| Latin script, Blackletter hand | |

|---|---|

| |

| Script type | Alphabet

|

Time period | 12th – 17th century |

| Direction | left-to-right |

| Languages | Western and Northern European languages |

| Related scripts | |

Parent systems | Latin script

|

Child systems | Fraktur (Fraktur and blackletter are sometimes used interchangeably), Kurrentschrift including Sütterlin |

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Latf (217), Latin (Fraktur variant) |

| Unicode | |

1D504–1D537, with some exceptions (see below) | |

Blackletter (sometimes black letter), also known as Gothic script, Gothic minuscule, or Textura, was a script used throughout Western Europe from approximately 1150 until the 17th century.[1] It continued to be commonly used for the Danish, Norwegian, and Swedish languages until the 1870s,[2] Latvian language until the 1930s,[3] and for the German language until the 1940s, when Hitler's distaste for the supposedly "Jewish-influenced" script saw it officially discontinued in 1941.[4] Fraktur is a notable script of this type, and sometimes the entire group of blackletter faces is incorrectly referred to as Fraktur. Blackletter is sometimes referred to as Old English, but it is not to be confused with the Old English language, which predates blackletter by many centuries and was written in the insular script or in Futhorc. Along with Italic type and Roman type, blackletter served as one of the major typefaces in the history of Western typography.

Origins

Carolingian minuscule was the direct ancestor of blackletter. Blackletter developed from Carolingian as an increasingly literate 12th-century Europe required new books in many different subjects. New universities were founded, each producing books for business, law, grammar, history and other pursuits, not solely religious works, for which earlier scripts typically had been used.

These books needed to be produced quickly to keep up with demand. Labor-intensive Carolingian, though legible, was unable to effectively keep up.[citation needed] Its large size consumed a lot of manuscript space in a time when writing materials were very costly. As early as the 11th century, different forms of Carolingian were already being used, and by the mid-12th century, a clearly distinguishable form, able to be written more quickly to meet the demand for new books,[citation needed] was being used in northeastern France and the Low Countries.

Etymology

The term Gothic was first used to describe this script in 15th-century Italy, in the midst of the Renaissance, because Renaissance humanists believed this style was barbaric, and Gothic was a synonym for barbaric. Flavio Biondo, in Italia Illustrata (1474), wrote that the Germanic Lombards invented this script after they invaded Italy in the 6th century.

Not only were blackletter forms called Gothic script, but any other seemingly barbarian script, such as Visigothic, Beneventan, and Merovingian, were also labeled Gothic. This in contrast to Carolingian minuscule, a highly legible script which the humanists called littera antiqua ("the ancient letter"), wrongly believing that it was the script used by the ancient Romans. It was in fact invented in the reign of Charlemagne, although only used significantly after that era, and actually formed the basis for the later development of blackletter.[5]

Blackletter script should not be confused with either the ancient alphabet of the Gothic language nor with the sans-serif typefaces that are also sometimes called Gothic.

Forms

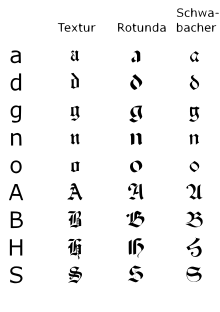

Textura

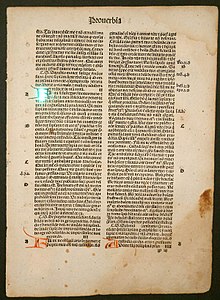

Textualis, also known as textura or Gothic bookhand, was the most calligraphic form of blackletter, and today is the form most associated with "Gothic". Johannes Gutenberg carved a textualis typeface – including a large number of ligatures and common abbreviations – when he printed his 42-line Bible. However, textualis was rarely used for typefaces after this.

According to Dutch scholar Gerard Lieftinck, the pinnacle of blackletter use was reached in the 14th and 15th centuries. For Lieftinck, the highest form of textualis was littera textualis formata, used for de luxe manuscripts. The usual form, simply littera textualis, was used for literary works and university texts. Lieftinck's third form, littera textualis currens, was the cursive form of blackletter, extremely difficult to read and used for textual glosses, and less important books.

Textualis was most widely used in France, the Low Countries, England, and Germany. Some characteristics of the script are:

- Tall, narrow letters, as compared to their Carolingian counterparts.

- Letters formed by sharp, straight, angular lines, unlike the typically round Carolingian; as a result, there is a high degree of "breaking", i.e. lines that do not necessarily connect with each other, especially in curved letters.

- Ascenders (in letters such as ⟨b⟩, ⟨d⟩, ⟨h⟩) are vertical and often end in sharp finals

- When a letter with a bow (in ⟨b⟩, ⟨d⟩, ⟨p⟩, ⟨q⟩) is followed by another letter with a bow (such as ⟨be⟩ or ⟨po⟩), the bows overlap and the letters are joined by a straight line (this is known as "biting").

- A related characteristic is the half r (also called r rotunda), the shape of ⟨r⟩ when attached to other letters with bows; only the bow and tail were written, connected to the bow of the previous letter. In other scripts, this only occurred in a ligature with the letter ⟨o⟩.

- Similarly related is the form of the letter ⟨d⟩ when followed by a letter with a bow; its ascender is then curved to the left, like the uncial ⟨d⟩. Otherwise the ascender is vertical.

- The letters ⟨g⟩, ⟨j⟩, ⟨p⟩, ⟨q⟩, ⟨y⟩, and the hook of ⟨h⟩ have descenders, but no other letters are written below the line.

- The letter a has a straight back stroke, and the top loop eventually became closed, somewhat resembling the number ⟨8⟩. The letter s often has a diagonal line connecting its two bows, also somewhat resembling an ⟨8⟩, but the long s is frequently used in the middle of words.

- Minims, especially in the later period of the script, do not connect with each other. This makes it very difficult to distinguish ⟨i⟩, ⟨u⟩, ⟨m⟩, and ⟨n⟩. A 14th-century example of the difficulty minims produced is: mimi numinum niuium minimi munium nimium uini muniminum imminui uiui minimum uolunt ('the smallest mimes of the gods of snow do not wish at all in their life that the great duty of the defenses of wine be diminished'). In blackletter, this would look like a series of single strokes. As a result, dotted ⟨i⟩ and the letter ⟨j⟩ were subsequently developed.[6] Minims may also have finals of their own.

- The script has many more scribal abbreviations than Carolingian, adding to the speed in which it could be written.

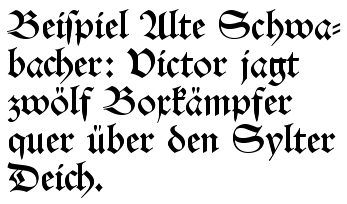

Schwabacher

Schwabacher was a blackletter form that was much used in early German print typefaces. It continued to be used occasionally until the 20th century. Characteristics of Schwabacher are:

- The small letter ⟨o⟩ is rounded on both sides, though at the top and at the bottom, the two strokes join in an angle. Other small letters have analogous forms.

- The small letter ⟨g⟩ has a horizontal stroke at its top that forms crosses with the two downward strokes.

- The capital letter ⟨H⟩ has a peculiar form somewhat reminiscent of the small letter ⟨h⟩.

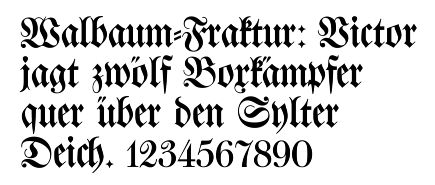

Fraktur

Fraktur is a form of blackletter that became the most common German blackletter typeface by the mid-16th century. Its use was so common that often any blackletter form is called Fraktur in Germany. Characteristics of Fraktur are:

- The left side of the small letter ⟨o⟩ is formed by an angular stroke, the right side by a rounded stroke. At the top and at the bottom, both strokes join in an angle. Other small letters have analogous forms.

- The capital letters are compound of rounded ⟨c⟩-shaped or ⟨s⟩-shaped strokes.

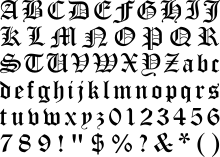

Here is the entire alphabet in Fraktur (minus the long s and the sharp s ⟨ß⟩), using the AMS Euler Fraktur typeface:

Cursiva

Cursiva refers to a very large variety of forms of blackletter; as with modern cursive writing, there is no real standard form. It developed in the 14th century as a simplified form of textualis, with influence from the form of textualis as used for writing charters. Cursiva developed partly because of the introduction of paper, which was smoother than parchment. It was therefore, easier to write quickly on paper in a cursive script.

In cursiva, descenders are more frequent, especially in the letters ⟨f⟩ and ⟨s⟩, and ascenders are curved and looped rather than vertical (seen especially in the letter ⟨d⟩). The letters ⟨a⟩, ⟨g⟩ and ⟨s⟩ (at the end of a word) are very similar to their Carolingian forms. However, not all of these features are found in every example of cursiva, which makes it difficult to determine whether or not a script may be called cursiva at all.

Lieftinck also divided cursiva into three styles: littera cursiva formata was the most legible and calligraphic style. Littera cursiva textualis (or libraria) was the usual form, used for writing standard books, and it generally was written with a larger pen, leading to larger letters. Littera cursiva currens was used for textbooks and other unimportant books and it had very little standardization in forms.

Hybrida

Hybrida is also called bastarda (especially in France), and as its name suggests, is a hybrid form of the script. It is a mixture of textualis and cursiva, developed in the early 15th century. From textualis, it borrowed vertical ascenders, while from cursiva, it borrowed long ⟨f⟩ and ⟨ſ⟩, single-looped ⟨a⟩, and ⟨g⟩ with an open descender (similar to Carolingian forms).

Donatus-Kalender

The Donatus-Kalender (also known as Donatus-und-Kalender or D-K) is the name for the metal type design that Gutenberg used in his earliest surviving printed works, dating from the early 1450s. The name is taken from two works: the Ars grammatica of Aelius Donatus, a Latin grammar, and the Kalender (calendar).[7] It is a form of textura.

Blackletter typesetting

While an antiqua typeface is usually a compound of roman types and italic types since the 16th-century French typographers, the blackletter typefaces never developed a similar distinction. Instead, they use letterspacing (German Sperrung) for emphasis. When using that method, blackletter ligatures like ⟨ch⟩, ⟨ck⟩, ⟨tz⟩ or ⟨ſt⟩ remain together without additional letterspacing (⟨ſt⟩ is dissolved, though). The use of bold text for emphasis is also alien to blackletter typefaces.

Words from other languages, especially from Romance languages including Latin, are usually typeset in antiqua instead of blackletter.[8] Like that, single antiqua words or phrases may occur within a blackletter text. This does not apply, however, to loanwords that have been incorporated into the language.

National forms

England

Textualis

English blackletter developed from the form of Carolingian minuscule used there after the Norman Conquest, sometimes called "Romanesque minuscule". Textualis forms developed after 1190 and were used most often until approximately 1300, after which it became used mainly for de luxe manuscripts. English forms of blackletter have been studied extensively and may be divided into many categories. Textualis formata ("Old English" or "blackletter"), textualis prescissa (or textualis sine pedibus, as it generally lacks feet on its minims), textualis quadrata (or psalterialis) and semi-quadrata, and textualis rotunda are various forms of high-grade formata styles of blackletter.

The University of Oxford borrowed the littera parisiensis in the 13th century and early 14th century, and the littera oxoniensis form is almost indistinguishable from its Parisian counterpart; however, there are a few differences, such as the round final ⟨s⟩ forms, resembling the number ⟨8⟩, rather than the long ⟨s⟩ used in the final position in the Paris script.

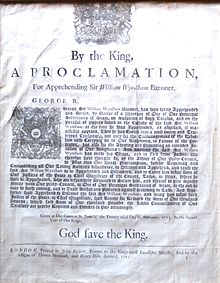

Printers of the late 15th and early 16th centuries commonly used blackletter typefaces, but under the influence of Renaissance tastes, Roman typefaces grew in popularity, until by about 1590 most presses had converted to them.[9] However, blackletter was considered to be more readily legible (especially by the less literate classes of society), and it therefore remained in use throughout the 17th century and into the 18th for documents intended for widespread dissemination, such as proclamations and Acts of Parliament, and for literature aimed at the common people, such as ballads, chivalric romances, and jokebooks.[10][11]

Chaucer's works had been printed in blackletter in the late 15th century, but were subsequently more usually printed in Roman type. Horace Walpole wrote in 1781 that "I am too, though a Goth, so modern a Goth that I hate the black letter, and I love Chaucer better in Dryden and Baskerville than in his own language and dress."[12]

Cursiva

English cursiva began to be used in the 13th century, and soon replaced littera oxoniensis as the standard university script. The earliest cursive blackletter form is Anglicana, a very round and looped script, which also had a squarer and angular counterpart, Anglicana formata. The formata form was used until the 15th century and also was used to write vernacular texts. An Anglicana bastarda form developed from a mixture of Anglicana and textualis, but by the 16th century, the principal cursive blackletter used in England was the Secretary script, which originated in Italy and came to England by way of France. Secretary script has a somewhat haphazard appearance, and its forms of the letters ⟨a⟩, ⟨g⟩, ⟨r⟩ and ⟨s⟩ are unique, unlike any forms in any other English script.

France

Textualis

French textualis was tall and narrow compared to other national forms, and was most fully developed in the late 13th century in Paris. In the 13th century there also was an extremely small version of textualis used to write miniature Bibles, known as "pearl script". Another form of French textualis in this century was the script developed at the University of Paris, littera parisiensis, which also is small in size and designed to be written quickly, not calligraphically.

Cursiva

French cursiva was used from the 13th to the 16th century, when it became highly looped, messy, and slanted. Bastarda, the "hybrid" mixture of cursiva and textualis, developed in the 15th century and was used for vernacular texts as well as Latin. A more angular form of bastarda was used in Burgundy, the lettre de forme or lettre bourgouignonne, for books of hours such as the Très Riches Heures of John, Duke of Berry.

Germany

Despite the frequent association of blackletter with German, the script was actually very slow to develop in German-speaking areas. It developed first in those areas closest to France and then spread to the east and south in the 13th century. The German-speaking areas are, however, where blackletter remained in use the longest.

Schwabacher typefaces dominated in Germany from about 1480 to 1530, and the style continued in use occasionally until the 20th century. Most importantly, all of the works of Martin Luther, leading to the Protestant Reformation, as well as the Apocalypse of Albrecht Dürer (1498), used this typeface. Johann Bämler, a printer from Augsburg, probably first used it as early as 1472. The origins of the name remain unclear; some assume that a typeface-carver from the village of Schwabach—one who worked externally and who thus became known as the Schwabacher—designed the typeface.

Textualis

German Textualis is usually very heavy and angular, and there are few characteristic features that are common to all occurrences of the script. One common feature is the use of the letter ⟨w⟩ for Latin ⟨vu⟩ or ⟨uu⟩. Textualis was first used in the 13th and 14th centuries, and subsequently become more elaborate and decorated, as well as being reserved used for liturgical works only.

Johann Gutenberg used a textualis typeface for his famous Gutenberg Bible in 1455. Schwabacher, a blackletter with more rounded letters, soon became the usual printed typeface, but it was replaced by Fraktur in the early 17th century.

Fraktur came into use when Emperor Maximilian I (1493–1519) established a series of books and had a new typeface created specifically for this purpose. In the 19th century, the use of antiqua alongside Fraktur increased, leading to the Antiqua-Fraktur dispute, which lasted until the Nazis abandoned Fraktur in 1941. Since it was so common, all kinds of blackletter tend to be called Fraktur in German.

Cursiva

German cursiva is similar to the cursive scripts in other areas, but forms of ⟨a⟩, ⟨s⟩ and other letters are more varied; here too, the letter ⟨w⟩ is often used. A hybrida form, which was basically cursiva with fewer looped letters and with similar square proportions as textualis, was used in the 15th and 16th centuries.

In the 18th century, the pointed quill was adopted for blackletter handwriting. In the early 20th century, the Sütterlin script was introduced in the schools.

Italy

Rotunda

Italian blackletter also is known as rotunda, as it was less angular than those produced by northern printing centers. The most common form of Italian rotunda was littera bononiensis, used at the University of Bologna in the 13th century. Biting is a common feature in rotunda, but breaking is not.

Italian Rotunda also is characterized by unique abbreviations, such as ⟨q⟩ with a line beneath the bow signifying qui, and unusual spellings, such as ⟨x⟩ for ⟨s⟩ (milex rather than miles).

Cursiva

Italian cursive developed in the 13th century from scripts used by notaries. The more calligraphic form is known as minuscola cancelleresca italiana (or simply cancelleresca, chancery hand), which developed into a book hand, a script used for writing books rather than charters, in the 14th century. Cancelleresca influenced the development of bastarda in France and secretary hand in England.

The Netherlands

Textualis

A textualis form, commonly known as Gotisch or "Gothic script", was used for general publications from the fifteenth century on, but became restricted to official documents and religious publications during the seventeenth century. Its use persisted into the nineteenth century for editions of the State Translation of the Bible, but otherwise became obsolete.

Unicode

Mathematical blackletter characters are separately encoded in Unicode in the Mathematical alphanumeric symbols range at U+1D504-1D537 and U+1D56C-1D59F (bold), except for individual letters already encoded in the Letterlike Symbols range (plus long s at U+017F).[13][14] Fonts supporting the range include Code2001, Cambria Math, and Quivira (textura style).

This block of characters is intended for use in setting mathematical texts, which contrast blackletter characters with other letter styles.[15] Outside of mathematics, the character set has seen some limited decorative use, but it lacks punctuation and other characters necessary for running text, and the Unicode standard for setting non-mathematical material in blackletter is to use ordinary Latin code points with a dedicated blackletter font.

Mathematical Fraktur:

- 𝔄 𝔅 ℭ 𝔇 𝔈 𝔉 𝔊 ℌ ℑ 𝔍 𝔎 𝔏 𝔐 𝔑 𝔒 𝔓 𝔔 ℜ 𝔖 𝔗 𝔘 𝔙 𝔚 𝔛 𝔜 ℨ

𝔞 𝔟 𝔠 𝔡 𝔢 𝔣 𝔤 𝔥 𝔦 𝔧 𝔨 𝔩 𝔪 𝔫 𝔬 𝔭 𝔮 𝔯 𝔰 𝔱 𝔲 𝔳 𝔴 𝔵 𝔶 𝔷

Mathematical Bold Fraktur:

- 𝕬 𝕭 𝕮 𝕯 𝕰 𝕱 𝕲 𝕳 𝕴 𝕵 𝕶 𝕷 𝕸 𝕹 𝕺 𝕻 𝕼 𝕽 𝕾 𝕿 𝖀 𝖁 𝖂 𝖃 𝖄 𝖅

𝖆 𝖇 𝖈 𝖉 𝖊 𝖋 𝖌 𝖍 𝖎 𝖏 𝖐 𝖑 𝖒 𝖓 𝖔 𝖕 𝖖 𝖗 𝖘 𝖙 𝖚 𝖛 𝖜 𝖝 𝖞 𝖟

Note: (The above may not render fully in all web browsers.)

See also

- Antiqua (typeface class)

- Asemic writing

- Bastarda

- Book hand

- Calligraphy

- Chancery hand

- Court hand (also known as common law hand, Anglicana, cursiva antiquior, or charter hand)

- Cursive

- Hand (writing style)

- Handwriting

- History of writing

- Italic script

- Law hand

- Paleography

- Penmanship

- Ronde script (calligraphy)

- Rotunda (script)

- Round hand

- Secretary hand

References

The memorandum itself is typed in Antiqua, but the NSDAP letterhead is printed in Fraktur.

"For general attention, on behalf of the Führer, I make the following announcement:

It is wrong to regard or to describe the so-called Gothic script as a German script. In reality, the so-called Gothic script consists of Schwabach Jew letters. Just as they later took control of the newspapers, upon the introduction of printing the Jews residing in Germany took control of the printing presses and thus in Germany the Schwabach Jew letters were forcefully introduced.

Today the Führer, talking with Herr Reichsleiter Amann and Herr Book Publisher Adolf Müller, has decided that in the future the Antiqua script is to be described as normal script. All printed materials are to be gradually converted to this normal script. As soon as is feasible in terms of textbooks, only the normal script will be taught in village and state schools.

The use of the Schwabach Jew letters by officials will in future cease; appointment certifications for functionaries, street signs, and so forth will in future be produced only in normal script.

On behalf of the Führer, Herr Reichsleiter Amann will in future convert those newspapers and periodicals that already have foreign distribution, or whose foreign distribution is desired, to normal script".

- "22.2 Letterlike Symbols, Mathematical Alphanumeric Symbols". The Unicode Standard, Version 14.0 (PDF). Mountain View, CA: Unicode, Inc. September 2021.

Further reading

- Bernhard Bischoff, Latin Palaeography: Antiquity and the Middle Ages, Cambridge University Press, 1989.

- Bain, Peter; Shaw, Paul, eds. (1998). Blackletter: type and national identity. Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art. Princeton Architectural Press. ISBN 978-1-56898-125-3.

External links

- 'Manual of Latin Palaeography' (A comprehensive PDF file containing 82 pages profusely illustrated, June 2014).

- Learn Blackletter Online

- Association for the German Script and Language

- Pfeffer Simpelgotisch A simple OpenType blackletter font setting ſ and s by itself

- London Review of Books article about blackletter fonts and font history in general

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blackletter

In common law legal systems, black-letter law refers to well-established legal rules that are no longer subject to reasonable dispute.[1] For example, it is "black-letter law" that the formation of a contract requires consideration, or that the registration of a trademark requires established use in the course of trade. Black-letter law can be contrasted with legal theory or unsettled legal issues.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black_letter_law

| Black | |

|---|---|

Clockwise, from top left: Anubis statue; American black bear; Galaxy NGC 406; The Supreme Court of the United States; Portrait painting of Queen Victoria. | |

| Hex triplet | #000000 |

| sRGBB (r, g, b) | (0, 0, 0) |

| HSV (h, s, v) | (0°, 0%, 0%) |

| CIELChuv (L, C, h) | (0, 0, 0°) |

| Source | HTML/CSS[1] |

| B: Normalized to [0–255] (byte) H: Normalized to [0–100] (hundred) | |

Black is a color which results from the absence or complete absorption of visible light. It is an achromatic color, without hue, like white and grey.[2] It is often used symbolically or figuratively to represent darkness.[3] Black and white have often been used to describe opposites such as good and evil, the Dark Ages versus Age of Enlightenment, and night versus day. Since the Middle Ages, black has been the symbolic color of solemnity and authority, and for this reason it is still commonly worn by judges and magistrates.[3]

Black was one of the first colors used by artists in Neolithic cave paintings.[4] It was used in ancient Egypt and Greece as the color of the underworld.[5] In the Roman Empire, it became the color of mourning, and over the centuries it was frequently associated with death, evil, witches, and magic.[6] In the 14th century, it was worn by royalty, clergy, judges, and government officials in much of Europe. It became the color worn by English romantic poets, businessmen and statesmen in the 19th century, and a high fashion color in the 20th century.[3] According to surveys in Europe and North America, it is the color most commonly associated with mourning, the end, secrets, magic, force, violence, fear, evil, and elegance.[7]

Black is the most common ink color used for printing books, newspapers and documents, as it provides the highest contrast with white paper and thus is the easiest color to read. Similarly, black text on a white screen is the most common format used on computer screens.[8] As of September 2019, the darkest material is made by MIT engineers from vertically aligned carbon nanotubes.[9]

Etymology

The word black comes from Old English blæc ("black, dark", also, "ink"), from Proto-Germanic *blakkaz ("burned"), from Proto-Indo-European *bhleg- ("to burn, gleam, shine, flash"), from base *bhel- ("to shine"), related to Old Saxon blak ("ink"), Old High German blach ("black"), Old Norse blakkr ("dark"), Dutch blaken ("to burn"), and Swedish bläck ("ink"). More distant cognates include Latin flagrare ("to blaze, glow, burn"), and Ancient Greek phlegein ("to burn, scorch"). The Ancient Greeks sometimes used the same word to name different colors, if they had the same intensity. Kuanos' could mean both dark blue and black.[10] The Ancient Romans had two words for black: ater was a flat, dull black, while niger was a brilliant, saturated black. Ater has vanished from the vocabulary, but niger was the source of the country name Nigeria,[11] the English word Negro, and the word for "black" in most modern Romance languages (French: noir; Spanish and Portuguese: negro; Italian: nero; Romanian: negru).

Old High German also had two words for black: swartz for dull black and blach for a luminous black. These are parallelled in Middle English by the terms swart for dull black and blaek for luminous black. Swart still survives as the word swarthy, while blaek became the modern English black.[10] The former is cognate with the words used for black in most modern Germanic languages aside from English (German: schwarz, Dutch: zwart, Swedish: svart, Danish: sort, Icelandic: svartr).[12] In heraldry, the word used for the black color is sable,[13] named for the black fur of the sable, an animal.

Art

Prehistoric

Black was one of the first colors used in art. The Lascaux Cave in France contains drawings of bulls and other animals drawn by paleolithic artists between 18,000 and 17,000 years ago. They began by using charcoal, and later achieved darker pigments by burning bones or grinding a powder of manganese oxide.[10]

Ancient

For the ancient Egyptians, black had positive associations; being the color of fertility and the rich black soil flooded by the Nile. It was the color of Anubis, the god of the underworld, who took the form of a black jackal, and offered protection against evil to the dead. To ancient Greeks, black represented the underworld, separated from the living by the river Acheron, whose water ran black. Those who had committed the worst sins were sent to Tartarus, the deepest and darkest level. In the center was the palace of Hades, the king of the underworld, where he was seated upon a black ebony throne. Black was one of the most important colors used by ancient Greek artists. In the 6th century BC, they began making black-figure pottery and later red figure pottery, using a highly original technique. In black-figure pottery, the artist would paint figures with a glossy clay slip on a red clay pot. When the pot was fired, the figures painted with the slip would turn black, against a red background. Later they reversed the process, painting the spaces between the figures with slip. This created magnificent red figures against a glossy black background.[14]

In the social hierarchy of ancient Rome, purple was the color reserved for the Emperor; red was the color worn by soldiers (red cloaks for the officers, red tunics for the soldiers); white the color worn by the priests, and black was worn by craftsmen and artisans. The black they wore was not deep and rich; the vegetable dyes used to make black were not solid or lasting, so the blacks often faded to gray or brown.[15]

In Latin, the word for black, ater and to darken, atere, were associated with cruelty, brutality and evil. They were the root of the English words "atrocious" and "atrocity".[16] Black was also the Roman color of death and mourning. In the 2nd century BC Roman magistrates began to wear a dark toga, called a toga pulla, to funeral ceremonies. Later, under the Empire, the family of the deceased also wore dark colors for a long period; then, after a banquet to mark the end of mourning, exchanged the black for a white toga. In Roman poetry, death was called the hora nigra, the black hour.[10]

The German and Scandinavian peoples worshipped their own goddess of the night, Nótt, who crossed the sky in a chariot drawn by a black horse. They also feared Hel, the goddess of the kingdom of the dead, whose skin was black on one side and red on the other. They also held sacred the raven. They believed that Odin, the king of the Nordic pantheon, had two black ravens, Huginn and Muninn, who served as his agents, traveling the world for him, watching and listening.[17]

Statue of Anubis, guardian of the underworld, from the tomb of Tutankhamun.

Greek black-figure pottery. Ajax and Achilles playing a game, about 540–530 BC. (Vatican Museums).

Red-figure pottery with black background. Portrait of Thetis, about 470–480 BC. (The Louvre)

Postclassical

In the early Middle Ages, black was commonly associated with darkness and evil. In Medieval paintings, the devil was usually depicted as having human form, but with wings and black skin or hair.[18]

12th and 13th centuries

In fashion, black did not have the prestige of red, the color of the nobility. It was worn by Benedictine monks as a sign of humility and penitence. In the 12th century a famous theological dispute broke out between the Cistercian monks, who wore white, and the Benedictines, who wore black. A Benedictine abbot, Pierre the Venerable, accused the Cistercians of excessive pride in wearing white instead of black. Saint Bernard of Clairvaux, the founder of the Cistercians responded that black was the color of the devil, hell, "of death and sin", while white represented "purity, innocence and all the virtues".[19]

Black symbolized both power and secrecy in the medieval world. The emblem of the Holy Roman Empire of Germany was a black eagle. The black knight in the poetry of the Middle Ages was an enigmatic figure, hiding his identity, usually wrapped in secrecy.[20]

Black ink, invented in China, was traditionally used in the Middle Ages for writing, for the simple reason that black was the darkest color and therefore provided the greatest contrast with white paper or parchment, making it the easiest color to read. It became even more important in the 15th century, with the invention of printing. A new kind of ink, printer's ink, was created out of soot, turpentine and walnut oil. The new ink made it possible to spread ideas to a mass audience through printed books, and to popularize art through black and white engravings and prints. Because of its contrast and clarity, black ink on white paper continued to be the standard for printing books, newspapers and documents; and for the same reason black text on a white background is the most common format used on computer screens.[8]

The Italian painter Duccio di Buoninsegna showed Christ expelling the Devil, shown covered with bristly black hair (1308–11).

The 15th-century painting of the Last Judgement by Fra Angelico (1395–1455) depicted hell with a vivid black devil devouring sinners.

Portrait of a monk of the Benedictine Order (1484)

Gutenberg Bible (1451–1452). Black ink was used for printing books, because it provided the greatest contrast with the white paper and was the clearest and easiest color to read.

14th and 15th centuries

In the early Middle Ages, princes, nobles and the wealthy usually wore bright colors, particularly scarlet cloaks from Italy. Black was rarely part of the wardrobe of a noble family. The one exception was the fur of the sable. This glossy black fur, from an animal of the marten family, was the finest and most expensive fur in Europe. It was imported from Russia and Poland and used to trim the robes and gowns of royalty.

In the 14th century, the status of black began to change. First, high-quality black dyes began to arrive on the market, allowing garments of a deep, rich black. Magistrates and government officials began to wear black robes, as a sign of the importance and seriousness of their positions. A third reason was the passage of sumptuary laws in some parts of Europe which prohibited the wearing of costly clothes and certain colors by anyone except members of the nobility. The famous bright scarlet cloaks from Venice and the peacock blue fabrics from Florence were restricted to the nobility. The wealthy bankers and merchants of northern Italy responded by changing to black robes and gowns, made with the most expensive fabrics.[21]

The change to the more austere but elegant black was quickly picked up by the kings and nobility. It began in northern Italy, where the Duke of Milan and the Count of Savoy and the rulers of Mantua, Ferrara, Rimini and Urbino began to dress in black. It then spread to France, led by Louis I, Duke of Orleans, younger brother of King Charles VI of France. It moved to England at the end of the reign of King Richard II (1377–1399), where all the court began to wear black. In 1419–20, black became the color of the powerful Duke of Burgundy, Philip the Good. It moved to Spain, where it became the color of the Spanish Habsburgs, of Charles V and of his son, Philip II of Spain (1527–1598). European rulers saw it as the color of power, dignity, humility and temperance. By the end of the 16th century, it was the color worn by almost all the monarchs of Europe and their courts.[22]

Philip the Good in about 1450, by Rogier van der Weyden

Portrait of a Young Woman by Petrus Christus (about 1470)

Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor (1500–1558), by Titian

Portrait of Philip II of Spain (1527–1598)

Modern

16th and 17th centuries

While black was the color worn by the Catholic rulers of Europe, it was also the emblematic color of the Protestant Reformation in Europe and the Puritans in England and America. John Calvin, Philip Melanchthon and other Protestant theologians denounced the richly colored and decorated interiors of Roman Catholic churches. They saw the color red, worn by the Pope and his Cardinals, as the color of luxury, sin, and human folly.[23] In some northern European cities, mobs attacked churches and cathedrals, smashed the stained glass windows and defaced the statues and decoration. In Protestant doctrine, clothing was required to be sober, simple and discreet. Bright colors were banished and replaced by blacks, browns and grays; women and children were recommended to wear white.[24]

In the Protestant Netherlands, Rembrandt used this sober new palette of blacks and browns to create portraits whose faces emerged from the shadows expressing the deepest human emotions. The Catholic painters of the Counter-Reformation, like Rubens, went in the opposite direction; they filled their paintings with bright and rich colors. The new Baroque churches of the Counter-Reformation were usually shining white inside and filled with statues, frescoes, marble, gold and colorful paintings, to appeal to the public. But European Catholics of all classes, like Protestants, eventually adopted a sober wardrobe that was mostly black, brown and gray.[25]

Swiss theologian John Calvin denounced the bright colors worn by Roman Catholic priests, and colorful decoration of churches.

Increase Mather, an American Puritan clergyman (1688).

Rembrandt, Self-portrait (1659)

John, Duke of Braganza, later King John IV of Portugal (1628)

Black painted suit of German armor crafted circa 1600. As with many outfits, black in the piece is used to contrast against lighter colors.[26]

In the second part of the 17th century, Europe and America experienced an epidemic of fear of witchcraft. People widely believed that the devil appeared at midnight in a ceremony called a Black Mass or black sabbath, usually in the form of a black animal, often a goat, a dog, a wolf, a bear, a deer or a rooster, accompanied by their familiar spirits, black cats, serpents and other black creatures. This was the origin of the widespread superstition about black cats and other black animals. In medieval Flanders, in a ceremony called Kattenstoet, black cats were thrown from the belfry of the Cloth Hall of Ypres to ward off witchcraft.[27]

Witch trials were common in both Europe and America during this period. During the notorious Salem witch trials in New England in 1692–93, one of those on trial was accused of being able turn into a "black thing with a blue cap," and others of having familiars in the form of a black dog, a black cat and a black bird.[28] Nineteen women and men were hanged as witches.[29]

An English manual on witch-hunting (1647), showing a witch with her familiar spirits

Black cats have been accused for centuries of being the familiar spirits of witches or of bringing bad luck.

18th and 19th centuries

In the 18th century, during the European Age of Enlightenment, black receded as a fashion color. Paris became the fashion capital, and pastels, blues, greens, yellow and white became the colors of the nobility and upper classes. But after the French Revolution, black again became the dominant color.

Black was the color of the industrial revolution, largely fueled by coal, and later by oil. Thanks to coal smoke, the buildings of the large cities of Europe and America gradually turned black. By 1846 the industrial area of the West Midlands of England was "commonly called 'the Black Country'”.[30] Charles Dickens and other writers described the dark streets and smoky skies of London, and they were vividly illustrated in the engravings of French artist Gustave Doré.

A different kind of black was an important part of the romantic movement in literature. Black was the color of melancholy, the dominant theme of romanticism. The novels of the period were filled with castles, ruins, dungeons, storms, and meetings at midnight. The leading poets of the movement were usually portrayed dressed in black, usually with a white shirt and open collar, and a scarf carelessly over their shoulder, Percy Bysshe Shelley and Lord Byron helped create the enduring stereotype of the romantic poet.

The invention of inexpensive synthetic black dyes and the industrialization of the textile industry meant that high-quality black clothes were available for the first time to the general population. In the 19th century black gradually became the most popular color of business dress of the upper and middle classes in England, the Continent, and America.

Black dominated literature and fashion in the 19th century, and played a large role in painting. James McNeill Whistler made the color the subject of his most famous painting, Arrangement in grey and black number one (1871), better known as Whistler's Mother.[31]

Some 19th-century French painters had a low opinion of black: "Reject black," Paul Gauguin said, "and that mix of black and white they call gray. Nothing is black, nothing is gray."[32] But Édouard Manet used blacks for their strength and dramatic effect. Manet's portrait of painter Berthe Morisot was a study in black which perfectly captured her spirit of independence. The black gave the painting power and immediacy; he even changed her eyes, which were green, to black to strengthen the effect.[33] Henri Matisse quoted the French impressionist Pissarro telling him, "Manet is stronger than us all – he made light with black."[34]

Pierre-Auguste Renoir used luminous blacks, especially in his portraits. When someone told him that black was not a color, Renoir replied: "What makes you think that? Black is the queen of colors. I always detested Prussian blue. I tried to replace black with a mixture of red and blue, I tried using cobalt blue or ultramarine, but I always came back to ivory black."[35]

Vincent van Gogh used black lines to outline many of the objects in his paintings, such as the bed in the famous painting of his bedroom. making them stand apart. His painting of black crows over a cornfield, painted shortly before he died, was particularly agitated and haunting. In the late 19th century, black also became the color of anarchism. (See the section political movements.)

Portrait of Empress Teresa Cristina of Brazil (circa 1870)

Arrangement in Grey and Black Number 1 (1871) by James McNeill Whistler better known as Whistler's Mother.

Le Bal de l'Opera (1873) by Édouard Manet, shows the dominance of black in Parisian evening dress.

The Theater Box (1874) by Pierre-Auguste Renoir, captured the luminosity of black fabric in the light.

Wheat Field with Crows (1890), one of the last paintings of Vincent van Gogh, captures his agitated state of mind.

20th and 21st centuries

In the 20th century, black was the color of Italian and German fascism. (See the section political movements.)

In art, black regained some of the territory that it had lost during the 19th century. The Russian painter Kasimir Malevich, a member of the Suprematist movement, created the Black Square in 1915, is widely considered the first purely abstract painting.[36] He wrote, "The painted work is no longer simply the imitation of reality, but is this very reality ... It is not a demonstration of ability, but the materialization of an idea."[37]

Black was also appreciated by Henri Matisse. "When I didn't know what color to put down, I put down black," he said in 1945. "Black is a force: I used black as ballast to simplify the construction ... Since the impressionists it seems to have made continuous progress, taking a more and more important part in color orchestration, comparable to that of the double bass as a solo instrument."[38]

In the 1950s, black came to be a symbol of individuality and intellectual and social rebellion, the color of those who didn't accept established norms and values. In Paris, it was worn by Left-Bank intellectuals and performers such as Juliette Gréco, and by some members of the Beat Movement in New York and San Francisco.[39] Black leather jackets were worn by motorcycle gangs such as the Hells Angels and street gangs on the fringes of society in the United States. Black as a color of rebellion was celebrated in such films as The Wild One, with Marlon Brando. By the end of the 20th century, black was the emblematic color of the punk subculture punk fashion, and the goth subculture. Goth fashion, which emerged in England in the 1980s, was inspired by Victorian era mourning dress.

In men's fashion, black gradually ceded its dominance to navy blue, particularly in business suits. Black evening dress and formal dress in general were worn less and less. In 1960, John F. Kennedy was the last American President to be inaugurated wearing formal dress; President Lyndon Johnson and all his successors were inaugurated wearing business suits.

Women's fashion was revolutionized and simplified in 1926 by the French designer Coco Chanel, who published a drawing of a simple black dress in Vogue magazine. She famously said, "A woman needs just three things; a black dress, a black sweater, and, on her arm, a man she loves."[39] French designer Jean Patou also followed suit by creating a black collection in 1929.[40] Other designers contributed to the trend of the little black dress. The Italian designer Gianni Versace said, "Black is the quintessence of simplicity and elegance," and French designer Yves Saint Laurent said, "black is the liaison which connects art and fashion.[39] One of the most famous black dresses of the century was designed by Hubert de Givenchy and was worn by Audrey Hepburn in the 1961 film Breakfast at Tiffany's.

The American civil rights movement in the 1950s was a struggle for the political equality of African Americans. It developed into the Black Power movement in the early 1960s until the late 1980s, and the Black Lives Matter movement in the 2010s and 2020s. It also popularized the slogan "Black is Beautiful".

The Black Square (1915) by Kazimir Malevich is considered the first purely abstract painting (Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow).

Queen Marie of Romania (early 1920s) by Constantin Pascali

The goth fashion model Lady Amaranth. Goth fashion was inspired by British Victorian mourning costumes.

Science

Physics

In the visible spectrum, black is the result of the absorption of all colors. Black can be defined as the visual impression experienced when no visible light reaches the eye. Pigments or dyes that absorb light rather than reflect it back to the eye "look black". A black pigment can, however, result from a combination of several pigments that collectively absorb all colors. If appropriate proportions of three primary pigments are mixed, the result reflects so little light as to be called "black". This provides two superficially opposite but actually complementary descriptions of black. Black is the absorption of all colors of light, or an exhaustive combination of multiple colors of pigment.

In physics, a black body is a perfect absorber of light, but, by a thermodynamic rule, it is also the best emitter. Thus, the best radiative cooling, out of sunlight, is by using black paint, though it is important that it be black (a nearly perfect absorber) in the infrared as well. In elementary science, far ultraviolet light is called "black light" because, while itself unseen, it causes many minerals and other substances to fluoresce.

Absorption of light is contrasted by transmission, reflection and diffusion, where the light is only redirected, causing objects to appear transparent, reflective or white respectively. A material is said to be black if most incoming light is absorbed equally in the material. Light (electromagnetic radiation in the visible spectrum) interacts with the atoms and molecules, which causes the energy of the light to be converted into other forms of energy, usually heat. This means that black surfaces can act as thermal collectors, absorbing light and generating heat (see Solar thermal collector).

As of September 2019, the darkest material is made from vertically aligned carbon nanotubes. The material was grown by MIT engineers and was reported to have a 99.995% absorption rate of any incoming light.[9] This surpasses any former darkest materials including Vantablack, which has a peak absorption rate of 99.965% in the visible spectrum.[42]

Chemistry

Pigments

The earliest pigments used by Neolithic man were charcoal, red ocher and yellow ocher. The black lines of cave art were drawn with the tips of burnt torches made of a wood with resin.[43] Different charcoal pigments were made by burning different woods and animal products, each of which produced a different tone. The charcoal would be ground and then mixed with animal fat to make the pigment.

- Vine black was produced in Roman times by burning the cut branches of grapevines. It could also be produced by burning the remains of the crushed grapes, which were collected and dried in an oven. According to the historian Vitruvius, the deepness and richness of the black produced corresponded to the quality of the wine. The finest wines produced a black with a bluish tinge the color of indigo.

The 15th-century painter Cennino Cennini described how this pigment was made during the Renaissance in his famous handbook for artists: "...there is a black which is made from the tendrils of vines. And these tendrils need to be burned. And when they have been burned, throw some water onto them and put them out and then mull them in the same way as the other black. And this is a lean and black pigment and is one of the perfect pigments that we use."[44]

Cennini also noted that "There is another black which is made from burnt almond shells or peaches and this is a perfect, fine black."[44] Similar fine blacks were made by burning the pits of the peach, cherry or apricot. The powdered charcoal was then mixed with gum arabic or the yellow of an egg to make a paint.

Different civilizations burned different plants to produce their charcoal pigments. The Inuit of Alaska used wood charcoal mixed with the blood of seals to paint masks and wooden objects. The Polynesians burned coconuts to produce their pigment.

- Lamp black was used as a pigment for painting and frescoes, as a dye for fabrics, and in some societies for making tattoos. The 15th century Florentine painter Cennino Cennini described how it was made during the Renaissance: "... take a lamp full of linseed oil and fill the lamp with the oil and light the lamp. Then place it, lit, under a thoroughly clean pan and make sure that the flame from the lamp is two or three fingers from the bottom of the pan. The smoke that comes off the flame will hit the bottom of the pan and gather, becoming thick. Wait a bit. take the pan and brush this pigment (that is, this smoke) onto paper or into a pot with something. And it is not necessary to mull or grind it because it is a very fine pigment. Re-fill the lamp with the oil and put it under the pan like this several times and, in this way, make as much of it as is necessary."[44] This same pigment was used by Indian artists to paint the Ajanta Caves, and as dye in ancient Japan.[43]

- Ivory black, also known as bone char, was originally produced by burning ivory and mixing the resulting charcoal powder with oil. The color is still made today, but ordinary animal bones are substituted for ivory.

- Mars black is a black pigment made of synthetic iron oxides. It is commonly used in water-colors and oil painting. It takes its name from Mars, the god of war and patron of iron.

Dyes

Good-quality black dyes were not known until the middle of the 14th century. The most common early dyes were made from bark, roots or fruits of different trees; usually walnuts, chestnuts, or certain oak trees. The blacks produced were often more gray, brown or bluish. The cloth had to be dyed several times to darken the color. One solution used by dyers was add to the dye some iron filings, rich in iron oxide, which gave a deeper black. Another was to first dye the fabric dark blue, and then to dye it black.

A much richer and deeper black dye was eventually found made from the oak apple or "gall-nut". The gall-nut is a small round tumor which grows on oak and other varieties of trees. They range in size from 2–5 cm, and are caused by chemicals injected by the larva of certain kinds of gall wasp in the family Cynipidae.[45] The dye was very expensive; a great quantity of gall-nuts were needed for a very small amount of dye. The gall-nuts which made the best dye came from Poland, eastern Europe, the near east and North Africa. Beginning in about the 14th century, dye from gall-nuts was used for clothes of the kings and princes of Europe.[46]

Another important source of natural black dyes from the 17th century onwards was the logwood tree, or Haematoxylum campechianum, which also produced reddish and bluish dyes. It is a species of flowering tree in the legume family, Fabaceae, that is native to southern Mexico and northern Central America.[47] The modern nation of Belize grew from 17th century English logwood logging camps.

Since the mid-19th century, synthetic black dyes have largely replaced natural dyes. One of the important synthetic blacks is Nigrosin, a mixture of synthetic black dyes (CI 50415, Solvent black 5) made by heating a mixture of nitrobenzene, aniline and aniline hydrochloride in the presence of a copper or iron catalyst. Its main industrial uses are as a colorant for lacquers and varnishes and in marker-pen inks.[48]

Inks

The first known inks were made by the Chinese, and date back to the 23rd century B.C. They used natural plant dyes and minerals such as graphite ground with water and applied with an ink brush. Early Chinese inks similar to the modern inkstick have been found dating to about 256 BC at the end of the Warring States period. They were produced from soot, usually produced by burning pine wood, mixed with animal glue. To make ink from an inkstick, the stick is continuously ground against an inkstone with a small quantity of water to produce a dark liquid which is then applied with an ink brush. Artists and calligraphists could vary the thickness of the resulting ink by reducing or increasing the intensity and time of ink grinding. These inks produced the delicate shading and subtle or dramatic effects of Chinese brush painting.[49]

India ink (or "Indian ink" in British English) is a black ink once widely used for writing and printing and now more commonly used for drawing, especially when inking comic books and comic strips. The technique of making it probably came from China. India ink has been in use in India since at least the 4th century BC, where it was called masi. In India, the black color of the ink came from bone char, tar, pitch and other substances.[50][51]

The ancient Romans had a black writing ink they called atramentum librarium.[52] Its name came from the Latin word atrare, which meant to make something black. (This was the same root as the English word atrocious.) It was usually made, like India ink, from soot, although one variety, called atramentum elephantinum, was made by burning the ivory of elephants.[53]

Gall-nuts were also used for making fine black writing ink. Iron gall ink (also known as iron gall nut ink or oak gall ink) was a purple-black or brown-black ink made from iron salts and tannic acids from gall nut. It was the standard writing and drawing ink in Europe, from about the 12th century to the 19th century, and remained in use well into the 20th century.

A Chinese inkstick, in the form of lotus flowers and blossoms. Inksticks are used in Chinese calligraphy and brush painting.

Ivory black or bone char, a natural black pigment made by burning animal bones.

The oak apple or gall-nut, a tumor growing on oak trees, was the main source of black dye and black writing ink from the 14th century until the 19th century.

The industrial production of lamp black, made by producing, collecting and refining soot, in 1906.

Astronomy

- A black hole is a region of spacetime where gravity prevents anything, including light, from escaping.[54] The theory of general relativity predicts that a sufficiently compact mass will deform spacetime to form a black hole. Around a black hole there is a mathematically defined boundary called an event horizon that marks the point of no return. It is called "black" because it absorbs all the light that hits the horizon, reflecting nothing, just like a perfect black body in thermodynamics.[55][56] Black holes of stellar mass are expected to form when very massive stars collapse at the end of their life cycle. After a black hole has formed it can continue to grow by absorbing mass from its surroundings. By absorbing other stars and merging with other black holes, supermassive black holes of millions of solar masses may form. There is general consensus that supermassive black holes exist in the centers of most galaxies. Although a black hole itself is black, infalling material forms an accretion disk, one of the brightest types of object in the universe.

- Black-body radiation refers to the radiation coming from a body at a given temperature where all incoming energy (light) is converted to heat.

- Black sky refers to the appearance of space as one emerges from Earth's atmosphere.

An illustration of Olbers' paradox (see below)

Why the night sky and space are black – Olbers' paradox

The fact that outer space is black is sometimes called Olbers' paradox. In theory, because the universe is full of stars, and is believed to be infinitely large, it would be expected that the light of an infinite number of stars would be enough to brilliantly light the whole universe all the time. However, the background color of outer space is black. This contradiction was first noted in 1823 by German astronomer Heinrich Wilhelm Matthias Olbers, who posed the question of why the night sky was black.

The current accepted answer is that, although the universe may be infinitely large, it is not infinitely old. It is thought to be about 13.8 billion years old, so we can only see objects as far away as the distance light can travel in 13.8 billion years. Light from stars farther away has not reached Earth, and cannot contribute to making the sky bright. Furthermore, as the universe is expanding, many stars are moving away from Earth. As they move, the wavelength of their light becomes longer, through the Doppler effect, and shifts toward red, or even becomes invisible. As a result of these two phenomena, there is not enough starlight to make space anything but black.[57]

The daytime sky on Earth is blue because light from the Sun strikes molecules in Earth's atmosphere scattering light in all directions. Blue light is scattered more than other colors, and reaches the eye in greater quantities, making the daytime sky appear blue. This is known as Rayleigh scattering.

The nighttime sky on Earth is black because the part of Earth experiencing night is facing away from the Sun, the light of the Sun is blocked by Earth itself, and there is no other bright nighttime source of light in the vicinity. Thus, there is not enough light to undergo Rayleigh scattering and make the sky blue. On the Moon, on the other hand, because there is virtually no atmosphere to scatter the light, the sky is black both day and night. This also holds true for other locations without an atmosphere, such as Mercury.

Biology

The black mamba of Africa is one of the most venomous snakes, as well as the fastest-moving snake in the world.

The black widow spider, or latrodectus, The females frequently eat their male partners after mating. The female's venom is at least three times more potent than that of the males, making a male's self-defense bite ineffective.

A black panther is actually a melanistic leopard or jaguar, the result of an excess of melanin in their skin caused by a recessive gene.

Culture

In China, the color black is associated with water, one of the five fundamental elements believed to compose all things; and with winter, cold, and the direction north, usually symbolized by a black tortoise. It is also associated with disorder, including the positive disorder which leads to change and new life. When the first Emperor of China Qin Shi Huang seized power from the Zhou Dynasty, he changed the Imperial color from red to black, saying that black extinguished red. Only when the Han Dynasty appeared in 206 BC was red restored as the imperial color.[59]

In Japan, black is associated with mystery, the night, the unknown, the supernatural, the invisible and death. Combined with white, it can symbolize intuition.[60] In 10th and 11th century Japan, it was believed that wearing black could bring misfortune. It was worn at court by those who wanted to set themselves apart from the established powers or who had renounced material possessions.[61]

In Japan black can also symbolize experience, as opposed to white, which symbolizes naiveté. The black belt in martial arts symbolizes experience, while a white belt is worn by novices.[62] Japanese men traditionally wear a black kimono with some white decoration on their wedding day.

In Indonesia black is associated with depth, the subterranean world, demons, disaster, and the left hand. When black is combined with white, however, it symbolizes harmony and equilibrium.[63]

Political movements

Anarchism is a political philosophy, most popular in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, which holds that governments and capitalism are harmful and undesirable. The symbols of anarchism was usually either a black flag or a black letter A. More recently it is usually represented with a bisected red and black flag, to emphasise the movement's socialist roots in the First International. Anarchism was most popular in Spain, France, Italy, Ukraine and Argentina. There were also small but influential movements in the United States and Russia. In the latter, the movement initially allied itself with the Bolsheviks.[64]

The Black Army[citation needed] was a collection of anarchist military units which fought in the Russian Civil War, sometimes on the side of the Bolshevik Red Army, and sometimes for the opposing White Army. It was officially known as the Revolutionary Insurgent Army of Ukraine, and it was under the command of the anarchist Nestor Makhno.

Fascism. The Blackshirts (Italian: camicie nere, 'CCNN) were Fascist paramilitary groups in Italy during the period immediately following World War I and until the end of World War II. The Blackshirts were officially known as the Voluntary Militia for National Security (Milizia Volontaria per la Sicurezza Nazionale, or MVSN).

Inspired by the black uniforms of the Arditi, Italy's elite storm troops of World War I, the Fascist Blackshirts were organized by Benito Mussolini as the military tool of his political movement.[65] They used violence and intimidation against Mussolini's opponents. The emblem of the Italian fascists was a black flag with fasces, an axe in a bundle of sticks, an ancient Roman symbol of authority. Mussolini came to power in 1922 through his March on Rome with the blackshirts.

Black was also adopted by Adolf Hitler and the Nazis in Germany. Red, white and black were the colors of the flag of the German Empire from 1870 to 1918. In Mein Kampf, Hitler explained that they were "revered colors expressive of our homage to the glorious past." Hitler also wrote that "the new flag ... should prove effective as a large poster" because "in hundreds of thousands of cases a really striking emblem may be the first cause of awakening interest in a movement." The black swastika was meant to symbolize the Aryan race, which, according to the Nazis, "was always anti-Semitic and will always be anti-Semitic."[66] Several designs by a number of different authors were considered, but the one adopted in the end was Hitler's personal design.[67] Black became the color of the uniform of the SS, the Schutzstaffel or "defense corps", the paramilitary wing of the Nazi Party, and was worn by SS officers from 1932 until the end of World War II.

The Nazis used a black triangle to symbolize anti-social elements. The symbol originates from Nazi concentration camps, where every prisoner had to wear one of the Nazi concentration camp badges on their jacket, the color of which categorized them according to "their kind". Many Black Triangle prisoners were either mentally disabled or mentally ill. The homeless were also included, as were alcoholics, the Romani people, the habitually "work-shy", prostitutes, draft dodgers and pacifists.[68] More recently the black triangle has been adopted as a symbol in lesbian culture and by disabled activists.

Black shirts were also worn by the British Union of Fascists before World War II, and members of fascist movements in the Netherlands.[69]

Patriotic resistance. The Lützow Free Corps, composed of volunteer German students and academics fighting against Napoleon in 1813, could not afford to make special uniforms and therefore adopted black, as the only color that could be used to dye their civilian clothing without the original color showing. In 1815 the students began to carry a red, black and gold flag, which they believed (incorrectly) had been the colors of the Holy Roman Empire (the imperial flag had actually been gold and black). In 1848, this banner became the flag of the German confederation. In 1866, Prussia unified Germany under its rule, and imposed the red, white and black of its own flag, which remained the colors of the German flag until the end of the Second World War. In 1949 the Federal Republic of Germany returned to the original flag and colors of the students and professors of 1815, which is the flag of Germany today.[70]

A flag used by the anarchist Black Army during the Russian Civil War. It says, "Power begets parasites. Long live Anarchy!"

Benito Mussolini and his blackshirt followers during his March on Rome in 1922.

Black uniform of Heinrich Himmler, head of the SS, the military wing of the Nazi Party (1938).

Military

Black has been a traditional color of cavalry and armoured or mechanized troops. German armoured troops (Panzerwaffe) traditionally wore black uniforms, and even in others, a black beret is common. In Finland, black is the symbolic color for both armoured troops and combat engineers, and military units of these specialities have black flags and unit insignia.

The black beret and the color black is also a symbol of special forces in many countries. Soviet and Russian OMON special police and Russian naval infantry wear a black beret. A black beret is also worn by military police in the Canadian, Czech, Croatian, Portuguese, Spanish and Serbian armies.

The silver-on-black skull and crossbones symbol or Totenkopf and a black uniform were used by Hussars and Black Brunswickers, the German Panzerwaffe and the Nazi Schutzstaffel, and U.S. 400th Missile Squadron (crossed missiles), and continues in use with the Estonian Kuperjanov Battalion.

Religion

In Christian theology, black was the color of the universe before God created light. In many religious cultures, from Mesoamerica to Oceania to India and Japan, the world was created out of a primordial darkness.[71] In the Bible the light of faith and Christianity is often contrasted with the darkness of ignorance and paganism.

In Christianity, the devil is often called the "prince of darkness". The term was used in John Milton's poem Paradise Lost, published in 1667, referring to Satan, who is viewed as the embodiment of evil. It is an English translation of the Latin phrase princeps tenebrarum, which occurs in the Acts of Pilate, written in the fourth century, in the 11th-century hymn Rhythmus de die mortis by Pietro Damiani,[72] and in a sermon by Bernard of Clairvaux[73] from the 12th century. The phrase also occurs in King Lear by William Shakespeare (c. 1606), Act III, Scene IV, l. 14: 'The prince of darkness is a gentleman."

Priests and pastors of the Roman Catholic, Eastern Orthodox and Protestant churches commonly wear black, as do monks of the Benedictine Order, who consider it the color of humility and penitence.

- In Islam, black, along with green, plays an important symbolic role. It is the color of the Black Standard, the banner that is said to have been carried by the soldiers of Muhammad. It is also used as a symbol in Shi'a Islam (heralding the advent of the Mahdi), and the flag of followers of Islamism and Jihadism.

- In Hinduism, the goddess Kali, goddess of time and change, is portrayed with black or dark blue skin. wearing a necklace adorned with severed heads and hands. Her name means "The black one". She destroys anger and passion according to Hindu mythology and her devotees are supposed to abstain from meat or intoxication.[74][75][76] Kali does not eat meat, but it is the śāstra's injunction that those who are unable to give up meat-eating, they may sacrifice one goat, not cow, one small animal before the goddess Kali, on amāvāsya (new moon) day, night, not day, and they can eat it.

- In Paganism, black represents dignity, force, stability, and protection. The color is often used to banish and release negative energies,[77] or binding. An athame is a ceremonial blade often having a black handle, which is used in some forms of witchcraft.[78]

Sports

- The national rugby union team of New Zealand is called the All Blacks, in reference to their black outfits, and the color is also shared by other New Zealand national teams such as the Black Caps (cricket) and the Kiwis (rugby league).

- Association football (soccer) referees traditionally wear all-black uniforms, however nowadays other uniform colors may also be worn.

- In auto racing, a black flag signals a driver to go into the pits.

- In baseball, "the black" refers to the batter's eye, a blacked out area around the center-field bleachers, painted black to give hitters a decent background for pitched balls.

- A large number of teams have uniforms designed with black colors even when the team does not normally feature that color. Many feel the color sometimes imparts a psychological advantage in its wearers. Black is used by numerous professional and collegiate sports teams

Idioms and expressions

- In general, the Negro race of African origin is called "Black", while the Caucasian race of European origin is called "White".

- In the United States, "Black Friday" (the day after Thanksgiving Day, the fourth Thursday in November) is traditionally the busiest shopping day of the year. Many Americans are on holiday because of Thanksgiving, and many retailers open earlier and close later than normal, and offer special prices. The day's name originated in Philadelphia sometime before 1961, and originally was used to describe the heavy and disruptive downtown pedestrian and vehicle traffic which would occur on that day.[79][80] Later an alternative explanation began to be offered: that "Black Friday" indicates the point in the year that retailers begin to turn a profit, or are "in the black", because of the large volume of sales on that day.[79][81]

- "In the black" means profitable. Accountants originally used black ink in ledgers to indicate profit, and red ink to indicate a loss.

- Black Friday also refers to any particularly disastrous day on financial markets. The first Black Friday (1869), September 24, 1869, was caused by the efforts of two speculators, Jay Gould and James Fisk, to corner the gold market on the New York Gold Exchange.

- A blacklist is a list of undesirable persons or entities (to be placed on the list is to be "blacklisted").

- Black comedy is a form of comedy dealing with morbid and serious topics. The expression is similar to black humor or black humour.

- A black mark against a person relates to something bad they have done.

- A black mood is a bad one (cf Winston Churchill's clinical depression, which he called "my black dog").[82]

- Black market is used to denote the trade of illegal goods, or alternatively the illegal trade of otherwise legal items at considerably higher prices, e.g. to evade rationing.

- Black propaganda is the use of known falsehoods, partial truths, or masquerades in propaganda to confuse an opponent.

- Blackmail is the act of threatening someone to do something that would hurt them in some way, such as by revealing sensitive information about them, in order to force the threatened party to fulfill certain demands. Ordinarily, such a threat is illegal.

- If the black eight-ball, in billiards, is sunk before all others are out of play, the player loses.

- The black sheep of the family is the ne'er-do-well.

- To blackball someone is to block their entry into a club or some such institution. In the traditional English gentlemen's club, members vote on the admission of a candidate by secretly placing a white or black ball in a hat. If upon the completion of voting, there was even one black ball amongst the white, the candidate would be denied membership, and he would never know who had "blackballed" him.

- Black tea in the Western culture is known as "crimson tea" in Chinese and culturally influenced languages (紅 茶, Mandarin Chinese hóngchá; Japanese kōcha; Korean hongcha).

- "The black" is a wildfire suppression term referring to a burned area on a wildfire capable of acting as a safety zone.

- Black coffee refers to coffee without sugar or cream.

Associations and symbolism

Mourning

In the West, black is commonly associated with mourning and bereavement,[83][6] and usually worn at funerals and memorial services. In some traditional societies, for example in Greece and Italy, some widows wear black for the rest of their lives. In contrast, across much of Africa and parts of Asia like Vietnam, white is a color of mourning.

In Victorian England, the colors and fabrics of mourning were specified in an unofficial dress code: "non-reflective black paramatta and crape for the first year of deepest mourning, followed by nine months of dullish black silk, heavily trimmed with crape, and then three months when crape was discarded. Paramatta was a fabric of combined silk and wool or cotton; crape was a harsh black silk fabric with a crimped appearance produced by heat. Widows were allowed to change into the colors of half-mourning, such as gray and lavender, black and white, for the final six months."[84]

A "black day" (or week or month) usually refers to tragic date. The Romans marked fasti days with white stones and nefasti days with black. The term is often used to remember massacres. Black months include the Black September in Jordan, when large numbers of Palestinians were killed, and Black July in Sri Lanka, the killing of members of the Tamil population by the Sinhalese government.

In the financial world, the term often refers to a dramatic drop in the stock market. For example, the Wall Street Crash of 1929, the stock market crash on October 29, 1929, which marked the start of the Great Depression, is nicknamed Black Tuesday, and was preceded by Black Thursday, a downturn on October 24 the previous week.

The dowager Electress of Palatine in mourning (1717)

Emperor Pedro II of Brazil and his sisters wearing mourning clothes due to their father's death (1834)

Queen Victoria wore black in mourning for her husband Prince Albert (1899)

Darkness and evil

In western popular culture, black has long been associated with evil and darkness. It is the traditional color of witchcraft and black magic.[6]

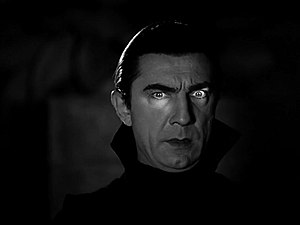

In the Book of Revelation, the last book in the New Testament of the Bible, the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse are supposed to announce the Apocalypse before the Last Judgment. The horseman representing famine rides a black horse.[85] The vampire of literature and films, such as Count Dracula of the Bram Stoker novel, dressed in black, and could only move at night. The Wicked Witch of the West in the 1939 film The Wizard of Oz became the archetype of witches for generations of children. Whereas witches and sorcerers inspired real fear in the 17th century, in the 21st century children and adults dressed as witches for Halloween parties and parades.

The biblical Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, including famine riding a black horse (painting by Viktor Vasnetsov, 1887)

Count Dracula as portrayed by Bela Lugosi in the 1931 film version

Power, authority and solemnity

Black is frequently used as a color of power, law and authority. In many countries judges and magistrates wear black robes. That custom began in Europe in the 13th and 14th centuries. Jurists, magistrates and certain other court officials in France began to wear long black robes during the reign of Philip IV of France (1285–1314), and in England from the time of Edward I (1271–1307). The custom spread to the cities of Italy at about the same time, between 1300 and 1320. The robes of judges resembled those worn by the clergy, and represented the law and authority of the King, while those of the clergy represented the law of God and authority of the church.[86]

Until the 20th century most police uniforms were black, until they were largely replaced by a less menacing blue in France, the U.S. and other countries. In the United States, police cars are frequently Black and white. The riot control units of the Basque Autonomous Police in Spain are known as beltzak ("blacks") after their uniform.

Black today is the most common color for limousines and the official cars of government officials.

Black formal attire is still worn at many solemn occasions or ceremonies, from graduations to formal balls. Graduation gowns are copied from the gowns worn by university professors in the Middle Ages, which in turn were copied from the robes worn by judges and priests, who often taught at the early universities. The mortarboard hat worn by graduates is adapted from a square cap called a biretta worn by Medieval professors and clerics.

The United States Supreme Court (2009)

Judges at the International Court of Justice in the Hague

A Black and white police car of the Los Angeles Police Department

Functionality

In the 19th and 20th centuries, many machines and devices, large and small, were painted black, to stress their functionality. These included telephones, sewing machines, steamships, railroad locomotives, and automobiles. The Ford Model T, the first mass-produced car, was available only in black from 1914 to 1926. Of means of transportation, only airplanes were rarely ever painted black.[87]

A 1920 Ford Model T

The first model BlackBerry (2000)

Black house paint is becoming more popular with Sherwin-Williams reporting that the color, Tricorn Black, was the 6th most popular exterior house paint color in Canada and the 12th most popular paint in the United States in 2018.[88]

Ethnography

- The term "black" is often used in the West to describe people whose skin is darker. In the United States, it is particularly used to describe African Americans. The terms for African Americans have changed over the years, as shown by the categories in the United States Census, taken every ten years.

- In the first U.S. Census, taken in 1790, just four categories were used: Free White males, Free White females, other free persons, and slaves.

- In the 1820 census the new category "colored" was added.

- In the 1850 census, slaves were listed by owner, and a B indicated black, while an M indicated "mulatto".

- In the 1890 census, the categories for race were white, black, mulatto, quadroon (a person one-quarter black); octoroon (a person one-eighth black), Chinese, Japanese, or American Indian.