Veterinary medicine is the branch of medicine that deals with the prevention, management, diagnosis, and treatment of disease, disorder, and injury in animals. Along with this, it deals with animal rearing, husbandry, breeding, research on nutrition, and product development. The scope of veterinary medicine is wide, covering all animal species, both domesticated and wild, with a wide range of conditions that can affect different species.

Veterinary medicine is widely practiced, both with and without professional supervision. Professional care is most often led by a veterinary physician (also known as a veterinarian, veterinary surgeon, or "vet"), but also by paraveterinary workers, such as veterinary nurses, veterinary technicians, and veterinary assistants. This can be augmented by other paraprofessionals with specific specialties, such as animal physiotherapy or dentistry, and species-relevant roles such as farriers.

Veterinary science helps human health through the monitoring and control of zoonotic disease (infectious disease transmitted from nonhuman animals to humans), food safety, and through human applications via medical research. They also help to maintain food supply through livestock health monitoring and treatment, and mental health by keeping pets healthy and long-living. Veterinary scientists often collaborate with epidemiologists and other health or natural scientists, depending on type of work. Ethically, veterinarians are usually obliged to look after animal welfare. Veterinarians diagnose, treat, and help keep animals safe and healthy.

History

Premodern era

Archeological evidence, in the form of a cow skull upon which trepanation had been performed, shows that people were performing veterinary procedures in the Neolithic (3400–3000 BCE).[1]

The Egyptian Papyrus of Kahun (Twelfth Dynasty of Egypt) is the first extant record of veterinary medicine.[2]

The Shalihotra Samhita, dating from the time of Ashoka, is an early Indian veterinary treatise. The edicts of Asoka read: "Everywhere King Piyadasi (Asoka) made two kinds of medicine (चिकित्सा) available, medicine for people, and medicine for animals. Where no healing herbs for people and animals were available, he ordered that they be bought and planted."[3]

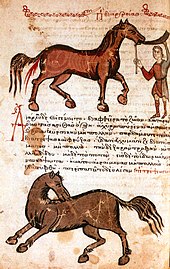

Hippiatrica is a Byzantine compilation of hippiatrics, dated to the fifth or sixth century AD.[4]

The first attempts to organize and regulate the practice of treating animals tended to focus on horses because of their economic significance. In the Middle Ages, farriers combined their work in horseshoeing with the more general task of "horse doctoring". The Arabic tradition of Bayṭara, or Shiyāt al-Khayl, originates with the treatise of Ibn Akhī Hizām (fl. late ninth century).

In 1356, the Lord Mayor of London, concerned at the poor standard of care given to horses in the city, requested that all farriers operating within a 7-mile (11-km) radius of the City of London form a "fellowship" to regulate and improve their practices. This ultimately led to the establishment of the Worshipful Company of Farriers in 1674.[5]

Meanwhile, Carlo Ruini's book Anatomia del Cavallo (Anatomy of the Horse) was published in 1598. It was the first comprehensive treatise on the anatomy of a nonhuman species.[6]

Establishment of profession

The first veterinary school was founded in Lyon, France, in 1762 by Claude Bourgelat.[7] According to Lupton,[8] after observing the devastation being caused by cattle plague to the French herds, Bourgelat devoted his time to seeking out a remedy. This resulted in founding a veterinary school in Lyon in 1761, from which establishment he dispatched students to combat the disease; in a short time, the plague was stayed and the health of stock restored, through the assistance rendered to agriculture by veterinary science and art.[8] The school received immediate international recognition in the 18th century and its pedagogical model drew on the existing fields of human medicine, natural history, and comparative anatomy.[9]

The Odiham Agricultural Society was founded in 1783 in England to promote agriculture and industry,[10] and played an important role in the foundation of the veterinary profession in Britain. A founding member, Thomas Burgess, began to take up the cause of animal welfare and campaign for the more humane treatment of sick animals.[11] A 1785 society meeting resolved to "promote the study of Farriery upon rational scientific principles."

Physician James Clark wrote a treatise entitled Prevention of Disease in which he argued for the professionalization of the veterinary trade, and the establishment of veterinary colleges. This was finally achieved in 1790, through the campaigning of Granville Penn, who persuaded Frenchman Benoit Vial de St. Bel to accept the professorship of the newly established veterinary college in London.[10] The Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons was established by royal charter in 1844. Veterinary science came of age in the late 19th century, with notable contributions from Sir John McFadyean, credited by many as having been the founder of modern veterinary research.[12]

In the United States, the first schools were established in the early 19th century in Boston, New York City, and Philadelphia. In 1879, Iowa Agricultural College became the first land-grant college to establish a school of veterinary medicine.[13]

Veterinary workers

Veterinary physicians

Veterinary care and management are usually led by a veterinary physician (usually called a veterinarian, veterinary surgeon or "vet" - doctor of veterinary medicine or veterinary medical doctor). This role is the equivalent of a physician or surgeon (medical doctor) in human medicine, and involves postgraduate study and qualification.

In many countries, the local nomenclature for a vet is a protected term, meaning that people without the prerequisite qualifications and/or registration are not able to use the title, and in many cases, the activities that may be undertaken by a vet (such as animal treatment or surgery) are restricted only to those people who are registered as vet. For instance, in the United Kingdom, as in other jurisdictions, animal treatment may be performed only by registered vets (with a few designated exceptions, such as paraveterinary workers), calling oneself a vet without being registered or performing any treatment is illegal.

Most vets work in clinical settings, treating animals directly. They may be involved in a general practice, treating animals of all types; may be specialized in a specific group of animals such as companion animals, livestock, laboratory animals, zoo animals, or horses; or may specialize in a narrow medical discipline such as veterinary surgery, dermatology, cardiology, neurology, laboratory animal medicine, internal medicine, and more.

As with healthcare professionals, vets face ethical decisions about the care of their patients. Current debates within the profession include the veterinary ethics of purely cosmetic procedures on animals, such as declawing of cats, docking of tails, cropping of ears, and debarking on dogs.

A wide range of surgeries and operations is performed on various types of animals, but not all of them are carried out by vets. In a case in Iran, for instance, an eye surgeon managed to perform a successful cataract surgery on a rooster for the first time in the world.[14]

Paraveterinary workers

Paraveterinary workers, including veterinary nurses, veterinary technicians, and veterinary assistants, either assist vets in their work, or may work within their own scope of practice, depending on skills and qualifications, including in some cases, performing minor surgery.

The role of paraveterinary workers is less homogeneous globally than that of a vet, and qualification levels, and the associated skill mix, vary widely.

Allied professions

A number of professions exist within the scope of veterinary medicine, but may not necessarily be performed by vets or veterinary nurses. This includes those performing roles which are also found in human medicine, such as practitioners dealing with musculoskeletal disorders, including osteopaths, chiropractors, and physiotherapists.

Some roles are specific to animals, but which have parallels in human society, such as animal grooming and animal massage. Some roles are specific to a species or group of animals, such as farriers, who are involved in the shoeing of horses, and in many cases have a major role to play in ensuring the medical fitness of horses.

Veterinary research

Veterinary research includes prevention, control, diagnosis, and treatment of diseases of animals, and basic biology, welfare, and care of animals. Veterinary research transcends species boundaries and includes the study of spontaneously occurring and experimentally induced models of both human and animal diseases and research at human-animal interfaces, such as food safety, wildlife and ecosystem health, zoonotic diseases, and public policy.[15] By value the most important Animal Health pharmaceutical supplier worldwide is by far Zoetis (United States).[16]

Clinical veterinary research

As in medicine, randomized controlled trials also are fundamental in veterinary medicine to establish the effectiveness of a treatment.[17] Clinical veterinary research is far behind human medical research, though, with fewer randomized controlled trials, that have a lower quality and are mostly focused on research animals.[18] Possible improvement consists in creation of networks for inclusion of private veterinary practices in randomized controlled trials. Although the FDA approves drugs for use in humans, the FDA keeps a separate "Green Book", which lists drugs approved specifically for veterinary medicine (about half of which are separately approved for use in humans).[1][19]

No studies exist on the effect of community animal health services on improving household wealth and the health status of low-income farmers.[20]

The first recorded use of regenerative stem-cell therapy to treat lesions in a wild animal occurred in 2011 in Brazil.[21] On that occasion, the Zoo Brasília used stem cells to treat a maned wolf who had been run over by a car, which was later returned, fully recovered, to nature.[21]

See also

- Animal drug

- Animal science

- Federation of Veterinarians of Europe

- Lists of animal diseases

- National Office of Animal Health

- One Health

- Pet orthotics

- Technology in veterinary medicine

- WikiVet

By country

- Veterinary medicine in the United Kingdom

- Veterinary medicine in the United States

- History of veterinary medicine in the Philippines

- Veterinary Council of India

- Veterinary Council of Ireland

References

- Conselho Federal de Medicina Veterinária: "Tratamento", 11 January 2011, (in portuguese). Retrieved 4 May 2022.

Further reading

Introductory textbooks and references

- Aspinall, Victoria; Cappello, Melanie; Bowden, Sally (2009), Introduction to Veterinary Anatomy and Physiology Textbook, Jeffery, Andrea (forward), Elsevier Health Sciences, ISBN 978-0-7020-2938-7

- Boden, Edward; West, Geoffrey Philip (1998), Black's veterinary dictionary, Rowman & Littlefield, ISBN 978-0-389-21017-7

- Done, Stanley H. (1996), Color atlas of veterinary anatomy: The dog & cat, Elsevier Health Sciences, ISBN 978-0-7234-2441-3

- Dyce, Keith M.; Sack, Wolfgang O.; Wensing, Cornelis Johannes Gerardus (2010), Textbook of veterinary anatomy, Saunders, ISBN 978-1-4160-6607-1

- Fenner, William R. (2000), Quick reference to veterinary medicine, John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 978-0-397-51608-7

- Lawhead, James B.; Baker, MeeCee (2009), Introduction to veterinary science, Cengage Learning, ISBN 978-1-4283-1225-8

- Pfeiffer, Dirk (2009), Veterinary Epidemiology: An Introduction, John Wiley and Sons, ISBN 978-1-4051-7694-1

- Radostits, O. M.; Gay, C. C.; Blood, D. C.; Arundel, J. H.; Hinchcliff, Kenneth W (2000), Veterinary Medicine: A Textbook of the Diseases of Cattle, Sheep, Pigs, Goats and Horses (9th ed.), Elsevier Health Sciences, p. 1877, ISBN 978-0-7020-2604-1

Monographs and other speciality texts

- Dunlop, Robert H.; Malbert, Charles-Henri (2004), Veterinary pathophysiology, Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN 978-0-8138-2826-8

- Eurell, Jo Ann Coers; Eurell, Jo Ann; Frappier, Brian L.; Dellman, Horst-Dieter (25 May 2006), Dellmann's textbook of veterinary histology, Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN 978-0-7817-4148-4

- Foreyt, William J.; Foreyt, Bill (2001), Veterinary parasitology reference manual, Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN 978-0-8138-2419-2

- Gupta, Ramesh Chandra (2007), Veterinary toxicology: basic and clinical principles, Academic Press, ISBN 978-0-12-370467-2

- Hirsh, Dwight C.; Maclachlan, Nigel James; Walker, Richard L. (2004), Veterinary microbiology, Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN 978-0-8138-0379-1

- Hunter, Pamela (2004), Veterinary Medicine: A Guide to Historical Sources, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., p. 611, ISBN 978-0-7546-4053-0

- Merck, Melinda D. (2007), Veterinary forensics: animal cruelty investigations, John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 978-0-8138-1501-5

- Murphy, Frederick A. (1999), Veterinary virology, Academic Press, ISBN 978-0-12-511340-3

- Nicholas, Frank W. (2009), Introduction to Veterinary Genetics, John Wiley and Sons, ISBN 978-1-4051-6832-8

- Robinson, Wayne F.; Huxtable, Clive R. R. (2004), Clinicopathologic Principles for Veterinary Medicine, Cambridge University Press, p. 452, ISBN 978-0-521-54813-7

- Slatter, Douglas H. (2002), Textbook of small animal surgery, Elsevier Health Sciences, ISBN 978-0-7216-8607-3

- Kahn, Cynthia M., ed. (2010), The Merck Veterinary Manual, Whitehouse Station, N.J., Merck, ISBN 978-0-911910-93-3

- Thrusfield, Michael (2007), Veterinary epidemiology, Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN 978-1-4051-5627-1

- Zajac, A.; Conboy, Gary A.; American Association of Veterinary Parasitologists (2006), Veterinary clinical parasitology, John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 978-0-8138-1734-7

Veterinary nursing, ophthalmology, and pharmacology

- Adams, H. Richard (2001), Veterinary pharmacology and therapeutics, Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN 978-0-8138-1743-9

- Bryant, Susan (2010), Anesthesia for Veterinary Technicians, John Wiley and Sons, ISBN 978-0-8138-0586-3

- Cannon, Marthaxcx; Hijfte, Myra Forster-van (2006), Feline medicine: a practical guide for veterinary nurses and technicians, Elsevier Health Sciences, ISBN 978-0-7506-8827-7

- Crispin, Sheila M. (2005), Notes on veterinary ophthalmology, Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN 978-0-632-06416-8

- Gelatt, Kirk N. (2000), Essentials of veterinary ophthalmology, Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN 978-0-683-30077-2

- Lane, D. R.; Cooper, B. (2003), Veterinary nursing, Elsevier Health Sciences, ISBN 978-0-7506-5525-5

- Pattengale, Paula (2004), Tasks for the veterinary assistant, Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN 978-0-7817-4243-6

- Riviere, Jim E.; Papich, Mark G. (2009), Veterinary pharmacology and therapeutics, John Wiley and Sons, ISBN 978-0-8138-2061-3

Related fields

- Anthony, David; University of Pennsylvania. University Museum (1984), Man and animals: living, working, and changing together : in celebration of the 100th anniversary, the School of Veterinary Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, UPenn Museum of Archaeology, ISBN 978-0-934718-68-4

- Catanzaro, Thomas E. (1998), Building the Successful Veterinary Practice: Innovation and creativity, Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN 978-0-8138-2984-5

- Finger, Stanley (2001), Origins of neuroscience: a history of explorations into brain function, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-514694-3

- Rollin, Bernard E. (2006), An introduction to veterinary medical ethics: theory and cases, Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN 978-0-8138-0399-9

- Sherman, David M. (2002), Tending animals in the global village: a guide to international veterinary medicine, John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 978-0-683-18051-0

- Shilcock, Maggie; Stutchfield, Georgina (2003), Veterinary practice management: a practical guide, Elsevier Health Sciences, ISBN 978-0-7020-2696-6

- Smith, Gary; Kelly, Alan M., eds. (2008), Food Security in a Global Economy: Veterinary Medicine and Public Health, Phila.: University of Pennsylvania Press, p. 176, ISBN 978-0-8122-2044-5

- Swabe, Joanna (1999), Animals, Disease, and Human Society: Human-animal Relations and the Rise of Veterinary Medicine, Routledge, p. 243, ISBN 978-0-415-18193-8

- Swope, Robert E.; Rigby, Julie (2001), Opportunities in veterinary medicine careers, McGraw-Hill Professional, p. 151, ISBN 978-0-658-01055-2

- Swabe, Joanna (1999), Veterinary Courses and CE., p. 244, ISBN 978-0-415-18193-8, archived from the original on 8 February 2019, retrieved 8 March 2022

- Anthony, David; Zoetis (2014), VeritasDVM, Dr. Donal Smith, ISBN 978-0-934718-68-4, archived from the original on 8 February 2019, retrieved 8 March 2022

External links

The dictionary definition of veterinary medicine at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of veterinary medicine at Wiktionary Media related to Veterinary medicine at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Veterinary medicine at Wikimedia Commons

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Veterinary_medicine

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/dental_medicine

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/medicine

No comments:

Post a Comment