Early Gothic architecture

Top: Saint-Denis:Bottom: Wells Cathedral | |

| Years active | Mid-12th to mid 13th century |

|---|---|

| Country | France and England |

Early Gothic is a term for the first phase of Gothic style, followed by High Gothic and Late Gothic, dividing the whole Gothic era into three periods. It is defined as a style that used some principle elements of Gothic, but not all. Especially, it had no fine tracery. It marks the first phase of a division of Gothic Style into three periods. If it is used for all countries, it has to be regarded that there may be special terms for the styles of single countries, such as Early English in England.

In France, where Gothic style had been initiated, another phasing has been established:

- Gothique primitif (Primary Gothic) or Gothique premier (First Gothic), from short before 1140 until short after 1180, marked by tribunes above the aisles of basilicas.[1][2]

- Gothique classique (Classic Gothic), from the 1180s to the first third of 13th century, marked by basilicas without lateral tribunes and with triforia without windows. Some buildings of this phase, like Chartres Cathedral, have to be subsumed to Early Gothic, others, like the Reims Cathedral and the western parts of Amiens Cathedral, have to be subsumed to High Gothic.

- Gothique rayonnant (Radiant or Shining Gothic), from the second third of 13th century to the first half of 14th century, marked by triforia with windows and a general preference for stained glass instead of stone walls. It forms the greater portion of High Gothic.

- Gothique flamboyant (Flaming Gothic), since mid 14th century, marked by swinging and flaming (that makes the term) forms of tracery.

The term "Early Gothic" should not be extended backward; if Durham Cathedral and other buildings with the first rib vaults in Romanesque walls are subsumed to this style, most of German Late Romanesque architecture would be Early Gothic.

Primary Gothic appeared in northern France in the 130s. In Normandy, it was mixed with regional traditions. In England, it gave the example for Early English architecture. It combined and developed several key elements from earlier styles, particularly from Romanesque architecture, including the rib vault, flying buttress, and the pointed arch, and used them in innovative ways to create structures, particularly Gothic cathedrals and churches, of exceptional height and grandeur, filled with light from stained glass windows. Notable examples of early Gothic architecture in France include the ambulatory and facade of Saint-Denis Basilica; Sens Cathedral (1140); Laon Cathedral; Senlis Cathedral; (1160) and most famously Notre-Dame de Paris (begun 1160).[3]

Early English Gothic was influenced by the French style, particularly in the new choir of Canterbury Cathedral, but soon developed its own particular characteristics, particularly an emphasis for length over height, and more complex and asymmetric floor plans, square rather than rounded east ends, and polychrome decoration, using Purbeck marble. Major examples are the nave and west front of Wells Cathedral, the choir of Lincoln Cathedral, and the early portions of Salisbury Cathedral.[4]

Early Gothic was succeeded in the early 13th century by a new wave of larger and taller buildings, with further technical innovations, in a style later known as High Gothic.[5]

Origins

French Gothic architecture was the result of the emergence in the 12th century of a powerful French state centered in the Île-de-France. King Louis VI of France (1081–1137), had succeeded, after a long struggle, in bringing the barons of northern France under his control, and successfully defended his domain against attacks by the English King, Henry I of England (1100–1135). Under Louis and his successors, cathedrals were the most visible symbol of the unity of the French church and state. During the reign of Louis VI of France (1081–1137), Paris was the principal residence of the Kings of France, the Carolingian era Reims Cathedral the place of coronation, and the Abbey of Saint-Denis became the ceremonial burial place. The King and his successors lavishly supported the construction and enlargement of abbeys and cathedrals.

The Abbot of Saint-Denis, Suger, was not only a prominent religious figure but also first minister to Louis VI and Louis VII. He oversaw the royal administration when the King was absent on the Crusades. He commissioned the reconstruction of the Basilica of Saint-Denis, making it the first and most influential example of the new style in France.[6]

Basilica of Saint-Denis

The Basilica of Saint-Denis was important because it was the burial place of the French Kings of the Capetian dynasty from the late 10th until the early 14th century. It attracted a very large number of pilgrims, attracted by the relics of Saint Denis, the patron saint of Paris. To accommodate the large number of pilgrims, Suger first constructed a new narthex and facade at the west end, with twin towers and a rose window in the center.

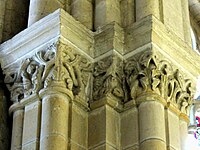

The most original and influential step made by Suger was the creation of the chevet, or east end, with radiating chapels. Here he used the pointed arch and rib vault in a new way, replacing the thick dividing walls with arched rib vaults poised on columns with sculpted capitals. Suger wrote that the new chevet was "ennobled by the beauty of length and width." And "the midst of the edifice was suddenly raised aloft by twelve columns". He added that, when creating this feature, he was inspired by the ancient Roman columns he had seen in the ruins of the Baths of Diocletian and elsewhere in Rome.[7] He described the finished work as "a circular string of chapels, by virtue of which the whole church would shine with the wonderful and uninterrupted light of most luminous windows, pervading the interior beauty."[8]

Suger was an admirer of the doctrines of the early Christian philosopher John Scotus Eriugena (c. 810–87) and Dionysus, or the Pseudo-Areopagite, who taught that light was a divine manifestation, and that all things were "material lights", reflecting the infinite light of God himself.[8] Therefore, stained glass became a way to create a glowing, unworldly light ideal for religious reflection.[3]

According to Suger, every aspect of the new apse architecture had a symbolic meaning. The twelve columns separating the chapels, he wrote, represented the twelve Apostles, while the twelve columns of the side aisles represented the minor prophets of the Old Testament.[7]

The Basilica, including the upper parts of the choir and the apse, were extensively modified into the Rayonnant style in the 1230s, but the original early Gothic ambulatory and chapels can still be seen.[9]

Basilica of Saint Denis, west facade (1135–40)

Early French Gothic cathedrals

Sens Cathedral

The construction of the choir and ambulatory of Sens Cathedral began before the construction of the amblatory of Saint-Denis. Therefore, the ambulatory is rather Romanesque than Gothic. All adjacent chapels are much later and no more Primary Gothic. But its arcades and triforia already fit the criteria of Gothic architecture.[8] It was constructed between 1135 and 1164. Different from the other cathedrals of Primary Gothic, it has no tribunes above the aisles, but triforia as one of three levels, alike some Romanesque basilicas before and Classic Gothic afterwards. It used the new six-part rib vault in the nave, giving the church exceptional width and height. Because the six-part vaults distributed the weight unevenly, the vaults were supported by alternating massive square piers and more slender round columns.[10][11][12] It had a wide impact on the Gothic style not only in France, but also in England, because its master builder, William of Sens, was invited to England and introduced Early Gothic features to the reconstructed nave of Canterbury Cathedral.

In the following centuries, all clerestories were remodeled, and the transept is Flamboyant.

Facade of Sens Cathedral (1135–64)

Senlis Cathedral

Senlis Cathedral was built between 1153 and 1191. Its length was limited by modest budget and by the placement of the building against the city wall. Like Sens cathedral, it was composed of a nave without a transept, flanked by a single collateral. The radiating chapels of the choir are separate extensions of the ambulatory (different from Saint-Denis, whree thy form something like an outer aisle). They gave an example for Magdeburg Cathedral that was begun in 1209 and has polygonal ambulatory and chapels. The elevation of Senlis originally had four levels, including large tribunes. Like Sens, Senlis Cathedral had alternating strong and weak piers to receive the uneven thrust from the six-part rib vaults. The church underwent considerable rebuilding in the 13th and 16th century, including a new tower and new interior decorations. Many of the early Gothic features are overladen with Flamboyant and later decoration.[13] In the 16th century, the triforia disappeared, whereas the tribunes kept their Primary Gothic layout until today.

Buttresses of Primary Gothic, Flamboyant clerestory of C XVI

Noyon Cathedral

Noyon Cathedral, begun between 1150 and 1155, was the first of a series of famous Cathedrals to appear in Picardy, the prosperous region north of Paris. The city an important connection with French history, as the coronation site of Charlamagne and of the early French King Hugh Capet. The new cathedral still had many Romanesque features, including prominent transepts with rounded ends and deep galleries, but it introduced several Gothic innovations, including the fourth level, the triforium a narrow passageway between the ground-level gallery, the tribunes, and the top level clerestory, Noyon also used massive compound piers alternating with round columns, necessary because of the uneven weight distribution from the six-part vaults.[8] The east end has five radiating chapels and three levels of windows, creating a created a dramatic flood of light into the nave.[14]

- Noyon Cathedral

Façade, 1200–1235, Classic Gothic

Laon Cathedral

Laon Cathedral was begun in 1155, in Primary Gothic style. until about 1180, the (first) choir, crossing and transept and the eastern five bays of the nave were finished. The western part of the nave and the façade followed until 1200. Therefore, the façade is already an example of Classic Gothic; Villard de Honnecourt praised the innovative upper parts of the towers. But the original choir began to decay and in 1205–1220 was replaced by the actual one. Following English examples, it has no apse, but a rectangular east end.

Laon was built upon a hilltop one hundred meters high, making it visible from a great distance. The hilltop imposed a special burden for the builders; all the stones had to be carried to the top of the hill in carts drawn by oxen. The oxen who did the work were honored by statues on the tower of the finished cathedral.[13]

Laon was also unusual because of its five towers; two on the west front, two on the transepts, and an octagonal lantern on crossing. Laon, like most early Gothic cathedrals, had four interior levels. Laon also had alternating octagonal and square piers supporting the nave, but these rested upon massive pillars made of dreamlike sections of stone, giving it greater harmony and a greater sensation of length.[15] The new cathedral was unusual in form; The apse on the east was flat, not rounded, and The choir was exceptionally long, nearly as long as the nave.[16] Another striking feature of Laon Cathedral were the three great rose windows, one on the west facade and two on the transepts. (Only the west and north windows still remain). Another unusual feature at Laon is lantern tower at the transept crossing, most likely inspired by the Norman Gothic abbey churches in Caen.[13]

Laon Cathedral gave the example for the first Gothic project in Germany, the Gothic remodeling of Limburg Cathedral, begun in the 1180s.[17][18]

- Laon Cathedral

Notre Dame de Paris

Notre Dame de Paris was the largest of the Early Gothic cathedrals, and marked the summit of the Early Gothic in France. It was begun in 1163 by the Bishop Maurice de Sully with the intention of surpassing all other existing churches in Europe. The new cathedral was 122 meters long and 35 meters high, eleven meters higher than Laon Cathedral, the previous tallest church. It featured a central nave flanked by double collaterals, and a choir surrounded by a double ambulatory, without radiating chapels. (The current chapels were added between the buttresses in the 14th century).[19]

The builders covered the interior of the cathedral with six-part vaults, but unlike Sens and other the earlier cathedrals they did not use alternating piers and columns to support them. The vaults were supported instead by bundles of three uninterrupted slender columns which were received by rows massive pillars with capitals decorated with classical decoration. This gave the nave greater harmony.

The upper parts of the choir wer built at about 1882 or 1885, not long before Chartres Cathedral. Its original elevations were intermediate between tree levels and four levels: above the tribunes there were no veritable triforia, but a clerestory with two levels of windows, the lower level consisted of small rose windows, and the upper level of modest ointed arched windows without tracery.

In the 13th century, when it was decided that the interior was too dark, and the upright windows were enlarged downward into the area of the small roses. Around the transept, the original design was reconstructed during the restoration by Viollet-le-Duc.[19]

The flying buttress made its first appearance in Paris in the early 13th century, either at Notre Dame, or perhaps earlier in the Abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Pres. The buttresses, in the form of half-arches, reached from the heavy buttresses outside the nave, over the top of the tribunes, and pressed directly against the upper walls of the nave, countering the outward thrust from the vaults. This made possible the installation of larger windows in the upper walls of the nave the buttresses.[19]

- Notre Dame de Paris

The flying buttresses of Notre Dame as they appeared in about 1220–30 (drawn by Eugène Viollet-le-Duc)

Chartres Cathedral (1194–1225)

Chartres Cathedral was the site of four annual trade fairs on the Feast Days of the Virgin Mary and a popular pilgrimage site which displayed the reputed tunic that Mary wore when giving birth to Christ.[20] A series of earlier cathedrals in Chartres beginning in the fourth century, were destroyed by fire. The cathedral immediately previous to the present church burned in 1194, leaving only the crypt, towers, and the recently built west front. Rebuilding began the same year, with support from the Pope, the King, and the wealthy nobility and merchants of the city.

Concerning its windows (without tracery or with plate tracery), this cathedral was still an example of Early Gothic, but its elevations were innovative. Therefore Chartres Cathedral is considered the initial building of Classic Gothic. The arcades and aisles were much taller than in the first Gothic cathedrals, and the tribune were omitted. Also the clerestories were higher than in any basilica before it. Exept of their lowest parts, the apse and the chapels were polygonal.

Work was nearly completed by 1225, with the architecture, glass and sculpture finished, though the seven steeples were still being rebuilt. It was not formally reconsecrated until 1260. Only a few changes were made since that time, including the addition of a new chapel dedicated to Saint Piat in 1326, and the covering of the choir columns with stucco and the addition marble reliefs in behind the stalls in the 1750s.[21]

The new cathedral was 130.2 meters long and 30 meters high in the nave longer and higher than Notre-Dame de Paris.[22] Since the cathedral was constructed with the new flying buttresses, the walls were more stable, enabling the builders to eliminate the tribune level, and have more space for windows.[22]

The lower portions of the west front (1134–1150) are Early Gothic. The fronts of the north and south transepts are High Gothic, as is the sculpture of the six thirteenth-century portals. The spire on the north tower is later Flamboyant.[20] Chartres still has much of its original medieval stained glass, famous for the deep color called Chartres blue.[20]

- Chartres Cathedral

South side of the nave: No fine tracery, except of the Flamboyant window on the very right

Bourges Cathedral (1195–1230)

While most High Gothic cathedrals generally followed the Chartres plan, Bourges Cathedral took a different direction. It was built by Bishop Henri de Sully, whose brother, Eudes de Sully, was the bishop of Paris, and its construction in several ways followed Notre-Dame de Paris and not Chartres. Like Chartres, the builders simplified the vertical plan to three levels; grand arcades, triforium, and high windows. The triforium was simplified a long horizontal band, the entire length of the church. However, unlike Paris, Bourges continued to use the older six-part rib vault used in Paris. This meant that the weight of the vaults fell unevenly upon the nave, and required, like Early Gothic cathedrals, alternating strong and weak pillars. This was artfully hidden by the use of large cylindrical piers, each surrounded by eight engaged colonettes. The piers of the arcade are particularly imposing; each is 21 m (69 ft) tall.[23] Choir and chapels of Bourges cathedral still have semicircular ends.

Since Bourges used six-part rib vaults instead of the lighter four-part vaults, the upper walls had to resist greater outward thrust, and the flying buttresses had to be more effective. The Bourges buttresses used a unique design with a particularly acute angle, which gave it the necessary force, but it was also reinforced by thicker and stronger walls than Chartres.[23]

The predominant sensation at Bourges is not only great height, but great length and interior space; the cathedral is 120 m (390 ft) long, without a transept or other interruption.[24] The most unusual feature of Bourges Cathedral is the arrangement of vertical height; each part of the elevation is set back, like steps, with the highest roof and vaults over the central aisle. The outermost aisles have vaults nine meters high; the intermediate aisles have vaults 21.3 m (70 ft) high; and the center aisle has vaults 37.5 m (123 ft) high.[23]

Many later Gothic cathedrals followed the Chartres model, but several were influenced by Bourges, including Le Mans Cathedral, the modified Beauvais Cathedral, and Toledo Cathedral in Spain, which copied the system of vaults of different heights.[23]

- Bourges Cathedral

Angevin Gothic

Most buildings of Plantagenet style, also called Angevin Gothic, by dating and by shape are part of early Gothic. In the reconstruction of Angers Cathedral begun by bishop Normand de Doué, 1148–1152, the first Angevin vault were constructed. Poitiers Cathedral, erected since 1166 is known as the first Gothic hall church. Its eastern parts are Early Gothic with som Romanesque elements, ist western Parts have High Gothic trecery.

Early Classic Gothic

Some crucial examples of Classic Gothic, such as Chartres Cathedral (see above) and Bourges Cathedral fit the criteria of Early Gothic.

Early Gothic in Normandy

Experiments with Gothic features were also underway in Normandy in the late 11th and 12th centuries. In 1098 Lessay Abbey was given an early version of the pointed rib vault in the choir.[25] The church of Saint-Pierre de Lisieux, begun in the 1170s, featured the more modern four-part rib vaults and flying buttresses. Other experiments with Gothic rib vaults and other features took place in Caen, in the churches of the two large royal abbeys churches, the Abbey of Saint-Étienne, Caen and the Abbey of Sainte-Trinité, Caen, but they remained essentially Norman Romanesque churches.[26]

Rouen Cathedral had notable early Gothic features, added when the interior was reconstructed from Romanesque to Gothic by archbishop Gautier de Coutances beginning in 1185. The new Gothic nave was given four levels, while the later choir had the newly fashionable three.[26]

Early Gothic in England

Canterbury Cathedral

One of the first major buildings in England to use the new style was Canterbury Cathedral. A fire destroyed the mainly Romanesque choir in September 1174, and leading architects from England and France were invited to offer plans for its reconstruction. The winner of this competition was a French master builder, William of Sens, who had been involved in the construction of Sens Cathedral, the first complete Gothic cathedral in France. [27]

Many limitations were put upon William of Sens by the monks who ran the cathedral. He was not allowed to replace entirely the original Norman church, and had to fit his new structure on the old crypt and within the surviving outer Norman walls. Nonetheless, he achieved a strikingly original sculpture, showing elements inspired by Notre-Dame de Paris and Laon Cathedral. Following the French model, he used six-part rib vaults, pointed arches, supporting columns with carved acanthus leaf decoration, and a semi-circular ambulatory. However, other elements were purely English, such as the use of dark Purbeck marble to create decorative contrasts with the pale stone brought from Normandy. The work was described by a monk and chronicler, Gervase of Canterbury. Contrasting the old with the new choir. He wrote: "There, the arches and everything else was plain, or sculpted with an axe and not with a chisel. But here almost throughout is appropriate sculpture. There used to be no marble shafts, but here are innumerable ones. There in the circuit round the choir, the vaults were plain, but here they are arch-ribbed and have key-stones." [28]

William of Sens fell from a scaffolding in 1178 and was seriously injured, and returned to France, where he died,[29] and his work was continued by an English architect, William the Englishman, who constructed the Trinity Chapel in the apse and the Corona in the east end, which were monuments to Thomas Becket, who had been murdered in the cathedral. The new structure had many French features, such as the doubled columns in the Trinity chapel, and piers replaced by Purbeck-marble wall shafts. But it also retained many specifically English features, such as a great variety in the level and placement of the spaces; the Trinity chapel, for example is sixteen steps above the Choir). It also retaining rather than eliminated the transepts - Canterbury had two. Early English Gothic put an emphasis on great length; Canterbury was doubled in length between 1096 and 1130.[28]

One reason for the differences between French and English Gothic was that French Benedictine abbey-churches usually put different functions into separate buildings, while in England they were usually combined in the same structure. Similar complicated multifunctional designs were found not only in Canterbury, but in the abbey-churches of Bath, Coventry, Durham, Ely, Norwich, Rochester, Winchester and Worcester.[30]

Choir of Canterbury Cathedral rebuilt by William of Sens (1174–1184)

The Cistercian abbeys

Another notable form of early English Gothic architecture was that of the Cistercian monasteries. The Cistercian order had been formed in 1098 as a reaction against the opulence and ornament of the Benedictine order and its monasteries. The architecture of the Cistercians was based upon simplicity and functionality. All decoration was forbidden. The Cistercian monasteries were in remote locations, far from the cities. They were closed in 1539 during the reign of Henry VIII, and now are picturesque ruins. Examples include Kirkstall Abbey (c. 1152); Roche Abbey (c. 1172), and Fountains Abbey (c. 1132) all in Yorkshire.

Kirkstall Abbey (c. 1152)

Roche Abbey (c. 1172)

Fountains Abbey (c. 1132)

Wells Cathedral

Wells Cathedral, (built between 1185–1200 and modified until 1240) is another leading example of the early English style. It borrowed some aspects, such as its elevation, from the French style, but gave precedence to strong horizontals, such as the triforium, rather than the dominant vertical elements, such as wall shafts, of the French style. The piers were composed of as many as twenty-four shafts, adding another unusual decorative effect.[31] The north porch, built in 1210–15, and especially the west front (1220–1240) had a particularly novel decorative effect. The screen facade of the west front is filled with nearly four hundred carved and painted stone figure, and is made more impressive by two flanking towers, attached to but not part of the body of the church. This arrangement was adapted by other English cathedrals, including Salisbury Cathedral and Exeter Cathedral.[31]

West front of Wells Cathedral (1220–1240)

Nave of Wells Cathedral, with its strong horizontal emphasis. The unusual double arch was added in 1338 to reinforce the support of the tower.

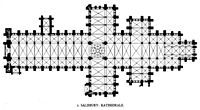

Salisbury Cathedral

Salisbury Cathedral (1220–1260) is another example of the mature Early English Gothic. Salisbury is best known for its famous crossing tower and spire, added in the 14th century, but its complex plan, with two sets of transepts, a projecting north porch and a rectangular east end, is a classic example of the early English Gothic.[32] It was a distinct contrast from the French Amiens Cathedral, begun the same year, with its simple apse on east and its minimal transepts. The nave has strong horizontal lines created by the contrast of the dark Purbeck marble columns. The Lady Chapel of Salisbury has extremely slender pillars of Purbeck marble supporting the vaults, shows the diversity and harmony of mature English Early Gothic, entering the period of Decorated Gothic.[32]

The sprawling plan of Salisbury Cathedral (1220–1260), with its multiple transepts and projecting porch

The nave of Salisbury Cathedral, with its strong horizontal lines of dark Purbeck marble columns

Lincoln Cathedral

Lincoln Cathedral (rebuilt from the Norman style beginning in 1192), is the best example of the fully mature early Gothic style.[4] The master-builder, Geoffrey de Noiers, was French, but he constructed a church with distinct non-French features; double transepts, an elongated nave, complexity of interior space, and a more lavish use of decorative features.[31] St. Hugh's Choir, named after the French-born monk St. Hugh of Lincoln, was a good example. The choir was covered with a rib vault in which most of the ribs had a purely decorative role. In addition to the functional ribs, it featured extra ribs called tiercerons, which did not lead to the central point of the vault, but to a point along the ridge rib on the crown of the vault. They were put together in lavish designs, which gave the resulting ceiling the nickname "The crazy vault."[31]

Another distinctive English element introduced at Lincoln was the use of s the blind arcade (also known as a blank arcade) in the decoration of Hugh's chapel. Two layers of arcades with pointed arches are attached to the walls, giving a theatrical effect of three dimensions. This element is enhanced by the use of different color stone for the thin columns; ribs of white limestone for the lower columns and black Purbeck marble for the upper portions.[31]

A third feature important feature of Lincoln was the thick or double-shell wall. This was an Anglo-Romanesque feature, which earlier had been in used in Romanesque structures of Caen, and in Durham and Winchester Cathedral. Instead of being supported only by flying buttresses, the vaults receive additional support from the thicker walls of the gallery over the aisles. This allowed a considerably wider span across the nave, and also meant that the vaults could have additional purely decorative ribs, as in the "Crazy vault".[33]

Lincoln Cathedral (rebuilt beginning in 1192)

The wide nave of Lincoln Cathedral

The "Crazy Vaults" of the St. Hugh's choir of Lincoln Cathedral

Characteristics

Plans

The plans of the early Gothic cathedrals in France were usually in the form of a Greek cross, and were relatively simple. Sens Cathedral, the first in France, was a good example; A facade with three portals and two towers; a long nave with collateral aisles; a rather long choir, a very short transept, and a rounded apse with a double ambulatory and radiating chapels. Variations on this plan were used in most early French cathedrals, including Noyon Cathedral and Notre Dame de Paris.[34]

Choir and ambulatory of Saint-Denis abbey church, 1140

Plan of Sens Cathedral begun in 1135

Noyon Cathedral, 1130–1150, plan without later additions

Notre Dame de Paris, begun in 1163, plan with additions since 1220.

Choir and ambulatory of Notre Dame de Paris before 1220, reconstruction by Violet-le-Duc

The plans of the early English Gothic cathedrals were usually longer and much more complex, with additional transepts, attached chapels, external towers, and usually a rectangular west end. The choirs were often as long as the nave. The form expressed the multiple activities often going on simultaneously in the same building.[35]

Plan of Wells Cathedral (begun 1175)

Plan of Lincoln Cathedral (begun 1192)

Salisbury Cathedral (begun 1220)

Elevations

At the time of the early Gothic, the flying buttress was not yet in common use, and buttresses were placed directly close to or directly against the walls. The walls had to be reinforced by additional width.[36] The early Gothic churches in France typically had four elevations or levels in the nave: the aisle arcade on the ground floor; the gallery arcade, a passageway, above it; the blind triforium, a narrower passageway, and the clerestory, a wall with larger windows, just under the vaults. These multiple levels added to the width and thus the stability of the walls, before the flying buttress was commonly used. This was the system used at Sens Cathedral, Noyon Cathedral and originally at Notre Dame de Paris.[36]

The introduction of a simpler four-part rib vault and especially the flying buttress meant that the walls could be thinner and higher, with more room for windows. By the end of the period, the triforium level was usually eliminated, and larger windows filled the space.[36]

Noyon Cathedral, late 12h century, four levels: arcade, tribune, triforium, clerestory

Choir of Notre Dame de Paris, consecration 1182, three levels (arcade, tribune and clerestory); triforia removed by the remodeling of the clerestories after 1220

Three-part elevation of Wells Cathedral (begun 1176)

Nave of Lincoln Cathedral. showing three levels; arcades (bottom); tribunes {middle} and clerestory (top).

Vaults

The rib vault was a characteristic feature of Gothic architecture from the beginning. It was the result of a search for a way to build stone roofs on churches that could not catch fire but would not be too heavy. Variations of rib vaults had been used in Islamic and Romanesque architecture, often to support domes.[37] The rib vault had thin stone ribs which carried the vaulted surface of thin panels.[9] Unlike the earlier barrel vault, where the weight of the vault pressed down directly onto the walls, the arched ribs of a rib vault had a pointed arch, a rib which directed the weight outwards and downwards to specific points, usually piers and columns in the nave below, or outward to the walls, where it was countered by buttresses. The panels between the ribs were made of small pieces of stone, and were much lighter than the earlier barrel vaults. A primitive form, a ribbed groin vault, with round arches, was used at Durham Cathedral, and then, in the course of building, was improved with pointed arches in about 1096. Other variations had been used at Lessay Abbey in Normandy at about the same time.[35]

The first Gothic rib vaults were divided by the ribs into six compartments. A six-part vault could cover two sections of the nave. Two pointed arches crossed diagonally and were supported by an intermediate arch, which crossed the nave from side to side. The weight was carried downward by thin columns from the corners of the vault to the alternating heavy piers and thinner columns in the nave below. The weight was distributed unevenly; the piers received the greater weight from diagonal arches, while the columns took the lesser weight from the intermediate arch. This system was used successfully at the Basilica of Saint-Denis, Noyon Cathedral, Laon Cathedral, and Notre-Dame de Paris.

A simpler and stronger vault with just four compartments was developed at the end of the period by eliminating the intermediate arch. As a result, the piers or columns below all received an equal load, and could have the same size and appearance, giving greater harmony to the nave. This system was used increasingly at the end of the Early Gothic period.

More elaborate rib vaults were introduced in England later in the period, at Lincoln Cathedral. These had additional purely decorative ribs called the lierne and the tierceron, in ornate designs like stars and fans, They were the work of Geoffrey de Noiers, a French or French-Normand master-builder who between 1192 and 1200 designed St. Hugh's choir, completed in 1208. The ribs were designed so that the bays slightly offset each other, giving them the nickname of "Crazy vaults".[38] De Noiers was succeeded at Lincoln by Alexander the Mason, who designed the tierceron star vaulting in the cathedral's nave.[39] at Lincoln Cathedral.[40]

Six-part vaults in Sens Cathedral (begun 1135)

Six-part rib vaults in Notre-Dame de Paris (begun 1163)

Four-part vaults of Wells Cathedral (begun 1176)

"Crazy vaults" of Lincoln Cathedral in St. Hugh's choir (1192–1208)

Flying buttress

Variations of the flying buttress existed before the Gothic period, but Gothic architects developed them to a high degree of sophistication. By counterbalancing the thrust against the upper walls from the rib vaults, they made possible the great height, thin walls and large upper windows of the Gothic cathedrals. The early Gothic buttresses were placed close to the walls, and were columns of stone with a short arch to the upper level, between the windows. They were often topped by stone pinnacles both for decoration, and to make them even heavier.

Flying buttress at the Abbey of Saint-Étienne, Caen, Caen (11th century)

Early buttresses of Noyon Cathedral

Buttresses of Laon Cathedral

Flying buttresses of Salisbury Cathedral

Sculpture

The most important sculptural decoration of early Gothic cathedrals was found over and around the portals, or doorways, on the tympanum and sometimes also on the columns. Following the model of Romanesque churches, these depicted the Holy Family and Saints. Following the tradition of Romanesque sculpture, the figures were usually stiff, straight, simple forms, and often elongated. As the period advanced, the sculpture became more naturalistic. The floral and vegetal sculpture of the capitals of columns in the nave was more realistic, showing a close observation of nature.[4]

One of the finest examples of early Gothic sculpture is the tympanum over the royal portal of Chartres Cathedral (1145–1245), which survived a fire that destroyed much of the early Cathedral.

Central tympanum of the royal portal, Chartres Cathedral (1145–1245)

Adam and Eve eating apples, west front of Lincoln Cathedral (12th century)

Stained glass

Stained glass had existed for centuries, and was used in Romanesque churches, but it became was a particularly important feature of early Gothic architecture. The Abbot Suger commissioned stained glass windows for the Basilica of Saint-Denis to fill the ambulatory and chapels with what he considered to be divine light. The stained glass windows of Saint-Denis and other Early Gothic churches had a particular intensity of color, partly because the glass was thicker and used more color, and partly because the early windows were small, and their light had a more striking contrast with the dark interiors of the churches and cathedrals.

The process of making the windows was described by the monk Theophilus Presbyter in the early 12th century. The glass and the windows were made by different craftsmen, usually at different locations. The molten glass was coloured with metal oxides; cobalt for blue, copper for red, iron for green, manganese for purple and antimony for yellow. When molten, it was blown into a bubble, formed into a tubular shape, cut at the ends to make a cylinder, then slit and flattened while it was still hot. It ranged in thickness from 3 to 8 mm (0.12 to 0.31 in). A full-size drawing of the window was made on a large table, and then pieces of colored glass were "grozed", or cracked off the sheet, and assembled on the table. The details of the windows were then painted on in vitreous enamel, then fired. The glass pieces were fit into grooved pieces of lead, which were soldered together, and sealed with putty to make them waterproof, to complete the window.[41][42]

The rose window was a particular feature of early Gothic. They had been used in Romanesque architecture, such as the two small windows on the facade of Pomposa Abbey in Italy (early 10th century), but they became more important and complex in the Gothic period. In the 12th century, according to Bernard of Clairvaux, writing at that time, the rose was the symbol of the Virgin Mary, and had a prominent place on the facades of the cathedrals named for her, such as Notre-Dame de Paris, whose west rose window dates from 1220.[43]

The rose windows of the Early Gothic churches were composed of plate tracery, a geometric pattern of openings in stone over the central portal. Early examples included the rose on the west facade of the Basilica of Saint-Denis (though the present window is not original), and the early rose window on the west front of Chartres Cathedral. Other examples are the rose on the west front of Laon Cathedral and Notre Dame de Mantes (1210) [43] York Minster has what is believed to be the oldest existing stained glass window in England, a Tree of Jesse (1170).

12th century stained glass from Basilica of Saint-Denis

Detail of a Tree of Jesse from York Minster (c. 1170), the oldest stained-glass window in England.

Rose window of Notre Dame de Mantes (c. 1210)

West rose window of Notre Dame de Paris (c. 1220)

See also

- Gothic architecture

- Gothic cathedrals and churches

- High Gothic

- Rayonnant

- Flamboyant

- French Gothic architecture

- English Gothic architecture

- Architecture of Normandy

References

- Trintignac & Coloni 1984, p. 44–45.

Bibliography

- Bony, Jean (1985). French Gothic Architecture of the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-05586-1.

- Ducher, Robert (2014). Caractéristique des Styles (in French). Flammarion. ISBN 978-2-0813-4383-2.

- Houvet, E (2019). Miller, Malcolm B (ed.). Chartres - Guide of the Cathedral. Éditions Houvet. ISBN 2-909575-65-9.

- Mignon, Olivier (2015). Architecture des Cathédrales Gothiques (in French). Éditions Ouest-France. ISBN 978-2-7373-6535-5.

- Mignon, Olivier (2017). Architecture du Patrimoine Française - Abbayes, Églises, Cathédrales et Châteaux (in French). Éditions Ouest-France. ISBN 978-27373-7611-5.

- Renault, Christophe; Lazé, Christophe (2006). Les Styles de l'architecture et du mobilier (in French). Gisserot. ISBN 9-782877-474658.

- Rivière, Rémi; Lavoye, Agnès (2007). La Tour Jean sans Peur, Association des Amis de la tour Jean sans Peur. ISBN 978-2-95164-940-8

- Trintignac, André; Coloni, Marie-Jeanne (1984). Decouvrir Notre-Dame de Paris (in French). Paris: Cerf. ISBN 2-204-02087-7.

- Texier, Simon, (2012), Paris Panorama de l'architecture de l'Antiquité à nos jours, Parigramme, Paris (in French), ISBN 978-2-84096-667-8

- Watkin, David (1986). A History of Western Architecture. Barrie and Jenkins. ISBN 0-7126-1279-3.

- Wenzler, Claude (2018), Cathédales Cothiques - un Défi Médiéval, Éditions Ouest-France, Rennes (in French) ISBN 978-2-7373-7712-9

- Le Guide du Patrimoine en France (2002), Éditions du Patrimoine, Centre des Monuments Nationaux (in French) ISBN 978-2-85822-760-0

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Early_Gothic_architecture

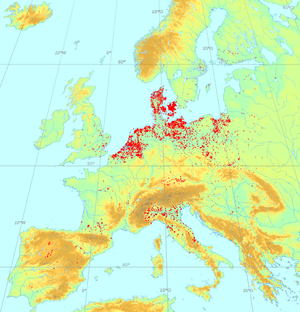

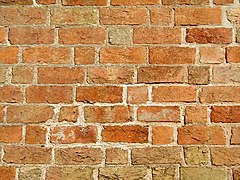

Brick Gothic

Brick Gothic (German: Backsteingotik, Polish: Gotyk ceglany, Dutch: Baksteengotiek) is a specific style of Gothic architecture common in Northeast and Central Europe especially in the regions in and around the Baltic Sea, which do not have resources of standing rock (though glacial boulders are sometimes available). The buildings are essentially built using bricks. Buildings classified as Brick Gothic (using a strict definition of the architectural style based on the geographic location) are found in Belgium (and the very north of France), Netherlands, Germany, Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Kaliningrad (former East Prussia), Denmark, Sweden and Finland.

As the use of baked red brick arrived in Northwestern and Central Europe in the 12th century, the oldest such buildings are classified as the Brick Romanesque. In the 16th century, Brick Gothic was superseded by Brick Renaissance architecture.

Brick Gothic is characterised by the lack of figurative architectural sculpture, widespread in other styles of Gothic architecture. Typical for the Baltic Sea region is the creative subdivision and structuring of walls, using built ornaments and the colour contrast between red bricks, glazed bricks and white lime plaster. Nevertheless, these characteristics are neither omnipresent nor exclusive. Many of the old town centres dominated by Brick Gothic, as well as some individual structures, have been listed as UNESCO World Heritage sites.

The real extent and the real variety of this brick architecture is yet to be fully distinguished from the views published in the late 19th and early 20th century, especially the years around the end of World War I, when the style was politically instrumentalized.[clarification needed]

Indeed, about a quarter of medieval Gothic brick architecture is standing in the Netherlands, in Flanders and in French Flanders. Some of these buildings are in a combination of brick and stone. The towers of St Mary's church in Lübeck, the most significant Brick Gothic church of the Baltic Sea region, have corners of granite ashlar. Many village churches in northern Germany and Poland have a Brick Gothic design despite the main constituent of their walls being boulders.

Brick Gothic architecture

In contrast to other styles, the definition of Brick Gothic is based on the material (brick), and a geographical area (countries around the Baltic Sea). In addition, there are more remote regions with brick buildings bearing characteristics of this architectural style further south, east and west—these include Bavaria, and western Ukraine and Belarus, along with eastern England and the southern tip of Norway.

Historical conditions

In the course of the medieval German eastward expansion, Slavic areas east of the Elbe were settled by traders and colonists from the overpopulated Northwest of Germany in the 12th and 13th centuries. In 1158, Henry the Lion founded Lübeck, in 1160 he conquered the Slavic principality of Schwerin. This partially violent colonisation was accompanied by the Christianisation of the Slavs and the foundation of dioceses at Ratzeburg, Schwerin, Cammin, Brandenburg and elsewhere.

The newly founded cities soon joined the Hanseatic League and formed the "Wendic Circle", with its centre at Lübeck, and the "Gotland-Livland Circle", with its main centre at Tallinn (Reval). The affluent trading cities of the Hansa were characterised especially by religious and secular representative architecture, such as council or parish churches, town halls, Bürgerhäuser, i.e. the private dwellings of rich traders, or city gates. In rural areas, the monastic architecture of monks' orders had a major influence on the development of brick architecture, especially through the Cistercians and Premonstratensians. Between Prussia and Estonia, the Teutonic Knights secured their rule by erecting numerous Ordensburgen (castles), most of which were also brick-built.

In the regions along the southern coast of the Baltic Sea, the use of brick arrived almost at the same time as the art of masonry. But in Denmark, especially Jutland, in the Frisian regions, in present-day Netherlands and in the Lower Rhine region, many high-quality medieval stone buildings were built before the first medieval brick was burnt there. Nevertheless, these regions eventually developed a density of Gothic brick architecture as high as in the regions near the southern coast of the Baltic Sea. The central and southern regions of Poland also had some important early stone buildings, especially the famous round churches. Many of these buildings were later enlarged or replaced using brick in a Gothic style. Especially in Flanders, the Netherlands, the lower Rhine region, Lesser Poland and Upper Silesia, Brick Gothic buildings often, but not alway, have some elements of stone ashlar. In the Netherlands it was mostly tufa, in Denmark old squared granite and new limestone. On the other hand, in many regions regarded as typical for Brick Gothic, boulders were cheaper than brick, and therefore many buildings were erected using boulders, and only decorated by brick, all through the period of Gothic architecture.

Development

Brick building became prevalent in the 12th century, still within the Romanesque architecture period. Wooden architecture had long dominated in northern Germany but was inadequate for the construction of monumental structures. Throughout the area of Brick Gothic, half-timbered architecture remained typical for smaller buildings, especially in rural areas, well into modern times.

The techniques of building and decorating in bricks were imported from Lombardy. Also some decorative forms of Lombard architecture were adopted.[1]

In the areas dominated by the Welfs, the use of brick to replace natural stone began with cathedrals and parish churches at Oldenburg (Holstein), Segeberg, Ratzeburg, and Lübeck. Henry the Lion laid the foundation stone of the Cathedral in 1173.

In the Margraviate of Brandenburg, the lack of natural stone and the distance to the Baltic Sea (which, like the rivers, could be used for transporting heavy loads) made the need for alternative materials more pressing. Brick architecture here started with the Cathedral of Brandenburg, begun in 1165 under Albert the Bear. Jerichow Monastery (then a part of the Archbishopric of Magdeburg), where construction started as early as 1149, was a key influence on Brick Gothic in Brandenburg.

Characteristics

Romanesque brick architecture remained closely connected with contemporary stone architecture and often simply translated the latter's style and repertoire into the new material. The decorative techniques to suit the new material were imported form northern Italy, where they had been developed as part of the Lombard Style. Among these techniques was the use of moulded brick to realize delicate ornament. Brick Gothic drew on Romanesque building (in stone and in brick) of its region, but in its core area Romanesque stone buildings were rare and often humble In character.

In most regions of Brick Gothic, boulders were available and cheaper than brick. In some regions, cut stone was available as well. Therefore, besides all-brick buildings, there are buildings begun in stone and completed using brick, or built of boulders and decorated with brick, or built of brick and decorated with cut stone, for instance in Lesser Poland and Silesia.

Brick Gothic buildings are often of monumental size, but simple as regards their external appearance, lacking the delicacy of areas further south, but this is not exclusively the case.

None of these buildings is exactly the same today as in the Middle Ages. For instance, many of them have had alterations in a Baroque style and have then been re-gothicized in the 19th century (or reconstructed after World War II). Especially in the 19th century, some buildings were purified during restoration.[2] In the city halls of Lübeck and Stralsund, medieval window framings of stone were replaced by new ones of brick.

At a time when ordinary people lived very locally based lives, the groups responsible for these buildings were internationally mobile: the bishops, abbots, aristocrats, and long-distance merchants who commissioned the work, and the highly skilled specialist craftsmen who carried it out. For this reason the Brick Gothic of the countries around the Baltic Sea was strongly influenced by the cathedrals of France and by the gothique tournaisien or Scheldt Gothic of the County of Flanders (where also some important Brick Gothic was erected).

One typical expression of the structure of walls, the contrast of prominent visible brick with the plastering of recessed areas, had already been developed in Italy, but became prevalent in the Baltic region.

Brick as the basic material

Since the bricks used were made of clay, available in copious quantities in the Northern German Plain, they quickly became the normal replacement for building stone. The so-called monastic format became the standard for bricks used in representative buildings. Its bricks measure circa 28 x 15 x 9 cm to 30 x 14 x 10 cm, with mortar joints of about 1.5 cm. In contrast to hewn-stone Gothic, the bricks and shaped bricks were not produced locally by lodges (Bauhütten), but by specialised enterprises off-site.

Glazed brick

Elements

The use of shaped bricks for tracery and friezes also can be found in some buildings of northwestern Gothic brick architecture. Masterly use of these elements is found in some of the Gothic buildings of northern Italy, where these highly sophisticated techniques had originally come from, having been developed in the Lombard Romanesque period. There, such brick decorations can even be found on buildings which had been mainly erected in ashlar. Some Italian Gothic brick buildings also have friezes of terracotta.

While in central northern Germany and in Greater Poland suitable natural building stone was unavailable, trading cities could import it by sea. Therefore, St. Mary's Church in Lübeck, generally considered the principal example of Brick Gothic, has two portals made of sandstone, and the edges of its huge towers are built of ashlars, as normal for Gothic brick buildings in the Netherlands and the (German) Lower Rhine region. And the very slim pillars of its Briefkapelle (letters chapel) are of granite from Bornholm.[3] In the Gothic brick towers of the churches of Wismar and of St. Nicholas' Church in Stralsund, stone is not used for structural reasons but to provide a contrast of colours. At St. Mary's of Gdańsk, all five lateral portals and some simple but long cornices are of ashlar.

Germany

Brick architecture is found primarily in areas that lack sufficient natural supplies of building stone. This is the case across the Northern European Lowlands. Since the German part of that region (the Northern German Plain, except Westphalia and the Rhineland) is largely concurrent with the area influenced by the Hanseatic League, Brick Gothic has become a symbol of that powerful alliance of cities. Along with the Low German Language, it forms a major defining element of the Northern German cultural area, especially in regard to late city foundations and the areas of colonisation north and east of the Elbe. In the Middle Ages and Early Modern Period, that cultural area extended throughout the southern part of the Baltic region and had a major influence on Scandinavia. The southernmost Brick Gothic structure in Germany is the Bergkirche (mountain church) of Altenburg in Thuringia.

In the northwest, especially along Weser and Elbe, sandstone from the mountains of Central Germany could be transported with relative ease. This resulted in a synthesis of the styles from east of the Elbe with the architectural traditions of the Rhineland. Here, bricks were mainly used for wall areas, while sandstone was employed for plastic detail. Since the brick has no aesthetic function per se in this style, most of the northwest German structures are not part of Brick Gothic proper. The Gothic brick buildings near the Lower Rhine have more in common with the Dutch Gothic than with the northern German one.

Bavarian Brick Gothic

In Bavaria, there is a significant number of Gothic brick buildings, some in places without quarries, like Munich, and some in places, where natural stone was available as well, such as Donauwörth. Several of these buildings have both decorations of shaped bricks and of ashlar, often tuff. Also the walls of some buildings are all brick, but in some buildings the base of the wall is of stone. Most of the churches share a common distinctive Bavarian Brick Gothic style. The Frauenkirche of Munich is the largest (gothic and totally) brick church north of the Alps. Examples include St. Martin's and two other churches at Landshut and the Herzogsburg (Duke's Castle) in Dingolfing.

Poland

Brick Gothic in Poland is sometimes described as belonging to the Polish Gothic style. Though, the vast majority of Gothic buildings within the borders of modern Poland are brick-built, the term also encompasses non-brick Gothic structures, such as the Wawel Cathedral in Kraków, which is mostly stone-built. The principal characteristic of the Polish Gothic style is its limited use of stonework to complement the main brick construction. Stone was primarily utilized for window and door frames, arched columns, ribbed vaults, foundations and ornamentation, while brick remained the core building material used to erect walls and cap ceilings. This limited use of stone, as a supplementary building material, was most prevalent in Lesser Poland and was made possible by an abundance of limestone in the region—further north in the regions of Greater Poland, Silesia, Mazovia, and Pomerania the use of stone was virtually nonexistent.

Brick Gothic in Pomerania

Much of the coast of the Baltic Sea in the period from the 12th century to 1637 belonged to the Griffins' Duchy of Pomerania. Nowadays its territory is divided into two parts—middle and eastern in Poland and westernmost in Germany. The most outstanding Gothic monuments in this area are Romanesque-Gothic Cathedral of St. John the Baptist in Kamień Pomorski, Cistercian abbey in Kołbacz, ruins of Jasienica Abbey in Police, ruins of Eldena Abbey (a Danish foundation) in Greifswald, St. Mary's Church in Usedom, Castle of the Pomeranian Dukes in Darłowo, remnants of Löcknitz Castle, St. Nicholas collegial church in Greifswald, St. Nicholas' Church in Stralsund, St. Mary's Church in Stralsund, St. Mary and St. Nicholas churches in Anklam, St. Mary's Church in Stargard, St. Nicholas Church in Wolin, St. Peter's Church in Wolgast, Cathedral Basilica of St. James the Apostle in Szczecin, Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception of the Blessed Virgin Mary in Koszalin, Basilica of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary in Kołobrzeg and Church of Our Lady in Sławno and city halls in Stralsund, Szczecin (Old Town Hall) and Kamień Pomorski. The most important defensive systems were located in Szczecin and Dąbie (present district of the city of Szczecin), Pyrzyce, Usedom, Greifswald, Anklam and Stargard with the water gate on Ina river called Stargard Mill Gate.

France

Northern France

Even the Westhoek region in the very north of France, situated between Belgium and the Strait of Dover has instances of northern Brick Gothic, with a high density of specific buildings.[clarification needed] For example, there is a strong similarity between the Belfry of Dunkirk and the tower of St Mary's Church in Gdańsk.

Southern French Gothic

Southern French Gothic is a specific style of Gothic architecture developed in the south of France. It arose in the early 13th century following the victory of the Catholic church over the Cathars, as the church sought to re-establish its authority in the region. As a result, church buildings typically present features drawn from military architecture. The construction material of Southern French Gothic is typically brick rather than stone. Over time, the style came to influence secular buildings as well as churches and spread beyond the area where Catharism had flourished.

Gothic Revival – 19th-century Neo-gothic

In the 19th century, the Gothic Revival—Neogothic style led to a revival of Brick Gothic designs. 19th-century Brick Gothic "Revival" churches can be found throughout Northern Germany, Scandinavia, Poland, Lithuania, Finland, the Netherlands, Russia, Britain and the United States.

Important churches in this style included St Chad's Cathedral, Birmingham (1841) by Augustus Pugin, the 1897 Mikkeli Cathedral in Mikkeli in Finland, and St. Joseph's Church in Kraków, Poland is a late example of the revival style.

See also

- List of Gothic brick buildings

- European Route of Brick Gothic

- Gothic architecture in modern Poland

- Gothic architecture in Lithuania

- Belarusian Gothic

- List of Brick Romanesque buildings

- List of Brick Renaissance buildings

Notes and references

- "Archived Document". Archived from the original on 18 January 2016. Retrieved 18 January 2016.

- Hans Josef Böker: Die mittelalterliche Backsteinarchitektur Norddeutschlands. Darmstadt 1988. ISBN 3-534-02510-5

- Gottfried Kiesow: Wege zur Backsteingotik. Eine Einführung. Monumente-Publikationen der Deutschen Stiftung Denkmalschutz, Bonn 2003, ISBN 3-936942-34-X

- Angela Pfotenhauer, Florian Monheim, Carola Nathan: Backsteingotik. Monumente-Edition. Monumente-Publikation der Deutschen Stiftung Denkmalschutz, Bonn 2000, ISBN 3-935208-00-6

- Fritz Gottlob: Formenlehre der Norddeutschen Backsteingotik: Ein Beitrag zur Neogotik um 1900. 1907. Reprint of 2nd ed., Verlag Ludwig, 1999, ISBN 3-9805480-8-2

- Gerlinde Thalheim (ed.) et al.: Gebrannte Größe – Wege zur Backsteingotik. 5 Vols. Monumente-Publikation der Deutschen Stiftung Denkmalschutz, Bonn, Gesamtausgabe aller 5 Bände unter ISBN 3-936942-22-6

- B. Busjan, G. Kiesow: Wismar: Bauten der Macht – Eine Kirchenbaustelle im Mittelalter. Monumente Publikationen der Deutschen Stiftung Denkmalschutz, 2002, ISBN 3-935208-14-6 (Vol. 2 of series of exhibition catalogues Wege zur Backsteingotik, ISBN 3-935208-12-X)

External links

- RDK-Labor: digitized text of Reallexikon zur Deutschen Kunstgeschichte (1937), Backsteinbau by Otto Stiehl (chapters I–III) and Hans Wentzel (chapters IV–VI)

- European Brick Gothic Route

- Exhibition Wege zur Backsteingotik 2002–2005

- Permanent exhibition Wege zur Backsteingotik, Wismar

No comments:

Post a Comment