Georgian

- Anything related to, or originating from Georgia (country)

- Georgians, an indigenous Caucasian ethnic group

- Georgian language, a Kartvelian language spoken by Georgians

- Georgian scripts, three scripts used to write the language

- Georgian (Unicode block), a Unicode block containing the Mkhedruli and Asomtavruli scripts

- Georgian cuisine, cooking styles and dishes with origins in the nation of Georgia and prepared by Georgian people around the world

- Someone from Georgia (U.S. state)

- Georgian era, a period of British history (1714–1837)

- Georgian architecture, the set of architectural styles current between 1714 and 1837

Places

- Georgian Bay, a bay of Lake Huron

- Georgian Cliff, a cliff on Alexander Island, Antarctica

Airlines

- Georgian Airways, an airline based in Tbilisi, Georgia

- Georgian International Airlines, an airline based in Tbilisi, Georgia

- Air Georgian, an airline based in Ontario, Canada

- Sky Georgia, an airline based in Tbilisi, Georgia

Schools

- Georgian College, in Barrie, Ontario, Canada

- Georgian International Academy, a research and academic institution in Tbilisi, Georgia

- Georgian Technical University, a technical university in Tbilisi, Georgia

Arts and entertainment

- The Georgians (Frank Guarente), an American jazz and dance band of the 1920s

- The Georgians (Nat Gonella), a British jazz band of the 1930s

- Georgian poets, a group of early 20th century English poets

- Georgian Theatre Royal, a theatre and playhouse in Richmond, North Yorkshire, UK

People

- Georgian Păun (born 1985), Romanian footballer

- Georgian Popescu (born 1984), Romanian amateur boxer

- Georgian Tobă (born 1989), Romanian footballer

Other uses

- Atlanta Georgian, a defunct Hearst-owned newspaper

- Augusta Georgians, an American minor league baseball team from 1920 to 1921

- Georgian Mall, a mall in Barrie, Ontario, Canada

- Georgian (train), a Chicago-to-Atlanta passenger train route

See also

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Georgian

Georgians

The Georgian kings, queens consort and the Catholicos-Patriarch depicted on a Byzantine-influenced fresco[a] wearing Byzantine dress at the Gelati Monastery, UNESCO's World Heritage Site landmark.[3] | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| c. 4 million[b] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

For more, see list of population and statistical data | |

| Languages | |

| Georgian and other Kartvelian languages | |

| Religion | |

| Predominant: Significant: |

The Georgians, or Kartvelians (/kɑːrtˈvɛliənz/; Georgian: ქართველები, romanized: kartvelebi, pronounced [kʰɑɾtʰvɛlɛbi]), are a nation and indigenous Caucasian ethnic group native to Georgia and the South Caucasus. Georgian diaspora communities are also present throughout Russia, Turkey, Greece, Iran, Ukraine, United States, and European Union.

Georgians arose from Colchian and Iberian civilizations of classical antiquity; Colchis was interconnected with the Hellenic world, whereas Iberia was influenced by the Achaemenid Empire until Alexander the Great conquered it.[7] In the 4th century, the Georgians became one of the first to embrace Christianity and now the majority of Georgians are Orthodox Christians, with most following their national autocephalous Georgian Orthodox Church,[8][9] although there are small Georgian Catholic and Muslim communities as well as a significant number of irreligious Georgians. Located in the Caucasus, on the continental crossroads of Europe and Asia, the High Middle Ages saw Georgian people form a unified Kingdom of Georgia in 1008 AD,[10][11][12] the pan-Caucasian empire,[13] later inaugurating the Georgian Golden Age, a height of political and cultural power of the nation. This lasted until the kingdom was weakened and later disintegrated as the result of the 13th–15th-century invasions of the Mongols and Timur,[14] the Black Death, the Fall of Constantinople, as well as internal divisions following the death of George V the Brilliant in 1346, the last of the great kings of Georgia.[15]

Thereafter and throughout the early modern period, Georgians became politically fractured and were dominated by the Ottoman Empire and successive dynasties of Iran. Georgians started looking for allies and found the Russians on the political horizon as a possible replacement for the lost Byzantine Empire, "for the sake of the Christian faith".[16] The Georgian kings and Russian tsars exchanged no less than 17 embassies,[17] which culminated in 1783, when Heraclius II of the eastern Georgian kingdom of Kartli-Kakheti forged an alliance with the Russian Empire. The Russo-Georgian alliance, however, backfired as Russia was unwilling to fulfill the terms of the treaty, proceeding to annex[18][19] the troubled kingdom in 1801[20] as well as the western Georgian kingdom of Imereti in 1810.[21] There were several uprisings and movements to restore the statehood, the most notable being the 1832 plot, which collapsed in failure.[22] Eventually, Russian rule over Georgia was acknowledged in various peace treaties with Iran and the Ottomans, and the remaining Georgian territories were absorbed by the Russian Empire in a piecemeal fashion through the course of the 19th century. Georgians briefly reasserted their independence from Russia under the First Georgian Republic from 1918 to 1921 and finally in 1991 from the Soviet Union.

The Georgian nation was formed out of a diverse set of geographic subgroups, each with its characteristic traditions, manners, dialects and, in the case of Svans and Mingrelians, own regional languages. The Georgian language, with its own unique writing system and extensive written tradition, which goes back to the 5th century, is the official language of Georgia as well as the language of education of all Georgians living in the country. According to the State Ministry on Diaspora Issues of Georgia, unofficial statistics say that there are more than 5 million Georgians in the world.[23]

Etymology

Georgians call themselves Kartvelebi (ქართველები), their land Sakartvelo (საქართველო), and their language Kartuli (ქართული).[26][27] According to The Georgian Chronicles, the ancestor of the Kartvelian people was Kartlos, the great-grandson of the Biblical Japheth. However, scholars agree that the word is derived from the Karts, the latter being one of the proto-Georgian tribes that emerged as a dominant group in ancient times.[28] Kart probably is cognate with Indo-European gard and denotes people who live in a "fortified citadel".[29] Ancient Greeks (Homer, Herodotus, Strabo, Plutarch etc.) and Romans (Titus Livius, Cornelius Tacitus, etc.) referred to western Georgians as Colchians and eastern Georgians as Iberians.[30]

The term "Georgians" is derived from the country of Georgia. In the past, lore-based theories were given by the medieval French traveller Jacques de Vitry, who explained the name's origin by the popularity of St. George amongst Georgians,[31] while traveller Jean Chardin thought that "Georgia" came from Greek γεωργός ("tiller of the land"), as when the Greeks came into the region (in Colchis[28]) they encountered a developed agricultural society.[28]

However, as Prof. Alexander Mikaberidze adds, these explanations for the word Georgians/Georgia are rejected by the scholarly community, who point to the Persian word gurğ/gurğān ("wolf"[32]) as the root of the word.[33] Starting with the Persian word gurğ/gurğān, the word was later adopted in numerous other languages, including Slavic and West European languages.[28][34] This term itself might have been established through the ancient Iranian appellation of the near-Caspian region, which was referred to as Gorgan ("land of the wolves"[35]).[28]

Anthropology

The 18th-century German professor of medicine and member of the British Royal Society Johann Friedrich Blumenbach, widely regarded as one of the founders of the discipline of anthropology and the obsolete and disproven theory of biological race,[36] regarded Georgians as the most beautiful race of people.

Caucasian variety – I have taken the name of this variety from Mount Caucasus, both because its neighborhood, and especially its southern slope, produces the most beautiful race of men, I mean the Georgian; and because all physiological reasons converge to this, that in that region, if anywhere, it seems we ought with the greatest probability to place the autochthones (original members) of mankind.[37]

History

Most historians and scholars of Georgia as well as anthropologists, archaeologists, and linguists tend to agree that the ancestors of modern Georgians inhabited the southern Caucasus and northern Anatolia since the Neolithic period.[38] Scholars usually refer to them as Proto-Kartvelian (Proto-Georgians such as Colchians and Iberians) tribes.[39]

The Georgian people in antiquity have been known to the ancient Greeks and Romans as Colchians and Iberians.[40][41] East Georgian tribes of Tibarenians-Iberians formed their kingdom in 7th century BCE. However, western Georgian tribes (Colchian tribes) established the first Georgian state of Colchis (circa 1350 BCE) before the foundation of the Kingdom of Iberia in the east.[42][43] According to the numerous scholars of Georgia, the formations of these two early Georgian kingdoms of Colchis and Iberia, resulted in the consolidation and uniformity of the Georgian nation.[44]

According to the renowned scholar of the Caucasian studies Cyril Toumanoff, the Moschians also were one of the early proto-Georgian tribes which were integrated into the first early Georgian state of Iberia.[43] The ancient Jewish chronicle by Josephus mentions Georgians as Iberes who were also called Thobel (Tubal).[45] David Marshall Lang argued that the root Tibar gave rise to the form Iber that made the Greeks pick up the name Iberian in the end for the designation of the eastern Georgians.[46]

Diauehi in Assyrian sources and Taochi in Greek lived in the northeastern part of Anatolia. This ancient tribe is considered by many scholars as ancestors of the Georgians.[47] Modern Georgians still refer to this region, which now belongs to present-day Turkey, as Tao-Klarjeti, an ancient Georgian kingdom. Some people there still speak the Georgian language.[48]

Colchians in the ancient western Georgian polity of Colchis were another proto-Georgian tribe. They are first mentioned in the Assyrian annals of Tiglath-Pileser I and in the annals of Urartian king Sarduri II, and also included western Georgian tribe of the Meskhetians.[43][49]

Iberians, also known as Tiberians or Tiberanians, lived in the eastern Georgian kingdom of Iberia.[43]

Both Colchians and Iberians played an important role in the ethnic and cultural formation of the modern Georgian nation.[50][51]

According to the scholar of the Caucasian studies Cyril Toumanoff:

Colchis appears as the first Caucasian State to have achieved the coalescence of the newcomer, Colchis can be justly regarded as not a proto-Georgian, but a Georgian (West Georgian) kingdom ... It would seem natural to seek the beginnings of Georgian social history in Colchis, the earliest Georgian formation.[52]

Genetics

An FTDNA collection of Georgian Y-DNA suggests that Georgians have the highest percentage of Haplogroup G (39.9%) among the general population recorded in any country. Georgians' Y-DNA also belongs to Haplogroup J (32.5%), R1b (8.6%), L (5.4%), R1a (4.2%), I2 (3.8%) and other more minor haplogroups such as E, T and Q.[53]

Culture

Language and linguistic subdivisions

Georgian is the primary language for Georgians of all provenance, including those who speak other Kartvelian languages: Svans, Mingrelians and the Laz. The language known today as Georgian is a traditional language of the eastern part of the country which has spread to most of the present-day Georgia after the post-Christianization centralization in the first millennium CE. Today, Georgians regardless of their ancestral region use Georgian as their official language. The regional languages Svan and Mingrelian are languages of the west that were traditionally spoken in the pre-Christian Kingdom of Colchis, but later lost importance as the unified Kingdom of Georgia emerged. Their decline is largely due to the capital of the unified kingdom, Tbilisi, being in the eastern part of the country known as Kingdom of Iberia effectively making the language of the east an official language of the Georgian monarch.

All of these languages comprise the Kartvelian language family along with the related language of the Laz people, which has speakers in both Turkey and Georgia.

Georgian dialects include Imeretian, Racha-Lechkhumian, Gurian, Adjarian, Imerkhevian (in Turkey), Kartlian, Kakhetian, Ingilo (in Azerbaijan), Tush, Khevsur, Mokhevian, Pshavian, Fereydan dialect in Iran in Fereydunshahr and Fereydan, Mtiuletian, Meskhetian and Javakhetian dialect.

Religion

According to Orthodox tradition, Christianity was first preached in Georgia by the Apostles Simon and Andrew in the 1st century. It became the state religion of Kartli (Iberia) in 337.[54][55] At the same time, in the first centuries A.D., the cult of Mithras, pagan beliefs, and Zoroastrianism were commonly practiced in Georgia.[56] The conversion of Kartli to Christianity is credited to St. Nino of Cappadocia. Christianity gradually replaced all the former religions except Zoroastrianism, which become a second established religion in Iberia after the Peace of Acilisene in 378.[57] The conversion to Christianity eventually placed the Georgians permanently on the front line of conflict between the Islamic and Christian world. Georgians remained mostly Christian despite repeated invasions by Muslim powers, and long episodes of foreign domination.

As was true elsewhere, the Christian church in Georgia was crucial to the development of a written language, and most of the earliest written works were religious texts. Medieval Georgian culture was greatly influenced by Eastern Orthodoxy and the Georgian Orthodox Church, which promoted and often sponsored the creation of many works of religious devotion. These included churches and monasteries, works of art such as icons, and hagiographies of Georgian saints.

Today, 83.9% of the Georgian population, most of whom are ethnic Georgian, follow Eastern Orthodox Christianity.[58] A sizable Georgian Muslim population exists in Adjara. This autonomous Republic borders Turkey, and was part of the Ottoman Empire for a longer amount of time than other parts of the country. Those Georgian Muslims practice the Sunni Hanafi form of Islam. Islam has however declined in Adjara during the 20th century, due to Soviet anti-religious policies, cultural integration with the national Orthodox majority, and strong missionary efforts by the Georgian Orthodox Church.[59] Islam remains a dominant identity only in the eastern, rural parts of the Republic. In the early modern period, converted Georgian recruits were often used by the Persian and Ottoman Empires for elite military units such as the Mameluks, Qizilbash, and ghulams. The Georgians in Iran are all reportedly Shia Muslims today, while the Georgian minority in Turkey are mostly Sunni Muslim.

There is also a small number of Georgian Jews, tracing their ancestors to the Babylonian captivity.

In addition to traditional religious confessions, Georgia retains irreligious segments of society, as well as a significant portion of nominally religious individuals who do not actively practice their faith.[60]

Cuisine

The Georgian cuisine is specific to the country, but also contains some influences from other European culinary traditions, as well as those from the surrounding Western Asia. Each historical province of Georgia has its own distinct culinary tradition, such as Megrelian, Kakhetian, and Imeretian cuisines. In addition to various meat dishes, Georgian cuisine also offers a variety of vegetarian meals.

The importance of both food and drink to Georgian culture is best observed during a Caucasian feast, or supra, when a huge assortment of dishes is prepared, always accompanied by large amounts of wine, and dinner can last for hours. In a Georgian feast, the role of the tamada (toastmaster) is an important and honoured position.

In countries of the former Soviet Union, Georgian food is popular due to the immigration of Georgians to other Soviet republics, in particular Russia. In Russia all major cities have many Georgian restaurants and Russian restaurants often feature Georgian food items on their menu.[61]

Geographic subdivisions and subethnic groups

Geographical subdivisions

The Georgians have historically been classified into various subgroups based on the geographic region which their ancestors traditionally inhabited.

Even if a member of any of these subgroups moves to a different region, they will still be known by the name of their ancestral region. For example, if a Gurian moves to Tbilisi (part of the Kartli region) he will not automatically identify himself as Kartlian despite actually living in Kartli. This may, however, change if substantial amount of time passes. For example, there are some Mingrelians who have lived in the Imereti region for centuries and are now identified as Imeretian or Imeretian-Mingrelians.

Last names from mountainous eastern Georgian provinces (such as Kakheti, etc.) can be distinguished by the suffix –uri (ური), or –uli (ული). Most Svan last names typically end in –ani (ანი), Mingrelian in –ia (ია), -ua (უა), or -ava (ავა), and Laz in –shi (ში).

| Name | Name in Georgian | Geographical region | Dialect or Language |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adjarians | აჭარელი achareli | Adjara | Adjarian dialect |

| Gurians | გურული guruli | Guria | Gurian dialect |

| Imeretians | იმერელი imereli | Imereti | Imeretian dialect |

| Javakhians | ჯავახი javakhi | Javakheti | Javakhian dialect |

| Kakhetians | კახელი kakheli | Kakheti | Kakhetian dialect |

| Kartlians | ქართლელი kartleli | Kartli | Kartlian dialect |

| Khevsurians | ხევსური khevsuri | Khevsureti | Khevsurian dialect |

| Lechkhumians | ლეჩხუმელი lechkhumeli | Lechkhumi | Lechkhumian dialect |

| Mingrelians | მეგრელი megreli | Samegrelo | Mingrelian language |

| Meskhetians | მესხი meskhi | Meskheti (Samtskhe) | Meskhian dialect |

| Mokhevians | მოხევე mokheve | Khevi | Mokhevian dialect |

| Pshavians | ფშაველი pshaveli | Pshavi | Pshavian dialect |

| Rachians | რაჭველი rachveli | Racha | Rachian dialect |

| Svans | სვანი svani | Svaneti | Svan language |

| Tushs | თუში tushi | Tusheti | Tushetian dialect |

The 1897 Russian census (which accounted people by language), had Imeretian, Svan and Mingrelian languages separate from Georgian.[62] During the 1926 Soviet census, Svans and Mingrelians were accounted separately from Georgian.[63] Svan and Mingrelian languages are both Kartvelian languages and are closely related to the national Georgian language.

Outside modern Georgia

Laz people also may be considered Georgian based on their geographic location and religion. According to the London School of Economics' anthropologist Mathijs Pelkmans,[64] Lazs residing in Georgia frequently identify themselves as "first-class Georgians" to show pride, while considering their Muslim counterparts in Turkey as "Turkified Lazs".[65]

| Subethnic groups | Georgian name | Settlement area | Language (dialect) |

Number | Difference(s) from mainstream Georgians (other than location) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laz people | ლაზი lazi | Chaneti (Turkey) | Laz language | 1 million | Religion: Muslim majority, Orthodox Minority |

| Fereydani | ფერეიდნელი pereidneli | Fereydan (Iran) | Pereidnuli dialect | 100,000 +[6] | Religion: Muslim[6] |

| Chveneburi | ჩვენებური chveneburi | Black Sea Region (Turkey) | Georgian language | 91,000[66]–1,000,000[67] | Religion: Muslim[66] |

| Ingiloy people | ინგილო ingilo | Saingilo Hereti Zaqatala District (Azerbaijan) | Ingiloan dialect | 12,000 | Religion: Muslim majority,[68] Orthodox minority[69] |

| Imerkhevians

(Shavshians) |

შავში shavshi | Shavsheti (Turkey) | Imerkhevian dialect |

|

Religion: Muslim majority. |

| Klarjians | კლარჯი klarji | Klarjeti (Turkey) | Imerkhevian dialect |

|

|

Extinct Georgian subdivisions

Throughout history Georgia also has extinct Georgian subdivisions

| Name | Name in Georgian | Geographical location | Dialect or language |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dvals | დვალი dvali | Georgia (Racha and Khevi regions) and Russia (North Ossetia) | Dval dialect |

See also

References

- Ethnic Georgians are 86.8% of Georgia's current population of 3,713,800. Data without the occupied territories of Georgia.

However, such explanations are rejected by the scholarly community, who point to the Persian gurğ/gurğān as the root of the word (...)

The Russian designation of Georgia (Gruziya) also derives from the Persian gurg.

About 91,000 Muslim Georgians living in Turkey.

- Friedrich, Paul (1994). Encyclopedia of World Cultures: Russia and Eurasia, China (1. publ. ed.). Boston, Massachusetts: G.K. Hall. p. 150. ISBN 9780816118106.

A part of the Ingilo population still retains the (Orthodox) Christian faith, but another, larger segment adheres to the Sunni sect of Islam.

Bibliography

- W.E.D. Allen (1970) Russian Embassies to the Georgian Kings, 1589–1605, Hakluyt Society, ISBN 978-1-4094-4599-9 (hbk)

- Eastmond, Anthony (2010), Royal Imagery in Medieval Georgia, Penn State Press

- Suny, R. G. (1994), The Making of the Georgian Nation, Indiana University Press, ISBN 978-0253209153

- Lang, D. M. (1966), The Georgians, Thames & Hudson

- Rayfield, D. (2013), Edge of Empires: A History of Georgia, Reaktion Books, ISBN 978-1789140590

- Rapp, S. H. Jr. (2016) The Sasanian World Through Georgian Eyes, Caucasia and the Iranian Commonwealth in Late Antique Georgian Literature, Sam Houston State University, USA, Routledge

- Toumanoff, C. (1963) Studies in Christian Caucasian History, Georgetown University Press

- Ancient peoples of Georgia (country)

- Ethnic groups in Azerbaijan

- Ethnic groups in Georgia (country)

- Ethnic groups in Greece

- Ethnic groups in Iran

- Ethnic groups in Russia

- Ethnic groups in the Middle East

- Ethnic groups in Turkey

- Indigenous peoples of Europe

- Indigenous peoples of Western Asia

- People from Georgia (country)

- People from Georgia (country) by ethnic or national origin

- Peoples of the Caucasus

- Society of Georgia (country)

- Tribes in Greco-Roman historiography

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Georgians

Georgian scripts

| Georgian | |

|---|---|

damts'erloba "script" in Mkhedruli | |

| Script type | |

Time period | AD 430[1] – present |

| Direction | left-to-right |

| Languages | |

| Related scripts | |

Parent systems | Uncertain, alphabetical order modelled on Greek

|

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Geor (240), Georgian (Mkhedruli and Mtavruli) – Georgian (Mkhedruli) Geok, 241 – Khutsuri (Asomtavruli and Nuskhuri) |

| Unicode | |

Unicode alias | Georgian |

| Living culture of three writing systems of the Georgian alphabet | |

|---|---|

| |

| Country | Georgia |

| Reference | 01205 |

| Region | |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 2016 (11 session) |

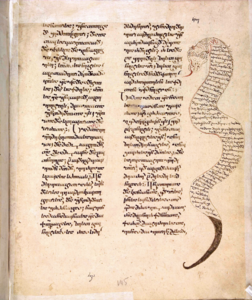

The Georgian scripts are the three writing systems used to write the Georgian language: Asomtavruli, Nuskhuri and Mkhedruli. Although the systems differ in appearance, their letters share the same names and alphabetical order and are written horizontally from left to right. Of the three scripts, Mkhedruli, once the civilian royal script of the Kingdom of Georgia and mostly used for the royal charters, is now the standard script for modern Georgian and its related Kartvelian languages, whereas Asomtavruli and Nuskhuri are used only by the Georgian Orthodox Church, in ceremonial religious texts and iconography.[2]

Georgian scripts are unique in their appearance and their exact origin has never been established; however, in strictly structural terms, their alphabetical order largely corresponds to the Greek alphabet, with the exception of letters denoting uniquely Georgian sounds, which are grouped at the end.[3][4] Originally consisting of 38 letters,[5] Georgian is presently written in a 33-letter alphabet, as five letters are obsolete. The number of Georgian letters used in other Kartvelian languages varies. Mingrelian uses 36: thirty-three that are current Georgian letters, one obsolete Georgian letter, and two additional letters specific to Mingrelian and Svan. Laz uses the same 33 current Georgian letters as Mingrelian plus that same obsolete letter and a letter borrowed from Greek for a total of 35. The fourth Kartvelian language, Svan, is not commonly written, but when it is, it uses Georgian letters as utilized in Mingrelian, with an additional obsolete Georgian letter and sometimes supplemented by diacritics for its many vowels.[2][6]

The "living culture of three writing systems of the Georgian alphabet" was granted the national status of intangible cultural heritage in Georgia in 2015[7] and inscribed on the UNESCO Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2016.[8]

Origins

The origin of the Georgian script is poorly known, and no full agreement exists among Georgian and foreign scholars as to its date of creation, who designed the script, and the main influences on that process.

The first attested version of the script is Asomtavruli, which dates back to the 5th century; the other scripts were formed in the following centuries. Most scholars link the creation of the Georgian script to the process of Christianization of Iberia (not to be confused with the Iberian Peninsula), a core Georgian kingdom of Kartli.[9] The alphabet was therefore most probably created between the conversion of Iberia under King Mirian III (326 or 337) and the Bir el Qutt inscriptions of 430,.[9][10] It was first used for translation of the Bible and other Christian literature into Georgian, by monks in Georgia and Palestine.[4] Professor Levan Chilashvili's dating of fragmented Asomtavruli inscriptions, discovered by him at the ruined town of Nekresi, in Georgia's easternmost province of Kakheti, in the 1980s, to the 1st or 2nd century has not been accepted.[11]

A Georgian tradition first attested in the medieval chronicle Lives of the Kings of Kartli (ca. 800),[4] assigns a much earlier, pre-Christian origin to the Georgian alphabet, and names King Pharnavaz I (3rd century BC) as its inventor. This account is now considered legendary, and is rejected by scholarly consensus, as no archaeological confirmation has been found.[4][12][13] Rapp considers the tradition to be an attempt by the Georgian Church to rebut the earlier tradition that the alphabet was invented by the Armenian scholar Mesrop Mashtots, and is a Georgian application of an Iranian model in which primordial kings are credited with the creation of basic social institutions.[14] Georgian linguist Tamaz Gamkrelidze offers an alternative interpretation of the tradition, in the pre-Christian use of foreign scripts (alloglottography in the Aramaic alphabet) to write down Georgian texts.[15]

Another point of contention among scholars is the role played by Armenian clerics in that process. According to medieval Armenian sources and a number of scholars, Mesrop Mashtots, generally acknowledged as the creator of the Armenian alphabet, also created the Georgian and Caucasian Albanian alphabets. This tradition originates in the works of Koryun, a fifth-century historian and biographer of Mashtots,[16] and has been quoted by Donald Rayfield and James R. Russell,[17][18] but has been rejected by Georgian scholarship and some Western scholars who judge the passage in Koryun unreliable or even a later interpolation.[4] In his study on the history of the invention of the Armenian alphabet and the life of Mashtots, the Armenian linguist Hrachia Acharian strongly defended Koryun as a reliable source and rejected criticisms of his accounts on the invention of the Georgian script by Mashtots.[19] Acharian dated the invention to 408, four years after Mashtots created the Armenian alphabet (he dated the latter event to 404).[20] Some Western scholars quote Koryun's claims without taking a stance on its validity[21][22] or concede that Armenian clerics, if not Mashtots himself, must have played a role in the creation of the Georgian script.[4][13][23]

Another controversy regards the main influences at play in the Georgian alphabet, as scholars have debated whether it was inspired more by the Greek alphabet, or by Semitic alphabets such as Aramaic.[15] Recent historiography focuses on greater similarities with the Greek alphabet than in the other Caucasian writing systems, most notably the order and numeric value of letters.[3][4] Some scholars have also suggested certain pre-Christian Georgian cultural symbols or clan markers as a possible inspiration for particular letters.[24]

Asomtavruli

Asomtavruli (Georgian: ასომთავრული; Georgian pronunciation: [ɑsɔmtʰɑvɾuli]) is the oldest Georgian script. The name Asomtavruli means "capital letters", from aso (ასო) "letter" and mtavari (მთავარი) "principal/head". It is also known as Mrgvlovani (Georgian: მრგვლოვანი) "rounded", from mrgvali (მრგვალი) "round", so named because of its round letter shapes. Despite its name, this "capital" script is unicameral.[25]

The oldest Asomtavruli inscriptions found so far date from the 5th century[26] and are Bir el Qutt[27] and the Bolnisi inscriptions.[28]

From the 9th century, Nuskhuri script started becoming dominant, and the role of Asomtavruli was reduced. However, epigraphic monuments of the 10th to 18th centuries continued to be written in Asomtavruli script. Asomtavruli in this later period became more decorative. In the majority of 9th-century Georgian manuscripts which were written in Nuskhuri script, Asomtavruli was used for titles and the first letters of chapters.[29] However, some manuscripts written completely in Asomtavruli can be found until the 11th century.[30]

Form of Asomtavruli letters

In early Asomtavruli, the letters are of equal height. Georgian historian and philologist Pavle Ingorokva believes that the direction of Asomtavruli, like that of Greek, was initially boustrophedon, though the direction of the earliest surviving texts is from left to the right.[31]

In most Asomtavruli letters, straight lines are horizontal or vertical and meet at right angles. The only letter with acute angles is Ⴟ (jani). There have been various attempts to explain this exception. Georgian linguist and art historian Helen Machavariani believes jani derives from a monogram of Christ, composed of Ⴈ (ini) and Ⴕ (kani).[32] According to Georgian scholar Ramaz Pataridze, the cross-like shape of letter jani indicates the end of the alphabet, and has the same function as the similarly shaped Phoenician letter taw (![]() ), Greek chi (Χ), and Latin X,[33] though these letters do not have that function in Phoenician, Greek, or Latin.

), Greek chi (Χ), and Latin X,[33] though these letters do not have that function in Phoenician, Greek, or Latin.

Coins of Queen Tamar of Georgia and King George IV of Georgia minted using Asomtavruli script, 1200–1210 AD.

From the 7th century, the forms of some letters began to change. The equal height of the letters was abandoned, with letters acquiring ascenders and descenders.[34][35]

| Ⴀ ani |

Ⴁ bani |

Ⴂ gani |

Ⴃ doni |

Ⴄ eni |

Ⴅ vini |

Ⴆ zeni |

Ⴡ he |

Ⴇ tani |

Ⴈ ini |

Ⴉ kʼani |

Ⴊ lasi |

Ⴋ mani |

Ⴌ nari |

Ⴢ hie |

Ⴍ oni |

Ⴎ pʼari |

Ⴏ zhani |

Ⴐ rae |

| Ⴑ sani |

Ⴒ tʼari |

Ⴣ vie |

ႭჃ Ⴓ uni |

Ⴔ pari |

Ⴕ kani |

Ⴖ ghani |

Ⴗ qʼari |

Ⴘ shini |

Ⴙ chini |

Ⴚ tsani |

Ⴛ dzili |

Ⴜ ts'ili |

Ⴝ ch'ari |

Ⴞ khani |

Ⴤ qari |

Ⴟ jani |

Ⴠ hae |

Ⴥ hoe |

Asomtavruli illumination

In Nuskhuri manuscripts, Asomtavruli are used for titles and illuminated capitals. The latter were used at the beginnings of paragraphs which started new sections of text. In the early stages of the development of Nuskhuri texts, Asomtavruli letters were not elaborate and were distinguished principally by size and sometimes by being written in cinnabar ink. Later, from the 10th century, the letters were illuminated. The style of Asomtavruli capitals can be used to identify the era of a text. For example, in the Georgian manuscripts of the Byzantine era, when the styles of the Byzantine Empire influenced Kingdom of Georgia, capitals were illuminated with images of birds and other animals.[36]

From the 11th-century "limb-flowery", "limb-arrowy" and "limb-spotty" decorative forms of Asomtavruli are developed. The first two are found in 11th- and 12th-century monuments, whereas the third one is used until the 18th century.[37][38]

Importance was attached also to the colour of the ink itself.[39]

Asomtavruli letter Ⴃ (doni) is often written with decoration effects of fish and birds.[40]

The "Curly" decorative form of Asomtavruli is also used where the letters are wattled or intermingled on each other, or the smaller letters are written inside other letters. It was mostly used for the headlines of the manuscripts or the books, although there are complete inscriptions which were written in the Asomtavruli "Curly" form only.[41]

Handwriting of Asomtavruli

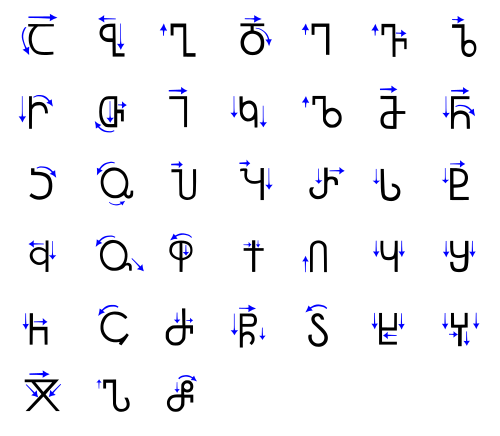

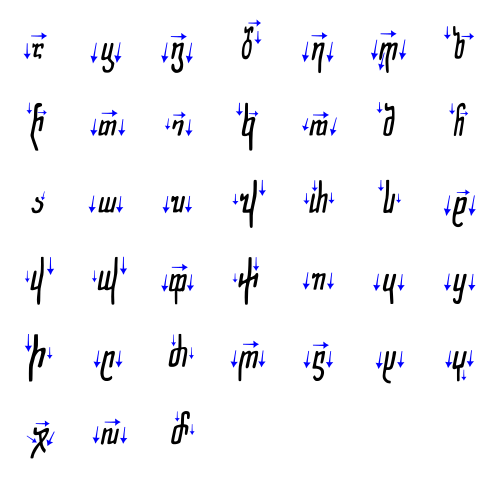

The following table shows the stroke order and direction of each Asomtavruli letter:[42]

Nuskhuri

Nuskhuri (Georgian: ნუსხური; Georgian pronunciation: [nusχuɾi]) is the second Georgian script. The name nuskhuri comes from nuskha (ნუსხა), meaning "inventory" or "schedule". Nuskhuri was soon augmented with Asomtavruli illuminated capitals in religious manuscripts. The combination is called Khutsuri (Georgian: ხუცური, "clerical", from khutsesi (ხუცესი "cleric"), and it was principally used in hagiography.[43]

Nuskhuri first appeared in the 9th century as a graphic variant of Asomtavruli.[9] The oldest inscription is found in the Ateni Sioni Church and dates to 835 AD.[44] The oldest surviving Nuskhuri manuscripts date to 864 AD.[45] Nuskhuri becomes dominant over Asomtavruli from the 10th century.[43]

Form of Nuskhuri letters

Nuskhuri letters vary in height, with ascenders and descenders, and are slanted to the right. Letters have an angular shape, with a noticeable tendency to simplify the shapes they had in Asomtavruli. This enabled faster writing of manuscripts.[46]

Asomtavruli letters ⴍ (oni) and ⴣ (vie). A ligature of these letters produced a new letter in Nuskhuri, ⴓ uni.

| ⴀ ani |

ⴁ bani |

ⴂ gani |

ⴃ doni |

ⴄ eni |

ⴅ vini |

ⴆ zeni |

ⴡ he |

ⴇ tani |

ⴈ ini |

ⴉ kʼani |

ⴊ lasi |

ⴋ mani |

ⴌ nari |

ⴢ hie |

ⴍ oni |

ⴎ pʼari |

ⴏ zhani |

ⴐ rae |

| ⴑ sani |

ⴒ tʼari |

ⴣ vie |

ⴍⴣ ⴓ uni |

ⴔ pari |

ⴕ kani |

ⴖ ghani |

ⴗ qʼari |

ⴘ shini |

ⴙ chini |

ⴚ tsani |

ⴛ dzili |

ⴜ tsʼili |

ⴝ chʼari |

ⴞ khani |

ⴤ qari |

ⴟ jani |

ⴠ hae |

ⴥ hoe |

- Note: Without proper font support, you may see question marks, boxes or other symbols instead of Nuskhuri letters.

Handwriting of Nuskhuri

The following table shows the stroke order and direction of each Nuskhuri letter:[47]

Use of Asomtavruli and Nuskhuri today

Asomtavruli is used intensively in iconography, murals, and exterior design, especially in stone engravings.[48] Georgian linguist Akaki Shanidze made an attempt in the 1950s to introduce Asomtavruli into the Mkhedruli script as capital letters to begin sentences, as in the Latin script, but it did not catch on.[49] Asomtavruli and Nuskhuri are officially used by the Georgian Orthodox Church alongside Mkhedruli. Patriarch Ilia II of Georgia called on people to use all three Georgian scripts.[50]

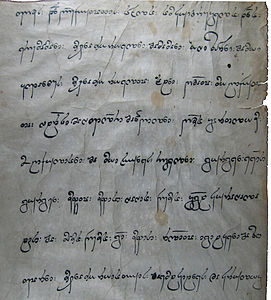

Mkhedruli

Mkhedruli (Georgian: მხედრული; Georgian pronunciation: [mχɛdɾuli]) is the third and current Georgian script. Mkhedruli, literally meaning "cavalry" or "military", derives from mkhedari (მხედარი) meaning "horseman", "knight", "warrior"[51] and "cavalier".[52]

Mkhedruli is bicameral, with capital letters that are called Mkhedruli Mtavruli (მხედრული მთავრული) or simply Mtavruli (მთავრული; Georgian pronunciation: [mtʰɑvɾuli]). Nowadays, Mkhedruli Mtavruli is only used in all-caps text in titles or to emphasize a word, though in the late 19th and early 20th centuries it was occasionally used, as in Latin and Cyrillic scripts, to capitalize proper nouns or the first word of a sentence. Contemporary Georgian script does not recognize capital letters and their usage has become decorative.[53]

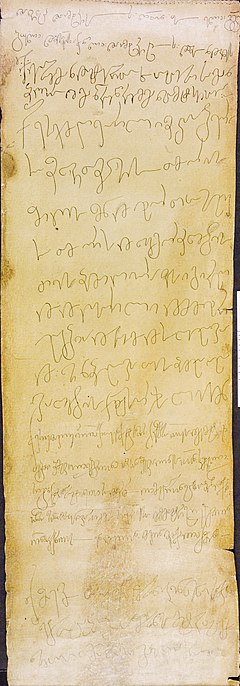

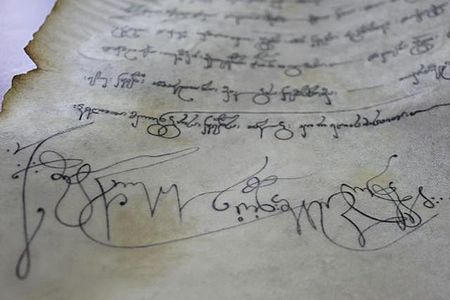

Mkhedruli first appears in the 10th century. The oldest Mkhedruli inscription is found in Ateni Sioni Church dating back to 982 AD. The second oldest Mkhedruli-written text is found in the 11th-century royal charters of King Bagrat IV of Georgia. Mkhedruli was mostly used then in the Kingdom of Georgia for the royal charters, historical documents, manuscripts and inscriptions.[54] Mkhedruli was used for non-religious purposes only and represented the "civil", "royal" and "secular" script.[55][56]

Mkhedruli became more and more dominant over the two other scripts, though Khutsuri (Nuskhuri with Asomtavruli) was used until the 19th century. Mkhedruli became the universal writing Georgian system outside of the Church in the 19th century with the establishment and development of printed Georgian fonts.[57]

Form of Mkhedruli letters

Mkhedruli inscriptions of the 10th and 11th centuries are characterized in rounding of angular shapes of Nuskhuri letters and making the complete outlines in all of its letters. Mkhedruli letters are written in the four-linear system, similar to Nuskhuri. Mkhedruli becomes more round and free in writing. It breaks the strict frame of the previous two alphabets, Asomtavruli and Nuskhuri. Mkhedruli letters begin to get coupled and more free calligraphy develops.[58]

Example of one of the oldest Mkhedruli-written texts found in the royal charter of King Bagrat IV of Georgia, 11th century.

Modern Georgian alphabet

The modern Georgian alphabet consists of 33 letters:

| ა ani |

ბ bani |

გ gani |

დ doni |

ე eni |

ვ vini |

ზ zeni |

თ tani |

ი ini |

კ k'ani |

ლ lasi |

| მ mani |

ნ nari |

ო oni |

პ p'ari |

ჟ zhani |

რ rae |

ს sani |

ტ t'ari |

უ uni |

ფ pari |

ქ kani |

| ღ ghani |

ყ q'ari |

შ shini |

ჩ chini |

ც tsani |

ძ dzili |

წ ts'ili |

ჭ ch'ari |

ხ khani |

ჯ jani |

ჰ hae |

Letters removed from the Georgian alphabet

The Society for the Spreading of Literacy among Georgians, founded by Prince Ilia Chavchavadze in 1879, discarded five letters from the Georgian alphabet that had become redundant:[25]

| ჱ he |

ჲ hie |

ჳ vie |

ჴ qari |

ჵ hoe |

- ჱ (he) /eɪ/, Svan /eː/, sometimes called "ei"[59] or "e-merve" ("eighth e"),[60] was equivalent to ეჲ ey, as in ქრისტჱ ~ ქრისტეჲ kristʼey 'Christ'.

- ჲ (hie) /je/, also called yota,[60] appeared instead of ი (ini) after a vowel, but came to have the same pronunciation as ი (ini) and was replaced by it. Thus, ქრისტჱ ~ ქრისტეჲ kristʼey "Christ" is now written ქრისტე kristʼe.

- ჳ (vie) /uɪ/, Svan /w/[60] came to be pronounced the same as ვი vi and was replaced by that sequence, as in სხჳსი > სხვისი skhvisi "others'".

- ჴ (qari, hari) /q⁽ʰ⁾/[60] came to be pronounced the same as ხ (khani), and was replaced by it. e.g. ჴელმწიფე qelmtsʼipe became ხელმწიფე khelmtsʼipe "sovereign".

- ჵ (hoe) /oː/[60] was used for the interjection hoi! and is now spelled ჰოი. Also used in Bats for the /ʕ/ or /ɦ/ sound.

All but ჵ (hoe) continue to be used in the Svan alphabet; ჲ (hie) is used in the Mingrelian and Laz alphabets as well, for the y-sound /j/. Several others were used for Abkhaz and Ossetian in the short time they were written in Mkhedruli script.

Letters added to other alphabets

Mkhedruli has been adapted to languages besides Georgian. Some of these alphabets retained letters obsolete in Georgian, while others required additional letters:

| ჶ fi |

ჷ shva |

ჸ elifi |

ჹ turned gani |

ჺ aini |

ჼ modifier letter nar |

ჽ aen |

ჾ hard sign |

ჿ labial sign |

- ჶ (fi "phi") is used in Laz and Svan, and formerly in Ossetian and Abkhazian.[2] It derives from the Greek letter Φ (phi).

- ჷ (shva "schwa"), also called yn, is used for the schwa sound in Svan and Mingrelian, and formerly in Ossetian and Abkhazian.[2]

- ჸ (elifi "alif") is used in for the glottal stop in Svan and Mingrelian.[2] It is a reversed ⟨ყ⟩ (q'ari).

- ჹ (turned gani) was once used for [ɢ] in evangelical literature in Dagestanian languages.[2]

- ჼ (modifier nar) is used in Bats. It nasalizes the preceding vowel.[61]

- ჺ (aini "ain") is occasionally used for [ʕ] in Bats.[2] It derives from the Arabic letter ⟨ع⟩ (ʿayn)

- ჽ (aen) was used in the Ossetian language when it was written in the Georgian script. It was pronounced [ə].[62]

- ჾ (hard sign) was used in Abkhaz for velarization of the preceding consonant.[63]

- ჿ (labial sign) was used in Abkhaz for labialization of the preceding consonant.[63]

Handwriting of Mkhedruli

The following table shows the stroke order and direction of each Mkhedruli letter:[64][65][66]

ზ, ო, and ხ (zeni, oni, khani) are almost always written without the small tick at the end, while the handwritten form of ჯ (jani) often uses a vertical line, ![]() (sometimes with a taller ascender, or with a diagonal cross bar); even

when it is written at a diagonal, the cross-bar is generally shorter

than in print.

(sometimes with a taller ascender, or with a diagonal cross bar); even

when it is written at a diagonal, the cross-bar is generally shorter

than in print.

- Only four letters are x-height, with neither ascenders nor descenders: ა, თ, ი, ო.

- Thirteen have ascenders, like b or d in English: ბ, ზ, მ, ნ, პ, რ, ს, შ, ჩ, ძ, წ, ხ, ჰ

- An equal number have descenders, like p or q in English: გ, დ, ე, ვ, კ, ლ, ჟ, ტ, უ, ფ, ღ, ყ, ც

- Three letters have both ascenders and descenders, like þ in Old English: ქ, ჭ, and (in handwriting) ჯ. წ has both ascender and descender in print, and sometimes in handwriting.

Variation

There is individual and stylistic variation in many of the letters. For example, the top circle of ზ (zeni) and the top stroke of რ (rae) may go in the other direction than shown in the chart (that is, counter-clockwise starting at 3 o'clock, and upwards – see the external-link section for videos of people writing).

Other common variants:

- გ (gani) may be written like ვ (vini) with a closed loop at the bottom.

- დ (doni) is frequently written with a simple loop at top,

.

. - კ, ც, and ძ (k'ani, tsani, dzili) are generally written with straight, vertical lines at the top, so that for example ც (tsani) resembles a U with a dimple in the right side.

- ლ (lasi) is frequently written with a single arc,

.

Even when all three are written, they're generally not all the same

size, as they are in print, but rather riding on one wide arc like two

dimples in it.

.

Even when all three are written, they're generally not all the same

size, as they are in print, but rather riding on one wide arc like two

dimples in it. - Rarely, ო (oni) is written as a right angle,

.

. - რ (rae) is frequently written with one arc,

, like a Latin ⟨h⟩.

, like a Latin ⟨h⟩. - ტ (t'ari) often has a small circle with a tail hanging into the bowl, rather than two small circles as in print, or as an O with a straight vertical line intersecting the top. It may also be rotated a bit clockwise, with the small circles further to the right and not as close to the top.

- წ (ts'ili) is generally written with a round bowl at the bottom,

. Another variation features a triangular bowl.

. Another variation features a triangular bowl. - ჭ (ch'ari) may be written without the hook at the top, and often with a completely straight vertical line.

- ჱ (he) may be written without the loop, like a conflation of ს and ჰ.

- ჯ (jani) is sometimes written so that it looks like a hooked version of the Latin "X"

Similar letters

Several letters are similar and may be confused at first, especially in handwriting.

- For ვ (vini) and კ (k'ani), the critical difference is whether the top is a full arc or a (more-or-less) vertical line.

- For ვ (vini) and გ (gani), it is whether the bottom is an open curve or closed (a loop). The same is true of უ (uni) and შ (shini); in handwriting, the tops may look the same. Similarly ს (sani) and ხ (khani).

- For კ (k'ani) and პ (p'ari), the crucial difference is whether the letter is written below or above x-height, and whether it's written top-down or bottom-up.

- ძ (dzili) is written with a vertical top.

Ligatures, abbreviations and calligraphy

| Calligraphy |

|---|

Asomtavruli is often highly stylized and writers readily formed ligatures, intertwined letters, and placed letters within letters or other such monograms.[67]

Nuskhuri, like Asomtavruli, is also often highly stylized. Writers readily formed ligatures and abbreviations for nomina sacra, including diacritics called karagma, which resemble titla. Because writing materials such as vellum were scarce and therefore precious, abbreviating was a practical measure widespread in manuscripts and hagiography by the 11th century.[68]

Mkhedruli, in the 11th to 17th centuries also came to employ digraphs to the point that they were obligatory, requiring adherence to a complex system.[69]

Typefaces

Georgian scripts come in only a single typeface, though word processors can apply automatic ("fake")[70] oblique and bold formatting to Georgian text. Traditionally, Asomtavruli was used for chapter or section titles, where Latin script might use bold or italic type.

Punctuation

In Asomtavruli and Nuskhuri punctuation, various combinations of dots were used as word dividers and to separate phrases, clauses, and paragraphs. In monumental inscriptions and manuscripts of 5th to 10th centuries, these were written as dashes, like −, = and =−. In the 10th century, clusters of one (·), two (:), three (჻) and six (჻჻) dots (later sometimes small circles) were introduced by Ephrem Mtsire to indicate increasing breaks in the text. One dot indicated a "minor stop" (presumably a simple word break), two dots marked or separated "special words", three dots for a "bigger stop" (such as the appositive name and title "the sovereign Alexander", below, or the title of the Gospel of Matthew, above), and six dots were to indicate the end of the sentence. Starting in the 11th century, marks resembling the apostrophe and comma came into use. An apostrophe was used to mark an interrogative word, and a comma appeared at the end of an interrogative sentence. From the 12th century on, these were replaced with the semicolon (the Greek question mark). In the 18th century, Patriarch Anton I of Georgia reformed the system again, with commas, single dots, and double dots used to mark "complete", "incomplete", and "final" sentences, respectively.[71] For the most part, Georgian today uses the punctuation as in international usage of the Latin script.[72]

ჴლმწიფე ჻ ალექსანდრე

"The sovereign Alexander"

Summary

This table lists the three scripts in parallel columns, including the letters that are now obsolete in all alphabets (shown with a blue background), obsolete in Georgian but still used in other alphabets (green background), or additional letters in languages other than Georgian (pink background). The "national" transliteration is the system used by the Georgian government, whereas "Laz" is the Latin Laz alphabet used in Turkey. The table also shows the traditional numeric values of the letters.[73]

| Letters | Unicode (mkhedruli) |

Name | IPA | Transcriptions | Numeric value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| asomtavruli | nuskhuri | mkhedruli | mtavruli | National | ISO 9984 | BGN | Laz | ||||

| Ⴀ | ⴀ | ა | Ა | U+10D0 | ani | /ɑ/, Svan /a, æ/ | A a | A a | A a | A a | 1 |

| Ⴁ | ⴁ | ბ | Ბ | U+10D1 | bani | /b/ | B b | B b | B b | B b | 2 |

| Ⴂ | ⴂ | გ | Გ | U+10D2 | gani | /ɡ/ | G g | G g | G g | G g | 3 |

| Ⴃ | ⴃ | დ | Დ | U+10D3 | doni | /d/ | D d | D d | D d | D d | 4 |

| Ⴄ | ⴄ | ე | Ე | U+10D4 | eni | /ɛ/ | E e | E e | E e | E e | 5 |

| Ⴅ | ⴅ | ვ | Ვ | U+10D5 | vini | /v/ | V v | V v | V v | V v | 6 |

| Ⴆ | ⴆ | ზ | Ზ | U+10D6 | zeni | /z/ | Z z | Z z | Z z | Z z | 7 |

| Ⴡ | ⴡ | ჱ | Ჱ | U+10F1 | he | /eɪ/, Svan /eː/ | — | Ē ē | Ey ey | — | 8 |

| Ⴇ | ⴇ | თ | Თ | U+10D7 | tani | /t⁽ʰ⁾/ | T t | Tʼ tʼ | Tʼ tʼ | T t | 9 |

| Ⴈ | ⴈ | ი | Ი | U+10D8 | ini | /i/ | I i | I i | I i | I i | 10 |

| Ⴉ | ⴉ | კ | Კ | U+10D9 | kʼani | /kʼ/ | Kʼ kʼ | K k | K k | Ǩ ǩ | 20 |

| Ⴊ | ⴊ | ლ | Ლ | U+10DA | lasi | /l/ | L l | L l | L l | L l | 30 |

| Ⴋ | ⴋ | მ | Მ | U+10DB | mani | /m/ | M m | M m | M m | M m | 40 |

| Ⴌ | ⴌ | ნ | Ნ | U+10DC | nari | /n/ | N n | N n | N n | N n | 50 |

| Ⴢ | ⴢ | ჲ | Ჲ | U+10F2 | hie | /je/, Mingrelian, Laz, & Svan /j/ | — | Y y | J j | Y y | 60 |

| Ⴍ | ⴍ | ო | Ო | U+10DD | oni | /ɔ/, Svan /ɔ, œ/ | O o | O o | O o | O o | 70 |

| Ⴎ | ⴎ | პ | Პ | U+10DE | pʼari | /pʼ/ | Pʼ pʼ | P p | P p | P̌ p̌ | 80 |

| Ⴏ | ⴏ | ჟ | Ჟ | U+10DF | zhani | /ʒ/ | Zh zh | Ž ž | Zh zh | J j | 90 |

| Ⴐ | ⴐ | რ | Რ | U+10E0 | rae | /r/ | R r | R r | R r | R r | 100 |

| Ⴑ | ⴑ | ს | Ს | U+10E1 | sani | /s/ | S s | S s | S s | S s | 200 |

| Ⴒ | ⴒ | ტ | Ტ | U+10E2 | tʼari | /tʼ/ | Tʼ tʼ | T t | T t | Ť t̆ | 300 |

| Ⴣ | ⴣ | ჳ | Ჳ | U+10F3 | vie | /uɪ/, Svan /w/ | — | W w | — | — | 400[74] |

| Ⴓ | ⴓ | უ | Უ | U+10E3 | uni | /u/, Svan /u, y/ | U u | U u | U u | U u | 400[74] |

| Ⴧ | ⴧ | ჷ | Ჷ | U+10F7 | yn, schva | Mingrelian, Laz & Svan /ə/ | — | — | — | — | — |

| Ⴔ | ⴔ | ფ | Ფ | U+10E4 | pari | /p⁽ʰ⁾/ | P p | Pʼ pʼ | Pʼ pʼ | P p | 500 |

| Ⴕ | ⴕ | ქ | Ქ | U+10E5 | kani | /k⁽ʰ⁾/ | K k | Kʼ kʼ | Kʼ kʼ | K k | 600 |

| Ⴖ | ⴖ | ღ | Ღ | U+10E6 | ghani | /ɣ/ | Gh gh | Ḡ ḡ | Gh gh | Ğ ğ | 700 |

| Ⴗ | ⴗ | ყ | Ყ | U+10E7 | qʼari | /qʼ/ | Qʼ qʼ | Q q | Q q | Q q | 800 |

| — | — | ჸ | Ჸ | U+10F8 | elif | Mingrelian & Svan /ʔ/ | — | — | — | — | — |

| Ⴘ | ⴘ | შ | Შ | U+10E8 | shini | /ʃ/ | Sh sh | Š š | Sh sh | Ş ş | 900 |

| Ⴙ | ⴙ | ჩ | Ჩ | U+10E9 | chini | /tʃ⁽ʰ⁾/ | Ch ch | Čʼ čʼ | Chʼ chʼ | Ç ç | 1000 |

| Ⴚ | ⴚ | ც | Ც | U+10EA | tsani | /ts⁽ʰ⁾/ | Ts ts | Cʼ cʼ | Tsʼ tsʼ | Ʒ ʒ | 2000 |

| Ⴛ | ⴛ | ძ | Ძ | U+10EB | dzili | /dz/ | Dz dz | J j | Dz dz | Ž ž | 3000 |

| Ⴜ | ⴜ | წ | Წ | U+10EC | tsʼili | /tsʼ/ | Tsʼ tsʼ | C c | Ts ts | Ǯ ǯ | 4000 |

| Ⴝ | ⴝ | ჭ | Ჭ | U+10ED | chʼari | /tʃʼ/ | Chʼ chʼ | Č č | Ch ch | Ç̌ ç̌ | 5000 |

| Ⴞ | ⴞ | ხ | Ხ | U+10EE | khani | /χ/ | Kh kh | X x | Kh kh | X x | 6000 |

| Ⴤ | ⴤ | ჴ | Ჴ | U+10F4 | qari, hari | /q⁽ʰ⁾/ | — | H̱ ẖ | qʼ | — | 7000 |

| Ⴟ | ⴟ | ჯ | Ჯ | U+10EF | jani | /dʒ/ | J j | J̌ ǰ | J j | C c | 8000 |

| Ⴠ | ⴠ | ჰ | Ჰ | U+10F0 | hae | /h/ | H h | H h | H h | H h | 9000 |

| Ⴥ | ⴥ | ჵ | Ჵ | U+10F5 | hoe | /oː/, Bats /ʕ, ɦ/ | — | Ō ō | — | — | 10000 |

| — | — | ჶ | Ჶ | U+10F6 | fi | Laz & Ossetian /f/ | — | F f | — | F f | — |

| — | — | ჹ | Ჹ | U+10F9 | turned gani | Dagestanian languages /ɢ/ in evangelical literature[2] | — | — | — | — | — |

| — | — | ჺ | Ჺ | U+10FA | aini | Bats /ʕ/[2] | — | — | — | — | — |

| — | — | ჼ | — | U+10FC | modifier nar | Bats /◌̃/ nasalization of preceding vowel[61] | — | — | — | — | — |

| Ⴭ | ⴭ | ჽ | Ჽ | U+10FD | aen[63] | Ossetian /ə/[62] | — | — | — | — | — |

| — | — | ჾ | Ჾ | U+10FE | hard sign[63] | Abkhaz velarization of preceding consonant[63] | — | — | — | — | — |

| — | — | ჿ | Ჿ | U+10FF | labial sign[63] | Abkhaz labialization of preceding consonant[63] | — | — | — | — | — |

Use for other non-Kartvelian languages

- Ossetian language until the 1940s.[75]

- Abkhaz language until the 1940s.[76]

- Ingush language (historically), later replaced in the 17th century by Arabic and by the Cyrillic script in modern times.[77]

- Chechen language (historically), later replaced in the 17th century by Arabic and by the Cyrillic script in modern times.[78]

- Avar language (historically), later replaced in the 17th century by Arabic and by the Cyrillic script in modern times.[79][80]

- Turkish language and Azerbaijani language. A Turkish Gospel, dictionary, poems, medical book dating from the 18th century.[81]

- Persian language. The 18th-century Persian translation of the Arabic Gospel is kept at the National Center of Manuscripts in Tbilisi.

- Armenian language. In the Armenian community in Tbilisi, the Georgian script was occasionally used for writing Armenian in the 18th and 19th centuries, and some samples of this kind of texts are kept at the Georgian National Center of Manuscripts in Tbilisi.[82]

- Russian language. In the collections of the National Center of Manuscripts in Tbilisi there are also a few short poems in the Russian language written in Georgian script dating from the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

- Azerbaijani language. Used by Azeris in Georgia.[83]

- Other Northeast Caucasian languages. The Georgian script was used for writing North Caucasian and Dagestani languages in connection with Georgian missionary activities in the areas starting in the 18th century.[84]

Computing

Unicode

The first Georgian script was included in Unicode Standard in October 1991 with the release of version 1.0. In creating the Georgian Unicode block, important roles were played by German Jost Gippert, a linguist of Kartvelian studies, and American-Irish linguist and script-encoder Michael Everson, who created the Georgian Unicode for the Macintosh systems.[85] Significant contributions were also made by Anton Dumbadze and Irakli Garibashvili[86] (not to be mistaken with the Prime Minister of Georgia Irakli Garibashvili).

Georgian Mkhedruli script received an official status for being Georgia's internationalized domain name script for (.გე).[87]

Mtavruli letters were added in Unicode version 11.0 in June 2018.[88] They are capital letters with similar letterforms to Mkhedruli, but with descenders shifted above the baseline, with a wider central oval, and with the top slightly higher than the ascender height.[89][90][91] Before this addition, font creators included Mtavruli in various ways. Some fonts came in pairs, of which one had lowercase letters and the other uppercase; some Unicode fonts placed Mtavruli letterforms in the Asomtavruli range (U+10A0-U+10CF) or in the Private Use Area, and some ASCII-based ones mapped them to the ASCII capital letters.[53]

Blocks

Georgian characters are found in three Unicode blocks. The first block (U+10A0–U+10FF) is simply called Georgian. Mkhedruli (modern Georgian) occupies the U+10D0–U+10FF range (shown in the bottom half of the first table below) and Asomtavruli occupies the U+10A0–U+10CF range (shown in the top half of the same table). The second block is the Georgian Supplement (U+2D00–U+2D2F), and it contains Nuskhuri.[2] Mtavruli capitals are included in the Georgian Extended block (U+1C90–U+1CBF).

Mtavruli is defined as the upper case, but not title case, of Mkhedruli, and Asomtavruli as the upper case and title case of Nuskhuri.[92]

| Georgian[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+10Ax | Ⴀ | Ⴁ | Ⴂ | Ⴃ | Ⴄ | Ⴅ | Ⴆ | Ⴇ | Ⴈ | Ⴉ | Ⴊ | Ⴋ | Ⴌ | Ⴍ | Ⴎ | Ⴏ |

| U+10Bx | Ⴐ | Ⴑ | Ⴒ | Ⴓ | Ⴔ | Ⴕ | Ⴖ | Ⴗ | Ⴘ | Ⴙ | Ⴚ | Ⴛ | Ⴜ | Ⴝ | Ⴞ | Ⴟ |

| U+10Cx | Ⴠ | Ⴡ | Ⴢ | Ⴣ | Ⴤ | Ⴥ |

|

Ⴧ |

|

|

|

|

|

Ⴭ |

|

|

| U+10Dx | ა | ბ | გ | დ | ე | ვ | ზ | თ | ი | კ | ლ | მ | ნ | ო | პ | ჟ |

| U+10Ex | რ | ს | ტ | უ | ფ | ქ | ღ | ყ | შ | ჩ | ც | ძ | წ | ჭ | ხ | ჯ |

| U+10Fx | ჰ | ჱ | ჲ | ჳ | ჴ | ჵ | ჶ | ჷ | ჸ | ჹ | ჺ | ჻ | ჼ | ჽ | ჾ | ჿ |

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

| Georgian Supplement[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+2D0x | ⴀ | ⴁ | ⴂ | ⴃ | ⴄ | ⴅ | ⴆ | ⴇ | ⴈ | ⴉ | ⴊ | ⴋ | ⴌ | ⴍ | ⴎ | ⴏ |

| U+2D1x | ⴐ | ⴑ | ⴒ | ⴓ | ⴔ | ⴕ | ⴖ | ⴗ | ⴘ | ⴙ | ⴚ | ⴛ | ⴜ | ⴝ | ⴞ | ⴟ |

| U+2D2x | ⴠ | ⴡ | ⴢ | ⴣ | ⴤ | ⴥ |

|

ⴧ |

|

|

|

|

|

ⴭ |

|

|

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

| Georgian Extended[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+1C9x | Ა | Ბ | Გ | Დ | Ე | Ვ | Ზ | Თ | Ი | Კ | Ლ | Მ | Ნ | Ო | Პ | Ჟ |

| U+1CAx | Რ | Ს | Ტ | Უ | Ფ | Ქ | Ღ | Ყ | Შ | Ჩ | Ც | Ძ | Წ | Ჭ | Ხ | Ჯ |

| U+1CBx | Ჰ | Ჱ | Ჲ | Ჳ | Ჴ | Ჵ | Ჶ | Ჷ | Ჸ | Ჹ | Ჺ |

|

|

Ჽ | Ჾ | Ჿ |

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

Non-Unicode encodings

Mac OS Georgian is an unofficial[clarification needed] character encoding created by Michael Everson for Georgian on classic Mac OS. It is an extended ASCII encoding, using the 128 code points from 0x80 through 0xFF to represent the characters of the Asomtavruli and Mkhedruli scripts plus a number of widely-used symbols not included in 7-bit ASCII.[93]

Keyboard layouts

Below is the standard Georgian-language keyboard layout, the traditional layout of manual typewriters.

| “ „ |

1 ! |

2 ? |

3 № |

4 § |

5 % |

6 : |

7 . |

8 ; |

9 , |

0 / |

- _ |

+ = |

← Backspace |

| Tab key | ღ | ჯ | უ | კ | ე ჱ | ნ | გ | შ | წ | ზ | ხ ჴ | ც | ) ( |

| Caps lock | ფ ჶ | ძ | ვ ჳ | თ | ა | პ | რ | ო | ლ | დ | ჟ | Enter key ↵ |

| Shift key ↑ |

ჭ | ჩ | ყ | ს | მ | ი ჲ | ტ | ქ | ბ | ჰ ჵ | Shift key ↑ |

| Control key | Win key | Alt key | Space bar | AltGr key | Win key | Menu key | Control key | |

Gallery

Gallery of Asomtavruli, Nuskhuri, Mkhedruli and Mtavruli scripts.

Gallery of Asomtavruli

Asomtavruli at Barakoni

Doliskana inscriptions in Asomtavruli

Asomtavruli inscription at Ishkhani

Asomtavruli inscription at Nikortsminda Cathedral

Gallery of Nuskhuri

Nuskhuri of Mokvi

Nuskhuri Iadgari of Mikael Modrekili, 10th century

Nuskhuri by Nikrai, 12th century

Gallery of Mkhedruli

Handwriten Mkhedruli royal charter of King Bagrat IV of Georgia

Mkhedruli royal charter of King George II of Georgia

Handwriten Mkhedruli royal charter of King David IV of Georgia. The small text at top is written with Nuskhuri.

Mkhedruli royal charter of King George III of Georgia

Mkhedruli royal charter of Queen Tamar of Georgia

Mkhedruli royal charter of King George IV of Georgia

Mkhedruli royal charter of King George V of Georgia

Gallery of Mtavruli

References

«Կասկածել Կորյունի վրա՝ նշանակում է առհասարակ ուրանալ պատմությունը։» translation: "To doubt Koryun['s account] means to deny history itself.

«408 ... հնարում է վրաց գրերը»

- Everson, Michael (2002-02-20). "Mac OS Georgian to Unicode table". Evertype. Retrieved 2020-12-07.

Sources

- Allen, William Edward David; Gugushvili, A., eds. (1937). Georgica: A Journal of Georgian and Caucasian Studies (4–5): 324.

{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Aronson, Howard Isaac (1990). Georgian: A Reading Grammar. Columbus, OH: Slavica Publishers. ISBN 978-0-89357-207-5.

- Bowersock, Glen Warren; Brown, Peter; Grabar, Oleg (1999). Late Antiquity: A Guide to the Postclassical World. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-51173-6.

- "Georgia". Chambers's encyclopaedia; a dictionary of universal knowledge. Vol. 5. London: W. & R. Chambers. 1901.

- Daniels, Peter T. (1996). The World's Writing Systems. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-507993-7.

- Enwall, Joakim (2010). "Turkish texts in Georgian script: Sociolinguistic and ethno-linguistic aspects". In Boeschoten, Hendrik; Rentzsch, Julian (eds.). Turcology in Mainz. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3-447-06113-1.

- George, Julie A. (2009). The Politics of Ethnic Separatism in Russia and Georgia. Palgrave Macmillan US. ISBN 978-0-230-10232-3.

- Gillam, Richard (2003). Unicode Demystified: A Practical Programmer's Guide to the Encoding Standard. Addison-Wesley Professional. ISBN 978-0-201-70052-7.

- Greppin, John A.C. (1981). "Some comments on the origin of the Georgian alphabet". Bazmavēp (139): 449–456.*Haarmann, Harald (2012). "Ethnic Conflict and standardisation in the Caucasus". In Matthias Hüning; Ulrike Vogl; Olivier Moliner (eds.). Standard Languages and Multilingualism in European History. John Benjamins Publishing. p. 299. ISBN 978-90-272-0055-6.

- Hewitt, B. G. (1995). Georgian: A Structural Reference Grammar. John Benjamins Publishing. ISBN 978-90-272-3802-3.

- Hüning, Matthias; Vogl, Ulrike; Moliner, Olivier (2012). Standard Languages and Multilingualism in European History. John Benjamins Publishing. ISBN 978-90-272-0055-6.

- Katzner, Kenneth; Miller, Kirk (2002). The Languages of the World. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-53288-9.

- Kemertelidze, Nino (1999). "The Origin of Kartuli (Georgian) Writing (Alphabet)". In David Cram; Andrew R. Linn; Elke Nowak (eds.). History of Linguistics 1996. Vol. 1: Traditions in Linguistics Worldwide. John Benjamins Publishing Company. ISBN 978-90-272-8382-5.

- Machavariani, E. (2011). Georgian manuscripts. Tbilisi.

- Mchedlidze, T. (2013). The restored Georgian alphabet. Fulda, Germany.

- Nakanishi, Akira (1990). Writing Systems of the World. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8048-1654-0.

- Paolini, Stefano; Cholokashvili, Nikoloz (1629), Dittionario giorgiano e italiano, Rome: Palazzo di Propaganda Fide

- Rapp, Stephen H. (2003). Studies in medieval Georgian historiography: early texts and Eurasian contexts. Peeters Publishers. ISBN 978-90-429-1318-9.

- Rapp, Stephen H. (2006). "Recovering the Pre-National Caucasian Landscape". Mythical Landscapes then and Now: The Mystification: 13–52.

- Rapp, Stephen H. (2010). "Georgian Christianity". In Ken Parry (ed.). The Blackwell Companion to Eastern Christianity. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4443-3361-9.

- Rayfield, Donald (2013). The Literature of Georgia: A History. RoutledgeCurzon. ISBN 978-0-7007-1163-5.

- Shanidze, Mzekala (2000). "Greek influence in Georgian linguistics". In Sylvain Auroux (ed.). History of the Language Sciences / Geschichte der Sprachwissenschaften / Histoire des sciences du language. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-019400-5.

- Shanidze, Akaki (2003), ქართული ენა [The Georgian Language] (in Georgian), Tbilisi, ISBN 978-1-4020-1440-6

- Shanidze, Akaki (1973). The Basics of the Georgian language grammar. Tbilisi.

- Thomson, Robert W. (1996). Rewriting Caucasian History: The Medieval Armenian Adaptation of the Georgian Chronicles : the Original Georgian Texts and the Armenian Adaptation. Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-826373-9.

- West, Barbara A. (2010). Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Asia and Oceania. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4381-1913-7.

Further reading

- Barnaveli, T. Inscriptions of Ateni Sioni Tbilisi, 1977

- Gamkrelidze, T. Writing system and the old Georgian script Tbilisi, 1989

- Javakhishvili, I. Georgian palaeography Tbilisi, 1949

- Kilanawa, B. Georgian script in the writing systems Tbilisi, 1990

- Khurtsilava, B. The Georgian asomtavruli alphabet and its authors: Bakur and Gri Ormizd, Tbilisi, 2009

- Pataridze, R. Georgian Asomtavruli Tbilisi, 1980

- Shosted, Ryan K.; Chikovani, Vakhtang (2006), "Standard Georgian", Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 36 (2): 255–264, doi:10.1017/S0025100306002659

External links

- Gallery of Mkhedruli, Omniglot page on Mkhedruli which shows some stylistic variations mentioned above

- Georgian alphabet animation on YouTube, produced by the Ministry of Education and Science of Georgia. Gives the sound of each letter, illustrates several fonts, and shows the stroke order of each letter.

- Lasha Kintsurashvili and Levan Chaganava, submissions to the 2014 International Exhibition of Calligraphy

- Reference grammar of Georgian by Howard Aronson (SEELRC, Duke University)

- "Unicode Code Chart (10A0–10FF) for Georgian scripts" (PDF). (105 KB)

- "Transliteration of Georgian" (PDF). (105 KB)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Georgian_scripts

Georgian era

| |||

| Periods in English history |

|---|

|

|

| Timeline |

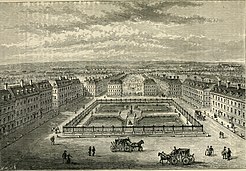

The Georgian era was a period in British history from 1714 to c. 1830–1837, named after the Hanoverian kings George I, George II, George III and George IV. The definition of the Georgian era is often extended to include the relatively short reign of William IV, which ended with his death in 1837. The subperiod that is the Regency era is defined by the regency of George IV as Prince of Wales during the illness of his father George III.[2] The transition to the Victorian era was characterized in religion, social values, and the arts by a shift in tone away from rationalism and toward romanticism and mysticism.

The term Georgian is typically used in the contexts of social and political history and architecture. The term Augustan literature is often used for Augustan drama, Augustan poetry and Augustan prose in the period 1700–1740s. The term Augustan refers to the acknowledgement of the influence of Latin literature from the ancient Roman Republic.[3]

The term Georgian era is not applied to the time of the two 20th-century British kings of this name, George V and George VI. Those periods are simply referred to as Georgian.[4]

Arts and culture

Georgian society and its preoccupations were well portrayed in the novels of writers such as Daniel Defoe, Jonathan Swift, Samuel Richardson, Henry Fielding, Laurence Sterne, Mary Shelley and Jane Austen, characterised by the architecture of Robert Adam, John Nash and James Wyatt and the emergence of the Gothic Revival style, which hearkened back to a supposed golden age of building design.

The flowering of the arts was most vividly shown in the emergence of the Romantic poets, principally through Samuel Taylor Coleridge, William Wordsworth, Percy Bysshe Shelley, William Blake, John Keats, Lord Byron and Robert Burns. Their work ushered in a new era of poetry, characterised by vivid and colourful language, evocative of elevating ideas and themes.[5]

The paintings of Thomas Gainsborough, Sir Joshua Reynolds and the young J. M. W. Turner and John Constable illustrated the changing world of the Georgian period – as did the work of designers like Capability Brown, the landscape designer.

Fine examples of distinctive Georgian architecture are Edinburgh's New Town, Georgian Dublin, Grainger Town in Newcastle upon Tyne, the Georgian Quarter of Liverpool and much of Bristol and Bath.

The music of John Field, Handel, Haydn, Clementi, Johann Christian Bach, William Boyce, Mozart, Beethoven and Mendelssohn was some of the most popular in England at that time.

Grand Tour

The height of the Grand Tour coincided with the 18th century and is associated with Georgian high society. This custom saw young upper-class Englishmen travelling to Italy by way of France and the Netherlands for intellectual and cultural purposes.[6] Notable historian Edward Gibbon remarked of the Grand Tour as useful for intellectual self-improvement.[7] The journey and stay abroad would usually take a year or more. This would eventually lead to the basis for the acquisition and spread of art collections back to England as well as fashions and paintings from Italy.[6] The custom also helped popularise the macaroni style that was soon to become fashionable at the time.[8]

Social change

It was a time of immense social change in Britain, with the beginnings of the Industrial Revolution which began the process of intensifying class divisions, and the emergence of rival political parties like the Whigs and Tories.

In rural areas the Agricultural Revolution saw huge changes to the movement of people and the decline of small communities, the growth of the cities and the beginnings of an integrated transportation system but, nevertheless, as rural towns and villages declined and work became scarce there was a huge increase in emigration to Canada, the North American colonies (which became the United States during the period) and other parts of the British Empire.

Evangelical religion and social reform

In England, the evangelical movement inside and outside the Church of England gained strength in the late 18th and early 19th century. The movement challenged the traditional religious sensibility that emphasised a code of honour for the upper class, and suitable behaviour for everyone else, together with faithful observances of rituals. John Wesley (1703–1791) and his followers preached revivalist religion, trying to convert individuals to a personal relationship with Christ through Bible reading, regular prayer, and especially the revival experience. Wesley himself preached 52,000 times, calling on men and women to "redeem the time" and save their souls. Wesley always operated inside the Church of England, but at his death, his followers set up outside institutions that became the Methodist Church.[9] It stood alongside the traditional nonconformist churches, Presbyterians, Congregationalist, Baptists, Unitarians, and Quakers. The nonconformist churches, however, were less influenced by revivalism.[10]

The Church of England remained dominant in England but it had a growing evangelical, revivalist faction, the "Low Church". Its leaders included William Wilberforce and Hannah More. It reached the upper class through the Clapham Sect. It did not seek political reform, but rather the opportunity to save souls through political action by freeing slaves, abolishing the duel, prohibiting cruelty to children and animals, stopping gambling, and avoiding frivolity on the Sabbath; they read the Bible every day. All souls were equal in God's view, but not all bodies, so evangelicals did not challenge the hierarchical structure of English society.[11] As R. J. Morris noted in his 1983 article "Voluntary Societies and British Urban Elites, 1780-1850," "[m]id-eighteenth-century Britain was a stable society in the sense that those with material and ideological power were able to defend this power in an effective and dynamic manner," but "in the twenty years after 1780, this consensus structure was broken."[12] Anglican Evangelicalism thus, as historian Lisa Wood has argued in her book Modes of Discipline: Women, Conservatism, and the Novel After the French Revolution, functioned as a tool of ruling-class social control, buffering the discontent that in France had inaugurated a revolution; yet it contained within itself the seeds for challenge to gender and class hierarchies.[13]

Empire

The Georgian period saw continual warfare, with France the primary enemy. Major episodes included the Seven Years' War, known in America as the French and Indian War (1754–1763), the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783), the French Revolutionary Wars (1792–1802), the Irish Rebellion of 1798, and the Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815). The British won most of the wars except for the American Revolution, where the combined weight of the United States, France, Spain and the Netherlands overwhelmed Britain, which stood alone without allies.[14]

The loss of the 13 American Colonies was a national disaster. Commentators at home and abroad speculated on the end of Britain as a great power. In Europe, the wars with France dragged on for nearly a quarter of a century, 1793–1815. Britain organised coalition after coalition, using its superb financial system to subsidise infantry forces, and built up its Navy to maintain control of the seas. Victory over Napoleon at the Battle of Trafalgar (1805) and the Battle of Waterloo (1815) under Admiral Lord Nelson and the Duke of Wellington brought a sense of triumphalism and political reaction.[15]

The expansion of empire in Asia was primarily the work of the British East India Company, especially under the leadership of Robert Clive.[16] Captain James Cook was perhaps the most prominent of the many explorers and geographers using the resources of the Royal Navy to develop the Empire and make many scientific discoveries, especially in Australia and the Pacific.[17] Instead of trying to recover the lost colonies in North America, the British built up in Asia a largely new Second British Empire. That new empire flourished during the Victorian and Edwardian eras which were to follow.[18]

The trading nation

The era was prosperous as entrepreneurs extended the range of their business around the globe. By the 1720s Britain was one of the most prosperous countries in the world, and Daniel Defoe boasted:

- we are the most "diligent nation in the world. Vast trade, rich manufactures, mighty wealth, universal correspondence, and happy success have been constant companions of England, and given us the title of an industrious people."[19]

While the other major powers were primarily motivated towards territorial gains, and protection of their dynasties (such as the Habsburg and Bourbon dynasties, and the House of Hohenzollern), Britain had a different set of primary interests. Its main diplomatic goal (besides protecting the homeland from invasion) was building a worldwide trading network for its merchants, manufacturers, shippers and financiers. This required a hegemonic Royal Navy so powerful that no rival could sweep its ships from the world's trading routes, or invade the British Isles. The London government enhanced the private sector by incorporating numerous privately financed London-based companies for establishing trading posts and opening import-export businesses across the world. Each was given a monopoly of trade to the specified geographical region. The first enterprise was the Muscovy Company set up in 1555 to trade with Russia. Other prominent enterprises included the East India Company, and the Hudson's Bay Company in Canada. The Company of Royal Adventurers Trading to Africa had been set up in 1662 to trade in gold, ivory and slaves in Africa; it was re-established as the Royal African Company in 1672 and focused on the slave trade. British involvement in the each of the four major wars, 1740 to 1783, paid off handsomely in terms of trade. Even the loss of the 13 colonies was made up by a very favourable trading relationship with the new United States of America. British gained dominance in the trade with India, and largely dominated the highly lucrative slave, sugar, and commercial trades originating in West Africa and the West Indies. China would be next on the agenda. Other powers set up similar monopolies on a much smaller scale; only the Netherlands emphasized trade as much as England.[20][21]

Mercantilism was the basic policy imposed by Britain on its colonies.[22] Mercantilism meant that the government and the merchants became partners with the goal of increasing political power and private wealth, to the exclusion of other empires. The government protected its merchants—and kept others out—by trade barriers, regulations, and subsidies to domestic industries in order to maximise exports from and minimise imports to the realm. The government had to fight smuggling, which became a favourite American technique in the 18th century to circumvent the restrictions on trading with the French, Spanish or Dutch. The goal of mercantilism was to run trade surpluses, so that gold and silver would pour into London. The government took its share through duties and taxes, with the remainder going to merchants in Britain. The government spent much of its revenue on a large and powerful Royal Navy, which not only protected the British colonies but threatened the colonies of the other empires, and sometimes seized them. The colonies were captive markets for British industry, and the goal was to enrich the mother country.[23]

Most of the companies earned good profits, and enormous personal fortunes were created in India, but there was one major fiasco that caused heavy losses. The South Sea Bubble was a business enterprise that exploded in scandal. The South Sea Company was a private business corporation supposedly set up much like the other trading companies, with a focus on South America. Its actual purpose was to renegotiate previous high-interest government loans amounting to £31 million through market manipulation and speculation. It issued stock four times in 1720 that reached about 8,000 investors. Prices kept soaring every day, from £130 a share to £1,000, with insiders making huge paper profits. The Bubble collapsed overnight, ruining many speculators. Investigations showed bribes had reached into high places—even to the king. The future prime minister Robert Walpole managed to wind it down with minimal political and economic damage, although some suffering extreme loss fled to exile or committed suicide.[24][25]

Political and social revolt