| Part of a series on financial services |

| Banking |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Macroeconomics |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Money creation, or money issuance, is the process by which the money supply of a country, or of an economic or monetary region,[note 1] is increased. In most modern economies, money creation is controlled by the central banks. Money issued by central banks is termed base money. Central banks can increase the quantity of base money directly, by engaging in open market operations. However, the majority of the money supply is created by the commercial banking system in the form of bank deposits. Bank loans issued by commercial banks that practice fractional reserve banking expands the quantity of broad money to more than the original amount of base money issued by the central bank.

Central banks monitor the amount of money in the economy by measuring monetary aggregates (termed broad money), consisting of cash and bank deposits. Money creation occurs when the quantity of monetary aggregates increase.[note 2] Governmental authorities, including central banks and other bank regulators, can use policies such as reserve requirements and capital adequacy ratios to influence the amount of broad money created by commercial banks.[1]

Money supply

The term "money supply" commonly denotes the total, safe, financial assets that households and businesses can use to make payments or to hold as short-term investment.[2] The money supply is measured using the so-called "monetary aggregates", defined in accordance to their respective level of liquidity. In the United States, for example:

- M0: The total of all physical currency including coinage. Using the United States dollar as an example, M0 = Federal Reserve notes + US notes + coins. It is not relevant whether the currency is held inside or outside of the private banking system as reserves.

- M1: The total amount of M0 (cash/coin) outside of the private banking system[clarification needed] plus the amount of demand deposits, travelers checks and other checkable deposits

- M2: M1 + most savings accounts, money market accounts, retail money market mutual funds, and small denomination time deposits (certificates of deposit of under $100,000).

The money supply is understood to increase through activities by government authorities,[note 3] by the central bank of the nation,[note 4] and by commercial banks.[3]

Money creation by the central bank

Central banks

The authority through which monetary policy is conducted is the central bank of the nation. The mandate of a central bank typically includes either one of the three following objectives or a combination of them, in varying order of preference, according to the country or the region: Price stability, i.e. inflation-targeting; the facilitation of maximum employment in the economy; the assurance of moderate, long term, interest rates.[4]

The central bank is the banker of the government[note 5] and provides to the government a range of services at the operational level, such as managing the Treasury's single account, and also acting as its fiscal agent (e.g. by running auctions), its settlement agent, and its bond registrar.[5] A central bank cannot become insolvent in its own currency. However, a central bank can become insolvent in liabilities on foreign currency.[6]

Central banks operate in practically every nation in the world, with few exceptions.[7] There are some groups of countries, for which, through agreement, a single entity acts as their central bank, such as the organization of states of Central Africa, [note 6] which all have a common central bank, the Bank of Central African States; or monetary unions, such as the Eurozone, whereby nations retain their respective central bank yet submit to the policies of the central entity, the European Central Bank. Central banking institutions are generally independent of the government executive.[1]

The central bank's activities directly affect interest rates, through controlling the base rate, and indirectly affect stock prices, the economy's wealth, and the national currency's exchange rate.[4] Monetarists and some Austrians[note 7][8] argue that the central bank should control the money supply, through its monetary operations.[note 8][9][10] Critics of the mainstream view maintain that central-bank operations can affect but not control the money supply.[note 9]

Open-market operations

Open-market operations (OMOs) concern the purchase and sale of securities in the open market by a central bank. OMOs essentially swap one type of financial assets for another; when the central bank buys bonds held by the banks or the private sector, bank reserves increase while bonds held by the banks or the public decrease. Temporary operations are typically used to address reserve needs that are deemed to be transitory in nature, while permanent operations accommodate the longer-term factors driving the expansion of the central bank's balance sheet; such a primary factor is typically the trend of the money-supply growth in the economy. Among the temporary, open-market operations are repurchase agreements (repos) or reverse repos, while permanent ones involve outright purchases or sales of securities.[11] Each open-market operation by the central bank affects its balance sheet.[11]

Monetary policy

Monetary policy is the process by which the monetary authority of a country, typically the central bank (or the currency board), manages the level of short-term interest rates[note 10][12] and influences the availability and the cost of credit in the economy,[4] as well as overall economic activity.[13]

Central banks conduct monetary policy usually through open market operations. The purchase of debt, and the resulting increase in bank reserves, is called "monetary easing". An extraordinary process of monetary easing is denoted as "quantitative easing", whose intent is to stimulate the economy by increasing liquidity and promoting bank lending.

Physical currency

The central bank, or other competent, state authorities (such as the treasury), are typically empowered to create new, physical currency, i.e. paper notes and coins, in order to meet the needs of commercial banks for cash withdrawals, and to replace worn and/or destroyed currency.[14] The process does not increase the money supply, as such; the term "printing [new] money" is considered a misnomer.[1]

In modern economies, relatively little of the supply of broad money is in physical currency.[note 11]

Role of commercial banks

When commercial banks lend money, they expand the amount of bank deposits.[15] The banking system can expand the money supply of a country beyond the amount created or targeted by the central bank, creating most of the broad money in a process called the multiplier effect.[15]

Banks are limited in the total amount they can lend by their capital adequacy ratios, and their required reserve ratios. The required-reserves ratio obliges banks to keep a minimum, predetermined, percentage of their deposits at an account at the central bank.[note 12] The theory holds that, in a system of fractional-reserve banking, where banks ordinarily keep only a fraction of their deposits in reserves, an initial bank loan creates more money than it initially lent out.

The maximum ratio of loans to deposits is the required-reserve ratio RRR, which is determined by the central bank, as

where R are reserves and D are deposits.

Rather than holding the quantity of base money fixed, central banks have recently pursued an interest rate target to control bank issuance of credit indirectly so the ceiling implied by the money multiplier does not impose a limit on money creation in practice.[16]

Credit theory of money

The fractional reserve theory where the money supply is limited by the money multiplier has come under increased criticism since the financial crisis of 2007–2008. It has been observed that the bank reserves are not a limiting factor because the central banks supply more reserves than necessary[17] and because banks have been able to build up additional reserves when they were needed.[18] Many economists and bankers now believe that the amount of money in circulation is limited only by the demand for loans, not by reserve requirements.[19][20][15]

A study of banking software demonstrates that the bank does nothing else than adding an amount to the two accounts when they issue a loan.[18] The observation that there appears to be no limit to the amount of credit money that banks can bring into circulation in this way has given rise to the often-heard expression that "Banks are creating money out of thin air".[17] The exact mechanism behind the creation of commercial bank money has been a controversial issue. In 2014, a study titled "Can banks individually create money out of nothing? — The theories and the empirical evidence" empirically tested the manner in which this type of money is created by monitoring a cooperating bank's internal records:[21]

This study establishes for the first time empirically that banks individually create money out of nothing. The money supply is created as ‘fairy dust’ produced by the banks individually, "out of thin air".

The credit theory of money, initiated by Joseph Schumpeter, asserts the central role of banks as creators and allocators of the money supply, and distinguishes between "productive credit creation" (allowing non-inflationary economic growth even at full employment, in the presence of technological progress) and "unproductive credit creation" (resulting in inflation of either the consumer- or asset-price variety).[22]

The model of bank lending stimulated through central-bank operations (such as "monetary easing") has been rejected by Neo-Keynesian[note 13][23] and Post-Keynesian analysis[24][25] as well as central banks.[26][27][note 14] The major argument offered by dissident analysis is that any bank balance-sheet expansion (e.g. through a new loan) that leaves the bank short of the required reserves may affect the return it can expect on the loan, because of the extra cost the bank will undertake to return within the ratios limits – but this does not and "will never impede the bank's capacity to give the loan in the first place". Banks first lend and then cover their reserve ratios: The decision whether or not to lend is generally independent of their reserves with the central bank or their deposits from customers; banks are not lending out deposits or reserves, anyway. Banks lend on the basis of lending criteria, such as the status of the customer's business, the loan's prospects, and/or the overall economic situation.[28]

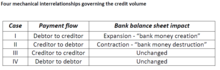

Bank of England tells us in 2019: "Most of the money in the economy is created by banks when they provide loans."[29], but not every provided loan is heightening bank money amount. It depends on payment flows after given loans.[30] (see table by Decker/Goodhart [2021] beside).

Monetary financing

Policy

"Monetary financing", also "debt monetization", occurs when the country's central bank purchases government debt.[31] It is considered by mainstream analysis to cause inflation, and often hyperinflation.[32] IMF's former chief economist Olivier Blanchard states that:

governments do not create money; the central bank does. But with the central bank's cooperation, the government can in effect finance itself by money creation. It can issue bonds and ask the central bank to buy them. The central bank then pays the government with money it creates, and the government in turn uses that money to finance the deficit. This process is called debt monetization.[33]

The description of the process differs in heterodox analysis. Modern chartalists state:

the central bank does not have the option to monetize any of the outstanding government debt or newly issued government debt...[A]s long as the central bank has a mandate to maintain a short-term interest rate target, the size of its purchases and sales of government debt are not discretionary. The central bank's lack of control over the quantity of reserves underscores the impossibility of debt monetization. The central bank is unable to monetize the government debt by purchasing government securities at will because to do so would cause the short-term target rate to fall to zero or to any support rate that it might have in place for excess reserves.[34]

Restrictions

Monetary financing used to be standard monetary policy in many countries, such as Canada or France,[35] while in others it was and still is prohibited. In the Eurozone, Article 123 of the Lisbon Treaty explicitly prohibits the European Central Bank from financing public institutions and state governments.[36] In Japan, the nation's central bank "routinely" purchases approximately 70% of state debt issued each month,[37] and owns, as of Oct 2018, approximately 440 trillion JP¥ (approx. $4trillion)[note 15] or over 40% of all outstanding government bonds.[38] In the United States, the 1913 Federal Reserve Act allowed federal banks to purchase short-term securities directly from the Treasury, in order to facilitate its cash-management operations. The Banking Act of 1935 prohibited the central bank from directly purchasing Treasury securities, and permitted their purchase and sale only "in the open market". In 1942, during wartime, Congress amended the Banking Act's provisions to allow purchases of government debt by the federal banks, with the total amount they'd hold "not [to] exceed $5 billion". After the war, the exemption was renewed, with time limitations, until it was allowed to expire in June 1981.[39]

See also

Footnotes

- At a $1=¥0.0094 conversion rate

References

- Garbade, Kenneth D. (August 2014). "Direct Purchases of U.S. Treasury Securities by Federal Reserve Banks" (PDF). FRBNY Staff Reports no. 684.

Further reading

- Asmundson, Irena; Oner, Ceyda (September 2012). "What Is Money?" (PDF). Finance & Development. IMF. Retrieved 8 March 2018.

- Federal Reserve historical statistics (11 June 2009) Archived June 5, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- Hegeland, Hugo (1970) [1954]. Multiplier Theory (7 ed.). Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0678001622.

- Mankiw, N. Gregory (2012). Macroeconomics (8th ed.). Worth. pp. 81–107. ISBN 978-1429240024.

- Werner, Richard A. (16 September 2014). "Can banks individually create money out of nothing? The theories and the empirical evidence". Elsevier. SSRN 2489665.

External links

- "The Role of Central Bank Money in Payment Systems", Bank for International Settlements, August 2003

- Mitchell, William (2009) "Deficit spending 101: Part 1"; "Part 2"; "Part 3"

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Money_creation

In macroeconomics, the money supply (or money stock) refers to the total volume of currency held by the public at a particular point in time. There are several ways to define "money", but standard measures usually include currency in circulation (i.e. physical cash) and demand deposits (depositors' easily accessed assets on the books of financial institutions).[1][2] The central bank of a country may use a definition of what constitutes legal tender for its purposes.

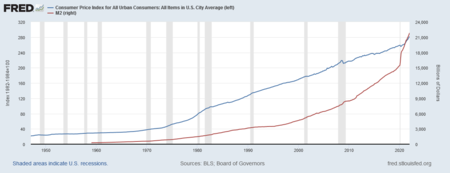

Money supply data is recorded and published, usually by a government agency or the central bank of the country. Public and private sector analysts monitor changes in the money supply because of the belief that such changes affect the price levels of securities, inflation, the exchange rates, and the business cycle.[3]

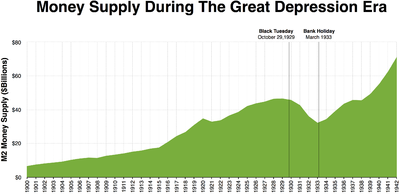

The relationship between money and prices has historically been associated with the quantity theory of money. There is some empirical evidence of a direct relationship between the growth of the money supply and long-term price inflation, at least for rapid increases in the amount of money in the economy.[4] For example, a country such as Zimbabwe which saw extremely rapid increases in its money supply also saw extremely rapid increases in prices (hyperinflation). This is one reason for the reliance on monetary policy as a means of controlling inflation.[5][6]

Money creation by commercial banks

Commercial banks play a role in the process of money creation, under the fractional-reserve banking system used throughout the world. In this system, credit is created whenever a bank gives out a new loan and destroyed when the borrower pays back the principal on the loan.[8]

This new money, in net terms, makes up the non-M0 component in the M1-M3 statistics. In short, there are two types of money in a fractional-reserve banking system:[9][10][11]

- central bank money — obligations of a central bank, including currency and central bank depository accounts

- commercial bank money — obligations of commercial banks, including checking accounts and savings accounts.

In the money supply statistics, central bank money is MB while the commercial bank money is divided up into the M1-M3 components. Generally, the types of commercial bank money that tend to be valued at lower amounts are classified in the narrow category of M1 while the types of commercial bank money that tend to exist in larger amounts are categorized in M2 and M3, with M3 having the largest.

In the United States, a bank's reserves consist of U.S. currency held by the bank (also known as "vault cash"[12]) plus the bank's balances in Federal Reserve accounts.[13][14] For this purpose, cash on hand and balances in Federal Reserve ("Fed") accounts are interchangeable (both are obligations of the Fed). Reserves may come from any source, including the federal funds market, deposits by the public, and borrowing from the Fed itself.[15]

Open market operations by central banks

The examples and perspective in this section may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (June 2010) |

Central banks can influence the money supply by open market operations. They can increase the money supply by purchasing government securities, such as government bonds or treasury bills. This increases the liquidity in the banking system by converting the illiquid securities of commercial banks into liquid deposits at the central bank. This also causes the price of such securities to rise due to the increased demand, and interest rates to fall. These funds become available to commercial banks for lending, and by the multiplier effect from fractional-reserve banking, loans and bank deposits go up by many times the initial injection of funds into the banking system.

In contrast, when the central bank "tightens" the money supply, it sells securities on the open market, drawing liquid funds out of the banking system. The prices of such securities fall as supply is increased, and interest rates rise. This also has a multiplier effect.

This kind of activity reduces or increases the supply of short term government debt in the hands of banks and the non-bank public, also lowering or raising interest rates. In parallel, it increases or reduces the supply of loanable funds (money) and thereby the ability of private banks to issue new money through issuing debt.

The simple connection between monetary policy and monetary aggregates such as M1 and M2 changed in the 1970s as the reserve requirements on deposits started to fall with the emergence of money funds, which require no reserves. At present, reserve requirements apply only to "transactions deposits" – essentially checking accounts. The vast majority of funding sources used by private banks to create loans are not limited by bank reserves. Most commercial and industrial loans are financed by issuing large denomination CDs. Money market deposits are largely used to lend to corporations who issue commercial paper. Consumer loans are also made using savings deposits, which are not subject to reserve requirements. This means that instead of the value of loans supplied responding passively to monetary policy, we often see it rising and falling with the demand for funds and the willingness of banks to lend.

Some economists argue that the money multiplier is a meaningless concept, because its relevance would require that the money supply be exogenous, i.e. determined by the monetary authorities via open market operations. If central banks usually target the shortest-term interest rate (as their policy instrument) then this leads to the money supply being endogenous.[16]

This section needs to be updated. (March 2009) |

Neither commercial nor consumer loans are any longer limited by bank reserves. Nor are they directly linked proportional to reserves. Between 1995 and 2008, the value of consumer loans has steadily increased out of proportion to bank reserves. Then, as part of the financial crisis, bank reserves rose dramatically as new loans shrank.

In recent years, some academic economists renowned for their work on the implications of rational expectations have argued that open market operations are irrelevant. These include Robert Lucas Jr., Thomas Sargent, Neil Wallace, Finn E. Kydland, Edward C. Prescott and Scott Freeman. Keynesian economists point to the ineffectiveness of open market operations in 2008 in the United States, when short-term interest rates went as low as they could go in nominal terms, so that no more monetary stimulus could occur. This zero bound problem has been called the liquidity trap or "pushing on a string" (the pusher being the central bank and the string being the real economy).

Empirical measures in the United States Federal Reserve System

- See also European Central Bank for other approaches and a more global perspective.

Money is used as a medium of exchange, as a unit of account, and as a ready store of value. These different functions are associated with different empirical measures of the money supply. There is no single "correct" measure of the money supply. Instead, there are several measures, classified along a spectrum or continuum between narrow and broad monetary aggregates. Narrow measures include only the most liquid assets: those most easily used to spend (currency, checkable deposits). Broader measures add less liquid types of assets (certificates of deposit, etc.).

This continuum corresponds to the way that different types of money are more or less controlled by monetary policy. Narrow measures include those more directly affected and controlled by monetary policy, whereas broader measures are less closely related to monetary-policy actions.[6] It is a matter of perennial debate as to whether narrower or broader versions of the money supply have a more predictable link to nominal GDP.

The different types of money are typically classified as "M"s. The "M"s usually range from M0 (narrowest) to M3 (broadest) but which "M"s are actually focused on in policy formulation depends on the country's central bank. The typical layout for each of the "M"s is as follows:

| Type of money | M0 | MB | M1 | M2 | M3 | MZM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Notes and coins in circulation (outside Federal Reserve Banks and the vaults of depository institutions) (currency) | ✓[17] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Notes and coins in bank vaults (vault cash) |

|

✓ |

|

|

|

|

| Federal Reserve Bank credit (required reserves and excess reserves not physically present in banks) |

|

✓ |

|

|

|

|

| Traveler's checks of non-bank issuers |

|

|

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Demand deposits |

|

|

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Other checkable deposits (OCDs), which consist primarily of negotiable order of withdrawal (NOW) accounts at depository institutions and credit union share draft accounts. |

|

|

✓[18] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Savings deposits |

|

|

✓[19] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Time deposits less than $100,000 and money-market deposit accounts for individuals |

|

|

|

✓ | ✓ |

|

| Large time deposits, institutional money market funds, short-term repurchase and other larger liquid assets[20] |

|

|

|

|

✓ |

|

| All money market funds |

|

|

|

|

|

✓ |

- M0: In some countries, such as the United Kingdom, M0 includes bank reserves, so M0 is referred to as the monetary base, or narrow money.[21]

- MB: is referred to as the monetary base or total currency.[17] This is the base from which other forms of money (like checking deposits, listed below) are created and is traditionally the most liquid measure of the money supply.[22]

- M1: Bank reserves are not included in M1.

- M2: Represents M1 and "close substitutes" for M1.[23] M2 is a broader classification of money than M1. M2 is a key economic indicator used to forecast inflation.[24]

- M3: M2 plus large and long-term deposits. Since 2006, M3 is no longer published by the US central bank.[25] However, there are still estimates produced by various private institutions.

- MZM: Money with zero maturity. It measures the supply of financial assets redeemable at par on demand. Velocity of MZM is historically a relatively accurate predictor of inflation.[26][27][28]

The ratio of a pair of these measures, most often M2 / M0, is called the money multiplier.

Definitions of "money"

East Asia

Hong Kong SAR, China

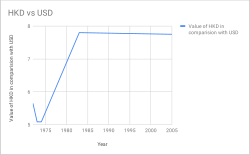

In 1967, when sterling was devalued, the Hong Kong dollar's peg to the pound was increased from 1 shilling 3 pence (£1 = HK$16) to 1 shilling 4½ pence (£1 = HK$14.5455) although this did not entirely offset the devaluation of sterling relative to the US dollar (it went from US$1 = HK$5.71 to US$1 = HK$6.06). In 1972 the Hong Kong dollar was pegged to the US dollar at a rate of US$1 = HK$5.65. This was reduced to HK$5.085 in 1973. Between 1974 and 1983 the Hong Kong dollar floated. On October 17, 1983, the currency was pegged at a rate of US$1 = HK$7.80 through the currency board system.

As of May 18, 2005, in addition to the lower guaranteed limit, a new upper guaranteed limit was set for the [Hong Kong dollar at 7.75 to the American dollar. The lower limit was lowered from 7.80 to 7.85 (by 100 pips per week from May 23 to June 20, 2005). The Hong Kong Monetary Authority indicated that this move was to narrow the gap between the interest rates in Hong Kong and those of the United States. A further aim of allowing the Hong Kong dollar to trade in a range is to avoid the HK dollar being used as a proxy for speculative bets on a renminbi revaluation.

The Hong Kong Basic Law and the Sino-British Joint Declaration provides that Hong Kong retains full autonomy with respect to currency issuance. Currency in Hong Kong is issued by the government and three local banks under the supervision of the territory's de facto central bank, the Hong Kong Monetary Authority. Bank notes are printed by Hong Kong Note Printing.

A bank can issue a Hong Kong dollar only if it has the equivalent exchange in US dollars on deposit. The currency board system ensures that Hong Kong's entire monetary base is backed with US dollars at the linked exchange rate. The resources for the backing are kept in Hong Kong's exchange fund, which is among the largest official reserves in the world. Hong Kong also has huge deposits of US dollars, with official foreign currency reserves of 331.3 billion USD as of September 2014.[29]

Japan

The Bank of Japan defines the monetary aggregates as:[30]

- M1: cash currency in circulation, plus deposit money

- M2 + CDs: M1 plus quasi-money and CDs

- M3 + CDs: M2 + CDs plus deposits of post offices; other savings and deposits with financial institutions; and money trusts

- Broadly defined liquidity: M3 and CDs, plus money market, pecuniary trusts other than money trusts, investment trusts, bank debentures, commercial paper issued by financial institutions, repurchase agreements and securities lending with cash collateral, government bonds and foreign bonds

Europe

United Kingdom

There are just two official UK measures. M0 is referred to as the "wide monetary base" or "narrow money" and M4 is referred to as "broad money" or simply "the money supply".

- M0: Notes and coin in circulation plus banks' reserve balance with Bank of England. (When the bank introduced Money Market Reform in May 2006, the bank ceased publication of M0 and instead began publishing series for reserve balances at the Bank of England to accompany notes and coin in circulation.[31])

- M4: Cash outside banks (i.e. in circulation with the public and non-bank firms) plus private-sector retail bank and building society deposits plus private-sector wholesale bank and building society deposits and certificates of deposit.[32] In 2010 the total money supply (M4) measure in the UK was £2.2 trillion while the actual notes and coins in circulation totalled only £47 billion, 2.1% of the actual money supply.[33]

There are several different definitions of money supply to reflect the differing stores of money. Owing to the nature of bank deposits, especially time-restricted savings account deposits, M4 represents the most illiquid measure of money. M0, by contrast, is the most liquid measure of the money supply.

Eurozone

The European Central Bank's definition of euro area monetary aggregates:[34]

- M1: Currency in circulation plus overnight deposits

- M2: M1 plus deposits with an agreed maturity up to two years plus deposits redeemable at a period of notice up to three months.

- M3: M2 plus repurchase agreements plus money market fund (MMF) shares/units, plus debt securities up to two years

North America

United States

The United States Federal Reserve published data on three monetary aggregates until 2006, when it ceased publication of M3 data[25] and only published data on M1 and M2. M1 consists of money commonly used for payment, basically currency in circulation and checking account balances; and M2 includes M1 plus balances that generally are similar to transaction accounts and that, for the most part, can be converted fairly readily to M1 with little or no loss of principal. The M2 measure is thought to be held primarily by households. Prior to its discontinuation, M3 comprised M2 plus certain accounts that are held by entities other than individuals and are issued by banks and thrift institutions to augment M2-type balances in meeting credit demands, as well as balances in money market mutual funds held by institutional investors. The aggregates have had different roles in monetary policy as their reliability as guides has changed. The principal components are:[36]

- M0: The total of all physical currency including coinage. M0 = Federal Reserve Notes + US Notes + Coins. It is not relevant whether the currency is held inside or outside of the private banking system as reserves.

- MB: The total of all physical currency plus Federal Reserve Deposits (special deposits that only banks can have at the Fed). MB = Coins + US Notes + Federal Reserve Notes + Federal Reserve Deposits

- M1: The total amount of M0 (cash/coin) outside of the private banking system[clarification needed] plus the amount of demand deposits, travelers checks and other checkable deposits + most savings accounts.

- M2: M1 + money market accounts, retail money market mutual funds, and small denomination time deposits (certificates of deposit of under $100,000).

- MZM: 'Money Zero Maturity' is one of the most popular aggregates in use by the Fed because its velocity has historically been the most accurate predictor of inflation. It is M2 – time deposits + money market funds

- M3: M2 + all other CDs (large time deposits, institutional money market mutual fund balances), deposits of eurodollars and repurchase agreements.

- M4-: M3 + Commercial Paper

- M4: M4- + T-Bills (or M3 + Commercial Paper + T-Bills)

- L: The broadest measure of liquidity, that the Federal Reserve no longer tracks. L is very close to M4 + Bankers' Acceptance

- Money Multiplier: M1 / MB. As of December 3, 2015, it was 0.756.[37] While a multiplier under one is historically an oddity, this is a reflection of the popularity of M2 over M1 and the massive amount of MB the government has created since 2008.

Prior to 2020, savings accounts were counted as M2 and not part of M1 as they were not considered "transaction accounts" by the Fed. (There was a limit of six transactions per cycle that could be carried out in a savings account without incurring a penalty.) On March 15, 2020, the Federal Reserve eliminated reserve requirements for all depository institutions and rendered the regulatory distinction between reservable "transaction accounts" and nonreservable "savings deposits" unnecessary. On April 24, 2020, the Board removed this regulatory distinction by deleting the six-per-month transfer limit on savings deposits. From this point on, savings account deposits were included in M1.[19]

Although the Treasury can and does hold cash and a special deposit account at the Fed (TGA account), these assets do not count in any of the aggregates. So in essence, money paid in taxes paid to the Federal Government (Treasury) is excluded from the money supply. To counter this, the government created the Treasury Tax and Loan (TT&L) program in which any receipts above a certain threshold are redeposited in private banks. The idea is that tax receipts won't decrease the amount of reserves in the banking system. The TT&L accounts, while demand deposits, do not count toward M1 or any other aggregate either.

When the Federal Reserve announced in 2005 that they would cease publishing M3 statistics in March 2006, they explained that M3 did not convey any additional information about economic activity compared to M2, and thus, "has not played a role in the monetary policy process for many years." Therefore, the costs to collect M3 data outweighed the benefits the data provided.[25] Some politicians have spoken out against the Federal Reserve's decision to cease publishing M3 statistics and have urged the U.S. Congress to take steps requiring the Federal Reserve to do so. Congressman Ron Paul (R-TX) claimed that "M3 is the best description of how quickly the Fed is creating new money and credit. Common sense tells us that a government central bank creating new money out of thin air depreciates the value of each dollar in circulation."[38] Modern Monetary Theory disagrees. It holds that money creation in a free-floating fiat currency regime such as the U.S. will not lead to significant inflation unless the economy is approaching full employment and full capacity. Some of the data used to calculate M3 are still collected and published on a regular basis.[25] Current alternate sources of M3 data are available from the private sector.[39]

As of April 2013, the monetary base was $3 trillion[40] and M2, the broadest measure of money supply, was $10.5 trillion.[41]

Oceania

Australia

The Reserve Bank of Australia defines the monetary aggregates as:[42]

- M1: currency in circulation plus bank current deposits from the private non-bank sector[43]

- M3: M1 plus all other bank deposits from the private non-bank sector, plus bank certificate of deposits, less inter-bank deposits

- Broad money: M3 plus borrowings from the private sector by NBFIs, less the latter's holdings of currency and bank deposits

- Money base: holdings of notes and coins by the private sector plus deposits of banks with the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) and other RBA liabilities to the private non-bank sector.

New Zealand

The Reserve Bank of New Zealand defines the monetary aggregates as:[44]

- M1: notes and coins held by the public plus chequeable deposits, minus inter-institutional chequeable deposits, and minus central government deposits

- M2: M1 + all non-M1 call funding (call funding includes overnight money and funding on terms that can of right be broken without break penalties) minus inter-institutional non-M1 call funding

- M3: the broadest monetary aggregate. It represents all New Zealand dollar funding of M3 institutions and any Reserve Bank repos with non-M3 institutions. M3 consists of notes & coin held by the public plus NZ dollar funding minus inter-M3 institutional claims and minus central government deposits

South Asia

India

The Reserve Bank of India defines the monetary aggregates as:[45]

- Reserve money (M0): Currency in circulation, plus bankers' deposits with the RBI and 'other' deposits with the RBI. Calculated from net RBI credit to the government plus RBI credit to the commercial sector, plus RBI's claims on banks and net foreign assets plus the government's currency liabilities to the public, less the RBI's net non-monetary liabilities. M0 outstanding was ₹30.297 trillion as on March 31, 2020.

- M1: Currency with the public plus deposit money of the public (demand deposits with the banking system and 'other' deposits with the RBI). M1 was 184 per cent of M0 in August 2017.

- M2: M1 plus savings deposits with post office savings banks. M2 was 879 per cent of M0 in August 2017.

- M3 (the broad concept of money supply): M1 plus time deposits with the banking system, made up of net bank credit to the government plus bank credit to the commercial sector, plus the net foreign exchange assets of the banking sector and the government's currency liabilities to the public, less the net non-monetary liabilities of the banking sector (other than time deposits). M3 was 555 per cent of M0 as on March 31, 2020(i.e. ₹167.99 trillion.)

- M4: M3 plus all deposits with post office savings banks (excluding National Savings Certificates).

Link with inflation

Monetary exchange equation

The money supply is important because it is linked to inflation by the equation of exchange in an equation proposed by Irving Fisher in 1911:[47]

where

- is the total dollars in the nation's money supply,

- is the number of times per year each dollar is spent (velocity of money),

- is the average price of all the goods and services sold during the year,

- is the quantity of assets, goods and services sold during the year.

In mathematical terms, this equation is an identity which is true by definition rather than describing economic behavior. That is, velocity is defined by the values of the other three variables. Unlike the other terms, the velocity of money has no independent measure and can only be estimated by dividing PQ by M. Some adherents of the quantity theory of money assume that the velocity of money is stable and predictable, being determined mostly by financial institutions. If that assumption is valid then changes in M can be used to predict changes in PQ. If not, then a model of V is required in order for the equation of exchange to be useful as a macroeconomics model or as a predictor of prices.

Most macroeconomists replace the equation of exchange with equations for the demand for money which describe more regular and predictable economic behavior. However, predictability (or the lack thereof) of the velocity of money is equivalent to predictability (or the lack thereof) of the demand for money (since in equilibrium real money demand is simply Q/V). Either way, this unpredictability made policy-makers at the Federal Reserve rely less on the money supply in steering the U.S. economy. Instead, the policy focus has shifted to interest rates such as the fed funds rate.

In practice, macroeconomists almost always use real GDP to define Q, omitting the role of all transactions except for those involving newly produced goods and services (i.e., consumption goods, investment goods, government-purchased goods, and exports). But the original quantity theory of money did not follow this practice: PQ was the monetary value of all new transactions, whether of real goods and services or of paper assets.

The monetary value of assets, goods, and services sold during the year could be grossly estimated using nominal GDP back in the 1960s. This is not the case anymore because of the dramatic rise of the number of financial transactions relative to that of real transactions up until 2008. That is, the total value of transactions (including purchases of paper assets) rose relative to nominal GDP (which excludes those purchases).

Ignoring the effects of monetary growth on real purchases and velocity, this suggests that the growth of the money supply may cause different kinds of inflation at different times. For example, rises in the U.S. money supplies between the 1970s and the present encouraged first a rise in the inflation rate for newly-produced goods and services ("inflation" as usually defined) in the 1970s and then asset-price inflation in later decades: it may have encouraged a stock market boom in the 1980s and 1990s and then, after 2001, a rise in home prices, i.e., the famous housing bubble. This story, of course, assumes that the amounts of money were the causes of these different types of inflation rather than being endogenous results of the economy's dynamics.

When home prices went down, the Federal Reserve kept its loose monetary policy and lowered interest rates; the attempt to slow price declines in one asset class, e.g. real estate, may well have caused prices in other asset classes to rise, e.g. commodities.[citation needed]

Rates of growth

In terms of percentage changes (to a close approximation, under low growth rates),[48] the percentage change in a product, say XY, is equal to the sum of the percentage changes %ΔX + %ΔY). So, denoting all percentage changes as per unit of time,

- %ΔP + %ΔQ = %ΔM + %ΔV

This equation rearranged gives the basic inflation identity:

- %ΔP = %ΔM + %ΔV – %ΔQ

Inflation (%ΔP) is equal to the rate of money growth (%ΔM), plus the change in velocity (%ΔV), minus the rate of output growth (%ΔQ).[49] So if in the long run the growth rate of velocity and the growth rate of real GDP are exogenous constants (the former being dictated by changes in payment institutions and the latter dictated by the growth in the economy’s productive capacity), then the monetary growth rate and the inflation rate differ from each other by a fixed constant.

As before, this equation is only useful if %ΔV follows regular behavior. It also loses usefulness if the central bank lacks control over %ΔM.

Arguments

Historically, in Europe, the main function of the central bank is to maintain low inflation. In the USA the focus is on both inflation and unemployment.[citation needed] These goals are sometimes in conflict (according to the Phillips curve). A central bank may attempt to do this[clarification needed] by artificially influencing the demand for goods by increasing or decreasing the nation's money supply (relative to trend), which lowers or raises interest rates, which stimulates or restrains spending on goods and services.

An important debate among economists in the second half of the 20th century concerned the central bank's ability to predict how much money should be in circulation, given current employment rates and inflation rates. Economists such as Milton Friedman believed that the central bank would always get it wrong, leading to wider swings in the economy than if it were just left alone.[50] This is why they advocated a non-interventionist approach: one of targeting a pre-specified path for the money supply independent of current economic conditions, even though in practice this might involve regular intervention with open market operations (or other monetary-policy tools) to keep the money supply on target.

The former Chairman of the US Federal Reserve, Ben Bernanke, suggested in 2004 that over the preceding 10 to 15 years, many modern central banks became relatively adept at manipulation of the money supply, leading to a smoother business cycle, with recessions tending to be smaller and less frequent than in earlier decades, a phenomenon termed "The Great Moderation"[51] This theory encountered criticism during the global financial crisis of 2008–2009.[citation needed] Furthermore, it may be that the functions of the central bank need to encompass more than the shifting up or down of interest rates or bank reserves:[citation needed] these tools, although valuable, may not in fact moderate the volatility of money supply (or its velocity).[citation needed]

Impact of digital currencies and possible transition to a cashless society

See also

- A Program for Monetary Reform

- American Monetary Institute

- Bank regulation

- Capital requirement

- Central bank

- Chartalism

- Chicago plan

- The Chicago Plan Revisited

- Committee on Monetary and Economic Reform

- Core inflation

- Debt levels and flows

- Economics terminology that differs from common usage

- Fiat currency

- Financial capital

- Float

- Fractional-reserve banking

- FRED (Federal Reserve Economic Data)

- Full reserve banking

- Great Contraction

- Index of Leading Indicators – money supply is a component

- Inflation

- Monetarism

- Monetary base

- Monetary economics

- Monetary reform

- Money circulation

- Money creation

- Money market

- Money demand

- Liquidity preference

- Seigniorage

- Stagflation

References

Contemporary monetary systems are based on the mutually reinforcing roles of central bank money and commercial bank monies.

At the beginning of the 20th almost the totality of retail payments were made in central bank money. Over time, this monopoly came to be shared with commercial banks, when deposits and their transfer via checks and giros became widely accepted. Banknotes and commercial bank money became fully interchangeable payment media that customers could use according to their needs. While transaction costs in commercial bank money were shrinking, cashless payment instruments became increasingly used, at the expense of banknotes.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty |title= (help)

- Speech, Bernanke – The Great Moderation. Federal Reserve Bank (February 20, 2004).

Further reading

- Article in the New Palgrave on Money Supply by Milton Friedman

- Do all banks hold reserves, and, if so, where do they hold them? (11/2001)

- What effect does a change in the reserve requirement have on the money supply? (08/2001)

- St. Louis Fed: Monetary Aggregates

- Hülsmann, Jörg (2008). The Ethics of Money Production. Auburn, Alabama: Ludwig von Mises Institute. p. 294. ISBN 9781933550091.

- Discontinuance of M3 Publication

- Investopedia: Money Zero Maturity (MZM)

External links

- Aggregate Reserves Of Depository Institutions And The Monetary Base (H.3)

- Historical H.3 releases

- Money Stock Measures (H.6)

- U.S. MZM magnitude and velocity, used as a predictor of inflation

- Data on Monetary Aggregates in Australia

- Monetary Statistics on Hong Kong Monetary Authority

- Monetary Survey from People's Bank of China

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Money_supply

No comments:

Post a Comment