Brabantine Gothic

Brabantine Gothic, occasionally called Brabantian Gothic, is a significant variant of Gothic architecture that is typical for the Low Countries. It surfaced in the first half of the 14th century at St. Rumbold's Cathedral in the City of Mechelen.[1][2][Note 1][3]

Reputed architects such as Jean d'Oisy,[4] Jacob van Thienen,[5] Everaert Spoorwater,[6] Matheus de Layens,[7] and the Keldermans and De Waghemakere[8] families disseminated the style and techniques to cities and towns of the Duchy of Brabant and beyond.[Note 2] For churches and other major buildings, the tenor prevailed and lasted throughout the Renaissance.[9]

Harbingers

Brabantine Gothic, in a Low Countries context also referred to as High Gothic, differs from the earlier introduced Scheldt Gothic, which typically had the main tower above the crossing of a church, maintained Romanesque horizontal lines, and applied blue-gray stone quarried from the vicinity of Tournai at the river Scheldt that allowed its transportation in particular in the old County of Flanders.[10][11]

Mosan Gothic (Meuse Gothic) refers to the river Maas (or Meuse, borrowed from French), mainly in the south-eastern parts of the Low Countries: the modern provinces of Limburg in the Netherlands, Limburg, and Liège in Belgium. Though of a later origin than Scheldt Gothic, it also still showed more Romanesque features, including smaller windows. Marlstone was used, and around the capitals on limestone columns are sculptured leaves of irises.[12]

Characteristics

Two centuries of Brabantine Gothic design

Surface conditions and available materials varied. Larger churches could take centuries of building during which expertise and fashions caused successive architects to evolve further from the original plans. Or, Romanesque churches became rebuilt in phases of dismantling and replacing, as (apart from its crypt) St. Bavo's Cathedral in Ghent: the early 14th-century chancel is influenced by northern French and Scheldt Gothic, a century later a radiating chapel appeared, and between 1462 and 1538 the mature Brabantine Gothic west tower was erected; the nave was then still to be finished.[13] Though few buildings are of an entirely consistent style, the ingenuity and craftsmanship of architects could realize a harmonious blend. The ultimate concepts were drawn centuries after the earliest designs. It follows that Brabantine Gothic style is neither homogeneous, nor strictly defined.[Note 3][14][15]

Features

The Brabantine Gothic style originated with the advent of the Duchy of Brabant and spread across the Burgundian Netherlands. Besides minor influences by the High Cathedral of St. Peter and St. Mary in Cologne, the architecture builds on the classic French Gothic style as practiced in the construction of cathedrals such as those in Amiens and Reims.

The structure of the church buildings in Brabant was largely the same: a large-scale cruciform floor plan with three-tier elevation along the nave and side aisles (pier arches, triforium, clerestory) and a choir backed by a half-round ambulatory. The slender tallness of the French naves however, was never surpassed, and the size tended to be slightly more modest.

It is characterized by using light-coloured sandstone or limestone, which allowed rich detailing but is erosion-prone. The churches typically have round columns with cabbage foliage sculpted capitals. From there half-pillar buttresses continue often without interruption into the vault ribs. The triforium and the windows of the clerestory generally continue into one another, with the windows taking the entire space of the pointed arch. An ambulatory with radiating chapels (chevet) is part of the design (though at the 15th-century choir in Breda added later on). Whereas the cathedrals in Brussels and Antwerp are notable exceptions, the main porch is straight under the single west tower, in French called clocher-porche.

An alternative type originated with the cathedral of Antwerp: instead of round columns with a capital impost, bundled pillars profiled in the columns continue without interruption through the ribs of vaults and arches – a style followed for churches in 's-Hertogenbosch and Leuven. In addition, the pier arches between nave and aisles are exceptionally wide, and the triforium is omitted. Instead, a transom of tracery is placed above the pier arches. This type was followed by other major churches in Antwerp, St. Martin Church in Aalst, and St. Michael's Church in Ghent.

Demer Gothic in the Hageland and Campine Gothic are regional variants of Brabantine Gothic in the south-eastern part of the former duchy.[Note 4] Those styles can be distinguished merely by the use of local rust-brown bricks.[Note 5][16]

Brabantine Gothic city halls are built in the shape of gigantic box reliquaries with corner turrets and usually a belfry. The exterior is often profusely decorated.

Adaptations in Holland and of Zeeland

Many churches in the former Counties of Holland and of Zeeland are built in a style sometimes inaccurately separated as Hollandic and as Zeelandic Gothic. These are in fact Brabantine Gothic style buildings with concessions necessitated by local conditions. Thus (except for Dordrecht), because of the soggy ground, weight was saved by wooden barrel vaults instead of stone vaults and the flying buttresses required for those. In most cases, the walls were made of bricks but cut natural stone was not unusual.

Everaert Spoorwater played an important role in spreading Brabantine Gothic into Holland and Zeeland. He perfected a method by which the drawings for large constructions allowed ordering virtually all natural stone elements from quarries on later Belgian territory, then at the destination needing merely their cementing in place. This eliminated storage near the construction site, and the work could be done without the permanent presence of the architect.

Renowned examples of Brabantine Gothic architecture

In the former Duchy of Brabant

Ecclesiastical buildings

- In order of the year mentioned for their earliest Brabantine Gothic style characteristics

- St. Rumbold's Cathedral in Mechelen, early Gothic building started around 1200 and consecrated 1312, its first clearly Brabantine Gothic features: ambulatory and 7 radiant chapels from 1335, possibly by Jean d'Oisy[1]

- Church of Our Lady in Aarschot, from 1337 by Jacob Piccart

- St. Martin's Basilica in Halle, from 1341 possibly by Jean d'Oisy

- Collegiate Church of St. Peter and St. Guido in Anderlecht (Brussels), from 1350

- Cathedral of Our Lady in Antwerp, from 1352

- Church of Our Lady-at-the-Pool in Tienen, from 1358 by Jean d'Oisy

- St. John's Cathedral in 's-Hertogenbosch, from about 1370, considered the height of Brabantine Gothic in the present-day Netherlands

- St. Gummarus' Church in Lier, from 1378; the design of the choir is an imitation of that of St. Rumbold's at Mechelen.

- Church of Our Lady-across-the-Dijle in Mechelen, from before 1400[17]

- St. Peter's Church in Leuven, from about 1400

- St. Sulpicius and St. Denis Collegiate Church (colloq. St. Sulpicius Church) in Diest, from before 1402 start for a radiating chapel by the Frenchman Pierre de Savoye - Demer Gothic[18]

- St. Bavo's Cathedral in Ghent, from early 15th century

- Large Church or Church of Our Lady in Breda, from 1410, considered the most pure and elegant Brabantine Gothic in the present-day Netherlands

- Cathedral of St. Michael and St. Gudula in Brussels

- Church of Our Blessed Lady of the Sablon in Brussels

- St. Martin's Church in Aalst

- Gertrudiskerk in Bergen op Zoom

Cathedral of St. Michael and St. Gudula in Brussels

Church of Our Blessed Lady of the Sablon in Brussels

Gertrudiskerk in Bergen op Zoom

Secular buildings

- Brussels' Town Hall

- Leuven's Town Hall

- Margraves' Palace (Dutch: Markiezenhof) in Bergen op Zoom

- Mechelen's Town Hall, north wing (in 1526 designed and partially built, 1900-1911 partially rebuilt and fully completed)[Note 3]

- Oirschot's former Town Hall[19] (Brick building that also housed the Vierschaar, in a minor town: characteristic shrine shape but extremely sober)

- Round Table (Dutch: Tafelrond) in Leuven, 1479 by Matheus de Layens, guildhall built 1480-1487 internally comprising 3 houses, demolished 1817, reconstructed following original plans 1921[20][21]

Margraves' Palace in Bergen op Zoom

Mechelen's Town Hall

In the former Counties of Holland and of Zeeland

Ecclesiastical buildings

- Large Church or Church of Our Lady in Dordrecht (Holland), the present form dates from 1470.

- Large Church or Grote or Sint-Laurenskerk in Alkmaar (Holland)

- Large Church or St. Grote of Sint-Laurenskerk in Rotterdam (Holland)

- Large Church or Grote Kerk in Haarlem (Holland)

- Highland Church or St. Pancras' Church in Leiden (Holland)

- St Willibrordus in Hulst[22][23]

- Old Church, formerly St. Nicolas' Church, in Amsterdam (largest medieval wooden barrel vault in Europe; wooden spire)[24][Note 7]

- St. Livinus' Monster Tower (Dutch: St.-Lievensmonstertoren) in Zierikzee (Zeeland) (separated by a gap from the meanwhile demolished church building)[25][26][Note 8]

Secular buildings

- Gouda's Town Hall (Holland)

- Middelburg's Town Hall (Zeeland)

Gouda's Town Hall

Middelburg's Town Hall

Elsewhere

Ecclesiastical buildings

- St. Martin's Cathedral in Ypres, in the former County of Flanders[27]

- St. Michael's Church in Ghent, in the former County of Flanders

- St. Willibrord's Basilica in Hulst, in Zeelandic Flanders: until 1648 in the County of Flanders, currently in the Province of Zeeland in the Netherlands

- St. Waltrude Collegiate Church in Mons, in the former County of Hainaut (built with a hard sandstone and blue limestone)[28]

- St. Lambert's Church in Nederweert, until 1703 in the Prince-bishopric of Liège (though during a part of the 16th century County of Horn), currently in the Province of Limburg in the Netherlands

- St. Martin's Cathedral or Domkerk in Utrecht, between Counties of Brabant and of Holland, and Duchy of Guelders in the Netherlands (Gothic church on an island in the Rhine, possibly directly inspired by the cathedral in Cologne, though it has a single west tower. This tower became a regional model referred to as Utrecht & Sticht Gothic).

Secular buildings

- Damme's Town Hall, in the former County of Flanders

- Oudenaarde's Town Hall, in the former County of Flanders

Damme's Town Hall

Notes

Mostly fifteenth-century constructions, Gothic churches in the former Duchy of Guelders are Lower Rhine Gothic, following a style from the area along the Lower Rhine in present-day Germany.

- In Mechelen, the very heavy St.Rumbold's tower (now 97 metres high but designed to reach 167, which is 5 metres more than any church tower attains) was being built on earlier wetlands. After a few years, in 1454, its chief architect Andries I Keldermans construed the tower at Zierikzee, where dreaded leaning or sagging of the tower (now 62 metres but designed for ca. 130) could wreck the church. This concern led to fully separated edifices, a solution as applied in Mechelen. At both places, in the early 16th century the upper part of the tower became forsaken, not for technical but for financial reasons. The gap with the cathedral was closed upon finishing the construction. That deliberately weak connection had not been made in Zierikzee when the collegiate church burned down, in 1832.

References

As the Gothic style develops in its secondary period (late thirteenth and beginning of fourteenth century) the windows increase in size, the pillars are fluted and the tracery of the windows becomes more and more complicated. The best examples of this particular Gothic still in existence are the choir of St. Paul at Liege and Notre Dame of Huy.

- Doperé, Frans (1996). "Les techniques (...) chantiers dans l'est du Brabant pendant la prémière moitié du XVe siècle". In Lodewijckx, Marc (ed.). Acta

archaeologica lovaniensia monographiae Vol. 8: Archaeological and

historical aspects of West-European societies: album amicorum André Van

Doorselaer. p. 426. ISBN 978-90-6186-722-7. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- Vandeputte, O, ed. (2007). Gids voor Vlaanderen – Toeristische en culturele gids voor alle steden en dorpen in Vlaanderen (in Dutch). p. 324. ISBN 978-90-209-5963-5. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- "Historique de la collégiale". La collégiale Sainte-Waudru (in French). ASBL Sainte Waudru, Mons, Belgium. Archived from the original on 2012-03-27. Retrieved 15 July 2011. With sub links:

the church: édifices antérieurs Archived 2012-03-27 at the Wayback Machine ,

chantier Archived 2012-03-27 at the Wayback Machine ,

réparations et restauration Archived 2012-03-27 at the Wayback Machine ;

the tower: projet Archived 2012-03-27 at the Wayback Machine ,

chantier Archived 2012-03-27 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 15 July 2011

"Sainte-Waudru et le gothique brabançon - introduction". La collégiale Sainte-Waudru (in French). ASBL Sainte Waudru, Mons, Belgium. Retrieved 15 July 2011.[permanent dead link] Continued with: pourquoi brabançonne ? Archived 2012-03-27 at the Wayback Machine , relation avec autres églises brabançonnes Retrieved 15 July 2011

Sources

- Cammaerts, Emile. Belgium, From the Roman Invasion to the Present Day. T. Fisher Unwin Ltd, London, 1921 (republished by The Project Gutenberg eBook, 2008). p. 359.

(Note: Several construction dates have become contradicted by more recent sources) - "History & styles: Gothic (1254-ca. 1600)". The virtual museum of religious architecture in The Netherlands. www.archimon.nl. Retrieved 13 July 2011.

(On a specialized blog explicitly focusing on the present-day Netherlands, though a few of those described variant styles are prevalent in Belgium.) - "Steen: materialen, technieken en toepassingen" (PDF) (in Dutch). Heemkring Opwijk-Mazenzele, Belgium. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-06-26. Retrieved 14 July 2011.

(Stone: materials, techniques, and applications - focused on Belgium and south-eastern Netherlands) - "Geschiedenis van de bouwkunst – Hoofdstuk 2 Gotische bouwkunst" (PDF) (in Dutch). Sint Lukas Kunsthumaniora, Belgium (Online tool for 5th and 6th year students of Architectural and Interior Arts). Retrieved 14 July 2011.

(History of Gothic architecture - international, and specific attention for Belgium) - Defoort, Herman. "Gotische kunst". Websthetica, Tekststek voor kunst en esthetica sinds 2001 (in Dutch). Retrieved 15 July 2011.

(Gothic - international, and specific attention for Brabantine Gothic) - Savenije, Marjan; Smelt, Susan. "Wat zijn de kenmerken van de gotische architectuur?" (PDF) (in Dutch). Rooms-Katholieke Scholengemeenschappen Pius X College en St.-Canisius, Almelo, Netherlands. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 March 2012. Retrieved 18 July 2011.

(Sober description of Gothic styles in the Low Counties) - de Naeyer, André. "La reconstruction des monuments et des sites en Belgique après la première guerre mondiale" (Pdf 2.2 KB). Monumentum Vol. XX-XXI-XXII, 1982 (in French). Documentation Centre Unesco - Icomos. pp. 167–187. Retrieved 15 July 2011.

(The Reconstruction of Monuments and Sites in Belgium after World War I)

- Cammaerts, Emile. Belgium, From the Roman Invasion to the Present Day. T. Fisher Unwin Ltd, London, 1921 (republished by The Project Gutenberg eBook, 2008). p. 359.

External links

- Fockema Andreae, S. J.; Hekker, R. C.; ter Kuile, E. H. Duizend jaar bouwen in Nederland (in Dutch). Vol. 2. Allert de Lange, Amsterdam (1957-1958) the Netherlands. Retrieved 19 July 2011. (1000 years of architectural history in the Netherlands)

- "Het stenen landschap". Thuis in Brabant – Geschiedenis (in Dutch). Thuis in Brabant (Erfgoed Brabant), 's Hertogenbosch, Netherlands. Retrieved 18 July 2011. (Site about historical architecture in Brabant, focused on the Netherlands)

- Brabantine Gothic at archINFORM

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brabantine_Gothic

High Gothic

Reims Cathedral (begun 1211), choir and nave (High Gothic); (after 1252) Rayonnant | |

| Country | France |

|---|---|

High Gothic followed Early Gothic architecture and was succeeded in France by Late Gothic in the form of the Flamboyant style. This timetable is not used by French scholars; they devide Gothic architecture into four phases, Primary Gothic, Classic Gothic, Rayonnant Gothic and Flamboyant Gothic. Therefore, in French terms, a few first examples of High Gothic are Classic, but most examples are Rayonnant. High Gothic is often described as the high point of the Gothic style.[1][2]

It started with Reims Cathedral, first stone in 1211, world's first bar tracery between 1215 and 1220. Amiens Cathedral was begun with the western parts in 1220, the eastern parts were built after 1236 to a slightly different design. Beauvais Cathedral was begun in 1225); the transept of Chartres Cathedral, after a fire in 1194 rebuilt in the new style until 1225.[1] The great western rose of Chartres Cathedral still consists of Early Gothic plate tracery. The upper parts of the northern tower were completed as late as 1510. The most notable example of German High Gothic, or Hochgotik, is Cologne Cathedral, begun in 1248.

The style first appeared in the second decade of the 13th century. One distinctive characteristic was the use of tracery, or thin ornate ribs of stone, to divide windows and walls and emphasize verticality. another was the elimination of the tribune between the lower arcades and the upper windows. This was made possible by the development of advanced forms of the rib vault and flying buttress. These developments made making possible much greater height and larger windows which filled the churches with light.[1]

Origins

The new style illustrated the ambitions of the French kings of the Capetian dynasty, and particularly Philip II of France, who reigned from 1180 until 1223. He gradually extended his power beyond the Ile-de-France to assume dominance over Normandy, Burgundy, and Brittany. He defeated a coalition of English, German, and Flemish forces at the Battle of Bouvines in 1214, making France the most powerful and prosperous state in Europe. In the process, he reduced the power of the French nobles and granted status to wealthy merchants and other bourgeoisie, who became important sponsors of cathedrals. He founded the University of Paris and was a great builder. He paved the Paris streets and built the first wall around the city, continued the construction of Notre Dame de Paris, and constructed the fortress of the Louvre.

The royal patronage of cathedrals and other Gothic architecture was continued by Louis VIII of France and especially Louis IX of France, or Saint Louis; who paid for the transept rose windows of Notre-Dame and built Sainte-Chapelle as his royal chapel.[3][1]

Some funding for cathedrals came from the royal treasury, and from surprising foreign sources. The construction fund for Chartres Cathedral received contributions both from the French King and Richard the Lion-Hearted of England. A large part of the cost was donated by wealthy merchants and other members of community. The guilds of craftsmen also contributed, and their contributions are often indicated by small panels showing workers in those professions. Windows at Charters Cathedral have panels that illustrate and honour the shoemakers, the fishmongers, water-carriers, the vine-growers, the tanners, the masons, and furriers.[4]

Examples

Reims Cathedral (begun 1211)

Reims Cathedral was the traditional site of the coronation of the Capetian dynasty and for that reason was given special grandeur and importance.[1] A fire in 1210 destroyed much of the old cathedral, giving an opportunity to build a more ambitious structure, the work began in 1211, but was interrupted by a local rebellion in 1233, and not resumed until 1236. The choir was finished by 1241, but work on the facade did not begin until 1252, and was not finished until the 15th century, with the completion of the bell towers.[5]

Unlike the cathedrals of Early Gothic, Reims was built with just three levels instead of four, giving greater space for windows at the top. it also used the more advanced four-part rib vault, which allowed greater height and more harmony in the nave and choir. Instead of alternating columns and piers, the vaults were supported by rounded piers, each of which was surrounded by a cluster of four attached columns that received the weight of the vaults. In addition to the large rose window on the west, smaller rose windows were added to the transepts and over the portals on the west facade, taking the place of the traditional tympanum. Another new decorative feature, blind arcade tracery, was attached to both interior walls and the facade. Even the flying buttresses were given elaborate decoration; they were crowned by small tabernacles containing statues of saints, which were topped with pinnacles. More than 2300 statues covered both the front and the back side of the facade.[5]

Nave of Reims Cathedral with piliers cantonnés supporting quadripartite vaults

Amiens Cathedral (1220–1266)

Amiens Cathedral was begun in 1220 with the ambition of the builders to construct the largest cathedral in France, and they succeeded. It is 145 m (476 ft) long, 70 m (230 ft) wide at the transept, and has a surface area of 7,700 m2 (83,000 sq ft)}.[6] The nave was finished by 1240 and the choir built between 1241 and 1269.[6] Unusually, the names of the architects are known: Robert de Luzarches, and Thomas and Renaud Cormont. Their names and images are found in the labyrinth in the nave.[6]

The immense size of the cathedral required foundations 9 m (30 ft) deep. The nave has three parts and six crossings, while the choir has double collaterals, and ends in a semicircular disambulatory with seven radiating chapels. The three-level elevation of Amiens, like that of Reims, preceded Chartres Cathedral, but was notably different. The great arcades have a height of eighteen meters, equalling the combined heights of the triforium and the high windows above them. The triforium was more complex than Chartres, and had triple bays with trefoil windows, composed of two slender pointed lancet windows topped with a clover-like rose window.[6] The high windows also had a strikingly complex design; in the nave, each was composed of four tall lancet windows, topped by three small roses; while in the transept the upper windows have as many as eight separate lancets.[6]

The vaults have the exceptional height of 42.4 m (139 ft). They are supported by massive piers composed of four columns which give the nave a striking sensation of verticality. The height of the walls, particularly in the chevet, was made possible by the tall flying buttresses, making two leaps to the wall with the support of an elegant system of arches.[6]

On the exterior, the most remarkable High Gothic feature is the quality of the sculpture of the three porches, decorated altogether with fifty-two statues in their original condition. The most celebrated are on the central portal on the west, dedicated to the Last Judgement, and dominated by the statue of Christ giving a blessing which forms the central column of the doorway.[7] During the intense cleaning of the Cathedral in 1992, traces of paint were discovered indicating that all of the sculpture of the exterior was originally painted with vivid colors. This is now sometimes reproduced by projecting colored light onto the cathedral at night.[7]

Beauvais Cathedral (begun 1225)

Beauvais Cathedral in Picardy is in its principle structures an example of Rayonnant Gothic. It was the most ambitious and most unfortunate of High Gothic projects. Its ambition was to become the tallest of all cathedrals. The choir was built with a height of 48.5 meters (159 ft) However, due most likely to an inadequate foundation and support, the choir vaults fell in 1284. The choir was modified and rebuilt, the polygonal apse and Flamboyant transepts were finished, and in 1569 a new central tower was added, 153 meters (502 feet) high, which made Beauvais for a time the tallest structure in the world. However, in 1573 the central tower collapsed. Some parts were modified or reconstructed, but the tower was never rebuilt and the nave was never finished. Today supports are in place to stabilise the transept. Beauvais remains a majestic but unfinished piece of High Gothic architecture.[8]

- Beauvais Cathedral

Cologne Cathedral (choir 1248–1322, western parts 1880)

The construction of the Gothic cathedral of Cologne was started in 1248 by the same Archbishop Konrad von Hochstaden, who promoted the election of William of Holland for ruler of the Holy Roman Empire to finish the rule of Hohenstaufen dynasty, this way. The similarity with Amiens Cathedral is limited to the choir. The towers were projected to a tall height, whereas in Amiens the towers are little higher than the roof of the nave. The choir was completed in 1322 and the decoration of the ambulatory in 1360, but in 1528 the construction ceased until 1823, and the western parts of the Cathedral were completed as late as in 1880.

- Cologne Cathedral

Utrecht Cathedral

The bishopric of Utrecht was a suffragan of Cologne. In 1456, bishop Henry I van Vianden, who had been a capitular of Cologne Cathedral, laid the first stone for Utrecht Cathedral. Its ambulatory was finished in 1295. The Gothic replacement of the old Romanesque nave began as late as in 1467, and the Late Gothic nave was destroyed by a storm, in 1674. Though the Cathedral was up to date in most stylistic matters, and its transept has immensely large windowes, the triforium of the choir has no windows.

- Utrecht Cathedral

Characteristics

Plans

The plans of the High Gothic Cathedrals were very similar. They were extremely long and wide, with a minimal transept and maximum interior space. This made possible much larger ceremonies and the ability to welcome larger numbers of pilgrims. One curiosity of the plan of Chartres Cathedral was the floor, which slightly sloped. This was done to facilitate the cleaning of the cathedral after the departure of pilgrims who slept inside the church.[9]

Reims Cathedral, begun in 1211

Amiens Cathedral, 1220 – c. 1266

Beauvais Cathedral, 1190s–1255, the nave, in this plan the lower portion, was never constructed

Elevations

Thanks largely to the efficiency of the flying buttress and six-part rib vaults, all of the major High Gothic cathedrals except Bourges used the three-level elevation, eliminating the tribunes and keeping the ground floor grand gallery, the triforium, and the clerestory, or high windows. The upper windows in particular grew in size to cover almost all of the upper walls. The arcades also grew in height, occupying half the wall, so the triforium was just a narrow band.[10] The upper windows were often made of translucent grisaille glass, which allowed more light than colored stained glass.[11]

Vaults triforia and upper windows of Amiens Cathedral.[11]

Three-part elevation of nave of Reims Cathedral

Vaults, piers and pillars

All of the High Gothic Cathedrals except Bourges Cathedral used the newer four-part rib vault, which allowed more even weight distribution to the piers and columns in the nave. Early Gothic churches used alternating piers and columns to support the varying weight from the six-part vaults,

In 1192 Notre Dame, which had six-part vaults, had introduced a new kind of support; a central pillar surrounded by four engaged shafts. The pillars supported the gallery, while the shafts continued upwards as colonettes attached to the walls and supported the vaults. Variations of this kind of support gave greater harmony to the appearance of the nave. They frequently had capitals which were decorated with floral sculpture. They appeared at Chartres and then were found, in various forms, in all of the High Gothic Cathedrals.[10]

The massive pillars, surrounded by colonettes, and topped with floral capitals, of Reims Cathedral

Transept vaults and pillars of Amiens Cathedral

Flying buttress

The flying buttress was an essential feature of High Gothic architecture; the great height and large upper windows would have been impossible without them. Buttresses with arches apart from the walls had existed in earlier periods, but they were generally small, close to the walls, and were often hidden by the outer architecture. In High Gothic, the buttresses were nearly as tall as the building itself. massive, and meant to be seen; they were decorated with pinnacles and sculpture.

Flying buttresses had been used to support the upper windows of the apse in the Abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Prés, completed in 1063[12] and then at Notre-Dame de Paris. They were then used in a more ambitious way to support the upper walls of Chartres Cathedral. The first flying buttresses of Chartres were built atop the wall abutments of the nave and choir of the earlier cathedral. They had a double arch reinforced with small columns like the spokes of a wheel. Each small column, with its base and capital, was carved from a single block of stone, Each arch had a sort of stone pyramid on top to add extra weight. Later a second set of arches was added to the nave and choir above the spoked arches, which reached longer and added greater strength.[13]

Similar buttresses were added to each of the High Gothic Cathedrals. The buttresses of each cathedral were unique, and had its own distinct form and decoration. The buttresses of Beauvais Cathedral, the last and tallest High Gothic cathedral, are so high and numerous that they practically hide the cathedral.

Double arches of the apse of Reims Cathedral, capped with stone pinnacles for greater weight

Flying buttresses of Amiens Cathedral

Buttresses practically conceal the choir of Beauvais Cathedral

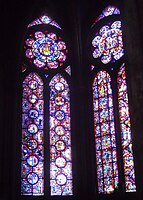

Stained glass and The Rose Window

A type of small round window, called an oculus, had been used in Romanesque churches.[14] The facade of the Basilica of Saint Denis featured an early rose window on its west front. This was made with plate tracery, where the design was formed by a group of variously shaped openings that appeared to be cut out of the wall. A more ambitious model, with the armature of a wheel made of stone mullions, appeared at Senlis Cathedral in 1200. A similar early Gothic window was constructed for the facade of Chartres Cathedral in 1215. It was soon followed by the High Gothic window of the facade of Laon Cathedral (1200-1215).[15] In 1215, the two great transept windows of Chartres Chathedral were completed. These became the model for many similar windows in France and beyond. The amount of stained glass in Chartres was unprecedented – 164 bays, with 2,600 m2 (28,000 sq ft) of stained glass. A remarkably large amount of the original glass is still in place.[16]

Not long after the introduction of the High Gothic rose window, Gothic architects, fearing that the interiors of the cathedrals were too dark, began experimenting with grisaille windows, which emphasized the important figures in the windows, and also brightened the interiors. These were used at Poitiers Cathedral in 1270 and then by Chartres Cathedral around 1300. Large bands of translucent gray glass were put around the fully colored figures of Christ, The Virgin Mary, and other prominent subjects.[11]

Glass in the choir of Amiens Cathedral

West rose window of Reims Cathedral (1252–1275)

Windows of Beauvais Cathedral

Tracery

Tracery is the term for the intricate designs of slender stone bars and ribs which were used to support the glass and to decorate rose windows and other windows and openings. It also was used increasingly on exterior and interior walls, in the form of stone ribs or molding, to create increasingly intricate forms such as blind arcades. This form was called blind tracery.[17]

The west window of Chartres Cathedral used an early form called plate tracery, a geometric pattern of openings in the stonework filled with glass. Prior to 1230, the builders of Reims Cathedral used a more sophisticated form, called bar tracery, in the apse chapel. This was a pattern of cusped circles, made with thin pointed bars of stone projecting inward.[17] This model was followed and developed in the transept windows of Chartres Cathedral, at Amiens Cathedral and the other High Gothic cathedrals. After the middle of the 13th century, the windows began to be decorated with even larger and complex designs, resembling light shining outwards, which gave the name to the Rayonnant style.[17]

Early bar tracery at Reims Cathedral (Prior to 1230)

Sculpture

Sculpture was an integral part of High Gothic. It decorated the facades, the walls, the columns, and other architecure,inside and out. It was not considered deocorative; it was designed to serve as a visual Bible for the many parishioners who could not read.

It is probable that some of the sculptors who made the sculpture of the transepts of Chartres travelled north to Reims, where work began in 1210, and possibly also to Amiens Cathedral, where work began in 1218. Nonetheless, the sculpture of each church has its own distinct characteristics. The sculpture of Amiens shows the influence of ancient Roman sculpture, particularly in the realistically modelled drapery of their clothing. The expressions are passive, and the gestures minimal, giving a sense of calm and serenity. The sculpture of Reims showed a similar calm.[18]

The entirely different and more naturalistic High Gothic style of sculpture appeared on the west front Reims Cathedral in the 1240s. This was the work of the sculptor known as Joseph of Reims, named for the vivid smiling statue of Saint Joseph he made for the facade. He also created the Smiling Angel. This famous work was knocked off the Cathedral by a bombardment in World War I, but was carefully reassembled and is now back in its original place.[19] Reims is also noted for the Gallery of Kings, a sculptural depiction of the French Kings crowned at Reims, which begins on the facade and continues on the inside of the facade.

The vegetal decoration of the capitals of the columns of the nave were another distinctive feature of High Gothic sculpture. They were made in finely crafted vegetal forms, complete with birds and other creatures. This followed an ancient Roman model and had been used at Saint-Denis, but at Reims they became much more realistic and detailed. As the work continued toward the west in the nave, the foliage became more abundant and filled with life. This model was copied in Gothic cathedrals first in France, and then across Europe.[20]

"The Smiling Angel" (1236–45) from Reims Cathedral

Sculpture in the Gallery of Kings of Reims Cathedral

Central tympanum on facade of Amiens Cathedral

Accurately sculpted vegetation (horse chestnuts) on the column capitals of Reims Cathedral

References

- Martindale 1993, p. 51.

Bibliography

In English

- Bony, Jean (1985). French Gothic Architecture of the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-05586-1.

- Houvet, E (2019). Miller, Malcolm B (ed.). Chartres - Guide of the Cathedral. Éditions Houvet. ISBN 2-909575-65-9.

- Martindale, Andrew (1993). Gothic Art. Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-2-87811-058-6.

- Watkin, David (1986). A History of Western Architecture. Barrie and Jenkins. ISBN 0-7126-1279-3.

- O'Reilly, Elizabeth Boyle (1921). How France Built Her Cathedrals - A study in the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries. Harper and Brothers.

In French

- Chastel, André (2000). L'Art Français Pré-Moyen Âge Moyen Âge (in French). Flammarion. ISBN 2-08-012298-3.

- Ducher, Robert (2014). Caractéristique des Styles (in French). Flammarion. ISBN 978-2-0813-4383-2.

- Mignon, Olivier (2015). Architecture des Cathédrales Gothiques (in French). Éditions Ouest-France. ISBN 978-2-7373-6535-5.

- Renault, Christophe and Lazé, Christophe, Les Styles de l'architecture et du mobilier, (2006), Gisserot, (in French); ISBN 9-782877-474658

- Wenzler, Claude (2018), Cathédales Gothiques - un Défi Médiéval, Éditions Ouest-France, Rennes (in French) ISBN 978-2-7373-7712-9

- Le Guide du Patrimoine en France (2002), Éditions du Patrimoine, Centre des Monuments Nationaux (in French) ISBN 978-2-85822-760-0

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/High_Gothic

![Vaults triforia and upper windows of Amiens Cathedral.[11]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/90/Voutes_amiens.JPG/200px-Voutes_amiens.JPG)

No comments:

Post a Comment