maintained throughout his first government, and there were some significant changes made including the right to appeal to the High Court if a taxpayer or the Inland Revenue thought the decision of the appeal commissioners was wrong in law. But there was still a determination to end it. The Times, in its 1874 election coverage, said 'It is now evident that whoever is Chancellor when the Budget is produced, the income tax will be abolished'.

Disraeli won the election, Northcote was his Chancellor and the tax remained. At the time it was contributing about £6 million of the government's £77 million revenue, while Customs and Excise contributed £47 million. It could have been ended, but at the rate at which it was applied (less than 1%) and with most of the population exempt, it was not a priority. With worsening trade conditions, including the decline of agriculture as a result of poor harvests and North American imports, the opportunity never arose again.[11]

20th century

First World War

The war (1914–1918) was financed by borrowing large sums at home and abroad, by new taxes, and by inflation. It was implicitly financed by postponing maintenance and repair, and canceling unneeded projects. The government avoided indirect taxes because such methods tend to raise the cost of living, and can create discontent among the working class. There was a strong emphasis on being "fair" and being "scientific". The public generally supported the heavy new taxes, with minimal complaints. The Treasury rejected proposals for a stiff capital levy, which the Labour Party wanted to use to weaken the capitalists. Instead, there was an excess profits tax, of 50 percent of profits above the normal prewar level; the rate was raised to 80 percent in 1917. Excise taxes were added on luxury imports such as automobiles, clocks and watches. There was no sales tax or value added tax. The main increase in revenue came from the income tax, which in 1915 went up to 3s. 6d in the pound (17.5%), and individual exemptions were lowered. The income tax rate grew to 5s (25%) in 1916, and 6s (30%) in 1918.

Altogether taxes provided at most 30 percent of national expenditures, with the rest from borrowing. The national debt consequently soared from £625 million to £7.8 Billion. Government bonds typically paid five percent. Inflation escalated so that the pound in 1919 purchased only a third of the basket it had purchased it 1914. Wages were laggard, and the poor and retired were especially hard hit.[12][13]

Purchase tax

Between October 1940 and 1973 the UK had a consumption tax called Purchase Tax, which was levied at different rates depending on goods' luxuriousness. Purchase Tax was applied to the wholesale price, initially at a rate of 33⅓ %. This was doubled in April 1942 to 66⅔ %, and further increased in April 1943 to a rate of 100%, before reverting in April 1946 to 33⅓ % again. Unlike VAT, Purchase Tax was applied at the point of manufacture and distribution, not at the point of sale. The rate of Purchase Tax at the start of 1973, when it gave way to VAT, was 25%. On 1 January 1973 the UK joined the European Economic Community and as a consequence Purchase Tax was replaced by Value Added Tax on 1 April 1973. The Conservative Chancellor Lord Barber set a single VAT rate (10%) on most goods and services.

Income tax

This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2022) |

UK income tax has changed over the years. Originally it taxed a person's income, regardless of whether they had a legal obligation to pass it on to another person and would not have had any benefit from it. Modern income tax is only due when a person receives income to which he or she is beneficially entitled. Since 1965, income tax only applies to natural persons; since then, companies are subject instead to corporation tax. These changes were consolidated by the Income and Corporation Taxes Act 1970. Also the schedules under which tax is levied have changed. Schedule B was abolished in 1988, Schedule C in 1996 and Schedule E in 2003. For income tax purposes, the remaining schedules were superseded by the Income Tax (Trading and Other Income) Act 2005, which also repealed Schedule F completely. The Schedular system and Schedules A and D still remain in force for corporation tax. The highest rate of income tax peaked in the Second World War at 99.25%. It was then slightly reduced and was around 90% through the 1950s and 60s.[citation needed]

In 1971 the top rate of income tax on earned income was cut to 75%. A surcharge of 15% kept the top rate on investment income at 90%. In 1974 the cut was partly reversed and the top rate on earned income was raised to 83%. With the investment income surcharge this raised the top rate on investment income to 98%, the highest permanent rate since the war.[14] This applied to incomes over £20,000 (£221,741 as of 2021).[7]

The Government of Margaret Thatcher, who favoured taxation on consumption, reduced personal income tax rates during the 1980s in favour of indirect taxation.[15] In the first budget after her election victory in 1979, the top rate was reduced from 83% to 60% and the basic rate from 33% to 30%.[16] The basic rate was also cut for three successive budgets – to 29% in the 1986 budget, 27% in 1987 and to 25% in 1988; The top rate of income tax was cut to 40%.[17] The investment income surcharge was abolished in 1985.

Under the government of John Major the basic rate was reduced in stages to 23% by 1997.

Business rates

Business rates were introduced in England and Wales in 1990, and are a modernised version of a system of rating that dates back to the Elizabethan Poor Law of 1601. As such, business rates retain many previous features from, and follow some case law of, older forms of rating. The Finance Act 2004 introduced an income tax regime known as "pre-owned asset tax" which aims to reduce the use of common methods of inheritance tax avoidance.[18]

21st century

Under Labour chancellor Gordon Brown, the basic rate of income tax was further reduced in stages to 20% by 2007. As the basic rate stood at 35% in 1976, it has been reduced by 43% since then. However, this reduction has been largely offset by increases in other regressive taxes such as National Insurance contributions and Value Added Tax (VAT).

In 2010, a new top rate of 50% was introduced on income over £150,000 p.a. In the 2012 budget, this rate was cut to 45% with effect from 6 April 2013.

In 2022, as part of the September 2022 United Kingdom mini-budget, Chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng announced his intention (subject to Parliamentary approval) to abolish the top 45% rate and to cut the basic rate from 20% to 19% from April 2023. (The "higher rate" was to remain unchanged.) Previously announced rises in National Insurance and corporation tax were also to be reversed. When it became clear that such approval would not be forthcoming, he announced cancellation of the top-rate reduction plan.[19]

Devolution of Tax powers

The Scotland Act 2016 gave the Scottish Parliament full control over income tax rates and bands, except the personal allowance.[20] In 2017/18, the only notable difference between Scotland and the rest of the UK was that the higher rate limit was frozen in Scotland. However, the draft budget for 2018/19 proposed new rates and bands that would mark a real change from the rest of the UK.[21][needs update]

Start of tax year

Summary

British tax Acts in the middle of the eighteenth century said the tax year ran "from" 25 March. The use of "from" is crucial because the word has a special legal meaning which caused the tax year to begin one day later, namely, on 26 March.[a] The taxes charged annually in the mid eighteenth century were Land Tax and Window Tax.

The Calendar (New Style) Act 1750 elided eleven days from September 1752 but, despite this elision, the Window Tax tax year continued to run "from" 25 March 1753 (NS) until April 1758 when Parliament moved it to a year "from" 5 April.[22][b] The Land Tax year never changed.

Legal rule

When a document or statute said a period of time was to run 'from' a date an old legal rule provided that the period began on the following day. This rule of interpretation dates back at least to Sir Edward Coke's landmark work of 1628 called the Institutes of the Lawes of England.[23] Coke's book was written as a commentary on the 1481 treatise on property law by Sir Thomas Littleton. Hence the specialist use of "from" may originate much earlier than 1628. The key passage in the Institutes is short:

But let us return to Littleton … Touching on the time of the beginning of a lease for yeares, it is to be observed, that if a lease be made by indenture, bearing date 26 Maii &c to have and to hold for twenty one yeares, from the date, or from the day of the date, it shall begin on the twenty seventh day of May.[24] [Emphasis added.]

Coke's Institutes were an important source of education for lawyers and editions were published up to the nineteenth century. This is why tax acts in the eighteenth century used "from" 25 March in an exclusive sense to mean a period beginning on the following day. Numerous court cases have arisen because the technical meaning of from a date in acts and documents has been misunderstood.[25] The Office of the Parliamentary Counsel, which drafts legislation today, has published online drafting guidance which says the from a date formulation is ambiguous and should not be used.[26]

Perhaps the most important contemporary authority for the start of the Land Tax year is in An Exposition of the Land Tax by Mark A Bourdin of the Inland Revenue which was published in 1854. In a footnote on page 34 he says:

The year of assessment is from 26th March to the 25 March following.

— Mark A Bourdin.[27]

Bourdin does not use from in the strict sense required by Coke but it is clear that he believes the Land Tax year begins on 26 March and ends on the following 25 March.

In 1798 William Pitt made Land Tax permanent with the Land Tax Perpetuation Act 1798.[28] Section 3, for example, refers to "an assessment made in the year ending on the twenty fifth day of March 1799", which confirms the Land Tax year begins on 26 March. The Land Tax year remained essentially unchanged until the tax was abolished in 1963.

A number of authorities explain why the old tax year began on 26 March so that the addition of eleven days led directly to the modern tax year which begins on 6 April.[29][30][31]

Accounting convention

Accounting practice from time immemorial also took the same view. A quarter day, such as Lady Day which falls on 25 March, marked the end of an accounting period and not the beginning. This view is taken by leading authorities including The Exchequer Year,[32][33] The Pipe Roll Society[34] and Dr Robert Poole in two works.[35][36]

In the 1995 work Calendar Reform Dr Poole cites Treasury Board Papers at the National Archives under reference T30 12 and explains that, after the omission of eleven days in September 1752, Treasury quarterly accounts carried on being drawn up to the same four days but the dates had moved on by eleven days. He says:

... so the national accounts continued to be made up to end on the Old Style quarter-days of 5 January, 5 April, 5 July and 10 October.[37]

These were the old quarter days of 25 December, 25 March, 24 June and 29 September plus eleven days. Dr Poole's analysis is confirmed by a minute of the Board of Customs on 19 September 1752, shortly after the omission of the eleven days 3 to 13 September 1752 and not long before the first quarter day affected by the omission—Michaelmas 29 September 1752. The minute says:

On the correcting of the Kalendar all Quarterly Accounts and Payments of the Customs of what nature or kind 'soever are to be closed on 10th October—5th January—5th April and 5th July, And the Annual Accounts are to be made out from 5th January to 5th January in every Year.[38]

Eleven days added to prevent loss of tax?

Some commentators, such as Philip (1921),[39] have suggested the government added eleven days to the end of the tax year which began on 26 March 1752. They say this was done to avoid the loss of tax which they believe would otherwise have been caused by the omission of eleven days in September 1752. The Inland Revenue took this view in 1999 in a note issued on the 200th anniversary of the introduction of income tax in 1799.[40]

In fact the British tax authorities did not add eleven days to the end of the tax year which began on 26 March 1752. They did not need to add eleven days because the taxes charged by the year captured artificial, deemed income, and not actual income. For Land Tax, the more important of the two, the amounts taxed were fixed sums linked to the market rental value of property in 1692 when the tax was introduced.[41] For Window Tax it was so much per window. The same tax was due regardless of the year length. Window Tax was a permanent tax and its year did not change until 1758 when the tax was recast and the tax year moved by eleven days to run "from" 5 April.[42] That meant a year which began on 6 April because of Sir Edward Coke's 1628 interpretation rule.[23]

The Land Tax year never changed after 1752 and continued to run "from" 25 March (Lady Day). The entire Land Tax code, running to 80 pages, was re-enacted every year until 1798 when it was made permanent. Hence there was ample opportunity to revise the date on which the Land Tax year began but no change was made.

Online editions of British statutes generally omit the annual Land Tax Acts because of their transitory nature. The National Archives at Kew holds printed statute series which include copies of all the Land Tax Acts. However, a few Land Tax Acts are available online including the last annual Land Tax Act for the year from 25 March 1798.[43] The 1798 Act uses the standard "from" formula and says in section 2:

that the sum of one million nine hundred eighty-nine thousand six hundred seventy-three pound seven shillings and ten-pence farthing ... shall be raised, levied and paid unto his Majesty within the space of one year from the twenty-fifth day of March 1798.[43] [Emphasis added.]

Income tax

William Pitt introduced the first income tax in 1799, and followed the Window Tax precedent by adopting a year which ran "from" 5 April.[44] That meant, once again, a year which began on 6 April, and this has remained the start of the year ever since. For example, Addington's Income Tax Act 1803 continued to apply "from" 5 April—in this case from 5 April 1803.[45] Again, this meant a year beginning on 6 April 1803.

Income tax was repealed temporarily in 1802 during a brief period of peace in the long war with France. The act which repealed the tax included a provision which permitted the collection of tax due for earlier years. This saving provision confirmed that Pitt's income tax year ended on 5 April:

Provided always, and be it enacted, That the said respective Rates and Duties …shall continue in force for the Purpose of duly charging to the said Rates and Duties all Persons … who shall not have been respectively charged to the said Duties for the Year ending on the fifth Day of April 1802, or for any prior year...[46] [Emphasis added.]

It was not until 1860 that income tax legislation consistently adopted a charging formulation of the kind recommended today by the Office of the Parliamentary Counsel to identify the income tax year. For 1860–61 the tax was applied "for a year commencing on 6 April 1860".[47] [Emphasis added.]

Section 48(3) of the Taxes Management Act 1880 later provided a definition of the income tax year for the first time and uses "from" in the modern sense:[47]

Every assessment shall be made for the year commencing and ending on the days herein specified.

- (3) As regards income tax—

- In Great Britain and Ireland from the sixth day of April to the following fifth day of April inclusive.[48]

Section 28 Finance Act 1919 provided a new shorthand way to refer to the tax year:

The expression "the year 1919–20" means the year of assessment beginning on the sixth day of April 1919, and any expression in which two years are similarly mentioned means the year of assessment beginning on the sixth day of April in the first mentioned of those years.[49]

Finally, following a review aimed at simplifying tax legislation, a new definition appeared in section 4 Income Tax Act 2007:

(1) Income tax is charged for a year only if an Act so provides.

(2) A year for which income tax is charged is called a "tax year".

(3) A tax year begins on 6 April and ends on the following 5 April.

(4) "The tax year 2007–08" means the tax year beginning on 6 April 2007 (and any corresponding expression in which two years are similarly mentioned is to be read in the same way).[50]

Incorrect explanation for 6 April tax year

An alternative explanation of the origin of the tax year is still found on some British tax websites.[c] This stems from a book published in 1921 by Alexander Philip.[39] The relevant passage is short:

A curious instance of the persistence of the old style is to be found in the date of the financial year of the British Exchequer. Prior to 1752 that year officially commenced on 25th March. In order to ensure that it should always comprise a complete year the commencement of the financial year was altered to the 5th April. In 1800, owing to the omission of a leap year day observed by the Julian calendar, the commencement of the financial year was moved forward one day to 6th April, and 5th April became the last day of the preceding year. In 1900, however, this pedantic correction was overlooked, and the financial year is still held to terminate of 5th April, as it so happens that the Easter celebration occurs just about that time—indeed one result is that about one-half of the British financial years include two Easters and about one-half contain no Easter date.

— Alexander Philip, The Calendar: its history, structure and improvement[39]

Philip does not give any reason for his view and Poole's analysis shows that it is incorrect. Philip does not cite any legislation or other authority. It is also worth noting that the "financial year" he mentions is not the same as the income tax year. The financial year is statutorily defined by the Interpretation Act 1978 as the year which ends on 31 March.[51] This repeats an earlier similar definition in section 22 Interpretation Act 1889.[52] This is the year for government accounting and for corporation tax. Poole gives a simpler explanation:

The twelve- rather than eleven-day discrepancy between the start of the old year (25 March) and that of the modern financial year (6 April) has caused puzzlement, [...] In fact, 25 March was first day of the [calendar] year but the last day of the financial quarter, corresponding to 5 April; the difference was thus exactly eleven days.[53]

— Robert Poole, Time's alteration : calendar reform in early modern England

See also

Notes

- For example, EFN Ltd: "Why does the UK tax year end on 5th April?". 14 March 2014.

References

XXXI And be it further enacted by the authority aforesaid That from and after the fifth day of April one thousand seven hundred and fifty eight there shall be charged raised levied and paid unto his Majesty his heirs and successors the rates and duties upon houses windows or lights herein.

From the earliest times and for many centuries the year of account in the Exchequer ended at Michaelmas

Each roll nominally covered the events of a year ending at Michaelmas (29 September), rather than the calendar year or the regnal year, which was used in the rolls produced by other government departments.

HM Revenue & Customs are a very helpful lot and explained the reason why the tax year starts on 6 April as follows: 'In order not to lose 11 days' tax revenue in that tax year, though, the authorities decided to tack the missing days on at the end, which meant moving the beginning of the tax year from the 25 March, Lady Day, (which since the Middle Ages had been regarded as the beginning of the legal year) to 6 April'.[This explanation repeats the error made by Philips (1921), as described below in #Old explanation for 6 April tax year. It no longer appears on the HMRC website.]

There can be no doubt that both the apportionments to the counties by statute, and in that to the divisions by the Commissioners, the amounts were determined by reference to the assessments made under the first Act in 1692. In the Acts passed annually, or nearly so, for the next hundred years the Commissioners are specially directed to observe the proportions established in the reign of William and Mary, and this direction is repeated in Mr Pitt's Act of 1797.

An act for granting to his majesty until the 6th day of May next after the ratification of a definitive treaty of peace a contribution on the profits arising from property professions trades and offices

- Poole 1995, footnote 77, page 117.

Sources

- C R Cheney, ed. (1945). A Handbook of Dates for students of British History. Revised by Michael Jones, 2000. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521778459.

- Poole, Robert (1995). "'Give us our eleven days!': calendar reform in eighteenth-century England". Past & Present. Oxford Academic. 149 (1): 95–139. doi:10.1093/past/149.1.95. JSTOR 651100.

- Poole, Robert (1998). Time's alteration: calendar reform in early modern England. UCL Press, Routledge Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781857286229.

- Steel, Duncan (2001). Marking Time: The Epic Quest to Invent the Perfect Calendar. New York: Wiley. ISBN 9780471404217. (also available as e-book)

Further reading

- Beckett, John V. "Land Tax or Excise: the levying of taxation in seventeenth-and eighteenth-century England", in English Historical Review (1985): 285–308. in JSTOR

- Bernard, G. W. War, Taxation, and Rebellion in Early Tudor England: Henry VIII, Wolsey and the Amicable Grant of 1525 (1986)

- Braddick, Michael J. The nerves of state: taxation and the financing of the English state, 1558-1714 (Manchester University Press, 1996).

- Burg, David F. World History of Tax Rebellions: An Encyclopedia of Tax Rebels, Revolts, and Riots from Antiquity to the Present (Routledge, 2004)

- Carruthers, Bruce G. "From city of capital: Politics and markets in the English financial revolution." in The New Economic Sociology: A Reader (2004): 457-481.

- Cousins, Katherine. "The Failure of the First Income Tax: A Tale of Commercial Tax Evaders?." Journal of Legal History 39.2 (2018): 157-186. on 1799 tax; online

- Daunton, Martin. "Creating Consent: Taxation, War, and Good Government in Britain, 1688–1914." in The Leap of Faith (Oxford University Press, 2018).

- Daunton, Martin. Trusting Leviathan: the politics of taxation in Britain, 1799–1914 (Cambridge University Press, 2007)

- Dowell, Stephen. History of Taxation and Taxes in England (Routledge, 2013)

- Emory, Meade. "The Early English Income Tax: A Heritage for the Contemporary", in American Journal of Legal History (1965): 286–319. in JSTOR

- Fletcher, Marie M. "Death and taxes: Estate duty–a neglected factor in changes to British business structure after World War two." Business History (2021): 1-23. online

- Gardner, Leigh. Taxing colonial Africa: the political economy of British imperialism (Oxford University Press, 2012).

- Kennedy, William. English taxation, 1640–1799: An essay on policy and opinion (Routledge, 2018).

- Mollan, Simon, and Kevin D. Tennent. "International taxation and corporate strategy: evidence from British overseas business, circa 1900–1965." Business History 57.7 (2015): 1054-1081.

- O'Brien, Patrick K. "The political economy of British taxation, 1660‐1815", in Economic History Review (1988) 41#1 pp: 1–32. in JSTOR

- Pierpoint, Stephen. The Success of English Land Tax Administration 1643–1733 (2018) excerpt

- Rao, K. V. Ramakrishna. The British Approach Towards Taxation Customs And Excise (2009) online

- Shebab, F. Progressive Taxation: A Study of the Development of the Progressive Principle in the British Income Tax (1953) online

- Shirras, G. Findlay. and L. Rostas. The Burden of British Taxation (1942)

- Sloman, Peter. Transfer state: The idea of a guaranteed income and the politics of redistribution in modern Britain (Oxford University Press, 2019).

External links

- Lay summary in: Lewis, Paul (5 April 2020). "Why does the tax year really begin on 6 April". Blogspot. (Paul Lewis presents Money Box on BBC Radio 4.[1])

- HMRC; HM Treasury; Welsh Government; Scottish Government. "Personal tax | Income Tax: detailed information". Gov.UK.

- BBC Radio 4 Money Box Presenter Profiles Paul Lewis

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_taxation_in_the_United_Kingdom

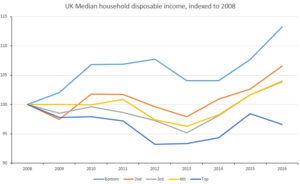

Income in the United Kingdom

Median household disposable income in the UK was £29,400 in the financial year ending (FYE) 2019, up 1.4% (£400) compared with growth over recent years; median income grew by an average of 0.7% per year between FYE 2017 and FYE 2019, compared with 2.8% between FYE 2013 and FYE 2017.[2]

The rise in median income has occurred during a period where the employment rate grew by 0.5 percentage points, while real total pay for employees increased by an average of 1.0% across the 12 months in FYE 2019 compared with FYE 2018.[2]

Median income of people living in retired households increased by 1.1% (£300), while the median income of people living in non-retired households grew by 1.3% (£400).[2]

Data sources

There are a number of different sources of data on income which results in different estimates of income due to different sample sizes, population types (e.g. whether the population sample includes the self-employed, pensioners, individuals not liable to tax), definitions of income (e.g. gross earnings vs original income vs gross income vs net income vs post tax income).[3]

The Survey of Personal Incomes (SPI) is a dataset from HM Revenue and Customs (HMRC) based on individuals who could be liable to tax. HMRC does not hold information on individuals whose income is below the personal allowance (£8,105 in 2012/13).[4] Furthermore, SPI does not include income from non taxable benefits such as housing benefits or Jobseeker's Allowance.[5][3]

The Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings (ASHE) is a dataset from an annual survey of approximately 50,000 businesses by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) and covers annual earnings, public and private sector pay differential and the gender pay gap. ASHE does not cover individuals who are self-employed.[3][6]

The Households Below Average Income (HBAI) dataset is based on the Family Resources Survey (FRS) from the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP). It includes information on equalised household disposable income and can be used to represent the distribution of household income and income inequality (Gini coefficient).[7][3]

Other data sources include Average Weekly Earnings, Labour Force Survey, Index of Labour Cost per Hour, Unit Labour Costs, Effects of Taxes and Benefits on Household Income / Living Costs and Food Survey, European Union Statistics on Income and Living Conditions, Pensioners Income Series, Wealth and Assets Survey, National Accounts Estimates of Gross Disposable Household Income, and Small Area Income Estimates.[3]

Taxable income

The most recent SPI report (2012/13) gave annual median income as £21,000 before tax and £18,700 after tax.[5] The 2013/14 HBAI report gave median household income (2 adults) as £23,556.[7] The provisional results from the April 2014 ASHE report gives median gross annual earnings of £22,044 for all employees and £27,195 for full-time employees.[6]

According to the OECD the average household net-adjusted disposable income per capita is $27,029 a year (in USD, ranked 14/36 OECD countries), the average household net financial wealth per capita is estimated at $60,778 (in USD, ranked 8/36), and the average net-adjusted disposable income of the top 20% of the population is an estimated $57,010 a year, whereas the bottom 20% live on an estimated $10,195 a year giving a ratio of 5.6 (in USD, ranked 25/36).[8]

The 2013/14 HBAI reported that 15% of people had a relative low income (below 60% of median threshold) before housing costs.[7]

Data from HMRC 2012-13; incomes are before tax for individuals. The personal allowance or income tax threshold was £8,105 (people with incomes below this level did not pay income tax).[4]

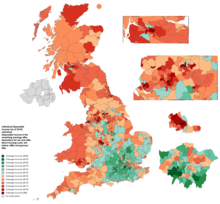

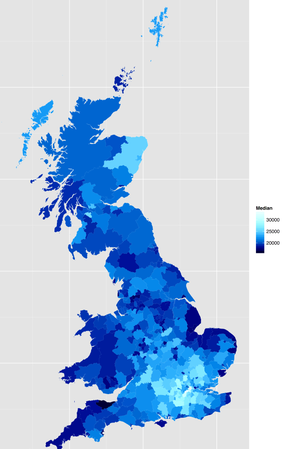

Income by location

Income can vary considerably by location. For example, the locations (local administrative unit) with the highest incomes were the City of London, Kensington and Chelsea, and Westminster with median annual incomes of £58,300, £37,800 and £35,200 respectively. The locations with the lowest incomes were Hyndburn, Torbay, and West Somerset with median annual incomes of £17,000, £16,900 and £16,000 respectively.

A 2017 report from Trust for London found that London has a poverty rate of 27%, compared to 21% in the rest of England.[9]

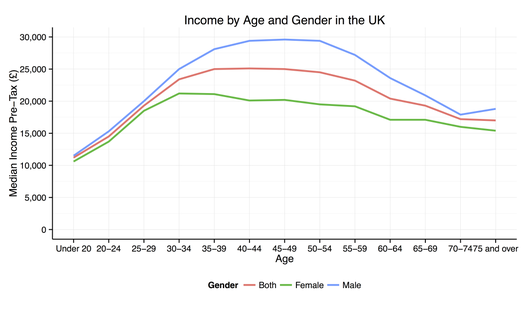

Income by age and gender

Data from the Survey of Personal Incomes 2012/13.

Income by occupation

The tables below shows the ten highest and ten lowest paid occupations in the UK respectively, as at April 2014.[10]

| Occupation | Median full-time gross weekly pay (£) |

|---|---|

| Aircraft pilots and flight engineers | 1,746.6 |

| Air traffic controllers | 1,549.4 |

| Chief executives and senior officials | 1,533.3 |

| Marketing and sales directors | 1,298.7 |

| Advertising and public relations directors | 1,289.5 |

| Information technology and telecommunications directors | 1,226.7 |

| Legal professionals (not included elsewhere) | 1,217.3 |

| Medical practitioners | 1,167.1 |

| Brokers | 1,149.9 |

| Financial managers and directors | 1,143.0 |

| Occupation | Median full-time gross weekly pay (£) |

|---|---|

| Cleaners and domestics | 285.5 |

| Nursery nurses and assistants | 285.2 |

| Other elementary services occupations (not included elsewhere) | 279.9 |

| Retail cashiers and check-out operators | 278.7 |

| Leisure and theme park attendants | 272.7 |

| Kitchen and catering assistants | 268.4 |

| Hairdressers and barbers | 267.8 |

| Launderers, dry cleaners and pressers | 259.3 |

| Waiters and waitresses | 257.6 |

| Bar staff | 253.6 |

Post-tax household income

Data from the Households Below Average Income (HBAI) report from the Department of Work and Pensions 2013/14:

Data from HMRC – Percentile points of the income distribution as estimated from the Survey of Personal Incomes, note this only includes individuals who pay some income tax:

Wealth

The Office for National Statistics found that the median total wealth for individuals in Great Britain was estimated to be £125,000 between April 2018 and March 2020. The mean figure is £305,000, reflecting the unequal wealth distribution with the wealthiest 10% of individuals owning close to half (48.58%) of all wealth compared to the bottom 50% owning 5.90% of all wealth.[11]

| Wealth Decile | Percentage of total wealth held |

|---|---|

| 1st (lowest) wealth decile | 0.02% |

| 2nd wealth decile | 0.38% |

| 3rd wealth decile | 0.79% |

| 4th wealth decile | 1.60% |

| 5th wealth decile | 3.11% |

| 6th wealth decile | 5.24% |

| 7th wealth decile | 8.17% |

| 8th wealth decile | 12.35% |

| 9th wealth decile | 19.76% |

| 10th (highest) wealth decile | 48.58% |

The net worth information is based on data from HMRC for 2004-2005 [12] and includes marketable assets including house equity, cash, shares, bonds and investment trusts. These values do not include personal possessions.

| Percentile point | Wealth to qualify | Percentage of total wealth owned by people at and above this level |

|---|---|---|

| Top 1% | £688,228 | 21% of total UK wealth |

| 2% | £460,179 | 28% of total UK wealth |

| 5% | £270,164 | 40% of total UK wealth |

| 10% | £176,221 | 53% of total UK wealth |

| 25% | £76,098 | 72% of total UK wealth |

| 50% | £35,807 | 93% of total UK wealth |

High income

This section needs to be updated. (October 2015) |

The Institute for Fiscal Studies issued a report on the UK's highest earners in January 2008. There are 42 million adults in the UK of whom 29 million are income tax payers. (The remainder are pensioners, students, homemakers, the unemployed, those earning under the personal allowance, and other unwaged.) A summary of key findings is shown in the table below:

| 2008 Data | All taxpayers | Top 10% to 1% (adults) | Top 1% to 0.1% (adults) | Top 0.1% (adults) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 29.5 million | 4.21 million | 421,000 | 42,000 |

| Entry level for group | £5,093 | £35,345 | £99,727 | £351,137 |

| Mean value for group | £24,769 | £49,960 | £155,832 | £780,043 |

| Average income tax paid | £4,415 | £10,550 | £49,477 | £274,482 |

| Percentage of national personal income | 100% | 27.6% | 8.6% | 4.2% |

The top 0.1% are 90% male and 50% of these people are in the 45 to 54 year age group. 31% of these people live in London and 21% in South East England. 33% of these people are company directors (as reported to HMRC). 30% work in finance and 38% in general business (includes law). The very richest rely on earnings (salary and bonuses) for 58% of income. Income from self-employment (such as partnerships in law or accountancy firms) accounts for 23% of income and about 18% from investment income (interest and share dividends).

Sources of income

This section needs to be updated. (October 2015) |

The Family Resources Survey is a document produced by the Department for Work and Pensions. This details income amongst a representative sample of the British population. This report tabulates sources of income as a percentage of total income.[13]

| Region | Employment (salaries and wages) | Self employed | Investment income | Working tax credit | State pensions | Occupational pensions | Disability benefits | Other social security benefits | Other income sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UK | 64% | 11% | 2% | 1% | 6% | 7% | 2% | 5% | 2% |

| Northern Ireland | 60% | 11% | 1% | 2% | 7% | 5% | 4% | 7% | 3% |

| Scotland | 66% | 7% | 2% | 2% | 7% | 7% | 3% | 5% | 2% |

| Wales | 60% | 8% | 2% | 2% | 8% | 8% | 4% | 6% | 1% |

| England | 64% | 11% | 2% | 1% | 6% | 7% | 2% | 5% | 2% |

| North East England | 64% | 5% | 2% | 2% | 8% | 6% | 4% | 7% | 2% |

| North West England | 59% | 13% | 2% | 2% | 7% | 7% | 3% | 6% | 2% |

| Yorkshire | 64% | 7% | 2% | 2% | 7% | 7% | 2% | 5% | 3% |

| East Midlands | 65% | 9% | 2% | 1% | 7% | 6% | 2% | 5% | 3% |

| West Midlands | 62% | 8% | 3% | 2% | 8% | 6% | 2% | 5% | 3% |

| Eastern England | 56% | 22% | 2% | 1% | 5% | 7% | 1% | 3% | 2% |

| London | 71% | 10% | 2% | 1% | 4% | 4% | 1% | 5% | 3% |

| South East | 66% | 9% | 4% | 1% | 7% | 8% | 1% | 4% | 2% |

| South West England | 60% | 9% | 4% | 1% | 7% | 10% | 2% | 4% | 2% |

Other social security benefits include: Housing Benefit, Income Support and Jobseeker's Allowance

See also

- Poverty in the United Kingdom

- Taxation in the United Kingdom

- Pension provision in the United Kingdom

- United Kingdom labour law

- Universal basic income in the United Kingdom

- Universal Credit

References

- "Family Resources Survey 2005-06". Archived from the original on 11 January 2008. Retrieved 21 January 2008.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Income_in_the_United_Kingdom

No comments:

Post a Comment